PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

Abstract: Was the Marine Corps’ success at Iwo Jima a matter of leadership, bravado, or fundamental training? This article examines the efficacy of boot camp, replacement training, and unit training as it relates to the success of the U.S. Marines on Iwo Jima. During World War II, the exploits of the Marines on Iwo Jima have been commended, but the reality of wartime exigencies inevitably placed a strain on the quality of men slated for the Service. However, the Marine Corps’ emphasis on the fundamentals during boot camp proved the necessary ingredient for victory. Beyond leadership or lore, this article asserts that Marine Corps boot camp provided an elemental gateway to success on Iwo Jima.

Keywords: Marine Corps, boot camp, World War II, Pacific campaign, recruit training, replacement training, Iwo Jima, 3d Marine Division, 4th Marine Division, 5th Marine Division, V Amphibious Corps, Parris Island

Introduction

U.S. Marine heroics on Iwo Jima have been commended time and again in both academic and popular histories.1 This is not surprising since more than one-quarter of all the Marine Corps’ World War II medals of honor were earned during action on that tiny, sulfurous island. Marines faced a ferocious Japanese underground defensive network that was never seen before or after on such terrain, resulting in more than 2,400 Marines killed or wounded the first day of the assault. The exploits on 19 February 1945 solidified the Marine Corps’ legacy and eulogized the operations on Iwo Jima as iconic.2 The reported exemplary combat performance and ultimate capture of Iwo Jima led to the assumption that the Marines who attacked the island were expertly trained.3 Due to the draft, the high replacement rate, and the need for manpower in multiple theaters of war, a shortage of time and quality instructors alongside substandard methods underscore where these assumptions begin to falter. It is unclear precisely what training these Marines received prior to what Jeter A. Isely and Philip A. Crowl describe as “throwing human flesh against reinforced concrete.”4 Missing from the discussion is how the Corps was able to mass-produce men, using a limited wartime schedule to function under heavy fire and enormous casualties. An examination of the Marine Corps’ basic training, reserve troop training, and unit training will show that the latter two were deficient. Operation reports such as ones from the 3d Marine Division Reinforced: Iwo Jima Action Report and the Task Force 56 G-3’s planning report for Iwo Jima state that the troops were not consistently in an advanced state of training, and the training application was inconsistent and immeasurable.5 Boot camp remained the only steadfast, principal training acquired by the troops headed to Iwo Jima.

The American public was quickly losing morale when it came to the duration of World War II. The war affected nearly every individual in one way or another, and heavy losses took a toll on the public’s opinions of the necessity versus cost involved in further Pacific campaigns.6 As the fighting began on Iwo Jima, the Marines raised a symbol of hope in the form of an American flag from the top of Mount Suribachi. This became a source of encouragement for troops fighting in the Pacific and for the American people and their faith in the U.S. Marine Corps. Iwo Jima was part of the original Japanese prefecture, and the eventual capture would be a great victory for not only American determination but also a huge psychological blow to the Japanese.7 Although the Marines’ heroics were immediately memorialized by Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz in March 1945 when he said, “Among the Americans who served on Iwo Island, uncommon valor was a common virtue,” limited attempts have been made to dissect how “uncommon valor” became such a “common virtue” among the Corps.8 Few detailed reports on the methodology or strategies for creating this trait exist, mostly schedules, goals, and end results. Scholarship focuses on battle details of Operation Detachment, the code name given to the battle for the Japanese-held island of Iwo Jima, and the numerous acts of patriotism and loyalty among the Marines, but lacks in-depth analysis of what made the Marines behave this way.9 Was it the basic indoctrination received in boot camp, or can more credit be given to the training received during pre-embarkation exercises? How did the Marine Corps train the men who volunteered or were drafted to possess such uncommon valor, and did the Marine Corps’ training differ from other Service branches? This study will grapple with those questions and analyze enlisted Marine basic training, Marine combat performance, and individual heroics providing a comparison to establish the source of the Corps’ success. This article argues that the core values instilled during basic training were enough to overcome the challenges encountered at Iwo Jima. Consequently, it was through their initiative in small-unit combat that the battle was won.

Historiography

Generally, the major themes encompassing the literature on Iwo Jima fall into three basic categories: training, planning, and implementation; battle narrative; and individual acts of valor. Most of the accounts comment on leadership, the efficacy or fault involving the use of coordinated arms, and amphibious doctrine and its contribution to the victory at Iwo Jima.

In Marine Corps Ground Training in World War II, Kenneth W. Condit, Gerald Diamond, and Edwin T. Turnbladh argue that the early success of the Marines was due to recruit training conducted during peacetime. Condit, Diamond, and Turnbladh, who wrote or edited multiple works for the Historical Branch of the Marine Corps, focus more on the objective subjects of the training that aided in the Corps’ successes during World War II.10 Their examination is based primarily on the records of Headquarters Marine Corps and the Marine Corps Schools. Each assessment of the periods and types of training proposes recommendations and conclusions based on the after action reports provided by the Marine Corps as well as the authors’ analysis of these recommendations and conclusions and the benefit of retrospection. While very detailed regarding time frames and subject areas of training, these authors fail to break down the methodology used by drill instructors or give specifics on how recruits are trained in the subject matter, performance corrections, or the instruction modes that established the motto First to Fight and nicknames such as leathernecks and devil dogs, that remain an integral part of the Marines’ bearing.11

In Western Pacific Operations, authors George W. Garand and Truman R. Strobridge’s primary focus is on Marine Corps leadership and how they translated their experience in World War I to the planning for Iwo Jima. They formulate their argument beginning with the expertise of the leaders and planners of the battle. Many of these leaders served in World War I and had extensive experience with amphibious doctrine. Garand and Strobridge argue that victory on Iwo Jima was achieved through the leadership’s careful planning and preparation, the coordination of supporting arms, and an advanced state of training. Garand and Strobridge state: “That the island could be taken at all in view of the strength of its defenses and the casualties incurred by the attacking Marines is proof of the latters’ courage, highly advanced state of training, and the soundness of amphibious doctrine that had become an integral part of Marine Corps tactics.”12 This argument is problematic due to the shortcomings experienced in the training in addition to the operation reports stating that the troops were not consistently advanced in training as purported. It also does not adequately address the heavy casualties incurred by officers and command leaders throughout operations in the Pacific or how this affected the small units in the absence of their leadership.13 The majority of the sources cited in Western Pacific Operations are letters between commanders and official Marine Corps reports, so it is noteworthy that the failures experienced in training are not thoroughly discussed. There is a possibility that the discrepancies between the reports and actual troop readiness were the authors’ attempt to disguise the limitations experienced by leadership or the force, either to avoid appearing inefficient or in acknowledgement of wartime limitations. Conversely, the 3d Marine Division Reinforced: Iwo Jima Action Report states that the status of combat training of the 28th and 34th Replacement Drafts were found to be “badly deficient,” and only simple exercises in ship-to-shore movement were conducted early in the training schedule.14 It was also reported that two to four weeks of recruit training formed the full extent of their combat training.15

Isely and Crowl also evaluate the Marine Corps’ shortcomings when it comes to amphibious doctrine and implementation. They take a systematic approach to assessing the role of amphibious training and operations during the Second World War, providing one of the most comprehensive looks at the contribution of amphibious warfare that characterized the Marine Corps. Like many historians, they assert that “the capture of Iwo is the classical amphibious assault of recorded history.”16 Isely and Crowl in addition to Condit, Diamond, and Turnbladh place a great deal of emphasis on the significance of amphibious training conducted before Iwo Jima. Their discussions dedicate considerable portions to the analysis of landing tactics, amphibious vehicles, and coordinated support. These authors’ analyses summarize how amphibious doctrine paved the way for an effortless attack on any heavily fortified islands. According to the V Amphibious Corps Landing Force report on the Iwo Jima campaign, the battle replacements arrived late and there was insufficient time to train them in their shore duties or for use as replacements within the division. Many of the pre-embarkation rehearsals were also deficient.17 At times, amphibian tractors were missing or, because of crowded beach conditions during ship-to-shore rehearsals, battalions and companies were not landed.18 During the second week of January 1945, the 4th and 5th Marine Divisions conducted rehearsals off Maui and Kahoolawe Islands, Hawaii, but they lacked realism because coordinated naval and aerial joint fires support was still in the Philippine region. Rehearsals in the Mariana Islands were also impaired by weather that prevented any troops from landing.19 While amphibious doctrine paved the way, the rehearsals were insufficient, and a successful beach landing was only one element of the attack on Iwo Jima.

Another ineffective strategy the Marine Corps used, as noted by Isely and Crowl, was the employment of replacements in a one-for-one system. A report filed 31 March 1945, from the Headquarters Expeditionary Troops, Task Force 56, G-4 Report of Logistics Iwo Jima Operation, stated, “Prior to embarkation these troops were trained to be with the regular division shore parties and during initial phase of assault, were to function as service troops of the shore party upon completion of their mission with the shore party or when called for by the divisions, they were released as combat replacements for assault units.”20 Even if they were highly trained, it would have still proved challenging to function efficiently as a cohesive member of the force.21 According to Condit, Diamond, and Turnbladh, the training that began in December 1942 at the Replacement Training Depot established in Samoa was “far from satisfactory. Instructors were inexperienced and, in a few cases incompetent. Schedules had not been prepared in advance and had to be improvised day to day depending upon the availability of equipment.”22 Recruits being dispatched from the Replacement Training Depot received reports similar to the previous one made by the commanding general of the 2d Division on Tarawa Atoll. Reports stated that they lacked knowledge regarding simple first aid or field sanitization; few replacements, if any, had ever dug a foxhole; and there was little to no time devoted to combat firing.23 These outcomes were due to the high number of replacement troops needed and inconsistencies within the training. Some were unable to complete the full eight-week schedule and were sent to the division immediately following boot camp. The need for manpower created the dangerous situation of sending highly inexperienced troops into battle. Additionally, due to embarkation dates and inconsistent training schedules, the replacement troops headed to Iwo Jima would have only received a portion of the new training centered around bunker problems and not on the previous focus of jungle warfare.24

Enlisted Marine Basic Training

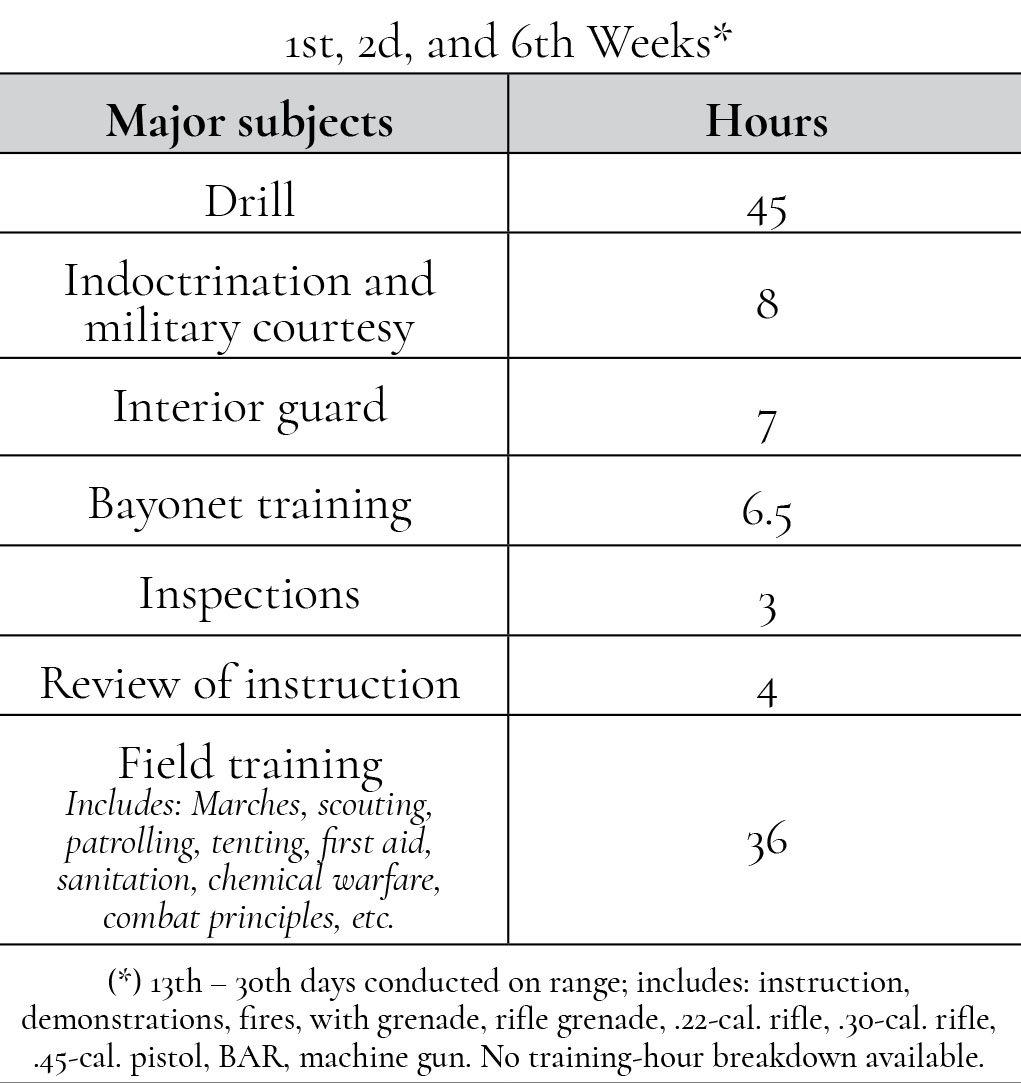

During peacetime, training for all recruits lasted for eight weeks at either Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island, South Carolina, or San Diego, California. The training comprised the fundamentals of military life, including “discipline, military courtesy, close order drill, and interior guard duty.”25 Intense physical conditioning and an emphasis on rifle mastery and accuracy on the range was elemental. The new recruit also received “elementary instruction in infantry combat subjects such as digging foxholes, using bayonets and grenades, chemical warfare, map reading, and basic squad combat principles.”26 Beginning on 1 June 1939, before President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s authorized increase, the eight-week schedule would be reduced to four weeks. This shortened training included two weeks of indoctrination and basic instruction in the ways of the Marine. Weapons training would occur during week three, and the fourth week would consist of further instruction or demonstration of other infantry weapons. Predictably, this four-week training schedule produced a measurable decrease in the caliber of the recruits graduating from boot camp. In January 1940, once the Marine Corps reached its strength of 25,000, the recruit training was increased to a six-week course (table 1). Once the United States joined the war effort, Marine Corps boot camp implementation would only continue to struggle under a restricted and erratic schedule. Even with this restricted schedule, the weeks spent in boot camp provided the necessary transition from civilian to military life. These recruits might not have been as efficient within the unit as those produced without wartime exigencies, but this instruction produced a basic Marine that was able to survive on the battlefield.27 The rest was on-the-job training.

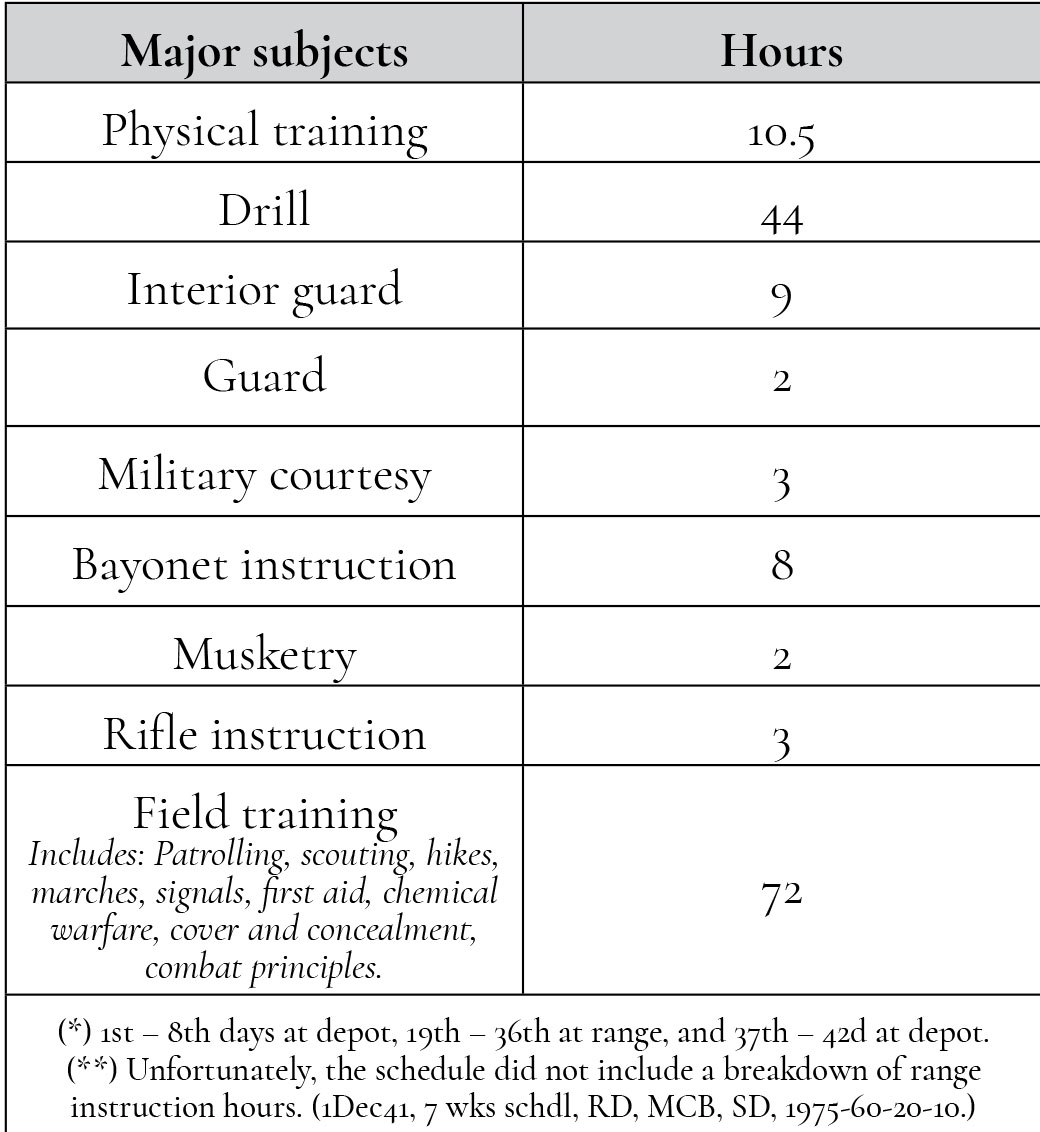

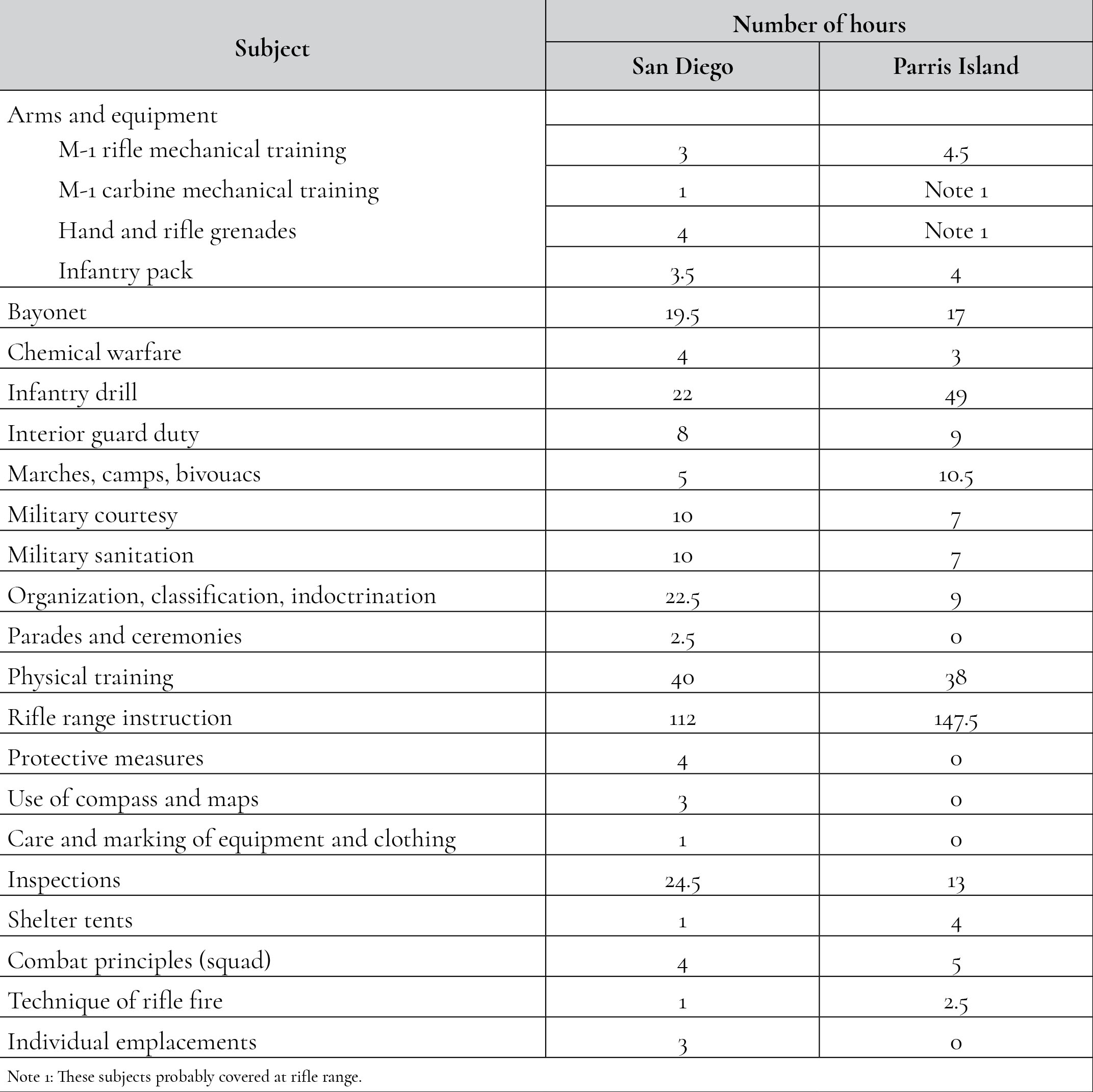

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Marine boot camp remained similar in content to boot camp conducted during the short-of-war period. An additional increase was authorized on 16 December 1941, bringing the Marine Corps strength up to 104,000 troops. This required the depots to train an average of 6,800 troops between December and February. On 1 January 1942, the recruit depots instituted a five-week training schedule in which three weeks were spent at the main station and the following two weeks were conducted at the rifle range. When enlistments began to decline, the schedule settled at a seven-week course on 1 March (table 2). When compared to peacetime recruit training, the most notable difference was an increased emphasis on combat readiness. Physical training was altered to include contact exercises such as “boxing, wrestling, judo, hand-to-hand fighting, and swimming.”28 In July 1944, leadership instituted additional reforms affording the Marine Corps a steady schedule of eight weeks of training for a total of 421 hours of instruction that included an additional 36 hours of weapons training (tables 3 and 4).29

Other Service branches’ training organizations, such as the Army’s, did not function similarly to the Marine Corps. The Army, from 1940 through 1945, inducted 8.1 million troops. To facilitate this expansion, the War Department designated a parent division to the new divisions being formed. These new divisions received 13 weeks of basic training as part of a 44-week training cycle. The 13-week basic training included 572 hours of instruction in subjects such as marches and bivouacs, individual tactical training, hand grenades, and bayonet training. Based on commanders’ reports and combat experience, there was a need to alter the 13-week basic training schedule by increasing it to 17 weeks in 1943. The most notable changes between the 13- and 17-week training schedules for the Army was the increase in weapons familiarization from 0 to 46 hours and physical training from 15 to 40 hours, respectively. There were disruptions throughout this training due to unique competition within the Army. They lost soldiers to the Army Air Force, Officer Candidate School, or Army Specialized Training Program.30

While the intention of this article is not to compare the branches of Service and the basic training/boot camp those Services provided during World War II, there are some similarities and differences between the Army’s basic training and the Marine Corps’ boot camp that can be discussed for clarity. However, an objective comparison cannot be made about whether one Service’s boot camp better equipped its recruits for battle over the other. The author believes it is actually the subjective qualities—the esprit, brotherhood, lore, and psychological aspects—of Marine Corps boot camp that led to Marines’ success on Iwo Jima, and therefore, a comparison should not be made in the context of this study.

The Army faced a set of unique obstacles during World War II. It not only had the largest influx of draftees and volunteers but also managed the National Guard integration and faced competition from specialties within the Army, such as the Army Air Force, Officer Candidate School, and the Army Specialized Training Program. The Army’s share of the total armed forces strength of 12,350,000 was 8,300,000. The Marine Corps did not face this large influx of individuals to train and did not experience significant competition for specifically qualified individuals within the Corps.31

Another difference can be found in the Marine Corps boot camp and Army reception centers. At the Army reception centers or induction stations, the newly enlisted soldier would receive a physical and psychiatric exam and then return for additional reception. The recruit reception centers were responsible for “the processing of recruits, that is, issuing uniforms, classifying them, and routing them to the replacement training centers which were maintained by the sperate branches of the Army. At the latter installations, basic military training was given; and, on completing it, the men were sent to specialist schools.”32 The training intended was 44 weeks. The first four weeks were designated for organization and receipt of personnel, followed by 13 weeks of “actual training.”33 The 13 weeks of basic training was broken down into one-month sections. The first month consisted of military courtesy, discipline, sanitation, first aid, map reading, individual tactics, and drill. The second month focused on specialty training, physical conditioning, bayonet courses, rifle ranges, and grenade courses. The last month was dedicated to weapons qualifications and individual and squad exercises.34 Because of the large number of new recruits slated for the Army, the Army required more training centers compared to the two (Parris Island and San Diego) needed for Marine Corps boot camp stations. Training was also divided into the replacement centers that were under the instruction of distinct branches of the Army, such as armored, infantry, and coast artillery.35 The Army reported that there were problems with the “replacements enroute to the theater of operations. Shipped as individuals, without unit organization or strong leadership, the[y] were moved from one agency to another—depot to port, transit to receiving depot, and then a myriad of intermediate agencies within the theater. Often spending months in transit, replacements became physically soft, discipline slackened, and skills eroded.”36

The Army’s basic training and Marine Corps’ boot camp did experience similar struggles during World War II. Both branches experienced a shortage in drill instructors and had to pull from often inexperienced instructors.37 Both branches received reports from overseas stating that the replacements “were found to have little or no training in advanced school of the soldier, guard duty, use and care of equipment, weapons,” etc.38 Soldiers and Marines alike reported they received less than the reported or assigned length of basic training/boot camp before they entered the theater of war.

The subjects of instruction and difficulties experienced during Army basic training and Marine Corps boot camp were not dissimilar. However, there is no way to objectively compare the Army basic training to Marine Corps boot camp during World War II due to wartime exigencies, the draft, and any errors in reporting. It is also impossible to confidently state that one branch prepared its recruits more successfully than the other. Missing from the cited sources and other primary documents regarding the Army’s basic training schedules and documents is the discussion of the psychology and methodology of how the desired result of esprit was established and maintained among Army recruits and the resulting efficacy on the battlefield. It is this psychology, methodology, lore, and establishment of esprit de corps examined during Marine Corps boot camp that the author believes is the key in the success of the Marines who fought on Iwo Jima.

The weekly boot camp schedules offer quantitative information regarding how Marines were trained, but there is little recorded evidence that contains the underlying philosophy employed to achieve the psychological shift from civilian to Marine. Recruits, volunteers, and conscripts ranged from a bellhop and a forest ranger to a college football player and a cowhand. The Marine Corps drill instructor’s job was to strip each civilian “of his identity as he learns how to drill, how to shoot, and above all, how to subordinate himself to the overall purpose of winning the war.”39 “Boot Camp,” published in Leatherneck in May 1942, provides an example of what the seven-week recruit training program generally entailed (tables 1 and 2). Mornings of the first week began with calisthenics under arms and close order drill without rifles. In the afternoons, Marines attended lectures, performed police work, and practiced more close order drill or boondocking. Boondocking is described as close order drill conducted in the sand above the recruit’s ankle.40 Corporal Gilbert P. Bailey explains “policing-up” in Boot: A Marine in the Making, as the drill instructor’s way of dealing with the psychological hierarchy present when the war brought in a diverse group of young recruits. Discipline and unit cohesion relied on the young recruits working together without undervaluing each other due to socioeconomic status. Bailey believed the shared hardships and mundane tasks were intended to bond the group so that “you feel like one of the boys not a damn bit too good to fight.”41 By analyzing the articles published during the prewar and early war years that relate the schedules, activities or subjects, treatment, and methodology or psychology used during Marine Corps training between 1942 and 1944, along with personal memoirs, the details (beyond the calculable hours and subjects) of how the recruits were being trained to work as a group and establish their pride of place in the Marine Corps are illuminated.42

Table 1. Six weeks training schedule: Recruit Depot, Parris Island, 1940

Source: Marine Corps Ground Training in World War II (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1956), 17

Table 2. Seven weeks training schedule: Recruit Depot, San Diego*

Source: Marine Corps Ground Training in World War II, 22

Table 3. Proposed eight week schedules (1944 reforms)

Source: Marine Corps Ground Training in World War II, 171.

When assessing the relationship of boot camp to the Marines’ overall efficacy on Iwo Jima, the elements of discipline and training were elemental in overcoming the challenges of the battlefield. The drill instructors were stern, quick to correct, and expected discipline above all else. Retired Major General Walter Greatsinger Farrell attended Parris Island between August and October 1917 and remarked that his “drill instructors would carry ‘swagger sticks made of swab handles, and they used them freely’.”43 William Manchester, the author of Goodbye Darkness, who attended boot camp in spring 1942, said it was common to see a drill instructor bloody a man’s nose.44 Despite this, Robert Leckie in Helmet for My Pillow asserts that “the man who has it roughest is the man to be most admired . . . which is what we expected, what we signed up for.”45 There was a strong emphasis on the paternal drill instructor and little aversion to “rigorous physical punishment.”46 Major General Farrell commented that “by the time they were finished with me, I knew the meaning of instant obedience, and I understood the importance of loyalty up and down.”47 Eugene B. Sledge, who attended boot camp in 1943, commented that his drill instructor, Corporal T. J. Doherty, was a “strict disciplinarian, a total realist about our future, and an absolute perfectionist dedicated to excellence.”48

It was this reliance on strict discipline, instant obedience, and loyalty that provided the skeletal structure and muscle for Marines to do their duty on Iwo Jima. Without the ability to quickly react and follow orders without question, many may have remained in their foxholes or been unable to advance positions, sometimes without leadership direction.49 The Marines who participated in World War II were accustomed to harsh experiences and believed the rigors of boot camp prepared them to withstand the mental and physical challenges they would experience during the war.

After training at the main station concluded, the rifle range offered some much-needed respite from drill but operated in a different capacity to change a recruit into a Marine. As Corporal Bailey later wrote, “The most binding of rules—every Marine must be a potential fighting man. He must drill; he must shoot.”50 Corporal Bailey fully supported all Marines becoming effective riflemen, stating, “The idea works, it saves lives.”51 Therefore, desk duties and cooks also shot for record on the range. The first week at the rifle range was spent “snapping-in,” “learning proper sight setting, trigger squeeze, calling of shots,” and other essential principles.52 Even working the targets under the “buttmaster” served a purpose. The live ammunition firing overhead eventually became commonplace, so it would not distract troops from their objective in a theater of war. E. B. Sledge summarized the experiences at the Marine Corps recruit depot, writing, “At the time, we didn’t realize or appreciate the fact that the discipline we were learning in responding to orders under stress often would mean the difference later in combat—between success or failure, even living or dying.”53

Historic literature assesses the hourly and weekly schedules as well as subjects and skills to be mastered in boot camp, but there is minimal exploration on the psychological aspects and specific methods used to achieve this measurement of success.54 Marine Corps Ground Training in World War II dedicates chapter 2 to recruit training, giving the eight-week breakdown of peacetime training such as fundamentals of military life, elementary instruction in infantry combat, squad combat principles, and more. It also follows the changes in recruit training at the beginning of World War II, listing hours, such as the required 147 hours of rifle range training at Parris Island compared to 112 hours of rifle range training at the San Diego depot and the required marches to and from the range.55 However, these hourly logs and itemized training lists do not detail how these subjects were achieved.56 Many historians quote veterans to demonstrate these sentiments but fail to provide any cause-and-effect analysis. Exploring the psychological aspects of boot camp reveals that training in hand-to-hand combat prepared Marines for the enemy falling into one’s fox hole; constant boondocking prepared them for the terrain they would encounter on Iwo Jima and instilled the mental fortitude to trudge on; and bayonet practice trained them how to kill in close quarters. These hardships, sleepless hikes, repetition of Marine Corps lore, and reliance on their cohort were part of the methodology used to indoctrinate the Marine Corps ethos. While valued as a stepping stone to more elaborate training, boot camp is undervalued for creating the ethos, duty, and fighting spirit of the Marine so elemental to the success of Iwo Jima.

Replacement Training

After the training at either the recruit depot in Parris Island or in San Diego was complete, new Marines would head to their assigned units; but during World War II, the high casualty rates and rapidity of Pacific campaigns necessitated the transfer of some troops to replacement depots. Due to lessons learned in previous campaigns, a new feature of the Iwo Jima operation was to employ replacement battalions and attach them to the 3d, 4th, and 5th Marine Divisions to be used in assault shipping. Prior to embarkation, the intention was to train troops to seamlessly integrate into the regular division shore parties during the initial phase of assault, and if called on by the division, released as a combat replacement within the assault units.57 On 1 September 1943, the first infantry replacement training consisted of two weeks of physical conditioning. Shortly after, subsequent battalions began an eight-week course, including 68 hours of basic training, 97 hours of tactical training, and 171 hours of technical training (Browning Automatic Rifle [BAR], machine gun, rifle, mortar, and intelligence).58 Following enlisted recruit training, these Marines ordinarily would have received instruction that furthered skills and technical proficiency in a specific field.59 Replacement training was inconsistent and did not foster unit cohesion, and wartime exigencies placed a strain on the additional training received after boot camp.

To address reports returned from the Pacific stating that replacements were unprepared, the training centers attempted to alter the replacement training course’s realism. A combat reaction course was added in August 1943 as well as swimming, field sanitization, and demolitions.60 This schedule of training broke down into two four-week periods. The first four weeks were dedicated to basic individual training with weapons and individual and squad technical and tactical training. During the second period, training comprised offensive and defensive small unit exercises in jungle warfare. The schedule was again modified when the commanding general of the 2d Division commented that the replacements he received for Tarawa were “most unsatisfactory.”61 It was not until 21 July 1944 that the replacement training omitted jungle warfare and replaced it with bunker problems, emphasizing assault of heavily fortified islands. Very few replacements would have received this new training by the time they embarked for Iwo Jima. Replacement training should have provided additional experience beyond boot camp, furthering the skills of the Marine, but action reports oppose the assumption that the replacement training maintained proficiency and mastery in the unit specialty needed for the replacement unit. The reports stated that the instructors were inexperienced, that each instructor used unique methods, and that the training schedule was unreliable. Combat veterans were preferred as infantry instructors, however, this was difficult to accomplish because combat veterans were also direly needed in the field.62

Unit Training

Assessing the unit training of the 3d, 4th, and 5th Marine Divisions, conducted from activation (reactivation) to embarkation provides a more complete picture of what this additional experience provided in preparation for the battle on Iwo Jima. The 3d Division was reactivated on 16 June 1942, at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, and was made up of mostly recruits who attended boot camp at Parris Island, South Carolina.63 In May 1943, the division left New River and arrived in Samoa, where unit leaders focused on small group training with eight months of intensive field exercises. In August, 3d Division units were stationed on Guadalcanal to rehearse the Bougainville operation. Beginning on 1 November 1943, the division spent two months fighting against a strong Japanese enemy at Bougainville.64 The division was able to implement some lessons learned from Guadalcanal, such as individual camouflage (dyeing their white undershirts green, applying green and yellow paint to equipment and uniform, and using vegetable powder to stain skin green). After action reports recognized this as an important factor in reducing casualties.65 After the transfer of command in January 1944, the division returned to Guadalcanal and began training for the next campaign.

The last phase of their training before embarking to Guam was spent on board ships practicing landings for nine days. Unfortunately, most of the infantry battalions suffered heavy losses during the battle on Guam, and many of the troops headed for Iwo Jima were mainly composed of replacements received shortly before embarkation.66 Once the division’s mission was assigned, they began training for the various phases a reserve unit would pass through in landing and moving to an assault role. They did not perform an assault landing rehearsal since the division was not expected to be used in that capacity. The combat training of the 28th and 34th Replacement Drafts was found to be badly deficient, so in response, their training was devoted to individual and small unit training. Small unit training comprised simulating assault and reduction of emplacements using the flamethrower and rocket launcher. In the last week of December 1944, two replacement drafts joined the division whose training status consisted of only two to four weeks of recruit training.67 The additional training implemented after boot camp was struggling under casualties from previous engagements, shortages of equipment, and training inconsistencies within the reserve units. Recruit training was still the principal training received by all Marines headed to Iwo Jima.

The 4th Marine Division’s training was similar to that of the 3d Marine Division’s. In January 1943, the 23d Marines spent 15 days practicing amphibious maneuvers in the Chesapeake Bay. The majority of their training from September 1943 to January 1944 involved amphibious practice. While stationed at Camp Pendleton, California, they conducted bayonet practice, conditioning hikes, moving-target range practice, pillbox assaults, rubber boat landings, and combat swimming. On 21 January 1944, the majority of the division anchored off Maui, Hawaii. By 22 January, the convoy left and headed for the Marshall Islands to assault and capture the Roi-Namur Islands. They returned to Camp Maui by the end of February, however, by 13 May, troop loading finished and the 4th Division headed to Saipan.68 The troops were then slated to arrive in Tinian on 24 July and return to Maui by 14 August. The period on Maui between the return from Tinian and leaving for Iwo Jima was spent recuperating, hiking, practicing on the pistol range, live grenade practice, as well as using the Army facilities such as the infiltration course, jungle training center, and the village fighting course.69 During 15–30 November, the 4th Division conducted amphibious exercises in the Maalaea Bay area of Maui. The division’s combat engagement provided hands-on experience for the troops, observing how the enemy operates, and working together as a unit, but it also came at a price. They experienced 6,400 casualties on Saipan and Tinian, necessitating more replacement troops and delaying resupply materials for Iwo Jima. The division finally received its organic replacements on 22 November, but embarkation began only 36 days later. This left no time for the replacement troops to successfully integrate into the division or achieve any significant, needed training related to the operation.70 The gaps in troops were mostly filled by replacement troops or troops directly from recruit training. Their location, farthest from the objective, also necessitated that they ship out earlier than the other divisions. With a division made up of battle-fatigued veterans, replacements, and Marines directly from boot camp, the experience going into Iwo Jima was not standardized, except for the recruit training received at Parris Island or San Diego. Because of that common elemental training, this motley force of Marines was still able to function effectively against the Japanese on Iwo Jima.

The 5th Marine Division was activated 11 November 1943 and began its squad, platoon, company, battalion, and regimental training shortly after 8 February 1944, when division commander Major General Keller E. Rockey assigned the complete training schedule. This division was created with Operation Detachment as its immediate goal and wholly untested in battle. The primary training goal assigned to the 5th Marines by the master training schedule was the familiarization of the individual Marine with the tools of war (rifles, carbines, pistols, BAR, machine guns, tanks, and artillery). Once the Marines understood their individual weapons, the infantrymen began to operate in fireteams and drill in the assault tactics of squads and platoons. In April 1944, company commanders took their units to the field for unit training that consisted of firing practice with live ammunition, mock night operations, tactical marches, and three-day bivouacs.71 From 1 August to 30 September 1944, the division entered the Troop Training Unit commanded by Brigadier General Harry K. Pickett, which would train the Marines in the standards of amphibious warfare. An article published in the Marine Corps Gazette in August 1944 described unit training that included landing operation exercises, dry mock-ups, wet mock-ups, landing exercises in a landing craft, cargo net, and landing craft training. The completion of the two-week active training ended with actual landing exercises with and without supplies.72 Similar to the other divisions, only a few of the troops participating in the assault on Iwo Jima would have been able to attend this course. On 12 August, Major General Rockey and the 5th Marines sailed to Camp Tarawa in Hawaii. Once on board ship, the ability to conduct practical training diminished, and the Marines were reduced to conducting calisthenics, inspections, ship drills, and intelligence briefings. At Camp Tarawa, they began a review of basic small unit landing and team and combat training that lasted until the end of 1944, culminating in amphibious maneuvers.

On 16 December, the 5th Marines left for Pearl Harbor to practice takeoffs and landings on the landing ship, tank (LST), and by 10 January 1945, the entire division was waterborne. More rehearsals were conducted in Maui in the form of debarkation drills and landing the craft on the beaches, running ashore, then reembarking. On 11 February, the 5th Marines reached Saipan with a one-day invasion rehearsal; however, the assault waves were not landed.73 During the second week of February, the final rehearsals in the Mariana Islands included ships and aircraft, Task Force 52, and the Gunfire and Covering Force, Task 54. This was primarily to test coordination between the support force and attack force.74

Scholars place heavy emphasis on how well the scheme of amphibious training prepared the Marines for Iwo Jima, and for many Marines, these were the last rehearsals conducted before embarkation.75 The Japanese, however, did not assault the Marines upon landing, as anticipated. There were other limitations concerning the amphibious training conducted in the pre-embarkation phase of training. A V Amphibious Corps report recounted two full-scale rehearsals in the Hawaiian area involving all available major elements of the Joint Expeditionary Force. In the first rehearsal, the landing beaches were approached, but no troops were disembarked.76 A 13 May 1945 report from Commanding General Graves B. Erskine to the Commandant, General Alexander A. Vandegrift, regarding the V Amphibious Corps landing force stated that the rehearsals held in the Hawaiian area 11–18 January were insufficient due to the absence of amphibian tractors. Two battalions of cargo tractors and one armored amphibian battalion only received two days of training with the units.77 The 4th Tank Battalion was not present because of delayed loading of landing ships, medium (LSMs), and no six-wheel-drive amphibious DUKWs (officially designated as a landing vehicle, wheeled) were launched because of a need to prevent corrosion and deterioration of preloaded ammunition. LSTs were not beached due to the conditions of the reef.78

The replacement and unit training provided to Marines leading up to Iwo Jima was sporadic and varied. To summarize the unit training above: the 3d Division’s 28th and 34th Replacement Drafts were deficient in combat training and additional replacements had only received two to four weeks of recruit training. The 4th Division experienced heavy casualties throughout its training, and the training conducted after November 1945 was mostly amphibious related. The division comprised mostly replacements or troops directly out of boot camp. The 5th Division focused heavily on amphibious training during summer 1944, but when it came to final practices, equipment was missing, and troops were not landed. At the time of Iwo Jima, the replacement drafts “attached to the 5th Marine Division, the 27th, had received eight to 10 weeks training and the 31st only five to six weeks. The 3d Replacement Draft received only four of the prescribed 12 weeks infantry training and the 28th [Marines] departed for the Pacific with training deficiencies in almost all infantry subjects.”79 Most of the reports from division commanders state that their troops were in a satisfactory state of training when embarked, but reports submitted regarding the troops’ readiness in action differ.80 Replacement troops, high casualty rates, inconsistent instructors, and revolving operations in the Pacific narrowed the window of opportunity for Marines designated for the Iwo Jima operation to participate in and benefit from these additional training opportunities.

Marine Combat Performance on Iwo Jima

Plans were initiated to land the 4th Marine Division led by Major General Clifton B. Cates and the 5th Marine Division led by Major General Rockey on Iwo Jima the morning of 19 February 1945. The 3d Marine Division under the command of Major General Graves B. Erskine would remain as Expeditionary Troop Reserve.81 Fleet Admiral Nimitz estimated that, in the hands of the Marines, the capture of Iwo Jima would take 14 days. Once on shore, the Marines were to proceed with their assigned missions, one regiment of the 5th Marine Division to capture Mount Suribachi, and the 4th Marine Division would continue to Motoyama Airfield No. 1. These objectives were expected to be accomplished on the first day and then consolidated forces were to drive north over the Motoyama Plateau.82

Information in documents captured from Saipan implied that the Marines should expect to meet with enemy attempts to destroy their forces before they had established a beachhead, however, the first wave was met with negligible opposition. The enemy did not attempt a major counterattack but instead remained hidden in heavily fortified positions. The intelligence previously provided regarding the consistency of the sand was also incorrect. Once landed, the Marines found it was composed of loose, coarse, volcanic ash, which hindered most movement from jeeps or tanks and sunk a person’s feet up to the ankles. When the troops made it beyond the first terrace, they were seared by machine-gun and rifle fire while simultaneously being hit by mortar and artillery fire. The waves landed at five-minute intervals, but vehicles were damaged, destroyed, or stuck, which made unloading the following waves difficult. After advancing only 150–300 yards, movement was reduced. By noon, the enemy reaction was immense.83 Marines of the 23d Marine Regiment, 4th Marine Division, had managed somehow to push their lines to the base of the airfield while the 25th Marine Regiment kept pace toward the north. The Fourth Marine Division in World War II expands on the use of the word “somehow” as a “vague word and can be explained only in terms of countless acts of individual bravery working within the collective will of the whole unit.”84

Enormously high casualties and loss of equipment, ammunition, and supplies, in addition to continuous Japanese fire, further hampered forward progress of all the divisions involved. The Marines on Iwo Jima trudged on for 36 excruciating days on that “devil’s playground,” clearing a relentless, hidden Japanese force.85 The assault of Iwo Jima did not materialize the way planners envisioned. The terrain proved markedly more difficult, favoring the defender and providing little to no cover for the attacking Marines. It also froze elemental tanks and trucks where they landed, creating a situation that proved extremely difficult to unload and distribute ammunition and supplies. The number of Marines landed made it harder for the Japanese to miss their targets. Conducting extensive amphibious rehearsals was advantageous, but only to a certain extent. Training was conducted with the expectation that the planned heavy naval bombardments would destroy the majority of the fortified enemy positions, but no one could have foreseen the extent of the Japanese tunnels, or how ineffective the bombardment would be. Therefore, the divisions that landed on Iwo Jima had to improvise and adapt.

Though it seemed improbable, the Marines assaulting Iwo Jima slowly defeated the Japanese entrenched on that 8.1-square-mile island. Once the U.S. forces realized that the aerial and naval bombardment before troops landed did not effectively reduce the Japanese pillboxes, the Marines customized the necessary scheme of maneuver. They had to rely on the individual Marine and small combat troops to break up enemy fortifications to advance. The Marines involved in the victory on Iwo Jima either came directly from boot camp, had received reduced or ineffective training, or were already worn down by combat. However, every Marine on Iwo Jima had received boot camp training that made them effective riflemen, regardless of their specialty or occupation, and equipped them with the tools to withstand the rigors of war.

Individual Heroics, Institutional Training, or Both?

Historians appropriately recognize the heroics of the individual Marine in the assault on Iwo Jima. What is neglected is an analysis of why or how such a diverse group of Marines with inconsistent training could produce such a positive outcome. Iwo Jima’s narrative is rife with stories of individual acts of valor that assisted in the advance of a company or a battalion or saved the life of one fellow Marine or a whole unit. For each story recorded, there are numerous acts of bravery that have gone unrecognized. As discussed, Iwo Jima was overtaken and the Japanese enemy removed by individual Marines advancing their units. The Medal of Honor and Silver Star citations received for service during the battle of Iwo Jima corroborates this style of maneuver and highlights a few of the men who applied the strategy of individual and small combat movement, to break up enemy fortifications and to advance, and succeeded.

For example, Private First Class Douglas T. Jacobson, 4th Marine Division, received the Medal of Honor for commanding a bazooka after its operator was killed and covering his unit while they climbed Hill 38. He also destroyed machine-gun positions, attacked a blockhouse and multiple rifle emplacements, and assisted an adjacent company in advancing. He destroyed 16 enemy positions and killed approximately 75 Japanese.86

Corporal Harry C. Adams, 5th Marine Division, was awarded the Silver Star Medal for advancing through heavy fire and destroying an enemy strongpoint with a demolition charge, allowing his company to advance.87

Private Wilson Douglas Watson, 3d Marine Division, was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions on Iwo Jima. Private Watson single-handedly pinned down an enemy pillbox, allowing his platoon to advance to its objective. His platoon was again stalled at the foot of a hill, so Watson advanced alone, fighting off Japanese troops for 15 minutes, allowing his platoon to scale the slope.88

From arrival at boot camp until graduation during World War II, the enlisted Marine was conditioned for the rigors of war. Because of wartime exigencies, this may have been the only training a Marine received. Each training objective served a purpose to desensitize and acclimate recruits for the extreme conditions they would face on the battlefield. Colonel Ardant du Picq, before the Franco-Prussian War, remarked that “the aim of discipline is to make men fight, often in spite of themselves.”89 Bill D. Ross, a Marine Corps correspondent assigned to Iwo Jima, believed that success or failure hinges on the “first critical moments and the attack can go either way, all depending upon the training and discipline of the troops.”90 General Holland M. Smith and Percy Finch wrote in Coral and Brass that “Marines believed themselves to be the greatest fighting force because it was drummed into their heads since the day they signed up. . . . Building the Marine esprit de corps began with boot camp which was painfully tough . . . no Marine ever forgot his boot camp hitch.”91 Captain Bonnie Little, who was killed in action on Tarawa and awarded the Silver Star and Purple Heart, remarked that the “Marines have a way of making you afraid; not of dying, but of not doing your job.”92

In an article for Journal of Contemporary History, Hew Strachan remarked that training is an enabling process that creates self-confidence. He believed that the type of training the Marine Corps implemented during boot camp created the psychological capacity to elongate peak phases and surmount low phases. According to Strachan, this is completed through repeated drills and strict discipline. That way, when rational thought is impossible due to exhaustion, individuals react without thinking. Strachan also discusses the effectiveness of training with the bayonet. While not responsible for as many deaths as a firearm, this method of training provided the recruit with the ability to overcome the principal blocks to combat effectiveness.93

Regarding bayonet training and hand-to-hand combat using judo or jiujitsu received in boot camp, Stephen Stavers wrote that

a commander can hardly expect a real offensive spirit or an unhesitant assault if most of his men, lacking faith in their hand-to-hand combat effectiveness, feel more secure the farther they are from the enemy. . . . If the man laying prone in the jungle is as confident in his ability to fight hand to hand with knife, club, bayonet, or bare hands as he is in his ability to shoot, it is less likely that he will be frightened by noises or other distractions into firing blindly and giving away his position.94

Repeated boondocking prepared the Marines assaulting Iwo Jima for the unique terrain. After landing on Iwo, they had to exit the ramps and trudge through ankle-deep water amidst volcanic sludge; boondocking primed them for this unique obstacle.95 The rifle range acquainted the Marine with their weapon and taught them its extreme importance, making it an extension of the Marine and ensuring they would never be left without it. Also, the experience working the targets desensitized recruits to the sound of live fire, giving them the ability to function on the battlefield without being overwhelmed by noise. Each boot camp training element taught the recruit to overcome a new challenge or hardship by adapting, learning to rely on their fellow Marines, and accomplishing things previously thought impossible.

While partially successful, the pre-embarkation training pointed to the need for equipment and cohesive participation, the discontinuity of the number of troops who participated, the incongruity of instruction, and the dissimilar amount of training actually received by those slated for Iwo Jima.96 Rehearsals lacked realism, and replacement training was overwhelmingly described in the after action reports as prodigiously unsatisfactory. There is difficulty assessing what percent of troops received replacement training or any additional training after boot camp due to inconsistencies in reports and variations in length of training and instructors’ experience.97 Boot camp, however, was received by the overwhelming majority of Marines. The crucial elements of discipline, close order drill, sense of duty, and esprit de corps had been instilled in every Marine destined for Iwo Jima. The additional training did not make a Marine tactically superior on the battlefield. It is the initial boot camp training that made each Marine willing to keep fighting no matter what.

Conclusion

In conclusion, boot camp training proved more essential than the replacement or specific training conducted prior to Iwo Jima. This concept changes the understanding that Marine Corps training was standardized at all echelons. The training the Marine Corps conducted changed with instructors and locations and varied within units, platoons, companies, and battalions. It opens up the study to multiple questions about whether or not this situation is characteristic of the Marine Corps. If so, did this prove to be the case in other engagements such as Peleliu, Saipan, Tinian, and Okinawa? It also brings into question whether this condition was unique to World War II or if it can be applied to other wars in which the Marines were involved. Lastly, it provides an opportunity to juxtapose the Marine Corps alongside other branches of the military to determine if basic indoctrinations among the Services are similar or if Marine Corps boot camp is distinctive.

Historiography references only a few studies that place quantitative value on boot camp’s contribution, but personal testimonies from Marines demonstrate the vital importance it played in their battle readiness. It imbued a sense of duty and created essential rifleman merits that produced enough individuals to overcome the detrimental effects of fire on the Iwo Jima battlefield. Concerning the specific operational training designed for Iwo Jima, the amphibious rehearsals were incomplete, lacking realism, and the enemy did not react the way planners had conceived. Replacement training was unsatisfactory due to inconsistencies with instructors, instruction, and the schedule. The training received during boot camp was more important to the efficacy of the Marines fighting on Iwo Jima. It was the discipline and esprit de corps instilled in the recruit that imparted the will to overcome insurmountable obstacles and steadfast dedication to each other and their Corps.

•1775•

Endnotes

-

There are several, but some notable examples are: Robert S. Burrell, The Ghosts of Iwo Jima, Williams-Ford Texas A&M University Military History Series (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2006); Victor Krulak, First to Fight: An Inside View of the U.S. Marine Corps (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1984); Karal Ann Marling and John Wetenhall, Iwo Jima: Monuments, Memories, and the American Hero (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991); Bernard C. Nalty and Danny J. Crawford, The United States Marines on Iwo Jima: The Battle and the Flag Raising (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1995); and Richard Wheeler, The Bloody Battle for Suribachi (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1965).

-

Iwo Jima was highly praised by Navy Fleet Adm Chester W. Nimitz on 16 March 1945: “Among the men who fought on Iwo Jima, uncommon valor was a common virtue.” See also Nalty and Crawford, The United States Marines on Iwo Jima, for information on Joseph Rosenthal’s “Flag Raising on Iwo Jima” photograph in newspapers from 1945 such as The Decatur (IL) Daily Review, The Lincoln (NE) Star, The Honolulu (HI) Advertiser, The New York Times, and Time and Life magazines in February and March 1945.

-

Joseph Alexander argues that “the troops assaulting Iwo Jima were arguably the most proficient amphibious forces the world had seen.” Joseph H. Alexander, Closing In: Marines in the Seizure of Iwo Jima (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1994), 3. George Garrand and Truman Strobridge make the closing argument that the success of the Marines on Iwo Jima is “proof of the latter’s courage, highly advanced state of training, and the soundness of amphibious doctrine that had become an integral part of Marine Corps tactics.” George W. Garand and Truman R. Strobridge, History of the U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II, vol. 4, Western Pacific Operations (Washington, DC: Historical Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1971), 737.

-

Jeter A. Isely and Philip A. Crowl, The U.S. Marines and Amphibious War: Its Theory, and Its Practice in the Pacific (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1951), 475.

-

3d Marine Division Reinforced: Iwo Jima Action Report, 31 October 1944–16 March 1945, pt. 6 (San Francisco, CA: Headquarters V Amphibious Corps, 1945), 24; Headquarters, Expeditionary Troops, Task Force 56, G-3 Report of Planning, Operations: Iwo Jima Operation, encl. B (San Francisco, CA: Headquarters Fleet Marine Force Pacific, 1945), 20, 37; and Kenneth W. Condit, Gerald Diamond, and Edwin T. Turnbladh, Marine Corps Ground Training in World War II (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1956), 192–94.

-

Robert S. Burrell, “Breaking the Cycle of Iwo Jima Mythology: A Strategic Study of Operation Detachment,” Journal of Military History 68, no. 4 (October 2004): 1143–45, https://doi/org/10.1353/jmh.2004.0175.

-

Breanne Robertson, ed., Investigating Iwo: The Flag Raising in Myth, Memory, and Esprit de Corps (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps History Division, 2019), 85–90.

-

Statement made by FAdm Chester W. Nimitz to pay tribute to the Marines who fought on Iwo Jima. See “Communiqué No. 300, March 16, 1945,” in Navy Department Communiques 301 to 600 and Pacific Fleet Communiques, March 6, 1943 to May 24, 1945 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1946).

-

The U.S. Marines and Amphibious War details specifically troop training, embarkation, and rehearsals. These details include rehearsals beginning in the fall of 1944. It also looks at the evolution of amphibious doctrine and its training implementation up until the attack on Iwo Jima. Isely and Crowl, The U.S. Marines and Amphibious War, chaps. 3 and 10. Marine Corps Ground Training in World War II provides detailed lists of recruit training to include major subjects, rifle range periods pre-World War II, and the changes made during World War II. It gives hours spent on each subject and goals in each skill, but it does not detail specifically how the instructors were supposed to administer these sections or how esprit de corps was/should be established among the new recruits. Condit, Diamond, and Turnbladh, Marine Corps Ground Training in World War II, 12–30, 158–94.

-

Condit, Diamond, and Turnbladh, Marine Corps Ground Training in World War II. Condit and Turnbladh also coauthored Hold High the Torch: A History of the 4th Marines (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1960). See also multiple works coauthored or edited by Gerald Diamond, Edwin Turnbladh, and other historians for the Marine Corps’ Historical Branch in the series History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II (1958–71).

-

Condit, Diamond, and Turnbladh, Marine Corps Ground Training in World War II, 9.

-

Garand and Strobridge, Western Pacific Operations, 737.

-

It is stated in the special action report that “our battle casualties were some 30 per cent of the entire Landing Force. In the infantry regiments, however, those casualties counted to an average of 75 per cent in the two assault divisions and 30 per cent in the 3d Marine Division, of the original regimental strength. Furthermore, the loss in key personnel, particularly leaders, was even higher.” V Phib Corps Landing Force Report on Iwo Jima Campaign (San Francisco, CA: Headquarters V Amphibious Corps, 1945), 1-12.

-

3d Marine Division Reinforced: Iwo Jima Action Report, 31 October 1944–16 March 1945.

-

3d Marine Division Reinforced: Iwo Jima Action Report, 31 October 1944–16 March 1945.

-

Isely and Crowl, The U.S. Marines and Amphibious War, 432.

-

V Phib Corps Landing Force Report on Iwo Jima Campaign, 4–5.

-

Annex King to Fourth Marine Division Operations Report, 4th Engineer Battalion Report (San Francisco, CA: Headquarters V Amphibious Corps, 1945), 2; V Phib Corps Landing Force Report on Iwo Jima Campaign, 2; and Annex Mike to Fourth Marine Division Operations Report, Iwo Jima, 2nd Armored Amphibian Battalion Report (Headquarters, 2d Armored Amphibian Battalion, Fleet Marine Force Pacific, 1945), 3.

-

Headquarters, Expeditionary Troops, Task Force 56, G-3 Report of Planning, Operations: Iwo Jima Operation, encl. B.

-

Headquarters, Expeditionary Troops, Task Force 56, G-4 Report of Logistics, Iwo Jima Operation, encl. D (San Francisco, CA: Headquarters Expeditionary Troops, Fifth Fleet, 1945), 7.

-

Isely and Crowl, The U.S. Marines and Amphibious War, 458.

-

Condit, Diamond, and Turnbladh, Marine Corps Ground Training in World War II, 183.

-

Condit, Diamond, and Turnbladh, Marine Corps Ground Training in World War II, 186.

-

This Replacement Training Center was originally in New River, NC, and then moved to Samoa until July 1943, at which point it was moved to Camp Lejeune, NC. It was not until 21 July 1944 that the replacement training centers omitted jungle warfare and replaced it with bunker problems with an emphasis on assaulting heavily fortified islands. However, very few replacements would have participated in this training before their embarkation date. See Condit, Diamond, and Turnbladh, Marine Corps Ground Training in World War II, 185; and V Phib Corps Landing Force Report on Iwo Jima Campaign, 2.

-

Condit, Diamond, and Turnbladh, Marine Corps Ground Training in World War II, 9.

-

Condit, Diamond, and Turnbladh, Marine Corps Ground Training in World War II, 9.

-

Maj Paul K. Van Riper, Maj Michael W. Wydo, and Maj Donald P. Brown, An Analysis of Marine Corps Training (Newport, RI: Center for Advanced Research, Naval War College, 1978), 176–77.

-

Condit, Diamond, and Turnbladh, Marine Corps Ground Training in World War II, 165.

-

Condit, Diamond, and Turnbladh, Marine Corps Ground Training in World War II, 172–73.

-

Conrad C. Crane et al., Learning the Lessons of Lethality: The Army’s Cycle of Basic Combat Training, 1918–2019 (Carlisle, PA: U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center, 2019), 1–20.

-

Robert R. Palmer, Bell Wiley, and William R. Keast, United States Army in World War II: The Army Ground Forces—The Procurement and Training of Ground Combat Troops (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1991), 1.

-

Army Air Forces Historical Studies No. 49: Basic Military Training in the AAF, 1939–1944 (Washington, DC: Army Air Force Historical Office, Headquarters Army Air Forces, 1946).

-

Army Air Forces Historical Studies No. 49: Basic Military Training in the AAF, 1939–1944 (Washington, DC: Army Air Force Historical Office, Headquarters Army Air Forces, 1946).

-

Spickelmier, “Training of the American Soldier During World War I and World War II,” 100; and W. F. Craven and J. L. Cate, The Army Air Forces in World War II, vol. 6, Men in Planes (Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History, 1983), chap. 16, provide an hourly breakdown of the basic training received at Jefferson Barracks in October 1940. They note that “two observations are pertinent—the emphasis on infantry subjects, and absence of weapons training” regarding the Army basic training at that time. Crave and Cate, The Army Air Forces in World War II, vol. 6, 530.

-

William R. Keast, Major Developments in the Training of Enlisted Replacements, Study No. 32 (Washington, DC: Historical Section, U.S. Army Ground Forces, 1946).

-

Spickelmier, “Training of the American Soldier during World War I and World War II,” 104.

-

Army Air Forces Historical Studies No. 49: Basic Military Training in the AAF, 1939–1944, 11.

-

Army Air Forces Historical Studies No. 49: Basic Military Training in the AAF, 1939–1944, 82. See article for a similar statement made about Marine Corps replacement training.

-

Cpl Gilbert P. Bailey, USMCR, Boot: A Marine in the Making (New York: Macmillan, 1944), 1. There is a possibility that this work contains some Corps propaganda, but the author found no evidence to suggest it is not factual. While it was published by Macmillan in 1944, not Headquarters Marine Corps, the photographs it includes were taken by Cpl Edward J. Freeman and PFC John H. Birch Jr. in cooperation with the Public Relations Office, Parris Island, SC. However, there is no other mention of the book being published with affiliations to the Marine Corps and it is a personal account of its author’s experience in boot camp.

-

“Boot Camp,” Leatherneck 25, no. 5 (May 1942): 5–29, 66.

-

Bailey, Boot, 75.

-

“Boot Camp,” 5–20, 22–23, 25–29, 66; Charles Edmundson, “Why Warriors Fight,” Marine Corps Gazette 28, no. 9 (September 1944): 2–10; Capt Clifford P. Morehouse, “Amphibious Training,” Marine Corps Gazette 28, no. 8 (August 1944): 34–43; Lt Stephen Stavers, “Individual Combat Training,” Marine Corps Gazette 27, no. 1 (March/April 1943): 5–7; Col Charles A. Wynn, “A Marine Is Different,” Marine Corps Gazette 28, no. 5 (May 1944): 13–15; E. B. Sledge, With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa (New York: Presidio Press, 2007); Robert Leckie, Helmet for My Pillow: From Parris Island to the Pacific (New York: Bantam Books, 2010); Charles E. Baker, interview with Tamika Jones, 30 September 2005, oral history (Charles E. Baker Collection, Veterans History Project, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress); Frank Saffold Brown, interview with Jack Atkinson, 4 February 2005, oral history (Frank Saffold Brown Collection, Veterans History Project, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress); and Bryan Leland Clark, interview with Stephanie Leopard, 8 July 2004, oral history (Bryan Leland Clark Collection, Veterans History Project, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress).

-

Krulak, First to Fight, 167.

-

William Manchester, Goodbye Darkness: A Memoir of the Pacific War (Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 1980), 120.

-

Leckie, Helmet for My Pillow, 6.

-

Krulak, First to Fight, 167.

-

Krulak, First to Fight, 167.

-

Krulak, First to Fight, 172.

-

PFC Franklin Sigler took charge, after a squad leader casualty, by killing an enemy gun crew with grenades, and subsequently saved three other Marines. “Private First Class Franklin Earl Sigler, USMCR (Deceased),” Marine Corps Medal of Honor Recipients, World War II, 1941–1945, Marine Corps History Division website, accessed 1 December 2020. See also V Phib Corps Landing Force Report on Iwo Jima Campaign.

-

Bailey, Boot, 31.

-

Bailey, Boot, 31.

-

Sledge, With the Old Breed, 12.

-

Sledge, With the Old Breed, 11.

-

Condit, Diamond, and Turnbladh, Marine Corps Ground Training in World War II, 9–30; and Elmore A. Champie, A Brief History of Marine Corps Recruit Depot, Parris Island, South Carolina 1891–1962 (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division Headquarters Marine Corps, 1962), 10–12.

-

Condit, Diamond, and Turnbladh, Marine Corps Ground Training in World War II, 19–30.

-

Condit, Diamond, and Turnbladh, Marine Corps Ground Training in World War II, 12, 13, 22, 158–66, 172.

-

Headquarters, Expeditionary Troops, Task Force 56, G-4 Report of Logistics, Iwo Jima Operation, encl. D, 7.

-

Condit, Diamond, and Turnbladh, Marine Corps Ground Training in World War II, 178.

-

Van Riper, Wydo, and Brown, An Analysis of Marine Corps Training, 176.

-

Condit, Diamond, and Turnbladh, Marine Corps Ground Training in World War II, 180–82.

-

Condit, Diamond, and Turnbladh, Marine Corps Ground Training in World War II, 186.

-

Condit, Diamond, and Turnbladh, Marine Corps Ground Training in World War II, 185–90.

-

By the end of 1942, 3d Marine Division included the 9th, 12th, 19th, 21st, and 23d Marines; the 3d Special Weapons Battalion; the 3d Service Battalion; the 3d Medical Battalion; and the 3d Amphibian Tractor Battalion. All were located at Camp Elliott in San Diego, except the 21st and 23d Marines, which were at New River, NC. The 3d Marine Division and Its Regiments (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1983), 1.

-

The 3d Marine Division and Its Regiments, 1.

-

David C. Fuquea, “Bougainville: The Amphibious Assault Enters Maturity,” Naval War College Review 50, no. 1 (Winter 1997): 113–14.

-

1stLt Robert A. Arthur and 1stLt Kenneth Cohlmia, The Third Marine Division, ed. LtCol Robert T. Vance (Washington, DC: Infantry Journal Press, 1948), 7–10.

-

3d Marine Division Reinforced: Iwo Jima Action Report, 31 October 1944–16 March 1945, pt. 1, 7.

-

1stLt John C. Chapin, The 4th Marine Division in World War II (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1976), 7.

-

Carl W. Proehl, ed., The Fourth Marine Division in World War II (Washington, DC: Infantry Journal Press, 1946), 58.

-

Isely and Crowl, The U.S. Marines and Amphibious War, 460.

-

Howard M. Conner and Keller E. Rockey, The Spearhead: The World War II History of the 5th Marine Division (Washington, DC: Infantry Journal Press, 1950), 3.

-

Morehouse, “Amphibious Training,” 35.

-

Conner and Rockey, The Spearhead, 19–23.

-

Headquarters, Expeditionary Troops, Task Force 56, G-3 Report of Planning, Operations: Iwo Jima Operation, encl. B, pt. 1 (San Francisco: Headquarters Fleet Marine Force Pacific, 1945), 21.

-

Garand and Strobridge, Western Pacific Operations, 737; and Isely and Crowl, The U.S. Marines and Amphibious War, 432.

-

Headquarters, Expeditionary Troops, Task Force 56, G-3 Report of Planning, Operations: Iwo Jima Operation, pt. 1, 20–21.

-

V Phib Corps Landing Force Report on Iwo Jima Campaign, 1–2.

-

LtCol Whitman S. Bartley, Iwo Jima: Amphibious Epic (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1954), 36.

-

Condit, Diamond, and Turnbladh, Marine Corps Ground Training in World War II, 193.

-

V Phib Corps Landing Force Report on Iwo Jima Campaign, 1–3.

-

Barnard C. Nalty and Danny J. Crawford, The United States Marines on Iwo Jima: The Battle and the Flag Raisings (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1995), 3.

-

Rathgeber, “The United States Marine Corps and the Operational Level of War,” 21.

-

Bartley, Iwo Jima, 474–75; V Phib Corps Landing Force Report on Iwo Jima Campaign, 3, 5; Proehl, The Fourth Marine Division in World War II, 149; Nalty and Crawford, The United States Marines on Iwo Jima, 3; and Isely and Crowl, The U.S. Marines and Amphibious War, chap. 10.

-

Proehl, The Fourth Marine Division in World War II, 149.

-

Isely and Crowl, The U.S. Marines and Amphibious War, chap. 10.

-

Proehl, The Fourth Marine Division in World War II, 15.

-

Cpl Harry C. Adams, Silver Star Medal citation, “USMC Silver Star Citations WWII (A),” U.S. Marine Corps WWII Silver Star Citations website, 13.

-

Pvt Wilson Douglas Watson, Medal of Honor citation, Congressional Medal of Honor Society (website).

-

Hew Strachan, “Training, Morale, and Modern War,” Journal of Contemporary History 41, no. 2 (April 2006): 211–27, https://doi.org/10.1177/0022009406062054.

-

Bill D. Ross, Iwo Jima: Legacy of Valor (New York: Vanguard, 1985), 66.

-

Holland M. Smith and Percy Finch, Coral and Brass (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1949), 57.

-

Ross, Iwo Jima, 69.

-

Strachan, “Training, Morale and Modern War,” 211–27.

-

Stavers, “Individual Combat Training,” 6.

-

Nalty and Crawford, The United States Marines on Iwo Jima, 3.

-

Arthur and Cohlmia, The Third Marine Division, 7–10; Garand and Strobridge, Western Pacific Operations, 737; Isely and Crowl, The U.S. Marines and Amphibious War, 432; and Headquarters, Expeditionary Troops, Task Force 56, G-3 Report of Planning, Operations: Iwo Jima Operation.

-

Headquarters, Expeditionary Troops, Task Force 56, G-3 Report of Planning, Operations: Iwo Jima Operation, pt. 1, 20–21; Condit, Diamond, and Turnbladh, Marine Corps Ground Training in World War II, 178; and Van Riper, Wydo, and Brown, An Analysis of Marine Corps Training, 176.