PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

In fall 1940, the world was in the grips of its second global war. As part of America’s efforts to prepare for war, the Organized U.S. Marine Corps Reserve was mobilized for active duty by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in November and December 1940. Despite comprising only 2.5 percent of the Marine Corps’ total strength in World War II, these mobilized Reserve Marines made important contributions to the defense of the nation and the Allied victory in the Pacific. Yet the manner in which these Marines were mobilized and utilized during the war ensured that their achievements and sacrifices would be lost in the overall history of the Corps in World War II.

1940: A Nation Unprepared for War

Throughout the 1930s, totalitarian regimes in Germany, Japan, Italy, and the Soviet Union aggressively expanded throughout Europe, Africa, and Asia. By summer 1940, war raged across the globe. Due to its Great Depression and fierce isolationist sentiments, the United States was woefully unprepared for war. On 30 June 1940, the active duty U.S. Army numbered only 267,767 soldiers with another 300,000 serving in the National Guard and an additional 120,000 soldiers in the Army Reserve. The U.S. Navy numbered only 160,997 sailors and had only six aircraft carriers in commission. The active duty Marine Corps numbered only 28,277. Expecting that the United States would be dragged into the war, President Roosevelt and many other U.S. leaders worked prudently to prepare the nation while not antagonizing the public. Roosevelt’s task was complicated further because he was also seeking an unprecedented third term as president.2

The stunning Nazi German victories in spring 1940 provided major justification for a rapid and immediate American military build-up. The Army Reserve began mobilizing individual members that summer. On 19 July 1940, Congress enacted the Vinson-Walsh Act (a.k.a. the Two-Ocean Navy Act) to expand and prepare the U.S. Navy for World War II. This act included expanding the combat ship strength of the Navy by 70 percent (1.325 million tons). As authorized by Congress, President Roosevelt called the National Guard to federal service in September and October 1940 and enacted the nation’s first peacetime draft. Also in October, the president authorized the mobilization of the entire U.S. Marine Corps Reserve (USMCR). Thus, the mobilization of the USMCR in late 1940 and into 1941 took place within the historical context of a nation hastily trying to prepare itself for a truly global war.3

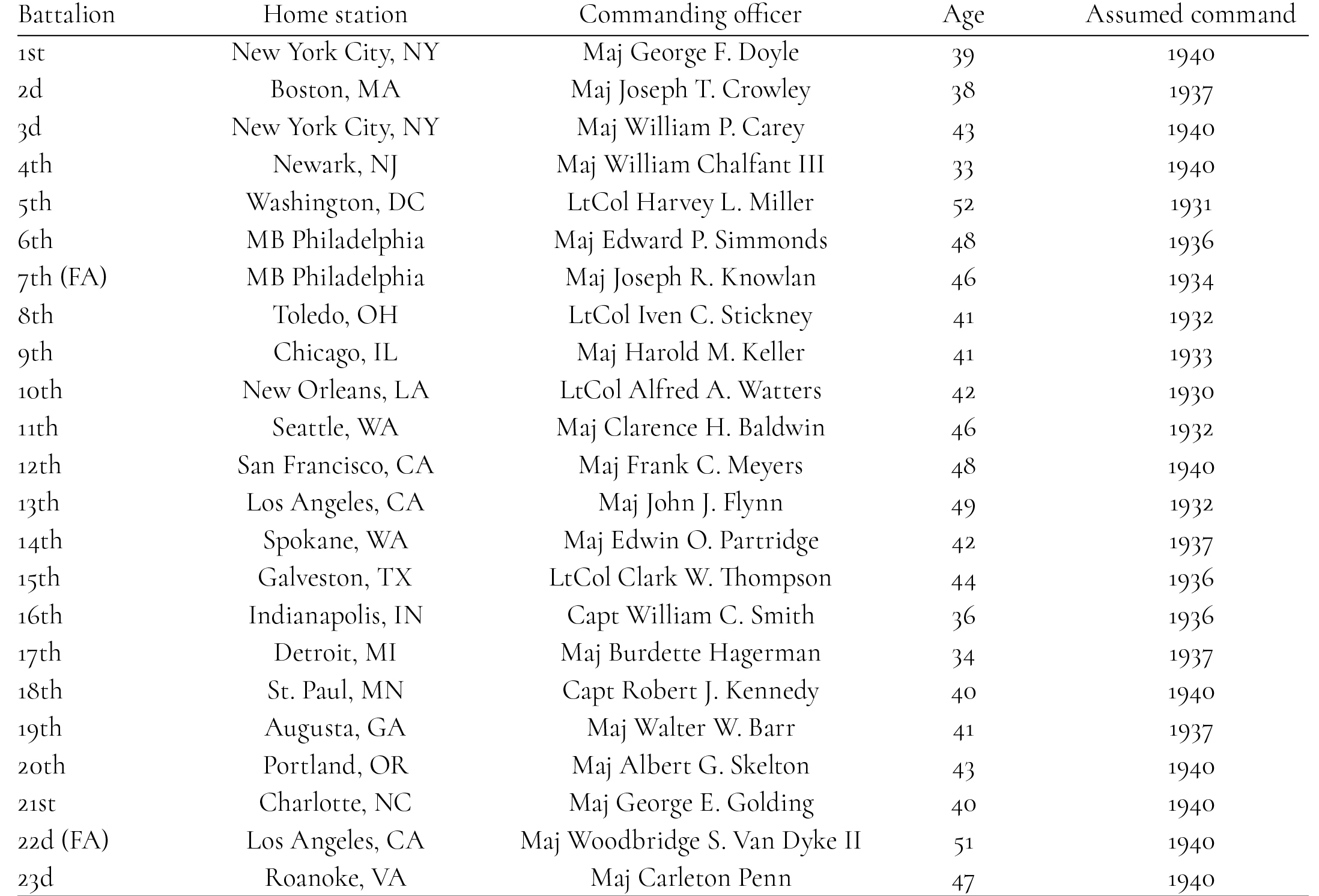

The Marine Coprs Reserve in 1940

The USMCR had been in existence since 1916. Its members were mobilized for World War I and served with distinction alongside their active duty counterparts. Immediately following the war, the USMCR went through several years of downsizing and neglect. In February 1925, the U.S. Congress passed legislation that made sweeping improvements to the Navy Reserve and the USMCR and authorized aviation units for the latter. The following year, Commandant of the Marine Corps Major General John A. Lejeune authorized the formation of several independent rifle companies; within a year, 16 had been organized. The USMCR quickly expanded, so much so that a regiment/battalion system was employed from 1929 to 1935. In 1935, that system was abandoned in favor of independent battalions and squadrons.4 In fall 1940, the USMCR comprised three main components: the Organized Marine Corps Reserve (OMCR), the Fleet Marine Corps Reserve (FMCR), and the Volunteer Marine Corps Reserve (VMCR). The FMCR consisted of nondrilling reservists with at least four years of active duty service, and the VMCR consisted of nondrilling reservists with little or no active duty service. Together, the FMCR and the VMCR constituted the inactive Reserve, which had more than 9,000 members. The OMCR constituted the active Reserve and consisted of a ground component of 23 battalions and an aviation component of 13 aviation squadrons. Members of the OMCR performed weekly training events at their reserve centers and annual field training at military installations across the country. Altogether, the USMCR had 16,477 members at the end of October 1940 (table 1).5

Table 1. Status of the Marine Corps Reserve, October 1940

Source: The Marine Corps Reserve: A History

By fall 1940, the OMCR had grown to 23 battalions and 13 aviation squadrons. The ground component consisted of 21 infantry battalions and two field artillery battalions. Geographically they were located from Boston, Massachusetts, to Spokane, Washington (table 2). Though designated as battalions, these OMCR units in reality were well below the table of organization and equipment strength of a Marine Corps battalion, averaging only 250 Marines and sailors.

The 23 battalion commanders represented a diverse range of age and military experience. Except for four lieutenant colonels and two captains, all of the battalion commanders were majors. Several had served during World War I, including Lieutenant Colonel Clark W. Thompson of the 15th Battalion (Galveston, Texas), Major Joseph R. Knowlan of the 7th Battalion (Field Artillery) (Philadelphia), and Major Edward Simmonds of the 6th Battalion (Philadelphia). The oldest battalion commanders were 52-year-old Lieutenant Colonel Harvey L. Miller of the 5th Battalion (Washington, DC) and 51-year-old Major Woodbridge S. Van Dyke II of the 22d Battalion (Field Artillery) (Los Angeles). The youngest battalion commanders were 33-year-old Major William Chalfant III of the 4th Battalion (Newark, New Jersey), and 34-year-old Major Burdette Hagerman of the 17th Battalion (Detroit). The remaining battalion commanders were ages 36 to 49. Two battalion commanders had been in command for more than nine years, but conversely, 9 of the 23 battalion commanders (39 percent) had assumed command in 1940.6

Table 2. OMCR battalions and commanders, October 1940

Notes: MB = Marine Barracks; and FA = field artillery.

Source: Fegan, “M-Day for the Reserves,” 24–29

There also was much diversity in the battalion commanders’ civilian occupations and experience. Lieutenant Colonel Miller was secretary of the District Boxing Commission. Lieutenant Colonel Thompson had served as a congressman for Texas. Major Knowlan worked in the insurance industry. Major Simmonds was superintendent of the Overbrook School for the Blind and president of the Springfield Township School Board in Pennsylvania. Major Van Dyke was a Hollywood movie director whose credits included Tarzan the Ape Man (1932). He also had been one of California’s delegates to the 1940 Democratic National Convention.7

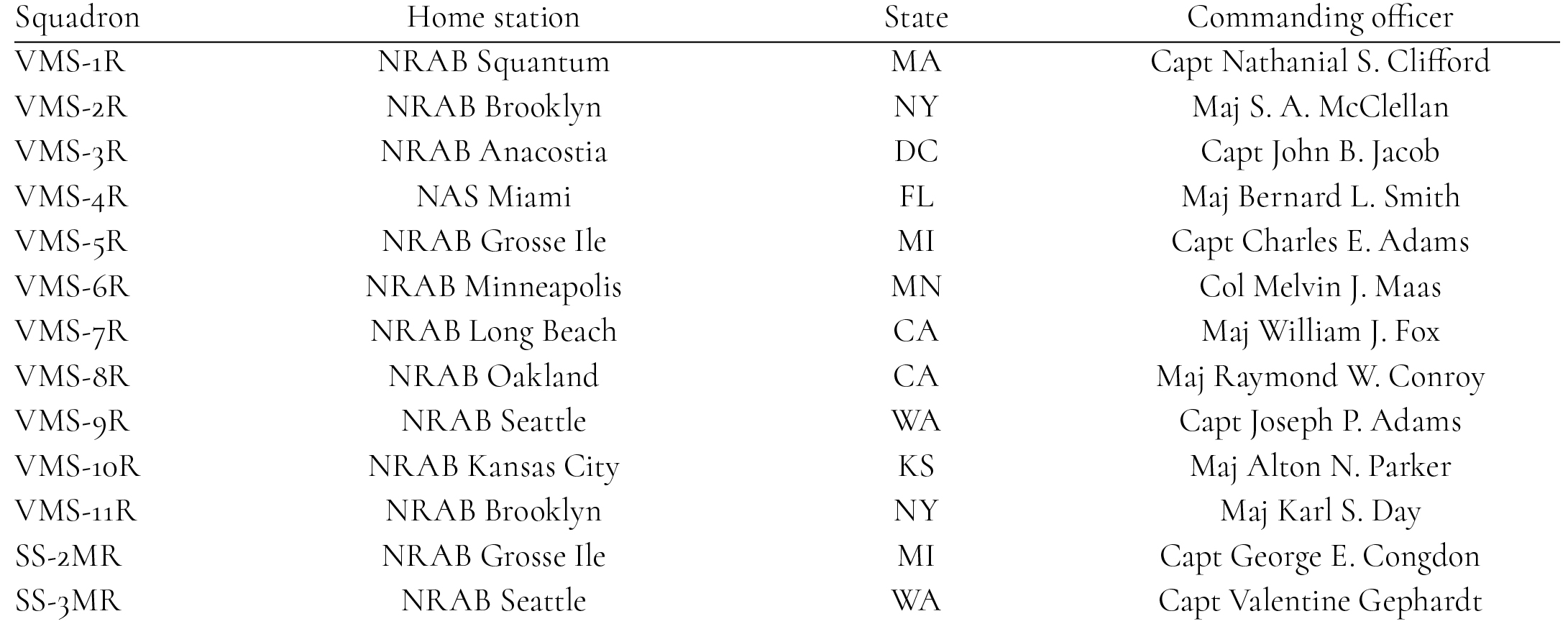

The aviation component comprised 13 aviation squadrons that, like the battalions, were located across the country from New York to California (table 3). Eleven of the squadrons were Marine Reserve Scouting Squadrons; the remaining two were Marine Reserve Service Squadrons. In 1940, these squadrons were almost exclusively equipped with the Vought SB2U Vindicator dive-bomber.

Table 3. Mobilized OMCR aviation squadrons

Notes: SS = Service Squadron; MR = Marine Reserve Service Squadron; VMS = Marine Reserve Scouting Squadron; NRAB = Naval Reserve Aviation Base; and NAS = Naval Air Station.

Source: The Marine Corps Reserve: A History

The commanding officers of these 13 Marine aviation squadrons were among the leaders in aviation in the United States. Major Alton N. Parker of Marine Reserve Scouting Squadron 10 (VMS-10R) had flown in combat during World War I. As a member of Navy Captain Richard E. Byrd’s first Antarctica expedition, Major Parker was the first person to fly over the frozen continent on 29 December 1929. Major William J. Fox commanded VMS-7R; in civilian life, he was chief engineer for the Los Angeles County Regional Planning Commission and stood in for actor Errol Flynn as a stunt pilot in the 1941 movie Dive Bomber. Colonel Melvin J. Maas, commanding officer of VMS-6R, enlisted in the Marine Corps during World War I and learned to fly as an enlisted Marine; he was commissioned in the OMCR in 1925 and also served as a U.S. representative for Minnesota. Major Bernard Lewis Smith of VMS-4R was the second Marine Corps aviator right after Lieutenant Alfred A. Cunningham. During World War I, Smith served as a naval intelligence attaché with the French Armée de l’Air, and studied lighter-than-air craft with them. The commander of VMS-11R, Major Karl S. Day, had earned the Navy Cross while flying bombers during World War I. After the war, he worked for American Airlines and was a pioneer in instrument flight.8

Mobilizing the USMCR

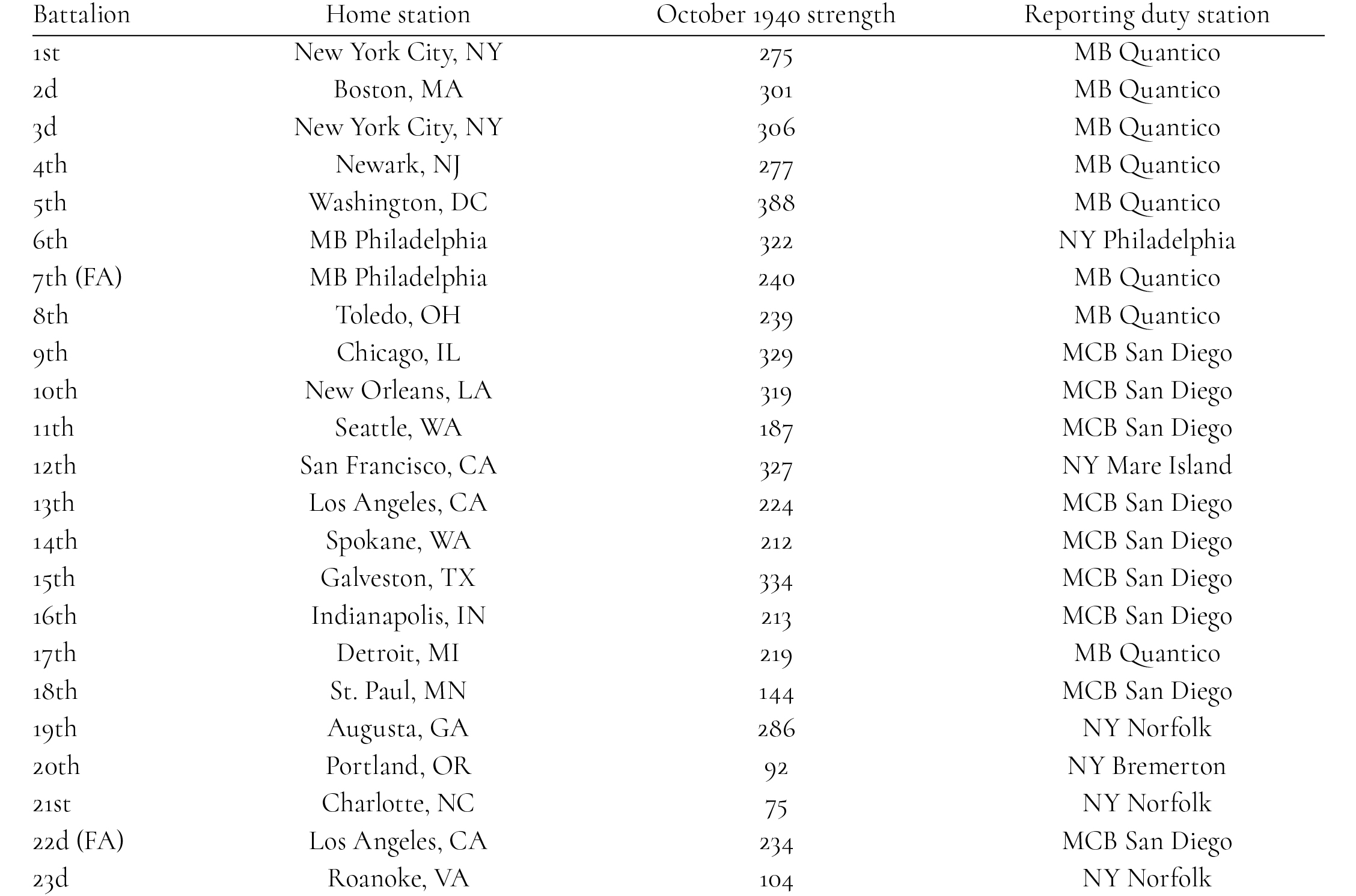

Though mobilization of the USMCR had been dis- cussed during summer 1940, the key decisions for its implementation were made and executed in October. The mobilization of both the Navy Reserves and USMCR was done under President Roosevelt’s Presidential Order No. 8245, which had declared a limited national emergency the previous year. On 5 October 1940, Secretary of the Navy William Franklin Knox issued orders notifying Navy and Marine reservists to be prepared for mobilization on short notice. On 7 October 1940, Commandant Major General Thomas Holcomb sent a Reserve mobilization plan to Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Harold R. Stark for approval. Two days later, the Commandant sent directives to the Marine Corps bases at San Diego, California; Quantico, Virginia; and the Marine Barracks at Navy Yards Philadelphia; Norfolk; Puget Sound/Bremerton; Washington; and Mare Island, California, to prepare to receive members of the OMCR battalions in early November. Table 4 shows the reported strength of each battalion in October 1940 and their planned initial duty stations. The next day, the Navy Department announced that the OMCR battalions would be mobilized on or about 7 November 1940. On 15 October 1940, Assistant Commandant of the Marine Corps Brigadier General Alexander A. Vandegrift issued the orders to mobilize all 23 Reserve battalions. Exactly one month later, Vandegrift ordered the aviation units and 1,000 members of the FMCR mobilized as well.9 One particular paragraph of Commandant Holcomb’s directive to the commanding general of the Fleet Marine Force would have a tremendous impact on the mobilized reservists. Commandant Holcomb wrote, “It is desired that, after a period necessary for completing administrative matters, the personnel of Reserve Battalions be absorbed in units of the Fleet Marine Force so that all units of the Fleet Marine Force will have a proportionate part of regular and reserve personnel.” While Holcomb’s directive would ensure a full integration of active duty and Reserve Marines as the Fleet Marine Force expanded to meet expected wartime contingencies, the Commandant also ensured that the OMCR and the inactive components of the USMCR would cease to function for the foreseeable future.10

Table 4. OMCR battalions, October 1940

Notes: MB = Marine Barracks; MCB = Marine Corps Base; and NY = Naval Yard.

Sources: CMC memo to CO MB Quantico, 9 October 1940; CMC memo to CO MB NY Philadelphia, 9 October 1940; CMC memo to CG FMF MCB San Diego, 9 October 1940; CMC memo to CO MB NY Mare Island, 9 October 1940; CMC memo to CO MB NY Norfolk, 9 October 1940; and CMC memo to CO MB NY Bremerton, 9 October 1940, all: Correspondence Files, Commandant of U.S. Marine Corps

President Roosevelt would frequently use his fireside chats to announce such issues as the limited national emergency or the mobilization of Reserve forces. National Archives and Records Administration, 6728517

The mobilization paradigm for the USMCR in 1940 was very much different than it is today. Today, USMCR units mobilize as units or provide detachments or individuals to augment other active and Reserve units. When the whole unit mobilizes, rear parties continue to function at the home training centers (HTCs). This was not the case in 1940. The purpose of the USMCR of 1940 was to provide trained Marines to augment the active duty forces. Once its members were mobilized, OMCR units were deactivated and remained in a dormant state throughout the war. OMCR units were neither intended to mobilize and deploy as units nor did the units maintain rear parties at the Reserve centers to continue operating while their Marines were mobilized. Furthermore, OMCR reservists were mobilized for the duration of the national emergency.

Within days of Roosevelt’s reelection, OMCR battalions began reporting to their HTCs for mobilization. Nearly all of them then travelled on to their initial duty stations at major Marine Corps and Navy installations on the East and West Coasts. Indianapolis’s 16th Battalion and several other battalions had to travel halfway across the country to reach their duty stations in San Diego. Other battalions had relatively short distances to travel to their duty stations. This included the 5th Battalion of Washington, DC, which reported to Quantico, and the 23d Battalion of Roanoke, Virginia, which reported to Navy Yard Norfolk. The 6th Battalion, based at the Marine Barracks, Philadelphia Navy Yard, merely had to report to its HTC as its initial duty station was the Philadelphia Navy Yard.11

By 9 November 1940, all of the Reserve infantry and field artillery battalions had been mobilized. The cost of mobilizing these 23 battalions was $177,764 with an average cost per battalion of $7,729 and average cost per reservist of $31. Altogether, 239 officers and 6,192 enlisted men were mobilized from the ground forces. Seven officers and 1,183 enlisted Marines were disqualified for physical or hardship reasons or for holding vital jobs in the national defense industries. Remarkably, only 22 enlisted Marines that did not fall into one of the aforementioned categories failed to report for duty.12

Seventeen of the mobilized battalions reported to the Marine Corps bases in either San Diego or Quantico. In San Diego, nine OMCR battalions were deactivated and their Marines were assigned to active duty units in the 2d Marine Brigade. After a period of training, most of these Marines were integrated into existing active duty units or helped form new ones. In the case of the latter, a cadre of active duty Marines was combined with mobilized reservists and new recruits to activate the new unit. The eight OMCR battalions that reported to Quantico were sent to Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, in January 1941. In Cuba, the battalions were deactivated and their members became part of the 1st Marine Brigade. By the end of January 1941, nearly all of the mobilized Reserve battalions had been deactivated and their members absorbed into active duty units.13

The experiences of three mobilized OMCR battalions are illustrative of how OMCR reservists were integrated into the active duty forces. After arriving at San Diego, most of the Marines of 14th Infantry Battalion (Spokane, Washington) were reassigned to 1st Battalion, 8th Marines. The battalion’s former commanding officer, Major Edwin D. Partridge, became the 1st Battalion, 8th Marines’ operations (S-3) officer. The 7th Reserve Battalion (Field Artillery) from Philadelphia reported to Quantico with its 75mm pack howitzers. Two months later, the battalion was deactivated and most of its members became the nucleus of the newly activated 3d Battalion, 11th Marines, at Guantánamo Bay. Major Joseph Knowlan, the former commander of the 7th Reserve Battalion, became commander of the new 3d Battalion, 11th Marines. Not long after, Knowlan and many of his Marines were transferred to 1st Battalion, 11th Marines, with Knowlan assuming command of this battalion. The 6th Infantry Battalion of Marine Barracks Philadelphia remained intact far longer than nearly all of the other mobilized OMCR battalions. The 6th Battalion mobilized at the Philadelphia Navy Yard on 7 November. For reasons that are unclear, the 6th Battalion remained at the Navy Yard for the next six months, performing security, training for war, and working in various departments there. Meanwhile its members, including its commander, Major Edward Simmonds, were steadily being transferred to other units. On 1 April 1941, the battalion was downgraded to the 6th Reserve Company. A month later, all remaining personnel were reassigned and the unit was deactivated—one of the last, if not the last—Reserve units to do so.14

Between December 1940 and May 1941, the remainder of the USMCR was mobilized. On 16 December, the 13 Marine Reserve aviation squadrons with their 92 officers and 670 enlisted men were mobilized. The four West Coast squadrons, VMS-6R from Minneapolis, and VMS-10R from Kansas City all went to San Diego for their initial duty station; the other seven OMCRs went to Quantico. Like their ground component counterparts, the OMCR aviation units were deactivated and their members reassigned to active duty units. After completing the mobilization of its ground and aviation units in mid-1941, the OMCR became inactive and the director of the USMCR, Colonel Joseph C. Fegan, was reassigned to other duties. Also in December 1940, 1,000 members of the FMCR were mobilized. The VMCR underwent two phases of mobilization. The first group of VMCR Marine reservists was mobilized on 14 December 1940. Six months later on 12 May 1941, the second group was mobilized. By the end of May 1941, all available Marine reservists—OMCR, FMCR, and VMCR—had been mobilized, placing a total of 15,927 reservists on active duty.15

The mobilization of the OMCR was an important part of the Marine Corps’ overall expansion to meet the increasing challenges of a world at war. The influx of the ground component Marines helped the Marine Corps to expand its two existing brigades and ultimately upgrade them to divisions. Accordingly, the 1st Marine Division was activated at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, from the 1st Marine Brigade and the 2d Marine Division was activated at Marine Corps Base San Diego from the 2d Marine Brigade. Mobilization of the OMCR squadrons also aided in the activation of the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing and 2d Marine Aircraft Wing in July 1941.16

First Overseas Duty: Iceland

Despite overwhelming odds, Great Britain had staved off defeat by the Third Reich in 1940. The following year, the situation was still dismal, particularly in North Africa, where British forces suffered a series of major defeats. At British prime minister Winston Churchill’s request, President Roosevelt ordered U.S. forces to Iceland to protect the strategically vital North Atlantic island and free up British forces for employment elsewhere. The 1st Marine Brigade (Provisional) was formed from units of the 2d Marine Division with Brigadier General John Marston in command.17 The Marines were chosen for the Iceland mission because they were not prohibited from overseas service, unlike the mobilized National Guard members and recent Army draftees.18

In July 1941, the 1st Marine Brigade (Provisional) relieved British forces on Iceland and took over defense of the island. The brigade included Lieutenant Colonel Oliver P. Smith (future commanding general of the 1st Marine Division in the Korean War), Major David M. Shoup (future Commandant of the Marine Corps), and many mobilized Marine reservists. Captain Robert J. Kennedy (formerly of the 18th Battalion [St. Paul, Minnesota]) served as battalion S-3 (operations) for 3d Battalion, 6th Marines. Captain Harry A. Traffert Jr. (formerly of the 14th Battalion) served as battalion S-4 (logistics) for 2d Battalion, 10th Marines. Mobilized reservist Major Joseph F. Hankins served as executive officer of 2d Battalion, 6th Marines. The former commander of the 11th Battalion (Seattle), Major Clarence H. Baldwin, served as executive officer and battalion operations officer (S-3) for 1st Battalion, 6th Marines. The 1st Marine Brigade served in Iceland until being relieved by units of the U.S. Army in March 1942.19

Wartime Utilization of OMCR Marines

Initially, the Marine Corps made some efforts to keep the mobilized OMCR Marines together with others from their Reserve units, even if their Reserve units had been deactivated after mobilization. Most of the mobilized reservists were from infantry units, so initially they were assigned to infantry units. However, the manpower needs of the rapidly expanding Marine Corps ultimately determined how and where these mobilized reservists served. This became of even greater importance once the United States entered World War II in December 1941. Thus, the wartime experiences of mobilized reservists were often in military occupational specialties much different from their Reserve experiences. This was especially true among the mobilized Reserve officers.

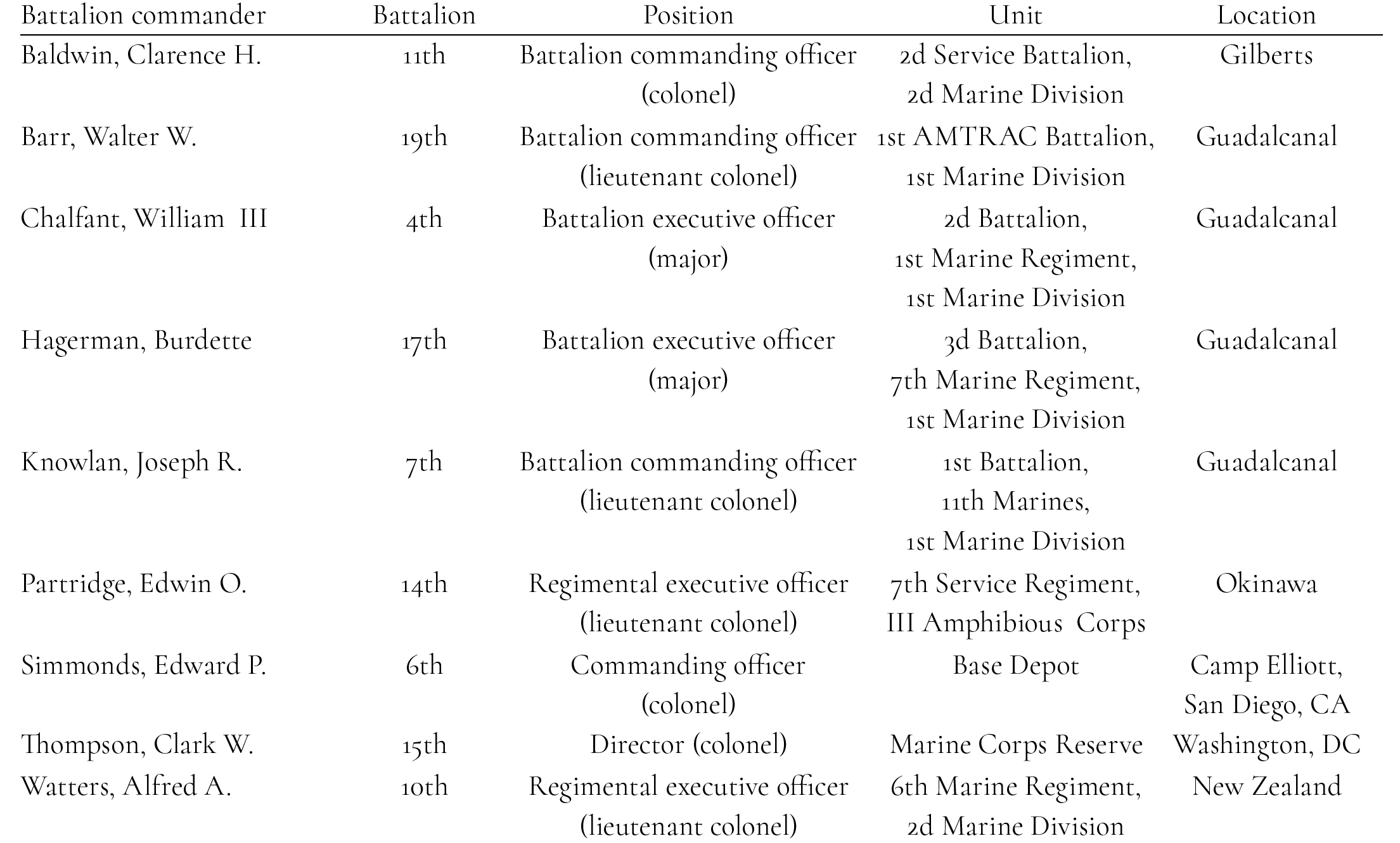

When the ground component of the OMCR was mobilized in November 1940, there were 23 battalion commanders then serving. Since every mobilized Reserve battalion was ultimately deactivated, every one of these officers was reassigned to other command and staff positions throughout the Marine Corps. Major Edward Simmonds served in a succession of stateside logistics assignments. Promoted to colonel, he served as commanding officer, Base Depot, and depot quartermaster at Camp Elliott, San Diego from January 1944 to August 1946. Major Joseph R.Knowlan commanded 1st Battalion, 11th Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division’s field artillery battalion during the Guadalcanal campaign. Medically evacuated in October 1942, Knowlan served as commanding officer, Marine Barracks, Naval Air Training Base Corpus Christi, Texas, from February 1943 to April 1945 and was discharged from active duty at the rank of colonel. Lieutenant Colonel Clark W. Thompson commanded Special Troops, 2d Marine Brigade, and 1st Battalion, 22d Marines, in Samoa in 1942–43. He then returned to the United States and became director of the USMCR. As director, now-Colonel Thompson oversaw planning for the reconstitution of the USMCR that would occur after the war. Table 5 illustrates some of the notable wartime assignments of the mobilized OMCR battalion commanders.20

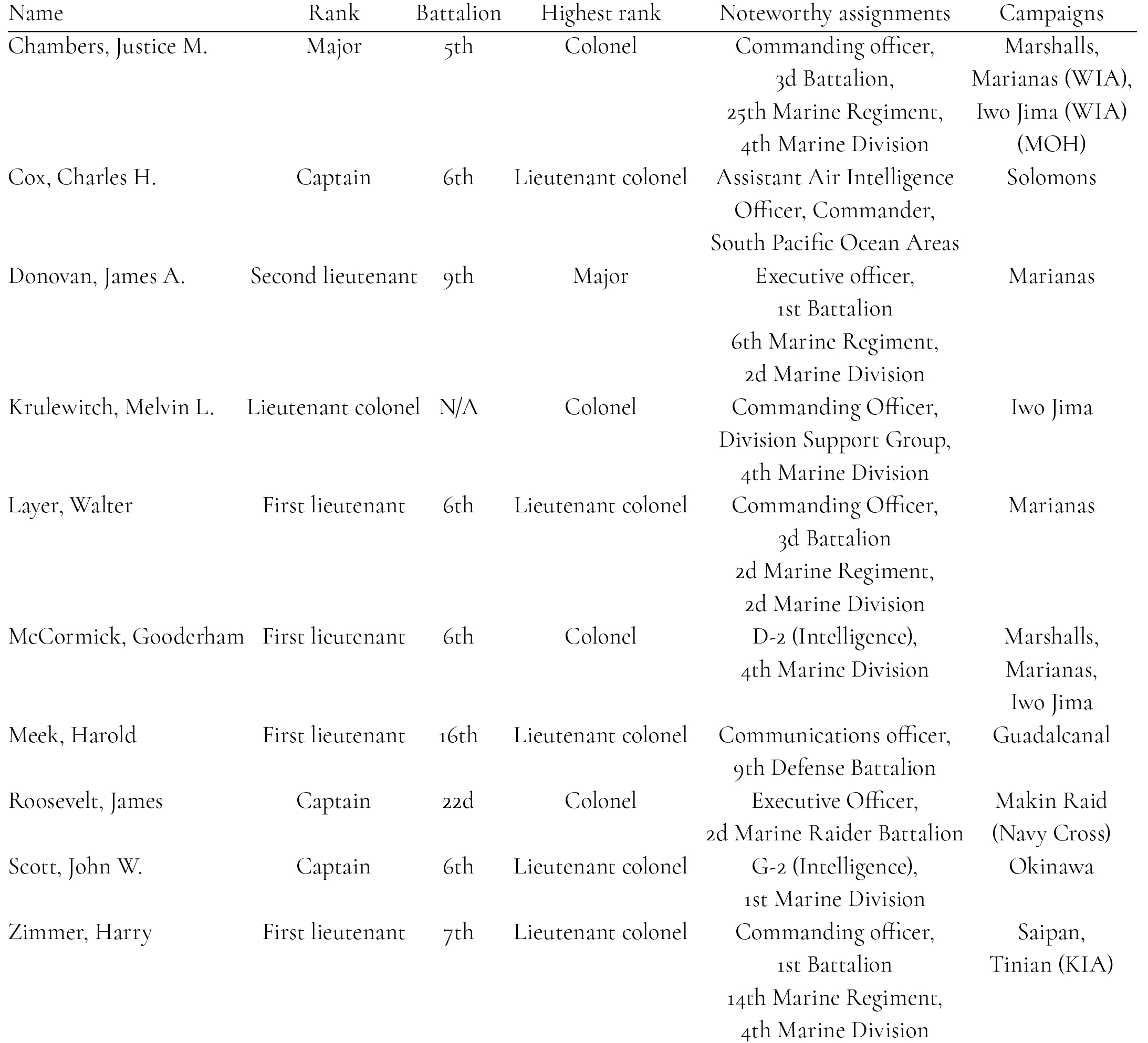

Table 5. Notable assignments of mobilized OMCR battalion commanders

Sources: Henry I. Shaw Jr., Bernard C. Nalty, and Edwin T. Turnbladh, Central Pacific Drive, History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II, vol. 3 (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps 1966), appendix G; Maj John L. Zimmerman, USMCR, The Guadalcanal Campaign (Washington, DC: Historical Section, Division of Public Information, Headquarters, Marine Corps, 1949), appendix E; Knowlan Biography; Maj Chas. S. Nichols Jr. and Henry I. Shaw Jr., Okinawa: Victory in the Pacific (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1955), appendix III; Simmonds personnel file; and “In Memoriam: Col Clark W. Thompson”

The mobilized OMCR squadron commanders also had varied wartime experiences. Major Bernard L. Smith helped organize the Marine Corps’ Barrage Balloon Training School and its Barrage Balloon Squadrons. Major Karl S. Day was instrumental in organizing the Navy/Marine Corps’ instrument flight school in Atlanta, Georgia. During 1943, he organized and commanded Operational Training Squadron 8 at Marine Corps Air Station (MCAS) Cherry Point, North Carolina, which trained pilots to fly the North American PBJ-1 twin-engine bomber—the Navy/ Marine Corps version of the North American B-25 Mitchell. In 1944–45, he was the base commander of Marine Air Base Peleliu Island. Major William J. Fox supervised the reconstruction of Henderson Field on Guadalcanal and commanded Marine Air Base Guadalcanal until being wounded during a Japanese air raid on 31 January 1943. He also oversaw the construction of five airfields in southern California, including MCAS El Toro, which he also commanded. Colonel Melvin J. Maas flew combat missions in the south Pacific and earned the Silver Star while flying as an observer/aerial gunner with the U.S. Army Air Force in September 1942. In May 1945, he assumed command of the Awase Airbase on Okinawa. The following month, he suffered serious shrapnel wounds to his face; due to damage to his optic nerve, he became blind after the war.21

As stated earlier, the Marine Corps initially made some efforts to keep mobilized members of OMCR battalions together. It is difficult to determine how long OMCR reservists stayed together after their battalions were deactivated and they were reassigned to newly forming active duty units. Some members of one mobilized OMCR battalion (Philadelphia’s 7th Battalion) remained together through the Guadalcanal campaign (August–December 1942) as part of the 1st Battalion, 11th Marines. This included Lieutenant Colonel Knowlan, who served as commander of 1st Battalion, 11th Marines, and Captain Harry Zimmer, who served first as a battery commander and later as battalion executive officer. The commander of the 11th Marines, Colonel Pedro A. del Valle, later reported, “I noted an artillery battalion on Guadalcanal, largely Reserves from Philadelphia, who did a superb job—outstanding.”22

Prior to mobilization, most OMCR officers served with either infantry or field artillery battalions. After mobilization, many OMCR officers remained with these branches. Major Justice Marion Chambers of the 5th Infantry Battalion served with the 1st Marine Raider Battalion during the Tulagi invasion in August 1942 and commanded the 3d Battalion, 25th Marine Regiment, 4th Marine Division, during the Marshall Islands, Marianas Islands, and Iwo Jima invasions. He was wounded on Tulagi, Saipan, and Iwo Jima. For his heroic leadership on Iwo Jima, he was awarded the Medal of Honor. Captain Zimmer, of Philadelphia’s 7th Reserve Battalion (Field Artillery), served in 1st Battalion, 11th Marines, 1st Marine Division, on Guadalcanal and commanded another field artillery battalion (1st Battalion, 14th Marines, 4th Marine Division) during the Marshall Islands and Marianas invasions. On 25 July 1944, he and several of his battalion staff were killed by a Japanese artillery shell on Tinian Island. Table 6 offers several more examples of the wartime service of mobilized OMCR ground component officers.23 Due to the manpower needs of the wartime Marine Corps, however, many other mobilized Reserve officers often found themselves in very different career fields. President Roosevelt’s son, James, mobilized with the 22d Battalion (Field Artillery) from Los Angeles. Yet he is best remembered for his role as executive officer of the 2d Marine Raider Battalion and for earning the Navy Cross during the battalion’s August 1942 raid on Makin Island. First Lieutenant Gooderham L. McCormick and Captain Charles H. Cox of the 6th Battalion (Philadelphia) both attended the British Royal Air Force photographic interpretation school in 1941 and learned how to use aerial photography for intelligence purposes. Returning to the United States in November, they helped Navy Lieutenant Commander Robert S. Quackenbush Jr. establish the U.S. Navy School of Photographic Interpretation at Naval Air Station Anacostia, Washington, DC. Afterward, Cox served as assistant air intelligence officer on the staff of the commander, South Pacific Area, Vice Admiral William F. Halsey. McCormick served as the division intelligence (D-2) officer for the 4th Marine Division for the Marshalls, Marianas, and Iwo Jima invasions.24

Table 6. OMCR officers’ noteworthy assignments

Notes: WIA = wounded in action; KIA = killed in action; MOH = Medal of Honor.

Sources: Chambers biography; Cox personnel file; Donovan, Outpost in the North Atlantic, back cover. Donovan later fought in the Korean War with the 1st Marine Division and retired in November 1963 as a colonel; MajGen Melvin L. Krulewitch, USMCR, Now That You Mention It (New York: Quadrangle, 1973); LtCol Whitman S. Bartley, Iwo Jima: Amphibious Epic (Washington, DC: Historical Section, Division of Public Information, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1954), 175; Military personnel file of Col Walter F. Layer, USMCR (Dec.), NPRC-NARA (Layer commanded the 6th Infantry Battalion when it was mobilized for the Korean War and later commanded the 1st Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division, in Korea in the summer of 1952); McCormick personnel file; Military personnel file of Col Harold B. Meek, USMCR (Dec.), NPRC-NARA; Roosevelt biography; “John W. Scott Leads Marines,” Alumni News (University of Maryland), June 1944. Scott ended the war as a lieutenant colonel; Parry, Three War Marine, 43, 46; Brown, A Brief History of the 14th Marines, 42; and Harwood, A Close Encounter, 19

Mobilized Marine aviators tended to stay within aviation for the war. While flying Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters with Marine Fighter Squadron 121 (VMF-121) during the Guadalcanal Campaign, Captain Joseph J. Foss shot down 26 Japanese aircraft. That achievement made him the second leading Marine Corps ace of the war and earned him the Medal of Honor. Major Joseph Sailer Jr., formerly of VMS- 2R at Naval Reserve Aviation Base (NRAB) Brooklyn, commanded Marine Scout Bombing Squadron 132 (VMSB-132) and flew 25 combat missions during the Guadalcanal campaign. While piloting Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers, he scored hits on the Japanese battleship Hiei, two cruisers, a destroyer, and several vtransports. He was lost in action on 7 December 1942 and posthumously awarded the Navy Cross. The former commander of VMS-1R, NRAB Squantum, Massachusetts, Lieutenant Colonel Nathaniel S. Clifford, served in the Solomon Islands with Marine Aircraft Group 21 and was lost in action on 3 August 1943.25

Mobilized enlisted members of the OMCR also served throughout the war in a variety of assignments. The mobilized members of the 16th Battalion are illustrative of this. Private Floyd Henry Davis and Corporal Albert Powhattan Rickert were part of the 1st Defense Battalion that gallantly defended Wake Island against overwhelming Japanese forces. Captured when the garrison was forced to surrender, Rickert and Davis survived several years of horrific treatment by the Japanese until being liberated at the war’s end. Private First Class James E. Hightshue of Company B served with the 2d Marine Division on Guadalcanal, Tarawa, and Okinawa. Brothers Nelson C. and Frederick A. Roetter served in the 16th Battalion together and were both mobilized in 1940. Staff Sergeant Nelson C. Roetter fought on Tulagi and Guadalcanal during the Solomon Islands campaign. Second Lieutenant Frederick A. Roetter earned an officer’s commission and served with 2d Tank Battalion, 2d Marine Division, in New Zealand, where he died from a noncombat accident. Field Cook Paul C. Phillips served with the Marine Detachment aboard the battleship USS Colorado (BB 45). Sergeant Harry H. Walter was wounded while serving with 1st Battalion, 28th Marine Regiment, 5th Marine Division, on Iwo Jima. Sergeant Robert W. Edwards was wounded while serving with a field artillery battalion (3d Battalion, 10th Marine Regiment, 2d Marine Division) on Saipan. Corporal John A. Kraig was killed while serving with Anti-Aircraft Group, 3d Defense Battalion, in the Solomon Islands.26 One can get a sense of where and how mobilized OMCR members served during the war through casualty records. With mobilized members of the OMCR serving in nearly every battle and campaign in the Pacific theater, it was inevitable that some would become casualties. While it is difficult to quantify exactly how many mobilized reservists became casualties, one can get a sense of the casualties suffered by comparing mobilization rosters with Marine Corps casualty cards and casualty lists prepared by the Department of the Navy.

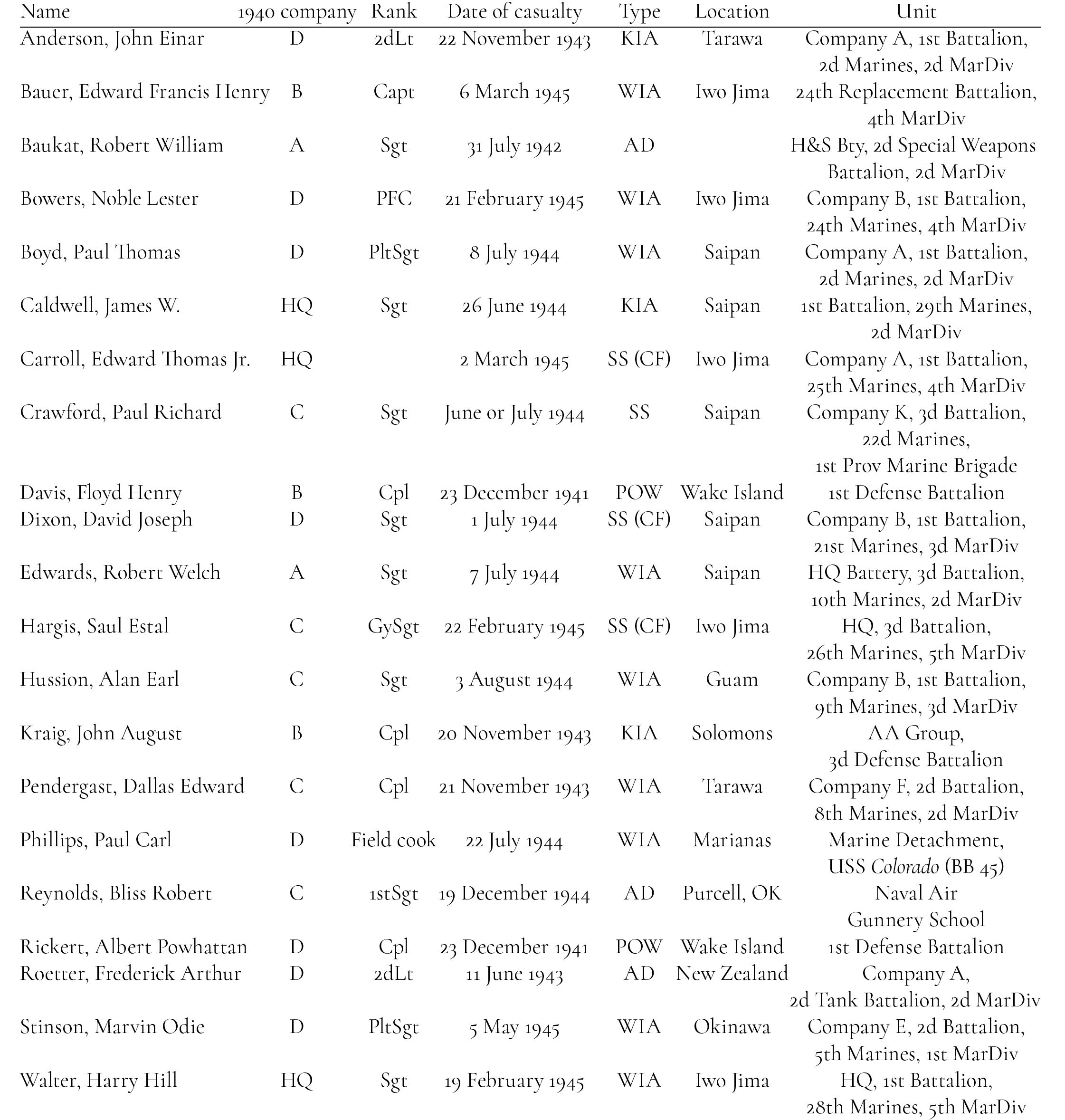

The experiences of the 16th Battalion from Indianapolis illustrate the sacrifices suffered by mobilized OMCR reservists during World War II. The battalion’s mobilized members suffered casualties in battles across the Pacific theater beginning with the defense of Wake Island and ending with the capture of Okinawa some three and a half years later. As previously mentioned, two of its former members—Floyd Davis and Albert Rickert—became prisoners of war when Wake Island was captured by the Japanese in December 1941. Three former 16th Battalion members were killed in action and three others died as a result of noncombat accidents. Four former members were evacuated as a result of what was termed at the time shell shock or combat fatigue. A total of 18 former members suffered casualties in combat. Table 7 summarizes casualties suffered by former 16th Infantry Battalion members during World War II.27

The rapid expansion of the Marine Corps due to wartime requirements opened up opportunities for enlisted Marines to earn officer commissions. This included mobilized OMCR enlisted members. Three members of the 6th Battalion (Philadelphia) all earned officer commissions, each by a different route. Edward B. Meyer was appointed to the U.S. Naval Academy in 1943 and earned a commission as a second lieutenant in 1946. Norman J. E. Murken earned an officer commission through Officer Candidate School and then served as intelligence (S-2) officer for the 4th Pioneer Battalion, 4th Marine Division, during the Iwo Jima invasion. Anthony D. Davitt earned a Bronze Star and was meritoriously commissioned as a second lieutenant for his exemplary performance while supervising radio communications for Headquarters Company, 2d Battalion, 20th Marine Regiment (Engineers), 4th Marine Division, during the Marianas invasion.28

Table 7. 16th Infantry Battalion casualty list, World War II

Notes: SS (CF) = shell shock (combat fatigue); KIA = killed in action; WIA = wounded in action; AD = Accidental Death; POW = prisoner of war.

Sources: To prepare this table, the 16th Battalion’s mobilization roster was cross-referenced with Marine Corps History Division’s Casualty Cards online database, the American Battle Monuments Commission Burials and Memorials online database, and the Department of the Navy’s State Summary of War. Casualties from World War II for Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard Personnel from Indiana, 1946. This was done to ensure accuracy in identifying those battalion members who became casualties during World War II. See footnote 27 for detailed source citation

Mobilization and Utilization Considered

The OMCR was designed to rapidly bring trained Marine reservists into active duty during a time of national emergency. In November and December of 1940, the OMCR performed exactly as it was intended. In doing so, the OMCR helped the Marine Corps to activate the 1st and 2d Marine Divisions and the 1st and 2d Marine Aircraft Wings in 1941. As demonstrated above, these mobilized OMCR members served with distinction throughout the Pacific campaigns and in important stateside assignments.

Even before mobilization, the senior leadership of the Marine Corps had decided that the mobilized battalions and squadrons would be deactivated and their members absorbed into the expanding active duty Marine Corps. The mobilized OMCR Marines were then combined with active duty Marines and new recruits to bring active duty units up to strength or to activate new ones. With every OMCR battalion and squadron well below table of organization and equipment strength, it is hard to argue against this practice. The Marine Corps could have brought the OMCR units up to strength, but it appears that this would have been administratively more difficult.

There were significant downsides to this approach of deactivating the OMCR units and absorbing their Marines into the active duty Corps. “The Reserve Battalions lost their identities when they merged with the brigade units,” Major Edward Partridge, commander of the 14th Battalion, recalled years later. “Individuals, also, quickly lost their identities as Reserves, becoming indistinguishable from the career Marines with whom they trained side by side,” he continued. With the OMCR units now deactivated and all of their members on active duty, the USMCR went dormant for the duration of the war. Unlike today, there were no rear detachments continuing to operate when the unit was mobilized. This meant that the entire USMCR had to be rebuilt when the war was over. Finally, the achievements and sacrifices of the OMCR members have largely been overlooked by history because of the manner in which they served.29

Historiography

The contributions of the OMCR before and during World War II have largely been overlooked by historians of the titanic global struggle. For example, the Navy’s official 15-volume History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, written by preeminent historian Samuel Eliot Morison, does not mention the mobilization of either the USMCR or the Navy Reserve. David J. Ulbrich’s Preparing for Victory: Thomas Holcomb and the Making of the Modern Marine Corps, 1936–1943 is a comprehensive analysis of Holcomb’s tenure as Commandant of the Marine Corps, but it contains only a few brief mentions of the USMCR. While a very comprehensive account, Robert Sherrod’s History of Marine Corps Aviation in World War II contains details of several prominent reservists but no mention about the mobilization of the Marine Reserve squadrons at all. Harry I. Shaw Jr.’s Opening Moves: Marines Gear Up for War was written as part of the Marines in World War II Commemorative Series. Shaw’s work describes the Marine Corps’ efforts to prepare for World War II but only briefly mentions the mobilization of the USMCR. Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, volume one of History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II, contains two sentences acknowledging that the mobilization of the OMCR was an important factor in the Marine Corps’ expansion in 1940–41 and in the formation of two Marine divisions in February 1941.30

Two works in particular do devote significant attention to the mobilization of the USMCR for World War II. Of the official Marine Corps publications, Marine Corps Ground Training in World War II contains the most information about the Reserve mobilization. The Marine Corps Reserve: A History was written and published by the reserve officers of Public Affairs Unit 4-1 in 1966. The book’s third chapter is devoted to World War II, and at 41 pages long, it was the longest chapter in the book.31

Several publications state that approximately 70 percent of the nearly 590,000 Marines who served in World War II were reservists. That figure is misleading because the entire USMCR in 1940 numbered only 16,400 or so, and only about 15,000 were actually mobilized in 1940–41. Following the 1940–41 mobilization, the USMCR went into a period of inactivation that lasted until 1946. Limited by the authorized strengths for its active duty forces, the Marine Corps classified the vast majority of its World War II officers and a great many of its enlisted Marines as reservists. Therefore, of the nearly 590,000 Marines who served in World War II, only 15,000 or about 2.5 percent were prewar reservists mobilized for war. Therein lies the problem. These mobilized reservists have literally become swallowed up in the massive World War II Marine Corps and lost within its history. Even the otherwise comprehensive The Marine Corps Reserve tends to lump prewar Marine reservists with those who joined after Pearl Harbor when discussing the wartime service of Marine reservists. Consequently, one of the purposes of this article is to highlight the contributions of those Marine reservists mobilized from the OMCR and to fill this significant gap in the historical record of World War II.32

Lessons Learned

The mobilization of the OMCR in 1940 was a significant learning experience for the Marine Corps. One of the most important lessons learned was that the OMCR needed a greater diversification in its Reserve units. The prewar Marine Corps Reserve consisted of just four types of Reserve units: infantry battalion, field artillery battalion, scout bomber squadron, and aviation service squadron. Most of the Reserve units were infantry. While other military occupational specialties (MOSs) were represented in the units, the pre- dominant MOSs were infantry related. As the active duty Marine Corps rapidly expanded in 1940–41, it quickly became apparent that more than just infantry MOSs were needed.

Accordingly, the USMCR leadership planned for diversification of units as they conducted the process of rebuilding the dormant OMCR in the later stages of World War II. These efforts were led by officer-in-charge of the Division of Reserve Colonel Clark W. Thompson and Colonel Melvin J. Maas. Together, they drafted plans to activate 18 infantry battalions; seven field artillery battalions; a battalion each of tanks, amphibious tractors, and antiaircraft artillery; five signal companies; three engineer companies; two weapons companies; and 24 aviation squadrons. Reserve units would be reestablished in most of the cities that host- ed units before the war.33

The vigorous efforts to reestablish the USMCR and its active component paid off in 1946. By year’s end, there were some 2,630 officers and 29,829 enlisted Marines serving in the Reserves. There was an enormous pool of discharged veteran Marines who had served during the war, which enabled the USMCR to rapidly rebuild its manpower with experienced former active duty Marines. Altogether, the new OMCR consisted of 11 infantry battalions, two 105mm howitzer battalions, one 155mm howitzer battalion, one tank battalion, and six fighter squadrons at the end of 1946. This included the reactivated OMCR battalions at Marine Barracks Philadelphia: the 6th Infantry Battalion and the 7th Battalion (Artillery), which had been reestablished as the 1st 155mm Howitzer Battalion. Within a couple years, Women’s Reserve platoons were added to many OMCR units.34 There was one important lesson that the Marine Corps failed to learn after World War II, which was the need to continue to operate the USMCR after its units and personnel had been mobilized. Less than five years after World War II’s end, North Korean forces invaded South Korea. In response, the USMCR was mobilized for war for the second time in 10 years. The mobilization paradigm of 1940 was used again, albeit under much more exigent circumstances. Again, the Marine Corps activated the OMCR units and personnel, relocated them to active duty bases, deactivated the units, and reassigned their personnel to active duty units. Again, the OMCR units went dormant during wartime.

This time the Marine Corps leadership belatedly realized the drawbacks of having its Reserve component go dormant. Accordingly, in 1952, mobilized Marine Corps Reserve members were demobilized, OMCR units were reactivated, and the Reserve component was hastily rebuilt. The fact that the United States was also engaged in a Cold War with the Soviet Union was a factor in this rapid reconstitution of the USMCR. As was the case after World War II, the USMCR adopted greater diversification of its units. After more than 26 years of service as an infantry unit, the 6th Battalion was reactivated as the 2d Depot Supply Battalion.35

The USMCR was not mobilized for the Vietnam War. When next called upon, the Reserves would not adopt the mobilization practices of 1940 and 1950. Marine units were mobilized for Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm in 1990–91 and for Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom in the new millennium. Marine Reserve units mobilized either as detachments to augment other units or whole unit mobilizations. In both cases, the USMCR (renamed Marine Forces Reserve in 1994) continued to function with rear detachments operating when the whole unit was mobilized and deployed. This paradigm has ensured that unit integrity remains, the Reserve force in general continues to operate, and mobilized Reserve units receive the recognition for their service due to them.

Conclusion

The mobilization of the OMCR in November and December 1940 was the second mobilization of the force in its history. The OMCR functioned exactly as it was intended to, providing more than 7,300 trained Marines to help rapidly expand the active duty Marine Corps for war. The mobilization of the OMCR and the utilization of its members brought significant benefits to a Marine Corps attempting to quickly expand in the face of a rapidly deteriorating world situation. The influx of trained reservists helped the Marine Corps to activate the 1st and 2d Marine Divisions. These reservists then served with distinction in the Pacific campaigns and in stateside assignments. The manner in which OMCR members were mobilized also had certain drawbacks. The OMCR went dormant for the duration of the war and had to be completely rebuilt afterwards. Since the OMCR members were absorbed into the larger Marine Corps, their achievements and sacrifices have largely been lost in the larger history of the Marine Corps in World War II.

•1775•

Endnotes

- Bryan J. Dickerson is a historian and author from New Jersey. He served in the U.S. Navy Reserve for eight years, attaining the rating of Religious Program Specialist, 1st Class (Fleet Marine Force), and deploying twice for Operation Iraqi Freedom with squadrons of 2d Marine Aircraft Wing. His book The Liberators of Pilsen: The U.S. 16th Armored Division in World War II Czechoslovakia was published in January 2018. He has a bachelor’s in history from Rowan University and a master’s in American history from Monmouth University.

- Mark Skinner Watson, The War Department–Chief of Staff: Prewar Plans and Preparations, United States Army in World War II (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1991), table 1, 16; Carolyn A. Tyson, A Chronology of the United States Marine Corps, 1935–1946, vol. 2 (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1977), 6; and Adm Ernest J. King, USN, First Report to the Secretary of the Navy, Covering our Peacetime and our Wartime Navy and Including Combat Operations up to 1 March 1944 (Washington, DC: U.S. Navy Department, 1944), 8, 22.

- David I. Walsh, The Decline and Renaissance of the Navy, 1922–1944: A Brief History of Naval Legislation from 1922 to 1944 Pointing Out the Policy of the Government During These Years and Steps Taken to Rebuild Our Navy to Its Present Strength (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1944), 10–12; and Robert J. Cressman, The Official Chronology of the U.S. Navy in World War II (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1999), entries for 30 June 1940 and 19 July 1940, 52, 55.

- Col Susan L. Malone, USMCR, “The Reserves Turn 75,” Marine Corps Gazette 75, no. 9 (September 1991): 58–62; The Marine Corps Reserve: A History (Honolulu: University Press of the Pacific, 2003), chapters 1 and 2; Robert W. Tallent, “In Reserve: The Old Standby,” Leatherneck, November 1954, 76–81; and Col Joseph C. Fegan, “M-Day for the Reserves,” Marine Corps Gazette 24, no. 4 (December 1940): 24–29.

- Fegan, “M-Day for the Reserves,” 27–29; Malone, “The Reserves Turn 75,” 60–61; The Marine Corps Reserve, 50–51; “Reserves,” Leatherneck, January 1941, 37–41; and Tallent, “In Reserve,” 78–79. The modern equivalent for the FMCR and VMCR is the Inactive Ready Reserve (IRR), and the modern equivalent of the OMCR is the Selected Marine Corps Reserve (SMCR).

- Fegan, “M-Day for the Reserves,” 27.

- “In Memoriam: Col Clark W. Thompson, USMCR (Ret),” Fortitudine (Spring–Summer 1982), 23; “BrigGen Joseph R. Knowlan,” in “Twelfth Annual Mess Night Program,” 4th Marine Aircraft Wing, Marine Wing Motor Transport Squadron 4, 31 January 1975 (copy provided by Col Thomas McCabe, USMCR [Ret]), hereafter Knowlan biography; military personnel file of Col Edward P. Simmonds, USMCR (deceased), National Personnel Records Center, National Archives and Records Administration (NPRC-NARA), St. Louis, MO, hereafter Simmonds personnel file; “W. [Woodbridge] S. Van Dyke,” biography, IMDB.com, ac- cessed 21 May 2018; and “Capital Marines ‘Shake Down’ at Quantico,” Washington Post, 10 November 1940, B4.

- LtCol Edward C. Johnson and Graham A. Cosmas, Marine Corps Aviation: The Early Years, 1912–1940 (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1991); Charles L. Updegraph Jr., U.S. Marine Corps Special Units of World War II (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1977), 55; The Marine Corps Reserve, 90; “Gen. Karl Day, 76, A Marine Aviator,” New York Times, 22 January 1973, 34; Myrna Oliver, “Obituary: William Fox, Pioneering Engineer for County,” Los Angeles Times, 15 April 1993, hereafter Los Angeles Times Fox obituary; “William J. Fox, 95, a War Hero, Engineer, Stunt Man and Cowboy,” New York Times, 17 April 1993, hereafter New York Times Fox obituary; “Gen. Melvin J. Maas, 65, Dies,” New York Times, 14 April 1964; Paul Nelson, “How a Conservative Re- publican Got Elected to Congress by Democratic St. Paul—Seven Times,” MinnPost, 5 May 2015; and Robert Sherrod, History of Marine Corps Aviation in World War II (Washington, DC: Combat Forces Press, 1952), 3, 28.

- Assistant Commandant BGen Vandegrift was acting under the authority of Commandant MajGen Holcomb. Fegan, “M-Day for the Reserves,” 27–29; Malone, “The Reserves Turn 75,” 60–61; The Marine Corps Reserve, 50–51; “Reserves,” 37–40; Tallent, “In Re- serve,” 78–79; Acting Commandant MajGen Alexander A. Van- degrift, Mobilization Orders, 15 October 1940, quoted in Fegan, “M-Day for the Reserves,” 24; Col Allan R. Millett, Semper Fidelis: A History of the United States Marine Corps (New York: MacMillan, 1980), 347; Commandant MajGen Thomas C. Holcomb, memo to Chief of Naval Operations, “Mobilization of Organized Ma- rine Corps Reserve,” 7 October 1940, Correspondence Files of the Commandant of the Marine Corps, NARA, RG 38, hereafter 7 October 1940 CMC Memo to CNO; “Orders 24-HR Day For Plane Plants,” New York Times, 11 October 1940, 13; “Marine Corps Reserve Called to Active Duty,” Washington Post, 11 October 1940, 1; Commandant MajGen Thomas C. Holcomb, memo to Com- manding General, Fleet Marine Force, Marine Corps Base San Diego, CA, “Mobilization of Organized Marine Corps Reserve,” 9 October 1940, Correspondence Files of the Commandant of the Marine Corps, NARA, RG 38, hereafter CMC memo to CG FMF MCB San Diego, 9 October 1940; Commandant MajGen Thomas C. Holcomb, memo to Commanding Officer, Marine Barracks, Navy Yard, Philadelphia, PA, “Mobilization of 6th Marine Corps Reserve Battalion,” 9 October 1940, Correspon- dence Files of the Commandant of the Marine Corps, NARA, RG 38, hereafter CMC memo to CO MB NY Philadelphia, 9 Oc- tober 1940; Commandant MajGen Thomas C. Holcomb, memo to Commanding Officer, Marine Barracks, Navy Yard, Norfolk, VA, “Mobilization of Organized Marine Corps Reserve,” 9 Octo- ber 1940, Correspondence Files of the Commandant of the Ma- rine Corps, NARA, RG 38, hereafter CMC memo to CO MB NY Norfolk, 9 October 1940; Commandant MajGen Thomas C. Holcomb, memo to Commanding Officer, Marine Barracks, Navy Yard, Puget Sound, Bremerton, WA, “Mobilization of 20th Marine Corps Reserve Battalion,” 9 October 1940, Correspondence Files of the Commandant of the Marine Corps, NARA, RG 38, hereafter CMC memo to CO MB NY Bremerton, 9 October 1940; Commandant MajGen Thomas C. Holcomb, memo to Commanding Officer, Marine Barracks, Navy Yard, Mare Island, Vallejo, CA, “Mobilization of 12th Marine Corps Reserve Battalion,” 9 October 1940, Correspondence Files of the Commandant of the Marine Corps, NARA, RG 38, hereafter CMC memo to CO MB NY Mare Island, 9 October 1940; and Commandant MajGen Thomas C. Holcomb, memo to Commanding General, Marine Barracks, Quantico, VA, “Mobilization of Organized Ma- rine Corps Reserve,” 9 October 1940, Correspondence Files of the Commandant of the Marine Corps, NARA, RG 38, hereafter CMC memo to CO MB Quantico, 9 October 1940.

- CMC memo to CG FMF MCB San Diego, 9 October 1940.

- The Marine Corps Reserve, 276–77; and “Reserves,” 37–40.

- Fegan, “M-Day for the Reserves,” 24–29.

- “West Coast,” Leatherneck, February 1941, 44–52; “Reserves,”Leatherneck, January 1941, 37–41; The Marine Corps Reserve, 59, 60; and “Marine Reserves to Move,” New York Times, 1 January 1941, 24.

- “Marine Reserves Start Active Duty,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 8 November 1940, 6; “Detachments,” Leatherneck, April 1941, 60–68; “Detachments,” Leatherneck, June 1941, 46–55; LtCol Ronald J. Brown, USMCR, A Brief History of the 14th Marines (Washing- ton, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1990), 62; Squadron Historical Chronology, March 2009, Marine Wing Support Squadron (MWSS) 472, Marine Wing Support Group 47, 4th Marine Aircraft Wing, Marine Forces Reserve, on file at MWSS-472, hereafter MWSS-472 chronology; and “10th Motor Transport Battalion Has Trained Philadelphia Reserves 38 Years,” Newsletter (4th Marine Reserve and Recruiting District, Philadelphia, PA), August 1964, RG 127, NARA, 8–9. The 7th Reserve Battalion (Field Artillery) is today known as 3d Battalion, 14th Marines, of the 4th Marine Division. The 6th Infantry Battalion in 1964 was then known as the 10th Motor Transport Battalion.

- Kenneth W. Condit, Gerald Diamond, and Edwin T. Turnbladh, Marine Corps Ground Training in World War II (Washing- ton, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1956), 5–6; and The Marine Corps Reserve, 59–60, 90–91.

- LtCol Frank O. Hough, USMCR, Maj Verle E. Ludwig, and Henry I. Shaw Jr., Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, vol. 1, History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1958), 47–48; Danny J. Crawford et al., The 2d Marine Division and Its Regiments (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 2001), 1; and Danny J. Crawford et al., The 1st Marine Division and Its Regiments (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1999), 1.

- The 1st Marine Brigade (Provisional) was a new creation specific to the Iceland operation, unrelated to the 1st Marine Brigade, which had been expanded to become the 1st Marine Division in February 1941.

- Col James A. Donovan, Outpost in the North Atlantic: Marines in the Defense of Iceland, Marines in World War II Commemorative Series (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1992), 2–5.

- Smith commanded 1st Battalion, 6th Marines, and Shoup was R-3 (operations) officer for the 6th Marine Regiment. For the mobilized reservists’ assignments, see “Staff and Command List,” in Donovan, Outpost in the North Atlantic, 32; see also The Marine Corps Reserve, 97.

- Simmonds personnel file; Col Francis Fox Parry, Three War Marine: The Pacific, Korea, Vietnam (Pacifica, CA: Pacifica Press, 1987), 73; Knowlan biography; Patrick H. Butler III, “Thompson, Clark Wallace,” Handbook of Texas Online, accessed 10 July 2017; and “In Memoriam: Col Clark W. Thompson,” 23. Edward Simmonds retired from the USMCR as a colonel in 1952. Joseph Knowlan retired from the Reserve in 1954 at the rank of brigadier general. Thompson retired from the Reserve on 1 June 1946 as a colonel.

- Updegraph, U.S. Marine Corps Special Units of World War II, 55–56; Sherrod, History of Marine Corps Aviation in World War II, 119, 144, 257, 439, 441, 445, 444, 448; “Gen. Karl Day, 76, a Marine Aviator,” 34; The Marine Corps Reserve, 90; New York Times Fox obituary; Los Angeles Times Fox obituary; William Joseph Fox casualty cards, Marine Corps History Division, accessed 21 June 2017; Maas obituary; and Melvin J. Maas casualty cards, Marine Corps History Division, accessed 21 June 2017.

- Knowlan biography; LtGen del Valle quoted in The Marine Corps Reserve, 98; Parry, Three War Marine, 43 and chapter 6; and “Marine Reserves to Move,” 24.

- Kenneth E. John, “Medal of Honor Winner Justice Chambers Dies,” Washington Post, 1 August 1982, hereafter Chambers obituary; “Colonel Justice Marion Chambers, USMCR (Dec),” biography, Marine Corps History Division, hereafter Chambers biography; The Marine Corps Reserve, 87–88; Parry, Three War Marine, 43, 46; Brown, A Brief History of the 14th Marines, 42; and Richard Harwood, A Close Encounter: Marine Landing on Tinian, Marines in World War Two Commemorative Series (Washing- ton, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1994), 19. Chambers was wounded on Tulagi, Saipan, and Iwo Jima. His wounds on Iwo Jima were so severe that he was medically retired at the rank of colonel in 1964.

- “Brigadier General James Roosevelt, USMCR (Dec),” biography, Marine Corps History Division, hereafter Roosevelt biography; military personnel file of BGen Charles Humphreys Cox, USMCR (Dec), NPRC-NARA, hereafter Cox personnel file; and military personnel file of BGen Gooderham Lauten McCormick, USMCR (Dec), NPRC-NARA, hereafter McCormick personnel file. Roosevelt retired in October 1959 and was promoted to brigadier general for meritorious combat service. After being discharged in 1946, Cox reactivated the 6th Battalion; he retired in 1964. McCormick was discharged in 1948 and retired in October 1956. Upon retiring, both Cox and McCormick were promoted to brigadier general for meritorious combat service.

- The Marine Corps Reserve, 85, 90, 92; “Brigadier General Joseph J. Foss, ANG (Dec),” biography, Marine Corps History Division; Alexander S. White, Dauntless Marine: Joseph Sailer Jr., Dive-Bombing Ace of Guadalcanal (Fairfax Station, VA: White Knight Press, 1996), 104–16; Sherrod, History of Marine Corps Aviation in World War II, 120, 140, 441, 444; casualty cards of Nathaniel S. Clifford, Marine Corps History Division, accessed 21 June 2017; and “Nathaniel S. Clifford,” American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed 21 June 2017. After the war, Foss joined the South Dakota National Guard and rose to the rank of brigadier general.

- “History of the 16th Battalion, United States Marine Corps Reserve,” Collection on the 16th Battalion United States Marine Corps Reserve, 1939 to 1990, S1242, Indiana State Library Special Collections; U.S. Marine Corps Reserve, 16th Battalion, Change Sheet 313, 8 November 1940, Collection on the 16th Battalion United States Marine Corps Reserve, 1939 to 1990, S1242, Indi- ana State Library Special Collections; and Welton W. Harris II, “Broomstick Brigade Rides Again,” Indianapolis News, November 1940, E-1, Collection on the 16th Battalion United States Marine Corps Reserve, 1939 to 1990, S1242, Indiana State Library Special Collections. My thanks to Laura Eliason of the Indiana State Library for her assistance in obtaining the preceding documents. “Nelson C. Roetter Obituary,” Indianapolis Star, 3 February 2013; and “James ‘Eddie’ Hightshue Obituary,” Flanner and Buchanan Funeral Centers, Zionsville, IN, 30 January 2014. The information on Floyd H. Davis, John A. Kraig, Harry H. Walter, Robert W. Edwards, Paul C. Phillips, Frederick A. Roetter, and Albert P. Rickert was obtained by comparing the 16th Battalion’s mobilization roster with the Marine Corps History Division’s casualty cards database, accessed 12 July 2017. The 16th Infantry Battalion’s mobilization roster was obtained from the Indiana State Library Special Collections.

- Casualty Cards Database, Marine Corps History Division, ac- cessed 12 July 2017; ABMC Burials and Memorials online database, American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed 19 July 2017; and State Summary of War Casualties from World War II for Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard Personnel from Indi- ana, 1946, U.S. Department of the Navy, Office of Public Information, Casualty Section, June 1946, 305199, NARA, accessed 16 July 2017. The 16th Infantry Battalion’s mobilization roster obtained from the Indiana State Library Special Collections was cross-referenced with the above databases to ensure accuracy in identifying those battalion members who became casualties during World War II.

- “BrigGen Edward B. Meyer, USMC,” in “Twelfth Annual Mess Night Program,” Marine Wing Motor Transport Squadron 4; military personnel file of LtCol Norman J. E. Murken, USMCR (Dec), NPRC-NARA, hereafter Murken personnel file; “2nd Lt Anthony D. Davitt,” Wilkes-Barre (PA) Record, 30 January 1945, 3; Casualty Card Database, Marine Corps History Division, ac- cessed 6 June 2017; and “2nd Lt Anthony D. Davitt,” Wilkes-Barre (PA) Record, 24 April 1945, 11. Meyer served in both the Korean and Vietnam Wars and retired as a brigadier general; he was mobilized again for the Korean War and retired from the USMCR as a lieutenant colonel. Davitt was wounded while serving with the 3d Battalion, 24th Marines, on Iwo Jima.

- The Marine Corps Reserve.

- Samuel Eliot Morison, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, 15 vols. (Boston: Little, Brown, 1947–62); David J. Ulbrich, Preparing for Victory: Thomas Holcomb and the Making of the Modern Marine Corps, 1936–1943 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2011), 88; Sherrod, History of Marine Corps Aviation in World War II; Henry I. Shaw Jr., Opening Moves: Marines Gear Up for War, Marines in World War Two Commemorative Series (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1991); and Hough, Ludwig, and Shaw, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, chapter 5.

- Condit, Diamond, and Turnbladh, Marine Corps Ground Training in World War II; and The Marine Corps Reserve, chapter 3.

- For example, see The Marine Corps Reserve, 59. The remaining reservists were not mobilized due to being physically disqualified or having vital defense jobs.

- The Marine Corps Reserve, 102–3.

- The Marine Corps Reserve, 102–3; Arthur Mielke, “The Peacetime USMCR,” Leatherneck, November 1946, 42–43; and Col Mary V. Stremlow, USMCR, A History of the Women Marines, 1946–1977 (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1986), 40–41.

- Capt Ernest H. Giusti, Mobilization of the Marine Corps Reserve in the Korean Conflict, 1950–1951 (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1951); and TSgt Robert A. Suhosky, “Philadelphia Reservists,” Leatherneck, November 1955, 34–37.