PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

Abstract: In the past decades, most conformist studies dedicated to the Vietnam War were overly critical of the U.S. military’s so-called reliance on conventional warfare in a country deemed to be plagued by an insurgency. Counterinsurgency programs were labeled weak and powerless to shift the Americans’ momentum against the Viet Cong, which outsmarted the U.S. military. This article opposes these theories and suggests that by 1969, the U.S. force’s reliance on conventional warfare against the guerrillas progressively morphed into a strategy that fully supported the military’s counterinsurgency initiatives. Vietnam was a hybrid warfare theater, which required the Americans to fight both the Viet Cong guerrillas and Hanoi’s conventional forces. Through the analysis of U.S. and Communist documents, this study suggests that the Americans succeeded in offsetting the Communists’ tactical approach to hybrid warfare. As they skillfully synchronized regular warfare with counterinsurgency, the U.S. and South Vietnamese forces succeeded in defeating the Viet Cong insurgency by the spring of 1972.

Keywords: Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development Support, CORDS, Central Office for South Vietnam, COSVN, counterinsurgency, hybrid warfare, insurgency, North Vietnamese Army, Phoenix, Viet Cong

Introduction

Since the end of the Vietnam War in 1975, orthodox historians have highly criticized the U.S. armed forces’ strategy in Southeast Asia. Writers have frequently blamed the military for its tendency to favor conventional military tactics in a country deemed to be plagued by an insurgency. Author John A. Nagl claimed that the U.S. Army “resisted any true attempt to learn how to fight an insurgency” but preferred to treat Vietnam as a conventional war.1 Andrew F. Krepinevich stated that the U.S. military’s approach to Vietnam was “unidimensional” and that a traditional approach to warfare was adopted in Vietnam with conventional war doctrines.2 Lewis Sorley underlined how U.S. Military Assistance Command Vietnam’s (USMACV) commanding officer, General William C. Westmoreland, marginalized counterinsurgency in favor of conventional war tactics.3 Max Boot branded the conventional war effort as “futile” in Vietnam and claimed that the Americans’ defeat was mainly the result of “a military establishment that tried to apply a conventional strategy to an unconventional conflict.”4

Douglas Porch went further when he stated that counterinsurgency could not work in Vietnam and that it “often made the problem worse in the view of the population.”5 Two military foes threatened the U.S. forces on Vietnam’s battlefield: the regular units of the North Vietnamese Army (NVA), which exploited a conventional form of warfare, and the National Liberation Front, also known as the Viet Cong, which used guerrilla warfare tactics coupled with conventional doctrines. Although North Vietnamese and Viet Cong troops cooperated and occasionally conducted joint operations, they usually operated in different areas. The NVA operated in the vicinity of the demilitarized zone (DMZ), the Central Highlands, and near the borders of Laos and Cambodia, while the Viet Cong deployed its main force in the populated areas located in South Vietnam’s lowlands. Vietnam was an unorthodox battlefield compared to the U.S. military’s previous wars in Korea, the Pacific, and Europe. Given the critical role played by its regular and irregular military actors, the Vietnam War remains the most prominent example of a hybrid warfare battlefield in modern military history. While the term hybrid warfare may seem better suited to describe twenty-first-century conflicts, it is entirely justifiable to use it to describe Vietnam. In the book Hybrid Warfare, the term refers to a conflict that involves a “combination” of conventional military forces and irregular units, which may include “both state and nonstate actors, aimed at achieving a common political purpose.”6

In Vietnam, the NVA and Viet Cong guerrillas both fought for a common political and strategic purpose: South Vietnam’s unification with the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam). However, such a common goal did not imply that Hanoi’s politburo and Viet Cong members were united under a single banner, a subject that will be addressed later. Several schools of thought identified similar branches or types of warfare that can also be associated with Vietnam. For instance, a group of U.S. Marine Corps officers introduced the theory of fourth-generation warfare in 1989. In essence, they assessed that “the nature of warfare has transformed via three main generations: (1) manpower, (2) firepower, (3) manoeuvre.” The so-called fourth generation emerged in the late twentieth century and is described as “an evolved form of insurgency” that exploits the political, social, economic and military systems to persuade an enemy that its strategic objectives are unattainable.7 Such a form of warfare can also be linked to Hanoi’s overall strategy against Washington in Vietnam. Later in the 1990s, Thomas Uber elaborated the theory of compound warfare, characterized by what he termed the “simultaneous use” of regular and guerrilla forces against an opponent. The relationship of these forces is symbiotic in nature: the guerrilla forces “enhance” the efforts of the regular units with intelligence, provisions, and combatants while conventional troops assist the guerrillas with training, supplies, combat support, and political leverage. Uber went further when he presented the fortified compound warfare theory in which the regular forces will have access to a “safe haven” and will be allied with a “major power.”8

With actors such as the NVA, the Viet Cong, the Soviet Union, Communist China, and the presence of the Laotian and Cambodian Communist bases, it is no surprise that Uber used Vietnam as a reference for such a form of warfare. He also cited the American Revolution, the Peninsular War (1808–14), and the Soviet Afghan War (1979–89) as examples.9 It could also easily be applied to the French Indochina War (1946–54) that opposed the French to the Vietminh. In more recent years, the term hybrid warfare was used to describe how Hezbollah fought the Israeli Army in 2006 and how the Russian military operated in Eastern Ukraine in 2014. As technology evolves, so do the tools available to wage war. With cyber warfare, signal intelligence, drones, and other advanced technologies being mixed with guerrilla and conventional military elements on the modern battlefield, it may be tempting to restrict the term hybrid warfare to twenty-first-century conflicts. However, regardless of technology and modern forms of warfare, the basics of hybrid conflicts and their variants are centuries old. They can be linked to the French and Indian War, the American Revolution, the Second Sino-Japanese War, the Indochina War, the Vietnam War, and many other conflicts. In Vietnam, the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) and U.S. battalions were targeted through asymmetric and regular tactics. As it fought against one of the finest conventional militaries of the time, USMACV had to develop a counterinsurgency plan to simultaneously neutralize what was perhaps the most efficient and battle-hardened insurgency of the twentieth century. The U.S. Marine Corps launched its own program called the Combined Action Platoons (CAP). It aimed at deploying Marine squads in villages alongside paramilitary forces. The initiative managed to cut off the Viet Cong guerrillas from the rural population and reinstated security and stability in several areas of northern South Vietnam. While the program was a tactical success, it was limited in its scope and severely hindered by the conventional military threat posed by the NVA near the DMZ and by the 1968 Tet offensive.

In 1967, the Americans and South Vietnamese launched the Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development Support (CORDS) program, which aimed to curtail the Viet Cong’s influence in the rural villages and pacify the countryside. While some of the CORDS and CAP programs’ achievements are acknowledged by Krepinevich, Nagl, and Boot, their overall assessment is that such initiatives had a limited strategic impact on the battlefield and that pacification efforts were too little and too late. In The Insurgents, Fred Kaplan wrote that CORDS was a “mixed success at best.”10 In Counterinsurgency, Douglas Porch branded CAPs and CORDS as “promising initiatives” that were “underresourced” and “developed too late” to alter the course of the war. Porch also stated that “the U.S. Army lacked a mindset and institutional structure to ‘learn’ and adjust its doctrine and tactics to achieve success.”11 These historians’ most common argument regarding CORDS is that while the initiative was commendable, it was ultimately overshadowed by USMACV’s overreliance on firepower and conventional military doctrines against the guerrillas. This article goes against these theories and suggests U.S. and South Vietnamese forces soundly defeated the insurgency, militarily and politically, through both the CORDS program and the support of regular military units. When confronted with a hybrid threat, military commanders must synchronize the operation of their conventional and nonconventional forces to prevent the enemy from using its guerrilla and conventional units as a force multiplier on the battlefield. This article will show that from 1969, conventional warfare and firepower were by no means the centerpiece of USMACV’s way of conducting counterinsurgency. At this point in the war, conventional doctrines and intelligence were used to better support USMACV’s counterinsurgents, which drastically improved CORDS’s ability to neutralize the insurgency. CORDS was a system that embodied all the fundamentals of counterguerrilla warfare as it should be conducted. Through the cooperation of multiple civilian, military, and intelligence agencies, CORDS achieved its main operational goals by the spring of 1972.

Concretely, these goals were to destroy the Viet Cong’s political influence, establish a proficient and self-reliant security force in the villages, separate the civilians from the guerrilla forces, and reestablish the government of Vietnam’s control in the contested villages. To do so, U.S. advisors attached to CORDS mentored and supervised their South Vietnamese counterparts without being excessively involved, which enabled the South Vietnamese to progressively become self-reliant and autonomous. Such a course of action is essential if any counterinsurgency hopes to succeed in the long term. While the U.S. Marines’ CAP program was in many ways a textbook counterinsurgency strategy, it lacked this particularity as the South Vietnamese became too reliant on the Marines for support. With CORDS, the U.S. maximized the use of host nation security forces while founding the proper balance between hard power and soft power. In 1972, the Viet Cong was effectively defeated by a proper equilibrium of counterinsurgency and regular warfare.

The Communists' Political Infrastructure and the Corps' Counterinsurgency Initiative

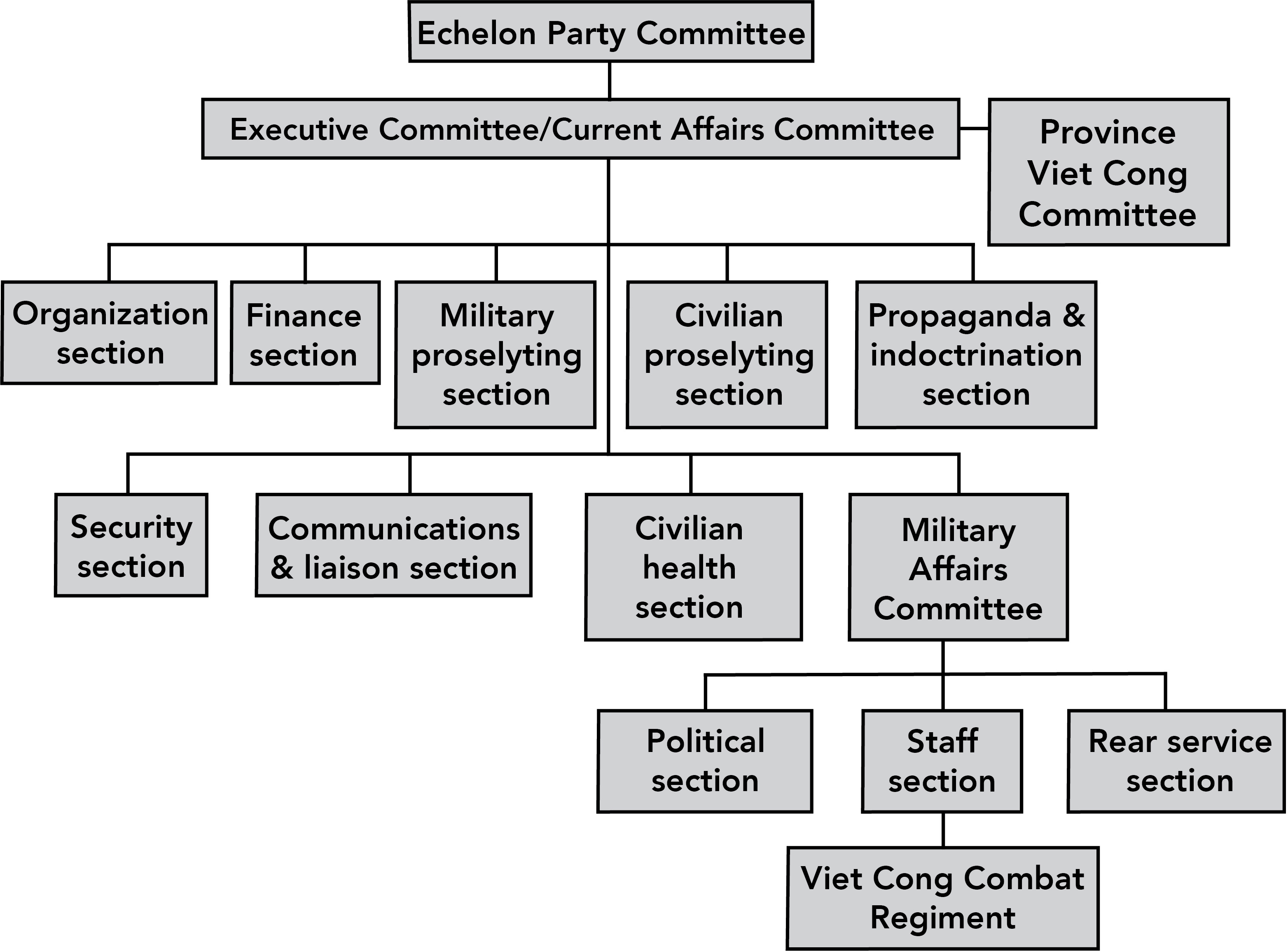

The U.S. military leadership’s three main strategic targets in Vietnam were the NVA divisions, the Viet Cong units, and the insurgency’s shadow government (figure 1). While Hanoi and the Viet Cong were allies in their struggle against Washington and Saigon, they still had their differences. There was a high degree of rivalry and distrust between the Lao Dong (Workers’) Party leaders in Hanoi and Communist leaders in the South. The National Liberation Front (Viet Cong) was created in 1960 and consisted of Hanoi’s response to peasant uprisings against the South Vietnamese government. From Hanoi, North Vietnamese leader Le Duan closely monitored the insurgent movement in the south through the Central Office for South Vietnam (COSVN), which superseded the Viet Cong in authority and acted as the organization’s main headquarters.

Le Duan appointed one of his most trusted military commanders, General Nguyen Chi Thanh, as leader of the COSVN. Le Duan sought to ensure his control of insurgent operations and stifle any opposition to his policies. For instance, many Viet Cong members resisted Le Duan’s wishes to turn the insurgency into a conventional fighting force.12 The differences between the two groups were also ideological in nature. As explained by senior Viet Cong defector Truong Nhu Thang, many southerners were more Nationalist than Communist.13 While directed and supported by Hanoi, the Viet Cong could rely on its whole political infrastructure to oppose Saigon. The infrastructure was active at the regional, provincial, district, village, and hamlet levels in South Vietnam (figure 1). Its political cadres sought to control every facet of the peoples’ lives toward the insurgency’s support and competed with Saigon to control the population. In the areas dominated by the Viet Cong, the infrastructure acted as an official government. In contested areas, it led a propaganda and terrorist campaign to undermine the government’s control and credibility.14 If U.S. and South Vietnamese forces hoped to win the fight against the Communists, destroying Hanoi’s NVA and the COSVN’s Viet Cong battalions would not be enough; they also had to neutralize their enemy’s well-elaborated political infrastructure. The U.S. Marines were the first to apply a doctrine that maximized the chance of neutralizing the Communist shadow government in the villages.

Figure 1. Communist political infrastructure in South Vietnam—provincial level

Courtesy of Ismaël Fournier. Based on a chart in Background and Draft Materials for U.S. Marines in Vietnam: The Defining Year, 1968.

The III Marine Amphibious Force (III MAF) operated in I Corps and was led by General Lewis W. Walt. His forces were subordinated to Westmoreland’s USMACV, whose units operated in II, III, and IV Corps (figure 2). At first, Walt expressed his desire to minimize conventional search-and-destroy missions against large Communist units to maximize counterinsurgency operations. Westmoreland was highly critical of the Marine Corps, which, according to him, should have set its focus on conventional war. Much literature has been dedicated to Westmoreland’s views on how the war had to be fought. Lewis Sorley criticized Westmoreland’s so-called reluctance in executing counterinsurgency in Westmoreland: The General Who Lost Vietnam.15 On the other hand, revisionist historians such as Gregory Daddis emphasized that USMACV’s commanding officer was fully aware of the importance of pacification and conceptualized his battleplan accordingly.16 The U.S. Army general was not a stranger to counterinsurgency doctrines. While he had no field experience in counterguerrilla warfare, his lack of practical knowledge did not detract from his interest in the matter. While serving as director of the West Point Military Academy in New York, he initiated a training program focused on insurgency principles and counterinsurgency warfare for cadets. When he served as deputy commander of USMACV under General Paul D. Harkins, he led a mission to Malaya to study British counterinsurgency tactics.17 During a visit to Hong Kong in the early 1960s, Westmoreland met David Galula, a French military officer who served in the Algerian War. Galula is one of the most renowned counterinsurgency experts of the twentieth century and was even nicknamed the “Clausewitz of Counterinsurgency” by General David H. Petraeus.18 Westmoreland was impressed with Galula’s theories and invited him to the United States to instruct the military on counterinsurgency dynamics.19

Figure 2. Provinces and military regions (Corps) of South Vietnam.

Vietnam Documents and Research Notes Series: Translation and Analysis of Significant Viet Cong/North Vietnamese Documents, microfilm. ProQuest Folder 003233-003-0762

Moreover, a thorough analysis of Westmoreland’s papers clearly shows that the U.S. Army general had, indeed, a solid battle plan that aimed to conduct counterinsurgency alongside conventional operations in Vietnam.20 However, proper execution of such a plan was the problem given the threat posed by fully armed Viet Cong regiments and battalions. In early 1965, approximately 47 of these Viet Cong battalions were operational in South Vietnam.21 While these units were mainly on the move, they had a highly developed network of campsites and bivouacs that they used as staging areas. Villages were also part of this network. Communist forces occupied the peoples’ houses, dug up trenches, and set up defensive positions that several companies could occupy.22 Such a situation resulted in multiple firefights in the vicinity of rural villages. In one highly publicized instance, a whole Viet Cong infantry company entrenched in the village of Cam Ne ambushed a Marine patrol, resulting in casualties among both the Marines and the villagers.23 Events such as these exposed the urgency of deploying counterinsurgents in the villages to disrupt the Viet Cong’s operation within the rural population. While Westmoreland underlined that he believed in pacification, he claimed that he did not have enough troops to carry out a program similar to that of the Corps across South Vietnam.24 Despite Westmoreland’s criticism, the Fleet Marine Force’s commanding officer in the Pacific, General Viktor H. Krulak, gave his blessing to General Walt, who authorized the initiation of the CAP program in 1965. The CAPs aimed to protect the rural population against insurgents by permanently deploying a squad of Marines alongside a South Vietnamese paramilitary platoon of the Popular Force to fortified villages.

CAP Marines and South Vietnamese paramilitary forces preparing for an ambush against the Viet Cong.

Photo by Ronald E. Hays, U.S. Department of Defense (Marine Corps), A185800

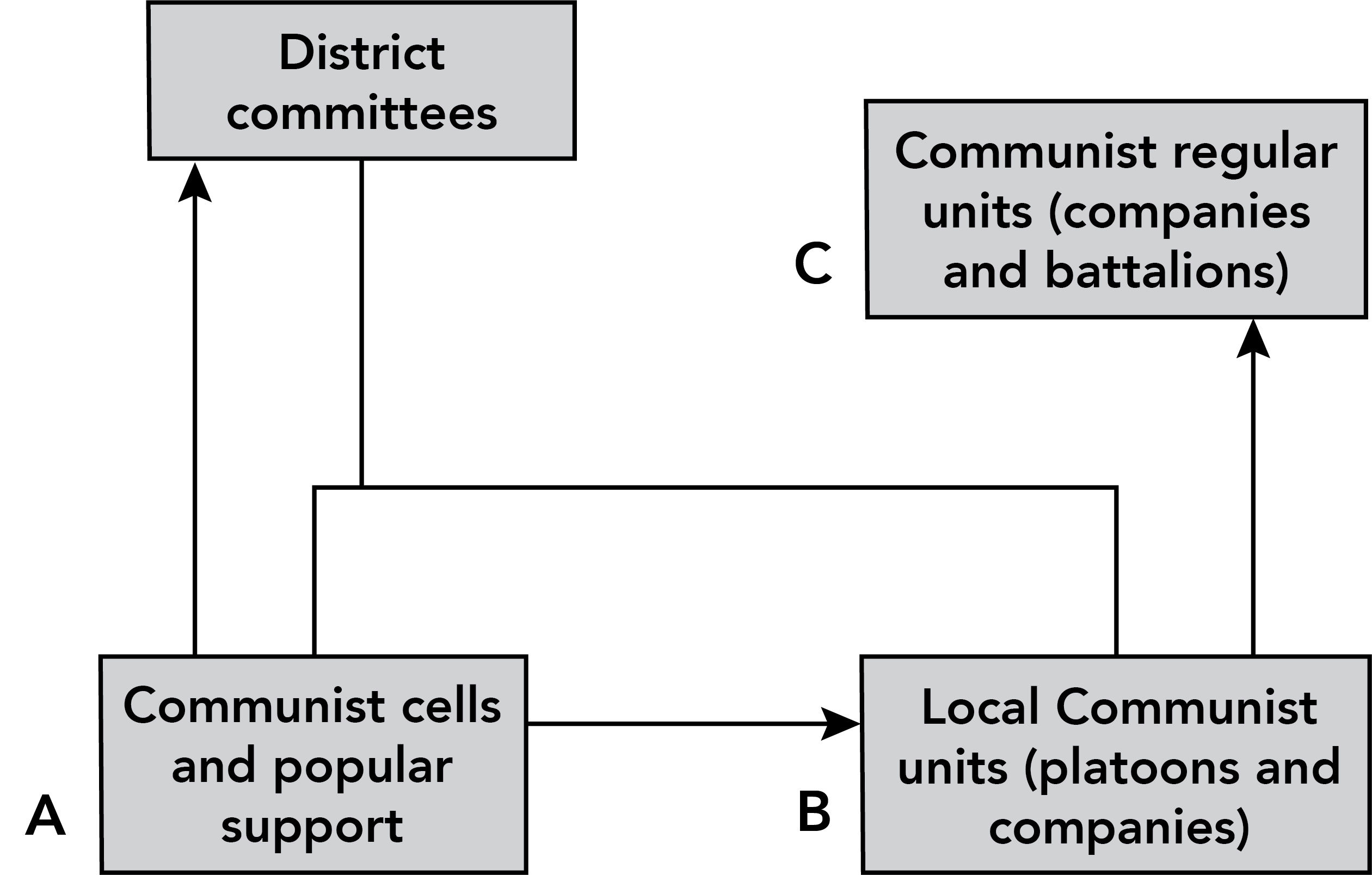

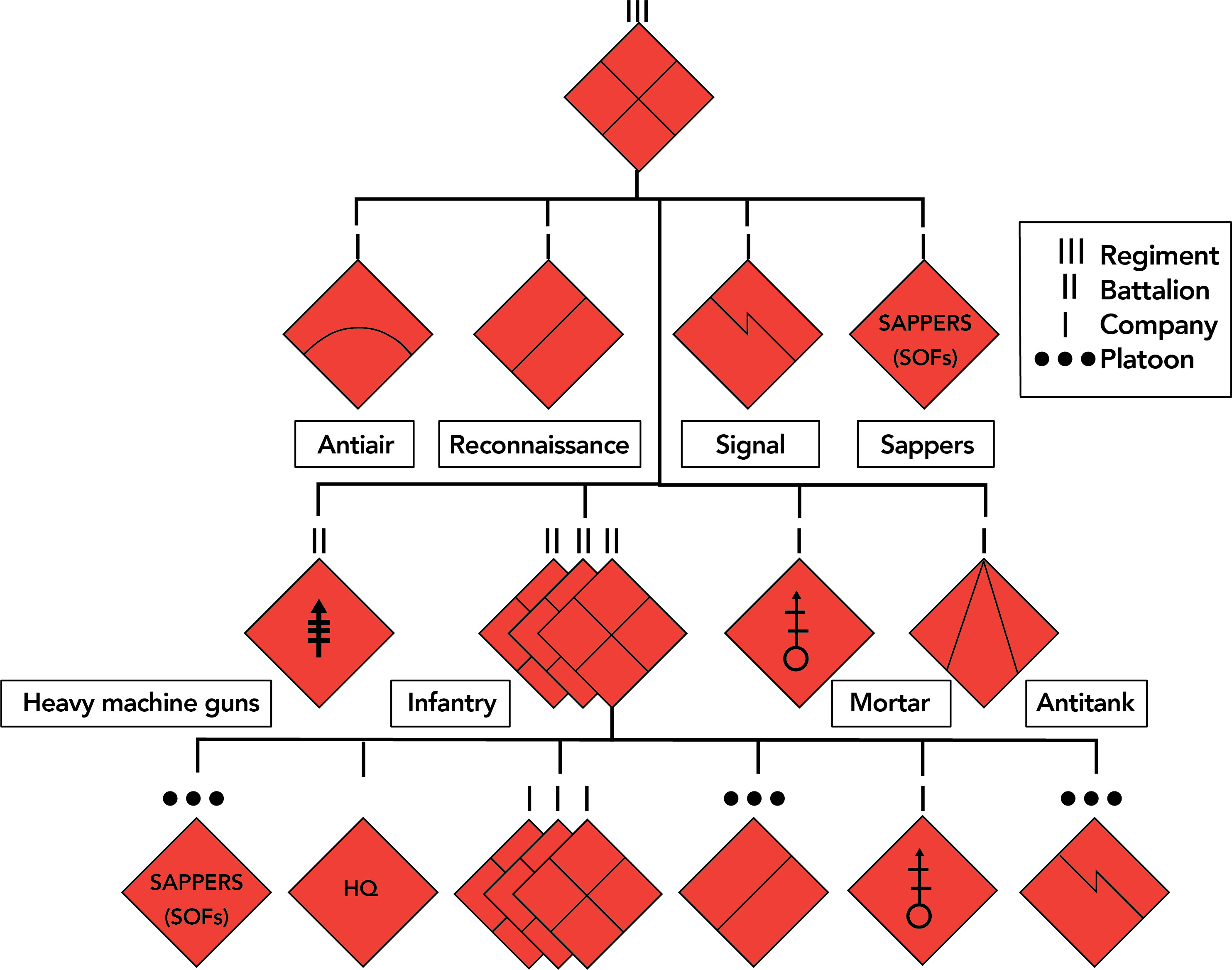

The Corps’ overall mission encompassed six objectives: 1) destroy the village’s Viet Cong political infrastructure; 2) protect residents and maintain public order; 3) protect village infrastructure and development; 4) defend the area and the lines of communication on the village’s perimeter; 5) organize an intelligence-gathering network among the civilian population; and 6) participate in civic actions and conduct psychological operations to turn the civilian population against the Viet Cong.25 Interestingly, these objectives were very similar to those promulgated by David Galula in his manifesto Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice.26 Krulak stated that by denying the insurgents access to the civilian population, the Viet Cong would lose its survival source, as guerrillas relied on civilians for food, recruits, and intelligence.27 Sir Robert Thompson, one of the masterminds behind the successful British counterguerrilla campaign in Malaya and a counterinsurgency advisor to presidents Ngo Dinh Diem and Richard M. Nixon, described in detail the Communist cadres’ modus operandi in the villages (figure 3). Under the local district committee’s leadership, the Communist political cadres (A) embedded with the population are responsible for increasing the insurgent group’s control over the villagers. Such control by the cadres is enforced with smaller or larger local fighting units (B and C). As they control the population, the political cadres (A) are responsible for providing food, logistics supplies, recruits, and intelligence to the district committee and combat units (B and C). The more the Communist cells geographically spread, the more the flow of recruits, logistics supplies, and combat-capable units increases. The ensuing chain reaction results in platoons rapidly growing into companies. If the process is unopposed, these companies will morph into battalions that will grow into a whole combat regiment (figure 4).28

Figure 3. The Communist political cadres’ links with Viet Cong fighters and villagers

Courtesy of Ismaël Fournier, based on a chart in Robert Thompson, Defeating Communist Insurgency (1966), 30.

Figure 4. Order of battle of a Viet Cong (and NVA) regiment and battalion

Courtesy of Ismaël Fournier, based on the orders of battle described in J. W. McCoy, Secrets of the Viet Cong (1992), 37.

Thompson explained that most military commanders instinctively focus their targeting operations on units B and C given that militarily, they are the most attractive targets. Such a decision results in “large scale military operations” based on flawed intelligence, according to Thompson, which usually allows the guerrillas to avoid contact with the enemy. Should the insurgents be caught in the open and sustain heavy casualties, any loss suffered by units B and C will be replaced by the political cadres who will promote B members to the C category. The cadres will then recruit new fighters among the population under their control to refill unit B ranks.29 In many ways, this was the crucial mistake USMACV committed in the populated areas of South Vietnam between 1965 and 1968. The U.S. Army’s leadership was obsessed with units B and C while neglecting the political cadres (A) that allowed the insurgency to thrive and remain operational. This explains why U.S. troops constantly had to secure the same area on multiple occasions. Targeting the fighting units was justified but useless if the insurgency’s political arm was not incapacitated in the villages. The Marine Corps’ CAP initiative was designed to avoid falling into such a trap. Marines’ actions in the villages denied the cadres the ability to support the fighting units by obstructing their access to the population. Communist cadres were rapidly compromised, and Viet Cong units were regularly targeted and ambushed by the Marines and Popular Force. Once they felt genuinely safe, villagers provided intelligence to the Americans on Viet Cong movements, ambush preparations, and booby traps, which facilitated Marine ambush operations and force protection.30 The situation became precarious enough for one captured Viet Cong cadre to admit that the Marines had constrained their troops to focus their operations on non-CAP villages.31 However, the threat posed by the regular NVA battalions near the DMZ forced thousands of Marines toward the northern border, which limited the expansion of the program.

Although the CAP system proved effective in a guerrilla war context, the situation became quite different once conventional military forces came into action, especially during the Tet offensive in 1968. One of the prime targets of Communist troops in I Corps during the Tet campaign was none other than the CAPs. Several Marine villages were overrun by entire NVA and Viet Cong battalions, necessitating the urgent deployment of conventional forces to assist the counterinsurgents.32 Had Vietnam been a war theater similar to the Malayan insurgency of the 1950s for the British, attacks of such magnitude against CAP villages would have been unlikely. However, given the hybrid nature of the Vietnam War, such a scenario remained a constant sword of Damocles hanging over the head of every counterinsurgent. The South Vietnamese went through the same ordeal in 1964 when Westmoreland convinced ARVN commanders to divide their forces into small detachments to ensure the protection of Binh Dinh Province’s villages. While the initiative did increase the government’s control of the population, the Communists acted rapidly to curtail the plan. The Viet Cong deployed combat battalions that attacked and retook control of every village. South Vietnamese detachments were overwhelmed and routed by the Communists.33 Small platoon units conducting counterinsurgency are not suited to confront heavily armed battalions supported by artillery and mortar fire. While such attacks by regular forces against CAP villages mainly occurred during the Tet offensive, it remained an indicator of the program’s vulnerability should it be deprived of rapidly deployable conventional forces to support its counterinsurgents.

Additionally, another problem associated with CAP eventually emerged: the program’s overreliance on the Marines and their assets. An introspective report from the Marine Corps assessed that the Popular Force remained dependent on the Marines despite the training and mentoring provided by the Americans. Casualty analysis shows that the Marines carried the bulk of combat activities on their shoulders inside the CAPs. Overall, the Corps’ losses were 2.4 times greater than those suffered by the Popular Force.34 Furthermore, the fighting that involved the Popular Force during the Tet offensive showed the Americans that paramilitary forces, supported by their resources alone, could not ensure CAP’s survival.35 The situation exposed an apparent flaw in the program’s execution: Americans were the CAP initiative’s main protagonists. While the Marines’ role was central, the program’s main objective was to create the conditions for “an orderly phase-out” of the Americans once the Popular Force improved sufficiently to take over the mission by themselves.36 Thompson emphasized that foreign agencies must “resist the temptation to take over” the host nation actors’ function, thinking they will do a better job. Doing so would result in the failing of the foreign force’s main task: build up the local government’s administrative machinery and the experience of the individuals meant to take over the campaign.37

Should the Marines have been more in the background rather than directly involved with the Popular Force in CAP, the program would probably have been through additional setbacks in the short term. However, it would have pushed the South Vietnamese to be self-reliant and less dependent on their Marine counterparts. The system worked admirably in Malaya, where the British trained hundreds of thousands of local Home Guard soldiers who were the leading counterinsurgents in the field. They were supervised and led by British and Australian officers.38 The CORDS initiative was better adapted than CAP for Vietnam. Aside from special forces assigned to the Phoenix Program, most U.S. personnel and advisors attached to CORDS were in the background and seldom directly participated in combat activities alongside South Vietnamese paramilitary forces.39 They limited their involvement to supervision, mentorship, general support, and intelligence sharing and exploitation.

Birth of the Office of CORDS: Original Obstacles and Setbacks

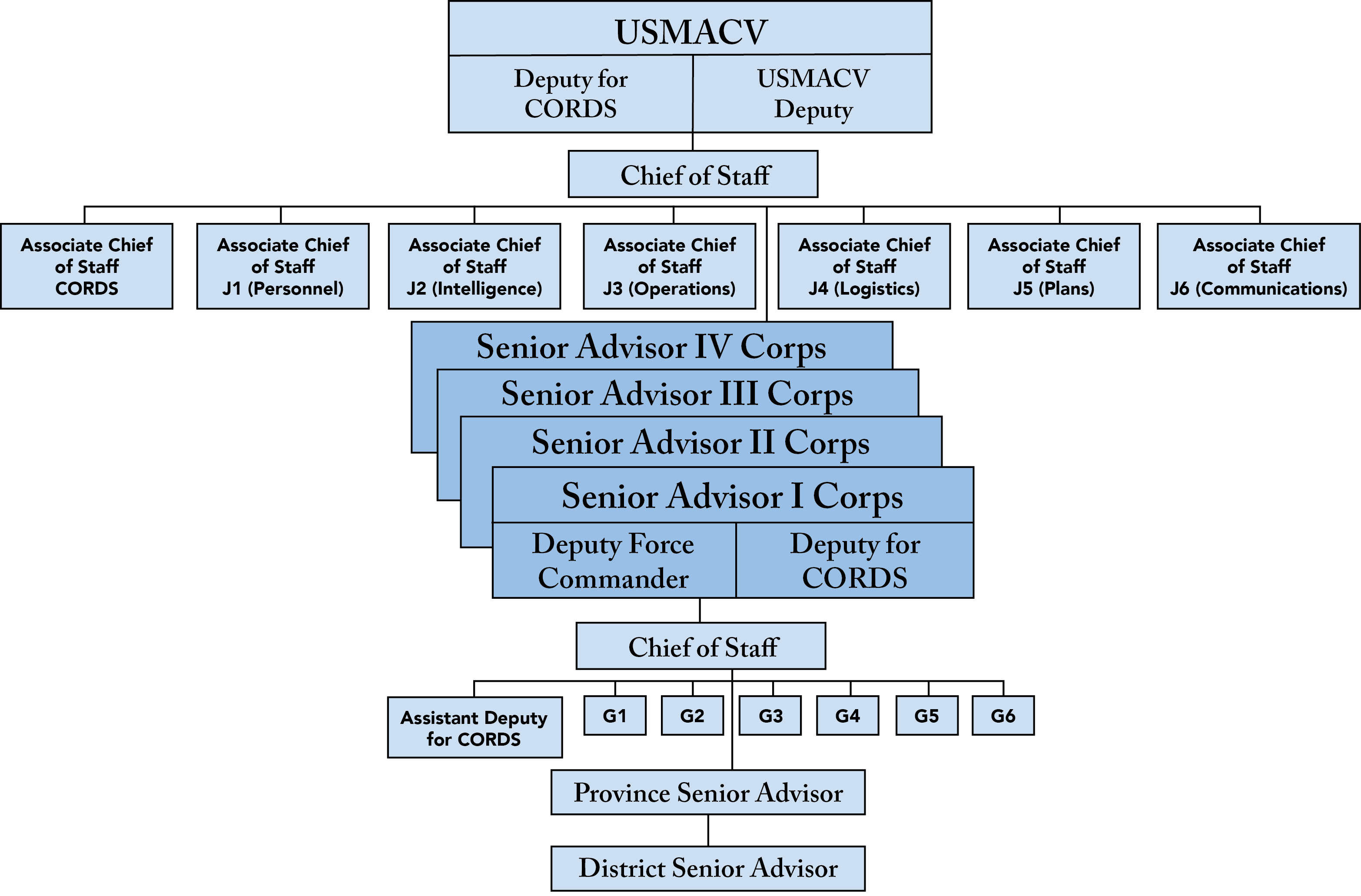

The Office of CORDS was officially launched in May 1967 and put under the responsibility of USMACV. Robert W. Komer, a civilian member of the intelligence community who had no superior other than Westmoreland, was put in charge of the project. Komer was at the head of a program that brought under a single umbrella every military and civilian organization charged with carrying out pacification in South Vietnam. The program had offices in all the country’s provinces and districts (figure 5). The concept was similar to what British field marshal Gerald Templer conceptualized when he managed the war effort against the Communist insurgency in Malaya. Former CORDS advisor Stephen B. Young describes the program as follows: [A] joint venture among the United States military, American civilian agencies, South Vietnamese government, South Vietnamese elected political officials in villages, provinces and in Saigon, and South Vietnamese citizens in villages, religious organisations, businesses, and social networks.40

Figure 5. Organization and structure of CORDS

Courtesy of Ismaël Fournier, based on a chart in USMACV Office of CORDS Pacification Studies Group, General Records US Weekly Returnexe Reports 1969 thru Plans/1970/Supplements, Phases Etc. 1970, box 7, Records of the U.S. Forces in Southeast Asia/Headquarters, NND 45603, RG 472, NARA.

CORDS managed to attain the “middle ground” between the exploitation of “hard power” and “soft power.” That middle ground was embodied by what Young calls “associative power.”41 The program used hard power to protect the villages and disrupt the Viet Cong’s infrastructure, economic power to support civic actions, and political power to conduct elections. Soft powers focused on the cultural outreach of the Viet Cong and the gathering of intelligence on insurgents who operated in the villages.42 Young stated that a “good counterinsurgency [campaign] builds partnerships with local communities and their leaders.” These partnerships will thrive to become “local institutions of self-government, self-defense, and self-development.”43 CORDS aimed to achieve these objectives with host nation officials and security forces as the project’s main protagonists. U.S. advisors would be dispatched to advise the South Vietnamese administrators and cadres of the Revolutionary Development (RD) group charged with the supervision of pacification efforts. While the plan seemed fine on paper, CORDS’s first 15 months of operations did not go smoothly. The events that unfolded in the Cu Chi District epitomize the overall problems encountered when CORDS became operational. Given the large geographical area that came under CORDS’s responsibility, it would be impossible to outline all the problems encountered by the program’s staff in each district. However, following the analysis of hundreds of pages of CORDS reports, Cu Chi provides an excellent example of what happened in most of the South Vietnamese areas during the first 15 months of the program. Two central problems plagued CORDS: the lack of discipline of several of its members and the threat posed by larger Viet Cong units.

While a whole paper could be written on the discipline problems related to CORDS when Komer launched the program, this article focuses on the threat posed by the large guerrilla formations. Hybrid warfare implicates more than dealing with small insurgent units. CORDS counterinsurgents would unavoidably be targeted by fully armed regular Viet Cong battalions and possibly by the NVA, a fact that Komer anticipated in the early stages of the program’s development. In 1967, he participated in a veritable bureaucratic struggle to force military planners to better coordinate their efforts to properly support the paramilitary forces and government cadres deployed in rural South Vietnam.44 Earlier in 1966, during the Manila Conference, President Lyndon B. Johnson and his South Vietnamese counterpart Nguyen Van Thieu agreed that ARVN forces should shift the bulk of their efforts to support pacification.45 Some U.S. and ARVN battalions assigned to assist the counterinsurgents managed to keep large Viet Cong units at bay. However, it was not so in every district. Before the deployment of the U.S. Army’s 25th Infantry Division to Cu Chi in 1966, 10,769 insurgents dominated the district.46 The 7th Viet Cong Battalion and local guerrilla units carried out combat operations with impunity until the division’s arrival. The Americans established a base of operations and initiated a succession of search-and-destroy offensives, forcing large Viet Cong formations to take refuge in isolated areas. These conventional military operations alleviated the pressure put on paramilitary forces, who could now focus their attention on local guerrillas and political cadres in the villages.47 However, when the U.S. division left the district, not a single unit remained behind. The Viet Cong influence regained its momentum, pushing the paramilitary forces back on the defensive. The problem was widespread in much of South Vietnam.

Many end-of-tour reports written by U.S. advisors and CORDS briefings to the White House bemoaned the absence of proper support for the paramilitary forces. They simply could not perform their duty with large enemy formations on their backs. Even the North Vietnamese military acknowledged U.S. conventional forces’ disturbing effects when they supported the counterinsurgents. A captured report belonging to the 95th NVA Regiment specified that the Communists, who controlled 260,000 civilians out of 360,000 in the Phu Yen area at the end of 1965, only controlled 20,000 in May 1967. The NVA attributed this situation to the synchronization of USMACV’s conventional and counterinsurgency operations in the area.48 The NVA also reported that the coordination between Communist regular and insurgent troops was dysfunctional. The relationship between guerrilla war and regular mobile warfare was not properly exploited, which disrupted the insurgents’ ability to properly execute their mission in the villages.49 In such a hybrid warfare scenario, all sides (U.S. forces, ARVN, and Communists) had to synch their conventional and nonconventional military unit operations if they hoped to increase their prospect for victory. When the 25th Infantry Division left Cu Chi without leaving a single battalion to support the paramilitary forces, the Viet Cong’s reemergence was unavoidable. In the heart of the villages, RD cadres that would usually dismantle the insurgency’s political infrastructure were too frightened to operate in the district’s hamlets proactively.50 No elections occurred in the villages controlled by the Viet Cong. Although elections were held in the disputed village of Trun Lap, none of the elected officials were bold enough to spend the night in their hamlet. Fear only increased the lack of discipline, ethics, and commitment observed among many RD cadres. However, a key event was on the verge of shifting the battle’s momentum in favor of CORDS. The Tet offensive and its aftermath allowed Komer to enforce some changes, which enabled the counterinsurgents to reassert the government’s control of the countryside.

CORDS’s Revival after Tet and the Viet Cong’s Road to Defeat

Half of the 84,000 Communists deployed during the Tet offensive were killed in action or captured following the campaign. Furthermore, subsequent spring offensives dubbed “mini-Tet” inflicted more heavy casualties on the Viet Cong. Communist losses amounted to 240,000 killed and wounded in 1968, which included many political cadres who were exposed and neutralized during the fighting.51 These devastating losses created a huge political and control vacuum in South Vietnam’s villages. To take advantage of the situation, the Accelerated Pacification Campaign (APC), an expansion of the CORDS program, was launched in November 1968. The initiative was first proposed by Komer and his deputy, William E. Colby, who would become Komer’s successor as the head of CORDS. They both understood that to gain the initiative and negate the Viet Cong’s political influence, government officials had to take the offensive and retake the legitimate control of the contested areas. Colby also stressed the importance of dispatching conventional forces to assist the counterinsurgents in the eventuality of the deployment of large Communist formations.52

Colby presented a four-phase plan to General Creighton W. Abrams, Westmoreland’s successor as the head of USMACV. The first phase aimed at dispatching conventional units to push away the enemy’s large battalions from populated areas. The second phase intended to deploy paramilitary forces and government officials in areas still under threat of guerrillas. Phase three aimed at strengthening the populated centers and lines of communications. Finally, the fourth phase sought to oppose the “Communist dictatorship” by launching elections in the villages, according to Young.53 Following Colby’s briefing, Abrams gave his full approval and support to the initiative, which was also approved by President Thieu.54 The latter took the APC very seriously and regularly inspected the villages with his prime minister to assess the program’s progress. Colby noted that the neglect observed in the previous year was, by the end of 1968, a thing of the past; South Vietnamese officials realized that Thieu was serious about enforcing the APC. Henceforth, there would be accountability to the president if there was a lack of rigor in implementing the program. Colby submitted reports from his American subordinates to Thieu or cabinet members, who would bring to order leaders who were not implementing the program as directed.55 Changes were also implemented among the regular military units. Under General Abrams’s leadership, USMACV’s focus would not be on firepower but instead on Vietnamization—which aimed at progressively letting the ARVN take over the lead in the war—and small unit operations. Abrams set in motion a battle plan in which conventional forces would track down and eliminate large Communist formations; at the same time, small unit operations, including patrols and ambushes against Viet Cong guerrilla units, would be initiated.56 Unfortunate cases such as that of General Julian J. Ewell, an officer who disregarded counterinsurgency and maximized firepower in two provinces of the Mekong Delta, did not exemplify how USMACV managed the war from 1969.

Abrams was a staunch defender of counterguerrilla warfare and believed in combining conventional war and counterinsurgency in Vietnam’s hybrid context. There are many debates on Abrams’s actual influence on the U.S. military strategy in Vietnam. Lewis Sorley claims that Abrams adapted the military’s battle plan to such an extent that the United States was on the verge of winning the war on the battlefield.57 On the other hand, Gregory Daddis states that Abrams’s approach was more a continuity than an actual change in strategy.58 Analysis of U.S. military operations from 1969 indicates that much more focus and seriousness were put on counterinsurgency under Abrams. For instance, in 1969, the U.S. Army’s 173d Airborne Brigade launched a counterinsurgency campaign in Binh Dinh that was an exact replica of the Corps’ CAP.59 In Quang Ngai, U.S. Army units launched the Infantry Company Intensive Pacification Program, another copy of the CAP.60 While it remains speculative, it is unlikely that Westmoreland would have gone so far as to allow a whole U.S. infantry brigade to emulate the Corps’ CAP system. Back on the battlefield, a large new Viet Cong offensive launched during the 1969 Tet holiday resulted in such catastrophic losses that COSVN leaders issued an order that put an end to conventional military offensives. Guerrillas were instructed to redirect their focus to subversive operations as in the insurgency’s first days.61 However, as in the previous Tet offensive of 1968, the insurgents’ losses during the fighting galvanized CORDS’s momentum. Communist conventional forces could no longer afford to assist the guerrilla cadres and fighters in the villages. As with the CAP, South Vietnamese paramilitary forces and RD cadres choked the guerrillas in the vicinity of the villages.

In the summer of 1969, security around the Mekong Delta was improved to such an extent that it was possible to travel unescorted during daytime from one provincial capital to another. Each hamlet now benefited from the protection of a platoon of paramilitary forces assisted by village militias.62 Across the whole country, control of Communist cadres over the rural population collapsed to 12.3 percent, then to 3 percent. Villagers cultivated 5.1 million metric tons of rice without the Viet Cong being able to benefit from it. About 47,000 Communist soldiers and cadres joined the South Vietnamese ranks through CORDS’s Chieu Hoi defector program. In 1967, 400,000 civilians were forced to leave their villages due to combat operations. In 1969, the number of refugees fell to 114,000 for the entire country.63 During that same year, another counterinsurgency initiative was attached to CORDS. The Central Intelligence Agency’s (CIA) Phoenix Program, initially launched in 1967, was now under CORDS’s responsibility. For decades, Phoenix had a poor reputation as it was frequently labeled a torture and assassination program. The analysis of this long-lasting controversy is beyond the scope of this study. Authors like Mark Moyar and Phoenix veteran Lieutenant Colonel John L. Cook both set the record straight regarding Phoenix.64 Targeting an insurgency’s political infrastructure is a crucial aspect of counterguerrilla warfare. It also was one of David Galula’s central tenets.

Phoenix’s primary objective was to eliminate the Viet Cong Infrastructure (VCI). Members of the VCI embodied the political arm of the insurgency. They were supported by security forces that ensured their protection, cadres in charge of finances and taxation, and other members whose mandate consisted of ensuring the civilian population’s management and control.65 Phoenix’s operational control within the districts and provinces was formally vested in their respective chiefs. Tactical management of the program fell under American and South Vietnamese intelligence officers (S2). This responsibility was shared by the District Intelligence and Operations Coordinating Center (DIOCC).66 The DIOCC’s primary function was to collect relevant intelligence that could be used to plan operations against the Communist cadres at work in the districts’ villages. The task of neutralizing VCI members in the field fell to U.S. special forces operators, South Vietnamese special forces of the Provincial Reconnaissance Unit (PRU), government officials, RD cadres, and paramilitary forces. Human intelligence remained Phoenix’s key asset. By recruiting multiple informants in villages and through information collected from numerous Viet Cong defectors and prisoners of war, Phoenix operators caused severe damage to an already weakened insurgency. Back in 1967, according to USMACV estimates, about 80,000 Communist cadres were operating in areas still under Viet Cong influence.67 In the first 11 months of 1968, U.S. reports claim that Phoenix neutralized 13,404 cadres. In Quang Tri Province, PRU actions caused such damage to the VCI that the Communists deployed a special commando unit specifically trained to destroy a PRU operating base.68

A COSVN report complained about the significant damage inflicted on them by the PRUs and the Chieu Hoi defector program.69 The COSVN admitted that VCI defection increased by 49 percent in the second half of 1968. Communist reports also indicated that a significant number of cadres were unable to operate freely or enter their area of responsibility, even after dark. Phoenix’s attrition rate on VCI members forced the COSVN to deploy new, young, inexperienced cadres, totally lacking their predecessors’ expertise. A single cadre was assigned responsibilities normally allotted to two or three of their peers in several cases.70 In 1969, USMACV assessed that 19,534 more cadres were neutralized due to Phoenix.71 Although Phoenix figures are known not to be 100 percent accurate (many Viet Cong fighters were mistakenly designated as VCI), the attrition caused to VCI was reflected in COSVN reports, the drastic drop in insurgent recruitment activities, and the testimony of Communist defectors. A VCI deserter admitted that the Viet Cong feared Phoenix, which was trying to “destroy its organizations” and denied its cadres access to the civilian population.72 He also stated that insurgents who did not have to deal with villagers received very specific instructions: contacts with the population were prohibited due to Phoenix agents’ overwhelming presence in rural areas. The defector also said that Viet Cong commanders warned their subordinates that Phoenix was “a very dangerous organization” of the South Vietnamese pacification program.73 Another Communist report complained about Phoenix agents’ ability to target cadres, noting that the program’s members were “the most dangerous enemies of the Revolution.”74

The same report insists that no organization other than Phoenix could cause the Communist struggle so many problems and difficulties. North Vietnam’s leader, Ho Chi Minh, admitted that he was much more worried about the U.S. military successes against the VCI than those obtained against his regular forces.75 When peace talks began between Washington and Hanoi in Paris, Communist officials demanded the cessation of all operations related to the Phoenix Program.76 While Phoenix was indeed dreaded by the insurgents, the program’s successes were far from instantaneous. Much like CORDS at its inception, Phoenix was plagued by discipline problems. Furthermore, Phoenix and regular military forces’ intelligence analysts seldom shared intelligence, which was counterproductive for both entities. However, as with CORDS, the program drastically improved after Tet. The change was mainly due to William Colby, who refocused the program’s priorities. Henceforth, Phoenix would have offices in the country’s 244 districts, with every single intelligence and security agency present to support the program against the VCI. Phoenix administrators would send a corps of specially trained U.S. advisors to each of these offices to work with the South Vietnamese.77 Moreover, several regular unit commanders sent their S2 (intelligence) and S3 (operations) officers to meet with CORDS advisors. These meetings aimed to provide regular units with the latest intelligence reports and encourage cooperation from CORDS/Phoenix agencies and tactical units.78

In II Corps, the G2 established a branch specifically dedicated to collecting and analyzing intelligence related to the VCI.79 In I Corps, the intelligence gathered by CAP Marines greatly supported Phoenix’s efforts against the VCI. Concurrently, Marines requested Phoenix’s blacklists (VCI suspects) as well as situation reports on weapons caches and Viet Cong activities to support their operations.80 In 1970, Colonel James B. Egger, the U.S. Army coordinator assigned to Phoenix in III Corps, stated that cooperation between the combat units and Phoenix was “outstanding.”81 Such cooperation supported both counterinsurgents and conventional forces in Vietnam. As regular units worked hand in hand with their counterinsurgent counterparts, they severely disrupted the guerrillas’ attempts to regain control of rural South Vietnam. In July 1969, the COSVN published Resolution 9 for its members to counter the adverse effects of USMACV and Saigon’s counterinsurgency campaign. The resolution ordered guerrilla forces to focus their targeting operations on pacification personnel in rural areas. A few months later, confronted with its subordinates’ inability to follow the directives of Resolution 9, the COSVN published Resolution 14, which insisted again on the need to revert to a guerrilla warfare concept to overcome the enemy’s pacification program. It also criticized the slowness of guerrilla and local force movements and the low level of progress in regaining control of rural areas. Resolution 14 also denounced the party committee’s and military commanders’ failure to increase pressure on counterinsurgency forces and their inability to gain the civilian population’s support.82

Other seized documents exposed the Communists’ growing loss of rural area control. Viet Cong Party committee members in charge of the region surrounding Saigon claimed that “revolutionary forces” were under much pressure, a consequence of the loss of senior cadres in the districts, as well as the anemic population pool still accessible for recruitment. They also criticized Communist units’ inability to achieve a significant victory. The committee admitted that their forces were “poor in quality and quantity” and unable to establish contact with the population. Also mentioned was the incapacity of larger battalions to operate near populated areas and local guerrillas’ ineffectiveness in their attempts to convince the people to support their operations. Viet Cong leadership further stated that their units “continue[d] to suffer losses” and remained unable to renew their strength. Political groups aimed at indoctrinating civilians were labeled “weak,” small, and “incompetent.” The committee recognized the control exerted by government forces over the civilian population while criticizing its forces’ inability to reverse the situation.83 CORDS analysts observed that from 1968 to 1970, terrorist incidents related to Viet Cong activities continued to drop. The same was true for the number of civilians killed, injured, or abducted by guerrillas.84 William Colby explained that regular troops managed to drive large Communist formations away from rural areas, which supported the pacification program’s progress. At the beginning of 1970, CORDS achieved most pacification objectives, with 90 percent of the population living in hamlets enjoying “acceptable security” and 50 percent living in areas considered “completely secure.”85 During rural elections in 1970, 97 percent of populated areas could vote freely with no significant Viet Cong interference.86

In 1971, terrorist acts declined by 75 percent in more secure areas and 50 percent in areas classified as less secure.87 The inaccessibility to the people, defections, desertion rates, and the inability to operate freely in the countryside drastically hampered the Viet Cong’s ability to remain combat effective. Sir Robert Thompson, who was President Nixon’s counterinsurgency special advisor for Vietnam, indicated that in most of the insurgency’s areas of responsibility, 70–80 percent of the Viet Cong’s military forces was composed of regular NVA soldiers. Thompson stated that “Allied operations” had “almost completely eliminated” the Viet Cong’s military threat and that pacification efforts had “dried up their recruiting base” among the civilian population.88 Following one of his last inspection tours to Vietnam in 1971, Thompson forwarded a letter to the president’s national security advisor, Henry A. Kissinger. He wrote that “there is a great disparity between the situation in South Vietnam and what many in the U.S. believe it to be.” He added, “This is no longer a credibility gap but a comprehensibility gap.”89 The year 1972 marked the end of the Viet Cong as an effective guerrilla force. As stated by CORDS veteran Stephen Young:

A remarkable success in the development of associative power to defeat a powerful insurgency was achieved [with] the CORDS program. . . . Its success in defeating the Viet Cong insurgency was accomplished in the Spring of 1972.90

At this point of the war, Vietnam transitioned from a hybrid warfare theater to a conventional warfare battlefield. The North Vietnamese regular forces, far from being decimated like the Viet Cong, took charge of military operations and launched the spring offensive, a major multidivisional blitzkrieg campaign designed to destroy the ARVN and regain the initiative following U.S. combat forces’ departure from South Vietnam. The invasion failed when entire NVA battalions were mauled by Boeing B-52 Stratofortress bombers. As the NVA reorganized its forces, it prepared for the final offensive to invade South Vietnam. The once-powerful insurgency would assume no significant role in what was to bring about the fall of South Vietnam. In the spring of 1975, the NVA launched a new multidivisional campaign with new Soviet-supplied tanks and artillery. The ARVN was routed by the North Vietnamese military, which took Saigon on 29 April 1975.

Conclusion

When U.S. combat forces were deployed to South Vietnam in 1965, the country was on the verge of total collapse. In the first years of its combat involvement, USMACV acted instinctively as it tracked the large Communist battalions while it neglected to target the insurgency’s shadow government. Until the end of 1968, conventional forces paid little attention to the counterinsurgents who struggled to accomplish their tasks when confronted with fully armed Communist battalions. For many orthodox historians, the way the U.S. military waged war between 1965 and 1968 is the norm by which they assess the overall military performance of the United States in Vietnam. While they timidly acknowledge the efforts of pacification initiatives and USMACV’s switch to small unit operations, they mostly ignore how USMACV genuinely morphed its strategy to sync its intelligence and combat operations with the efforts of U.S. and South Vietnamese counterinsurgents. As for CORDS, its major operational impact on the battlefield against the Viet Cong insurgency is outrageously marginalized.

The hybrid war in Vietnam was the consequence of Hanoi’s strategy, which exploited both conventional and unconventional warfare tactics, requiring a symmetrical U.S. military response. Such a course of action requires time to perfect, especially for a military force bred to fight against Soviet divisions. Vietnam was definitively a new form of war for the Americans and mistakes were unavoidable. Although it took several years of adjustments coupled with multiple setbacks, U.S. and South Vietnamese forces undeniably defeated the Viet Cong insurgency in 1972. USMACV managed to balance its approach to hybrid warfare by creating a joint military and civilian pacification program mainly implemented by the South Vietnamese and supervised by U.S. advisors. Like CAP, the office of CORDS targeted the Communist cadre system Thompson described. Counterinsurgents denied the insurgents’ ability to rely on their cadres, who struggled to operate in their designated areas of operations. This situation required the intervention of large Communist battalions, a course of action the 95th NVA Regiment also urged. Without the support of regular units to engage the large Viet Cong battalions with conventional military doctrines, regaining control of the countryside would have been impossible for CORDS. The same can be said had U.S. forces ignored the large NVA divisions that roamed the Central Highlands and border areas of the DMZ, Laos, and Cambodia. When the guerrillas’ struggle was compounded by the massive losses their regular battalions sustained in 1968 and 1969, they failed in their attempt to rebuild the insurgency by reverting their efforts to subversive activities, an art they excelled at in the previous decades. Consultation of multiple Communist reports written between 1968 and 1971 exposes the COSVN’s obsession with the South Vietnamese pacification campaign, which is repeatedly labeled as the strategic target of the insurgency.

If the Communists had avoided their costly offensives in 1969, they would have been in a much better position to execute subversive operations supported by guerrilla fighting forces. However, the Viet Cong’s losses against conventional military forces ruined the COSVN’s prospect for success. U.S. regular units shielded the counterinsurgents from the remainder of the insurgency’s battalions, leaving the guerrillas to fend for themselves. At this point, Viet Cong leadership acknowledged that it was incapable of regaining the initiative against the counterinsurgents and admitted that government forces had the upper hand. In retrospect, the South Vietnamese success with CORDS should not come as a surprise. Under South Vietnam’s president, Ngo Dinh Diem, the Viet Cong lost the initiative when ARVN and paramilitary forces moved parts of the rural population into reinforced villages called strategic hamlets. The concept was similar to the British doctrine in Malaya and the CAP concept. Not unlike CORDS, the initiative struggled heavily at its debut. However, with the mentorship of CIA officer Edward G. Lansdale and a British advisory mission led by Thompson, the program was drastically improved. In 1963, it gave the upper hand to the South Vietnamese, a fact later acknowledged by Communist sources.91 The program fell apart when Diem was assassinated following a military coup tacitly approved by the Americans, a move that even Ho Chi Minh could scarcely believe and described as “stupid.”92 Unlike Diem’s strategic hamlet campaign, CORDS was allowed to stay the course, and it ultimately achieved its objectives against the insurgency. Following CORDS’s success in 1972, the Viet Cong was no longer an indigenous organization. It was filled with North Vietnamese soldiers who may have excelled at conventional warfare but failed as guerrilla fighters. The U.S. and South Vietnamese managed to incapacitate one of Hanoi’s hybrid warfare organs when it defeated the insurgency. However, given the South Vietnamese Army’s poor state in 1975, the prospect of an ARVN victory against fully trained and supplied NVA divisions was hopeless. In the end, with the insurgency’s demise, any hope of achieving a military victory was contingent on one’s ability to defeat their opponent on the conventional battlefield.

•1775•

Endnotes

- John A. Nagl, Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife: Counterinsurgency Lessons from Malaya and Vietnam (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2002), xxii.

- Andrew F. Krepinevich Jr., The Army and Vietnam (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986), 37.

- Lewis Sorley, Westmoreland: The General Who Lost Vietnam (New York: Mariner Books, 2012), 107.

- Max Boot, Invisible Armies: An Epic History of Guerrilla Warfare from Ancient Times to the Present (New York: Liveright, 2013), 421, 425.

- Douglas Porch, Counterinsurgency: Exposing the Myths of the New Way of War (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 209–10.

- Williamson Murray and Peter R. Mansoor, eds., Hybrid Warfare: Fighting Complex Opponents from the Ancient World to the Present (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 2.

- Ofer Fridman, Russian Hybrid Warfare: Resurgence and Politicisation (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), 19.

- Fridman, Russian Hybrid Warfare, 24–26.

- Fridman, Russian Hybrid Warfare, 26.

- Fred Kaplan, The Insurgents: David Petraeus and the Plot to Change the American Way of War (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2013), 27.

- Porch, Counterinsurgency, 207.

- Lien-Hang T. Nguyen, Hanoi’s War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012), 49, 53, 72.

- Truong Nhu Tang, A Viet Cong Memoir (New York: Vintage Books, 1986), 68.

- Background and Draft Materials for U.S. Marines in Vietnam: The Defining Year, 1968, box 5, Records of the Headquarters Marine Corps History and Museums Division, Record Group (RG) 127, entry A-1 (1085), National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), College Park, MD, hereafter Background and Draft Materials for U.S. Marines in Vietnam: The Defining Year, 1968.

- Sorley, Westmoreland, 103–4.

- Gregory Daddis, Westmoreland’s War: Reassessing American Strategy in Vietnam (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2014), xx.

- Gregory Daddis, No Sure Victory, Measuring U.S. Army Effectiveness and Progress in the Vietnam War (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 69.

- Gregor Matthias, David Galula (Paris: Economica, 2012), 1.

- Matthias, David Galula, 173.

- “Directive Number 525-4 Tactics and Techniques for Employment of U.S. Forces in the Republic of Vietnam,” History File #1, 29 August–24 October 65, box 26, NND 596559, Records of the Army Staff 1903–2009, RG 319, entry UD #1143, Papers of William C. Westmoreland, NARA, 1–7.

- Douglas Pike, Viet Cong: The Organization and Technique of the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1967 [1966]), 238.

- Michael Lee Lanning and Dan Cragg, Inside the VC and the NVA: The Real Story of North Vietnam’s Armed Forces (New York: Ivy Books, 1992), 158–61, 163.

- Guenter Lewy, America in Vietnam (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1978), 52.

- Background and Draft Material for U.S. Marines in Vietnam, box 23, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps 1775–, RG 127, entry A-1 (1085), NARA, 1.

- William R. Corson, The Betrayal (New York: W. W. Norton, 1968), 184.

- David Galula, Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice (Westport, CT: Praeger, 1964).

- Corson, The Betrayal, 184.

- Sir Robert Thompson, Defeating Communist Insurgency: Experiences from Malaya and Vietnam (London: Chatto and Windus, 1966), 30–31.

- Thompson, Defeating Communist Insurgency, 31.

- Modification to the III MAF Combined Action Program in the RVN, 19 December 1968, box 119, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps 1775–, RG 127, NND 9841145, NARA, C-9–C-10.

- III MAF, Marine Combined Action Program in Vietnam by LtCol W. R. Corson, USMC, box 152, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps 1775–, RG 127, NND 984145, NARA, 186, hereafter Marine Combined Action Program in Vietnam by Lt Col W. R. Corson, USMC.

- Marine Combined Action Program in Vietnam by LtCol W. R. Corson, USMC, 23.

- Mark Moyar, A Question of Command: Counterinsurgency from the Civil War to Iraq (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009), 153.

- Background and Draft Materials for U.S. Marines in Vietnam: The Defining Year, 1968, 13–14.

- Marine Combined Action Program in Vietnam by LtCol W. R. Corson, USMC, 24.

- Background and Draft Materials for U.S. Marines in Vietnam: The Defining Year, 1968, 14.

- Thompson, Defeating Communist Insurgency, 161.

- Nagl, Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife, 100.

- The controversial Phoenix Program, sponsored by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, aimed to identify, undermine, and dismantle the Communist insurgency in Vietnam. For more, see pg 78.

- Stephen B. Young, The Theory and Practice of Associative Power: CORDS in the Villages of Vietnam, 1967–1972 (Lanham, MD: Hamilton Books, 2017), 19.

- Young, The Theory and Practice of Associative Power, 12.

- Young, The Theory and Practice of Associative Power, 19.

- Young, The Theory and Practice of Associative Power, 19.

- Young, The Theory and Practice of Associative Power, 128.

- “Evolution of the War. Direct Action: The Johnson Commitments, 1964–1968. 8. Re-emphasis on Pacification, 1965–1967,” ID 5890510, Pentagon Papers, Part IV.C.8, container ID 6, NARA, 116.

- USMACV Office of CORDS Pacification Studies Group, General Records 1601-04 USAID/CORD Spring Review PSG 64/70 1970 thru 1601-10A Various Province Briefs 1970 Evaluation Report a Study of Pacification and Security in Cu Chi District, Hau Nghia Province, box 8, Records of the U.S. Forces in Southeast Asia/Headquarters, 1950–1975, NND 994025, RG 472, NARA, 1–2, 10–11, hereafter A Study of Pacification and Security in Cu Chi District.

- A Study of Pacification and Security in Cu Chi District, 1–2, 10–11.

- “Problems of a North Vietnamese Regiment,” docs. 2–3, Vietnam Documents and Research Notes Series: Translation and Analysis of Significant Viet Cong/North Vietnamese Documents, October 1967, microfilm, reel 1, frame 0131, 26. ProQuest folder 003233-001-0131.

- “Problems of a North Vietnamese Regiment,” 4.

- A Study of Pacification and Security in Cu Chi District, 4.

- Young, The Theory and Practice of Associative Power, 132.

- William Colby with James McCargar, Lost Victory: A Firsthand Account of America’s Sixteen-Year Involvement in Vietnam (Chicago, IL: Contemporary Books, 1989), 253–55.

- Young, The Theory and Practice of Associative Power, 132–33.

- Young, The Theory and Practice of Associative Power, 132–33.

- Colby and McCargar, Lost Victory, 261–62.

- Lewis Sorley, Vietnam Chronicles: The Abrams Tapes, 1968–1972 (Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press, 2004), xix.

- Gregory A. Daddis, Withdrawal: Reassessing America’s Final Years in Vietnam (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), xi.

- Daddis, Withdrawal, xii.

- USMACV Office of CORDS, MR 1 Phuong Hoang Division, General Records 204-57: Quang Nam Correspondence 1969 thru 204-57: Rifle Shot Operations 1969, 173d Airborne Brigade Participating in Pacification in Northern Binh Dinh Province, box 5, Records of the U.S. Forces in South East Asia, 1950–1975, NND 974305, RG 472, entry 33104, NARA, 1–3.

- USMACV Office of CORDS, MR 1, Phuong Hoang Division, General Records 205-57: Neutralization Correspondence 1969 thru 205-57: Overview Files 1969, Memorandum I Corps Field Overview (RCS-MACCORDS-32.01) for October 1969, box 3, Records of the U.S. Forces in South East Asia, 1950–1975, NND 974306, RG 472, entry: 33104, NARA, 3.

- USMACV Office of CORDS, MR1, Phuong Hoang Division, General Records 1603-03A: PRU Correspondence 1979 thru 1603-03A: Reports—VIET CONG/NVN Propaganda Analysis 1970, Memorandum GVN 1969 Pacification Development Plan, 21 December 1968, box 12, Records of the U.S. Forces in Southeast Asia, 1950–1975, NND 974306, RG 472, NARA, 1, hereafter Reports—VIET CONG/NVN Propaganda Analysis 1970, Memorandum GVN 1969 Pacification Development Plan.

- Reports—VIET CONG/NVN Propaganda Analysis 1970, Memorandum GVN 1969 Pacification Development Plan, 163–64.

- Reports—VIET CONG/NVN Propaganda Analysis 1970, Memorandum GVN 1969 Pacification Development Plan, 180.

- Mark Moyar, Phoenix and the Birds of Prey: Counterinsurgency and Counterterrorism in Vietnam (Lincoln, NE: Bison Books, 2007); and LtCol John L. Cook, The Advisor: The Phoenix Program in Vietnam (Lancaster, PA: Schiffer, 1997).

- Reports—VIET CONG/NVN Propaganda Analysis 1970, Memorandum GVN 1969 Pacification Development Plan, 180.

- USMACV Office of CORDS, MR 2 Phuong Hoang Division, General Records 207-01: Reorganisation 1970 thru 1602-08: GVN INSP RPTS 1970 MACCORDS Realignment of Phuong Hoang Management Responsibilities, box 5, Records of the U.S. Forces in South East Asia, 1950–1975, NND 974306, RG 472, entry 33205, NARA, hereafter GVN INSP RPTS 1970 MACCORDS Realignment of Phuong Hoang Management Responsibilities.

- USMACV Office of CORDS, MR 2 Phuong Hoang Division, General Record Operation Phung Hoang Rooting Out the Communist’s Shadow Government, box 4, Records of the U.S. Forces in Southeast Asia, 1950–1975, NND 974306, RG 472, entry 33104, NARA, 2.

- Col Andrew R. Finlayson, Marine Advisors with the Vietnamese Provincial Reconnaissance Unit, 1966–1970 (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps History Division, 2009), 15–16.

- “A COSVN Directive for Eliminating Contacts with Puppet Personnel and Other ‘Complex Problems’,” doc. 55, Translation and Analysis of Significant Viet-Cong/North Vietnamese Documents, April 1969, microfilm, reel 1, frame 0731, 3. ProQuest folder 003233-001-0731.

- “A COSVN Directive for Eliminating Contacts with Puppet Personnel and Other ‘Complex Problems’,” 3.

- USMACV Office of CORDS Pacification Studies Group, General Records Phung Hoang 1968 thru Vietnamization/C/S Letter 1969, box 3, Records of the U.S. Forces in Southeast Asia, 1950–1975, NND 003062, RG 472, entry PSG, NARA, 7–8.

- USMACV Office of CORDS, MR 2 Phuong Hoang Division, General Records 1602-08: US/GVN Insp Team Visits, July–December 1970 thru 1603-03A (A4), box 7, Records of the U.S. Forces in Southeast Asia, 1950–1975, NND 974305, RG 472, entry 33104, NARA, 2, hereafter US/GVN Insp Team Visits, July–December 1970 thru 1603-03A (A4).

- US/GVN Insp. Team Visits, July–December 1970 thru 1603-03A (A4).

- Finlayson, Marine Advisors with the Vietnamese Provincial Reconnaissance Unit, 1966–1970, 27.

- Finlayson, Marine Advisors with the Vietnamese Provincial Reconnaissance Unit, 1966–1970, 27.

- GVN INSP RPTS 1970 MACCORDS Realignment of Phuong Hoang Management Responsibilities, 1.

- Colby and McCargar, Lost Victory, 245.

- USMACV Office CORDS, MR 2 Phuong Hoang Division, General Records 1603-03A (B3): QTRLY. ADV. CONF., SAIGON 1970 thru 1603-03(C): MISC RPTS. 1970. Remarks of Col James B. Egger, MR III Phoenix Coordinator, at Quarterly Phoenix Coordinators’ Conference, 25 July 1970, box 9, Records of the U.S. Forces in South East Asia, 1950–1975, NND 974306, RG 472, entry 33205, NARA, 14–15, hereafter Remarks of Col James B. Egger.

- Remarks of Col James B. Egger, 15.

- USMACV Office of CORDS, MR 2 Phuong Hoang Division, General Records 204-57: Quang Nam Correspondence 1969 thru 204-57: Rifle Shot Operations 1969, Memorandum, Subject: CAP Participation in Phoenix/Phung Hoang Program, box 5, Records of the U.S. Forces in South East Asia, 1950–1975, NND 974306, RG 472, entry 33104, NARA.

- Remarks of Col James B. Egger, 14.

- “COSVN’s Preliminary Report on the 1969 Autumn Campaign,” doc. 82, Translation and Analysis of Significant Viet-Cong/North Vietnamese Documents, August 1970, microfilm, reel 3, frame 0001, 1. ProQuest folder 003233-001-0741.

- “COSVN’s Preliminary Report on the 1969 Autumn Campaign,” 1–2, 6–7.

- USMACV Office of CORDS Pacification Studies Group, General Records 1601-10A IV Corps/Phong Dinh/Trip Report 1970 thru 1601-11A Pacification Fact Sheets 1970, Pacification: End–December, box 9, Records of the U.S. Forces in Southeast Asia, 1950–1975, NND 994025, RG 472, NARA.

- Willard J. Webb, The Joint Chiefs of Staff and the War in Vietnam, 1969–1970 (Washington, DC: Office of Joint History, Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chief of Staff, 1970), 431–32.

- Webb, The Joint Chiefs of Staff and the War in Vietnam, 1969–1970, 448.

- Webb, The Joint Chiefs of Staff and the War in Vietnam, 1969–1970, 222–25.

- Richard M. Nixon, “Sir Robert Thompson (1970) (2 of 2) Visit to Vietnam October 28th–November 25th,” Presidential Materials Project, folder 102564-018-0215, NARA, 1–2.

- Richard M. Nixon, “Sir Robert Thompson (1971) Memorandum for the President, Subject: Sir Robert Thompson Comments on Vietnam,” Presidential Materials Project, folder 102564-018-0391, NARA, 1.

- Young, The Theory and Practice of Associative Power, 17.

- Mark Moyar, Triumph Forsaken: The Vietnam War, 1954–1965 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 283, 286, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511511646.

- Moyar, Triumph Forsaken, 286.