PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: At the culmination of the Second World War, the Marines of the III Amphibious Corps (III AC) were preparing to assault the Japanese homeland. With the abrupt conclusion of hostilities in September 1945, they were ordered instead to war-ravaged North China. The mission in North China was amorphous—protecting infrastructure and key terrain during the reemergent Chinese Civil War. As Marines labored to resist the expansion of their mission, the lifting of wartime censorship protocols enabled them to voice concern to their families and Congress. Mothers and citizen groups also challenged the young Harry S. Truman administration on the merits and morality of the North China intervention. Set at the dawn of the Cold War, this article investigates the role of unlikely political actors—Marines and mothers—in shaping American policy in North China from 1945 to 1946. Combating narratives of inevitable quagmire, the Marines in North China are examined as important agents in the restraint of American power at contingent moments. This piece argues that the Truman administration failed to make an affirmative case for intervention and was, in part, constrained by popular opinion.

Keywords: III Amphibious Corps, III AC, North China, Chinese Civil War, citizen activism, Cold War, public opinion, occupation, Mike Mansfield, Keller E. Rockey

Introduction

In Montana’s Bitterroot Valley in 1945, Ethel Wonnacott scoured newspapers for international stories from the Western Pacific. As a devout Mormon, meatpacker, wife, and mother of two, Wonnacott would seem an unlikely candidate for political activism regarding America’s foreign affairs.1 Yet, like millions of other American mothers during World War II, Wonnacott had ample reason to stay informed and involved. Her youngest son, 20-year-old Private First Class Gilbert E. Wonnacott, was fighting across the Pacific with the U.S. Marine Corps.2 With the sudden news of the Japanese surrender in mid-August, the Wonnacott family must have felt a profound sense of relief. The much-dreaded invasion of the Japanese mainland would not come to fruition. Wonnacott and the rest of the III Amphibious Corps (III AC), however, did not return immediately to the comfort of their waiting families. Instead, he and 53,000 other Marines deployed from Guam and Okinawa to China’s Shandong (Shantung) and Hubei (Hopeh) Provinces.3 A warm and raucous Chinese crowd welcomed the III AC Marines at Taku in Hubei Province on 30 September during the initial landings.4 Victory parades in Tianjin (Tientsin) and Beijing (Peiping) underscored the celebratory sentiment prevailing in China in early October 1945.5 This, however, proved to be short-lived; soon Wonnacott and his fellow Marines found themselves with a front-row seat to a renewed Chinese Civil War. Just six days after arrival, Marines came under fire from Chinese Communist forces and suffered three casualties while guarding the railway 20 miles (32 kilometers) north of Tianjin. Six thousand miles away in Stevensville, Montana, Ethel Wonnacott intently read newspaper stories and letters from her son. Confused and incensed by a U.S. intervention that seemed to make no sense to her, Wonnacott became one of many mothers motivated to engage in political action.

In October 1945, the political, economic, and military situation in North China was dire. Ravaged by war since July 1937, China suffered perhaps as many as 20 million deaths in its resistance to Japanese aggression and an additional 100 million people were displaced.6 Famine, pestilence, and the Japanese war effort brought North China into a deep depression, and runaway inflation compounded the economic woes.7 As the internationally recognized National government led by Chiang Kai-shek sought to reestablish sovereignty over the devastated region, it was contested by a resurgent Communist opposition led by Mao Zedong. Given these difficult circumstances, it was unclear just what the U.S. interest in North China was: protecting infrastructure; enabling the Chinese Nationalist regime to reoccupy territory under Japanese control ahead of advancing Chinese Communist forces; or fighting Communist insurgents. Absent a coherent message from political and military leaders in Washington, a sizable portion of the American people recognized the potential for the United States to get stuck in a quagmire.

In a crucial period from late 1945 to late 1946, an unlikely pairing of actors—Marines and mothers— displayed remarkable agency, engaging in various forms of political activism regarding U.S. involvement in the burgeoning civil war in China. Marines deployed in China contributed to shaping American foreign policy discourse with their blunt assessments of conditions on the ground. Simultaneously, as the visible agents of U.S. power in China, Marine Corps officers directing the deployment carefully and deliberately avoided a costly escalation that could have trapped the United States as an active combatant in the Chinese Civil War. The Marines’ families—especially their mothers—wrote letters to members of Congress, newspapers, and government officials demanding an end to the mission in North China. While the Truman administration stumbled into the morass of the Chinese Civil War, Marines and mothers sought to galvanize the American public firmly against a de facto American intervention in North China.

Changing of the Guard and Competing Interests

Operation Beleaguer (1945–49), the code name for the III AC occupation of North China, emerged during a period of tremendous national and geopolitical transition. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s promotion of China as “the great Fourth Power in the world” frustrated Winston Churchill, Joseph Stalin, and U.S. military leadership.8 Unbeknownst to the public, during the Big Three summit at the Yalta Conference in February 1945, a frail Roosevelt secretly conceded to Stalin’s territorial demands in the Far East in exchange for Soviet entry into the war against Japan and tacit support for China’s Nationalist government. Roosevelt would not live long enough to serve as the charismatic mediator in the implementation of the Yalta accords as he envisioned.9 That role fell instead to a significantly different personality—Harry S. Truman—at the dawn of the Cold War.

It was one thing to rhetorically support Roosevelt’s vision of China as a world power, but confronted with an assertive Soviet Union and a sudden end to the war, Truman faced difficult choices and the practical limitations of U.S. strength. By the next meeting of the Big Three at the Potsdam Conference in July 1945, Truman suspected that recent Soviet behavior in Eastern Europe foreshadowed Soviet behavior in the Far East. Truman sought to minimize Russian expansion in East Asia by shutting the Soviets out of the military occupation of Japan and by placing U.S. troops on the mainland in China and Korea.10 Furthermore, after 2 September 1945 (Victory over Japan Day), the new president was confronted by strong political pressure to rapidly demobilize America’s armed forces and a forthcoming midterm congressional election in 1946.11 Roosevelt’s public speeches had justified American sacrifice of troops and material in a global struggle for freedom, self-determination, and anti-imperialism. In truth, Roosevelt brokered secret agreements with allies that had yet to abandon the imperial order. Roosevelt famously circumvented bureaucrats, but Truman now faced War, Navy, and State departments with differing ideas about how to occupy Japanese territory.12 As the Pacific War came to a sudden end, the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) rushed to issue orders, establish boundaries, and to cope with conflicting priorities.

Operations Blacklist, Campus, and Beleaguer— the occupations of Japan, South Korea, and North China, respectively—all competed for limited resources, especially troops and sealift. After debate among the Services and theater commanders, the JCS prioritized first Japan, then Korea, and finally China. Until the 11th hour, an American occupation of the key port of Dalian (Dairen) in Manchuria was in play. With the devil in the details, field grade officers at the Pentagon established boundaries that sought to marry political directives with military realities, such as the 38th parallel (latitude 38° north), which would divide the U.S. and Soviet zones of occupation in Korea.13 On 9 August, the Soviets entered the Pacific War and the second atomic bomb destroyed Nagasaki, Japan. The next day, Japan broadcast its intent to surrender. The race to the mainland and a contest to shape a new order for East Asia was on.

While countering Soviet ambitions drove President Truman to commit forces to mainland Asia and deny Stalin an occupation zone in Hokkaido, supporting the Chinese Nationalist government emerged as an important element of U.S. policy.14 Keenly aware of the growing tension between the Chinese Nationalists and Communists, U.S. Army general Albert C. Wedemeyer, commanding general of U.S. Forces China and advisor to Chinese Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek, requested six American divisions to stabilize North and Central China. With insufficient occupation forces to meet demand, the JCS met Truman’s intent by seizing key ports and terrain in North China with the Marines of the III AC.15 Prioritized last for sealift, the III AC deployed in late September 1945. In the lull of August–September and responding to the long-anticipated Soviet invasion of Manchuria, Mao Zedong redeployed his Communist forces to North China and Manchuria.16 Directed by the JCS, Wedemeyer would make U.S. sea and air lift available for nearly 500,000 Nationalist troops to ports and airfields secured by the III AC.17 While what turned out to be fruitless high-level negotiations in Chongqing (Chungking) between Chiang and Mao were taking place, the scene for a renewed Chinese Civil War was being set in the northeast. Behind closed doors, factions within the Truman administration viewed the III AC as an answer to meet different policy aims, ranging from checking Soviet ambition to reasserting Nationalist sovereignty. Publicly, the landing of the III AC in North China came as a surprise. Absent a formal announcement from the Truman administration, as newspapers reported the Marine landings in October, diplomats, politicians, Marines, and the American public wondered aloud: just exactly what were the Marines doing in North China?

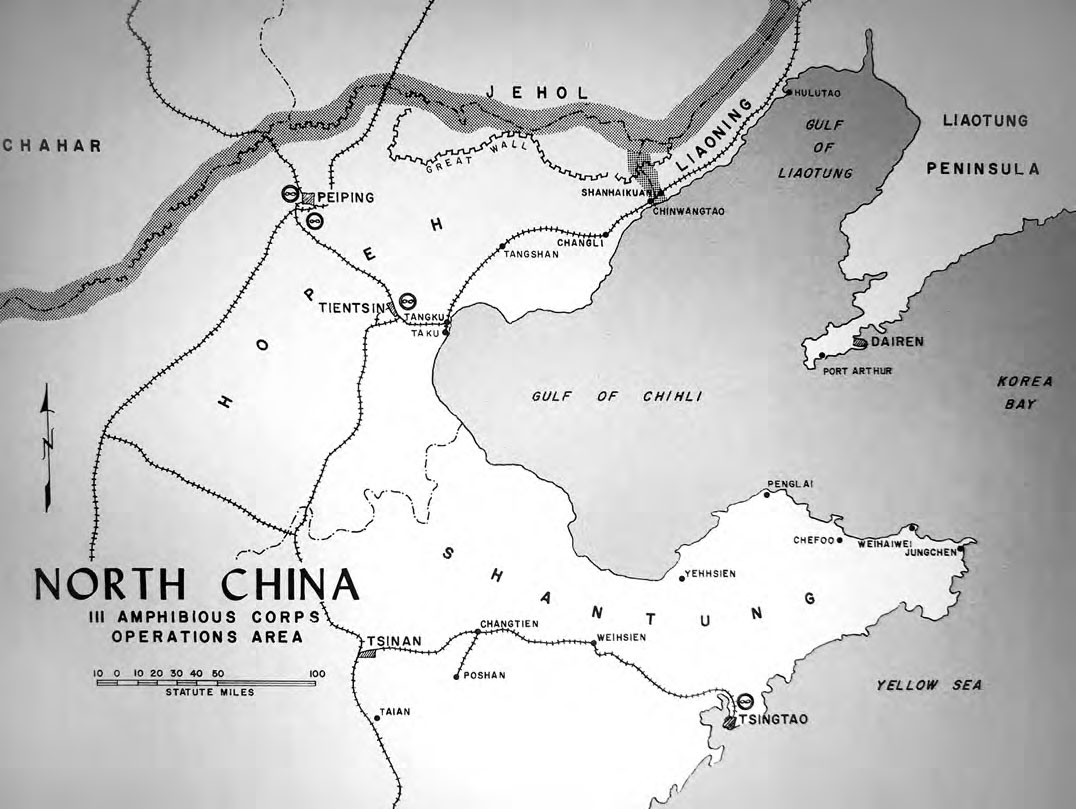

Occupation plan for Imperial Japanese-held territory,1945. Operation Beleaguer would be the responsibility of the Marine III Amphibious Corps in China. Courtesy of Archives, Marine Corps History Division

Montana Congressman Sounds the Alarm

One congressman’s clear and credible voice stood out immediately in opposition to U.S. intervention in North China: Michael J. Mansfield of Montana’s first congressional district. From October to December 1945, Representative Mansfield carried out a veritable media and policy blitz in the halls of Congress, in the State Department, and in print and broadcast media. A member of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, Mansfield sensed strategic confusion and bureaucratic dysfunction lurking behind America’s China policy.18 The Montana democrat publicly expressed his frustration on the House floor and in public appearances in early October 1945.19 In the week following the III AC’s landing, Mansfield was one of the first government officials to highlight the dangerous potential for war. Appearing as a panelist for the Foreign Policy Association, Mansfield took a pragmatic stance against an enhanced American empire. Recalling an interventionist era when Marines landed to defend U.S. business interests in China and Latin America, Mansfield emphatically stated that “the policy of imperialism . . . must be a thing of the past.”20 In a speech before the House on 11 October, Mansfield reminded his fellow congressmen—and the newspapers he knew would print his words—of China’s domestic volatility.21 Not surprisingly, the former Marine Corps private intently focused on the anticipated quandary the Marines would face with the probable renewal of a Chinese Civil War. Mansfield noted that “the Shantung and Hopeh provinces. . . . contain sizeable Communist elements” and that “in that area we might be unable to maintain a hands-off policy.” He noted also that “the landing of the First and Sixth Marine Divisions . . . constitute an unwarranted interference in the affairs of China.”22 Mansfield recommended a rapid withdrawal, fearful of a creeping political role for the leathernecks in the unpredictable Chinese morass. Mansfield’s speech on 11 October was printed in newspapers around the world, but he also set his sights on persuading key policymakers in the Department of State. Visiting the director of the Bureau of Far Eastern Affairs, John Carter Vincent, on 15 October, Mansfield reiterated his deep concerns about a lengthy Marine presence in North China and emphasized his “fear that the Soviet Union” might postpone withdrawal from Manchuria as a result. Vincent presented Mansfield with an official letter to Representative Emerson Hugh DeLacy (DWA) stating that “our armed forces are in China not for the purpose of assisting any Chinese faction or group.”23 Vincent noted that after Mansfield read the letter, “the explanation . . . did not satisfy” him.24 In a memorandum to Acting Secretary of State Dean G. Acheson, Vincent proposed that Acheson prompt the secretaries of war and the U.S. Navy to make public statements that the Marines “would be withdrawn as soon as they [could] be relieved by Chinese Government Forces.”25 In Mansfield, Vincent found an ally who not only agreed with his position but also was a willing partner unencumbered by bureaucratic media protocols. Mansfield would be the public voice that Vincent could not.

The same day Vincent met with Mansfield, Acheson received a cable from Chongqing emphasizing the benefits of the Marine presence for Chiang Kaishek’s Nationalist government. Despite awareness of heightened Chinese Communist ire toward the United States, the American diplomatic mission in China was nevertheless pleased that Marines were tipping the balance toward the Nationalists. The U.S. military attaché happily reported that “Chinese Communists are no match for Central Govt [sic] troops acting with American assistance.”26 Mansfield’s State Department meeting and 11 October congressional speech pressurized the State Department’s internal deliberations about China policy and bolstered Vincent’s position against the American mission in Chongqing. The debate about U.S.-China policy entered an important phase in autumn 1945. Mansfield’s speech occurred in the wake of the London Council of Foreign Ministers’ meeting, where significant friction between Secretary of State James F. Byrnes and Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov emerged about the future of democracy in Eastern Europe and the Soviet role in the Far East.27 Mansfield’s anti-interventionist speech was printed in the Soviet newspaper Izvestiya on 16 October, and Ambassador W. Averell Harriman cabled Mansfield’s retranslated speech to the secretary of state and to Chongqing.28 The state-controlled Soviet press found Mansfield’s position favorable to Soviet interests, which gave American diplomats understandable pause. The Marines in North China were already pawns in a geopolitical Cold War chess game that few Americans in October 1945 even knew about.

While trying to get on the president’s calendar, Mansfield returned to Congress on 30 October and delivered another speech critical of the Truman administration’s deployment of Marines. Mansfield declared to the House that a Chinese “civil war is in progress” and that “marines have already been wounded in the province of Shantung because of fighting between Chinese elements.” Mansfield again called for an unequivocal withdrawal from North China, not just on the basis of projected risk but on hard-earned credit fighting World War II. “These men,” he said, “have done their job in the Pacific and the best policy for us would be to bring them home to their country and their loved ones.”29 As Mansfield spoke, Consul Paul W. Meyer in Tianjin cabled to administration officials an alternate view of the important stabilizing role Marines played in the key railroad city. Meyer noted that the “mission of American Marines . . . daily takes on more of a political aspect” and that “this development is natural and unavoidable . . . and presumably was contemplated when the Marines were sent in here.”30 Meyer’s recommendation stood in stark contrast to Mansfield’s, revealing the complicated risk balance the Truman administration faced. All options presented consequences.

By the first week of November, headlines like “Yank Intervention Charged by Reds” appeared nationwide.31 After a month of speeches, press events, and State Department meetings, Mansfield took his case directly to Truman and reminded the president about “our fundamental policy of non-interference.” In a letter on 7 November, Mansfield wrote to the president that “the sending in of over 50,000 United States Marines to North China . . . is, in my opinion, potentially explosive . . . our forces are caught in a situation not of their making and one which may involve us unwittingly.” Mansfield raised the specter of public opinion and appealed to Truman’s political sense, noting that “it will cause trouble here at home as the American people have no desire for their boys to become involved in another country’s troubles.” Finally, Mansfield introduced Truman to indications of low troop morale, writing, “I have received hundreds of letters in the past month from servicemen in Asia and the feeling on their part is one of great discontent. These men have done their job and the best policy for us would be to bring them home.”32 Truman granted Mansfield a White House meeting about China policy three weeks later, but his administration moved immediately to calm the growing clamor raised by Mansfield and a skeptical public. In early November, Secretary of State Byrnes held a press conference and announced that “the United States is planning to withdraw its Marines from hot spots in China.”33 Byrnes’s statement may have bought some time for Truman’s plans to mature, but the deteriorating conditions in North China prevented a hasty withdrawal. The burden of pursuing a more nuanced U.S. policy in the Far East would fall on the shoulders of the III AC.

Marines, Morale, and Mission: Military Voices (1945–46)

Deployed to North China in October 1945, the Marines of III AC implemented a more limited American policy by resisting the expansion of their mission and restraining the use of force. They also wrote home in exasperated frustration. Operation Beleaguer tasked the III AC with seizing key ports, railheads, airfields, and cities in North China to accept the “local surrender of Japanese forces” and “to cooperate with Chinese Central Government Forces,” while “avoiding collaboration” with “forces opposing the Central government.”34 The III AC, commanded by Major General Keller E. Rockey, primarily comprised the 1st and 6th Marine Divisions as well as the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing. All told, the veteran 53,000-man III AC brought a formidable, full-spectrum combat force of tanks, fighter aircraft, artillery, and infantry to North China. Despite the Marines’ advantages in firepower and equipment, they were heavily outnumbered in North China by Japanese soldiers (326,000), Chinese “puppet” troops under Japanese control (480,000), and at least 170,000 Communist Chinese forces.35 Exactly how these disparate elements would interact was unclear. Only time would tell whether the Americans would be welcomed as liberators or shunned as invaders by the millions of liberated and war-weary Chinese. As confused as the mission and environment seemed to Marine senior officers like General Rockey, the young enlisted Marines were even more in the dark. The American troops’ morale, peaked by America’s and its allies’ sudden victory in August, quickly evaporated by late 1945, and they sounded off in letters home and in protest meetings throughout the Pacific declaring that “we have won the victory . . . we want to go home now!”36 The “citizen army,” which came to view itself as “exiled citizens,” turned to political activism.37 Some Marines were simply eager to return to their prewar lives and perceived their open-ended stay in China as fundamentally unfair—especially as compared with their Army counterparts in Europe. A group of Marines wondered “if Uncle Sam [knew] there is such a thing as the Marine Corps and especially the 1st Marine Division?”38 Other Marines, however, wrote letters to Congress pointedly skeptical of U.S. aims in postwar China. One noted that while this was “primarily a political question,” he had earned “the right to ask questions,” including “why are we in China,” after the hard-fought battle of Okinawa.39 Armed with pens and newly freed from wartime censorship, citizen soldiers participated in the democracy they had fought to defend.

III Amphibious Corps operations area of Shandong and Hubei Provinces. The Marines would secure key ports, cities, and railways. The Soviet Far East Army occupied neighboring Manchuria (Jehol and Liaoning Provinces), 1945. Courtesy of Archives, Marine Corps History Division

In North China, senior leaders and staff of the III AC sought to minimize expansion of their mission beyond simply disarming and repatriating the Japanese. The temptation to serve as facilitators for the Chinese Nationalist forces persisted throughout the Marines’ time in North China. While the Marine leaders accepted the Truman administration’s preference for a “strong, peaceful, united, and democratic China” under Chiang Kai-shek, they also recognized that American policy would hinge largely upon the Communist response.40 Shaped by experienced leaders, the Marines established and maintained a baseline policy of noninvolvement and risk mitigation through skillful negotiation and strict rules of engagement.

General Rockey and his senior officers immediately recognized that the Communists desired to maintain their positional advantage and would resist the deployment of Nationalist forces. Fortunately, the Marine leadership was experienced not only in recent combat, but also in occupation duty before the war. Of the eight generals in the III AC, only Rockey had never been stationed in China, although he had served with distinction in the occupations of both Nicaragua and Haiti.41 Perhaps the most experienced was Brigadier General William A. Worton, Rockey’s chief of staff. A Chinese speaker with more than 12 years of China experience, Worton coordinated the advanced party and identified the key locations where the Marines would deploy and billet.42 In late September, Worton was contacted by “the people opposed to Chiang Kai-shek.” Zhou Enlai (Chou En-lai) arrived for a tense negotiation and informed Worton that the Communist troops would fight the Marines if they attempted to occupy Beijing. Unfazed, Worton coolly informed Zhou that the highly trained III AC would sweep aside any force the Communists could muster. Noting the Marines’ superior firepower, maneuverability, and airpower, Worton concluded the tense meeting by informing Zhou exactly how the Marines could easily occupy Beijing. Zhou replied that “he would get the Marines’ orders changed.” This was possible as Mao Zedong and Chiang Kai-shek were negotiating in Chongqing.43 At this pivotal moment in North China, Zhou and Mao chose not to resist the Marines’ advance in force.44 Mao opted instead for a strategy of information warfare “designed to arouse public opinion” in the United States and China against American support for Chiang.45

Marine and Navy senior leaders also sought to avoid direct confrontation with Communists by carefully selecting operating areas and by establishing strict rules of engagement. The governing order stated that the mission “is one of assisting a friendly nation in the discharge of a large and complex task. In accomplishing this task every effort must be made to limit our participation to one of an advisory and liaison nature.”46 This policy was tested at the outset at Chefoo in Shandong Province, where an intended landing site quickly proved a point of friction. When local Communists seized the port before Americans could land, the Navy-Marine Corps leadership faced a dilemma: put ashore and assert American authority in the name of the Chinese Nationalist government or cede the territory to the Communists. In this context, Seventh Fleet commander Admiral Daniel E. Barbey and General Rockey met aboard the USS Catoctin (AGC 5) just offshore Chefoo on 7 October and weighed their options. While General Lemuel C. Shepherd Jr.’s 6th Marine Division could easily have secured the port by force, Rockey decided to avoid the potential conflict and instead to land the division at Qingdao (Tsingtao). Rockey later recalled that Chiang was furious about this decision during a face-to-face meeting in November.47 Rockey, however, was quite comfortable with his decision for reasons made clear in a 13 October letter to Commandant of the Marine Corps General Alexander A. Vandegrift. “Admiral Barbey and I,” Rockey wrote, “both felt that any landing there would be an interference in the internal affairs of China; that it would be bitterly resented by the Communists and that there would probably be serious repercussions.”48 Rockey’s caution contrasted with that of his chief of staff, Worton, who had stared down Zhou just days before. Perhaps Rockey was shaped by his personal experience fighting a tough counterinsurgency in Nicaragua in 1928 as a young major, for which he received a second Navy Cross. Rockey was reluctant to place his Marines in a similar position.49

One of the principal ways individual Marines resisted participation in the growing Chinese Civil War was through strict rules of engagement. Faced with persistent threats, firefights, casualties, and abductions, Marines sought creative ways to use limited and proportionate force to deescalate perilous confrontations. Nonlethal shows of airpower, smaller tactical maneuver elements, and limited armament were some of the techniques Marines used to avoid larger clashes with the ubiquitous Communists.50

The day before General Rockey’s conference off the coast of Chefoo, Marines came under fire while attempting to clear roadblocks 22 miles (35.4 km) northwest of Tianjin. Not coincidentally, that same day the 92d Chinese Nationalist Army began to arrive in Beijing via American aircraft. Despite taking three casualties and returning small arms fire, the 1st Marine Regiment avoided the use of supporting artillery and temporarily withdrew in good order. The following day, the Marines incorporated a visible show of force with tanks and fighter aircraft, allowing the road to the ancient capital of Beijing to be cleared without further bloodshed.51 Marines routinely employed aircraft as a show of force, a nonlethal innovation designed to demonstrate control and improve reconnaissance across the massive operating area.

The mission of these aircraft—like so much of the Marines’ recent Chinese experiences—was perplexing to some. One corporal wrote that “for almost three days our airplanes flew in formation back and forth and had there been any trouble they would of [sic] not been able to drop bombs on Chinese people.” This was not a cynical “glory hunt,” as he supposed and described it, but instead a deliberate tactical choice to limit the use of force and avoid escalation. Coincidentally, this Marine belonged to the 29th Marine Regiment, which had disembarked at Qingdao due to the potential Communist threat at Chefoo. The corporal noted that “luckily the trouble between the Chinese was to [sic] hot so we was put here into Tsing-tao . . .now we are doing nothing except stand guard duty over our own camp.”52 The relative boredom of the Shandong Marines was a good problem to have in late 1945.

As the Marines in Hubei Province defended key trestles and junctions of the critical railway, the Communists began to sabotage the tracks and challenge the small, remote Marine units in coordinated attacks with mines and harassing small arms fire. Even generals traveling by train were not immune. Visiting his widely spread-out forces along the Tanggu-Qinhuangdao (Tangku-Chinwangtao) railway, Major General DeWitt Peck, commander of the 1st Marine Division, came under attack on 14 November. After the rail lines were blown in front of the train, rifle fire poured onto Peck and his escort Marines from an adjacent village. Returning fire and maneuvering for cover, Peck worked his way to the radio jeep tied down on a flat car. Radioing for reinforcements, Peck also contacted General Rockey and requested immediate close air support. Interestingly, the aircraft sortied from the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing were to be loaded with “ammunition only” and not equipped with bombs—something the wing commander protested. Communist fire broke off before the aircraft arrived, preventing a potentially difficult decision. In subsequent messages between Rockey and General Albert Wedemeyer, commander of all U.S. forces in China, Rockey “indicated that he was ready to authorize a strafing mission if fire continued from the offending village.” While the considerable restraint shown by Peck and the proportional response of strafing rather than bombing from Rockey was notable, Wedemeyer raised the stakes further. In a message to Rockey, Wedemeyer wrote: “If American lives are endangered . . . it is desired that you inform the military leader or responsible authority in that village in writing that such firing must be stopped. After ensuring that your warning . . . has been received and understood, should firing continue, you are authorized to take appropriate action for their protection.”53 Such restrictive rules of engagement placed Marines at tremendous risk, but also underlined the extent to which military leaders went to avoid greater involvement in the Chinese Civil War.

The restrictive rules of engagement would be tested continuously during the Marines’ tenure in North China in numerous small firefights, but none in 1945 gained the attention of the American public like the Anshan incident. On 4 December, suspected Communists shot two Marines in the countryside.54 One Marine succumbed to his wounds and the second survived by playing dead, despite being shot a second time at point-blank range. The wounded man slowly crawled back to his post and relayed the story to his chain of command. In response, a light infantry force from 1st Battalion, 29th Marines, set out to confront the perpetrators in the small village of Anshan. Approaching the village near nightfall, the patrol established a mortar position, and then sought out the local leadership with an interpreter’s help. So far, they precisely followed Wedemeyer’s directive. The young officer leading the patrol told the village leaders “to surrender the murderers within a half hour” or the village would be shelled. After the tense 30 minutes expired and no one surrendered, the Marines fired “24 rounds of high explosive and one of white phosphorus” toward the village perimeter. No one was killed by the shelling, and little physical damage occurred. Nevertheless, American journalists reported a salacious version that alleged commission of a war crime.55

Articles with titles such as “Marines Shell Village in North China” ran across the country.56 A particularly harsh editorial in the Washington Post elicited a rare letter to the editor in response from Commandant General Vandegrift on 14 December. The Washington Post asked, “To what values are the United States Marines forever faithful?,” before expressing “shock and shame” at the report of the shelling. The editorial implied that the Marines had committed a war crime on par with those committed by Nazi Germany and that “from the point of view of the Chinese . . . it is perhaps indistinguishable from the kind of civilization brought to them by the Japanese.”57

Congressman Mansfield noted the Washington Post editorial and asked Vandegrift for a copy of the investigative report. Mansfield viewed the Anshan incident as a prime example of the unintended consequences of deploying Marines in China that could only worsen as the Chinese civil war expanded.58 Vandegrift completed the inquiry and sent a copy to Mansfield as well as the copy of a four-page rebuttal letter to Eugene Meyer, publisher of the Washington Post. Vandegrift noted that only “two windowpanes” were damaged and that the rounds were carefully “placed outside” the village walls. Vandegrift then concluded that “in a delicate and confusing situation [the Marines in China] have performed their tasks with exceptional tact and intelligence.”59 Such a full-throated defense from the Commandant was notable, but it also exhibited how a small-unit tactical decision could have profound impact on the American public via a recently uncensored press.

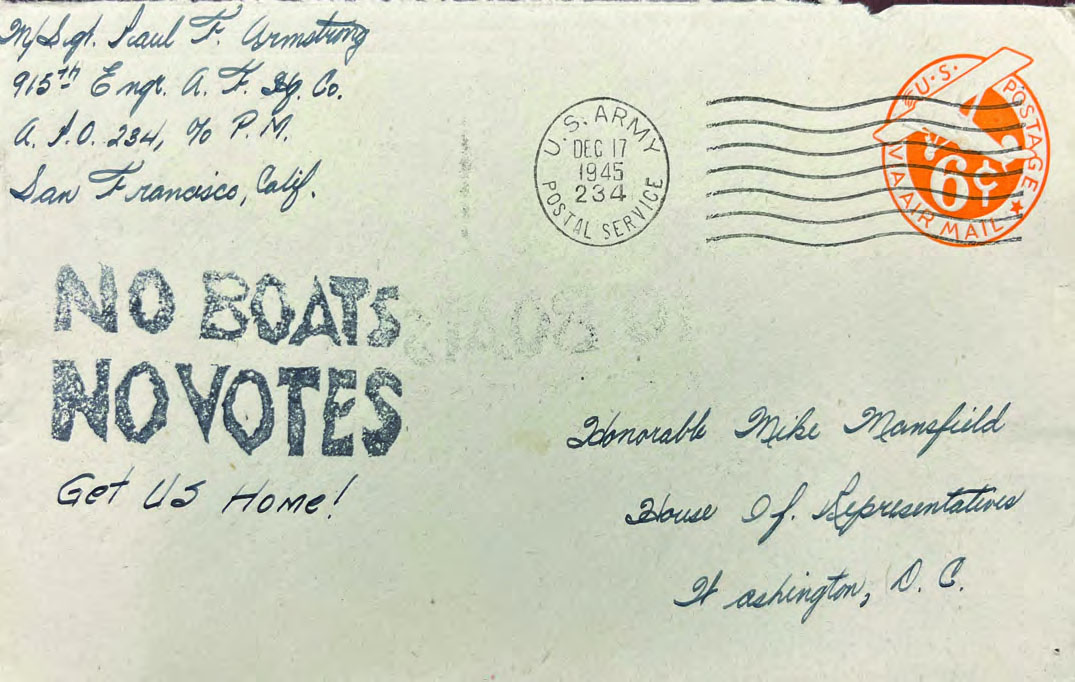

As wartime censorship laws were lifted in September 1945, enlisted soldiers, airmen, and Marines in occupation duties throughout the Pacific expressed their frustration through letters, telegrams, and organized meetings.60 The Tokyo-based editor of the military paper Stars and Stripes estimated that “more than half” of servicemember’s letters for the “Comment and Query” section were complaints about the slow pace and fairness of redeployment. In a clear nod toward political accountability, the stamp “No Boats, No Votes” appeared on thousands of letters mailed from the Pacific in late 1945.61 The situation in North China pressurized the palpable angst of servicemembers and their families, and they “flooded Congress” with letters in response.62 Mansfield was deluged with correspondence from American troops overseas containing blunt assessments and serious reservations about what the future held for them.63 Private First Class Warren G. Peterson of Company C, 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, was a candid and frequent correspondent with Mansfield. Peterson also had another relationship with Mansfield: he had attended Mansfield’s Far East history class at the University of Montana in 1942.64 Peterson was skeptical of American policy in China from the outset and kept Mansfield updated with articles from overseas papers and feedback from enlisted Marines. Peterson’s unit defended the rail junction at Qinhuangdao, a crucial point in transporting essential coal from neighboring Soviet-occupied Manchuria to the major cities of Tianjin, Beijing, and Shanghai. The 7th Marines were spread out along a railway line almost 200 miles (322 km) in length in Hubei Province, the very section of line where General Peck came under attack.

A Guam-based servicemember posted a letter to Congressman Mike Mansfield (D-MT) that urged Congress to take action on demobilization in December 1945. The “No Boats, No Votes” stamp appeared on thousands of letters mailed to the United States from the Pacific. Series 4, box 26, folder 6, Mike Mansfield Papers, Archives and Special Collections, University of Montana

Mansfield delivered an anti-interventionist speech in Congress that resonated immediately with Marines in China who desperately wanted to go back home and dreaded the thought of an extended war. “The Men of the Detachment stationed in Ching Wang Tao, China,” wrote to Mansfield: “We who are stationed here appreciate the fact that there is at least one man in Washington who realizes . . . there is absolutely no reason for us to be here.” Cynically recalling the fabled imperial duty of the “China Marines,” the Marines of 1945 clearly no longer felt the same allure of “exotic” duty. The unknown Marine dryly wrote, “The ‘old’ Corps can claim that title with our blessings.”65 Included in the letter was a daily news sheet distributed by Marine leadership that included a synopsis of Mansfield’s position on withdrawal and nonintervention in China.66 This story could easily have been omitted from the short news compilation, but instead was selected by an editor and widely distributed to Marines. Purposefully or not, this story struck a nerve with Marines ready and willing to write to their congressman.

While Peterson was likely involved in the first group letter, he began writing to Mansfield personally on 26 October.

We are in the middle of the most confusing mess of international bluff and power politics that I ever thought of. I’m afraid we may mess around until plenty of us get hurt.. . . Yesterday the general in charge of the Communist Army in this area served notice that he plans to move into Chin Wang Tao and set up a government. We received orders from Division headquarters at Tientsin to stop him. Today we checked ammunition and began setting up machine gun emplacements.67

Peterson and his fellow Marines hoped not to need to use their machine guns.

The palpable tension in Qinhuangdao was not just a local phenomenon. Some 300 miles (483 km) south in Shandong, enlisted Marines in the 6th Marine Division also expressed a cautious attitude. Corporal David W. Taylor wrote to Mansfield from Qingdao on 30 October, “I hope that . . . those responsible will get the word and take all troops out of here before sombody [sic] set off the firecracker between these Chinese and have some American boys die. We can see it plenty plain over here.”68

Peterson’s letter to Mansfield on 6 December expressed further frustration about the Marines’ convoluted mission. He was openly skeptical of official statements regarding America’s aims in China. Peterson thought that the American position was far from neutral and that Marines were openly “aiding the Chinese Nationals.”69 Peterson presented a series of concrete examples of how American policy had aided and abetted the Nationalist military.

American-trained, American-equipped Nationalist troops landed in [Qinghuangdao] from American transports. Apparently the Marines had made a beachhead for the Nationalists. We had taken strategic points without resistance from the Communists. Then the Nationalists landed in large numbers and pushed inland. Meanwhile we guarded their communication and transportation lines.70

Peterson, in thinking aligned with Mansfield, extrapolated America’s China policy in the emerging Cold War context. Drawing a parallel to the U.S. Army incursion into Russia in 1919, Peterson wrote,

I want to know why the American people are not told what we are doing here . . . is this an Archangel Expedition to save China from Communism? Does our government feel that we must keep China under our influence

in order to keep out of Russia’s? Is this the testing ground of World War III?71

Mansfield wrote back to Peterson and included a copy of his speech to Congress from 11 December. Mansfield was “wholeheartedly in accord with” Peterson’s sentiments and solicited further supporting data from the ground level that Mansfield could leverage in Congress, including local press clippings and news stories from Stars and Stripes.72

From October to December 1945, Marines deployed to China resisted open participation in the Chinese Civil War by minimizing their military role, restraining the use of lethal force, and through writing letters to families and congressmen. The numerous contingent moments in the early deployment to North China sought to strike a careful balance between “assistance to a friendly nation,” while avoiding open participation in “fratricidal conflict.”73 A frustrating and difficult task, this balance required tremendous discipline, shrewd decisionmaking, and strict rules of engagement. While the rules of engagement were extremely rigid, information control and censorship were not. That laxity was what enabled the young enlisted Marines to engage in political activity by writing uncensored letters to their parents and Congress. As with all military operations, the moments of contingency apply to all combatants. Just as Marines deliberately avoided escalation, the Communists also side-stepped massed formations and limited themselves to small, isolated, harassing attacks. The Office of Strategic Services assessed this as part of a deliberate Communist strategy to turn American public opinion against intervention on the side of the Nationalists.74 The troops wanted to go home promptly, and the galvanizing purpose of winning the war expired with the Japanese surrender. By keeping a low military profile vis-à-vis the U.S. Marine Corps deployment, the Communists would not offer another Pearl Harbor-type moment that cried for revenge.

Political Agents: Mothers, Wives, and Citizen Groups

The removal of censorship also brought Chinese stories like the Anshan incident onto the front pages of newspapers and into the consciousness of citizens across America. The American people relished the promise of a coming peace and resisted the prospects of a new Asian war in China. At the end of 1945, Americans could proudly reflect on a four-year national effort to defeat fascist dictatorships overseas in Germany, Italy, and Japan. In that herculean task, the United States placed more than 16.1 million personnel in uniform, deployed forces across two oceans, and produced more tanks, aircraft carriers, planes, submarines, vehicles, and weapons than any other world power.75 The war touched every portion of society and lifted the economy out of depression, but at tremendous cost. More than 405,000 uniformed Americans did not return.76 As the perplexing occupation duty in North China emerged as a potential lengthy intervention into a civil war, mothers, wives, and citizen groups rose in opposition to a new conflict via letters to Congress, newspapers, and through grassroots organization.

One of the ways citizens sought to influence American policy toward China was by writing their government leaders. Correspondence from parents, spouses, and citizen groups suggest that a de facto consensus existed about the need for American noninterference in China and prompt demobilization of the armed forces.77 Several letters penned by blue-star wives (women with husbands in service) pleaded for assistance to return a husband to help raise young children, run a family farm, or otherwise provide a living. Above all, wives and mothers wanted their loved ones home safely. They remained all too aware of the gold-star wives and mothers who would never be so fortunate.78

Mothers voiced steadfast opposition to the Marine deployment to North China in late 1945. These women did not mince words. Writing from Stevensville in December 1945, Ethel Wonnacott reminded Mansfield that mothers wanted their sons back: “I gave my son proudly to fight for our country but not to fight China’s Civil War . . . he has seen enough war and hell.” Just in case the blunt meatpacker failed to reach Mansfield on these merits, she reminded the congressman that she was an active voter ready to organize. “I feel the voice of Montana Mothers should be enough to command your attention.”79 Wonnacott penned similar comments to Montana Senator James E. Murray, noting that “the sentiments of all Mothers” were that “China’s war” was not worth “one American boys’ life.”80 When Wonnacott later penned a letter to the editor of the Missoulian, she signed it “A Mother of a Montana Marine, Stevensville,” but nevertheless issued a call to arms for the community to “raise a howl” so that “Washington will have to listen . . . and demand that our sons be taken out of China, fast. The danger is great.”81 The Missoulian consistently advocated self-determination in the newly liberated territories of the world, including China. In a line that Wonnacott would later celebrate in her letter to the editor, the Missoulian opined: “If Chiang Kai-shek cannot win without American soldiers, what should happen seems reasonably obvious. We shouldn’t fight anybody’s war but our own and this is not ours.”82 The angst of uncertainty without clear national purpose rippled across the nation.

The Missoulian’s editorial position of nonintervention reflected a national trend of which President Truman was well aware. On Armistice Day, 11 November 1945, Truman hosted British prime minister Clement Attlee and Canadian prime minister W. L. Mackenzie King in a ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery.83 At this solemn event, the Army combat veteran undoubtedly reflected on the tremendous sacrifice of two costly world wars. The situation in China, however, was also likely on Truman’s mind. The same day, Truman saved a compilation of six geographically dispersed editorials about American policy toward the “Civil War in China.”84 The Christian Science Monitor opined that the United States was involved in “a degree of intervention which American opinion will not support even in Latin America and to which it violently objects when followed by others.”85 The Milwaukee Journal predicted a long struggle in China and concluded that “it is not an American responsibility to furnish arms . . . or one American life to settle this Civil War.”86 The Hartford Courant highlighted the duplicitous appearance of American intervention and that the United States should be “scrupulous in avoiding actions that at least can be interpreted as giving military support to Chiang.”87 Reflecting the lack of clarity in the U.S. position, the New York Times offered Truman “a way out” of the “East Asia tinder box” by advocating “a more forthright diplomacy.”88 Earlier that week, on 7 November Secretary of State Byrnes announced that “plans were underway to withdraw the marines,” but hedged his statement by noting that “marine participation in China is a military, and not a political matter.”89 Truman likely hoped that this statement would calm American anxieties about America’s role in China’s internal strife, but throughout the remainder of 1945, wives and mothers continued to keep the pressure on.

Even small-town newspapers regularly carried disturbing news of the growing peril in North China, much to the chagrin of awaiting families. Newspapers.com, Havre (MT) Daily News, 8 November 1945

Wives of deployed Marines engaged government officials on the geopolitics of the confusing U.S. policy in North China. If the Truman administration thought it could lay a smokescreen of diplomatic jargon and buy time against a distracted public, Marine wives proved the diplomats and politicians mistaken. Some spouses felt that assisting Chiang Kai-shek was tantamount to fighting for a kind of fascism so many sacrificed to defeat in World War II.90 Josephine McBroom Junge wrote, “We asked these men to fight, in Tarawa, and in Iwo Jima, and in Okinawa—for democracy. Many are dead. Many are crippled . . . can we ask them now to fight in China—against democracy?”91 The nuanced logic of America’s China policy failed to convince interested life partners. Lucy Bell pointed out the hypocrisy of the Nationalist Chinese forces using armed Japanese troops—that the Marines were in North China ostensibly to disarm—to guard infrastructure from Communist attacks. “Sir, I am not a person who is familiar with the intricacies of diplomacy,” Bell wrote with a dash of sarcasm, “but I call our military operations . . . out-and-out intervention on the side of the Chungking government.”92 Mrs. B. P. Pope agreed that her husband had no business tipping the scales for Chiang Kai-shek’s forces. “The war is over . . . China should take care of her own internal affairs,” she wrote, repeating a line from Mansfield’s speech just days earlier. Pope concluded, however, with a common sentiment all Marine families shared: “We need him home now—he has done his duty.”93

While military family members were personally and politically engaged, the pervasive news stories about the Marines and the Chinese Civil War acutely raised public awareness in late 1945. In periodic headlines and front-page stories from October to December 1945, even small-town newspapers delivered the United Press and Associated Press’s stories from North China that emphasized the complicated position the Marines were in.94 In this bombardment of news stories from China, citizen groups mobilized with letter-writing campaigns, meetings, and advertisements.

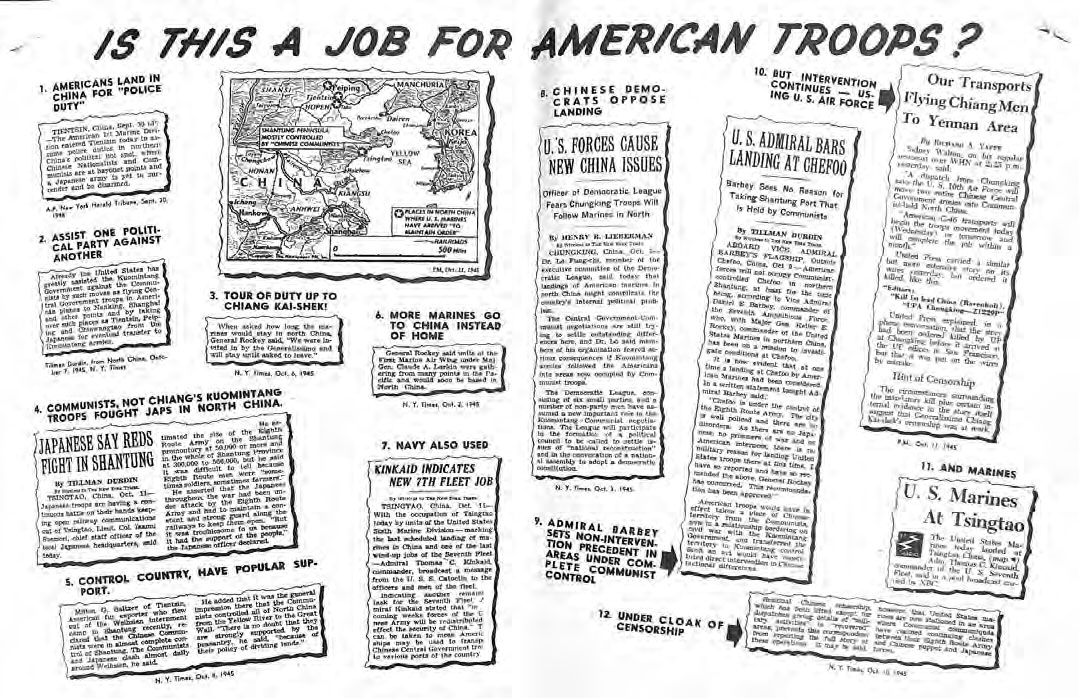

Excerpt from the Committee for a Democratic Policy for China, 1945. Series 4, box 26, folder 5, Mike Mansfield Papers, Archives and Special Collections, University of Montana

Some organized labor groups rallied around an antifascist, anti-imperialist, anticapitalist stance toward postwar Asia. In this criticism, the “Four Freedoms” rationale for World War II contrasted sharply with the murky aims in North China, leading to speculation that intervention in China benefited only “the interests of big monopoly capital,” which mirrored sentiments from enlisted Marines.95 One such group, the Cascade County Trades and Labor Assembly, promulgated its resolution for withdrawal of Marines from North China in both the local newspaper and in letters to congressional leaders, writing even to members outside of their respective districts.96 Farmers in tiny Westby, near the North Dakota border, also demanded not only the precipitous withdrawal of American forces, but a cessation of all forms of U.S. aid to Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist government.97

Reflecting the local labor response and anti-imperialist rhetoric, Communist-aligned organizations like the Committee for a Democratic Far Eastern Policy and the National Committee to Win the Peace mobilized for an end to the American support of Chiang’s government and a redeployment of American forces. Like mothers, wives, and siblings, these citizen groups challenged the foreign policy actions of the United States that meddled in the internal affairs of an ally. In a harbinger of Cold War dilemmas to come, Americans stood for freedom and democracy, but such clear outcomes remained aspirational at best in Chiang’s China. Communist-aligned groups made significant hay of this uncomfortable fact. While ostensibly neutral, American forces in North China tipped the scales in favor of a “regime that has denied basic civil rights to the Chinese people.”98 After fighting a national war against totalitarian fascism and liberating the world, a more nuanced policy fell flat in the court of public opinion, and citizens groups played a key role in galvanizing the opposition.

Both the Committee for a Democratic Far Eastern Policy and the National Committee to Win the Peace benefited from respected leaders and spokesmen. One colorful individual associated with both far-left activist committees was the decorated Brigadier General Evans F. Carlson. Carlson’s illustrious career included time as an observer with Mao Zedong’s forces in the late 1930s. Carlson admired the fighting spirit and camaraderie exhibited by Mao’s Communist fighters and promoted several organizational and tactical innovations the Marine Corps adopted during World War II. Introducing the Marine Corps to the Chinese phrase gung-ho, Carlson led troops at Makin Island, Guadalcanal, and Tarawa, receiving three Navy Crosses and two Purple Hearts for these actions.99 Suffice it to say, Carlson spoke with universally respected authority about China, combat, and the Corps. Addressing the California Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) convention in December 1945, Carlson praised the labor union’s resolution demanding a rapid return of Marines from China. “It is not compatible with democratic ideals for the United States to intervene in the affairs of any other country,” Carlson opined to the crowd. At key moments in the China policy debate through 1946, Carlson effectively rallied public opinion, Congress, administration officials, and media through a grassroots network of volunteers.100

Newspapers, Congress, and the State Department took notice of the strong wave of public opinion crashing down on American China policy in late 1945. Slow to catch on, the Truman administration lost the crucial opportunity to shape the narrative and convince the American people of why U.S. stabilization of North China was essential to the postwar order. Carlson’s mobilization of labor unions and committees resulted in a wave of telegrams and letters to Congress, the State Department, and the White House. Further complicating the public relations crisis, on 27 November, Major General Patrick J. Hurley resigned as ambassador to China and released a bombshell letter that excoriated “the Hydra-headed direction and confusion of our foreign policy.”101 Truman, still privately committed to supporting Chiang, reached deep for a game-changing trump card.102 At a cabinet luncheon, Truman adopted a suggestion that he replace Hurley with the widely admired and nonpartisan General George C. Marshall. President Truman called Marshall at his Leesburg, Virginia, home and asked him to serve as his “Special Ambassadorial Envoy to China.” The quintessential five-star public servant made no attempt to extend his one-day-old retirement, replying only with “Yes, Mr. President.”103 As Marshall arrived in China to try to bring the warring factions together, Dean Acheson, acting secretary of state, painted the mood of the American electorate to Marshall in a classified cable: “Communications are practically unanimous in opposing US participation in the Chinese civil war . . . the CIO and Communist communications are coming in such quantity to suggest an organized drive.” Just in case the left-wing politics of the organizations gave cause for Marshall to dismiss the implications, Acheson’s analysis noted that “other communications are so varied and the geographical spread is so great . . . that the protests represent a strong feeling among people who are acting, for the most part, spontaneously.” Acheson’s conclusion was atypically blunt: “The use of US troops in China is unpopular with the American people.”104 If Marshall considered leveraging American force to bring the Communists and Nationalists to the bargaining table, the tide of American public opinion effectively constrained military alternatives.

Conclusion

The United States avoided stumbling into a quagmire in North China because the American people rallied against it strongly at the outset. The dearth of public support ultimately constrained the policy options for the Truman administration and the president turned to perhaps the most admired man in the country, General Marshall, to calm the political waters. In the wake of the savagery of the Second World War, the American populace—including its hardened Marines—possessed little appetite to extend the war beyond defeating the Axis powers. Wartime censorship laws shielded the public from the true ugliness of blood-stained volcanic beaches, but if Marines questioned why they should die to seize a tiny unknown island, the thoughts were kept close to each Marine. In his epic memoir With the Old Breed, Corporal Eugene Sledge reflected about how combat with the 1st Marine Division changed him: “Something in me died at Peleliu . . . I lost faith that politicians in high places who do not have to endure war’s savagery will ever stop blundering and sending others to endure it.”105 As Marines like Sledge endured the hard slog across the Pacific, they did so with little expectation of survival, but at least each Marine understood the larger purpose of their peril. The sudden end of the war changed that in an instant. Indeed, it transformed the consciousness of the American people as peace at last seemed possible. In a representative democracy, failure to heed popular sentiment would change the government—something President Truman saw firsthand as Prime Minister Winston Churchill went down in a shocking electoral defeat in July 1945.106 Caught flatfooted at the outset of the Cold War, the Truman administration never delivered the affirmative case for U.S. intervention in China.

Marines were important agents of American policy in North China. The III AC faced a nuanced mission and minimized risk however possible. While the Americans still encountered dangerous firefights with Communist forces, strict rules of engagement and rigid adherence to discipline deescalated tension in contingent moments. Instead of employing their vast firepower advantages of artillery and aircraft, leathernecks flew aircraft in unarmed shows of force and maintained a semblance of frustrating neutrality. The leadership, from General Rockey on down, did not advocate the deployment of more troops or seek to expand the role of the mission, although ample opportunities to do so existed. Finally, the removal of wartime censorship protocols permitted Marines to make their voices heard in Congress and to the American people.

Mothers, wives, and citizen groups questioned U.S. policy in China in a manner difficult to ignore. As the national mobilization for World War II ramped down, families anxiously awaited the safe return of their loved ones. Across America, the loss of numerous servicemembers left countless communities scarred. In a national effort against an existential threat, Americans accepted casualties as a solemn patriotic duty, but intervention in China’s internal affairs was another matter. A flurry of letters to newspapers and congressmen originated from apprehensive family members, but rather than simply pining for a husband, ordinary women displayed extraordinary agency in challenging the Truman administration’s policy on the merits of freedom, antifascism, and democracy. Citizens groups, particularly labor unions like the CIO and the Committee for a Democratic Far Eastern Policy, organized effective opposition on moral grounds. Respected spokesmen like the heroic General Evans Carlson effectively portrayed Chiang Kai-shek’s government as nondemocratic and on balance as more like fascist Japan and Germany. Absent a coherent messaging campaign from the Truman administration, these policy punches landed points with an American populace that embraced the role of liberator but not that of meddler.

In the official government retrospective, the public opinion of an informed and active electorate played a key role in China policy. In 1949, with the Cold War firmly entrenched and the Chinese Communist victory all but certain, the Truman administration issued the “China White Paper” in response to a new public fervor over “who lost China.”107 Secretary of State Acheson wrote on the first page that “the inherent strength of our system is the responsiveness of the Government to an informed and critical public opinion.” In his narrative description of the 1945–46 period, Acheson opined that “the Communists probably could have been dislodged only by American arms,” but it was “obvious that the American people would not have sanctioned such a colossal commitment of our armies in 1945 or later.”108

At the conclusion of a titanic war that Americans ostensibly fought for freedom and democracy, perhaps it was appropriate that Marines and mothers would organize, debate, and help shape American postwar foreign policy. For Warren Peterson, Ethel and Gilbert Wonnacott, and countless other Marines and family members, intervention in North China was more than a moral, anticommunist, or proto–Cold War position—it was profoundly personal. These unlikely political actors shaped U.S.-China policy at a key moment in 1945–46 when the trap lines of counterinsurgency, nation building, and regional conflict menacingly lurked in the Chinese swamp. Their voices were heard.

•1775•

Endnotes

- 1940 United States Federal Census, Ravalli County, MT, Population Schedule, Stevens Township, Enumeration District 41-14, Sheet 3B, Household 57, Ethel Wonnacott, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), 1940, T627, Roll: m-t0627-02227.

- PFC Gilbert E. Wonnacott, 2d Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment, muster rolls, July 1945, vol. 9, NARA. Wonnacott served with Company G

- Chinese place names and historical actors appear primarily in the Pinyin form, with the Wade-Giles transliteration in parentheses at first use. For example, Beijing (Peiping), Tianjin (Tientsin), Chongqing (Chungking), Shandong (Shantung), Hubei (Hopeh), Mao Zedong (Mao Tse-tung), and Zhou Enlai (Chou En-lai). The more well-known form of Chiang Kai-shek is used instead of Jiang Jieshi. The primary source documents and images reflect the Wade-Giles romanization, which was the custom in 1945–46.

- Henry I. Shaw, The United States Marines in North China, 1945–1949 (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1960), 3–5.

- “Parade after Japanese Surrender, 1945,” John C. McQueen Collection, Collection 64, Archives, Marine Corps History Division (MCHD), Quantico, VA.

- Richard Bernstein, China 1945: Mao’s Revolution and America’s Fateful Choice (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2014), 65–69.

- James Chieh Hsiung and Steven I. Levine, eds., China’s Bitter Victory: The War with Japan, 1937–1945 (Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 1992), 203–4.

- Winston S. Churchill, Memoirs of the Second World War (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1959), 753; Odd Arne Westad, Cold War and Revolution: Soviet-American Rivalry and the Origins of the Chinese Civil War, 1944–1946 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993), 9; and Tang Tsou, America’s Failure in China, 1941–1950 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1963), 35.

- Herbert Feis, China Tangle: The American Effort in China from Pearl Harbor to the Marshall Mission (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1953), 248–54.

- Marc S. Gallicchio, The Cold War Begins in Asia: American East Asian Policy and the Fall of the Japanese Empire (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988), 56–57.

- Gallicchio, The Cold War Begins in Asia, 120.

- Gallicchio, The Cold War Begins in Asia, 19–37.

- Gallicchio, The Cold War Begins in Asia, 75.

- Westad, Cold War and Revolution, 104–5.

- Benis M. Frank and Henry I. Shaw, Victory and Occupation: History of the U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II, vol. 5 (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1968), 533.

- Westad, Cold War and Revolution, 78–79.

- Gallicchio, The Cold War Begins in Asia, 97.

- Mike Mansfield, “Situation in China,” Congressional Record 91, no. 210 (11 December 1945): 12031–34.

- Mr. Mansfield, “American Policy in the Far East,” Congressional Record 91, no. 210 (11 October 1945): 9629–30; “U.S. Erred in North China, Foreign Policy Body Hears,” Cincinnati (OH) Enquirer, 10 October 1945; and Don Oberdorfer, Senator Mansfield: The Extraordinary Life of a Great American Statesman and Diplomat (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Books, 2003), 86–87.

- “U.S. Erred in North China, Foreign Policy Body Hears.”

- Speech Notes, October 1945, series 4, box 2, folder 1, Mike Mansfield Papers, Archives and Special Collections, Mansfield Library, University of Montana, hereafter Mansfield Papers.

- Mansfield, “American Policy in the Far East,” 9629–30.

- Under Secretary of State (Acheson) to Representative Hugh De Lacy, 9 October 1945, in Foreign Relations of the United States: Diplomatic Papers, 1945—The Far East, China, vol. 7 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1969), 577–78, hereafter FRUS, China.

- Memorandum by the Director of the Office of Far Eastern Affairs (Vincent) to the Under Secretary of State (Acheson), in FRUS, China, 580–81.

- John Carter Vincent to Dean Acheson, memo, “American Marines in North China,” 16 October 1945, Chinese Civil War and U.S.-China Relations: Records of the Office of Chinese Affairs, 1945–1955, Top Secret, 1945 410.003 Naval Activities Affecting China, NARA via GALE Databases.

- The Chargé in China (Robertson) to the Secretary of State, telegram, 14/15 October 1945, in FRUS, China, 579–80.

- First Session of the Council of Foreign Ministers, London, 11 September–2 October 1945, in Foreign Relations of the United States: Diplomatic Papers, 1945, General—Political and Economic Matters, vol. 2 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1967), 99–559.

- Ambassador in the Soviet Union (Harriman) to the Secretary of State, telegram, 17 October 1945, in FRUS, China, 581–82.

- Mr. Mansfield, Congressional Record 91, no. 210 (30 October 1945): 10204–5.

- Consul at Tientsin (Meyer) to the Secretary of State, telegram, 30 October 1945, in FRUS, China, 599–600.

- “Yank Intervention Charged by Reds,” Havre (MT) Daily News, 5 November 1945.

- Mansfield letter to President Truman, 7 November 1945, series 4, box 26, folder 5, Mansfield Papers.

- “US Marines Soon to Be Withdrawn,” Montana Standard (Butte), 8 November 1945.

- “6th Mar Div Op Ord Annex A,” 18 September 1945, Papers, WWII, China, box 1, folder 2/1, Archives, MCHD.

- Frank and Shaw, Victory and Occupation, 533–42. “Puppet” troops were local Chinese troops serving under the authority of the Japanese government.

- Letter to Mansfield from the Enlisted Men of the 3220th E.F.S.P.D., Nagoya, Japan, 12 January 1946, series 5, box 111, folder 3, Mansfield Papers. This letter included the signatures of 36 enlisted. Letter to Mansfield from the Forgotten Men of the Pacific, from Guam, 14 January 1946, series 5, box 111, folder 3, Mansfield Papers. The numerous letters in the Mansfield Papers from Army, Marine, and Army Air Corps units in Manila, Korea, Japan, Burma, India, and China, suggest a widespread and vocal opposition to the maintenance of a large-standing overseas occupation force.

- Letter to the American People copied to Mansfield from Your Affectionate Sons, from the South Pacific, January 1946, series 5, box 111, folder 3, Mansfield Papers.

- Letter to Mansfield from the Men of the Detachment Stationed in Ching Wang Tao, China, part of the 1st Marine Division, 16 October 1945, series 4, box 26, folder 5, Mansfield Papers.

- Letter to Mansfield from Warren Peterson, 6 December 1945, series 4, box 26, folder 4, Mansfield Papers.

- President Truman to Gen Marshall, U.S. Policy Towards China, 15 December 1945, FRUS, China, 770–73.

- “Lieutenant General Keller E. Rockey, USMC (DECEASED),” Marine Corps History Division, accessed 6 May 2022.

- Frank and Shaw, Victory and Occupation, 544.

- Frank and Shaw, Victory and Occupation, 548.

- E. R. Hooton, The Greatest Tumult: The Chinese Civil War, 1936–49 (London, UK: Brassey’s, 1991), 18–19.

- Commanding General, United States Forces, China Theater (Wedemeyer), to the Chief of Staff, United States Army (Marshall), telegram, 14 November 1945, FRUS, China, 628.

- “6th Mar Div Op Ord Annex A,” 18 September 1945, Papers, WWII, China, box 1, folder 2/1, Archives, MCHD.

- Frank and Shaw, Victory and Occupation, 559.

- Frank and Shaw, Victory and Occupation, 559.

- “Navy Cross Citation, Major Keller E. Rockey, USMC, December 11, 1929,” Hall of Valor Project, accessed 2 March 2021.

- Frank and Shaw, Victory and Occupation, 559–93. Shows of force were designed to showcase superior American mobility, firepower, and technology. The missions drew regular ground fire, contributing to 22 aircraft losses, but the Marines’ strict rules of engagement prevented aircraft from routinely shooting back. A mandated minimum elevation of 5,000 feet above ground level minimized the probability of effective ground fire.

- Frank and Shaw, Victory and Occupation, 558.

- Cpl Taylor to Mike Mansfield, 30 October 1945, series 4, box 26, folder 5, Mansfield Papers.

- Frank and Shaw, Victory and Occupation, 585–86.

- After years of conflict in North China, armed banditry was ubiquitous.

- “Marines Shell Village in North China,” Great Falls (MT) Tribune, 9 December 1945.

- “Marines Shell Village in North China,” Great Falls (MT) Tribune, 9 December 1945.

- “Semper Fidelis,” Washington Post, 12 December 1945, 6.

- Mansfield letter to Gen A. A. Vandegrift, 31 December 1945, series 4, box 25, folder 4, Mansfield Papers.

- A. A. Vandegrift letter to Eugene Meyer, 1 February 1946, series 4, box 26, folder 4, Mansfield Papers.

- Letters Presented to the Congressional Record, 13 December 1945, Burton Kendall Wheeler Papers, MC 35, box 21, folder 2, Montana Historical Society Research Center, Archives, Helena, MT; and Demobilization, series 5, box 111, folders 3–6, Mansfield Papers.

- “Pacific Veterans Press for Return,” New York Times, 5 December 1945.

- Gallichio, The Cold War Begins in Asia, 120.

- Redeployment (CBI), series 4, box 26, folders 5–7, Mansfield Papers.

- Letter from Mike Mansfield to C. Peterson, 12 November 1945, series 4, box 26, folder 5, Mansfield Papers.

- Letter to Mansfield from the Men of the Detachment Stationed in Ching Wang Tao, China. This handwritten letter was clearly penned by a single author but signed as a group letter. 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, augmented by Company F, 2d Battalion, 7th Marines, and Company G, 2d Battalion, 11th Marines, was garrisoned near Qinhuangdao when this letter was written. Marines were continuously stationed in North China after the 1900 Boxer Rebellion until 8 December 1941. “China Marines” were veterans of the pre–World War II era and lived well on American salaries in the Chinese economy.

- “1st Marine Division Daily Newssheet,” 13 October 1945, series 4, box 26, folder 5, Mansfield Papers.

- Letter from Warren Peterson, 26 October 1945, series 4, box 26, folder 5, Mansfield Papers.

- Letter from Cpl David W. Taylor, 30 October 1945, series 4, box 26, folder 5, Mansfield Papers.

- Letter from PFC Warren Peterson, 6 December 1945, series 4, box 26, folder 5, Mansfield Papers, hereafter 6 December Peterson letter.

- 6 December Peterson letter.

- 6 December Peterson letter.

- Letter from Mike Mansfield to Warren Peterson, 31 December 1945, series 4, box 26, folder 5, Mansfield Papers.

- “Op Order IIIAC,” September 1945, Papers, WWII, China, box 1, Archives, MCHD.

- Consul at Tientsin (Meyer) to the Secretary of State, 16 November 1945, FRUS, China, 635.

- Richard Overy, Why the Allies Won (New York: W. W. Norton, 1997).

- American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2020), 2, 33.

- This assessment is based on detailed archival research in the Mansfield, Murray, and Wheeler papers. A wider view was constrained by lack of archival access during the COVID-19 pandemic. While written to a Montana congressman, numerous letters in these archives also originate from Maryland, New York, Illinois, Texas, Utah, Virginia, and Washington, indicating a geographic diversity with a similar viewpoint.

- Families displayed a blue star for each family member in service. The gold star represented the ultimate sacrifice.

- Letter from Mrs. R. M. Wonnacott, 9 December 1945, series 4, box 26, folder 4, Mansfield Papers.

- Letter from Mrs. R. M. Wonnacott, 9 December 1945, series 1, box 216, folder 4, James E. Murray Papers, Archives and Special Collections, Mansfield Library, University of Montana.

- “The U.S. and China,” Missoulian (MT), 19 December 1945.

- Editorial, Missoulian (MT), 10 December 1945.

- President’s Daily Appointment Calendar, 11 November 1945, Harry S. Truman Papers, Truman Library, Independence, MO.

- “Civil War in China, Editorial Opinion on Policy,” New York Times Overseas Weekly, 11 November 1945, Harry S. Truman Papers, President’s Secretary Files (HST-PSF), Foreign Affairs File 1940–1953, China 1945, NARA.

- “American Policy,” Christian Science Monitor, as quoted in New York Times Overseas Weekly, 11 November 1945.

- “For No Participation,” Milwaukee (WI) Journal, as quoted in New York Times Overseas Weekly, 11 November 1945.

- “Keep Out of China,” Hartford (CT) Courant, 5 November 1945.

- “The Chinese Tinder Box,” New York Times, 10 November 1945.

- “Exit of Marines from China Is Set,” New York Times, 8 November 1945.

- That Americans in 1945 could interpret Mao Zedong as a democrat suggests that Mao’s information campaign was initially successful. This was also perpetuated by correspondents Theodore H. White and Edgar Snow to popular audiences in Thunder Out of China and Red Star Over China, respectively.

- Letter to Mansfield from Mrs. Josephine McBroom Junge, 4 November 1945, series 4, box 26, folder 5, Mansfield Papers.

- Letter to Mansfield from Mrs. Lucy Bell, 30 October 1945, series 4, box 26, folder 5, Mansfield Papers.

- Letter to Mansfield from Mrs. B. P. Pope, 16 October 1945, series 4, box 26, folder 5, Mansfield Papers.

- “Chinese Angered by U.S. Marines,” Billings (MT) Gazette, 7 December 1945; “Boxer Troubles Recalled,” Great Falls (MT) Tribune, 12 October 1945; “News Blackout Follows Reported Seizure of American Seamen,” Helena (MT) Independent Record, 7 November 1945; “Marines Land in China to Assist Chiang Control Last Jap-Dominated Area,” Daily Interlake (Kalispell, MT), 8 October 1945; “Marines Angered,” Missoulian (MT), 17 November 1945; “Fighting Reported in 11 Areas of Disjointed China: American Marines Walking Tightrope to Maintain Order,” Montana Standard (Butte), 31 October 1945; “Removal of U.S. Troops from China Is Urged,” Baltimore (MD) Sun, 12 October 1945; “Marines’ Clash in China Makes Another Crisis,” Chicago (IL) Daily Tribune, 10 December 1945; “Peril for Marines Seen in China War,” New York Times, 31 October 1945; and “Marines in China Rescue Japs from Angry Crowds,” Washington Post, 15 October 1945.

- “Labor Council Wants Troops Out of China,” Great Falls (MT) Tribune, 11 December 1945.

- Letter from the Cascade County Trades and Labor Assembly, 4 November 1945, series 4, box 26, folder 5, Mansfield Papers.

- Letter from the Farmers Educational and Co-operative Union of America, Local 359, 24 November 1945, series 4, box 26, folder 5, Mansfield Papers.

- “Why Send U.S. Troops to China Now?,” Committee for a Democratic Policy Towards China, October 1945, series 4, box 26, folder 5, Mansfield Papers.

- “Brigadier General Evans Fordyce Carlson, USMCR,” Marine Corps History Division, accessed 5 May 2022.Suffice it to say, Carlson spoke with universally respected authority about China, combat, and the Corps. Addressing the California Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) convention in December 1945, Carlson praised the labor union’s resolution demanding a rapid return of Marines from China. “It is not compatible with democratic ideals for the United States to intervene in the affairs of any other country,” Carlson opined to the crowd. At key moments in the China policy debate through 1946, Carlson effectively rallied public opinion, Congress, administration officials, and media through a grassroots network of volunteers.100

- “National Committee to Win the Peace Demanding Action,” Emporia (KS) Gazette, 8 April 1946

- Ambassador in China (Hurley) to President Truman, 26 November 26, 1945, FRUS, China, 724.

- Meeting with President Truman, Personal Memorandum, 27 November 1945, series 19, box 604, folder 16, Mansfield Papers.

- Daniel Kurtz-Phelan, The China Mission: George Marshall’s Unfinished War, 1945–1947 (New York: W. W. Norton, 2019), 10–14.

- Acting Secretary of State to the Chargé in China, telegram, 20 December 1945, FRUS, China, 786.

- E. B. Sledge, With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 156.

- Churchill, Memoirs of the Second World War, 995–97.

- Tsou, America’s Failure in China, 1941–1950, 507–9.

-

United States Relations with China, with Special Reference to the Period 1944–1949 (New York: Greenwood Press) iii, x.