Abstract: The People’s Republic of China (PRC) is at war with the world. Chief among the PRC’s weapons in its fight against the United States and many of its allies and partner nations are complex, unrelenting political warfare campaigns, often waged with difficult-to-recognize strategies, tactics, techniques, and procedures. This article will underscore the terms and definitions needed to understand PRC political warfare and offer a historical overview of the PRC’s development of its political warfare capabilities. A solid understanding of both subjects will help American institutions and citizens alike strengthen their ability to identify, deter, counter, and defeat the PRC political warfare threat.

Keywords: People’s Republic of China, PRC, political warfare, Chinese Communist Party, China Dream, Xi Jinping, united front, liaison work, active measures, sharp power, smart power, propaganda, three warfares, psychological warfare, public opinion/media warfare, cyber warfare, lawfare, People’s Liberation Army, PLA

Political warfare is not a new phenomenon. Its practice spans thousands of years, and it is not unique to the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Still, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is devilishly good at conducting its own particularly virulent form of it. The PRC version of political warfare poses more than a unique challenge. The Commandant of the Marine Corps, General David H. Berger, identified the PRC as “the long-term existential threat” to the United States.1 Central to that threat to the United States and its partners and allies is PRC political warfare. With this massive, well-financed capability, the PRC hopes to achieve victory over the United States without actually fighting a kinetic war.

In a report to Congress in May 2020, President Donald J. Trump highlighted some of the aspects of this political warfare threat: “China’s party-state controls the world’s most heavily resourced set of propaganda tools. Beijing communicates its narrative through state-run television, print, radio, and online organizations whose presence is proliferating in the United States and around the world. . . . Beyond the media, the CCP uses a range of actors to advance its interests in the United States and other open democracies. CCP United Front organizations and agents target businesses, universities, think tanks, scholars, journalists, and local, state, and Federal officials in the United States and around the world, attempting to influence discourse and restrict external influence inside the PRC.”2 Routinely, PRC political warfare undermines U.S. Marine Corps activities and U.S. national security globally.3

Failure to understand PRC political warfare and how to fight it may well lead to America’s strategic defeat before initiation of armed conflict and to operational defeat of U.S. military forces on the battlefield. However, the United States no longer has the capacity to compete and win on the political warfare battlefield, for that ability has atrophied in the nearly three decades following the collapse of the Soviet Union. America needs to rebuild its capacity to successfully identify, deter, counter, and defeat PRC political warfare on an urgent basis. Education about the PRC political warfare threat is a good place to start.

As a foundation for successfully identifying and combating PRC political warfare, it is important to understand definitions and terminology associated with it and its history. Study of this insidious threat is complicated by a dizzying array of terminology that governments and academics accord to political warfare-related activities. An overabundance of associated terms and definitions becomes counterproductive at a certain point. Further, it is crucial to understand the history of the CCP’s unique brand of political warfare, particularly its ancient foundations, Leninist underpinnings, and Maoist revisions that led to notable PRC successes in times of peace and war. Accordingly, this article provides a brief overview of these two topics to lay a foundation for further study of the PRC’s political warfare organizations and operations.

Definitions and Terminology

Prussian military strategist Carl von Clausewitz wrote that “war is the extension of politics by other means”; American diplomat George F. Kennan later postulated that political warfare is “an extension of armed conflict by other means.”4 Kennan is best known for his delineation of the Western grand strategy of “containment” of the Soviet Union during the Cold War, as explicated in his famous “Long Telegram” of 22 February 1946.5 Two years after proposing the ultimately successful policy of “containing” the Soviet Empire to end this totalitarian regime, Kennan drafted another memorandum entitled “The Inauguration of Organized Political Warfare.” His second landmark of strategic thinking makes the point, strikingly from a contemporary perspective, that

we have been handicapped . . . by a popular attachment to the concept of a basic difference between peace and war, by a tendency to view war as a sort of sporting context outside of all political context . . . and by a reluctance to recognise the realities of international relations, the perpetual rhythm of [struggle, in and out of war].6

He laid out the nature of the threat from the Soviet Union and defined political warfare as follows:

In broadest definition, political warfare is the employment of all the means at a nation’s command, short of war, to achieve its national objectives. Such operations are both overt and covert. They range from such overt actions as political alliances, economic measures . . . and “white” propaganda to such covert operations as clandestine support of “friendly” foreign elements, “black” psychological warfare and even encouragement of underground resistance in hostile states.7

This definition is as valid today as it was in 1948. However, the PRC’s version of political warfare has evolved in ways not fully understood in 1948, and new concepts and semantic battlegrounds have emerged. Accordingly, it is useful to examine more deeply key political warfare–related terms used in this article.

Words and definitions are, of course, crucially important, but at a certain point, the wide array of terms and definitions that are accorded to political warfare-related activities consume time, intellect, and energy better invested in actually fighting the political warfare battle. Below is a short list of the vast collection of terms that civilian and military leaders must comprehend in order to effectively confront and ultimately wage political warfare:

Table 1. Political warfare terms

|

assertive hegemony

|

fake news

|

information warfare

|

public opinion warfare

|

|

cyber warfare

|

false narratives

|

lawfare

|

sharp power

|

|

deception

|

gray zone operations

|

liaison work

|

soft power

|

|

dept diplomacy

|

hard power

|

malign influence

|

special measures

|

|

diplomacy

|

hybrid operations

|

psychological operations

|

subversion

|

|

disinformation

|

infiltration

|

public affairs

|

three warfares

|

|

engagement

|

influence operations

|

public diplomacy

|

united front

|

Source: compiled by the author.

Unless viewed holistically as part of a larger construct similar to the concept of combined-arms warfare and joint/combined operations, these terms are invariably addressed piecemeal in stove-piped fashion. Diplomats will generally focus on diplomacy, public diplomacy, and public affairs, while military officers will focus on information operations, psychological warfare, cyber operations, and public affairs. But there is little in the backgrounds or education of many current U.S. government officials that allow them to see these strategies and functions holistically as part of general political warfare and to fight this unique war in a combined-arms manner. The resultant fragmented approach to addressing these functions and strategies fatally subverts a nation’s ability to create the synergy required to confront PRC political warfare.

The key terms influence operations and political warfare overlap and are sometimes considered virtually interchangeable. There are various definitions from credible institutions for these terms, but unfortunately each definition varies somewhat from the other, obscuring conceptual clarity.

Accordingly, for the purposes of this article, the following definitions apply. Influence operations are those operations by the PRC designed to influence foreign government leaders, businesses and industries, academia, news media, and other influential individuals and key elites in a manner that benefits the PRC—often, but not always, at the expense of the self-interests of the countries at which the operations are directed. Influence operations provide strategies and tactics used in broader political warfare campaigns. Political warfare is an extension of armed conflict by other means and a critical component of PRC security strategy and foreign policy. PRC political warfare includes those operations that seek to influence the emotions, motives, objectives, reasoning, and behavior of foreign governments, organizations, groups, and individuals in a manner favorable to the PRC’s political-military-economic objectives, and which are generally conducted with hostile intent. PRC political warfare is all-encompassing: it is unrestricted warfare and a form of total war. It also includes use of active measures such as violence and other forms of coercive, destructive attacks.8

Weapons in the PRC’s political warfare arsenal of influence include actions such as co-opting institutions, organizations, and people through so-called “united fronts”; the use of law to undermine countries and institutions; and psychological operations. They also incorporate propaganda, diplomatic coercion, disinformation such as rumors and fake news, overt and covert media manipulation, active measures, hybrid warfare, espionage, and such soft power functions as public diplomacy, public affairs, public relations, and cultural affairs activities. Below is a brief overview of the primary PRC political warfare concepts and tools.

Unrestricted Warfare

The CCP conducts its political warfare activities under the rubric of unrestricted warfare, the underpinnings of which were published by two People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Air Force political warfare colonels in February 1999.9 In essence, the PLA officers wrote that unrestricted warfare “means that any methods can be prepared for use, information is everywhere, the battlefield is everywhere, and that any technology might be combined with any other technology” and that “the boundaries between war and non-war and between military and non-military affairs has systematically broken down.”10 They recommended that the PRC “use asymmetric warfare” to attack the United States and employ “nonmilitary ways to defeat a stronger nation such as the United States through lawfare (that is, using international laws, bodies, and courts to restrict America’s freedom of movement and policy choices), economic warfare, biological and chemical warfare, cyberattacks, and even terrorism.”11

Their book, Unrestricted Warfare, received great attention and praise in the PRC. It is worth noting that after the 11 September 2001 terror attacks on the United States that partially fulfilled the colonels’ strategy, “pro-Chinese academics and business leaders in America quickly came to [the colonels’] defense—with the standard line that the colonels were on the ‘fringe of Chinese thought’.”12 But knowingly or unknowingly, these academics and business leaders were supporting a “carefully managed, secret, and audacious [public relations] and opinion-shaping operation, supervised by the top leaders in Beijing.”13 Both colonels were subsequently promoted and continued to be lauded within PRC military and civilian news media.14

The Three Warfares

The PRC’s three warfares consist of strategic psychological warfare; public opinion and media warfare; and legal warfare, also known as lawfare.15 Chinese strategic literature particularly emphasizes the role of the three warfares to subdue an enemy ahead of conflict or ensure victory if conflict breaks out. The three warfares are emblamatic of the PRC’s political warfare strategy: China’s use of the three warfares “constitutes a perceptual preparation of the battlefield that is seen as critical to advancing [the PRC’s] interests during both peace and war.”16 When employed in what U.S. defense officials might describe as a combined-arms approach, the three warfares “is a dynamic three dimensional war-fighting process that constitutes war by other means. . . . Importantly, for U.S. planners, this weapon is highly deceptive,” said Cambridge University professor Stefan A. Halper, who directed an Office of Net Assessment evaluation of this unconventional PRC strategy.17

The Center for a New American Security’s Elsa B. Kania states that “the three warfares is intended to control the prevailing discourse and influence perceptions in a way that advances China’s interests, while compromising the capability of opponents to respond.”18 Three warfares operations against the United States and other countries are designed to “seize the ‘decisive opportunity’ . . . for controlling public opinion, organiz[ing] psychological offense and defense, engag[ing] in legal struggle, and fight[ing] for popular will and public opinion. . . . This requires efforts to unify military and civilian thinking, divide the enemy into factions, weaken the enemy’s combat power, and organize legal offensives.”19 Kania lists the objectives of the three warfares as controlling public opinion, harming an adversary’s determination, collapsing an adversary’s organization, and restricting an adversary through law.20

Halper cites an example of a possible PRC three warfares operation against the United States as follows: “If the U.S. objective [is] . . . to gain port access for the [U.S. Navy] in a particular country, for example, China would use the Three Warfares to adversely influence public opinion, to exert psychological pressure (i.e., threaten boycotts) and to mount legal challenges—all designed to render the environment inhospitable to U.S. objectives.”21

Beijing’s psychological warfare includes diplomatic pressure, rumors, false narratives, and harassment to express displeasure, assert hegemony, and convey threats. According to a variety of texts used at the PLA’s National Defence University, the PRC psychological warfare strategy includes “integrating [psychological attacks] and armed attacks with each other . . . carrying out offense and defense at the same time, with offense as the priority . . . [and] synthetically using multiple forms of forces.”22 In military operations, psychological warfare will be “closely integrated with all forms and stages of military operations in order to intensify the efficacy of conventional attacks” while taking advantage of “opportune moments” and “striking first” to seize the initiative.23

Public opinion and media warfare refers to overt and covert media manipulation to influence perceptions and attitudes. According to PLA National Defence University texts, “public opinion warfare involves using public opinion as a weapon by propagandizing through various forms of media in order to weaken the adversary’s ‘will to fight’ . . . while ensuring strength of will and unity among civilian and military views on one’s own side.”24 Public opinion warfare instruments include films, television programs, books, the internet, and the global media network (particularly Xinhua and CCTV) and is directed against domestic populations in target countries. The PRC operates the Voice of China, Xinhua News Agency, and hundreds of publications that “are reinforced by the tailored use of local media outlets, strong social media capabilities, and cyber operations.” It also funds “the monthly publication of newspaper supplements—normally supplied by the People’s Daily—containing pro-Beijing news coverage in the major cities of many Western and developing countries.”25

Public opinion and media warfare include so-called “indoctritainment,” as exemplified in such movies as the 2017 propaganda blockbuster Wolf Warrior II. Further, Beijing has co-opted much of the Western film industry. According to U.S. vice president Michael R. “Mike” Pence, “Beijing routinely demands that Hollywood portray China in a strictly positive light. It punishes studios and producers that don’t. Beijing’s censors are quick to edit or outlaw movies that criticize China, even in minor ways.”26 By virtue of “the scale of its domestic market,” the PRC ensures that Hollywood avoids issues it deems sensitive and produces “soft propaganda movies that portray China in a positive light to global audiences,” such as 2016’s The Great Wall.27

Lawfare, or legal warfare, exploits “all aspects of the law, including national law, international law, and the laws of war, in order to secure seizing ‘legal principle superiority’ and delegitimize an adversary.”28 Tools used in lawfare include domestic laws, international legislation, judicial law, legal pronouncements, and law enforcement. They are often used in combination. In the PRC’s efforts to assert control over the South China Sea dispute, lawfare “has involved the utilization of rather tortuous interpretations of international law to oppose the Philippines’ position and seek to delegitimize the arbitration process.”29 In addition, the PRC has used lawfare to bolster its territorial claims by designating the South China Sea village of Sansha, on the disputed Paracel Islands, as part of Hainan Prefecture in an attempt to extend China’s control far into the South China Sea. Beijing also uses lawfare to block vital U.S. Marine Corps and other military activities in Japan and in U.S. Pacific island territories.30

Active Measures

The PRC’s political warfare also includes espionage and covert, Cold War-style active measures.31 As Kennan noted, the PRC reverses Clausewitz’s famous dictum that “war is the extension of politics by other means” by conducting political warfare as the extension of armed conflict by other means. Many policy makers and diplomats in the United States and friendly and allied countries fail to recognize these active measures as political warfare, thereby imperiling the security of their respective countries.32

Active measures tactics, techniques, and procedures include street violence, espionage, subversion, blackmail, assassination, bribery, deception, enforced disappearances and kidnapping, coerced censorship, and use of proxy forces. These tools may be employed for specific purposes, such as when an “enforced disappearance” in Thailand is used to silence an expatriate Chinese critic of the CCP.33 The “disappeared” critic is not the only political warfare target here. The overall political warfare impact, once such an enforced disappearance is publicized within the host nation, is substantial. Citizens of Thailand and freedom-seeking Chinese citizens hoping to find refuge in Thailand learn quickly that the Thai government cannot protect them from the PRC.

Liaison Work

Liaison work, a term used primarily by the PLA, supports the United Front Work Department (UFWD) and other political warfare operations, and it “runs the gamut of politics, finance, military operations, and intelligence to amplify or attenuate the political effect of the instruments of national power.”34 Mark Stokes and Russell Hsiao, citing PLA references, explain that liaison work missions include enemy “disintegration work . . . organizing and leading psychological warfare education and training . . . external military propaganda work . . . [and] assuming responsibility for relevant International Red Cross liaison and military-related overseas Chinese work.”35

Regarding PLA liaison work focused on the United States, J. Michael Waller, a political warfare expert, reports that “in an orchestrated campaign of good cop/bad cop, Chinese officials have gone directly to U.S. public opinion, trying to appeal to sentimental feelings of cooperation and partnership while literally threatening war. The operation is aimed at five levels: the American public at large, journalists who influence the public and decision makers, business elites, Congress, and the president and his inner circle.”36 Sanya Initiative and China Association for International Friendly Contact operations provide useful examples of how PLA liaison work is conducted.37

Subversion, more commonly referred to in PRC parlance as disintegration work, is the flip side of “friendly” united front and liaison activities.38 Ideological subversion targets political cohesion of coalitions, societies, and defense establishments. Political warfare operatives leverage propaganda, deception, and other means to undermine an opponent’s national will through targeting of ideology, psychology, and morale. As part of this disintegration mission, they also identify, evaluate, and recruit potential intelligence sources.39

Liaison work also addresses countersubversion to counter adversarial political warfare. The PRC views any effort to Westernize and weaken CCP control through peaceful evolution and promotion of universal values as subversion. As a result, psychological defense and ideological education is imperative to the PRC and includes such measures as internet monitoring and restricting media access.40 For example, Chinese students matriculating overseas find that “social media accounts are monitored and, in some cases, more intrusive electronic or Internet-based surveillance is used. Such monitoring sometimes precedes intimidation and pressure, including implicit and explicit threats to family members back in China or even the detention of those family members.”41

United Front

United front work is a classic Leninist strategy, devised by the Bolsheviks during the Russian Civil War and focused on cooperating with nonrevolutionaries for practical purposes (e.g., to defeat a common enemy) and winning them over to the revolutionary cause.42 Following the CCP’s effective use of a united front strategy that helped win the Chinese Civil War in 1949, this strategy came to be “an integral part of Chinese Communist thought and practice.”43 The united front strategy remains a vital element of PRC political warfare, not only for maintaining control over potentially problematic groups such as religious and ethnic minorities and overseas Chinese, but also as an essential element of the PRC’s interference strategy abroad.44 According to a Chinese Communist Party News article in 2015, the united front is one of PRC president Xi Jinping’s so-called “magic weapons” in achieving his “China Dream,” which he calls the “great rejuvenation.”45

Related to united front operations and PLA liaison work is the fact that the PRC now employs international organizations such as Interpol and the World Health Organization (WHO) to conduct its political warfare operations for it. For example, before the PRC admitted to detaining Interpol’s then-president Meng Hongwei, the U.S. Department of Justice was asked to investigate whether Meng, who was serving as Interpol’s president as well as the PRC vice minister of public safety, was abusing Interpol to harass or persecute dissidents and activists abroad.46 Concurrently, the WHO has been accused as acting as an agent of PRC political warfare by excluding Taiwan from the World Health Assembly during the past few years, in apparent violation of its own charter.47

Similarly, environmental activist groups have been subjected to UFWD overtures, apparently compromised by PRC funding as well. As one example, in 2017 the Wall Street Journal’s Greg Rushford exposed how multiple environmental organizations “are betraying their ideals in the pursuit of money and access in China.”48 His research highlighted the unwillingness of multiple activist groups, most notably Greenpeace, to take a stand against Beijing’s massive environmental destruction in the South China Sea through its dredging-based artificial island-building program and the silence of these activists regarding China’s massive overfishing of the South China Sea. As a more recent example, in late 2019 the Journal of Political Risk’s Michael K. Cohen exposed activist groups cooperating to ensure that the PRC maintains a total monopoly on the production of strategically vital rare earth minerals that the PRC has already used as a weapon against Japan and has public stated it will use against the United States.49

Public Diplomacy and Soft-to-Sharp Power

Some academics conflate political warfare with public diplomacy, but it is incorrect to do so. Public diplomacy is international political advocacy carried out in a transparent manner through routine media channels and public engagements. It differs from political warfare in terms of target and intent. While public diplomacy seeks to influence opinions of mass audiences, political warfare involves a calculated manipulation of a target country’s leadership, elites, and influential individuals to undermine the opposing side’s strategies, defense policies, and broader international norms. Public diplomacy attracts, while political warfare compels.

Another way to view PRC political warfare is through the terms soft power, hard power, smart power, and sharp power. The term soft power, as attributed to former U.S. government official Joseph S. Nye Jr., describes gentler, noncoercive means of influence, such as cultural, ideological, and institutional. In these areas, Nye hypothesized that the world would want to be like the United States, and that pull, in turn, would help the United States shape the world. For Nye, the basis of U.S. soft power was liberal democratic politics, free-market economics, and fundamental values such as human rights.50 Coercive measures, such as threat of military attack, blockade, economic boycott, coercion, and payment are termed hard power.51 The term smart power was coined to accommodate the use of “smart strategies that combine the tools of both hard and soft power” to achieve foreign policy objectives.52 Political warfare, as practiced by the PRC, entails soft, hard, and smart power. It also contains strategies that are not openly kinetic or forcefully coercive but are neither soft in the gentler attract-and-persuade sense. The PRC’s very aggressive influence and political warfare activities comprise what is now commonly referred to as sharp power.

A National Endowment for Democracy (NED) report defines sharp power as the aggressive use of media and institutions to shape public opinion abroad. It is “sharp” in the sense that it is used to “pierce, penetrate, or perforate the information and political environments in the targeted countries.”53 The NED report cautions that Beijing’s massive initiatives regarding news media, culture, think tanks, and academia should not be misconstrued as charm offensives or efforts to share alternative ideas to broaden the debate. Rather, through sharp power, “the generally unattractive values of authoritarian systems—which encourage a monopoly on power, top-down control, censorship, and coerced or purchased loyalty—are projected outward, and those affected are not so much audiences as victims.”54

The tendency of policy makers and academics to avoid the use of the term PRC political warfare in favor of the use of the term PRC sharp power is mistaken. This semantic choice blurs the fact that the PRC considers itself at war with the United States and all other nations against which it employs political warfare. Failure to understand the nature of the war the PRC is waging against it dampens the democracies’ ability to take appropriate countermeasures.

Hybrid Warfare

The concept of hybrid warfare is broadly defined as the mix of conventional and unconventional, military and nonmilitary, overt and covert actions employed in a coordinated manner to achieve specific objectives while remaining below the threshold of formally declared warfare.55 Like Russia, the PRC successfully employs hybrid warfare (sometimes called gray-zone warfare) to achieve its political aims. For example, Beijing has gradually expanded its control and influence in the South China Sea by constructing artificial islands, establishing military bases on them, sending maritime militia and China Coast Guard vessels to patrol claimed territorial waters, and declaring air identification zones. It has exerted control over most of the South China Sea this way, without firing a shot.

In pursuit of its version of hybrid warfare, the PRC applies its full spectrum of economic, legal, information, cyber, paramilitary, and military means to achieve its objectives in a slow and often ambiguous manner. It is generally careful to not cross any threshold that would trigger collective military action in response, thereby lowering the political price for its expansionist aggression.

Fascism and Totalitarianism

Finally, it is important to address the use of the terms totalitarian and fascist to characterize the CCP and the PRC as a society. While many academics, government officials, and business leaders in the United States fall silent when those terms are used to describe the PRC, it is important to accurately characterize the nature of the CCP and its rule. The definitions of the words totalitarian and fascist certainly apply to the PRC’s government. Totalitarian means “of or relating to centralized control by an autocratic leader or hierarchy . . . based on subordination of the individual to the state and strict control of all aspects of life . . . especially by coercive measures.”56 Fascism is

a political philosophy, movement, or regime . . . that exalts nation and often race above the individual and that stands for a centralized autocratic government headed by a dictatorial leader, severe economic and social regimentation, and forcible suppression of opposition . . . [and] a tendency toward . . . autocratic or dictatorial control.57

By these definitions, the PRC is inarguably totalitarian and fascist based on the CCP’s actions, laws, and culture. First, the CCP severely curbs the freedoms of its people, and dissent is crushed violently if necessary. Second, power is highly centralized, run on Marxist-Leninist tenets, and nominally communist—by definition, a totalitarian dictatorship. Third, the nation is exalted above the people. Hypernationalism or jingoism is powered by a sense of historical grievance or victimhood. China is overcoming its “century of humiliation” at the hands of Western imperialism, and every day Chinese children are exhorted to “never forget national humiliation.”58

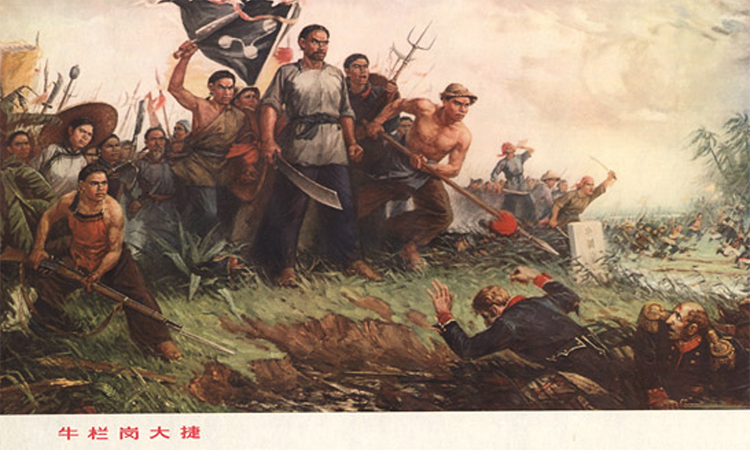

Figure 1.1. This painting depicts the Chinese perspective of the May 1841 Battle of Sanyuanli, a skirmish that led to an Anglo-Chinese “information war” that Cantonese scholars won. In Chinese legend, this battle is now perceived as the “first time in modern history that the Chinese people stood up against foreign imperialism and aggression.”

Source: “Great victory at Niulan Hill, 1975,” Chineseposters.net.

Additional rationales for labeling the PRC a totalitarian state are best explained by Chinese human rights lawyer Teng Biao and King’s College of London Professor Stein Ringen. Teng writes that “Xi Jinping’s new totalitarianism and Mao’s old style of totalitarianism don’t differ by all that much. . . . the Party has monopolized the media . . . established the Great Firewall, and persecuted intellectuals for their writing. . . . Black jails, forced disappearances, torture, secret police, surveillance, judicial corruption, controlled elections, forced demolitions, and religious persecution have all been rampant. . . . China is adopting a ‘sophisticated totalitarianism’.”60 Ringen wrote in a public letter to fellow China analysts in September 2018 that Xi’s “China Dream ideology of nationalism and chauvinism” has resulted in “totalitarian patterns of state rule.” He concludes, “We should now recognize this [totalitarianism] in the language we use.”61 Along with adding the term political warfare to the daily lexicon of confronting the PRC threat, it is time for the U.S. government and academia to use the terms totalitarian and fascist when describing the nature of the CCP’s regime.

A Brief History of PRC Political Warfare

The precepts of Chinese political warfare extend back to at least 500 BCE. Accordingly, an understanding of how the PRC conducts political warfare requires a brief overview of China’s unique history. While the PRC is a relatively new, modernized militarily powerhouse, its current foreign and security policies have deep roots in its ancient history. The bloody Warring States period (~475–221 BCE), which led to the unification of the seven feuding states under the Qin Dynasty, plays a particularly important role in defining the PRC’s approach to strategy, political warfare, strategic deception, and stratagems for rising powers intent on “overturning the old hegemon and exacting revenge.”62 Michael Pillsbury writes that the strategy the CCP uses in the PRC’s drive for supremacy is largely the result of lessons derived from the Warring States period. Resultant stratagems are based on nine principles, summarized briefly below:

- Induce complacency to avoid alerting your opponent.

- Manipulate your opponent’s advisers.

- Be patient—for decades or longer—to achieve victory.

- Steal your opponent’s ideas and technology for strategic purposes.

- Military might is not the critical factor for winning a long-term competition.

- Recognize that the hegemon will take extreme, even reckless action to maintain its dominant position.

- Never lose sight of Shi (a simple definition for which includes deceiving others to do your bidding for you and waiting for the point of maximum opportunity to strike).

- Establish and employ metrics for measuring your status relative to other potential challengers.

- Always be vigilant to avoid being encircled and deceived by others.63

While acknowledging the impact of China’s long history in laying a foundation for the PRC’s current strategic culture, it is important to recognize that the PRC’s political warfare has its strongest roots in the history of the CCP. These roots include fears regarding the PRC’s geostrategic situation and the relationship between the CCP and the Soviet Union in the first half of the twentieth century.

A Tough Neighborhood Fosters Xenophobia

Apologists for the CCP’s aggressive, expansionist, xenophobic, and brutally repressive policies often justify them on the basis of China’s long history of conflict and invasion. China’s history has, in fact, been turbulent. Across two millennia, “Chinese regimes were forced to fight for their survival against powerful invaders that either swept across the Eurasian plains or assaulted across the eastern seaboard. The few geographical barriers on this vast land mass provided only limited protection, and the resulting security challenges foster . . . a strong civilizational identity, and deep nationalism.”64 This history of conflict has also generated intense xenophobia.

The CCP was not the first despotic regime to excite paranoid xenophobia, but it has exploited it quite successfully. It has a compelling ability to control the information, thoughts, and actions of both its internal population and, increasingly, the populations of other countries through means most likely unimaginable to early emperors.65

This totalitarian perspective, grounded in the Warring States experience and the first emperor Qin Shi Huang’s worldview, provides the traditional strategic culture of centralized despotism, coercion, and persuasion that lay the foundation for contemporary CCP political warfare. From the earliest Shang and Zhou dynasties, despotic autocracy was the natural order of life, with no compact like a Magna Carta or Declaration of Independence or concepts like human rights intervening between an emperor and control of his subjects.

Ancient Despots as CCP Role Models

Emperor Qin Shi Huang imposed China’s first totalitarian state. He instituted a control regime later copied by communists worldwide by assigning political commissars to spy on governors and military commanders to ensure they did not deviate from his policies or criticize government policy.66 His control over his 40 million-or-so subjects was comprehensive: “Severe punishment was the order of the day . . . for major capital crimes, the offender and his entire family were annihilated. For even the most minor infractions, millions were sent to forced labor projects such as building imperial highways and canals. . . . Private ownership of books was prohibited . . . [and] three million men were branded and sent to labor camps for owning books.”67

Qin’s foreign policy was one of aggressive expansionism, designed to achieve absolute dominance in the near region and, by slow extension, over the world—that is, to achieve hegemony. Hegemony, the natural external extension of totalitarianism, would lead to order and ensure the empire avoided the chaos and disorder that characterized so much of China’s history.

But the quest for hegemony was also related to a sense of racial superiority and of supremacist entitlement. Both would be the basis of many subsequent totalitarian regimes—with Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich representing one of the most genocidal versions—but those regimes largely disappeared into the ashes of history following wars or other destructive forces. For the PRC, however, these factors underpin the China Dream, a concept first postulated by PLA senior colonel Liu Mingfu that outlines how the PRC will, through stealth and strength, become the “world’s leading power, surpassing and then replacing the United States.”68 The characters for China literally mean “central nation,” and notions of centrality and superiority, to include pervasive allusions to the superiority of the Han race, historically pervade Chinese literature and thought.

To be the hegemon—the dominant axis of power and the geographic geopolitical center of the world—China required that all other nations become vassal or tributary states. China’s elites believed their emperor to be the only legitimate political authority in the known world, and the Chinese were the highest expression of civilized humanity.

Accordingly, they treated “barbarian nations” as a suzerain would, exacting tribute, imposing unequal conditions, and influencing so-called barbarian leaders and peoples through both hard military and soft cultural and economic power. For 2,000 years, China maintained hegemony over regional vassal and tributary states and, to an extent, European states beginning with the Portuguese in the late 1500s. This situation was sustained by both de facto political warfare and powerful armies.69

Largely because of these demanding strategic circumstances, there have been strong incentives for China’s rulers to harness all the resources of society in innovative ways. Circa 500 BCE, Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu argued strongly for political, psychological, and other noncombat operations to subdue enemies prior to committing armies to combat.70

In the early twentieth century, Chinese Communists such as Mao Zedong carried with them Qin’s totalitarian tendencies and Sun Tzu’s strategic prescriptions as they sought revolutionary inspiration from Marxist-Leninist ideology. In the 1920s and 1930s, Vladimir Lenin and then Joseph Stalin ruled the Soviet Union, and their particularly virulent perspectives on achieving and maintaining power would influence the fledgling CCP greatly.

Figure 1.2. The foundations of Chinese political warfare were laid by the Soviet Union and the tenets of Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin, and Joseph Stalin. Mao Zedong adapted the Soviet model to embody “Chinese characteristics.” Pictured on the flag behind Mao, from left to right, are Stalin, Lenin, Friedrich Engels, and Marx.

Source: “Long Live the Great Marxism-Leninism-Mao Zedong Thought,” Chineseposters.net.

Soviet Influence

In nearly all aspects, Moscow initially provided the role model for CCP policy, organization, and operations—including, especially, political warfare. Mao and his followers learned operational arts such as political warfare from the Moscow-led Communist International (Comintern).71 As they did, they adapted Soviet operational arts with their own unique historical context, merging Western revolutionary theory and practice with Mao’s version of what might be termed “total war with Chinese characteristics.”

Mao combined this historical strategic culture, Comintern instruction, and insights from Clausewitz, Lenin, Leon Trotsky, and others. He then developed, tested, and refined a new concept of revolutionary war to overthrow Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang (KMT, or Nationalist Party) government and force it into exile on Taiwan. Mao also used the concept in his more limited efforts to defeat the Japanese forces that had invaded China during World War II. The importance of early political operations laid a solid foundation for Chinese military doctrine for revolutionary and unconventional war, both internal and external to China, as well as for a broader range of operations.72 Regarding operations external to China, Mao wrote:

Lenin teaches us that the World revolution can succeed only if the proletariat of the capitalist countries supports the struggle for liberation of the people of the colonies and semi-colonies. . . . We must unite with the proletarians of . . . Britain, the United States, Germany, Italy, and all other capitalist countries; only then can we overthrow Imperialism . . . and liberate the nations and the peoples of the world.73

To this end, Mao and the CCP used political warfare to promote China’s rise within a new international order and to defend against perceived threats.

The United Front: Mao’s—and Xi’s—Magic Weapon

Mao called for worldwide revolution using united fronts.74 He described the mission of united front work as follows: “to mobilize [the party’s] friends to strike at [the party’s] enemies.” Using a term that would be resurrected by Xi Jinping half a century later, Mao described united fronts as a “‘magic weapon’ on par with the military power of the Red Army (the revolutionary-era name for the PLA).”75

In the PRC, this strategy was first used to create an alliance between the CCP and KMT to end warlordism.76 In the early CCP, underground political work was segmented into multiple systems. An Urban Work Department, which evolved in the UFWD, “focused on ordinary citizens, minorities, students, factory workers, and urban residents.” A Social Work Department “concentrated on the upper social elite of enemy civilian authorities, security of senior CCP leaders, and Comintern liaison.”77

During the civil war between the CCP and KMT, these enemy work and liaison works were critical means of undermining the enemy’s morale and building domestic and international support in order to win the war on the mainland. The CCP’s focus on influencing, co-opting, subverting, and demoralizing an adversary’s’ elites and military forces has remained consistent for more than 80 years.

Active Measures

The CCP closely studied Moscow’s relentless political warfare during the twentieth century, particularly its active measures and how it employed black and gray active-measure tactics. The Soviet Union used black and gray active measures for different purposes. For example, the KGB (Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti, or Committee for State Security) “was responsible for ‘black,’ or covert active measures, which employed agents of influence, covert media manipulation, and forgeries in order to shape foreign public perception and attitudes of senior leaders.” On the other hand, gray active measures were used to influence institutions by “leverag[ing] united front entities, think tanks, institutes, and other non-governmental organizations that enabled an ostensibly independent line from the Soviet party-state. Gray propaganda offered plausible deniability as required.”78

Active measures could also include violence by proxy armies. The PRC’s support of the proxy United Wa State Army (UWSA) in Myanmar seems an anomaly to many diplomats, academics, and journalists today, but such support has been the norm for the PRC since 1949. Its proxy armies across Southeast Asia kept the United States and its allies in the region distracted and cost them dearly and greatly undermined nation building for more than four decades of the Cold War. Robert Taber, a leading counterinsurgency analyst of the mid-twentieth century, summarized how the Chinese undertook these political warfare campaigns in enemy countries:

Usually the revolutionary political organization will have two branches: one subterranean and illegal, the other visible and quasi-legitimate. . . . But its real work will be to serve as a respectable façade for the revolution, a civilian front . . . made up of intellectuals, tradesmen, clerks, students, professionals, and the like—above all, of women—capable of promoting funds, circulating petitions, organizing boycotts, raising popular demonstrations, informing friendly journalists, spreading rumors, and in every way conceivable waging a massive propaganda campaign aimed at two objectives; the strengthening and brightening of the rebel “image,” and the discrediting of the regime.79

Using these and related techniques, Beijing funded, supplied, and helped train forces engaged in so-called national liberation and independence movements and insurgencies from the 1950s through the 1980s. Focus areas were primarily the newly developing worlds of Southeast Asia, with some support in South Asia, Africa, and Latin America.80

Today, the PRC continues its use of proxy armies such as the UWSA, which administers a region the size of Belgium on the Sino-Myanmar border, a major hub in the Asian narcotics trade. With direct support from the PRC, the UWSA is now the largest nonstate military actor in Asia, a well-equipped and well-led force that is the major power broker in Myanmar, influencing that country’s stalled peace process.81 The PRC-backed Kokang rebels, who are of Chinese descent, are also proxies of Beijing’s efforts to occupy the Kokang region of Myanmar in a manner similar to the Russian annexation of Crimea.82

The Charm Offensive and the Rejuvenated United Front

In addition to active measures, the PRC has advanced to a remarkable degree in its ability to use soft power to obtain global influence, as reflected in its charm offensive that it initiated in the late 1990s. The Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989 further weakened the PRC’s influence, but it also served as a turning point for the CCP in terms of both internal propaganda and suppression, with subsequent refinement of its external influence capabilities.83 However, by the late 1990s, the PRC had begun a very sophisticated global charm offensive based on a systematic, coherent soft power strategy that complemented its overall political warfare tactics and operations. Beijing employed a wide range of influence-related reforms, such as significantly upgrading the quality and sophistication of its diplomatic corps, to engage successfully worldwide.

The CCP was helped greatly in its progress by the United States’ retreat from the international stage in the 1990s, according to Joshua Kurlantzick, a visiting scholar at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace who has covered PRC influence operations extensively for major news organizations.84 For example, the United States dismantled its main public diplomacy and counterpolitical warfare organization, the United States Information Agency, and it neglected many of the multilateral institutions that were built after World War II.

The foundation was laid for a rising China to assert itself on the world stage as America’s influence appeared to wane. The CCP felt confident that it now could surpass the United States as it watched Washington insulate itself from foreign affairs and retreat “from the world, consumed with its own economic boom, with the Internet, and with American culture wars.”85

The PRC then set about “shaping its regional environment” by focusing its soft power tools to portray itself as “a benign, peaceful, and constructive actor in the world.”86 The PRC’s influence and image were bolstered through its increasingly sophisticated diplomatic corps as well as through prominent PRC-funded infrastructure, public works, and economic investment projects in many developing countries.87 Such investments should be viewed as a “barely-disguised geo-strategic vision of China dominating the Eurasian continent in the second half of the 21st century.”88

Political Warfare in the Xi Jinping Era

Since 2012, the PRC has become even more sophisticated and more ambitious in its use of political warfare to achieve its broad strategic objectives.89 Beijing has begun employing a variety of techniques to shape the perceptions of leaders and elites in the advanced industrial nations, including the United States, as well as in the developing world. These methods vary, but they include the funding of university chairs and think tank research programs, offers of lucrative employment to former government officials who have demonstrated that they are reliably friendly to PRC interests, and all-expenses-paid junkets to China for foreign legislators and journalists.

Punitively, the PRC uses expulsion of foreign media to silence views that present unfavorable views of China to overseas audiences. The PRC has sophisticated use of well-funded official, quasi-official, and nominally unofficial media platforms that deliver Beijing’s message to the world. It has also established media outlets in nearly all key regions and major cities across the globe, while pro-Beijing entities now own and tightly control almost all Chinese-language newspapers and most Chinese-language social media platforms. The CCP routinely attempts to force leading Western publishers to censor their material in Beijing’s interests.90

Political warfare by the PRC also includes placing economic pressure on movie studios and media companies to avoid politically sensitive content to ensure continued access to the vast Chinese market. The PRC mobilizes and exploits overseas Chinese and local ethnic Chinese communities to support Beijing’s aims, and “numerous Chinese front organizations play important roles, such as recruiting personnel to undertake basic intelligence functions.”91

In the new world of social media, the PRC has found a fertile information environment to amplify its time-honed tactics of political and psychological warfare. For the PRC, the benefit of using social media to flood its adversaries’ societies with propaganda and disinformation is that it ultimately weakens trust in democratic institutions and can lead to political instability. In pursuit of social media dominance, the PRC has established PLA cyber forces of “about 300,000 cyber-savvy soldiers . . . while over 2 million are believed to be members of the ‘50 Cent Army’.”92 The CCP pays its so-called “50-Cent Army” to post propaganda in favor of the PRC.93

PLA Strategic Support Forces

The PLA’s role in cyber operations and psychological warfare rates special note. According to a U.S. National Defense University report, in late 2015, the PLA “initiated reforms that have brought dramatic changes to its structure, model of warfighting, and organizational culture.”94 These reforms included the creation of a Strategic Support Force (SSF), which centralized many PLA capabilities, including space, cyber, electronic, and psychological warfare.95

Specifically, the new strategic roles of the SSF are key to how the PLA plans to fight and win “informationized” wars, to use PLA parlance, and how it will conduct information operations. The SSF appears to have incorporated elements of the PLA’s psychological and political warfare missions, a result of a subtle yet consequential PLA-wide reorganization of the PRC’s political warfare forces. This may portend a more operational role for psychological operations in the future.

The PLA views the SSF’s “information support” and “information operations” as essential for “anticipating adversary action, setting the terms of conflict in peacetime, and achieving battlefield dominance in wartime.”96 The SSF supports the overall political warfare goal of winning without fighting by “shaping an adversary’s decisionmaking through actions below the threshold of outright war [and] accomplishing strategic objectives without escalating to open conflict.”97 Across the economic, military, and political spectrums, “salami-slicing tactics and cabbage strategies have become core components of the Chinese military and security diet, and with laudable success.”98 Salami slicing refers to a long-term strategy of gradual occupation of land, slow enough to not cause international reaction. Cabbage tactics generally refer to China’s occupation of, for example, rocks and islets in the South China Sea. The PRC will occupy a small rock and then surround that rock with infrastructure and military, just as a cabbage is surrounded by leaves.

The United Front Returns to the Forefront

The PRC’s effective use of what amounts to fifth columns (groups who sympathize with an enemy and work to undermine their own country) overseas through the UFWD took on new impetus with Xi Jinping’s ascension to the leadership of CCP and PRC in 2012 and 2013, respectively. Xi’s father, Xi Zhongxun, led united front and other political warfare operations through much of his career, and this has impacted Xi Jinping’s understanding of its value.99

In Xi’s view, the time had come for a strong and confident China to move beyond former PRC leader Deng Xiaoping’s advice to hide its assets and bide its time. Arguably, Xi was elevated to implement this long-term PRC strategy that Deng had telegraphed and most Western poititicans and analysts chose to ignore: that one day the PRC would no longer hide its capabilities or intentions. Delegates to the Central Committee’s 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (2012) were lectured on the importance of united front work, and the bureaucracy hastened to comply.100

The CCP’s united front work aimed at the outside world has consolidated since the 19th National Congress (2017). Anne-Marie Brady reports that since then,

Xi has removed any veneer of separation between the Chinese Communist Party and the Chinese state. So while the United Front Work Department does indeed play an important role in CCP united front work, comprehending China’s modern political warfare tactics requires a deep understanding of all the CCP’s agencies, their policies, their leadership, their methodology, and the way the party-state system works in China.101

Brady projects that Xi-era united front activities will focus on four key areas. These include managing the Chinese diaspora (Han and other ethnic minorities) for use as agents of PRC foreign policy and punishing those who do not cooperate. The PRC wants to co-opt and cultivate relationships with foreign economic and political elites to promote the CCP’s global foreign policy. Third, the PRC will focus on expanding a global communication strategy to promote the CCP and its priorities. Finally, the PRC will develop a China-centered economic and strategic bloc as exemplified by the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI, also known as the One Belt, One Road initiative, or OBOR).

Regarding the BRI, Brady describes Xi’s initiative as “a classic united front activity.” It is, she notes, “pitched as ‘beyond ideology’ and designed to create a new global order, which CCP analysts describe as ‘Globalization 2.0’.”102 United front work supports the BRI, and vice versa. The CCP has acquired, through many means such as bribery and coercion, allies and clients throughout the economic and political elite of many countries at national and local levels and is getting them to promote acceptance for BRI in their respective countries.

To influence the Chinese diaspora, much of the PRC’s propaganda efforts target overseas Chinese students and communities.103 These groups often feel a strong sense of patriotism toward their homeland. To build on and exploit these sentiments, in 2016 “the Chinese Ministry of Education wrote that it is a priority to ‘strengthen the propagation of the Chinese Dream abroad: harness the patriotic capabilities of overseas students [and] establish an overseas propaganda model which uses people as its medium’.”104 With its increasing control of both Chinese-language and foreign news media organizations abroad, the PRC attempts to whip overseas Chinese into a hypernationalistic frenzy and employs them to influence, obstruct, and politically paralyze any nation that opposes the PRC’s actions.105

In congressional testimony, retired U.S. Navy captain James E. Fanell assessed that Xi and the CCP will exploit these overseas Chinese to undermine military and political adversaries worldwide and use them to advance the CCP’s political and military objectives. Prime among these tactics will very likely be lobbying for the establishment of more PRC military access for PLA forces operating globally. With an operational base already established in Djibouti on the Horn of Africa, the PLA Navy now operates in the Indian and Arctic Oceans and the Mediterranean and Baltic Seas. The PRC has sealed long-term port deals that span the globe, including in Australia, Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei, Myanmar, the Strait of Malacca, Myanmar, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Djibouti, Tanzania, Mauritius, Namibia, and Greece. The PRC is attempting to acquire berthing in the Azores and is currently negotiating port deals in the Maldives, Scandinavia, and Greenland. These ports already provide critical berthing and logistics to the PLA Navy, including refueling, provisions, and maintenance.106

Counteroffensive PRC Political Warfare

Brady warns that in light of worldwide revelations regarding the PRC’s political warfare and influence operations, the PRC continues to expand united front work activities aimed at the outside world while it has launched a counter-strategy “to combat international criticism of its political interference behavior.”107 Furthermore, the CCP does not feel the need to hide its united front activities internationally, including “attempts to leverage overseas Chinese as agents of diplomatic objectives, pressure foreign universities and movie studios to accept Chinese censorship guidelines, and co-opt foreign elites into supporting Beijing’s goals. The Party now feels it operates from a position of strength compared to its united front targets.”108

As described by Nadège Rolland at the National Bureau of Asian Research, the PRC has established a layered defense, starting with the protection of its domestic perimeter and incrementally extending outward. It stifles the inward flow of liberal democratic values and ideals within its territory through a “Great Firewall around China’s cyberspace and strengthening party control over domestic media and information circulation.” The CCP has also intensified domestic propaganda, says Rolland, and so-called patriotic education to inoculate its people against dangerous ideas that might slip through the first line of defense. In its “counterattack mode,” the CCP targets “audiences outside of the Chinese diaspora, striking deeper into the adversary’s territory, and hitting hard.” The PRC “is actively targeting foreign media, academia and business communities through the deployment of front organisations” to co-opt foreigners and is retaliating against those who it sees threatening its core interests at any level.109

Conclusion

The PRC poses, as General Berger states, an existential threat. As its primary weapon in its war against the United States and its partners and allies, the PRC conducts a relentless, multifaceted onslaught of political warfare campaigns, often with hard-to-recognize strategies, tactics, techniques, and procedures.

It is worth remembering that, at one time, the United States was quite good at conducting political warfare operations. During the Cold War, the U.S. government successfully waged political warfare against the Communist Bloc using an array of methods. The Cold War proved that if America displays the strength and leadership to fight back, partners and allies will follow.

The United States must rebuild these political warfare capabilities on an urgent basis to safeguard its values, freedom, and sovereignty. There is a massive challenge ahead simply to inoculate American institutions and citizens against the existential threat posed by PRC political warfare. As great a challenge is the massive investment of intellect and resources required to rebuild the capabilities to successfully identify, deter, counter, and defeat PRC political warfare.

The purpose of this article is to provide an overview of two key aspects of the PRC’s extensive political warfare operations: the definitions and terminology required to conceptualize the fight and the history of the PRC’s pathway to its current predominant political warfare capability. It is important to study both topics to help lay part of the intellectual foundation that the United States needs to counter this existential threat. It is time to stop losing the political warfare contest with the PRC; now is the time to engage in the fight and ultimately win the war.

Endnotes

- Megan Eckstein, “Berger: Marines Focused on China in Developing New Way to Fight in the Pacific,” U.S. Naval Institute News, 2 October 2019.

- Donald J. Trump, National Security Strategy of the United States of America, December 2017 (Washington, DC: White House, 2017).

- Ross Babbage, Winning without Fighting: Chinese and Russian Political Warfare Campaigns and How the West Can Prevail, vols. I and II (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 2019).

- C. Thomas Thorne Jr. and David S. Patterson, eds., Foreign Relations of the United States, 1945–1950: Emergence of the Intelligence Establishment (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1996), document 269, hereafter FRUS, document 269.

- J. Y. Smith, “George F. Kennan, 1904–2005: Outsider Forged Cold War Strategy,” Washington Post, 18 March 2005.

- FRUS, document 269.

- FRUS, document 269.

- Mark Stokes and Russell Hsiao, The People’s Liberation Army General Political Department: Political Warfare with Chinese Characteristics (Arlington, VA: Project 2049 Institute, 2013), 5–6.

- Cols Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui, Unrestricted Warfare: Assumptions on War and Tactics in the Age of Globalization (Beijing: PLA Literature and Arts Publishing House, 1999).

- Qiao and Wang, Unrestricted Warfare.

- Michael Pillsbury, The Hundred-Year Marathon: China’s Secret Strategy to Replace America as the Global Superpower (New York: Henry Holt, 2015), 3, 116.

- Pillsbury, The Hundred-Year Marathon, 117.

- Pillsbury, The Hundred-Year Marathon, 17.

- Pillsbury, The Hundred-Year Marathon, 116–17, 138.

- Elsa Kania, “The PLA’s Latest Strategic Thinking on the Three Warfares,” Jamestown Foundation, China Brief 16, no. 13, 22 August 2016.

- Kania, “The PLA’s Latest Strategic Thinking on the Three Warfares.”

- Stefan Halper, China: The Three Warfares (Washington, DC: Office of the Secretary of Defense, 2013), 11.

- Kania, “The PLA’s Latest Strategic Thinking on the Three Warfares.”

- Kania, “The PLA’s Latest Strategic Thinking on the Three Warfares.”

- Kania, “The PLA’s Latest Strategic Thinking on the Three Warfares.”

- Halper, China, 12.

- Kania, “The PLA’s Latest Strategic Thinking on the Three Warfares.”

- Kania, “The PLA’s Latest Strategic Thinking on the Three Warfares.”

- Kania, “The PLA’s Latest Strategic Thinking on the Three Warfares.”

- Babbage, Winning without Fighting, vol. I, 35–36.

- Michael J. Pence, “Remarks by Vice President Pence on the Administration’s Policy toward China” (speech, Hudson Institute, Washington, DC, 4 October 2018).

- Babbage, Winning without Fighting, vol. I, 35–36.

- Kania, “The PLA’s Latest Strategic Thinking on the Three Warfares.”

- Kania, “The PLA’s Latest Strategic Thinking on the Three Warfares.”

- Kerry K. Gershaneck, “‘Faux Pacifists’ Imperil Japan while Empowering China,” Asia Times (Hong Kong), 10 June 2018; and Babbage, Winning without Fighting, vol. II, 17–25.

- Stokes and Hsiao, The People’s Liberation Army General Political Department, 3, 14, 38.

- Interviews and discussions with Thai and foreign academics, Thailand, 11–15 April 2018; discussions with senior Republic of China political warfare officers at Fu Hsing Kang College, National Defense University, Taipei, Taiwan, 13 March 2019; and interviews with a senior U.S. Department of State official, Bangkok, Thailand, 14 April 2018.

- Kasit Piromya, interview with the author, Bangkok, Thailand, 1 May 2018.

- Stokes and Hsiao, The People’s Liberation Army General Political Department, 15.

- Stokes and Hsiao, The People’s Liberation Army General Political Department, 15.

- Stokes and Hsiao, The People’s Liberation Army General Political Department, 15.

- The Sanya Initiative began in 2008 as a PRC initiative to influence senior retired U.S. flag and general officers to support PRC security interests. The China Association for International Friendly Contact was founded in 1984 to establish and maintain rapport with senior foreign defense and security community elites, including retired senior military officers and legislators.

- Stokes and Hsiao, The People’s Liberation Army General Political Department, 15.

- Stokes and Hsiao, The People’s Liberation Army General Political Department, 15–16.

- Stokes and Hsiao, The People’s Liberation Army General Political Department, 16.

- Peter Mattis, “An American Lens on China’s Interference and Influence-Building Abroad,” ASAN Forum, 30 April 2018; and Stephanie Saul, “On Campuses Far from China, Still under Beijing’s Watchful Eye,” New York Times, 4 May 2017.

- Jonas Parello-Plesner and Belinda Li, The Chinese Communist Party’s Foreign Interference Operations: How the U.S. and Other Democracies Should Respond (Washington, DC: Hudson Institute, 2018), 8.

- Lyman P. Van Slyke, Enemies and Friends: The United Front in Chinese Communist History (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1967), 3, 8–9.

- Parello-Plesner and Li, The Chinese Communist Party’s Foreign Interference Operations, 8.

- “United Front Upgraded by Creation of Special Leading Small Group,” Chinese Communist Party News, 31 July 2015.

- Bridget Johnson, “DOJ Asked to Probe China’s Use of INTERPOL Notices to Persecute Dissidents,” PJ Media, 30 April 2018.

- Kerry K. Gershaneck, “WHO Is the Latest Victim in Beijing’s War on Taiwan,” Nation (Thailand), 22 May 2018.

- Greg Rushford, “How China Tamed the Green Watchdogs: Too Many Environmental Organizations Are Betraying Their Ideals for Love of the Yuan,” Wall Street Journal, 29 May 2017.

- Michael K. Cohen, “Greenpeace Working to Close Rare Earth Processing Facility in Malaysia: The World’s Only Major REE Processing Facility in Competition with China,” Journal of Political Risk 7, no. 10 (October 2019).

- Eric X. Li, “The Rise and Fall of Soft Power: Joseph Nye’s Concept Lost Relevance, but China Could Bring It Back,” Foreign Policy, 20 August 2018.

- Joseph S. Nye Jr., “Get Smart: Combining Hard and Soft Power,” Foreign Affairs 88, no. 4 (July/August 2009): 160–63.

- Nye, “Get Smart.”

- Juan Pablo Cardenal et al., Sharp Power: Rising Authoritarian Influence (Washington, DC: National Endowment for Democracy, 2017), 6.

- Cardenal et al., Sharp Power, 13.

- Chris Kremidas-Courtney, “Hybrid Warfare: The Comprehensive Approach in the Offense,” Strategy International, 13 February 2019.

- “Dictionary: Totalitarian,” Merriam-Webster, accessed 7 October 2019.

- “Dictionary: Fascism,” Merriam-Webster, accessed 7 October 2019.

- Xi Jinping, “Full Text of Xi Jinping’s Report at 19th CPC National Congress,” China Daily (Beijing), 4 November 2017.

- Kaori Abe, “The Anglo-Chinese Propaganda Battles: British, Qing and Cantonese Intellectuals and the First Opium War in Canton,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch 56 (2016): 172–93.

- Teng Biao, “Has Xi Jinping Changed China?: Not Really,” ChinaFile, 16 April 2018.

- Stein Ringen, “Totalitarianism: A Letter to Fellow China Analysts,” ThatsDemocracy (blog), 19 September 2018.

- Pillsbury, The Hundred-Year Marathon, 31–51.

- Pillsbury, The Hundred-Year Marathon, 35–36.

- Thomas G. Mahnken, Ross Babbage, and Toshi Yoshihara, Countering Comprehensive Coercion: Competitive Strategies against Authoritarian Political Warfare (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 2018).

- Yi-Zheng Lian, “China Has a Vast Influence Machine, and You Don’t Even Know It,” New York Times, 21 May 2018.

- Steven W. Mosher, Hegemon: China’s Plan to Dominate Asia and the World (San Francisco, CA: Encounter Books, 2000), 21.

- Mosher, Hegemon, 20–25.

- Pillsbury, The Hundred-Year Marathon, 28–29.

- Mosher, Hegemon, 2–5.

- Sun Tzu, The Complete Art of War, trans. Ralph D. Sawyer (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1996), 50.

- Stokes and Hsiao, The People’s Liberation Army General Political Department, 6–7.

- Mahnken, Babbage, and Yoshihara, Countering Comprehensive Coercion.

- Mao Zedong, Selected Works of Mao Tse-Tung (Beijing: Foreign Language Press, 1965), 104.

- Stokes and Hsiao, The People’s Liberation Army General Political Department, 3.

- Mattis, “An American Lens on China’s Interference and Influence-Building Abroad.”

- Van Slyke, Enemies and Friends, 3.

- Stokes and Hsiao, The People’s Liberation Army General Political Department.

- Stokes and Hsiao, The People’s Liberation Army General Political Department, 6.

- Robert Taber, The War of the Flea: A Study of Guerrilla Warfare Theory and Practice (New York: Citadel Press, 1965), 32–33.

- Joshua Kurlantzick, Charm Offensive: How China’s Soft Power Is Transforming the World (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008), 1–15.

- Bertil Lintner, The United Wa State Army and Burma’s Peace Process (Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace, 2019).

- Bertil Lintner, “A Chinese War in Myanmar,” Asia Times (Hong Kong), 5 April 2017.

- Kurlantzick, Charm Offensive, 25–48.

- Kurlantzick, Charm Offensive.

- Kurlantzick, Charm Offensive, 33.

- Kurlantzick, Charm Offensive, 51–52.

- Thomas Lum et al., Comparing Global Influence: China’s and U.S. Diplomacy, Foreign Aid, Travel, and Investment in the Developing World (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2008).

- Mahnken, Babbage, and Yoshihara, Countering Comprehensive Coercion, 39.

- Hearing: Strategic Competition with China in Front of the House Armed Services Committee, United States House of Representatives, 115th Cong. (statement, Aaron L. Friedberg, 15 February 2018).

- Mahnken, Babbage, and Yoshihara, Countering Comprehensive Coercion, 36.

- Mahnken, Babbage, and Yoshihara, Countering Comprehensive Coercion, 35.

- Keoni Everington, “China’s Troll Factory Targeting Taiwan with Disinformation Prior to Election,” Taiwan News, 5 November 2018.

- An Pei, “China to Train ’50-Cent Army’ in Online Propaganda,” Radio Free Asia, 12 March 2014.

- John Costello and Joe McReynolds, China’s Strategic Support Force: A Force for a New Era (Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, 2018), 1–2.

- Costello and McReynolds, China’s Strategic Support Force.

- Costello and McReynolds, China’s Strategic Support Force, 45.

- Costello and McReynolds, China’s Strategic Support Force, 45.

- Tobias Burgers and Scott N. Romaniuk, “Why Isn’t China Salami-Slicing in Cyberspace?,” Diplomat, 10 September 2019.

- Gerry Groot, “The Rise and Rise of the United Front Work Department under Xi,” Jamestown Foundation, China Brief 18, no. 7, 24 April 2018.

- Groot, “The Rise and Rise of the United Front Work Department under Xi.”

- Anne-Marie Brady, “Exploit Every Rift: United Front Work Goes Global,” in Party Watch Annual Report 2018 (Washington, DC: Center for Advanced China Research), 35.

- Brady, “Exploit Every Rift,” 36.

- Alexander Bowe, China’s Overseas United Front Work: Background and Implications for the United States (Washington, DC: U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, 2018).

- Parello-Plesner and Li, The Chinese Communist Party’s Foreign Interference Operations, 16n41.

- Julie Makinen, “Chinese Social Media Platform Plays a Role in U.S. Rallies for NYPD Officer,” Los Angeles (CA) Times, 24 February 2016.

- Hearing before the U.S. House of Representatives Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, 115th Cong., (statement, Capt James E. Fanell, USN [Ret],17 May 2018).

- Brady, “Exploit Every Rift,” 38.

- David Gitter, “Introduction: Trends Since the 19th Party Congress,” in Party Watch Annual Report 2018, 3.

- Nadège Rolland, “China’s Counteroffensive in the War of Ideas,” RealClearDefense, 24 February 2020.