PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

The U.S. Marines are known for having fought valiantly in World War I (WWI) in such situations as the Battles of Belleau Wood and Blanc Mont in France, where they earned a reputation for being tenacious and skillful warfighters. After the deadly skirmishes to drive out the entrenched German troops, Army General John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces, said, “The deadliest weapon in the world is a Marine and his rifle.”1 However, that belief didn’t stop Pershing, President Woodrow Wilson, and others from wanting to disband the Marine Corps after the war had been won and to absorb the Marines into the Army. Additionally, the Corps had to deal with the drawdown in numbers following WWI.

Major General Commandant John A. Lejeune understood that his Service needed to fight for survival in the political arena just as hard as it fought on the battlefield. Lejeune formulated a campaign to raise public awareness and increase support for the Marine Corps. The birthday of the Marine Corps, celebrated each year on 10 November, would easily serve as part of the public relations push by the Marine Corps to focus on its traditions, as could the major Marine elements tied to iconic battles or moments of Marine Corps history.2 This article highlights General Lejeune’s two pronged plan to improve the skills and abilities of the Corps by applying lessons learned to introduce new tactical doctrines and also to prevent the Service from being dissolved by raising public awareness about the Marine Corps.

“Instead of going to obscure places to conduct war games and learning lessons learned and learning how to integrate armor, artillery, and aviation into war fighting, he would do it at iconic places and put the Marines out in front of the public,” Gunnery Sergeant Thomas E. Williams said.3 At the time, the national parks and battlefields, such as Gettysburg, were still under control of the U.S. War Department, which meant the Marines could use them as a training ground.

General Smedley D. Butler assumed command of Marine Barracks Quantico, Virginia, at the end of June 1920 and is credited with the idea to stage exercises at these landmarks. He saw the reenactments as a hands-on way to teach Civil War tactical decisions and to focus positive public opinion on the Marine Corps.4

The Marines conducted four Civil War training exercises between 1921 and 1924. They reenacted the Battles of the Wilderness (1921), Gettysburg (1922), New Market (1923), and Antietam (1924). Of these, the event at Gettysburg drew the largest crowds and was the one that the Marines traveled the farthest to conduct. These events attracted attention across the nation, in part, because of the size of the group marching through towns and across the countryside. The Gettysburg Star and Sentinel called it the greatest military maneuver under the flag in a time of peace.5

President Warren G. Harding was invited to the 1921 exercises in Virginia. He witnessed the reenactment first-hand and walked along behind the Marines during the fighting. He told the Marines after a Sunday morning worship service:

It was suggested that I stand here before you mainly that we might be better acquainted. After all it is ours to serve together. I cannot tell you how inspiring it had been to sit in worship with you and how greatly I have enjoyed being in camp with you. I shall not exaggerate a single word when I tell you that from my boyhood to the present hour I have always had a very profound regard for the United States Marines, and I am leaving camp today with that regard strengthened and genuine affection added.6

General Lejeune’s efforts were already bearing fruit.

Marching to Gettysburg

Early in the morning of 19 June 1922, 5,500 Marines— roughly one-quarter of the Corps—left Marine Barracks Quantico. Four Navy tug boats towed eight large barges full of Marines up the Potomac River toward Washington, DC.7 Meanwhile, tanks and artillery pieces towed by trucks rolled out along the Richmond Road headed for the same destination.8

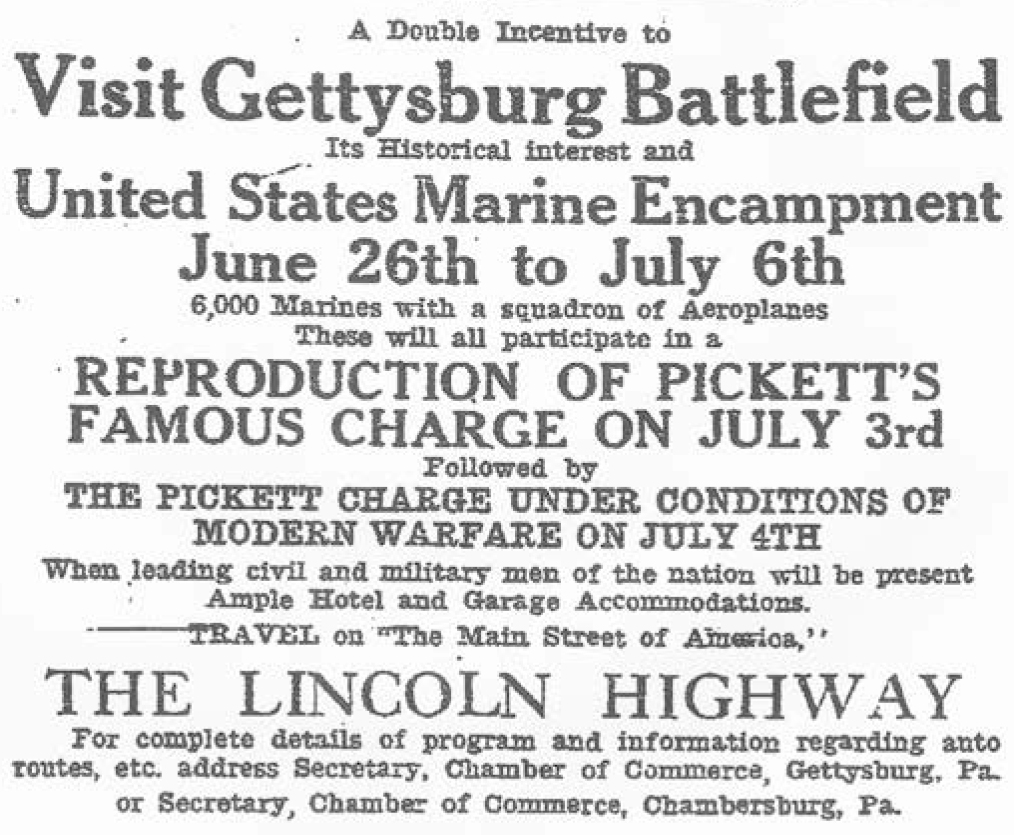

Promotional advertisement for the 1922 Marine encampment and maneuvers, developed jointly by the Gettysburg and Chambersburg chambers of commerce. U.S. Marine Corps Historical Company

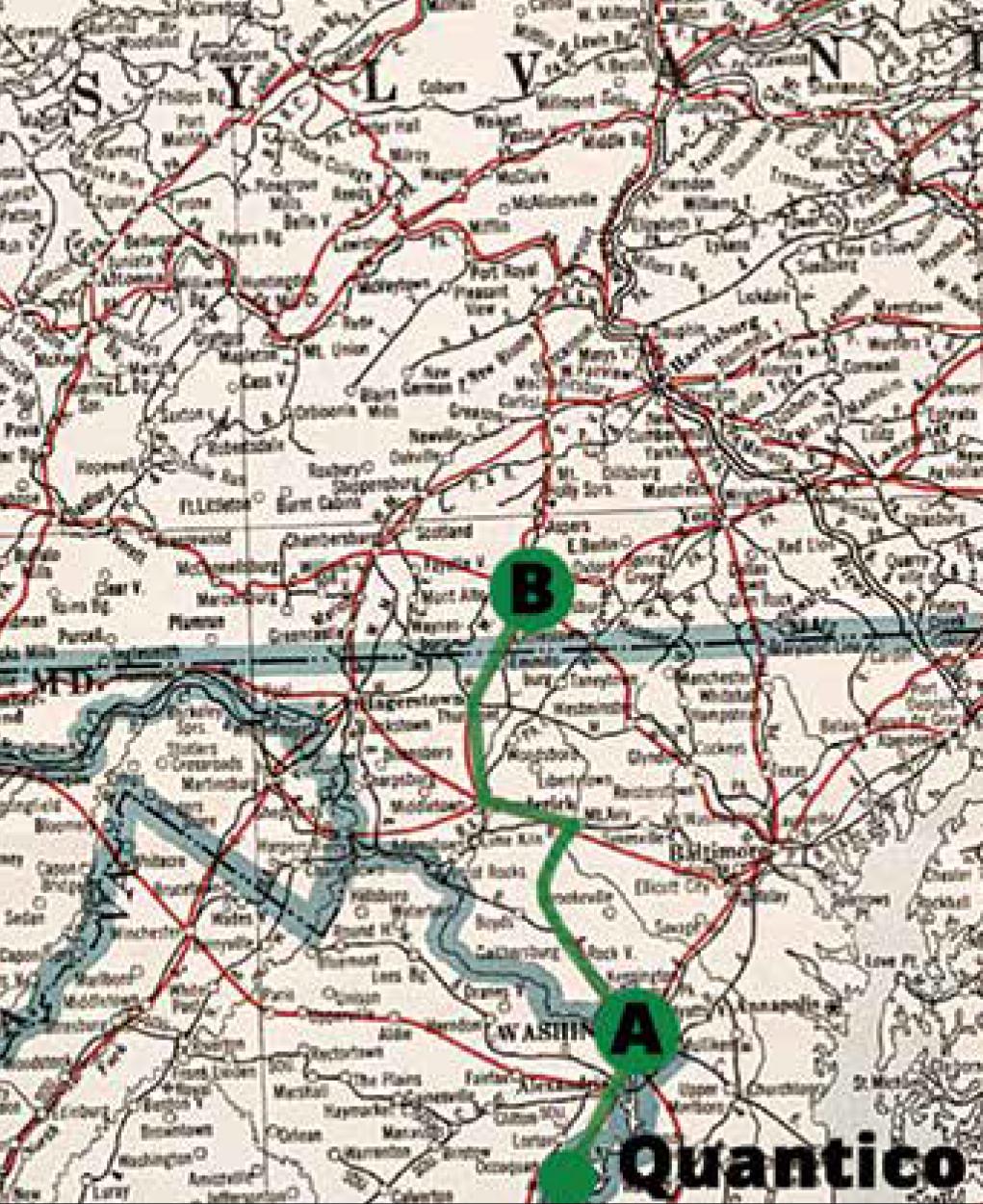

A map of the 1922 Marine Corps march to Gettysburg, PA. “A” marks Camp Lejeune in Washington, DC; and “B” marks Camp Neville in Bethesda, MD. Before reaching their final destination, they would pass through Camp Richards in Gaithersburg, MD; Camp McCawley in Ridgeville, MD; Camp Feland in Frederick, MD; and Camp Haines in Thurmont, MD.

The march involved the entire 5th and 6th Regiments, a squadron of the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, and elements of the 10th Marine Regiment Artillery.9 The Sun noted that these Marines were ready for anything and had cleared Quantico of everything that could be moved.10 Raymond Tompkins noted how “the 5,000 men are carrying the equipment of a complete division of nearly 20,000. In the machine-gun outfits especially the personnel is skeletonized, while the material is complete. Companies of 88 men are carrying ammunition, range finders and other technical gear for companies of about 140.”11

The Marines erected their first night’s camp in East Potomac Park, south of the Washington Monument. It was named Camp Lejeune, following General Butler’s practice of naming camps after prominent Marine Corps generals.

Once the camp was organized and the men fed, the Marines fell into formation and marched from the camp and through the East Gate of the White House around 1830. At the South Portico, President Harding, the first lady, General Lejeune, and other distinguished guests watched the Marines pass by as Harding returned the salute the marching Marines gave him. General Butler led the Marines in the review, but as he reached the portico, he left them and took his place with the other observers. It was the first time that troops had passed in review through the White House grounds since the Civil War.12

This event marked initial success in the Marine Corps’ efforts to influence the decision makers who held its future in their hands. President Harding, who had two planned meetings with the Marines on this march, would actually meet with them three times.13 Even after a long and arduous day, the Marines were still on the road by 0600 the next morning. “Although the hour was early as the force swung out of the Capital, a considerable crowd cheered the marchers as they passed from East Potomac Park to the route leading to Wisconsin Ave., and out,” the Washington Post reported.14

Marine Camp Lejeune at East Potomac Park, Washington, DC. Archives and Special Collections Branch, Marine Corps History Division

Marines passing in review in front of the White House on 19 June 1922. Library of Congress

The thousands of infantrymen marched along at roughly three miles per hour, while the artillery pieces and tanks traveled about twice that speed. Captain W. S. Shelby, an administrative aid to the District Police, estimated that walking eight abreast, it would take three hours for the Marine line to pass.15

The second day’s march was 12.5 miles and the Marine line stretched out for more than a mile along Rockville Pike in Maryland. At one point, the line of more than 5,000 Marines, 24 guns, and more than 200 trucks was reported to be two miles long.16

Each company had four Cole carts, which were piled high with the lower rolls of their packs. A pair of Marines pulled each cart for a distance before they switched with another pair. It was a rough time for Marines pulling the cart, but it lasted for only a short stretch of the march. “But by the time the fourth or fifth pair of men take their turn, they are normally tired with marching, and the pulling comes hard. And they say ‘The hills are hell’,” The Sun reported.17

General Lejeune reviewed the line along the march. The Marines stopped at the Charles Corby estate just outside of Bethesda at 1100 and set up Camp Neville in honor of Major General Wendell C. Neville. Once the setup was complete, local officials and some curious residents toured the camp. That evening, the Marines marched to the east end of the estate, which formed a natural amphitheater. There, the troops enjoyed a cartoon on the screen set up for their entertainment and then watched themselves in the Washington, DC, march from the day before. The Marine Photographic Section had filmed the Marines, and the Navy Aviation Photographic Unit then developed and rushed the film to the Corby estate to be viewed. “It is the first time on record when a force on the march has taken its own moving pictures and seen them exhibited within 24 hours. The show greatly pleased the men and was also viewed by members of the Corby family and several nearby residents,” the Washington Post reported.18

The Marines invited the public into their encampments to meet the men and see their equipment. It was one more way the Corps began garnering public support. The march was not specifically described to the public as an effort to save the Service, but that was the effect. And the public did turn out. Hundreds of people visited the encampments and thousands lined the route along which the Marines traveled.

The following day, 22 June, the East Coast Expeditionary Force once again broke camp and headed north toward Gaithersburg, Maryland. This day’s march was 12 miles long. As in many towns along the route, residents turned out to watch the largest military procession seen in their lives pass by their homes and businesses. The Marines tried to give them a good show, singing as they marched along the roads.

“It seemed that every one was out to see the troops in Rockville. Front porches were filled with people, clerks watched from stores, and business was suspended excepting what was done to serve the men as they took the opportunity to quench their thirst or replenish the supply of tobacco or cigarettes. Water bottles were filled and many kinds of residents delighted in throwing fruit to the men who rested along the curb,” the Washington Post reported.19

While the first two days of the expedition had been easy marching, the third day marked the start of the Marines’ training exercises. They sent out scouts and proceeded as if they were in a hostile environment. The exercise was to assume that a hostile force had captured Gaithersburg and the railhead. It was the Marines’ job to free the town and its residents. “Warily and in scattered detachment, preceded by skirmishers and advance guards who would ‘clean out the enemy’ in the roadside woods. The ‘enemy’ had their American flags hanging out and ‘sniped’ the [M]arines with apples, oranges, drinks of water and bottles of milk,” the Washington Post reported.20

Around noon, the scouts made contact with a supposedly hostile army advancing toward the Marine column. Airplanes dropped messages to Marines on the ground and they reacted as if they were in an actual hostile situation. “Fighting imaginary foes is the ‘Gyrenes’ idea of something to do on a quiet evening at home when one is tired of bridge and knitting. The United States [M]arine is not an enthusiastic shadow boxer. He likes to feel a wallop land,” according to The Sun.21

The exercise lasted for about two hours and the Marines finished their march to erect Camp Richards, named for Brigadier General George Richards, about two miles north of Gaithersburg. Once the camp was set up, the Marines spent the afternoon and next day playing baseball games against American Legion teams from Gaithersburg and Ridgeville, Maryland. News of the games spurred Corps pride as odds were offered on the outcomes.22

Marines enter Frederick, MD, on their way to Gettysburg. This photo is frequently printed in reverse, but the side on which the Marines are wearing their equipment and the mileage sign indicate this is the proper orientation. U.S. Marine Corps Historical Company

Marines march along North Market Street in Frederick, MD, on their way to Gettysburg U.S. Marine Corps Historical Company

The first casualty of the trip occurred Thursday, 22 June, when a truck ran over a Marine’s foot. Another potential casualty was avoided when Marine pilot Captain George W. Hamilton made a rough but safe landing in his plane upon returning from Quantico.23 On Friday, 23 June, the Marines marched 15 miles to Ridgeville.24 They left the next morning, marching east along the National Pike. The first Marines began arriving in Frederick at 0900, but the bulk of the group arrived around noon. By then, streetcars were carrying signs throughout the city announcing that the Marines had arrived at the fairgrounds.25 The Marines were greeted with flags hanging from windows and thousands of people lining the road into the city. Once the Marines were encamped at Camp Fe- land, Frederick Mayor Lloyd C. Culler led a delegation out to the fairgrounds to greet them. Culler urged General Butler to stay through Sunday, but the general insisted the schedule had to be kept. However, he did invite any Civil War veterans in Frederick to be special guests of the Marine Corps at Gettysburg.26 Butler attended a chamber of commerce dinner in nearby Braddock Heights, Maryland, as their guest of honor.27

Marines entering Thurmont, MD, on 25 June 1922. Robert S. Kinnaird Collection of Historic Thurmont Photographs

Marines moving through Thurmont, MD, to Camp Haines on 25 June 1922. Robert S. Kinnaird Collection of Historic Thurmont Photographs

That evening, the public enjoyed concerts from the expeditionary Marine Corps Band, and then later the Marines settled down to watch movies before turning in for the evening. All of these events served as increased public relations for the Marines. They made friends, and in doing so, drew positive press, not only from the newspapers along their travel route, but newspapers all over the country.

The Sabbath saw no rest for the Marines. In fact, it would be the longest day of marching for the entire journey. They marched 18 miles north to reach Thurmont, Maryland. It also turned out to be the hottest day of the event. The Marines had been singing when they left Frederick, and they were singing as they entered Thurmont and the last mile of the hike around 1345.28

“Everyone from the small boy to the aged veteran was up and out to await and see the soldiers. Sunday School and church attendance suffered severely, and no doubt the few who did attend wished they were out on the street. Many persons remained in town preferring to miss their dinners rather than miss seeing this great military outfit arrive. Every porch along the State Road was crowded with people watching the passing trucks,” the Catoctin Clarion reported.29 By 1430, the Marines marched into a clover field about a mile north of Thurmont and sat down. Camp Haines, named in honor of Brigadier General Henry C. Haines, had been erected on the Hooker Lewis Farm for them.

The next morning, 26 June, the Marines made their final 15-mile march to Gettysburg, settling in at Camp Harding, near the base of the Virginia Memorial on the Gettysburg battlefield.

Camp Harding

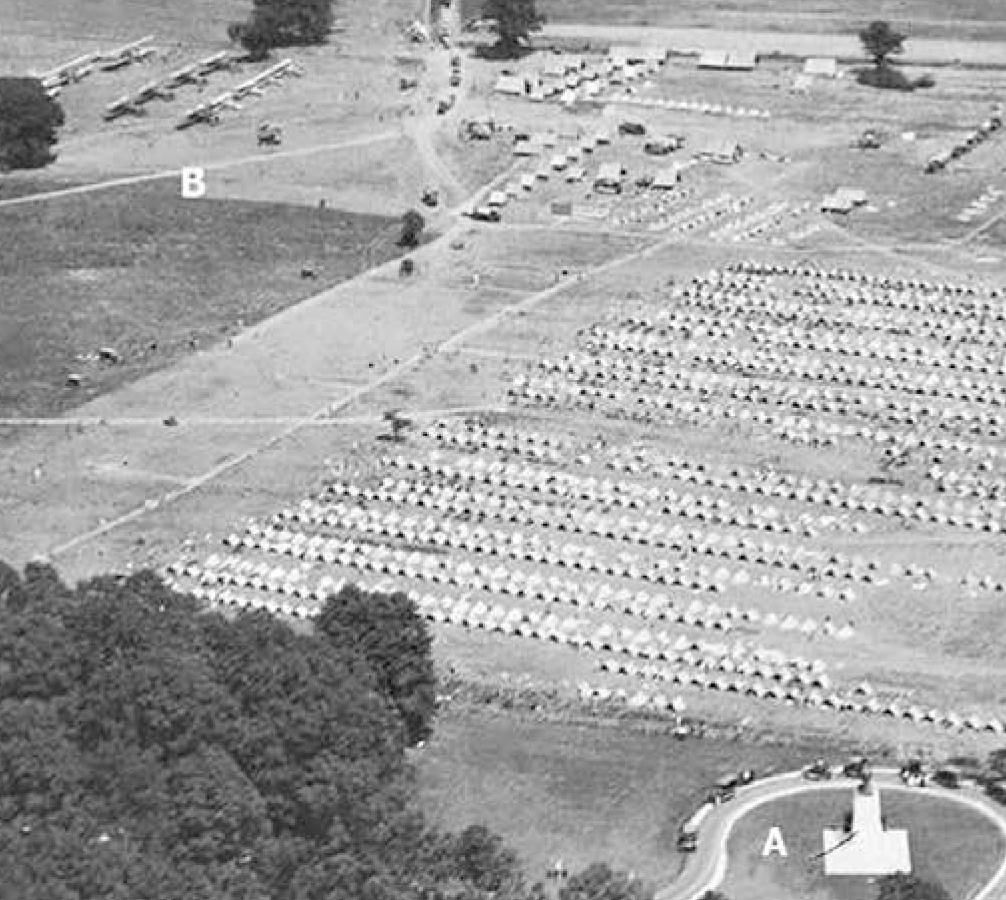

An area between Emmitsburg Road and West Confederate Avenue, adjacent to Seminary Ridge, was designated for Camp Harding, named in honor of President Warren G. Harding. By naming the camp after the president, it not only showed respect for the commander in chief, but it also curried favor from a man whose support was needed to keep the Marine Corps strong. Even before units of the Marine East Coast Expeditionary Force left their base of operations at Quantico, along with approximately 1,000 pieces of motorized equipment, work had commenced on Camp Harding. As early as 19 June, local plumber A. B. Plank, who had been awarded the encampment water and sewer contract, began working on water supplies to ensure that the 300 showers being installed in two bathhouses, also under construction, received an adequate supply of water.30

On 27 June, the Signal Corps established radio contact with Washington, New York, Philadelphia, and the Marine Corps barracks at Quantico and set up a radio network throughout the encampment to allow officers and staff to communicate with each other on-site, as well as to communicate with various aircraft being used.31

The Marines pass through the Emmitsburg Town Square, MD, on their way to Gettysburg on 26 June. Courtesy of the Town of Emmitsburg, MD

Camp Harding at Gettysburg, PA. U.S. Marine Corps Historical Company

The Canvas White House as it appeared without the additional tentage for male and female guests. U.S. Marine Corps Historical Company

The Gettysburg Times noted that the connections with Quantico did more than allow radio communications between the Gettysburg battlefield camp and the Virginia headquarters. “The feat established a new record for speed in long distance radio communication, as the points were reached within a half hour after the work of establishing the large system . . . had been started.”32

The Marines on-site also provided the encampment with its own phone service setup for the troops and their command, with lines also being connected to those of the Bell Telephone Company to enable “outside” calls. The phone system as installed conceivably made it possible for the encampment to have its own unique telephone exchange.33 The final size of the encampment was reported by various newspapers to have been from 65 to 100 acres.34

The Canvas White House

Due to the planned stay of President Harding and his wife, Florence, in the Marine encampment for a portion of the military demonstrations and reenactments at Gettysburg, a structure was erected for the couple, as well as for use by members of the presidential entourage.

The so-called Canvas White House (or Gettysburg White House) was not merely to provide a showpiece for the event or to serve solely as convenient quarters for the president and dignitaries at the maneuvers, though it certainly was all those things as well. The Baltimore Sun reported, “It will house the President and Mrs. Harding . . . [and] the office force he brings along to keep the executive department of the Government going . . . so that the country may progress as rapidly, while ‘Pickett’s Marines’ are charging as it does in Washington.”35

The Gettysburg Times described the presidential compound as “one of the most elaborate quarters ever provided the President of the United States in any camp.” The Sun compared the appearance of the canvas presidential complex at the encampment site to “a magic castle in the wilderness.”36

The entire tent complex of the presidential compound formed a semicircle, fronting a semicircular drive. The completed nine-structure complex of canvas and wood was 400 feet in length and 175 feet in width and comprised 16 rooms. Initially, the finished compound was to have been painted white, but that plan was amended sometime around 29 June.37

Gen Smedley D. Butler, President Warren Harding, Gen John J. Pershing, and MajGen Commandant John A. Lejeune in front of the Canvas White House. Harris & Ewing Collection, Library of Congress

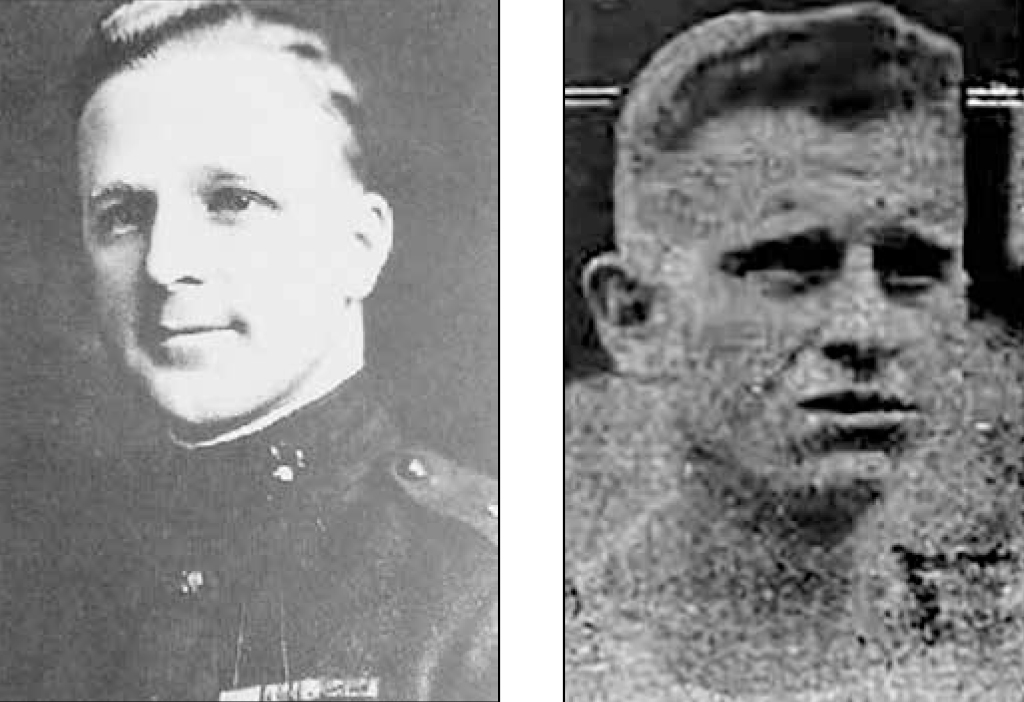

Left: Capt George Hamilton. Right: GySgt George Martin in the Buffalo (NY) Evening News, 27 June 1922. U.S. Marine Corps Historical Company

Three buildings flanked each side of the main presidential structure, each a combination of reception area and bedroom, and were intended for the men in the presidential entourage. At the end of each row of three sat a larger structure, each with living rooms and bedrooms, which were intended for the women in the presidential group.38

The interior walls and ceilings of the Canvas White House were covered with plasterboard and other materials, mainly to conceal such structural elements as bare studs and rafters.39 The presidential compound was well lit, with the electricity provided by on-site generators. The generators not only provided enough power for the interior lighting that had been installed in the two-dozen rooms of the complex, but also for “long lines of incandescent bulbs” outside along the frontage of the compound tents.40

The Canvas White House was “officially” completed on 29 June with the installation of six porcelain bathtubs, which had been flown in “strapped to” Martin MBT twin-engine bomber/torpedo planes and “flown over the mountains to Gettysburg,” The Sun reported; the article further noted the concern that the heavy porcelain bathtubs could be damaged during overland transport, that “these are the first bathtubs ever carried by airplane, it is believed.”41

A Tragic Beginning

On 26 June, the celebratory arrival of the Corps was marred by the deaths of Marine aviator Captain George Wallis Hamilton and Gunnery Sergeant George Russell Martin.42

Captain Hamilton was in command of a squadron of fighters providing simulated “scout duty” while escorting the Marine infantry. Captain Hamilton, along with Gunnery Sergeant Martin, were flying a De Havilland DH-4B biplane fighter at the rear of the squadron of four planes as they left their encampment at Thurmont, Maryland, shortly afternoon on 26 July and proceeded north.43

Nothing amiss among the planes was noticed until the squadron approached the landing field at Camp Harding. Two of the planes landed safely in the fields near the intersection of Long Lane and Emmitsburg Road.44 Eyewitnesses then saw Captain Hamilton’s plane go into a nosedive that developed into a tailspin that brought the plane crashing into the ground.45

Aviation magazine reported, According to Capt. John Craige, Aide to General LeJeune, who had just stepped out of a Marine Corps plane when he heard a formation of five planes overhead, Captain Hamilton, the leader in a DH4 signaled that he was about to land and cut his engine. From a height of about 500 ft. the plane went into a slow spin from which the pilot was seen to partially regain control, apparently about 100 feet from the ground.46

Leatherneck reported, “As the crippled plane descended, at a rate of approximately 200 miles an hour. . . [it impacted the crash site,] striking the ground at an angle of 45 degrees. Several hundred persons witnessed the fatal plunge.”47 The plane crashed on the William Johns farm at approximately 1305 in the afternoon and within 50 feet of tents and equestrian equipment belonging to Lew Dufour’s Exposition, which had set up along Steinwehr Avenue.48

The Star and Sentinel reported that Martin was pulled from the wreckage, alive but bleeding heavily from a head wound. Hamilton was found deceased within the wreckage. Both men were rushed to Warner Hospital in Gettysburg, though Martin died shortly after reaching the hospital.49

Leatherneck stated in its report of the event, In the opinion of the accompanying aviators, the accident was due to the difference in the reading of the altimeter, by which fliers estimate their distance from the ground, at Quantico and Gettysburg. Quantico is on sea level, while Gettysburg is 600 feet above sea level. Consequently, when the altimeter reads 1,000 feet at the latter place, the actual distance is only 400 feet.50

Hamilton and Martin were listed as killed in the line of duty in the service of their country, and the deaths of the two Marines may be the only military deaths that have occurred on the Gettysburg battlefield since 1863.51 Marine officers believed Hamilton tried his best to avoid the crowds at the carnival, knowing his plane was in trouble. According to the Gettysburg Times, the aircraft could have struck the carnival if Hamilton had continued to maneuver the plane out of its plunge toward the earth, and that could have led to many more deaths.52

An Educational Process

To properly portray Pickett’s Charge, the commanders of the expedition felt that it would be necessary for the soldiers to know the particulars concerning the events that had occurred on the grounds 59 years earlier.

The Sun reported that “Brig.-Gen. Smedley D. Butler is determined that his men shall know the real history of the battle of Gettysburg before they fight it again. They will be handicapped . . . by an official guide battalion that has found the battle of Gettysburg commonplace and has trimmed it up to suit modern tourists.”53 On 28 June, two battalions of Marines toured the battlefield aboard 20 trucks, with an “official guide” in each. These educational tours were conducted leading up to 1 July.54

Since most of the Marines would be portraying Confederate forces in the upcoming reenactments of Pickett’s Charge, the color of their brown uniforms could readily pass as butternut, the same color of the uniforms worn by some Confederate units, which had been achieved by dyeing cloth with oil from the bark of the butternut tree.55 With that, half of the clothing battle was essentially won by default. However, half was not enough for the U.S. Marine Corps. The Marines were already accustomed to carrying blanket rolls on campaign marches, so they merely used these rolls for Confederate reenactment purposes as well.

Field officers also spent time studying the Battle of Gettysburg Cyclorama to get an overview of how the grand spectacle of Pickett’s Charge may have looked. The immense, panoramic painting was executed by artist Paul Dominique Philippoteaux and his assistants, with the finished product first exhibited in Chicago in 1883.56

Battle for Herr's Ridge

The Marines scrambled sometime before 1100 on the morning of 29 July for an impromptu call to arms. Orders were passed down indicating that “flank and advance guard [of the enemy] had seized Seminary Ridge from the Chambersburg road to the sharp bend in West Confederate avenue.” Units from the 6th and 10th Regiments attacked and seized McPherson’s Ridge at 1100.57

The enemy consisted of a regiment of infantry and a battery of 75mm cannons that represented the defensive position on Herr’s Ridge. As they were driven off McPherson’s Ridge, the men fell back west of Willoughby Run and established a defensive position along Herr’s Ridge. Aircraft were deployed to conduct reconnaissance, patrolling the enemy-occupied territory between Herr’s Ridge and Cashtown northwest of Gettysburg.58

This was a no-holds-barred exercise, as reflected in the details of the unfolding engagement in the newspaper:

The attacking forces are accompanied with all auxiliary arms, field rations for one day, being maintained at all railheads. The Marine Quartermaster Corps have been ordered out as a salvage squad, assisted by the Engineers. The Sanitary Inspector will attend to the proper burial of all “casualties” while two Chaplains are detailed to look after the burial and keep records of the men killed.59

A battalion of Marines from the 5th Regiment was posted in the area of Lincoln Square to serve as reinforcements. Radios were deployed and telephone lines laid by the Signal Corps to allow all of the units to stay in touch with the command, the other units involved, and even the airplanes overhead. Even the “big ears” were set up to monitor the sky for any sign of enemy aircraft.60

Aside from concluding the fight for Herr’s Ridge, the commanders at the encampment managed to inject a few more rehearsals of the charge into an otherwise busy schedule of finishing final touches to the camp and preparing for the presidential visit, along with dozens of federal and state dignitaries, foreign dignitaries and emissaries, and tens of thousands of spectators.

The President Arrives

President Harding and his entourage of more than 40 members of his staff, Secret Service, and select reporters left Washington shortly after noon on Saturday, 1 July.60 For the Hardings, it was the beginning of a weeklong vacation. The presidential party also included the first lady, General Pershing, retiring budget director Charles G. Dawes, Army Medical Corps Brigadier General Charles E. Sawyer (who served as the president’s personal physician), and the president’s personal secretary, George B. Christian Jr.

As the president and his entourage arrived in front of the Canvas White House, artillery provided a 21-gun salute.61 The president inspected the camp with General Butler and then returned to the Canvas White House to prepare to watch the Pickett’s Charge reenactment, which began at 1700 that evening. The group watched from a vantage point in an observation tower on Cemetery Ridge to get the full sweep of the historical reenactment that lasted less than an hour. Following the excitement of the afternoon, the president and his party were guests at a dinner in their honor in the Marine camp.

A view of Pickett’s Charge as presented by the Marines. U.S. Marine Corps Historical Company

The Battle is Joined

An estimated 100,000 spectators turned out to watch the reenactment. The Star and Sentinel reported, “For miles on the front and either flank of the territory over which the charge was made, as well as from other points of vantage, including the Round Tops, a great throng of people, who motored here from nearby sections of the country, witnessed the pageant.”62

At approximately 1700, “candles” were set off to provide a smoke screen signal for the Confederate artillery barrage to begin. Two of the Confederate 75mm guns fired, representing the opening barrage of the artillery “concealed” in an artillery park on Seminary Ridge. A number of the 75mm guns also were placed along Cemetery Ridge and around Little Round Top to represent the federal artillery.63

“At 5 o’clock little clouds of white smoke jetted up from the ground under the far off trees,” The Sun reported. “Off to the left they started first, then spread out toward the west in a solid white line, until the line seemed lost in the distance. It grew thicker and thicker, rising until it hid the trees. Suddenly red flashes split through the white wall, and next second the boom of a gun rolled across the mountain.”64

The guns were then rolled forward by hand from the artillery park behind Seminary Ridge until they were standing hub-to-hub along the period smooth-bore guns of the Confederate Army on West Confederate Avenue. This placed them approximately 1,400 yards from their intended targets on Cemetery Ridge. When the artillery commenced firing, “the recoil of the 75mm guns shook the earth.”65 George Chandler wrote that the 75mm howitzers also used black powder rounds to add to the effect of the “fog of war” on the field and to provide an authentic appearance to the battle reenactment.66

The opening barrage represented a 30-minute version of the 1863 duel in which Confederate Colonel Edward P. Alexander, commanding General James Longstreet’s reserve artillery, was ordered to direct the opening of a two-hour barrage of 140 Confederate cannon aimed primarily at the center of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge, as a prelude to Pickett’s Charge. Witnesses claimed, “Faster and faster the flashes of red came through and quicker and quicker the artillery thunder rolled over the fields, until it sounded like the beating of drums. Guns roared both ways across the field now. Puffs of smoke leaped out from the Round Tops on the left of the Union Line and from Cemetery Hill on the right. The flashes along Seminary Ridge persisted.”67

U.S. Marines reenact Pickett’s Charge using flags to help spectators identify which Confederate units are being represented. U.S. Marine Corps Historical Company

When the half-hour barrage subsided, the Marines representing the Southern advance began, preceded by a skirmish line of sharpshooters that was deployed about 20 paces in front of the battle line. To aid spectators in keeping track of the units on the field, the Confederate regiments carried white and red Army signal flags as their respective battle flags, while the names of the generals who were represented in the charge were written in white on blue cloth.68 At first, there was so much smoke on the field from the smoke candles and the artillery rapidly firing black powder-filled rounds into the air that the advancing Confederate battle line was not easily discerned. When they were spotted in the haze, spectators said it appeared the ghosts of soldiers past had returned out of time itself and onto the battlefield. “Then they began to move forward . . . and for the watchers there was a thrill as though the ghosts of Pickett’s men were massed once more for another try for victory [T]here were six lines of men stretching along a mile front,” one reporter wrote.69 The Gettysburg Times noted, “In spectre [sic] like form, it seemed, as the figures were dimly outlined through the dense smoke of battle, that the soldiers of the Confederacy had actually come back and were reenacting that charge which proved fatal to the cause of the Southern States.”70

The Confederate Marines advanced shoulder-to-shoulder, nineteenth-century style, until they reached the Emmitsburg Road, where they must then address surmounting the fencing that represented the last obstacle in their path to the High Water Mark.71 The Sun reported that

Now the crackling of rifles was a steady chorus, and the men were plainly living figures. They fell upon the fence in clouds, like mobs of insects alighting, firing furiously. Some toppled over the fence, fell headlong in the road and lay there. Some went suddenly limp across the top rail and hung like clothes drying in the sun. But the mass of them went over, crossed the road, climbed the next fence and were at the foot of the knoll.72

Some of the advancing troops also had been provided with shotguns loaded with black powder rounds that they would fire toward the ground as the troops progressed to simulate artillery shell explosions. The Marines in the vicinity of the “explosions” would then fall “dead” or “wounded” around the detonation produced.73

After crossing the Emmitsburg Road, the Marines continued on toward the stone wall that comprised the High Water Mark of the Battle of Gettysburg at the crest of Cemetery Ridge. However, before the advance continued, a portion of the Marines charged the Codori homestead on the east side of the road, routing an army of chickens. “Chickens on the farm, terrified by the sudden appearance of these khaki-clad figures and heavy rifle fire, flew in all directions for safety,” the Star and Sentinel reported.74

At 1720, the climactic storming of “The Angle” began, led by Major William P. Upshur, portraying Confederate General Lewis A. Armistead.75 As the final moments played out, The Sun reported that “the din of firing was fearful. From the far-off woods on Seminary ridge the cannonade had almost ceased, but from all around . . . the Union guns now roared a thunderous chorus. Then came the ‘rebel yell’ and the last rush. They were at the stone fence, in a yelling, shooting mass. The Confederates were at the Bloody Angle again.”76

Upshur placed his hat on his sword, led his Marines over the wall, and was subsequently “mortally wounded,” falling beside one of the Union guns in the battery at a crucial angle in the Union defense. The collision of the Confederate Marines with those representing the Union seemed so realistic that those observing the attack from immediately behind the Union line began to retreat as well. “As the attackers crossed the wall with all the enthusiasm and fury of real battle, the crowds of people who lined Hancock [A]venue, to view the event, instinctively fell back as before a real foe,” the Star and Sentinel reported.77

The charge, having reached the maximum point of penetration of the Union line, had ended, and the hundreds of “wounded” Confederates made their way across the fields they had previously charged across to assail the enemy position on Cemetery Ridge. “A shivering yellow pup, with tail tucked into its dragging belly, crept to the side of one of the fallen [M]arines who lay spraddled [sic] out with his closed eyes to the sun,” the New York Tribune reported. “The pup licked his face sympathetically once, twice, then the stricken ‘Confederate’ leaped to his feet and rejoined his fighting but now retreating comrades.”78 Then the fields suddenly fell silent as “a bugle was sounded from the High Water Mark, which called the ‘dead’ and ‘wounded’ to arise . . . [followed by] loud applause, from all sections of the large fields, greeted this ‘awakening’ of the dead.”79

By 0930 on the morning of 2 July, the president and his party left Gettysburg for Marion, Ohio, the president’s hometown. He would spend the next few days there celebrating the town’s centennial anniversary.

The Grand Finale

The Fourth of July represented the grand finale, for all intents and purposes, to the more-than-week-long training and battle demonstration campaign around Gettysburg. The focus of the day’s warfare was a presentation of Pickett’s Charge as if it had been fought in 1922 and, for a welcome change, the weather seemed to be predominantly on the Marines’ side.

The Marines held nothing back regarding the equipment they had hauled up to the Gettysburg battlefield, including the airplanes and howitzers previously used, as well as hydrogen-filled observation balloons, tanks, machine guns, antiaircraft guns, monitoring devices, radio communications, and mortars. The fury began around 0900, when spectators saw an observation balloon ascend to approximately 2,000 feet. The balloon hovered above the Marine camp to represent a Confederate observation craft. As soon as all the balloons were aloft, artillery posted on Seminary Ridge fired. The purpose of the balloons was to ascertain the effect of the rounds being aimed at the enemy positions.80 A squadron of four enemy planes, representing Union aircraft, suddenly appeared above Cemetery Ridge to defend the forces located there. And just as quickly, two squadrons of fighters representing Southern forces rushed up and toward the enemy planes, which were soon engaged in a dogfight, “in which nose dives, spins, loops, Immelman turns and other war maneuvers of fighting aircraft succeeded each other in rapid succession, while bursts of machine gun fire from aloft told when a pilot has succeeded in securing a deadly position on the tail of some other craft,” the New York Tribune reported.81 One of the enemy Union planes suddenly broke off and dove at the targeted observation balloon: “Speeding like an angry wasp straight at the big ‘sausage,’ it veered away and circled the balloon with a ‘tat- tat-tat’ of machine gun fire. Then it headed back to join its fellows.”82 The assault on the balloon was brief but fatal. Flames appeared and then spread rapidly throughout the craft, which had been inflated with a “half-million cubic feet of hydrogen gas.” A dummy, it was generally reported, wearing a parachute was cast forth from the observation basket attached to the underside of the balloon, while a second figure fell to the earth without a chute. As the burning balloon fell somewhere on the west side of Seminary Ridge, along with the slowly descending “parachutist,” the crowd stood stunned, some believing that the figures were actually people, and that one of them had fallen to certain death.83

The Sun reported that, unbeknownst to the many spectators, the fire and discharge of the occupants of the basket had been controlled from the ground via wires, one of which was electrified to ignite the balloon. The Sun also reported that there were two observation balloons aloft, only one of which was sent up to serve as the one slated for destruction.84

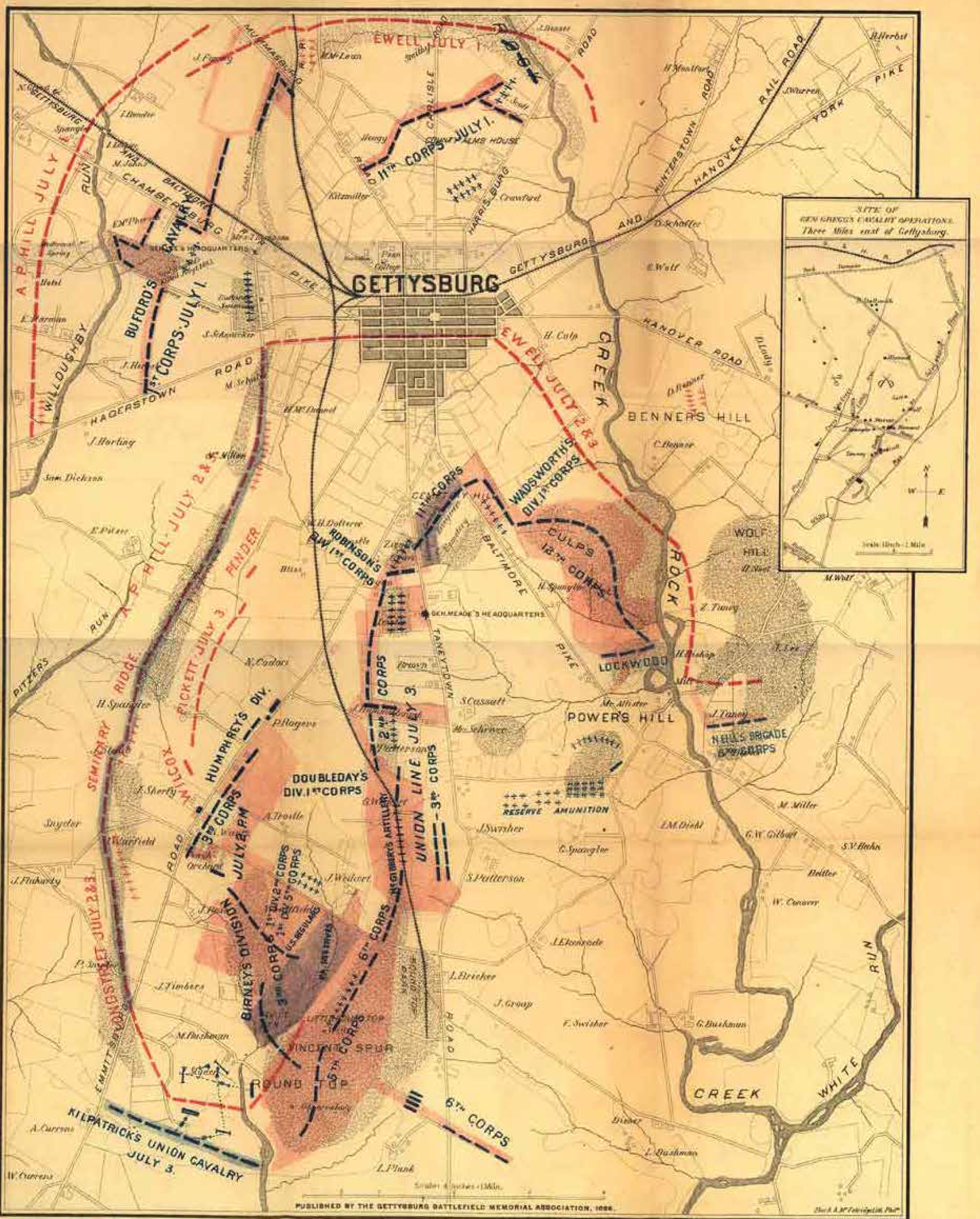

Gettysburg battlefield map for 1–3 July 1863. Courtesy Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association

Burning U.S. Navy observation balloon falling to the ground after be- ing “shot down” over Gettysburg. U.S. Marine Corps Historical Company

Navy observation balloon burning on the ground behind Seminary Ridge. U. S. Marine Corps Historical Company

The New York Tribune wrote that the balloon was ignited by “the use of composition bullets, of the kind used in signal pistols, which were burned in the air, being totally consumed in about five hundred feet, yet having hardness enough to penetrate the skin of the balloon at short range.”85 Yet another report places a living, and rather daring, Marine in the balloon to ignite the balloon, throw out the dummy without the parachute, then parachute to escape. In a poorly written account, the Democrat and Chronicle wrote that “a thrill was provided when one of the large observation balloons was fired by an attacking airplane and [sent] flaming to the ground several hundred feet below, after the observer had leaped to safety with a great parachute.”86

There was no opening artillery barrage as there had been during the beginning of the reenactments on 1 and 3 July. This time, the artillery were staged farther away in the woods, 3,000–3,500 feet behind the ridge, and they fired during the whole charge, with airplanes acting as their spotters.87

Following the initial air action, at around 1030, a smokescreen was laid down on the field in advance of the Confederate troops, until approximately 1040 when the Marines began their assault. Unlike the reenactments of 1 and 3 July, the Confederates attacked the Union position as they would have done in a “modern” engagement with squads and platoons rather than in long shoulder-to-shoulder firing lines.88 The Marines crossed the Codori fields toward the enemy position on Cemetery Ridge in several waves. The idea was to deprive the enemy of a target-rich environment.89 Each wave of squads would advance 20–30 feet and then lay prone as a second group advanced to reinforce them. In this manner, the waves of men leapfrogged each other toward their objective.90

“The machine guns were really there yesterday [4 July]. They were firing real bullets. Machine guns can’t fire blank ammunition. So were all the other machine guns in the woods on Seminary Ridge. But pits had been dug all around them and the bullets were diving harmlessly into the earth,” The Sun reported. Further confirming this, the Washington Post noted that “the machine guns used ball ammunition, for machine guns will not function with blank ammunition. The guns were emplaced in previously prepared pits, and the stream of steel-jacketed lead was pumped into the soggy earth.”91

At some point during the advance, machine gun crews made their way toward Emmitsburg Road, establishing positions along the west side and eventually the east side, when help arrived to get them there. “The audience heard only the thunder of artillery, the ceaseless tat-tat-tat of machine guns and the crack of rifles,” The Sun reported. “They saw little but puffs of smoke and now and then a few men running, only to disappear suddenly as though the ground had swallowed them . . . because that is the way men fight in these days.”92

The Washington Post wrote that the engagement readily established that “a squad of eight men can approximate the fire power of a battalion of the last century.” The reporter further noted that “it became quite apparent to the spectators that modern warfare resolves into movements wherein men fight desperately to kill men they can barely see and are sent to their death by men to whom they are not visible. The inspiring clash of contact combat is a thing of the past.”93

Little by little, the squads of Marine infantry and machine gunners made their way toward a key position—the occupation of Emmitsburg Road—preliminary to the charge upon the High Water Mark, as fighters strafed the Union stronghold, and simulated artillery and mortar strikes detonated over both sides of Emmitsburg Road. Not only had the Union Marines posted the entanglements to obstruct the progress of their Southern counterparts, but also established fortified machine gun positions.94

Marines begin to fall as the battle to capture the Codori house and farmstead gets underway. Archives and Special Collections Branch, Marine Corps History Division

As the battle approached a climactic conclusion, the Confederates seemed to run into stiff opposition in and around the Codori house and farm buildings, which neither small-arms, machine-gun, nor light artillery fire could clear, resulting in the troops who were attempting to capture that position calling for armor support to help.95

Four M1917 light tanks rolled into action, two on the right of the Marine attack and two on the left, and then charged the enemy lines. “The tanks appeared and went after a machine gun nest with machine gun fire and then contemptuously ignored the small arms fire and ironed out some barb wire entanglements,” Chandler wrote.96

The pair of tanks on the right of the Marine assault immediately made for the Codori house and out-buildings. “The tanks went sneeringly up to the Codori house, around the barn, around to the back door, through the chicken yards, up the front porch, firing explosive shells [supposedly] through the windows,” The Sun stated. “In a few moments they waddled away, and you could almost imagine them chuckling horribly, heading again toward the rear to sleep and snore until there was no more killing to do. The enemy in the Codori House was silenced forever.”97 One of the tanks at the Codori house became a “causality” in the attack and was taken out of action by enemy fire.98

Once the Marines had seized both sides of the road and had driven off the Union defenders, creating a clear path to the High Water Mark, the charge was declared over by the officers on the determination that, at this point, “the defenders in consequence would be so shaken in morale that their retreat would be inevitable and the position, Cemetery ridge, won [by the Marines portraying the Southern forces].”99

With the Battle of Gettysburg refought and rewon, the Marines began breaking down Camp Harding on 5 July. After a week on the Gettysburg battlefield, it was time to retrace their steps back to Quantico. A company of engineers left for Thurmont on 5 July to begin setting up the camp there.100 Some planes returned to Quantico since they would only be needed for mail service and not maneuvers. The Canvas White House was disassembled and shipped back to Quantico.101 Although the Marines had felt snubbed by the town of Gettysburg, the town finally realized what it had too late: “This town has found them a different body of troops than they thought, and now everyone seems to regret that the Marines were not given a more cordial reception on their arrival.”102 Part of the softening attitude may have been that residents saw how anxious other towns were for the Marines to visit them for maneuvers. Other cities were already making requests to host the 1923 maneuvers: “Scores of places throughout the country have asked for the camp next year, but it is the idea to have scenes of historical interest used regularly because of the peculiar adaptability for movements of troops and the lessons of patriotism they teach.”103

Results

The multipronged mission to save the Marine Corps was advancing successfully. Public opinion would serve as a strong motivating factor for the Service, Congress, and the president. In the end, General Lejeune achieved what he had set out to do. The Marines received positive publicity from the reenactments. Repeated over a number of years, it kept the Marine Corps in the public eye in an encouraging manner. “All along their line of march from Quantico to Emmitsburg, the Marines received tremendous ovations,” one newspaper noted.104

The reenactments won over the public and the decision makers, though the Marine Corps’ numbers continued to drop for a few more years. From a high of 75,000 in the last year of WWI, enlistment fell to 18,000 in 1925 before ticking up again.105 While disappointing for Marine leaders, at least talk of disbanding the Marine Corps ended, and the Corps won another fight until the fury of battle eventually receded from the public memory. Other elements of the public awareness campaign, such as the birthday celebration and the history behind uniform elements, took hold and are still part of the Marine Corps tradition today.

•1775•

Endnotes

- Ed Gilbert and Catherine Gilbert, US Marine in World War I (Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2016), 20.

- GySgt Thomas E. Williams (Ret), intvw with author, 12 December 2014, hereafter Williams December intvw.

- Ibid.

- Kenneth L. Smith-Christmas, “Marines at the Battle of the Wilderness—1921,” Leatherneck, September 2014, 19.

- “Marines Begin Big Sham Battle,” Star and Sentinel (Gettysburg, PA), 1 October 1921, 3.

- “President Sees Army Camp Life,” Boston (MA) Post, 3 October 1921, 8.

- “Marines Are on the March Here,” Gettysburg (PA) Times, 20 June 1922, 1.

- “President Saluted by 5,000 Marines,” Washington Post, 20 June 1922, 3.

- Williams December intvw.

- “Marines Complete Hike Preparations,” The Sun (Baltimore), 19 June 1921, 3.

- Raymond S. Tompkins, “Marines Are Marching on to Gettys- burg,” The Sun (Baltimore), 25 June 1922, part 5, 4.

- Capt John H. Craige, “The Marines at Gettysburg,” Marine Corps Gazette 7, no. 3 (September 1922): 250.

- The third opportunity came with an unplanned visit while the Marines were camped in Frederick, MD, headed back to Quantico in July.

- “Marine Army Sees Movies of Itself on Eve of ‘War’,” Washing- ton Post, 21 June 1921, 7.

- Tompkins, “Marines Are Marching on to Gettysburg.”

- “Marine Army Sees Movies of Itself on Eve of ‘War’.”

- “Marines Rest in the Hills on Their Way to Gettysburg,” The Sun (Baltimore), 23 June 1922, 2.

- “Marine Army Sees Movies of Itself on Eve of ‘War’.”

- “Mimic War Serious Play, Marines Find on the March,” Washington Post, 3 July 1922, 3.

- “Marines Stage Big Battle, then Lose at Baseball,” Washington Post, 23 June 1922, 1.

- Around 1900, Navy sailors began using the term Gyrene as a derogatory reference to a Marine. “Marines Complete Hike Preparations,” The Sun (Baltimore), 19 June 1921.

- “Marines Rest in the Hills.”

- Ibid.

- “5,000 Marines Camp at Ridgeville: Corps Reach Frederick at Noon Today,” Frederick (MD) Post, 24 June 1922, 1.

- “Road-Weary Marines Find Frederick’s Gates Wide Open,” The Sun (Baltimore), 25 June 1922, 4

- “Frederick Welcomes 5,000 Marines Arriving at Noon for Day’s Stay while Enroute to Gettysburg,” Frederick (MD) News, 24 June 1922, 1.

- “Marines Complete Hike Reaching Camp Gettysburg Today,” Frederick (MD) News, 26 June 1922, 5.

- “Modern ‘Barbara Frietchies’ Greet Marines in Frederick,” The Sun (Baltimore), 26 June 1922, 2.

- “Marines Camp Here,” Catoctin Clarion (Mechanicstown, MD), 29 June 1922, 3.

- “Marine Camp Is Being Laid Out,” Gettysburg (PA) Times, 20 June 1922, 1; and R. S. T., “Marines to Begin Rehearsals of Pick- ett’s Charge Today,” The Sun (Baltimore), 28 June 1922, 1.

- “Camp Is Being Shaken Down,” Gettysburg (PA) Times, 27 June 1922, 2.

- Ibid.

- “Harding Will Review Marines,” Gettysburg (PA) Times, 19 June 1922, 1.

- GySgt Thomas E. Williams (Ret), intvw with author, 29 January 2015.

- R. S. T., “Marines to Begin Rehearsals of Pickett’s Charge To- day.”

- “White House Is Being Erected,” Gettysburg (PA) Times, 28 June 1922, 3; and R. S. T., “Marines to Begin Rehearsals of Pickett’s Charge Today.”

- “White House Is Being Erected.”

- Ibid.

- “Dress Rehearsal for the Charge,” Gettysburg (PA) Times, 30 June 1922, 3.

- “Camp Made Ready for President,” Gettysburg (PA) Times, 29 June 1922, 1.

- Raymond S. Tompkins, “Marines Plan to Reenact Famous Bat- tle Every Year,” The Sun (Baltimore), 3 July 1922, 3.

- For his service during World War I, Hamilton was awarded two Distinguished Service Crosses, the Navy Cross, and four Silver Stars.

- Discrepancies exist in the recorded history for this event. “Captain Hamilton and Sergeant Martin Killed When Plane Fell,” Star and Sentinel (Gettysburg, PA), 1 July 1922, 1; and R. S. T., “Marine Aviators Crash to Death on Battlefield of Gettysburg,” The Sun (Baltimore), 27 June 1922, 1.

- “Captain Hamilton and Sergeant Martin Killed When Plane Fell.”

- Ibid.

- “Marine Aviation,” Aviation, 17 July 1922, 77.

- “Death of Captain Hamilton and Sergeant Martin Saddens Troops,” Leatherneck, July 1922.

- “Captain Hamilton and Sergeant Martin Killed When Plane Fell.”

- Ibid.

- “Death of Captain Hamilton and Sergeant Martin Saddens Troops.”

- “Attend Funeral of Dead Aviator,” Gettysburg (PA) Times, 29 June 1922, 1.

- Ibid.

- R. S. T., “Marines Are Told the Story of Battle,” The Sun (Balti- more), 29 June 1922, 2.

- Ibid.

- John D. Wright, The Language of the Civil War (Westport, CT: Oryx Press, 2001), 48.

- R. S. T., “Marines Are Told the Story of Battle”; and “The Battle of Gettysburg in Art,” National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, http://www.nps.gov/gett/learn/historyculture/gettysburg-cyclorama.htm, accessed 15 January 2016.

- “Attack Made on Seminary Ridge,” Star and Sentinel (Gettys- burg, PA), 1 July 1922, 3.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “City Prepares to Welcome the President Here,” The News (Frederick, MD), 1 July 1922, 1.

- “Harding Made Brief Visit Here,” Gettysburg (PA) Times, 3 July 1922, 1.

- “Harding and Pershing View Re-enactment of Pickett’s Charge,” Gettysburg (PA) Times, 3 July 1922, 1.

- Little Round Top represents one of two rocky hills south of Gettysburg between Emmitsburg and Taneytown Roads. Capt George M. Chandler, “Gettysburg, 1922,” Infantry Journal 21, no. 1 (July 1922): 380.

- R. S. T., “Pickett’s Gettysburg Charge Dramatized in Marine Attack,” The Sun (Baltimore), 2 July 1922, 1.

- Chandler, “Gettysburg, 1922”; and “Harding and Pershing View Re-enactment of Pickett’s Charge.”

- Chandler, “Gettysburg, 1922.”

- R. S. T., “Pickett’s Gettysburg Charge Dramatized in Marine Attack.”

- Chandler, “Gettysburg, 1922.”

- “General Pickett’s Charge Staged for Harding,” New York Tribune, 2 July 1922, 3.

- “Harding and Pershing View Re-enactment of Pickett’s Charge.”

- This spot on the Gettysburg battlefield is called the “High Water Mark of the Confederacy” because it represents both the farthest point of advance for Confederate troops but also the Confederacy’s most significant push into Union territory and thus their failed, best chance at routing the Union army.

- R. S. T., “Pickett’s Gettysburg Charge Dramatized in Marine Attack.”

- Chandler, “Gettysburg, 1922.”

- “Harding and Pershing View Re-enactment of Pickett’s Charge.”

- The Angle (or Bloody Angle) within the Gettysburg battlefield represents the site along Cemetery Ridge where approximately 150 Confederates broke through the Union line on 3 July 1863. Upshur’s father had been wounded in the service of the Confederate States during the actual war, while Upshur was a Medal of Honor recipient for his actions in Haiti in 1915.

- R. S. T., “Pickett’s Gettysburg Charge Dramatized in Marine Attack.”

- Harding and Pershing View Re-enactment of Pickett’s Charge.”

- “General Pickett’s Charge Staged for Harding.”

- “Harding and Pershing View Re-enactment of Pickett’s Charge.”

- “ ‘Modern Gettysburg’ Fought by Marines in Air Thrillers,” New York Tribune, 5 July 1922, 3.

- Named for Max Immelmann, a German World War I ace, the Immelmann turn is a maneuver in which the aircraft acceler- ates to execute an upward half loop and then inverts with a half roll to level flight in the opposite direction at a higher altitude. “ ‘Modern Gettysburg’ Fought by Marines in Air Thrillers.”

- R. S. T., “Cemetery Hill Capitulates to Marine Attack,” The Sun (Baltimore), 5 July 1922, 1.

- Ibid.

- Accounts of this event vary. R. S. T., “Cemetery Hill Capitu- lates to Marine Attack.”

- “ ‘Modern Gettysburg’ Fought by Marines in Air Thrillers.”

- “50,000 See Marines Re-enact ‘Pickett’s Charge’ of July, ’63,

- Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, NY), 5 July 1922. Chandler, “Gettysburg, 1922.”

- F. A. Mallen, “Battle of Gettysburg Re-Fought by Marines during Downpour of Rain,” Frederick (MD) Post, 5 July 1922, 1.

- R. S. T., “Cemetery Hill Capitulates to Marine Attack.

- ”Mallen, “Battle of Gettysburg Re-Fought by Marines During Downpour of Rain.”

- R. S. T., “Cemetery Hill Capitulates to Marine Attack”; and “Marines Thrill 125,000 with Modern Maneuvers,” Gettysburg (PA) Times, 5 July 1922, 1.

- R. S. T., “Cemetery Hill Capitulates to Marine Attack.”

- “Marines Thrill 125,000 with Modern Maneuvers.”

- Chandler, “Gettysburg, 1922,” 380.

- “Marines Thrill 125,000 with Modern Maneuvers.”

- Mallen, “Battle of Gettysburg Re-Fought by Marines During Downpour of Rain”; and Chandler, “Gettysburg, 1922.”

- R. S. T., “Cemetery Hill Capitulates to Marine Attack.”

- “Marines Thrill 125,000 with Modern Maneuvers.”

- Ibid.

- F. A. Mallen, “Marines Anxious to Get Back to Fred’k,” Daily News (Frederick, MD), 6 July 1922, 9.

- “Marines Are Ready to Break Camp,” The Sun (Baltimore), 6 July 1922, 7.

- Mallen, “Marines Anxious to Get Back to Fred’k.”

- “Marines Are Ready to Break Camp.”