In many ways, World War I represents a watershed event for the Marine Corps. In preparation for the war, the Corps studied new kinds of tactics, weapons, and organizations, learning how to wage a large-scale land war as part of a combined arms force. During the bloody struggles for Belleau Wood and Mont Blanc, Marines fought a first-class opponent equipped with modern weapons and learned the cost of victory. The Corps also realized the importance of recording and maintaining records of its own history and publishing written accounts for posterity.

Although it still relied on Major Richard S. Collum’s informal history of the Marine Corps, first written in 1874 and last updated in 1903, the Corps found itself after the “war to end all wars” with no official historian of its own to update Collum’s work and write about its participation in that conflict. To correct this shortcoming, Edwin N. McClellan, then a major and freshly returned from the fighting in France, was formally appointed historian of the Marine Corps in 1919 and charged by the Commandant of the Marine Corps, Major General George Barnett, with writing the Corps’ official account. Tasked at first with writing a pamphlet, McClellan’s efforts expanded to encompass nearly every aspect of the Marine Corps’ involvement in that war, including charts, statistics, tables, and an index.2 The Corps was to be the first Armed Service to offer its official history of World War I.

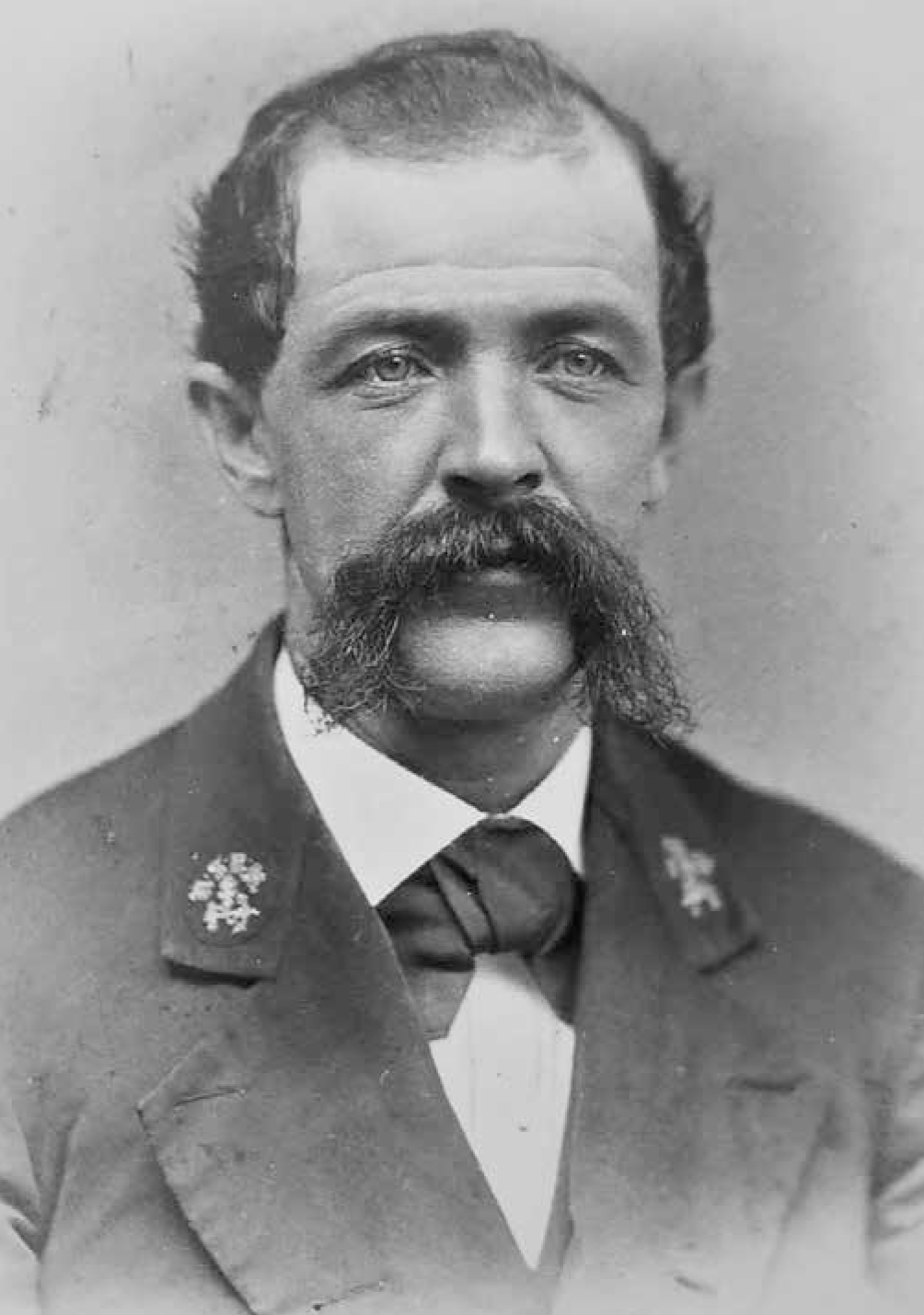

Maj Richard S. Collum, 1905. Official U.S. Navy photo, NH 79199

LtCol Edwin N. McClellan, 1934. Official Marine Corps photo

When The United State Marine Corps in the World War was first published in 1920 by the Government Printing Office, McClellan’s account contained 109 pages of densely packed text. Reprinted several times and augmented with photographs and additional text since, it remains the Corps’ definitive history of that conflict, with the recent 2014 edition totaling 228 pages.3 To write his manuscript, McClellan’s office was augmented by three enlisted men, who acted as research assistants and editors. Shortly thereafter, he began work on what was to be the definitive official history of the Marine Corps, which he envisioned would encompass seven volumes. He never finished it before he retired in 1935, but by then, the Marine Corps Historical Section was an accepted institution.

Just as the Marine Corps considered the creation of a history office after the war, so too were the other Armed Services—which at that time meant the U.S. Army, represented by the War Department, and the Department of the Navy—began considering creating their own history offices during the same period. The U.S. Air Force did not officially exist until 1948, but its accomplishments during World War I were duly recorded by the Army, from which it derived. The U.S. Coast Guard, which until 1915 was known as the Revenue Cutter Service, also participated in the war and took steps to create such an office as well. These various Service history offices evolved in a manner similar to that of the Marine Corps—not in a straight line, never funded sufficiently, and even temporarily dissolved at one time or another—but they have survived and adapted to become the organizations that the Marine Corps History Division works with today.

The U.S. Navy's Historical Office

The U.S. Navy’s history office traces its roots back to the creation of the Navy Department Library in 1794, which focused its efforts on collecting records, maps, books, and other relevant naval documents at its location in the Philadelphia Navy Yard. However, it was not involved in drafting and publishing any works of a historical nature. After 1800, it also began acquiring naval artifacts and various trophies of war, including cannon from captured enemy vessels. In 1814, the library moved to the Washington Navy Yard in the District of Columbia, though it still functioned as a repository for books, documents, maps, and various artifacts rather than an office formally charged with the preservation and publication of the Navy’s history.

In 1879, 14 years after the Civil War had ended, the Navy Department Library was moved to the same building on 17th Street occupied by the State, War, and Navy Departments. For administrative purposes, it was placed under the Navy’s Bureau of Navigation as part of the Office of Naval Intelligence. The U.S. Congress officially recognized the Navy Library in 1882, when that body voted to authorize funds for the library and its staff. The legislation also directed that the Navy Department Library and the Naval War Records Office be combined under one directorship, an action that resulted in a new name: the Office of Naval Records and Library, which made the Navy the first Service with a permanent office dedicated to the preservation and study, though not writing, of military history.4

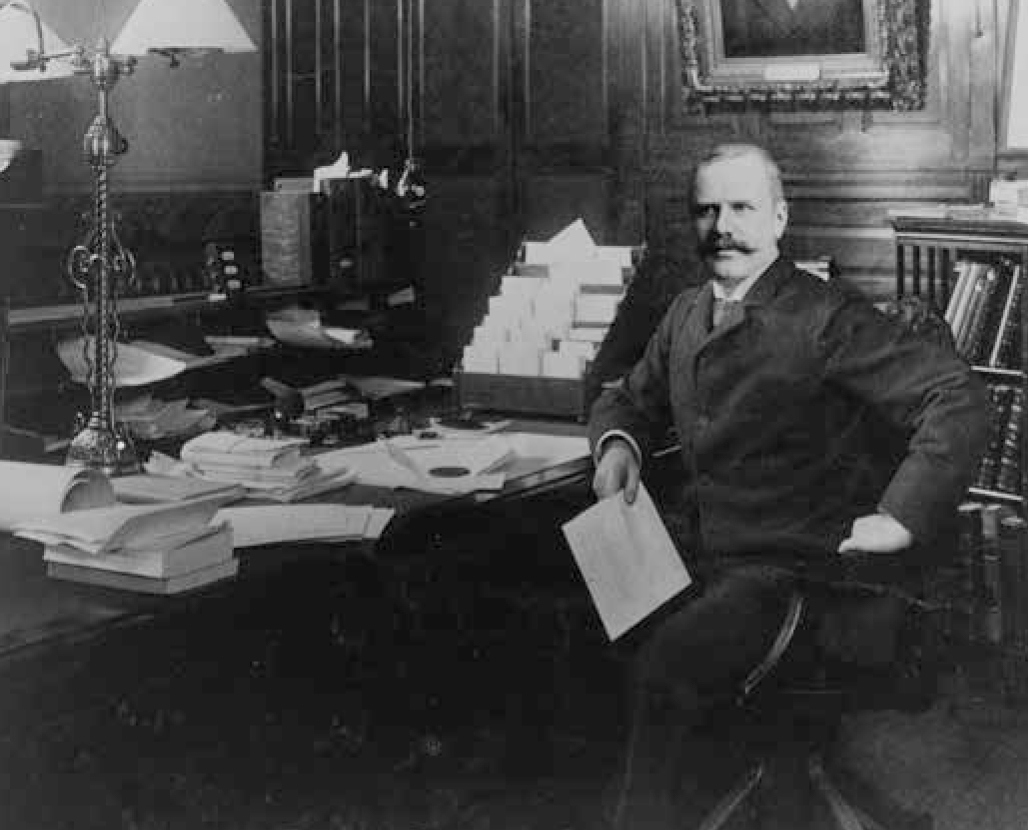

Prof James R. Soley, assistant secretary of the Navy, 1890–93. Official U.S. Navy photo, NH 45022

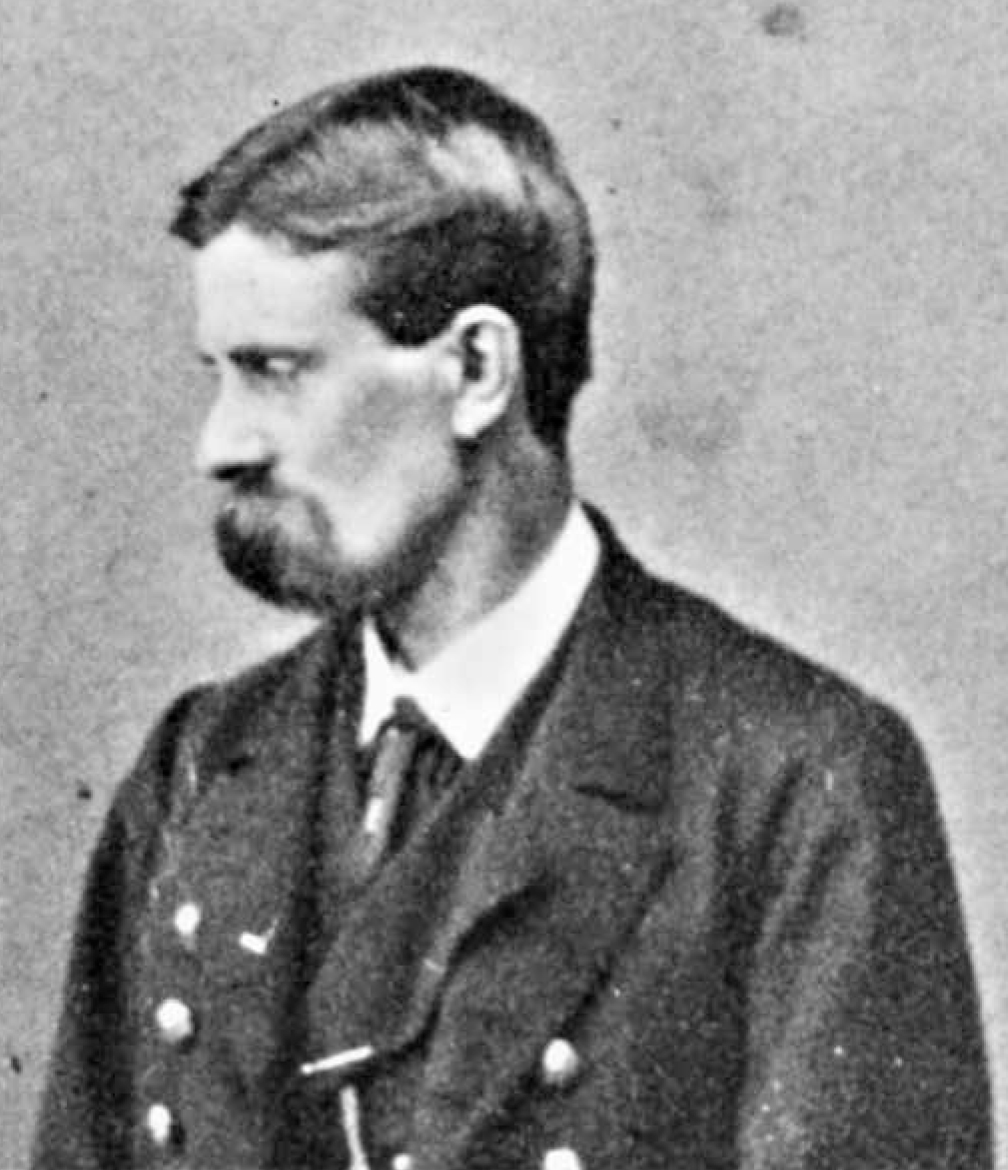

Using the funds allocated, the new history office began work in 1884 drafting and publishing the Navy’s official history of the Civil War, under the leadership of the project’s superintendent, Professor James Russell Soley. Soley was also the first professional historian to serve in that capacity, having had a career as a naval officer, U.S. Naval Academy instructor, and international lawyer and as a prolific author of a number of articles on past and contemporary naval history. While work on the Navy’s Civil War volumes continued apace, Soley was appointed in October 1889 to become assistant secretary of the Navy. Prior to his departure, he selected Lieutenant Commander Frederick M. Wise to serve as the new librarian in charge of not only the library, but all naval war records as well. With the drafting of the various volumes of its Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion completed by 1894, Congress authorized funds to print the first volumes in the series. By the time the project was completed in 1927, 31 volumes had been printed.

When the United States declared war against the Central Powers of Europe in 1917, further work on the Civil War history project was suspended until the end of hostilities. In the meantime, the secretary of the Navy declared on 18 August 1918 that the Navy needed to formally establish a permanent historical section separate from the Office of Naval Records and Library that would operate under the direction of the Chief of Naval Operations.5 This new office, officially titled Historical Section, was tasked with recording and publishing the Navy’s history beginning with its inception, and thus the Navy’s first history office dedicated to writing official histories was created. Tasked with writing not only the history of the war that had been underway for nearly a year, the office was also instructed to gather relevant historical material on foreign navies as well.

As the war neared its end, Admiral William S. Sims, who commanded all U.S. Navy forces operating in European waters, appointed Captain Dudley W. Knox to write the official account of the Navy’s participation in the European theater of war against the Central Powers. This office would operate separately from the newly established Historical Section at the Washington Navy Yard, and to carry out his assignment, Knox was assigned 20 officers and 50 enlisted men to gather documents, conduct research, and begin the task of writing from an office in London. This project was cancelled shortly after it started when the war ended unexpectedly on 11 November 1918. But Knox’s efforts to preserve the historical records of that war were not forgotten.6

A year later, the Navy’s Historical Section and the Office of Naval Records and Library were both placed under a single command, though not merged. On 14 July 1921, Captain Knox was abruptly plucked from his fleet assignment and appointed the director of both the naval records and the library offices and tasked with writing the official history of World War I, a project that he estimated would require several years. Although seven monographs about certain aspects of the war were published in the years that followed, the Navy’s official history of World War I was never completed due to a variety of factors, such as lack of people and money, a challenge that the Army, Navy, and Marine Corps’ history offices were all facing at this time. Knox’s tenure as the curator for the Navy Department, responsible for both the Historical Section and the Office of Naval Records and Library, was to last 25 years and would leave a lasting mark on that institution.

Capt Frederick M. Wise, USN, ca. 1865. Official U.S. Navy photo, NH 63299

Capt Dudley W. Knox, USN, taken while he was officer in charge of the Office of Naval Records and the Navy Department Library. Official U.S. Navy photo, NH 48462

In 1927, the embryonic Historical Section was absorbed by the Office of Naval Records and Library, becoming a single organization.7 In 1930, an attempt to create a Navy museum was undertaken, as the Navy had amassed an impressive amount of relics and monuments; however despite now-commodore Knox’s best efforts, this initial attempt did not succeed. Most of these relics, known as the Dahlgren Collection after the officer who created it, Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren, continued to be maintained at the Washington Navy Yard, while the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis preserved its own collection of Navy artifacts.

Interrupted by the onset of World War II, the Office of Naval Records and Library’s Historical Section was tasked with gathering and compiling the official record of that war, an overwhelming task for which it was not well suited because the majority of its writers were civilians based in Washington, DC, who could not sail with the fleet. This obstacle was partly overcome by Knox when he sought out noted historians such as Dr. Samuel Eliot Morison, a Reserve naval officer who volunteered for active duty and served in a variety of naval theaters during the war. Though he was not officially assigned to the Historical Section, his work resulted in the definitive 15-volume History of the United States Naval Operations in World War II.8 During the war, Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal also created the Office of Naval History in 1944 “to coordinate the preparation of all histories and narratives of the current wartime activities in the naval establishment in order to assure adequate coverage to serve present and future needs and effectively to eliminate non-essential and overlapping effort.” Admiral Edward C. Kalbfuss (Ret) was named to head the newly established office as its director. As established, it was not part of the Office of Naval Records and Library, even though Captain Knox served as Kalbfuss’ deputy director. This new office greatly assisted Knox with his efforts to collect historical data from the ongoing conflict, particularly since all ships and naval units at sea or ashore were required to submit periodic histories to the Office of Naval History. Following the war, both offices were merged into one in 1949, with the new title being the Naval Records and History Division.9

Finally, the U.S. Naval History Division was activated in 1952 and formally established at the Washington Navy Yard, replacing its predecessor. It was charged not only with maintaining the Navy library and historical records and with publishing official histories, but also with storing and cataloging the growing collection of Navy art, photographs, and oral history. Meanwhile, the Naval Historical Display Center was designated as the successor to the Dahlgren Collection in 1961 and was renamed the National Museum of the Navy, which opened in a new building at the Washington Navy Yard in 1963. The museum and Naval History Division were finally merged into one organization in 1971, bringing all Navy historical offices under one roof in the newly formed Naval Historical Center.10

In 1991, the Naval Historical Center assumed responsibility for the Naval History Detachment Boston, which maintained and operated the USS Constitution, the oldest commissioned warship in the Navy’s inventory. Its most recent addition was the creation of the Underwater Archeology Branch in 1996, which is responsible for protecting and studying the Navy’s submerged cultural resources and protect- ing the status of sunken U.S. warships as war graves. The oldest of the Services’ history offices, the Naval History and Heritage Command (its new name since 2008) continues to serve as the nation’s repository for official Navy history and as custodian of its naval artifacts, working in close cooperation with the Marine Corps History Division.

The U.S. Army's Center of Military History

Although it has been in existence since 1775, the U.S. Army did not establish a permanent military history office until August 1943. Until that point, the secretary of war, as head of the War Department, would appoint officers to form committees to write the official accounts of its campaigns. In 1877, the Army began work on the multivolume Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, which became known as the “monumental history of the Civil War.”11 Working as the head of the newly established War Records Section of the War Department’s Publications Office, Captain Robert N. Scott (later brevet lieutenant colonel) worked diligently to collect thousands of official records and to hire a team of writers, who labored for 20 years to produce 128 books in 70 volumes between 1880 and 1901.12 When Scott died from pneumonia in 1887, he was replaced by Colonel Henry M. Lazelle, who relied heavily on his civilian compiler or editor Joseph W. Kirkley to complete the series. The office was disbanded with the publication of its last volume in 1901.13

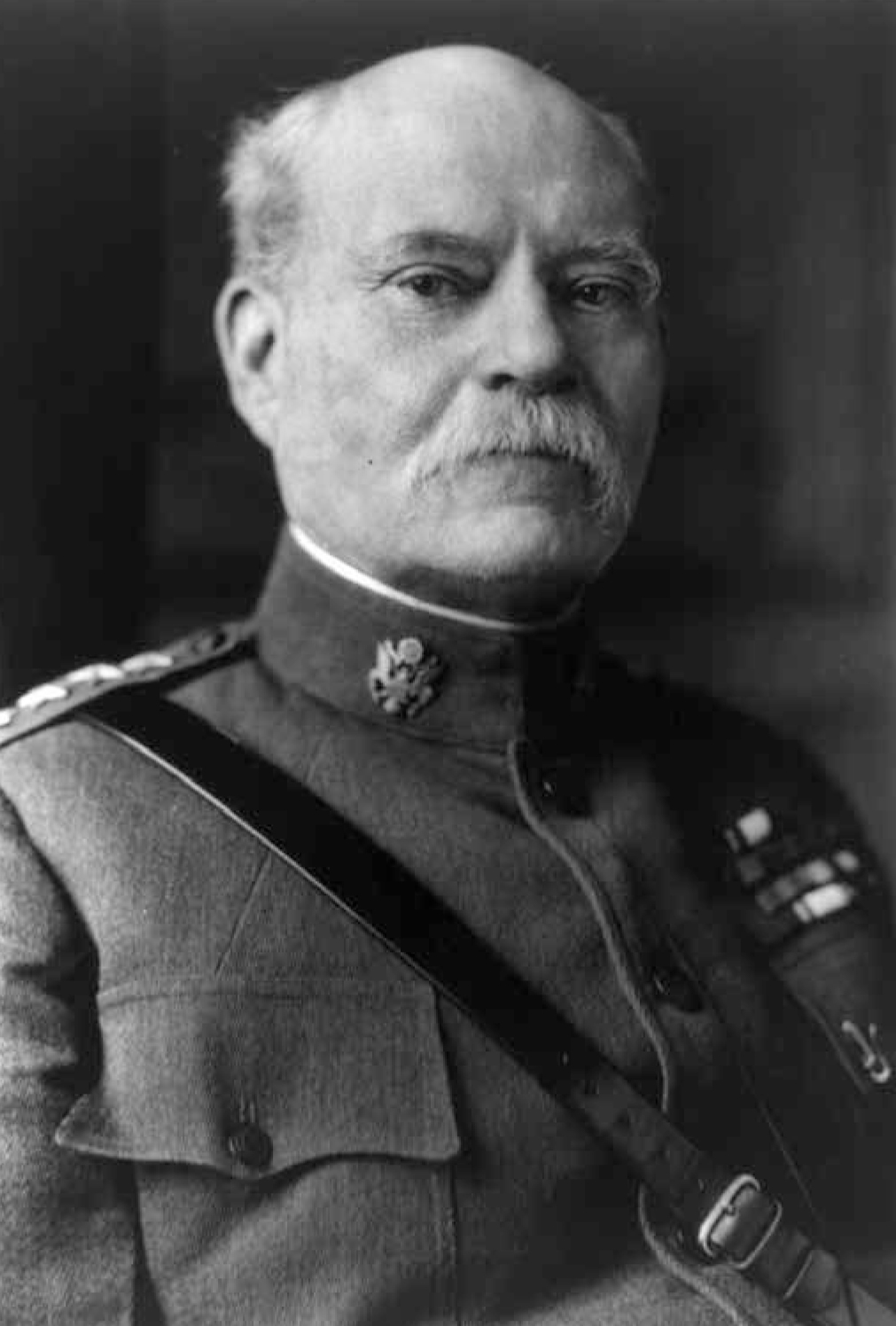

In the immediate aftermath of World War I, the Army, still lacking its own historical office, was directed by its chief of staff, General Tasker H. Bliss, to establish a historical office as a section under his direct supervision. Bliss made his intent clearly known at the outset, stating that the purpose of such an office was to “record the things that were well done, for future imitation . . . [and] the errors as shown by experience, for future avoidance.”14 Before General Bliss could ensure that his intent for the Historical Section was met, he was transferred to France on 23 January 1918 to serve as the American permanent representative to the Allied Supreme War Council.15

Bliss’s successor, acting Chief of Staff General Peyton C. Marsh (subsequently confirmed as chief of staff on 20 May 1918), believed that the needs of the Army would be better served by having the historical office located within the General Staff rather than directly under his supervision. Consequently, War Department General Order No. 41, dated 9 February 1918, was issued, directing that a Historical Branch be established as an element of the Army’s General Staff War Planning Division at the Army War College. The following month, it was activated under the leadership of Lieutenant Colonel Charles W. Weeks with seven officers, fifteen enlisted men, and five civilian employees at Washington Barracks (now Fort McNair) in the District of Columbia.16 Shortly after its activation, a team of eight, including stenographers and translators, was dispatched to the headquarters of General John J. Pershing’s American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) in France, where it collected and organized copies of orders, memoranda, and other official correspondence. Here, it remained until October 1918, when it was transferred to the AEF secretary of the General Staff. Before the war ended on 11 November 1918, the Army’s Historical Branch, including the section in France and the main office at Washington Barracks, had grown to comprise 81 soldiers and civilians and much work had been done obtaining historical records as well as drafting and publishing two historical monographs. How- ever, funding and manpower constraints that arose in the wake of the massive demobilization meant that the Historical Branch had shrunk to 14 officers, warrant officers, and civilian employees by 1920.

General Bliss had envisioned that the Historical Branch would prepare a “complete history of our participation in the World War,” including volumes on mobilization; economic, financial and industrial mobilization; diplomatic relations; military operations; and a photographic history.17 Unfortunately, these plans were scrapped in the wake of the drawdown, which shrank the Army from a wartime strength of nearly four million men to its prewar strength of slightly more than 100,000 in less than two years. The Historical Branch then outlined a more realistic plan that would concentrate on four main areas: the classification of all historical records received, the publication of sets of documents as rapidly as possible, the preparation of monographs on both operations and services of supply, and the publication of an American order of battle in the war.

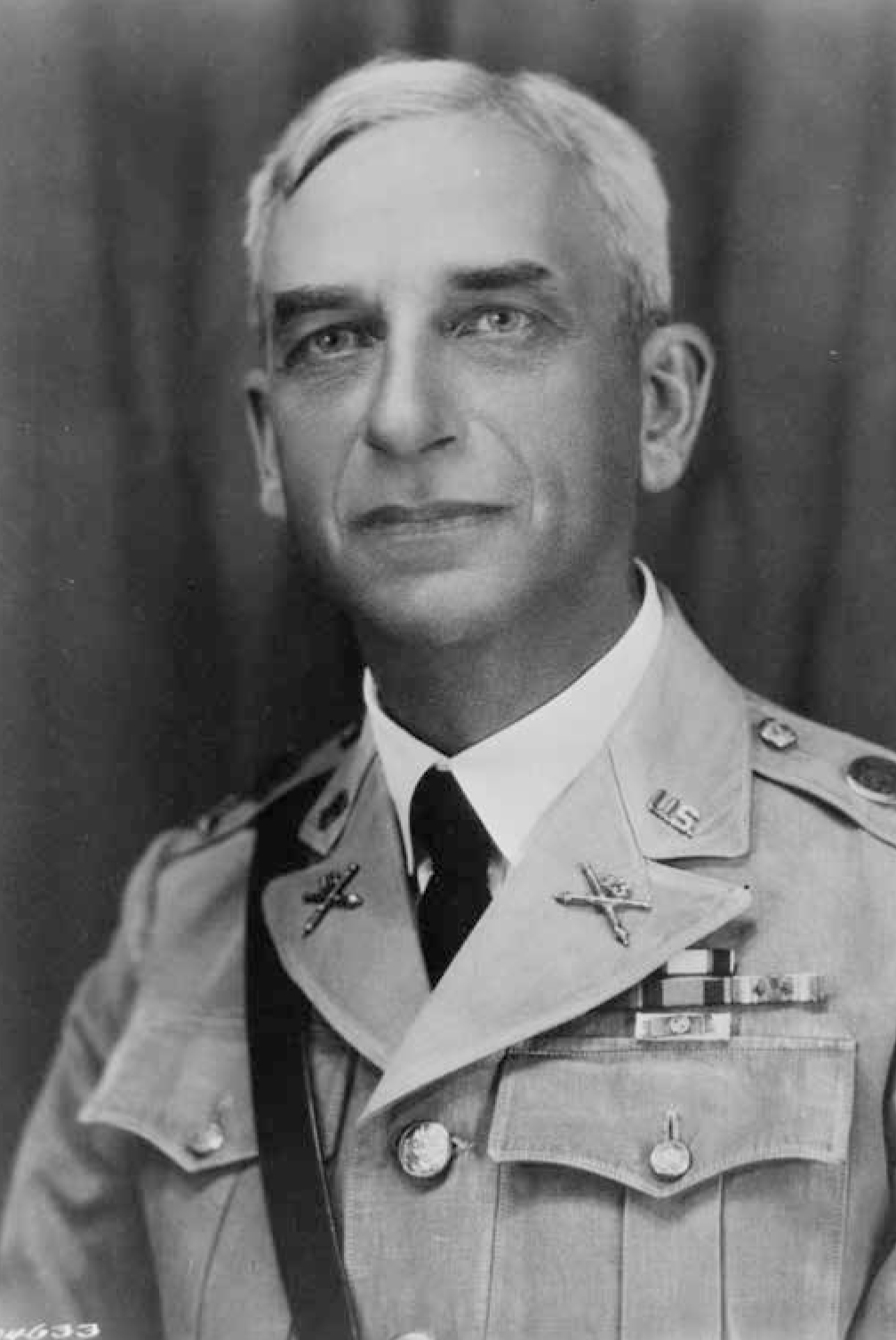

Even then, this less-ambitious plan would be hard to implement. Funds were disappearing, as were the people needed to carry out these tasks. Now reduced to a combined strength of three officers and nine civilian clerks under the supervision of Colonel Oliver L. Spaulding, the Historical Branch struggled to carry out its mission.18 Surprisingly, its authors and editors did manage to write and publish nine historical monographs, ranging from a study of German tactics to describing how best to organize tactical formation for battle, as well as what became volume one of the Allied Expeditionary Force Order of Battle.

On 16 August 1921, the Historical Branch was transferred from the General Staff to the faculty of the U.S. Army War College and renamed the Historical Section, where it experienced an increase in prestige and received, for most of the following decade, the necessary means to fulfill its mandated responsibilities, which included the addition of more academically qualified historians. Another attempt was made in 1925 to draft and publish a comprehensive four-part study of the war, encompassing 57 volumes, but after the first volume was published in 1928, the commandant of the Army War College, Major General William D. Connor, shortly afterward ordered all work to stop and distribution of the existing volume to be suppressed. This was due in part to his sense that the Historical Section had exceeded its mandate by embarking on an analysis of political and economic factors that he believed were beyond the purview of the military profession. With the onset of the Great Depression, the Historical Section was reduced in size even more, but the ban on further work was lifted in 1938.19

Gen Tasker H. Bliss, chief of staff, USA, ca. 1918 during World War I. Library of Congress photo, CPH3A36601

Instead of focusing on writing more monographs, the commandant of the Army War College directed the Historical Section on 14 August 1929 to complete a report on World War I that would unfold in three phases, beginning with searching the files and classifying all World War I documents of historical value, followed by compiling volumes of these documents, and ending with writing the synopses of facts from the complete records of armies, corps, and division and corresponding units.20 This report, which would eventually total 18 volumes of selectively edited AEF records, was eventually titled The United States Army in the World War, 1917–1919. Cited as a “widely representative selection of the records . . . believed to be essential to a study of the history of that war,” the series included some of the most illustrative documents about the war, culled from the large mass of paper generated both overseas and within the various Army posts and headquarters throughout the United States.21

During the 20-year period encompassing 1919 to 1939, the Historical Section at the Army War College was engaged in collating and editing this primary source material, both American and foreign, including captured German records, and deciding which ones should be included in this massive first pass at its World War I history. Once this initial stage was completed, the group moved on to the next phase, which included putting the material into a readily accessible format so it could be used both by Army War College students and the public for future study. No monographs or separate studies would be included. During these two decades, Army officers and civilians assigned to the project would first concentrate on indexing the vast amounts of tactical and technical information contained in the official records, followed by determining which of the thousands of selected individual documents to include and agreeing on the theme of each volume, which would guide the placement of the selected material.

This task was laid aside in 1939 when, with war clouds gathering, the Army took tentative steps toward mobilization. One of the backward steps the Army made was its 1940 decision to reduce the size of the Historical Section, which had an immediate negative impact on the production of the World War I official history. The adjutant general of the Army, Major General Emory S. Adams, halted all further work on the war’s history and also suspended classes at the Army War College that same year, echoing the same quaint sentiments of the former secretary of war, Newton D. Baker, who stated in 1919 that

such a history would be incomplete unless it undertook to discuss eco- nomic, political and diplomatic questions, and the discussion of such questions by military men would necessarily be controversial, and many of the questions . . . would be impolitic and indiscreet for treatment by the War Department.22

Further interrupted by the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the entry into World War II on 7 December 1941, work on the collection of World War I manuscripts languished for four years. Publication did not finally begin until the end of the Second World War, almost 30 years after the first had ended.

Col Oliver L. Spaulding, first director of the Army War College’s Historical Branch, 1919. Official U.S. Army photo, 104633

After overcoming initial resistance from within the Army Staff, on 3 August 1943 the War Department, influenced by General Spaulding’s arguments in favor of bringing back an organizational history office, authorized the creation of a historical division within the Army G-2 Staff Section. Its first director beginning in 1943 was Lieutenant Colonel John M. Kemper, a Columbia graduate with a master of arts degree in history, whose office was established in Room 5B773 in the Pentagon.23 His focus, naturally, was recording and writing the official history of World War II, an effort that resulted in the publication of the Army’s famous Green Book series, titled The U.S. Army in World War II. This monumental endeavor, which ended with the publication of its 78th volume in 1992, still stands today as the benchmark for evaluating official Service history.24 It would not be circumscribed by prewar restrictions on content, which fortunately allowed its authors to freely write about the political, economic, and grand strategic aspects of the war, unlike the authors of the First World War study.

Kemper also ensured that the World War I official history started in 1919 by the War College Historical Section would finally be completed and made available to the public. He oversaw the merging of the Army War College Historical Section into the Army Historical Section in 1947. This became the Historical Section’s World War I Branch, which would finally sever all ties with the newly reinstated Army War College three years later in 1950. Shortly after merging with the Historical Section, the World War I Branch sent its work to printers, beginning with the first volume on 23 April 1948.25 The World War I series was so successful that a full reprint of the entire collection, with a new foreword and introductory chapter, was authorized in 1988. After serving as the chief of the Historical Section for five years, Kemper departed shortly thereafter to become the headmaster of the Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, a position he held until his death in 1971.

LtCol John M. Kemper, first director of the Army’s Historical Section, 1943 (shown here as a West Point cadet). U.S. Military Academy photo

Since the creation of the Army’s historical office in 1943, it has undergone several name changes. Now the Army Center of Military History, it carries on with its original mission, which is to provide historical support to the Army Secretariat and Staff from its office at Fort McNair, Washington, DC. Included in the Center of Military History’s mission is contributing historical background information needed to assist decision makers, writing official histories such as the series on the Vietnam War, facilitating staff actions within the Army Staff, supporting various command information programs at all levels, and providing historical background information for public statements made by Army officials. Along the way, it has taken on the additional mission of managing the Army’s museum system, collecting works of art, and providing support to military schools. It also fulfills the function of assisting with the development of the official Department of Defense names for land campaigns and battles, a task originally fulfilled by the War Department’s Office of the Adjutant General beginning in 1866.

The U.S. Air Force History and Museum Program

Interestingly, the Army Air Corps—which in 1948 became a separate Service, the U.S. Air Force—had already recognized the need to officially record its own history and was directed by General Henry H. Arnold, chief of the Army Air Corps, to establish the Army Air Forces Historical Division in 1942. Under the administration of its first director, Brigadier General Laurence S. Kuter, the office operated under his dictum that “it is important that our history be re- corded while it is hot and that personnel be selected and an agency set up for a clear historian’s job without axe to grind or defense to prepare.”26 Although some accounts of the fledgling Air Corps’ deeds had already been recorded by the Army in its official World War I volumes, the Army Air Forces Historical Division more than made up for the lack of any previous official histories of its formative years by publishing numerous accounts of its role in that war, including squadron histories, histories of various aircraft, and other aviation-related topics. In 1969, the Historical Division was renamed the Office of Air Force History, which reported to the Air Force Chief of Staff.

The Office of Air Force History printed a four-volume series about its role in World War I, beginning in 1978 with the publication of The U.S. Air Service in World War I: The Final Report and a Tactical History.27 Compiled by a team of scholars and researchers and edited by Air Force historian Maurer Maurer, the bulk of the edited volumes consists of original reports from the front lines, as well as reports about logistical challenges faced by a fledgling force engaged in aerial battle for the first time. Much of this information had lain unused since the World War I, when the Army War College Historical Section decided to gloss over most of the material in favor of covering ground campaigns and battles. This work was preceded by the Air Force’s official history of the Second World War, a seven-volume work that appeared in 1983, titled The Army Air Forces in World War II and edited by noted historians Wesley F. Craven and James L. Cate, which rivaled the Army’s Green Book series in detail and completeness.28

Gen Laurence S. Kuter, USAF, 1962. Official U.S. Air Force photo

In 1991, the Office of Air Force History was reorganized and renamed the Air Force History and Museums Program, consisting of several branches that operate independently of one another, though all report to the program’s office in the Pentagon, which provides policy, guidance, and advocacy for the worldwide program. These branches encompass the Air Force Field History Offices located worldwide, the Air Force Historical Research Agency located at Maxwell Air Force Base in Alabama, the Air Force Historical Studies Office at Bolling Air Force Base (at Joint Base Anacostia–Bolling) in Washington, DC, and the Air Force Museums System, which includes the massive National Museum of the U.S. Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio.29

The U.S. Coast Guard Historian's Office

The U.S. Coast Guard, established in 1789 as the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service, was not originally envisioned as a branch of the military, but rather as a law enforcement organization operating under the aegis of the Treasury Department. Rather than controlling the seas, it concentrated on patrolling the nation’s coastal waters, operating lighthouses along the coast, and rescuing those in peril at sea. On 28 January 1915, it merged with the U.S. Life-Saving Service and was renamed the U.S. Coast Guard. That same year, it assumed a military role under the control of the U.S. Navy. During the First World War, it protected Atlantic overseas convoys against the German submarine threat. It has served in every major war since as one of the nation’s five Armed Services.30

Though a history of the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service was written and published in 1905 by Captain Horatio D. Smith covering the period from 1789 to 1846, no official U.S. Coast Guard history was prepared until after World War I, when Commander Charles Johnson began writing an account of the now-renamed Service’s participation in that war after hostilities had ceased. When Johnson died prematurely, his position as Coast Guard historian was filled on 15 June 1921 by Commander Richard O. Crisp, who completed the work that Johnson began. For reasons still unknown, Crisp’s four-volume manuscript, titled A History of the Coast Guard in the World War, was never officially published, though it is available to researchers at the current U.S. Coast Guard Historian’s Office.31 The first history of the Coast Guard, The United States Coast Guard 1790–1915: A Definitive History, written by Stephen Hadley Evans, was published by the Naval Institute Press in 1949, but it did not treat with the junior sea Service’s history of World War I, focusing instead on the 125 years preceding its establishment when it was still titled the Revenue Cutter Service.32

Shortly afterward, Crisp’s office was eliminated in the general postwar reduction in force, following the model of the early Army and Navy history offices. It was not re-established until World War II, when in 1942 Coast Guard Lieutenant Commander Frank R. Eldridge assembled a team of 17 officers, enlisted men, and SPARS (officially known as the U.S. Coast Guard Women’s Reserve) to write the official history of the Coast Guard’s participation in the war under the umbrella of the Coast Guard Headquarters’ Public Information Division. This 30-volume effort, officially titled The Coast Guard at War, concluded with the publication of its final volume on 1 January 1954.33 Their work completed, the Coast Guard Historian’s Office was once again disbanded that year, though a one-volume work by one of its team members, Malcolm F. Willoughby, was published and used as a standard historical text at the U.S. Coast Guard Academy.34 The Coast Guard’s Historian’s Office was not reestablished as a permanent institution until 27 November 1970, shortly before the end of the Vietnam War, but in the intervening years its historians have worked diligently to make up for the gaps and shortfalls in its history, including adding an extensive library and building an impressive collection of artwork and photographs. After 1993, the Historian’s Office also assumed responsibility for operating the Coast Guard Museum in New London, Connecticut, located on the grounds of the U.S. Coast Guard Academy.35 Along with the rest of the Coast Guard, the Historian’s Office was transferred from the control of the Treasury Department to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security in 2002. Now located in Washington, DC, it is led by a U.S. civil service chief historian supported by a staff of six historians (two of whom operate the Coast Guard Museum) and two area historians. The Coast Guard Historian’s Office, though the smallest of all the Armed Services, pursues an ambitious program of not only publishing official histories chronicling its past accomplishments but also capturing contemporary events shortly after they unfold, including the Coast Guard’s response to Hurricane Katrina.

Capt Horatio D. Smith, U.S. Revenue Cutter Service, 1904. Official U.S. Coast Guard photo, 113544

Coast Guard Cdr Richard O. Crisp shown here as a midshipman in 1883 prior to World War I. Official U.S. Coast Guard photo, 113544

Other Military History Offices

Two other U.S. government military history offices were created in the wake of World War II: Historical Office of the Office of the Secretary of Defense in 1949 and the Joint History Office for the Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in 1955. Both had their genesis in the National Security Act of 1947, when their parent organizations, the Defense Department and the Joint Chiefs of Staff were established by law, replacing the former War and Naval Departments and consolidating them under one secretariat.36 The first office was created to document the history of the Office of the Secretary of Defense since its inception in 1949, while the other served to do the same with the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Since neither historical organization can trace its origins back to World War I or the immediate post–World War I era, this article will not go into further detail, though readers are encouraged to visit their respective websites if they wish to learn more.37

Conclusion

While each of the Armed Services’ history offices have followed a winding path since World War I, all have secured solid budgetary and organizational footing in the years since. Influenced by funding and legislative challenges, personnel cuts, and conflicting philosophies about the proper role of military history in the modern era, they have seen the size of their organizations ebb and flow depending on the conflicts that the nation has experienced during the past century. Initially possessing relatively thin academic and institutional credentials to pursue their missions, all of these history offices have raised the bar and now en- joy far more professional respect and credibility than their predecessors. Most importantly, they have not lost sight of their true missions: to preserve the histories of the Services in the defense of their nation. This they continue to do, recording the things that were done well, the things that were not done well, and everything in between.

•1775•

Endnotes