International Perspectives on Military Education

volume 2 | 2025

Deepening Army Officers’ Initial Training

Conclusions from a Comparative Analysis between the U.S. and the Spanish Army

Colonel Enrique Gaitán Monje, PhD, Spanish Army; and Andrés de Castro, PhD, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia, Spain

https://doi.org/10.69977/IPME/2025.007

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: One of the main elements that has been absent in the academic literature exploring officer training in Spain is the fact that there is no specific training that lieutenants undertake before being promoted to captains. In practical terms, that means when lieutenants are trained, the Spanish military is de facto forming also captains. Thus, this article’s research question is whether that might constitute a weakness and, if it is, what would be the best way to solve it. In that regard, as means for benchmarking, the authors conducted a comparative analysis with the U.S. model. In a later stage, they designed and implemented a qualitative approach through focus groups and interviews with all the directors of the army academies: Academia General Militar (AGM) and all the branch academies (infantry, cavalry, artillery, engineers, signal, and aviation). They then analyzed the data using a coding tree that could contribute to presenting the discussion. The main conclusion is that even if having a separate course for captains would be positive, the impact to the army should also be carefully considered to minimize possible derived inconveniences.

Keywords: Spanish Army, military training and education, professional competencies

Introduction

The professional competences army cadets are meant to achieve to become lieutenants and captains are in constant change. That has a direct impact on the training programs they need, as stated by Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD): “the complexity of the demands generated by an increasingly interdependent, changing and conflictual world places the objectives of education and the strategies to achieve education goals in center stage of the debate on broad educational reform.”[1] The importance for Spain has been condensed in Entorno Operativo 2035 (Operational Environment 2035) issued by the Spanish Armed Forces. It states that they are living in a changing and uncertain world and, consequently, training programs will need to be updated according to emergent technologies and evolving operational procedures.[2]

In the process of this public policy and academic discussion, the authors undertook an ambitious research project that would examine whether the Spanish Army should redefine the level of professional competences to be achieved by its cadets to become officers and, in particular, the level of those related to the specific branch. They asked: Should that level be left up to company command for action, or should cadets obtain the required specific professional competences to command platoon-level units?

Thus, the main objective of this article is to first conduct rigorous academic research to reach valid academic conclusions to recommend the level of professional competencies that can be achieved by Spanish Army cadets to become officers. In the latter case, the Spanish Army would need to require lieutenants, prior to their promotion to the rank of captain, to attend a currently nonexistant educational program to acquire those specific competencies required at the company level.

The answer to this question is important for two main reasons. First, because as stated above, the Spanish Army precommissioning officers’ curriculum is very dense due to the demanding professional competencies currently required for cadets: reducing the level of specific competencies would alleviate the existing high workload for cadets; as Rafael Martínez states “cadets educational training should be adapted to new realities, not based on addition of contents but on its modernization and reform.”[3] Second, there is no educational program to prepare or complete the preparation of lieutenants for the moment they are promoted to captains and are required to command a company-type unit, which usually happens about five years after being commissioned.

Regarding the methodology, one of the main strengths of this research is the superb access to the field as a result of the authors’ involvement in professional military education. This was combined with the appropriate design of the empirical research with combined participatory observation and conducting interviews with key informants, which rounded out the research and allowed for quality data that could later be analyzed and processed.

Officer’s Professional Competence

The issue of officer’s professional competence has been covered in relevant literature. Thus, certain authors such as Manuel Riesco González observed that educational curricula must focus its goals on students’ acquisition competencies.[4] However, there is no universal concept for professional competence. On the contrary, we find diverse theories and definitions that might lead some to confusion.[5]

According to Riesco Gonzalez, there are three main approaches: the first, which is focused on personal attributes (mainly attitude and capabilities); the second, which conceives competence as the capability to execute tasks; and the third, which is the integration of both.[6]

As a result, according to Riesco Gonzalez, competencies are related to capabilities, skills, or internal qualities.[7] In addition, if we observe more specialized academic literature, models address other aspects of leadership: attributes, traits, characteristics and function, task, behavioral, which may prove to be more valuable.[8]

Thus, in the framework of the Tuning project “competencies are described as points of reference for curriculum design and evaluation.”[9] As a result, competence represents a dynamic combination of knowledge, understanding, skills, and abilities and refers to implicit characteristics of a student who is expected to perform at a certain level. As a result, knowledge, skills, motivation, values, and personality constitute those characteristics that need to be developed.

In sum, competence would be the intersection of these components: knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values. While knowledge and skills (specific competences) are easier to be developed, motivation, values, and personality (generic competences) require more effort according to Mario de Miguel Diaz.[10]

While specific competencies are more closely associated to each area of knowledge, generic competencies are shared by most university degrees. However, both generic and specific competences need to be integrated during the teaching–learning process and cannot be developed separately.[11] Thus, it is not possible to develop generic competencies if this process is not done in the context of the particular area of knowledge within a specific job application. Moreover, professional competencies need to be exercised in the appropriate professional context or situation so that the student can respond in a proper way.[12]

Therefore, according to de Miguel Diaz, it is important for the student to face situations in which both types of competences, generic and specific, are integrated and tested.[13] Consequently, students’ competencies grow according to a continuous process in which the context changes and new responses are required. Required competencies are also subject to change, and individuals’ responses that were appropriate in the past might no longer be.

This way, in the specific context of the military, many academics such as Giulio Dohuet believe that anticipation is paramount when preparing for war:

Victory smiles upon those who anticipate the changes in the character of war, not upon those who wait to adapt themselves after the changes occur. In this period of rapid transition from one form to another, those who daringly take to the new road first will enjoy the incalculable advantages of the new means of war over the old.[14]

As a result, the Spanish Army developed Operational Environment 2035, which systematizes those operational circumstances which encompass all imaginable factors that need to answer three main questions: who (those actors that constitute the threat), where (likely operating scenarios), and how (the way future conflicts will be).[15]

The current literature shows that modern armies are focused on future operational environments with a time horizon from 15 to 20 years. This is the case of the Spanish Armed Forces, the Spanish Army in particular, and the U.S. Army, which are used as case studies for this article and with the objective to gather the necessary categories for benchmarking. In this regard, the authors observed how this period allows them to transform their doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership and education, personnel, and facilities (DOTMLPF).[16]

Operational Environment 2035 states that changes are linked to revolutionary technological developments and this reality implies that life-long learning will be required to maintain our soldiers’ readiness along their careers.[17]

Regarding the army element of the Spanish Armed Forces, in 2018, the Spanish Army issued Future Land Operating Environment 2035, which states that

Their values and competences will be built upon an effective recruitment process, training, and preparation that will be updated throughout a career-long process. . . . We can state that soldiers must have not only a sound technological education but also a humanist one that allows them to develop understanding and empathy with cultural diversity, and resilient personality built upon solid human values that serve as guidelines to make decisions and endure sacrifice.[18]

These ideas are not exclusive of the Spanish Armed Forces but are shared by other North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) allies. For example, the U.S. Army’s “analysis of the Operational Environment shows these trends to be inexorable, bringing with them rapid and often uncomfortable changes that will force us to reevaluate many aspects of strategy, policy, and our very lives. . . . The first, and most important lesson is to understand and internalize the idea that we stand at a precipice of change, where our time-honored successes and the ideas, concepts, doctrine, equipment, training, and personnel that achieved them probably are insufficient to achieve successes in the near term, and certainly are, if not revised or re-assessed, insufficient in the mid to long-terms.”[19]

Consequently, in the benchmarking designed by the authors, they observe how the U.S. Army found as a solution that a career-long, learner-centric approach to training and education is needed, which was articulated further by then U.S. Army Chief of Staff general Mark A. Milley: “Leadership success in this operating environment requires military, physical, and intellectual expertise that is continuously developed throughout a career.”[20]

In the case of Spain, Spanish Army Chief of Staff General Amador Enseñat y Berea has a similar view, by which the Spanish Army personnel need to keep developing. This means that military at all ranks need to be the focus of education and training and that it lasts the length of their whole career.[21]

Young officers’ education and training programs duration usually takes about five years in many countries, including the U.S. and the Spanish Army. These programs provide cadets with the professional generic and specific competencies required to become officers.

According to Bunk, “Professional knowledge and skills (specific competencies) become obsolete and even useless increasingly faster due to the rapid technical and economical evolution.”[22] Academic literature proves that these competencies are easier to develop than generic competencies by means of education programs and that main goal is achieved when both competencies are integrated.

Also, the key point for any education program for young officers is to correctly identify the appropriate professional competencies (both generic and specific) based on the future operational environment in which they will need to operate.

The point is that there is no general agreement about professional competencies, which has been developed by Horey and Fallesen, “leadership competency modeling is an inexact science and many frameworks present competencies that mix functions and characteristics, have structural inconsistencies, and may be confusing to potential end users.” These authors demonstrate that each of the U.S. Services (Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard) use similar but different frameworks, and they believe that “the nature and purpose of these organizations are similar enough that there should be great similarities in how leadership is defined, described and displayed within them.”[23]

Conversely, the European Union (EU) is also aware of the importance of correctly identifying the appropriate professional competencies for officers. With the aim of increasing interoperability among European armed forces, the EU launched the Sectoral Qualification Framework for the Military Officer Profession (SQF-MILOF). The goal of this tool is to support member states in developing and classifying military qualifications but also describing specific learning outcomes.[24]

It also seeks to provide member states with a cross-referencing tool for military qualifications so that those awarded in one member state can be compared with similar qualifications awarded in another member state.[25] However, even if it theoretically is a good tool, this initiative is still far from achieving these goals. Moreover, there is a need to achieve this kind of interoperability among countries, and within the Spanish Armed Forces there are also significant differences between how each service defines their officers’ professional competencies.

Spanish Army Educational Model and Officers’ Professional Competencies

In the Spanish Armed Forces, military education is regulated by Law 39/2007, by which officers’ military education is composed of precommissioning education and professional military education.[26] Although within the army there are several corps and different modalities of access and educational programs, the majority of the Spanish Army officers belong to the Cuerpo General de las Armas (CGA), which integrates all combat branches (Spanish Infantry, Cavalry, Artillery, Engineers, Communications, and Army Aviation) and follows the sin titulación access, meaning that cadets enter the military academy at ages 18–20 without previous higher education studies.[27] Since the bulk of Spanish Army Officers follows this way to become officers, it is the focus in this article.

This training program is intended “to provide the students with the necessary capacities to achieve the required professional profiles for the competencies defined by the Spanish Army Chief of Staff.”[28]

The curriculum analyzed here was in place between 2016 and 2024 and was intended to provide a wide scientific, technologic, and humanistic education through an engineering university degree while also providing military knowledge to provide cadets with all professional competencies and skills.[29]

According to Orden DEF/286/2016, this interdisciplinary education will produce commissioned officers who can perform assigned tasks based on their capacity to develop direction (command) and management activities in their branch. They must be ready to perform planning and control of military operations and other technical, logistical, administrative, and teaching tasks. Finally, they must be capable of performing leadership tasks with initiative, responsibility, and decision capacity.

According to Directiva 02/08, once commissioned, lieutenants are assigned as platoon leaders in units of their service branch for five years. After this period, an evaluation for promotion to the rank of captain is conducted, but it does not require any previous additional compulsory education program for company command qualification.[30]

According to Spanish Armed Forces regulations, competence is defined as “abilities to be acquired by the students, which must be demonstrated by means of knowledge, capacity and skills required for their use in the field of activity where they will perform their tasks, fundamentally those related to the first rank for officers. Competencies can be general and specific.”[31] In addition, general competencies are those that are common for each corps of officers, with general competencies there are generic and specific competencies as defined in the educational environment. While specific competencies are associated to a particular service branch, precommissioned officer’s education provides cadets with the required competencies and specializations to be commissioned as officers. Current armed forces regulations tasks each service to identify what those competences are.[32]

However, the Spanish Army decided that, during precommissioning education, cadets must achieve general competencies common to all Spanish Army officers from lieutenant rank and up as well as specific competencies up to the rank of captain.[33]

In the case of the Spanish Air Force, required professional competencies—transversal, general, and specific—are defined exclusively to achieve the rank of lieutenant.[34] The Spanish Navy defines common general competencies for all officers’ ranks and the specific competencies for lieutenants.[35]

Consequently, each Spanish service expects different levels of professional competence. If we focus on the Spanish Army, its precommissioning education program is, at least formally, more demanding from the point of view of professional competencies: captains’ tasks and responsibilities are more demanding and complex than those of lieutenants’ and this has an impact on education programs.

U.S. Army Educational Model and Officers’ Professional Competencies

The U.S. Army defines leader development as the “deliberate, continuous, sequential, and progressive process that grows soldiers into competent and confidents leaders of character. Leaders are developed through the career-long synthesis of the training, education, and experiences.”[36]

From the point of view of learning activities, the U.S. Army considers two main groups: initial military training (IMT) and professional military education (PME). While IMT is intended to provide foundational training required to become a soldier, PME provides leaders with appropriate education and is focused on rank or duty requirements.

At the officer level, the U.S. Officer Education System encompasses both IMT and PME and “provides progressive and sequential training throughout and officer’s career.”[37] Within this system and as part of IMT, there are two separate programs: Basic Officer Leaders Course Alpha (BOLC-A) and BOLC Bravo (BOLC-B). BOLC-A provides all required competencies to be qualified as an officer. BOLC-B is addressed to those who have qualified from BOLC-A and provides advanced competencies (infantry, artillery, etc.).

BOLC-A may be provided in different ways. For this article, the focus is the U.S. Military Academy of West Point (USMA) since it is the equivalent to the Spanish Academia General Militar (AGM): “The USMA provides a 4-year curriculum leading to a Bachelor of Science degree and commissioning as a second lieutenant”[38]

The USMA accomplishes its mission “to educate, train, and inspire the Corps of Cadets so that each graduate is a commissioned leader of character committed to the values of Duty, Honor, Country and prepared for a career of professional excellence and service to the Nation as an officer in the United States Army,” which is inspired in the Army’s strategy and vision 2028. The U.S. Army strategy describes a modern and dynamic battlefield, as described by General Milley, “Our graduates need to be ready to serve in any environment, and these operating environments are more multi-dimensional and evolving more rapidly than ever before.” This has implications in the USMA: “we must continuously improve our leader development system to meet the increasing challenges our graduates inevitably face.”[39]

The USMA accomplishes its mission applying the West Point Leader Development System (WPLDS), which is “its 47-month integrated system of individual development and leadership development, all within a culture of character growth.” It is composed of four programs: academic, military, physical, and character. The four of them are focused on facilitating cadets to achieve generic competences.[40]

After graduation, the new officers attend BOLC-B, where they receive “common core and technical training (specialized skills, doctrine, tactics, and techniques) associated with their specific branch specialties.” BOLC-B for most of the branches lasts 19 weeks in which the new officers get branch related specific competencies.[41]

BOLC-B aims to produce adaptive officers, steeped in the profession of arms and who are technically/tactically competent, confident, and capable of leading in unified land operations after their arrival at their first unit of assignment. It consists of common military skills and branch-specific qualification courses that provide newly commissioned officers an opportunity to develop their leadership, tactical, and technical tasks and supporting skills and knowledge required to lead in their future unit of assignment.

After a minimum of two years of duty as a first lieutenant, officers may be promoted to the rank of captain and attend the Captains Career Course (CCC), which normally happens between the fourth and seventh years of service.[42] The CCC is focused on qualifying first lieutenants to command at the company-unit level and provides advanced branch-specific training. CCC “emphasizes the development of leader competences while integrating recent operational experiences of the students with quality institutional training.”[43]

The CCC occurs at a pivotal time of an officer’s career. Although it is not considered as a transitional period for an officer between tactical, operational, and strategic art, it is still a critical period.[44] According to Army regulation,

The CCC provides O–3s with the tactical, technical and leader knowledge and skills needed to lead company-size units and serve on battalion and brigade staffs. It facilitates life-long learning through an emphasis on self-development. The curriculum includes common core subjects, branch-specific tactical and technical instruction, and branch-immaterial staff officer training.[45]

The U.S. Army considers it important to update this course so that it responds to demands dictated by war and a rapidly changing organizational and operational environment.[46] It develops leadership through a combination of institutional training and recent operational experience of the students. Course attendees have previously completed their first tour as officers and performed as a platoon leader, company executive officer, or junior staff officer at battalion level. According to Colonel William Raymond, the CCC should maintain high quality Small Group Leaders selecting the best trainers and update curriculum to be current, relevant, and rigorous.[47] The result of this, along with “an academic environment that allows for open dialog, reflection, intellectual challenges and exchanges of diverse operational experiences and perspectives” is an advanced educational outcome.[48]

The CCC has a history of revisions to be adapted to the new operational requirements and resources since the U.S. Army has consistently found that captains need more education, rather than an emphasis on training, and that education requires academic rigor and direct peer contact. It also recognizes the importance of the “socialization process,” where officers share experiences with their contemporaries in an academic environment. This process leads to reflection on “past experiences” to find perspective so that the learning process occurs by exchange of ideas and experiences.[49]

Since April 2023, the U.S. Army has implemented a modernized version of the CCC. According to this document, the new CCC has the following learning areas: army profession and leadership, branch skills, and warfighting and command. The duration of the CCC used to be 22 weeks and was composed of an 8-week common core section and a period of 13 weeks dedicated to particular branch’s tactics and technics. The modernized CCC includes a new distributed learning phase with 75 hours (the rest of the course is F2F), which is part of the common core that lasts 147.5 hours (instead of the previous 240 hours). This change allows an extension of branch education up to 727.5 hours (instead of the previous 560 hours).[50]

Methodology

To answer the research question, the authors divided the process in two phases. For the first phase, they benefited from the information from participatory observation to state the main elements of the discussion. In the second phase, they built a qualitative process of interviews, focusing on the six Spanish Army branch academies’ directors (colonels), the AGM director (general), and the Defense University Center (CUD) director and deputy director.[51]

To conduct the interviews, the authors arranged meetings and traveled to each of the academies. These meetings were executed in person with each of the directors and consisted of an introduction to the research subject formulating the research question and project and explaining the main differences between the U.S. Army model and the Spanish Army model. Each of the meetings lasted between one and a half and two hours. The meeting with the Engineers Academy (Hoyo de Manzanares, Madrid) encompassed engineers and signal academic programs, and the director (Engineer Branch) was accompanied by the deputy director (Signal Branch).

The authors conducted semistructured interviews, because they posed questions that could allow for debate, especially when required to correctly interpret the ideas addressed by each director. Consequently, the meetings were conducted in an informal and proactive way, allowing the authors to record the most interesting opinions, essential points, and conclusions.[52]

Comparative Analysis

Both, USMA and AGM’s educational models concur when comparing the expected professional competencies to be achieved: personnel attributes and capacity to perform tasks (knowledge, skills, motivation, values and personality) as army officers. At both institutions, cadets pursue generic and specific competencies to become army officers. The former ones are consolidated along the duration of their respective curriculum while being integrated with military specific competencies.

That is why, in the case of the USMA, its four programs (academic, military, physical, and character) are run simultaneously while, in the AGM, its curriculum (which used to integrate an engineering degree and other courses in addition to military training) is run with the AGM leadership plan complementing it.[53] Those generic competencies require time and effort to be achieved (four to five years); however, integrated with the specific ones, they accompany the officer along their entire career.

Modern armies assume that the future operational environment is uncertain and rapidly changing. Consequently, it will be required that its members adopt career-long education and training. This fact mainly impacts the specific competencies (e.g., military tactics and technics) that, once achieved, will require educational updates more frequently after officers are commissioned; contents learned today rapidly may become obsolete.

One of the most visible differences between both models is that the U.S. Army considers that specific competencies at company-command level are necessarily acquired once they get operational experience as lieutenants and by means of the CCC just prior to command this unit level.

Since promotion to captain occurs in the Spanish Army several years after being commissioned, it might be convenient to consider a two-part change in the education model: first, shortening the academy curriculum to achieve branch competencies at platoon-leader level prior to commission. Any missing components should then be provided to them in a second step by means of a rigorous academic program once they become experienced officers and prior to their company command.

But there is another factor that is paramount in this issue: the considerable increase of professional complexity between platoon leader and company commander responsibilities. As a result, this article’s research question focuses on whether the Spanish Army should redefine the level of professional competencies to be achieved by its cadets to become officers and, in particular, the level of those that are related to the specific branch: Should that level continue to be up to company command or should cadets obtain the required specific professional competencies to command platoon-level units?

In the latter case, the Spanish Army would need to convene lieutenants, prior to their promotion to the rank of captain, to attend a currently nonexisting educational program to facilitate the acquisition of the specific competencies required at company level.

The answer to this question is important for two main reasons. First, as stated above, the Spanish Army precommissioning officers’ curriculum is very dense due to the demanding professional competencies to be achieved by cadets; reducing the level of specific competencies would alleviate the existing high work load cadets have. Second, there is no educational program to prepare or complete the preparation of lieutenants to command a company (which happens about five years after being commissioned) to update them immediately prior to command a company.

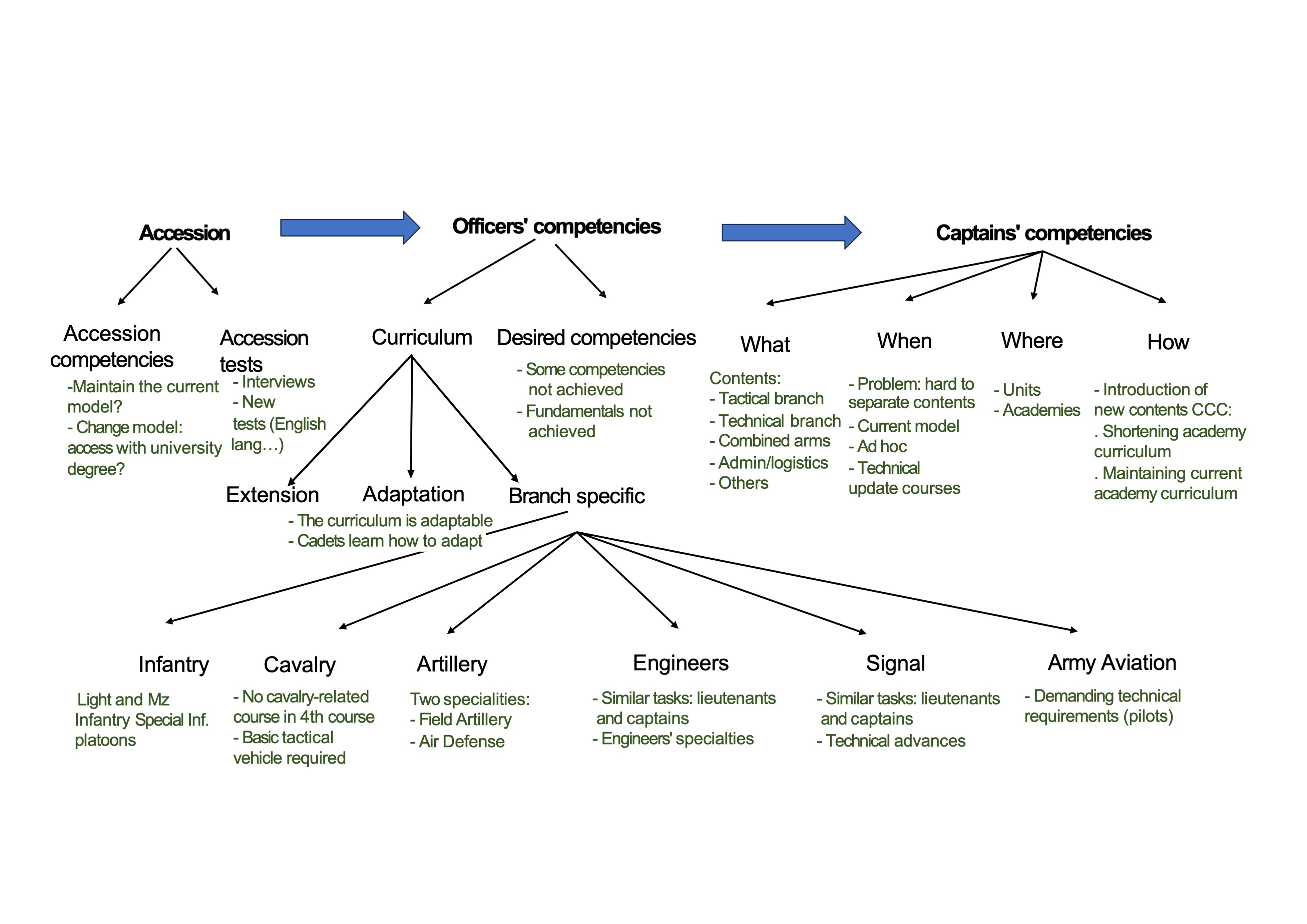

To answer the research question, the authors built a qualitative process of interviews with the six Spanish Army branch academies’ directors. These interviews were executed in person with each of the directors and consisted of a brief introduction about the research question and project. Once they conducted the interviews with the Spanish Army academies’ directors, they processed this information and built a category tree.

Figure 1. Spanish Army academy director’s category tree

Source: courtesy of the authors, adapted by MCUP.

The author’s observed that the current AGM’s accession process for cadets deeply impacts its educational model from the point of view of the required admission initial competencies: Should the Spanish model maintain the current accession model, or should it shift to one in which a university degree is already an access requirement?

There could also be other requirements that would need to be revised to facilitate cadets’ work load reduction: for instance, cadets could be required to have a more robust English language proficiency. Another example is to introduce interviews that might serve as a filter of personality attributes, motivation, behaviors, or some desired skills.

Conversely, should the university degree that is currently studied as part of the curriculum be diversified (i.e., introducing additional degrees than an engineering degree)? If affirmative, the variety of cadets would also change significantly, widening the spectrum of their possible backgrounds and likely raising the average intellectual level of the group of admitted cadets.

These ideas were mentioned by the infantry director, who said that it might be possible to proceed with an improved AGM accession process so that certain requirements be reinforced prior to getting to the AGM (e.g., English language proficiency, personal interviews to detect aspects of personality with more affinity to the profession of arms, and others). The Artillery Academy director stated that the curriculum is too dense in artillery since it has two separate specialties: field artillery and air defense. For this reason, the director consider that perhaps the best model would be a drastically different educational model in which a university degree would be one of the requirements to be admitted; consequently, the curriculum would be quite different.

As for officers’ competencies, during the interviews there was general agreement about the perception that the current educational model is too dense, and cadets face an immense working load. It was generally admitted that there are competencies that could not be achieved in a timely manner by cadets during their educational process.

The interview with the CUD director and deputy director highlighted the main problem of the current educational model in that the curriculum for officers is rather dense: “despite this fact, the current relative success in the annual number of commissioned officers can be explained due to a very demanding selection and access process that still provides the AGM with a highly qualified cadet. By and large, the total of 333 European Credit Transfer System (ECTS) together with the 52 military training weeks (equivalent to more than one academic year) is dense and demanding to be conducted in five years.”

This is one of the main reasons why the existing curriculum is under reform. This reform will facilitate curriculum contents updates. From the point of view of the CUD deputy director, “the military profession is unique because it is one of the most regulated of the existing professions and more prestige should be recognized by the civil society; for example, linking some steps in the officers’ trajectory with the obtention of university titles (master or doctorate). However, the overabundance of current curriculum contents implies such a demanding working load for cadets that the mentioned linkage, at least at cadet level would be very difficult to reach.” For example, within the current model it might be possible for cadets to earn a university degree but also a master’s degree. However, cadets have found it very difficult to achieve enough intellectual maturity to complete a master’s research project, which is amplified by the cadets’ high workload and lack of operational experience. Consequently, it would make more sense for officers to get a master’s degree in a more advanced moment of their career.

The Infantry Academy director recognized that some curricula (e.g., technical courses) should not be taught at the currently level in the Infantry Academy: “Perhaps, the part of the curriculum that is responsibility of the Infantry Academy could be more (or better) focused on those contents closer related to platoon leader responsibilities, while it seems that combined arms combat is neither sufficiently trained nor appropriately implemented according to infantry training needs.”

The Army Aviation Academy director stated that this branch has a differential element with respect to the other branches: “All Army Aviation officers are required to obtain their flight qualification, which means an additional period of 15 months (6 months more than other branches). This is strictly necessary and, compared to other branches requirements, it implies a limitation of time for contents related to general competencies.”

In their view, the Spanish Army officer educational model should be better focused on the fundamentals of the military profession. It should include the minimum military technics required to learn those fundamentals and how to think and adapt to the operational environment changes. A four-to-five-year academic program should make it unnecessary to update officers in military academies after four or five years of being commissioned: “Lieutenants must have acquired a deep capacity of adaptation and be ready to apply military fundamentals to adapt tactics to future wars. Cadets should not be receiving too many details about current tactics, technics, and procedures but the necessary fundamentals to identify what changes are to be implemented; in order words, they need to learn how to think or how to adapt tactics, technics, and procedures according to tendencies changes.”

The Cavalry Academy director also concurred that the curriculum is too dense and, in the case of branches such as cavalry, the university degree lacks any cavalry-specific coursework (in the fourth academic year) as it is the case of other branches such as artillery or signal. That means that cadets have a very demanding working load in this academy.

The changing operational environment proves that much of the curriculum becomes obsolete very rapidly. That is why one of the key features of the ongoing curriculum reform is to increase its adaptation capacity. The AGM director highlighted that, in view of the characteristics and culture of the Spanish Army, the current Spanish Army officer educational model, far from being bad, has one important strength: “Its capacity of adaptation, which is a key for both, the Spanish Army and the AGM. This capacity is provided by the current educational model due to different facts as, for example, the current rotation of military teachers at the AGM, coming from all Army units; it strongly facilitates the introduction of the brand-new tactics, techniques, and procedures in the AGM in an almost casual way.”

The AGM director stressed the idea that, by means of the current revision of the existing precommissioning officers’ curriculum, the Spanish Army is trying to reinforce its capacity of adaptation: “the educational model must be ready to be rapidly updated by the Army.” This is how this model is being adapted to the changing future operational environment despite real-life circumstances in which resources allocated to military education are limited: “The truth is that there might be several additional reforms that would improve our educational model; for example, a wider diversification of the university degrees studied in the AGM would probably enrich the quality of our officers as a group; a redefined set of tests for cadets’ accession would also contribute to it. But again, the existing shortage of manning and other resources for implementing this kind of reforms constitutes a serious obstacle.”

The CUD deputy director stated that “the virtue of the ongoing revision of the existing precommissioning officer’s curriculum is that professional competencies or learning results to be achieved remain its cornerstone. Learning results constitute the reference for all curriculum contents; this way, contents will be easier to be updated or changed when needed.”

However, with regard to the curriculum, there are inevitably different perceptions of the path forward depending on the branch academy because a significant part of the curriculum is branch related.

From the point of view of the Infantry Academy director, there is an important fact related to the existence of several types of infantry platoons operating at the battalion level. This implies that cadets need to receive a wider variety of courses related to two echelons above platoon, up to battalion level. This fact complicates the information cadets need to learn.

The Cavalry Academy director stated that cavalry tactical and technical courses are a function of the existing training materials: “This academy should be provided with a basic tactical vehicle with balanced capacities to perform cavalry maneuvers in a way that cadets learn the fundamentals. Afterward, once assigned to their units as lieutenants, they would need to be updated with courses related to the existing tactical vehicle in those units.” This way, there is a significant part of the curriculum that might be shortened in a similar way to the Army Aviation Academy case.

The Artillery Academy director elaborated on the fact that “the available time for Artillery cadets to achieve their professional competencies is too short considering that, in the Spanish Army, artillery is currently covering what in other armies are two different branches: Field Artillery and Air Defense.” This may be the most important obstacle to the Artillery Academy’s mission of preparing officers. The unification under a single branch (artillery) of field artillery and air defense in the Spanish Army would facilitate personnel management but also complicates officers’ preparation and talent management. This has an important impact on the Artillery Academy.

Regarding professional competencies, in the artillery director’s opinion, it would be very difficult to separate artillery professional competencies at the lieutenant level from those at the captain level from the tactical and technical point of view. They consider that “right now, the artillery part of the curriculum is appropriate since each course is scrutinized in relation with its probable usefulness in lieutenant assignments; that is to say, courses are very well connected with the desired professional competencies.”

During the interview with the Engineering Academy director, they first highlighted that this academy takes care of two different branchesengineering and signaleach with its own peculiarities, although both are separate branches compared with field artillery and air defense in artillery.

In the case of Signal Branch, its technological profile is crucial and requires continuous update: “For the Army Signal Branch, it is very difficult, from the tactical and technical point of view, to separate professional competencies at company level from platoon level, since captains and lieutenants perform a very similar role: both ranks act as signal advisors to their supported units and have similar command responsibilities when detached to provide signal support; that means that there is little qualitative difference between both ranks. However, from other points of view such as administrative, logistics and others, there are considerable differences in responsibility also for engineers.”

In the case of engineering officers, there are similarities with respect to the Signal Branch from the tactical and technical points of view since engineer officers have a similar role as advisors to their supported unit and in command of a unit detached to provide engineer support.

In the case of Army Aviation, professional competencies at lieutenant and captain levels differ similarly as in infantry and, in the opinion of the Army Aviation Academy director, “an appropriate educational model would make it unnecessary to update lieutenants to command a company.”

Most of the interviewed directors admitted that some specific competencies to perform as a captain are not always achieved by cadets when commissioned as officers. The AGM director recognized that it is difficult for cadets to achieve captain-level professional competencies during their five-year educational program. However, courses related to functions and responsibilities at company level are a requirement for lieutenants to correctly perform their role as platoon leaders. They also underlined the importance of the AGM leadership plan: “it provides cadets with the necessary opportunities to practice and achieve the expected professional competencies as officers. The AGM leadership plan is resulting very effective for it.”

The Infantry Academy director stated that “some of the cadets are not initiating their fifth course in the Infantry Academy, having previously consolidated the expected competencies in a proper way to face it and, consequently, it becomes a handicap for cadets which are under a lot of pressure during the period of time that cadets spend in this academy, also considering that both light and mechanized infantry are to be covered.”

Both the Infantry and Army Aviation Academy directors provided another important focal point in that the precommissioning officers curriculum is not appropriately covering some aspects of captain-level responsibility as, for example, is the case in administrative, logistic, or disciplinary areas; however, it is important to provide lieutenants with competencies at captain level since they frequently need to substitute them as company commanders. For the Infantry Academy director, “All in all, a reorganization of the current precommissioning officer’s curriculum should not imply reducing the working load to commission our cadets as officers; instead, a better redefinition of the contents should be conducted to better focus on professional competences at platoon level.”

The Cavalry Academy director stated that, “even if evaluation reports applied on lieutenants affirm that these officers have appropriately achieved the expected competencies, they also present some deficiencies; most of them are located in admin issues and in combined arms training as well.” These deficiencies were also identified by the Army Aviation Academy director.

The AGM director stated that, after being commissioned as lieutenants, professional competences at company level are usually completed by observation and operational experience obtained during their assignments as platoon leaders. “Spanish Army lieutenants really achieve captain professional competencies, observing and learning from good captains assigned in their units (assuming a kind of spontaneous mentorship role for lieutenants). These captains become the reference that lieutenants need for achieving those competencies: the way the Spanish Army ‘makes captains’ is by something so natural as the daily contact and interaction between lieutenants and those good and experienced captains.” Affirming this statement, the Infantry Academy director said that “there should be a course to support captains prior to command a company unit.”

However, the Army Aviation Academy director underlined the fact that these issues must be addressed in a different way than the need to technologically update officers: “technological requirements are not related to lieutenant or captain competency levels.”

For the Engineers Academy director, there is an important peculiarity: engineers must cover several different specialties that all lieutenants must know since they can be assigned to any engineers specialty. Further, “For both, engineers and signal branches, the speed of technical changes obliges to periodically provide with additional educational programs or courses for manning update. Additionally in the case of engineers, by means of professional military education courses, officers achieve further competencies required by some engineer specializations.”

From the point of view of the Artillery Academy director, there are other relevant aspects related to company command competencies (e.g., administrative, logistic, legal, and others) that right now are not sufficiently covered by the precommissioning officer’s curriculum; it would be necessary to articulate a course to prepare lieutenants to command a company. “The problem may appear in its implementation: sometimes this kind of activities is not successful due to different reasons. For instance, this course would imply to separate officers more time from their units. Or the fact that the current shortage of manning in the military academies constitutes a serious obstacle to implement new educational courses and others.”

For the Army Aviation Academy director, their lack of experience is what prevents lieutenants to achieve professional competencies as captains. Lieutenants are to complete their professional competencies through their units’ training programs; and updates needed to properly command a company would be achieved through these training programs as well. “Consequently, any curriculum should not include too many technical courses since they rapidly become obsolete. They should be more focused in other type of courses such as humanistic, which provide competencies that are valid in the long term. If those training programs are correctly implemented, it would be unnecessary to provide lieutenants with any educational program to achieve captain competencies, since the point is just to get the experience required to command a company.”

However, for the Cavalry Academy director, lieutenants would consolidate required professional competencies to command a company if they were prepared by means of a specific course aiming for that purpose. The CUD deputy director also affirmed that “although lieutenants are currently completing captain level competencies in their units, it seems ideal to support this important process by means of a regulated academic program at a later stage in their career, not during their precommissioning officers’ curriculum.”

Conclusions

There are two important points to be considered when designing an education and training program for cadets. The first is very evident: time and resources are limited. It implies that these programs need to be very well focused on the numerous, demanding officers’ professional competencies to be achieved: knowledge, skills, motivation, values, and personality.

The second is that these educational programs serve as the basis of an officer’s career-long educational process; courses to achieve specific competencies (knowledge and skills) will probably become obsolete in a relative short time along their career spectrum. Consequently, officers will need to update their knowledge and skills frequently.

As described above, the Spanish Army precommissioning officers’ educational model is very complete since it is designed so that cadets achieve not only the required general competencies to become army officers, but also those specific competencies (branch related) that potentially enable them to perform as captains. Consequently, once commissioned, Spanish Army lieutenants are prepared to command units at platoon and, theoretically, at company level as well; however, this educational program is very demanding for cadets due to the density of its coursework.

This model clearly contrasts with the U.S. Army Military Academy that, not including branch-related specific competencies, considers exclusively the rest of officers’ professional competencies. Of course, U.S. Army officers are educated and trained in branch-related specific competencies, but this happens once they are commissioned as first lieutenants by means of the BOLC-B. This course is exclusively focused on a second lieutenants’ level of professional competencies and not the captains’ level. As such, the U.S. Army model has a significant advantage: it mainly provides cadets with long-lasting general competencies, which do not change much along a military career, while it leaves branch-related specific competencies to be achieved chronologically closer to the professional moment they are required.

Can the Spanish Army model be improved?

First, it might be convenient to reduce the existing number of curriculum courses, those that are not strictly necessary, to facilitate the consolidation of the prevailing ones. For instance, this can be attained by modifying current admission initial competencies. For example, English language proficiency standards to access the AGM might be raised to facilitate achieving English language officers’ requirements. It might also be important to introduce a set of interviews among access requirements to work as a filter of personality to reduce the number of cadets advancing without appropriate motivation, values, or personality.

In general, the authors suggest that military educators learn from the past, including the academic curriculum courses (2010–24). The fact that there was only one university degree (industrial engineering), which is mainly technical, constituted another difficulty. Its courses were demanding and, although some of its material was branch related, in some of them (mainly infantry and cavalry) this connection is less firm that in the others. A diversification of university degrees and or the creation of new ones (tailored to each branch) might mitigate this problem. This should be considered in future research.

Furthermore, courses particularly oriented to achieve specific competencies should also be reconsidered. In some cases, for instance like infantry, there are some courses that delve too deeply. In others, like cavalry, improving the existing training materials would facilitate the educational process. In the case of artillery, it is quite demanding to prepare officers in both field artillery and air defense, which in many other armies are separate branches.

But another important consideration that should be analyzed is the implications of leaving all captain-level specific competencies to be achieved at a later moment in the officer career. Theoretically, by doing so, the number of academic curriculum courses could be reduced. However, it seems that this is not easily accomplished in some of the army branches, mainly in engineers, communications, and artillery.

How can this change be implemented? The U.S. Army model provides an interesting reference point. By means of the CCC (about six months long), U.S. Army lieutenants achieve captains’-level competencies. This course of action presents at least four important advantages: officers have previously acquired an important professional experience (much more solid than cadets’ prior to being commissioned). This professional experience is also shared by all lieutenants during the CCC and they learn from each another. As cadets, this is not possible due to the lack of experience. Second, all courses that captains need are more up to date than those offered several years before during the academy curriculum. Also, combined arms courses and other generic courses such as administration and logistics are easier to be assimilated by experienced lieutenants than by cadets.

One inconvenient fact that this model highlights from the institutional point of view is the need to create a new educational activity and to require all lieutenants to pass it, with the consequent impact for army units. However, if captain-level competencies and related courses are eliminated from the existing academic curriculum, it could be possible to reduce its duration. This is also the case of the U.S. Army model: U.S. Army cadets need four-and-a-half years to become a second lieutenant. The duration of this new course (similar to the U.S. Army CCC) could be accompanied by an equivalent reduction of the academic curriculum.

However, there is a significant increase in responsibilities and competencies when assuming a company command compared to commanding a platoon. Considering the difficulties that the current operational environment presents to company commanders and the complexity that commanding a company implies, promotion to this rank should be accompanied by an institutional educational activity. Leaving it exclusively to operational experience by lieutenants in their units, as it is currently the case in the Spanish Army, is also acceptable but the risk of not achieving the required competencies by all lieutenants may be significantly higher.

As a result of this research, when educating and training cadets to become officers, more focus should be on officers’ general competencies to achieve better results. Certainly, the focus should be on fundamentals and principles rather than on tactics, technics, and procedures that vary over time. For this reason, most branch-related competencies and courses should be delayed and minimized in the academic curriculum as much as possible.

Endnotes

Rafael Martinez, Quiénes son y qué piensan los futuros oficiales y suboficiales del Ejército español [Who are the future officers and noncommissioned officers of the Spanish Army and what do they think?] (Barcelona, Spain: Barcelona Centre for International Affairs, CIDOB, 2004), 32.

Orden DEF/1158/2010 [General guidelines for the curricula of general, specific, and technical military training] (Ministry of Defense, 7 May 2010).

Directiva 02/08, Plan de Acción de Personal (PAP) (2014).

About the Authors

Colonel Enrique Gaitán Monje, PhD, currently serves in the Instituto Universitario General Gutiérrez Mellado, is a Staff College graduate. He has served in tactical positions in field artillery and air defense units, as well as an instructor at the General Military Academy (GMA). He later held posts in national and international staffs. He served as deputy director and dean of studies at the GMA and as Spanish liaison officer to the U.S. Army’s Training and Doctrine Command. He has participated in missions in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Afghanistan. He holds a PhD in international security and a master’s in peace, security, and defense from Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia, Madrid.

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9264-6789

Andrés de Castro is an associate professor of international relations and security studies at Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia. He has almost a hundred academic publications on international relations theory, area studies, intelligence, and professional military education. He has held several international academic positions in several countries, and he has senior academic management experience as head of the department, director of PhD studies, director of masters programs, and vice director of the research center for the Spanish Ministry of Defense with Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia.

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3794-7703