PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

The 5th Marine Regiment, known as the 5th Marines, stands as one of the most storied fighting units of Americans at war. It first saw combat in the First World War when it helped stop a German offensive at Belleau Wood in France, where thousands of Marines are buried, mute testimony of the vicious fighting. It spearheaded America’s first offensive campaign in the Pacific at Guadalcanal in 1942. It endured a brutal winter and massive Chinese Army attack at the Chosin Reservoir in Korea in 1950.

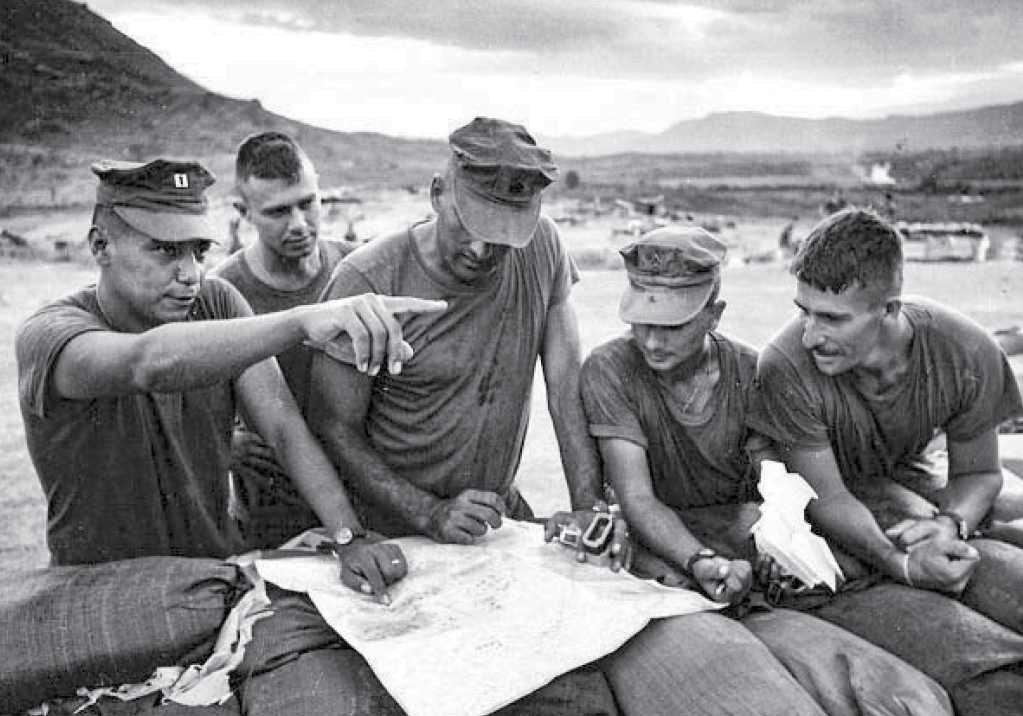

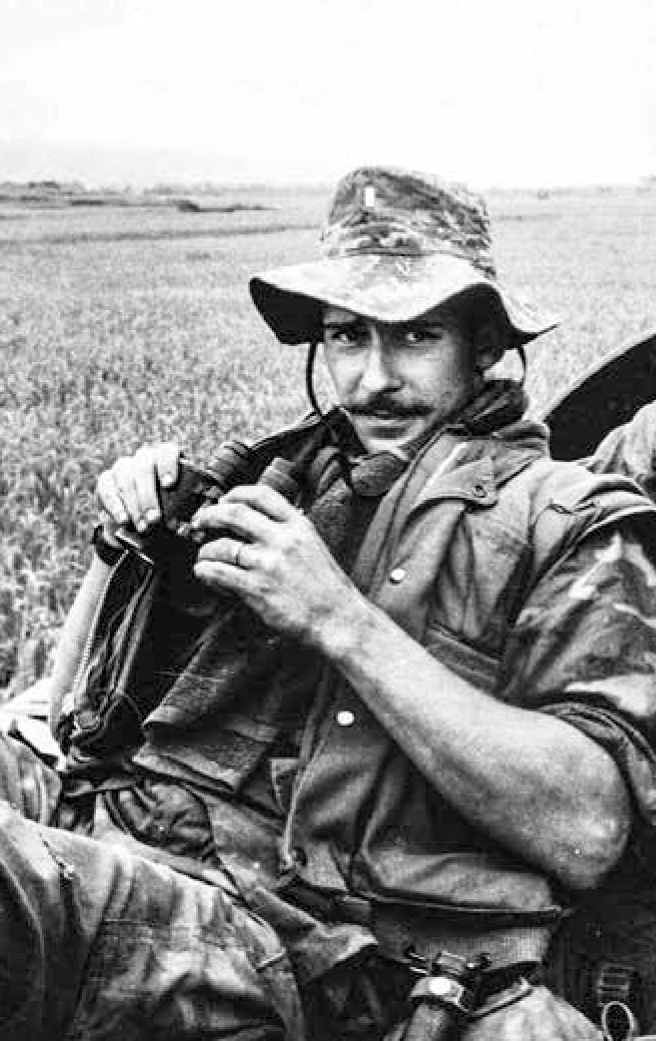

Capt Robert Poolaw with Company H staff. From left: 1stLt Clark, artillery forward observer, SSgt Frederick Pulifico, GySgt Anthony Marengo, and 1stLt Dean Andrea. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

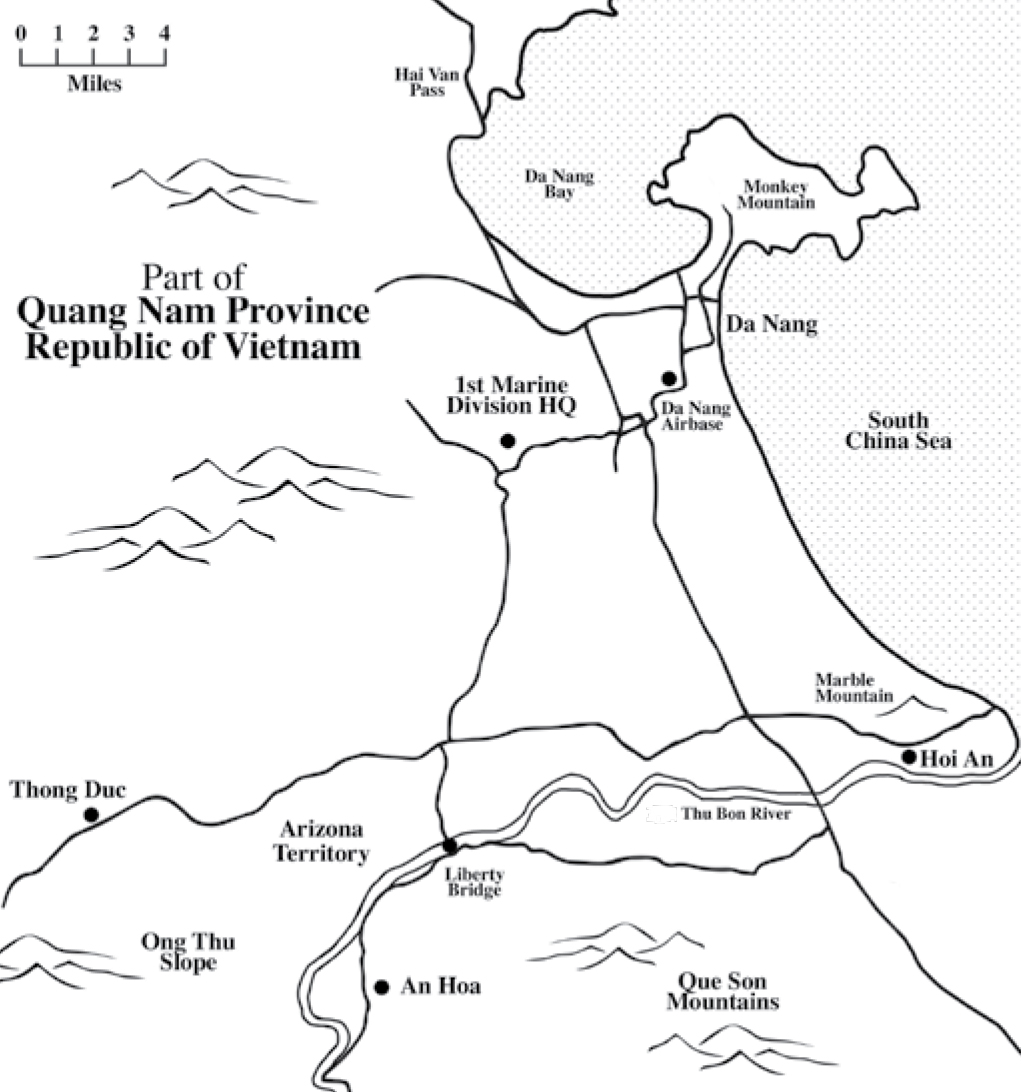

The 5th Marines spent five years in Vietnam between 1966–71, much of that time based in a small, remote village called An Hoa in the province of Quang Nam in central South Vietnam. Serving as one of three infantry regiments of the lst Marine Division (lst MarDiv), along with the 1st and 7th Marines, the 5th Marines at An Hoa were the closest Marine unit to North Vietnamese Army (NVA) units infiltrating Vietnam from Laos, home to the network of roads known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The regiment’s mission was to find, fix, and destroy the NVA as it attempted to attack Da Nang, a major city in the province and, more importantly, the Da Nang Air Base, a major NVA target and, at the time, the busiest airfield in the world.

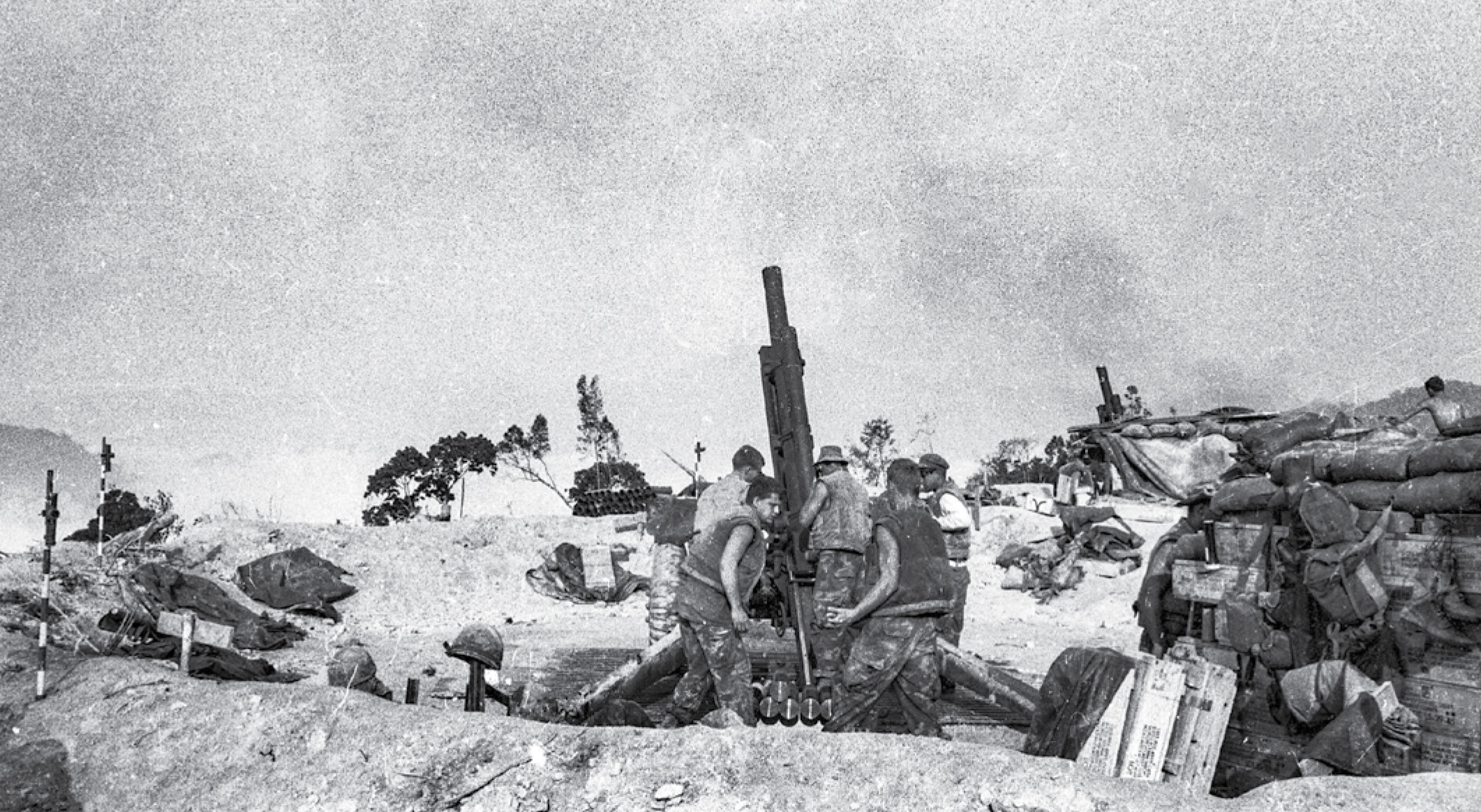

Artillery support on Operation Taylor Common from 2d Battalion, 11th Marines. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

This photographic essay focuses on the officers and enlisted members of Company H, 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, who served at An Hoa Combat Base, Quang Nam Province, Republic of Vietnam, in 1969, and is based on the author’s personal experiences with the company.1 An Hoa stood at the end of the line of friendly villages. It was virtually surrounded by villages sympathetic to South Vietnamese Communists called Viet Cong and their northern allies of the NVA who infiltrated the area from Laos to the west.

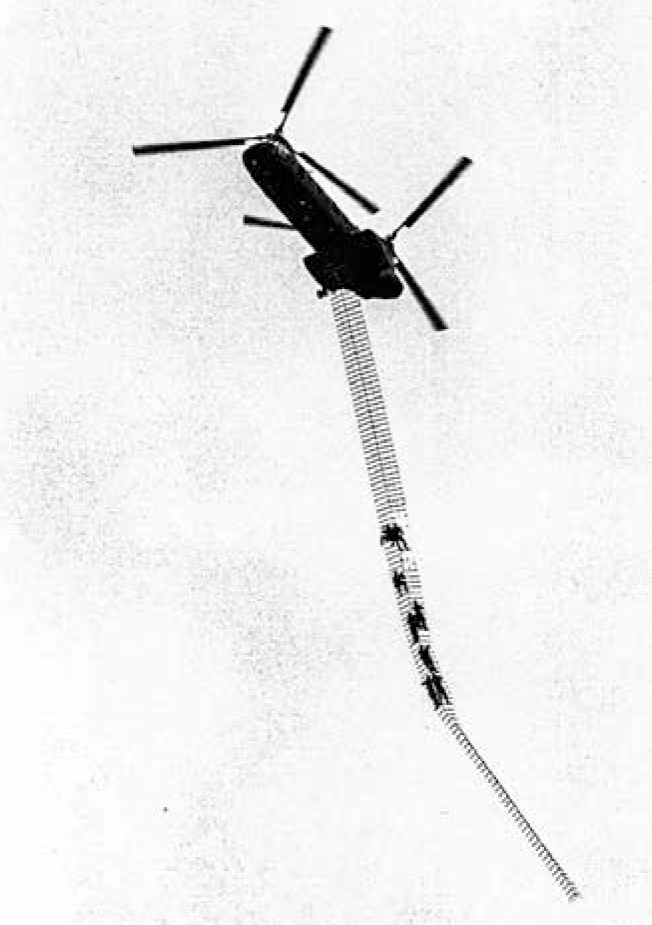

In early February, Company H was in An Hoa, the regimental headquarters, preparing for Operation Taylor Common II, a foray into the Annamite Range of mountains along the border with Laos, set to kick off a few days later. The commanding officer was Captain Ronald J. Drez of New Orleans, Louisiana, on his second combat tour in Vietnam. During the runup to the operation, the company distinguished itself on Operation Meade River. The company was transported into the mountains aboard Boeing Vertol CH-46 Sea Knight helicopters to a hilltop, where earlier Marines had rappelled from helicopters and blown down the trees. There was no room to land because of the jagged tree stumps, so Marines jumped about 10 feet into the debris and quickly set up a 360- degree perimeter without opposition of the NVA and incurring no friendly casualties. The multibattalion operation was planned to disrupt enemy infiltration from Laos nearby and destroy enemy base camps. Unfortunately, Marines were not allowed to enter Laos, an officially neutral country that had been invaded by tens of thousands of NVA to ease the movement of troops and materiel south. Cutting the Ho Chi Minh Trail could have changed the whole tenor of the war.

The first platoon-size combat patrol from the company’s tight perimeter was along a well-worn trail. The patrol ended in an ambush by a few NVA trail watchers. One Marine was wounded, requiring medical evacuation via a jungle penetrator, an enclosed capsule big enough for one person. A CH-46 helicopter lowered the penetrator through triple canopy trees, the wounded Marine was placed inside, and the penetrator was winched up. Thirty minutes later, they were in a hospital in Da Nang.

Map of part of Quang Nam Province, 1969. Map by Seth Broman, adapted by MCUP

Fire caused by an incoming NVA 107mm rocket at An Hoa. No casualties resulted. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

The gate to a Buddhist temple in An Hoa constructed out of used Marine Corps artillery containers, showing local children happy to pose and some of the civic action work done by Marines at An Hoa in 1969. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

Company H officers and gunnery sergeant in An Hoa, 1969. Back row from left: 2dLt William Vonderhaar, 2dLt John McKay, GySgt Charles Jackson, Capt Ronald J. Drez, 1stLt Barry Broman, 2dLt Homer Brookshire. Front row from left: 2dLt Jeff Steger and 2dLt James Hartneady. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

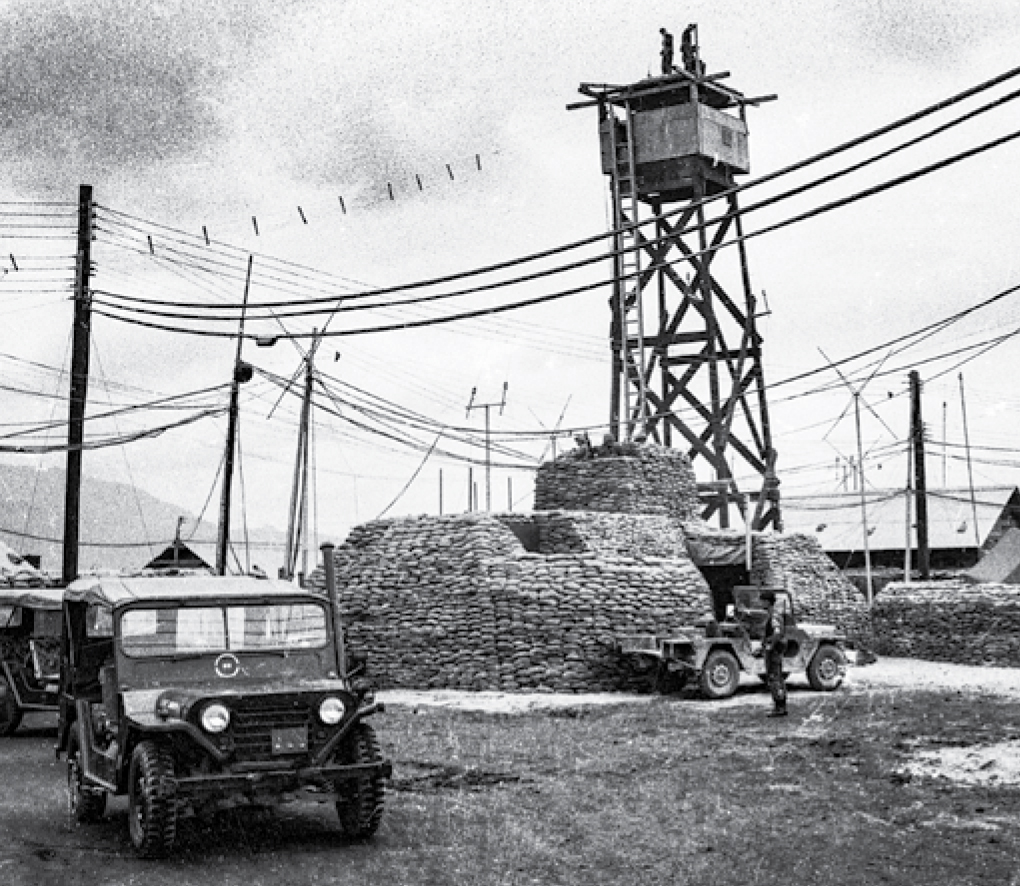

Sandbagged bunker and tower at An Hoa Combat Base, 1969. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

Young Vietnamese boys on water buffaloes watch a passing convoy of Marines near An Hoa. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

Marines in the mountains on Operation Taylor Common. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

1stLt Barry Broman, company executive officer. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

Boeing Vertol CH-46 Sea Knight helicopter at An Hoa Combat Base preparing to take an external load of supplies to be flown to 5th Marine units in the field. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

Helicopter carrying reconnaissance Marines on a mission flying over Company H in the Arizona Territory. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

2dLt Jeff Steger, left, and 1stLt Barry Broman getting ready for a breakfast of C-rations in a Vietnamese rice paddy. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

Company H in Arizona Territory, Quang Nam Province, Republic of Vietnam, 1969. At right is LCpl Al Gautschi. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

A miniature bulldozer was brought in by air to clear off the blown trees and level the hilltop so that 105mm artillery from the 2d Battalion, 11th Marines, could establish a firebase to support infantry in the mountains. At night, ambushes and listening posts were set up. Contact with the enemy was light, and the coolness of the mountain air was offset by swarms of malaria-bearing mosquitos and leeches that seemed very fond of Marine blood. After a month in the mountains, the company was back in An Hoa to shower, eat hot chow, and prepare for some tough fighting ahead in the lowlands.

The company’s next destination was a hotly contested piece of territory in Quang Nam Province located just north of the Thu Bon River and An Hoa. This was known as the Arizona Territory, a collection of villages that supported local Viet Cong. For years, 5th Marine units had crossed and recrossed this inhospitable zone, which straddled a main infiltration route to Da Nang. In addition to enemy forces, the territory was heavily booby trapped, the major cause of Marine casualties. There were no local fighters of military age to be seen in the Arizona Territory except when they fired at the Marines. Every rice farmer’s hut had a bomb shelter that could also be used as a bunker against Marines. Marines entering villages found only old sullen folks with hostile eyes and young children who beseeched Marines for candy, food, and cigarettes. Marines are suckers for little kids and freely shared rations with the exception of C-ration cans, which made excellent booby traps when paired with a hand grenade and a trip wire. Marines also provided medical treatment for the civilians, including medical evacuation by helicopter for the seriously wounded.

LCpl Larry McDonald and a new Vietnamese acquaintance during an operation in the Arizona Territory. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

Wounded Marine being medically evacuated from the field near An Hoa. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

Captain Drez rotated home with Bronze Star and Purple Heart medals and went on to pursue a career as a researcher and author of military-themed books. He was replaced by Captain Gary E. Brown, who was soon transferred to work in the Combined Action Platoon (CAP) program, which paired Marine squads with local-force militia for the defense of villages.2 For much of the time the company was in the Arizona Territory, Captain William C. Fite III was the commanding officer. Fite had served as an advisor to the South Vietnamese Marines on his first tour and was a savvy and experienced officer.3 A newly assigned officer, Second Lieutenant Theodore R. Vivalacqua, a U.S. Naval Academy graduate, was later killed in action leading an assault in the territory.4 The company went to great lengths to minimize friendly losses by relying on supporting arms, notably artillery and close air support. Most casualties were caused by booby traps. Aggressive patrolling for the enemy paid off. On one occasion, the 1st and 2d Battalions fixed and engaged an NVA regiment in the Arizona Territory heading for Da Nang with heavy air and artillery support. The Marines sustained few casualties in the sharp action that destroyed the regiment. Both battalions received a Meritorious Unit Citation for that lopsided victory.

In the Spring of 1969, an NVA sapper unit attacked the artillery of the 2d Battalion, 11th Marines, at An Hoa not far from the 2d Battalion, 5th Marines’, cantonment. All units on the perimeter raced to respond. The few Marines of Company H in the rear, many of them two-time recipients of the Purple Heart medal, manned defensive bunkers, with machine guns behind barbed wire and a minefield waiting for the enemy to attack. Intense ground fire erupted at the artillery wire. All but one of the NVA sappers were killed in the failed attack, and in the morning all sector commanders were convoked for a meeting at the attack site. The sole NVA survivor of the attack cooperated fully in showing how they cut their way through the extensive barbed wire defenses of the Marines. Stripped to his skivvies and armed only with a wire cutter, the youthful enemy moved quickly and quietly through the wire, a sobering experience for the spectators.

Easter services observed in the Arizona Territory, 1969. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

McDonnell-Douglas F-4 Phantom II dropping napalm in close air support. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

Bomb strike near An Hoa. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

Corpsman attends to wounded Vietnamese civilians during operations near An Hoa. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

Captured NVA sapper demonstrating how he cut his way through defensive positions at An Hoa. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

Marines of Company H, 5th Marines, passing through elephant grass during an operation on Go Noi Island, an enemy stronghold 16 kilometers southwest of Da Nang. Passage was made easier by following the path made by a tank. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

Easter Day 1969 was quiet in the Arizona Territory as the battalion chaplain was flown into Company H’s position to perform Easter services. There must be some truth about there being no atheists in foxholes as everyone wanted to attend the service.5 Only two volunteers stepped forward to man machine guns on the perimeter. The services were held without incident. The sound of hymns wafting over the rice paddies must have sounded strange to the listening Viet Cong nearby.

When a Marine tripped a booby trap, it was common practice to call for a Marine helicopter to take the wounded for medical treatment in Da Nang only a few minutes away by chopper, but one day no helicopter was available to evacuate an injured Marine; all Marine air assets were employed elsewhere. The injured Marine was bleeding out and Captain Fite got on the radio personally pleading for a medevac helicopter. Suddenly, a voice broke in on the emergency frequency. It was an Army helicopter pilot in the area who overheard the call for a medevac. He volunteered to come in for the wounded man and when his chopper approached, the Marines popped a smoke grenade. The Army helicopter landed and the young warrant officer pilot saved the life of a Marine.

A Marine infantry company in the field was fortunate if it included a Marine with hunting skills among them, such as Lance Corporal Cletus Foote, a soft-spoken Hidatsa from the Siouan people in North Dakota. Foote was at home in the bush and did his job well. He liked to walk point, alert for booby traps or ambushes. It was a dangerous job, but he relished danger. On a company-size sweep in the Arizona Territory one day, Foote walked point. The company was spread out in good order, carefully looking for the elusive enemy, and in the words of poet Robert W. Service, “dog-dirty, and loaded for bear.”6 Suddenly, Foote raised an arm and the company stopped. He was kneeling in a bamboo tree line.

PFC Dennis Mobray, Company H unit diary clerk, sleeping at company command post in the field. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

LCpl Ernst Woodruff, a machine gunner in Company H, with his damaged Zippo lighter that was hit by shrapnel. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

From left: 1stLt Barry Broman, Capt Robert W. Poolaw, and GySgt Anthony H. Marengo in the field near An Hoa. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

South Vietnamese president Nguyen Van Thieu visiting An Hoa Combat Base in February 1969. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

“What’s up, Foote?” the executive officer asked. “We are being followed,” he replied in a calm and quiet voice. “Foote, you are walking point. How can you see someone following us?” the executive officer asked. “There is a lone NVA with a pack and rifle behind us on the right rear of the company. I saw him,” Foote replied.

As the company moved ahead, Captain Fite ordered the scout-sniper team that was attached to the company to fall out in the next tree line and wait for the NVA. Two minutes later, a shot rang out; the sniper had found a target. Fite sent a Marine to check and found a dead NVA soldier with a pack and rifle more than 800 meters from the sniper. The Marine took the rifle and the company moved on. Many years later, Foote became a chief of the Hidatsa tribe on the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation in the Bakken oil field.

In a sharp firefight with NVA in well-concealed bunkers in the Arizona Territory, Lieutenant John McKay, another Naval Academy graduate, took a bullet through the head from an AK47 at point-blank range. The lieutenant had gone to the aid of a Marine who had been hit while assaulting a bunker. Captain Fite sent the executive officer (the author) to take over McKay’s platoon. Gunnery Sergeant Saima’ Auga Napoleon went with him and on the way encountered two Marines bringing McKay back, still conscious but missing an eye. His life was saved by Corporal Joseph Hatton, who killed the NVA who shot the lieutenant. A medevac/resupply chopper was landing nearby, so Napoleon carried him to the helicopter. McKay recovered, returned to active duty wearing a black patch, and eventually retired as a full colonel. Not long after, Captain Fite was seriously wounded by a mortar round and was medevaced to Da Nang. He recovered, stayed in the Corps, and retired with the rank of full colonel.

Memorial for Marines of Company H, 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, killed in action, An Hoa. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

Private First Class Dennis Mobray from Spokane, Washington, was probably the only member of Company H who craved action. He was well liked and also envied, as he was the only Marine in the company who was forbidden to go into the bush. No booby traps or malaria for Mobray. He was the company unit diary clerk and the only one trained to use the machine that recorded all the company’s administrative activities. The chagrined tow-headed teenager beseeched the first sergeant to be allowed to go into the bush and finally wore him down. Mobray flew into Arizona Territory on a resupply helicopter under orders to update everyone’s next-of-kin data, allotments of pay for family, etc. What Mobray really wanted was to get into a firefight so he could qualify for a Combat Action Ribbon (CAR), which identified him as someone who has been in combat. He was in luck. He got his firefight, got his CAR, and lived to go home to Spokane.

Lance Corporal Elton Armstrong, a machine gunner from Jamaica, also sought a souvenir from the Arizona Territory.7 He wanted a Soviet semiautomatic SKS enemy rifle, less well known than the AK47 but highly valued by Marines because they could take it home as a war souvenir.8 The rifle featured a folding aluminum bayonet and a wooden stock. During a nasty firefight involving NVA fighting from well-prepared bunkers, Armstrong assaulted a bunker firing his M60 machine gun from the hip as he advanced. Twice, Chicom (Chinese Communist) grenades were thrown at him and twice he outran them, never dropping his weapon. Armstrong continued the attack and, with the help of a few Marines, finally took the bunker. Later, when asked why he risked his life several times to take the bunker, he said, “I heard an SKS firing from the bunker and I wanted that rifle.” Armstrong’s assistant gunner was Private First Class Steve Russell, a Marine from Birmingham, Alabama. Russell and Armstrong formed a friendship that has lasted half a century. Russell still travels to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to see Armstrong, who now lives in a Veterans Administration hospital. Armstrong was not the only foreign-born Marine in the company. A German-born machine gunner, Lance Corporal Ernst Woodruff, called Woodie, was one of the company’s characters. One morning, after Woodruff had killed three NVA in an ambush, an officer called out to him as he walked into the company’s perimeter carrying his machine gun on his shoulder and sporting a peace symbol on his helmet. “Woodie,” he called. “How can you kill three men before breakfast and wear a peace symbol on your helmet?” “It is easy leutnant,” he replied. “I am [a] hypocrite.” When Lance Corporal Peter M. Nee from Cashel, County Connemara, Ireland, tripped a booby trap and was killed instantly, it hit the company hard. Everyone was taken with the wit and charm of the young Irishman, who in addition to being a fine Marine was also a poet. Many years later the author put flowers on his grave on the rugged Connemara coast of western Ireland.9

Another company commander was Captain Robert W. Poolaw, from the Kiowa Nation in Anadarko, Oklahoma. He was a quiet but tough former enlisted Marine on his second Vietnam tour. Poolaw was wounded in action while commanding Golf Company and when he recovered from his wounds, he was assigned to Company H after Captain Fite was medevaced.10 The gunnery sergeant at the time was Anthony H. Marengo from Brooklyn, New York, a veteran of numerous tours in Vietnam and a recipient of Silver Star, Bronze Star, and three Purple Heart medals.11 In a departure from the company’s normal patrolling in search of the enemy, it was ordered to assist a Vietnamese Regional Force (RF) militia unit at a hilltop outpost near an NVA infiltration route. Acting on intelligence that the NVA were coming, Company H was sent to augment the poorly armed RF under the command of an old warrant officer who had served in the French colonial army in Vietnam a generation earlier. They welcomed the Marines warmly. Company H quickly set up with their Vietnamese allies’ defensive position and brought along a new weapon, an AN-M8 CS (carbon monosulfide) or tear gas pack. The pack could launch 40 nonlethal CS grenades against an assaulting enemy. It was the first time Company H had employed the weapon.

Night fell and the Marines embedded with the Vietnamese militia prepared for a fight. Before long, NVA were spotted moving down the mountainside with the help of a Starlight scope night-vision device. The company’s 60mm mortar set up and prepared high-explosive and illumination rounds for instant deployment. Machine guns were placed to afford interlocking fields of fire. The listening post was called in as the North Vietnamese crept closer. Captain 11 See “Anthony Marengo,” Hall of Valor Project, accessed 3 June 2020; and United States Oral History Collection, Vietnam Interviews, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA. Poolaw thought this would be a good chance to test the new AN-M8 gas pack. It all depended on one thing: the wind. If the wind was against the Marines, there was no way they would fire the AN-M8 and let the gas blow into their own positions. Fortunately, the wind was in their favor and when the NVA moved in close, they fired the gas pack. Forty nonlethal gas grenades descended into the path of the enemy as the Marines fired an illumination round from the mortar to light up the battlefield, then the Marines and the RF opened fire. The fight did not last long. The NVA were taken completely by surprise and ran aimlessly trying to get away from the CS gas. As they were cut down by rifle and machine-gun fire, the North Vietnamese survivors quickly retreated into the jungle, leaving more than a dozen dead and their weapons behind. The captured weapons were left with the militia, which could claim a bounty of $75 for each AK47. Company H returned to An Hoa with no friendly casualties. Captain Poolaw eventually retired from the Marine Corps and returned to Oklahoma. Gunnery Sergeant Marengo retired from the Corps as a sergeant major and immediately joined the U.S. Secret Service, where he made a second distinguished career in the service of the United States.

• 1775 •

ENDNOTES

- For more on the U.S. Marine Corps in Vietnam during this period, see Charles R. Smith, U.S. Marines in Vietnam: High Mobility and Standdown, 1969 (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1988).

- For more on the CAP Program, see MSgt Ronald E. Hayes II (Ret), Combined Action: U.S. Marines Fighting a Different War, August 1965 to September 1970 (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps History Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 2019).

- For more on Marine advisors, see Col Andrew R. Finlayson (Ret), Marine Advisors with the Vietnamese Provincial Reconnaissance Units, 1966–1970 (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps History Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 2009); and Charles D. Melson and Wanda J. Renfrow, comp. and eds., Marine Advisors with the Vietnamese Marine Corps: Selected Documents Prepared by the U.S. Marine Advisory Unit, Naval Advisory Group (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps History Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 2009).

- Vivalacqua would receive the Silver Star (posthumously) for his service during this action. See “Theodore R. Vivalacqua,” Hall of Valor Project, accessed 3 June 2020.

- There has long been debate about the origin of the phrase “there are no atheists in foxholes.” See “Religion: Atheists & Foxholes,” Time Magazine, 18 June 1945.

- Robert W. Service, “The Shooting of Dan McGrew” in his collection The Songs of a Sourdough, author’s ed. (Toronto, Canada: William Briggs, 1907).

- Armstrong was awarded a Silver Star for this action. See “Elton Armstrong,” Hall of Valor Project, accessed 3 June 2020.

- The SKS was designed in 1943 by Sergei Gavrilovich Simonov. Its complete designation, SKS-45, is an initialism for Samozaryadny Karabin sistemy Simonova, 1945.

- Brian McGinn, “An Irishman’s Diary,” Irish Times (Dublin), 29 May 2000.

- Valor in Black and White: War Stories of Horace Poolaw,” Smithsonian, video, 1:27:8, 11 November 2016.