Shortly after his term as Commandant of the U.S. Marine Corps came to an end, General Wallace M. Greene Jr. recorded an extensive oral history for the Marine Corps History Division. During one session, Greene discussed the difficulties of advising President Lyndon B. Johnson. Recalling that the task often had the feel of a game of poker, Greene said of the president, “He had that look in his eye, as if he was wondering why I played that card.”1 As a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Greene believed his duty was to provide the president with honest and frank military advice. At the same time, Greene was continually frustrated by what he believed to be the president’s failure to adequately come to terms with what the United States needed to do to win the war in Vietnam.

Although they were officially the president’s principal military advisors, the Joint Chiefs often had a contentious relationship with Johnson, who favored consulting civilian officials such as Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara and National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy on national security matters.2 For the Joint Chiefs’ part, Service parochialism often led them to give less than frank advice to the president, and both Johnson and his predecessor, John F. Kennedy, often felt that their counsel was neither reliable nor constructive.3 However, while Johnson and McNamara (and most historians of the Vietnam War) treated the Joint Chiefs as a unitary body, it was in fact made up of five individuals whose positions on national security often differed. The chiefs held opposing views not only on the Vietnam War but also on what the actual purpose and role of their body was. Although they were the highest ranking military officials in their respective Armed Services, the Joint Chiefs were technically outside of the chain of command and consequently occupied an ambiguous position within the U.S. national security structure.

General Wallace M. Greene Jr. became the 23rd Commandant of the Marine Corps on 1 January 1964. Official U.S. Marine Corps Photo A411928

This problem became particularly pressing as the Johnson administration rapidly Americanized the U.S. commitment to South Vietnam between 1964 and 1965.4 A committed cold warrior, Greene believed that the United States needed to take a decisive stand in South Vietnam and counter the insurgency there by using American military power against North Vietnam. However, Greene frequently felt that his advice was not reaching the president, despite what he believed to be his statutory duty to serve as an advisor to the commander in chief on military matters. The Commandant blamed structural shortcomings in the advisory system for effectively blocking access to the president. These systemic problems could be traced to the Kennedy administration and that president’s preference for relying on close personal advisors to make ad hoc national security decisions.

To confront this issue, Greene proposed substantially restructuring the National Security Council with the addition of a National General Staff. The staff would include a joint military-civilian staff tasked with both advisory and operation responsibilities. Such an organization, Greene believed, would overcome the obstacles that prevented President Johnson from receiving sound and effective military advice on the situation in South Vietnam. At the same time, Greene hoped the plan would force Johnson to make a firm commitment on the Vietnam crisis.

General Wallace M. Greene and the Joint Chiefs of Staff

General Greene became Commandant in 1964. The appointment was the capstone to a long career as a dedicated and effective staff officer and planner. A graduate of the United States Naval Academy, Greene’s career before World War II mirrored that of many Marine officers in the 1930s: postings to ships’ detachments and service with the 4th Marines in Shanghai, China. During the critical months before the America’s entry into the war, Greene served in the 1st Marine Division’s operations section and in the United Kingdom, where he observed British commando units—later using lessons learned from that experience to strengthen and improve U.S. amphibious warfare techniques.

Throughout World War II, Greene’s billets gave him considerable experience as a planner and organizer. He served as the operations and training officer for the 3d Marine Brigade—as operations officer for the Tactical Group 1 during the Marshall Islands campaign in early 1944 and as operations officer for the 2d Marine Division during the Mariana Islands campaign in the summer of 1944. During the latter operation, he first worked under Colonel David M. Shoup, who served as the division’s chief of staff. In the postwar period, Greene continued to serve in operations billets with both the Marine Corps and Joint Staff, working as a representative on the staff of the National Security Council. In 1956, as the new commanding general of the Recruit Training Command at Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island, South Carolina, Brigadier General Greene once again found himself working with Shoup. Greene and Shoup, who was then serving as inspector general of recruit training, were tasked with investigating the recent accidental drowning of six recruits at Ribbon Creek, Parris Island, and also with reforming Marine Corps recruit training. Following this, Greene worked as the operations officer for Headquarters Marine Corps as deputy chief of staff of Plans, and following Shoup’s appointment as Commandant in 1960, served as the new Commandant’s chief of staff.5

By the time President Kennedy nominated Greene to succeed Shoup in 1963, Greene had built a career as an adept staff officer capable of working with “vocal, volatile extroverts.”6 He had earned two Legions of Merit for his planning work during the Marshalls and Marianas campaigns. He had also learned to pursue goals regardless of whether or not he would alienate senior officers in the process, notably during the time he was tasked with reforming Marine recruit training. This, along with his experience working for the Joint Staff and the National Security Council, gave him ample experience navigating the halls of power in Washington, DC. In short, Greene represented in the Joint Chiefs of Staff the shift away from officers with experience leading large formations in combat to those who had spent most of their careers working as staff officers.7

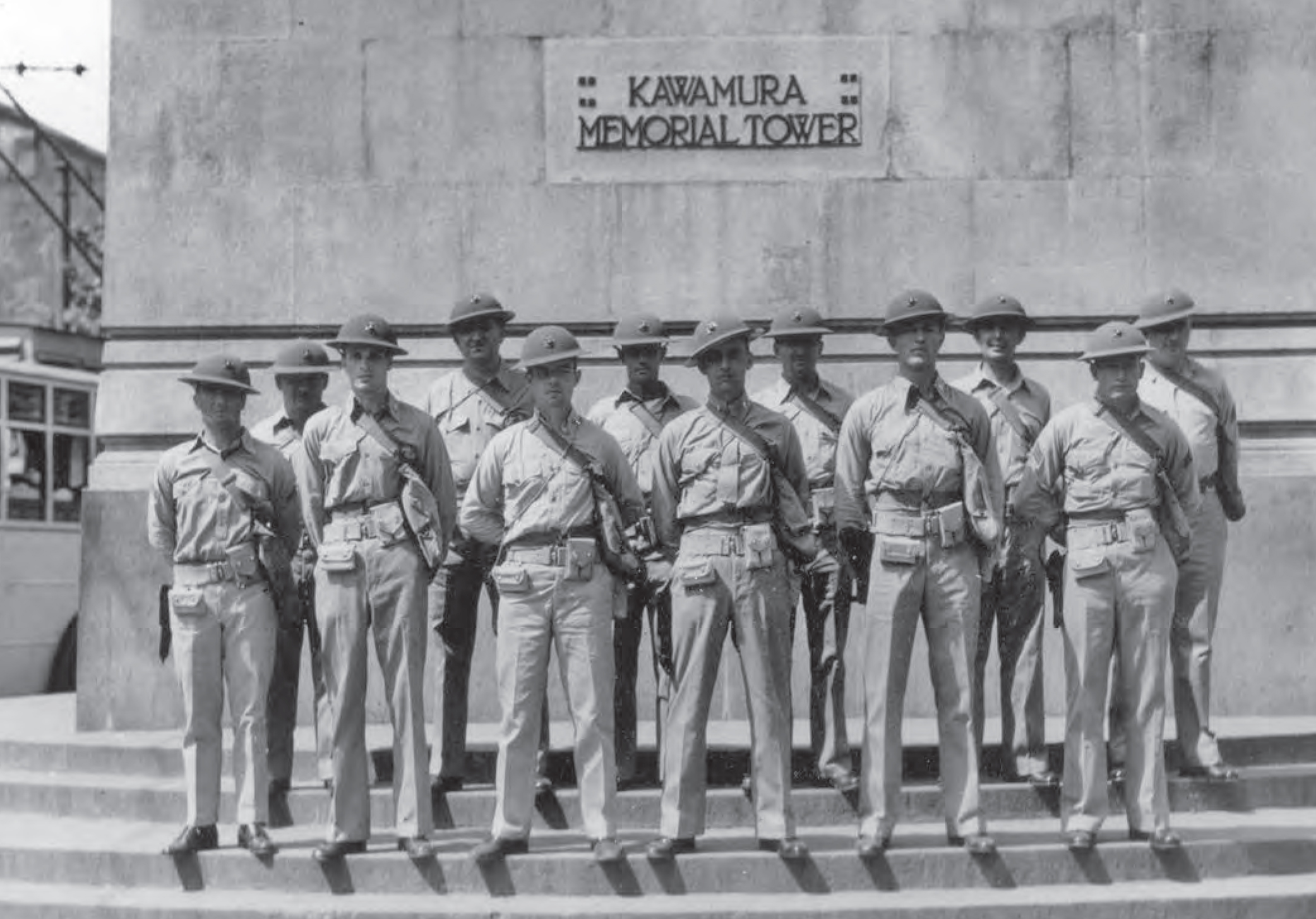

Like many Marines commissioned in the early 1930s, Greene served with the 4th Marines in Shanghai. Then 1st Lt Greene is pictured here with other officers and noncommissioned officers of the 2d Battalion, 4th Marines, in front of the Kawamura Tower in Shanghai in 1937. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo 530841

According to the amendments of the National Security Act of 1947 passed in 1952, the Commandant was allowed only to attend Joint Chiefs’ meetings in which matters relevant to the Marine Corps were on the agenda.8 Since most matters of relevance to the combined Service chiefs concerned joint operations of some kind, this provision proved to be a technicality, and Greene always acted as an equal to the chiefs of staff of the U.S. Army and Air Force and to the chief of naval operations. In accordance with this status, Greene believed the Commandant needed to participate equally in the task of advising the president on matters of national security.

Greene’s vision of the duties and roles of the Joint Chiefs, however, was not necessarily shared by his colleagues. In particular, the chairman at the time Greene became Commandant, Army General Maxwell D. Taylor, had a conception that was in many ways diametrically opposed to the Commandant’s. For his part, Greene did not believe that the Service chiefs were required to speak with one voice or that the chairman’s voice should carry more weight than those of the other chiefs. He argued that

[the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff] is not a man who votes and breaks a deadlock, but he is the man who is supposed to organize and run the Joint Staff and also to present the views of the Chiefs. If the views differ from his own or among the Chiefs, then these views should be presented for final decision by the Secretary of Defense or the President.9

In contrast, Taylor saw the chairman as a personal advisor to the president whose voice carried greater weight than the other chiefs. His position could be traced to his close relationship with President Kennedy, who had recalled Taylor to active duty in 1961. Following the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961, Kennedy became convinced that the Service chiefs had failed to adequately prepare him for the possibility that the clandestine attempt to depose Cuban dictator Fidel Castro would fail. Already uncomfortable with the military, Kennedy asked the then-retired General Taylor to serve as his representative to the Joint Chiefs of Staff.10 It was a curious and confusing approach to managing national security affairs, effectively creating a parallel advisory system. If Taylor was to serve as the personal advisor to the president, then what was the role of the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Army General Lyman L. Lemnitzer? The approach, however, suited Kennedy well. Inexperienced and somewhat unsure of himself, the president was more at ease receiving advice from those with whom he had developed a close rapport, most notably the U.S. attorney general, his brother Robert F. Kennedy.

In this undated photograph, BGen Greene sits with senior noncommissioned officers during his term as commanding general, Recruit Training Command. Photo by Alfred W. Rohde Jr., courtesy of U.S. Marine Corps Photographic Section

During the first two years of Kennedy’s presidential term, Taylor served closely with Kennedy and grew to believe that the president needed a close, informal relationship with his chief military advisor. In his memoir, Taylor set forth a vision of the chairman’s responsibility that strongly contrasted with General Greene’s.

With the opportunity to observe the problems of a President at closer range, I have come to the understanding of an intimate, easy relationship, born of friendship and mutual regard, between the President and the Chiefs. It is particularly important in the case of the Chairman, who works more closely with the President and Secretary of Defense than do the service chiefs. The Chairman should be a true believer in the foreign policy and military strategy of the administration which he serves or, at least, feel that he and his colleagues are assured an attentive hearing on those matters for which the Joint Chiefs have a responsibility.11

In 1962, Kennedy replaced Lemnitzer with Taylor. In making Taylor chairman, the president resolved the awkward dual-track system created shortly after the Bay of Pigs invasion. However, by appointing his personal advisor, the president also undermined the effectiveness of the Joint Chiefs as a corporate body; Taylor firmly believed that the chairman’s personal assessments of national security matters carried greater weight than the other chiefs’ assessments. Consequently, Taylor tended to present his views to the president as if they were the chiefs’ combined views, creating the impression of unanimous consent when none perhaps existed.12

These diverging opinions ultimately led to considerable distrust on Greene’s part regarding Taylor. As Greene noted, “I always had the feeling that he [Taylor] was not properly presenting either the views of the Joint Chiefs to the National Security Council and to the president, but instead favored them with his own views, and also he never accurately reported back to the Joint Chiefs his conversations with the president and with the National Security Council.”13 Frequently in his recollections, Greene noted his conflicting attitudes concerning Taylor, always following up remarks on the chairman’s brilliance and intelligence with more critical comments about the general’s dishonest and untrustworthy behavior as head of the Joint Chiefs. “There is no doubt about his outstanding capability as far as his brain was concerned, but not as far as his motives sometimes were concerned.”14

Kennedy’s death in November 1963 elevated Vice President Johnson to the presidency. Although in most ways the rough-hewn, outwardly confident Texan was a stark contrast to the polished and cautious Kennedy, the two presidents shared a preference to rely on advisors outside official channels to make national security decisions. Thus, Greene began his term as Commandant of the Marine Corps already facing obstacles that would thwart his wish to play an active and energetic role in national security policy planning.

Greene’s Assessment of the Vietnam War in 1964

As Shoup’s chief of staff, General Greene delivered an address to the U.S. Army War College in May 1963. During the question-and-answer period, he was asked about his position on U.S. involvement in South Vietnam (then largely advisory in nature). He described the situation as a quagmire and expressed concern about the United States becoming bogged down in the country. He also expressed the hope that the Marine contingent operating in Vietnam would remain small for fear that a larger commitment to Southeast Asia would sap the Corps’ ability to fulfill its duties as a contingency force.15

Scholars of the Vietnam War have cited comments like this as evidence that Greene “explicitly rejected” American intervention.16 Actually, the chief of staff ’s attitude was more lukewarm and ambivalent. While he criticized the character of the American involvement, Greens also stressed that “if we were, could, go into South Vietnam and do it our way, I think we could maybe clear that situation up within a reasonable time.” Yet, on the whole he was skeptical of what the United States could achieve in the country. When another participant asked about bombing North Vietnam, Greene stated he did not think such a move would make a significant difference: “I mean, there’s just so many of them that I feel that if you were to bomb Hanoi [Vietnam], you wouldn’t stop them from doing what they are doing. And you might well bring the Chinese Communists in on there. And then what are you going to do, use atomic weapons?”17

Gen David M. Shoup, Commandant of the Marine Corps, passes the Marine Corps battle color to his successor, LtGen Wallace M. Greene Jr., during change of command ceremonies at the Marine Barracks Washington, DC, on 31 December 1964. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo

Pointing out that the American public would not accept a significant number of casualties to defend the South, he made a prediction that proved to be eerily accurate: “Now, that old grindstone starts turning faster and faster. That means more and more casualties, more and more of the money and treasure of the United States going to be spent there, and maybe in 10 years, we’ll either clean up the situation or we’ll have to get out like the French did.”18 Thus, a member of Greene’s audience could have left with the reasonable belief that the future Commandant was against escalating American involvement in the Vietnam War.

Yet, by the following January, he had become much more hawkish. In a January 1964 report on an inspection trip to Southeast Asia submitted to President Johnson, now-Commandant Greene described morale amongst anti-Communist forces in South Vietnam as good, described U.S. advisors as “capable and enthusiastic,” and recommended that the “destruction of economic targets in North Vietnam designed to bring Ho Chi Minh to the council table should be initiated immediately.”19 A month later, he once again advocated increasing Ameri- can involvement, stating in a staff study to the Joint Chiefs that “first, there must be a clear-cut decision either to pull out of South Vietnam or to stay there and win. If the decision is to stay and win—which is the Marine Corps recommendation—this objective must be pursued with the full concerted power of U.S. resources.”20

What caused the change in attitude, from “explicitly” warning against escalation to calling for the use of “the full concerted power of U.S. resources” in Southeast Asia? First, one should be cautious about pinning down Greene and other advisors with overly reductive labels, such as “hawks,” “doves,” “true believers,” “doubters,” etc. As Secretary of Defense Clark M. Clifford responded when asked if he was a hawk or a dove, “I am not conscious of falling under any of those ornithological divisions.”21 Other government officials felt the same way, and their attitudes and positions were often fluid. From his May 1963 comments, Greene clearly had not yet fully formulated his thoughts on the Vietnam conflict. The speech he delivered did not mention Vietnam at all, and only in the question-and-answer session did Greene address the matter in (what sounds like) an off-the-cuff manner. Also of note in 1963, Greene was speaking as the representative of General Shoup, an opponent to expanding the U.S. involvement in Vietnam.22

Second, the situation in South Vietnam had dramatically changed between May 1963 and January 1964. The summer of 1963 was a troubled time for the government of South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem, as Buddhist-led protests against his Catholic-dominated regime garnered world attention. The image of Buddhist monks self-immolating on the streets of Saigon poisoned American public support for Diem’s government, and the Kennedy administration soon concluded that the counterinsurgency effort in South Vietnam would be more effective if the South Vietnamese president was removed from power. Just weeks before Kennedy’s death, Diem was murdered during a U.S.-backed coup led by a group of South Vietnamese generals. Effects of that putsch were still being felt in January 1964 when the military council that had replaced Diem was deposed in yet another coup, this one led by South Vietnamese General Nguyen Khanh.

Greene’s inspection tour of South Vietnam took place shortly before Khanh seized power. The inspection was one of Greene’s first acts as Commandant and seemed to leave an indelible mark on his position regarding the war. Upon returning to the states, he became a firm advocate for bombing North Vietnam. Throughout the first months of his term, Greene repeatedly pressed for launching military attacks against the north. At the same time, he also believed that the United States could never guarantee the independence or viability of South Vietnam unless the Americans made it clear to the world that the United States was committed to destroying the Viet Cong’s ability to wage its insurrection. In the February study quoted above, Greene saw five possibilities open to the United States: (1) a complete withdrawal of American forces; (2) the neutralization of South Vietnam; (3) intensification of current operations; (4) extension and expansion of operations into North Vietnam without U.S. involvement; or (5) expansion of operations into North Vietnam with U.S. forces.23 Greene dismissed the first three options, believing that withdrawal and neutralization would harm American interests.

Greene believed that the final two options provided the best course to follow. Expanding the war but continuing to limit U.S. involvement would provide the possibility of a military victory, demonstrate America’s determination to win the war, and maintain the “face of a Vietnamese war being fought by Vietnamese.” However, the Commandant admitted that this course did not “insure [sic] an early victory.”24 Direct involvement would provide even clearer evidence of American determination to win the war, allow the South Vietnamese to draw on superior American air and naval forces, and speed up the “timetable for winning the war.”25 The open commitment of forces carried considerable risks, however, including provoking intervention from the People’s Republic of China. Direct involvement could also potentially alienate neutral allies, create strains with European powers, and further drain U.S. resources. Pointedly, a staff study acknowledged that direct involvement would commit the “U.S. to an ‘unpopular’ war” and carry no guarantee that militarily defeating North Vietnam would in any way increase support for South Vietnam’s “unpopular and autocratic regime.”26 Greene subsequently concluded that the best course was to expand the war using South Vietnamese forces and continue indirect American involvement. However, the United States needed to reserve the option of taking direct action if required.

Despite his exhortation that the United States needed to “indicate unequivocally” that it was not going to abandon South Vietnam, Greene expressed uncertainty about whether any of his proposals would achieve victory, given the limited means at America’s disposal. Greene believed that the president’s administration needed to “make clear to Congress and to the American people that the U.S. policy is to win in South Vietnam.”27 At the same time, however, the Commandant recognized that a firm commitment did not guarantee victory, did not ensure the legitimacy or stability of South Vietnam, and did not present a clear course of action.

Despite this ambivalence, Greene pressed for a more aggressive campaign against the North Vietnamese involving both air strikes and a naval blockade. He recommended transforming the commander of U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) into a true theater commander with authority over all U.S. efforts in the region. He also called for a range of new security measures in South Vietnam: censorship, a national identity card program, and curfews. He envisioned a bombing campaign that would, “in a rising crescendo,” carry out the “systematic destruction” of targets in North Vietnam using both the South Vietnamese Air Force and U.S. air assets. It was, in all but name, a recommendation for a campaign of graduated pressure against the North. Commando raids, covert operations, and naval bombardment could also be utilized in support of the operation. The Commandant also recommended that the United States warn Laos and Cambodia to cease allowing Viet Cong forces to use the countries’ territories for logistical support.28

The subject of Vietnam came up during a meeting with President Johnson and the Joint Chiefs held on 4 March 1964. As the participants reviewed an impending inspection trip to South Vietnam by McNamara and Taylor, the president solicited the opinion of each chief. Taylor recommended expanding the war to include selective strikes against North Vietnamese targets. When Johnson responded that such an action would “almost certainly” spark an intervention by China and the Soviet Union, Taylor stated that he did not think such a response would occur. Greene said that he did not subscribe to Taylor’s view and argued that expanding the war north would likely spark a Chinese response.

I told the President that, in my opinion, this would result in a major campaign, smaller perhaps, but similar to that which had taken place in Korea, and that there was risk of a possible escalation into another world war. However the bitter fact was that we were going to have to take a stand somewhere and the decision which he was going to have to make, as President, was whether or not SVN [South Vietnam] was the location where this stand should be made.29

Was Greene stating that escalating efforts in Vietnam was worth the risk of a potential third world war? Or was he exaggerating the potential consequences in order to convince President Johnson not to expand American involvement? Based on the recommendations he made in February to the other Joint Chiefs, one can reasonably conclude that Greene firmly believed that a war with the major Communist powers was inevitable and that aggressively taking the fight to North Vietnam was a necessary step in the broader struggle against international Communism.

Commandant Greene reviews an evening parade at the Marine Corps Barracks Washington, DC, alongside the surviving Commandants on 9 July 1964. From left: Gen Greene, Gen Thomas Holcomb (Ret), Gen Alexander A. Vandegrift (Ret), Gen Clifton B. Cates (Ret), Gen Lemuel C. Shepherd (Ret), and Gen David M. Shoup (Ret). Official U.S. Marine Corps photo

Johnson responded that he “subscribed to the analysis of ‘The Marine General”’ and that he felt either outright withdrawal or an expansion of operations were the best options available to the United States. However, the president immediately declared that, while he agreed expanding the war was the best option, he did not want the United States committed to a war until after the November presidential election, when the political situation “would be stabilized” and the “President and the new Congress could then actively advocate a stepped-up campaign.” Greene recorded in his meeting notes that he suspected Johnson was “indirectly telling General Taylor that he did not want him to return from [South Vietnam] with a recommendation that the campaign there be expanded to include [North Vietnam] to the extent that the risk might arise of a Korean-type war, or all-out war with the Communists.”30

Johnson, the consummate politician, kept his cards close to his chest, leaving the chiefs with little sense of where he stood on the war. On the one hand, he expressed concern about Chinese intervention. On the other, he agreed that the war would likely have to be expanded to North Vietnam if South Vietnam was to survive as an independent state. Ultimately, Greene concluded that President Johnson wanted to delay making any major decisions about the war and consequently pressured both Taylor and McNamara not to recommend escalation. Greene’s notes from a Joint Chiefs’ meeting held the next day recorded that “the Chairman said that he didn’t know what he might recommend at this time; however, he knew that his neck and the [secretary of defense’s] neck were on the chopping block.”31 The meeting with Johnson and the comments by Taylor led the Commandant to draw the conclusion that both the chairman and secretary of defense were going to withhold their honest assessments of the situation in South Vietnam and not recommend taking what he believed were the necessary steps for achieving victory in Southeast Asia.

Upon returning from his visit to South Vietnam, McNamara submitted a memorandum that confirmed Greene’s worries. The memo laid out a number of measures for the United States to take that McNamara believed would help stabilize the war situation. The measures focused on strengthening South Vietnam’s ability to fight the war, without a significant increase in U.S. involvement. Thus, McNamara recommended increasing the size of the South Vietnamese armed forces through national mobilization, furnishing new armored personnel carriers and attack aircraft, and continuing American reconnaissance flights over the Cambodian and Laotian borders.32 Although McNamara did propose that the United States be authorized to conduct air attacks against Viet Cong forces across the border “for the purpose of border control,”33 the secretary of defense’s recommendations were largely designed to maintain the status quo.

The chiefs were near unanimous in their belief that the measures were inadequate.34 “Half-measures won’t win in South Vietnam,” Greene declared, further noting that, “I do not believe that the 12 recommendations discussed above offer little more than a continuation of the present programs of action in Vietnam.”35 He also stated that the proposals placed too many restrictions on the United States and left the initiative with China and North Vietnam. The drive to maintain the status quo would continue to drain American resources and increase, rather than reduce, “dissatisfaction amongst the American people.”36

Despite the chiefs’ protests, McNamara submitted the memorandum to President Johnson without change, and the proposals were adopted as National Security Action Memorandum 288.37 Greene later criticized both McNamara’s and Taylor’s handling of the process, recalling that “it was noteworthy that at no time did the Secretary of Defense invite the Chiefs to discuss his memorandum with them. In other words it was a fait accompli. He accepted without comment the Chiefs’ memorandum which covered his own memorandum to the President, but he never at any time had discussed his final paper.”38 In Greene’s view, the secretary and chairman presented Johnson with the range of options that the president wanted to hear, not the options he needed to hear. In short, Greene was convinced that Johnson was not receiving sound or honest advice.

Even more frustrating was that Taylor and McNa- mara were possibly misconstruing the positions of the Joint Chiefs. Just days after Johnson had accepted McNamara’s recommendations, Greene learned that Central Intelligence Agency Director John A. McCone had expressed doubts about the proposals and that General Taylor deliberately withheld McCone’s comments from the chiefs. Even more surprising, Taylor apparently inked out references to annotations McCone had made on the draft of McNamara’s memorandum that had been submitted to the chiefs for comment.39 Greene called the chairman’s actions “unethical” and “dishonest” and confronted Taylor on the matter the next day. In a heated exchange, Greene asked whether the chiefs’ views were being presented in their entirety to Johnson. Taylor angrily retorted that if the chiefs had concerns, they could take their personal views to the president themselves, but he would not submit any memorandum drafted by other members of the Joint Chiefs to McNamara that he did not agree with.40 The chairman also claimed that the chiefs’ views and estimates of the situation in South Vietnam had been submitted “over a period of time and appeared in parts in a number of papers.”41

President John F. Kennedy meets with Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Maxwell D. Taylor and Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara on 2 October 1963. Photo by Abbie Rowe, courtesy of White House photographs, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston

Taylor’s attitude unnerved Greene, who believed that the chairman was deliberately misconstruing his positions to President Johnson. Just as troubling was Taylor and McNamara’s efforts to paint a picture for the president about South Vietnam that Greene believed did not match the reality on the ground. McNamara’s dominance of the advisory process was particularly frustrating for the Commandant as he believed that the secretary of defense “appeared to think that he knew more about all the military aspects of the problems in Vietnam and the cures therefore than any of the military persons present.”42 The Joint Chiefs of Staff, in short, were not being used as they should. The Commandant believed that President Johnson was far too reliant on a small coterie of advisors, and neither McNamara nor Taylor saw any fault with this particular approach.

President Johnson meets with the Joint Chiefs at his ranch in Texas in December 1964. Clockwise from the president: Secretary of Defense McNamara, the president’s military aid MajGen Chester Clifton, Air Force Chief of Staff Gen Curtis E. LeMay (with signature cigar), Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Gen Earle G. Wheeler, Deputy Secretary of Defense Cyrus R. Vance, Army Chief of Staff Gen Harold K. Johnson, Chief of Naval Operations Adm David L. McDonald, and Commandant of the Marine Corps Gen Greene. Photo by Yoichi Okamoto, courtesy of LBJ Presidential Library

Reforming the Advisory System: Greene’s Proposals for a National Staff

At this early stage in his term, Greene clung to the idea that if his positions on the situation in Southeast Asia could be effectively and accurately relayed to the president, then a true shift in American strategy could take place. He pursued this task as the consummate staff officer. Having served on various national security posts during three presidential administrations, Greene was convinced that the informal advisory system used by both Kennedy and Johnson was the root cause of the Joint Chiefs’ inability to provide adequate and effective advice on the Vietnam War. As a member of the National Security Council staff during Dwight D. Eisenhower’s presidency, Greene had gained firsthand knowledge and experience with the formal advisory structures used by that administration. Kennedy saw these structures, in particular the National Security Council’s Planning Board and Operations Coordinating Board aswell as the Joint Chiefs of Staff, as ineffective and unwieldy. Consequently, he dissolved the two boards and relied on personal military advisors rather than the Joint Chiefs.43

Greene believed rebuilding these planning organizations would not only strengthen strategic planning but also ensure that the president could make a firm decision on the situation in South Vietnam. Throughout 1964, Greene repeatedly pushed for a solution he described as a “National Staff ” or “National General Staff.” Greene promoted his concept in meetings with presidential advisors, in speeches, and in formal memoranda submitted to the Joint Chiefs. The Commandant elaborated on this concept in a May 1964 speech at the Armed Forces Staff College. In the address, Greene noted that the executive branch did not have a mechanism to ensure continuity between different administrations in regard to planning for impending national security crises and emergencies. While the National Security Council had a staff, the staff lacked “an operational function, as all executive authority is vested in the President and in the Heads of the several departments and agencies of the Government.”44

The United States, Greene argued, lacked an interdepartmental organization capable of coordinating how national security decisions made by the president could be implemented by the various executive agencies and departments. “Because of the lack of such a body with interdepartmental membership, programs must be implemented through so-called ‘normal coordination’—or, as is most usually the case, through ad hoc arrangements devised for individual problem areas.” Greene proposed resurrecting the National Security Council’s Planning Board and creating a National General Staff “composed of representatives of all departments and agencies concerned with overall national security.”45 The staff would be a civilian organization tasked with the same responsibilities and empowered with the same authority as a military general staff. The staff would even include a National Command Center, which would serve a similar function as the National Military Command Center.46

Greene continued to press his idea of a National General Staff throughout 1964. He found an ally in the chief of staff of the Air Force, General Curtis E. LeMay. Toward the end of August 1964, LeMay submitted his own memorandum to the chiefs and McNamara recommending the resurrection of the National Security Council’s Planning Board. In a statement that reflected many of the same arguments made by Greene, LeMay criticized the ad hoc nature of security planning and the basic problem that the professional recommendations of the United States’ military leadership were not reaching the president in a systematic manner.47 Responding to LeMay’s proposal, Greene used a lengthy memorandum to appraise the chiefs of his National General Staff concept.

The memo restated most of the major arguments of his speeches from the spring of 1964: the current National Security Council lacked the capability and mission “to maintain a continuing appraisal over all events and happenings which have impact on security policies.”48 The Joint Chiefs also were unable to fulfill this role, being comprised only of military personnel and serving only as advisors to the president. Again, Greene suggested reconstituting the Planning Board “as a full-time agency with a Chairman and members appointed by the President, who would have no other duties in the Government.” The Planning Board would manage the National General Staff in much the same way that the Joint Chiefs managed the Joint Staff. The staff would then “coordinate and direct the implementation of all Executive departments and agencies of approved policies and programs.”49

Greene’s proposal involved an ambitious and radical restructuring of the national security advisory system. Thus, while it may have streamlined the manner in which presidential decisions were implemented, the likelihood of such an organization coming to pass was improbable. Critically, the concept did little to address Johnson’s own preferred method of operating. When Greene brought up the concept during a meeting with Bromley K. Smith, the National Security Council staffer pointed out the difficulties of creating such an organization. In the course of the session, Greene noted that the failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion had convinced him that the advisory systems used by President Kennedy was an ineffective means for making national security strategy and policy. Greene went on to argue that the Johnson administration threatened to make the same mistakes with Southeast Asia, in large part due to the administration making decisions “without proper advice” and with “poorly rounded estimates of the situation.”50

As Greene laid out his vision of a national staff, Smith pointed out how President Kennedy would never have agreed to such an arrangement. While he noted Johnson might be more receptive, Smith nevertheless observed that National Security Advisor Bundy’s centralized White House staff was better suited to the type and detail of advice the current president wanted. According to Smith,

. . . the President was interested in a great deal of detail; e.g., during the recent air strike against Viet Cong targets in Laos, he wanted to know when and where each of the strike planes had landed and when they were all safely home, even though it might be necessary to wake him in the middle of the night to acquaint him with these facts.51

While Smith recognized that excessive reliance on Bundy and his staff was a problem, Smith was also skeptical that the president would be able to get so many agencies and individuals to surrender their prerogatives to a National General Staff.

Greene’s concept of a National General Staff attested to his abilities as a creative and ambitious planner. He saw himself not only as the senior officer of the Marine Corps, but also as a senior advisor to the president. Furthermore, Greene acknowledged that the Joint Chiefs of Staff were limited in the kind of advice they could provide to help the president deal with the almost constantly changing and emerging national security threats of the Cold War. Greene recognized that confronting these threats required close coordination and cooperation between civilian and military agencies. Consequently, he admitted that the Joint Chiefs would only serve as a supporting element to the National General Staff.

However, while the idea of a national staff may have been ambitious and would potentially place a rational structure that would help organize the seemingly chaotic constellation of advisory agencies committees, and departments serving the president, by proposing a national staff Greene demonstrated a basic misunderstanding of how influential a president’s personality and personal style were in shaping how decisions were reached and implemented. Greene was convinced, for example, that the failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion was due to the Kennedy administration’s overreliance on an informal, ad hoc advisory system. Yet Kennedy drew the exact opposite conclusion, feeling that the Joint Chiefs of Staff had failed to provide him with a frank assessment of the consequences of the operation and placed the blame for the failure at their feet.52 Kennedy saw the large, formal advisory systems of the Eisenhower era as slow, ungainly, and potentially more interested in their own prerogatives than in serving the president. In his 1964 speech to the Armed Forces Staff College, Greene argued that “an organization such as the one proposed would so prove its usefulness that it would be perpetuated and strengthened by any Chief Executive who had to face the tangle of problems that will continue to confront our nation as the Free World leader.”53 Greene failed to acknowledge that certain presidents would potentially have a different view. As scholars of his presidency have shown, Johnson preferred receiving advice from a tight-knit group of advisors who would reinforce, rather than challenge, his preconceptions.54 Believing this approach to be detrimental to strategic planning, Greene hoped his National General Staff would both strengthen Amer- ica’s ability to cope with national security challenges and ensure that the president would make appropriate and effective policy decisions.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff in February 1965. From left: Chief of Naval Operations Adm McDonald, Air Force Chief of Staff Gen John P. McConnell, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen Wheeler, Commandant of the Marine Corps Gen Greene, and Chief of Staff of the Army Gen Johnson.Photo by Frank Hall, courtesy of Department of the Army

In this meeting held in July 1965 concerning the Vietnam War, President Johnson is flanked by some of his principal advisors. From left: Gen Greene, Gen Johnson, Secretary of the Army Stanley R. Resor, National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy (standing), President Johnson, and Secretary of Defense McNamara. LBJ Presidential Library

The system was never created because the proposals did not move beyond the Joint Chiefs of Staff. President Johnson never changed his approach; he continued to carry out foreign policy using close, personal advisors in an often, improvised manner. Beginning in 1965, Greene’s attention began to shift. The South Vietnamese government continued to be afflicted by coups and instability. The Viet Cong also seemed to be taking the initiative in the conflict, and the commander of the MACV, Army General William C. Westmoreland, became concerned that South Vietnam’s collapse could be imminent. In March 1965, following General Westmoreland’s requests for U.S. troops to protect American installations in South Vietnam from Communist attacks, the 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade landed two assault battalions at Da Nang, Vietnam. General Greene was responsible for raising and equipping the Marine Corps forces that were then operating in increasing numbers in South Vietnam. Unsurprisingly, concerns about a National General Staff became less of a concern for the Marine Corps Commandant.

Gen Greene visits the headquarters of the South Vietnamese Marine Brigade in April 1965. He is accompanied by BGen Le Nguyen Khang, commanding general of the South Vietnamese Marines. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo A184014

Conclusion

In the period between the passage of the National Security Act of 1947 and the Goldwater-Nichols Department of Defense Reorganization Act of 1986, the Joint Chiefs of Staff occupied an ambiguous position within the United States’ national security system.55 Neither the chairman nor the Service chiefs were in the official chain of command and, while they were tasked by statute with providing the president and secretary of defense with military advice, the commander in chief could accept or dismiss the advice as he saw fit. For a number of reasons, this limitation on the Joint Chiefs’ authority was reinforced during the Johnson administration. Johnson personally preferred drawing advice from a limited number of advisors to reinforce his own viewpoints. Seeing the conflict in Vietnam as a Cold War emergency, both Johnson and McNamara believed the situation could be managed through a mixture of diplomatic and military pressure. The two men believed the Joint Chiefs only saw potential military solutions to the problems. Consequently, the chiefs saw their advice as potentially irrelevant.

Greene believed that Johnson’s advisory system was fundamentally flawed. Although Greene was not adverse to the principles of graduated pressure, he conceived of Vietnam as a military problem that required military solutions. If there is one constant throughout his comments on Vietnam, it is that a piecemeal, limited approach would be ultimately fruitless. He also firmly believed—even when he suggested a certain reticence about the conflict in 1963— that the United States could only achieve a quick victory if it Americanized the conflict. Greene and many senior Marine officers maintained this position throughout the first three years of direct American involvement in the conflict.56 Consequently, Greene believed that the Service chiefs, rather than civilians, should serve as Johnson’s principal advisors on Southeast Asia. Unsurprisingly, he was continually frustrated with the president’s tendency to defer decisions and avoid firm commitments when presented with difficult choices.

Thus, the proposal for a National General Staff was not only an attempt to improve the national security advisory system but also a means designed to force President Johnson to make a decision on Vietnam, which would have favored Greene’s own conclusions. Greene felt that the deactivation of the National Security Council’s formal planning boards and committees had allowed the president to defer difficult decisions. A rational and organized advisory system would force the president to take what the Commandant believed to be the best course of action in the Vietnam War.

However, as a number of scholars have demonstrated, the presence of a coherent foreign policy advisory structure would not guarantee that successive presidential administrations came to the best decisions concerning Vietnam.57 While Greene’s proposal was never implemented, it is difficult to imagine Lyndon Johnson using such an organization or al- lowing such an organization to force him to make a decision regarding the Vietnam War. The efforts of this most consummate professional military staff officer to engage the most consummate of politicians had decidedly mixed results.

• 1775 •

Endnotes

- Gen Wallace M. Greene Jr. Oral History collection conducted for Marine Corps History Division (Gray Research Center (GRC), Quantico, VA); Wallace M. Greene Papers: Notes on the Situation in South Vietnam (GRC, Quantico, VA). Greene’s personal papers exist in two collections. The first collection contained unclassified material covering his entire career in the Marine Corps. The second, designated Notes on the Situation in South Vietnam, entails 12 boxes focusing only on the Vietnam War. This material has only recently been declassified. Since the Marine Corps Archives is currently working on organizing the two collections, the author refers to the collections as Greene Papers and Greene Papers: Vietnam Notes to simply, but clearly, differentiate between the two sets.

- George C. Herring, LBJ and Vietnam: A Different Kind of War (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1994); H. R. McMaster, Dereliction of Duty: Lyndon Johnson, Robert McNamara, the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Lies that Led to Vietnam (New York: Harper Collins, 1997); David M. Barrett, Uncertain Warriors: Lyndon Johnson and His Vietnam Advisers (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1993); David Halberstam, The Best and the Brightest (Greenwich, NY: Fawcett Publications, 1972); and Robert Buzzanco, Masters of War: Military Dissent and Politics in the Vietnam Era (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

- McMaster, Dereliction of Duty, 326–33.

- Fredrik Logevall, Choosing War: The Lost Chance for Peace and the Escalation of War in Vietnam (Oakland: University of California Press, 1999).

- The best scholarly account of Greene’s life is the chapter by Allan R. Millett in Commandants of the Marine Corps, ed. Allan R. Millett and Jack Shulimson (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2004), 381–401.

- Ibid., 384.

- McMaster, Dereliction of Duty, 108–9.

- An act to fix the personnel strength of the United States Marine Corps, and to establish the relationship of the Commandant of the Marine Corps to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Pub. L. No. 82-416, 66 Stat. 677 (1952).

- Wallace M. Greene Jr. Oral History, 21 September 1971, Greene Papers, Vietnam Notes (GRC, Quantico, VA), hereafter Greene Oral History, 21 September 1971.

- Douglas Kinnard, The Certain Trumpet: Maxwell Taylor and the American Experience in Vietnam (New York: Brassey’s Inc., 1991), 56–73.

- Gen Maxwell D. Taylor, Swords and Plowshares (New York: W. W. Norton and Co., 1972), 252.

- See McMaster, Dereliction of Duty, 14–17; Kinnard, The Certain Trumpet, 74–79; and Mark Perry, Four Stars (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1989),121–22.

- Greene Oral History, 21 September 1971.

- Ibid.

- “A Marine Corps View of Military Strategy,” question-and-answer session (audio file), HD 6276 (Marine Corps History Division: Quantico, VA).

- Buzzanco, Masters of War, 157. Buzzanco makes two mistakes when citing this particular speech: he states it was delivered at Headquarters Marine Corps when it was in fact delivered at the Army War College, and he states it was delivered in “late 1963.” It was delivered in May 1963. See, Wallace M. Greene Jr., “A Marine Corps View of Strategy” (address delivered at the Army War College, Carlisle, PA, 8 May 1963). The mistakes are understandable in light of the lack of information appended to the audio recordings on file in the Greene Papers at the Marine Corps History Division.

- “A Marine Corps View of Military Strategy,” HD 6276.

- Ibid.

- “Commandant of the Marine Corps Trip Report for Visit to South Vietnam, January 1964,” Greene Papers, Vietnam Notes, GRC.

- “Outline Staff Study, Subj: Alternate Courses of Action, Vietnam, 21 February 1964,” attached to “Memorandum for the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Subj: Alternative Courses of Action, Vietnam, 13 March 1964,” Greene Papers, Vietnam Notes, GRC, hereafter “Outline Staff Study,” 21 February 1964. Emphasis by author.

- “Clark M. Clifford: 9th Secretary of Defense,” Department of Defense, accessed 8 September 2014, http://www.defense.gov/specials/secdef_ histories/SecDef_09.aspx.

- For Shoup’s opposition to the Vietnam War, see Howard Jablon, “General David M. Shoup, U. S. M. C.: Warrior and War Protester,” Journal of Military History 60, no. 3 (1996): 513–38.

- “Outline Staff Study,” 21 February 1964. Emphasis by author.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. The quotes around “unpopular” are in the original document.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Meeting Summary, Joint Chiefs White House Conference with the President, 4 March 1964,” Greene Papers, Vietnam Notes, GRC, hereafter “Meeting Summary,” 4 March 1964.

- Ibid.

- “Notes for JCS Meeting, 5 March 1964,” Greene Papers, Vietnam Notes, GRC.

- “Memorandum from the Secretary of Defense to the President, 16 March 1964.” McNamara’s memorandum went through several iterations. The final version, which is annotated to reflect how it changed from its first version, is reproduced in Edward C. Keefer and Charles S. Sampson, ed., Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964–1968, Vol. I, Vietnam, 1964 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1992), 153–67.

- Ibid., 167.

- McMaster, Dereliction of Duty, 76–77; and Graham A. Cosmas, The Joint Chiefs of Staff and the War in Vietnam, 1960–1968, Part 2 (Washington, DC: Office of Joint History, Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2012), 36–38.

- Marine Corps memorandum to the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CMCM 31-64/AO38B8-jd), “Comments on the Secretary of Defense Draft Memorandum for the President, South Vietnam, dated 13 March 1964,” Greene Papers, Vietnam Notes, GRC.

- Ibid.

- Memorandum to the president from the secretary of defense, “South Vietnam,” 16 March 1964, LBJ Presidential Library, http://www.lbjlib.utexas.edu/johnson/archives.hom/nsams/nsam288.asp.

- Greene Oral History collection, Greene Papers, Vietnam Notes, GRC. For the Joint Chiefs of Staff memorandum laying out their criticisms of McNamara’s memorandum, see memorandum from the Joint Chiefs of Staff to the secretary of defense, “Draft Memorandum for the President, Subject ‘South Vietnam’,” 14 March 1964, Foreign Relations of the United States (Document no. 82), 149–50.

- “Summary of Discussion with Deputy Chief of Staff for Plans and Programs (LtGen Henry W. Buse Jr.) and Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force (Gen Curtis E. LeMay, USAF),” teleconference, 17 March 1964, Greene Papers, Vietnam Notes, GRC, hereafter “Summary of Discussion with Deputy Chief of Staff,” 17 March 1964.

- “Summary of Action in JCS Meeting, 18 March 1964,” Greene Papers, Vietnam Notes, GRC.

- Ibid.

- “Summary of Discussion with Deputy Chief of Staff,” 17 March 1964.

- McMaster, Dereliction of Duty, 4–5.

- “Remarks of Gen Wallace M. Greene Jr., USMC” (speech at Armed Forces Staff College, Norfolk, VA, 21 May 1964). The entirety of the document can be found in Greene Papers, GRC.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “Memorandum to Gen Greene from Gen Curtis E. LeMay, Chief of Staff, USAF, 19 August 1964,” Greene Papers, Vietnam Notes, GRC.

- Ibid.

- Memorandum to Gen LeMay from Gen Wallace M. Greene, “Re-Activation of the Machinery of the National Security Council, 27 August 1964, Enclosure 1: Organization of a National Staff,” Greene Papers, Vietnam Notes, GRC.

- “Summary of a Meeting with Mr. Bromley Smith, Special Assistant to the President for National Security Council Affairs, 17 June 1964,” Greene Papers, Vietnam Notes, GRC.

- Ibid.

- McMaster, Dereliction of Duty, 5–7; Buzzanco, Masters of War, 19–20; and Michael R. Beschloss, The Crisis Years: Kennedy and Khrushchev 1960–1963 (New York: Edward Burlingame Books, 1991), 146.

- “Remarks of Gen Wallace M. Greene Jr., USMC,” 21 May 1964.

- Herring, LBJ and Vietnam; Buzzanco, Masters of War; Barrett, Uncertain Warriors; McMaster, Dereliction of Duty; and Logevall, Choosing War.

- Douglas T. Stuart, Creating the National Security State: A History of the Law that Transformed America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008); and Adrian R. Lewis, The American Culture of War: The History of U.S. Military Force from World War II to Operation Iraqi Freedom (New York: Routledge, 2007).

- Nicholas J. Schlosser, “Reassessing the Marine Corps’ Approach to Strategy in the Vietnam War, 1965–1968,” International Bibliography of Military History 34, no. 1 (2014): 27–52.

- Barrett, Uncertain Warriors, 190–94; and Leslie H. Gelb and Richard K. Betts, The Irony of Vietnam: The System Worked (Washington, DC: Brookings, 1979), 1–6.