PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

There are significant parallels between the 1982 Falklands War and future conflicts the U.S. military will face. Although 30 years have passed and technology has changed, the Falklands War provides critical insight to the U.S. military as it develops ways to counter the Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) threat. Leading up to Operation Corporate, Great Britain’s military was slowly ending a protracted counterinsurgency conflict in Ireland, facing budget and force reductions, and focused on defending the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) from a potential Soviet invasion. In April, with little warning to the British military headquarters, Northwood, Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands.2 Britain was caught off guard and unprepared to face a near peer threat 8,000 miles from the British Isles and without assistance from NATO. Argentina, with a sizable force that included modern air and ground systems, opposed British forces with a modern A2/AD threat.3 Fast forward to today, when the focus for the U.S. military is a withdrawal from counterinsurgency, reduction in forces and budgets, and a renewed focus against potential Chinese and Russian threats. The United States’ focus today, just as it was for Great Britain in 1982, is preparing for the most dangerous course of action. While China and Russia do pose a threat to U.S. interests, a war with either is not the most likely course of action in the near term. The United States will continue to face conflicts in the arc of instability with adversaries that pose formidable A2/AD threats to smaller Marine Corps units, such as an Expeditionary Strike Group/Marine Expeditionary Brigade (ESG/MEB) and Amphibious Ready Group/ Marine Expeditionary Unit (ARG/MEU). Despite advancements in today’s A2/AD weapons technology, the 1982 Falklands War offers critical insights to how U.S. naval forces can counter modern-day threats and prepare for future threats to an amphibious force.

The Dawn of Modern A2/AD Warfare: Establishing the A2/AD Environment

By the early 1980s, Argentina, as compared to the rest of Latin America, possessed a modern, well-equipped and -trained military force. The United States and other NATO countries, including the UK, supplied Argentina with some of the most modern equipment for the late 1970s and early 1980s.4 In the context of A2/AD, Argentina possessed excessive amounts of antipersonnel, antitank, and antiship mines; modern night vision optics; antitank missile systems; antiaircraft missile and gun systems; and heavy towed howitzers. Furthermore, their air and naval components possessed a variety of modern fast attack aircraft, with one of those platforms capable of carrying the AM-39 Exocet air-to-surface antiship cruise missile system.5 Last, Argentina was a strong ally to the United States against the Soviet Union; for a Latin American country, this represented a strong bargaining piece. Leading up to the spring of 1982, Argentina held a strong diplomatic and military position in the south Atlantic.

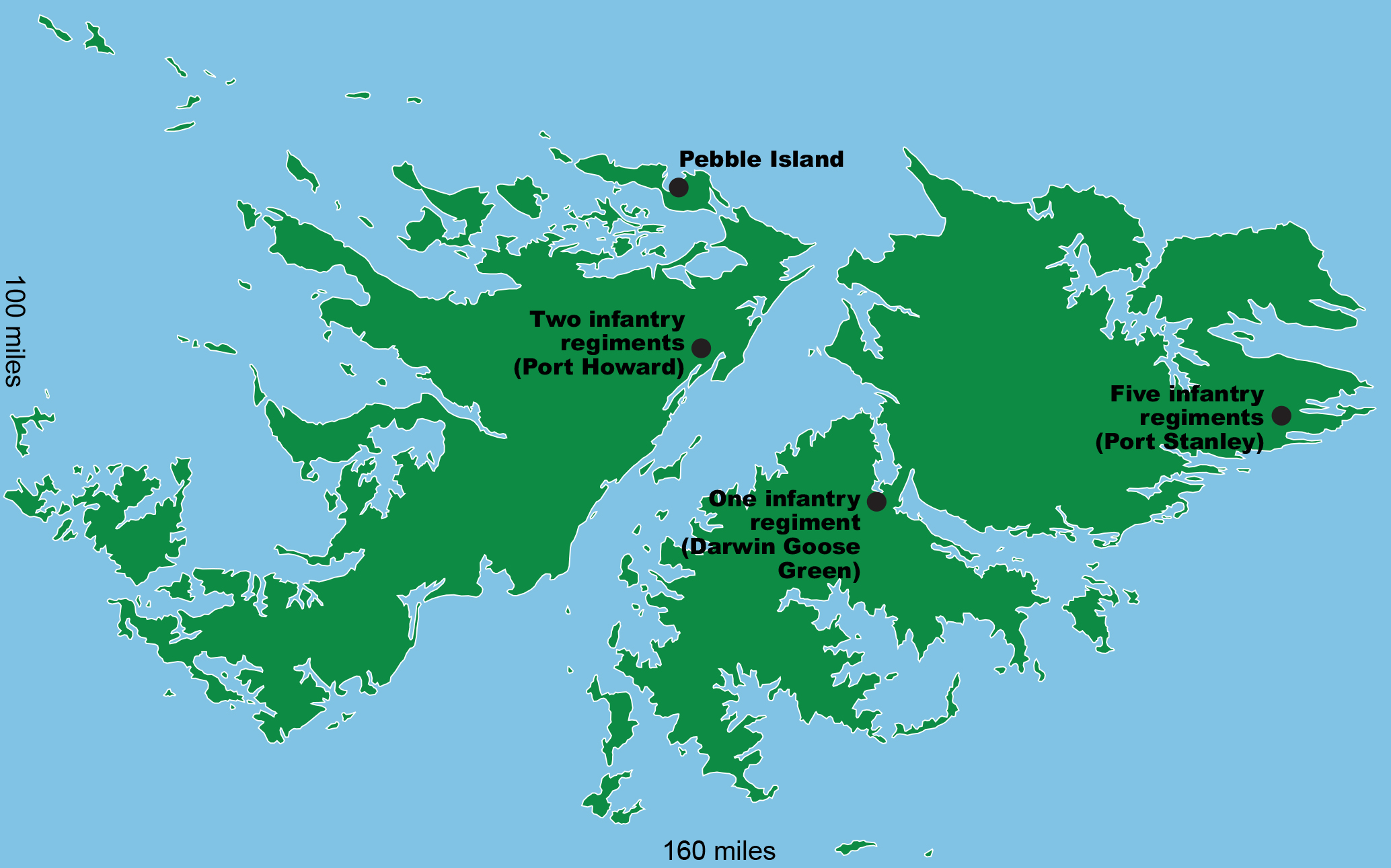

Argentinean military forces invaded the Falkland Islands, 300 miles east of Argentina and 8,000 miles south of Great Britain, on 2 April 1982 with an invasion force of 2,000 soldiers and marines.6 The invasion was a strategic move by the Argentinean government to gain national solidarity and instill popularity in Argentina’s president and leader of its military junta, General Leopoldo Fortunato Galtieri.7 The Argentineans focused their invasion at the population center of Port Stanley on East Falkland. They faced little opposition from a small garrison of 70 Royal Marines and a small contingent of local defenders.8 During most of April, the Argentinean force increased to around 13,000 military personnel with a majority placed in a defensive posture around Port Stanley (figure 1).9

Figure 1. Argentinean force laydown of the Falkland Islands, 2 April–14 June 1982. Created by author, courtesy of History Division

Argentina placed eight infantry regiments on East and West Falkland: two regiments on West Falkland and six regiments on East Falkland, with five of those centered around Port Stanley and supported by an artillery regiment.10 Protecting the skies with antiaircraft weapon systems around Port Stanley, the Argentine Army and Air Force defended with 12 30mm Hispano Suiza guns, 6 Tiger Cat missile launchers, 8 35mm Oerlikons, 11 20mm Rheinmetall guns, and 1 Roland twin missile launcher.11 Additionally, the Argentineans possessed AN/TPS-43 and AN/TPS-44 radar units, vital in their ability to see beyond the horizon.12 Ground antiair units alone presented a formidable protective shield against British air and naval forces.

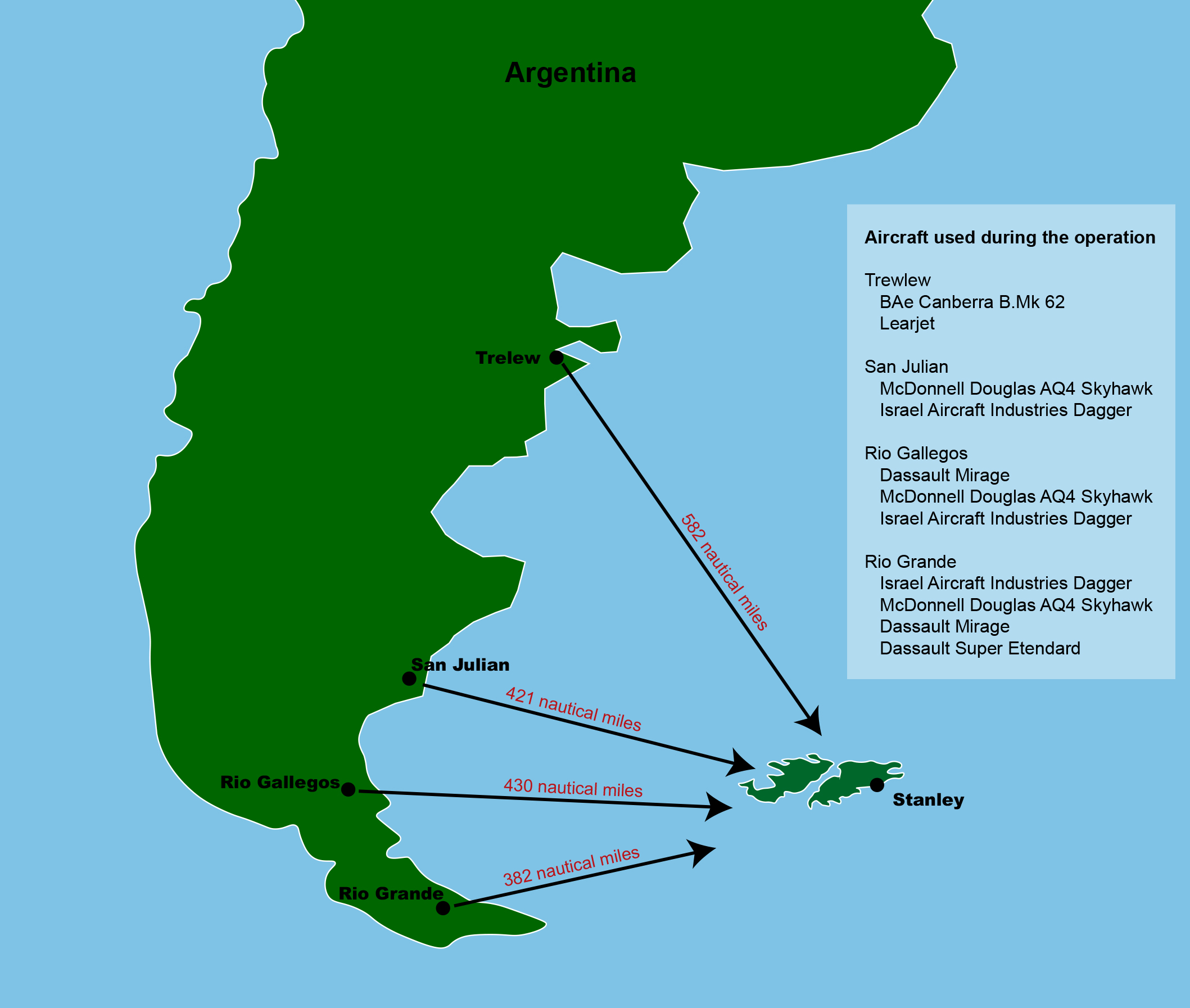

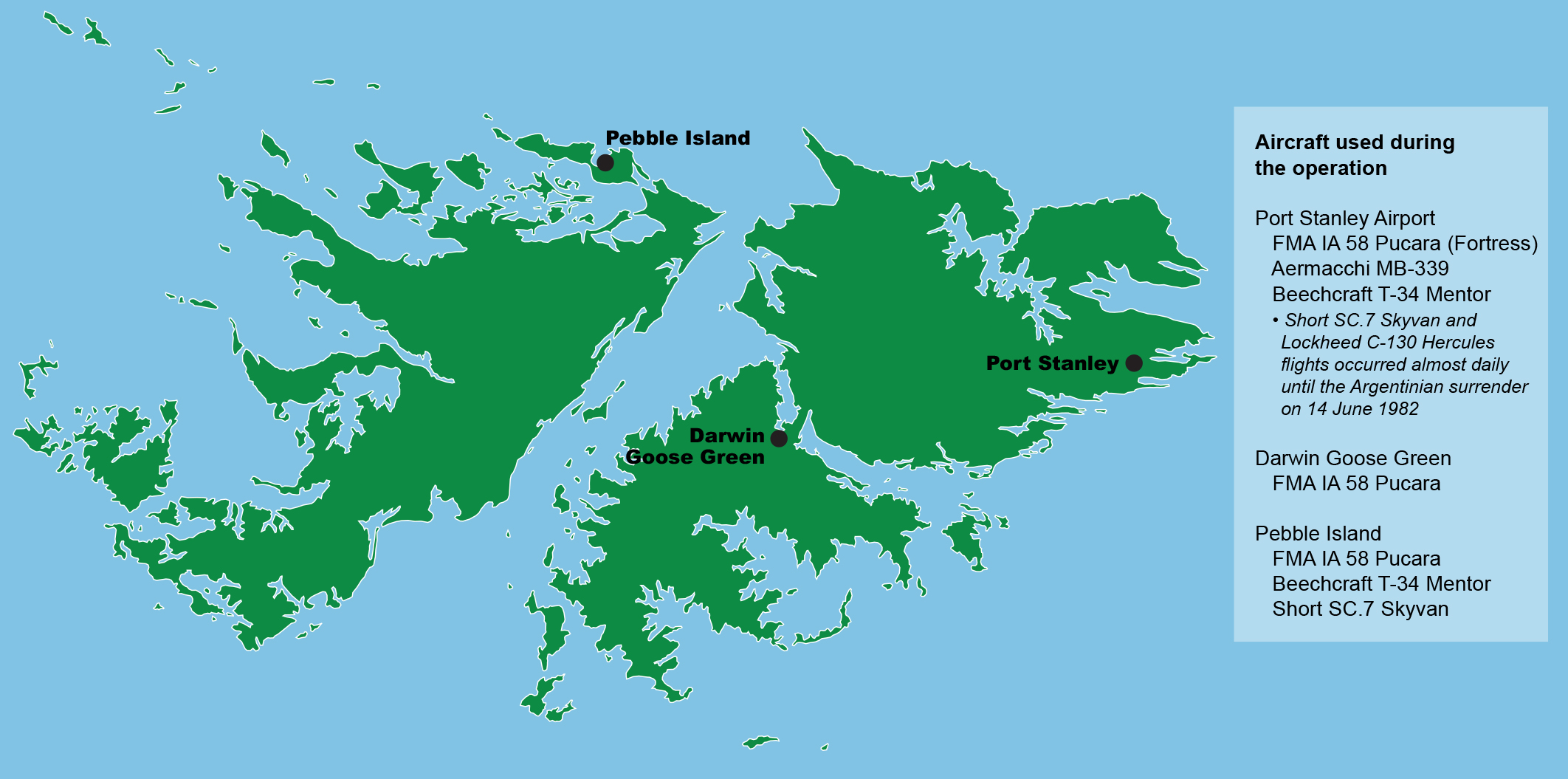

In addition to the ground forces on the Falklands, Argentina possessed one of the most sizable naval fleets and air forces in Latin America.13 Their naval forces included not only cruisers, corvettes, amphibious shipping, and a battleship but also submarines and an aircraft carrier. In total, Argentina possessed 17 combatant ships and three submarines to maintain maritime superiority.14 Although relatively large, the Argentinean fleet was an aging fleet with World War II-era ships, or at best ships built in the 1960s without modernization, besides the MM-38 Exocet.15 Due to the Falklands’ close proximity to Argentina, Argentinean air components stationed modern fighter-attack and fighter-bomber aircraft on the Falklands or near the coast of Argentina well within range of the Falklands. From the Argentinean mainland, Argentine air elements could strike targets in and around the Falklands with their assortment of Dassault Mirage IIIEA’s, Israeli Aircraft Industries (IAI) Neshers (Daggers), and McDonnell Douglas AQ-4 Skyhawks with extended range and time on station via aerial refueling provided by Lockheed C-130 Hercules.16 Positioned on the Falklands, Argentina placed 34 Fabrica Militar de Aviones (FMA) IA-58A Pucara, Beechcraft T-34C Turbo-Mentor, and Aermacchi MB 339 light attack aircraft (figures 2A and 2B).17 While these aircraft may have been small and not nearly as fast as other aircraft, the British still considered them a viable threat. The most dangerous Argentinean aircraft to the British task force was the French-made Dassault Super Etendard with the AM-39 Exocet air-to-surface antiship cruise missile. In total, Argentina possessed 130 operational fixed-wing attack aircraft for the defense of the Falklands.18

Figure 2A. Argentinean air bases supporting operations in the Falklands and types of aircraft. Created by author, courtesy of History Division

Figure 2B. Argentinean air bases on the Falklands and types of aircraft. Created by author, courtesy of History Division

By the end of April 1982, Argentina constructed a defense at the water’s edge with an air-mobile reserve, supported by a navy and air force to maintain superiority of the Falklands. Argentina had a well-established A2/AD environment that extended from the Argentinean coast to about 150 miles east of East Falkland. If the Battle of Gallipoli is considered the dawn of modern amphibious warfare, Argentina’s occupation of the Falkland Islands can be considered the dawn of the modern A2/AD warfare.

Movement to the Amphibious Objective Area: The Task Force Sets Sail

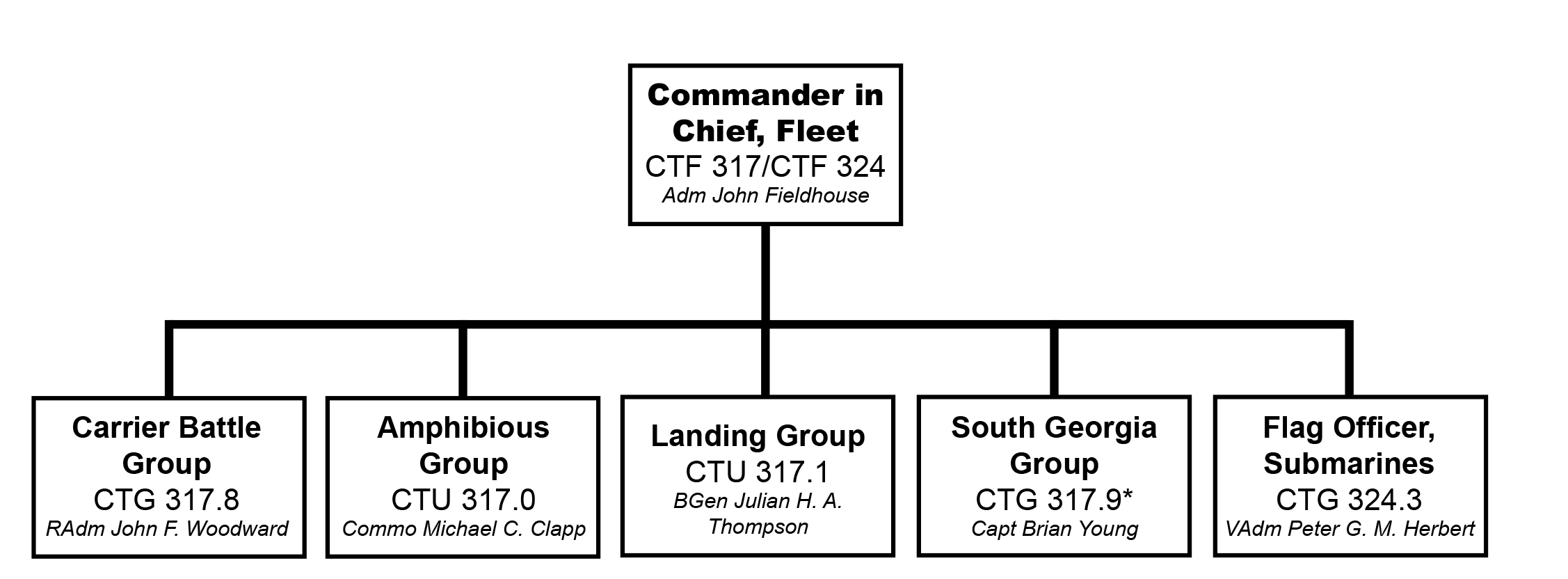

From the British standpoint, the 1982 Falklands War was not only unexpected, it also was “unplanned.”19 No operational plan existed in the event of war over the Falklands, nor were there substantial forces in the south Atlantic to provide a swift or effective response.20 From the start of the scrap metal incident on South Georgia Island in mid-March to preinvasion on 1 April, the British government and military commanders held planning meetings to discuss and debate diplomatic and military responses to a possible Argentinean invasion, but these discussions yielded very little detail, nor did they provide guidance to commanders.21 With the invasion underway and news arriving to the British public on 2 April, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher announced the following day before the House of Commons, “a large task force will sail as soon as preparations are complete.”22 With her public statement, Admiral Sir Henry Leach, First Sea Lord, designated Admiral Sir John Fieldhouse as commander in chief Fleet, commander Task Force (CTF) 317/CTF 324 (figure 3).23 The Royal Navy was no longer planning but instead embarking a force that had not been seen in scope and size since the Suez Crisis of 1956.24 Amphibious Operations, Joint Publication 3-02, dictates the five phases of an amphibious operation as planning, embarkation, rehearsal, movement, and action (PERMA).25 These phases can be looked at as subphases within the Joint Phasing Model.26 Due to the relative surprise of the Argentine invasion and the political and strategic need to show British resolve, the British task force used the nonstandard phases of an amphibious operation: embarkation, movement, planning, rehearsal, and action (EMPRA).27 Typically, a U.S. amphibious force will execute PERMA or EMPRA during Phases 0–3 under the geographic combatant commander’s or Joint Force commander’s operational plan.28 EMPRA played a large role in the many difficulties the British faced in the following weeks, the first of which was what units to assign CTF 317.

Outside of plans designed for supporting NATO within Europe, the British military headquarters at Northwood did not possess plans that encompassed a brigade-size deployment. Instead, the embarkation plans used for Operation Corporate were based on Norway’s contingency plans for countering a Soviet invasion.29 This plan would account for the type of supplies needed for a cold-weather environment but not the ships and antiair systems needed to oppose Argentinean forces in the air and on the seas 8,000 miles from the British homeland. In response to the diverse threat posed by Argentina, the task force was correspondingly diverse, and assembled with ships and ground units not typically accustomed to operating with each other.

Figure 3. Chain of command / task organization, 9 April–28 May 1982. Once Operation Paraquet was complete, most of the ships assigned to CTG 317.9 rejoined CTG 317.8 for the remainder of Operation Corporate. Created by author, courtesy of History Division

A larger force than that assigned to the Norway plan was required due to the increasing Argentinean ground force on the Falklands. The Royal Marines’ 3 Commando Brigade (3CDO), commanded by Brigadier General Julian H. A. Thompson, was the assigned force for the Norway contingency plan. 3CDO’s yearly training in Norway, combined with its Arctic Warfare Cadre, made 3CDO the ideal choice for the austere, cold-weather environment of the Falklands. Yet 3CDO—the premier British ground force—was not enough in the face of a larger, modern force.

Royal Marine commandos, by their nature, are extremely fit, agile, and above all expeditionary. Any unit assigned directly to 3CDO needed to conform to this model. The best option were the British Army’s paratrooper battalions. In the end, 3d Battalion, Parachute Regiment (3PARA) and 2PARA reinforced 3CDO.30 Furthermore, 3CDO received an artillery battalion, a Rapier antiaircraft battery, additional communications and signals equipment and personnel, and Commando Logistics Regiment 3 (CLR3). This brought the initial landing force, 3CDO, to around 5,500 marines and paratroopers.31 This was a substantial force to penetrate the A2/AD bubble and land successfully.

To fracture the A2/AD bubble, the task group was comprised of more than 100 ships and submarines, with the majority of them embarking from Great Britain and Gibraltar or already underway from the mid-Atlantic. Operational control was placed in the hands of Rear Admiral John F. “Sandy” Woodward, designated commander of Task Group (TG) 317.8.32 Of the 100-plus ships, warships were the smaller percentage of the task force as compared to support ships.33 Combatant ships included two aircraft carriers, eight guided missile destroyers, 15 frigates, one diesel and five nuclear powered submarines, two amphibious assault ships, three mine sweepers, and five small vessels.34 The Royal Fleet Auxiliary (RFA) supported the carrier group and the amphibious task force, providing 23 ships, while the British commercial merchant fleet provided an additional 40 ships classified as ships-taken-up-from-trade (STUFT).35

Gaining and maintaining control of the sea by Royal Navy combatants was only half of the solution to the maritime problem. The task force embarked 74 aircraft, both rotary and fixed-wing. As with any operation, aircraft conducted not only combat air patrols (CAP) to maintain air superiority but also antisurface and antisubsurface operations to maintain sea superiority. The most decisive of these aircraft were the 33 Royal Navy British Aerospace Sea Harrier FRS.Mk 1s and Royal Air Force (RAF) Hawker Siddeley GR.Mk3 Harriers.36 These Harriers were used to protect the fleet against air and surface threats and for close air and deep air support (CAS and DAS) pro- vided to special operations and the landing force. Additionally, to protect the fleet against the Argentine submarine threat, the task force embarked 25 antisubmarine helicopters.37 Finally, the task force possessed 28 helicopters for assault support.38

As for landing force logistics, the task force loaded its complement of ships as items appeared at their ports of embarkation. To meet the prime minister’s intent, the majority of combatants sailed in 72 hours, with the last few underway by 7 April.39 Due to the impromptu loading of ships, identification and reorganization of cargo for debarkation took nearly three weeks.40 This reorganization was done while underway and at Ascension Island, the intermediate staging base for the task force halfway between Great Britain and the Falklands. Restow of supplies and equipment became the priority for the task force to have a timely off-load in the Falklands, but it came at the cost of more effective planning and rehearsals.41 EMPRA and the task force’s haphazard means of embarkation would cause additional problems as the force closed on the Falklands.

Shaping the Amphibious Operations Area

Rather than conducting shaping operations for months or multiple weeks, only 20 days of shaping operations were available in support of Operation Corporate. The task force was under a very tight timeline because of the coming south Atlantic winter, and the carriers were expected to operate until the Northern Hemisphere’s fall before they would be needed to conduct critical in-port maintenance. Operationally, the task force accomplished little in the immediate weeks following the Argentinean invasion due to the 8,000 miles of separation between the two opposing forces. At midnight on 12/13 April, the British government announced a maritime exclusion zone (MEZ) of 200 nautical miles around the Falkland Islands enforced by three Royal Navy nuclear submarines.42 Drawing first blood at this point could have prevented a diplomatic solution to the crisis. Instead of attacking the Argentine Navy, the British submarines observed the opposing naval forces. Not only were the submarines able to gather accurate intelligence concerning the movement and locations of the Argentine Navy, but they were also able to ascertain that sea mines were in fact being placed off the coast of Port Stanley and that coastal defenses were in place.43 With British submarines providing real-time intelligence, the task force could turn to more detailed planning.

As the task force gathered around Ascension Island, Admiral Fieldhouse flew to the intermediate staging base and transferred to the HMS Hermes (R 12), Woodward’s flagship, to meet with his commanders on 17 April.44 Fieldhouse had two main goals for this meeting. One was to stress the need to close in on the Falklands as soon as possible before popular support in the UK was lost. The other was to review and provide recommendations to the landing plan. The commander, Amphibious Task Force (ATF), Commodore Michael C. Clapp, designated commander of Task Unit (TU) 317.0, and the commander, Landing Force, Brigadier General Thompson, designated TU 317.1, could not provide a definitive answer for a landing site at that time, but they were able to determine the following requirements for shaping operations to successfully land the landing force regardless of the location:

- The total MEZ must be effective and remain so throughout Operation Corporate.

- The threat of the Argentine aircraft carrier must be removed.

- Air and sea superiority must be established and held over East and West Falkland and the surrounding area.

- Port Stanley airfield must be neutralized (including air defense weapons) and the Argentine air assets (both fixed wing and helicopter) stationed on East and West Falkland must be destroyed.

- Accurate intelligence of beaches, terrain, and enemy positions is essential.

- Argentine logistic dumps must be harassed and their effectiveness reduced.45

Out of the six requirements for shaping operations, four pertained to gaining and maintaining access. The need to control the air and sea prior to the ATF’s arrival was not lost on Woodward, Clapp, or Thompson.

With political pressure gathering each day, and regardless of the task force’s readiness, it was time to close on the Falklands.46 Woodward’s carrier battle group departed Ascension Island on 18 April, arriving in range of the MEZ for the group’s Harriers by 30 April, thus turning the MEZ into a total exclusion zone (TEZ).47 Concurrent with TG 317.8 commencing operations to gain access, Clapp’s amphibious force (TU 317.0) with Thompson’s reinforced 3CDO (TU 317.1) started its 4,000-mile movement from Ascension Island to the Falklands.48

Gain and Maintain Access: Enforcing the TEZ

Woodward’s battle group had a multitude of objectives to accomplish before the amphibious landing, with the most important of those being to gain air and sea superiority. With South Georgia Island secured and some of the ships from the South Georgia Group returning to Woodward, TG 317.8 consisted of 12 combatant ships, the majority of the helicopters for antisubmarine warfare, assault support for special operations, and the Harriers for CAP and CAS/ DAS.49 Additionally, the submarine force (TG 324.3) possessed six submarines in the south Atlantic, with some of those submarines responsible for enforcing the TEZ.50

Securing the sea and air were simultaneous missions, but it was securing the air that proved most difficult throughout the operation. Identifying the route from Ascension to the Falklands was not hard considering the British task force was under political pressure to make its presence known in the south Atlantic as soon as possible, and the Argentineans were well aware of this pressure. The task force had only one choice: to travel the fastest possible route to the Falklands in a straight line.

On 21 April, well before the task force arrived at the exclusion zone, an Argentine Air Force Boeing 707, the first of many, located Woodward’s carrier battle group. The sighting of 707s would continue over the following days as the task force maneuvered south. Considering the Argentinean 707s were unarmed and well north of the TEZ, there was little the task force could do besides launch Harriers to intercept and ob- serve.51 After such actions became daily occurrences, the British government released a statement declaring that the British task force would engage any Argentinean military aircraft coming within 25 nautical miles of British ships. Encountering “nonhostile” Argentinean aircraft at 25,000 feet and noncombatant shipping outside of the TEZ raised issues for the task force’s rules of engagement.

Rules of engagement were a continuous topic of discussion with very open-ended answers during the conflict. Within the TEZ, rules of engagement were not an issue. It was outside of the TEZ where issues arose as soon as the task force arrived at Ascension Island. As with any military operation, the element of surprise is a must. Although the task force went to great lengths to disguise its movement, it was still extremely difficult to conceal more than 100 ships relatively massed together in the south Atlantic. Throughout the operation, commanders debated whether the task force could and should engage Argentinean forces outside of the TEZ.

Gain and Maintain Maritime Superiority: The Unseen Power of the Submarine Force

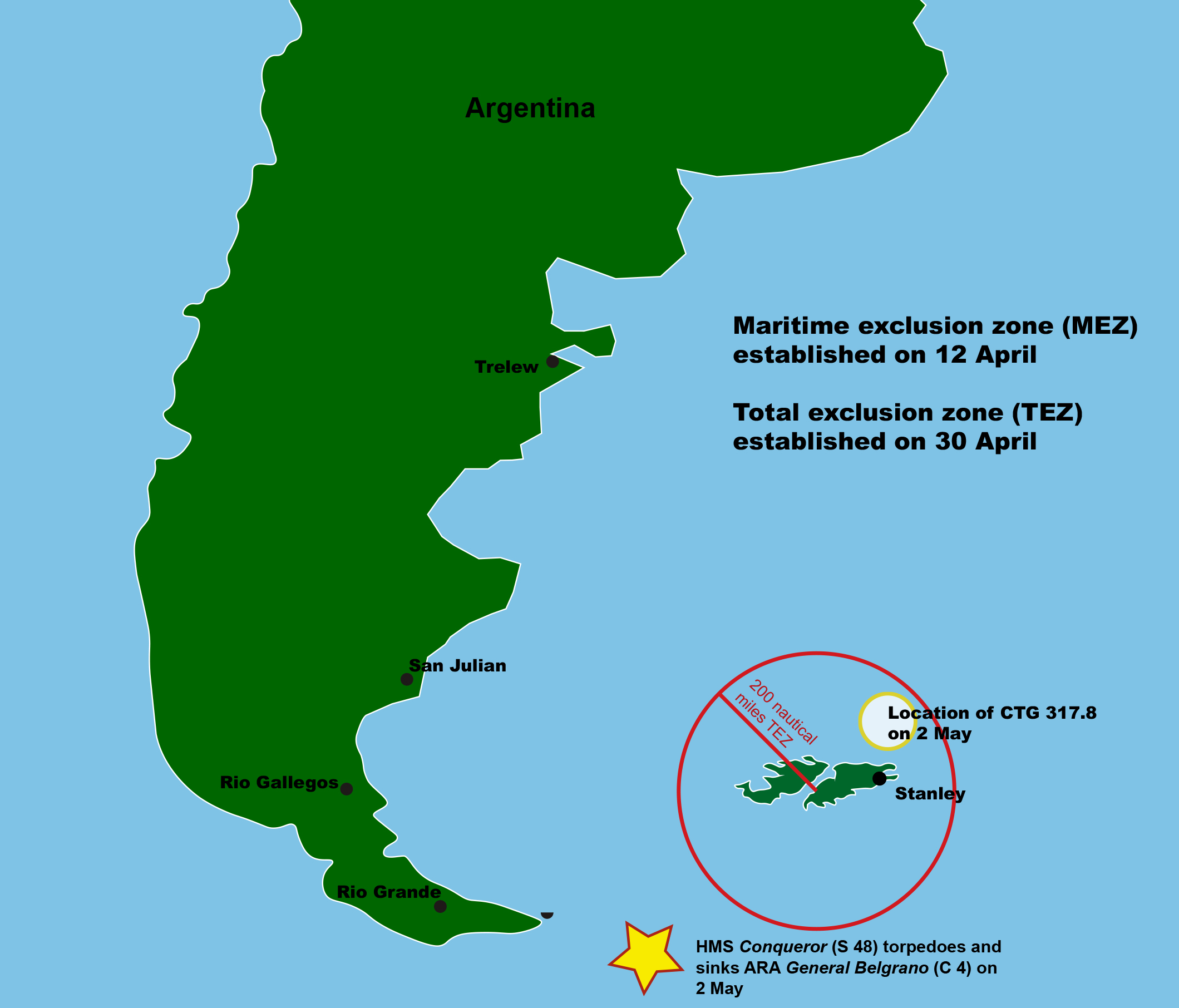

Woodward’s carrier battle group entering the TEZ was the forcing function to apply more liberal action within the rules of engagement constraints. On 2 May, the Argentinean cruiser ARA General Belgrano (C 4), escorted by two destroyers, was underway 40 nautical miles southwest of the TEZ. Although the cruiser was well outside of the TEZ, it was declared an imminent threat to the British task force and was sunk by the British nuclear submarine HMS Conqueror (figure 4).

This action was controversial because the Argentinean cruiser was outside of the TEZ, on the opposite side of the Falklands from the British task force, and 368 Argentinean lives were lost at sea.52 On the same day, Woodward’s TG 317.8, via antisurface/subsurface helicopters, attacked two small Argentinean naval vessels, sinking one and permanently disabling the other.53 With the sinking of the General Belgrano and two other vessels neutralized, the task force had its needed effect.54 Argentinean leadership pulled back nearly all surface combatants, to include the Argentinean aircraft carrier ARA Veinticinco de Mayo (V 2). With one move, the British obtained maritime supremacy.55

Gain and Maintain Air Superiority: The Unattainable Goal

During the Falklands campaign, neither side maintained air supremacy, but considering that the British task force lost 10 percent of its shipping due to enemy air actions, it was the task force that paid the highest price. From the start, the Argentineans possessed a 1-to-4 advantage over British Harriers. The Argentineans chose to use their aircraft in a CAS/ DAS role, compared to the British task force’s choice to use its Harriers for DAS, CAS, and CAP, with the majority of aircraft tasked to defend the task force.56

Figure 4. Sinking of the ARA General Belgrano, 2 May 1982. Created by author, courtesy of History Division

Additionally, the RAF had the Avro Vulcan B.Mk 2A bomber. The Vulcan bomber, like much of the British military inventory, was a Cold War-era air-craft meant to conduct bombing missions from home bases in England and Europe; it did not have the range needed for deep strategic bombing. Regardless of this shortcoming, on 1 May, a Vulcan bomber at 10,000 feet attacked the Port Stanley airfield with 21 of its 1,000-pound bombs.57 Although Operation Black Buck had little effect and the Port Stanley airfield was operational shortly after the bombing, the “Vulcan Air Raid” was a strategic move for British forces. It proved that if worse came to worst, the RAF could strike targets on the Argentinean mainland.58 This may have been unlikely due to British political statements and diplomatic relations with allied nations and the United Nations, but the Vulcan bombing did prove the point. Finally, the Vulcan bombing gave yet another win to the British people back home, the first being South Georgia Island, and the next being the sinking of the General Belgrano. With three consecutive wins by the British, it was Argentina’s turn at the scoreboard.

Argentina Scores a Hit

The AM-39 Exocet was new to the Argentinean military and to the world. The year prior to the invasion, Argentineans fielded the French-built antiship cruise missile along with the aircraft to carry it, the Dassault Super Etendard. Originally, the Falklands invasion was to occur in the South Atlantic’s late winter/early spring. One reason for the later invasion date was the need to properly train crews and fit the Super Etendard for the Exocet. Unfortunately for the Argentine Naval Aviation Command (Comando de la Aviacion Naval Argentina), after the South Georgia incident General Galtieri advanced the invasion date by nearly six months without the Super Etendard crews and aircraft fully operational.59

By April, the 2d Naval Fighter and Attack Squadron possessed four operational Super Etendards and 10 trained pilots for that aircraft.60 Furthermore, Argentina possessed just five AM-39 Exocet air-to-surface antiship cruise missiles.61 The odds were not in favor of the Super Etendard pilots, but they just needed one missile to make an impact on the British task force. As is still true today, in 1982 the ultimate target for the Super Etendard pilots was always a task force aircraft carrier.62 Although striking, or better yet sinking, a British aircraft carrier could “win the war,” this was unlikely considering how few Exocets the Argentineans possessed. Considering the limited number of Super Etendards, any ship within the task force could be a potential target, not just aircraft carriers. On 4 May, after the Super Etendard squadron aborted two previous attempts, an Argentinean Super Etendard launched an AM-39 Exocet at the British task force. This was the first combat test for the Exocet, a textbook maneuver, and it went quite well.

The British destroyer HMS Sheffield (D 80) was hit and suffered significant damage with 24 wounded and 20 killed.63 If there was ever a time that diplomacy would have stopped the coming British assault, it had just passed. Strategically, all cards were on the table from this point forward, and the British were not backing down. Tactically, the attack showed that the task force was not impregnable, and that gaining air superiority was more vital than ever before.

During the next six weeks, the Argentine Air Force and naval fighter attack and bomber aircraft made runs at the task force and later on 3CDO with considerable success. The majority of attacks occurred from aircraft stationed within Argentina. British intelligence knew the Argentineans would attack from both the mainland and from the Falklands. Their two biggest concerns were the Exocet and the positioning of aircraft on the Falklands.

These were two separate problems with different solutions. First, for aircraft departing Argentina, the British assumed that Argentina did not have a reliable air-to-air refueling system. This was a mistake. By making this assumption, the task force discounted the amount of on-station time aircraft would have to loiter and attack a target or group of targets of choice. Initially CAPs defended around Woodward’s carrier group, and then later the limited number of Harriers was split between defending the carrier group, the amphibious task force, and the landing force. The Argentineans made their land-based runs on the ATF and LF, while the air-to-air refueled aircraft focused on the carrier group at sea. Consequently, the number of Harriers were lessened for the CAP, and the Argentineans exploited this weakness.

The second concern was the Argentinean aircraft positioned on the Falklands. This was dealt with by the use of Harriers and special operations. Most notable of these actions was the Special Air Service (SAS) raid on Pebble Island. Pebble Island, located on the northern edge of West Falkland, possessed a 1,600-foot-long grass airfield. Grass airfields were not uncommon on the Falkland Islands because they lacked a road network connecting the many villages. Also, considering that the islands are around 100 miles by 160 miles, traveling from settlement to settlement took a considerable amount of time by vehicle. Instead, the various villages possessed grass airstrips for postal services and delivery of supplies via small, privately owned aircraft.

Argentinean planners were well aware of the many grass airstrips available. The Argentine Air Force forward deployed light attack aircraft to Port Stanley, Goose Green, and Pebble Island. The British believed that, after runway improvements were conducted, Argentinean air elements would use Port Stanley and other airfields—specifically, that they would try to use Port Stanley for fast attack aircraft like the Skyhawks, Mirages, or (best case for the Argentineans) the Super Etendard.64 Although fast attack aircraft never deployed to the Falklands, light attack aircraft did.

Woodward’s Advance Amphibious Force Opens the Gate

Pebble Island was vital to the Argentineans for two reasons: 1) early warning radar coverage and 2) the positioning of troops and aircraft to protect their northern flank. TPS-44 and TPS-43 radar sets were positioned near the homes on the outskirts of Port Stanley.65 These positions were not ideal, but they were still effective for identifying the incoming British task force, both air and sea. The only downside was that Port Stanley is surrounded by mountains except in one direction, so radar coverage was only able to look east. The Argentineans needed to fill this gap in coverage.

Additionally, the Argentinean air force needed to spread its forces to cover East Falkland from the north, south, and east. To fill both gaps, Pebble Island (named Base Aérea Militar [BAM] Borbon) was the logical choice; it would provide a greater range of radar coverage and prevent a northern approach by the task force.66 For reasons unknown, during April and into May, the additional TPS-44 and TPS-43 radar sets available never made their way to BAM Borbon to fill in the radar gap. The establishment of the MEZ/TEZ may have prevented filling the gap, or perhaps a radar set was disabled in Port Stanley due to high winds and was replaced with the spare TPS set.67 Although a radar system never made its way to BAM Borbon, the aircraft and troops to protect it did. Positioned on Pebble Island were around 100 troops armed with small arms, antitank weapons, and 60mm and 81mm mortars.68 Just as important as the reinforced company on the island were the light attack aircraft. BAM Borbon maintained six Pucaras, four Turbo Mentors, and one Short SC.7 Skyvan 3M-400.69

Just like the Argentineans, British planners identified Pebble Island as a good choice for both radar and aircraft positioning. This was later confirmed in May when British ships and aircraft picked up Argentinean aircraft departing and landing in the vicinity of Pebble Island. Harriers were focused on bombing Port Stanley and Goose Green, while Vulcan raids focused on Port Stanley. The threat on Pebble Island was assigned to the SAS.

In a daring raid on the night of 15–16 May, 45 men from D Squadron SAS were inserted via Westland WS-61 Sea King helicopters from the HMS Hermes and supported by the HMS Broadsword (F 88) and Glamorgan (D 19). In the next five hours, from insert to extraction, the SAS element was able to destroy 11 aircraft, crater the airfield, and confirm that a radar station was not located on Pebble Island.70 This limited short-duration raid opened the gate for Clapp’s amphibious task force.

Landing Site Selection: The Best of Bad Options

The amphibious landing of 3CDO, Operation Sutton, was set for 21 May. Thompson and Clapp narrowed down the landing sites and beaches from 50 to a possible 3, and then finally selected San Carlos Water.71 Not a single landing site on East or West Falkland was ideal for an amphibious landing. Each landing site had its problems: either being too close to the enemy’s defensive positions, too narrow, too shallow, or too far away from the objective area. Although San Carlos Water had its drawbacks, it was the best landing site for fighting within the A2/AD bubble.

San Carlos Water is a bay that sits on the western side of East Falkland; its only access point is the Falkland Sound, which splits the two main islands. The task force would have to approach the island either from the north or from the south, thus closing some of the distance between the British ships and Argentinean aircraft stationed on the mainland. An approach into San Carlos Water via the sound would be slow regardless of a movement from the north or the south. Additionally, an approach from the north would push the ships into radar range of land-based radar units around Port Stanley. Although Pebble Island had been neutralized, the threat of an unidentified radar unit still existed, especially around the northeastern portion of East Falkland near the Argentinean defensive positions. Although there were drawbacks with movement toward and the location of the bay, the bay itself made up for them.

At San Carlos Water’s opening, ships have to pass through a gap no larger than 1.5 kilometers (km). Then the bay opens up to 3.5 km and then narrows down from there. Although San Carlos Water is an extremely tight fit for a group of ships, it has calm waters and multiple beaches. Surrounded by high hills and mountains, San Carlos Water is relatively ideal for the defense of a landing and amphibious task force. Having such high terrain surrounding the area negates the use of air-to-surface missiles (i.e., the Exocet) and forces attacking aircraft into a very short target identification-to-engagement timeline. San Carlos was not the ideal landing site, but it was the best one available to the amphibious task force.72

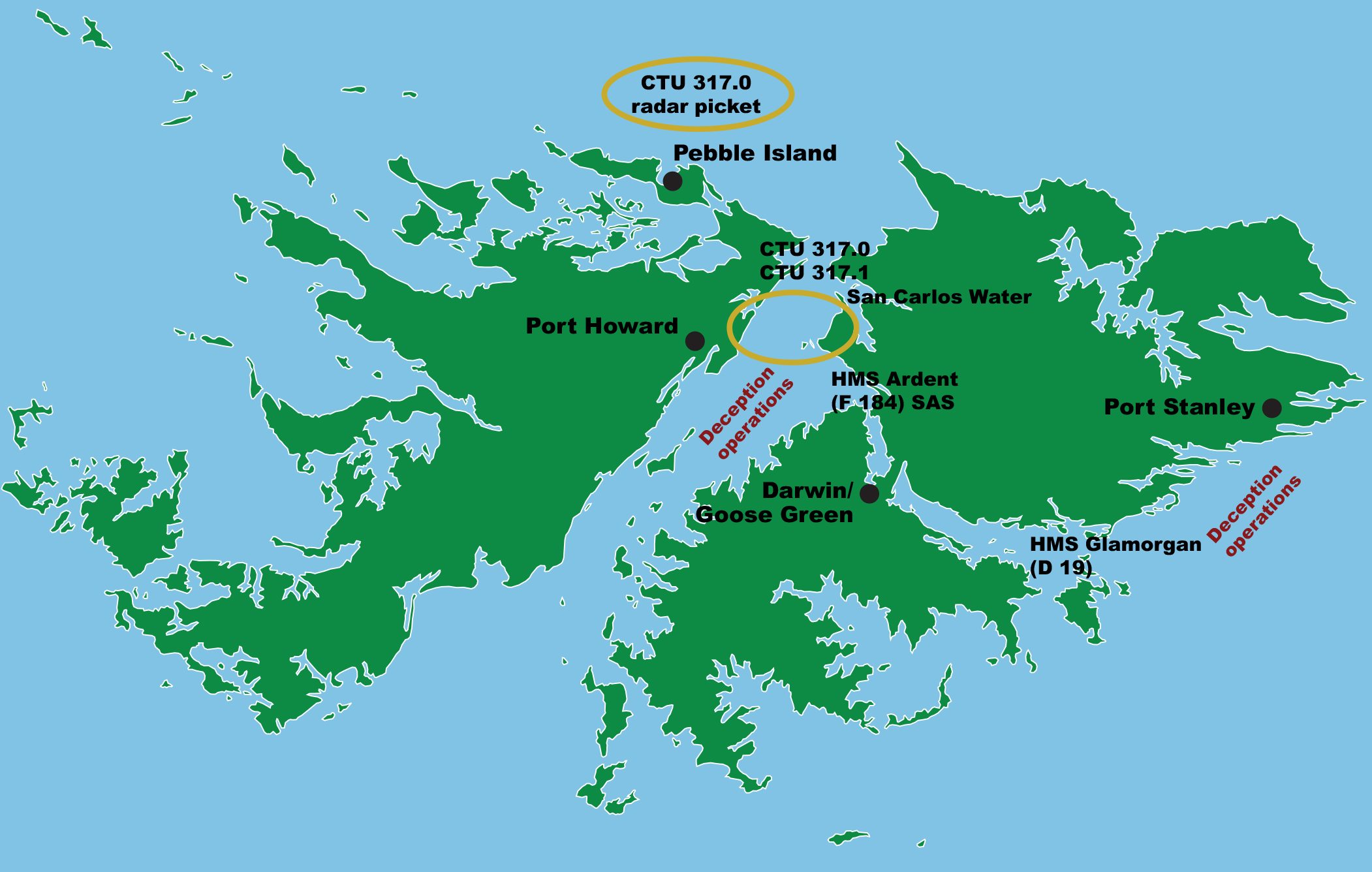

As the task force crept closer to the landing date, it was obvious that air superiority could not be obtained in time. The best Woodward could do was mitigate the threat through deception operations. Deception operations are a must in warfare, and Operation Corporate was no different (figure 5). Woodward and Clapp devised a deception plan, named Operation Tornado, to draw attention away from the San Carlos Water landing.

Figure 5. San Carlos Water deception operations, 21–27 May 1982. Created by author, courtesy of History Division

At 0400 Zulu time zone, the same time the actual landing at San Carlos Water commenced, the cruisers HMS Ardent (F 184) and Glamorgan positioned themselves off the coasts of Goose Green and Port Stanley, respectively.73 Under naval gunfire provided by the cruisers, SAS forces raided Goose Green. Off the coat of Port Stanley, the Glamorgan conducted radio transmissions simulating a coming invasion. Additionally, Special Boat Service (SBS) troops were inserted near the town and made contact with locals to spread the word that the task force was about to land. Operation Tornado, a seemingly small act, drew enough attention away from San Carlos Water and bought sufficient time for the task force to start its landing unimpeded.74

Deception operations, an early morning nautical twilight landing, and SBS securing the landing site prior to 3CDO’s landing enabled the initial waves to land unopposed. If there was a significant delay in their movement, or any other factor not in favor of the landing force, this could have turned Operation Sutton into an opposed landing.75 Through detailed planning, intelligence, and sheer will, Commodore Clapp was able to fit the majority of his amphibious task force in and around San Carlos Water by the early daylight hours of 21 May.76 Although the day started off without incident, it was only a matter of time before Argentina’s fixed-wing assets attacked the amphibious task force.

Defending the Landing Force: Fighting within the Bubble

Clapp and Thompson knew that the most dangerous spots for the landing force during an air attack would be on the ships in San Carlos Water or in transit to the shore. Getting the landing force ashore during the early hours of 21 May was paramount to mitigate the air threat’s potential. Additionally, the 3CDO’s defensive posture had to be set in the event that enemy forces counterattacked from Goose Green or Port Stanley, via the regimental air-assault reserve. With 3CDO’s battalions set, 40, 42, and 45 Commando with 2PARA and 3PARA, the chances of stopping or pushing the landing force back into the sea were slim.77 Although Argentinean ground forces could do little harm to the landing force at San Carlos Water, the Argentineans could strike hard at the landing force with their air components.

The amphibious task force and 3CDO were well inside the A2/AD bubble with aircraft attacking from the Argentinean mainland and Port Stanley. The coming days were referred to as “Bomb Alley” for the amount of ordnance delivered from Argentinean aircraft.78 From 21 to 25 May, the Argentine Air Force and Navy produced 180 sorties with about 80 operational fast attack aircraft.79 Out of the 180 sorties, 117 sorties reached their targets, with 19 Argentinean aircraft being destroyed, a loss rate of 1 in 4. Compare this to the British task force, which with 33 Harriers produced 300 sorties, about 2 sorties per day per Harrier.80 Of the 33 Harriers, 4 were operational losses due to surface-to-air antiaircraft fire, a loss rate of 1 in 8.81 Although sortie generation and sustainment of aircraft were higher for the Harriers, their part in the defense of the ATF could only do so much. Defense of the ATF also fell upon the ships within the ATF, the antiair battery, and man-portable air-defense systems (MANPADS) within 3CDO.

Although the high surrounding terrain mitigated the air-to-surface threat, it also hampered the ATF’s surface-to-air weapon systems. Some of the ships within the ATF had the latest antiair missile systems. Due to the hills and bluffs surrounding San Carlos Water, those systems were unable to acquire, identify, and prosecute targets in an effective manner. By choosing this terrain, the ATF took a risk in being unable to use their antiair missile systems.

Meant to aid in antiair defense, 3CDO had two Rapier antiaircraft batteries attached. These units were neither organic to the landing force, nor were they systems/units 3CDO was accustomed to operating within training. Unfamiliarity and misuse of the weapon system led to its ineffective use during Bomb Alley and follow-on-point defenses during the campaign.

The first problem occurred during embarkation. The Rapier systems were organic to the RAF and Army and not meant for travel via amphibious ships, where exposure to saltwater and rough seas are common. To protect the sensitive components to the missile systems, they were placed below deck, well away from sea exposure; however, these components were never reorganized for immediate debarkation as the ATF closed on San Carlos Water. Considering the air threat, these items should have been in wave two or three, rather than some of the last waves on the afternoon of 21 May. As a result, the Rapier systems were out of commission for most of 21 May.82

The second problem with the Rapier was its misuse around San Carlos Water. The Rapier was intended for a point defense (e.g., a bridge, headquarters, or a small sensitive site). San Carlos Water was an area defense spread out over nearly 60 square miles. Instead of preparing to engage aircraft aimed at one small area, the task force ineffectively employed the Rapier to engage aircraft attacking multiple areas, flying low and fast, and spread over a large surface. Compounding this problem, the Rapier was extremely difficult to move, requiring helicopter support to lift each system and reset or reposition it. Even after 21 May, systems were continuously reset by Sea King helicopters. Logistically, the Rapier was a burden. For each day of use during the ground campaign, the Rapier air-defense battery required 1 Sea King helicopter out of the 11 dedicated to 3CDO to refuel and conduct maintenance on the systems.83 This taxed 3CDO’s helicopter support, exposed these helicopters to aircraft attacks, and again, meant that Rapier systems were out of commission during the resetting.84 Additionally, the key radar for the system was left in the UK, so each system had to rely on sight to identify an incoming target, rather than having radar warning and preparing to engage once the enemy aircraft was in range of one of the systems.85

The only air defense weapons organic and attached to 3CDO were the Blowpipe MANPADS provided by 3CDO Air Defense Troop and 43 Battery, 32d Guided Weapons Regiment (Royal Army). The Blowpipe was a 42-pound, shoulder-fired antiaircraft missile with a range of 1.5 nautical miles. Out of 95 missiles fired during the ground assault, nearly one- half malfunctioned, and only 1 shot down an enemy aircraft.86 For the time, the Blowpipe was the best 3CDO had for its own internal defense against the low, fast-flying Argentinean aircraft.

The Cost of Amphibious Operations in the A2/AD Environment

Separate from Clapp’s ATF, on 25 May the container ship SS Atlantic Conveyor was struck by an Exocet. As with every attack upon Woodward’s TG 317.8, the intended target was an aircraft carrier, either HMS Invincible (R 05) or Hermes. Soon after the missile strike, the Atlantic Conveyor sank, and with it not only supplies for 3CDO, but more importantly, 3CDO’s heavy-lift helicopters. With the loss of four Boeing CH-47 Chinooks, 3CDO was forced to make its movement across the Falklands by foot.87 Although not directly part of the ATF, the Atlantic Conveyor’s sinking proved how complex and interconnected the A2/AD environment is for both the attacker and defender.

By the end of Bomb Alley, Clapp’s ATF suffered damage to six ships and lost three.88 Considering Clapp’s TU-317.0 consisted of 20 ships, 45 percent of his ATF suffered from attacks within San Carlos Bay. Due to ordnance malfunctions and survivability of the ships, those damaged continued to fight. Clapp’s ATF lost 15 percent of its fleet. Thompson’s landing force suffered fewer casualties due to its twilight landing and digging-in around the areas surrounding San Carlos Bay. Operation Sutton ended with the movement of 3CDO to its objectives at Port Stanley and Goose Green. Essentially, 3CDO fought within the A2/AD bubble and successfully fought out of it. Although 3CDO made its movement toward its objectives in- land and Argentinean air had been significantly reduced, the A2/AD fight was not over.

During the next two weeks, attacks occurred against British naval and ground forces, although they were not as intense as Bomb Alley had been. The next and most significant of all air attacks in terms of lives lost was against the RFA Sir Tristram and Sir Galahad at Fitzroy. During the off-load of 5th Infantry Brigade units on the early afternoon of 8 June, two Mirages and two Skyhawks attacked in broad daylight.89 Although the beach at Fitzroy was undefended, the Argentineans held Mount Harriet 10 miles due east with a clear view of the landing site.90 In this attack, the British lost 2 men on the Sir Tristram and 48 killed and 57 wounded on board the Sir Galahad.91 Once again, neither the Rapiers, which were in the process of being emplaced, nor the CAP over the landing force were able to prevent this attack.

Additionally, on 8 June, LCU “Foxtrot-4” from the HMS Fearless (L 10) was sunk while in Choiseul Sound near Goose Green, resulting in the loss of six crew members. Although minor, it proves that any target, regardless of size and task, is considered a threat to a defending force. Sections of Daggers and Skyhawks attacked the HMS Plymouth (F 126), positioned north of Falkland Sound within the radar picket for TU 317.0, resulting in five wounded and the ship suffering limited damage. Due to the overtaxing of Argentinean aircraft, weather, and a change to conducting night attacks by British ground forces, 8 June was the end of air attacks, but threats still remained to the task force.

In the early hours of 11 June, a land-based MM-38 Exocet struck the HMS Glamorgan. At the time, the Glamorgan was providing fire support to 45 Commando in the attack of Mount Harriet and Two Sisters.92 As the sun rose, the Glamorgan stayed on station for as long as possible, supporting the commandos before turning seaward. With the Glamorgan crossing in front of the modified trailer-mounted MM-38’s line of sight, this sea surface-to-surface Exocet launched and detonated above the stern of the ship.93 The Glamorgan suffered severe damage with 13 killed, but continued to fight a few days later on 13–14 June, just in time to see the end of the war.94

The Falklands campaign came to an end on 14 June 1982, with all objectives secured by ground forces and the subsequent Argentinean surrender. The recapture of the islands came at a very high price. For TF 317, it suffered a total of 253 killed in action; of those, 131 were killed on ship or at sea.95 British ground forces suffered 80 killed in action and 269 wounded in action.96 3CDO being reinforced by 5th Infantry Brigade helped in many ways, but what enabled the lower killed-in-action list was the medical team placed at Ajax Bay in San Carlos Water. “The Big Green Machine,” as it was termed by the hospital staff, was able to keep alive every single British casualty that it received.97 This was a time before the “one hour golden rule,” and it proved how effective self-aid and buddy-aid can be in such a conflict. Additionally, this was a phenomenal feat considering the field hospital was located in Bomb Alley.98

Conclusion: The Falklands War as a Blueprint for Today’s Amphibious Force

According to the recently published Marine Corps Operating Concept, the key drivers of change influencing the future operating environment are complex terrain, technology proliferation, information as a weapon, battle signatures, and an increasingly contested maritime domain.99 Excluding information as a weapon, the 1982 Falklands War offers potential solutions or starting points in minimizing the effects of these key drivers.100 Technology has significantly improved during the past three decades not only for the United States but also its adversaries. The same can be said for the opposing forces in 1982. Each side had strengths and weaknesses, but the consensus going in was that it would not be a costly war due to the slight technological advances held by British forces and their overall better conditioning. Argentina was grossly underestimated and proved to be a near peer competitor to the United Kingdom.

British forces held a slight technological edge very similar to that held by the United States today. Many of our foes already have or will have near peer capabilities that counter our offensive and defensive capabilities. Additionally, the Falklands campaign provides an example of a force comparable in size to today’s Marine Corps ESG/MEB. Some, if not all, of the problems seen by the British task force will be seen by our ESG/MEBs in future conflicts.

There is never a perfect solution to any problem, especially one involving military operations. The fog of war combined with political end states will cause unforeseen consequences to any plan. The 1982 Falklands War is—more than any other—as close to a perfect campaign as possible to study amphibious operations in the A2/AD environment.

It is not beyond belief that the United States could end up in a Falklands-type situation. In the future, the United States could enter into a high-intensity conflict that takes the ESG/MEB into an area where there are few allies and increasing logistical burdens. China, Russia, and Iran supply U.S. adversaries with technologies that will test our forces to their limits. These technological advances in A2/AD, coupled with an amphibious task force that lacks allies and safe havens, will sound all-too similar to the 1982 Falklands War.

The U.S. military’s focus today, just as it was for Britain in 1982, is preparing for the most dangerous course of action. Preparing for the most dangerous course of action is a requirement that cannot be over-looked. However, thinking that the A2/AD environment only exists around China and Russia creates a false sense of security. While China and Russia do pose a threat to U.S. interests, a war with either of them is not the most likely course of action in the near term. The United States will continue to face conflicts in the arc of instability with adversaries that pose formidable A2/AD threats to smaller units such as an ESG/ MEB and ARG/MEU. Despite advancements in today’s A2/AD weapons technology, the 1982 Falklands war offers critical insights to how U.S. naval forces can counter modern-day threats to an amphibious force and prepare for future threats.

•1775•

Endnotes

- Maj Brandon H. Turner is an infantry officer and a graduate of the Marine Corps Command and Staff College and the School of Advanced Warfighting. He is currently assigned to U.S. Marine Corps Forces Special Operations Command.

- John O’Sullivan, The President, the Pope, and the Prime Minister: Three Who Changed the World (Washington, DC: Regnery, 2008), 144–47; and Sir Lawrence Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, vol. 2, War and Diplomacy (London: Rout- ledge, 2005), 3, 15.

- The Falklands invasion was nearly two centuries in the making. The Malvinas, as the Falklands are called by Argentina, were once claimed by not only Britain but also France, Spain, and Argentina. It was not until 1833 that ownership was solidified by Great Britain. During the 1970s, the Falklands were used in a diplomatic game: being held by Great Britain while at the same time being “offered” to Argentina. As diplomacy faltered, Argentina developed plans to seize the islands between July and October 1982; this window was manpower-,equipment-,and weather-dependent. In late March 1982, scrap metal workers on South Georgia Island raised an Argentinean flag over their work site. This move prompted Great Britain to send the HMS Endurance (1967) with 22 Royal Marines to South Georgia to remove the flag and observe the workers. Using the South Georgia incident as cause to regain Argentinean honor, Argentina advanced its invasion timeline for the Malvinas. The UK received various signals an invasion was underway, but little could be done from 8,000 miles away to stop the invasion.

- Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 80–84.

- Adm Sandy Woodward, RN, with Patrick Robinson, One Hundred Days: The Memoirs of the Falklands Battle Group Commander (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1997), 201–3.

- Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 5–11.

- Max Hastings and Simon Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands (New York: W. W. Norton, 1984), 45–49.

- Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 4–11. The Royal Marines assigned to the Falkland Islands were there to protect the governor, provide assistance to the local population, and maintain a limited defense of the Falklands and its territories. In total, there were 69 Royal Marines. A former Royal Marine who was living in the Falklands reenlisted upon hearing of the coming invasion. Additionally, the HMS Endurance had 11 Royal Navy sailors, and the islands were able to provide 23 men from the Falkland Island Defence Force (FIDF).

- “During April C-130 Hercules transports of Air Force, Electras and Fokker Fellowships of the Navy, Fokker Friendship and Fellowship airliners of the semi-military airline LADE, and Skyvan light transports of the Coast Guard, flew in more than 9,000 service and civilian personnel and 5,000 tons of equipment and supplies.” Jeffrey Ethell and Alfred Price, Air War South Atlantic (New York: Berkley Publishing Group, 1983), 30.

- Martin Middlebrook, The Fight for the Malvinas: The Argentine Forces in the Falklands War (London: Viking Adult, 1989), 56–60. Argentine Army artillery units are organized into groups or grupos, with three batteries per group. As stated by Middlebrook, the Argentine Army did not have artillery regiments. A group is the equivalent of a battalion.

- Middlebrook, The Fight for the Malvinas, 60–61. The large majority of antiaircraft weapon systems were centered around Port Stanley, with two 35mm Oerlikon each placed at Goose Green and Moodybrook.

- Ethell and Price, Air War South Atlantic, 31.

- Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 75.

- David Brown, The Royal Navy and the Falklands War (New York: Pen and Sword, 1987), 371–74. Argentina conducted its amphibious landing with 31 total ships: one aircraft carrier, one cruiser, six destroyers, three submarines, three corvettes, five patrol crafts, one landing ship, tank (LST), one oiler, four naval and crafts, one landing ship, tank (LST), one oiler, four naval and three merchant transports, and three “spy” trawlers.

- Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 75.

- Ethell and Price, Air War South Atlantic, 26; and Christopher Chant, Air War in the Falklands, 1982 (Oxford: Osprey, 2001), 19–22. After Argentina bought IAI Neshers from Israel in the late 1970s, Argentina renamed the Nesher the Dagger.

- Ethell and Price, Air War South Atlantic, 26.

- Ethell and Price, Air War South Atlantic, 26. In total, Argentina possessed 247 fixed-wing aircraft, but only about 130 were able to offer support due to maintenance readiness or not operational due to lack of parts or qualified pilots and ground crews.

- Hastings and Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands, 67; Michael Clapp, Amphibious Assault, Falklands: The Battle of San Carlos Water (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1996), 35; and Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 3, 11–14, 54–55. It was no surprise to the British that Argentina wanted to claim or reclaim the Falkland Islands. The British were not only ambivalent to the Falklands but also were very much focused on domestic issues and the Cold War in 1982. Indications and warnings of pending aggression were first realized in mid March 1982. Even though small indications existed, it was never believed that an invasion would actually occur. Although small planning meetings were held, nothing substantial was ever produced to acquire manpower, ships, heavy equipment, and gear. On 31 March 1982, Adm Sir Henry Leach told the prime minister that he could mobilize a task force by the weekend. With this proclamation and approval by the prime minister, the Royal Navy and Royal Marines had their orders. The only units available to respond to the Argentinean invasion were the Royal Marines stationed on the Falklands, the Antarctic patrol vessel HMS Endurance, and two nuclear powered submarines (SSNs) located within the south Atlantic. The HMS Endurance, underway at the time, could do little after supporting operations on South Georgia Island, so the ship turned north for Ascension Island and away from the Argentinean navy and air power. The two SSNs were given the order to move south and observe the area until given further instructions.

- Clapp, Amphibious Assault, Falklands, 35.

- O’Sullivan, The President, the Pope, and the Prime Minister, 144–47.

- Hastings and Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands, 78.

- Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 29–31.

- Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 29; and O’Sullivan, The President, the Pope, and the Prime Minister, 148.

- Amphibious Operations, Joint Publication (JP) 3-02 (Washington, DC: Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2014), I-7.

- Joint Operations, JP 3-0 (Washington, DC: Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2017), V-13. Joint Phasing Model: Phase 0-Shape, Phase I-Deter, Phase II-Seize the Initiative, Phase III-Dominate, Phase IV-Stabilize, and Phase V-Enable Civil Authority.

- Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 15–20; and Joint Forcible Entry, JP 3-18 (Washington, DC: Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2012), I-5–I-6. EMPRA is nonstandard doctrine for Marine Expeditionary Units (MEUs) taught by the Expeditionary Warfare School and Expeditionary Warfare Training Groups Atlantic and Pacific. During the past 30-plus years, MEUs have been forced to embark at a moment’s notice with little warning. Under such circumstances, planning must be conducted while underway to the objective area and well after embarkation has been completed.

- Joint Forcible Entry, I-5–I-6.

- Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 54–55.

- Julian Thompson, 3 Commando Brigade in The Falklands: No Picnic (London: Pen and Sword, 2009), 1–16, 27.

- Julian Thompson, The Lifeblood of War: Logistics in Armed Conflict (London: Brassey’s, 1991), 284. 3CDO reinforced stood at 5,500 troops, plus or minus. Later during the land campaign, 5th Infantry Brigade joined 3CDO, bringing the total landing force to approximately 9,000 troops. For the purposes of this article, the focus is closing the force (3CDO) in San Carlos Water at the height of fighting within the A2/AD bubble.

- Hastings and Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands, 62–62, 83–84; and Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 29.

- Ratio of Royal Navy “warships” to support ships from the RFA and STUFT: 40 : 60.

- Brown, The Royal Navy and the Falklands War, 358–62.

- Brown, The Royal Navy and the Falklands War, 365–70.

- Chant, Air War in the Falklands, 1982, 17–18; and Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 773.

- Ethell and Price, Air War South Atlantic, 233.

- Ethell and Price, Air War South Atlantic, 233.

- Kenneth L. Privratsky, Logistics in the Falklands War: A Case Study in Expeditionary Warfare (London: Pen and Sword, 2015), 40–42.

- Privratsky, Logistics in the Falklands War, 76–77.

- Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 54.

- Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 88; and Brown, The Royal Navy and the Falklands War, 84. The zone was “defined as a circle of 200 nautical miles from latitude 51° 41' South and longitude 59° 39' West, approximately the center of the [Falkland] Islands.” Freedman, The Official History of the Falk- lands Campaign, 88. The first forces to arrive at the MEZ around the Falklands were three of the Royal Navy’s nuclear submarines, HMS Spartan (S 105), Splendid (S 106), and Conqueror (S 48).

- Brown, The Royal Navy and the Falklands War, 84–85. Sea mines were seen being placed within Cape Pembroke, and 105mm howitzers were placed near the shores to prevent naval fires and an amphibious landing.

- Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 203.

- Clapp, Amphibious Assault, Falklands, 86.

- Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 210–11.

- Brown, The Royal Navy and the Falklands War, 107–12.

- Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 203.

- Martin Middlebrook, The Falklands War (London: Pen and Sword Military, 2012), 113.

- Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 89–91.

- Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 220–21.

- Hastings and Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands, 146–50.

- Adrian English and Anthony Watts, Battle for the Falklands (2): Naval Forces (Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 1982), 22.

- Middlebrook, The Falklands War, 150–53.

- English and Watts, Battle for the Falklands (2) Naval Forces, 21–22.

- Chant, Air War in the Falklands, 1982, 86. There were two types of Harriers used in the 1982 Falklands War: the Sea Harrier and the GR Mk.3 Harrier. The Sea Harrier was flown by the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm Squadrons 800, 801, and 809. The Sea Harrier was both air-to-air and air-to-ground capable. The Fleet Air Arm provided the majority of Harriers to the task force. Adding to the total number of Harriers were those provided by the Royal Air Force Squadron Number 1 who flew the GR Mk.3 in an air-to-ground role for both CAS and DAS.

- Chant, Air War in the Falklands, 1982, 40–41.

- Gregory Fremont-Barnes, A Companion to the Falklands War (Gloucestershire: History Press, 2017), 48–51. Operation Black Buck 1 was followed up with Harrier bombing runs on the airfield and six more Vulcan bombings (Black Buck operations 2–7).

- Middlebrook, The Falklands War, 36; and Chant, Air War in the Falklands, 1982, 51.

- Ethell and Price, Air War South Atlantic, 26–29, 41; and Chant, Air War in the Falklands, 1982, 53.

- Chant, Air War in the Falklands, 1982, 55–56. Although Argen

- Chant, Air War in the Falklands, 1982, 51–56.

- English and Watts, Battle for the Falklands, 23.

- Ethell and Price, Air War South Atlantic, 2. The Argentine Air Force never used Stanley for fast attack aircraft for two reasons. First, the airfield was too short in a wet environment. The Falklands receives high winds and rain quite often, and the wet airstrip could not support fast flying aircraft. Second, the Argentineans had considered extending the airfield. The British knew Argentinean engineers had the matting for this extension. Argentine Air Force planners chose not to extend the airfield because Stanley did not have the facilities, both hangars and fuel storage, for their fast attack aircraft.

- Ethell and Price, Air War South Atlantic, 30–31.

- Pebble Island was known to the Argentineans as Isle Borbon. Thus, the name for the Pebble Island forward airfield was BAM Borbon.

- Ethell and Price, Air War South Atlantic, 31, 50, 221–22.

- Francis MacKay with Jon Cooksey, Pebble Island: The Falklands War 1982 (South Yorkshire, UK: Pen and Sword Military, 2007), 40, 47.

- MacKay and Cooksey, Pebble Island, 84.

- Middlebrook, The Falklands War, 84, 190–91. HMS Broadsword was assigned as the antiair defense ship for HMS Hermes. HMS Glamorgan was to provide fire support to the SAS during their raid on Pebble Island. Glamorgan went within seven miles of Peb- ble Island. Varying accounts exist concerning how many aircraft were destroyed. Some accounts state 11 and others state 10. Due to a hard landing, one Pucara was down for maintenance. Thus, the British did destroy 11 aircraft, though 1 was already disabled.

- Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 201–2.

- Woodward, One Hundred Days, 189.

- Middlebrook, The Falklands War, 208; and Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 467–69. Zulu time, or Universal Time Coordinated (UTC), refers to the time at the prime meridian and is primarily used in military and civil aviation.

- Woodward, One Hundred Days, 244–45; and Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 469.

- Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 470. The landing was delayed by one hour due to a malfunction in the satellite navigation system for the HMS Fearless, but this was a minor issue, as stated by Thompson.

- Clapp, Amphibious Assault, Falklands, 132–43.

- Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 463–74.

- Fremont-Barnes, A Companion to the Falklands War, 58.

- Ethell and Price, Air War South Atlantic, 152–56, 234–36. One- hundred eighty sorties were flown by Skyhawks, Daggers, and Super Etendards; operational aircraft at the start of the conflict were 6 Canberras, 11 Mirages, 46 air force Skyhawks and 11 navy Skyhawks, and 34 Daggers. Argentina lost some aircraft by 21 May, but these losses were minimal.

- Ethell and Price, Air War South Atlantic, 152–56.

- Ethell and Price, Air War South Atlantic, 248–51.

- Fremont-Barnes, A Companion to the Falklands War, 204–6; and Privratsky, Logistics in the Falklands War, 75.

- Thompson, 3 Commando Brigade in the Falklands, 88.

- Thomspon, 3 Commando Brigade in the Falklands, 68–70.

- “The DN181 Blindfire radar trackers were left in the UK, obliging the crews to depend on the organic surveillance systems or in many cases to resort to optical tracking.” Fremont-Barnes, A Companion to the Falklands War, 204.

- Fremont-Barnes, A Companion to the Falklands War, 52.

- Julian Thompson, “Reflections on the Falklands War: Com- mander, Amphibious Task Force–Commander, Landing Force” (lecture, U.S. Marine Corps University Expeditionary Warfare School, Quantico, VA, 28 March 2017).

- Fremont-Barnes, A Companion to the Falklands War, 58–59; and Clapp, Amphibious Assault, Falklands, 172. HMS ships damaged: Broadsword (F 88), Argonaut (F 56), Antrim (D 18), RFA Sir Lancelot (L 3029), RFA Sir Tristram (L 3505), and RFA Sir Galahad (1966). Ships sunk: Ardent (F 184), Antelope (F 170), and Coventry (D 118).

- Hastings and Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands, 279–84.

- Middlebrook, The Falklands War, 304.

- English and Watts, Battle for the Falklands, 30.

- Thompson, 3 Commando Brigade in the Falklands, 160–62; and Fremont-Barnes, A Companion to the Falklands War, 106.

- Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 550. The MM-38 was delivered via air transport into Stanley Airport during Operation Corporate. Although the airstrip had been at- tacked by Vulcan bombers and Harriers, the airstrip stayed open to most transport aircraft, one of those being an aircraft that delivered MM-38s to the Argentinean battlefield. Indirectly, it was the inability of the British task force to gain air supremacy that led to this successful attack.

- Clapp, Amphibious Assault, Falklands, 263; and Fremont-Barnes, A Companion to the Falklands War, 106. The HMS Glamorgan survived this Exocet attack; it was the only ship to suffer an Exocet strike and survive. Despite the damage from the Exocet, the Glamorgan would provide future fire support to the Scots Guards in their attack on Mount Tumbledown, 13–14 June.

- Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 781.

- Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 782–83.

- Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 615–17.

- Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 616, 782, 783. Not classified as wounded in action but rather injured in action were a total of 147 paratroopers and commandos; the majority of those injuries were cold weather injuries (i.e., hypothermia, trench foot, or frostbite). Typically, U.S. and British forces aim to have an injured person at a Role III medical facility within one hour of the injury to save life and/or limb.

- Marine Corps Operating Concept: How an Expeditionary Force Operates in the 21st Century (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, 2016), 5.

- Information operations (IO), as with most twentieth-century warfare, was present in the 1982 Falklands War, but was contained to limited press releases and statements at the United Nations. IO was held at the strategic level and its effects on operations were minimal during the campaign.