PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

The Marine Corps History Division was born only one month after the last troops returned home from occupation duty in Germany in 1919. The Marine Corps that came back from World War I was different than the one that had left the year before, its combat record in modern warfare paving the way for a more assertive role in national defense.2 At the apex of this transformational shift, Headquarters Marines Corps constituted the Historical Section, as it was first known. Since, the successors of the Historical Section, including today’s History Division, have played a role in the subsequent eras of change in the Marine Corps.3 The division’s importance is not in chronicling what has already been, though that history is an important component of Marine culture.4 More crucial is its role in producing works that inform those responsible for making decisions that will shape the future of the Service. As a result, the division’s publications are historical documents in and of themselves, illustrative of what the leadership has deemed important enough to study at a given moment. To analyze them is to understand how the Marine Corps has evolved institutionally, doctrinally, and philosophically.

This article is a historiography of History Division publications from 1919 to present. It charts how the office reacted to and sometimes took part in contemporaneous debates and transformations inside the Marine Corps. It is neither a strict accounting of the division’s entire publishing record nor a survey of publication types—indeed, staff writers and contributors have published more than 250 titles to date, from the limited scope of pamphlets and occasional papers to the expansive monographs and multivolume definitive histories. It is instead a work that illustrates cause and effect in official histories, an examination of how History Division writers have acted as more than chroniclers; they also have contributed to discussions inside the Marine Corps about the Service’s future. As such, this article uses the major events of the Marine Corps since 1919 as a framework, and charts how the History Division reacted to those discussions with the works that they produced.

The Marine Corps is a learning institution. It uses its history to make informed decisions about contemporary challenges. Its History Division, in fulfillment of its mission to record the official institutional and operational history of the Corps, has contributed to that process for 100 years.

Early Works, 1919–40

When Commandant Major General George Barnett established what would become the History Division within Headquarters Marine Corps, he tasked the first officer in charge, Major Edwin N. McClellan, with producing a history of Marines in World War I. He did so on the orders of Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels, who directed both the Marine Corps and Navy to record their wartime experience for the sake of propriety and future study. It was a good opportunity for Barnett, who had fought hard to ensure that his Marines were involved in the ground war.5 By most measures, the Marine Corps flourished in the war, expanding from a strength of 13,725 in April 1917 to a peak of 75,101 a year and a half later.6 The Service also occupied a new place in public consciousness, capturing the imaginations of Americans who read about Marines’ performance at places like Belleau Wood, France.7

McClellan handed his manuscript to Barnett on 26 November 1919. The United States Marine Corps in the World War reads more like a historical report than a history. McClellan’s handling of operations is less vivid than one may be accustomed to when it comes to World War I, owing to a lack of narrative. What the volume lacks in storytelling, though, is made up in usefulness. McClellan charts how units were organized, trained, and deployed, providing ample facts and figures in several charts. The latter stages of his book switch from chronological to topical, and he covers everything from aviation and casualties to rifle practice. All of this underscores an important point about McClellan’s intended audience. The History Division today attempts to produce historical works that are applicable to Marines but appeal to other Federal agencies, scholars, and a general audience. By contrast, McClellan’s purpose was to report to the Commandant and secretary of the Navy on the lessons the Corps learned during World War I, with perhaps an eye toward how they might be applied in future conflicts.

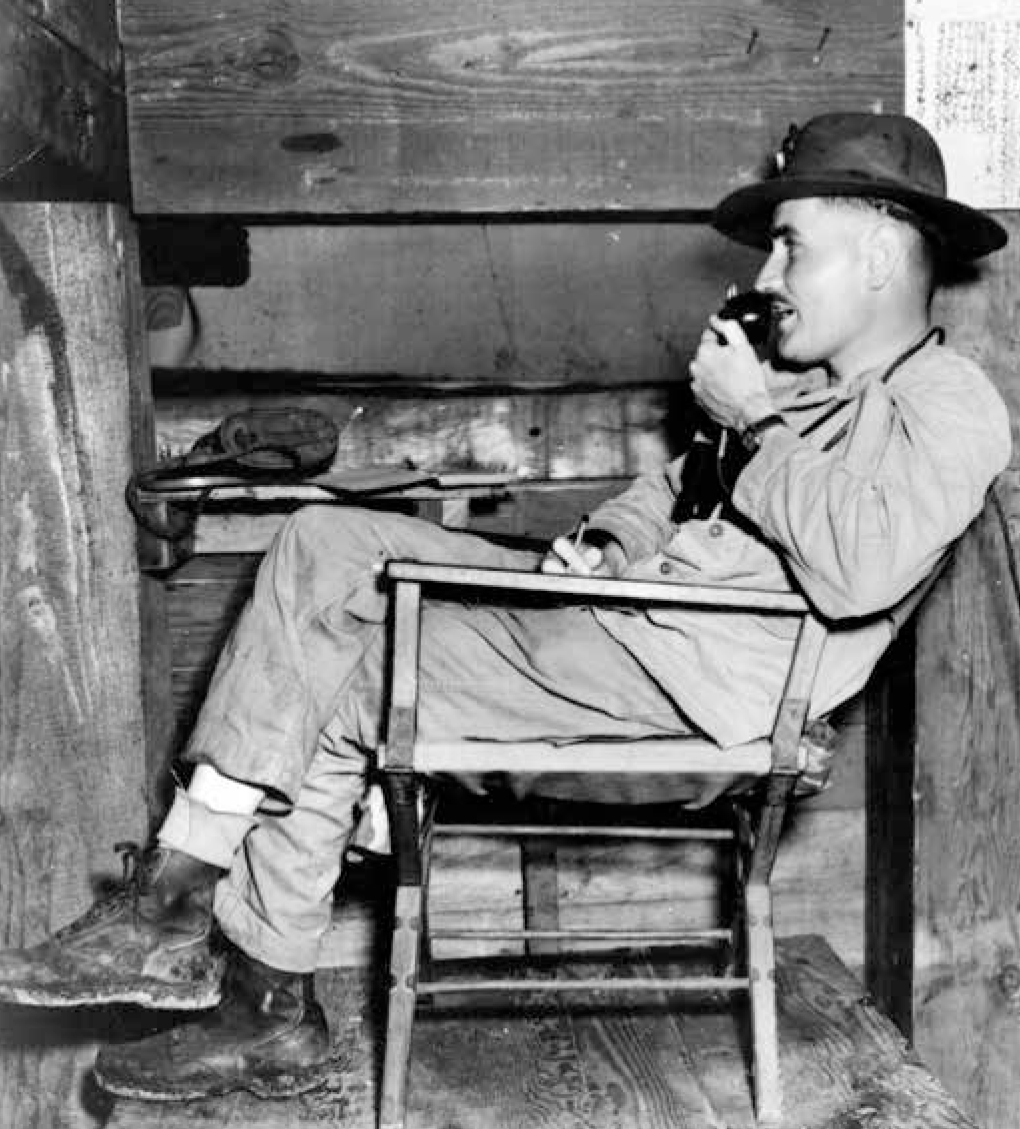

Maj Edwin N. McClellan. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo

McClellan’s second project was an ambitious seven-volume history of the Marine Corps since its inception, which falls in line with today’s History Division mission of writing to multiple audiences. While he had completed his World War I volume in mere months, he found it difficult to work on a large institutional history. He was forced to put aside the history of the Marine Corps when Headquarters transferred him out of the Historical Section in July 1925, placing him in a variety of staff roles during the next six years in Hawaii, California, Oregon, and Nicaragua.8 He returned to his old billet in the Historical Section in June 1931, but the project still floundered. McClellan spent so much time in exhaustive research and meticulous writing that he simply ran out of time to complete the planned work. He finished two volumes, both of which are sprawling, if not meandering—in 1,700 pages, he only made it to the War of 1812. The two rough-around-the-edges volumes were published in 1931 as History of the United States Marine Corps in mimeographed form. While this first attempt at an official history of the Marine Corps was stillborn, a later director of History Division, Lieutenant Colonel Clyde H. Metcalf, picked up where McClellan left off, basing some chapters of his own work on McClellan’s research, and publishing A History of the United States Marine Corps with a commercial press in 1939 to become the unofficial history of the Service.9

The nascent works of the History Division’s predecessor reflected a Marine Corps at a crossroads. With the expansion of American territorial holdings overseas after the Spanish-American War came an increase in the U.S. Navy’s strategic duties. To support overseas territorial holdings as well as a fleet that was now responsible for hundreds of thousands of square miles of ocean, coaling stations at advanced bases were required in the Pacific and Caribbean. After first resisting, the Corps responded with a concept in 1913 to defend these areas. The Advanced Base Force expanded the Marines’ traditional role as ships’ guards and an expeditionary force. By 1920, Headquarters Marine Corps was staffed with leading thinkers such as Major Earl H. Ellis, who theorized how advanced base operations would work in practice. While Ellis was writing two seminal studies in the Division of Operations and Training, McClellan was producing his institutional histories in the Historical Section, which were, in essence, attempts to explain how the Service of the 1920s came to be.10 In History of the United States Marine Corps, McClellan goes to great pains to illustrate how Marines are part of a long tradition of soldiers of the sea. Indeed, it takes 300 pages to get to the creation of the Marine Corps. Yet, he finds that they are a force capable of adaptation and change.

McClellan’s successor continued this theme. In 1934, Captain Harry A. Ellsworth wrote One Hundred Eighty Landings of United States Marines.11 More than a compilation of landings between 1800 and 1934, the work once again reflected the historical basis for contemporary discussions. Months prior, the Marine Corps replaced the Advanced Base Force with Fleet Marine Force, a more mobile, offensive concept. The emphasis was now on amphibious assault rather than seizing and defending naval bases. Ellsworth’s book appeared alongside a study that a group at the Field Officers School had been working on since 1931, Tentative Manual for Landing Operations, which established the principles of amphibious warfare doctrine for the Fleet Marine Force and had considerable influence on the students who passed through Quantico for the next decade.12 While the authors of the manual looked forward, Ellsworth looked backward. There was, in fact, an evolution in Marine Corps amphibious warfare development prior to 1934, though it did not progress linearly. The first landing occurred in 1800, during the Quasi-War with France, when a detachment of Marines from the USS Constitution stole a French cutter at Puerto Plata, Dominican Republic, and then spiked the batteries protecting the harbor. In the following decades, Marines mounted landings almost once a year, though none of the lessons were translated to doctrine specific to the Corps. That information in- stead was conserved in a series of U.S. Navy manuals, the first of which appeared in the 1866 edition of the Navy Department’s primer for sailors and Marines, Instructions in Relation to the Preparation of Vessels of War for Battle to the Duties of Officers and Others when at Quarters; and to Ordnance and Ordnance Stores. Twenty years later, the Marine Corps received its own manual, The Naval Brigade and Operations Ashore: A Hand-Book for Field Service, but still published under the auspices of the Navy.

Maj Clyde H. Metcalf in 1934. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo

Though Ellsworth’s historical study does not connect the forward-looking Tentative Manual for Landing Operations to its doctrinal predecessors, he does find that landings had been done for four basic reasons: political intervention, punitive actions, security of diplomatic missions and nationals, and humanitarianism. He argues that the Marine Corps has been employed for armed intervention in the past by virtue of its organization and training, and, according to experts, because the president is not required to seek a declaration of war from Congress for their use.13

McClellan and Ellsworth outlined several concepts that became themes in the early works of the division and continue today. The first is the Marine Corps’ ability to adapt and change. The second is the transformation that the ability to adapt beget, specifically the transformation into an amphibious force. On the eve of World War II, that concept would be put to the test, but not before General Thomas Holcomb, the Commandant at the time, navigated budget constraints to adopt important technological developments and expand manpower requirements.14

The 5th Marine Regiment landing at Culebra, Puerto Rico, during fleet maneuvers in winter 1923–24. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo, 515293

Making the Mold, 1941–60

The 1940s was a growth decade for the History Division, though only the latter half. The Marine Corps’ requirements for the war effort meant that the office, despite being larger than it had been for the first 20 years of its existence, went through frequent staff expansions and contractions, making it difficult to pro- duce histories and studies of the recent campaigns, operations, and battles. In the final months of the war, however, the division began publishing unit histories, the first of many in the years to come. The booklets were intended for veterans as well as a general audience and were written in the vein of the work published by the U.S. Army’s Information and Education Division in Paris at the time. The initial histories—two of which First Lieutenant John C. Chapin wrote when he was assigned to the division while recovering from wounds received on Saipan—covered the formation, training, and combat experiences of the 4th, 5th, and 6th Marine Divisions.15

The unit histories were a new addition to the type of publications the office produced, as were what followed, the first large-scale, concerted effort to produce a book series. In 1947, decorated combat veteran and director of the division at the time Lieutenant Colonel Robert D. Heinl Jr. wrote The Defense of Wake.16 During the next eight years, he and his successors oversaw the writing and publishing of 15 monographs that charted the Marine Corps’ operational history in World War II. Book-length studies of campaigns and operations, monographs have become the most common History Division publication and can range anywhere from 15,000 to 150,000 words. These World War II volumes set the standard for what would follow. With the aid of official records, the authors produced works that were comprehensive in their coverage of operations, giving readers everything from the context of discussions that occurred at Admiral Ernest J. King’s headquarters to the heroics of Marines landing on beaches throughout the Pacific. The authors, all of whom were field-grade officers, are critical where warranted. Captain James Stockman argues that Tarawa showed there needed to be better flexibility in ship-to-shore movement, thereby allowing the landing force the ability to control supply and reinforcements to fit the situation on the beaches.17 Major Frank O. Hough, among other authors, was critical of naval gunfire, contending that it was so insufficient on Peleliu that the enemy was able to inflict casualties on the assault forces and hamper the first day’s operations.18 The criticism was constructive as much as it was academic, providing planners lessons from the last war that might be applied to the next.

While the History Division was recording operations in World War II and evaluating successes and mistakes, the Marine Corps was atrophying. On V-J Day, there were 485,000 Marines in uniform.19 Five years later, there were 74,279.20 In between, the Marine Corps fought an important battle in Washington, DC. The National Security Act of 1947 had wide-ranging effects on the military, chief among which was the establishment of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the creation of the Department of Defense two years later. The reorganization of the national military establishment brought to the fore inter-Service competition for funding. The Marine Corps, part of the Department of the Navy and without a permanent seat on the Joint Chiefs of Staff, fought a rearguard action between 1948 and 1950 against those in Congress and the Pentagon who made the case for eroding its role as a force in readiness. Marine leaders and their allies pointed to the Service’s World War II successes and defended the Corps’ capabilities and missions to avoid being subsumed into the other Services.21 Though unintended, the History Division monographs made the case for the Marine Corps as an independent branch.22 Soon after the unification storm died down, the North Korean People’s Army crossed the 38th Parallel on 25 June 1950 in a bid to reunify the Korean peninsula under the Communist flag. Two weeks later, the 1st Marine Division formed the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade with troops scraped together from posts throughout the United States. In the coming months, reservists replenished the depleted division. It was these feats of mobilization that the History Division recorded in their first work on the Korean War. In 1951, the office produced a pamphlet from Captain Ernest H. Giusti, titled Mobilization of the Marine Corps Reserve in the Korean Conflict, a not insignificant topic given that the Organized Reserve and Volunteer Reserve made up the lion’s share of the Marine Corps forces that arrived in Korea early in the war. In June 1950, reservists outnumbered active duty troops two to one.23 Even by March 1951, after active duty strength was tripled, the Reserves still comprised 45 percent of the Marine Corps.24 As a pamphlet, Giusti’s work was intended for internal reference. The primary audience was staff officers, who were to learn lessons in how to mobilize, important for a Service that boasted the ability to react to situations around the globe. He argued that the Corps’ reserve program was sound and the experience in Korea justified it as a concept.25 No doubt the reservists’ prior experience added to their effectiveness, as 99 percent of officers in the Volunteer Reserve and 75 percent of its enlisted men were World War II veterans.26

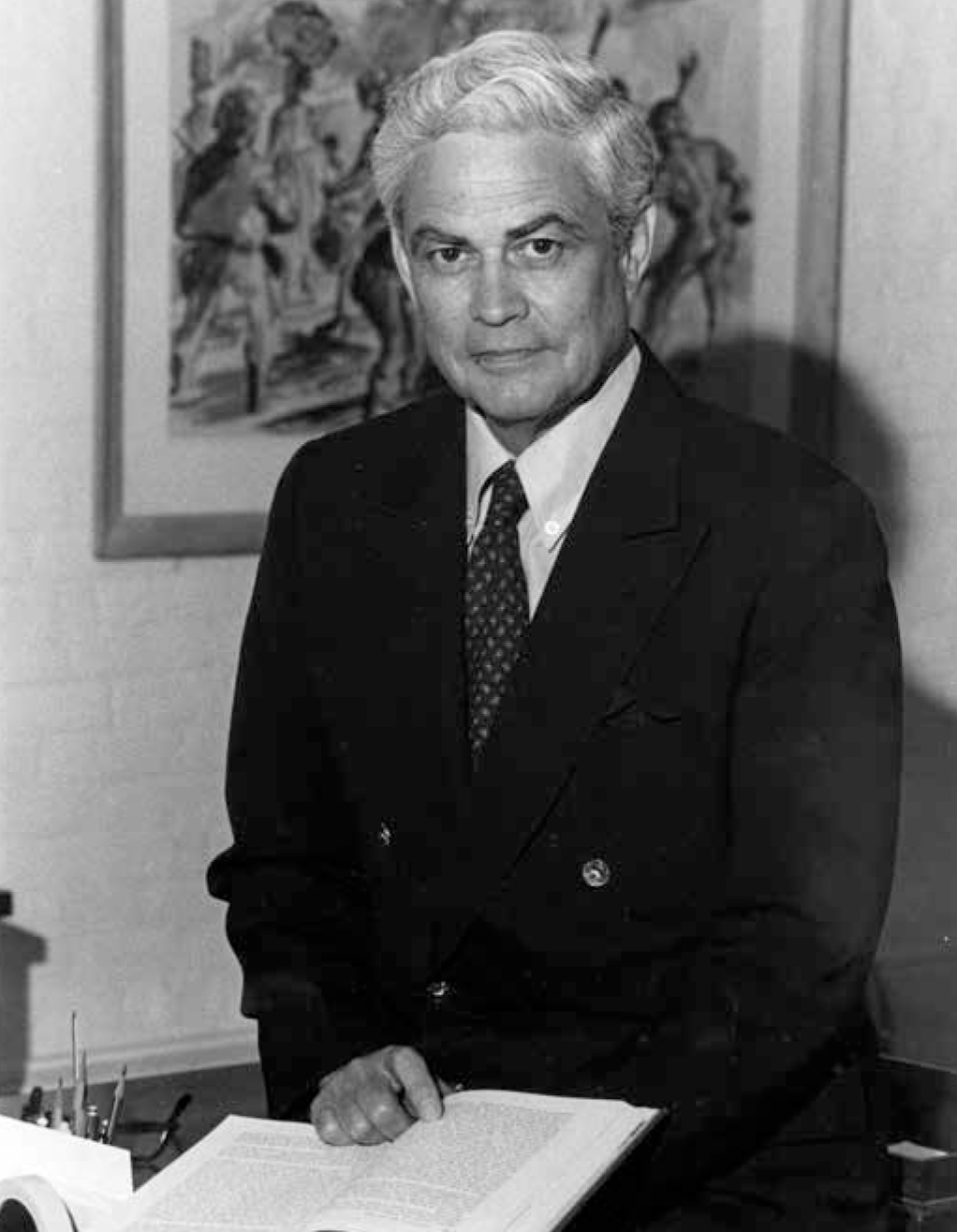

Robert D. Heinl Jr. during naval gunfire training in Hawaii when he was an officer on Gen Holland M. Smith’s staff. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo

The Korean War provided the History Division with an opportunity to employ field historians attached to the office. The new concept was Heinl’s; his experience writing the World War II monographs led him to conclude that the Marine Corps needed a better way of recording events for later use. He studied the U.S. Army’s historical program, which included a mobilization plan for reservists who were professional historians. Finding merit in the concept, Heinl established a Marine Corps version, creating the 1st Provisional Historical Platoon, which was activated in late 1950 and operated until July 1952.27

The History Division began publishing the first draft of the official history of the Korean War as early as June 1951, a direct result of hiring civilian historians with advanced degrees.28 A series of articles from the division’s historians appeared in the Marine Corps Gazette and were published in 1954 as a compilation titled Our First Year in Korea.29 Most of the articles were from Lynn Montross, an already established writer and author of a hefty overview of military history called War Through the Ages that became a textbook of sorts on college campuses mid-century.30 It was these articles that formed the basis for the most important undertaking of the History Division to that point. In 1954, the division published The Pusan Perimeter, the first book in a five-volume series of definitive histories titled U.S. Marine Operations in Korea, 1950–1953. Montross was the primary author of the series, coauthoring four of the five volumes, three of them with Captain Nicholas A. Canzona, who had been awarded the Silver Star for destroying bridges at Hagaruri, protecting the retreating Marines’ flank when breaking out from the Chosin Reservoir. The volumes of U.S. Marine Operations in Korea were written in the vein of the U.S. Army’s vaunted World War II definitive histories, the “Green Books,” which Army historians had begun in 1946. Relying on official documents and providing a detailed narrative, Montross and the series’s other authors focus on aspects that resemble the World War II monographs, with emphasis on planning and operations, from the highest reaches of Headquarters down to the experiences of individual troops.31 The difference, however, is size and scope. Definitive histories range from 110,000 to 600,000 words, compared to the more modest 15,000 to 150,000 words for monographs, and are the most comprehensive and detailed accounting of Marine Corps operations during a major conflict. As they were the first, the Korean War “Blue Books” set the model for History Division definitive histories.

While the office was still completing its largest project to date, it began yet another ambitious series, one for which it is best known. In 1958, it published Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, the first of five volumes that would make up the History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II definitive histories.32 The monographs that the division produced between 1947 and 1955 served as the foundation upon which the series was built. Henry I. Shaw Jr., chief historian of the division, oversaw and cowrote the series. The volumes are arranged chronologically, and the first chapter on the creation of amphibious war concepts in the 1920s sets the tone. These are works that evangelize the virtues of amphibious warfare. Unlike the Army or Navy, whose roles as land and sea powers have never been challenged, the Marine Corps has not considered itself impervious. World War II was the purest illustration of its role and capabilities, as well as the bravery of those who served. U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II covers aspects that are therefore important to the identity of the Service. This significance and the quality of research and writing of the “Red Books,” as they are referred to, ensures that even today they remain an invaluable resource for scholarship on operations.

Concurrent with the writing of the World War II and Korea definitive histories, the division continued producing booklets and pamphlets that informed discussions occurring inside the Marine Corps. The Service had survived the post–World War II draw-downs and then proved itself once again in combat. After Korea, leaders strived to convince national security decision makers that the Fleet Marine Force was an important component of the U.S. defense strategy for the Cold War. The Marine Corps had to navigate the Dwight D. Eisenhower administration’s “New Look” national security policy carefully, however, as it emphasized nuclear deterrence through massive retaliation. By contrast, the Corps’ identity was as a conventional force, small, mobile, and amphibious. To maintain its force in readiness mission and prepare for a wide range of contingencies, all while not alienating itself from the other Services, it undertook a series of doctrinal studies and development programs in the mid-and late-1950s to assess its roles and missions.33 Out of this came the idea for the Marine Air-Ground Task Force (MAGTF), General Lemuel C. Shepherd’s attempt to build a flexible expeditionary combined arms concept. Technology was the enabling but also limiting factor for such doctrinal innovations. Helicopters gave the Marine Corps maneuverability, but there was a lag in modifying and procuring ships from which to operate. Until then, and until senior Marines could agree on mission, composition, and size, the MAGTF would be a concept and not doctrine. The maxims of Marines going to war with four elements— command, ground, aviation, and logistics—and that the size of the task would dictate the size of the force did not come until December 1962.34

Fox Company, 2d Battalion, 1st Marines, head toward Inchon, Korea, 15 September 1950. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo, Frank Farkas Collection (COLL/4463), Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division

The History Division publications from the latter half of the 1950s reflected this broadening of attention in the Corps. The office produced a range of studies that looked as much to the future of the Service as its past, covering conflicts (The United States Marines in the War with Spain) and institutional changes (Marine Corps Ground Training in World War II).35 The prolific staff historian Bernard C. Nalty almost single-handedly did much of the work in a historical reference series, covering myriad aspects of Marine Corps heritage, from the Civil War (The United States Marines in the Civil War), Marines’ role in the Caribbean (The United States Marines in Nicaragua), and China (The Barrier Forts: A Battle, a Monument, and a Mythical Marine), to installations (A Brief History of the Marine Corps Base and Recruit Depot, Parris Island, South Carolina, 1891–1956; A Brief History of the Marine Corps Base and Recruit Depot, San Diego, California), the traditional role of Marines as diplomatic guards (The Diplomatic Mission to Abyssinia, 1903), and officer selection since 1775 (A Brief History of Marine Corps Officer Procurement).36

Vietnam and the Search for Historical Lessons, 1960–75

The Marines found an ally in the John F. Kennedy administration. In contrast to Eisenhower, Kennedy deemphasized nuclear weapons in his national security strategy. He preferred flexible response to massive retaliation, and illustrated early into his presidency that he was prepared to use special operations and small, conventional forces to achieve objectives, believing that an incremental approach to using military power was more credible to deterring Soviet encroachments than threatening nuclear war. There was apprehension from senior leaders about counterinsurgency, however. With the exception of Major General Victor H. Krulak, who embraced the role, most were dismissive of the mission.37 All the same, the History Division began producing works that underscored the Corps’ global reach historically. Henry I. Shaw Jr. published The United States Marines in North China, 1945–1949, outlining III Amphibious Corps’ skirmishes with communists and their support of the Chinese nationalists while repatriating 600,000 Japanese and Koreans during Operation Beleaguer.38 Two annotated bibliographies followed in 1961, both calling upon the Corps’ prior experience in irregular warfare.39 Major Marvin L. Brown Jr.’s The United States Marines in Iceland, 1941– 1942 a few years later was meant to illustrate how the Marines operated in short-of-war operations.40 Jack Shulimson’s Marines in Lebanon, 1958 outlined Task Force 62’s role in the July–October 1958 U.S. military intervention in Lebanon to protect the pro-Western government there, though its publishing was an attempt to show the effectiveness of the Marine Corps carrying out American foreign policy through a show of force.41 A group of authors made these points more explicit in A History of Marine Corps Roles and Missions, 1776–1962, a reference pamphlet that outlined how flexible the Marines had been historically.42 This was the second time that such discussions had taken place inside the Corps. The first began in the 1920s, when individuals began studying the Banana Wars, culminating in the now-classic Small Wars Manual, published in revised form in 1940 and codifying the lessons troops learned waging irregular warfare.43 Understaffed and too preoccupied to take part in the earlier discussions, the History Division made sure that it studied operations short of war the second time around.

After Battalion Landing Team, 3d Battalion, 9th Marine Regiment, came ashore north of Da Nang on 8 March 1965, beginning the Corps’ involvement in Vietnam, such discussions ended and the History Division followed a pattern it had begun during Korea. The office published the first work on the war in 1967 with one audience in mind: Small Unit Action in Vietnam, Summer 1966 was intended to keep troops in-country and those about to deploy informed about lessons learned in combat and civic action. The project had its origins in a concept from the assistant chief of staff, G-3, Major General William R. Collins, who wanted to produce readable but accurate works for the benefit of enlisted Marines and junior officers. The author, Captain Francis J. West Jr., would go on later to become an analyst for the Rand Corporation, assistant secretary of defense for International Security Affairs during the Ronald W. Reagan administration, and a leading commentator on Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF).44 Another lessons-learned book, a companion piece to West’s work, followed two years later, U.S. Marine Corps Civic Action Effort in Vietnam, March 1965–March 1966.45

By 1969, Marine operational history of Vietnam began to appear. The first was Captain Moyers S. Shore’s The Battle for Khe Sanh, with a foreword from General William C. Westmoreland.46 As with the World War II monographs, the work is comprehensive for its size. Shore focuses not just on the siege of Khe Sanh but also on Marine Corps operations in the area leading up to the battle and four months afterward, stressing that the isolated outpost was part of the three-pronged strategy for I Corps: pacification, counterguerrilla, and large unit offensive actions.

Despite Shore’s work, the History Division did not create a monograph series for Vietnam as they had for World War II. Instead, it produced the larger definitive histories, nine volumes under the series name U.S. Marines in Vietnam, with staff historian Jack Shulimson as the lead for the project.47 The first, The Advisory and Combat Assistance Era, 1954–1964, was published in 1977. The division released new volumes every two years, the most popular of which, The Defining Year, 1968, was the last published in the series and came in at a thorough 800 pages.48 Playing a crucial role in establishing the vision for the definitive histories was Brigadier General Edwin H. Simmons, director of the History Division from 1971 to 1996 and namesake of the building where the division resides today at Marine Corps University. Under his direction, the division expanded and thrived, making him perhaps the most important director of Marine Corps history next to McClellan. Simmons insisted on accuracy and readability, mirroring the World War II Red Books and the Korea definitive Blue Book histories. The Vietnam volumes followed their predecessor’s operational history model, but they also acknowledged the difficulties the Marines faced, such as the frustrations of pacification, the effect of the draft on the Corps, and problems with discipline and morale, all reflecting that Vietnam was indeed a different war than World War II and Korea.

History Division and Modern Warfare, 1975–Present

While the History Division published its definitive histories, the Marine Corps struggled to find its place in a post–Vietnam defense landscape. As early as 1971, the leadership urged Marines to move on. “We got defeated and thrown out,” then-Commandant General Leonard F. Chapman Jr. said. “[T]he best thing we can do is forget it.”49 Since some viewed Vietnam as an aberration, it was fitting perhaps that, in some ways, the Marine Corps’ experience from the New Look era was repeated in the late 1970s and into the 1980s, as the Service was buffeted by the storm of budget cuts and critics who claimed there was no role for an amphibious force vulnerable in nuclear war that operated primarily outside of Europe. The Corps reaffirmed its belief in maritime supremacy and the importance of amphibious forces in providing a forward collective defense in Asia and Europe.50 Organization and doctrine changed to reflect this new role, updating the MAGTF, once again due to technology. In 1976, the Navy commissioned the first Tarawa-class amphibious assault ship, which gave the Marine Corps the ability to land a battalion of troops either via helicopters or, owing to a well deck, amphibious craft.

Chief Historian Henry I. Shaw presenting the first copy of the third volume in the History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II series to Gen Wallace M. Greene Jr., Commandant of the Marine Corps, June 1967. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo

Though the Marine Corps preferred to put Vietnam behind it, the History Division ran in the opposite direction, continuing to produce a range of volumes on Vietnam, from a spate of works on aviation to monographs on chaplains and military law.51 This is the first discernible moment in the division’s history where it diverged from discussions occurring inside Headquarters and the schools at Quantico, due to Simmons’ vision and direction. In addition to the Vietnam works, the office tackled studies on multiple conflicts, both commemorating foundational periods in the Corps’ history as well as recording recent events. In the former category was Charles Smith’s definitive history, Marines in the Revolution, which coincided with the bicentennial of the Marine Corps’ founding in 1775.52 In the latter was Ronald Spector’s U.S. Marines in Grenada, 1983, a work that Spector, a Reserve Marine officer and an established scholar, called “an experiment in the writing of contemporary military history.”53 In reality, the division had been doing just that for a decade already, and would continue the model into the next several wars.

1st Battalion, 4th Marines, board a Boeing Vertol CH-46 Sea Knight helicopter from Marine Medium Helicopter Squadron 165 for operations northwest of Phu Bai, 1967. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl R. R. Keene, Jonathan F. Abel Collection (COLL/3611), Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division

When the 1990s dawned and the Soviet Union survived to see just two short years of it, thus ending the post–Vietnam discussion about the Marines’ capabilities on a Cold War battlefield, the office began publishing commemorative histories. Commemoratives emphasize a readable narrative intended for a general audience and have since become a staple of the division. The first, by former Chief Historian Henry I. Shaw Jr., was published in 1991, observing the 50-year anniversary of America’s entry into World War II. Opening Moves: Marines Gear Up for War was the inaugural work in a 25-volume commemorative series on World War II, with the last published in 1997, and all of which were truncated versions of the monographs written between 1947 and 1955. Since, the division has published commemoratives on World War I, Korea, and Vietnam.

The U.S. military’s response to Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait tested the Fleet Marine Force that leaders such as Lieutenant General Alfred M. Gray Jr. had overhauled in the 1980s.54 A modernized and reequipped Marine Corps performed well in the Gulf War, first deploying to the region with impressive speed and then opening a breach and racing to Kuwait City with the 1st and 2d Marine Divisions. In short order, the History Division planned seven full-length volumes about the Gulf War in a return to how the office recorded operations after World War II. In 1992, the division published U.S. Marines in the Persian Gulf, 1990–1991: Anthology and Annotated Bibliography.55 This followed in the footsteps of the Vietnam series, which also was preceded by an anthology with the intent of providing a collection of articles and documents that served as an interim reference until the division could complete the official histories. The first monograph in the series appeared in 1993: Lieutenant Colonel Charles H. Cureton’s With the 1st Marine Division in Desert Shield and Desert Storm.56 Twenty-one years later, staff historian Paul Westermeyer published the single-volume definitive history of the war, U.S. Marines in the Gulf War, 1990–1991: Liberating Kuwait, as the comprehensive work on the subject.57 The division was able to write such detailed history soon after the event because of historical document collection that occurred during the war. Like their predecessors had done during the Korean War, five officers from the Mobilization Training Unit (History) deployed to the gulf and assembled notes and documents and conducted oral history interviews.

BGen Edwin H. Simmons in 1980. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo, A708141

The Marine Corps formalized this model in the wake of the Gulf War, creating today’s Field History Branch within the History Division. This meant a shift away from the Mobilization Training Unit system, which tasks a unit to support operational requirements when needed, to the Individual Mobilization Augmentee Detachment (IMA Det) program, which places skilled individuals within an existing unit. The IMA Det allowed the History Division to expand in short order—as it did during operations in Haiti, Bosnia, and Kosovo—and augment its staff with historically trained reservist Marines, who do an excellent job not only collecting historical materials but also authoring occasional papers, battle studies, and monographs. The expansion of the History Division during the 1990s with IMA Det personnel led to a dual-track approach in publishing, split between Desert Storm monographs and World War II commemoratives.

Despite the changes to History Division’s organization, it approached the task much as it had before when Marines deployed to the gulf once again in 2003 for Operation Iraqi Freedom: field historians mobilized and deployed to collect materials and interviews, the division published an anthology first as a stopgap and writers produced a series of monographs.58 The first of the monographs came from Colonel Nicholas E. Reynolds, commander of the Field History Detachment. Published in 2007, U.S. Marines in Iraq, 2003: Basrah, Baghdad and Beyond covered the march up during the combat phase of OIF.59 Its counterpart, U.S. Marines in Iraq, 2004–2005: Into the Fray, was published four years later.60 In between, the History Division published battle studies, calling back on the World War II monographs on operations, yet on a smaller scale. This new series, called U.S. Marines in Battle, started in 2008 with a volume on the Gulf War engagement at al-Khafji.61 Two OIF battle studies in the series followed the next year with Francis Kozlowski’s examination of an-Najaf and Colonel John Andrew Jr.’s on an-Nasiriyah.62

Staff historian Dr. Nicholas J. Schlosser became the division’s OIF expert, recording what Marine units had done in Iraq with battle studies on al-Qaim and Fallujah while also participating in discussions within and without the Service about the U.S. military’s prior experience with counterinsurgency.63 His monograph U.S. Marines and Irregular Warfare Training and Education: 2000–2010 answered how the Marine Corps adapted to fight the Global War on Terrorism, calling on its history with insurgencies to modify its modern warfighting philosophy.64 The volume he edited with James Caiella from papers presented at Marine Corps University’s 2009 symposium “Counterinsurgency Leadership in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Beyond” is a good companion to his monograph and an important successor to Colonel Stephen S. Evans’s 2006 anthology U.S. Marines and Irregular Warfare, 1898–2007.65 Compared with the work that has been completed on the Marines in Iraq, there is still ground to cover on Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF). To date, there have been three works on Afghanistan, two anthologies, and Colonel Nathan S. Lowrey’s monograph U.S. Marines in Afghanistan, 2001–2002: From the Sea on operations during the first year.66

USS Tarawa (LHA 1) leads the landing helicopter assault ships (LHA) and landing helicopter dock ships (LHD) of Task Force 51 in the Persian Gulf on 20 April 2003, one month after Operation Iraqi Freedom began. The task force was the largest amphibious force assembled since Inchon. Official U.S. Navy photo by PhoM Tom Daily

Col Kurt Wheeler, a field historian deployed to Iraq, interviews a gunnery sergeant at Camp Ramadi, 2006. Photo by Col Kurt Wheeler, USMCR

As it has from its inception, History Division continues to reflect debates occurring in the wider Marine Corps. Today, the division’s support of Marine Corps University (MCU), where it moved in 2006, is the most direct way that it contributes to these discussions. This was seen recently in the anthology The Legacy of American Naval Power: Reinvigorating Maritime Strategic Thought, which serves as a companion to a lecture series from MCU president Brigadier General William J. Bowers called “Reinvigorating Maritime Strategic Thought: The Future of Naval Expeditionary Force.”67 The History Division’s place on the MCU campus ensures that its writers will be part of such discussions for years to come. The office’s mission of informing the public of the Marine Corps’ role in national defense by preserving, presenting, and promoting the Service’s history also continues. Work on the Vietnam and World War I commemoratives is ongoing. The first of this series was released in 2014: Colonel George R. Hofmann’s The Path to War: U.S. Marine Corps Operations in Southeast Asia, 1961–1965.68 The office is in the research stage for a definitive history series on OIF, following in the footsteps of the authors who wrote the World War II and Korea volumes. There are also works in various stages of completion on Marines in the Frigate Navy, an edited volume on the cultural implications of the Iwo Jima flag raisings, and operational histories of OEF. The staff, historically minded people who live in the present and commanded by people who look to the future, continue the mission.

•1775•

Endnotes

- Dr. Seth Givens is a historian in the Histories Branch of the Marine Corps History Division. He received his PhD from Ohio University in 2018. He currently is preparing the official history of the Marine Corps in Operation Iraqi Freedom.

- Allan R. Millett, Semper Fidelis: The History of the United States Marine Corps, 2d ed. (New York: Free Press, 1991), 317–18.

- Hereafter, all iterations of this office will be referred to as History Division.

- See Aaron O’Connell, Underdogs: The Making of the Modern Marine Corps (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014)

- Millett, Semper Fidelis, 287–96.

- Maj Edwin N. McClellan, The United States Marine Corps in the World War, 4th ed. (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps History Division, 2017), 6–7.

- Peter F. Owen, To the Limit of Endurance: A Battalion of Marines in the Great War (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2007).

- Owen, To the Limit of Endurance, xvii.

- LtCol Clyde H. Metcalf, A History of the United States Marine Corps (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Son, 1939).

- Naval Bases: Location, Resources, Denial, and Security, Fleet Marine Force Reference Publication (FMFRP) 12-45 (Washington, DC: Headquarters, Marine Corps, 1992); and Advanced Base Force Operations in Micronesia, FMFRP 12-46 (Washington, DC: Headquarters, Marine Corps, 1992).

- Capt Harry Allanson Ellsworth, One Hundred Eighty Landings of United States Marines, 1800–1934 (Washington, DC: Historical Section, U.S. Marine Corps, 1934).

- Millet, Semper Fidelis, 330–31.

- Ellsworth, One Hundred Eighty Landings, vi. See also Allan R. Millet, “Assault from the Sea: The Development of Amphibious Warfare Be- tween the Wars—the American, British, and Japanese Experiences,” in Military Innovation in the Interwar Period, eds. Williamson Murray and Alan R. Millet (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

- David J. Ulbrich, Preparing for Victory: Thomas Holcomb and the Making of the Modern Marine Corps, 1936–1943 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2011).

- See BGen E. H. Simmons’s foreword in 1stLt John C. Chapin, The 4th Marine Division in World War II, 3d ed. (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1976); Lt John C. Chapin, The Fifth Marine Division in World War II (Washington, DC: Historical Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1945); and Capt James R. Stockman, The Sixth Marine Division (Washington, DC: Historical Divi- sion, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1946).

- LtCol R. D. Heinl Jr., The Defense of Wake (Washington, DC: Historical Section, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1947).

- Capt James R. Stockman, The Battle for Tarawa (Washington, DC: Historical Section, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1947), 68.

- Maj Frank O. Hough, The Assault on Peleliu (Washington, DC: Historical Section, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1950), 181.

- Millett, Semper Fidelis, 447.

- Ernest H. Giusti, Mobilization of the Marine Corps Reserve in the Korean Conflict, 1950–1951, 2d ed. (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1967), 2.

- Michael J. Hogan, A Cross of Iron: Harry S. Truman and the Origins of the National Security State, 1945–1954 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998). See also Steven L. Rearden, History of the Office of the Secretary of Defense: The Formative Years, 1947–1950, vol. 1 (Washington, DC: Historical Office, Office of the Secretary of Defense, 1984), 385–422.

- Millett, Semper Fidelis, 456–74.

- Capt Ernest H. Giusti, “Minute Men—1950 Model: The Reserves in Action,” in Our First Year in Korea: Accounts by the Historical Branch, G-3, Headquarters Marine Corps (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps Gazette, 1954), 25.

- Giusti, Mobilization of the Marine Corps Reserve, 1.

- Giusti, Mobilization of the Marine Corps Reserve, 6.

- Millett, Semper Fidelis, 481.

- Benis M. Frank, “The Korean War’s ‘Fighting’ 1st Provisional Historical Platoon,” Fortitudine 19, no. 1 (Summer 1989): 17–18.

- Henry I. Shaw Jr., “The Marine Corps Historical Program—A Brief History,” Fortitudine 19, no. 3 (Winter 1989–1990): 5–7

- Our First Year in Korea.

- Lynn Montross, War Through the Ages (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1944).

- Lynn Montross and Capt Nicholas A. Canzona, U.S. Marine Operations in Korea, 1950–1953, vol. 1, The Pusan Perimeter (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1954); Lynn Montross and Capt Nicholas A. Canzona, U.S. Marine Operations in Korea, 1950–1953, vol. 2, The Inchon-Seoul Operation (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1955); Lynn Montross and Capt Nicholas A. Canzona, U.S. Marine Operations in Korea, 1950–1953, vol. 3, The Chosin Reservoir Campaign (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3, Headquar- ters Marine Corps, 1957); Lynn Montross et al., U.S. Marine Operations in Korea, 1950–1953, vol. 4, The East-Central Front (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1962); and LtCol Pat Meid and Maj James M. Yingling, U.S. Marine Operations in Korea, 1950–1953, vol. 5, Operations in West Korea (Washington, DC: Historical Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1972).

- LtCol Frank O. Hough et al., History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II: Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1958).

- Millett, Semper Fidelis, 518–28.

- See Col Douglas E. Nash Sr., USA (Ret), “The ‘Afloat-Ready Battalion’: The Development of the U.S. Navy-Marine Corps Amphibious Ready Group/Marine Expeditionary Unit, 1898–1978,” Marine Corps History 3, no. 1 (Summer 2017): 62–88.

- Bernard C. Nalty, The United States Marines in the War with Spain (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1959); and Kenneth W. Condit et al., Marine Corps Ground Training in World War II (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1956).

- Bernard C. Nalty, The United States Marines in the Civil War (Washing- ton, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1959); Bernard C. Nalty, The United States Marines in Nicaragua (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1958); Bernard C. Nalty, The Barrier Forts: A Battle, a Monument, and a Mythical Marine (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1959); Elmore A. Champie, A Brief History of the Marine Corps Base and Recruit Depot, Parris Island, South Carolina, 1891–1956 (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1958); Elmore A. Champie, A Brief History of the Marine Corps Base and Recruit Depot, San Diego, California (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1958); Bernard C. Nalty, The Diplomatic Mission to Abyssinia, 1903 (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1958); and Bernard C. Nalty, A Brief History of Marine Corps Officer Procurement (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1958).

- Victor H. Krulak, First to Fight: An Inside View of the U.S. Marine Corps (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1984), 180–81. See also Nicholas J. Schlosser, ed., The Greene Papers: General Wallace M. Greene Jr. and the Escalation of the Vietnam War, January 1964–March 1965 (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps History Division, 2015).

- Henry I. Shaw Jr., The United States Marines in North China, 1945–1949 (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1960).

- Maj John H. Johnstone, comp., An Annotated Bibliography of the United States Marines in Guerrilla-Type Action (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1961); D. Michael O’Quinlivan, An Annotated Bibliography of the United States Marines in the Boxer Rebellion (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1961).

- Maj Marvin L. Brown Jr., The United States Marines in Iceland, 1941–1942 (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1962).

- See preface in Jack Shulimson, Marines in Lebanon, 1958 (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1966).

- Col Thomas G. Roe et al., A History of Marine Corps Roles and Missions, 1776–1962 (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1962).

- Keith B. Bickel, Mars Learning: The Marine Corps’ Development of Small Wars Doctrine, 1915–1940 (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2001).

- See, for example, Bing West, The Village (New York: Harper and Row, 1972); Bing West and MajGen Ray L. Smith, The March Up: Taking Bagh- dad with the 1st Marine Division (New York: Bantam, 2003); and Bing West, No True Glory: A Frontline Account of the Battle for Fallujah (New York: Bantam, 2005).

- Capt Russel H. Stolfi, U.S. Marine Corps Civic Action Effort in Vietnam, March 1965–March 1966 (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1968).

- Capt Moyers S. Shore II, The Battle for Khe Sanh (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1969).

- Shulimson was a scholar on the Marine Corps in the nineteenth century. See Jack Shulimson, The Marine Corps’ Search for a Mission, 1880–1898 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1993).

- Jack Shulimson et al., U.S. Marines in Vietnam: The Defining Year, 1968 (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1997).

- Quoted in Michael A. Hennessy, Strategy in Vietnam: The Marines and Revolutionary Warfare in I Corps, 1965–72 (Westport, CT: Praeger, 1997), 181.

- See Terry Terriff, “ ‘Innovate or Die’: Organizational Culture and the Origins of Maneuver Warfare in the United States Marine Corps,” Journal of Strategic Studies 29, no. 3 (June 2006): 475–503, https://doi. org/10.1080/01402390600765892.

- LtCol William R. Fails, Marines and Helicopters, 1962–1973 (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1978); Maj William J. Sambito, A History of Marine Fighter Attack Squadron 232 (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1978); Cdr Herbert L. Bergsma, USN, Chaplains with Marines in Vietnam, 1962–1971 (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1985); and LtCol Gary D. Solis, Marines and Military Law in Vietnam: Trial by Fire (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1989).

- Charles R. Smith, Marines in the Revolution: A History of the Continental Marines in the American Revolution, 1775–1783 (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1975).

- See Ronald H. Spector, Eagle Against the Sun: The American War with Japan (New York: Free Press, 1985); and LtCol Ronald H. Spector, U.S. Marines in Grenada, 1983 (Washington, DC: History and Museums Divi- sion, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1987), iii.

- Millett, Semper Fidelis, 631–35.

- Maj Charles D. Melson et al., U.S. Marines in the Persian Gulf, 1990–1991: Anthology and Annotated Bibliography (Washington, DC: History and Mu- seums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1992).

- Col Charles J. Quilter II, U.S. Marines in the Persian Gulf, 1990–1991: With the I Marine Division in Desert Shield and Desert Storm (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1993).

- Paul W. Westermeyer, U.S. Marines in the Gulf War, 1990–1991: Liberating Kuwait (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps History Division, 2014).

- Maj Christopher M. Kennedy et al., U.S. Marines in Iraq, 2003: Anthology and Annotated Bibliography—U.S. Marines in the Global War on Terrorism (Washington, DC: Marine Corps History Division, 2006). See also LtCol Nathan S. Lowrey, Marine History Operations in Iraq (Washington, DC: Marine Corps History Division, 2005).

- Col Nicholas E. Reynolds, U.S. Marines in Iraq, 2003: Basrah, Baghdad and Beyond—U.S. Marines in the Global War on Terrorism (Washington, DC: Marine Corps History Division, 2007).

- LtCol Kenneth W. Estes, U.S. Marines in Iraq, 2004–2005: Into the Fray (Washington, DC: Marine Corps History Division, 2011).

- Paul W. Westermeyer, U.S. Marines in Battle: Al-Khafji, 21 January–1 Feb- ruary 1991 (Washington, DC: Marine Corps History Division, 2008).

- Francis X. Kozlowski, U.S. Marines in Battle: An-Najaf, August 2004 (Washington, DC: Marine Corps History Division, 2009); and Col John R. Andrew Jr., U.S. Marines in Battle: An-Nasiriyah, 23 March–2 April 2003 (Washington, DC: Marine Corps History Division, 2009).

- Nicholas J. Schlosser, U.S. Marines in Battle: Al-Qaim September 2005– March 2006 (Washington, DC: Marine Corps History Division, 2013); and CWO4 Timothy S. McWilliams with Nicholas J. Schlosser, U.S. Marines in Battle: Fallujah, November–December 2004 (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps History Division, 2014).

- Dr. Nicholas J. Schlosser, U.S. Marines and Irregular Warfare Training and Education, 2000–2010 (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps History Division, 2015).

- Nicholas J. Schlosser and James M. Caiella, Counterinsurgency Leadership in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Beyond (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps University Press, 2011); and Col Stephen S. Evans, comp., U.S. Marines and Irregular Warfare, 1898–2007: Anthology and Selected Biography (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps University Press, 2008).

- Maj David W. Kummer, comp., U.S. Marines in Afghanistan, 2001–2009: Anthology and Annotated Bibliography—U.S. Marines in the Global War on Terrorism (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps History Division, 2014); Paul W. Westermeyer with Christopher N. Blaker, comps., U.S. Marines in Afghanistan, 2010–2014: Anthology and Annotated Bibliography—U.S. Marines in the Global War on Terrorism (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps History Division, 2017); and Col Nathan S. Lowrey, U.S. Marines in Afghanistan, 2001–2002: From the Sea (Washington, DC: Marine Corps History Division, 2011).

- Paul Westermeyer and Breanne Robertson, eds., The Legacy of Ameri- can Naval Power: Reinvigorating Maritime Strategic Thought (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps History Division, 2019).

- Col George R. Hofmann Jr., The Path to War: U.S. Marine Corps Operations in Southeast Asia, 1961–1965 (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps History Division, 2014). See Paul Westermeyer, ed., The Legacy of Belleau Wood: 100 Years of Making Marines and Winning Battles—An Anthology (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps History Division, 2018).