John T. Kuehn, PhD

14 May 2024

https://doi.org/10.36304/ExpwMCUP.2024.03

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: The U.S. Navy is currently at war on behalf of the United States and its partners in the seas off the coast of Yemen. The nation’s earlier Quasi-War with France (1798–1801) shares many of the same attributes with this current conflict. Both involve attacks on neutral shipping and thereby the vital interests of the United States, and both were unprovoked, as the shipping under attack has not violated any international laws or sovereignty. The current conflict traces its origins to both the long-running Yemeni Civil War as well as the more recent Israel-Hamas war. It offers both insight and opportunity for the United States and its maritime partners. Insights reflect key issues involved in protecting maritime shipping in the current environment of high-technology missiles and unmanned aerial systems (UAS, a.k.a. drones), as well as in examining older concepts of sea control such as convoys. Finally, it offers the United States a graphic reminder of the importance of sea power and why the nation has a navy in the first place.

Keywords: Quasi-War, sea power, U.S. Navy, Yemen, Houthis, Israel, Hamas, Gaza, convoys, missiles, UAS, drones

The United States, with no aggressive purpose, but merely to sustain avowed policies, for which her people are ready to fight, although unwilling to prepare, needs a navy both numerous and efficient, even if no merchant vessel ever again flies the United States flag.

~ Alfred Thayer Mahan, 1911[1]

The United States has come full circle during a cycle of nearly two and a half centuries. Just as it fought what later historians called a “Quasi-War” with France over the free flow of commerce at sea in 1798–1801—its first war as a young republic after the ratification of the U.S. Constitution in 1788—it is today embroiled in a similar conflict with the Iranian-backed Houthi regime in the waters of the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden that border the critical Bab el-Mandeb Strait.[2] The term quasi-war is a historical construct, but it can be interpreted to include wars in which armies are not involved on both sides. Current U.S. combat operations off Yemen fit this description.

The most recent attacks in this new naval Quasi-War are ongoing as of this article’s publication.[3] Unlike the Quasi-War of 1798–1801, most Americans have little awareness that their nation is at war in the waters of the Gulf of Aden and the southern Red Sea. This is profoundly unsettling but not unsurprising, as the sea blindness of most Americans is practically an established fact.[4] Butch Bracknell and James Kraska define sea blindness as “an inability to appreciate the central role the oceans and naval power have played in securing our strategic security and economic prosperity.”[5] However, with mounting public interest, the present Quasi-War in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden might be the key forcing function that finally begins to right the ship known as the U.S. Navy and get it back on track after years of fiscal, strategic, and political neglect.

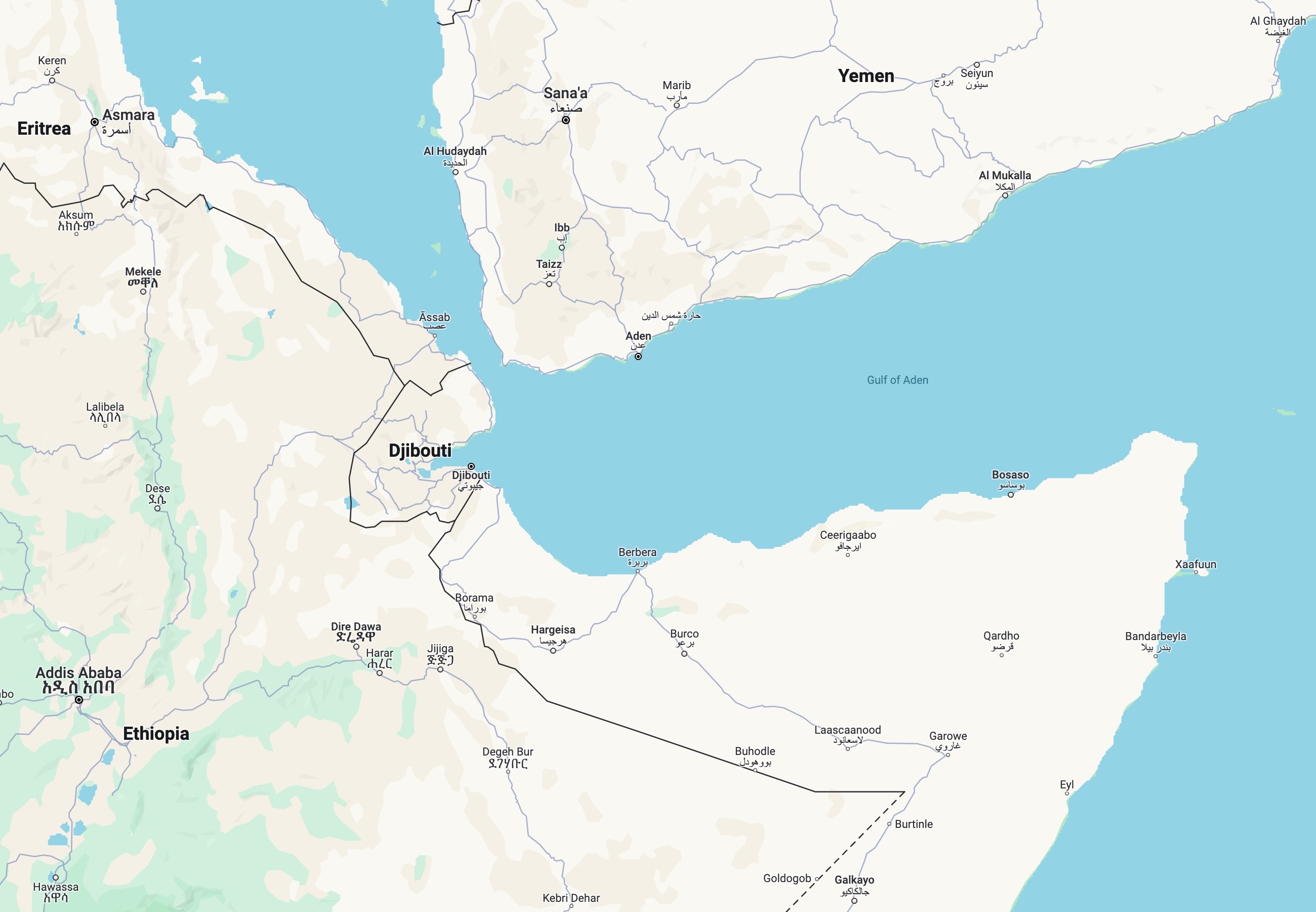

Figure 1. Bab el-Mandeb Strait

Source: courtesy of Google Maps, adapted by MCUP.

The First Quasi-War

For the purposes of this article’s argument, a short history lesson on the Quasi-War of 1798–1801 for those unfamiliar with the United States’ first overseas war is useful here. Despite the U.S. Constitution’s mandate in Article 1, Section 8, to “provide and maintain a Navy” in 1787, it was not until 1794 that the U.S. Navy was “reborn” with the establishment of the U.S. Navy Department due to depredations against U.S. maritime trade, principally by the Dey of Algiers.[6] The dey was the de facto ruler of one of what were collectively known as the Barbary States that stretched along the southern Mediterranean coast of North Africa along a key sea line of communication for trade. Even with this provocation, the first of Navy’s original six frigates—USS United States—was not commissioned until 1797.[7]

Simultaneously, the administration of newly elected U.S. president John Adams struggled against continuing criticism for what was regarded as the president’s lackluster efforts to protect U.S. maritime trade—especially against the French, who were now targeting neutral U.S. shipping in response to Jay’s Treaty between the United States and Great Britain. Establishing a trend that eventually became a feature of most U.S. conflicts, war was not formally declared.[8] But war it was, with the first engagement occurring when a French privateer boldly entered Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, and seized an American merchant ship in the spring of 1798. The first naval tactical victory occurred not long after, when U.S. Navy captain Stephen Decatur Jr. in the sloop-of-war USS Delaware (1798) defeated the French privateer La Croyable (1798). The most famous engagement occurred when U.S. Navy captain Thomas Truxtun in the frigate USS Constellation (1797) defeated the French frigate L’Insurgente (1793) in open battle on 9 February 1799.[9]

The war continued in this tit-for-tat fashion until French general Napoléon Bonaparte seized control of the French government and ordered his foreign minister, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, to bring the war to a close with a de jure recognition of U.S. neutral shipping rights in the Treaty of Mortfontaine in 1800. This action paved the way for Napoléon to eventually negotiate the sale of the Louisiana territory to the United States after the Treaty of Amiens was signed in 1802.[10] However, this result was due in part to the United States possessing an armed and active naval fleet that was prepared to defend neutral shipping rights and sea lanes, however quixotic that might have seemed at the time for the young republic.

Yemen and the Origins of a New Quasi-War

Today, Yemen sits astride the critical geography dominating one of the major sea lanes and choke points that connects the Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf with the Suez Canal and Mediterranean markets. The origins of the United States’ Quasi-War with Yemen date back to the decolonization movement (a.k.a. postcolonialism) that began after the end of World War II.[11]

Yemen’s contemporary problems have their roots in the creation of two Yemeni states during the decolonization period, which saw much of the present nation divided along Cold War lines, with a Western-friendly government in the Yemen Arab Republic (North Yemen) and a pro-Soviet Union Communist regime in the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (South Yemen).[12] The two sides also divided along religious and ethnic lines, with the Shia Houthis in the north with their capital at Sana’a and the secular Sunni Arabs in the south and east with their capital at Aden.[13] The collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s did nothing to alleviate these fundamental fractures in what became a united Republic of Yemen in 1990. This political unity never had a chance, and civil war broke out in the new republic not long afterward, continuing until 1999, when Ali Abdullah Saleh, the pro-Western, pro-Houthi leader of North Yemen became president of the united Republic of Yemen. Additionally, Yemen also faced external conflicts over its border with Saudi Arabia and over islands in the Red Sea with Eritrea.[14]

Yemen subsequently became entangled in the post-Cold War events that eventually became part of the Global War on Terrorism. Some identify the Islamic terrorist group al-Qaeda’s bombing of the U.S. Navy guided-missile destroyer USS Cole (DDG 67) in 2000 in Aden harbor as the real beginning of the conflict, not the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center in New York City and the Pentagon outside Washington, DC.[15] In short, Yemen has always been a problem, with the threat evolving from extreme Sunni-Wahhabi attacks against the West and its interests (especially Israel) to an Iranian-backed regime in Sana’a (see figure 1). In terms of regional geopolitics, Yemen is a fault line, both within the Arabian Peninsula as well as between the West, as represented by Israel and the United States, and Iran.[16]

Nonetheless, Yemen attained a degree of political stability under President Saleh until his ouster during the Arab Spring in 2012, although problems with the Houthis began as early as 2004. It was Saleh’s ouster that led to an outbreak of full-scale civil war again in Yemen in 2014.[17] A Saudi Arabia-led intervention in this civil war in 2015, in opposition to the rebel Houthis, led to a series of attacks both on land and at sea against what the Houthis determined were targets that could hurt the Saudis and their U.S. partners. This included a series of attacks on U.S. warships in the Red Sea. In 2016, the guided-missile destroyer USS Mason (DDG 87) intercepted two Houthi missiles fired off the coast of Yemen in the Red Sea with a combination of RIM-66 Standard MR (SM-2) surface-to-air missiles (SAM) and new-generation RIM-7 Sea Sparrow SAMs. This attack should be regarded as the beginning of the current Quasi-War, although its political purpose was aimed more at Saudi Arabia than is the case today at Israel and the United States. On 3 March 2020, as if to remind the world that the conflict remained ongoing, remote-controlled skiffs bearing military-grade explosives attempted to attack the Saudi-flagged tanker Gladiolus (1998) approximately 165 kilometers off the Yemeni coast.[18]

The present Israel-Hamas war, which began with Hamas’s surprise attack on Israel in October 2023 and provoked the subsequent Israeli invasion of Gaza to eradicate Hamas, renewed the focus of Houthi-Iranian ire against Israel and became the new casus belli in this ongoing war on the shipping lanes. When the war began, the Houthi regime in Sana’a immediately announced its support of Hamas and began attacks that same month. On 19 October, the guided-missile destroyer USS Carney (DDG 64) employed its SM-2 missiles to down three land-attack missiles (possibly the Iranian-produced Quds-2 cruise missile) launched from Yemen against Israel, as well as a number of drones. The United States subsequently committed itself to defending Israel against Houthi attacks.[19]

Since these incidents, attacks on international shipping, whether bound for Israel or not, have been more or less constant. On 26–27 November, the Mason responded to another attack and as it proceeded to the area of the Israeli tanker MV Central Park in the Gulf of Aden and detected two antiship ballistic missiles (ASBM) launched from Yemen. These missiles impacted the sea three kilometers from the target. This was the first known use of ASBMs in naval combat.[20] On 3 December, the Carney was in action again, actively defending shipping as it transited north and shooting down three drones during an ASBM attack on a northbound commercial ship. Mason was again in action on 6 December, shooting down a drone. Subsequent attacks and orders to northbound vessels to change course continued until an apparent escalation by the Houthis on 10 December.[21] On that day, the Carney intercepted and destroyed 22 Houthi arial threats, a mix of cruise missiles and drones, during a series of attacks against various commercial vessels transiting the Red Sea after passing through the Bab el-Mandeb Strait. This was the first of a series of “drone swarm” attacks, some of which may have targeted the Carney, inadvertently or otherwise. Since ASCM radar homers cannot distinguish warships from commercial ships, they may have automatically decided to home in on the Carney, which presents a large radar target to an undiscriminating missile seeker.[22] The very next day, a missile attack was launched against the German-owned ship MV Al Jasrah. The Mason shot down another drone two days later.[23]

Another drone swarm attack occurred on 16 December, with the Carney shooting down 14 drones in one day after Houthi missiles and drones were launched against several ships. The Mason answered the mayday call of one of these ships and rendered aid. British Royal Navy warships have also engaged some of the attackers and reputedly shot down a drone in December. These attacks led to calls for the formation of an international task force to protect shipping, as various shipping lines such as the Danish company Maersk suspended northbound transits. It must be emphasized that the bulk of this shipping is not bound for Israel, though both Iran and the Houthis cynically claim that they are only attacking ships that are.[24]

The Way Ahead: Operations Prosperity Guardian and Poseidon Archer

The naval Quasi-War in the Red Sea continues to evolve. It has led to the formation of a maritime task force and the assignment of an operational name to what has been essentially and ad hoc protection-of-shipping campaign. According to the most recent press releases, the participants of this task force will be the navies of the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Spain, Norway, and Bahrain. Bahrain is the location of the headquarters of the U.S. Navy’s Fifth Fleet, whose area of operations includes the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, the Red Sea, and the Gulf Aden. One encouraging aspect of this news is that the operation—and, consequently, the Quasi-War with Yemen’s (and Iran’s) Houthi regime—officially has a name: Operation Prosperity Guardian. Normally, the United States reserves these kinds of names only for long-term operations. Larger naval forces, to include U.S. Navy carrier strike groups (CSG), have also converged on the region. In the meantime, concerns about the rising prices of oil and other commodities serve as significant driving factors. Getting the attention of American audiences all too often requires an attack on their pocketbooks, just as it did during the undeclared U.S. naval war with Iran in the 1980s over Iran’s attacks on shipping, which led to the reflagging of Kuwaiti tankers (Operation Earnest Will, 1987–88).[25]

The arrival of the USS Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN 69) CSG in the region introduced carrier aircraft into Operation Prosperity Guardian and resulted in the first shootdown of drones by McDonnell Douglas F/A-18 Hornet fighter aircraft on 26 December. Defense became limited offense on 11 January 2024, when “the U.S. and British militaries bombed scores of sites used by the Houthis in Yemen, a massive retaliatory strike using warship- and submarine-launched Tomahawk missiles and fighter jets. . . . The U.S. Air Force’s Mideast command said it struck more than 60 targets at 16 sites, including ‘command-and-control nodes, munitions depots, launching systems, production facilities and air defense radar systems’.”[26] This event marked the beginning of Operation Poseidon Archer, formally announced by U.S. Central Command in late January 2024. Both Operations Prosperity Guardian and Poseidon Archer continue today. Five U.S. destroyers have seen combat involving nearly 40 attacks. Additionally, the Eisenhower CSG along with coalition surface and air forces have continued to degrade the enemy’s shore launching facilities for drones, ASCMs, and ASBMs.[27]

The Way Ahead?

Many challenges remain for Operations Prosperity Guardian and Poseidon Archer and the maritime coalition prosecuting them. There are no major warship maintenance facilities nearby, though U.S. ships might be allowed to dock in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia (U.S. aircraft carriers docked there during Operation Desert Shield in 1990–91).[28] However, the ongoing Israel-Hamas war in Gaza complicates such a move. The principal difficulty will ultimately be maintaining a robust on-station presence and providing convoy escorts. The possibility of convoying has already been brought up and remains an option, with coalition warships serving as a screen between unescorted merchant ships and Yemen’s long coastline from the Gulf of Aden, through the Bad el-Mandeb Strait, and into the Red Sea. It is a route hundreds of kilometers in length.

The key problem with the convoy option involves the mechanics of forming convoys as well as getting ships to agree to rendezvous in a particular area or port, to use a common communications system other than international guard frequencies, and to agree on other tactical coordination issues. Convoys cannot be improvised, as experiences during World Wars I and II and Operation Ernest Will have taught.[29] Moreover, while in antisubmarine convoys there is strength in numbers, this is not necessarily true when missiles and drones are the major threats. Escorting warships offer a convoy protection, but they also provide a large target set for an attacker. This means that present-day convoys would probably need even more escorts than were found in a standard convoy during World War II. A World War II-era transatlantic convoy of 30–40 ships was often escorted by far fewer escorts, often less than 10. On the plus side, a contemporary super-size container ship has the carrying capacity of 20 World War II-era Liberty ships. Given the present-day threats of drones, ASCMs, and ASBMs, a convoy’s main defense will be its air defenses, centered around its escorts’ antimissile/antidrone systems. Both higher numbers of escorts and a robust rearming system will be required to wage a protracted conflict, which is exactly what this Quasi-War has become. The bottom line is that unlike in World War II, there is no forcing function today to form commercial ship convoys.[30] If convoys could be demonstrated to be more effective than the current system of defense, then perhaps insurers would lower rates. The fact that convoying has not yet been formally employed is evidence of just how difficult such a response might be or that analysts have done the math and decided that convoying is not efficacious enough to justify the efforts needed to implement it.

This is the ideal time for U.S. Navy leadership, especially the chief of naval operations, Admiral Lisa M. Franchetti, to make the case (again) for additional frigates and cruisers to be fast-tracked for production to assist in the ongoing conflict. Another action that might be taken is to be more forceful in testimony to Congress and advice given up the chain of command to the U.S. secretary of defense and the president. It is worth cataloging the Carney’s current air defense armament, which is presumably similar to that of its fellow Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer Mason. Carney is armed with a wide array of air defense systems, including a 5-inch/54-caliber Mark 45 gun optimized to shoot at air targets, a RIM-116 Rolling Airframe Missile (RAM), and the Vulcan Phalanx close-in weapons systems (CWIS). The destroyer also has the longer-range guided SM-2 missiles, as well as the capability for ballistic missile defense if needed. However, even with all this armament, both the Carney and other Navy destroyers must be starting to run low on ordinance. This highlights a key logistical requirement that this sort of high-intensity maritime combat brings with it.[31]

The ramifications of an ongoing naval war in the Middle East are still poorly understood by the American public. Despite the intent to focus U.S. maritime power in the Western Pacific and Eastern Indian Oceans, this new Quasi-War has changed the strategic dynamic. Responding with an “operations normal” approach is not a strategy—rather, it is more akin to putting one’s head in the sand. Only leadership in the U.S. Navy, the U.S. Marine Corps, and the highest levels of the U.S. government and support from the United States’ maritime coalition partners can enable the United States to continue to protect these vital shipping lanes, but not at the expense of creating another “hollow fleet” such as that which existed in the 1970s.[32] Congress should put more money into warship maintenance and construction infrastructure, not only to support Operation Prosperity Guardian but also to fund the long-term needs of the U.S. maritime community. Ironically, not being aware that one is already at war makes one even more unready for other crises and wars that might occur elsewhere. The key constituency remains the American people. The public in the United States must rouse itself to the reality that their country is at war and that the principal military Service doing the heavy-lifting is their long-neglected Navy.

About the Author

John T. Kuehn serves a professor of military history at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College (CGSC) in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. He served as the Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King Visiting Professor of Maritime History at the U.S. Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island, in 2020–21. He retired from the U.S. Navy 2004 at the rank of commander after 23 years in uniform, serving as a naval flight officer flying land- and carrier-based aircraft. He has taught a variety of subjects including military history at CGSC since 2000. His books include Agents of Innovation: The General Board and the Design of the Fleet that Defeated the Japanese Navy (2008); Eyewitness Pacific Theater: Firsthand Accounts of the War in the Pacific from Pearl Harbor to the Atomic Bombs (2008), coauthored with D. M. Giangreco; A Military History of Japan: From the Age of the Samurai to the 21st Century (2014); Napoleonic Warfare: The Operational Art of the Great Campaigns (2015); America’s First General Staff: A Short History of the Rise and Fall of the General Board of the U.S. Navy, 1900–1950 (2017); and The 100 Worst Military Disasters (2020), coauthored with David Holden. He has published numerous articles and editorials and was awarded a Moncado Prize by the Society for Military History in 2011. His 2022 article “Zumwalt, Holloway, and the Soviet Navy Threat Leadership in a Time of Strategic, Social, and Cultural Change,” published in the Journal of Advanced Military Studies by Marine Corps University Press, received the Society for Military History’s 2023 Vandervort Prize. His latest book is Strategy in Crisis: The War in the Pacific, 1937–1945, published by Naval Institute Press in 2023.

https://orcid.org/0009-0002-0877-7589

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Marine Corps University, the U.S. Marine Corps, the Department of the Navy, or the U.S. government.

Endnotes

[1] As quoted in the modern adaptation, Alfred Thayer Mahan, Naval Strategy, Fleet Marine Force Reference Publication 12-32 (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, 1991), 447. Mahan almost certainly wrote this much earlier than 1911 because this book was compiled from his lectures in 1888, with very little new content added. See this discussion in Nicholas A. Lambert, The Neptune Factor: Alfred Thayer Mahan and the Concept of Sea Power (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2024), 309–14.

[2] For more on the Quasi-War between the United States and France, see Robert W. Love Jr., History of the U.S. Navy, vol. 1, 1775–1941 (Harrisonburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1992), 57–71.

[3] For the latest milestone of events in this conflict, see Jonathan Lehrfeld, Diana Stancy, and Geoff Ziezulewicz, “All the Houthi-U.S. Navy Incidents in the Middle East (that We Know of),” Military Times, 12 February 2024. See also Nicholas Slayton, “Navy Destroyer Shoots Down 14 Drones as U.S. Mulls Red Sea Task Force,” Task and Purpose, 16 December 2023; and Love, History of the U.S. Navy, 57–60.

[4] For a definition of sea blindness, see “Sea Blindness,” Maritime Security Forum, 5 February 2023. For arguments that sea blindness is currently widespread in the United States, see Butch Bracknell and James Kraska, “Ending America’s ‘Sea Blindness’,” New Atlanticist (blog), Atlantic Council, 6 December 2010.

[5] Bracknell and James, “Ending America’s ‘Sea Blindness’.”

[6] U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 13.

[7] Love, History of the U.S. Navy, 52.

[8] Treaty of Amity Commerce and Navigation, between His Britannic Majesty; and the United States of America, U.S.-UK, 19 November 1794.

[9] Love, History of the U.S. Navy, 57–61.

[10] Love, History of the U.S. Navy, 70–71.

[11] For a recent work on decolonization, see Jeffrey James Byrne, Mecca of Revolution: Algeria, Decolonization and the Third World Order (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016). The term postcolonialism is also used and often refers to geopolitical trends that have occurred after the bulk of decolonization took place during the Cold War.

[12] The People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen was the only Communist state to exist in the Arab world. The Soviet Union intervened in a civil war there in 1986 with advisors and warplanes to ensure the survival of the Communist regime. Jonathan M. House, A Military History of the Cold War, 1962–1991 (Norman: Oklahoma University Press, 2020), 297–98.

[13] Mark N. Katz, “Civil Conflict in South Yemen,” Middle East Review (Fall 1986): 7–13.

[14] “A Short History of Yemen,” Yemeni Community Association, accessed 19 December 2023.

[15] Richard A. Clarke, Against All Enemies: Inside America’s War on Terror (New York: Free Press, 2004), 189–98.

[16] “Al Qaeda Associates Charged in Attack on USS Cole, Attempted Attack on Another U.S. Naval Vessel,” press release, U.S. Department of Justice, 15 May 2003.

[17] Faisal Edroos, “Yemen: Who Was Ali Abdullah Saleh?,” Al Jazeera, 5 December 2017.

[18] Seth G. Jones et al., “The Iranian and Houthi War against Saudi Arabia,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, 21 December 2021.

[19] Sam Lagrone, “U.S. Destroyer Used SM-2s to Down 3 Land Attack Missiles Launched from Yemen, Says Pentagon,” U.S. Naval Institute News, 19 October 2023.

[20] Lehrfeld, Stancy, and Ziezulewicz, “All the Houthi-U.S. Navy Incidents in the Middle East (that We Know of).”

[21] Diana Stancy, “USS Mason Takes Down Drone for at Least the Second Time This Month,” Navy Times, 13 December 2023; George Petras and Janet Loehrke, “U.S. Navy Ship Attacked in Red Sea by Houthi Militants: How It Unfolded,” USA Today, 5 December 2023; and Aleks Phillips, “Red Sea Map Shows Where Attacks on Vessels Have Taken Place,” Newsweek, 18 December 2023.

[22] Dylan Malyasov, “U.S. Navy Destroyer Intercepts 22 Houthi Aerial Threats in Red Sea,” Defence Blog, 10 December 2023.

[23] Phillips, “Red Sea Map Shows Where Attacks on Vessels Have Taken Place”; and Stancy, “USS Mason Takes Down Drone for at Least the Second Time This Month.”

[24] Paul McLeary, “Houthis Launch More Attacks in Red Sea as U.S. Warships Head to Region,” Politico, 16 December 2023; and Slayton, “Navy Destroyer Shoots Down 14 Drones as U.S. Mulls Red Sea Task Force.”

[25] Nick Edser, “Fears of Higher Oil Prices after Red Sea Attacks,” BBC, 19 December 2023. See also David Crist, The Twilight War: The Secret History of America’s Thirty-Year Conflict with Iran (New York: Penguin, 2013), chaps. 17 and 18. Crist also uses the term Quasi War to describe the relationship between the United States and Iran.

[26] Lehrfeld, Stancy, and Ziezulewicz, “All the Houthi-U.S. Navy Incidents in the Middle East (that We Know of).”

[27] Sabrina Singh, “Deputy Pentagon Press Secretary Sabrina Singh Holds a Press Briefing,” U.S. Department of Defense, 25 January 2024.

[28] The author was embarked on the aircraft carrier USS John F. Kennedy (CV 67) when it docked in Jeddah during Operation Desert Shield.

[30] Symonds, World War II at Sea, 107–13.

[31] Richard R. Burgess, “USS Carney’s Success Showed Value of Aegis, SM-2, VLS, Alert Crew,” Seapower, 24 October 2023.

[32] For more on the term hollow fleet, see John T. Kuehn, “Zumwalt, Holloway, and the Soviet Navy Threat: Leadership in a Time of Strategic, Social, and Cultural Change,” Journal of Advanced Military Studies 13, no. 2 (Fall 2022): 19–32, https://doi.org/10.21140/mcuj.20221302001.