International Perspectives on Military Education

volume 2 | 2025

Endurance and Executive Function

Implications for Military Education from a Study of Marine Officer Fitness and Cognition

Captain Luke S. Gilman, USMC

https://doi.org/10.69977/IPME/2025.006

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

APPENDIX

Abstract: This study investigates whether physical fitness predicts academic performance in military officers by analyzing data from 541 Marine Corps lieutenants at The Basic School in Quantico, Virginia. While decades of research demonstrate that exercise enhances cognition, no study has examined this relationship using military education outcomes. Statistical analysis revealed that cardiovascular fitness, particularly when measured under load, correlates with higher academic performance among male officers. Endurance course time emerged as the strongest predictor of grade point average (β = -.25, p < .01), followed by gender differences (β = -.24, p < .01), with females scoring nearly 4 percentage points higher when controlling for other variables. Among males, maneuver under fire scores additionally predicted academic performance (β = -.17, p < .05). Notably, muscular fitness showed no relationship with cognitive outcomes, suggesting that aerobic capacity may be more relevant for academic success than isolated strength measures. These findings carry practical implications for professional military education: programs that emphasize cardiovascular conditioning under load may create conditions that support the complex thinking required in modern military operations. The study suggests that integrating endurance assessments could aid talent identification and supports instructional design that blend physical rigor with intellectual development.

Keywords: physical fitness, cognition, cognitive performance, professional military education, PME, officer training

Introduction

The U.S. Marine Corps describes professional military education (PME) as both the transmission of foundational military knowledge and the cultivation of intellectual habits necessary to mastering the art and science of war.[1] Learning, Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication (MCDP) 7, expands on this notion of intellectual habits, challenging Marines to cultivate an “intellectual edge,” defined as a set of cognitive competencies which include “problem framing, mental imaging, critical thinking, analysis, synthesis, reasoning, and problem solving.”[2] These competencies represent top-down, higher-order cognitive processing skills that largely draw from core executive functions such as working memory, cognitive flexibility, and inhibitory control. While the analogy has its limitations, it can be useful to conceptualize cognition in computational terms: if cognitive strategies are analogous to software, the body and brain serve as the hardware that support such software. Discussion surrounding the optimization of human performance in both warfare and education necessarily requires consideration of the interplay between brain and body, lest it overlook a key component of cognition.

Decades of research demonstrate that exercise triggers chemical changes in the brain that enhance learning and memory.[3] Acute exercise has been shown to increase a variety of neurotrophins, hormones, and other chemical compounds which support adaptations that are favorable to learning, concentration, and memory through neuroplasticity.[4] Production of such molecules are frequently reported to exist in a dose-response relationship to exercise, where the volume of increase is directly tied to the duration and intensity.[5] Additionally, psychological research indicates that regular exercise builds self-control and mental resilience, traits critical for both academic achievement and military leadership.[6]

Despite extensive laboratory evidence linking fitness to cognition, few studies have examined this relationship using military education data. The current study addresses this gap by analyzing whether specific aspects of physical fitness predict cognitive performance in Marine officers undergoing initial training. If certain fitness markers reliably correlate with cognitive outcomes, this information could inform how military institutions structure their education programs to optimize both physical and intellectual development as well as aid talent management.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

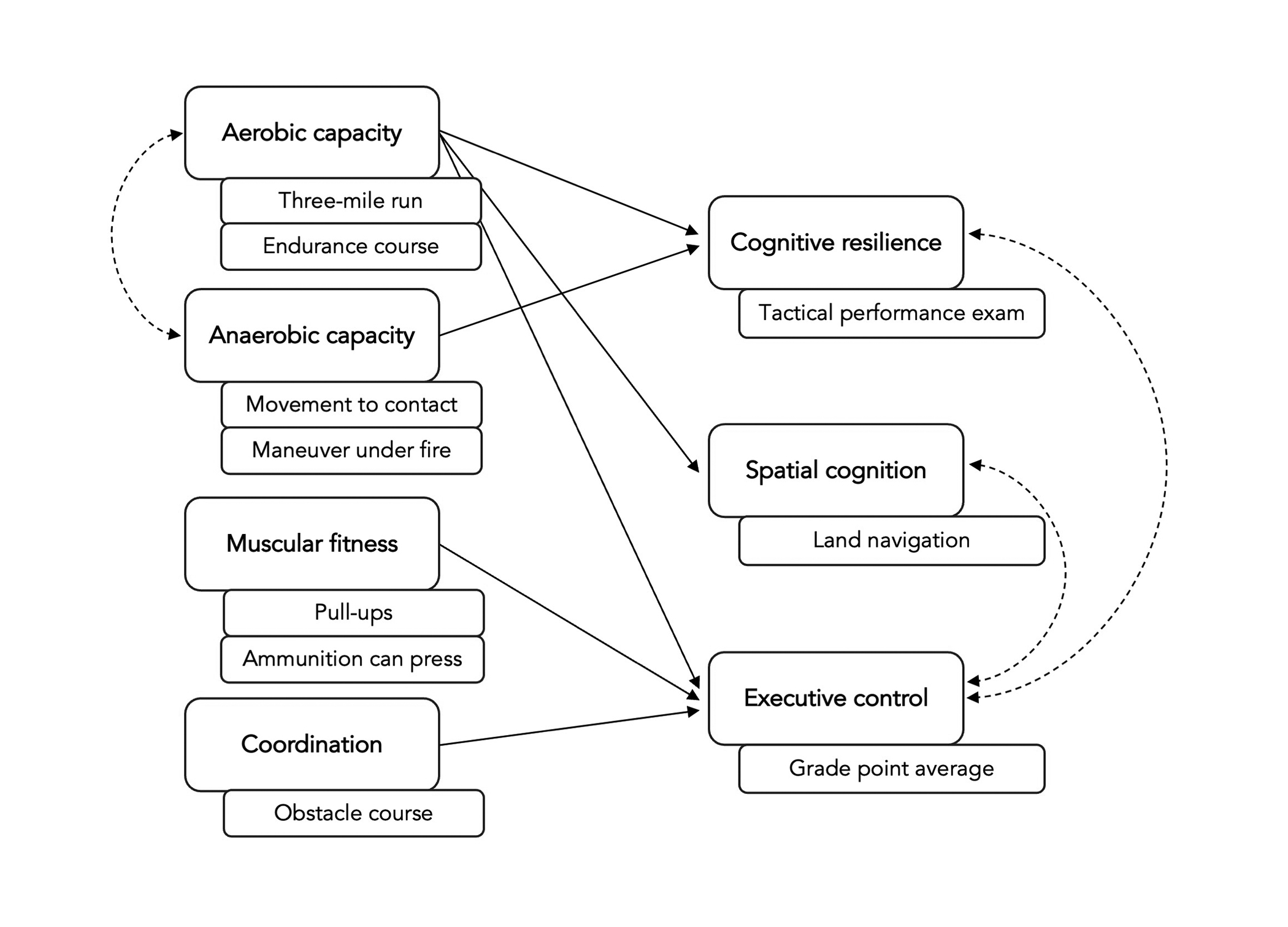

This study examines the following question: Do physically fit Marine officers perform better academically? Based on prior research, the author hypothesized that higher aerobic capacity would predict executive control, cognitive resilience, and spatial cognition in Marine Corps officers; that anaerobic capacity would positively cognitive resilience; that muscular fitness would predict executive control; and that coordination would predict executive control. The author also expected aerobic and anaerobic capacity to be correlated, and each cognitive domain to be significantly correlated. Figure 1 summarizes the operational measures and the hypothesized relationships.

Figure 1. Hypothesized relationships between variables

Source: courtesy of the author, adapted by MCUP

Literature Review: The Fitness-Cognition Connection

Physical activity produces both immediate and long-term changes in brain structure and function. During exercise, the body releases several key molecules that support brain health. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is a neurotrophin that is essential for activity-dependent synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory.[7] Moderate-to-vigorous exercise markedly increases BDNF concentrations, and research in rodents has shown that regular training amplifies this acute response over time.[8] Meta-analytic evidence shows that sessions of at least 40 minutes at intensities above 65 percent of maximal oxygen uptake (VO2 max), performed two to three times weekly, provide the greatest stimulus for sustained BDNF up-regulation and associated cognitive benefits.[9] Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) is a growth hormone that stimulates neural cell proliferation and differentiation.[10] Both aerobic and resistance exercise boost circulating IGF-1, with resistance training producing the largest increase.[11] Furthermore, higher IGF-1 levels are associated with better cognition in aging populations, highlighting its role in exercise-mediated brain benefits.[12] Catecholamines are a set of three molecules in the body that function as both neurotransmitters and hormones, depending on the context: dopamine, epinephrine (adrenaline), and norepinephrine (noradrenaline).[13] During exercise, dopamine acts primarily as a neurotransmitter to regulate motivation and motor learning, while epinephrine and norepinephrine are associated with attention and arousal.[14] Finally, lactate, a byproduct of anaerobic metabolism and once considered a metabolic waste product, actually fuels brain cells and promotes neuroplasticity.[15]

Beyond biological mechanisms, exercise strengthens psychological traits that support academic success. The “strength model of self-control” suggests that willpower functions like a muscle: it can be depleted through use but also strengthened through training.[16] Studies show that individuals who maintain regular exercise routines demonstrate better self-control across multiple life domains, from academic performance to personal habits.[17] This psychological resilience may be particularly relevant in military education, where students must sustain focus through demanding coursework while managing various stressors.

Evidence from Military Populations

Limited research has examined fitness-cognition relationships in military samples. A study of 148 U.S. airmen found that 12 weeks of combined aerobic and resistance training improved memory, processing speed, and problem-solving abilities. [18] Longitudinal Swedish military recruit data from more than 1 million participants revealed that cardiovascular fitness, but not muscular strength, predicted intelligence test scores. [19] However, to the knowledge of the author, no published studies have examined whether fitness predicts academic performance in professional military education settings.

Methods

The study analyzed archival data from 541 Marine Corps lieutenants (435 males, 106 females) attending The Basic School (TBS), the six-month course that all Marine officers complete before undergoing training in their military occupational specialties. Participants ranged from 20 to 41 years old (M = 24.2, SD = 3.57). The dataset included physical fitness scores, academic grades, and basic demographics but lacked information about prior education, commissioning source, or other potentially relevant factors (see appendix, table 1, for complete descriptive statistics).

Measures

The study examined seven distinct metrics of physical fitness performance as independent variables: two events from the Marine Corps Physical Fitness Test (PFT), all three events contained within the Combat Fitness Test (CFT), the TBS obstacle course, and the TBS endurance course. Events included from the PFT were pull-ups and three-mile run times (plank times were excluded from consideration as 100 percent of the sample achieved the maximum score). Events within the CFT include a timed 880-yard run referred to as the movement to contact (MTC), a single set of maximum 30-pound ammunition can overhead presses within two minutes, and a high-intensity obstacle course referred to as the maneuver under fire (MUF). The dependent variables included student GPA, which represents cumulative performance on five written academic examinations, two land navigation performance evaluations, and one written examination administered in a field environment in a state of stress called the Tactical Performance Exam (TPE). While the cognitive performance measures are admittedly imperfect proxies for specific cognitive domains (e.g., GPA reflects many factors beyond executive function, including prior knowledge, study habits, and test-taking skills), they represent real-world outcomes that matter for military officer development. The use of actual academic grades rather than laboratory cognitive tests provides practical relevance at the cost of some construct precision.

Results

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 30.0.[20] Variables were each assessed for normality through visual inspections of histograms as well as skewness and kurtosis values.[21] Correlation coefficients were generated and examined for potential issues of collinearity among predictor variables. Variance inflation factor (VIF) values were additionally reviewed for issues of collinearity. Given the highly related nature of several measures of fitness (e.g., three-mile run and MTC), some degree of collinearity was expected. Variables were then assessed for assumptions of linearity and homoscedasticity prior to inclusion in the models. Finally, multiple regression models were run for GPA and the TPE. Due to violations of normality, land navigation was deemed unable to be included as a dependent variable in a regression model. Each model was run three times, once for each gender and once with all participants. While the total sample was N = 541 after data were collected, only participants containing a complete set of values for each variable were included within the models. This resulted in sample sizes of n = 54 for females and n = 288 for males. Alpha level for statistical significance was set at p < .05.

Data Transformation

Variables of fitness that were time based (three-mile run, MTC, MUF, obstacle course, and endurance course) were all converted into total number of seconds. For example, an individual who ran 20 minutes for three miles was assigned a score of 1200.00. Due to non-normal distributions observed for both genders within the pull-up variable, pull-ups were transformed into a dichotomous, categorical variable based on whether an individual completed the maximum number of repetitions for their respective age and gender. The data were stratified by gender prior to generating correlation coefficients and regression models to account for expected differences in fitness scores among male and female participants.

Key Finding: Cardiovascular Fitness Is Related to Academic Success in Male Officers

Among male officers, every measure of cardiovascular fitness showed significant negative correlations with academic performance (recall that lower times indicate better fitness, therefore, a negative correlation aligns with the hypothesized relationship) (see appendix, table 3). The strongest relationship emerged between endurance course time and GPA (r = -.25, p < .001), followed by three-mile run time (r = -.20, p < .001). Multiple regression analysis confirmed that endurance course time was the strongest predictor of GPA among males (β = -.25, p < .001) when controlling for age and other fitness variables. In practical terms, male officers who completed the endurance course 1 standard deviation faster than the mean scored approximately 1.5 percentage points higher on their academic grades. The MUF course, another load-bearing cardiovascular event, also significantly predicted academic performance (β = -.17, p < .05). Together, the model explained 10 percent of variance in male GPAs, a small but not insignificant effect given the many factors that influence academic success (see appendix, table 8).

Gender Differences Warrant Further Investigation

Female officers scored nearly 4 percentage points higher on academic assessments when controlling for fitness and age (β = -.24, p < .01) (see appendix, table 9). However, no single fitness variable significantly predicted female academic performance. This finding may reflect limited statistical power due to the small female sample (n = 54) rather than a true absence of relationship. The model explained 24 percent of variance in female GPAs, though age was the only significant individual predictor (see appendix, table 7).

Muscular Fitness Shows No Relationship with Cognition

Contrary to hypothesized relationships, pull-up performance showed no correlation with any cognitive outcome for either gender (see appendix, table 5), suggesting that upper body strength may not offer the same cognitive benefits as cardiovascular fitness. It is worth noting, however, that the transformation of pull-up scores into a binary, dichotomous variable likely reduced measurement precision and therefore this finding should be taken lightly.

Performance under Stress Yields Mixed Results

The Tactical Performance Exam, designed to assess cognitive function under field stress, showed weak relationships with fitness variables. While individual fitness measures correlated with TPE scores in simple regressions, multiple regression models failed to identify significant predictors (see appendix, tables 10, 11, and 12). This may indicate that performance under acute stress involves different mechanisms than classroom learning, but it is more likely that the TPE lacks sensitivity to detect fitness-related cognitive differences.

Discussion: Implications for Military Education

Why Does Cardiovascular Fitness Matter More than Strength?

The selective relationship between aerobic fitness and academic performance aligns with research showing that sustained cardiovascular exercise consistently produces the strongest neurobiological adaptations. Aerobic training increases blood flow to the prefrontal cortex, stimulates growth factor production, and enhances mitochondrial function in brain cells. These mechanisms directly support the sustained attention, working memory, and cognitive flexibility required for academic learning. The relative impact of load-bearing endurance on GPA compared to unloaded aerobic capacity was not expected and deserves attention. The endurance course, a five-mile run under combat load, predicted academic performance more strongly than the unloaded three-mile run. This is notable as the two measures were thought to measure the same underlying construct in aerobic capacity. The difference may reflect absolute rather than relative aerobic capacity, as carrying weight neutralizes the advantage of lower body mass. Alternatively, success in prolonged, uncomfortable physical challenges may indicate underlying psychological traits like grit or self-discipline that simultaneously support academic achievement.

Alternative Explanations and Limitations

Several factors limit the study’s findings. First, correlation does not establish causation. Physically fit officers might perform better academically due to underlying personality traits like conscientiousness rather than fitness itself. Second, using GPA as a proxy for executive function is somewhat imprecise; grades reflect numerous factors including prior knowledge, study habits, instructor variability, and test-taking skills. Third, missing demographic data about education backgrounds, commissioning sources, and others prevents a more complete understanding of covariates. The gender disparity in findings also requires careful interpretation. The small female sample size (n = 54) provided limited statistical power to detect relationships that may exist. Additionally, sociocultural factors affecting female officers’ experiences at The Basic School could influence both fitness performance and academic outcomes in ways not captured by this analysis. Future research with larger, more balanced samples should be conducted before drawing conclusions about gender differences.

Practical Applications for Professional Military Education

Despite the limitations, the findings suggest several practical applications for military education programs. First, institutions should protect or enhance cardiovascular training opportunities, particularly surrounding cognitively demanding instruction. If aerobic exercise creates neurobiological conditions favorable to learning, intentionally scheduling targeted cardiovascular training around classroom instruction could optimize academic outcomes. Second, programs that require decision-making under fatigue should deliberately rehearse that state. Incorporating loaded movement into tactical decision exercises, staff planning drills, or problem-solving scenarios could better prepare officers for the cognitive demands of combat. Third, endurance metrics might supplement traditional selection and assessment tools. While fitness alone should never determine educational or career opportunities, cardiovascular capacity under load could serve as a small but useful indicator for identifying officers likely to excel in cognitively demanding assignments. This is particularly relevant for highly competitive programs and billets, such as funded doctoral education opportunities or schools like the School of Advanced Warfighting, where the performance margins between candidates are extremely slim and additional discriminating factors are valuable. Finally, military education should embrace curricula that intentionally blend physical and intellectual challenges. Rather than treating fitness and academics as separate domains, courses could design learning experiences that develop both simultaneously. Examples might include land navigation exercises requiring route planning under time pressure, tactical decision games conducted intermittently during foot marches, or problem sets completed between physical training stations.

Future Research Directions

This study raises questions warranting further investigation. Future research should employ validated cognitive assessments rather than grades, allowing more precise measurement of specific executive functions. Including psychological measures of grit, self-control, and motivation in regression models would help disentangle whether fitness directly enhances cognition or merely correlates with traits that support both physical and academic performance. Experimental designs that manipulate training regimens while tracking cognitive outcomes would help determine whether these relationships are causal. For instance, randomly assigning PME students to different physical training programs emphasizing aerobic, anaerobic, or resistance training, then comparing academic performance would clarify which fitness components most benefit cognition. Longitudinal studies following officers through multiple education levels could reveal whether fitness habits and cognition relationships persist or evolve across career stages. Research should also examine these relationships across different military populations and educational contexts. Do similar patterns emerge in enlisted professional military education? How do deployment experiences affect the fitness-cognition relationship? Understanding these dynamics across diverse service member populations would support evidence-based policy for the total force.

Conclusion

This study provides initial evidence that cardiovascular fitness, particularly under load, correlates with academic success in Marine officers. While effect sizes are modest and causation was not established, the pattern suggests that aerobic capacity may serve as one indicator of cognitive potential in military education settings. More importantly, the findings highlight opportunities to design training that develops both the physical stamina and mental agility required for military leadership.

Professional military education has always recognized that effective military leaders need both strong bodies and sharp minds. This research suggests these qualities may be more interrelated than traditionally assumed. By understanding how physical and cognitive development interact, military institutions can create educational experiences that produce leaders capable of thinking clearly and making high quality decisions, even when exhausted, stressed, and challenged. In an era where military operations demand unprecedented cognitive performance, optimizing the fitness-cognition connection may provide an edge. The path forward requires continued research, thoughtful experimentation, and careful implementation. Fitness should complement, not replace, quality instruction and assessment. But for military education programs seeking every advantage in developing cognitively capable leaders, purposeful integration of the two domains may offer an additional layer of support.

Endnotes

[1] Marine Corps Order 1553.4B, Professional Military Education (PME) (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, 25 January 2008).

[2] Learning, Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication (MCDP) 7 (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, 2020), chaps. 1, 6.

[3] Joseph E. Donnelly et al., “Physical Activity, Fitness, Cognitive Function, and Academic Achievement in Children: A Systematic Review,” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 48, no. 6 (June 2016): 1197–222, https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000901; J. L. Etnier et al., “The Influence of Physical Fitness and Exercise upon Cognitive Functioning: A Meta-analysis,” Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 19, no. 3 (1997): 249–77; and N. E. Logan et al., “Trained Athletes and Cognitive Function: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis,” International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 21, no. 4 (2023): 725–49, https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2022.2084764.

[4] Blai Ferrer-Uris et al., “Can Exercise Shape Your Brain? A Review of Aerobic Exercise Effects on Cognitive Function and Neuro-Physiological Underpinning Mechanisms,” AIMS Neuroscience 9, no. 2 (2022): 150–74, https://doi.org/10.3934

/Neuroscience.2022009.

[5] N. Feter et al., “How Do Different Physical Exercise Parameters Modulate Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor in Healthy and Non-Healthy Adults?: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression,” Science & Sports 34, no. 5 (October 2019): 293–304, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scispo.2019.02.001; and Jennifer J. Heisz et al., “The Effects of Physical Exercise and Cognitive Training on Memory and Neurotrophic Factors,” Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 29, no. 11 (2017): 1895–907, https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_a_01164.

[6] Sean P. Mullen and Peter A. Hall, “Editorial: Physical Activity, Self-Regulation, and Executive Control across the Lifespan,” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 9 (November 2015): 614, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2015.00614.

[7] Patrick Z. Liu and Robin Nusslock, “Exercise-Mediated Neurogenesis in the Hippocampus via BDNF,” Frontiers in Neuroscience 12, no. 52 (February 2018), https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2018.00052.

[8] Liu and Nusslock, “Exercise-Mediated Neurogenesis in the Hippocampus via BDNF”; and R. A. Johnson et al., “Hippocampal Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor but Not Neurotrophin-3 Increases More in Mice Selected for Increased Voluntary Wheel Running,” Neuroscience 121, no. 1 (September 2003): 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4522(03)00422-6.

[9] Feter et al., “How Do Different Physical Exercise Parameters Modulate BDNF?”

[10] Adam H. Dyer et al., “The Role of Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1) in Brain Development, Maturation and Neuroplasticity,” Neuroscience 325 (June 2016): 89–99, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.03.056.

[11] Diego de Alcantara Borba et al., “Can IGF-1 Serum Levels Really Be Changed by Acute Physical Exercise?: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Journal of Physical Activity and Health 17, no. 5 (2020): 575–84, https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2019-0453; A. J. Schwarz et al., “Acute Effect of Brief Low- and High-Intensity Exercise on Circulating Insulin-Like Growth Factor (IGF) I, II, and IGF-Binding Protein-3 and Its Proteolysis in Young Healthy Men,” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 81, no. 10 (1996): 3492–97, https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.81.10.8855791; and Andrea Deslandes et al., “Exercise and Mental Health: Many Reasons to Move,” Neuropsychobiology 59, no. 4 (2009): 191–98, https://doi.org/10.1159/000223730.

[12] Cellas A. Hayes et al., “Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 and Cognitive Health: Exploring Cellular, Preclinical, and Clinical Dimensions,” Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 76 (January 2025): 101161, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2024.101161.

[13] Bassem Khalil, Alan Rosani, and Steven J. Warrington, “Physiology, Catecholamines,” in StatPearls (Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing, 2024).

[14] Guendalina Bastioli et al., “Voluntary Exercise Boosts Striatal Dopamine Release: Evidence for the Necessary and Sufficient Role of BDNF,” Journal of Neuroscience 42, no. 23 (June 2022): 4725–36, https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2273-21.2022; and Hassane Zouhal et al., “Catecholamines and the Effects of Exercise, Training and Gender,” Sports Medicine 38, no. 5 (2008): 401–23, https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200838050-00004.

[15] Anna Falkowska et al., “Energy Metabolism of the Brain, Including the Cooperation between Astrocytes and Neurons, Especially in the Context of Glycogen Metabolism,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 16, no. 11 (October 2015): 25959–81, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms161125939; and C. L. Powell, A. R. Davidson, and A. M. Brown, “Universal Glia to Neurone Lactate Transfer in the Nervous System: Physiological Functions and Pathological Consequences,” Biosensors 10, no. 11 (2020): 183, https://doi.org/10.3390/bios10110183.

[16] Carolyn L. Powell, Anna R. Davidson, and Angus M. Brown, “Universal Glia to Neurone Lactate Transfer in the Nervous System: Physiological Functions and Pathological Consequences,” Biosensors 10, no. 11 (November 2020): 183, https://doi.org/10.3390/bios10110183.

[17] Elliot T. Berkman, Alice M. Graham, and Philip A. Fisher, “Training Self-Control: A Domain-General Translational Neuroscience Approach,” Child Development Perspectives 6, no. 4 (2012): 374–384, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00248.x; Megan Oaten and Ken Cheng, “Improved Self-Control: The Benefits of a Regular Program of Academic Study,” Basic and Applied Social Psychology 28, no. 1 (2006): 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324834basp2801_1; and Zhiling Zou et al., “Aerobic Exercise as a Potential Way to Improve Self-Control after Ego-Depletion in Healthy Female College Students,” Frontiers in Psychology 7 (April 2016), https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00501.

[18] Christopher E. Zwilling et al., “Enhanced Physical and Cognitive Performance in Active Duty Airmen: Evidence from a Randomized Multimodal Physical Fitness and Nutritional Intervention,” Scientific Reports 10 (2020): 17826, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-74140-7.

[19] Maria A. I. Åberg et al., “Cardiovascular Fitness Is Associated with Cognition in Young Adulthood,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106, no. 49 (December 2009): 20906–11, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0905307106.

[20] “IBM SPSS Statistics Desktop 30.0” IBM.com, last modified 1 March 2025.

[21] Skewness refers to the extent to which data are not symmetrical; kurtosis refers to how the tails of a distribution differ from the normal distribution.

About the Author

Luke S. Gilman is a captain in the U.S. Marine Corps. He is a 7208 air support control officer and currently serves as an 8802 training and education officer at Marine Corps University. He holds a BA in theology and MA in educational leadership from Wheeling Jesuit University, as well as a MS in educational psychology from George Mason University.

https://orcid.org/0009-0002-7340-6039