International Perspectives on Military Education

volume 2 | 2025

Identifying Moral Perspective Preferences in National Security Professionals

Pauline Shanks Kaurin, PhD; Captain George Baker, USN (Ret), EdD; and Leigh Ann Perry, PhD

https://doi.org/10.69977/IPME/2025.004

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: Professional military education (PME) traditionally emphasizes decision-making frameworks for leader development, including cognitive models and moral perspectives such as virtue ethics, deontology, and utilitarianism. This study introduces and examines the moral perspective sorter (MPS), a 12-item teaching tool developed at the U.S. Naval War College (NWC) to assess students’ moral perspective preferences, including the often-overlooked ethics of care. Data from five years of application in intermediate and senior-level PME, including the NWC and Navy Senior Enlisted Academy (SEA), indicate that ethics of care consistently emerges as the most frequently selected perspective in aggregated groups exceeding 100 participants. Findings suggest that PME curricula should incorporate ethics of care to better align ethical education with the disposition of current national security professionals. Implications for pedagogy, small-group facilitation, and faculty development are discussed.

Keywords: ethics education, moral preferences, moral perspective sorter, MSP, national security professionals, professional military education, PME, leader development

Introduction

Professional military education (PME) focuses a great deal of attention on decision-making, including examination of different models for decision-making, Daniel Kahneman’s System 1 and System 2 thinking, cognitive biases, and the role of assumptions and heuristics in reflection and other cognitive activities.[1] To address good decision-making, which ought to include proper ethical content, PME institutions also often teach some form of moral deliberation—how to choose right from wrong. Most rely on the three dominant moral perspectives: virtue, deontology, and utilitarianism.[2]

This article addresses ethics education in two contexts: the U.S. Naval War College (NWC) and the Senior Enlisted Academy (SEA). The NWC provides professional military education designed to prepare students for the operational and strategic levels of military and civilian engagement in the national security enterprise. The SEA provides professional development designed for senior enlisted leaders (E-7 through E-9). Ethics education at these institutions aims to develop self-awareness and capacities for ethical leadership including moral deliberation, reflection, and engaging across moral differences. To do so, the NWC and the SEA teach four major moral perspectives from philosophy: virtue, deontology, utilitarianism, and ethics of care.[3] For clarity and ease of discussion, deontology and utilitarianism are referred to as duty and consequentialist, respectively, for NWC and SEA students throughout the remainder of this article. Together, these approaches serve as four different lenses through which to judge the right and wrong actions in a given situation, adding ethics of care to the three more frequently utilized moral perspectives.

Why Add Ethics of Care?

Virtue, duty, and consequentialist perspectives have long been at the center stage for determining which action to take through moral deliberation. However, these dominant moral theories assume independent, autonomous, and rational individuals. They purposefully ignore the fact that people naturally form personal and social relationships.[4] From the dominant moral theories perspective, relationships are thought to create favoritism that conflicts with impartiality.[5] Yet, as human beings, relationships do indeed matter. Hence, the more recently developed moral perspective, ethics of care, recognizes that humans are relational and emotional.[6] Ethics of care recognizes that social bonds and cooperation are as important as the individual desires of equality and freedom.[7] There are many reasons why soldiers fight in war. One of those reasons, often said, is that they are fighting for each other. The relationships they form throughout their training are often what matters most in the heat of combat. Ethics of care accounts for these elements not included in the dominant moral perspectives.

For readers unfamiliar with moral philosophy, morals are right/wrong or good/bad judgments. Each of the four major moral philosophies makes these judgments from a different standpoint. Dating back to circa 300 BCE, virtue ethics focuses on the individual’s character as a collection of virtues (virtu in Greek = excellence).[8] These traits or behaviors are necessary for the good life. Virtues (e.g., honor, courage, and commitment) are habitually and consistently demonstrated by individuals in their actions as judged by others in a social context or community. As members of the Joint Force, the social context and community is the profession of arms. Being in this profession carries moral obligations to the society they serve (professional ethics) and the embodiment of a professional identity (professional ethos).[9] All Service core values are rooted in virtue ethics.

During the Age of Enlightenment (late eighteenth century), a new concept of moral reasoning emerged—duty ethics. Duty ethics focuses on principles. More often referred to as Immanuel Kant’s deontology, the right thing to do is derived from rational reasoning based on the following principles of consistency (what everyone should do) and respect (treating people as ends rather than means).[10] Acting for the sake of duty is moral because of the need for consistent good will (good action). This is opposed to merely acting in accordance with duty, which includes other motivations that might confuse the moral deliberation process and not lead to moral action.

A century later, social changes in the Victorian era sparked debates about greater social issues. From those debates, consequentialist ethics emerged. Whereas duty ethics centers on intent, consequentialist ethics centers on outcomes and the greater good.[11] Here, moral actions (act utilitarianism) or moral rules (rule utilitarianism) are rooted in and justified by the consequences. Actions or rules are moral to the degree they produce the greatest good, happiness or pleasure, for the greatest number of people. This means, for something to be moral, it must have good consequences in the aggregate—nothing more, nothing less.

Virtue, duty, and consequentialist ethics make up what is often referred to as the dominant three moral perspectives.[12] They center on the “public” life principles of reason, law, and justice. In this arena, individuals are assumed to be equal, rational, and independent agents.[13] Said differently, human beings are universal—one size fits all. These collective assumptions dominated moral discourse until the late twentieth century. Emerging in the 1980s, ethics of care challenged the assumptions behind the dominant moral perspectives. Instead of autonomous, independent agents, ethics of care recognizes that people are social creatures with inherent power differences.[14]

Ethics of care centers on relationships, empathy, and proper reflective moral emotions. Ethics of care argues that morality is relational. We need to think about care, not just as raw feeling, but as a practice of moral responsibility based on our relationships. Relationships, empathy, and moral reflective emotions (e.g., appropriate sensitivity and responsiveness) discern moral actions in each context. Furthermore, ethics of care also requires attention to the power dynamics and elements of the context to discern and enact moral responsibilities. Unlike the three dominant moral perspectives, judgments through ethics of care cannot be made in advance or in the abstract, and judgments of right and wrong are rooted in both moral emotion and reflective rationality.

Students at the NWC are exposed to these different moral perspectives in their core course, Leadership in the Profession of Arms (LPA). During this introduction, they often want to know why it is necessary to look at a moral situation from different perspectives. To clarify this for students, LPA instructors use a four-way intersection analogy that seems to resonate with those who might be skeptical about doing more work, especially when they already “know” the right answer. Imagine a small town that has a four-way intersection notorious for traffic accidents (one or two each week). Now, imagine that the town has hired you to be the traffic accident adjudicator. When the next accident occurs, your job will be to decide who is at fault. And to help you, someone installed a traffic camera on the north side of the intersection. Would you want access to that traffic camera? Yes. Oh, and there are cameras on the south, east, and west sides of the intersection as well. Which camera or cameras would you routinely want access to? All four. Why all four? Each one shows a different perspective. At that point, students can make the connection to the importance of viewing moral situations through different perspectives.

Another method used by the instructors to help students with this exploration is to provide them the opportunity to practice moral deliberation in different scenarios from each of the four major moral perspectives. What would this deliberation look like from a virtue ethics perspective? What would it look like from a duty ethics perspective? This is a critical learning point where students often need to be guided by a knowledgeable teacher. It is not uncommon for students to get it wrong when they try explaining something from a nonpreferred perspective. By applying the four perspectives in a scenario, students begin to appreciate the value of thinking past their initial thought. They also understand that views other than their own are equally justifiable when examined through a different moral lens. They recognize that this is often the case when people are talking past each other on moral issues. Further, knowing the four perspectives gives students the tools to appreciate the other person’s perspective when they are in general disagreement.

Students continue to use these terms throughout the entirety of the LPA course in personal conversations, classroom discussions, and written reflection assignments. The four moral perspectives serve as a cornerstone in later lessons focusing on heuristics, cognitive biases, and decision-making. Students are encouraged to make the connection between System 1 thinking (intuitive/automatic) and their preferred moral perspective and identify that they may need to shift into System 2 thinking (deliberate) to access and consider those moral perspectives that may not be their default lens.[15]

Research involving the dominant moral perspectives (virtue, duty, and consequentialist) is well established. For example, these perspectives form the basis of Lawrence Kohlberg’s studies on moral reasoning.[16] However, research that includes ethics of care is parsed. What is unknown is how prevalent the ethics of care perspective is in national security practitioners’ moral deliberation. Given that most PME institutions do not include ethics of care in their curricula, is the larger body of PME missing out on an important aspect of moral reasoning in military decision-making?

Developing the Moral Perspective Sorter

To teach moral reasoning, the authors initially used free online tools such as the Ethical Philosophy Selector and the Ethical Lens Inventory. However, these resources proved problematic. Besides being heavily ladened with advertisements, their results pointed to individual philosophers (e.g., St. Augustine of Hippo, Jean-Paul Sartre, Aristotle, John Stuart Mill, etc.) vice the broader moral theories (virtue, duty, consequentialist, and ethics of care). Students were losing sight of the forest through the trees. Accordingly, the first and second authors developed a survey of their own.

The moral perspective sorter (MPS) is a pre-class, online quiz designed to help students identify their preferred lenses for moral reasoning. It is a teaching tool to help students invest in thinking about moral questions and facilitate classroom conversations on ethics. It is a 12-item, multiple-choice questionnaire distributed via the NWC’s online survey software. Each question offers four response options, and each response aligns with one of the four moral perspectives: virtue, duty, consequentialist, or ethics of care. The survey results are downloaded into an Excel spreadsheet, which is then used to mail merge students with their individual results.

These individual results give students an awareness about how they view moral questions via the four moral perspectives. The learning continues in the classroom when students see how others approached moral questions during discussions and in applications with cases, scenarios, and moral narratives. It is important to have a common language around concepts, so tools like this have been common devices in undergraduate philosophy and ethics courses (different versions can be found online), but none focus solely on these foundational moral perspectives.

Focusing on the four moral perspectives serves as a bridge to a deeper understanding of philosophy. With a firm understanding of virtue, duty, consequentialist, and ethics of care, students can then appreciate the differences between David Hume, Immanuel Kant, Jeremy Bentham, and the host of other philosophers who have contributed to moral reasoning throughout time. That was the goal of the MPS. But by using it, the MPS pointed out something unexpected, something the authors were not looking for. When, out of curiosity, they added the results in the four columns of the spreadsheet (virtue, duty, consequentialist, and ethics of care), there was one clear standout.

Using the Moral Perspective Sorter

The MPS was used to examine the perspectives across NWC and SEA students to determine if ethics of care was a preferred moral perspective when considered alongside the three historically dominant perspectives. Was ethics of care even worth teaching? The answer was a resounding yes. The findings across individuals and multiple groups suggest that ethics of care is a preferred moral perspective for PME students and should be taught alongside the three more often taught perspectives. These findings provide an opportunity to examine expanded ways of teaching moral deliberation in PME and the need to address the absence of ethics of care as a major moral perspective.

The authors are current and former faculty members in the College of Leadership and Ethics at the NWC, with extensive experience teaching ethics and leader development to military and national security professionals. Their roles include curriculum design, faculty development, and facilitation of PME seminars. This positionality informs both the interpretation of results and the emphasis on practical applicability in PME settings.

Methodology

Study Design

The current study used a descriptive, cross-sectional approach, gathering MPS results from multiple seminars of PME courses at the NWC and SEA during a five-year period. This project was reviewed by the Naval Postgraduate School Institutional Review Board and determined to be exempt as the study does not meet the federal definition of “research” as defined under Title 32 Code of Federal Regulations § 219.

Participants

Participants included intermediate and senior-level officers from across the Joint Force, senior enlisted leaders, U.S. national security civilians, and international military partners who were students in either the LPA course at the NWC (about 400 per year) or at the SEA (11 classes per year, about 1,200 students total) from 2020 through 2025. For academic year 23–24 (AY 23–24), a total of 414 participants from the NWC (n = 230 intermediate officers; n = 184 senior officers) and 238 participants from two SEA classes during the same year (n = 105 in class 265; n = 133 class 268).

Procedure

The MPS was administered as a pre-lesson activity in the “Introduction to Moral Perspectives” session (a lesson at both the NWC and the SEA). Students receive an email invitation to complete the survey prior to class via a link embedded in the email. The survey results are downloaded to a spreadsheet and, using mail merge, students receive their individual results prior to the session, encouraging reflection before formal instruction. Though all have had ethics and compliance training (how to do) throughout their careers, few have had ethics education (how to think). Fewer still remember what specific philosophical terms (e.g., duty ethics, virtue ethics) mean even if they might have encountered them in a philosophy course as undergraduates.

Data Analysis

Once completed, the pre-lesson survey results are downloaded to an Excel spreadsheet. Individual results are scored by counting the number of responses the participants chose in the 12 multiple-choice questions in each of the four moral perspectives. For example, if a participant selected the response that aligned with duty ethics in 4 of the 12 questions, they would receive a score of 4 for duty ethics.

After mail merging students their individual results, Excel functions are used to produce graphs for individuals in each seminar. Additionally, Excel summation functions are used to aggregate individual results across the four columns (virtue, duty, consequentialist, and ethics of care) by class (for the SEA), or by class and by small group seminar (for the NWC). Individual and small group examples are shown in the section that follows.

Results

Individual Level

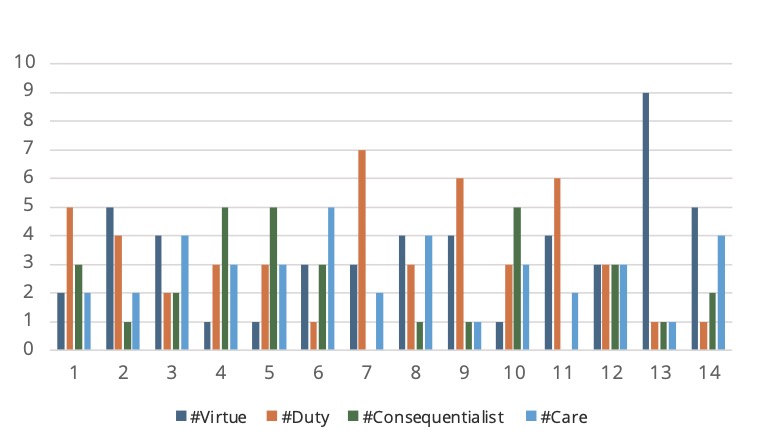

Participants varied widely in their moral perspective preferences, though most displayed a clear preference for one or two perspectives. Figure 1 represents MPS findings from one NWC seminar with 14 students.

Figure 1. Example of individual-level results

Source: courtesy of the authors, adapted by MCUP.

Small-group Level

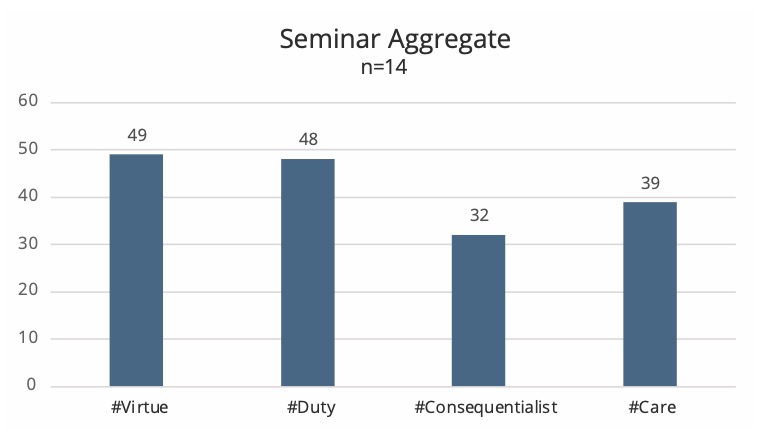

Unlike the individual-level graphs, seminar-level results revealed distinct patterns. Some seminars skewed toward virtue and duty preferences and others toward ethics of care and consequentialist preferences. Figure 2 displays the small-group level findings of the same seminar represented in figure 1, demonstrating a stronger preference for virtue and duty ethics compared to consequentialist and ethics of care.

Figure 2. Example of seminar-level results

Source: courtesy of the authors, adapted by MCUP.

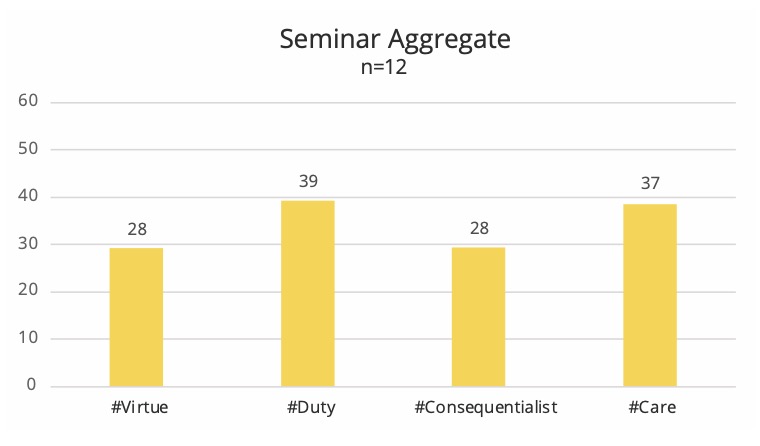

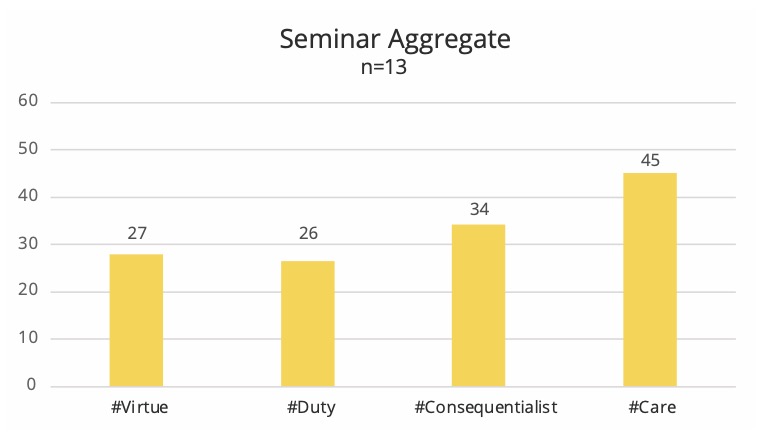

Despite the student composition across seminars being generally the same in terms of military service and civilian representation, the current study found differences across MPS profiles when comparing seminars. Figure 3 shows an example of these differences.

Figure 3. Example of seminar-level results comparison

Source: courtesy of the authors, adapted by MCUP.

Large-group Level

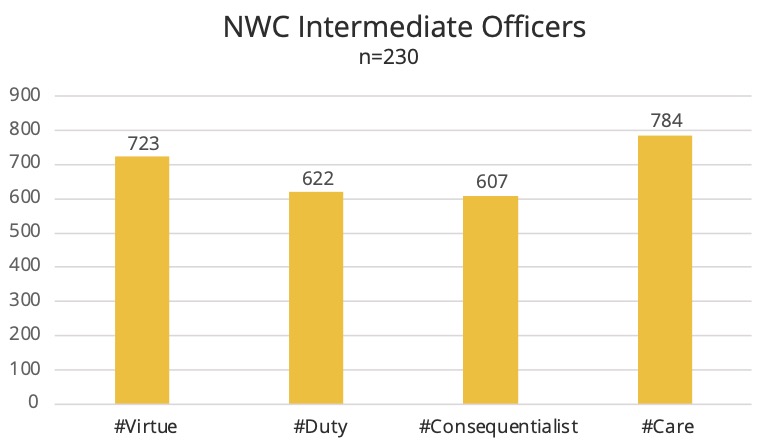

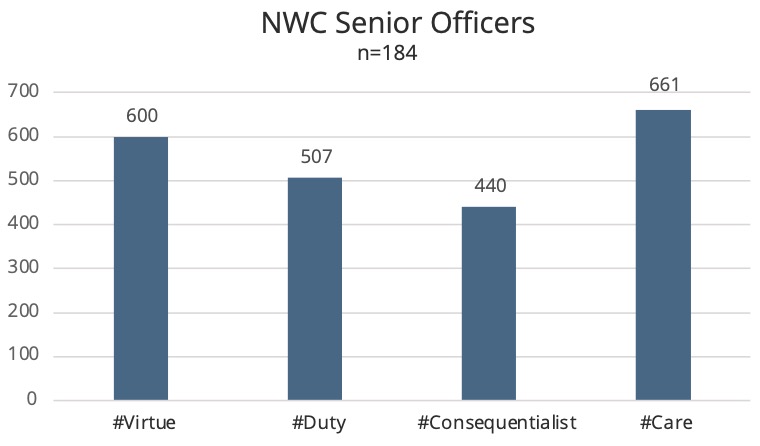

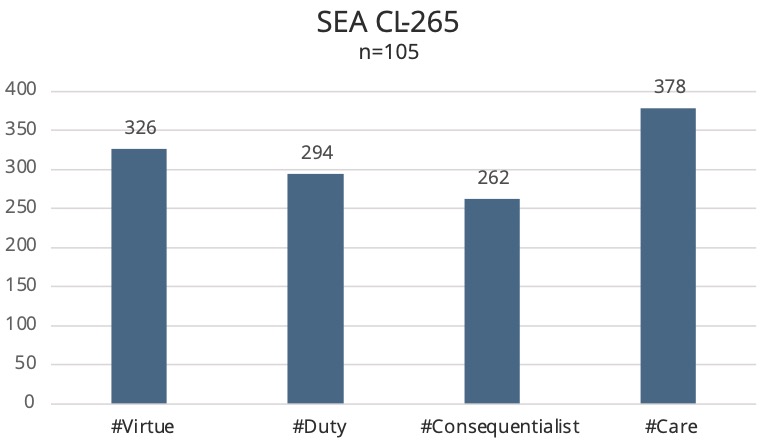

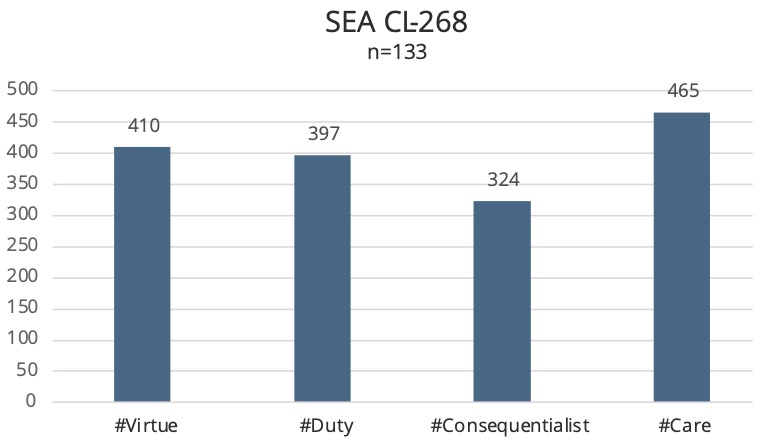

When seminar results were combined to create larger group cohorts (NWC intermediate officers, NWC senior officers, SEA class 265, and SEA class 268) with more than 100 participants per cohort, a consistent “smile” pattern emerged across all cohorts: virtue and ethics of care scores were higher, with duty and consequentialist scores lower. Across all large-group cohorts, ethics of care was the perspective with the highest level of responses.

Although the small-group level results varied across seminars, significant change happens at the large-group level. As seminars are combined into their larger cohorts and the sample size increases above n = 100, the pattern becomes surprisingly consistent across intermediate officer, senior officer, and senior enlisted ranks. Figures 4 and 5 show the aggregate MPS results for intermediate and senior officers attending the NWC during AY 23–24 and the senior enlisted members attending SEA during the same timeframe.

Figure 4. NWC AY 23–24 large group results

Source: courtesy of the authors, adapted by MCUP.

Figure 5. SEA AY 23–24 large group results

Source: courtesy of the authors, adapted by MCUP.

Discussion

The four moral perspectives provide a framework for deciding right or wrong when exploring the complexity of moral deliberation in today’s complex national security environment. For many, moral deliberation is implicit and difficult to express. They can articulate the right thing to do, but they often lack the words to explain why they think that choice is right, or how they arrived at that judgement. Using the MPS as a teaching tool makes this implicit reasoning explicit. Through familiarization with the tool, students have words to describe the “why” behind their choices.

More importantly, the MPS helps students explore reasoning and decision-making from their nonpreferred moral perspectives. The MPS shows students that theirs is not the only legitimate perspective in moral situations. It allows them to engage with other classmates in activities where ethical disagreement and articulation happen in face-to-face decision-making exercises. Students can see the difference between the moral perspective preferences play out in terms of what each person focuses on, sees or fails to see, or prioritizes as morally salient.

As one might expect, individuals vary in their preferences on the MPS. Some prefer one or two moral perspectives, while others can be evenly distributed across all four perspectives. An assumption behind the tool is that students are generally unfamiliar with recognizing each of the four perspectives. Hence, their affinity for one or two perspectives may provide some value for self-awareness. Though not always, this is often the case for students attending the NWC or the SEA.

During seminar discussions, students are asked to reflect (individually and with their seminar members) on where they think their results come from, and how their preference manifested in their past decisions. Then, the real work begins as students are challenged to look through their nonpreferred moral perspective lens. How might a different moral perspective view a specific event? Why? What elements might a different perspective focus on or see? The goal is for students to be able to view any event from all four moral perspectives, articulate the differences and similarities in morally salient aspects, and do so from each of the four perspectives.

PME institutions often break students into small groups or seminars for effectiveness of learning. The MPS results at the seminar level provide a kind of fingerprint for a different approach to building and using these small groups effectively. Results from the current study varied across seminars. Although research has yet to be conducted to determine what might account for these variations, small group MPS profiles may one day help professors manage small groups and teams to maximize learning. For example, how does approaching a group that scores high on ethics of care differ from a group that scores high on duty ethics? Especially in a seminar’s early stages, approaching a group from its dominant moral perspective may prove more fruitful than a standard, one-size-fits-all approach.

From a teaching perspective, moral preferences can also be used to break students into smaller groups within each seminar in decision-making exercises. Facilitators can use the MPS small-group profiles from a given seminar to structure in-class exercises—either grouping similar perspectives to deepen understanding or mixing perspectives to foster cross-perspective engagement. When grouped in “like” preferences, students listen to each other’s reasoning, begin to see their preferred moral framework in action, and start to pay attention to arguments from that perspective. Furthermore, forming groups that represent different combinations of moral perspectives helps students develop skills at engaging across moral differences. When used as a tool to form small groups of four to six students for in class exercises, the MPS can provide useful intergroup information. Beyond that, it may also hold some intragroup value, such as group activities with members of the same Service, area of specialization (e.g., aviators) across Services, or likely future roles (command, policy, or staff work).

The data from the current study support something the authors observed during the previous years of using the MPS as a teaching tool. While not something originally anticipated in the early days of using the MPS, ethics of care emerged as the preferred lens for students at the NWC and SEA when examined at large-group levels. This was surprising and unexpected when considering that ethics of care is largely left out of the curriculum at other PME institutions.

When MPS preferences were examined at a large group level, a distinct pattern was seen—the “smile” pattern. It is higher on the ends than in the middle, with ethics of care and virtue being the highest, and duty and consequentialism being lower. At the large-group level, this pattern has been consistent during the five years the MPS was used as a teaching tool. In the current study, ethics of care was the preferred perspective in all four of the large group cohorts measured. This result has important implications for PME. National security practitioners, especially those in the military, serve the public. Their expertise includes the management of violence to maintain public safety. To function, the profession of arms must maintain the public’s trust. Hence, ethical behavior is paramount. If national security practitioners use ethics of care as a prevalent perspective in moral reasoning, then the dearth of that moral perspective in the PME curriculum could represent a significant oversight.

An important consideration when using the MPS as a teaching tool is that it is not a stand-alone psychometric instrument that can be effectively used outside of an intentional ethics education curriculum that includes time for reflection, application exercises, and significant faculty development so the students have a guide to answer more advanced questions. Since subject matter experts (SMEs) in ethics are few in PME and in the military at large, this requires intentional faculty and leader development which is ongoing and refreshed on a regular basis to responsibly engage current academic practices and scholarly discussions in the field of ethics. To be effective at using this tool, the authors recommend an in-depth initial faculty development experience with a SME and ongoing quarterly or biannual deepening experiences as the faculty capacity and foundational knowledge increases.

Limitations and Future Research

The current study is not without limitations. The MPS is intended for practical applications within the classroom. Although it may provide insight on a case-by-case basis as a teaching tool, it is not a validated psychometric instrument. For those purposes, the psychometric properties of the questionnaire (i.e., reliability and validity) would need to be established, along with normative data for the target population.

The study used a cross-sectional design so could not examine issues around causality or changes over time. In addition, participants were from two institutions—NWC and SEA—so findings cannot be generalized to other PME settings or to broader military populations. Future research should include longitudinal designs to assess whether preferences change over time or with operational experience, and experimental designs to evaluate the impact of ethics of care instruction on decision-making performance. Future studies should also be conducted across a variety of PME institutions to assess whether the findings in the current study are replicated in those settings.

Conclusion

The consistent preference of ethics of care across large cohorts at the NWC and SEA challenges the assumption that military professionals’ ethical frameworks align most closely with the three traditionally dominant perspectives. This finding has several implications.

First, ethics of care should be explicitly included in PME ethics curricula, as it reflects the actual dispositions of many national security professionals attending the NWC and the SEA. Teaching all four perspectives enhances leaders’ abilities to engage across moral differences, an essential capability in Joint environments and courses with international partners. In addition, MPS results can also inform small-group facilitation strategies, improving team cohesion and ethical dialogue.

Faculty development should be an integral part of this addition to PME. Incorporating ethics of care requires faculty to be prepared to address relationality, empathy, and contextual factors alongside character, principles, and consequences.

A desired leader attribute within the profession of arms is that officers have the knowledge and skill to “make ethical decisions based on shared values of the Profession of Arms.”[17] Perhaps the greatest realization when using the MPS tool is that ethics of care is the primary moral framework used by officers and national security professionals attending the NWC and senior enlisted members attending the SEA. Ethics of care is a moral philosophy that brings a critical perspective that is missing in the three traditional moral views. It also brings insight into the salience of relationality, context, and care in moral deliberation that is critical for holistic moral deliberation and good decision-making. Furthermore, comparing and discussing different moral perspectives builds skills at perspective taking, empathy, uncovering and engaging with students’ assumptions, cognitive biases, and tendencies toward moral disengagement.

If PME institutions are largely ignoring ethics of care in their curricula, and ethics of care is a factor in their students’ moral reasoning, then PME is missing a key component in ethical reasoning. Accordingly, the current study has the potential to increase awareness of how national security practitioners deliberate moral issues by expanding curricula beyond the dominant moral perspectives of virtue, duty, and consequentialism.

Officers are expected to exercise sound moral judgment as members of the profession of arms.[18] Senior enlisted leaders are expected to recognize their role in promoting sound ethical decisions made within the profession of arms.[19] Good moral deliberation is essential to developing moral judgment and promoting a culture of sound ethical decision-making and execution in action.

If we expect U.S. military leaders to be explicit in their moral deliberations, we must give them the tools to succeed. Including ethics of care in PME is an operational necessity. The work at the NWC and SEA demonstrates that officers, national security professionals, and senior enlisted leaders implicitly use ethics of care in their moral decision-making. Moral perspectives can be complex, but that does not mean that students and faculty cannot effectively engage with that complexity. The MPS is a great place to start.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in the articles and reviews in this journal are solely those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the organizations for which they work, Marine Corps University, the U.S. Marine Corps, the Department of the Navy, or the U.S. government.

[1] Daniel Kahneman, Thinking Fast and Slow (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013).

[2] Virginia Held, “Chapter 1: The Ethics of Care as Moral Theory,” in The Ethics of Care: Personal, Political, and Global (New York: Oxford Academic, 2005), 9–28, https://doi.org/10.1093/0195180992.003.0002.

[3] Pauline Shanks Kaurin and George Baker, “Ethical Development for Mid-Career Leaders: Moral Perspective Sorter as a Teaching Tool,” Tidsskrift for Sjøvesen 1 (2022): 16–24.

[4] Held, “Chapter 1: The Ethics of Care as Moral Theory.”

[5] Held, “Chapter 1: The Ethics of Care as Moral Theory.”

[6] Todd May, Care: Reflections on Who We Are (Newcastle upon Tyne: Agenda Publishing, 2023), https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.1357301.

[7] Held, “Chapter 1: The Ethics of Care as Moral Theory.”

[8] Rosalind Hursthouse and Glen Pettigrove, “Virtue Ethics,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 11 October 2022.

[9] Richard M. Swain and Albert C. Pierce, The Armed Forces Officer (Washington, DC: NDU Press, 2017).

[10] Larry Alexander and Michael Moore, “Deontological Ethics,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 11 December 2024.

[11] Julia Driver, “History of Utilitarianism” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 31 July 2025.

[12] Held, “Chapter 1: The Ethics of Care as Moral Theory.”

[13] Held, “Chapter 1: The Ethics of Care as Moral Theory.”

[14] See Held, “Chapter 1: The Ethics of Care as Moral Theory.”

[15] Kahneman, Thinking Fast and Slow.

[16] Lawrence Kohlberg, Essays on Moral Development, vol. 1, The Philosophy of Moral Development: Moral Stages and the Idea of Justice (San Francisco, CA: Harper & Row, 1981).

[17] LtGen Glen D. VanHerek, USAF, CJCSI 1800.01F, Officer Professional Military Education Policy (Washington, DC: Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, 15 May 2020).

[18] VanHerek, CJCSI 1800.01F, Officer Professional Military Education Policy.

[19] CJCSI 1805.01C, Enlisted Professional Military Education Policy (Washington, DC: Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, 1 November 2021).

About the Authors

Dr. Pauline Shanks Kaurin holds a PhD in philosophy from Temple University, specializing in military ethics, just war theory, and applied ethics. She is currently a senior research associate at the Inamori International Center for Ethics and Excellence at Case Western Reserve University, OH. She served as the Stockdale Chair and a professor of professional military ethics at the College of Leadership and Ethics at U.S. Naval War College from 2018 to 2025. She was chair of the Department of Philosophy at Pacific Lutheran University, WA, from 2012 to 2018 and a teaching faculty member from 1997 to 2018. Her publications include Achilles Goes Asymmetrical: The Warrior, Military Ethics and Contemporary Warfare (2014) and On Obedience: Contrasting Philosophies for Military, Citizenry and Community (2020). Current works in progress include an account of military honor rooted in ethics of care (forthcoming, 2026). She was featured contributor for The Strategy Bridge and has published in Clear Defense, The Wavell Room, Newsweek, War on the Rocks, Grounded Curiosity, U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, Just Security, as well as a variety of academic journals.

Dr. George Baker is an associate professor in the College of Leadership and Ethics at the U.S. Naval War College. He is the director for the Leadership in the Profession of Arms course and serves as associate director at the Navy Senior Enlisted Academy. In both programs, he focuses on leader development in the profession of arms. Dr. Baker retired after 30 years serving in the U.S. Submarine Force before moving on to graduate education. He holds a BS in electrical engineering from the U.S. Naval Academy, an MA in education from the University of Rhode Island, an MA in national security and strategic studies from the U.S. Naval War College, and an EdD in organizational leadership and communications from Northeastern University.

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5227-9010

Dr. Leigh Ann Perry is an associate professor of psychology and behavioral science in the College of Leadership and Ethics at the U.S. Naval War College, focusing on resilience, holistic wellness, and leader development. She founded and directs the Cognitive Fitness and Mindful Resilience Initiative at the NWC to provide education and resources for utilizing mindfulness as a tool for cognitive fitness, resilience, and performance optimization within the Department of the Navy. Prior to joining the NWC and focusing her work on positive psychology and leader development, Dr. Perry worked for the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit, Naval Criminal Investigative Service, and Facebook’s Global Security team focusing on the analysis of violent criminals, terrorists, and dangerous organizations. She holds a PhD and an MA from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, in clinical and community psychology and a BS in psychology and sociology from Fordham University. She also studied psychology and sociology at Oxford University.

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3330-3118