PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

The 1st Marine Division (1st MarDiv) landed on Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands, on 7 August 1942, and during the next four months, the division participated in an ongoing fight to prevent the Japanese from recapturing the island and Henderson Field. Yet, the official historian of the 1st MarDiv wrote, “There are two Guadalcanals: the battle and the legend.”1

One of those legends was born on the night of 24 October when the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, occupied defensive positions south of Henderson Field in a sector normally held by two infantry battalions. The understrength Company C anchored the center of the line and bore the brunt of at least six separate attacks by the Japanese that night.2 Although the fighting was desperate, Company C Marines held the line. Later, on the morning of 25 October, a handmade flag appeared over the Company C line that had been made from white Japanese parachute material and showed a skull-and-crossbones crudely inscribed with “Suicide Charley, 1st Battalion, 7th Marines.”3

Since that night 75 years ago, Company C has been known as Suicide Charley, though the origin of the nickname and the guidon are not widely known outside the company.4 While only a vignette, the lore surrounding Suicide Charley is the type of legend that exemplifies Marine Corps history. This article documents the fight on the night of 24 October and the origin of the Suicide Charley legacy.

Formed in Cuba on 1 January 1941, 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, was commanded by the legendary Lieutenant Colonel Lewis B. “Chesty” Puller. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, the 7th Marines became the nucleus of the 3d Marine Brigade and deployed to protect American Samoa in April 1942. While the 1st MarDiv landed on Guadalcanal on 7 August 1942, 7th Marines did not arrive until 14 September 1942.5

| |

|

Company C, 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, on Guadalcanal between 14 and 23 September 1942 before the first battle on the Matanikau River.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Charley Company

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

This company photograph is widely used in books and publications on Guadalcanal. No publication identifies the unit pictured except in Major John L. Zimmerman’s official monograph, which captioned the photograph as “Fresh troops of the 2d Marine Division during a halt.”1 The troops are obviously fresh and free of disease, their equipment clean and uniforms in good shape. Most of these Marines are armed with M1903 bolt-action Springfield rifles and carry M1905 bayonets and M1941 packs. Two men high on the hill at left wear mortar vests, and one standing in the center has on a World War I-type grenade vest. The Marine seated at far left holds a Browning Automatic Rifle.

In December 1990, the author interviewed Charles Ramsey, a member of Company C on Guadalcanal, who affirmed that this photograph was Company C and was taken sometime between the time the company arrived on Guadalcanal on 14 September 1942 and their first fight along the Matanikau River on 23 September. Ramsey sits high in the center of the picture with his chin resting on his left hand.2

- Maj John L. Zimmerman, USMCR, The Guadalcanal Campaign (Washington, DC: Historical Division, Headquarters Marine

- Charles Ramsey, intvw with Gary Cozzens, December 1990, Woodland Hills, CA.

|

|

|

|

|

The battalion’s table of organization included three infantry companies, one machine gun company, and a headquarters company. Headquarters Company included a platoon of 81mm mortarmen. A machine gun platoon was attached to each rifle company during combat. It was not unusual to have a machine gun platoon attached to a rifle company for months at a time. Each infantry company consisted of four platoons—three infantry platoons and one platoon of .30-caliber air-cooled light machine guns and 60mm mortars. A 37mm gun platoon also was attached to each battalion from the regimental weapons company. At this time, the Marines were using old equipment and did not have radios. Communication took place either by telephone or runner. The total strength of the company was 171 Marines.6

Soon after arrival on Guadalcanal, Lieutenant Colonel Puller’s Marines participated in two major actions. The first occurred along the Matanikau River on 23 September along the northern portion of the Marines’ perimeter. After moving down the river, Companies A and B landed west of Point Cruz, near Honiara, an action in which the battalion executive officer, Major Otho Rogers, was killed.7 Captain Charles W. Kelly Jr., commanding officer of Company C, assumed Roger’s billet, and Captain Marshall W. Moore became the commanding officer of Charley Company. In a second action on 7–9 October, Charley Company acted as the main effort in a regimental-size attack, catching the Japanese 1st Battalion, 4th Infantry, in a draw inflicting 700 casualties.8

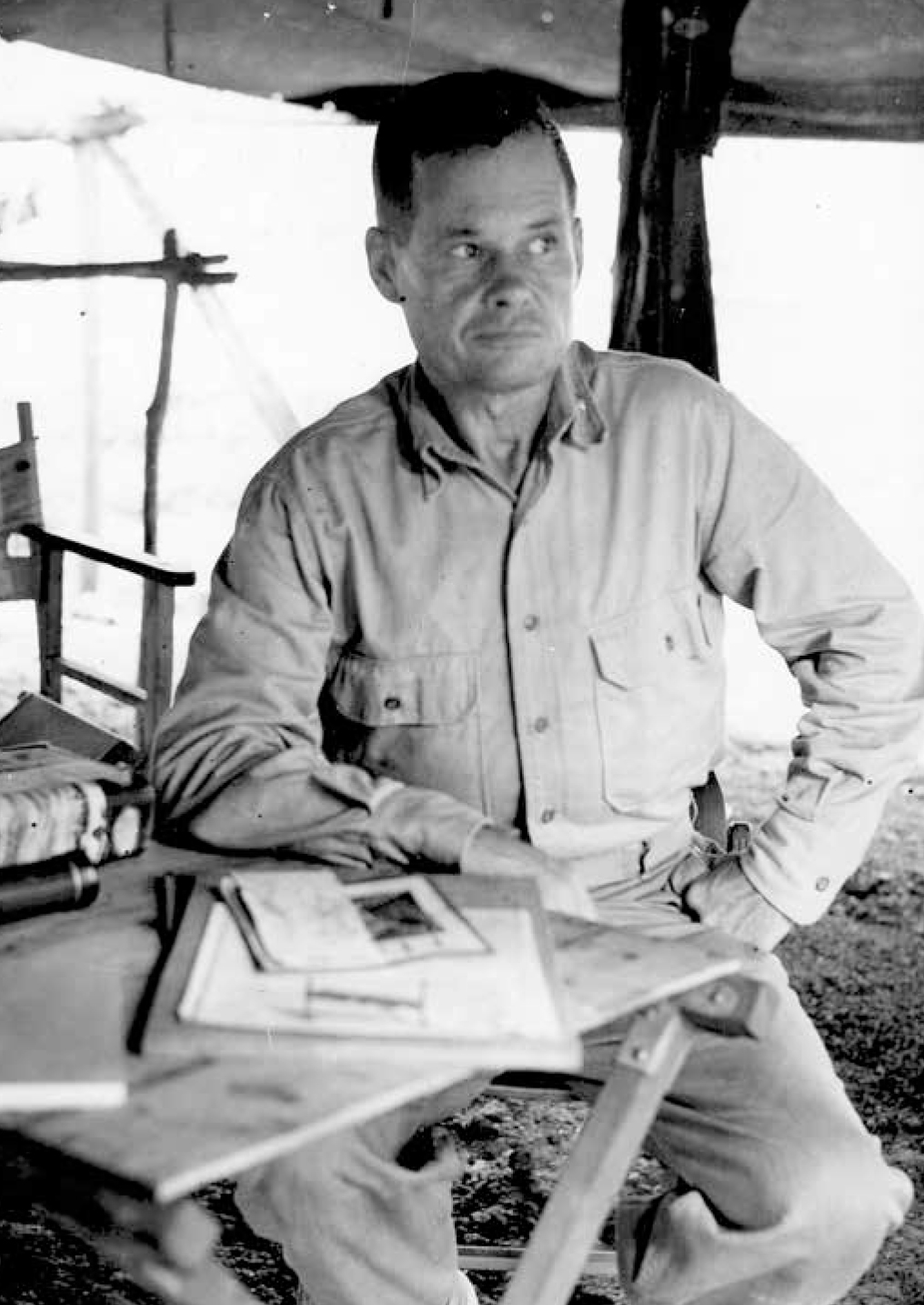

LtCol Puller, commanding officer, 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, on Guadalcanal. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo 91933

Defense of Sector Three

After fighting along the Matanikau River, Puller’s Marines were assigned to defend the eastern half of Sector Three south of Henderson Field. Lieutenant Colonel Herman H. Hanneken’s 2d Battalion, 7th Marines, had been to the 1st Battalion’s right flank of Sector Three on the forward slope of Edson’s Ridge, but had redeployed on 23 October to the Matanikau River in anticipation of the next Japanese attack.9 As a result, Puller’s Marines assumed the defense for all of Sector Three in the 1st MarDiv’s perimeter, approximately 2,500 meters normally assigned to two infantry battalions.10

| |

|

Charley Company

Marshall W. Moore was born in Geneva, New York, on 17 September 1917. He enlisted in the Marine Corps in Buffalo and reported to Quantico, Virginia, on 18 October 1940 as a private first class. Following Officer Candidate School, he attended Officers Class and was commissioned a second lieutenant in 1941. Moore joined 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, at New River, North Carolina, and was initially assigned to Company A as 3d Platoon commander.

He was promoted to first lieutenant on 28 February 1942. He then became commanding officer of Company C on Guadalcanal on 27 September, participating in all of Company C’s battles, until immediately after the action at Koli Point when, on 3 December 1942, he was evacuated as suffering from malaria, yellow jaundice, amoebic dysentery, and excessive weight loss (40 pounds).

For his actions in the defense of Henderson Field on the night of 24 October, Moore was awarded the Silver Star. After recovering his health, he assumed command of Company A and led that unit in the battle on New Britain. Following World War II, Moore remained in the Marine Corps Reserve and retired as a colonel in 1958. His son, John, also a Marine infantry officer, was killed in Vietnam in December 1968. Marshall Moore died on 22 February 2004 and is buried in the Glenwood Cemetery in Geneva, New York.1

Moore’s Silver Star citation reads:

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Silver Star to Captain Marshall W. Moore, United States Marine Corps Reserve, for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity as Commanding Officer of Company C, First Battalion, Seventh Marines, FIRST Marine Division, in action against enemy Japanese forces at Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands, on the night of October 24, 1942. Despite continuous and dangerous assaults by a numerically superior Japanese force which was attempting to smash the Lunga defense lines, Captain Moore daringly commanded his men in maintaining our positions and repulsing the enemy. With utter disregard for his own personal safety, he led his company in brilliant and devastating counterattacks and contributed to the rout and virtual annihilation of an entire Japanese regiment. His indomitable fighting spirit and grim determination served as an inspiration to the men under his command and were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.2

|

Moore, USMCR (Ret) Maj Marshall W. Moore (ca. 1944) was the commanding officer during the fight for Henderson Field. Photo courtesy of Col Marshall W. Moore, USMCR (Ret) Maj Marshall W. Moore (ca. 1944) was the commanding officer during the fight for Henderson Field.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

- Maj John L. Zimmerman, USMCR, The Guadalcanal Campaign (Washington, DC: Historical Division, Headquarters Marine.

- Charles Ramsey, intvw with Gary Cozzens, December 1990, Woodland Hills, CA.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Leadership within the Marine ranks demonstrated the confidence the Marines brought to the situation. In addition to Moore, other leaders in Company C included First Sergeant Lewis C. Oleksiak; Gunnery Sergeant Charles Livelsberger; platoon commanders First Lieutenants Karl H. Schmidt Jr., Arthur H. Wyman, and Marine Gunner William Fleming (2d Platoon); and platoon Sergeants Robert L. Domokus (1st Platoon), London L. Traw (2d Platoon), and Simon Viger (3d Platoon).11

Puller and Kelly discussed the employment of the battalion and decided Kelly would take one platoon from each rifle company with attached machine guns, and occupy the position vacated by Hanneken. The terrain was much more favorable for defense, and Puller and Kelly thought it could be held with fewer men. This method of filling in the gap proved to be fortuitous. Kelly was accompanied by Captain William Watson, the battalion S2 (intelligence), communicators, and a couple corpsmen. The composite company spent its time bringing in ammunition and supplies and familiarizing themselves with the defensive features of the area.12

It was obvious to the Marines that a large-scale Japanese attack would be a real threat in the near future. Accordingly, Puller’s Marines improved the defensive line and registered the final protective line in the perimeter defense. Barbed wire was woven into double apron fences and hung with empty ration cans and items that would make a racket and expose attempts to breach the wire. Fields of fire were cleared for the automatic weapons and mortar and artillery targets were preregistered. The Marines also removed the machine guns from disabled airplanes at Henderson Field and incorporated them into the defensive fires.13

All during the day of 24 October, Puller drove his men to complete their defensive positions. From left to right facing south, Puller’s defense consisted of Company A (Captain Regan Fuller), Company C (Captain Moore), Company B (Captain Robert H. Haggerty), and the composite company (Captain Kelly). The battalion’s weapons company, Company D (Captain Robert J. Rodgers), had machine guns attached to each line company. Master Gunnery Sergeant Ray Fowel’s 81mm mortars provided indirect fire support. A platoon of four 37mm antitank guns (used in an antipersonnel role) from Captain Joseph E. Buckley’s regimental weapons company also interspersed in the line.14 Several hundred yards in front of Company A’s position sat a combat outpost manned by platoon Sergeant Ralph Briggs’ platoon. To Company A’s left (east) was 2d Battalion, 164th Infantry, an Army National Guard battalion from North Dakota and Minnesota. The point where Company A’s line joined the Army National guardsmen had been coined “Coffin Corner,” while the open area in front of the lines was called the “Bowling Alley.”15

Battalion formation of 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, on Guadalcanal, September 1942. Lewis B. Puller Collection, COLL/794, Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division

A trail ran through the center of Company C’s position that was protected by a cheval-de-frise, which in turn was set into a double apron of barbed wire.16 The Marines opened and closed this cheval-de-frise to allow patrols in and out through the perimeter. Sergeant John Basilone and his section of heavy water-cooled .30-caliber Browning machine guns from Company D were attached to Company C and emplaced in the company’s line. It was at this point that the major Japanese attack occurred on the night of 24 October.17 After only a month as company commander, Moore was now faced with establishing a defensive position with one-third of his company detached. On the afternoon of the attack, Moore sat in the company command post, feeling uneasy about the situation. He suggested that his Marines string another double apron of barbed wire behind the cheval-de-frise. At approximately 1600, they put on heavy gloves and strung more barbed wire, paying particular attention to the area behind the cheval-de-frise. The wire was strung in such a way as to make it very difficult to get through in the dark; so difficult, in fact, that a person would have to weave through. This tactic proved a great asset, as the Japanese apparently did not know it was there. Moore’s men also installed trip flares in the wire.18

Throughout the line, foxholes were deepened, crew-served weapons positions prepared, targets registered, and tactical wire emplaced. Some fighting positions were large enough for three men and surrounded with sandbags, leaving only a window to shoot through and a crawl space in the rear through which to enter and exit. The fighting holes were then covered by laying coconut logs on the sandbags, with another tier of sandbags atop the logs.19

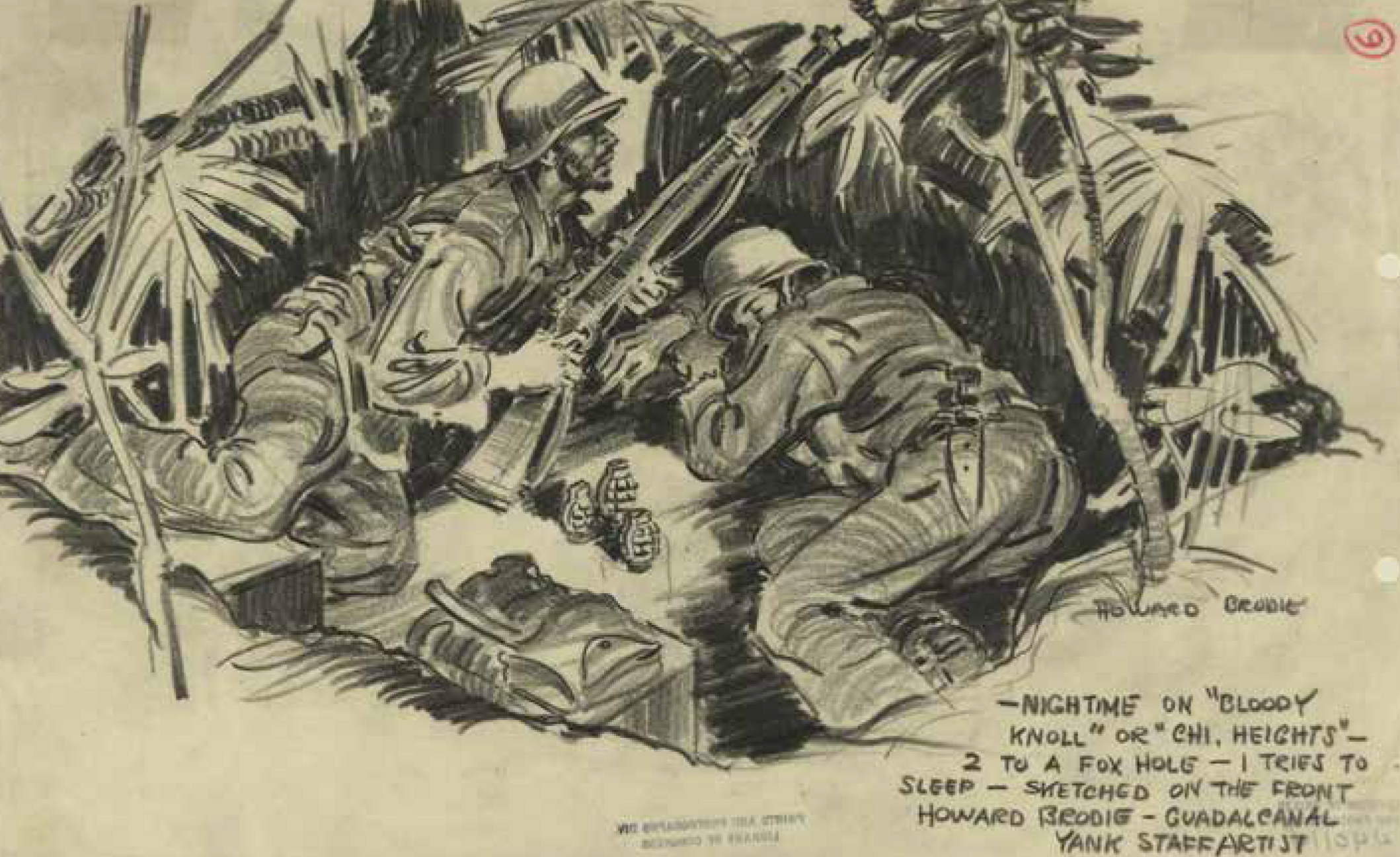

Bloody Knoll by Howard Brodie. Brodie—an artist for Yank, the Army newspaper—was assigned to sketch Marines and soldiers on Guadalcanal in late 1942 and early 1943. Here, he captures a fighting hole with a Marine on watch and one trying to get some sleep. Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppmsca-22672

A cheval-de-frise in front of the Charley Company lines during the defense of Henderson Field. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo 5157

Runners took messages from the battalion commander to the front lines where Company C was on the edge of the jungle. The company had cleared foliage in front of its positions about 100 yards into the jungle. In this stage of the war, Marines were using the M1903 Springfield .30-caliber rifles left over from World War I. 20

Meanwhile, the Japanese were not idle. A Marine on patrol saw a Japanese officer observing Henderson Field through field glasses.21 Another Marine observed a large amount of smoke, apparently from cooking fires, rising from the jungle floor in Lunga Valley, two miles south of Puller’s position.22 Unfortunately, those two pieces of information never reached Puller.

These Japanese soldiers of the 17th Army, commanded by Lieutenant General Harukichi Hyakutake, were some of Japan’s finest, particularly the regiments of Lieutenant General Masao Maruyama’s 2d (Sendai) Division whose motto was “Duty is heavier than a mountain, but death is lighter than a feather.”23 Colonel Masajiro Furumiya’s 29th Infantry Regiment, followed by Colonel Toshiso Hiryasu’s 16th Infantry Regiment, would spearhead the attack by the Japanese left flank under the command of Major General Yumio Nasu. The right flank attack, under the command of Major General Kiyotake Kawaguchi, would consist of Colonel Akinosuka Oka’s 124th Infantry Regiment supported by Colonel Toshinari Shoji’s 230th Infantry Regiment. Kawaguchi balked at his orders to attack the right side of the Marines’ line and was relieved as the commander of the right wing by Colonel Shoji. According to General Hyakutake’s original plan, the attack was to occur on 18 October, but the intense jungle terrain and the uncooperative weather caused a postponement until the 22d that was later pushed back to the evening of 24 October.24

As the Sendai Division approached from the south, it reached a point it believed to be about a mile south of Henderson Field by about 1400. With the attack set for 1900, the two wings of the division opened four trails through the jungle to the American lines. Rain began to fall about 1600 and intensified an hour later, causing chaos among the Japanese. Darkness further obscured their ability to navigate. Due to these difficulties, the Sendai Division missed its assigned attack time and was still moving north when the rain ended and the clouds opened up to reveal a brilliant full moon.25

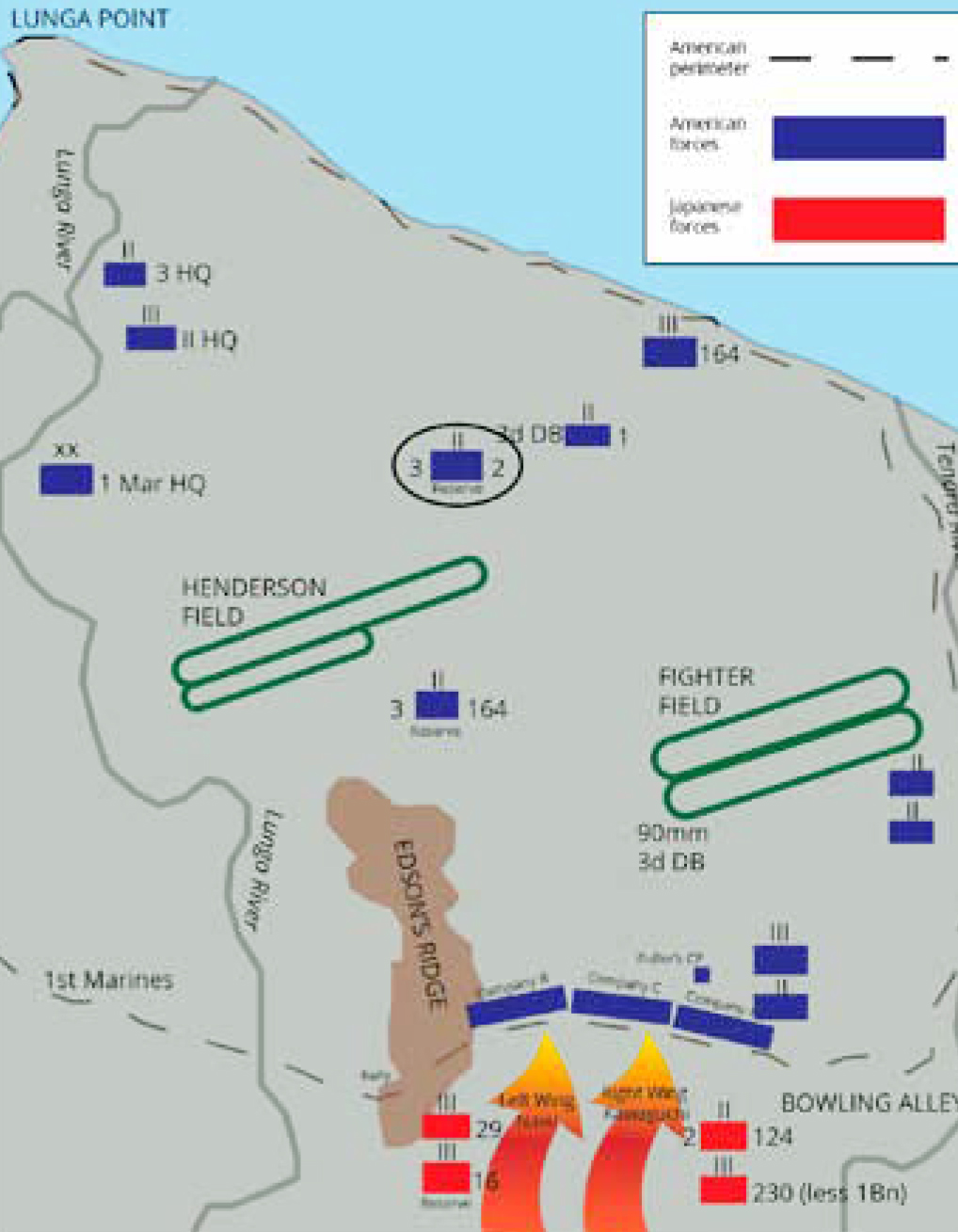

Battle for Henderson Field, 24–25 October 1942. Map by History Division

After the battle, a diary written by First Lieutenant Kozaburo Miyazawa, commanding officer of 2d Machine Gun Company, 2d Battalion, 29th Regiment, was discovered that detailed the devastation to the Japanese soldiers. The 29th Regiment was to assault Mukade (Bloody Ridge) with one blow and sweep all the artillery positions west of the airfield.26 As the regiment advanced to complete the mission, an officer patrol was dispatched to observe Marine lines due to extremely difficult terrain as a heavy rain fell, delaying the unit’s advance. Miyazawa wrote on 24 October that the Japanese finally encountered the Marines. The Japanese regiment was advancing with 3d Battalion in the lead and 1st Battalion on the right front. However, as no movement could be seen, contact could not be maintained. The 2d Battalion was to have been the reserve for the infantry group, but it followed directly behind the regiment.27 On the east flank of the Japanese attack, Shoji’s force turned right to run parallel to the Marines’ lines. All but one battalion—1st Battalion, 230th Infantry—failed to make contact with the Americans and drifted out of the action.28

The Japanese Attack

With darkness fast approaching, the Marines prepared for the coming onslaught. Lieutenant Colonel Puller ordered the lines on the field telephones to be left open for instant communications with subordinates. At approximately 2100, rain began to fall again, making the night even darker under the thick jungle canopy.

At 2130, the combat outpost from Company A reported to the battalion that it was surrounded by the Japanese. Puller directed them to push to their left (east) and return through 2d Battalion, 164th Infantry, to Company A’s position if possible. A short time later, the Japanese taunted the Marines by yelling, “Blood for the Emperor!” and “Marine you die!,” in an attempt to entice them to give away their position. After more than a month on the island, Puller’s men were too wise to fire at the voices. Instead, they replied with their own taunt, “Blood for Franklin and Eleanor [Roosevelt].”29 Suddenly, at 2200 on 24 October, the Japanese came toward the Marines’ lines in a rush.30 Luckily for Captain Moore’s men, the cheval-de-frise in front of Company C’s position caught the Japanese by surprise and they were momentarily halted.31 Japanese records indicate that it was Colonel Shoji’s 1st Battalion, 230th Infantry, that hit Puller’s lines first on the right at 2200, running into Company A. They were followed by the whole of Major General Yumio Nasu’s left wing, attacking in a column of battalions. The 9th Company, 3d Battalion, 29th Infantry, rapidly moved straight into the cheval-de-frise in front of Company C and was decimated.32

Marine artillery and mortars were firing supporting missions in such volleys that the powder bags heated in the weapons and “cooked off” from hot barrels, causing “short rounds narrowly missing the Marine’s position.”33 Moore’s men had emplaced their barbed wire entanglements so securely that wave after wave of Japanese assault troops were hung up and died on it. The company eventually was infiltrated, but afterward, the Japanese seemed confused and made little effort to take advantage of the penetration.34

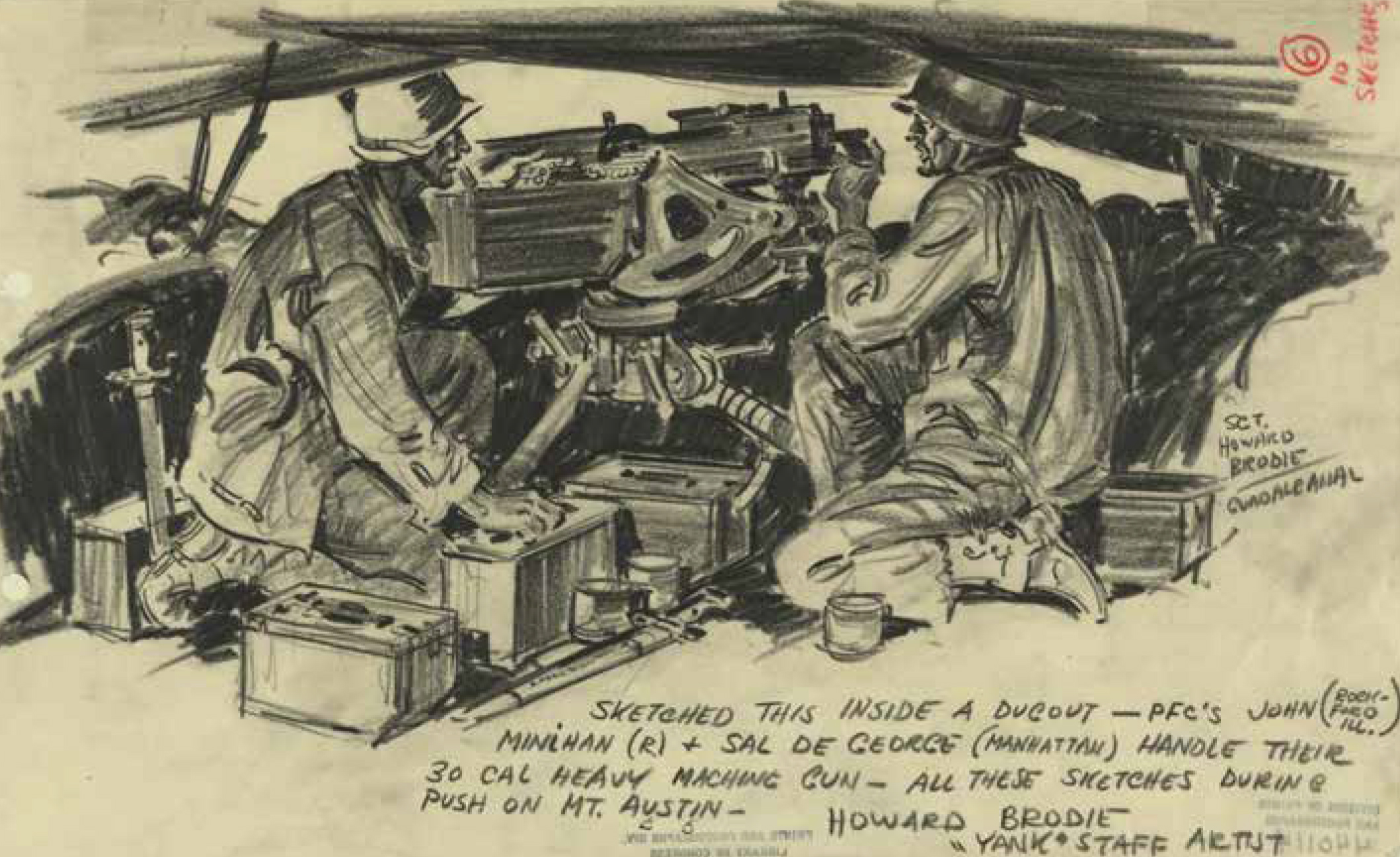

Inside a Dugout by Howard Brodie. This sketch of a .30-caliber heavy Browning machine gun depicts what Sgt John Basilone and his machine gunners would have looked like in the fight for Henderson Field on the night of 24 October 1942. Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppmsca-22675

Sergeant John Basilone

At 0015 and again at 0300, General Marayama’s Sendai Division attacked in the most concentrated effort of the night. When the first wave came, the Marines kept firing and drove the Japanese back. Ammunition supplies were getting low, so Basilone left the guns and ran to his next gun position to get more. Upon his return, a runner arrived and told Basilone that the Japanese had broken through the emplacements on the right, killing two of the crew and wounding three, and the guns were jammed. Basilone moved up the trail and found 18-year-old Private Cecil H. Evans screaming at the Japanese to “come on.” Basilone returned to his own guns, grabbed one machine gun, and told the crew to follow him up the trail. While he cleared the jams on the other two guns, the Marines set up their weapons. The Japanese still coming at the lines pinned the Marines down at their positions. Basilone rolled over from one gun to another, firing as fast as they could be loaded. The ammunition belts were in bad shape because they had been dragged on the ground, forcing the gunners to scrape the mud out of the receiver. Still, some Japanese soldiers infiltrated behind the lines, so the Marines would have to stop firing and shoot at infiltrators with small arms. At dawn, the gun barrels were burnt out after Basilone’s machine gun section fired 26,000 rounds.35

Company C was stretched out over a wide area in a very thin line that had been decimated by heavy casualties and illness. Sergeant Louis S. Maravelas of 2d Platoon and his squad were in position to the right of Basilone’s section protecting the guns, and in the confusion of the fight, they could not see to the right of the line. Firing was heavy and contact between platoons was very poor. Maravelas and his Marines fixed bayonets and returned fire. Basilone had the bodies of the dead Japanese piled two, three, and four high in front of his emplacement.36

Reserves Committed

The Marines poured their fire into the Japanese attack, which was centered on Company C’s line. Pull- er telephoned Brigadier General Pedro A. Del Valle, commanding officer of the 11th Marines, requesting artillery support. The battalion’s operations officer, Captain Charles J. Beasley, called Colonel Gerald C. Thomas, the division chief of staff, requesting reinforcements.37

As the situation became more serious, Lieutenant Colonel Julian N. Frisbie, the 7th Marines regimental executive officer, called Captain Kelly from the regimental command post 600 yards directly behind Kelly’s position and told the captain he was sending up a battalion of the U.S. Army’s 164th Infantry. He asked if Kelly could guide them into position in Puller’s area. Kelly told Frisbie he would have runners there by the time the Army troops got up to the lines. The fortunate result of Puller’s method of filling in the area Hanneken’s battalion had vacated with a platoon from each company position in Kelly’s area was that it was a simple matter for each platoon to send a man to Kelly, since they were thoroughly familiar with the location of their parent units and the access routes. The runners arrived at Kelly’s command post, where he briefed them on their task. Kelly then ordered Captain William Watson to take the guides to Frisbie’s position and to be sure that they each picked up an Army company to lead to their own company area. The 7th Marines chaplain, Father Matthew F. Keough, led the Army battalion into position with Marines from Captain Kelly’s position acting as guides to their parent companies.38 While the Army units moved forward, Company L, 3d Battalion, 164th Infantry, reinforced Company A; Company I, 3d Battalion, 164th Infantry, reinforced Company B; and Company K, 3d Battalion, 164th Infantry, reinforced Charley Company. All the Army companies were in position by 0345. The movement went smoothly and the reinforcements were fed in from behind the Marine company positions. The soldiers were fed into the line piecemeal rather than as tactical units.39

Sergeant John Basilone

MEDAL OF HONOR CITATION

For extraordinary heroism and conspicuous gallantry in action against enemy Japanese forces, while serving with First Battalion, Seventh Marines, First Marine Division, in the Lunga Area, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands, on October 24 and 25, 1942. While the enemy was hammering at the Marines’ defensive positions, Sergeant Basilone, in charge of two heavy machine guns, fought valiantly to check the savage and determined advance. In a fierce frontal assault with the Japanese blasting his guns with grenades and mortar fire, one of Sergeant Basilone’s sections, with its gun crews, was put out of action, leaving only two men to carry on. Moving an extra gun into position, he placed it into action, then, under continual fire, repaired another and personally managed it, gallantly holding his line, until replacements arrived. A little later, with ammunition critically low and the supply lines cut off, Sergeant Basi- lone, at great risk of his life and in the face of continued enemy attack, battled his way through hostile lines with urgently needed shells for his gunners, thereby contributing in a large measure to the virtual annihilation of a Japanese regiment. His great personal valor and courageous initiative were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval service.1

|

|

Sgt John Basilone receives his Medal of Honor on 21 May 1943 in Australia. Basilone was a machine gun section leader from Company D attached to Suicide Charley on the night of 24 October 1942. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo 56976

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- Blakeney, Heroes, 16.

|

From Kelly’s position on the ridge, it was readily apparent when the new troops were in position, as the sound and tempo of firing picked up significantly. The Army units were armed with M1 Garand .30-caliber rifles, which had a much higher rate of fire than the old Springfields used by the Marines. The sounds of the battle were deafening at times, only to diminish and then pick up again as the Japanese rolled back in. Up on the ridge, Captain Kelly felt he had a grand-stand seat—he could see the action laid out in front of him, though off to the left on the low ground, he could only guess at the progress of the battle. Puller called in all the available artillery, and Kelly heard it firing at such reduced range that its rounds were coming in close overhead—so close that a few short rounds landed behind Marine lines. Fortunately, no casualties resulted from friendly fire.40

The next assault by the Japanese at about 0400 was somewhat unexpected in its execution. Marine and Army units were mixed into the line piecemeal. At daylight, although the American line had held, a small Japanese salient existed between Companies C and B, plus the infiltrators who had penetrated the lines.

Private Theodore G. West

NAVY CROSS CITATION

The President of the United States takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Theodore Gerard West, Private, U.S. Marine Corps (Reserve), for extraordinary heroism and conspicuous devotion to duty while serving with Company C, First Battalion, Seventh Marines, FIRST Marine Division, during action against enemy Japanese forces in the Lunga Area of Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands, on 25 October 1942. During a heavy attack by a numerically superior enemy force, Private West, although wounded to such an extent that he was unable to handle a rifle, remained in his position until reinforcements arrived, then rendered invaluable assistance by placing two rifle squads and directing their fire. His gallant action thereafter contributed materially to restoring our line and to the eventual rout and virtual annihilation of an entire Japanese regiment. His courageous devotion to duty, maintained for nearly seven hours after he was severely injured, was in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.1

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- “Theodore Gerard West”; and Blakeney, Heroes, 115.

|

One of the Marines leading reinforcements into the lines that night was Private Theodore G. West. Though wounded and unable to fight, West continued to maintain his position on the line and directed reinforcements into position and into the fight. His actions “contributed materially to restoring our line and to the eventual rout and virtual annihilation of an entire Japanese regiment.” For his actions, Private West was awarded the Navy Cross.41 In his official report of the battle, Puller stated that “the conduct of [A]rmy reinforcements on the night of 24–25 October were exemplary and they arrived just in time.”42

Captain Kelly and his composite company also saw action on the night of 24 October, but not to the extent of the rest of the battalion. Kelly kept his phone lines open and tied into the battalion’s communication net to allow constant communication with Puller and the other frontline command posts. It was raining hard and pitch dark when the Japanese finally came to the wire, and they were massed when the order came to open fire. It could not have been a more ideal situation from a defensive standpoint. The Japanese piled up on the wire, mowed down as they advanced. They would back off to regroup and then, at the shouted urging of their officers, they would advance again in a banzai charge.43

Miyazawa’s diary recorded that, when Japanese encountered the Marines, it was necessary to advance along a trail made by the Americans. The Marines had excellent detectors set up to announce Japanese movement, resulting in intense machine-gun and mortar fire. Even though it was night, the Marines had effective plots that inflicted heavy losses on the Japanese. However, the 3d Battalion, 29th Infantry, commander strove to break through. Each company began its ordered assault, but because of the heavy concentration of mortar and machine-gun fire, the attempt was delayed. About this time, the regimental commander, Colonel Masajiro Furumiya with 7th Company, penetrated the Marines’ position, but made no progress. Finally, dawn broke and American fire became more intense, almost annihilating 3d Battalion. According to Miyazawa, Japanese battle losses at the mukade were estimated at 350 killed, 500 wounded, and 200 missing for a total of 1,050.44

All night on 24 October, the Japanese hit Company C with a regiment of troops in waves of suicidal attacks. They threw their bodies into the machine gun emplacements, forcing the gunners to evacuate the bunkers and fire from the top. During the night, Marines transported ammunition to the frontlines.45

One Company C machine gun emplacement on the right side burned out the lands and grooves of two air-cooled .30-caliber barrels for their machine gun.46 The 2d Platoon sergeant, London Traw, was on the right with a water-cooled .30-caliber machine gun. He was blown up with Japanese dynamite and killed that night.47 The medical personnel in the battalion aid station cared for the wounded under exceedingly adverse conditions. They worked in virtual darkness and heavy rain amid tremendous battle noises to save the most severely wounded.48

At approximately 0500, a small group of Japanese from the 7th Company, 3d Battalion, 29th Infantry, broke through the Marine lines and drove a salient between Companies B and C. The penetration was quickly sealed, and Company C held the line throughout the night despite multiple Japanese attacks. Thirty-seven Japanese were killed, reducing the salient, and 41 more died in the rear of the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, line the following day during the mopping-up effort led by First Lieutenants Arthur H. Wyman and Karl Schmidt and Sergeant Robert L. Domokos.49 After sunrise, the Japanese mounted one more serious attack, but were easily beaten back.50

Private Ralph Tulloch of the regimental weapons company had gone to sleep in the back of an open truck. Upon being awakened, he was ordered to the ammo dump and picked up a load to take to the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines. Tulloch had not been to 1st Battalion’s position and asked if someone at the ammo dump would ride shotgun to guide the way. The normal route was under enemy attack.

With as much ammo as he could stow in the truck, Tulloch slowly left the ammo dump. He turned left on a trail at the foot of Bloody Ridge and headed into the jungle east toward 1st Battalion’s lines. Heavy rain continued, though an occasional sliver of moonlight helped guide the driver. At the base of Bloody Ridge, the ground was slippery with mud, and water stood a foot deep.

It was now 0300 on 25 October, and the main attack of the Japanese focused on Company C’s position. With tracers and the sound of rounds from Japanese machine guns overhead and debris from the trees falling, Tulloch struggled against his instinct to stop and find cover. After some time driving in blackness, Tulloch turned on the blackout lights, but they did not help. He stopped the truck and picked up a piece of wood that gave off what he called foxfire. He asked the guide to walk on the left side of the trail holding the foxfire where he could see it along the trail.51

Tulloch passed what he later learned was 3d Battalion, 164th Infantry, moving along the trail to reinforce Puller’s battalion. He was stopped by someone from the battalion command post, who asked him to unload part of the machine gun and rifle ammo there. Tulloch and the guide carried some to the front lines a short distance away to supply the machine guns for Sergeant Basilone, while the rifle ammo was placed under a poncho at the Company C command post.

The truck slid off the trail at the base of the ridge, leaving Tulloch’s vehicle mired in mud, with all four wheels spinning. Trapped inside the vehicle, he could not get out and a sniper started firing at him. Three or four rounds hit the truck bed and ricocheted. One round hit the lower left corner of the windshield, forcing Tulloch to take cover in front of the truck and return fire blindly in the general direction of the sniper. After about 30 minutes of quiet, Tulloch managed to get the truck out and go after another load of mortar, 37mm, rifle, and machine gun ammo, water, and rations, which he delivered at daylight.52

The Morning After

The Marines exacted a heavy toll in the Battle for Henderson Field. Major General Yumino Nasu (commander of the left wing), Colonel Yoshi Hiroyasu (16th Infantry), and Colonel Masajiro Furumiya (29th Infantry) were killed in action. Japanese reports account for more than 1,050 killed, missing, or wounded from the 29th Infantry alone. American figures showed 250 dead Japanese were found within the 1st Battalion’s lines, 25 of whom were officers. A total of 1,462 dead Japanese were counted in front of the battalion’s position. Another account states that after the night of attacks, more than 400 Japanese were counted in the cone of machine gun fire in front of Company C’s position; they were buried in a common grave.53

Kamekichi Kusano, a 23-year-old private in 7th Company, 2d Battalion, 29th Regiment, wrote: “The 29th [Infantry] attacked the first day and was led into a trap and the majority of the regiment was killed. The dead were piled three and four deep. Only two or three hundred survived the attack.”54

John Stannard, then a sergeant in Company E, 3d Battalion, 164th Infantry Regiment, recalled that “the carnage of the battlefield was a sight that perhaps only the combat infantryman, who has fought at close quarters, could fully comprehend and look upon without a feeling of horror.”55

At daylight the next morning, the front lines revealed a stack of dead Japanese piled up in front of Company C’s position. The U.S. Army was left to clean up and quickly bury the dead to prevent diseases. Korean prisoners, whom the Japanese had brought onto the island as forced labor, were assigned to bury the Japanese dead. Marine engineers blew three holes in front of Company A’s old position, and in three days, the Koreans buried more than 700 dead Japanese.56

Casualties for Puller’s battalion were 19 dead, 30 wounded, and 12 missing. Company C’s casualties were 9 dead and 9 wounded.57 To date, the battalion had suffered 24 percent casualties and 37 percent officer casualties on Guadalcanal.58 Puller later summed up the fight: “We held them because we were well dug in, a whole regiment of artillery was backing us up, and there was plenty of barbed wire.”59 When the Marines were relieved by the soldiers and sent to new positions farther up on Bloody Ridge, they all were equipped with the new M1 Garand rifles instead of their issued Springfield bolt-action rifles. Soon after, however, a directive ordered the return of the M1 rifles to the Army and the Marines got their old Springfields back.60

The 3d Battalion, 164th Infantry, relieved Puller from perimeter defense and he shifted his battalion on the ridge, so what was left of the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, now occupied the position previously held by 2d Battalion, 7th Marines. The rain stopped and sunlight hit the ridge, giving the Marines a chance to dry out and rest. That night, the Japanese tried a repeat performance, with their main effort coming at the same area as before, though now occupied by 3d Battalion, 164th Infantry. They made desultory attempts on 1st Battalion, 7th Marines’ new position on the ridge, a few straggled down the bank of the Lunga River, and some were simply laggards who were lost. At 0800 on 26 October, General Hyakutake ordered his forces to retreat.61

Usually conservative when awarding personal decorations, the Marine Corps recognized Company C’s stubborn defense the night of 24–25 October. Charley Company Marines received one Navy Cross, two Silver Stars, one Bronze Star, and nine commendations for their actions that night. In addition to Basilone’s Congressional Medal of Honor, attachments to Company C were awarded two Navy Crosses, two Silver Stars, and one commendation.62

The Suicide Charley Guidon

The morning of 25 October saw the collapse of the Japanese attack and the defensive line of the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, still intact. Later that morning, a flag appeared over Charley Company’s position. It had been fashioned from white Japanese parachute material and crudely painted with a skull and cross-bones and the inscription “Suicide Charley, 1st Battalion, 7th Marines.” The flag would continue to appear throughout the hard-fought battle for Guadalcanal.63 No picture of the original guidon is known to exist, however, the best evidence comes from oral history interviews conducted with the U.S. Marines who saw the original guidon on the morning of 25 October. Private First Class Richard L. Fisher remembers:

The guidon was sticking in the ground near the foxhole of PFC William Wentz during the day between the Japanese attacks of October 24th and 25th. I asked PFC Paul Hatfield who made it. Paul just shook his head. I was with a small group that rotated back behind the lines for chow and the guidon was near one of Basilone’s machine gun emplacements when I returned. I tried to sleep for a while. Later Puller, Capt. Kelly and our quartermaster sergeant came by and I woke up. [Corporal Edward] Kleason, quartermaster sergeant, was carrying the flag. Puller was smoking a pipe. He grinned out of the corner of his mouth. “Go back to sleep old man, we may not get any tonight.” Kleason kept the guidon in a box in his tent. I only saw it that one morning.64

Private Ralph Tulloch of the regimental weapons company also remembers seeing the Suicide Charley guidon that same morning:

[T]he only time I remember seeing it [the flag] was after the 1st Battalion moved to the right on Bloody Ridge, taking over the positions where the 2d Battalion, 7th Marines had been three or four days before, they [2d Battalion, 7th Marines] moved to the Matanikau River area. This would have been 25 or 26 October 1942. A few days later the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines moved to the Koli Point area, which Weapons Company, 7th Marines supported. However, I don’t recall seeing the flag at that time, 4–10 November 1942, nor do I recall seeing it again. . . . It is my theory that the flag was made to signify that any enemy attacking Charley Company was committing suicide.65

Private First Class Gilbert Lozier adds:

A few months after I was wounded [8 October], I ran into a C Company Marine at New Caledonia. He told me what had happened after I had left. That line we were holding was hit by a very large number of Japanese. Our Marines held on for a while, but the Japanese broke through. There was some hand-to-hand fighting in which several members of my squad were killed, but we were able to close the Japanese gain, and kill those who had gone through the gap. Sergeant Basilone was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions. This is where the term “Suicide Charley” started.66

Private First Class Clarence E. Angevine recalls seeing the guidon and gives a clue as to who might have painted it:

The man you are trying to find who made that flag is probably Phil South [Private Phillip South]. He was from Manhattan, Montana. One of the guys that was in on that flag deal name was Pokana. These guys were from the third platoon of the company and I was in the first platoon. Of course Company C was the one that got the brunt of that. That is what really started . . . “Suicide Charley” and all of the other things that went along with it. We didn’t get hurt too badly, but it made the guys have a lot of thoughts about they were sticking us out in the front all of the time. That was one of the reasons that all of this started. I did see one of those flags that was made out of a silk parachute. It was drawn on there. The only guy that I know that could really draw good was Phil South. He was an artist in a way. The last time I saw him was in the middle of the campaign on [Cape] Gloucester. He was evacuated and I never heard from him since.67

Earliest known photograph of the Suicide Charley guidon. TSgt William Wilander, the first sergeant of Company C, stands in front of the company command post in Korea, 1951. Wilander helped design the new guidon and sent the company property sergeant to Seoul to have it made. Photo courtesy of MSgt William H. Wilander, USMC (Ret)

Company C formation in Okinawa, 1987. Company 1stSgt Donald L. Fox served in Charley Company twice. As a young Marine in the early 1960s, he carried the Suicide Charley guidon. He returned to the battalion in the 1980s and became the company first sergeant. Photo from author’s collection

The Tradition Continues

The battalion next conducted offensive operations at Koli Point in November before withdrawing from Guadalcanal in December 1942 and deploying to Australia for recovery. The battalion fought next on New Britain, but the Suicide Charley guidon was not seen again until the bloody Battle of Peleliu (Operation Stalemate). During that time, a replica of the original guidon appeared briefly to inspire the tired Marines to victory.68

The symbol next appeared in Korea. While on rest and recuperation in Seoul, some members of Company C had a new Suicide Charley guidon made and proudly bore it back to the company. The guidon was carried throughout the conflict in Vietnam, and it then crossed the minefields into Kuwait in 1990–91, when Lieutenant Colonel James N. Mattis led 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, during Operation Desert Storm (First Gulf War). Company C bore the standard before them when they participated in humanitarian aid efforts in Somalia during Operation Provide Comfort (1991), and it was present in both Afghanistan and Iraq during Operations Enduring Freedom (2001–3) and Iraqi Freedom (2003).

The white Suicide Charley guidon has traveled the world with the company. The National Museum of the Marine Corps holds two versions in its collection, and replicas abound among the company’s former members.69 Today, the Suicide Charley guidon is carried in all formations, and Company C, 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, is better known to its Marines and those who know its history as Suicide Charley.70

Awards for Battle of Henderson Field

|

Name

|

Unit

|

Award

|

Date

|

|

Company C

|

|

|

1942

|

|

Sgt Archie D. Armstead

|

1st Battalion, 7th Marines

|

Navy Commendation Medal

|

24 October

|

|

PltSgt Robert L. Domokos

|

1st Battalion, 7th Marines

|

Navy Commendation Medal

|

24 October

|

|

MG William McK. Fleming

|

1st Battalion, 7th Marines

|

Navy Commendation Medal

|

24–25 October

|

|

Sgt John M. Kozak

|

1st Battalion, 7th Marines

|

Navy Commendation Medal

|

24 October

|

|

Sgt Edward Lewis

|

1st Battalion, 7th Marines

|

Navy Commendation Medal

|

24–25 October

|

|

GySgt Charles K. Livelsberger

|

1st Battalion, 7th Marines

|

Navy Commendation Medal

|

24–25 October

|

|

Capt Marshall W. Moore

|

1st Battalion, 7th Marines

|

Silver Star

|

24 October

|

|

1stLt Karl H. Schmidt

|

1st Battalion, 7th Marines

|

Navy Commendation Medal

|

24 October

|

|

PltSgt London L. Traw

|

1st Battalion, 7th Marines

|

Silver Star

|

24–25 October

|

|

PltSgt Simon Vigor

|

1st Battalion, 7th Marines

|

Navy Commendation Medal

|

24 October

|

|

Pvt Theodore G. West

|

1st Battalion, 7th Marines

|

Navy Cross

|

25 October

|

|

1stLt Arthur H. Wyman

|

1st Battalion, 7th Marines

|

Navy Commendation Medal

|

24 October

|

|

Attached to Company C

|

|

|

|

|

PltSgt John Basilone

|

Company D, 1st Battalion, 7th Marines

|

Medal of Honor

|

24–25 October

|

|

Pvt Billie J. Crumpton

|

Company D, 1st Battalion, 7th Marines

|

Navy Cross

|

24–25 October

|

|

Pvt Cecil H. Evans

|

Company D, 1st Battalion, 7th Marines

|

Silver Star

|

24–25 October

|

|

Pvt Sam Hirsch

|

Company D, 1st Battalion, 7th Marines

|

Silver Star

|

24 October

|

|

Cpl Noel L. Sharpton

|

Weapons Company, 7th Marines

|

Navy Commendation Medal

|

24 October

|

|

PFC Jack Sugarman

|

Company D, 1st Battalion, 7th Marines

|

Navy Cross

|

24–25 October

|

SERGEANT ARCHIE D. ARMSTEAD

Navy Commendation Medal

For devotion to duty during adverse conditions during engagements with the enemy from September to early December 1942. Throughout this entire period, Sergeant Armstead served with honor and distinction. On October 24th, he served as acting Platoon Sergeant in an especially commendable manner, with a platoon defense of the Lunga Area on Guadalcanal Island against an enemy force of superior numbers. The platoon was subjected to enemy fire from all enemy weapons and helped to repulse repeated enemy assaults. In his position of leadership, Sergeant Armstead, coolly and deliberately, without regard for his safety, assisted in directing the fire of his platoon, until his platoon leader was killed. Immediately he assumed the duties of his leader, serving with courage and skill, in addition to performing his own. By his intelligent action, he contributed greatly to the rout and virtual annihilation of a Japanese Regiment, which resulted in the Marine victory.

PLATOON SERGEANT JOHN BASILONE

Medal of Honor

The President of the United States of America, in the name of Congress, takes pleasure in presenting the Medal of Honor to Sergeant John “Manila John” Basilone, United States Marine Corps, for extraordinary heroism and conspicuous gallantry in action against enemy Japanese forces, above and beyond the call of duty, while serving with the First Battalion, Seventh Marines, FIRST Marine Division in the Lunga Area, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands, on the night of 24–25 October 1942. While the enemy was hammering at the Marines’ defensive positions, Sergeant Basilone, in charge of two sections of heavy machine guns, fought valiantly to check the savage and determined assault. In a fierce frontal attack with the Japanese blasting his guns with grenades and mortar fire, one of Sergeant Basilone’s sections, with its guncrews, was put out of action, leaving only two men able to carry on. Moving an extra gun into position, he placed it in action, then, under continual fire, repaired another and personally manned it, gallantly holding his line until replacements arrived. A little later, with ammunition critically low and the supply lines cut off, Sergeant Basilone, at great risk of his life and in the face of continued enemy attack, battled his way through hostile lines with urgently needed shells for his gunners, thereby contributing in large measure to the virtual annihilation of a Japanese regiment. His great personal valor and courageous initiative were in keeping with the highest traditions of the U.S. Naval Service.

Note: Platoon Sergeant Basilone was a member of Company D and was attached to Company C when he was awarded the Medal of Honor during the second Battle of Bloody Ridge on Guadalcanal.

PRIVATE BILLIE J. CRUMPTON

Navy Cross

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Private Billie Joe Crumpton, United States Marine Corps Reserve, for extraordinary heroism and devotion to duty while serving with a heavy machine-gun crew in Company D, First Battalion, Seventh Marines, FIRST Marine Division, during the action against enemy Japanese forces on Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands, on the night of 24–25 October 1942. When his squad leader and the remainder of his crew were killed or wounded during a mass frontal attack by hostile forces, Private Crumpton, although he, himself, was severely injured, gallantly stood by his gun and by maintaining effective fire, kept the enemy from penetrating the sector. Later, after his gun had been put out of action, he remained in an exposed position beside the disabled weapon and resumed fire with his rifle until wounds from exploding hand grenades forced him out of the fight. By his courageous devotion to duty and grim determination in the face of great danger, he contributed materially to the defeat and virtual annihilation of a Japanese regiment.

PLATOON SERGEANT ROBERT L. DOMOKOS

Navy Commendation Medal

For bravery and devotion to duty in an engagement with the enemy in the British Solomon Islands on October 24, 1942. The Company in which Platoon Sergeant Domokos was attached was assigned to the defense of a sector of the Lunga area, Guadalcanal. The enemy had forced a salient in the line. Sergeant Domokos took command of a small force of Marines and by his skill and courageous leadership succeeded in the line and annihilating the enemy forces which had penetrated it.

PRIVATE CECIL H. EVANS

Silver Star

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Silver Star to Private Cecil H. Evans, United States Marine Corps, for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity while serving with a heavy machine-gun crew in Company D, First Battalion, Seventh Marines, FIRST Marine Division, during action against enemy Japanese forces on Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands, 24 and 25 October 1942. When his squad leader and the remainder of his crew were killed or wounded during a mass frontal attack by hostile forces, Private Evans, manning his rifle from a dangerously exposed position, prevented hostile troops from overrunning the gun position until the disabled weapon could be replaced. His heroic conduct, maintained at great personal risk in the face of grave danger, was in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

MARINE GUNNER WILLIAM McK. FLEMING

Navy Commendation Medal

For devotion to duty under adverse conditions during engagements with the enemy in the British Solo- mon Islands from September to early December 1942. Throughout this entire period, Marine Gunner Fleming served with honor and distinction. He was serving as platoon leader on October 24 and 25 with the Marines in defense of the Lunga area on Guadalcanal Island when the enemy attacked with superior numbers. Without regard for his own safety, under severe enemy fire, and in the face of repeated enemy assaults, he displayed great courage and leadership. During the long hours of the attack, in rain and under darkness, he so skillfully lead his men that he contributed greatly to the rout and virtual annihilation of a Japanese Regiment, which resulted in a Marine victory.

Note: William Fleming received a field commission to second lieutenant and was later killed in action on New Britain.

PRIVATE SAM HIRSCH

Silver Star

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Silver Star to Private Sam Hirsch, United States Marine Corps Reserve, for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity while serving with Company D, First Battalion, Seventh Marines, FIRST Marine Division in action against enemy Japanese forces at Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands on October 24, 1942. During dangerous assaults against the main Lunga Defense line by a numerically superior Japanese force, Private Hirsch, despite the intense fire of enemy machine guns, mortars and rifles proceeded with courageous initiative to carry ammunition and spare parts from his company dump to machine gun positions in the forward area where such supplies were critically low. In addition, he fearlessly continued to load ammunition belts at the company dump, although exposed to the fire of infiltrating enemy groups. His heroic and intrepid conduct, maintained without regard for his own personal safety, contributed immeasurably to the ultimate success of our forces in this engagement and was in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

SERGEANT JOHN M. KOZAK

Navy Commendation Medal

For devotion to duty under adverse conditions during engagements with the enemy in the British Solomon Islands from September to early December 1942. On October 24 while serving as a platoon leader of a weapons platoon in defense of the Lunga area on Guadalcanal Island, Sergeant Kozak and his comrades were heavily engaged with an enemy force, vastly superior in numbers. Under severe enemy fire and in the face of repeated assault waves he coolly and deliberately, without regard for his own personal safety, directed and controlled fire of the machine guns of his platoon upon the enemy until the devastating fire of the Marines turned the battle into utter defeat and the virtual annihilation of an enemy regiment. By his skill and determination and his extraordinary heroism under enemy fire, Sergeant Kozak distinguished himself in the line of his profession and contributed greatly to the Marine victory.

SERGEANT EDWARD LEWIS

Navy Commendation Medal

For devotion to duty under adverse conditions during engagements with the enemy in the British Solomon Islands from September to early December 1942. While serving as a section leader of a weapons platoon in the defense of the Lunga area, Guadalcanal, the platoon was heavily engaged with an enemy force, vastly superior in numbers. The enemy was placing heavy fire from all of their weapons. Sergeant Lewis coolly and deliberately, without regard for his own personal safety, directed and controlled the fire of the machine guns of his section upon repeated assaulting waves of the enemy until the devastating fire of the Marines turned the battle into utter defeat and the virtual annihilation of an enemy regiment. By his skill and determination and his extraordinary heroism under enemy fire, Sergeant Lewis distinguished himself, in the line of his profession and contributed greatly to the Marine victory.

GUNNERY SERGEANT CHARLES K. LIVELSBERGER

Navy Commendation Medal

For devotion to duty under adverse conditions during engagements with the enemy in the British Solomon Islands from September to early December 1942. While serving as a platoon leader of a weapons platoon in the absence of a commissioned officer, in defense of the Lunga area, Guadalcanal Island, the platoon was heavily engaged with an enemy force, vastly superior in numbers. The enemy was placing heavy fire with all of their weapons. Gunnery Sergeant Livelsberger coolly and deliberately, without regard for his own personal safety, directed and controlled the fire of the machine guns of his section upon repeated assaulting waves of the enemy until the devastating fire of the Marines turned the battle into utter defeat and the virtual annihilation of an enemy regiment. By his skill and determination and his extraordinary heroism under enemy fire, Sergeant Livelsberger distinguished himself, in the line of his profession and contributed greatly to the Marine victory.

CAPTAIN MARSHALL W. MOORE

Silver Star

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Silver Star to Captain Marshall W. Moore, United States Marine Corps Reserve, for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity as Commanding Officer of Company C, First Battalion, Seventh Marines, FIRST Marine Division, in action against enemy Japanese forces at Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands, on the night of October 24, 1942. Despite continuous and dangerous assaults by a numerically superior Japanese force which was attempting to smash the Lunga defense lines, Captain Moore daringly commanded his men in maintaining our positions and repulsing the enemy. With utter disregard for his own personal safety, he led his company in brilliant and devastating counterattacks and contributed to the rout and virtual annihilation of an entire Japanese regiment. His indomitable fighting spirit and grim determination served as an inspiration to the men under his command and were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

FIRST LIEUTENANT KARL H. SCHMIDT

Navy Commendation Medal

For bravery and devotion to duty in an engagement with the enemy in the British Solomon Islands on October 24, 1942. The company to which Lieutenant Schmidt was attached was assigned to the defense of a sector of the Lunga area, Guadalcanal. The enemy had forced a salient in the line. Lieutenant Schmidt took command of a small force of Marines and by his skill and courageous leadership succeeded in reestablishing the line and annihilating the enemy force which had penetrated it.

CORPORAL NOEL L. SHARPTON

Navy Commendation Medal

For bravery and devotion to duty under adverse conditions during engagements with the enemy in the British Solomon Islands from September to early December 1942. Throughout this period Corporal Sharpton served with honor and distinction. During the engagement on October 24, the enemy attacked with a force of greatly superior numbers placing severe fire and making repeated assaults. Without regard for his own safety under these extreme conditions he continued to direct the fire of his gun and contributed greatly to devastating the enemy who were utterly defeated and virtually annihilated. By his courage and skill, he enhanced the Marine victory.

Note: Corporal Sharpton was a member of the 7th Marines Regimental Weapons Company. His 37mm gun was attached to Company C during the second Battle for Bloody Ridge.

PRIVATE FIRST CLASS JACK SUGARMAN

Navy Cross

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Private First Class Jack Sugarman, United States Marine Corps Reserve, for extraordinary heroism and conspicuous devotion to duty while serving with Company D, First Battalion, Seventh Marines, FIRST Marine Division, during action against enemy Japanese forces in the Solomon Islands Area on the night of October 24–25, 1942. During a mass frontal attack by a numerically superior enemy force, Private First Class Sugarman, with his gun temporarily out of action and his position threatened by hostile troops, removed the weapon and, with the aid of a comrade, repaired and place it back in action under heavy fire. On four separate occasions he saved the gun from capture, repaired it under fire and continued to maintain effective resistance against masses of attacking Japanese. By his skill and determination, he inflicted heavy casualties upon the enemy and helped prevent a breakthrough in our lines, which at that time, was weakly held by a small group of riflemen. His actions throughout were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

PLATOON SERGEANT LONDON L. TRAW

Silver Star

The President of the United States of America takes pride in presenting the Silver Star (Posthumously) to Platoon Sergeant London Lewis Traw, United States Marine Corps, for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity while serving with the First Battalion, Seventh Marines, FIRST Marine Division during action against enemy Japanese forces in the Lunga Area, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands on October 24 and 25, 1942. Undeterred by terrific enemy fire, Platoon Sergeant Traw coolly directed and controlled the fire of the machine guns of his section against repeated assaults of enemy forces greatly superior in numbers. The combat achievements of his platoon under his inspiring and courageous leadership contributed greatly to the rout and virtual annihilation of a Japanese regiment. He gallantly gave up his life in the service of his country.

PLATOON SERGEANT SIMON VIGOR

Navy Commendation Medal

For devotion to duty under adverse conditions during engagements with the enemy in the British Solomon Island from September to early December 1942. On October 24 while serving as a platoon sergeant of a platoon in defense of the Lunga area on Guadalcanal Island, Platoon Sergeant Vigor and his comrades were heavily engaged with an enemy force, vastly superior in numbers. While under heavy fire from all enemy weapons he coolly and deliberately, without regard for his own personal safety, directed and controlled the fire of his platoon upon repeated assaulting waves of the enemy until the devastating fire of the Marines turned the battle into utter defeat and the virtual annihilation of a Japanese Regiment. By his skill and determination and his heroism under enemy fire, he distinguished himself in the line of his profession and contributed greatly to the Marine victory.

PRIVATE THEODORE G. WEST

Navy Cross

The President of the United States takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Theodore Gerard West, Private, U.S. Marine Corps (Reserve), for extraordinary heroism and conspicuous devotion to duty while serving with Company C, First Battalion, Seventh Marines, FIRST Marine Division, during action against enemy Japanese forces in the Lunga Area of Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands on 25 October 1942. During a heavy attack by a numerically superior enemy force, Private West, although wounded to such an extent that he was unable to handle a rifle, remained in his position until reinforcements arrived, then rendered invaluable assistance by placing two rifle squads and directing their fire. His gallant action thereafter contributed materially to restoring our line and to the eventual rout and virtual annihilation of an entire Japanese regiment. His courageous devotion to duty, maintained for nearly seven hours after he was severely injured, was in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

FIRST LIEUTENANT ARTHUR H. WYMAN

Navy Commendation Medal

For bravery and devotion to duty in an engagement with the enemy in the British Solomon Islands on October 24, 1942. The company to which Lieutenant Wyman was attached was assigned to the defense of a sector of the Lunga area, Guadalcanal. The enemy had forced a salient in the line. Lieutenant Wyman took command of a small force of Marines and by his skill and courageous leadership succeeded in reestablishing the line and annihilating the enemy force which had penetrated it.

•1775•

Endnotes

*This account is based on primary source information provided by the members of Company C, who participated in the Battle for Henderson Field the night of 24–25 October 1942. The author’s personal papers concerning the history of Company C, 1st Battalion, 7th Marines (Suicide Charley), are located at the Archives Branch, History Division, Marine Corps University (MCU), Quantico, VA, hereafter Cozzens Personal Papers. The author would like to thank the late George D. MacGillivray, the late Marshall W. Moore, Angela Anderson, Roberta Haldane, Kara Newcomer, and Alisa Whitley for their assistance in preparing this article.

- George McMillan, The Old Breed: A History of the First Marine Division in World War II (Washington, DC: Infantry Press, 1949), 25.

- Stanley Coleman Jersey, Hell’s Islands: The Untold Story of Guadal- canal (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2008), 291.

- 7th Marines History: Traditions and Customs, 7th Marines Order 15750.1 (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, 1963). Note that the spelling on the original guidon (Charley) is used in this article rather than the traditional spelling (Charlie).

- The term guidon refers to a small flag, particularly one carried by a military unit as a unit marker.

- LtCol Frank O. Hough, USMCR, Maj Verle E. Ludwig, USMC, and Henry I. Shaw Jr., Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal: History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II, vol. 1 (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1958), 311.

- Marshall W. Moore to Gary W. Cozzens, 9 May 1986; and Company C, 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, Muster Roll (MRoll), October 1942, National Archives T-977, U.S. Marine Corps Muster Rolls, 1893–1958, Roll 0547.

- In an ill-conceived plan, Companies A and B were sent to the area near Koli Point via landing craft with Rogers in command. They walked into an ambush, and if Puller had not gotten them out, they would have been decimated. As a result of the action, Rogers was killed, Kelly became battalion executive officer, and Moore became Company C commander.

- Company C, 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, MRoll, 314–21; and Jersey, Hell’s Islands, 252

- Edson’s Ridge, better known for the Battle of Bloody Ridge, was named for LtCol Merritt A. Edson, commander of the 1st Raider Battalion.

- Richard B. Frank, Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle (New York: Penguin Books, 1992), 348–52; and Hough, Ludwig, and Shaw, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, 333.

- Platoon sergeant was a rank at this time equivalent to the modern rank of staff sergeant. Company C, 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, MRoll.

- Charles W. Kelly Jr. to Eric Hammel, 25 August 1980, Hammel Personal Papers, Archives Branch, History Division, MCU,

- Ibid

- Two of the guns were with Company A and one each with Company B and Company C. Crewmembers for the Company C gun included Sgt Carl A. Peterson, Cpl Noel L. Sharpton, Cpl Paul J. Plyler, PFC James Balog, PFC Floyd M. Gates, PFC George Mason, Pvt George A. Gottshall, and Pvt Keith Fullerton. George MacGillivray to Gary Cozzens, 14 October 1993, Cozzens Personal Papers; and Weapons Company, 7th Marines, MRoll, October 1942, National Archives T-977, U.S. Marine Corps Muster Rolls, 1893–1958, Roll 0547.

- Company A’s line was held by one platoon. Sgt Briggs’ platoon was placed at the combat outpost in front of the battalion lines, and one platoon was detached to Captain Kelly’s composite company. Burke Davis, Marine!: The Life of Chesty Puller (Boston: Little, Brown, 1962), 153; Col Jon T. Hoffman, USMCR, Chesty: The Story of Lieutenant General Lewis B. Puller, USMC (New York: Random House, 2001), 184; and Frank, Guadalcanal, 352–54.

- The cheval-de-frise is a defensive obstacle consisting of a frame covered with many projecting spikes or spears.

- Moore to Hammel; and Bill Sanford to Gary Cozzens, 17 May 1990, Cozzens Personal Papers.

- Moore to Hammel.

- Charles Ramsey to Gary Cozzens, 24 June 1990, Cozzens Personal Papers.

- Sanford to Cozzens.

- Zimmerman, The Guadalcanal Campaign, 118.

- Col Robert D. Heinl Jr., Soldiers of the Sea: The United States Marine Corps, 1775–1962 (Annapolis, MD: U.S. Naval Institute, 1962), 368.

- Robert Leckie, Challenge for the Pacific: Guadalcanal: The Turning Point of the War (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1965), 211.

- For a comprehensive account of Japanese actions, see Jersey, Hell’s Island, 281–93; Eric Hammel, Guadalcanal: Starvation Island (New York: Crown Publishers, 1987), 338–50; Frank, Guadalcanal, 346–48; and Hoffman, Chesty, 185.

- Frank, Guadalcanal, 352–35; and Hoffman, Chesty, 185.

- In Japanese, the term mukade refers to the centipede, which is what the Japanese soldiers called the ridge because of its shape.

- Kozaburo Miyazawa, “Diary,” SOPAC 0500 N-1:016467, Guadalcanal File, Archives Branch, History Division.

- Frank, Guadalcanal, 353–54; and John Miller Jr., The War in the Pacific: Guadalcanal: First Offensive, CMH Pub 5-3 (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, U.S. Army, 1995), 160–62.

- Davis, Marine!, 155; and Leckie, Challenge for the Pacific, 265.

- There is controversy over the exact time and date of the Japanese attack. The following references reflect the differences: official records put the initial attack at 2200 on 24 October 1942 in “Summary of Operations, 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, 24–25 Octo- ber 1942,” Reference Branch, History Division, MCU, Quantico, VA; shortly after midnight on 25 October in James S. Santelli, A Brief History of the 7th Marines (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1980), 11; at about 2200 on 24 October in Hammel, Guadalcanal, 348–51; at about 2130 on 24 October in Davis, Marine!, 152–55; at about 2200 on 24 October in Hoffman, Chesty, 186–87; at about 0030 on 25 October in McMillian, The Old Breed, 105–6; at about 0030 on 25 October 1942 in Zimmerman, Guadalcanal, 118; at about 0030 on 25 October in Hough, Ludwig, and Shaw, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, 333; and at about 0300 on 25 October in Heinl, Soldiers of the Sea, 368–69. These times may all be correct and may account for the different waves of the Japanese attack.

- Hammel, Guadalcanal, 346–57, 361–63; and Davis, Marine!, 155.

- Frank, Guadalcanal, 351–54; Hoffman, Chesty, 188–89; and Moore to Hammel.

- Hammel, Guadalcanal, 354–55.

- Ramsey to Cozzens.

- McMillian, The Old Breed, 106–7. For a thorough account of Basilone’s actions, see Hugh Ambrose, The Pacific: Hell Was an Ocean Away (New York: NAL Caliber, 2010), 117–24.

- Louis Maravelas to Gary Cozzens, 29 May 1990, Cozzens Personal Papers.

- Hammel, Guadalcanal, 352–53; and Davis, Marine!, 154.

- Hammel, Guadalcanal, 353–54; Davis, Marine!, 158; Hoffman, Chesty, 188; Frank, Guadalcanal, 355; and “Summary of Opera- tions, 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, 24–25 October 1942.”

- Mark Stille, Guadalcanal 1942–43: America’s First Victory on the Road to Tokyo (Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2015), 70–71; and Edward A. Dieckmann Sr., “Manila John Basilone,” Marine Corps Gazette 47, no. 10 (October 1962): 29–32.

- Kelly to Hammel; and Maravelas to Cozzens.

- “Theodore Gerard West,” Hall of Valor, Valor.MilitaryTimes.com; and Blakeney, Heroes, 115.

- “Summary of Operations, 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, 24–25 October 1942.”

- Kelly to Hammel.

- Miyazawa, “Diary.”

- Ramsey to Cozzens.

- The Marine squad included Sgt Edward Lewis, Cpl Mike Heinz, and Pvts Neal Lenz, Art Miller, Petrocco Edgar Petraco, Richard Zimmerman, and Charles Ramsey. Ibid.

- The USS Traw (DE 350), a destroyer escort, was laid down on 19 December 1943 and launched on 12 February 1944. It saw action in both the European and Pacific theaters.

- Kelly to Hammel.

- Wyman, Schmidt, and Domokos were awarded commendations for this action. George MacGillivray to Gary Cozzens, 8 September 1993, Cozzens Personal Papers.

- “Summary of Operations, 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, 24–25 Oc- tober 1942.”

- Foxfire is a naturally occurring phosphorescent glow created by a species of fungi as wood decays.

- Ralph Tulloch, “Guadalcanal Echoes,” Guadalcanal Campaign Veterans, January 1993, 7. Tulloch was meritoriously promoted to corporal for his actions this night.

- Hammel, Guadalcanal, 350; Davis, Marine!, 161–62; and Ramsey to Cozzens.

- Kamekichi Kusano, “Diary,” Item 867, Record Group 127, Entry 39A, Box 17, Captured Japanese documents, National Archives, Washington, DC.

- John E. Stannard, The Battle of Coffin Corner and Other Comments Concerning the Guadalcanal Campaign (Gallatine, TN: privately printed, 1992).

- Arthur Miller to Gary Cozzens, 26 November 1990, Cozzens Personal Papers; George MacGillivray to Gary Cozzens, 26 June 1990, Cozzens Personal Papers; and Richard Fisher to Gary Cozzens, 10 November 1990, Cozzens Personal Papers.

- Those killed were Sgt London L. Traw, PFC Victor I. Cooper, PFC James J. Nitche, PFC Peter M. Barbagelata, PFC Charles A. Andrews, Pvt George W. Hogarty, Pvt Marvin R. McClanahan, Pvt Arthur J. Picard, and Pvt Edgar Petraco. They were interred in the 1st MarDiv cemetery on Guadalcanal. See 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, Muster Report 33a, 26 October 1942, Archives Branch, History Division. For information on Marine burials on Guadalcanal, see Christopher J. Martin, “The Aftermath of Hell: Graves Registration Policy and U.S. Marine Corps Losses in the Solomon Islands during World War II,” Marine Corps History 2, no. 2 (Winter 2016): 56–64. Those wounded included Cpl James E. Weeks, PFC Tracey L. Anderson, PFC Roderick W. Cumming, PFC Dominico D’Alfonso, PFC Ralph J. Hicks, PFC Charles A. Poor, PFC Richard J. Rhoume, Pvt Henry S. Woodruff, and Pvt Theodore G. West. See 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, Muster Report 33a.

- “Summary of Operations, 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, 24–25 October 1942.”

- Mike Phifer, “Bloody Brawl on Guadalcanal,” Military Heritage, May 2016, 69.

- Marshall W. Moore to Gary Cozzens, 9 May 1990; and Billy R. Sanford to Gary Cozzens, 18 May 1991, Cozzens Personal Papers.

- Kelly to Hammel, 25 August 1980, Hammel Papers; Frank, Guadalcanal, 364; and Jersey, Hell’s Islands, 292.

- Award records are scattered and not well documented. Fleming was later killed in action on Cape Gloucester. See MacGillivray to Cozzens; and Blakeney, Heroes, 113, 98, 191, 180.

- 7th Marines History, 10.

- Richard Fisher to Gary Cozzens, 10 November 1990, Cozzens Personal Papers.

- Ralph L. Tulloch to Gary Cozzens, 29 November 1993, Cozzens Personal Papers.

- Gilbert Lozier to Gary Cozzens, 19 January 1993, Cozzens Personal Papers.

- No Marine named Pokana has been found on the October 1942 Company C muster rolls. Clarence Angevine to Gary Cozzens, 15 July 1996, Cozzens Personal Papers. Angevine was awarded the Navy Cross for actions on Cape Gloucester on 10 January 1944.

- 7th Marines History, 10.