PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

First Lieutenant Carl Gardner, editor of Leatherneck, asked in an editorial in March 1927, “Why shouldn’t the Marine Corps Have a Museum of its own?” He argued that the Marine Corps had existed for 150 years but had no place to exhibit the material objects that told the Corps’ story. Flags, weapons, ordnance, uniforms, and pictures, among other trophies, were scattered across the posts of the Corps or in the hands of individuals where few people saw them. If gathered together in one place, the objects could tell the Service’s story to a greater audience, Gardner reasoned. He had a point. The efforts by the Marine Corps to establish a quality museum of its own is a story of an evolving process through trial and error and incremental progress for six decades. In the mid-1990s, the process adopted a revolutionary approach that culminated in 2006 with the opening of the National Museum of the Marine Corps (NMMC). For much of the past 85 years, Marine Corps historians played significant roles in these efforts.2

The other military Services had established museums during the nineteenth century, but due to the size of the Corps and operational activities, Marines showed no real interest in following suit.3 The U.S. Army established a museum at West Point, New York, in 1854, though a collection of historical objects had commenced years earlier.4 The U.S. Naval Academy had exhibited a collection of flags since 1849.5 Meanwhile, the U.S. Navy’s museum at the Washington Navy Yard had been in operation since 1865.6 Other organizations borrowed artifacts from the Marine Corps for exhibitions. Marine objects from World War I were exhibited at the Smithsonian Institution in 1921 and in Philadelphia at the 1926 Sesquicentennial Exposition, but it was not until the 1930s that Marine leaders acted to start the process of creating a museum at Quantico and a few other locations to exhibit their material heritage.7

In 1933, the Commandant of the Marine Corps, Major General Ben H. Fuller, issued Circular Letter No. 133 directing the commanding general of Marine Barracks Quantico, to establish a trophy room to exhibit historical objects and photographs. At the same time, the commanding officer of Marine Barracks Washington, DC, borrowed objects from the Historical Branch at Headquarters Marine Corps to exhibit artifacts in the Sousa Band Hall.8 In December 1933, General Fuller responded to a request from the commandant of the Washington Navy Yard for Marine Corps trophies to be included in a future Navy Yard Museum, stating that any trophies in excess of the needs of the two existing Marine museums at Quantico and Marine Barracks Washington, DC, would be available for loan to the Navy Yard Museum; however, no objects were loaned.9 Later, a writer at the Marine Corps Gazette recommended a museum be built at Quantico based on the design of Tun Tavern in Philadelphia, similar to the exhibit at the 1926 Philadelphia Exposition, but nothing came of this idea.10

An organized museum came to life at Quantico in 1940. On 2 October 1940, Commandant Major General Thomas Holcomb issued Circular Letter No. 391, ordering that a museum be established at Quantico on the second floor of the newly constructed Quantico Recreation Building (now Little Hall). The museum was intended to foster esprit de corps, build and maintain traditions, and preserve objects of lasting historical and sentimental interest to the Marine Corps, words similar to those included in the mission statement of the NMMC today. Holcomb assigned Marine Corps historian Lieutenant Colonel Clyde H. Metcalf to be the museum’s curator. Holcomb’s letter contained much more detail and thought regarding historical objects and museum operations for the time than had Circular Letter No. 133.11 Large cases exhibited flags, weapons, trophies, medals, and equipment, and mannequins wearing original uniforms. Exhibits were rotated to retain interest, objects not on exhibit were secured in steel lockers, and donors were required to contact the curator before sending objects, all procedures still used by the NMMC staff today. Unfortunately, the museum’s initial success did not last long.12

Metcalf was transferred overseas in late 1942 and the custodial responsibility of the museum fell to the post recreation officer. By 1945, the head of the Historical Division, Colonel John Potts, wrote a memo to Commandant General Alexander Archer Vandegrift addressing a number of museum concerns, two of which were that Quantico was the wrong location for a museum due to the lack of public access and his recommendation to assign an older noncommissioned officer or warrant officer to oversee preservation, inventory, and care of the objects. The Commandant approved the appointment of First Sergeant Lowrey A. Weed to curate the museum. Weed made headway in the stewardship of the collection by using the Smithsonian Institution’s recordkeeping process, until he transferred in 1946. The post recreation officer once again became the custodian. Nothing came of the issue of public access to the Quantico museum location, though ease of access played a part in the selection of the site of the new NMMC.13 John Elliott, a young Marine who reported to Quantico in 1946, remarked that when he visited the museum, there were few Marines in sight, though the exhibits looked impressive.14

The museum’s story took a turn for the better in the early 1950s, when Commandant General Lemuel C. Shepherd Jr. reached out to Marine Reservist John H. Magruder III to return to active duty and oversee the Quantico museum. Magruder recruited two active duty assistants to his staff, historian Major David E. Schwulst as curator and Master Sergeant George McGarry, an ordnance expert and jack of all trades. Magruder had experience organizing exhibits about Marines at the Smithsonian Institution’s Hall of Naval History. Magruder’s staff was small in number—approximately five people to handle the curatorial, administrative, exhibits, and any other tasks that needed to be accomplished.15

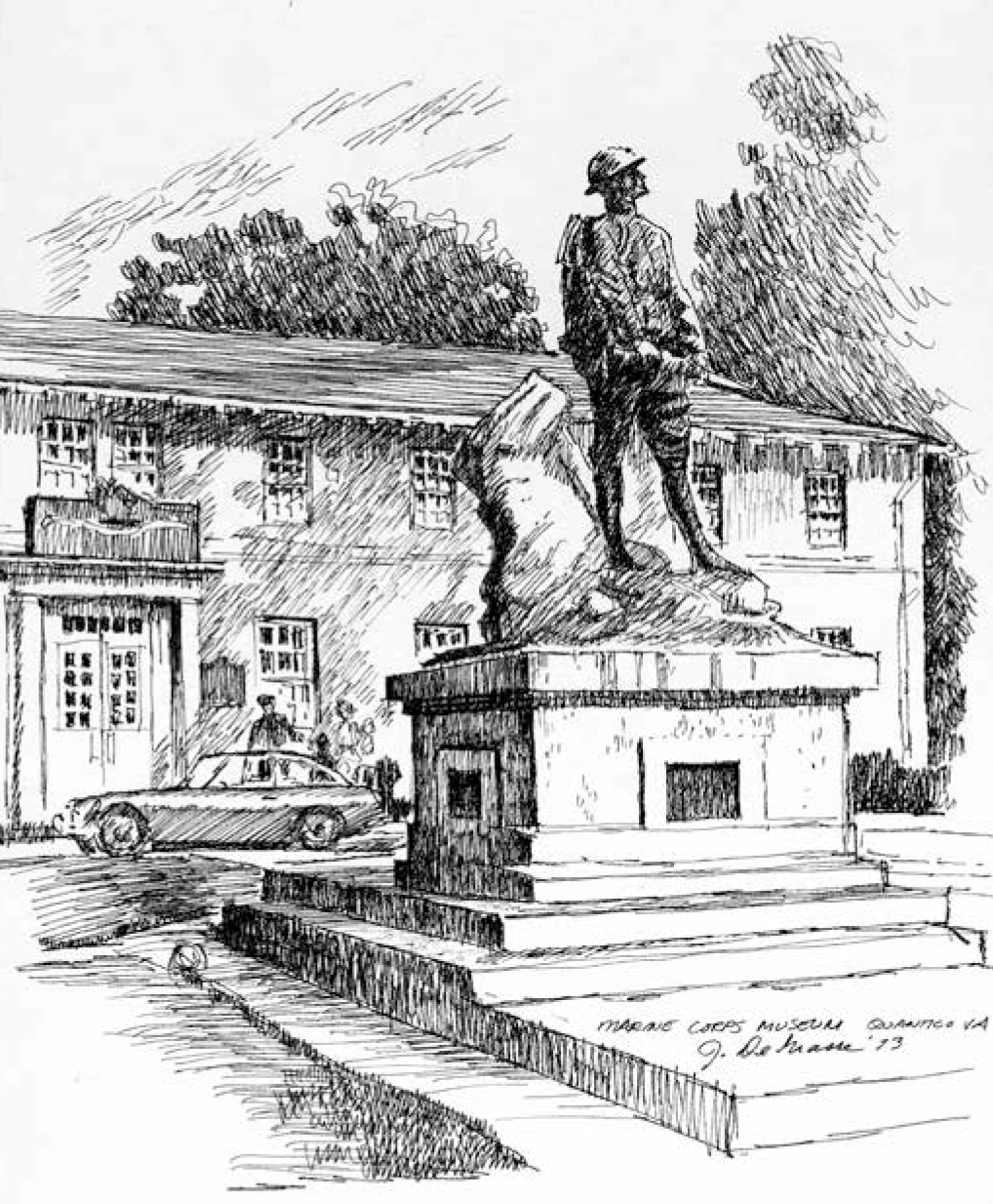

MSgt John C. DeGrasse (Ret), former art director for Leatherneck magazine, sketched this scene of Building 1019, the Marine Corps Museum, with the bronze statue “Iron Mike” in front in 1973. Marine Corps Combat Art Collection, 2012.1027.11

Artifacts on exhibit in Building 1019, August 1965. Photo by NMMC staff

In 1960, Magruder moved the museum to Building 1019, adjacent to Little Hall. The new museum building was small but their own, and the staff were proud of their work. In January 1962, Magruder wrote a memorandum to the head of the Historical Branch, G-3, that during a visit to the Marine Corps Museum by two U.S. Army general officers the previous December, the visitors stated that the West Point Museum could learn something from the Marines. Magruder continued: “The thing that gives me particular satisfaction is the knowledge that West Point spent several million dollars renovating their Museum about four years ago while we have operated on a mere fraction of their budget and with a staff that is considerably smaller.”16

Magruder’s accomplishments during his tenure as director of the museum were many, including his work to open additional buildings to exhibit the aviation history of the Corps and future plans to exhibit the stories of Marines in Vietnam; his comments on a draft of Marine Corps Order 4010 on the preservation of historical material; increasing and diversifying the museum staff; and designing the windows in the Marine Memorial Chapel at Quantico and the Marine window at the Arlington Cemetery Chapel. Three other initiatives that were considered on Magruder’s watch but never materialized include Magruder leading a Smithsonian Institution effort to plan and build an Armed Forces Museum in 1965 near Washington, DC, Magruder’s plan for a fortress-like museum on the parade field near Lejeune Hall in 1966, and Felix de Weldon’s proposal to the Commandant to construct a Marine museum near the Iwo Jima War Memorial in 1967.17

Magruder retired from the Marine Corps in 1969 and died in 1972. He was a fierce proponent of the museum program while he was on active duty and in retirement and he continued to comment on museum affairs. He put the museum program on firm ground that included a larger and more professional staff than before, additional funding, greater visibility of the museum program, and influence on regulations that pertained to historical property.18

Magruder’s momentum in advancing the museum program continued, and major changes to the museum and historical program occurred during the 1970s through the 1990s. This time was a period of growth in museum staff and reorganization, movement of museum activities, acquisition of additional buildings, and the establishment of a key partner that supported the history and museums program.

Prior to 1973, there were two Marine Corps historical activities, the Historical Branch of the G-3 (Operations) at Headquarters Marine Corps and the Marine Corps Museum at Quantico functioning under the Commandant’s office. The Commandant formed the Commandant’s Advisory Committee on Marine Corps History during the 1960s that provided oversight to both activities. The committee was composed of distinguished historians and retired senior Marines who had a deep interest in the Corps’ history. The committee met annually, reviewed the programs of both the museum and historical branch and provided a report to the Commandant. Brigadier General Edwin H. Simmons, recently appointed as the director of Marine Corps History and a Marine Corps historian, proposed to the Commandant that the History Division and museum activities be combined into one organization. This consolidation was effective Octo- ber 1973 and the division was renamed as the History and Museums Division (HD) and was headquartered at Building 198 at the Washington Navy Yard.19

In 1973, the museum acquired the 1920s-era brig at Quantico, Building 2014, for the collections and museum staff offices.20 In 1976, the museum in Building 1019 closed and the art and artifacts and a few museum staff were moved to the Washington Navy Yard, where a second Marine museum opened. This museum, called the Marine Corps Museum, left Quantico with neither a museum nor trophy room for four decades, but this was not to last. The remaining Quantico museum staff, reorganized as the Museums Branch of HD, had been working on another museum activity since Magruder’s tenure that was originally an extension of the museum in Building 1019. This additional museum activity would be located in two older hangars on Brown Field near the present-day Officer Candidate School. This museum activity formally opened as the Aviation Museum in 1978.21 The exhibits showed the role of Marine aviation in World War II using a number of restored aircraft. Future plans included a Korean War hangar and an Early Years hangar depicting pre–World War II aviation history.22

In 1979, friends of the Corps and retired Marines established the Marine Corps Historical Foundation (MCHF), a nonprofit organization dedicated to the purpose of supporting the official historical effort of the Corps. The foundation supported HD at the Navy Yard commencing in 1983, maintained offices in Building 58, and filled some of the void left by the abolishment of the Commandant’s Advisory Committee on Marine Corps History. The foundation would prove to be critical to the museum program in the years ahead.23

In 1985, Brigadier General Simmons ordered that the Aviation Museum be renamed the Marine Corps Air-Ground Museum (MCAGM) and the aviation-focused exhibits were reworked to show the operations of the air-ground team in combat. A number of museum staff relocated from the Navy Yard to the MCAGM.24 The unheated and unair-conditioned hangars never attracted more than 25,000 visitors each year during the eight-month open season. The Restorations Section, consisting of Marines, civil servants, and volunteers, occupied a portion of Larson Gymnasium and worked wonders in keeping the aircraft and rolling stock in good condition for exhibition.

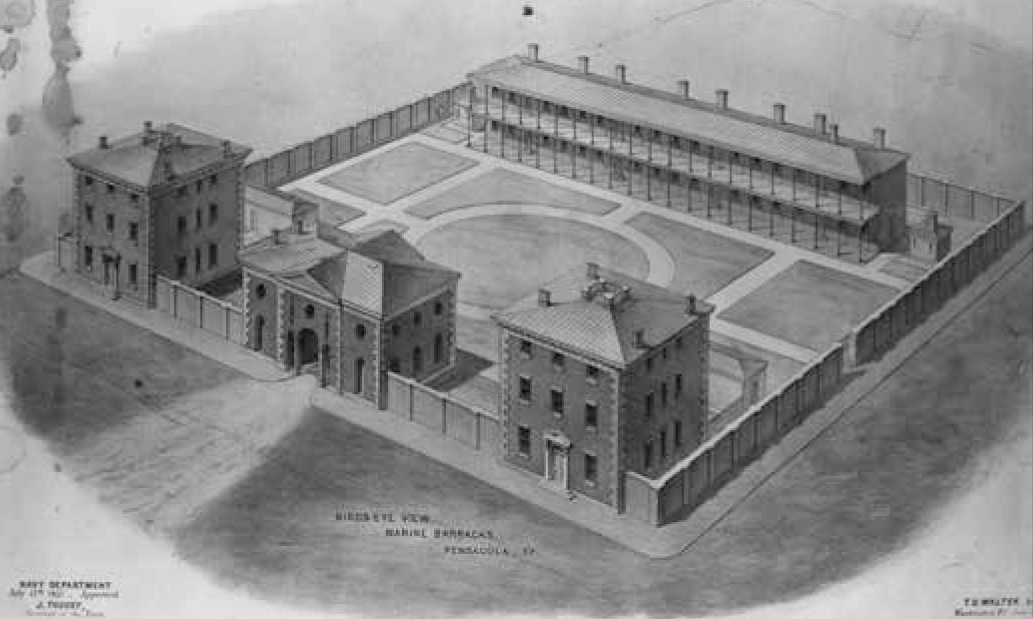

Col John Magruder’s Quantico Museum building concept was based on the nineteenth-century fortress-style layout of the Marine barracks in Pensacola, FL. The distinctive entrance gate provides the central motif for Magruder’s museum. Photo by NMMC staff

Goodyear FG-1 Corsair still on exhibit in 2003 in the then-closed Marine Corps Air Ground Museum’s World War II hangar. Photo by NMMC staff

The structural condition of the three hangars of the MCAGM were a continued source of comment since the early 1980s. In the spring of 1984, General Simmons suggested to Colonel Brooke Nihart (Ret), deputy director for museums, to speak with MCHF about including a new museum in the foundation’s long-range plan. During the ninth annual meeting of MCHF in November 1987, the president of the foundation, Lieutenant General George C. Axtell (Ret), stated that one foundation initiative was to erect a suitable structure at Quantico to house what has grown into a significant monument to the Marine Air-Ground Team. In December 1988, Simmons reported to the MCHF that marginal repairs were made to the hangars to include painting and reskinning the roofs.25 By 1992, the foundation and HD were considering the construction of an additional structure at the MCAGM to tell the Vietnam story. The concept was not adopted, however, in favor of a radical heritage center concept at Quantico.26 The museum staff increased gradually during the 1970s through the 1990s. A total of 12 civilian museum staff were on the rolls of HD during the mid-1970s as curators, administrators, exhibitors, and restorations specialists to operate and maintain both museums at the Navy Yard and at Quantico.27 In January 2000, the Museums Branch roster at Quantico included 12 active duty Marines and 10 federal employees.28 The Museums Branch civilian personnel strength continued to increase with an approved table of organization for the NMMC. Marines provided security, were guides for visitors, and were a living bridge connecting the exhibits of the past to the present Corps. Active duty Marines serve today at the NMMC in similar roles.

The Revolution Begins and Continues

By 1995, the concept of a new heritage center at Quantico was taking center stage at MCHF meetings rather than discussing the expansion of the MCAGM. The foundation and two professional exhibits firms studied the concept of a heritage center campus containing a world-class museum at Quantico to improve stewardship of the MCAGM collections, reach a wider audience, and instill in the visitor an understand- ing of the contributions that the Marine Corps had made throughout our nation’s history and continues to do so.29 The museum program took a major leap forward when in 1999, the foundation and HD formally launched a capital campaign in support of a Marine Corps Heritage Center colocated with a National Museum at Quantico.30

The task at hand was complex. Few members of the foundation, History and Museums Division, and the U.S. Navy’s facilities construction office, Engineering Field Activities Chesapeake (EFACHES), had ever designed a museum with unique requirements from the ground up. The building design was to support the galleries and artifacts on display using privately raised funds on forested land that the federal government did not own at the time. This project included a cast of hundreds from many professions working together throughout the multiyear project while continuously coordinating their efforts.31 The degree of cooperation was high and the learning curve was steep. EFACHES assumed the role of managing the numerous multimillion dollar government contracts, including hiring the architectural and exhibits design and installation firms and conducting the environment impact study. The contracted architects, Fentress Bradburn Architects of Denver, Colorado, and exhibit designers, Christopher Chadbourne and Associates of Boston, Massachusetts, studied and experienced the history of the Corps. Their winning building and exhibits design reflected their focus. They walked the German trenches and wheat fields of Belleau Wood, entered Japanese tunnels and gun emplacements on Guam, Saipan, and Tinian, and stood atop Mount Suribachi on the exact spot where the famous flag raisings took place during World War II. They participated in boot camp activities and lived for a few days on board ship.32

The firms designing the museum translated their experiences into a distinctive structure and innovative exhibits. A second exhibits firm, Design and Production Inc. of Lorton, Virginia, turned the exhibit designs and drawings into reality. A gleaming central mast reaching 210 feet in the air at an angle reminiscent of Joseph Rosenthal’s famous photograph of the Iwo Jima flag raising, topped by a cone of glass, and encircled at its base by exhibits evokes history through the eyes of Marines. Groundbreaking for the new museum commenced in 2003 on 135 acres outside the main gate of Marine Corps Base Quantico. Locating the museum outside the base made public access easier. The museum sits astride the King’s Highway, a Colonial-era road that saw commerce, famous personalities, and military units move over it during the past three centuries.33

The project became a full-time duty for many in the History and Museums Division. The historians and Museum Branch staff joined contracted exhibits and architectural representatives on working groups. Major tasks included developing the storyline and exhibits, reviewing text, architectural and exhibit designs, selecting and preparing objects for the galleries, determining the size of the NMMC staff, projecting future budgets, drafting position descriptions and selecting candidates, reviewing videos and selecting hundreds of still photographs, participating on committees to award contracts, traveling to scheduled meetings, training the museum volunteers, and recommending opportunities in the galleries for foundation fundraising. Retired Marine and historian Colonel Joseph H. Alexander was contracted to be the principal historical writer for the Phase I text. Foundation and HD staff briefed the Assistant Commandant and senior generals of the Corps on progress and issues in a monthly executive steering committee.34

Funding was split between MCHF and the Marine Corps. The foundation raised the funds needed to build the circular structure and to oversee construction of the planned initial construction of 120,000 square feet at a cost of $60 million, hiring Jacobs Facilities Inc. to assist them and commissioning Balfour Beatty to build the structure. The foundation operated all revenue-generating activities in the museum to include a museum store, rifle range, a tavern, and a restaurant. Costs to the Marine Corps totaled $42 million for funding design, exhibitions, start-up, restoration/conservation of artifacts, and NMMC staff labor. Other spaces in the NMMC include a 95-seat theater, maintenance facilities, and offices for a portion of both the NMMC and foundation staffs.35

The NMMC as seen from one of the heritage paths near the chapel on the Heritage Center grounds. Photo by Gwenn Adams, NMMC public affairs officer

The NMMC opened on 10 November 2006 to fanfare that included President George W. Bush as the guest speaker and an estimated 10,000 attendees. In 2008, a playground was added to the grounds and a nondenominational chapel opened in 2009. The Marine Corps Heritage Foundation continues to support programs at the NMMC, including paid internships, special assistants, docent needs, and the purchase of art and artifacts for the museum collections.36

Museum Reorganization

In 2002, the Commandant directed that the History and Museums Division be moved to Quantico and as- signed to Marine Corps University (MCU). This transition included a major reorganization of the history and museums program. The elements of the division—the Historical, Support, and Museums branches—were separated. The branches at the Navy Yard shifted to Quantico by September 2005.37 In 2005, the NMMC expanded the staff of the Museums Branch and reorganized as a division within MCU. The first museum director, Lin Ezell, a curator with many years at the Smithsonian Institution, took the museum’s helm in 2005 and immediately immersed herself in the project. The museum located in Building 58 of the division’s headquarters at the Navy Yard was closed, and the art collection and all museum employees moved to Quantico.38

In June 2006, the NMMC staff consisted of 21 federal employees, 9 Marines, and approximately 150 volunteers, and in December 2006 soon after the grand opening, the staff increased to 30 civilians and 10 Marines. By July 2009, the staff grew to 41 federal employees and 18 Marines organized into nine sections: Directorate, Operations/Facilities, Curatorial Services, Art, Registrar, Restorations, Exhibits, Education, and Visitor Services.39

An Overview of the NMMC

The NMMC is the crown jewel of the Marine Corps’ museum program, which includes three command museums (one each at the Marine Corps Recruit Depots in San Diego, California, and Parris Island, South Carolina, and an aviation-themed museum at the Marine Corps Air Station, Miramar, California) and numerous historical displays at Camp Pendleton, California. The NMMC was constructed during a number of years in two phases.

Phase I Concept

The exhibit space for the NMMC, which was planned to open in 2006, is organized into seven themed galleries arrayed chronologically from 1775 through 1975, a central gallery (Leatherneck), and a Legacy Walk that total more than 60,000 square feet. Due to fiscal issues, three themed galleries of the original seven, 1775 through World War I, were delayed in opening until June 2010 (commonly called Phase 1A). The strategic approach to the design of the museum and exhibit presentation is guided by 11 core messages for the staff and visitors. The designers approached the visitor experience with a layered, complex, and engag- ing presentation for a wide audience of retired and active duty military and families and those who never served. The Marine Corps story is told through high-quality exhibits, some immersive, containing approximately 2,000 artifacts, videos, still imagery, audio, cast figures, and hands-on interactions. Scheduled public programming events and educational outreach activities within the gallery spaces provide additional impact to the story.40 The Assistant Commandant selected the initial galleries to be opened in 2006 for the living veterans who served in World War II, Korea, and Vietnam.

Leatherneck Gallery: the museum experience commences when the visitor first enters the NMMC. Leatherneck Gallery, the central gallery, evokes bearing and resolve, but also permanence and innovation. The artifacts, vignettes, testimonials, and images in this space honor the contributions of every Marine and highlight the core messages of the NMMC. Aircraft are suspended above visitors, vignettes show Marines in combat, and the multicolored terrazzo floor represents the expeditionary nature of the Marines.41

Making Marines Gallery: all Marines remember their boot camp or officer candidate experience. Visitors step inside the process used by drill instructors to transform young men and women into Marines. From the hometown recruiting station to graduation, visitors are immersed in the memorable experiences that forge recruits and officer candidates into privates and lieutenants. They get up close and personal with their own drill instructor by entering a sound booth, stepping on the yellow footprints, and trying their marksmanship skills at the M16 laser rifle range modeled on the Quantico ranges.42

Legacy Walk: this is the main hallway through the space from which visitors enter the themed galleries. On one side, the hallway contains a timeline of significant dates in U.S., world, and Marine Corps history from 1775 through 2006. More than 50 artifacts populate small exhibit cases. On the other side of the hallway, exhibit cases contain iconic artifacts of the Marines such as General Lejeune’s overseas cap worn in World War I and a three-war K-bar knife. Kiosks present narrated topical videos.43

Themed Galleries: themed galleries provide a more detailed study to a period in history for the visitor. Wall murals, photographs, oral history interviews, and dioramas deliver stories about combat operations, significant contributions to the war, individual Marines, special units, morale, and air support. The first gallery—Uncommon Valor: Marines in World War II— recalls the Marines in battle in the Pacific and holds the most important artifact in the museum’s collection: the Iwo Jima flag. Exhibits in the World War II Gallery highlight innovation in tactics, equipment, women Marines, a Montford Point exhibit focusing on racial issues, the Code Talkers, and Navy Hospital Corpsmen.44

The second themed gallery that opened in 2006 is titled Send in the Marines: The Korean War. The exhibits in this gallery include the significant Marine amphibious assault at Inchon, the subsequent fighting in urban areas and hills, an immersive exhibit at Toktong Pass during the Chosin Reservoir fighting (in which visitors feel a chill while walking through the scene), POWs, and weapons and vehicles used by the combatants.45

In the Air, on Land, and Sea: The War in Vietnam is the last themed gallery of the 2006 opening. Focusing on one of the longest wars in Marine Corps history, the Vietnam War story tells of the experiences of Marines and their allies fighting insurgents and North Vietnamese troops in both urban and rural areas. A Bell UH-1 Iroquois helicopter represents the air war. This aircraft is the helicopter piloted by Marine Captain Stephen W. Pless in action against the enemy in 1967, for which he was awarded the Medal of Honor for valor. Visitors see Marines fighting at Hue City and walk through a Boeing Vertol CH-46 Sea Knight helicopter into an immersive exhibit of Marines at Hill 881 South near Khe Sanh in 1968.46

Defending the New Republic was one of three galleries that opened in 2010. More than 90 years of almost continuous warfare are portrayed here, from the birth of the Corps in 1775 through America’s costly Civil War in 1865. The museum’s oldest artifact—an engraved powder horn used by a Marine in 1776—is exhibited here. In one scene, Corporal John F. Mackie fires on Confederate positions from a gun port on the USS Galena (1862), recreating the action that resulted in his being awarded the Medal of Honor, the first for a Marine.47

In the second gallery that opened in 2010, Global Expeditionary Force, visitors first see Sergeant Daniel J. Daly fighting a Chinese “Boxer” atop the Tartar Wall of Peking in 1900 above his exhibited two Medals of Honor. The gallery takes visitors to all points of the compass and travels from 1866 to 1916. Various artifacts are displayed that tell the stories of Marines who lived during these times in both combat and at home. The shotguns and childhood violin of Marine bandleader John Philip Sousa, the “March King,” are on exhibit.48

The third gallery that opened in 2010, Marines in World War I focuses on the Marines in France and that war’s innovations in tactics and weapons. A short film of the famous battle at Belleau Wood in June 1918 is included in the immersive space of the fight that contains cast figures, weapons, and other objects from the period. A Thomas-Morse S-4B aircraft flies overhead and a Liberty truck, restored by the NMMC staff, stands ready to take provisions to the front.49

Recent view of Leatherneck Gallery from the second deck overlook of the NMMC. Courtesy of Anthony Espree, NMMC Exhibits Branch

U.S. Marine tank and infantry assault on North Korean position in the South Korean capital of Seoul, September 1950. Courtesy of Eric Long, Smithsonian Institution

Final Phase–Phase II

In October 2012, the museum staff commenced their work on the final phase expansion. This phase adds another 117,000 square feet to the building and includes a 350-seat giant screen theater with signature film, galleries to tell the Marine story for the years 1976 to the present, the Interwar Years, an art gallery, education and staff spaces, a children’s gallery, two themed galleries—From the Sea, depicting the Marine story from 1976 to 2001 and Afghanistan and Iraq, exhibiting the history 2001 to the present—a large changing/temporary exhibit gallery, the Hall of Valor, and a sports gallery. The MCHF funded $69 million for the vertical construction and the Marine Corps $34.3 million for the exhibits. Groundbreaking occurred in 2015, and two galleries opened in 2017. The remaining galleries will open between 2019 and 2026. The architectural firm for the first phase, Fentress, returned to complete the museum’s structural design, Balfour Beatty returned to build the structure, and Eisterhold Associates of Kansas City designed the galleries.50 With Phase I lessons learned in hand, the staff reached out to the stakeholders for input—veterans, families, wounded warriors, units, active duty Marines, Headquarters staffs, senior leaders, and formal school faculty who lived the history or supported the warfighter. Objects and stories will link the new galleries to the current ones to provide visitors with a means to connect the threads of a theme through history, including hands-on stations that present real-world decision-forcing situations faced by Marines as part of their ethical and leadership challenges.51

This graphic shows the final phase gallery layout. From left, the chronology starts in 1976 and ends with Operation Iraqi Freedom on the right. Exhibits Branch, NMM

Conclusion

Lieutenant Gardner did not live to see the answer to his question, but if he had, the NMMC exceeds his expectations. The process to achieve a world class museum is not complete, as a living history museum is never finished. The staff works hard to maintain the high standard set in 2006 and continues to be relevant to the Corps. The NMMC is the first museum in the Marine Corps built to support the story within. The director is by position the curator of the Marine Corps and the Commandant’s subject matter expert on museum stewardship within the Corps. The staff members are seasoned professionals and experts in their own disciplines. Today, the NMMC is a destination for the public with 5.85 million visitors as of mid-May 2019. An average of 50,000 schoolchildren visit the museum annually and they are greeted by staff members from the corps of volunteers and educators. The museum continues to maintain its close professional relationship with the History Division.

Within six years of the museum’s opening, the American Alliance of Museums awarded NMMC its certification of accreditation, an honor awarded to approximately 1,000 of an estimated 33,000 museums in the United States. To attain this goal, the staff underwent a rigorous multiyear evaluation, by both internal and external evaluators in all aspects of museum operations, all while preparing to open three additional galleries in 2010 and to plan for seven more in the years ahead.52

The acclaim bestowed on the NMMC is a result of the dedication by Marine leaders, Marines, civil servants, volunteers, contractors, and friends of the Corps during the last 80 years. These include the Commandants who provided the official support since the 1930s; the Marine historians and the heads of the museums through the years—Metcalf, Magruder, Nihart, Simmons, and recently Ezell—whose passion and visions of a museum advanced the professionalism of the staffs, programs, stewardship, and exhibitions; the civil servants and volunteers who are the “life and soul” of the museum; the designers and contractors who throughout the Heritage Center project were exceptional in their expertise and cooperation; and finally the friends of the Corps, the Marine Corps Heritage Foundation, whose partnership with the History and Museums Division for 40 years has been critical for success. All have had a hand in the accomplishments of the museum program today.53

•1775•

Endnotes

- Robert Sullivan served as a Marine from 1974 to 2002 and retired as a lieutenant colonel. He joined the museum staff in 1997 as the head of the Museums Branch, History and Museums Division, then transitioned to a curator position at his retirement and remains on the NMMC staff. His current duty is curator of museum design, with a focus on the final phase gallery project.

- A Marine Corps Museum!,” Leatherneck 10, no. 3, March 1927, 22.

- Col Brooke Nihart (Ret), “History of the Marine Corps Museums, Part I, Imperfect Solutions,” Fortitudine 21, no. 4 (Spring 1992): 14.

- R. Cody Phillips, The Guide to U.S. Army Museums (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, U.S. Army, 2005), 90.

- “History,” U.S. Naval Academy Museum website, accessed 15 January 2019.

- “National Museum of the U.S. Navy History,” Naval History and Heritage Command website, updated 25 January 2019.

- “Exhibit at the Sesquicentennial,” Leatherneck 9, no. 9, June 1926, 30.

- Nihart, “History of the Marine Corps Museums, Part I, Imperfect Solutions,” 14.

- B. H. Fuller letter to the Commandant, Navy Yard, Washington, DC, 18 December 1933, copy in the author’s possession.

- “Tun Tavern Museum,” Marine Corps Gazette 19, no. 1 (May 1934): 42. Legend says that Tun Tavern was the original Marine recruiting site in Philadelphia in 1775.

- T. Holcomb Circular Letter No. 391, “To All Officers, Active and Retired, Reserve Officers of the Rank of Captain and Above, Former Officers, and Relatives of Well-known Deceased Officers,” 2 October 1940.

- Nihart, “History of the Marine Corps Museums, Part I, Imperfect Solutions,” 15; and “The New Quantico,” Leatherneck 24, no. 7, July 1941,14–27.

- Nihart, “History of the Marine Corps Museums, Part I, Imperfect Solutions,” 15–16.

- Maj John Elliott (Ret), in discussions with the author, 25 January and 22 February 2019. Elliott, now age 95, is a volunteer at the NMMC, a retired Marine, and former Smithsonian curator of aviation who worked with Col John Magruder in the 1960s.

- Col Brooke Nihart (Ret), “History of the Marine Corps Museums, Part 2, Major Magruder Sought First Full-Scale Marine Museum,” Fortitudine 22, no. 4 (Spring 1993): 27–30.

- Director, Marine Corps Museums letter to Head, Historical Branch, G-3, subject: Marine Corps Museum, 8 January 1962, copy in author’s files.

- Col R. D. Heinl to LtCol John H. Magruder III, memo, Proposed Marine Corps Order of 27 September 1957 with undated draft of Marine Corps Order 4010, subject: Historical Material, preservation of, copy in author’s possession. Heinl’s intent was to resolve issues related to preserving material for historical purposes by defining the procedures within a regulation. Today, the museum section of Marine Corps Order 5750, The Manual for the Marine Corps Historical Program, specifies the NMMC’s mission, billets, responsibilities, services, collections management, collections stewardship, and staff training. Both History Division and NMMC staffs review this consolidated document on a regular basis to ensure the historical program of the Corps is relevant to the needs of the Corps. A number of other regulations at the federal level provide guidance on stewardship, disposition of historical property, gifts and donations, and ethics, among other topics. Col R.D. Heinl Jr., “John Magruder: In Memoriam,” Marine Corps Gazette 56, no. 11 (November 1972): 16–17; A Study Relating to the Establishment of A National Armed Forces Museum (Washington, DC: National Armed Forces Museum Advisory Board, Smithsonian Institution, 1965); Director, Marine Corps Museums letter to Commandant of the Marine Corps, subject: Permanent Marine Corps Museum Building, with enclosures, 1 November 1966; and Wallace M. Green, Green Letter No. 18-67, “Proposed Marine Corps Museum, Arlington, Virginia, with enclosure,” 3 November 1967, copy in author’s file. Magruder was a member of the National Armed Forces Museum Advisory Board. He was in favor of a museum at Quantico or in the Washington, DC, area. The author believes that all three museum initiatives failed due to lack of available resources, service objections, and the timing during the Vietnam War.

- Nihart, “History of the Marine Corps Museums, Part 2, Major Magruder Sought First Full-Scale Marine Museum”; and Magruder letter to Commandant Gen Leonard F. Chapman, 14 April 1969. Magruder requested retirement in this letter and did so with mixed emotions. Magruder letter to LtGen Raymond Davis, 14 July 1970. In the letter, Magruder strongly pushed for the separation of the museum and history programs.

- “Marine Museum Chronicles Our Glorious Past,” News (Marine Corps Historical Foundation), Spring 1990, 5. The Commandant’s Advisory Committee was abolished during the James E. “Jimmy” Carter administration in an effort to streamline government. Later, HD moved into Building 58 and remained there until the division moved to Quantico in 2005.

- NMMC staff reside in the building today. The “old brig,” as Building 2014 is called, has had its share of facility problems. During the 1990s, Quantico Facilities completed a plan for improvements, Project QU 9630M, which included adding an elevator, fire sprinkler system, office spaces, restrooms, etc., but the project was not funded. Over the years, some of these improvements have been completed. The museum’s collections continued to grow and the older buildings on Quantico that housed the artifacts and some staff became obsolete. In 2016, the NMMC leased a commercial building a short distance from the museum that houses much of the collection, curator offices, and restoration work spaces.

- Bruce Martin, “Aviation Museum,” Leatherneck 61, no. 7, July 1978; and Ken Smith-Christmas, email to author, 22 January and 9 May 2019, hereafter Smith-Christmas notes. Smith-Christmas stated that the bulk of the Museums Branch activities—Personal Papers, Special Projects, and Photographs—shifted to the Navy Yard. The staff remaining at Quantico were designated as the Marine Corps Branch Activities, Quantico, and included the deputy director of Museums Branch Col Tom M. D’Andrea, the aviation and ordnance collections, and Restorations Section in Larson Gymnasium. Smith-Christmas started working at Marine Corps Museum at the Washington Navy Yard in 1976, permanently relocated to Quantico in 1986, and served in various capacities in the Museums Branch until his departure in 2005 to the Planning Office for the National Museum of the U.S. Army.

- Herb Richardson, “Birds of Prey on Display,” Leatherneck 62, no. 5, May 1979, 34–39.

- “Events at the Center,” Fortitudine 8, no. 4 (Spring 1979): 22; and “A Symbiotic Relationship: Foundation, Historical Events at the Center,” News (Marine Corps Historical Foundation), Spring 1990, 5. The foundation changed its name to the Marine Corps Heritage Foundation in 1998

- Nancy Lee White, “Marine Corps Air-Ground Museum,” Leatherneck 69, no. 5, May 1986, 55–59; and Smith-Christmas notes.

- The MCAGM closed in 2002. The three hangars are still used by the NMMC as large artifact storage. In 2004, Smith-Christmas was asked to accompany the then-assistant Commandant, Gen Michael J. Williams, on a trip to the Beech Hill Hotel Museum, Londonderry, Northern Ireland, where the World War II Londonderry Marines resided. A conversation at the hotel between Williams and Smith-Christmas included the facility issues of the hangars and soon thereafter funding was provided for the improvements. The structures were painted again, insulated, and outfitted with climate control systems.

- Action memo, HDM: CAW 3.1.3, “Museums Committee Meeting, 6 April 1984,” 18 April 1984; “President’s Remarks at AGM,” News (Marine Corps Historical Foundation), November 1987, 5; “Status Report: Marine Corps Historical Program,” News-Notes (Marine Corps Historical Foundation), December 1988, 5; and “Extension of Foundation’s Air-Ground Museum is Planned,” News (Marine Corps Historical Foundation), Fall 1992, 3. Simmons readdressed the idea for a new museum at Quantico that had been raised previously. The Commandant’s Advisory Committee recommended to the Commandant in its annual report of July 1966 that plans be initiated for a permanent, modern, and expanded museum to house the rich assets held by the Corps. Magruder subsequently submitted his proposal for a permanent museum sited on the parade field near Lejeune Hall in November 1966. The commandant of the Marine Corps Schools endorsed Magruder’s proposal, but moved the recommended location of the museum from the parade deck facing Lejeune Hall to across the street where the current Clubs of Quantico is located.

- Smith-Christmas notes. The authorized strength of federal employees for the museum at Quantico in 1990 was nine. Gen Simmons remarked in his report to MCHF in late 1991 (News, Winter 1991) that with the downsizing of the Corps, he expected a reduction in civilian employee strength of 20–25 percent within the following two to three years. This loss necessitated a reorganization of HD, though the Quantico museum gained two additional civilian staff to total 11.

- “Organization, Mission, and Functions” (briefing paper, History and Museums Division, 12 February 1996); and Museums Branch Recall Roster, 3 January 2000. During the 1990s, the junior enlisted Marines assigned by the Headquarters special assignments monitor to the Quantico museum were drops from the Marine Security Guard School (wrote a bad check, unqualified with service weapon, or academic failure were some reasons). Later, the infantry monitor assigned the enlisted Marines to the museum. One of the two officers assigned was in administration. The officer-in-charge billet specified an officer in an aviation specialty, a holdover from the Aviation Museum’s table of organization. The author had an artillery occupational specialty and the ground and aviation monitors coordinated the billet fill.

- LtGen George Christmas (Ret), “Strategic Planning Review, National Museum of the Marine Corps” (briefing slides, Marine Corps Heritage Center, Quantico, VA, 18–19 October 2001). LtGen Christmas, the foundation’s president, worked tirelessly to garner support for the heritage center and was very successful. “President’s Notes,” News (Marine Corps Historical Foundation), Summer 1995, 2; and “America’s Own,” Visitor Experience Concept Development, draft submission, the Prentice Company, Ames, Iowa, April 1997.

- “Presidents Notes,” Sentinel (Marine Corps Heritage Foundation), Summer 1999, 2, 12. Commandant Gen Charles C. Krulak approved the project by stating in April 1999, “The Marine Corps Heritage Center is envisioned as a multi-use complex of buildings and outdoor facilities. It will be devoted to the presentation of Marine Corps history, professional military educational opportunities, and unique military events. This complex with its varied capabilities will be the showcase for our Marine Corps heritage.” Marine Corps Heritage Center brochure, ca. 2000.

- BGen Gerald L. McKay (Ret), email to author, 16 May 2019. McKay was the foundation’s chief operating officer during the project.

- Lin Ezell, comp., National Museum of the Marine Corps (Lawrenceburg, IN: Creative Company, 2010); and Design Development Drawings, National Museum of the Marine Corps, Christopher Chadbourne and Associates, Boston, MA, 2003. The three original selected sites were on the base, but were found unsuitable for various reasons. A fourth site not on the base was identified during the public comment portion of the study and was selected. Prince William County, VA, offered to transfer the site back to the federal government. This is the present location of the heritage center.

- Ezell, National Museum of the Marine Corps; and Col Joseph C. Long (Ret), “The Competition,” in Portal to the Corps: Chronicling the National Museum of the Marine Corps, ed. Jessica H. del Pilar (Victoria, Australia: Images Publishing Group, 2007), 21–23.

- “National Museum of the Marine Corps Project Workload,” Information Paper, History and Museums Division, 5 February 2003. Col Long was selected by a Headquarters search committee to be the project manager to coordinate the activities among the major organizations and to organize the monthly executive steering committee meetings with the Assistant Commandant.

- 2017 Staff Briefing, National Museum of the Marine Corps, November 2017. Outside the NMMC, heritage paths within Semper Fi Park on the Heritage Center campus overseen by MCHF provided opportunities for reunion groups to erect memorials to their units and fallen comrades and for people to purchase a brick to be placed on the paths in memory of a loved one or comrade. In 2005, to mark the 230th anniversary of the Marine Corps, the U.S. Mint struck a commemorative silver dollar that raised $6 million.

- 2017 Staff Briefing; “Art Purchased for Corps Museum,” News (Marine Corps Historical Foundation), Fall 1991, 6, 8; and “President Reports Past Accomplishments, Future Goals,” News (Marine Corps Historical Foundation), Spring 1992, 1–2.

- See Charles D. Melson’s “Beyond McClellan and Metcalf: Staff History in the U.S. Marine Corps,” 8.

- A committee to examine the organization and functions of the historical program, headed by retired Commandant Gen Carl E. Mundy Jr., was convened on 20 March 2006. The details of the committee’s report and endorsement by retired MajGen Donald R. Gardner, president of Marine Corps University, reflected a focus on the historical portion of the former History and Museums Division than on the museum. The committee was impressed with the direction and leadership of the NMMC.

- Lin Ezell, “NMMC Staff Phone Roster,” 16 June 2006; NMMC Myers- Briggs Roster, 26 December 2006; and Lin Ezell, “NMMC Staff Phone Roster,” 7 July 2009. Contracted security and maintenance crews assisted the Operations/Facilities Section. The collections totaled 40,000 historical objects and art. The staff included both retired military and nonmilitary, many holding graduate degrees in their chosen fields and having years of museum experience before joining the NMMC

- Design Development Drawings, National Museum of the Marine Corps; and Design Development Exhibit Design Package, National Museum of the Marine Corps, Christopher Chadbourne and Associates, Fentress Bradburn Architects Ltd., and Col Joseph H. Alexander (Ret), 16 July 2003. The 70 cast figures that populate the Phase I galleries add realism to scenes. Most of the cast figures were modelled on active duty Marines and sailors.

- Ezell, National Museum of the Marine Corps, 2–3; Design Development Exhibit Design Package, sheets 01.01–01.08; Final Text, National Museum of the Marine Corps, Christopher Chadbourne and Associates, Fentress Bradburn Architects Ltd., and Col Joseph H. Alexander (Ret), March 2005. Leatherneck Gallery has hosted retirements, commissionings, promotions, reunions, family days, educational activities, concerts, formal dinners, proms, and presentations.

- Ezell, National Museum of the Marine Corps, 6–7; Design Development Exhibit Design Package, sheets 04.01–04.17; and Final Text, 8–42.

- Design Development Exhibit Design Package, sheets 05.1–05.19; and Final Text, 43–76.

- Ezell, National Museum of the Marine Corps, 20–25; Design Development Exhibit Design Package, sheets 010.1–10.24; and Final Text, 77–185.

- Ezell, National Museum of the Marine Corps, 26–29; Design Development Exhibit Design Package, sheets 11.1–11.23; and Final Text, 186–233.

- Ezell, National Museum of the Marine Corps, 30–33; Design Development Exhibit Design Package, sheets 12.01–12.20; and Final Text, 234–300.

- Ezell, National Museum of the Marine Corps, 8–11; Design Development Exhibit Design Package, sheets 06.01–06.18; Draft Text, Phase 1A, National Museum of the Marine Corps, Christopher Chadbourne and Associates, Fentress Bradburn Architects Ltd., and Col Joseph H. Alexander (Ret), January 2007, 1–198.

- Ezell, National Museum of the Marine Corps, 12–15; Design Development Exhibit Design Package, sheets 07.01–07.25; and Draft Text, 199–348.

- Ezell, National Museum of the Marine Corps, 16–19; Design Development Exhibit Design Package, sheets 08.01–08.19; and Draft Text, 349–467.

- Lin Ezell, “Final Phase Executive Brief” (PowerPoint brief, National Museum of the Marine Corps, Quantico, VA, 1 October 2013); Final Phase Exhibit Galleries: Concept Design Draft, National Museum of the Marine Corps, Eisterhold Associates Inc., October 2014; Children’s Gallery Design Development, National Museum of the Marine Corps, Eisterhold Associates Inc., 11 March 2015; Ezell, National Museum of the Marine Corps, 34–35; Ezell, “Final Phase Executive Brief”; Design Development Exhibit Design Package, sheets 09.01–09.12; Col Joe Alexander (Ret), “Small Wars Draft Text and Selected Images” (working paper, National Museum of the Marine Corps, 2005); and Draft Text, 468–587. Smaller exhibit spaces include themes such as transforming the Corps, no better friend, service and sacrifice, the events of 9/11, Marine families, and enduring missions. Images, videos, cast figures, and oral histories will enhance the story text.

- A large number of people with first-hand experience and respected opinions assisted the museum staff in this second phase. The NMMC organized a panel consisting of four retired Marine general officers, a retired sergeant major of the Marine Corps, and one university professor to guide the staff on exhibits and messaging. Approximately 50 writers supported the tasks of writing text, coordinated by the author, which included NMMC staff, Reserve Marines from the Field History Branch of History Division, historians, university educators, volunteers, interns, active duty and retired Marines, and naval personnel. A historian from History Division was included in the writing pool both to draft text and to review the drafts and selected maps from the other writers.

- A number of other awards received for the NMMC project included: 2006, Pyramid Award, Associated Builders and Contractors and Platinum Award for Engineering Excellence (with Centex, now Balfour Beatty), American Council of Engineering Companies of New York; 2008, American Architecture Award Chicago Athenaeum/Metropolitan Arts Press, Innovative Design and Excellence in Architecture using Steel; 2009, the Themed Entertainment Association recognized the NMMC for outstanding achievement in exhibits. The Marine Corps League of the Washington, DC, area awarded its Dickey Chapelle award to Director Lin Ezell for outstanding contributions to the morale, welfare, and well-being of the officers and enlisted Marines of the Corps, and the secretary of the Navy presented an award of merit for group achievement. In 2011, the South Eastern Museums Conference awarded its Gold Award to the NMMC in its annual publications competition, gallery guide category. The award-winning architectural design incorporated many sustainability features, such as a green roof system, bioretention facilities, and the use of highly recycled materials. The author has a complete list of awards from the building design courtesy of Brian Chaffee, lead architect at Fentress on the NMMC project.

- Edward P. Alexander, Museum Masters: Their Museums and Their Influence (London: AltaMira Press, 1995), 16. The museum website www.usmcmuseum.org includes a virtual tour and other information of interest to the visitor.