International Perspectives on Military Education

volume 3 | 2026

U.S. Military Distance Learning Research

A Systemic Review, 2000-2023

Rob S. Nyland, PhD

https://doi.org/10.69977/IPME/2026.001

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: This systematic review analyzed 41 peer-reviewed studies (2000–23) on U.S. military distance learning, addressing a critical gap in understanding its efficacy. Using a systematic methodology, the review synthesized findings from a diverse corpus. Key findings show research is predominantly theoretical or case study-based, focusing on student perceptions, satisfaction, and self-efficacy. While distance learning generally meets learning objectives and offers comparable outcomes to in-residence instruction, rigorous empirical assessments, particularly for organizational outcomes and learning mechanisms, are notably absent. The review highlights reliance on convenience samples and a lack of longitudinal studies, limiting generalizability. The author concludes that future scholarship must adopt more robust empirical designs (experimental/quasi-experimental) to definitively establish military distance learning efficacy. It also calls for greater emphasis on organizational readiness, instructor effectiveness, and nuanced learning mechanisms, moving beyond simple satisfaction metrics. These insights are crucial for optimizing professional military education and ensuring force readiness.

Keywords: distance learning, U.S. military, professional military education, PME, online learning

Online and distance education has rapidly emerged as a viable alternative to traditional in-residence higher education. This shift is evident in recent trends: the 2023 Changing Landscape of Online Education (CHLOE) report highlights stagnant or declining in-residence enrollments at higher education institutions, while online and hybrid offerings continue to expand.[1] The primary driver behind this increased demand for online learning is flexibility. For example, in-residence college students often take online courses for greater scheduling flexibility, while adult learners pursuing fully online degrees appreciate the ability to complete their studies while managing work and family responsibilities.[2]

Paralleling the growth in traditional higher education, the U.S. military has extensively adopted distance learning to offer flexible educational options for its forces. While tens of thousands of servicemembers complete distance education courses annually, there remains a critical lack of clarity regarding the efficacy and mechanisms of learning within U.S. military distance education. This persistent gap stems from several factors: first, the specialized nature of military distance education means research is not concentrated in specific, dedicated journals; second, personnel involved in military education are often mission-focused, limiting their capacity to conduct rigorous research. However, this absence of evidence cannot be overlooked. As the military continues to invest substantial resources in this educational modality, ensuring the adoption of evidence-based practices is paramount.

The aim of this systematic review is to map the methodological landscape of military distance learning research, identify content and Service-specific gaps, and recommend design directions that align with operational needs. In doing so, it offers the first consolidated evidence base for policymakers and instructional designers to inform future investments.

This work is guided by the following research questions:

• What research methods and data analysis techniques do researchers most often employ when studying the outcomes of distance education in U.S. military settings?

• What types of measures do researchers use in studies of distance education within U.S. military environments?

• What outcomes do empirical studies of U.S. military distance-learning programs report, and what patterns can be identified across these findings?

Background on Distance Learning in the Military

The U.S. military has a long history of developing distance education to enhance the training and education of its personnel. Michael Barry and Gregory B. Runyan extensively documented this evolution, beginning with the U.S. Navy’s print-based correspondence courses in the 1940s.[3] Innovation continued throughout the latter half of the twentieth century. In the 1950s, the U.S. Army experimented with television-delivered training, finding it as effective as traditional instruction.[4] The Air Force Institute of Technology introduced Teleteach in the 1970s, using telephone lines for voice delivery and later to transmit blackboard drawings to remote workshops.[5] By the 1990s, the U.S. Army moved to computer-based distance learning with the System for Managing Asynchronous Remote Training (SMART), offering asynchronous curriculum, communication tools, and assessments to Army Reserve members via telephone modem.[6]

This increasing emphasis on distance learning culminated around the turn of the century with the Department of Defense’s (DOD) creation of the Advanced Distributed Learning (ADL) initiative. ADL aimed to provide “a federal framework for using distributed learning to provide high-quality education and training, that can be tailored to individual needs and delivered cost-effectively, anytime and anywhere.”[7] At this time, the DOD defined distributed learning to encompass distance learning, defining it as “structured learning that takes place without requiring the physical presence of an instructor.”[8]

Despite its continued prevalence, the rise of distance learning in the military has faced significant critiques. A primary concern stems from the competitive admissions for in-resident professional military education (PME) schools, often leading to a perception that distance learning is inferior or merely an afterthought. For instance, Lieutenant Colonel Raymond A. Kimball and Captain Joseph M. Byerly argued that Army distance learning courses were solitary activities, lacking opportunities for peer social engagement.[9] Reinforcing this perception, Geoff Bailey and Ron Granieri found that distance learning in a PME environment was not seen as equivalent to in-resident learning. They noted that distance learners felt they missed out on crucial networking and relationship-building, and that distance learning was perceived as a deficit in material comprehension and practical application. They also reported significant performance differences on the Army’s Common Core Exam between in-resident and distance learners.[10] More recently, Major William L. Woldenberg criticized the Army’s distance-learning Captains Career Course for insufficient student interaction or activities that foster essential higher-order skills like critical thinking, as identified by the Joint Chiefs of Staff.[11] This scrutiny intensified in May 2024, when the Army suspended its 40-hour, fully online Distributed Leader Course to “eliminate redundancies across different instructional formats.”[12] While this action does not apply broadly, it signals a potential shift toward closer examination of the outcomes and effectiveness of military online education.

This long and varied history, coupled with ongoing debates and recent scrutiny regarding the efficacy of military distance learning, underscores the pressing need for a systematic and comprehensive review of the existing research, which this article aims to complete.

Methods

The inclusion criteria as well as rationale for each of the criteria is shown in table 1.

Table 1. Inclusion criteria

|

Criteria

|

Justification

|

|

Published in 2000 or later

|

In 1999, the Department of Defense launched the Advanced Distributed Learning initiative, marking the move from correspondence courses to web-based distance education. Limiting the review to studies published from 2000 onward ensures the author captures research relevant to this modern, online era.

|

|

Focus on the U.S. military

|

Education policies, rank structures, and resource constraints differ widely across nations. Restricting the review to U.S. programs keeps the findings directly useful for American PME decision-makers.

|

|

Appears in a peer-

reviewed journal or

edited book chapter

|

Peer review provides a baseline check on methodological quality and signals that the work has been vetted by the broader academic community. Theses and dissertations were excluded to maintain a consistent quality threshold.

|

|

Participants are learners enrolled in a U.S. military school

|

The study must examine students taking courses delivered by the U.S. military (e.g., Air War College, Naval Postgraduate School). The author excluded research on active-duty or veteran students attending civilian universities, because their learning environments and support systems differ from those in military-run programs.

|

Source: courtesy of the author.

The author searched EBSCO Academic Search Premier using the string (“military” or “veterans” or “soldiers” or “armed forces”) AND (“distance education” or “distance learning” or “online education” or “online learning”) AND ( “united states” or “america” or “u.s.a.” or “u.s” ). The peer-review filter reduced 475 hits to 229; manual screening yielded 41 eligible articles.

The author coded the eligible studies with a slightly modified version of Rob Nyland et al.’s procedure.[13] For each study, the author extracted the following key information (in addition to title, journal, and authorship):

• Branch of U.S. military

• Number of Google Scholar citations (as of November 2023)

• Data analysis methods

• Research results

• Research measures (e.g., grades, satisfaction)

Furthermore, the author assigned each publication to a broad research methodology category defined as follows:

• Theoretical/case study: These papers develop or combine ideas without using new data. These include literature reviews, essays on concepts, or discussions about new design ideas.

• Interpretive: These are studies that use qualitative methods like interviews, focus groups, or observations. They analyze this information to understand or explain a phenomenon.

• Inferential: These studies use statistics to test hypotheses or look at relationships between different factors. This includes experiments, correlation studies, or validating tools.

• Descriptive: Studies limited to descriptive statistics (e.g., means, standard deviations, frequency distributions, percentages), often derived from survey data, with no inferential testing.

• Combined: These investigations purposefully mix both quantitative (numbers) and qualitative (descriptions) methods to answer research questions. Most often, they blend inferential and interpretive approaches.

• Content analysis: This involves systematically coding and examining text or spoken data (like transcripts) to find patterns, themes, or how often certain things appear.

• Other: This category is for any research method that does not fit into the types listed above.

Beyond coding research methods, the author also categorized each study’s primary purpose. What started as notes evolved into distinct categories applied consistently across all studies. Ultimately, the author identified four key purposes: (1) evaluation of distance learning courses or programs; (2) learner attributes in online courses; (3) comparative outcomes of distance learning; and (4) faculty development for distance learning.

Similarly, the author identified the primary outcome domain for each study, representing the aspects of the distance learning experience researchers aimed to understand. The author established three domains for this: (1) learner experience (e.g., satisfaction, motivation, self-efficacy); (2) learning outcomes (e.g., grades, retention, skill gain); and (3) organizational readiness and culture (e.g., faculty development, policy, leadership buy-in). The full list of articles with their coded information is available in the appendix table. Quantitative tallies and visualizations were produced in Python; qualitative categories were refined iteratively in ChatGPT4 to ensure internal consistency.

Description of Corpus

This section describes the characteristics of the compiled corpus in terms of publication trends, military Service representation, publication venues, and authorship influence.

Publication Trends

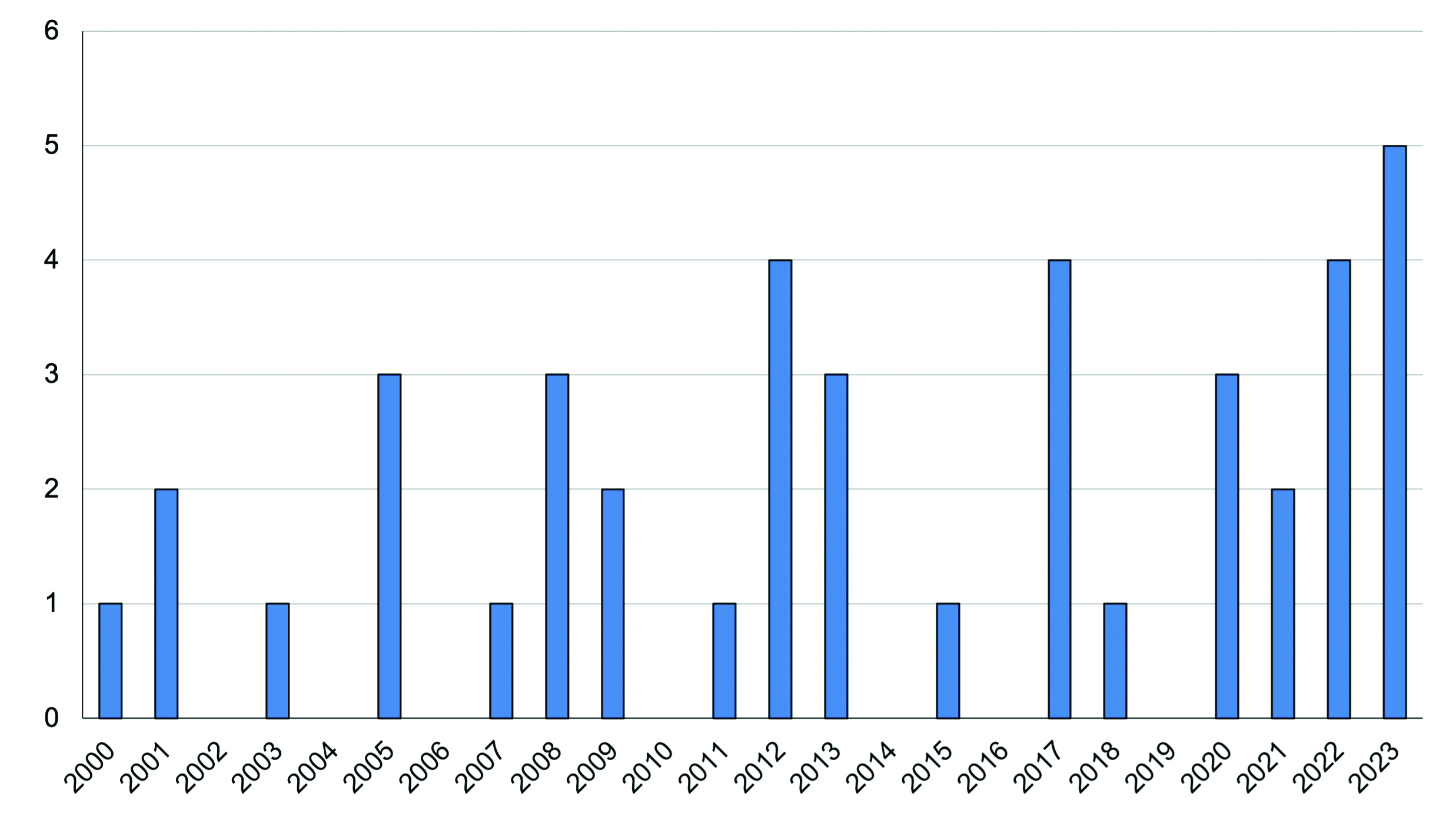

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of analyzed publications over time. While the number of publications has remained relatively consistent since 2000, a slight increase is observable after 2020. This recent uptick may reflect the amplified emphasis on distance learning spurred by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 1. Number of articles published per year, 2000–23

Source: courtesy of the author.

Military Service Representation

As detailed in the methods, the author coded each article for the U.S. military branch that conducted the study. Table 2 presents the distribution of studies across the Services. The U.S. Army was the most frequently represented Service, accounting for 31.7 percent of the analyzed publications. The U.S. Air Force and the Department of Defense at large were close, each comprising 26.8 percent of the publications.

Table 2. Service representation of analyzed publications

|

Service affiliation

|

Count

|

Percent

|

|

U.S. Army

|

13

|

31.7

|

|

U.S. Air Force

|

11

|

26.8

|

|

Department of Defense*

|

11

|

26.8

|

|

U.S. Navy

|

5

|

12.8

|

|

U.S. Marine Corps

|

1

|

2.6

|

*Note: denotes Joint collaboration between Services.

Source: courtesy of the author.

Publication Venues

The author also examined the most common peer-reviewed publication venues for research on distance learning in the U.S. military (table 3). Military Medicine emerged as the most frequent venue, followed by the Journal of Military Learning. This concentration suggests that military-specific journals are key outlets for research in this domain. While most of the corpus’s publications are not military-specific journals, the author observed a notable lack of similar concentration in any other single nonmilitary journal.

Table 3. Most common publications for U.S. military distance learning research

|

Publication name

|

Count

|

Percent

|

|

Military Medicine

|

7

|

17.1

|

|

Journal of Military Learning

|

5

|

12.2

|

|

The American Journal

of Distance Education

|

3

|

7.3

|

|

Military Review

|

2

|

4.9

|

|

Quarterly Review

of Distance Education

|

2

|

4.9

|

|

Distance Learning

|

2

|

4.9

|

|

Other*

|

20

|

48.7

|

*Note: other outlets with only one publication each.

Source: courtesy of author.

Most Prolific Authors (Medal System)

To identify the most prolific authors within the corpus, the author implemented a so-called “medal system” to weigh author contributions. Using this system, the first author received eight points, a second author seven points, a third author six points, and so on, down to one point for an eighth (or later) author. This methodology allowed for a nuanced assessment of total authorship contributions. Table 4 presents the results of this analysis for authors with at least two publications. Lauren Mackenzie and Jason Keys were tied for the highest medal points, each serving as first author on three publications.

Table 4. Medal counts for authors with at least two publications in U.S. military distance learning

|

Author

|

Number

of publications

|

Medal points

|

|

Mackenzie, Lauren

|

3

|

24

|

|

Keys, Jason

|

3

|

24

|

|

Artino, Anthony R.

|

2

|

16

|

|

Kenyon, Peggy L.

|

2

|

16

|

|

Myers, Susan R.

|

2

|

16

|

|

Boetig, Bradley

|

2

|

15

|

|

Wallace, Megan

|

2

|

14

|

|

Baines, Lyndsay S.

|

2

|

12

|

|

Jindal, Rahul M.

|

2

|

11

|

Source: courtesy of the author.

Article Impact (Google Scholar Citations)

To further assess authorship and influence, the author collected Google Scholar citation counts for each article in the corpus as of November 2023. Table 5 lists the most highly cited articles. It is important to acknowledge, however, that older articles typically accrue more citations due to their longer period of availability within the scholarly community. Based on this analysis, the top three most cited papers were Anthony R. Artino, Sherry L. Piezon and William D. Feree, and Anthony R. Artino and Jason M. Stephens.

Table 5. Top articles by number of Google Scholar citations (as of November 2023)

|

Author(s)

|

Year

|

Article title

|

Number of

citations

|

|

|

Artino,

Anthony R.

|

2007

|

Online military training: Using a Social Cognitive View of Motivation and Self-Regulation to Understand Students’ Satisfaction, Perceived Learning, and Choice

|

200

|

|

|

Piezon, Sherry L., and Feree, William D.

|

2008

|

Perceptions of Social Loafing in Online Learning Groups: A study of Public University and U.S. Naval War College students

|

171

|

|

|

Artino, Anthony R., and Stephens, J.

|

2009

|

Beyond Grades in Online Learning: Adaptive Profiles of Academic Self-Regulation Among Naval Academy Undergraduates

|

129

|

|

|

Treloar, David, Hawayek, Jose, Montgomery, Jay R., and Russell, Warren

|

2001

|

On-Site and Distance Education of Emergency Medicine Personnel with a Human Patient Simulator

|

63

|

|

|

Duncan, Steve

|

2005

|

The U.S. Army’s Impact on The History of Distance Education

|

59

|

|

|

Miller, John W., and Tucker, Jennifer S.

|

2015

|

Addressing and Assessing Critical Thinking in Intercultural Contexts: Investigating the Distance Learning Outcomes of Military Leaders

|

38

|

|

|

Sitzmann, Traci, Brown, Kenneth, Ely, Katherine, Kraiger, Kurt, and Wisher, Robert A.

|

2009

|

A Cyclical Model of Motivational Constructs in Web-Based Courses

|

26

|

|

|

Barker, Bradley, and Brooks, David

|

2005

|

An Evaluation of Short-term Distributed Online Learning Events

|

23

|

|

Source: courtesy of the author.

While the previous analyses described the characteristics of the corpus, the discussion will now transition to answering the research questions through additional analysis.

Results

Research Question 1: Research Methods and Frameworks

To address the first research question, concerning the most frequently used research methods and frameworks in military distance learning studies, the author first analyzed the distribution of research frameworks employed across the corpus. As shown in table 6, theoretical/case studies were the predominant framework, comprising 56.1 percent of the publications, significantly outweighing other approaches. Inferential studies followed, representing 29.3 percent of the corpus. Conversely, the descriptive, combined, and interpretive frameworks were much less common, collectively accounting for less than 15 percent of the publications.

Table 6. Most used research frameworks

|

Framework

|

Counts

|

Percent

|

|

Theoretical/case study

|

23

|

56.1

|

|

Inferential

|

12

|

29.3

|

|

Descriptive

|

3

|

7.3

|

|

Combined

|

2

|

4.9

|

|

Interpretive

|

1

|

2.4

|

Source: courtesy of the author.

It is important to note that articles categorized as theoretical/case studies typically present specific implementations of distance learning programs, detailing their goals, constraints, and technological aspects. However, these publications often included only informal lessons learned and lacked empirical data to rigorously investigate program outcomes. This highlights a prevalent characteristic of research in this domain: a focus on programmatic descriptions rather than empirical assessment of effectiveness.

Focusing on the empirical studies (those categorized as inferential, descriptive, combined, or interpretive), the author further examined the specific data analysis methods employed. Table 7 summarizes these findings, noting that studies could use multiple methods.

Table 7. Most used data analysis methods

|

Data analysis method

|

Number of publications using method

|

|

Correlation

|

4

|

|

Factor analysis (EFA and CFA)

|

3

|

|

T-test

|

3

|

|

Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test

|

2

|

|

Qualitative

|

2

|

|

MANOVA/ANOVA

|

2

|

|

Hierarchical linear modeling

|

1

|

|

Linear regression

|

1

|

|

Propensity score matching

|

1

|

|

Difference

|

1

|

|

Mann-Whitney U

|

1

|

|

Descriptive statistics

|

1

|

EFA=exploratory factor analysis; CFA=confirmatory factor analysis; MANOVA=multivariate analysis of variance; ANOVA=analysis of variance.

Source: courtesy of the author.

Researchers most often used correlation as their data-analysis method, using it in four publications to investigate linear relationships between variables. Factor analysis (both exploratory and confirmatory), which identifies underlying measurement structures, and t-tests were the next most common, each appearing in three publications. The remaining methods, apart from descriptive statistics and difference analyses, primarily involved various parametric or nonparametric inferential statistics to assess the impact of study factors.

Notably, only two articles within the entire corpus employed qualitative data analysis methods: one was a purely interpretive qualitative study, and the other was a combined (mixed-methods) study. This underscores a strong quantitative leaning within the empirical research on military distance learning.

Research Question 2: Types of Measures Used

The second research question investigated the types of measures employed to assess outcomes in military distance learning environments. For this purpose, the author coded each article to identify its operationalized research measures. As depicted in table 8, course satisfaction, self-efficacy, general student perceptions, and student grades were the most frequently used measures. Specifically, researchers used satisfaction in 17.1 percent of the publications, while self-efficacy and student perceptions each appeared in 12.2 percent of studies. Researchers reported student grades in 9.8 percent of the articles.

Table 8. Most used measures for research about distance learning in the U.S. military

|

Measure

|

Number of

publications using measure

|

Percent of

publications using measure

(N=41)

|

|

Satisfaction

|

7

|

17.1

|

|

Self-efficacy

|

5

|

12.2

|

|

Student grades/performance

|

4

|

9.8

|

|

Student perceived learning

|

3

|

7.3

|

|

Motivation

|

3

|

7.3

|

|

Task visibility

|

2

|

4.9

|

|

Instructor effectiveness/

performance

|

2

|

4.9

|

Source: courtesy of the author.

Research Question 3: Study Outcomes

For the final research question, the author wanted to examine the outcomes of the studies included in the systematic review. As the purposes and methods varied widely across the studies, it is difficult to compare them in ways that would be done in a traditional meta-analysis. The goal here is therefore to summarize the types of findings that were reported in the studies by their purpose as well as outcome domain. To analyze this, the author coded the primary purpose and outcome domains of each of the empirical studies, that is, studies that were not coded with the theoretical/case study method. The rationale is that these studies were typically set up as showcasing the design of a distance learning program and did not report any outcomes that were derived from research process. As the purpose of this study is to look at research outcomes, the author chose to restrict to these areas.

Of the 21 studies that were coded as empirical, two domains dominated: learner experience (e.g., student satisfaction, engagement) and learner outcomes (e.g., grades, pass-rates). Each of these domains accounted for approximately 40 percent of the empirical studies (table 9).

Table 9. Primary outcome domains for assessed empirical studies

|

Outcome domains

|

Number of

publications using domain

|

Percent of

empirical publications in domain

(N = 18)

|

|

Learner experience

(satisfaction, motivation, etc.)

|

8

|

38.1

|

|

Learning outcomes (grades, pass rates, skills)

|

8

|

38.1

|

|

Organizational readiness

and culture

|

2

|

11.1

|

Source: courtesy of the author.

In terms of purpose, one-half of the empirical studies were focused on evaluating a distance learning course or program. Other reported purposes included comparing outcomes of distance learning and resident courses, examining learner attributes in an online course, and exploring faculty development for distance learning (table 10).

Table 10. Primary research purposes of empirical studies

|

Purpose category

|

Number of publications with purpose

|

Percent of

empirical publications with purpose (N = 18)

|

|

Evaluation of a distance learning course or program

|

9

|

50.0

|

|

Comparative outcomes (distance learning versus resident)

|

4

|

22.2

|

|

Learner attributes in an online course

|

3

|

16.7

|

|

Faculty development

|

2

|

11.1

|

Source: courtesy of the author.

Discussion

This study systematically reviewed literature on distance learning in U.S. military environments published since 2000. The primary goal was to understand current research trends and identify avenues for future growth.

The first research question explored the most frequently used research methods. More than one-half of the analyzed articles were theoretical or case studies. After closer examination, these articles typically presented either a description of a military distance learning program or an argument for its implementation or quality improvement. While such reports are valuable for disseminating information about distance learning initiatives, the author contends there is a critical need for greater empirical evaluation of program effectiveness. As distance learning becomes increasingly common in the U.S. military, building a robust body of evidence-based research can strengthen claims about its efficacy and address the criticisms noted earlier in this review.

Beyond theoretical works, inferential statistical research constituted the next largest category, accounting for 30 percent of the corpus. The detailed methodological analysis revealed a diverse array of statistical techniques, ranging from simpler descriptive statistics to more complex methods like propensity score matching and hierarchical linear modeling. While the choice of analysis methodology is always contingent on project resources and specific research questions, the author observed a notable absence of more recent machine learning or data-intensive models. Given the increasingly digital nature of educational data and growing accessibility of artificial intelligence, the author anticipates future research will increasingly explore these advanced analytical approaches.

A significant finding regarding methodology is the underrepresentation of interpretive frameworks, with only the article by Jason Keys, Demetrius N. Booth, and Patricia R. Maggard employing this approach.[14] This suggests a potential bias toward positivist research paradigms within the U.S. military distance learning community. Addressing this blind spot by incorporating more interpretive methods could provide invaluable insights into the lived experiences of students and instructors in military distance learning environments. Such qualitative investigations are crucial for fostering more user-centered and effective learning experiences.

For the second research question, the author examined the common measures used across the corpus. The analysis revealed that while a diversity of measures was evident, researchers most frequently employed student satisfaction, general student perceptions, and grades as outcome measures. Additionally, self-efficacy emerged as a recurrent measure, aligning with findings from broader distance learning research.[15] The observed variety in measures used to explore specific research questions is promising, and the author anticipates this diversity will continue to grow as data from learning environments become increasingly accessible.

For the final research question, the author looked more specifically at the outcomes of the empirical research studies included in the review. In this realm, they examined both the purpose of the study as well as the outcome domain that it used. For the purposes of summarizing the findings, they synthesized the outcomes across each research purpose.

Evaluation of Distance Learning Courses or Programs

Studies in this category evaluated whether distance learning programs in military contexts achieved intended outcomes such as learning gains, satisfaction, or operational effectiveness. Across diverse domains—ranging from professional development to clinical practice guidelines—results were broadly positive. For example, Bradley Barker and David Brooks found that 88 percent of students felt well-prepared for their in-resident phase, and most learners gave high ratings to course relevance and delivery technologies.[16] Similarly, Shelby Edwards et al. reported statistically significant knowledge gains after post-traumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder training, with most learners expressing confidence in applying course concepts on the job.[17]

Multiple studies highlighted usability and learner satisfaction. Su Yeon Lee-Tauler et al. found that their suicide-prevention intervention was rated highly on ease of use, relevance, and applicability.[18] Lauren Mackenzie and Megan Wallace observed significant improvements in cultural self-efficacy and learning gains across pre- and post-tests.[19] Studies by Susan R. Myers and John W. Miller and Jennifer S. Tucker emphasized cognitive development and critical thinking among military leaders, reporting improvements in systems thinking and decision-making.[20]

A few studies investigated technology-supported collaborative or immersive learning. For example, David Treloar et al. demonstrated improvements in perceived preparedness using human patient simulators for emergency medicine personnel.[21] Traci Sitzmann et al. modeled motivational trajectories across web-based courses, showing that personality traits like agreeableness and conscientiousness influenced course expectations and engagement, although motivation declined over time without reinforcement.[22] Overall, these studies demonstrate that military distance learning programs can achieve cognitive, motivational, and performance objectives, particularly when they support learner interaction and autonomy. However, two limitations temper these conclusions. First, the simulated or online activities could not replace the full range of hands-on experience required for some operational tasks. Second, few of the studies established a baseline comparison group or pre-intervention measure, leaving unanswered whether the reported benefits stem from the distance-learning environment or from factors such as course design, cognitive development and maturation, or instructor enthusiasm.

Comparative Outcomes of Distance Learning versus Residential Education

These studies compared student outcomes across online and in-residence formats. Results generally suggested that distance learning can achieve outcomes equivalent to face-to-face learning, though with important contextual considerations. Marigee Bacolod and Latika Chaudhary used a large dataset to show that while distance MBA students earned more As than their resident peers, they had higher attrition rates and lower promotion rates post-graduation, especially in engineering programs.[23]

Other studies focused on course-specific comparisons. Jason Keys observed higher grades in online PME settings during the COVID-19 pivot, although causality remains unclear.[24] Stephen Hernandez et al. found that students in converted online courses rated instructors as more knowledgeable and reported greater satisfaction on many measures than in pre-COVID face-to-face formats.[25] Walter R. Schumm and David E. Turek reported that distance students experienced less peer bonding but rated convenience and flexibility highly, citing up to six hours saved monthly in commuting time.[26] Together, these studies indicate that while academic outcomes are largely comparable, social integration and experiential elements may be reduced in distance learning formats.

Learner Attributes in an Online Course

These studies examined personal and motivational traits that influence student performance in online military education. Anthony R. Artino showed that high task value and self-efficacy significantly predicted perceived learning and satisfaction. When participation was voluntary and self-paced, outcomes improved, suggesting that learner autonomy plays a critical role in distance learning success.[27]

Building on this, Anthony R. Artino and Jason M. Stephens found that self-regulation and experience with online learning predicted deeper cognitive engagement and course satisfaction. Conversely, students who felt bored or frustrated, especially those lacking self-regulation skills, performed poorly.[28] Sherry L. Piezon and William D. Ferree examined group dynamics, showing that perceptions of fairness and task clarity reduced social loafing—a tendency to reduce individual effort when working in groups—while dominance in group settings increased it.[29] These findings suggest that distance learning success is closely tied to students’ ability to manage their learning, navigate social dynamics, and sustain intrinsic motivation.

Faculty Development

Faculty development studies were limited but valuable. Jason Keys found that self-efficacy among enlisted PME instructors was high overall, especially when they had support from instructional design experts. Teaching efficacy did not vary significantly by instructor rank or teaching experience but did improve when instructors engaged with support personnel.[30]

In a qualitative follow-up, Jason Keys, Demetrius Booth, and Patricia Maggard reported that instructors relied on pre-Service training and their military supervisory experience to manage online classrooms. While training covered basic learning management system functions, instructors expressed a need for more hands-on guidance. Engagement strategies were often modeled during the training, but mastery developed over time.[31] These studies suggest that instructor preparation is sufficient to get educators started in distance learning, but deeper instructional design partnerships and ongoing training may be necessary to optimize performance.

Implications and Future Research

The present review offers the distance learning community in U.S. military settings its first consolidated map of what is known and, more importantly, what remains unknowable based on current research practices. From this review, most published work is still descriptive: theoretical essays that explain why distance matters or case reports that narrate how a single course or program was built. Those genres may have been helpful in the 2000s, when web-based delivery was new and institutions needed “proof of concept.” Twenty-five years later, however, military education and training has moved from adoption to optimization. Future scholarship therefore must shift from treating distance merely as a convenient setting for research to treating it as a phenomenon with distinctive attributes—geographic dispersion, asynchronous pacing, reduced social presence, and technology mediation—that shape learning in ways resident programs do not.

Three research consideration pivots follow from that insight. First, design questions should target distance learning specific mechanics: Which combinations of synchronous touchpoints and asynchronous autonomy produce the highest knowledge retention for students deployed across time zones? How much instructor presence is needed to prevent the well-documented motivation decline identified by Sitzmann and colleagues? Second, researchers must abandon convenience samples—for example, surveying a cohort simply because it happens to be online—and instead select samples or create experimental contrasts that isolate distance learning variables. Third, new instructional ideas should be advanced only with accompanying evidence. A virtual-reality module or artificial intelligence tutor may be innovative, but without data on learning gain, workload, or cost, its value is speculative. Although novel ideas still have a place, the field should toward an expectation that new approaches come with supporting evidence, so that claims of effectiveness rest on more than novelty alone.

Limitations

A notable limitation of this study is its exclusive focus on peer-reviewed journal articles and book chapters. This scope necessarily excludes a significant body of literature, particularly doctoral dissertations, many of which are authored by military officers with deep insights into military distance learning. Future research could greatly benefit from systematically examining these dissertations to uncover additional perspectives and findings.

Furthermore, this review could not account for unpublished internal research conducted by military distance learning organizations. These organizations undoubtedly undertake informal or internal evaluations to improve their programs, but such data is often not intended for public consumption or has not undergone the processes required for public dissemination. Consequently, these valuable internal findings are absent from this systematic review.

Conclusion

This systematic analysis of 41 peer-reviewed studies reveals a field still dominated by theoretical exposition and single-course narratives. Only 18 articles employed empirical methods robust enough to draw causal or even correlational inferences about

distance-learning effectiveness. Within that empirical subset, learner satisfaction and academic grades were the most common outcomes; organizational readiness, technology reliability, cost, and social-presence effects were largely ignored.

To move the field forward, researchers must now exploit the distinctive affordances and constraints of distance learning environments rather than treating those environments as interchangeable with resident classrooms. By pairing innovative designs with rigorous evidence—experimental contrasts, cost-benefit analyses, and rich qualitative tracing of learner and instructor experience—the PME community can build a knowledge base that supports mission readiness, resource stewardship, and the long-term professional development of Joint Force personnel.

Appendix table. Reviewed articles by year

|

Authors

|

Year

|

Branch of U.S. Service

|

Method

|

Data analysis tags

|

Captured measures

|

Primary

purpose

|

Primary outcome domain

|

|

McCarthy-

McGee, A. F.

|

2000

|

Army

|

Theoretical/case study

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

|

Rivero, C.,

Mittelstaedt, E., and Bice-

Stephens, W.

|

2001

|

Army

|

Theoretical/case study

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

|

Treloar, D., Hawayek, J., Montgomery, J., and Russell, W.

|

2001

|

Navy

|

Inferential

|

Wilcoxon signed-rank

|

Self-efficacy

Preparedness

|

Evaluation

|

Learning outcomes

|

|

Schumm, W., and Turek, D.

|

2003

|

Army

|

Inferential

|

T-test

|

Satisfaction

Instructor effectiveness

|

Comparative outcomes

|

Learner

experience

|

|

Barker, B., and Brooks, D.

|

2005

|

DOD

|

Inferential

|

Factor analysis

|

Motivation

Previous learning

Perceived learning

Course

usability

|

Evaluation

|

Learning outcomes

|

|

Beason, C.

|

2005

|

DOD

|

Theoretical/case study

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

|

Duncan, S.

|

2005

|

Army

|

Theoretical/case study

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

|

Artino, A.

|

2007

|

Navy

|

Inferential

|

Correlation

|

Experience with online learning

Task value

Self-efficacy

Satisfaction

Perceived learning

Future

enrollment

|

Learner

attributes

|

Learner

experience

|

|

Douthit, G.

|

2008

|

Marine Corps

|

Theoretical/case study

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

|

Myers, S.

|

2008

|

Army

|

Combined

|

T-test

|

Modified Career Path Appreciation (MCPA) Survey

|

Evaluation

|

Learning outcomes

|

|

Piezon, S., and Ferree, W.

|

2008

|

Navy

|

Inferential

|

Correlation

|

Social loafing

Task visibility

Contribution

Distributive justice

Sucker effect

Dominance

|

Learner

outcomes

|

Learner

experience

|

|

Artino, A., and Stephens, J.

|

2009

|

Navy

|

Inferential

|

Factor analysis

MANOVA

|

Self-efficacy

Task value

Boredom

Frustration

Elaboration

Metacognition

Satisfaction

Motivation to continue

Grades

|

Learner

attributes

|

Learner

experience

|

|

Sitzmann, T., Brown, K. G., Ely, K., Kraiger, K., and Wisher, R.

|

2009

|

DOD

|

Inferential

|

Hierarchical linear modeling

|

Personality

Course

expectations

Motivation

Training

reactions

Learning

|

Evaluation

|

Learner

experience

|

|

Gruszecki, L.

|

2011

|

DOD

|

Theoretical/case study

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

|

Badiru, A., and Jones, R.

|

2012

|

Air Force

|

Theoretical/case study

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

|

Kenyon, P., Twogood, G., and Summerlin, L.

|

2012

|

Department of Defense

|

Theoretical/case study

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

|

Lenahan-

Bernard, J.

|

2012

|

Army

|

Theoretical/case study

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

|

Mackenzie, L., and Wallace, M.

|

2012

|

Air Force

|

Descriptive

|

Difference

|

Student

perceptions

Knowledge gains

|

Evaluation

|

Learning outcomes

|

|

Kimball, R., and Byerly, J.

|

2013

|

Army

|

Theoretical/case study

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

|

Mackenzie, L., Fogarty, P., and Khachadoorian, A.

|

2013

|

Air Force

|

Theoretical/case study

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

|

Mackenzie, L., and Wallace, M.

|

2013

|

Air Force

|

Inferential

|

Correlation

ANOVA

|

Wiki

participation

Grades

Situational judgment test

Satisfaction

Retention

|

Evaluation

|

Learning outcomes

|

|

Miller, J., and Tucker, J.

|

2015

|

Air Force

|

Descriptive

|

Correlation

|

Critical

thinking

Intercultural competence

Student

perceptions

|

Evaluation

|

Learning outcomes

|

|

Bailey, L., and Bankus, T.

|

2017

|

Army

|

Theoretical/case study

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

|

Baines, L., Boetig, B., Waller, S., and Jindal, R.

|

2017

|

DOD

|

Theoretical/case study

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

|

Culkin, D.

|

2017

|

Army

|

Theoretical/case study

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

|

Fortuna, E.

|

2017

|

Army

|

Theoretical/case study

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

|

Bacolod, M., and Chaudhary, L.

|

2018

|

Navy

|

Inferential

|

Linear

regression

Propensity score matching

|

Graduation rate

Grades

Promotion rate

Military

separation

|

Comparative outcomes

|

Learning outcomes

|

|

Boetig, B., Kumpf, J.,

Jindal, R., Lawry, L., Baines, L., and Cullison, T.

|

2020

|

DOD

|

Theoretical/case study

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

|

Kenyon, P.

|

2020

|

Army

|

Theoretical/case study

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

|

Nguyen, C., DeNeve, D., Nguyen, L., and Limbocker, R.

|

2020

|

Army

|

Theoretical/case study

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

|

Cahill, J.,

Kripchak, K., and McAlpine, G.

|

2021

|

Air Force

|

Theoretical/case study

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

|

Keys, J.

|

2021

|

Air Force

|

Inferential

|

Factor analysis

|

Self-efficacy

|

Faculty

development

|

Organizational readiness

|

|

Hernandez, S., Dukes, S., Howarth, V., Nipper, J., and Lazarus, M.

|

2022

|

Air Force

|

Inferential

|

Mann-

Whitney U

|

Student perceptions

|

Comparative outcomes

|

Learner

experience

|

|

Hostetter, S.

|

2022

|

Air Force

|

Theoretical/case study

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

|

Keys, J.

|

2022

|

Air Force

|

Inferential

|

T-test

|

Student

perceptions

Process data

Grades

Course

disenrollment

|

Comparative outcomes

|

Learning outcomes

|

|

Keys, J., Booth, D., and

Maggard, P.

|

2022

|

Air Force

|

Interpretive

|

Qualitative analysis

|

Self-efficacy

Locus of control

Instructor effectiveness

Student

perceptions

Student engagement

Classroom management

Technology use

|

Faculty

development

|

Organizational readiness

|

|

Edwards, S., Edwards-

Stewart, A., Dean, C., and Reddy, M.

|

2023

|

DOD

|

Combined

|

Wilcoxon signed ranks

|

Learning assessment

Satisfaction

Learning perception

|

Evaluation

|

Learner

experience

|

|

Kurzweil, D., Macaulay, L., and Marcellas, K.

|

2023

|

DOD

|

Theoretical/case study

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

|

Lee-Tauler, S. Y., Grammer, J., LaCroix, J., Walsh, A. K., Clark, S. E., Holloway, K. J., Sundararaman, R., and Carter, K.

|

2023

|

DOD

|

Combined

|

Descriptive

Qualitative

|

Satisfaction

Time

estimation

|

Evaluation

|

Learner

experience

|

|

Myers, S., and Groh, J.

|

2023

|

Army

|

Theoretical/case study

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

|

Samuel, A., Teng, Y., Soh, M., King, B., Cervero, R., and Durnging, S.

|

2023

|

DOD

|

Theoretical/case study

|

N/A

|

Technology confidence

|

Evaluation

|

Learner

experience

|

Endnotes

[1] Richard Garrett et al., CHLOE 8: Student Demand Moves Higher Ed toward a Multi-Modal Future (Annapolis, MD: Quality Matters & Eduventures Research, 2023), https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.31114.18880.

[2] Kristy Lauver et al., “Preference of Education Mode: Examining the Reasons for Choosing and Perspectives of Courses Delivered Entirely Online,” Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education 5, no. 1 (April 2013): 113–28, https://doi.org/10.1108/17581181311310315; Timothy Braun, “Making a Choice: The Perceptions and Attitudes of Online Graduate Students,” Journal of Technology and Teacher Education 16, no. 1 (2008): 63–92; and Mark Shay and Jennifer Rees, “Understanding Why Students Select Online Courses: Criteria They Use in Making That Selection,” International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning 1, no. 5 (2004).

[3] Michael Barry and Gregory B. Runyan, “A Review of Distance-learning Studies in the U. S. Military,” American Journal of Distance Education 9, no. 3 (1995): 37–47, https://doi.org/10.1080/08923649509526896.

[4] Joseph H. Kanner, Richard P. Runyon, and Otello Desiderato, Television in Army Training: Evaluation of Television in Army Basic Training (Alexandria, VA: Office of Education, U.S. Department of Health, Education & Welfare, 1954), 61.

[5] G. Ronald Christopher and Alvin L. Milam, Teleteach Expanded Delivery System: Evaluation (Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, OH: Air Force Institute of Technology, 1981).

[6] Heidi A. Hahn et al., Distributed Training for the Reserve Component: Course Conversion and Implementation Guidelines for Computer Conferencing (Idaho Falls, ID: U.S. Army Research Institute for Behavioral and Social Sciences, 1990).

[7] Department of Defense Implementation Plan for Advanced Distributed Learning (Washington, DC: Office of the Deputy Undersecretary of Defense, 2000), ES-1.

[8] Department of Defense Implementation Plan for Advanced Distributed Learning, ES-2.

[9] LtCol Raymond A. Kimball and Capt Joseph M. Byerly, “To Make Army PME Distance Learning Work, Make It Social,” Military Review 93, no. 3 (May–June 2013): 30–38.

[10] Geoff Bailey and Ron Granieri, “We’ve Got to Do Better: Distance Education,” podcast, War Room, 25 May 2021.

[11] Maj William L. Woldenberg, “End the Professional Military Education Equivalency Myth,” Military Review, March 2023.

[12] Steve Beynon, “Army Eliminates Online Training Requirement for Noncommissioned Officers, Saying It’s Too Burdensome,” Military.com, 15 May 2024.

[13] Rob Nyland et al., “Journal of Educational Computing Research, 2003–2012,” Educational Technology 55, no. 2 (2015).

[14] Jason Keys, Demetrius N. Booth, and Patricia R. Maggard, “Examining the Efficacy of Pre-Service Training for Enlisted Professional Military Education Instructors During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Open Journal for Educational Research 6, no. 1 (2022): 1–18, https://doi.org/10.32591/coas.ojer.0601.01001k.

[15] Emtinan Alqurashi, “Self-Efficacy in Online Learning Environments: A Literature Review,” Contemporary Issues in Education Research (CIER) 9, no. 1 (2016): 45–52, https://doi.org/10.19030/cier.v9i1.9549.

[16] Bradley Barker and David Brooks, “An Evaluation of Short-Term Distributed Online Learning Events,” International Journal on E-Learning 4, no. 2 (2005): 209–28.

[17] Shelby Edwards et al., “Evaluation of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder and Acute Stress Disorder VA/DOD Clinical Practice Guidelines Training,” Military Medicine 188, nos. 5–6 (2023): 907–13, https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usac105.

[18] Su Yeon Lee-Tauler et al., “Pilot Evaluation of the Online ‘Chaplains-CARE’ Program: Enhancing Skills for United States Military Suicide Intervention Practices and Care,” Journal of Religion and Health 62, no. 6 (December 2023), https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-023-01882-9.

[19] Lauren Mackenzie and Megan Wallace, Cross-Cultural Communication Contributions to Professional Military Education: A Distance Learning Case Study (Maxwell Air Force Base, AL: Air University, 2013).

[20] Susan R. Myers, “Senior Leader Cognitive Development Through Distance Education,” American Journal of Distance Education 22, no. 2 (2008): 110–22, https://doi.org/10.1080/08923640802039057; and John W. Miller and Jennifer S. Tucker, “Addressing and Assessing Critical Thinking in Intercultural Contexts: Investigating the Distance Learning Outcomes of Military Leaders,” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 48 (September 2015): 120–36, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.07.002.

[21] D. Treloar et al., “On-Site and Distance Education of Emergency Medicine Personnel with a Human Patient Simulator,” Military Medicine 166, no. 11 (2001): 1003–6, https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/166.11.1003.

[22] Traci Sitzmann et al., “A Cyclical Model of Motivational Constructs in Web-Based Courses,” Military Psychology 21, no. 4 (2009): 534–51, https://doi.org/10.1080/08995600903206479.

[23] Marigee Bacolod and Latika Chaudhary, “Distance to Promotion: Evidence from Military Graduate Education,” Contemporary Economic Policy 36, no. 4 (October 2018): 667–77, https://doi.org/10.1111/coep.12275.

[24] Jason Keys, “Comparing In-Person and Online Air Force Professional Military Education Instruction during the COVID-19 Pandemic, ” Journal of Military Learning (October 2022): 3–18.

[25] Stephen Hernandez et al., “Examination of Military Student and Faculty Opinions and Outcomes of Two Rapid Course Conversions to the Online Environment: A Case Study at the United States Air Force School of Aerospace Medicine,” American Journal of Distance Education 36, no. 4 (2022): 318–26, https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2022.2121518.

[26] Walter R. Schumm and David E. Turek, “Distance-Learning: First CAS3 Class Outcomes,” Military Review 83, no. 5 (November–December 2003): 66–70.

[27] Anthony R. Artino Jr., “Online Military Training: Using a Social Cognitive View of Motivation and Self-Regulation to Understand Students’ Satisfaction, Perceived Learning, and Choice,” Quarterly Review of Distance Education 8, no. 3 (2007): 191–202.

[28] Anthony R. Artino Jr. and Jason M. Stephens, “Beyond Grades in Online Learning: Adaptive Profiles of Academic Self-Regulation Among Naval Academy Undergraduates,” Journal of Advanced Academics 20, no. 4 (2009): 568–601, https://doi.org/10.1177/1932202X0902000402.

[29] Sherry L. Piezon and William D. Ferree, “Perceptions of Social Loafing in Online Learning Groups: A Study of Public University and U.S. Naval War College Students,” International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 9, no. 2 (2008), https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v9i2.484.

[30] Jason Keys, “Teaching Efficacy of U.S. Air Force Enlisted Professional Military Educators during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Journal of Military Studies 10, no. 1 (2021): 46–59, https://doi.org/10.2478/jms-2021-0002.

[31] Keys, Booth, and Maggard, “Examining the Efficacy of Pre-Service Training for Enlisted Professional Military Education Instructors during the COVID-19 Pandemic.”

About the Author

Rob Nyland, PhD, is an assistant professor and director of research at the Air Force Global College at Air University (U.S. Air Force). Prior to working at Air University, he was the assistant director of research and innovation at Boise State University’s eCampus Center, where he led a team engaged in research and development related to innovations in online learning. Dr. Nyland has worked as a learning engineer, researcher, multimedia designer, and faculty member. He has presented at various military and education conferences and published articles about professional military education, learning analytics, online learning, and open educational resources in such publications as The Journal of Computing in Higher Education, International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, and TechTrends.

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3264-7039

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Air University, Marine Corps University, the U.S. Marine Corps, the Department of the Navy, or the U.S. government.