International Perspectives on Military Education

volume 2 | 2025

Online Mindfulness-Based Interventions

Korean Military Students’ Experiential Perspectives

Eunmi Kim, PhD; Leigh Ann Perry, PhD; Lisa Kerr, EdD; Kyusoon Pak; Sang Seong Kim; Hyeonjun Kim; and Kiwoong Park

https://doi.org/10.69977/IPME/2025.008

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) have been applied across various fields, notably in education. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the transition of their application to online formats. While this type of delivery may be especially valuable in military settings given their unique constraints, research in Korea has been limited. The current study describes the first online MBI offered as a semester-credit course for undergraduate students at a civilian public university who are taking online classes while serving in the Korean military and explores participant experiences with and outcomes of the MBI. During a 16 week period, 16 students viewed weekly videos and, during the final 10 weeks, completed meditation journals three times per week. The curriculum included body scan, relaxation, breath awareness, selective attention, self-compassion, and mindful daily living, delivered through guided meditations, recorded sessions, creative activities, and instructor feedback. Nine students gave consent to be participants in the study. A data-driven, thematic analysis of the nine students’ journals examined immediate post-meditation experiences, bodily sensations, breath awareness, and integration through journaling. Two primary themes emerged: personal process and outcomes experienced. The first theme highlights a common personal process through which students developed a meaningful relationship with their introduction to mindfulness practices, including subthemes of comfort level, normalization, and intent to continue. The second theme identified outcome subthemes related to physiological benefits, physical self-awareness, and mental self-awareness. Findings suggest online MBIs can support psychological and physical well-being in high-stress military environments. The study highlights the potential of such programs to promote resilience and health in these unique environments and the need for further research in military populations.

Keywords: mindfulness, mindfulness-based interventions, MBI, resilience, military wellness, military students, professional military education

Introduction[1]

South Korea maintains one of the few remaining conscription systems among modern democracies, mandating nearly all able-bodied men in their early 20s to serve in the military for approximately 18–21 months. Unlike voluntary service-based systems, the Korean military is composed largely of conscripts who are often university students temporarily suspended from civilian life and education. This context shapes a unique psychological landscape: young men at a formative age are abruptly immersed in a hierarchical, regimented environment characterized by limited autonomy, constrained communication with the outside world, and constant exposure to geopolitical tension. The latter is especially pronounced given South Korea’s proximity to North Korea and the ongoing state of armistice, rather than peace, between the two nations. These factors, compounded by cultural elements such as traditional Confucian hierarchies and the internalized social pressures of masculinity, result in a military experience marked by multifaceted psychological stressors.

Despite the high-stress nature of military service, psychological support within the Korean military has historically centered on reactive interventions, such as counseling following incidents or administrative referrals due to noticeable distress. While recent years have seen an increase in preventative efforts, including the assignment of accident prevention counselors and unit-level emotional management officers, comprehensive and proactive mental health strategies remain underutilized. One promising strategy is the application of mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs), which have been empirically shown to improve psychological symptoms, reduce anxiety, improve sleep quality, and improve overall well-being in civilian populations.[2] In educational settings, MBIs have been found to improve students’ self-regulation, persistence, stress levels, depression and anxiety, sleep quality, and resilience.[3] However, despite this growing evidence, the integration of MBIs into military life, particularly within South Korea, remains limited and underresearched.

Previous studies have shown that combined online and in-person MBI classes positively impact college undergraduate students’ (mean age 21.1 years, standard deviation 1.7 years) self-compassion and creativity, revealed neural correlates between mindfulness and creative cognition through electroencephalography (EEG) data, and qualitatively demonstrated that mindfulness interventions for undergraduate students in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education enhance learning experiences and emotional resilience.[4] Building on these foundations, the current study explores the potential benefits of MBIs within a high-performance academic environment.

The COVID-19 pandemic, while disruptive, offered an unexpected opportunity to reimagine the delivery of MBIs. With in-person gatherings restricted, the expansion of online mindfulness programs created new potential to reach populations previously inaccessible due to institutional or environmental barriers. In military settings, where interpersonal contact with civilians is tightly controlled, online MBIs emerged as a plausible and scalable solution. However, empirical research evaluating their implementation and outcomes in such environments remains virtually nonexistent in the Korean context. Addressing this gap, the present study implemented structured MBI sessions with undergraduate students at a university in Korea who were in the process of fulfilling their mandatory military service and were taking the online Korean-language mindfulness course during their service, applying validated methodologies from prior research to comprehensively evaluate their effects.[5]

K.W. Park et al. provide a strategic analysis and proposal for implementing MBIs within the Korean military.[6] They review the current state of mental health initiatives in the Republic of Korea (ROK) Armed Forces and examine MBI programs conducted in the United States and United Kingdom militaries. Through a SWOT (strength, weakness, opportunity, and threat) analysis tailored to the Korean military context, they identify appropriate strategic approaches for each category. As part of their recommendations, the authors propose an online MBI course, which serves as the model intervention implemented with students in the present study.

By situating the current study within the dual contexts of conscription-based military service and higher education, this research contributes to a growing body of literature exploring how mindfulness can function not just as a therapeutic tool, but as an educational and developmental resource in high-stress institutional settings. As the generational perception of military service shifts and traditional notions of stoicism give way to a more holistic understanding of health and performance, interventions like MBIs may become critical in supporting the psychological well-being of future conscripts. Further studies are warranted to examine the long-term impacts of such programs and to refine delivery methods suited for diverse military populations.

Methods

Participants

Participants for the current study were undergraduate students in the Korean military registered in an online MBI course at Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) in South Korea. Students participated in the course by viewing prerecorded video lectures outside of their official military service hours, including during evenings and on designated days off. Sixteen students enrolled in the course, and nine students provided informed consent to participate in the study.[7] All participants were male and, at the time of the MBI course, were serving their mandatory military service. Ages ranged from 21 to 23 years, with an average age of 22.1 years.

Intervention

The 16-week curriculum combined 28 short-form (20 minute) videos, 36 reflective journaling assignments, and structured meditation sessions across a variety of mindfulness themes: body scan, breath awareness, emotional identification, selective attention, and self-compassion. Weeks 8 and 16 were excluded due to exams. The entire course was conducted with asynchronous online videos. The first author served as the facilitator of the course and is a qualified Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT), and Mindful Self Compassion (MSC) teacher. Beginning with relaxation exercises, the curriculum covered selective attention and loving-kindness, training of sustaining and switching attention, and then clarification of individuals’ life purpose and true goals.[8]

Videos were designed to be engaging and contextually relevant, incorporating student-submitted stories with requested background music, instructor feedback, animated meditation guidance, and recordings of real-time offline sessions accompanied by five teaching assistants (TAs) who shared their experiential learning. Two of the TAs are coauthors on the current study. The course videos were designed by the facilitator, with TAs appearing alongside the facilitator to demonstrate meditation practices and share brief post-practice reflections. The TAs consisted of KAIST undergraduate and doctoral students, including one doctoral student currently serving in the military, and were intentionally selected to enhance participants’ sense of relatability and shared identity. This multifaceted approach was tailored to the lived realities of soldier-students: restricted schedules, physical fatigue, and the psychological dissonance of balancing academic identity with military obligations. One of the current study’s coauthors, an active-duty military officer who was also a doctoral student at the time of the course, served as a TA in course development and video production, helping to ensure the content reflected the real-life service context of the participants. They were intentionally selected as a TA appearing in the lecture videos to enhance participants’ sense of relatability and shared identity.

Each week, students were required to view the corresponding videos and submit three meditation diaries responding to four consistent reflection questions following each practice, with additional entries encouraged and factored into their course credit. During the semester, participants were encouraged to submit personal stories about their military experiences or messages for peers, which were then shared as individual video narratives. Participants also submitted a song, which was included in the closing segment of each edited video. Submitting a story and a song was considered a single assignment, completed once by each participant. After the semester concluded, participants were contacted via email to explain the intention to analyze their meditation journals for a qualitative research study. The course facilitator and the TAs communicated with the participants via email to obtain informed consent for the use of their meditation journals for research purposes.

A distinctive feature of this MBI is its emphasis on finding one’s own mission and vision. Conscripted college students commonly share a worry about their future after military discharge. During this period, the problem of how to lead one’s life gets more relevant as one gets temporarily separated from an ordinary academic track they have been following for more than a decade. Many feel worried about losing momentum and falling behind in this track of academic, professional development. Therefore, the last part of the curriculum was centered in countering anxiety, analyzing one’s internal traits and external environment, and finding paths for navigating one’s life by visualizing one’s true hope and mission during meditation.

Data Collection

The participants answered four questions after each meditation practice: Q1) How do you feel after meditation? Q2) What sensations do you feel in your body? Q3) Where and how do you feel your breathing? Q4) How do you feel now, after writing this report? All participants in this study voluntarily agreed to provide their meditation diaries for research purposes.

Data Analysis

As researchers, the authors recognize that their social, cultural, and professional identities influence how they designed, interpreted, and represented the findings of this study. The research team was made up of individuals with backgrounds in psychology, education, and military studies. Multiple authors have experience teaching or researching within military educational institutions, while others bring disciplinary training rooted in contemplative pedagogy. These varied backgrounds informed their sensitivity to the unique demands placed on Korean military students and shaped their commitment to presenting their experiences with accuracy, respect, and cultural humility.

The investigators who conducted the thematic analysis were not involved in the delivery of the course, the students’ academic evaluation, or the translation of the journals, which enabled a more independent analytic approach to the data. At the same time, the authors acknowledge that their experience in mindfulness-related research may have influenced the way they attended to certain experiential elements in participants’ reflections. To mitigate these influences, the investigators who conducted the analysis engaged in ongoing dialogue throughout coding, compared interpretations across investigators, and revisited the raw data repeatedly to ensure the final themes reflected participants’ words rather than the author’s expectations.

The present study used a data-driven, inductive thematic analysis approach to analyze the qualitative data collected in the participants’ journals and identify common elements related to participants’ entries. Victoria Clarke and Virginia Braun note that the aim of thematic analysis “is to identify, and interpret, key, but not necessarily all, features of the data, guided by the research question (but note that in TA, the research question is not fixed and can evolve throughout coding and theme development).”[9] Thematic analysis was chosen for this study because of its flexibility in enabling the researchers to take a data-driven approach that can also be informed by prior research and theory.

Prior to analysis, the participants’ journals were translated from Korean to English by one researcher. The analysis was then conducted by two investigators not involved in the data collection or translation phases of the research, following Braun and Clarke’s guidelines for thematic analysis.[10] First, they familiarized themselves with the data by reading the participants’ journal entries multiple times and noting their initial thoughts and ideas for coding.

Second, the investigators generated initial codes across the entire data set and gathered the relevant journal entry data for each emergent code. Third, the investigators collated the codes into possible themes and grouped relevant data into each theme. During this process, the investigators also identified potential subthemes. Fourth, the investigators reviewed the codes, subthemes, and themes, differentiating and merging them as needed to ensure they fit within a coherent thematic map. The investigators then reread all journal entries to ensure the themes accurately represented the data set and to identify and code anything that may have been missed in prior stages into the appropriate themes. Fifth, the investigators refined the themes by creating names and definitions for each. The theme refinement’s goal was to ensure the identified themes and subthemes were both internally homogeneous and externally heterogeneous. In the final phase of analysis, the investigators completed a final analysis of the themes and data within them as they related to the research question and current literature.

Results

Data analysis revealed two primary themes. The first theme highlights a common personal process through which students developed a meaningful relationship with their introduction to mindfulness practices. While the individual student journal entries articulated unique experiences, a clear pattern emerged in how students progressed toward appreciating mindfulness as a relevant practice for their wellbeing. Despite differences in the personal reflections, the students’ journeys followed a consistent trajectory.

The components of the overarching personal process are represented by three subthemes including level of comfort, normalization, and intent to continue. Initially, student responses focused on their perceived levels of physical and psychological comfort with mindfulness as a concept and with specific practice sessions. As their comfort level increased, students articulated a sense of normalization with an ability to move past the discomfort they experienced during the initial sessions of their mindfulness practice. Finally, toward the end of the course, the focus of the students’ reflections transitioned from physical and psychological factors of their individual sessions to expressing their appreciation for mindfulness relative to their wellbeing and their intent to maintain a mindfulness practice.

The second primary theme identified within the data relates to the outcomes experienced by the students as a result of engaging in the mindfulness practices. Two subthemes within the outcomes experienced include the participants’ self-identified physiological benefits as well as increased self-awareness (both physical and mental). The participants clearly and consistently articulated their perceptions of the outcomes they experienced that resulted from the introductory mindfulness practices.

Table 1 articulates the definition of the primary and secondary themes that surfaced from the study’s data analysis.

Table 1. Primary and secondary themes identified and defined

|

Theme

|

Subtheme

|

Definition

|

|

Personal process

|

|

The development of a personal relationship with the practice that follows a predictable pattern.

|

|

|

Level of comfort

|

Ease of psychological and physical engagement at any given point.

|

|

|

Normalization

|

Willingness of participants to adjust their responses to, and move past, their discomfort and the ambiguity within the practice.

|

|

|

Intent to continue

|

Indications by participants of their plan to practice mindfulness in the future.

|

|

Outcomes experienced

|

|

Recognition of a consequence of one’s mindfulness practice.

|

|

|

Physiological (e.g., improved sleep, body tension)

|

Participants’ physical experiences.

|

|

|

Self-awareness (physical and mental)

|

Participants’ mental acuity and emotion regulation; recognition and understanding of one’s thoughts, emotions, and physiological responses.

|

Source: courtesy of the authors.

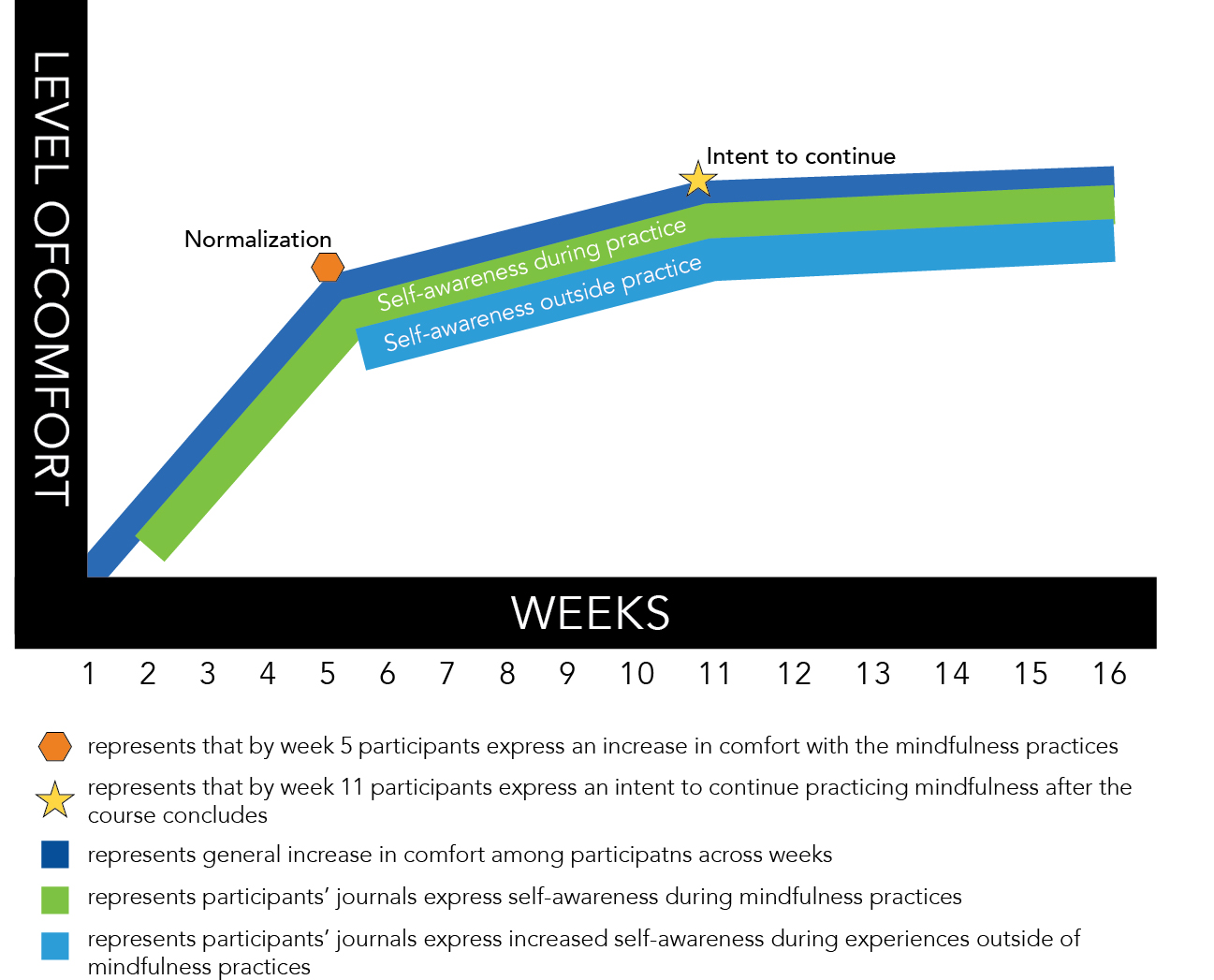

Personal Process

Beyond the specified personal experiences that the participants expressed in their journal entries, investigators identified a consistent pattern through which participants developed a personal relationship with the mindfulness practice instruction during the 16-week course. While each participant described their experience in their own words, focusing on different aspects of their introductory mindfulness practices, a consistent developmental process emerged when their reflections were viewed collectively. The graphic and process described in figure 1 illustrates a developmental pattern of how personal relationships with mindfulness practices may evolve.

Figure 1: Developmental pattern of relationship with mindfulness practices

Source: courtesy of the authors, adapted by MCUP.

Participants’ journal entries depict that they navigated through the individual components of developing a mindfulness practice through a predictable yet personalized process. Initially their reflections were surface level and expressed a lack of comfort, levels of discomfort, and sometimes resistance toward the practice. As the participants grew more accustomed to mindfulness practices, their reflections expressed a sense of normalization and acceptance for the physical, psychological, and emotional components of their experiences. Eventually, their journal entries reflected a notable shift in mindset, with many participants articulating explicit plans to continue engaging in mindfulness practices and a willingness to explore and expand their practice.

During the 16-week experience, the participants’ developmental arc moved from early discomfort—even occasionally disdain toward mindfulness as a daily activity—to a genuine interest in deepening their practice. While the degree of initial discomfort varied among the participants, the overall trajectory toward increased comfort was consistent. Early journal entries described feelings of distraction and discomfort, which gave way to contentment and, ultimately, a desire to integrate mindfulness more fully into daily life. By the final journal entries, participants demonstrated not only a heightened level of comfort but also a growing respect for mindfulness and its relevance in both personal and professional contexts.

Level of Comfort

The first subtheme that emerged under the process theme was level of comfort, which reflected the ease with which participants engaged in their weekly mindfulness practices. Participants described varying levels of both psychological and physical comfort, often expressing their desire for greater ease in their practice. Specifically, early journal entries frequently highlighted struggles with physical discomfort and difficulties maintaining focus. One participant shared, “I struggled to maintain focus, constantly adjusting my posture, sitting down, and stretching to alleviate muscle tension. Moving forward, I must practice meditation in a more conducive environment and remain consistent to improve my ability to concentrate in crowded situations.”

As the semester progressed, participants grew more comfortable with these challenges, demonstrating increased acceptance of discomfort as part of the mindfulness process. One participant shared, “Reflecting on my fourth week of meditation, I feel like I’ve grown slightly more at ease with my meditation routine compared to week three.” Similarly, other participants’ journal entries ranged from surface-level observations about physical discomfort and growing ease to deeper reflections on internal experiences, emotions, and sensations. One participant described a profound shift in their awareness, writing, “I felt serene and rejuvenated upon concluding my meditation session. There’s a lingering sense of vitality from the practice, as the heightened awareness of my existence infuses me with energy. This awareness instills a profound sense of confidence, as if I am in tune with something greater than myself.”

The above reflections illustrate a clear progression from initial discomfort to a more integrated sense of comfort, self-awareness, and confidence in their mindfulness practice.

Normalization

The subtheme of normalization emerged as participants became more willing to move past their initial discomfort and uncertainty with the practice. Over time, they adapted to the experience, demonstrating a shift from frustration to acceptance. One participant reflected on this transition, writing, “Compared to last week, the meditation felt less awkward and more natural . . . so I’ve been tense all day, but after the meditation, I felt relaxed and unwound.” The growing sense of ease was echoed by others who described a gradual shift away from frustration toward acceptance of integrating mindfulness into their lives. As one participant noted, “I feel like I’ve done a good job today, and that meditation is becoming a part of my daily routine.”

The participants’ reflections expressed a transition from initial hesitation to a more natural, accepted, and routine engagement with mindfulness practice.

Intent to Continue

The final subtheme that emerged within the developmental process was intent to continue. Many participants expressed a commitment to maintaining their mindfulness practice beyond the course. One participant reflected on their newfound appreciation for mindfulness by writing, “This was my first time meditating, and I had never really considered how I felt in my body before. However, now that I’ve done it and kept a journal, I find it interesting and enjoyable. I also feel like I’d like to do it every day in the future.”

This subtheme highlights not only participants’ intent to continue practicing but also their desire to explore new ways, places, and times to deepen their mindfulness experience. For some, journaling became an integral part of this process, serving as both a tool for reflection and a means of tracking progress. One student emphasized the value of journaling and reflecting as part of their practice, stating, “I believe the significant progress I’ve made in my meditation practice throughout the semester, albeit brief, is largely attributable to journaling. Keeping a record naturally provides self-feedback on areas for improvement, fostering personal growth. This habit, beneficial not only in meditation but also in understanding the world, has taught me a great deal, revealing valuable insights beyond the realm of meditation alone.”

For many participants, journaling extended beyond simple documentation; it became an essential component of their mindfulness practice, reinforcing their awareness and commitment to continued growth through routine mindfulness.

Outcomes

The second overarching theme that emerged from participants’ journal entries was outcomes. Throughout their reflections, participants recognized the effects of their mindfulness practice, noting various changes and benefits. These outcomes were categorized into two key subthemes: physiological outcomes and self-awareness outcomes.

Physiological

Physiological outcomes encompassed participants’ physical experiences during and after mindfulness practice. These included changes in sleep patterns, body tension, temperature, bodily sensations, and heart rate. Many participants reported positive physical effects, such as feeling more refreshed and energized. One participant reflected, “I gradually felt more awake and refreshed. After meditation, my mental fatigue, drowsiness, and physical fatigue from muscle aches and pains sensed much improved, and I felt more energized.” Similarly, another participant described a newfound sense of physical ease, writing that “after meditation, I sensed remarkably lighter. . . . My neck and back muscles also loosened, and my body movements became more relaxed and fluid.”

Not all physical experiences were immediately comfortable, but even those who encountered initial discomfort often reported positive effects afterward. One participant noted, “My tired eyes cleared up, my body felt warm, and discomfort in my legs and arms, which had bothered me during the meditation, lessened afterward.”

Throughout the semester, physiological responses fluctuated. Some participants initially experienced increased body tension but later reported a reduction in discomfort as they grew more familiar with mindfulness practice. These shifting experiences highlight the evolving physical impact of meditation as participants became more comfortable and attuned to their bodies.

Self-Awareness

Self-awareness Outcomes represent participants’ experiences with mental clarity, emotional regulation, and cognitive organization. Many of the participants’ journal entries highlighted their perception that mindfulness was beneficial in fostering a calm and relaxed mind. One participant reflected, “Before meditation, I felt weighted down by the tasks at hand, perceiving slow progress due to the pressure, which created a cycle of negative feedback. However, after meditating and clearing my mind, I was able to objectively evaluate the workload that had felt overwhelming. This enabled me to navigate through tasks with greater ease and efficiency.”

Others described how mindfulness helped them feel more prepared for the day, with one participant noting, “Through meditation, as I attempted to clear my mind, I found that my to-do list appeared less daunting, allowing me to approach my situation more objectively.”

Beyond mental clarity, participants also experienced increased energy, focus, and organization of thoughts. One individual explained, “I realized that meditation can help me feel more energized and productive during the lethargic days that often come with military life. I love my evening meditation at the end of the day, but I also feel strongly about starting my day with a morning meditation on the weekends to ensure that I have a more energized and meaningful day.”

Others described heightened concentration and mental refreshment, with one participant sharing, “I felt refreshed after the meditation. I didn’t actually feel cool; I just felt refreshed because my mind wasn’t cluttered. . . . I’ve often compared a clear mind to a tightly knotted thread, but it's a bit different. It’s a clear streak and horizontal.” Similarly, another participant noted, “It’s satisfying to have my thoughts organized, unlike before meditation. I believe meditation involves temporarily ceasing thought processes, and it’s remarkable that this alone can lead to clearer thinking. I think it’s because the stress associated with recognizing that I have many complicated thoughts is reduced, allowing me to think more clearly and generate new ideas.”

In addition to cognitive benefits, participants also reflected on how mindfulness practice enhanced their emotional processing and emotional intelligence. Several described increased emotional awareness and clarity, leading to more balanced decision-making. One participant shared, “Eventually, I was able to consider what would be best for me, leading to a more organized emotional state and a resolution to the situation with objectivity. It’s been a while since I’ve practiced meditation in such an emotionally charged situation, but I’ve discovered that even in circumstances where I anticipate difficulty focusing, meditation proves to be remarkably effective.”

Another participant described a deeper understanding of personal emotions and their connection to empathy, writing, “I think my lack of empathy for others stemmed from a lack of attention to my own feelings. Through meditation, I was able to focus on my past experiences, visualize those feelings again, and examine them from a distance. Future life is not always filled with happiness and comfort. It’s crucial to constantly be aware of my emotions and work through them. By being mindful of my own emotions and experiencing them, I can empathize with others better.”

As participants progressed through their meditation journey, many reported noticeable growth in their ability to regulate thoughts and emotions. Early entries often described challenges with managing negative emotions, as one participant noted, “I found it most challenging to experience the emotions without dwelling on their trigger or associated events, making it difficult to maintain focus. Similarly, observing my thoughts as they arose proved to be somewhat challenging during the mindfulness meditation of thoughts.”

However, later reflections demonstrated a shift toward greater acceptance and emotional balance. The same participant later wrote, “The most notable change from before I began meditating is my newfound ability to accept things as they are. Previously, whenever confronted with negative thoughts or emotions, I would attempt to transform them into something positive, often exacerbating my distress. Nevertheless, through the practice of simply observing things as they are, I’ve learned to acknowledge negative emotions without judgment, leading to better self-understanding and the cultivation of positive emotions. Following today’s meditation, I feel considerably more relaxed and composed in both body and mind.”

The reflections above illustrate the transformative impact of mindfulness on self-awareness, from increased mental clarity and emotional regulation to a deeper understanding of personal experiences and interpersonal empathy.

Discussion

The current study demonstrates that asynchronous, online mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) can be effectively implemented as a component of undergraduate coursework for students operating within the highly regulated and hierarchical structure of the Korean military. Despite the inherent limitations of this environment including rigid schedules, limited autonomy, and high levels of psychological stress, the participants showed a progressive internal engagement with the mindfulness practices over time. Their journal reflections captured a clear shift in experience: from initial skepticism and discomfort, to increasing familiarity, and ultimately to the emergence of intrinsic motivation to continue mindfulness independently.

The findings of the present study are consistent with and extend prior research conducted with Korean students on mindfulness meditation programs. Previous studies have demonstrated that regular mindfulness training positively influences students’ emotional stability, cognitive clarity, self-awareness, and creativity.[11] Building on these findings in educational contexts, the current study expands the application to university students fulfilling mandatory military service, implementing the intervention in an online format. The results empirically support that MBIs can provide physiological benefits and self-awareness even within highly constrained environments. This underscores the adaptability and efficacy of mindfulness programs across diverse populations, particularly in challenging settings such as the military, where access to such interventions is typically limited. Moreover, the present study reveals that comparable benefits can be experienced despite the substantially restrictive surroundings. By tailoring the program content to address the unique demands and psychological realities of conscripted student-soldiers, the intervention successfully provided a relevant and manageable entry point to contemplative practice.

One of the most significant outcomes of this study is the participants’ stated intent to continue practicing mindfulness after the course’s conclusion. This voluntary expression of sustained interest is not a trivial byproduct of participation, but rather a key indicator that the program fostered a meaningful sense of personal agency. Within military settings, where individuals typically have limited opportunities for autonomous decision-making, the development of self-directed psychological tools represents a substantial gain. Participants did not merely passively receive instruction; rather, they engaged with it critically, reflected on their own needs, and actively chose to carry the practice forward. In this sense, the intervention did more than relieve stress; it promoted a deeper sense of ownership over one’s internal state.

Furthermore, the program’s emphasis on journaling appears to have strengthened this process of internalization. Participants consistently described how journaling helped them notice patterns in their emotional responses, refine their self-understanding, and generate personal insights that extended beyond the formal scope of the course. In a context where emotional expression is often limited, the opportunity to reflect and write freely seemed to act as a powerful bridge between the practice and its long-term psychological relevance.

These outcomes are especially compelling when viewed in light of the broader cultural and institutional barriers to mindfulness adoption within military contexts. Military service is often framed as a time of endurance, discipline, and external conformity. In contrast, mindfulness invites attention to one’s inner landscape including thoughts, emotions, and bodily sensations, and encourages acceptance rather than suppression. The fact that participants not only accepted this contrast but grew to value and internalize it, suggests that contemplative education, when adapted appropriately, may have far-reaching applications even in settings traditionally resistant to introspective practices.

The implications of this research reach beyond short-term well-being. The development of mindfulness habits during military service may serve as a protective psychological buffer during transitions back to civilian life, especially for students reentering competitive academic or professional environments. The findings suggest a long-term potential for mindfulness to function as a stabilizing force, ultimately helping young adults navigate identity, purpose, and personal direction during and after service. Given that the latter portion of the curriculum focused on vision-setting and life planning, it is likely that participants’ insights were not merely therapeutic but also developmental, equipping them with tools for self-leadership and values-based decision-making.

The progression observed included transitions from resistance to routine and from discomfort to intentional continuation illustrating that the capacity for mindful awareness is not contingent on freedom of environment, but on the relevance, resonance, and quality of the invitation. Future research should explore the sustainability of these changes post-discharge and investigate how different delivery methods or support systems might further enhance long-term adherence and impact.

Limitations

The current study has limitations including generalizability, reliance on self-report measures, and lack of control group. The small sample size and the unique context of Korean military service limit the generalizability of the findings. In addition, the use of self-reported meditation journals may be influenced by participants’ motivation, recall accuracy, and social desirability bias. The absence of a control group precludes causal conclusions regarding the effects of the intervention. Future research should incorporate control groups, recruit larger and more diverse samples, compare different delivery methods, and conduct longitudinal assessments to examine the sustainability and long-term effects of mindfulness habits.

Conclusion

The current study reinforces the idea that mindfulness can be more than a coping mechanism, it can become a lifelong resource for psychological flexibility and self-regulation. When embedded within a structured, context-sensitive program, even individuals operating under significant external control can access and benefit from contemplative practice. The findings offer important implications for well-being initiatives within the Korean military and provide future directions for research across PME institutions globally who are interested in implementing similar programs. MBIs appear feasible despite the logistical and cultural constraints of the Korean military and may serve as a powerful tool to enhance psychological resilience in a population often overlooked in preventive mental health efforts. This suggests a latent potential for MBIs to become a normalized element of mental health programming in military environments, both in Korea and internationally. While this study focused specifically on undergraduate Korean military members, previous research has indicated benefits of mindfulness across American military forces and other high stress occupations that may have implications for transferability of the current study’s findings to broader military audiences.[12]

Furthermore, this study is significant as it is the first to implement an online semester-credit mindfulness course within the Korean military. Notably, when producing the videos used for the course, a current in-person course participant, who is also an active-duty soldier, participated in the video production, enhancing student engagement and immersion in the course. In addition, participants in the online course shared their personal stories and requested songs, which were incorporated into the final videos. Researchers designing the study intentionally incorporated student preferences into the videos when the students’ songs and stories did not detract from the MBI structure. The researchers purposefully incorporated students’ shared content into the recordings with the intent to broaden the sense of empathy and connection between the mindfulness instructor and the students. Although real-time feedback was not possible, these participatory elements were designed to play a key role in enhancing student engagement and enriching their overall program experience.

Endnotes

[1] The authors have no relevant financial or nonfinancial interests to disclose. No funding was received for conducting this study. Due to the nature of the participants of this study as active military personnel, the data are unavailable for public review. Participant responses are provided by permission.

[2] Simon B. Goldberg et al., “Efficacy and Acceptability of Mindfulness-based Interventions for Military Veterans: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis,” Journal of Psychosomatic Research 138 (November 2020): 110232, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110232; Hailiang Zhang et al., “Mindfulness-based Intervention for Hypertension Patients with Depression and/or Anxiety in the Community: A Randomized Controlled Trial,” Trials 25, no. 1 (May 2024): 299, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-024-08139-0; Ascensión Fumero et al., “The Effectiveness of Mindfulness-based Interventions on Anxiety Disorders: A Systematic Meta-review,” European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology, and Education 10, no. 3 (July 2020): 704–19, https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe10030052; Elizabeth A. Hoge et al., “Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction vs Escitalopram for the Treatment of Adults with Anxiety Disorders: A Randomized Clinical Trial,” JAMA Psychiatry 80, no. 1 (2023): 13–21, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.3679; Xinyi Zuo et al., “The Efficacy of Mindfulness-based Interventions on Mental Health among University Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis,” Frontiers in Public Health 11 (November 2023): 1259250, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1259250; Ana María González-Martín et al., “Effects of Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy on Older Adults with Sleep Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis,” Frontiers in Public Health 11 (December 2023): 1242868, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1242868; and Flavia Marino et al., “Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Physical and Psychological Wellbeing in Cardiovascular Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Brain Sciences 11, no. 6 (May 2021): 727, https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11060727.

[3] Lijuan Fan and Feng Cui, “Mindfulness, Self-efficacy, and Self-regulation as Predictors of Psychological Well-being in EFL Learners,” Frontiers in Psychology 15 (March 2024): 1332002, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1332002; Daniel R. Evans, Ruth A. Baer, and Suzanne C. Segerstrom, “The Effects of Mindfulness and Self-consciousness on Persistence.,” Personality and Individual Differences 47, no. 4 (September 2009): 379–82, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.03.026; Ana María González-Martín et al., “Mindfulness to Improve the Mental Health of University Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis,” Frontiers in Public Health 11 (December 2023): 1284632, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1284632; Zuo et al., “The Efficacy of Mindfulness-based Interventions on Mental Health Among University Students,” 1259250; Jennifer N. Baumgartner and Tamera R. Schneider, “A Randomized Controlled Trial of Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction on Academic Resilience and Performance in College Students.” Journal of American College Health 71, no. 6 (August–September 2023): 1916–25, https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2021.1950728; Julieta Galante et al., “Effectiveness of Providing University Students with a Mindfulness-based Intervention to Increase Resilience to Stress: 1-year Follow-up of a Pragmatic Randomised Controlled Trial,” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 75, no. 2 (February 2021): 151–60, http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jech-2020-214390; and Luisa Charlotte Lampe and Brigitte Müller-Hilke, “Mindfulness-based Intervention Helps Preclinical Medical Students to Contain Stress, Maintain Mindfulness and Improve Academic Success,” BMC Medical Education 21, no. 1 (March 2021): 145, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02578-y.

[4] Young Min Jung and Eunmi Kim, “A Comparison of Online and In-person MBI Classes on Self-compassion and Creativity,” in David Guralnick, Michael A. Auer, and Antonella Poce, eds., Creative Approaches to Technology-Enhanced Learning for the Workplace and Higher Education: Proceedings in “The Learning Ideas Conference” (Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2023), 247–62, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-41637-8_20; Sang Seong Kim, Sunhwa Hwang, and Eunmi Kim, “Neural Correlates of Creative Drawing: Relationship Between EEG Output and a Domain-specific Creativity Scale,” in David Guralnick, Michael A. Auer, and Antonella Poce, eds., Innovative Approaches to Technology-Enhanced Learning for the Workplace and Higher Education: Proceedings of “The Learning Ideas Conference” (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2022), 172–80, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-21569-8_16; and Eunmi Kim et al., “Mindfulness Intervention Courses in STEM Education: A Qualitative Assessment,” in David Guralnick, Michael A. Auer, and Antonella Poce, eds., Innovations in Learning and Technology for the Workplace and Higher Education: The Learning Ideas Conference (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2021), 160–69, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-90677-1_16.

[5] Jung and Kim, “A Comparison of Online and In-person MBI Classes on Self-compassion and Creativity”; Kim, Hwang, and Kim, “Neural Correlates of Creative Drawing”; and Kim et al., “Mindfulness Intervention Courses in STEM Education.”

[6] K. W. Park et al., “A Mindfulness Approach to Enhancing the Mental Health of Military Personnel: Strategic Proposals Tailored to the Specificities of the Republic of Korea Army,” Korean Journal of Advances in Military Studies 81, no. 1 (2025), https://doi.org/10.31066/kjmas.2025.81.1.008.

[7] The current study was conducted with the approval of the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology’s (KAIST’s) Institutional Review Board (IRB) (approval number: KH2024-071) and has therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

[8] Selective attention exercises refer to practices that train the ability to focus on a specific stimulus while filtering out irrelevant stimuli. Loving-kindness exercises refer to practices where participants silently repeat positive phrases toward themselves and others (e.g., “May I be happy, may I be safe” and “May you be happy, may you be safe”) to cultivate compassion and connection.

[9] Victoria Clarke and Virginia Braun, “Thematic Analysis,” Journal of Positive Psychology 12, no. 3 (2017): 297–98, https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613.

[10] Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke, “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology,” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3, no. 2 (2006): 77–101, https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

[11] Jung and Kim, “A Comparison of Online and In-person MBI Classes on Self-compassion and Creativity”; Kim, Hwang, and Kim, “Neural Correlates of Creative Drawing”; and Kim et al., “Mindfulness Intervention Courses in STEM Education.”

[12] Kelly R. M. Ihme and Peggy Sundstrom, “The Mindful Shield: The Effects of Mindfulness Training on Resilience and Leadership in Military Leaders,” Perspectives in Psychiatric Care 57, no. 2 (August 2021): 675–88, https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12594; Amishi P. Jha, Mary K. Izaguirre, and Amy B. Adler, “Mindfulness Training in Military Settings: Emerging Evidence and Best-Practice Guidance,” Current Psychiatry Reports 27, no. 6 (June 2025): 393 –407, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-025-01608-6; and Amishi P. Jha et al., “The Effects of Mindfulness Training on Working Memory Performance in High-Demand Cohorts: A Multi-Study Investigation,” Journal of Cognitive Enhancement 6, no. 2 (2022): 192–204, https://doi.org/10.1007/s41465-021-00228-1.

About the Authors

Dr. Eunmi Kim is a visiting research fellow at Cambridge Health Alliance (CHA), affiliated with Harvard Medical School. Her research focuses on mindfulness, integrative mind–body interventions, and the neurophysiological mechanisms underlying resilience and emotion regulation. She previously served as a research associate professor at the Center for Contemplative Science at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST), where she led large-scale studies on meditative states and stress-related processes. Dr. Kim completed postdoctoral fellowships at Brown University and CHA and holds a PhD in integrative mind–body healing from the Seoul University of Buddhism. Her interdisciplinary work spans clinical neuroscience, contemplative science, and mental health.

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1888-1059

Dr. Leigh Ann Perry is an associate professor of psychology and behavioral science in the College of Leadership and Ethics at the U.S. Naval War College (USNWC) in Newport, RI, focusing on resilience, holistic wellness, and leader development. She founded and directs the Cognitive Fitness and Mindful Resilience Initiative at the USNWC to provide education and resources for utilizing mindfulness as a tool for cognitive fitness, resilience, and performance optimization within the Department of the Navy. Prior to joining the USNWC and focusing her work on positive psychology and leader development, Dr. Perry worked for the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit, Naval Criminal Investigative Service, and Facebook’s Global Security team focusing on the analysis of violent criminals, terrorists, and dangerous organizations. She holds a PhD and an MA from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, in clinical and community psychology and a BS in psychology and sociology from Fordham University. She also studied psychology and sociology at Oxford University.

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3330-3118

Dr. Lisa Marie Kerr is an associate professor in the College of Leadership and Ethics at the USNWC, where she contributes to curriculum development and assessment and facilitates executive leader development for the U.S. Navy. Her current research agenda focuses on learning effectiveness for leader development in professional military education settings, human factors in systems thinking and holistic wellness for optimal performance and warfighter readiness. Kerr is a career educator dedicated to supporting and challenging leaders through development that enhances their capacities to address more dynamic, complex, and ambiguous problems.

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3330-3118

Kyusoon Pak is a major in the Republic of Korea Army and a doctoral candidate at KAIST. His research focuses on developing technologies that can enhance soldier survivability on the battlefield. To achieve this goal, he pursues interdisciplinary studies that integrate various engineering disciplines with mindfulness-based approaches, aiming to create innovative solutions for combat medical care and warfighter protection. https://orcid.org/0009-0008-1275-9045

Sang Seong Kim received a bachelor’s degree at KAIST. His research interests consist of psychological domains such as mental well-being, attention, mindfulness, spirituality, and existentialism. He pursues phenomenological studies combined with neurophysiological measures and numerical modeling methods.

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2995-1216

Captain Hyeonjun Kim is a permanent faculty member in the Department of Systems Engineering at the Korea Military Academy in Seoul, Republic of Korea. His research focuses on multiagent systems, artificial intelligence applications in defense, and human-AI interaction in military contexts. As both a military officer and educator, Captain Kim is engaged in research on military organizational effectiveness and approaches to enhancing operational resilience.

https://orcid.org/0009-0005-4337-1455

Kiwoong Park is a major in the Republic of Korea Army and a PhD candidate in the User & Information Lab at the KAIST School of Computing. His research focuses on AI, large language models, and their intersection with culture and low-resource languages. He is also interested in mindfulness and interventions relevant to the military context.

https://orcid.org/0009-0007-8873-8243

Acknowledgments

The researchers would like to express their sincere gratitude to the students who participated in the online mindfulness course during the Fall 2023 semester. They are especially thankful to those who diligently kept their meditation journals while serving in the military and consented to participate in this study. Special thanks also go to the teaching assistants—SH Park, YR Shin, SC Lee, DH Cho, HW Yang, CM Lim, SG Yoon, and YM Jung—who contributed to the planning and filming of the online video sessions. We are also grateful to the KAIST Education Strategic Planning Team for their financial support in producing the video content tailored to military student participants.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the U.S. Naval War College, Marine Corps University, the U.S. Marine Corps, the Department of the Navy, or the U.S. government.