PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

A handful of Marines played a mostly forgotten but nevertheless pivotal role in one of Ernest Hemingway’s legendary exploits. They helped him conceive and run something he called “Operation Friendless,” which was a quixotic search for German submarines in the Caribbean during World War II. Without the Marines, the writer and his crew might never have been put to sea as U.S. Navy auxiliaries in 1942. The story goes back to June 1941 when Hemingway and his third wife, Martha Gellhorn, found themselves in a meeting with Lieutenant Colonel John W. Thomason Jr. at “Main Navy” in Washington, DC, one of the many plain concrete temporary structures, or “tempos,” erected during World War I that had taken over the National Mall between the far more elegant Lincoln and Washington Memorials.2 The tempos had little to offer apart from shelter and rudimentary offices that were hard to heat in the winter and impossible to cool in the summer.

Thomason had a reputation for being impeccable in his uniform. On this day, he most likely wore a set of summer service alphas, complete with field scarf and form-fitting blouse. His short, dark brown hair was parted in the middle, a slight eccentricity that distinguished him from other Marine officers of the day. Hemingway already knew that he had much in common with the Marine from Texas, who was only six years older.

Thomason was a fellow World War I veteran, a hero of the grim fighting in the trenches in 1918 who wore the Navy Cross for capturing an enemy machine gun nest, neutralizing two heavy guns, and killing 13 Germans along the way.3 While serving in the trenches, he began to sketch and to channel his experiences into art, becoming an accomplished artist and writer—as well as a heavy drinker, even by the Marine standards of the day. His sea stories, especially those collected in his first book, Fix Bayonets!, would soon become cult pieces for generations of Marines. Hemingway and Thomason had even traveled to many of the same places (Thomason spent two years in Cuba), and they knew many of the same people. Maxwell Perkins, the redoubtable editor at Charles Scribner’s Sons, worked with both writers. The stiff-looking New Yorker, who almost always wore a coat and tie, even to go deep-sea fishing, was, however, blessed with the ability to bond with his charges and connect them with each other. Another mutual friend was the swashbuckling soldier of fortune Charles Sweeny, whom Hemingway had first met in Europe in the 1920s and later described as “a very old pal and soldier in various armies, Venezuelan, against [President Cipriano] Castro, Mexican, with [President Francisco] Madero, Foreign Legion, U.S., Moroccan, R.A.F.” It was Sweeny who took the Hemingways to meet Thomason on that summer day in 1941.4

John A. Thomason Jr. as a major in the late 1930s. While assigned to the Office of Naval Intelligence, Thomason played a key role in facilitating Hemingway’s war work. Official U.S. Navy Photo, Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division

Detailed to the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI), where his principal duty was to run the Latin America Desk, Thomason was still eager to hear what Hemingway and Gellhorn had to say about their recent trip to China, where the couple had gone to report on the Second Sino-Japanese War. That conflict had been going on for so long that many Americans could not remember when and why it had started, but it was an important precursor to World War II. The couple travelled widely in the war zone, speaking to the British in Hong Kong and both Chinese nationalists and Chinese Communists on the mainland. The resulting information was solid and useful, just the kind of background information that ONI wanted. After the meeting, Hemingway and Gellhorn returned to Finca Vigia, the home they were making for themselves on a hill a few miles outside Havana, Cuba. The visit to Washington set the stage for a good relationship between Thomason and Hemingway. The Marine reported to Perkins that he was happy to meet “the very sensible and decent Hemingway” and hoped to see more of him.5 For his part, Hemingway would later write that he quickly came to believe that Thomason possessed one of “the most intelligent minds I have ever talked to.”6

A few months later, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor finally propelled the United States into World War II, Hemingway remembered Thomason as he cast about for ways to make himself useful to his country. He wanted to fight at sea from his Brooklyn-built cabin cruiser, Pilar, which he had lovingly outfitted for deep-sea fishing. It was, one crewman remembered, “beautiful . . . with a black hull, a green roof, and varnished mahogany in the big cockpit and along the sides.”7 The writer’s vision was to use Pilar to patrol the north coast of Cuba in search of German submarines, which were preying on shipping off the East Coast of the United States and in the Caribbean and finding it blissfully easy to sink, since the United States had not been well prepared for the war at sea. One of the Germans’ happy hunting grounds ran between the Florida Keys and the northern coast of Cuba—home waters for Hemingway.

Hemingway’s concept was in line with other U.S. Navy initiatives, which amounted to mobilizing civilian boat owners and asking them to keep a lookout for the enemy as they went about their business.8 The civilians were to report any sightings by radio, and the Navy would take it from there. The unofficial name for the civilian auxiliaries was the Hooligan Navy, many of whose members searched for the Germans for hours, days, and even weeks on end, working hard, if not always effectively. But Hemingway wanted to do more than find the enemy. The refinement on the basic plan that he proposed put him in a class by himself. After sighting and reporting the contact, he wanted to lure the U-boat alongside and then sink it.

His assumption was that the Germans would see a fishing boat going about its business and approach to buy or seize fresh water and fish. Once the (hopefully unsuspecting) Germans were close, the crew of the Pilar would let loose with fragmentation grenades—pull the pin, wait a few seconds while smoke spurted from the top, and then toss—along with Thompson submachine guns, the heavy .45-caliber weapon favored by American gangster John Dillinger. They would even use a satchel charge with rope handles that was the size of a small footlocker. The Basque jai alai players who would crew for Hemingway and were so adept at throwing fast-moving balls would, at least in theory, be able to lob the hand grenades down the open hatches of the submarine, while other crewmen manhandled the explosive charge.9 If even one grenade, let alone the satchel charge, found its mark the result could be devastating.

The problem was that Pilar and the average long-range U-boat were so mismatched. Pilar measured 38 feet long and weighed less than five tons. Her prey could be up to 250 feet long and weigh something like 750 tons. One was made of wood, built for pleasure and style in 1934, while the other was a state-of-the-art warship recently built out of German steel. One boasted handheld weapons, the other a 9.5cm or 10cm deck gun and sometimes two powerful 20mm antiaircraft machine guns mounted on the back of the conning tower (to say nothing of its primary weapon, torpedoes, which no German skipper would have wasted on a wooden cabin cruiser). Pilar would have a crew of 6–10 of Hemingway’s sporting friends. They would prove themselves to be dedicated, hard working, and loyal, but they were never more than gifted amateurs. The average U-boat crew, however, comprised about 50 well-trained officers and men.

Hemingway’s boat, Pilar. The cabin cruiser was customized for deep-sea fishing in 1934 and outfitted for antisubmarine patrols in 1942. Ernest Hemingway Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

The writer knew that to realize his vision he would need official help from a kindred spirit such as Thomason.10 By now, Thomason was traveling in Latin America for ONI, and in mid-1942 the American embassy summoned him to Havana for consultations. He showed up suitably attired for a meeting at the chancery, which was then housed in a turn-of-the-century mansion on the fringes of Old Havana. Along with his World War I ribbons, Thomason sported a nonregulation black silk ribbon for his eyeglasses. The American ambassador to Cuba, Spruille Braden, presided while Hemingway outlined his concept of operations. He evoked the World War I precedent set by Q-boats, well-armed raiders masquerading as unarmed merchantmen, while Thomason twirled his eyeglasses and drained at least two tumblers of some kind of drink. The Marine knew the likely outcome of Hemingway’s plan was death with honor. He pronounced it not impossible, “only crazy.”11 It would take only one round from the U-boat’s deck gun to turn Pilar and its crew into a memory. But there was also a chance, however slim, of an unimaginably glorious victory. If Hemingway somehow pulled it off, it would be a tremendous boost to morale, something that the United States desperately needed at the time as it struggled to build up the strength to take on the Japanese in the Pacific and defend itself from U-boats in home waters.

Ambassador Braden liked Hemingway and his irregular approach to fighting the Germans. Though the proposal went “against all regulations,” the envoy gave his assent to what Hemingway named Operation Friendless after one of his many cats.12 As the Cuban government was unlikely to turn a blind eye to an armed privateer in home waters, and since Pilar’s identity and mission were meant to come as a surprise to the enemy, this operation would be secret. This was acceptable to Hemingway, a man who enjoyed wearing the mantle of secrecy and the insider advantage that it conferred.

Thomason arranged for Hemingway to work through the naval attaché at the embassy in Havana, a Marine colonel named Hayne D. Boyden, who, not unlike Thomason, was an original. Boyden was a tall, thin man with a pointed nose, which gave him a birdlike aspect and probably explained his nickname or call sign rendered by Hemingway as “Cucu” or “Cuckoo.” Boyden’s record suggests that he was a devil-may-care pilot from the early days of Marine Corps aviation who took risks every time he got into the cockpit. In the early 1920s, he flew aircraft like the de Havilland DH-4B two-seater over Hispaniola. The DH-4B was a slightly improved British leftover from World War I whose original design flaws had earned it the nickname “Flying Coffin.”13 In 1927, Boyden earned the Distinguished Flying Cross for singlehandedly providing close air support to a besieged and outnumbered Marine detachment in Nicaragua. A note in the December 1933 issue of Leatherneck concluded that Boy- den was “one of the most interesting personalities in Marine Aviation.”

He has spent a great part of his time in the Marine Corps in the warm tropical climes, flying in Santo Domingo, Nicaragua and Haiti, his present station. He likes . . . the romantic, alluring and mysterious tropics and is alive to all their fantastic influences.14

Hemingway would have agreed. His letters suggest that he liked Boyden, but sometimes found the colonel better suited to flying than running an office. As Operation Friendless evolved, the writer would comment that his dealings with the colonel sometimes got a little too “sketchy” for his comfort, so he asked a third party for help in drafting a written plan that would specify who was supposed to do what.15

Thomason and Boyden eventually arranged for Hemingway to receive radio gear, along with the munitions that Hemingway needed to realize his plan. ONI shipped the gear to the embassy in Havana in the diplomatic pouch, and it was then smuggled aboard Pilar. The hand grenades went over the transom in egg cartons, the disassembled guns in small pieces among other more innocent gear. The boat’s communicator, detailed by Thomason and Boyden, would be a 24-year-old Marine warrant officer. Donald B. Saxon was a graduate of the Radio School at Marine Corps Base Quantico, Virginia, who had served with the 4th Marines in China and risen quickly through the ranks in the years since his enlistment in December 1936.16 An American diplomat described him as “a lovely uninhibited character,” and more than one source recorded that he had a bad case of jungle rot eating away at his feet, which some attributed to his service overseas. Saxon’s main pastimes were said to be hard drinking and bar fights.17

Boyden also did his best to support Hemingway’s flimsy cover story, designed to ward off any inquisitive Cuban officials, which was that he was conducting research on fish specimens for the American Museum of Natural History. Boyden prepared what might be called a “get out of jail free” note on official letterhead in an odd mix of English and Spanish that asked the reader to believe that Pilar needed “the radio apparatus” for its work, which was “arreglado” (in order) and “not subversive in any way.”18 If the letter failed to deter a full search, there would, presumably, be no way to explain why a fishing boat was also outfitted for war, and Hemingway might wind up in a Cuban jail until the embassy could intercede on his behalf.

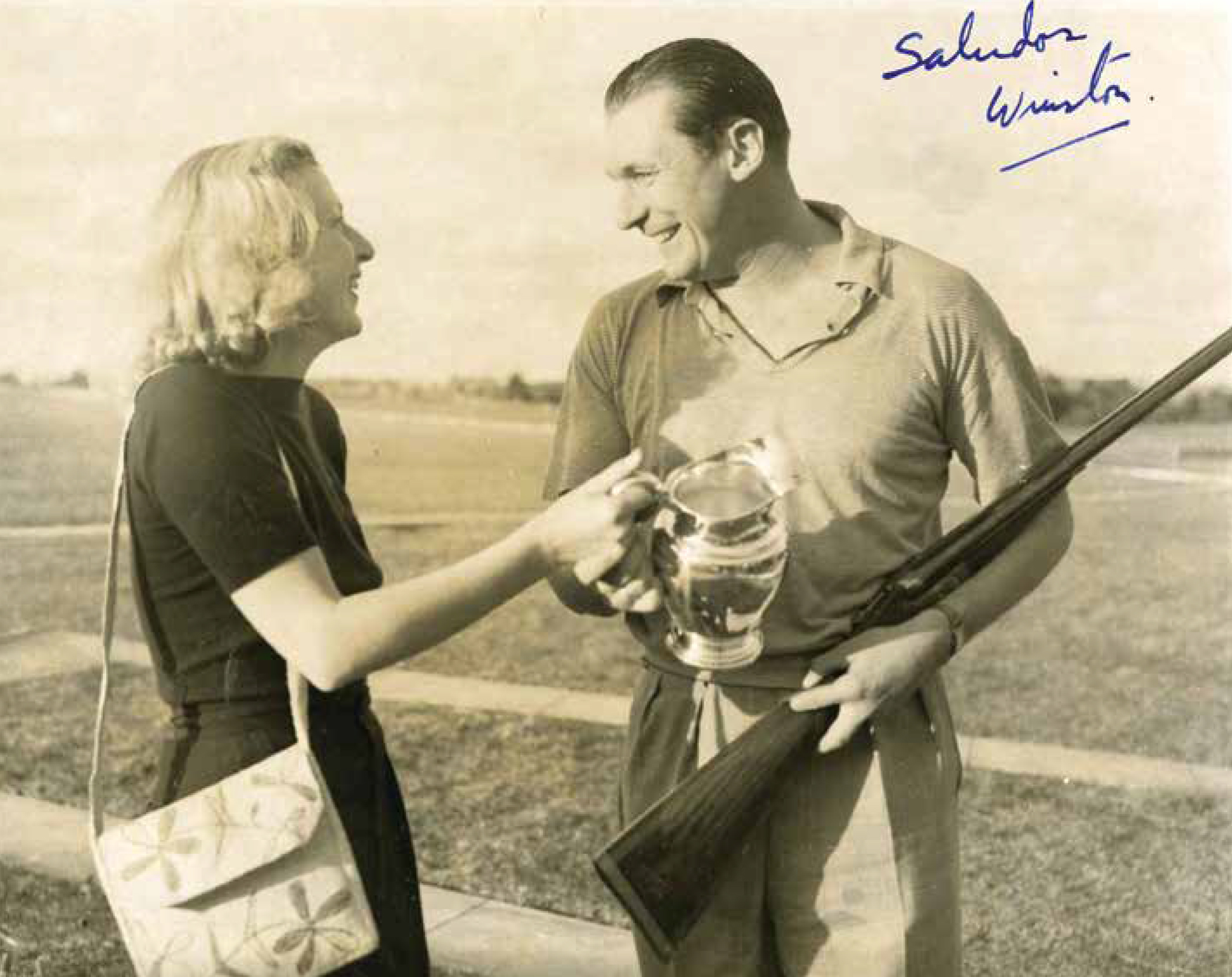

There was yet another Marine—or more accurately a future Marine—serving on board. He was Hemingway’s de facto executive officer, Winston F. C. Guest, whom Hemingway first met in Africa in 1933 on safari. A celebrated sportsman and socialite, Guest was one of a few polo players ever to have earned the 10-goal designation. But he was more than an athlete; he had also earned a law degree from Columbia University, and he was a patriot. Guest wanted very badly to join the armed forces, but in the first part of the war his sports injuries kept him out of the Service, leaving him free to live and work with Hemingway in Cuba.19 Still, his accomplishments and personality made him an ideal deputy. Well-groomed, intelligent, and hardworking, he was also easygoing and eager to serve. Seven years younger than Hemingway, Guest deferred to his senior—and considerably more famous—friend, who bestowed on him the affectionate nickname “Wolfie” after finding that he looked like the actor Lon Cheney in the 1941 movie Wolf Man.

Pilar’s wartime service began during the summer of 1942, first with short-range outings into the waters around Havana. As summer edged into fall, more ONI equipment made its way aboard, and there followed training exercises and something like a shakedown cruise. Hemingway and his men spent time getting to know their weapons. This included a good deal of target practice (often to the detriment of some otherwise perfectly good navigation buoys) and continued to the point where the embassy’s coordinator of intelligence, the foreign service officer Robert P. Joyce, judged that “Pilar was . . . a camouflaged floating arsenal with a tough crew of experienced and highly trained machine-gunners and grenade throwers,” ready for combat.20

After the shakedown period, Pilar ranged farther afield for longer periods, from the northwest coast of Cuba to the Old Bahama Channel hundreds of miles to the east. At least two deployments ran close to three months. In the spring of 1943, Pilar operated for a while out of a makeshift camp on a barren spit of sand known as Cayo Confites, where the crew appears to have displayed a more-or-less cheerful tolerance for hardship. Guest maintained contact with the nearby American consular outpost at Nuevitas, useful for ONI to funnel supplies and information. Through such intermediaries as well as a direct coded channel, Pilar stayed in touch with the embassy in Havana, which relayed messages to the Gulf and Caribbean Sea frontiers of the U.S. Navy.

Hemingway’s third wife, Martha Gellhorn, awarding a shooting prize to Winston Guest, the sportsman who was Hemingway’s executive officer on Pilar’s war cruises. Guest went on to join the Marine Corps in 1944 and served honorably in the last phase of the war in the Pacific. Ernest Hemingway Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

It was a frustrating business. Embassy Havana passed the most recent Navy intelligence on U-boat sightings and suspected locations to Hemingway and his crew. Pilar’s own radio gear intercepted some enemy transmissions. Hemingway would remember hearing German voices over the radio, especially late at night. By day, Pilar looked for the enemy, usually without any success. But there was at least one sighting, which occurred on 9 December 1942, of a probable U-boat. On that calm, clear day, Hemingway saw “a gray painted vessel” six to eight miles away, and sailed toward it to investigate.21 When the gray vessel turned broadside to Hemingway, it presented the silhouette of a conning tower on a long, gray deck. Gliding over the dead-calm sea, it was so large that it looked like an aircraft carrier to Guest. Hemingway would famously claim to have replied, “No, Wolfie, unfortunately she is a submarine and pass the word for everyone to be ready to close.”22 But as Pilar steered toward the intruder, the vessel put on speed and was soon out of range. The message went out immediately from Pilar’s tiny communications shack, presumably from the hand of Don Saxon, to the embassy in Havana, which in turn retransmitted the message to the Navy and the Fleet. The Navy paid Hemingway and Guest a small compliment that it did not pay to all members of the Hooligan Navy:

HAVANA REPORTS SUBMARINE BELIEVED TO BE GERMAN 740 TON TYPE IN SIGHT FROM 1210 Q TO 1340 Q 22-58 N 83-26 W X INFORMANTS TWO RELIABLE AMERICANS ACCOMPANIED BY FOUR CUBANS.23

The enemy that, thankfully, Pilar and her crew never met up close. Art and Picture Collection, New York Public Library

This submarine got away from both Hemingway and the Navy. But Operation Friendless continued well into 1943. In early June, intelligence reports indicated that the Germans were sending submarines back into the area after a hiatus of a few months, and Hemingway was ordered to scour obscure keys and bays for signs of the enemy, a nerve-wracking but ultimately unproductive task.24 Then, after what appeared to be a successful attack by a U.S. Navy plane in nearby waters on 14 June, the pressure eased. By 9 July, Saxon had broken out the coded transmission ending the patrol, and Pilar started the weeklong cruise back to Havana.

It was just as well: the boat needed to go into the yard for an overhaul. Not designed for wartime service, her engine showed the signs of the long hours of patrolling, from loose valves to worn piston rings and a damaged propeller. Once on dry land, Hemingway ordered a new engine, and Don Saxon ordered round after round of drinks and wound up in jail.25

Despite the frustrations, Hemingway was reluctant to give up on his private war, conducted in his own way and with his own resources. He liked being captain of his own ship and hoped to resume the unconventional war patrols once Pilar emerged from the yard. But it was not to be. By now the threat had receded from Cuban waters, and Hemingway waited in vain for the Navy to renew his letter of marque. Christmas 1943 was depressingly quiet for him—without a mission and without a wife. Ever the aggressive reporter, Martha Gellhorn was thousands of miles away on assignment for Collier’s, covering a war whose focus had clearly shifted to the other side of the Atlantic. In November 1942, the U.S. Army had invaded North Africa and by May 1943 joined with the British Army to defeat the once-formidable Afrika Korps and its Italian confederates. It was now just a matter of time before the Allies invaded the mainland of Europe. By January 1944, Hemingway admitted as much to himself and to Gellhorn.26 Pilar’s war was over, and its crew was free to go on to other adventures.

Hemingway went to Europe, where he watched the fighting on D-Day from a landing craft in the surf, flew on combat missions with the RAF, and helped to liberate Paris. Saxon presumably returned to duty with ONI and then went on to a more conventional Marine posting at Camp Pendleton, California, in 1945. After the war, he settled in Florida, occasionally corresponding with Hemingway, who invited him to visit his island home outside the Cuban capital. In 1944, Guest was finally able to enlist in the Marine Corps at a recruiting station in Jacksonville, Florida, which earned him a trip to Parris Island, South Carolina, as a private. A few weeks later, he was able to become a second lieutenant on a waiver (presumably for his previous sports injuries and height) that was entered in his record as a “special order of the Commandant of the Marine Corps.” After commissioning, he joined one of the Marine air wings but apparently not as an aviator.27 A newspaper article describes that he went on to serve with distinction in China in the closing weeks of the war; he received the U.S. Army Soldier’s Medal for landing on a heavily mined airfield on 19 August to deliver badly needed humanitarian aid before the Japanese Army had officially surrendered and its soldiers were still ready and willing to kill Americans.28

Thomason and Boyden also shipped out to the Pacific. Boyden detached from the embassy in Havana in September 1943, and after a few months found himself in the Pacific theater in the summer of 1944. From December 1944 to June 1945, he did solid work as chief of staff and acting wing commander for the 2d Marine Aircraft Wing committed to the fighting in and around Okinawa. The Marine Corps recognized his service with a Legion of Merit with Combat “V.” Upon retirement in June 1949, he was promoted to brigadier general on account of his combat service.29 Thomason was not quite as lucky. After detaching from ONI in spring 1943, he joined a fellow Texan, Navy Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, at his headquarters in Pearl Harbor for service as a war plans officer and inspector of Marine Corps bases in the Pacific theater. Worn out by years of hard living, to say nothing of his love for strong drink, he literally stumbled in the performance of his duties—falling off a pier while on an inspection tour near the front lines. Hospitalized in theater for pneumonia and then twice again after returning home for what he described as “my stomach affliction,” he died at San Diego Naval Hospital on 12 March 1944 at age 51.30

Hemingway published little about his exploits during World War II in his lifetime. But off and on after 1945 he worked on a war novel that his estate published after his death—the three-part Islands in the Stream. The main character, Thomas Hudson, sounds and acts so much like Hemingway himself that one scholar called it “the clearest roman a clef [sic] in American literature.”31 There are many parallels between Hemingway and Hudson’s lives—in their families, activities, and likes and dislikes. The description of the nameless boat in Islands—“not big enough to be called a ship except in the mind of the man who was her master”—could have been used to describe Pilar.32 Taken together, the parallels are so striking that it is fair to look to Hudson’s words for insights into Hemingway’s own mindset.

The third part of the novel is about hunting German submarines in Cuban waters. The major difference between what actually happened and the fictional version is that the novel’s long and frustrating search for the enemy leads to a series of firefights with shipwrecked German submariners on remote keys in Cuban waters. The novel is interesting for what it seems to say about Hemingway’s attitudes toward Marines—attitudes that have been drowned out by the far more numerous (and usually positive) comments in his correspondence about the soldiers he served alongside in Italy and France. Some of his letters hint at his respect for Marines and the Corps, as does his selection of essays by Thomason for the anthology on war that Hemingway edited in 1942.33 But it is only in Islands in the Stream that he writes directly about Ma- rines, seemingly expressing himself through the voice of Hudson.

Islands gives pride of place to the Marine radioman, Peters, who is almost certainly based on Saxon. The many paragraphs about Peters reveal how this particular Marine tests the narrator’s generally positive views of Marines. More than once Hemingway/ Hudson questions Peters’s skill and his fitness for duty. Peters has trouble maintaining the communications equipment, much to the frustration of Hemingway/ Hudson: “That damned Peters with his radio out. I don’t know how he has f——ed it.”34 Peters also drinks when he should not. The nameless boat in Islands did not have rules about drinking at sea except for the unwritten rule that every man must be able to do his job, which Peters violates by being drunk on duty. Mirroring the doubts that Hemingway/Hudson expressed, at least one crewmember is not sure that he wants to be in a firefight alongside Peters. Other members of the crew share their captain’s frustration with him. But Peters also has good traits; for the most part he works hard at fixing his radios when they break. Hemingway writes that Peters “always held himself as a Marine even when he was not at his best and he was proudest of the real discipline without the formalities of discipline which was the rule of the ship.”35 At least in the novel, Peters speaks German and proves his worth when he calls out to the enemy: “Peters spoke so it sounded like the voice of all German doom. His voice holds up magnificently, Thomas Hudson thought.”36 When Peters is killed in the firefight, the crew mourns his loss.

That leaves one Marine character, Willie, who appears to be loosely based on Winston Guest. Instead of being physically unqualified to join the Service, Willie is “one expendable, medically discharged Marine.” But he is still willing to go in harm’s way to fight the remaining Germans. Hemingway/ Hudson views Willie as a “good, brave . . . son of a b——h,” who can be decisive when his captain is not. “He made up my mind for me when I was starting to put things off,” Hudson recounts. Willie finds and defeats the enemy in the climactic encounter, justifying Hemingway/Hudson’s conviction that he “would rather have a good Marine, even a ruined Marine, than anything in the world when there are chips down.”37

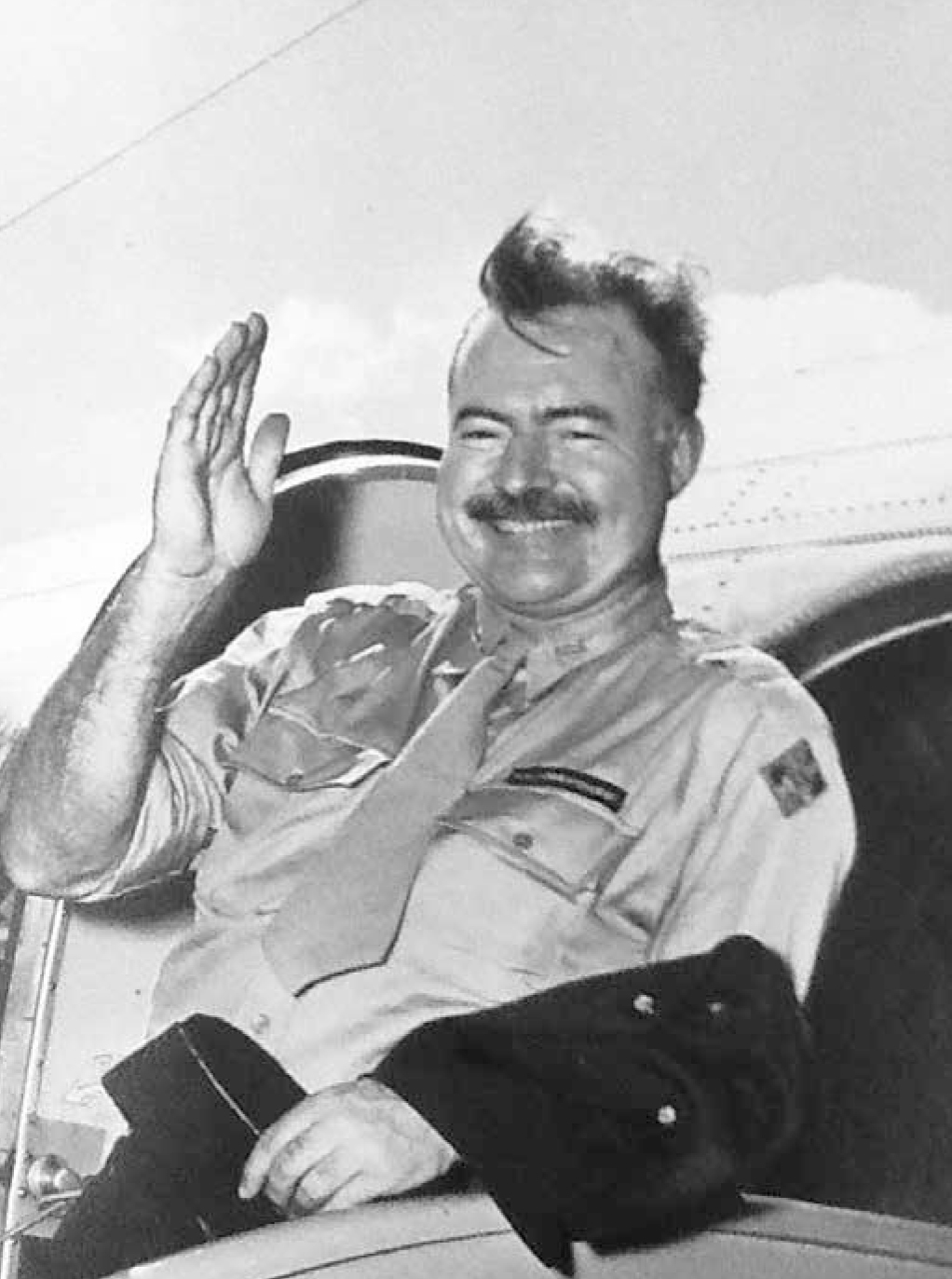

Hemingway, as he looked in early 1945, after his wartime adventures. Pan American Airways photo

This was high praise for the small sea Service and its men who helped Hemingway to fight his private war at sea in 1942 and 1943. It was an unusual kind of independent duty, well away from the mainline Fleet Marine Force. But it was still duty, sanctioned by two senior ONI Marines who placed men and equipment at Hemingway’s disposal. This small band of warriors may not have actually engaged any German sailors in combat, but they all discharged their duty and earned an honorable place in a footnote to the history of World War II.

•1775•

Endnotes

- Col Nicholas E. Reynolds, USMCR (Ret), was officer in charge of the U.S. Marine Corp’s History and Museum Division’s Field History Branch from 2000 to 2004, and he is also the author of a recent New York Times best seller entitled Writer, Sailor, Soldier Spy: Ernest Hemingway’s Secret Adventures, 1935–1961 (New York: William Morrow, 2017). Parts of this article originally appeared in Writer, Sailor, Soldier, Spy, especially in chapter 8, which describes the setting for the meeting between Hemingway and Thomason.

- The Navy’s principal offices were in the building referred to as Main Navy; other subordinate functions were housed elsewhere in the capital.

- There is an excellent summary of Thomason’s career in Donald R. Morris, “Thomason U.S.M.C.,” American Heritage 44, no. 7 (November 1993): 52–66. Other sources include John W. Thomason Jr., biographical file, Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA; and Martha Anne Turner, The World of Col. John W. Thomason, USMC (Austin, TX: Eakin Press, 1984).

- Ernest Hemingway to Charles T. Lanham, 2 November 1946, in Carlos Baker, ed., Ernest Hemingway, Selected Letters, 1917–1961 (New York: Scribner, 1989), 612; and Carlos Baker, Ernest Heming- way: A Life Story (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1969), 365.

- Quoted in Reynolds, Writer, Sailor, Soldier, Spy, 107.

- Quoted in Reynolds, Writer, Sailor, Soldier, Spy, 134.

- Arnold Samuelson, With Hemingway: A Year in Key West and Cuba (New York: Random House, 1984), 24.

- See for example Homer H. Hickam Jr., Torpedo Junction: U-Boat War off America’s East Coast, 1942 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1996).

- Jai alai is a dangerous sport, similar to squash or racquetball, played on an indoor court with a hard, fast-moving ball and a handheld cesta, or basket, something like a shorter lacrosse stick. It was popular in Cuba among Basque exiles from fascist Spain.

- The best sources for Hemingway’s initiative are Ellis O. Briggs, Shots Heard Round the World: An Ambassador’s Adventures on Four Continents (New York: Viking, 1957), 55–57; Spruille Braden, Diplomats and Demagogues: The Memoirs of Spruille Braden (New Rochelle, NY: Arlington House, 1971), 283–84; and Reynolds, Writer, Sailor, Soldier, Spy, 135–37, contains a discussion of the historical background and this sequence of events.

- Briggs, Shots Heard Round the World, x, 57.

- Braden, Diplomats and Demagogues, 284.

- BGen Hayne D. Boyden, “. . . and Santo Domingo,” Marine Corps Gazette 56, no. 11 (November 1972): 58–59.

- “Hayne D. Boyden, First Lieutenant, U.S.M.C.,” Leatherneck, December 1933, 23.

- EH to Robert Joyce, 9 November 1942, Outgoing Correspondence, Ernest Hemingway Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.

- Donald B. Saxon biographical material, Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

- Briggs, Shots Heard Round the World, 59–60; and Gregory H. Hemingway, Papa Hemingway: A Personal Memoir (Boston: Hough- ton Mifflin, 1976), 71–72, recounts family lore about Saxon.

- Hayne D. Boyden to Whom It May Concern, 18 May 1943, Incoming Correspondence, Museo Ernest Hemingway, Ernest Hemingway Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum.

- “Robert Joyce Memoirs,” unpublished manuscript, Robert P. Joyce Papers, MS 1901, Box 1, Yale University Library, New Ha- ven, CT, 51. The 6-foot-5-inch-tall Guest would, in any case, have required a waiver of the Marines’ wartime height limit of 6 feet and 2 inches.

- “Robert Joyce Memoirs,” 53.

- Pilar logbook, Other Material folder, Box 93, Ernest Heming- way Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. For additional context, see Terry Mort, The Hemingway Patrols: Ernest Hemingway and His Hunt for U-boats (New York: Scribner, 2009), 185–88.

- Hemingway to Lillian Ross, 3 June 1950, Folder for 1942, Box 19, Carlos Baker Papers, Princeton University Library, Princeton, NJ.

- Entry for 10 December 1942, WWII War Diaries, Caribbean Sea Frontier, April 1942 to December 1943, Records of the Office of the CNO, RG 38, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) II, College Park, MD, emphasis original.

- Michael Reynolds, Hemingway: The Final Years (New York: Norton, 1999), 78.

- Reynolds, Hemingway, 81.

- Ernest Hemingway to Martha Gellhorn, 13 January 1944, in Reynolds, Hemingway, 88–89. The letter’s reproduction is set within an excellent overview of the issues in the writer’s life during this period.

- Winston F. C. Guest, service record, National Personnel Records Center, NARA, St. Louis, MO; and Winston F. C. Guest, biographical material, Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

- “Capt. Guest Gets Soldier’s Medal,” New York Times, 27 December 1945.

- Hayne D. Boyden, biographical file, Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

- Turner, The World of Col. John W. Thomason, USMC, 340–41. The Thomasons had a home in La Jolla, CA, and Thomason was assigned to Camp Elliott, a Marine base that, by 1960, was turned over to the city of San Diego.

- Ernest Hemingway, Islands in the Stream (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1970); and Thomas Fensch, Behind Islands in the Stream: Hemingway, Cuba, the FBI and the Crook Factory (New York: iUniverse, 2010), 119.

- Hemingway, Islands in the Stream, 332.

- See, for example, the reference to “honest Don” Saxon in Hemingway to Patrick Hemingway, 30 October 1943, in Baker, ed., Ernest Hemingway Selected Letters, 551–52; and Ernest Heming- way, ed., Men at War: The Best War Stories of All Time (New York: Bramhall House, 1942). Hemingway chose four selections by Thomason for this anthology.

- Hemingway, Islands in the Stream, 343.

- Hemingway, Islands in the Stream, 367.

- Hemingway, Islands in the Stream, 424

- Hemingway, Islands in the Stream, 431.