PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

In his memoirs published shortly after the Great War, Colonel Albertus W. Catlin, former commander of the 6th Regiment of Marines at Belleau Wood, remarked with pride on how his men had conducted themselves in battle. “Can we read what our college boys did in Belleau Wood,” he asked readers, “without thanking God that the soil trod by Washington and Lincoln, the Pilgrim Fathers and the builders of the great West, can still produce men of such stuff as that?”2 For Catlin, the Marines’ cause was a high and holy one. America “went into this war solely to save the ideals of Christianity from destruction,” he wrote. “It is my country that sent the flower of its manhood to fight and die for that cause.”3 His Marines proved to him and to the rest of the country that America still made men of great quality—men that could proudly stand with the manly generations that came before.

Historians identify the June 1918 Battle of Belleau Wood as one of the most pivotal events in Marine Corps history. The bulk of the battle’s traditional scholarship has focused on its operational aspects.4 The question of why the battle became culturally significant for Marines and for the contemporary American public has received scant attention, however. This article addresses that question by exploring the shared cultural ideals between Marines and American society. Americans understood the Great War as a test of manhood. At the Battle of Belleau Wood, Marines demonstrated that American men were strong, courageous, and willing to sacrifice themselves for a high and noble cause. This understanding helps explain why the battle was significant to Americans in the summer of 1918 and why it has been important to Marines ever since. The Corps proved to the public that American manhood was second to none and could pass the test of war.

Belleau Wood is a familiar concept among Marines even though the war in which it was fought seems to attract little popular attention compared to the other, larger world war of the twentieth century. Americans may have celebrated the victorious return of their troops in 1919, but Kimberly J. Lamay Licursi has argued recently that “Americans simply forgot the war after the first few parades welcoming doughboys home,” because their public memory of the Great War “never congealed into a consensus view, which would have helped create a sustaining and coherent memory.”5 After the war, society moved on quickly without ever forming a lasting and significant memory of the conflict within American culture. This is simply not the case with the Marine Corps. As an institution, the Corps remembers well the long summer of 1918, the battles, the gas, and those who fell in the woods and wheat fields of France.

Belleau Wood stands out prominently among the Marines’ collective memory in part because of the efforts of Marine Corps historians (many of whom were Marines themselves) over the decades. Every general history of the Marine Corps published since 1918 has given special attention to the significance of Belleau Wood.6 Paul Westermeyer’s recent assertion captures well how Marines have attached meaning to a battle that many outside the Corps simply have not; at Belleau Wood, “Marine tenacity and media savvy catapulted the Corps into even greater public consciousness, cementing the Marine Corps’ self-proclaimed reputation as an elite force into reality.”7

Marine Corps historians argue that the Great War offered many Marine officers important lessons in tactics, logistics, artillery, and air support that would be used later in amphibious doctrinal development. Allan Millett claims that “six months of extensive combat in France gave the Marine Corps enough practical experience to sustain two decades of serious study on the problems of attacking an entrenched enemy, problems particularly appropriate for an amphibious assault force.”8 Marines also “proved” that they were elite warriors.9 Heather Marshall’s “‘It Means Something These Days to be a Marine’ ” argues that Belleau Wood and the Great War “was the coming-of-age story, the fulfillment of everything it had sought to become on paper since the late nineteenth century,” because the war reinforced Marines’ carefully constructed image as the country’s best troops.10

Col Albertus W. Catlin. Marine Corps History Division

But many Marine historians, and even many actively serving Marines today, have forgotten a significant historical component about the Marines of the Great War. Lost among the drum and bugle histories of Belleau Wood and the war are the Corps’ claims to be good for the young men of the nation. This is surprising when one thinks about it. Marines, throughout the twentieth century, have claimed, as Victor Krulak did in the 1950s, that they are “masters of an unfailing alchemy which converts unoriented youths into proud self-reliant stable citizens.”11 Within the context of the Great War, these claims came in the form of appeals to manhood.

American Manhood

Before U.S. entry into the Great War, the Corps claimed to give young, middle-class white men a chance to become fit, develop good character, see the world, and become “real men.” The Marine was strong, disciplined, clean of mind and body, and assertive—embodying the Victorian manly ideal promoted by many contemporary civilian authors at the time.

According to American sociologists, physicians, politicians, and preachers of the time, manhood was a many-sided thing. Manhood was a stage in one’s life that came after boyhood and before old age. Metaphorically speaking, it was a national resource, something that was grown and harvested. The term manliness tended to mean physical, mental, and moral manifestations of one’s manhood. Strength, self-control, courage, and kindness were all manly qualities.12 Therefore, it tended to make up the bulk of one’s character.13

Manhood could be molded and hardened like steel. Therein lay the foundation of the Marines’ appeal: they shaped men into their own image. They claimed to recruit the finest specimens of American manhood and make them even better. The result was a strong, brave, clean, and morally upright man. He would be a proud and worthy citizen who had earned respect through his years of service, training, and struggle in the Marine Corps. Becoming a Marine benefited the man; being a Marine benefited the nation. As men became manlier, so did the country. Manhood could weaken, become sick, tainted, and corrupted. People took that risk seriously because many saw healthy manhood as essential for both the man and the nation. R. Swinburne Clymer argued in 1914 that the United States had much to lose if its manhood was weak. “The moment a nation loses its sense of manhood and strength,” he wrote, “at that moment does it begin to decay and to decline.”14 A people without strong manhood risked decline and foreign subjugation at the hands of manlier nations. Therefore, the United States needed “Manhood—virile, vigorous, strong, self-reliant, self-assertive manhood” to survive the age.15 Officials in the federal government echoed these sentiments. “A nation stands or falls, succeeds or fails, just in proportion to the high-mindedness, cleanliness, and manliness of each succeeding generation of men,” claimed a writer for the U.S. War Department.16

Leading up to the Great War, many American intellectuals, public figures, politicians, and military officers argued that the men of their country suffered from emasculation. The closing of the frontier, the concentration of capital, and rapid industrialization compromised manly individualism that was founded on the ability of men to own their own land, control their own labor, and become economically independent.17 Healthy manhood kept a nation free from destructive vices, tyranny, and bondage.18 Real manhood manifested itself, even became stronger, during times of trial, adversity, and struggle.19 During the Great War, Victorian ideals of manhood found “more concrete expression,” according to Peter Filene. Marine recruiters would have probably agreed with his claim that “through the crucible of combat a boy would emerge a man.”20 Seemingly immune to the emasculating effects of modern society, Marines promised to reinject the element of struggle and adversity deemed necessary for assertive manhood into men’s lives.

The term masculinity became fashionable around the turn of the twentieth century largely in response to the white middle class’s paranoia concerning the strength of its own manhood.21 While manhood was primarily about such inner qualities as character and morality, masculinity comprised more physical aspects. It had to do with appearances, activities, ways of speech, and even virility.22 Femininity encompassed its opposite. The male body was important to subscribers of both Victorian manhood and the new masculinity. But followers of the latter demonstrated their manliness less through work or moral uprightness and more through consumerism and muscular masculinity. Athena Delvin put it succinctly when she argued that the new form of men’s culture was “more physical and less intellectual, more competitive and less spiritual, more strenuous and less sensitive.”23 Strenuous activity became important precisely because the nature of middle-class work had changed. Masculinity needed demonstration in other ways since manual labor now largely fell to the working classes.

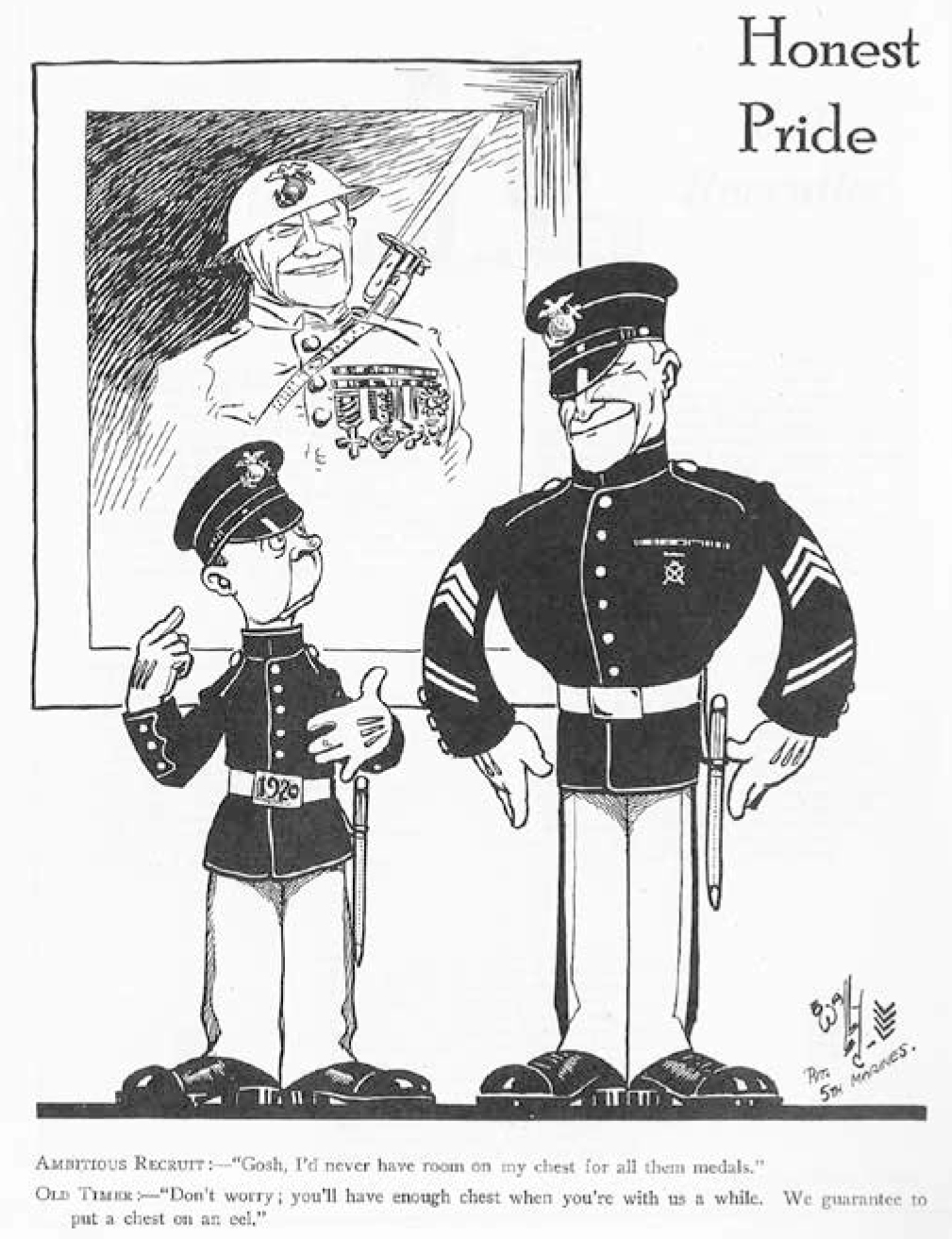

Marines’ wartime images spoke to these insecurities. Sharply dressed Marines pervaded their own imagery to illustrate how the Corps could make recruits more masculine.24 A cartoon image entitled “Honest Pride” shows a diminutive Marine private who has just entered the Corps looking up to a sergeant who is taller, has a thicker chest, broader shoulders, and stronger jaw line (figure 1). The new Marine is impressed by the sergeant’s medals and exclaims, “Gosh, I’d never have room on my chest for all them medals.” The old timer replied, “Don’t worry; you’ll have enough chest when you’re with us a while. We guarantee to put a chest on an eel.”25 This image conveys the physical attributes men supposedly gained while in the Corps. The sergeant’s service in the Great War adds to his masculinity and prestige; in the background is a picture of him wearing the uniform that Marines wore on the western front with combat medals on his chest.

Figure 1. “Honest Pride.” The Recruiters’ Bulletin, December 1919

The Test of Manhood

Civilians and Marines argued that the Great War would put their manhood to the ultimate test.26 That was how many justified conscripting hundreds of thousands of young men into the military and then sending them overseas to fight the Germans. A preacher who addressed Congress in the spring of 1917 called the draft “legislative action which will prepare, and build up the young manhood of America” so it would be “fit to take its place and to defend American rights and liberties.”27 Marines understood and used these ideas about manhood as well. “War puts manhood to a tremendous test, and be it said to a man’s credit, that the coward is the exception, not the rule,” a writer for the Marines’ Magazine claimed.28 For a Marine who runs from battle, “never in his conscious moments can he drive away the specter of his failure to do his manly duty.”29 The consequences of failure were profound because an unmanly Marine failed not only himself but his comrades and his country.30 The challenge of war made men out of those with the courage to face it. Courage was a common aspect of manliness in the Great War era. “Without courage, a man is a poor specimen of a man, hardly worth calling a man,” wrote one civilian author.31 “Never was there a time in the history of the human race when real sturdy manhood, manly vigor and manly courage counted for as much as they do now,” claimed another.32 This rhetoric that linked courage with manliness pervaded Marine writings too. “We wanted to test our courage and manhood, facing death by shrapnel, cold steel, ball cartridge and gas,” Marine Sergeant Arthur R. Ganoe wrote.33 “If he plays a man’s part,” read the Marines’ Magazine in July 1917, “he is consciously the victor over danger, over hardship, over the temptation to avoid the difficult duty, over himself; he can look upon his destiny—yes, upon death itself—with clear eyes, unashamed and unafraid.”34 Essentially, this author encouraged Marine audiences to live up to the Victorian manly standards and imagery that they promoted among each other. A former congressman turned enlisted Marine, Sergeant Edwin Denby, made sure recruits at Parris Island, South Carolina, understood what was at stake for their manhood.35 Marines had to conduct themselves honorably and come back home clean and upright. “Nowhere in the world does a man stand more squarely on his own feet, to make or mar his character, than in the military service,” he said. “If you want to go back worthy to look your women in the face . . . it is up to you, men.”36 Denby spoke to the deleterious impact that alcohol and sexual contact with diseased women had not just on men’s honor but their health as well. Often, when progressives spoke of “cleanliness,” they meant clean bodies free from not just dirt and grime but also from venereal diseases. Around this time American physicians and preachers associated “clean living” with strong and healthy manhood while “lust, uncleanness, drink, gambling, swearing, lying, dishonesty, irreligion” could “ruin our Christian manhood.”37 Sergeant Denby drew on these ideas when he spoke with recruits about how the Corps and the war would test them. Many Americans perceived the war as a matter of honor. President Woodrow Wilson described the situation as such to persuade the American public of what was at stake:

What great nation in such circumstances would not have taken up arms? Much as we had desired peace, it was denied us, and not of our own choice. This flag under which we serve would have been dishonored had we withheld our hand.38

American writing around this time took on chivalrous tones. The Germans insulted the United States with unrestricted submarine warfare that drowned American civilians. German foreign minister Arthur Zimmerman’s telegram to Mexico City called on Mexicans to invade the United States. To restrain from violence would have meant shrinking in the face of the enemy. That was a decidedly unmanly thing for a nation to do. On the congressional floor, one orator proclaimed:

I regret that we are to have war; but if we are to maintain our self-respect, if we are to encourage the cultivation and development of those virile and patriotic virtues among our citizens, without which our Government cannot and should not survive, if we are not to become the laughing stock of mankind, mocked at and reviled by every other nation of the world, if we are not to be derided and sneered at as a Nation of degenerates, of money changers, and of cowards, is anything left to do consistent with a decent self-respect than to acknowledge the unquestioned fact that the German Government has waged war against us, to accept the challenge that has been so recklessly repeated in continued acts of war and aggression against us, and to meet it like and in the only manner befitting a great and a patriotic and manly nation? 39

Germany had thrown down the gauntlet and American manhood would have to accept the challenge or live in disgrace.

Chivalry coursed through Americans’ wartime perceptions of their own manhood.40 Popular conceptions of true manliness consisted of self-control and the courage to sacrifice for the greater good. A man needed courage “to play the man in life, to put his life in for all it is worth—this sort of manliness rings true, and often sounds its clear note of chivalry, nobility and Christian knightliness,” wrote George Walker Fiske.41 Even before America declared war on Germany, writers described American men as chivalrous. One characteristic of this was caring for others and helping people in need. One author wrote, “we . . . must recognize our American man as the knightly soul of the twentieth-century.”42 In the context of World War I, Americans and Marines saw themselves as chivalrous crusaders sent to rescue their allies from German barbarity.

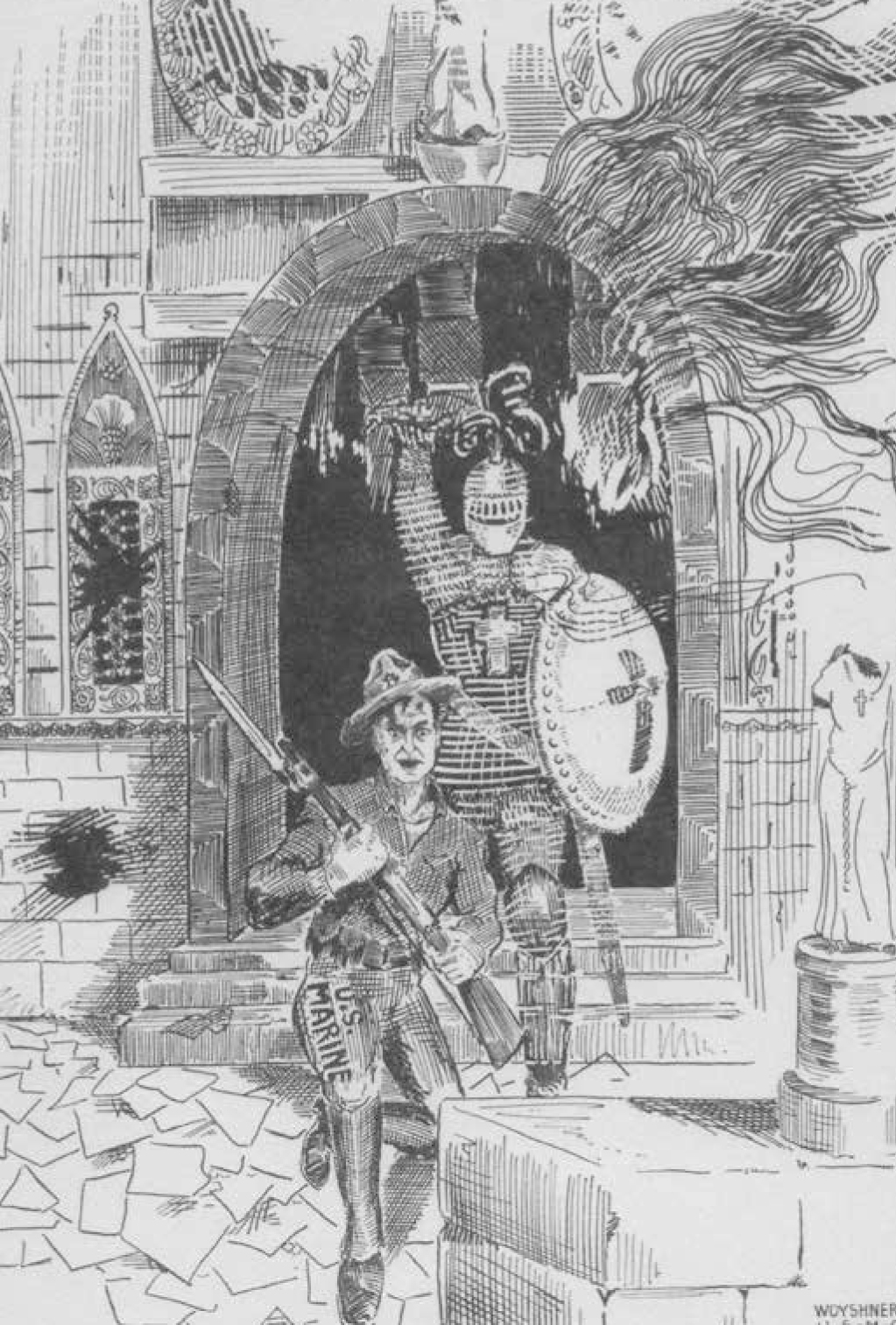

Chivalry, with its emphasis on honor, Christianity, and battlefield prowess, was a much older cultural understanding of manliness that appeared often in Marine wartime imagery. In one image in the Marines’ Magazine, a Marine is depicted charging through a fire- and smoke-licked door of a church. Behind him is a crusader bedecked in armor with his sword drawn (figure 2). The artist saw the Marines as the modern day equivalent of crusaders of old sent to fight for a high and holy cause (democracy, in this case) in a foreign land against infidels (the Germans).

Figure 2. “The Crusaders: The Old and the New.” Paul Woyshner, Marines’ Magazine, June 1917

Two additional images conveyed the same theme of Marines coming to the rescue of Western civilization. The first depicts a small Marine with a bayoneted rifle chasing a caricature of the European war fleeing in terror; above him is a feminine-looking angel of peace (figure 3). The second image again shows a Marine confronting a savage-looking German to save civilization, personified here in the form of a helpless woman on the ground; behind them, Europe burns (figure 4). Both highly romanticized and symbolic images convey the belief that Marines saw themselves as brave men out to save civilization. This imagery was founded upon the demonization of the German, the feminization of civilization, and the masculinization of Marines. Germans in these images appear barbaric and animalistic. Civilization appears in both images either as a woman supporting or being saved by the hero: the U.S. Marine. The savagery of the German is important in these images because of the stark contrast it creates with the other two figures. In these images, German barbarity enhanced the manliness of the Marine and the femininity of the woman. This artwork reflects American writings and speeches that demonized German soldiers and painted them as savages who had lost their manhood to zealous militarism and barbarity.43 Marines hoped to demonstrate that Americans had not parted ways with their manhood the way the Germans had through their cruelty. They would stand up to the Germans and defeat them, the way knights of old slew monsters in fairy tales. Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels spoke of this quest as a great opportunity for the young men of America. Fate had given them the chance to be heroes and to make the world a better place. To the Naval Academy’s 1918 graduating class he said,

Fortunate youth! Fortunate because it is given you to prove that the age of chivalry is not dead—that chivalry was never more alive than now. The holiest of crusades was motivated by no finer impulse than has brought us into this war. To prove that life means more than force; to prove that principle is still worth fighting for; to prove that freedom means more than dollars; that self-respect is better than compromise; to be ready to sacrifice all so that the world may be made the better—what nobler dedication of himself can a man make?44

The young men going off to war had the chance to demonstrate American valor and honor. An entire American army, and two regiments of Marines in France, were about to get this opportunity.

Figure 3. “U.S. Marine and European War.” Charles Elder Hays, Marines’ Magazine, October 1917

Figure 4. “The Rescuer.” J. H. Ambrose, Marines’ Magazine, August 1917

The Sacrifice of Manhood

Costly attacks across the wheat fields into Belleau Wood and its surroundings hold a strong place in Marine lore in part because the 5th and 6th Regiments suffered 1,087 casualties in one day. One month of combat for those woods yielded more than 4,598 casualties in the 4th Brigade alone.45 These casualties became a testament to Marine character and manhood. Shortly after the Armistice, three veteran Marines, Kemper F. Cowing, Courtney Ryley Cooper, and Morgan Dennis, published “Dear Folks at Home---”: The Glorious Story of the United States Marines in France as Told by Their Letters from the Battlefield.46 The book is full of masculine imagery presented in prose and graphic art. The editors picked letters for public consumption, which transformed them from personal missives into public expressions of Marine masculine culture. Through these letters, “Dear Folks at Home” also captures a carefully curated version of Marines’ combat experience.

For much of the collection, Cowing and Cooper culled letters that contained ripping yarns of combat, danger, and Marine prowess. These letters were full of bravado to show readers the stuff of which Marines were made. Private Walter Scott Hiller expressed this pride to his mother when he wrote home from the front, “Do you think any man would regret being a part of such an organization, that have proven to be real fighters, that can go up against the Kaiser’s best-equipped and well-trained forces and give them the defeat we did? Not this man.”47 There was no cynicism or irony in these letters, which would later become common themes in post–Great War literature.48

These letters from France often expressed notions of manhood and sacrifice. One gets the impression that Marines fought and died at Belleau Wood with smiles on their faces. Lieutenant Merwin H. Silverthorne told his family that they were happy to go over the top and fight the Germans.

The first time I went “over the top” was on June 6th. Oh, what a happy bunch we were! I and the best friend I had were shaking hands with one another, happy and exultant in the fact that at last we were “going over.”49

When Silverthorne’s friend (a Marine he identifies as Steve Sherman) died from machine gun fire during their assault across the wheat field, he referenced his fallen comrade’s manliness explicitly: “He had met his end, but he met it like a hero, an American, and a man.”50

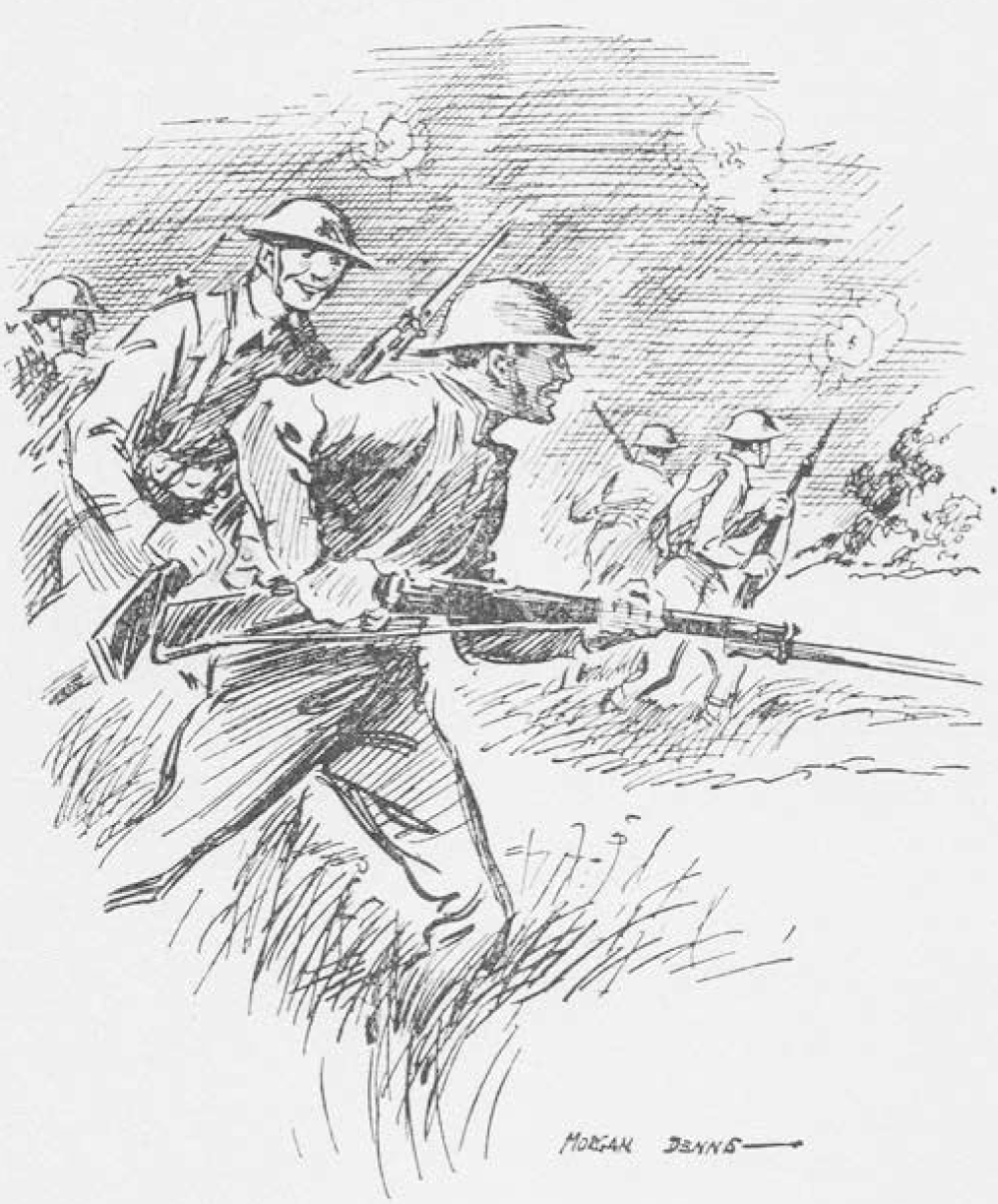

Silverthorne’s friend apparently died happy, at least according to the Marines who saw him fall: “They all are unanimous in saying he fell fighting with his face toward the enemy and a smile on his face.”51 Corporal John F. Pinson’s letter home also spoke of Marines enjoying the battle because it got them out of the trenches and into open warfare. “It was a real battle, and being in the open through wheat-fields and farmlands, was much to the Americans’ liking,” he claimed.52 According to Pinson, Marines enjoyed the bayonet charge across the wheat field. “The boys all swung into action,” Pinson wrote, “laughing and kidding each other as they charged the German machine guns as if they were at a drill, dropping every twenty yards or so to rake the German lines with rifle and machine-gun fire.”53 The editors of “Dear Folks at Home” must have found this last quotation particularly inspiring. They used a drawing by Morgan Dennis to depict the very scene that Pinson described. The Marines in this picture seem happy conducting the attack, exploding shells notwithstanding (figure 5).

Figure 5. “The Boys All Swung into Action Laughing and Kidding Each Other.” Morgan Dennis, “Dear Folks at Home---”

Cowing and Cooper used other images by Dennis to depict scenes of aggression and bravery that Marines described in their letters. Private E. A. Wahl wrote,

The spirit of our men is wonderful. It is be- yond the wildest imagination. They walk right into the rifle and machine-gun fire in the most matter-of-fact way. They have just taken the Boches off their feet.54

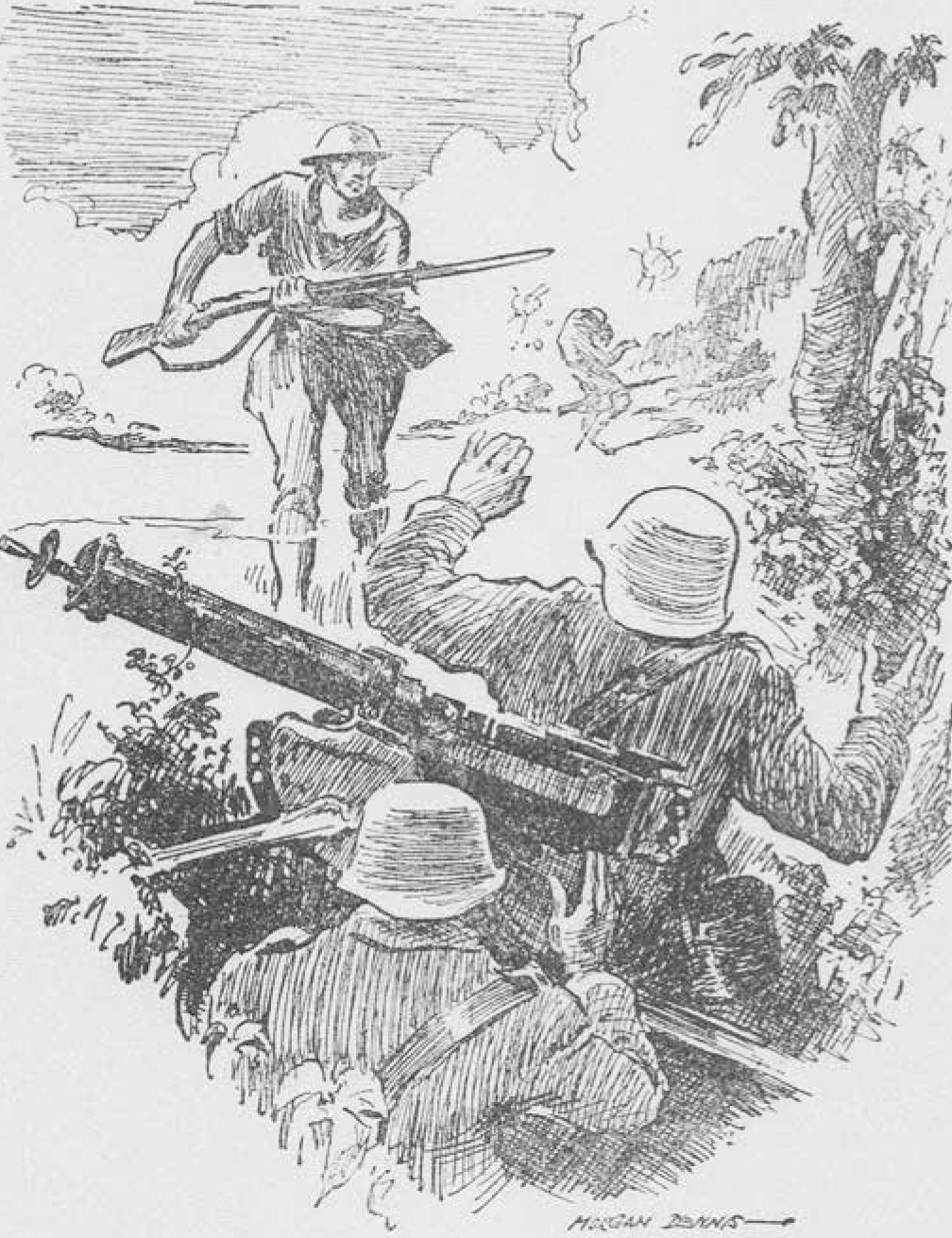

Captain George W. Hamilton wrote about the first day of the Battle of Belleau Wood (6 June 1918), when his company assaulted across a wheat field under heavy German machine gun fire. The 49th Company, 5th Regiment, suffered heavy casualties that day. But his telling, accompanied by a drawing of a Marine charging a German machine gun crew, gives the impression that this was just another example of courage and prowess (figure 6). “It was only because we rushed the positions that we were able to take them,” he claimed, “as there were too many guns to take in any other way.”55

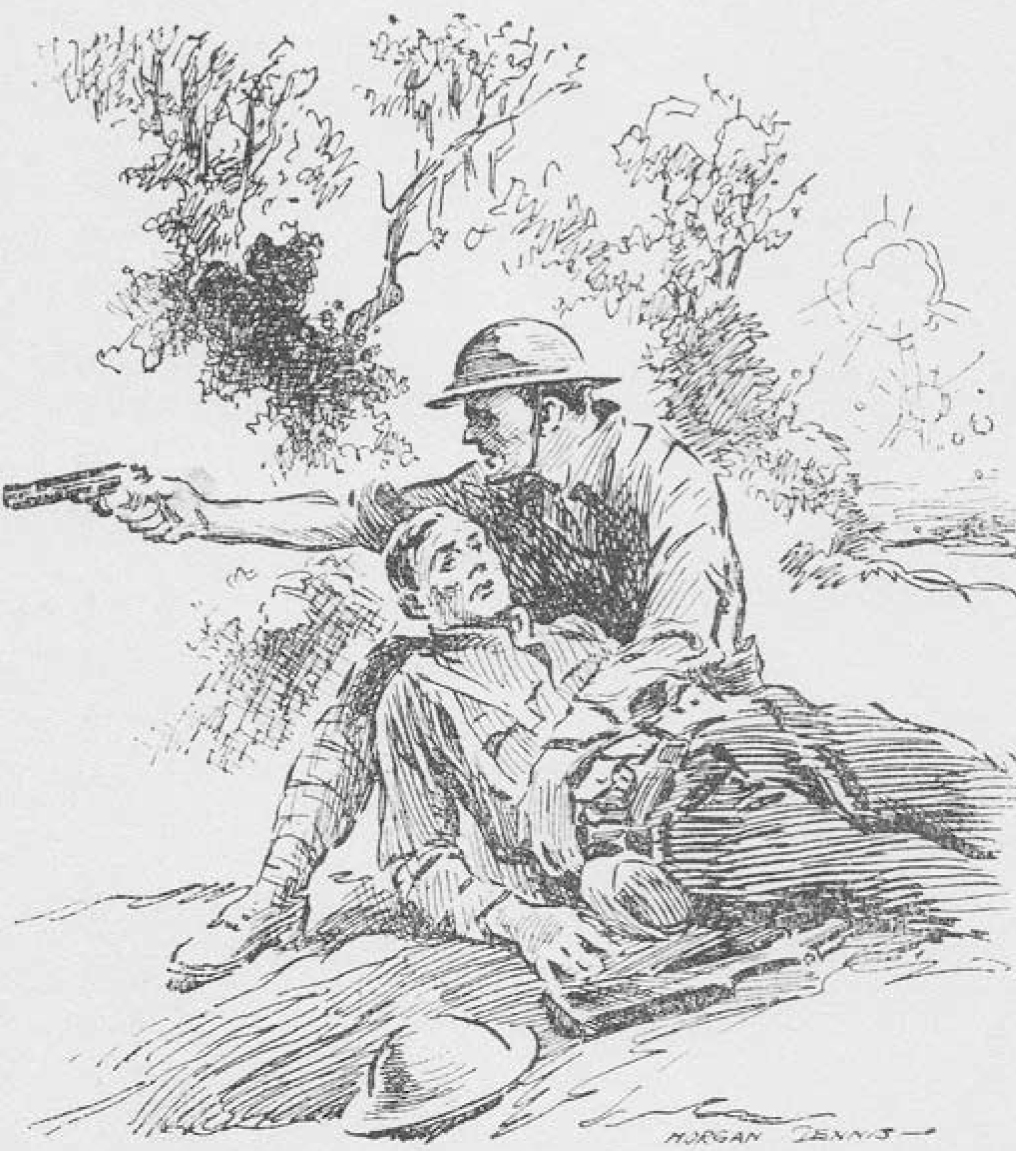

Another image depicted a story told by Major Henry N. Manney Jr., the quartermaster of the 6th Regiment. According to Manney, the battle was deadly, but “the Marines lived up to their reputation and even bettered it. This is open warfare, just our style,and nothing could be finer than the way our men went to it.”56 The image that accompanied Manney’s letter depicts a Marine protecting a wounded comrade. Together, they lay next to a thicket with artillery shells bursting midair in the background. The wounded Marine stares off into the distance, while dogged determination marks the face of his friend, protective but still battling (figure 7).

Figure 6. “It Was Only Because We Rushed.” Morgan Dennis, “Dear Folks at Home---”

Figure 7. “This Is Open Warfare, Just Our Style.” Morgan Dennis, “Dear Folks at Home---”

To the compilers of this collection, tales of bravery and sacrifice meant Marines were exceptional men. Lieutenant Silverthorne wrote of losing some of his friends in combat. “A pang of deep sorrow will always pierce my heart when I think of some of my bosom friends,” he claimed, “men young in years, but men from the ground up, who have made the supreme sacrifice.”57 Their sacrifices at Belleau Wood revealed that Marines’ identity went deeper than their warrior image. Cowing and Cooper summed up the Marines of the 4th Brigade when they wrote,

And these letters, with their optimism, with their cheer and their smiles, show that the Marines who were battling against the Hun were something more than fighters. They were men—men in action and men in thought.58

The level of hope and emotions conveyed in their letters home meant their fighting spirit was restrained enough to hold on to their humanity. They had not given into the barbarism that American propaganda claimed had corrupted Germany’s manhood.

Passing the Test

Sacrificing their own lives, in part, won Marines great acclaim despite official policies regarding press censorship. Army General John J. Pershing’s press policy dictated that no specific information regarding individual units could be reported to the American newspapers. Reporters, however, could label troops as Marines or soldiers if they omitted designations of division, regiment, or battalion. Through that censorship loophole, the American public received joyous news in June 1918 of U.S. Marines defeating the Germans in battle. Floyd Gibbons, a Chicago Tribune correspondent, had much to do with this public relations boon.59 After Marines successfully assaulted Hill 142 in the early morning hours of 6 June, he sent a brief report of it to Paris, which then went on to the United States.60 The front page of the Chicago Tribune that day read, “U.S. Marines Smash Huns: Gain Glory in Brisk Fight on the Marne.”61 That very evening, Gibbons suffered three hits from a German machine gun: two rounds through his left arm and one in the left eye. A few hours later, Gibbons crawled to safety under the cover of darkness.62

While recovering, Gibbons constructed one of the most significant and powerful images of the Great War-era Marine Corps. Unlike Vera Cruz (1914) and the battles that came a generation later in World War II, there were no influential photographs taken of Marines in France. For much of American society, this dearth of iconic imagery from the western front led to a general fading of public remembrance of Belleau Wood and the Great War.63 However, Gibbons’s description of a Marine gunnery sergeant’s words to his men right before they attacked across the machine-gun-swept wheat fields created an indelible image not forgotten by Marines today:

The minute for the Marine advance was approaching. An old gunnery sergeant commanded the platoon in the absence of a lieutenant, who had been shot and was out of the fight. This old sergeant was a Marine veteran. His cheeks were bronzed with the wind and sun of the seven seas. The service bar across his left breast showed that he had fought in the Philippines, in Santo Domingo, at the walls of Pekin, and in the streets of Vera Cruz. I make no apologies for his language. To me his words were classic, if not sacred. As the minute for the advance arrived, he arose from the trees first and jumped out onto the exposed edge of that field that ran with lead, across which he and his men were to charge. Then he turned to give the charge order to the men of his platoon—his mates—the men he loved. He said: “Come on, you sons-o’-bitches! Do you want to live forever?”64

Gunnery Sergeant Dan Daly is thought to be the Marine that Gibbons described.65 By 1918, Daly had been in the Marine Corps for 19 years and won two medals of honor. He was the epitome of what a tough Marine should be.66 Gibbons’s imagery of this scene would help paint the soldiers of the sea as fearless heroes and men from their boots up.

What happened when news of the U.S. Marines’ victory against the Germans reached America was nothing short of a public relations dream for the Corps. “The United States Marines were the toast of New York yesterday,” the New York Times reported. “Everywhere one went in the cars, on the streets, in hotels or skyscrapers, the topic was on the marines, who are fighting with such glorious success in France.”67 Finally, the Marines had proven what many Americans wanted to believe: that American manhood could pass the supreme test of battle. “The battle on the entire front has lifted the Americans into the spotlight and convinced everyone that if needed the Americans have the spirit, dash, and tenacity to fight as well as any living soldiers,” read the Times-Picayune.68 The Marines “have proved that the American can fight, even if he wasn’t brought up to be a soldier,” read another article.69

Marine historians tend to agree that World War I did more for bringing positive attention to the Marine Corps than any other event in the Service’s history up to that point.70 Marine manliness, performed and demonstrated on the battlefields of France, was central to that popularity.71 “What sort of men are they?” asked Reginald W. Kauffman, a journalist for The Living Age. “ ‘The best,’ they will say—and, after living among them, I am not so sure that they are wrong.”72 The Marines at Belleau Wood convinced the Germans that Americans were a superior class of men, according to Floyd Gibbons. “The German has met the American on the battlefield of France and knows that man for man, the American soldier is better,” he boasted.73

French accolades lent further credence to the notion that American manhood had passed the test of battle. The French government renamed Belleau Wood Le Bois de la Brigade de Marine (Woods of the Marine Brigade) in honor of their victory. These were the woods “where the American Marines vanquished the flower of the Kaiser’s army.”74 Their success inspired their allies. “The Americans advanced in a solid phalanx, their strong determined faces and great physique an inspiration to their gallant French comrades,” claimed the Washington Post.75 The famous French painter, Georges Scott, created La Brigade Marine Americaine Au Bois De Belleau to commemorate the American victory there.76 Full of the detritus and drab colors of modern war, La Brigade Marine presents a powerful scene of Marines driving the Germans before them. The Germans, so often depicted as monsters in other images, are reeling in defeat (figure 8).

Figure 8. La Brigade Marine Americaine Au Bois De Belleau, originally published in the United States Collier’s New Encyclopedia, vol. 10 (1921). Georges Scott

Marines: The Pride of American Manhood

For many Marines in France, occupation duty kept them busy along the Rhine until the summer of 1919. Most of them shipped home by August. When they arrived, the war had been over for nine months, and most of the troops had already returned. When the 2d Division reached American shores, the press treated them like heroes.

On 9 August 1919, the 2d Division, comprising both Army infantry and Marines, marched in Washington, DC, in a grand parade. Leading the column was the division commander astride a bay charger, Marine Major General John A. Lejeune. The parade drew huge crowds of people who cheered them on, waved American flags, and pelted the troops with roses. “This beats hand grenades,” a Marine sergeant reportedly said after catching some roses for himself.77 Lejeune greeted the crowds with broad smiles and waves as he led his men down the street and through the throngs of people to where the president, the secretary of the Navy, the Commandant of the Marine Corps, and other high-ranking military officers wait- ed to review the troops.

Near the public library stood the reviewing stand and about 500 wounded veterans of the war. The crowds cheered even louder when they saw Lejeune remove his hat and nod in tribute to them. “Here come the Marines!” many cried as the 4th Brigade began to approach the reviewing stand led by Marine Brigadier General William C. Neville. “West Pointers never marched with more dash or vim than did these men,” a reporter claimed. “Everyone agreed that a finer body of men was never seen in Fifth Avenue than the men commanded by Neville,” the report read. As the column passed the reviewing stand, the wounded Marine veterans standing near the public library “simply went wild.” Major General Commandant Barnett stood next to Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt. Roosevelt turned to Barnett and said, “I never saw a finer looking body of men and I never witnessed a more inspiring parade.” Barnett replied, “No wonder the Germans lost.”78

The Marines became a source of national pride. They did not defeat the Germans on their own, of course. The Army deserved more credit for fighting in the Château-Thierry sector than it received from the press, despite attempts of some Marines and journalists to correct misinformation.79 But many people associated the Marines with Germany’s defeat. The Washington Post published poems that credited the victory solely to the Marines. Isabel Likens Gates wrote a poem about the Marines fighting at Belleau Wood:

Awful and fierce the combat raged. As the Huns came, wave on wave, Against our men, and steel to steel, Mid shot and shell, they’d break and reel And at last before us gave Our loss was great, but it sealed the fate Of the Huns—and the world esteems Like Spartans of old this tale will be told Of Uncle Sam’s marines80

Bessie B. Croffut published a poem for the Marines shortly after their return home. The battles of the summer of 1918 were fresh in her mind as she wrote specifically to praise the returning 4th Brigade. She presented the Marines as heroes:

Invincibles, at Belleau Wood who fought

(“Hellwood,” now Wood of the U.S. Marines!)

Who stayed the Hun and there his lesson taught!

Whatever they call you, “leathernecks,” “gyrenes,”

“Go-Getters,” “devil-dogs,” you were the means

Under a righteous God! You inspiration caught

From Freedom’s fount, to end those godless scenes

And immortality with your best life-blood bought!

You have redeemed your boast, that of your corps—

As of your country—first in fight to be

Where brave men battle for the right and true!

You’ve shown the world what you had shown before

Sailors of air and soldiers of the sea!

“There’s not a thing on earth U.S. Marines can’t do!”81

Conclusion

Because of Belleau Wood, Marines became the pride of their country briefly, the beau ideal of American state governors from around the country to record their thoughts on the Corps, especially their performance in the Great War. Many of their responses were unequivocal. “In the Marine, the bloody Hun met his master,” Frederick D. Gardner of Missouri proclaimed. “The dauntless courage, the intrepidity and the dash of the Marines . . . filled the German soldiery with fear, sent a thrill through the armies of democracy and struck the world with wonder and amazement.”82 If American manhood defeated Germany, then Marines were its best examples. “They, the best red blooded, manhood, and flowery youth took the consequences in whatever fashion as they came,” one civilian author wrote.83 “You see—it was men, wasn’t it, who beat the Germans? Men who became fighters, Marines,” wrote another.84 Governor Hugh M. Dorsey of Georgia claimed that “the splendid achievements of the Marines in the World War are well known, they were the cleanest and strongest of our young manhood.”85 Many Americans looked to the Marine Corps now as an institution comprised of good men. “The Marine Corps stands for all that is good in the ideals of manhood—for strength, for loyalty, for fidelity and for cleanliness in mind and body,” Colorado governor Oliver H. Shoup asserted. “If you are a he-man, if you want action—enlist in the Marines!”86

Marines began immortalizing the Battle of Belleau Wood immediately after the war. “Dear Folks at Home---” and Catlin’s “With the Help of God and a Few Marines” came out in 1919. Charles Scribner’s Sons published Thomas Boyd’s Through the Wheat in 1923 and John W. Thomason’s Fix Bayonets! two years later. Boyd and Thomason both fought at Belleau Wood. One of Thomason’s lasting contributions to the Corps’ remembrance of the battle was his depiction of the men who fought there:

They were the Leathernecks, the Old Timers. They were the old breed of American regular, regarding the service as home and war as an occupation; and they transmit- ted their temper and character and viewpoint [sic] to the high hearted volunteer mass which filled the ranks of the Marine Brigade.87

These Marines were tough, rugged, courageous, and confident. Several years after the battle, a retired Army officer who witnessed the Marines march up the Paris-Metz highway toward the fight remarked to Thomason that “they looked fine, coming in there . . . . Tall fellows, healthy and fit—they looked hard and competent. We watched you going in . . . and we all felt better.”88

Near the fifth anniversary of the Battle of Belleau Wood, one Marine claimed that “recollection of those days of strife stirs all that is best in us; pride in the manhood of America, pride in the achievement of our Corps, pride in possession of our noble traditions.” The pride in themselves needed channeling into determination, “determination to be men, determination to keep bright the reputation won for us.”89 They tried to persuade people that they were elite warriors. But, deeper than that, they convinced themselves and many others that they were men. “The Marine Corps has made a wonderful name for itself,” wrote Arthur J. Burks, a Marine recruiter. He argued that when people described Marines they used descriptions in the following order: “‘cream of American manhood,’ ‘he-men,’ and the like.”90

Historians have stood clear of a gender analysis of the Corps, however. Regarding the Great War era, historians of gender have largely ignored the military, and military historians have largely ignored gender. Marion Sturkey’s Warrior Culture of the U.S. Marines probably speaks for many on the military side when he wrote, “Gender? Who knows? Who Cares? . . . Therefore, with respect to gender this book contains no deranged psycho-babble. . . . Any wacko liberal wimps who dislike this Warrior Culture ethos should find something else to read.”91 He, like many military historians, does not see the value of studying manhood and masculinity in the Marine Corps.

What they all have missed is that Marines often communicated with each other and with the American public using shared ideas of manhood and masculinity. Americans praised the Marines using those notions. Battles like Belleau Wood became proof that Marines were good for the manhood of the country and that they gave American men the opportunity to be courageous, chivalrous, and battle-tested. Americans understood this message, and many believed it. Manhood continued to be important to Marines in the decades following the Great War. In 1930, a writer for Leatherneck claimed that Marines made men into gentlemen. Marines had “evolved from the mere waterfront brawlers of a former day to gentlemen of the first order,” and “it has not sapped their manhood or their ability to fight in the least.”92 During World War II, Captain Edward B. Irving claimed that the Marine Corps had reached the “full stature of its military manhood” and still made “gentlemen who can fight like hell!”93 In 1955, First Lieutenant Walter K. Wilson claimed that a man “should be sent to boot camp with the understanding that he is not only undergoing training and toughening up, but that he is encountering a test of manhood as well and is expected to face up to it.” Once he becomes a Marine, “he should feel that he is accepted as a man and that he is capable of shouldering his responsibilities.”94 The July 1975 issue of Leatherneck published Victor Krulak’s letter to General Randolph M. Pate, where he claimed “that our Corps is downright good for the manhood of our country.”95 In the late 1970s, Marine General Robert H. Barrow wrote,

The opportunity for legitimate proving of one’s manliness is shrinking. A notable exception is the Marine Corps. The Marine Corps’ reputation, richly deserved, for physical toughness, courage and demands on mind and body, attracts those who want to prove their manliness. Here too their search ends.96

Battles like Belleau Wood became prima facie evidence in support of the Marines’ image and appeal throughout the twentieth century.

A study of manhood in the Marine Corps uncovers another rich layer of the institution’s past. It further reveals that the Corps flexed strong cultural muscles that would contribute to its staying power throughout the twentieth century. It also shows that there is still a great deal of work to do to fully understand and appreciate the history of America’s Great War-era Marines and the significance of the battles they fought.

•1775•

Endnotes

- Dr. Mark Folse recently completed his PhD at the University of Alabama. His dissertation, “The Globe and Anchor Men: U.S. Marines, Manhood, and American Culture, 1914–1924,” explores how Marines made manhood central to the communication of their image and culture, a strategy that underpinned the Corps’ efforts to attract recruits and acquire funding from Congress. Folse has published with Marine Corps History magazine and has written Keystone Battle Briefs for the Marine Corps History Division in Quantico, VA. He is the 2015 recipient of Marine Corps Heritage Foundation’s General Lemuel C. Shepherd Jr. Memorial Dissertation Fellowship, and he recently accepted the Class of 1957 Post-Doctoral Fellowship at the U.S. Naval Academy for the 2018–19 academic year. He is also a Marine veteran with combat tours to Afghanistan and Iraq as an infantryman in 2004 and 2005, respectively. The title of this article was inspired by Georgia governor Hugh M. Dorsey’s words about Marines who fought in the Great War, which appeared in the December 1919 issue of the Recruiters’ Bulletin. This quotation reflects the common assertion Marines and their admirers made about men who joined the Corps during the war: that they were the finest examples of American manhood. Hugh M. Dorsey, “Governors Endorse the Marine Corps,” Recruiters’ Bulletin, December 1919, 6.

- Albertus W. Catlin, “With the Help of God and a Few Marines”: The Battles of Chateau Thierry and Belleau Wood (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2013), 306.

- Catlin, “With the Help of God and a Few Marines,” 306.

- BGen Edwin Howard Simmons and Col Joseph H. Alexander, Through the Wheat: The U.S. Marines in World War I (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2008); Robert B. Asprey, At Belleau Wood (Denton: University of North Texas Press, 1996); Alan Axelrod, Miracle at Belleau Wood: The Birth of the Modern U.S. Marine Corps (Guilford, CT: Lyons Press, 2007); Henry Berry, Make the Kaiser Dance: Living Memories of a Forgotten War—The American Experience in World War I (New York: Doubleday, 1978); Ronald J. Brown, A Few Good Men: The Fighting Fifth Marines—A History of the USMC’s Most Decorated Regiment (Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 2001); Dick Camp, The Devil Dogs at Belleau Wood: U.S. Marines in World War I (Minneapolis, MN: Zenith Press, 2008); George B. Clark, Devil Dogs: Fighting Marines of World War I (Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1999); Edward M. Coffman, The War to End All Wars: The American Military Experience in World War I (New York: Oxford University Press, 1968); Mark Ethan Grotelueschen, The AEF Way of War: The American Army and Combat in World War I (New York: Cam- bridge University Press, 2007); Edward G. Lengel, Thunder and Flames: Americans in the Crucible of Combat, 1917–1918 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2015); Allan R. Millett, Semper Fidelis: The History of the United States Marine Corps, 2d ed. (New York: The Free Press, 1991); J. Robert Moskin, The U.S. Marine Corps Story, 3d ed. (Boston: Little, Brown, 1992); Michael S. Neiberg, The Second Battle of the Marne (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008); and William D. Parker, A Concise History of the United States Marine Corps, 1775–1969 (Washington, DC: Historical Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1970).

- Kimberly J. Lamay Licursi, Remembering World War I in America (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2018), xv.

- Willis J. Abbot, Soldiers of the Sea: The Story of the United States Marine Corps (New York: Dodd, Mead and Co., 1918), 297–306; Lt- Col Clyde H. Metcalf, A History of The United States Marine Corps (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1939), 482–90; John H. Craige, What the Citizen Should Know about the Marines (New York: Nor- ton, 1941), 22; LtCol Philip N. Pierce and LtCol Frank O. Hough, USMCR, The Compact History of the United States Marine Corps, 2d ed. (New York: Hawthorn Books, 1964), 182–83; Edwin Howard Simmons, The United States Marines: A History, 3d ed. (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1998), 97–100; and Moskin, The U.S. Marine Corps Story, 112–24.

- Paul Westermeyer, “The Rise of the Early Modern Marine Corps and World War I,” in The Legacy of Belleau Wood: 100 Years of Making Marines and Winning Battles, ed. Paul Westermeyer and Breanne Robertson (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps History Division, 2018), 2.

- Millett, Semper Fidelis, 318; see also Leo J. Daugherty III, “ ‘To Fight Our Country’s Battles’: An Institutional History of the United States Marine Corps During the Interwar Era, 1919–1935” (PhD diss., Ohio State University, 2001), 55.

- Axelrod, Miracle at Belleau Wood, 229.

- Heather Marshall, “ ‘It Means Something These Days to be a Marine’: Image, Identity, and Mission in the Marine Corps, 1861– 1918” (PhD diss., Duke University, 2010), 353.

- “Preface,” in LtGen Victor H. Krulak, First to Fight: An Inside View of the U.S. Marine Corps (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1984), xv.

- Luther H. Gulick, The Dynamic of Manhood (New York: Association Press, 1918), 9–14; Martyn Summerbell, Manhood in Its American Type (Boston: Richard G. Badger, 1916), 109; Kelly Miller, “Education for Manhood,” Kelly Miller’s Monographic Magazine 1, no. 1, April 1913, 12; George Walter Fiske, Boy Life and Self-Government (New York: Association Press, 1916), 28; Rev. Jasper S. Hogan, “Manhood as an Objective in College Training” (address to alumni of Rutgers College, 19 June 1912), 6–8; and R. Swinburne Clymer, The Way to Godhood (Allentown, PA: Philosophical Publishing, 1914), 89–90.

- The opposites of manliness and manhood in the nineteenth century tended to be childishness and childhood. With the rise of female suffrage movements and the perception of women encroaching on the traditional spheres of men, femininity and womanhood became the opposites. See Donald J. Mrozek, “The Habit of Victory: The American Military and the Cult of Manliness,” in Manliness and Morality: Middle-class Masculinity in Britain and America, 1800–1940, ed. J. A. Mangan and James Walvin (Oxford: Manchester University Press, 1987), 221–23; Peter G. Filene, Him/Her/Self: Sex Roles in Modern America, 2d ed. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986), 93; Joe L. Dubbert, “Progressivism and Masculinity in Crisis,” in The American Man, ed. Elizabeth H. Pleck and Joseph H. Pleck (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1980), 308; Michael Messner, “The Meaning of Success: The Athletic Experience and the Development of Male Identity,” in The Making of Masculinities: The New Men’s Studies, ed. Harry Brod (Boston: Allen & Unwin, 1987), 196; and Michael S. Kimmel, “The Contemporary ‘Crisis’ of Masculinity in Historical Perspective,” in The Making of Masculinities, 143.

- Clymer, The Way to Godhood, 77.

- Clymer, The Way to Godhood, 89–90.

- Outline of Plan for Military Training in Public Schools of the United States (Washington, DC: U.S. Army War College, 1915), 8.

- Gail Bederman, Manliness and Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 1880–1917 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), 10–13; Kimmel, “The Contemporary ‘Crisis’ of Masculinity in Historical Perspective,” 143–53; Michael Kimmel, Manhood in America: A Cultural History, 3d ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 62; E. Anthony Rotundo, “Body and Soul: Changing Ideals of American Middle- Class Manhood, 1770–1920,” Journal of Social History 16, no. 4 (July 1983): 23–38, https://doi.org/10.1353/jsh/16.4.23; Kristin L. Hogan- son, Fighting for American Manhood: How Gender Politics Provoked the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998), 9; and Robert H. Zieger, America’s Great War: World War I and the American Experience (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2001), 136.

- Clymer, The Way to Godhood, 77.

- Summerbell, Manhood in Its American Type, 40.

- Peter Gabriel Filene, “In Time of War,” in The American Man, 323.

- Mrozek, “The Habit of Victory,” 221–23; Filene, Him/Her/Self, 93; Dubbert, “Progressivism and Masculinity in Crisis,” 308; Messner, “The Meaning of Success,” 196; and Kimmel, “The Contemporary ‘Crisis’ of Masculinity in Historical Perspective,” 143.

- Martin Summers, Manliness & its Discontents: The Black Middle Class & the Transformation of Masculinity, 1900–1930 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 16; and Athena Delvin, Between Profits and Primitivism: Shaping White Middle-Class Masculinity in the United States, 1880–1917 (New York: Routledge, 2005), 9.

- Delvin, Between Profits and Primitivism, 9.

- For more analysis on the importance of the male body to masculinity, see Delvin, Between Profits and Primitivism, 4; Susan Bordo, The Male Body: A New Look at Men in Public and Private (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1999); Christina S. Jarvis, The Male Body at War: American Masculinity during World War II (Dekalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2004), 4; and John F. Kasson, Houdini, Tarzan, and the Perfect Man: The White Male Body and the Challenge of Modernity in America (New York: Hill and Wang, 2001), 19.

- [Artist’s name illegible], “Honest Pride,” Recruiters’ Bulletin, December 1919, 21.

- Michael C. C. Adams, The Great Adventure: Male Desire and the Coming of World War I (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990), 49.

- Congressional Record Containing the Proceedings and Debates of the First Session of the Sixty-Fifth Congress (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1917), 137.

- C. L. S., “The Red Badge of Courage,” Marines’ Magazine, July 1917, 14.

- C. L. S., “The Red Badge of Courage,” 14.

- Bishop Junior, “Jim Bitter—Coward,” Marines’ Magazine, June 1918, 4–6.

- H. G. Youard, Showing Ourselves Men: Addresses for Men’s Services (New York: E. S. Gorham, 1911), 9.

- “Manhood!,” Manitoba Free Press (Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada), 3 August 1918, 19.

- Sgt Arthur R. M. Ganoe, “War Thunder Rocks the Earth at Villers-Cotterets: Vivid Picture of Greatest Bombardment of History Is Drawn by Marine Who Participated in Soissons Offensive,” Marines’ Bulletin, November 1918, 29.

- C. L. S., “The Red Badge of Courage,” 14.

- “Former Congressman a Marine,” Recruiters’ Bulletin, May 1917, 32. Perhaps the most famous enlistee the Marine Corps gained was former congressman and successful Detroit attorney Edwin Denby. Nearly 50, and weighing more than 250 pounds, Denby was overage and did not meet the Corps’ physical standards. Nevertheless, MajGen George Barnett could not pass up on the opportunity to enlist a prominent American citizen. The Corps sent Pvt Denby down to the newly established recruit training depot at Parris Island, SC. While there, he served as a motivational speaker for new enlistees. When asked by the press why he enlisted, Denby replied, “The country needs men.”

- Catlin, “With the Help of God and a Few Marines,” 292.

- Youard, Showing Ourselves Men, 9. For more on cleanliness and manhood, see Summerbell, Manhood in Its American Type, 99; and John S. P. Tatlock, Why America Fights Germany (Washington, DC: Committee on Public Information, 1918), 11.

- Woodrow Wilson, “Flag Day Address (June 14, 1917),” in Liberty, Peace, and Justice, Riverside Literature Series (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1918), 86. This speech was delivered in Washington, DC, on 14 June 1917.

- Congressional Record Containing the Proceedings and Debates of the First Session of the Sixty-Fifth Congress, 383–84, emphasis added.

- Congressional Record Containing the Proceedings and Debates of the First Session of the Sixty-Fifth Congress, 383–84; Fiske, Boy Life and Self-Government, 17; and Summerbell, Manhood in Its American Type, 112–13.

- Fiske, Boy Life and Self-Government, 17.

- Summerbell, Manhood in Its American Type, 112–13.

- Wilson, “Flag Day Address (June 14, 1917),” 87; Tatlock, Why America Fights Germany, 5; and Ralph Tyler Flewelling, Philosophy and the War (New York: The Abingdon Press, 1918), 35.

- Josephus Daniels, “As They Go Forth to Battle,” in The Navy and the Nation: The War-Time Addresses (New York: George H. Doran Co., 1919), 171.

- Maj Edwin N. McClellan, The United States Marine Corps in the World War (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1920), 115.

- Kemper F. Cowing, comp., and Courtney Ryley Cooper, ed., “Dear Folks at Home---”: The Glorious Story of the United States Marines in France as Told by Their Letters from the Battlefield (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1919), 3. Cowing compiled wartime letters penned by Marines, Morgan Dennis provided illustrations, and Cooper served as the editor.

- Walter Scott Hiller to his family, 16 June 1918, “Dear Folks at Home---,” 118.

- Paul Fussell, The Great War and Modern Memory (New York: Oxford University Press, 1975), 7–18; also see Mary Loeffelholz, ed., “World War I and Its Aftermath,” in The Norton Anthology of American Literature, 1914–1945, vol. D, 7th ed. (New York: Norton, 2007), 1371–72; Jon Stallworthy and Jahan Ramazani, eds., “Voices From World War I,” in The Norton Anthology of English Literature: The Twentieth Century and After, vol. F, 8th ed. (New York: Nor- ton, 2006), 1954–55.

- Merwin H. Silverthorne to his parents, 1 July 1918, “Dear Folks at Home---,” 118, hereafter Silverthorne letter.

- Silverthorne letter, 118.

- Silverthorne letter, 119.

- John F. Pinson to his family [no date given], “Dear Folks at Home---,” 160, hereafter Pinson letter.

- Pinson letter, 160.

- E. A. Wahl to Ann, 27 June 1918, “Dear Folks at Home---,” 143–44.

- George W. Hamilton to his family, 25 June 1918, “Dear Folks at Home ,” 127.

- Henry N. Manney to his mother, 10 June 1918, “Dear Folks at Home---,” 135–36.

- Silverthorne letter, 117–18.

- Cowing and Cooper, “Dear Folks at Home---,” 169.

- Millett, Semper Fidelis, 303; Lengel, Thunder and Flames, 111–12; Simmons, The United States Marines, 99; and Moskin, The U.S. Marine Corps Story, 99–100.

- Floyd Gibbons, “And They Thought We Wouldn’t Fight” (New York: George H. Doran Co., 1918), 298; another version of Gibbons’s report can be found in Abbot, Soldiers of the Sea, 298–300.

- “U.S. Marines Smash Huns: Gain Glory in Brisk Fight on the Marne,” Chicago Daily Tribune, 6 June 1918, 1; and “Associated Press Dispatches Citing Marines in France,” Marine Corps Gazette 3, no. 2 (June 1918): 158–59.

- Gibbons, “And They Thought We Wouldn’t Fight,” 312–22.

- Licursi, Remembering World War I, xv.

- Gibbons, “And They Thought We Wouldn’t Fight,” 304.

- Simmons, The United States Marines, 99.

- “Three Times, But Not Out Yet,” Marines’ Magazine, October 1918, 11–12; “Heroes of Belleau Wood Come Back Smiling,” Recruiters’ Bulletin, September 1918, 49; and Abbot, Soldiers of the Sea, 309–10.

- “Valor of Marines Stirs All America,” New York Times, 9 June 1918, 2.

- Don Martin, “Heroic Marines Whip Back Huns and Hold Gains,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans), 9 June 1918.

- Don Martin, “U.S. Marines Scored One of Biggest Allied Successes in Marne Fighting,” Washington Post, 8 June 1918; and “Marines Carve Lasting Niche in Fame’s Hall Recruits Flock to Ranks of Corps Whose Slogan Is ‘First to Fight’,” Times-Picayune, 24 June 1918, 7. “When the Marines at Château Thierry surprised their foes by the determination of their advance they evidenced the kind of enthusiasm that is characteristic of all Americans and more intensely characteristic of the Marine than any other branch of the American military establishment,” “Marines Carve Lasting Niche.”

- Millett, Semper Fidelis, 317; Moskin, The U.S. Marine Corps Story, 144; and Marshall, “It Means Something These Days to Be a Marine,” 353.

- For how gender can be understood as a performance, see Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York: Routledge, Chapman and Hall, 1990).

- Reginald Wright Kauffman, “The American Marines,” Living Age, July 1918, 45.

- Kemper F. Cowing, “Floyd Gibbons, Devil Dog by Nature,” Marines’ Magazine, October 1918, 15.

- “Bois Brigade De Marines, Name Given Belleau Wood, in Honor of U.S. Forces,” Washington Post, 11 August 1918; “Belleau Wood Given New Name in Honor of U.S. Marine Brigade,” Washington Post, 12 July 1918; McClellan, The United States Marine Corps in the World War, 62–63; and Millett, Semper Fidelis, 303–4.

- “U.S. Marines, Fighting Like Tigers, Hurl Foe Back nearly a Mile,” Washington Post, 7 June 1918.

- “French Artist Depicts U.S. Marines’ Victory,” Courier-Journal (Louisville, KY), 10 October 1918, 2.

- “Devil Dog Division Captures Fifth Ave,” New York Times, 9 August 1919, 9.

- “Devil Dog Division Captures Fifth Ave,” 9. For more descriptions of this parade and ones like it, see “Governor Hugs Hero Marines at Glory Fete,” Chicago Daily Tribune, 24 August 1919, 3; “March of Marines Thrills the Capital: 8,000 Men of the Fourth Brigade Are Reviewed by President, Cabinet, and Diplomats,” New York Times, 13 August 1919; and “More ‘Leathernecks,’ World War Heroes, Back in America,” Chicago Daily Tribune, 7 August 1919.

- Edwin L. James, “Stories of the War that Didn’t Happen: Even the Marines Themselves Admit They Have Received an Oversupply of Credit,” New York Times, 25 May 1919.

- Isabel Likens Gates, “The United States Marines,” Washington Post, 12 August 1919, 6.

- Bessie B. Croffut, “U.S. Marines,” Washington Post, 19 August 1919, 8.

- Frederick D. Gardner, “Governors Endorse the Marine Corps,” Recruiters’ Bulletin, December 1919, 6.

- M. Krakower, “Schoolboy Essays Pay Original Tributes to Men of the Corps,” Marines’ Bulletin, January 1919, 28.

- William Almon Wolff, “Leading Advertising Experts Commend Success of Marines’ Publicity Campaign,” Marines’ Bulletin, Christmas 1918, 6.

- Dorsey, “Governors Endorse the Marine Corps.”

- Shoup, “Governors Endorse the Marine Corps,” 29.

- John W. Thomason, Fix Bayonets! With the U.S. Marine Corps in France, 1917–1918 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1925), x–xi.

- Thomason, Fix Bayonets!, xiii.

- “Belleau Wood,” Leatherneck, 9 June 1923, 8.

- Lt Arthur J. Burks, “Selling the Corps,” Marine Corps Gazette 9, no. 2 (June 1924): 114.

- Marion F. Sturkey, Warrior Culture of the U.S. Marines, 3d ed. (Plumb Branch, SC: Heritage Press, 2010), xii.

- “Yesterday and Today,” Leatherneck, August 1930, 26.

- Edward B. Irving, “How Does the Marine Corps of 1918 Compare with the Marine Corps of 1942?,” Leatherneck, November 1942, 272.

- Military Organization,” Marine Corps Gazette 39, no. 2 (February1stLt Walter K. Wilson III, “Reality: The Basic Premise of Democracy Is Philosophically Incompatible with the Efficiency of a 1955): 37.

- Victor H. Krulak, “Who Needs a Marine Corps?,” Leatherneck, July 1975, 11.

- Moskin, The U.S. Marine Corps Story, 712; and James A. Warren, American Spartans—The U.S. Marines: A Combat History from Iwo Jima to Iraq (New York: Free Press, 2005), 26.