PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

Abstract: The 1st Viet Cong Regiment engaged in a series of costly clashes with the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) and allied forces in Vietnam’s I Corps from 1964 to 1967. A veritable phoenix, this Communist Main Force unit was destroyed in battle 13 times in that brief span and yet repeatedly regenerated its battered formations to fight again. This article assesses how that was possible, the nature of the Communist insurgency in I Corps, and how the U.S. Marines understood and responded to its dual political and military perils. This case study underscores the challenges inherent in hybrid warfare and suggests keys to simultaneously addressing conventional and irregular threats. The 1st Viet Cong Regiment’s impressive operational resilience illustrates, in microcosm, how and why the allied counterrevolutionary strategy failed to win in Vietnam.

Keywords: Vietnam War, 1st Viet Cong Regiment, Ba Gia Regiment, III Marine Amphibious Force, hybrid war, insurgency, counterinsurgency, I Corps, Operation Starlite, Operation Harvest Moon, Communist infrastructure, North Vietnamese Army, NVA, Viet Cong Main Force units, punishment and prevention strategies, pacification, search and destroy operations, Ho Chi Minh Trail, Army of the Republic of Vietnam, ARVN.

Introduction

During their first three years in Vietnam, U.S. Marines battled the 1st Viet Cong Regiment in a series of hard-fought actions. Despite a string of tactical victories, III Marine Amphibious Force (III MAF), the senior American headquarters in Saigon’s five northern provinces, failed to destroy this tough and elusive Communist foe. This article examines the regiment’s origins and composition, surveys its military achievements, and assesses what its story conveys about the larger conflict. The 1st Viet Cong Regiment’s impressive resilience illustrates, in microcosm, how and why the allied strategy failed to win the war.

Strategic and Operational Context

The Cold War between the United States and its Communist rivals turned Indochina into the deadliest arena of superpower strategic rivalry. America replaced France as the principal Western power in the region following the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu and their subsequent withdrawal from the newly established South Vietnam. Despite expanding American economic and military assistance between 1955 and 1962, Saigon struggled to control its territory against increasingly effective internal and external opposition. After President Ngo Dinh Diem’s assassination in a military coup in 1963, the south’s fortunes further waned. A series of ineffective national governments, plagued by growing Communist political and military attacks, wavered on the brink of collapse. By 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson determined that without U.S. military intervention, Communist forces would soon conquer South Vietnam; this he refused to allow.

Existing U.S. war plans anticipating a Chinese invasion of South Vietnam called for Marine Corps units to defend the country’s northern region while Army forces protected the Central Highlands, the approaches to the capital, and the vital Mekong rice basin. In March 1965, 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade deployed to Da Nang to guard American aircraft flying bombing missions into North Vietnam and free Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) units to focus on offensive operations. Two months later, the Marine brigade expanded into a force (corps-level) headquarters. Its mission soon morphed from a defensive to an offensive orientation, pursuing enemy units beyond the initial beachhead.

The region’s rugged terrain dictated many of the tactical challenges the Marines experienced during the next six years. Roughly the size of Maryland, this part of Vietnam rose from a narrow strip of cultivated lowlands along the sea through a forested piedmont zone to the jungle-clad Annamite mountain chain, with some peaks exceeding 5,000 feet, along the area’s western boundary with Laos. This forbidding environment gave ample cover and concealment to the Marines’ North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and Viet Cong enemies. The international borders that adjoined the Marine sector made the challenge of hunting skilled foes even more challenging. When hard-pressed by MAF and ARVN forces, Communist units could slip into North Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia to rest and replenish.

While Americans viewed the war as a defense of a nascent democracy against Communist aggression, Hanoi saw the conflict as a bid to destroy an illegitimate government and restore its people and territory to the rightful sovereignty of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. Between 1955 and 1965, Ho Chi Minh’s Communist party consolidated control of its newly won territory in the north while building the army it needed to conquer the south.1 In September 1964, the politburo decided to dispatch NVA units to the south to help defeat its enemy before the Americans could intervene.2 Some of these units entered the locale where III MAF arrived just a few months later. The Communist regulars sought to help southern insurgents destroy ARVN forces, seize South Vietnamese territory, control the area’s people, and collapse Saigon’s regional political power. The young recruits who marched to free the south had been thoroughly indoctrinated for the mission. In the words of Ho Chi Minh, approvingly cited in the NVA’s official history,

Our armed forces are loyal to the Party, true to the people, and prepared to fight and sacrifice their lives for the independence and freedom of the Fatherland and for socialism. They will complete every mission, overcome every adversity, and defeat every foe.

. . . Our armed forces have unmatchedstrength because they are a People’s Army, built, led, and educated by the Party.3

In the struggle to reunite the “fatherland,” the partners of these North Vietnamese troops were the indigenous Communists of the south. Both northern and southern soldiers played an important role in the 1st Viet Cong Regiment’s activation and subsequent combat actions.

The Viet Cong Insurgency4

The 1955 Paris Peace Accord separated Vietnam into northern and southern states. In the Republic of Vietnam (RVN), the Lao Dong (Workers’) Party supported Hanoi’s goal of unifying both Vietnamese states under Communist rule. The party worked in concert with remnants of the Viet Minh resistance still living south of the new demilitarized zone that partitioned the two countries. Communist cadres remaining in the south established the Viet Cong in 1956 to advance the party’s political and military goals. With its southern clients suffering from a successful Saigon crackdown on rebels between 1955 and 1958, Hanoi authorized a more militant response to President Diem’s regime in 1959.5

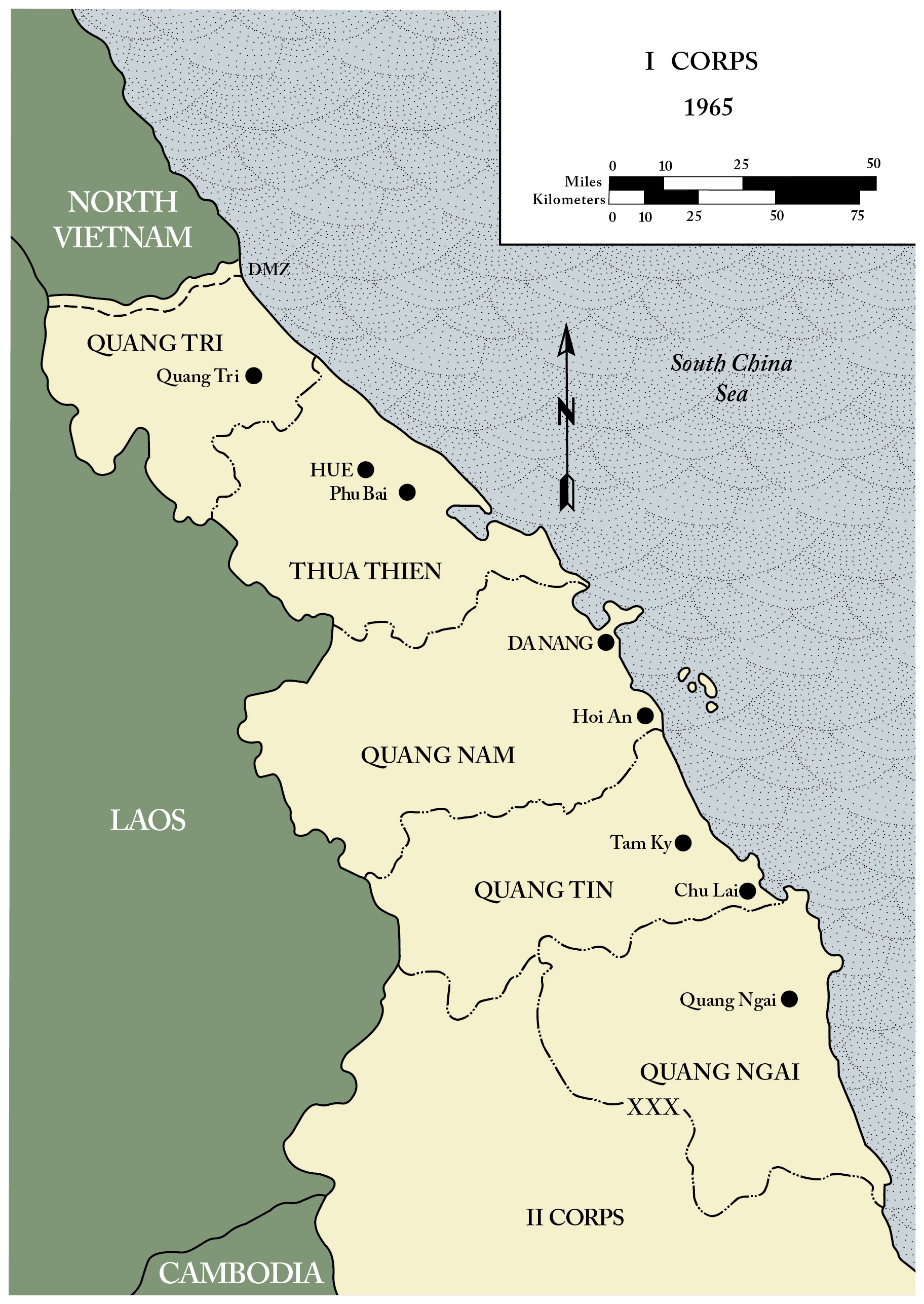

The fledgling insurgency was especially strong in three South Vietnamese provinces: Quang Nam, Quang Tin, and Quang Ngai. They occupied the lower extremity of what Saigon dubbed I Corps (figure 1), a sector that encompassed the top quarter of the republic’s 1,000-mile-long (1,609 kilometers [km]) territory. Near the end of III MAF’s tour in Vietnam, these three provinces (of 44 total) still accounted for 16.3 percent of the south’s total clandestine insurgents. Quang Nam’s share of the overall Viet Cong infrastructure remained the highest of any province in South Vietnam. This hotbed of Communist insurrection served as the birthplace of the 1st Viet Cong Regiment.6

Figure 1. South Vietnam’s I Corps (Military Region 1)

Jack Shulimson and Charles M. Johnson, U.S. Marines in Vietnam: The Landing and the Buildup, 1965 (Washington, D.C.: Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps History and Museums Division, 1978), 13.

The southern insurgency featured both political and military dimensions. The former comprised the more dangerous of the twin threats because its social organizations generated and sustained the armed resistance. The Communist infrastructure served as a shadow government, clandestine in regions ruled by Saigon and overt in areas the Communists controlled. This alternative bureaucracy collected taxes, resolved legal disputes, redistributed land, gathered supplies for its troops, sponsored subversion, assassinated political opponents, enlisted recruits for military service, organized social groups, distributed propaganda, and collected intelligence. The National Liberation Front, a “united front” designed to camouflage Hanoi’s hand in directing the insurgency’s policies, plans, and actions, duped many observers both in and out of Vietnam about the entirely indigenous roots and nature of the rebellion. Yet, Hanoi directed the front and its subversive minions. The Communist party’s extensive organizational structure controlled life in Viet Cong strongholds and contested government authority elsewhere. Together, the party’s political and military dau tranh (“struggle”) movements sought to undermine and then overthrow the Saigon regime.7

The insurgency’s military wing encompassed three levels. Paramilitary militia forces, called the Popular Army, furnished local security for Communist hamlets and villages. These ubiquitous black pajama-clad guerrillas, farmers by day and fighters by night, remain an iconic image of the Vietnam conflict. One step up the military chain, Communist regional or territorial forces provided full-time but still geographically restricted security services. These local troops normally served within their own district and seldom ventured farther afield. Main Force units, on the other hand, roamed across their home provinces and sometimes moved across province lines in support of regional offensives. They constituted the best-trained and -equipped insurgent formations and were designed to engage ARVN elements on equal terms in conventional battle. Insurgent fighters could be promoted, or conscripted, into higher level Viet Cong units. Whether advanced for meritorious service or drafted against their will, hamlet militia often augmented local district forces, who in turn furnished troops to casualty-depleted Main Force units.8 III MAF’s experience tracking and fighting a specific Communist Main Force unit, the 1st Viet Cong Regiment, illustrates the military and political challenges posed by these insurgent formations.

Rise of a Regiment

The 1st Viet Cong Regiment formed in February 1962. Initially, its rolls listed three infantry battalions (60th, 80th, and 90th Battalions) and one artillery battalion (400th Battalion). In July 1963, the regiment received a battalion-size draft composed of troops infiltrated from North Vietnam, the first of many such reinforcements imported from outside South Vietnam. Viet Cong Main Force battalions numbered approximately 450 troops until 1968, when their numbers dropped precipitously and never again recovered. A full-strength regiment, with three infantry battalions and a heavy weapons battalion (deploying mortars, recoilless rifles, and heavy machine guns) plus a headquarters element, typically numbered about 2,000 soldiers.9

Throughout 1964 and the first half of 1965, the 1st Viet Cong Regiment operated in I Corps’ Quang Tin and Quang Ngai Provinces and quickly demonstrated its combat proficiency. In July 1964, the 60th Battalion successfully ambushed a South Vietnamese engineer company. The next month, the 90th Battalion conducted a similar ambush on an ARVN detachment of armored personnel carriers. In October, the 40th Battalion (formerly the 80th) captured an ARVN company-size camp, scattering its defenders and destroying two light artillery pieces. The regiment conducted two battalion-level attacks on ARVN units in February 1965. Two more battalion assaults on South Vietnamese security forces followed in March and another in April. The latter attack marked the regiment’s eighth battalion-size operation in just 10 months.10

The 1st Viet Cong Regiment conducted its first regimental-size offensive on 19 April 1965, destroying a company of South Vietnamese troops. The second such attack targeted the 51st ARVN Regiment at Ba Gia Village, 20 miles (32 km) south of Chu Lai in Quang Ngai Province. After extensive sapper reconnaissance of the objective, the enemy regiment commenced a clash that extended through the last three days of May. Several hundred ARVN troops captured in this engagement underwent Communist reeducation and retraining and later fought for the 1st Viet Cong Regiment. The regiment struck Ba Gia again on 5 July, overrunning (again) the reconstituted 1st Battalion of the ARVN 51st Regiment, killing or wounding several hundred troops, and capturing two 105mm howitzers. Both the May and July battles represented epic triumphs, for which the victors assumed the title Ba Gia Regiment, but the two costly encounters also foreshadowed future pyrrhic struggles. The regiment’s 40th Battalion lost an entire company (with only one unwounded survivor) in the first fight and the rebuilt Viet Cong battalion was similarly damaged in the second engagement (where one company lost all but two soldiers dead or wounded).11

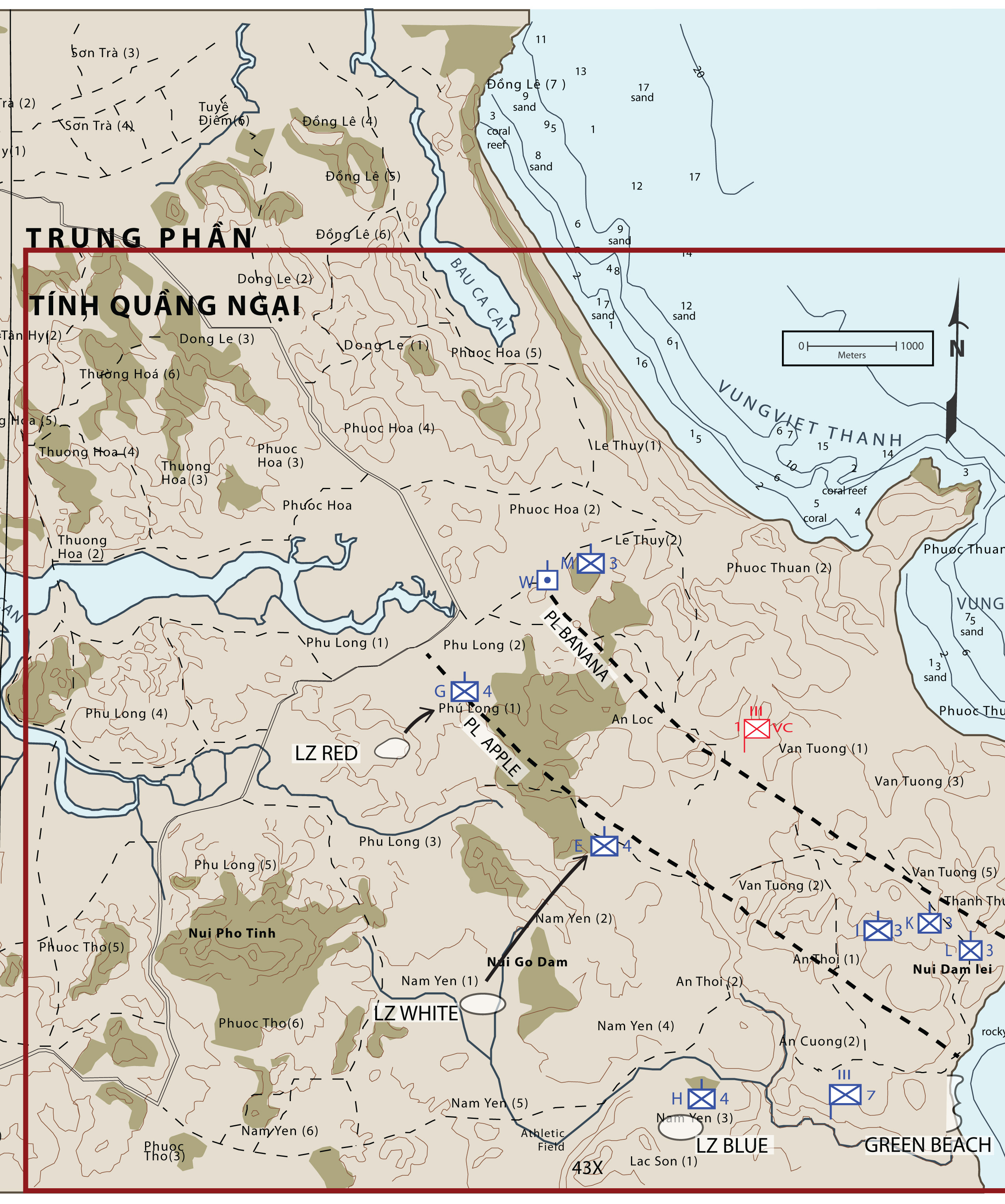

The Marines’ first contact with the Ba Gia Regiment took place in August 1965. III MAF’s intelligence section received multiple reports from a variety of sources that the Viet Cong regiment was staging a few kilometers south of the Chu Lai airstrip and possibly planning an attack on the Marine base.12 A Viet Cong deserter and fresh signals intelligence soon confirmed the enemy regiment’s location in a village just 12 miles (19 km) south of the airfield.13 General Lewis W. Walt immediately tasked 7th Marine Regiment to plan and conduct a spoiling attack on the 1st Viet Cong Regiment. The enemy battalions were spread out across a 36-square-mile (58 square km) sector of rice paddies and rolling hills, sprinkled with two dozen small hamlets, and flanked on the east by the South China Sea.

The operation, code named Starlite and launched on 18 August, encompassed a Marine rifle company that moved by truck to block the northern portion of the targeted zone, a heliborne battalion that landed to the west of the enemy’s anticipated location, and a second battalion that came ashore over the beach to link up with the air mobile assault element and then drive the insurgents back toward the sea, where the guns of the fleet and a third amphibious battalion waited to complete their destruction (figure 2).14 The attack surprised and damaged two of the 1st Viet Cong Regiment’s infantry battalions and elements of its weapons battalion.15 In the ensuing battle, the Marines counted 614 dead insurgents, captured 9 prisoners, and detained 42 suspects.16 The 2,000-strong 1st Viet Cong Regiment lost 30 percent of its strength in this engagement. By doctrinal standards, the unit was destroyed.17 Yet, it lived to fight another day—and that day was not long in coming.

Figure 2. III MAF’s Operation Starlite, August 1965

Map adapted by Marine Corps History Division, Col Rod Andrew Jr., The First Fight: U.S. Marines in Operation Starlite, August 1965 (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps History Division, 2015), 25.

In September, III MAF located, via aerial photographs of new fortifications, what it assessed as remnants of the 1st Viet Cong Regiment eight miles (13 km) south of the Operation Starlite battlefield. In a three-day combined ARVN/Marine operation (Piranha), again under 7th Marines’ control, American reports noted 178 Viet Cong dead and 360 detained suspects. Despite the damage done, the bulk of the 1st Viet Cong Regiment escaped the area a day before Piranha kicked off.18 In November, just three months after Starlite, the 1st Viet Cong Regiment, reinforced with a new influx of North Vietnamese regulars, destroyed the ARVN post at Hiep Duc in Quang Nam Province. The headquarters of U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (USMACV) ordered General Walt to strike the enemy lair in the Que Son Valley before the Communists could exploit their latest victory. III MAF intelligence reports estimated the regiment’s rebuilt strength at 2,000 soldiers with another four unaffiliated Viet Cong battalions in the area for a total Communist force of approximately 4,700 fighters.19

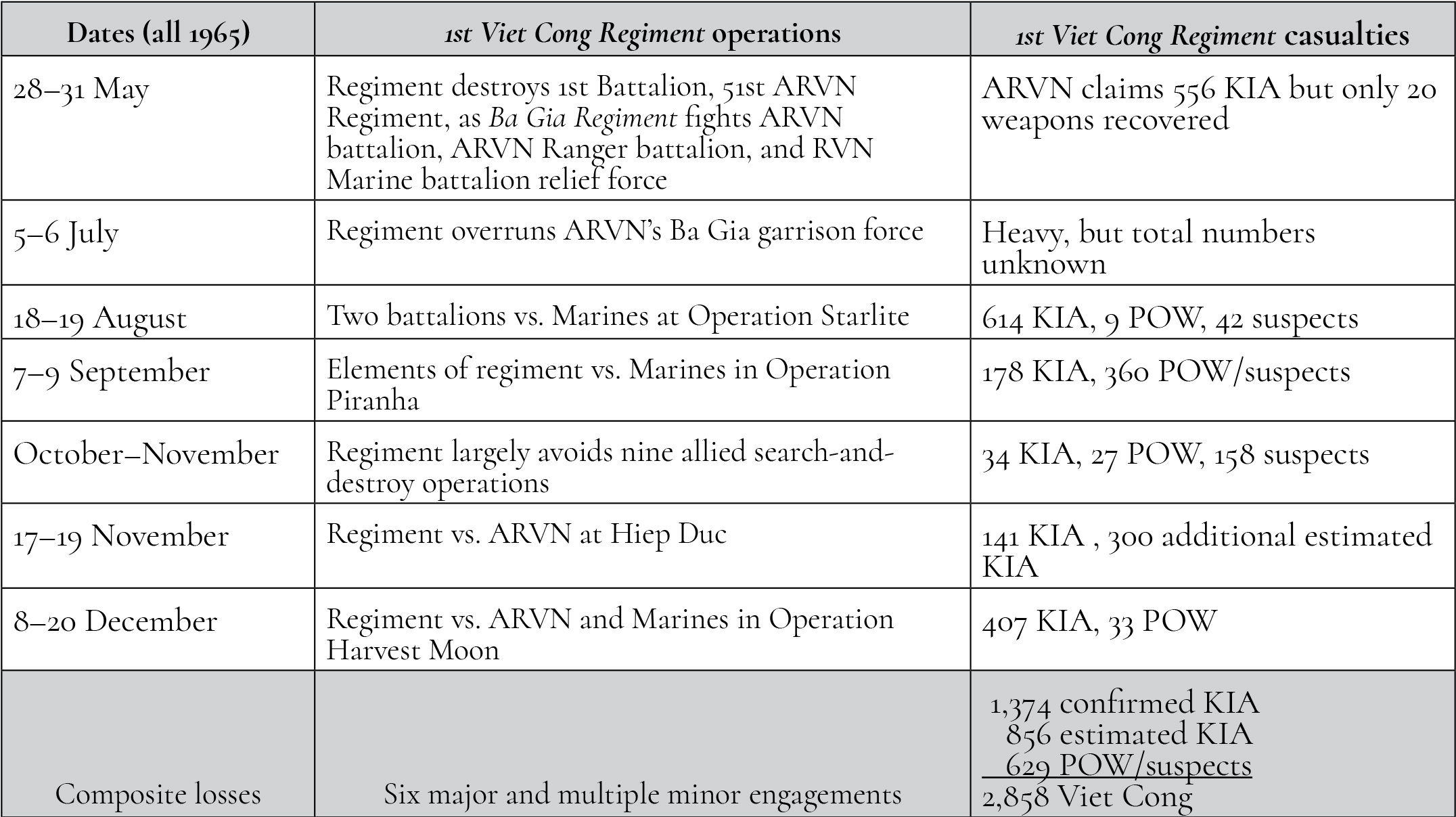

The MAF assigned a Marine unit of brigade strength (Task Force Delta), reinforced by a similar-size ARVN unit, to fix and destroy the cagey Viet Cong. Lacking solid intelligence on the specific location of the enemy, the Marine plan (Operation Harvest Moon) directed South Vietnamese troops to advance to contact, then hold the Communists in place while two U.S. battalions deployed by helicopter to attack from the rear and cut off their retreat to the western mountains. Rather than being trapped, the 1st Viet Cong Regiment mauled the advancing ARVN regiment in an ambush. Marine ground forces, slow to assist, engaged elements of the 60th and 80th Battalions (the first from the 1st Viet Cong Regiment, the other an independent battalion) for a day and a half, then spent the next 10 days in mostly fruitless pursuit of the enemy. Though the intermittent fighting produced, according to American records, 407 Viet Cong killed in action at a cost of 164 ARVN and Marine dead, Harvest Moon did not achieve the intended destruction of the 1st Viet Cong Regiment. Instead, it foreshadowed how difficult it would be in I Corps to capture or destroy insurgents who chose when and where to fight.20 Harvest Moon marked the allies’ final major contact with the 1st Viet Cong Regiment in the first year of the U.S. ground war. Table 1 summarizes known and estimated casualties (killed and captured) the Ba Gia Regiment suffered in 1965 alone.

Table 1. 1st Viet Cong Regiment’s major operations and losses, 1965

Note: KIA = killed in action; POW = prisoner of war. Data derived from Shulimson and Johnson, The Landing and the Buildup, 1965, 51, 69–111; and Lehrack, The First Battle, 51–54.

Throughout 1966 and 1967, ARVN, Marine, U.S. Army, and South Korean troops repeatedly pursued and engaged the 1st Viet Cong Regiment. In February 1966, a major combined operation (Double Eagle II) located but failed to destroy the ghostly formation in the old Harvest Moon area of operations.21 The following month the Ba Gia Regiment destroyed a South Vietnamese regional force company at An Hoi in Quang Ngai Province. In response, the Marines and ARVN launched Operation Texas/Lien Ket 28 in March, which engaged the 1st Viet Cong Regiment’s 60th and 90th Battalions fighting from fortified villages. The allies killed 264 insurgents in four days, but the bulk of the enemy forces escaped in the night each time they were cornered.22 In April 1966, the ARVN and 7th Marines conducted Operation Hot Springs/Lien Ket 36 in the Chu Lai area, killing 349 more members of the 1st Viet Cong.23 Despite those casualties, III MAF intelligence reports still assessed the 1st Viet Cong at full strength (2,000 troops) in June.24 Throughout the latter half of 1966, the enemy regiment remained relatively quiet, avoiding major operations and contacts.

The following year proved particularly punishing for the Ba Gia Regiment. In February 1967, it attacked a Republic of Korea (ROK) Marine company and engaged elements of the 2d ARVN division in Quang Ngai Province, losing more than 800 dead in the course of several weeks’ fighting.25 The next month, the Viet Cong unit ambushed a company-size South Vietnamese irregular patrol near Minh Long.26 In August 1967, another Marine operation, Cochise, killed 156 and captured 13 Ba Gia soldiers.27 The 1st Viet Cong Regiment suffered similar casualties in September in a combined Marine/ARVN operation (Swift/Lien Ket 116).28 Between 24 and 26 September, the U.S. Army’s Americal Division (23d Infantry Division) piled on the punishment, inflicting another 376 casualties in battles northeast of Tien Phuoc in Quang Nam Province.29 Thoroughly battered and judged combat ineffective by October 1967, the Ba Gia Regiment played little role in the 1968 Tet offensive.

Assessing the 1st Viet Cong Regiment

The III MAF intelligence shop, exploiting ARVN, USMACV, and national assets as well as its organic collection capabilities, tracked the 1st Viet Cong Regiment closely. This Main Force unit appeared in almost every Marine intelligence summary produced during the war. These reports listed updates on unit locations, strengths, casualties, movements, morale, tactics, training, leaders, health, and alias titles used for deception purposes.30

The Ba Gia Regiment suffered catastrophic losses in the two and a half years following America’s entry into the war. In 1965, it suffered, according to American counts, 1,340 confirmed dead in the Starlite, Piranha, Hiep Duc, and Harvest Moon battles. In 1966, it lost another 753 dead or taken prisoner in Operations Double Eagle II, Texas, and Hot Springs. The following year was worse, with 1,535 killed or captured in a series of battles against allied forces between February and September. Given its consistent 2,000-man organizational strength, these figures represent losses of 67 percent in 1965, 38 percent in 1966, and 76 percent in 1967.

These casualties were even worse than they sound. The numbers do not include wounded, assessed by USMACV at a 1:1.5 killed-to-wounded ratio for the Viet Cong and NVA.31 They also do not reflect estimates of additional deaths killed by supporting arms or those who died of wounds but whose bodies could not be recovered. Using the USMACV formula, the projected wounded alone would have added another 5,442 casualties to the regiment’s total losses during the 30-month period. The 30 percent doctrinal destruction threshold, if applied to the Ba Gia Regiment and counting only confirmed dead and prisoners, resulted in a unit that was destroyed twice in 1965, once in 1966, and twice more in 1967. Incorporating estimated wounded into the total losses ascribed to the unit meant that it was “destroyed” 13 times during that short period. A veritable phoenix, the 1st Viet Cong Regiment incredibly continued to reconstitute, strike, and evade allied forces for the rest of the war. It fought in the final 1975 Communist offensive that ended the conflict.32

The 1st Viet Cong Regiment lost many battles against the Marines, but it persevered as a force in arms to contest Saigon’s control of the region. The unit helped defeat the American strategy of attrition by waging an effective recruiting and replacement campaign. The regiment initially gathered most of its soldiers from the local villages. The stirring Ba Gia victories of 1965 likely made it easier to convince the already strongly pro–Viet Cong inhabitants of the region to enlist, but any such enthusiasm was doubtless tempered by the 50-percent losses suffered by 40th Battalion during the Ba Gia campaign. Subsequently, the regiment de-emphasized voluntary enlistments and ordered district and village guerrilla units to provide replacements for its Main Force battalions. After Operation Starlite, the Communists were forced to rely more on coercion and began to recruit women to strengthen the 1st Viet Cong Regiment.33

The 195th Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion, which joined the regiment in early December 1965, illustrated the other way the 1st Viet Cong Regiment replaced its battle losses. Both whole units and periodic manpower replacement drafts infiltrated from the north via the Ho Chi Minh Trail.34 Members of the 45th Heavy Weapons Battalion, for example, also hailed largely from North Vietnam. It was common for machine gun and mortar units to feature northern soldiers since it was difficult to provide recruits appropriate training on these systems in I Corps during the early days of the war.35 As time passed, more replacements from North Vietnam came into Viet Cong units to fill out the depleted ranks of the supposedly southern insurgent formations. By July 1967, allied intelligence reports indicated the regiment’s 60th Battalion contained mostly North Vietnamese regulars who infiltrated into the RVN via the Ho Chi Minh Trail.36 After the 1968 Tet offensive, it was not uncommon for two-thirds of the soldiers in Viet Cong formations in I Corps to be North Vietnamese.37

Ba Gia Regiment recruits from the north attended a 15-day training course near Binh Giang in the Red River delta, where they received basic military and political instruction. Heavy emphasis was placed on the latter so the new soldiers would understand why they were fighting. Trainees mastered only rudimentary combat skills. Upon completion of the initial school, graduates joined an element of the regiment; there they completed further training under the tutelage of their new leaders. This was where they learned the unit’s standard operating procedures and the advanced skills necessary to compete on an equal footing with ARVN and the Americans. Live-fire training was particularly difficult to accomplish in I Corps due to the need for concealment from government and allied forces. Soldiers selected to attend subsequent specialist instruction, such as squad leader, sapper, and crew-served weapons courses, had to travel farther afield to secure zones in the RVN’s remote mountains, cross-border sanctuaries in Laos and Cambodia, or inside North Vietnam. The unit’s training system, though unsophisticated, proved adequate. Only three months after Operation Starlite, the regiment had recuperated sufficiently to destroy an ARVN battalion at Que Son and bloody a Marine battalion at Ky Phu.38

Most of the 1st Viet Cong Regiment’s weapons, ammunition, communications equipment, and medical supplies were either brought down the Ho Chi Minh Trail or captured from ARVN forces. Uniforms were imported from the north. The local population provided food and other logistic support, including limited nursing care and porter services when required. Southern peasants did not always provide this support, particularly the rice tax, willingly. Nonetheless, the regiment managed to sustain itself throughout the heavy fighting of 1965.39

While few NVA soldiers deserted once they reached the south, approximately 150,000 Viet Cong abandoned the Communist cause between 1965 and 1969.40 Communist soldiers who fled the 1st Viet Cong Regiment mirrored the profiles of other disillusioned insurgents who surrendered across the south. Analysis of those who capitulated country-wide in early 1966 (11 percent of whom were in I Corps) painted a dim view of life as a rebel. Almost all (90 percent) cited poor medical care while one-third mentioned that malaria was rampant among the ranks. Few were well educated, with 70 percent having three years or less of schooling. Half of the Communist deserters had been drafted (they were not volunteers), while 20 percent were forced to join the Viet Cong. Almost two-thirds (61 percent) fled because of terrible living conditions. Fully half of the enemy soldiers claimed no knowledge of what the war was about, noted that food for Communist troops was scarce, and observed that southern peasants gave little voluntary support to the Communist cause. More than one-third quit because of moral or ideological dissatisfaction with the Communists’ actions.41 Ralliers (Viet Cong soldiers and political cadre who surrendered to allied forces) from the 1st Viet Cong Regiment consistently cited low morale, poor healthcare, and little food, though no shortage of ammunition.42 Such insights gave analysts a good sense of the regiment’s strengths and weaknesses, but the continuous scrutiny did not enable allied forces to fix and finish their wary and weary foe.

Main Force units like the Ba Gia Regiment comprised the most lethal but not the most numerous Viet Cong opposition in I Corps. In the spring of 1967, III MAF identified 29,000 full-time enemy soldiers in the region, including Main Force and Local Force units. But the G2 intelligence analysts also listed 75,000 irregulars serving as hamlet and village militia, civilian supporters, and political infrastructure.43 Unlike the Main Force units that gained a steadily increasing proportion of NVA regulars throughout the conflict, the part-time soldiers and their civilian supporters were primarily native South Vietnamese. Initially, the III MAF estimates of enemy strength included the part-time guerrillas, but not their unarmed assistants.

Two years into the war, these local civilian supporters of the Viet Cong finally found a place on the Marine roster of enemy forces. Reflecting the contentious debate between USMACV and the CIA/State Department on enemy combatant numbers, III MAF order of battle reports began in February 1967 to incorporate additional types of militia forces into the total tally of I Corps enemy. The new categories included supporting forces such as self-defense forces and secret self-defense forces. These affiliated Viet Cong sympathizers, not previously counted as enemy because they were seldom armed or directly confronted allied forces, were henceforth included for completeness’s sake. This data added more than 50,000 personnel to the aggregate I Corps enemy, though the MAF report explained that this change was an accounting modification, not an addition to the number of armed enemy forces that had been operating in the region.44

The new reporting standards, however, did not indicate a new MAF emphasis on the guerrilla menace. From the beginning, Marine commanders took the guerrilla and political portion of the hybrid conventional-irregular war seriously. They initiated a balanced intelligence and operational approach, featuring a wide variety of actions designed to protect the South Vietnamese population from village-level insurgent political and military threats. The five I Corps provinces represented a Viet Cong organizational stronghold, so the “small war” for control of the rural population remained a bitter and strongly contested affair throughout III MAF’s tenure in Vietnam. Fully 20 percent of total American combat fatalities in the war, for instance, occurred in the area around Da Nang where the 1st Viet Cong Regiment spent much of its time.45

Like its USMACV counterpart, the Marine intelligence directorate expanded and developed its collection and assessment capabilities as the war progressed. The MAF’s order of battle analysts tracked the insurgent threat closely. There is less evidence that senior Marine leaders appreciated or acted on what the information gathered meant for the MAF’s regional operational approach or USMACV’s theater strategy. The data they collected suggested two explanations for the amazing recuperative abilities of the enemy’s Main Force units such as the 1st Viet Cong Regiment. The first was access to a rural population that could be persuaded or coerced to send its sons and husbands to fight under the Communist banner. The second was a steady resupply of fresh regular troops infiltrated from the north. Together these manpower reservoirs enabled savaged Viet Cong battalions and regiments in I Corps to reform and continue to fight.

Along with their Main Force comrades, local forces and militia proved equally resilient during the first three years of the war. The continued regeneration of all types of Communist military forces, despite their regular mauling by superior allied firepower, indicated that General William C. Westmoreland’s attrition strategy, coupled with the aerial interdiction effort, had not attained the promised crossover point beyond which the enemy could no longer make good their losses. Nor had the punishment strategy, exemplified by the Rolling Thunder bombing campaign against the north, convinced Hanoi to cease its efforts to conquer the south. The resiliency of the various Viet Cong formations in I Corps also underscored the pacification strategy’s failure to secure South Vietnam’s countryside, convince all its people to support the Saigon government, and refuse to join Communist military units.

Hybrid War Implications

The 1st Viet Cong Regiment case study illustrates the challenges of winning in a hybrid war environment that blends nonmilitary means with conventional and irregular combat operations. The Vietnam conflict represented a revolutionary struggle in which the north, aided by elements of the southern population, sought to destroy the government of the south. Saigon’s counter-revolutionary campaign (and by extension America’s) incorporated social, economic, political, informational, psychological, and military dimensions. The allied military role was two-fold: (1) buttressing the Saigon government’s legitimacy by protecting its citizens; and (2) coercing its Communist opponents to give up the struggle. In simple terms, this equated to defending the South Vietnamese people from Communist attack and political control. These goals required defeating both the persistent Viet Cong insurgency and continuous NVA invasions.

Military options available to achieve those objectives included: search and destroy operations to attrite enemy ground forces inside South Vietnam; pacification operations to turn or “rally” homegrown opponents and secure the political and military support of the south’s populace; interdiction of infiltration routes to slow or block the arrival of reinforcements; punishment of the north via bombing and blockade; and invasion to force Hanoi’s capitulation. Washington ruled out invasion. Intermittent allied bombing campaigns of varying scale failed to pressure the north to cease its attacks on the south. Naval blockade commenced only in 1972, when it helped convince Hanoi to accept America’s offers to withdraw from the conflict, but a naval quarantine was not used earlier or more aggressively to coerce Hanoi to make a real peace. Aerial interdiction of critical supply lines via bombing proved ineffective, as it had when tried in Italy during World War II and throughout the Korean War.46 American presidents also disallowed stationing U.S. troops across Laos to block the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

Given the reduced military menu of choices, General Westmoreland opted to emphasize search-and-destroy operations with the goal of killing more Communists than could be generated internally or infiltrated from the north.47 This tactic failed for three reasons: (1) land infiltration routes remained unblocked; (2) enemy units could retreat when necessary to sanctuaries in Cambodia, Laos, and North Vietnam, returning when ready to renew the fight; and (3) pacification operations diminished but never dried up the supply of southern recruits. The saga of the 1st Viet Cong Regiment, bruised but defiant, thus underscores in microcosm the strategic dilemma that led to Saigon’s defeat. Too weak to protect its people from dual insurgent and conventional threats even with the assistance of more than half a million allied troops, the south was doomed once American forces departed.

If a decisive offensive against the primary source of Communist aggression was politically impossible, only a combination of the punishment, prevention, and pacification strategies afforded a reasonable chance to successfully defend the south. An earlier and stronger emphasis on pacification, akin to the operations CORDS conducted between late 1968 and 1972, promised to simultaneously protect the South Vietnamese people and deny the enemy critical local support.48 Ground interdiction of the Ho Chi Minh Trail, a prevention strategy, offered the strongest potential to degrade or deny the primary external avenue of aid for insurgent Main Force units in I Corps.49 Both local Viet Cong and infiltrated NVA units depended on, and would have faced far greater challenges without, these internal and external sources of supply. Strategic bombing of the north, naval blockade, and search-and-destroy operations inside South Vietnam, all variations of a punishment strategy, complemented but could not replace the other options. In classical mythology, Hercules defeated the multiheaded Hydra only by cutting off its heads and cauterizing its necks. In Vietnam, victory required the south to cut off its enemy’s access to the people and to outside sources of supply. Failure to do both left Communist units such as the 1st Viet Cong Regiment free to regenerate and strike repeatedly.

Within the north’s dau tranh strategy, the primary purpose of insurgent military forces was to protect and project its own political infrastructure. The party’s shadow government enacted the social, economic, and political policies and directed the organizational web that exerted control over the population. It represented the insurgency’s beating heart, its “center of gravity” in Clausewitzian terms.50 Main Force units like the Ba Gia Regiment, as well as smaller local forces and militia elements, engaged ARVN and American troops to defend and extend the Communist infrastructure. Destroying a Main Force regiment damaged the military protective shell but did not undermine the political core it shielded.51 Allied efforts to attack the infrastructure directly via the Phoenix program did not gain momentum until after the 1968 Tet offensive and never completely uprooted the shadow government’s complex social and political network in I Corps.52

At the tactical level, U.S. and ARVN attacks on the 1st Viet Cong Regiment proved costly. In most cases, allied forces encountered the regiment’s soldiers in hastily prepared defensive positions. Main Force units were as well armed with assault rifles, machine guns, and light mortars as their free world foes.53 Attacking allied forces accordingly paid a steep price to pry Ba Gia soldiers from their trenches and bunkers. Allied superiority in artillery and airpower reduced friendly casualties, but closing the final hundred yards to a fortified position still required costly exposure to deadly direct fire. While superior American training, marksmanship, and firepower reduced the impact, infantry combat in I Corps nonetheless produced casualty ratios that ranged from 10 to 70 percent of the high losses attributed to the 1st Viet Cong Regiment.54 By 1969, a myriad of these recurring clashes across the south translated even this uneven exchange rate into an aggregate cost the American public proved unwilling to pay.55 Meanwhile, Hanoi’s politburo refused to blink as the war ground on.

Conclusion

Hybrid wars feature conventional and irregular tactics, either of which can prove fatal to a victim facing both threats. The 1st Viet Cong Regiment case study suggests that it is not enough for a government’s armed forces to destroy enemy military units, even many times over, if wartime policies allow a foe cross-border sanctuaries and unblocked invasion routes. This case also highlights the importance of engaging early, effectively, and directly the infrastructure that insurgent armed forces exist to protect. The longevity and regenerative strength of the 1st Viet Cong Regiment reflected the strength of the Communist political organization in the south, the dogged endurance of its military wing, and the failure of allied punishment strategies that did not destroy the enemy’s infrastructure and stop repeated NVA incursions into Saigon’s territory.

The fierce fighting spirit and resilience of the Ba Gia Regiment did not prevent the unit’s tactical defeat at Starlite and in many subsequent encounters with allied forces. During the American phase of the conflict, of course, battlefield victory and defeat did not prove decisive. The north absorbed far higher losses than the allies, but its will to unify Vietnam under Communist rule remained unbroken. America withdrew in 1973 and abandoned its ally. Saigon fell in 1975 to a conventional NVA invasion abetted by the enervating effects of a lingering, if debilitated, insurgency. The phantom 1st Viet Cong Regiment survived, and Hanoi won the war, because allied strategy failed to destroy the Viet Cong infrastructure and prevent NVA armies from flooding the south.

•1775•

Endnotes

- Merle L. Pribbenow, trans., Victory in Vietnam: The Official History of the People’s Army of Vietnam, 1954–1975 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2002), 1–150.

- Pribbenow, Victory in Vietnam, 137–38. The official title of Hanoi’s army was the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN). This article employs the term North Vietnamese Army (NVA), which non-Communist organizations, agencies, and leaders more commonly used at the time.

- Pribbenow, Victory in Vietnam, 150. For a better understanding of how thoroughly the party brainwashed North Vietnam’s children, see Olga Dror, Making Two Vietnams: War and Youth Identities, 1965–1975 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2018), https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108556163. Some of these young northern troops experienced cognitive dissonance when they encountered better political, economic, and social conditions in the south they had come to “liberate.”

- The South Vietnamese government dubbed its internal Communist adversaries Viet Cong. U.S. and other allied forces adopted the moniker to describe both political and military elements of the insurgency. The insurgent movement formed the National Liberation Front in 1960. Its military wing became the People’s Liberation Armed Forces. This article uses Viet Cong because it was the term RVN and allied forces most frequently employed to describe insurgents during the conflict.

- George C. Herring, America’s Longest War: The United States and Vietnam, 1950–1975, 5th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill Education, 2014), 56, 80–84.

- Thomas C. Thayer, War without Fronts: The American Experience in Vietnam (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2016), 207. I Corps (later renamed Military Region 1) was a political and military zone formed by South Vietnam’s five northernmost provinces. This area, 265 miles (426 km) long and 30–70 miles (48–113 km) wide, held approximately 2.6 million citizens in 1965. The ARVN fielded a military corps also called I Corps in the same sector. In addition to their military duties, the ARVN I Corps commanding general served as the region’s top civil government official.

- Douglas Pike, Viet Cong: The Organization and Techniques of the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam, 2d ed. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1967), 85–87. More recent scholarship furnishes compelling evidence of Hanoi’s control of the southern insurgency throughout the conflict. See, for example, Lien-Hang T. Nguyen, Hanoi’s War: An International History of the War for Peace in Vietnam (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012), 127–28. Even Communist sources highlight Hanoi’s controlling hand. Pribbenow, Victory in Vietnam, xvi.

- Michael Lee Lanning and Dan Cragg, Inside the VC and the NVA: The Real Story of North Vietnam’s Armed Forces, 2d ed. (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2008), 81–82; and Pike, Viet Cong, 234–39.

- III MAF Periodic Intelligence Report (PERINTREP) #42, 20 November 1966, Annex A (Order of Battle), A-2 to A-3, Historical Resources Branch, COLL/5348, Vietnam War Command Chronologies, Marine Corps History Division (MCHD), Quantico, VA. Other sources list the regiment’s fire support battalion as the 45th Heavy Weapons Battalion. Jack Shulimson and Maj Charles M. Johnson, U.S. Marines in Vietnam: The Landing and the Buildup, 1965 (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1978), 70, hereafter The Landing and the Buildup, 1965; and Otto J. Lehrack, The First Battle: Operation Starlite and the Beginning of the Blood Debt in Vietnam, 2d ed. (New York: Presidio Press, 2006), 48–49.

- Lehrack, The First Battle, 48.

- Shulimson and Johnson, The Landing and the Buildup, 1965, 51, 69; and Lehrack, The First Battle, 47–54.

- Sources of these reports included local Vietnamese agents, National Police, District Headquarters, RVN Military Security Services, ARVN I Corps, and ARVN 2d Division, III MAF Command Chronology, August 1965, Significant Events (Quantico, VA: Historical Resources Branch, MCHD), 5.

- What the official history called “corroborative information from another source” was in fact signals intelligence from III MAF’s 1st Radio Battalion (an intelligence collection unit) and National Security Agency assets working for U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (USMACV). USMACV’s J2 claimed credit for locating the Viet Cong regiment’s headquarters in his book on USMACV intelligence operations. MajGen Joseph A. McChristian, The Role of Military Intelligence, 1965–1967, Vietnam Studies (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 1974), 9; Col Rod Andrew Jr., The First Fight: U.S. Marines in Operation Starlite, August 1965, Marines in the Vietnam War Commemorative Series (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps History Division, 2015), 9–10; and Shulimson and Johnson, The Landing and the Buildup, 1965, 69–70.

- Shulimson and Johnson, The Landing and the Buildup, 1965, 70–72; and Andrew, The First Fight, 10–17.

- The 1st Viet Cong Regiment’s four subordinate units were now numbered the 40th, 60th, and 90th Viet Cong Infantry Battalions and the 45th Heavy Weapons Battalion. Communist units sometimes changed their names and numbers to confuse allied intelligence collection efforts. Prebattle Marine intelligence indicated the 40th and 60th Battalions and the regimental command were present along with parts of the 90th and 45th Weapons Battalions. The Communist regiment’s command post was actually located 10 miles (16 km) south of the battlefield, along with the rest of the weapons battalion and 90th Battalion. Andrew, The First Fight, 10; and Lehrack, The First Battle, 64.

- Shulimson and Johnson, The Landing and the Buildup, 1965, 80.

- Contemporary U.S. military doctrine regards unit casualties of 30 percent as destruction criteria. See Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures for Observed Fire, U.S. Army Field Manuel (FM) 6-30 (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 1991), E-4; and Field Artillery Operations and Fire Support, FM 3-09 (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 2014), 1-3.

- Shulimson and Johnson, The Landing and the Buildup, 1965, 84–88.

- Nicholas J. Schlosser, In Persistent Battle: U.S. Marines in Operation Harvest Moon, 8 December to 20 December 1965, Marines in the Vietnam War Commemorative Series (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps History Division, 2017), 7–9. III MAF intelligence reported that NVA regulars were integrated into Viet Cong units after Starlite to boost shaken morale. III MAF Command Chronology, September 1965 (Quantico, VA: MCHD), 6.

- Shulimson and Johnson, The Landing and the Buildup, 1965, 101–11; and Schlosser, In Persistent Battle, 10, 38–47. III MAF carried the 1st Viet Cong at half strength in its order of battle assessments after Harvest Moon. III MAF Command Chronology, December 1965, Significant Events (Quantico, VA: MCHD), 2. Early in the operation, Gen Nguyen Chanh Thi, commanding ARVN’s I Corps, angrily withdrew his forces from what had been designed as a classic “hammer and anvil” operation because he concluded that Task Force Delta had been tardy in coming to his troops’ rescue after the 8–9 December ambushes. It was 26 hours from the initiation of the first Viet Cong attack before Marines linked up with ARVN remnants on the ground, even though 2d Battalion, 7th Marines, was less than 29 miles (47 km) by road from the ambush site and 3d Battalion, 3d Marines, was 36 miles (58 km) by road when the first ambush started on 8 December. Both battalions flew in on 9 December. It was just 18 miles (29 km) by air for 2d Battalion from Tam Ky and 13 miles (21 km) by helicopter for 3d Battalion from the logistics base located 3 miles (5 km) north of Thang Binh, where it had moved from Da Nang by motor march on the morning of 9 December.

- Warren Wilkins, Grab Their Belts to Fight Them: The Viet Cong’s Big-Unit War Against the U.S., 1965–1966 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2011), 150; Jack Shulimson, U.S. Marines in Vietnam: An Expanding War, 1966 (Washington, DC: Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps History and Museums Division, 1982), 34–35, hereafter An Expanding War, 1966. Operation Double Eagle II, despite missing its prey, nevertheless killed 125 and captured 15 insurgents in its sweeps of the area that most of the 1st Viet Cong Regiment soldiers had already evacuated.

- Wilkins, Grab Their Belts to Fight Them, 165–71; Shulimson, An Expanding War, 1966, 120–27; FMFPAC Msg to CMC, 0521Z 25 March 1966, Miscellaneous File, Named Operations Folder, Op File–Op Texas–20–26 March 1966, Collection 5348 (COLL/5348), Vietnam War Command Chronologies, MCHD, 63; and USMACV Msg to NMCC, 1325Z 25 March 1966, Miscellaneous File, Named Operations Folder, Op File–Op Texas–20–26 March 1966, COLL/5348, Vietnam War Command Chronologies, MCHD, 66.

- Wilkins, Grab Their Belts to Fight Them, 171; Shulimson, An Expanding War, 1966, 131; Memo of FMFPAC phone conversation with USMC Command Center, 0350R, 22 April 1966, Miscellaneous File, Named Operations Folder, Op File–Op Hot Springs–20–23 April 1966, COLL/5348, Vietnam War Command Chronologies, MCHD, 25; and III MAF Command Chronology, April 1966 (Quantico, VA: MCHD), 4, 6, and 8. Hot Springs, targeting the Viet Cong regimental command post and two of its battalions, was triggered by reports derived from a defector from the 1st Viet Cong Regiment. III MAF, 1966, January–June Intel Reports, COLL/5348, Vietnam War Command Chronologies, MCHD, 179.

- “III MAF VC/NVA Order of Battle, I Corps Area, 1 June 1966,” III MAF Command Chronology, June 1966, Enclosure 9: III MAF VC/NVA Order of Battle, I Corps Area (Quantico, VA: MCHD), 5. These estimates were confirmed by multiple sources and carried the 1st Viet Cong headquarters strength at 800 with three battalions (60th, 80th, and 90th) fielding 400 troops each. Note that the 40th Battalion was again listed as the 80th Battalion.

- The 1st Viet Cong Regiment’s failed 15–16 February 1967 attack on the ROK Marine company alone resulted in 243 confirmed killed in action (KIA). III MAF Command Chronology, February 1967 (Quantico, VA: MCHD), 17. For casualties resulting from ARVN contacts, see III MAF, Intel Reports, January–February 1967, COLL/5348, Vietnam War Command Chronologies, MCHD, 435; and Maj Gary L. Telfer, LtCol Lane Rogers, and V. Keith Fleming Jr., U.S. Marines in Vietnam: Fighting the North Vietnamese, 1967 (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1984), 245.

- This was a Civilian Irregular Defense Group (CIDG) unit. These forces included ethnic minority groups, mostly Montagnard tribesmen from the Central Highlands, who teamed with U.S. Green Berets to screen NVA incursion routes and strike vulnerable enemy forces. III MAF Command Chronology, March 1967 (Quantico, VA: MCHD), 22.

- Telfer, Rogers, and Fleming, Fighting the North Vietnamese 1967, 109–11; Miscellaneous File, Named Operations, Cochise Folder, COLL/5348, Vietnam War Command Chronologies, MCHD, 64, says 154 KIA; and III MAF Command Chronology, August 1967 (Quantico, VA: MCHD), 12–13.

- In Operation Swift, Marine Corps and ARVN forces encountered elements of the 1st Viet Cong as well as the 3d and 21st NVA Regiments. Total enemy losses indicated as 501 KIA in “I CTZ Summary 2–11 September 1967 Operation Swift,” Miscellaneous File, Named Operations Folder, Op File–Op Swift–4–15 September 1967, COLL/5348, Vietnam War Command Chronologies, MCHD, 5; and III MAF Command Chronology, September 1967 (Quantico, VA: MCHD), 11, says 571 enemy KIA and 8 prisoners of war. Evenly divided among the three regiments, this figure would have equated to 190 1st Viet Cong KIA (the number does not include 529 “probable” enemy KIA and 58 Viet Cong suspects detained). Telfer, Rogers, and Fleming, Fighting the North Vietnamese, 1967, 111–19.

- III MAF Command Chronology, September 1968 (Quantico, VA: MCHD), 28.

- See, for example, III MAF Periodic Intelligence Report 13, 3 May 1966, January–June Intelligence Reports, 6; III MAF Periodic Intelligence Report 28, 16 August 1966, June–October Intelligence Reports, A-8; III MAF Periodic Intelligence Report 39, 30 October 1966, October–December Intelligence Reports, A-6, A-13; III MAF Periodic Intelligence Report 42, 20 November 1966, October–December Intelligence Reports, A-2–A-4; and III MAF Periodic Intelligence Report 13, 2 April 1967, Intelligence Reports, February–April 1967, B-2, all COLL/5348, Vietnam War Command Chronologies, MCHD.

- U.S. forces suffered five wounded for every one combatant killed in Vietnam. Thayer, War without Fronts, 110. USMACV, however, (for unknown reasons) applied a lesser ratio of 1:1.5 for killed to wounded in estimating NVA/Viet Cong losses. Phillip B. Davidson, Secrets of the Vietnam War (Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1990), 81.

- Pribbenow, Victory in Vietnam, 392.

- Translation Branch, USMACV J2, Interrogation of Rallier Report #180665, 24 September 1965, Record Group 472, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), College Park, MD, 2–3; and excerpt from a declassified Top Secret Commander-in-Chief, Pacific (CINCPAC) message to the JCS dated 24 August 1965, CINCPAC Weekly Report, “The Situation in South Vietnam,” Intelligence and Reporting Subcommittee of the Interagency Vietnam Coordinating Committee, 22 September 1965, personal collection of Otto Lehrack, 11. Otto Lehrack shared copies of both documents with the author in the spring of 2000. He located these papers in research done on the Starlite battle. The Rallier Report was subsequently cited in his 2004 book The First Battle.

- Shulimson and Johnson, The Landing and the Buildup, 1965, 99.

- Col Nguyen Van Ngoc, NVA (Ret), Quang Ngai City, SRVN, interview with author, 9 April 2000, hereafter Van Ngoc interview. The author met Col Van Ngoc in 2000 when he accompanied a group of American students from the Marine Corps Staff College walking the Starlite battlefield. Col Van Ngoc participated in that fight as a young man. Only fragmentary notes from those conversations remain, with much of his doubtless intriguing personal story and his role in Starlite and subsequent battles lost to history.

- III MAF Periodic Intelligence Report 22, 4 June 1967, April–June 1967, COLL/5348, Vietnam War Command Chronologies, MCHD, C-2; and III MAF Periodic Intelligence Report 27, 9 July 1967, June–July 1967, COLL/5348, Vietnam War Command Chronologies, MCHD, B-3.

- Fleet Marine Force, Pacific, Operations of U.S. Marine Forces Vietnam, December 1968 and 1968 Summary, COLL/5348, Vietnam War Command Chronologies, MCHD, 42. In the III Corps region, 70 percent of the soldiers in Viet Cong units were North Vietnamese by June 1968. Mark W. Woodruff, Unheralded Victory: The Defeat of the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese Army, 1961–1973 (New York: Ballantine Books, 2005), 77. By 1969, two-thirds of all Communist troops in South Vietnam were North Vietnamese; that ratio reached 80 percent by 1972. Thayer, War without Fronts, 32. The official North Vietnamese history of its army carries the 1st Viet Cong Regiment as a NVA unit, subordinate to the 2d NVA Infantry Division. Pribbenow, Victory in Vietnam, 112, 128, 135, 142, 144–45, 156–58, 160, 179, 202, 272, 294, 386, 392.

- Lanning and Cragg, Inside the VC and the NVA, 37–64; Van Ngoc interview; Translation Branch, USMACV J2, Log no 9-161-65, Interrogation of Rallier Report, Control #180665, 24 September 1965, RG 472, NARA, 1–2; and Translation Branch, USMACV J2, Log #8-459-65, Control #1798-65, RG 472, NARA, 1–5.

- Van Ngoc interview. The colonel claimed the local peasants provided willing support to the regiment. For a countervailing assessment, see Lanning and Cragg, Inside the VC and the NVA, 125–33; and the Rallier Reports summarized below.

- Wilkins, Grab Their Belts to Fight Them, 214; and Lanning and Cragg, Inside the VC and the NVA, 44.

- “Survey of 1966 Tet/Chieu Hoi Returnees,” 1967 Tet, Chieu Hoi Campaign Plan, enclosure 1 on Psyops, III MAF Command Chronology, January 1967 (Quantico, VA: MCHD), 80–89.

- See for example, III MAF Periodic Intelligence Report 44, 4 December 1966, October–December 1966, B-2 to B-3; III MAF Periodic Intelligence Report 45, 11 December 1966, October–December Intelligence Reports, B-1 to B-2; III MAF Periodic Intelligence Report 3, 22 January 1967, January–February 1967, B-1; and III MAF Periodic Intelligence Report 9, 5 March 1967, February–April 1967, C-1 to C-2, all COLL/5348, Vietnam War Command Chronologies, MCHD.

- III MAF Periodic Intelligence Report 11, 19 March 1967, February–April 1967, COLL/5348, Vietnam War Command Chronologies, MCHD, B-1–B-2.

- The wartime debate between USMACV and CIA/State Department intelligence analysts was never fully resolved. A truce of sorts ensued in the fall of 1967, when the agencies settled on a new compromise strength figure for the contested categories. These included the Viet Cong Administrative Services and Irregulars composed of the political infrastructure, guerrillas, self-defense forces (active in Viet Cong controlled locales), and secret self-defense forces (unarmed old men, women, and children who gathered information for the Viet Cong in RVN-controlled areas). It took two years for the allied intelligence effort to begin to understand this component of the intelligence puzzle. For the background of this divisive conflict among the nation’s intelligence agencies that later spilled over into the Westmoreland vs. CBS libel lawsuit, see Davidson, Secrets of the Vietnam War, chaps. 2 and 3, for the USMACV defense and Harold P. Ford, CIA and the Vietnam Policymakers: Three Episodes, 1962–1968 (Washington, DC: History Staff, Center for the Study of Intelligence, CIA, 1998), ep. 3, for the CIA challenge. The most recent, comprehensive, and credible analysis of the intelligence arguments over the 1964–69 enemy order of battle is found in Edwin E. Moïse, The Myths of Tet: The Most Misunderstood Event of the Vietnam War (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2017), https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1x07zgd. Moise concludes that USMACV senior leaders did, in fact, purposely limit the estimated numbers of enemy insurgents to buttress the Johnson administration’s arguments that the war was being won. The important point here is that the Viet Cong militia forces in I Corps totaled more than division size in strength while its supporting components equated to three divisions’ worth of personnel. In short, the level of armed and unarmed opposition, not even counting NVA and Viet Cong Main/Local Force units, was very high in the III MAF sector.

- Richard A. Hunt, Pacification: The American Struggle for Vietnam’s Hearts and Minds (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1995), 175, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429498510.

- For contrasting critiques of allied air and naval strategy in the Vietnam War, see Adm U. S. G. Sharp, Strategy for Defeat: Vietnam in Retrospect (San Rafael, CA: Presidio Press, 1978); and Mark Clodfelter, The Limits of Air Power: The American Bombing of North Vietnam (New York: Free Press, 1989).

- Gen William C. Westmoreland, A Soldier Reports (New York: Dell Publishing, 1976), 197–99.

- Andrew F. Krepinevich Jr., The Army and Vietnam (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986), argues that the war was lost because the U.S. Army paid insufficient attention to counterinsurgency operations. For arguments on the efficacy of post-Tet 1968 pacification efforts, see Lewis Sorley, A Better War: The Unexamined Victories and Final Tragedy of America’s Last Years in Vietnam (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1999); and William Colby and James McCargar, Lost Victory: A Firsthand Account of America’s Sixteen-Year Involvement in Vietnam (Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1989). Historian Gregory A. Daddis rejects the Sorley/Colby and McCargar thesis, contending instead that allied pacification was a doomed effort. Gregory A. Daddis, Withdrawal: Reassessing America’s Final Years in Vietnam (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017).

- The argument for blocking the Ho Chi Minh Trail with allied ground forces is elaborated in Harry G. Summers Jr., On Strategy: A Critical Analysis of the Vietnam War (New York: Dell Publishing, 1984), 165–73.

- Carl von Clausewitz, On War, ed. and trans. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984), 485–87, 595–97.

- The author is indebted to Dr. Thomas A. Marks, head of the War and Conflict Studies Department at the College of International Security Affairs, National Defense University, Washington, DC, for these insights. See Thomas A. Marks, Maoist Insurgency Since Vietnam (London: Frank Cass, 1996) for an insightful analysis of Communist political and military strategy in five post-Vietnam cases.

- Mark Moyar, Phoenix and the Birds of Prey: Counterinsurgency and Counterterrorism in Vietnam (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 51–55; and Hunt, Pacification, 234–51.

- Free world was a term commonly used at the time to describe anti-Communist forces supporting South Vietnam. The phrase is descriptive, not ideological, in intent. While 1960s-era South Vietnam, South Korea, the Philippines, and even the United States were not without fault if judged by contemporary ideals of representative government, accountability, or respect for civil rights, the allies certainly merited the free world title far more than their Communist rivals in the Soviet Union, China, and North Vietnam.

- U.S. forces were criticized during and after the war for inflated body counts based on inaccurate or unavailable information as well as driving up the numbers by including losses among (or even targeting) innocent civilians. Hanoi admitted after the conflict that its total military losses were roughly twice the 550,000 estimated by U.S. authorities. Woodruff, Unheralded Victory, 215, 217. Historian Guenter Lewy devotes half of his work on the war to a consideration of the war crime charge. He concludes that U.S. tactics in Vietnam did not violate international law, seek to destroy the civilian population as a matter of deliberate policy, or generate civilian casualties at rates disproportionate to other twentieth-century wars. Guenter Lewy, America in Vietnam (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978), 305.

- Marines suffered 29,190 wounded during the 1965–67 period. Thirty-one percent of those wounds were caused by indirect fire. Mines and booby traps produced 28 percent of the casualties, while bullets were responsible for 27 percent. L. A. Palinkas and P. Coben, Combat Casualties Among U.S. Marine Corps Personnel in Vietnam, 1964–1972 (San Diego, CA: Naval Health Research Center, 1985), 6, 9. In Vietnam, the Marine Corps lost 508 dead in 1965, 1,862 in 1966, and 3,786 in 1967; 1968 was the bloodiest year, with 5,047 dead. “Marine Vietnam Casualties from the ‘CACF’ List,” statistics compiled by Marvin Clement from the DOD Combat Area Casualty File, 27 November 2000, Marzone.com. These numbers do not reflect losses by ARVN, U.S. Army, U.S. Navy, U.S. Air Force, and ROK Marine forces stationed in I Corps. For a sense of U.S. casualties by region from January 1967 to December 1972, see Thayer, War without Fronts, 116. More than half (53 percent) of American combat deaths during this period occurred in I Corps. The three provinces in which the 1st Viet Cong Regiment operated proved the second, fourth, and seventh deadliest provinces among South Vietnam’s 44 provinces.