PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: Quite often, representations of the Marine Corps during World War II included gendered elements that reflected the institution’s beliefs about men and women, their place in society, and acceptable gender roles. The U.S. military has long struggled with negotiating gender, and the hypermasculine nature of the military— and the emphasis the Marine Corps, in particular, placed on maintaining ideal masculinity—influenced the relationship between masculinity and femininity for servicemembers, and the images produced by and about the Marine Corps impacted the appearance of gender norms in the military context. Women Marines’ presence both challenged and reinforced the Corps’ hypermasculine reputation and image as warriors by means of the representation of women’s bodies and labor.

Keywords: World War II, Women Marines, bodies, Marine Corps image, reputation, gender norms, gender roles, feminine, feminine ideal, femininity, masculine, masculine ideal, masculinity

Introduction

In 1943, Miriam Galpin traded correspondence with her sister and her sister’s husband about her plans for the future. She was young, only about 20 years old at the time, and dreamed of joining the Marine Corps to patriotically serve her country during World War II. While Galpin was most interested in entering the Corps’ officer program, she did not al- low an initial rejection to stop her ambitions to serve. Instead, Galpin enlisted, explaining in her letters to her family that she hoped with time and effort to earn her way into officer training. While Galpin quickly learned that her previously held romanticized notions of service in the Corps were less than accurate, she remained excited about the challenges and opportunities the Corps presented. She was assigned to Marine Corps Headquarters in Washington, DC, and worked in the payroll office. For Galpin, this opportunity included the chance to extend her social life and meet new people. In fact, in July 1945, she married a Marine she met while she was in the Service.2

In many ways, Miriam Galpin’s experience reflected typical images of Women Marines frequently used by the Corps to protect its reputation and encourage the type of individuals it wanted to enroll in the Service. Galpin was young, single, and white. Physically and socially, she fit the image the Corps was trying to project, making her a good fit as a Woman Marine. She also conveyed a feminine yet professional appearance and eventually married a fellow Marine as the war came to an end, retiring from the military and returning to civilian life. A combination of similar traits allowed the Corps to call on women like Galpin without violating the civilian social norms that demanded women remain separated from military service except in extreme circumstances. In its treatment of Women Marines, the Corps both reinforced existing civilian gender norms and created methods of incorporating them into the Marine Corps. The version of femininity found in the Corps would have been generally recognizable to civilians, allowing these women to reintegrate into civilian life when their service was complete. The Corps started with an existing concept of ideal American womanhood and found ways to make it fit both civilian ideas of femininity and the Corps’ idea of what an elite Marine should look and act like. Given that these concepts of femininity fit within their existing worldview, most Women Marines likely did not challenge the broad outlines of the Corps’ regulations, though questions and resistance surrounding certain aspects of these rules certainly occurred, as reflected in the Marine Corps’ near constant commentary on the behavior of both male and female Marines. While not every Marine experienced their service in ways that mirrored common representations of the Corps and the Marines who served, many of these commonly held images and stereotypes included an element of reality.

Hypermasculinity and Women Marines

Quite often, these representations of the Corps included gendered elements that reflected the institution’s beliefs about men and women, their place in society, and acceptable gender roles. The U.S. military has long struggled with negotiating gender within its confines, in reality and representation, and wrestled with methods of controlling Women Marines’ bodies and images of their bodies to shape and protect the Corps’ reputation.3 The hypermasculine nature of the military and the emphasis the Marine Corps, in particular, placed on maintaining ideal masculinity, influenced the relationship between masculinity and femininity for both servicemen and -women, and the images produced by and about the Marine Corps impacted the appearance of gender norms in the military context. Hypermasculinity in the Corps meant excelling in combat, striking an attractive figure, and perpetuating the idea that Marines were the toughest and most elite branch of the U.S. military.4 Women Marines’ presence both challenged and reinforced the Corps’ hypermasculine reputation and image as warriors by means of the representation of women’s bodies and labor. The contradiction inherent in these women’s presence as Marines required that the Corps grapple with how to remain hypermasculine when some of its members were female. Rather than encouraging Women Marines to strive for masculinity, the Corps emphasized their femininity and adherence to civilian gender norms. Women Marines were held to a strict concept of pragmatic femininity that allowed them to serve as Marines without either acting in ways contrary to contemporary civilian gender norms or altering the Corps’ internal culture. These women were simultaneously part of the Corps and yet separate from it, and their adherence to feminine ideals served to emphasize their male colleagues’ masculinity.

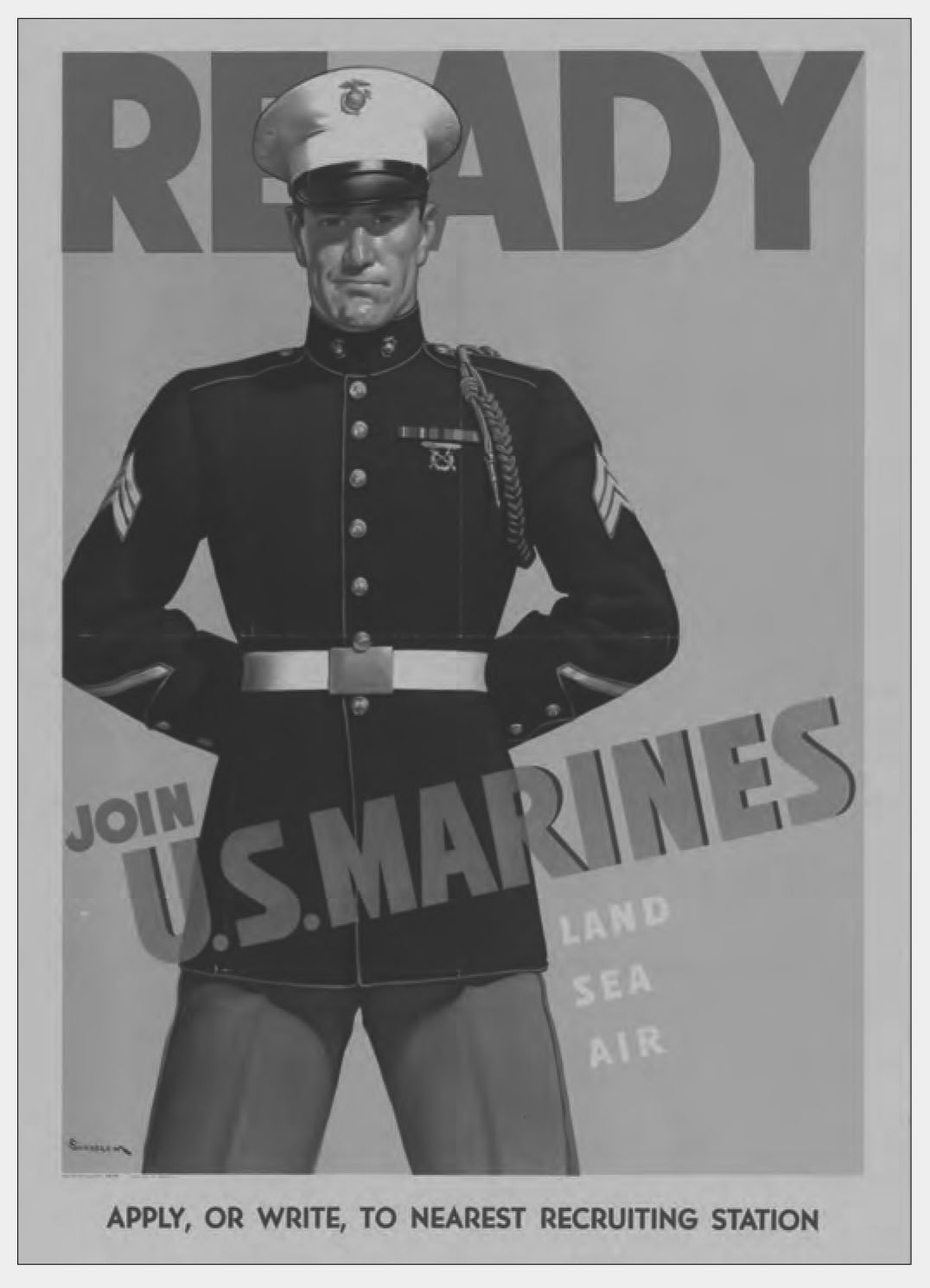

Though women entered the Marine Corps during World War I, larger numbers joined the Corps during the Second World War. The increased number of women involved in the Marines meant important changes were happening in the perception of the ideal Marine. If women’s bodies were to be accepted as Marine bodies, the masculine ideology underlying the Corps’ image had to adapt and find ways of explaining Women Marines.5 The presence of women’s bodies in militarized contexts directly impacted the perception and presentation of men’s bodies as well, requiring images showing both men and women Marines working together, as well as images that highlighted the martial aspects of men’s service.6 These images, such as the recruitment poster in figure 1, reinforced existing gender norms for both men and women even within the context of the Corps by illustrating the embodiment of the Marine Corps ideal.

The Marine in this poster illustrates the masculine image the Corps sought. The man is tall, strong, attractive, and wearing a meticulously cared-for uniform. He stands at parade rest, ready for his next order. Images of Women Marines were created in the context of this type of image and were intended to complement male Marines.7

Figure 1. Marine Corps recruiting poster.

Domestic Operations Branch, and Bureau of Special Services, Office of War Information, Office for Emergency Management, U.S. Marine Corps, “Ready. Join U.S. Marines,” poster, undated, 1941–45, Series: World War II Posters, 1942–45, RG 44, NARA

While gendered portrayals of male and female Marines followed broader societal norms in many ways during World War II, certain aspects of the Marine Corps image remained true regardless of gender. The pieces of the Marine uniform varied depending on gender, but the emphasis on attention to detail, neatness, and uniformity remained consistent. Women Marines were not supposed to look the same as male Marines; rather, they needed to appear simultaneously as women and Marines. The Corps concerned itself with maintaining its female members’ femininity even as they took on jobs and military-style uniforms generally associated with masculinity. The health and wellness of women’s bodies was also a concern. While the Marine Corps concerned itself more closely with the promiscuity of Women Marines and the potential detrimental impact on their reputations, Service and public concerns included the morality and health impact of men’s promiscuity as well. The Corps and the American public worried about the health of male and female Marines, who might experience exposure to venereal diseases that would impact the health of their bodies and the military readiness of the Corps.8

In spite of the similarities in the concerns with men’s and women’s adherence to the Marine Corps’ concepts of ideal appearance and behavior, both sexual and otherwise, expectations for women differed from those for their male counterparts in ways that largely mirrored broader American society. Women’s status as mothers and potential mothers was emphasized and protected by the Corps’ policies. For example, the focus on women’s bodies and respectability with regard to sexual behavior sought to ensure retired Women Marines would not have trouble finding husbands and starting families, goals assumed to apply to all women during this era. Respectability played an important part in both the Corps and American society’s understanding of gender norms for both male and female Marines. Though respectability appeared somewhat differently for male and female Marines, concepts of good health and hygiene, morality, behavior, and personal appearance shaped expected standards of respectability and image for all Marines. Normative ideas of gendered labor were also protected within the framework of the Corps. Women worked in certain areas, far away from combat, and the expectation remained that women would return to the civilian world, marry, and become mothers as soon as the war ended. In this way, the Marine Corps attempted to protect women’s bodies and to use them to reinforce its image and reputation in a rapidly changing world. As previously stated, this reputation portrayed Women Marines as feminine, competent, young, attractive, and white during this era. The emphasis on whiteness would soon have to be addressed with the inclusion of African American Women Marines starting in 1949.9

Historiography

Aaron Belkin and Christina Jarvis have already produced books explaining the significance of the connection between military bodies and gender considered here, though neither provides much comment on women. Aaron Belkin’s Bring Me Men explains much of the Marine Corps’ preoccupation with bodies, putting gender identity in the military into a more complex and nuanced context, especially focusing on masculinity’s centrality to the American military institution. Belkin complicates military masculinity by arguing that it has never been entirely devoid of feminine elements, though the World War II-era Marine Corps and many members of other Service branches would probably have argued otherwise. Aspects of femininity have long been a part of military life, from domestic responsibilities, like cooking and laundry, often associated with women’s labor to close same-sex companionship between soldiers. While generally considered less masculine when taken as separate behaviors, these actions did not seem problematic in a military context, assumed to be devoid of women.10 This leads to the conclusion that the incorporation of women into the military, even the Marine Corps, was not a radical introduction of femininity into a solely masculine environment, but rather a more complex shift in the relationship between gender and occupation. This complex balance between masculinity and femininity existed within the Corps despite its hypermasculine image even before women’s introduction to the Service. This helped create a space for the inclusion of women in limited and gendered ways.11 Belkin makes it clear that feminine space already existed, and evidence suggests that women could be made to fit into those spaces. This meant restructuring ideas about labor to allow women to perform their duty to their country in feminine ways, a goal made easier through the curated use of images of Women Marines.

Christina Jarvis’s The Male Body at War also illustrates the strong connection between the male body, masculinity, and military service, and she argues that the government consciously used both actual and representations of male bodies to assure the American people of their nation’s strength during World War II. Bodies were routinely manipulated, examined, and critiqued for their value—symbolic and physical—to the nation. While Jarvis does not address Women Marines or other military women in her work, servicewomen’s bodies were used and manipulated in ways similar to their male counterparts.12 The Corps’ representation of female bodies assured Americans that the women who served as Marines were up to the challenges required of them, while still being encouraged to perform normative femininity, as contrasted with the assumed masculinity of their male colleagues.

The significance of bodies to the creation and reinforcement of the Marine Corps’ image and reputation is well established. Craig M. Cameron’s American Samurai explores the connection between masculinity, publicity, and the Marine Corps’ image. Likewise, Aaron O’Connell’s Underdogs investigates the intentional ways that Marines presented themselves publicly and highlights the significance of gendered images to the Corps. Finally, Heather Venable’s recent work, How the Few Became the Proud, considers the origins of the Marine Corps image and the connection to concepts of masculinity that became central to the Corps’ identity. This article shows that many of these concepts regarding the Marine Corps’ image apply to Women Marines as well. Cameron, O’Connell, Venable, and others place emphasis on the importance of gendered, especially masculine, images to the Corps and how the portrayal of Marine Corps bodies adapted to the increased presence of military women during WWII.13 The Marine Corps documented its ideas of normative masculine and feminine Marine bodies through pictures, propaganda, and newsletters. The evidence explored here illustrates the complicated and often contradictory relationship between masculinity and femininity that all Marines, male and female, negotiated.

Figure 2. Sgt Ruth Yankee and PFC Corah Wykle, USMCR, make weather observations at Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point, NC. Photo by Lt Paul Dorsey, TR-6220, official U.S. Navy photo

Marine Corps Images

While the U.S. government did not control the advertising and publication industries directly, a mutually beneficial relationship developed between these industries and the government in an effort to persuade the American people to enthusiastically cooperate with war mobilization and military recruitment efforts. This included images and text in various formats intended to portray the military and military service in very intentional and positive ways, supporting recruitment efforts for the U.S. military.14 In this way, the Marine Corps worked with advertisers to create specific images of Marines that appeared in various civilian newspapers and advertisements, as well as Marine Corps publications, in order to attract and retain ideal recruits for its organization. The examples discussed below illustrate an unexpected degree of similarity in the desired traits emphasized for both male and female Marines, a conclusion pursued more elsewhere.15 Even so, Women Marines were encouraged to live up to civilian feminine social norms whenever possible.

Montezuma Red

The Elizabeth Arden company took advantage of the uniquely patriotic and feminine image of Women Marines to sell their products, especially a line of makeup marketed to these women called “Montezuma Red,” which included lipstick, rouge, nail polish, and other coordinating products. The advertisement, which appeared in a 1944 issue of Vogue and numerous other publications, told readers that the company matched this product line to the red detailing on the Women Marines’ uniform, recognizing its significance to Marines (figure 3). The company combined its efforts to sell cosmetics with encouragement for women to “Free a Marine to Fight!” and join the Women’s Reserve, combining ideas of patriotism and service with the femininity and glamour of the cosmetics industry.16 In the advertisement, a Woman Marine with perfect hair and makeup stares romantically off into the distance. Her uniform is immaculate, and the advertisement highlights the woman’s red scarf, the braid on her hat, the rank insignia on her sleeve, and her matching red lipstick and nail polish. This woman’s body highlights the expectations articulated by civilian media and the Corps regarding the ideal appearance of Women Marines. She portrays the elite image of a Marine in uniform while also highlighting her feminine desire to wear attractive makeup.

Figure 3. “Montezuma Red” Elizabeth Arden advertisement. Vogue 103, no. 8, 15 April 1944, 115

The Elizabeth Arden Company also released a publicity pamphlet advertising its makeup line and encouraging women to enlist in the Corps. The brochure copy reads: “It is Miss Arden’s sincere hope that the attention given to her new color harmony, Montezuma Red, will stimulate interest in the Women’s Reserve of the Marine Corps and aid in the recruiting drive of this inspiring branch of the women’s services.” It featured images of attractive women modeling Marine Corps uniforms and completing some of the jobs they might be assigned with the Corps.17 In this brochure, women were encouraged to carefully craft the appearance of their bodies by using cosmetics, both to aid in maintaining male servicemember’s morale by providing a visual reminder of the society these men fought to preserve and by proving their adherence to feminine norms. Military women walked a fine line between proving their usefulness and patriotism and violating societal norms by stepping too far into malecentered spaces. The combination of cosmetics and Marine Corps recruitment illustrated how women could simultaneously contribute to their country’s defense by joining the Corps and carefully attending to their makeup.18

Camel

Cosmetics companies were not the only businesses that traded on the image of military women. The advertisement opposite appeared in several publications, including a 1943 issue of Vogue, and showed an example for Camel cigarettes (figure 4). Women from each Service branch, including the Corps, are shown in uniform, and the advertisement’s text emphasizes these uniforms in conjunction with popular fashion and connect both to using Camel’s product.19

These women appear in carefully tended uniforms with meticulously prepared hair and makeup. Regardless of the job they were performing, they wear skirts and low heels, in keeping with civilian norms for women’s clothing at the time. They display pleasant smiles at each other or the observer, emphasizing the cheerful femininity expected of military women. Each of these women’s bodies was posed to show the ideal military woman. Captions next to each set of servicewomen encourage female readers to join the military in order to free a man for combat, combining fashionability with patriotism and military service. Camel’s advertisement draws attention to similarities in the depiction of women in all Service branches in keeping with civilian gender norms that deserves further consideration but exceeds the scope of this article.

Text-based Images

Newspapers also perpetuated specific, curated images of Women Marines. An article from Philadelphia’s The Evening Bulletin in 1943, titled “Join the Marines and see-Romance [sic]; Girls’ Director here, Gives O.K.,” directly addressed common worries about the connection between women’s bodies and femininity with their ability to serve. The reference to these women as “girls” illustrated the nonthreatening nature of their work by emphasizing their youth and harmlessness, regardless of the fact that not all of these women were particularly young. Through most of this period, Women Marines needed to be at least 20 years old to apply for admission. The article’s author relayed information received from the director of the Marine Corps Women’s Reserve, Major Ruth Cheney Streeter, that Women Marines would be able to seek romantic connections while serving and that participation in the Corps would not be a hindrance to finding a husband. The article stated, “Major Streeter said that neither uniform nor training makes a woman more masculine. But, she said, both uniform and training have brought out qualities of which a woman’s parents and friends may be proud.” Streeter wanted to make it clear that women’s presence in a masculine military setting did not threaten normative American gender roles and servicewomen’s ability to fit into them. These women could still be attractive and marriageable.20 Miriam Galpin’s experiences with dating and marriage reflected these assertions, though the emphasis on women finding future husbands while in the Service directly contradicted rules regulating fraternization between male and female Marines. Women could and were expected to want to marry and have families after their service was completed, and the Corps did not want to stand in the way of Women Marines achieving those goals, even if it raised further questions about antifraternization regulations.

In fact, some sources indicated that these women were perceived as unusually desirable. For example, a newspaper article from 1943 titled “Beauty Isn’t Prerequisite for Girl Marines, Chief Says,” reported Streeter’s view of the public impression that Women Marines were the most attractive of servicewomen. Streeter replied that the Corps was not intentionally selecting attractive women but pointed to recruit training that increased muscle, decreased excess weight, and encouraged good posture as reasons for the perception. The implication seemed to be that joining the Corps made a woman and her body more attractive, even though that was not its main purpose. Though Streeter’s comments worked to minimize the supposed impact of women’s appearance on their selection for service, women’s bodies were clearly considered relevant in both the public eye and to the Marine Corps. The fact that reporters considered asking the director of the Women’s Reserve if attractiveness was an enlistment requirement showed assumptions about women’s value being placed on their appearance, as well as the fact that Women Marines could be objects of physical appreciation. This exchange also illuminates the Corps’ awareness of the significance of the appearance of Marine bodies and the ability of training to transform bodies into more ideal, desirable forms.21 Neither the article’s author nor Streeter explained where this supposedly well-known assumption regarding Women Marines’ attractive appearance originated, though it seems likely this image was tied to broader understandings of the elite Marine Corps image.

Even as the Marine Corps negotiated civilian perceptions of World War II-era Marines in newspapers and advertisements, the Corps generated its own images and discussion in an effort to further shape the narrative of its status and history to its benefit. Public relations and publicity departments connected to the Corps released specific information and images that furthered an official version of what a Marine looked like and how he or she behaved. Such documents often originated with the Office of the Commandant of the Marine Corps, announcements within the Corps, or with the popular Marine-led magazine Leatherneck. 22 Articles and press releases also often originated with the Corps and attempted to influence what the public read and believed about the Corps. These sources assisted in the Marine Corps’ efforts to control the images of the Corps, Marines’ bodies, and gender ideals within the Corps that circulated both inside and outside the organization by informing a wide audience about expectations for being a Marine.

Figure 4. “First in Fashion” Camel Cigarettes advertisement. Vogue 102, no. 22, 1 November 1943

Figure 5. Leatherneck article image. “The Leatherneck Visits Depot of Supplies, Department of the Pacific, San Francisco,” Leatherneck (January 1944): 76

Leatherneck

Leatherneck was a magazine created for Marines by Marines. It started in the late 1910s and discussed many issues that directly impacted members of the Corps, both officers and enlisted. The magazine included advertisements for a variety of products that might interest Marines, notably highlighting uniform sales and tailoring, shoe polish, shaving cream, and toothpaste. Most of these items claimed to improve the appearance of the individuals purchasing them and often showed them as maintaining the high standards of the Corps.23 The magazine was aimed specifically at Marines, targeting their interests and concerns, including concerns related to the arrival of Women Marines.

In a 1944 Leatherneck article discussing Women Marines, the author’s tone indicated general acceptance of women in the Corps and quoted a depot’s quartermaster as saying, “The gals are doing a bang-up job, even better than the men in some instances.”24 The article went on to list some of the jobs women did at that particular post but pointed out that there were jobs that women could not do, such as moving heavy oil drums, emphasizing the limits of Women Marines’ bodies. The article emphasized the enjoyment that women received from their work while freeing male Marines for combat duty. One of the final images in the article (figure 5), indicated the author’s underlying ambivalent feelings toward Women Marines. A photograph published with the article depicted two women working at a drafting table; the caption says that the corporals “seem to know what they are doing” in the drafting department, leaving their competence and expertise uncertain to the reader, in spite of the author’s positive tone toward Women Marines in the rest of the text. The article’s author worked to articulate women’s place and image in the Corps without openly threatening male Marines by highlighting the importance of the work they did while also pointing out their limitations, especially the physical limits of doing a Marine’s job.25 This kind of article encouraged male Marines to accept their female colleagues’ presence by indicating their competence in completing their assignments while implying they lacked essential martial qualities that might allow them to fully replace men. Men’s position as “real” Marines was still safe from female incursion, even as their labor became central to the Corps’ ability to function. The presence of women in the Corps complicated the performance of masculinity because women took on occupations and official uniforms previously seen as male-centered, and Leatherneck assisted readers in making a space for women in the Marines by explaining women’s presence and purpose and by showing male Marines that these women would not threaten the reputation of their beloved institution.

S. B. Scidmore’s article “Powder Puff Marine” in a 1945 issue of Leatherneck further explained Women Marines’ importance to male Marines. This story explored the internal conflict some male Marines felt at the addition of women to the Corps. The story’s main character, a male Marine named Sergeant O’Hara, was assigned to deliver a message to a Woman Marine. O’Hara did not believe that women deserved to wear the uniform because they did not serve in combat roles. However, as O’Hara arrived at the Woman Marine’s office, she asked him to get a Coke with her and talk. In spite of his misgivings about women in the Corps, O’Hara agreed. During their conversation, O’Hara learned that this particular Woman Marine took the office position his friend Brady used to hold. Her service allowed Brady to complete combat duty, during which Brady saved O’Hara’s life. This information changed how O’Hara perceived Women Marines. They may not serve on the front lines, but they did important work that enabled male Marines to fight and to potentially protect each other.26 This anecdote illustrated how Women Marines might make a positive impact on the Corps and on the lives of individual male Marines, while clearly showing the boundaries of these women’s work: she was in the office while Brady was in combat. This Woman Marine’s uniformed body allowed Brady to do the more masculine work of combat and to save O’Hara’s life. O’Hara’s objections to women’s bodies wearing Marine Corps uniforms were overcome by the revelation of the necessity of women’s labor. While such stories were clearly intended to try to help male Marines feel better about the presence of women, they did not end concerns about women’s place in the Corps and their potential impact on Marines’ reputations.

Marine Corps Correspondence

Official communications also articulated the Corps’ position on Women Marines. In Letter of Instruction No. 489 from 1943, Commandant Thomas Holcomb welcomed the Women’s Reserve to the Corps and addressed issues of custom and regulation. The letter considered the significance of public opinion and the presentation of the Women Marines’ image to the Corps and to the future of their service, saying,

The wide-spread public interest reflected in Congress and through the press strongly indicates that the future existence of this branch of the Marine Corps depends largely upon the reaction of the American public to the demeanor of its members. It is felt that in this respect the Women’s Reserve will continue to hold the position of high esteem which it deserves only if the utmost care is exercised in deportment, manner, and appearance of its individual members.27

Holcomb’s emphasis on “deportment, manner, and appearance” of Women Marines underscored the significance of these women’s bodies and the behavior of those bodies to protecting the Corps’ image and reputation. Holcomb also pointed out the need for Women Marines to show the civilian public that they could serve in the military while remaining feminine and respectable. The letter told women about their uniforms, how to respond to and interact with male personnel, rules on smoking and drinking, and counsel on the application of cosmetics while in uniform. For example, the letter instructed women that “lipstick, if worn, shall be the same color as cap cord, winter service, and shall be inconspicuous. Colored nail polish, if worn, shall harmonize with color of winter service cap cord and lipstick. Mascara shall not be worn.”28 Women Marines’ behavior and appearance reflected on the Corps’ image, and officials quickly moved to provide women advice on how to aid the positive presentation of Marines, contributing to an elite military image in keeping with the traditions of the Corps while simultaneously presenting a feminine version of that ideal, one that frequently centered on the performance of femininity and the presentation of bodies.29

Likewise, a memorandum from Director Streeter further instructed Women Marine officers on upholding the Corps’ image by controlling the bodies and behavior of their fellow female Marines both in and out of uniform. Streeter stated, “If an officer’s own sense of propriety is not an adequate guide, it becomes the duty of whatever senior Marine Corps Women’s Reserve (MCWR) officer is present to admonish her . . . it would apply in such cases as failure to comply with uniform regulations by the use of exaggerated makeup, too long hair, too short skirts; noisy or unladylike behavior; unconventional actions, such as men and women officers visiting in each other’s bedrooms.”30 Streeter encouraged senior officers to police the behavior and bodies of junior officers and enlisted women in as tactful a manner as possible to protect the Women’s Reserve’s reputation and image.31

As previously mentioned, many concerns about image and reputation, and how bodies represented that image and reputation, fed into the American public’s worries that wartime conditions led to lower moral standards for both men and women and to an increase in the spread of sexually transmitted diseases. Women’s movement into new public places and the presentation of their bodies in novel ways, such as wearing military uniforms, led to further worries about the ways that women might use their bodies, both with patriotic purpose and for pleasure. Officials blamed both professional prostitutes and reckless young women for an increase in venereal disease, placing little responsibility on the men involved. While civil and military authorities took some responsibility for preventing prostitution, they exerted little control over other young women. Rather, many people believed that the decrease in parental supervision due to wartime conditions contributed to the misbehavior of these women.32 Many sources blamed women for men’s contraction of venereal disease and focused on the regulation of both military and civilian women’s bodies to decrease infection. Marilyn Hegarty argues that this tendency largely stemmed from contemporary understandings of masculinity and men’s sexual needs, and Leisa Meyer points to the ways that this understanding of masculinity extended to members of the Women’s Army Corps (WAC), leading to a preoccupation with their sexual behavior and morality.33 Given the similarities in personal background, training, and the broader nature of military environments, it seems likely that Meyer’s observations about WACs largely translated to Women Marines as well. Young women without parental supervision working in a highly masculine environment far from their homes were looked at with suspicion and their respectability was frequently questioned.

To address concerns about women’s supposed promiscuity, the Corps emphasized the significance of the issue in training camps and continuing education. During this education, Women Marines attended lectures reminding them of the moral necessity of refraining from extramarital sexual activity. For example, in one lecture, Chaplain H. W. E. Swanson stated,

Venereal disease is a military crime, and a serious one. But do not think that the government, and the Marine Corps is encouraging you to indulge in promiscuity, providing you avoid disease. In setting up prophylactic services, your Marine Corps is only doing its duty to provide for those who do the wrong thing—even as our government must provide for wrongdoers.34

Swanson clarified that government-provided prophylactic stations were not intended as approval or acceptance of promiscuous behavior, especially from female Marines. Rather, they were a necessary service provided to save reckless young men and women from their own poor decisionmaking. The expectation was that Marines would safeguard their own bodies. After further emphasizing the need to avoid all sexual activity, even if encouraged by male Marines, Chaplain Swanson went on to say, “You are really the picked and choice women of the nation.”35 The implication was that if these women wanted to remain part of that elite group included in the Marine Corps, they must continue to protect their bodies from venereal disease and bad reputations that might result from promiscuity. Swanson’s warning about guarding themselves from persuasion by male Marines also emphasized the difference in expectations for these women’s behavior with regard to their bodies. While the Corps did not encourage male Marines to engage in extramarital sexual activity, it was anticipated that they would fall victim to such temptations on occasion. Without the excuse of masculine needs, women received far less leniency if they were caught demonstrating such behavior.

In a similar talk, Chaplain Roland B. Gittelsohn asked Women Marines to consider three questions before engaging in sexual activity: “What reputation are you helping to give the Women Marines?” “What will the nation say of you when the war is over?”, and “What are you going to think of yourself when the war is over?” He pointed out the prevalent rumors about military women’s promiscuity and lack of morality and told women that while he was quite certain these rumors were untrue, the “eyes of the country are on you now.”36 Women Marines were charged with protecting the Corps’ image through their use of their own bodies, as well as guarding their personal reputations. Gittelsohn recommended that these women aim to have people remember their service instead as, “You brought your feminine youth, charm, brightness, laughter, warmth, color to drab masculine camps And [sic] at the same time, lifted both the morals and morale of men.”37 Swanson and Gittelsohn made it clear that promiscuous female bodies did not fit with the Corps’ idea of who it was.

In spite of this training and rhetoric, women who became ill with sexually transmitted diseases usually received medical treatment and returned to duty. However, a memorandum by Director Streeter indicated that word of infection frequently spread to other women in a unit and resulted in resentment and poor treatment by their peers. Streeter’s memorandum added that transferring the previously infected woman often resolved the problem. The memorandum reiterated Swanson’s comments that relatively liberal policies toward venereal disease infection did not advocate for promiscuous behavior. In fact, Streeter said that while a single instance might be forgiven by the Corps as a mistake, a habit of such sexual behavior could be grounds for “unsuitable” discharge.38 The decisions these women made about their bodies and sexual behavior could be seen as a reflection of the Corps’ values and, as such, promiscuous women were removed from service.

Streeter also acknowledged that homosexual behavior and fears about such behavior affected the Marine Corps Women’s Reserve, just as it did other women’s Service branches.39 While Streeter presented homosexual behavior as unacceptable, she also warned against “witch-hunting” and potentially negatively affecting the lives, careers, and reputations of innocent women. Streeter said that close relationships between women should be expected in the Corps, but those that became too intimate should initially be separated, transferring one of the women to a different command. If headquarters received multiple reports about a particular woman, she could be discharged for “unsuitable” behavior. This memorandum advised seeking a medical opinion regarding individuals accused of homosexual behavior, because the Corps typically perceived homosexual behavior as a medical rather than a disciplinary issue during this time.40

This concern with women’s sexual behavior extended to worries about pregnancy as well. While Women Marines were permitted to marry while in the Service, pregnancy resulted in immediate discharge. The Corps believed that the act of having children indicated a woman’s readiness to leave military service to focus on home and family. Serving as a Marine and being a mother were perceived as mutually exclusive during this time. The Corps also made no distinction between pregnancies resulting from premarital relationships and those from marriage in order to encourage women to report their status, and they gave all pregnant women an honorable discharge unless there were extenuating circumstances beyond their pregnant status.41 The government also reserved the right to discharge women as “unsuitable” if they sought out a medically induced abortion. Miscarriages and cases of stillborn children occasionally meant women could remain in the Corps if recommended by their commanding officer and found psychologically fit, but officials perceived abortion as indicating psychological disturbance disqualifying women from service. Intentionally ending a pregnancy was perceived as counter to feminine norms encouraged within the Corps as well as broader American society. The choice these women made about their bodies made them unfit for service in the opinion of the Marine Corps, even as pregnancy also disqualified women from service. In the cases of pregnancy, venereal disease, promiscuity, and homosexuality, the Marine Corps heavily regulated women’s bodies and sexual behavior to protect their ideal image and reputation.

Conclusions

Expectations regarding Women Marines’ feminine appearance and behavior fit with patterns seen for other military women in World War II, as seen in the work of Meyer and others, even as the Corps’ rhetoric presented these women as representing the elite nature of the Corps, as explained in Cameron, O’Connell, Venable, and others. Belkin’s argument regarding the interconnectedness of masculinity and femininity within the military and Jarvis’s emphasis on the significance of bodies are also borne out through the importance of images of bodies to the representation of the Corps. Evidence provided here shows that bodies, both their appearance and their behavior, were integral to the Marine Corps’ representation of Women Marines in World War II as well as to the maintenance of the Corps’ reputation and image. Americans like Miriam Galpin consumed these images and representations of Marines and chose to fashion their own bodies and images in ways that allowed them to fit into the Corps’ ideals. These individuals observed the Marine Corps’ reputation for eliteness and patriotic service and decided to enroll in this particular military branch on the basis of those ideas. While common gender norms remained central to Americans’ understanding of how men and women’s service functioned within the Marine Corps, similarity in expectations of Marines’ appearance and behavior regardless of gender provided an underlying continuity between these images and representations, while allowing for variability to conform with most civilian concepts of gender roles. These images allowed the Marine Corps to continue controlling the Corps’ hypermasculine narrative and reputation even as it incorporated large numbers of women.

•1775•

Endnotes

- “Beauty Isn’t Prerequisite for Girl Marines, Chief Says,” Wisconsin State Journal, 22 September 1943.

- Miriam Galpin to Herbert and Better Colker, 25 and 31 May and 9 June 1943, letters, “From Miriam Galpin to Herbert and Betty (Betty’s Sister),” Colker Collection—Herbert and Betty Colker 11.0006, Institute for World War II and the Human Experience, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, hereafter Colker Collection; Miriam Galpin to Herbert Colker, 28 August 1943, letter, “From Miriam Galpin to Herbert 1943,” Colker Collection; Miriam Galpin to Herbert Colker, 15 September 1943, letter, “From Miriam Galpin to Herbert 1943,” Colker Collection; Miriam Galpin to Herbert Colker, 27 October 1943, letter, “From Miriam Galpin to Herbert 1943,” Colker Collection; Miriam Galpin to Herbert Colker, 21 July 1945, letter, “From Miriam Galpin to Herbert (Betty’s Sister),” Colker Collection; and Miriam Galpin to Galpin family, 5 September 1943, letter, “From Miriam Galpin to Galpin Family 1943,” Colker Collection.

- The author is presently working on a book-length manuscript that will consider the intersection and comparison of images of male and female Marines and expands the chronology of this project to include World War I and the Korean War.

- Aaron B. O’Connell, Underdogs: The Making of the Modern Marine Corps (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012); Cameron M. Craig, American Samurai: Myth, Imagination, and the Conduct of Battle in the First Marine Division, 1941–1951 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994); Heather Venable, How the Few Became the Proud: Crafting the Marine Corps Mystique, 1874–1918 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2019); Mark Folse, “The Cleanest and Strongest of Our Young Manhood: Marines, Belleau Wood, and the Test of American Manliness,” Marine Corps History 4, no. 1 (Summer 2018): 6–22; and Zayna Bizri, “Marine Corps Recruiting During World War II: From Making Men to Making Marines, Marine Corps History 1, no. 1 (Summer 2015): 23–36.

- Julietta B. Kahn, “A Challenge to the Apparel Industry: Textile Experts Lack Sufficient Knowledge and Training, Says Quartermaster Office,” Women’s Wear Daily, 25 May 1944, 29.

- The author is currently working on the previously mentioned book, delving more deeply into the similarities and differences in the treatment of men and women Marines’ images.

- Domestic Operations Branch and Bureau of Special Services, Office of War Information, Office for Emergency Management, U.S. Marine Corps, “Ready. Join U.S. Marines,” poster, undated, 1941–45, Series: World War II Posters, 1942–45, Record Group (RG) 44, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), College Park, MD.

- D. L. S. Brewster, Untitled Venereal Disease Statistics for Camp Lejeune, 18 January 1942, memo; Julian C. Smith to Commandant U.S. Marine Corps, “Resolution of Interdepartmental Committee on Venereal Disease, Meeting November 17, 1942,” 24 January 1943, memo; William Bryden to James L. Underhill, 4 June 1943, letter; William Bryden to John Sams, 5 June 1943, letter; and Henry L. Larsen to William Bryden, 18 June 1943, letter, all box 797 Office of the Commandant, General Commandant, January 1939–June 1950, 1700-10 Acts-Care-Methods, RG 127, Office of the Commandant of the United States Marine Corps, NARA. A number of authors address public concerns about the sexual behavior of military servicemembers, including Allan Bérubé, Coming Out Under Fire: The History of Gay Men and Women in World War II (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010); Marilyn E. Hegarty, Victory Girls, Khaki-Wackies, and Patriotutes: The Regulation of Female Sexuality during World War II (New York: New York University Press, 2008); and Melissa A. McEuen, Making War, Making Women: Femininity and Duty on the American Home Front, 1941–1945 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011).

- Henry I. Shaw Jr. and Ralph W. Donnelly, Blacks in the Marine Corps (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, reprint 2002), 56. Also from Shaw and Donnelly, while African American men served during World War II, the small number of Women Marines prevented African American women from joining until Women Marines became permanent within the Corps with the passage of the 1948 Women’s Armed Services Integration Act due to requirements for segregation.

- Aaron Belkin, Bring Me Men: Military Masculinity and the Benign Façade of American Empire, 1898–2001 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012).

- Also see, R. W. Connell, Masculinities, 2d ed. (Berkley: University of California Press, 2005); and E. Anthony Rotundo, American Manhood: Transformations in Masculinity from the Revolution to the Modern Era (New York: Basic Books, 1993). Additional works address this shift in gender relations and the resulting tension between military men and women throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries: Francine D’Amico and Laurie Weinstein, editors, Gender Camouflage: Women and the U.S. Military (New York: New York University Press, 1999); Melissa Ming Foynes, Jillian C. Shipherd, and Ellen F. Harrington, “Race and Gender Discrimination in the Marines,” Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 19, no. 1 (2013): 111–19, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030567; Melissa S. Herbert, Camouflage Isn’t Only for Combat: Gender, Sexuality, and Women in the Military (New York: New York University Press, 1998); Heather J. Höpfl, “Becoming a (Virile) Member: Women and the Military Body,” Body and Society 9, no. 4 (2003): 13–30, https:// doi.org/10.1177/1357034X0394003; Leisa D. Meyer, Creating GI Jane: Sexuality and Power in the Women’s Army Corps during World War II (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996); Sara L. Zeigler and Gregory G. Gunderson, Moving Beyond GI Jane: Women and the U.S. Military (New York: University Press of America, 2005); Bérubé, Coming Out Under Fire; Edwin Howard Simmons, The United States Marines: A History, 4th ed. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2003); J. Robert Moskin, The U.S. Marine Corps Story, 3d rev. ed. (Boston: Little, Brown, 1992); Col Mary V. Stremlow, A History of the Women Marines, 1946–1977 (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1986); Col Mary V. Stremlow, Free a Marine to Fight: Women Marines in World War II (Washington, DC: Marine Corps Historical Center, 1994); and Pat Meid, Marine Corps Women’s Reserve in World War II (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1968). Concepts of gender used in this article were influenced by the following: Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York: Routledge, 1990); Connell, Masculinities; and Joan W. Scott, “Gender: A Useful Category of Analysis,” American Historical Review 91, no. 5 (1986): 1053–75. See also Joanne Meyerowitz, ed., Not June Cleaver: Women and Gender in Postwar America, 1945–1960 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1994).

- Christina S. Jarvis, The Male Body at War: American Masculinity during World War II (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2010).

- Butler, Gender Trouble; Scott, “Gender: A Useful Category of Analysis”; Jarvis, The Male Body at War; O’Connell, Underdogs; Craig, American Samurai; and Venable, How the Few Became the Proud. The following also discuss the significance of the media during World War II: Paul Alkebulan, The African American Press in World War II: Toward Victory at Home and Abroad (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2014); Susan Ohmer, “Female Spectatorship and Women’s Magazines: Hollywood, Good Housekeeping, and World War II,” Velvet Light Trap, no. 25 (1990): 53–68; John Bush Jones, All-Out for Victory!: Magazine Advertising and the World War II Home Front (Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press, 2009); Maureen Honey, “Recruiting Women for War Work: OWI and the Magazine Industry During World War II,” Journal of American Culture 3, no. 1 (1980): 47–52, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-734X.1980.0301_47.x; James Lileks, “The Ad Man Goes to War,” American Spectator 47, no. 5 (2014): 26–29; David Welch, World War II Propaganda: Analyzing the Art of Persuasion during Wartime (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2017); Colin M. Colbourn, “Esprit De Marine Corps: The Making of the Modern Marine Corps through Public Relations, 1898–1945” (PhD diss., University of Southern Mississippi, 2018); Mark R. Folse, “The Globe and Anchor Men: U.S. Marines, Manhood, and American Culture, 1914–1924” (PhD diss., University of Alabama, 2018); Mark Folse, “Marine Corps Identity from the Historical Perspective,” War on the Rocks, 13 May 2019; and Gary L. Rutledge, “The Rhetoric of United States Marine Corps Enlisted Recruitment: A Historical Study and Analysis of the Persuasive Approach Utilized” (PhD diss., University of Kansas, 1974).

- Monica Brasted, Magazine Advertising in Life during World War II: Patriotism through Service, Thrift, and Utility (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2018); Robert Griffith, “The Selling of America: The Advertising Council and American Politics, 1942–1960,” Business History Review 57, no. 3 (Autumn 1983): 388–412, https://doi.org/10.2307/3114050; Venable, How the Few Became the Proud; Colbourn, “Esprit De Marine Corps”; Folse, “The Globe and Anchor Men”; and Rutledge, “The Rhetoric of United States Marine Corps Enlisted Recruitment.”

- As mentioned, the author is presently working on a book further exploring this issue and expanding to look in more detail at the interconnections between male and female Marines’ images and their link to the Corps’ overall reputation.

- “Montezuma Red” Elizabeth Arden advertisement, Vogue 103, no. 8 (15 April 1944): 115.

- “Montezuma Red” Elizabeth Arden brochure, undated, Women Marines-Publications (1 of 3), Archives, Historical Resources Branch, Marine Corps History Division (MCHD), Quantico, VA.

- “Montezuma Red” Elizabeth Arden brochure. Page Dougherty Delano argues that a more complex intersection of norms and women’s independence occurred in cosmetics during World War II, which presents interesting future avenues of research related to Women Marines. Page Dougherty Delano, “Making Up for War: Sexuality and Citizenship in Wartime Culture,” Feminist Studies 26, no. 1 (Spring 2000): 33–68, https:// doi.org/10.2307/3178592.

- “First in Fashion” Camel advertisement, Vogue 102, no. 22 (1 November 1943). Members of the Women Airforce Service Pilots were not considered official members of the military until 1977. “Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP),” Women in the Army, U.S. Army. For more on WASPs, see Marianne Verges, On Silver Wings: The Women Airforce Service Pilots of World War II (New York: Ballantine Books, 1991); Molly Merryman, Clipped Wings: The Rise and Fall of the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs) of World War II (New York: New York University Press, 1991); Katherine Sharp Landdeck, The Women with the Silver Wings: The Inspiring True Story of the Women Airforce Service Pilots of World War II (New York: Crown, 2021); and others.

- “Join the Marines and See-Romance; Girls’ Director Here, Gives O.K.,” Evening Bulletin (Philadelphia, PA), 9 June 1943. Instructions from Headquarters Marine Corps provide a more restrictive view of relations between male and female Marines. For example, Letter of Instruction No. 702 does not forbid all relationships between Marines, but the letter emphasizes the necessity of navigating such relationships carefully to avoid compromising military hierarchy and order. Alexander A. Vandegrift, “Letter of Instruction No. 702,” Women Marines-Wars (1 of 2), MCHD. For information on enlistment requirements for the Marine Corps Women’s Reserve, see Meid, Marine Corps Women’s Reserve in World War II.

- “Beauty Isn’t Prerequisite for Girl Marines, Chief Says.”

- Arthur P. Brill Jr., “History: The Marine Corps Association: 100 Years of Service,” Marine Corps Association, accessed 13 November 2020. Robert Nelson speaks to the significance of Service newspapers and newsletters in the British, French, and German context, but it seems likely that the importance of these publications extended also to American servicemembers and their publications. Robert L. Nelson, “Soldier Newspapers: A Useful Source in the Social and Cultural History of the First World War and Beyond,” War in History 17, no. 2 (April 2010): 167– 91, https://doi.org/10.1177/0968344509357127.

- “Shinola Shoe Polish” advertisement, Leatherneck (January 1941): 42.

- “The Leatherneck Visits Depot of Supplies, Department of the Pacific, San Francisco,” Leatherneck (January 1944): 76.

- “The Leatherneck Visits Depot of Supplies,” 76–77.

- S. B. Scidmore, “Powder Puff Marine,” Leatherneck (January 1945): 33.

- Thomas Holcomb, Letter of Instruction No. 489, 16 July 1943, 2275-45 DB-311-rwg, “Blanchard, Florence L. PC#714, Access #741806, WWII, Photos/Humour,” Folder/1A41, Archives, MCHD, 1.

- Holcomb, “Letter of Instruction No. 489,” 2.

- Holcomb, “Letter of Instruction No. 489.

- Ruth Cheney Streeter, memo “Marine Corps Women’s Reserve, Matters Effecting,” 19 May 1944, “Women Marines-Wars (1 of 2),” MCHD, 10.

- Streeter, memo “Marine Corps Women’s Reserve, Matters Effecting.”

- “Venereal Disease,” New York Times, 27 January 1945, 10; and Hegarty, Victory Girls, Khaki-Wackies, and Patriotutes. Hegarty points out that many of these women considered themselves to be in relationships with the men with whom they engaged in sexual intercourse. They generally did not see their behavior as prostitution. An example illustrating this issue can be found in the following: “ ‘Red Light’ Areas Declared Ending: Taft Committee Reports on Year of Nation-Wide War on Venereal Disease, Fights the ‘Promiscuous’, Opening ‘Second Front’ Against StreetWalkers and Others as Possible ‘Mad Dogs’,” New York Times, 27 December 1942, 27. Other sources on prostitution, venereal disease, and the American military include the following: Scott Wasserman Stern, “The Long American Plan: The U.S. Government’s Campaign Against Venereal Disease and Its Carriers,” Harvard Journal of Law & Gender 38 (Summer 2015): 373–436; Robert Kramm, Sanitized Sex: Regulating Prostitution, Venereal Disease, and Intimacy in Occupied Japan, 1945–1952 (Oakland: University of California Press, 2017); Elizabeth Alice Clement, Love For Sale: Courting, Treating, and Prostitution in New York City, 1900–1945 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006); Mary Louise Roberts, What Soldiers Do: Sex and the American GI in World War II (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013); Mary Louise Roberts, “The Price of Discretion: Prostitution, Venereal Disease, and the American Military in France, 1944–1946,” American Historical Review 115, no. 4 (2010): 1002–30, https://doi.org/10.1086/ahr.115.4.1002; John Parascandola, “Presidential Address: Quarantining Women: Venereal Disease Rapid Treatment Centers in World War II America,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 83, no. 3 (2009): 431–59, https://doi.org/10.1353/bhm.0.0267; William B. Anderson, “The Great War Against Venereal Disease: How the Government Used PR to Wage an Anti-Vice Campaign,” Public Relations Review 43, no. 3 (2017): 507–16, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2017.03.003; Meghan K. Winchell, Good Girls, Good Food, Good Fun: The Story of USO Hostesses during World War II (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008); Claire Strom, “Controlling Venereal Disease in Orlando During World War II,” Florida Historical Quarterly 91, no. 1 (2012): 86–117; Melissa A. McEuen, Making War, Making Women: Femininity and Duty on the American Home Front, 1941–1945 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011); and Meyer, Creating GI Jane. See also “Board Seeks Ban on ‘Loose’ Tavern: Army-Navy Group Acts to Save Service Men Here from Dangers of Disease, Infection Rise Revealed, Official ‘Out-of-Bounds’ Order for Bars Where ‘Dates’ Are Made Is Recommended,” New York Times, 4 November 1944, 17.

- Hegarty, Victory Girls, Khaki-Wackies, and Patriotutes; and Meyer, Creating GI Jane.

- 4 H. W. E. Swanson, “Brief Outline of Talk on Moral Aspects of Venereal Disease Given to Women’s Reserve,” 1943, box 797, Office of the Commandant, General Commandant, January 1939–June 1950, 1700-10 ActsCare-Methods, RG 127, NARA.

- Swanson, “Brief Outline of Talk on Moral Aspects of Venereal Disease Given to Women’s Reserve.”

- Roland B. Gittelsohn, “Introduction,” 1943, box 797, Office of the Commandant, General Commandant, January 1939–June 1950, 1700-10 Acts-Care-Methods, RG 127, NARA. Leisa Meyer also discusses such assumptions of military women’s promiscuity in her book, Creating GI Jane.

- Gittelsohn, “Introduction.”

- Streeter, memo “Marine Corps Women’s Reserve, Matters Effecting.” This memo provided additional information building on earlier instructions from Headquarters Marine Corps from the previous year. Thomas Holcomb, Letter of Instruction No. 499, Women Marines-Wars (1 of 2), Archives, MCHD.

- The following historians examine homosexuality in the military, though not specifically the Marine Corps: Bérubé, Coming Out Under Fire; Hegarty, Victory Girls, Khaki-Wackies, and Patriotutes; Herbert, Camouflage Isn’t Only for Combat; and Meyer, Creating GI Jane.

- Streeter, memo “Marine Corps Women’s Reserve, Matters Effecting”; D’Ann Campbell, Women at War with America: Private Lives in a Patriotic Era (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984); and D’Ann Campbell, “Women in Combat: The World War II Experience in the United States, Great Britain, Germany, and the Soviet Union,” Journal of Military History 57 (April 1993): 301–23.

- Alexander A. Vandegrift, “Letter of Instruction No. 858,” 5 October 1944, Women Marines-Wars (1 of 2), MCHD; and Streeter, memo “Marine Corps Women’s Reserve, Matters Effecting.”