Abstract: This article will examine the impact of military competition between the United States and China in the South China Sea on the regional security of Southeast Asia. Specifically, it will focus on the many implications of China’s continuous militarization of the South China Sea, including its construction of military installations on artificial islands and reefs and its overlapping claims in the region. China has become particularly aggressive in its militarization of the Spratly Islands as well as its claims in disputed waters where the Philippines has rights under its exclusive economic zone. This article will present some of the paths by China and the United States toward military conflict and analyze the competition that exists between these two nations today. It will be argued that U.S. and European approaches toward China should foster long-term strategic efforts in engaging Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries to help maintain regional security in the South China Sea and break through the facade of transactional approaches. This article will also point out that the United States and China are constrained in their attempts to engage in military cooperation, limited by their own national interests as well as competition in the Asia-Pacific region. The United States views China as challenging its long-standing great-power military dominance in the region, while China sees the United States as an obstacle against its own rise to power as it strengthens its national security through its militarization of the South China Sea.

Keywords: United States, China, South China Sea, Asia-Pacific region, Spratly Islands, Paracel Islands, great power competition, foreign policy, national security, military competition

The 2017 National Security Strategy of the United States sounded an alarm, announcing that the United States was reentering an era of “great power competition,” in which rival countries such as China and Russia “want to shape a world antithetical to U.S. values and interests.”1 In July 2019, The New York Times and The Washington Post reported that China released a national security document of its own, stating that “global military competition is rising, with the United States ‘strengthening its Asia-Pacific military alliances’ and engaging in ‘technological and institutional innovation in pursuit of absolute military superiority’.” The Chinese report noted that U.S. president Donald J. Trump’s administration had “adjusted” the U.S. national security position to “regard China as a rival.” It also stated that China had released a “military blueprint” to assert its claims over Taiwan and achieve its strategic aims in the Western Pacific, which includes the disputed South China Sea.2 Consequently, the United States and China have begun to compete for “great power” without boundaries.

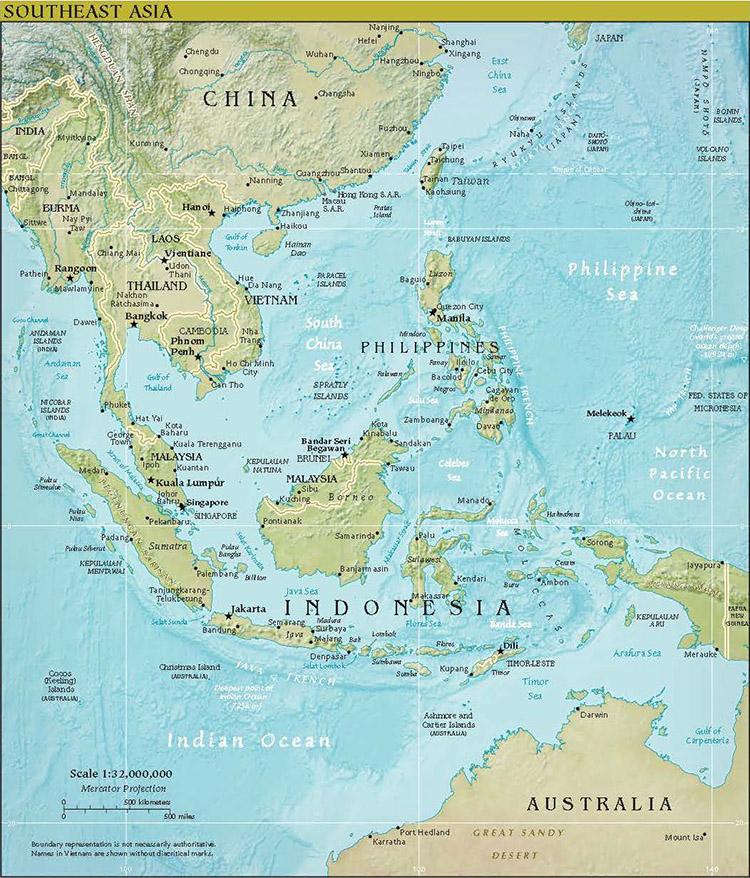

Map 1. Southeast Asia, identifying the location of the South China Sea within the Asia-Pacific region

Source: Perry-Castañeda Library, University of Texas at Austin.

China’s Approach toward Military Conflict with the United States

China’s evolving military strategy offers sector-by-sector expert assessments of the latest trends in Chinese military thought under Xi Jinping, president of the People’s Republic of China and general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party. This covers not only traditional battlespaces such as land, air, and sea but also China’s strategy for the new domains of space, cyberspace, and electronic warfare. As noted in the Jamestown Foundation’s China’s Evolving Military Strategy, “China views itself as facing a fundamental asymmetry vis-à-vis the United States in technological capabilities for information operations (IO), because it views IO as highly offensive-dominant with clear first-strike advantages.” To combat this disadvantage, “Chinese theorists call for high levels of military and civilian fusion and for low-level operations” such as network espionage and infiltration in peacetime.3 China employs this approach to prepare for potential conflicts that may arise with other nations.

A report on China’s space activities released in 2015 focuses largely on the nation’s overall development strategy, from weather modeling, communications, cultural education (also known as soft power), and other civil uses of new technologies.4 Journalist Zhao Lei of the China Daily stated in 2017 that military modernizations are taking place “to build the PLA [People’s Liberation Army] into a force capable of winning modern wars, which are characterized by information warfare and joint operations.”5 Zhao praised Xi Jinping for the range and scope of China’s modernization program and credited him for coming up with a serious plan to reinvigorate the PLA into a force that is leaner and more capable of defending China. Xi is often regarded in China as a catalyst of change who empowers national security against any threat to China’s sovereignty over its claims in the Western Pacific and its strategic aims in the Asia-Pacific region, including in the disputed South China Sea.

China views the United States as attempting to thwart its rise to power while simultaneously pursuing its own national interests in the South China Sea. China typically relies on “gray men” (cyber hackers) and “blue men” (fishermen) to conduct measures short of war that place China in a politically advantageous position but do not rise to a level that warrants a U.S. and/or Southeast Asian military response.6 Beijing continues to consider internet activities an important component within the paradigm of cyber and information security and views information sovereignty as key. Accordingly, the Chinese government has released numerous documents designed to punish online activities that threaten stability in the information space. Zhuang Pinghui at the South China Morning Post reported in 2016 that Xi has “urged the accelerated development of security systems to protect key information infrastructure.”7 It is implied, then, that China resorts to tactics that do not risk outright war or ignite military responses by other nations. Consequently, China’s approach to dealing with potential conflicts with the U.S. military is largely constrained, and it has set limits in its quest to build and gain great power hegemony over the Asia-Pacific region.

China’s aggressive territorial claims in the South China Sea continue to be sources of political friction and military conflict throughout the Asia-Pacific, with the rules of engagement being largely dictated by China and calling for U.S. military noninterference. For example, Stephen Burgess has emphasized the many implications of “low-level conflict” between China and Vietnam during the 1974 Battle of the Paracel Islands and subsequent disputes in the South China Sea in 1979, 1988, and 2014. In a 2019 interview with U.S. embassy officials in Hanoi, Burgess noted that because “there are currently limits to the strategic partnership” between Vietnam and the United States, Vietnam “will have to continue to confront China in the Paracel and Spratlys largely on its own,” which plays to China’s advantage.8

The United States’ Approach toward Military Conflict with China

The United States’ “rebalance” to Asia, announced by U.S. president Barack H. Obama’s administration in 2011 as a recommitment to the Asia-Pacific region, was welcomed by its ally Japan, which also saw strengthening ties with other U.S. regional allies such as Australia, South Korea, and ASEAN member states as a tenable national security strategy.9 The current U.S. approach to the Asia-Pacific fosters continuity of its long-term standing as a great power while inviting cooperation and harmony with its allies to maintain regional safety and security.

In 2016, U.S. secretary of defense Ashton B. “Ash” Carter reported in an article in Foreign Affairs that the United States had long maintained the safety and security of the Asia-Pacific region as a dominant great power. “Since World War II,” he noted, “America’s men and women in uniform have worked day in and day out to help ensure the security of the Asia-Pacific. Forward-deployed U.S. personnel in the region . . . have helped the United States deter aggression and develop deeper relationships with regional militaries.” Carter detailed that thousands of U.S. sailors and Marines “have sailed millions of miles, made countless port calls, and helped secure the world’s sea-lanes, including in the South China Sea,” and that “American personnel have assisted with training for decades, including holding increasingly complex exercises with the Philippines over more than 30 years.” He concluded that many leaders in the region possessed a strong desire for continued American presence and support.10

The U.S. approach toward military engagement with China fosters cooperation and competition of power. The 2017 and 2018 National Security Strategy of the United States, the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review, and the 2019 Missile Defense Review all recognize a growing pattern of military competition in a dynamic security environment, in which the United States will compete from a position of strength while encouraging China to cooperate on various security issues.11 This approach to engagement with China implies a reduction of risk and prevention of misunderstanding in times of escalating tension between the two nations.

Military Competition between the United States and China

Military competition between the United States and China for dominance in the Asia-Pacific region largely stems from problems in the South China Sea and Taiwan Strait, both of which remain volatile sources of conflict between the two nations. In September 2018, for example, U.S. and Chinese warships nearly collided in the South China Sea, coming within 45 yards of each other.12 China continues to challenge the United States’ powerful military presence in the region, which, according to Edward Wong at The New York Times, “relies on the [United States’] ability to have unfettered naval access to the South China Sea and the support of the self-governing island of Taiwan to bolster its standing.”13 Tensions between the United States and China have increased further due to demonstrations of military capabilities that dominate the region. Chinese military spokesman Wu Qian has stated, “If anyone dares to separate Taiwan from China, the Chinese military would not hesitate to go to war.” The Washington Post described Wu as laying out “what officials called a revised national defense policy for ‘the New Era’—a catchphrase that denotes the imprimatur of China’s assertive leader, President Xi Jinping.”14 This signals that the United States should not interfere in China’s claims over Taiwan, since it could lead to a war that could disturb ASEAN regional safety and security.

The U.S. Department of Defense reported in 2019 that China’s military modernization program “has become more focused on investments and infrastructure to support a range of missions beyond China’s periphery, including power projection, sea lane security, counterpiracy, peacekeeping, humanitarian assistance/disaster relief, and non-combatant evacuation operations.” China’s military modernization also has the potential to “degrade core U.S. operational and technological advantages” by way of “Chinese efforts to acquire sensitive, dual-use, or military-grade equipment from the United States [such as] dynamic random access memory, aviation technologies, and antisubmarine warfare technologies.” China has become more aggressive in asserting its claims over the South China Sea, which includes “placing anti-ship cruise missiles and long-range surface-to-air missiles on outposts in the Spratly Islands, violating a 2015 pledge by [President Xi] that ‘China does not intend to pursue militarization’ of the Spratly Islands.” Moreover, “China is also willing to employ coercive measures—both military and non-military—to advance its interests and mitigate opposition from other countries.”15

Amy Chang, Ben FitzGerald, and Van Jackson reported in 2015 that drives for emerging technologies and military capabilities could exacerbate the regional instability of maritime Asian countries. The danger is that due to a lack of regulations and established norms for these technologies and military capabilities, states may become more likely to employ coercive force, or there could be unintentional escalation due to miscalculations of other actors’ capabilities.16 Consequently, even if China justifies the strengthening of its defenses and claims in the South China Sea as a matter of national security, such actions are alarming to ASEAN communities. Conversely, the United States justifies its presence in the Asia-Pacific as a way to maintain regional safety and security by competing with China through military presence in the South China Sea, which supports Taiwan’s independence from China and the Philippines’ claims over the Spratly Islands.

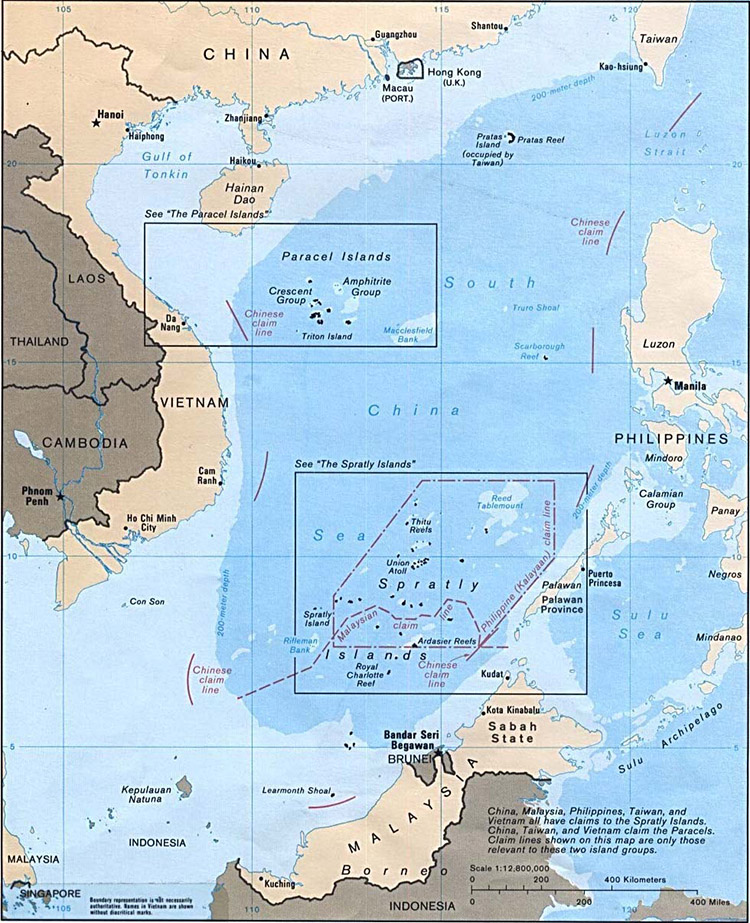

Map 2. 1988 map of the South China Sea, identifying the “nine-dash line” (highlighted in green) that justifies China’s claims in the South China Sea

Source: Perry-Castañeda Library, University of Texas at Austin.

U.S. and European Approaches toward a “Rising China” in the South China Sea

U.S. and European approaches toward China should foster long-term strategic partnerships and dialogue with ASEAN countries over maintaining regional security against China’s assertion that the “nine-dash line” justifies its claims in the South China Sea. The United States and European Union (EU) must also place even greater emphasis on military competition against China through the strengthening of U.S.-ASEAN and EU-ASEAN dialogue relations relevant to security cooperation and competition in addressing territorial disputes in the South China Sea.17 The ASEAN Regional Forum should become a venue for U.S. and European leaders to agree to stand against aggressive Chinese military aggression in the Asia-Pacific.18 The United States and EU should work together to strengthen their security roles in the region, specifically in maintaining peace and stability in the South China Sea. In this way, transatlantic security cooperation would foster its global influence and power in the region, which in turn could help maintain the global balance of power and uphold long-term partnerships by means of strategic multilateral partnerships. Pragmatic, strategic dialogue among ASEAN countries could promote stricter implementation on a code of conduct for the South China Sea.

A stricter implementation of the code of conduct for the South China Sea could serve as an alternative way in which to compel China and ASEAN states to respect and uphold rules-based international order in those disputed waters. Consequently, this code of conduct could weaken the aggressive territorial claims of China, even if China continues to advocate its “sovereign territory” rhetoric in the South China Sea as it rises to great-power status. Long-term engagement by the United States and European nations with ASEAN countries will play a crucial and significant role in upholding this rules-based international order and develop a concrete strategic security cooperation, which is urgently needed to move beyond merely supporting diplomatically ASEAN countries’ stances against China’s claims in the South China Sea. There is also a dire need for multilateral joint military backing and constant maritime exercises by the U.S. and EU militaries, with active involvement of ASEAN countries, to advance mutual political and economic interests in the South China Sea. Thus, a strategic multilateral partnership via military- and maritime-based approaches could foster long-term viable transactions to soften China’s aggressive territorial claims in the region.

China has become increasingly aggressive in asserting its sovereignty over islands in the South China Sea and adjacent waters, which has led to disputes among claimant countries. These overlapping claims are evidenced by Chinese notes verbales that depict a map of the nine-dash line denoting China’s claims in the South China Sea. In 2009, China sent two such notes verbales to the secretary general of the United Nations (UN) in response to a joint submission by Malaysia and Vietnam to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf. The Chinese note stated that “China has indisputable sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea and the adjacent waters, and enjoys sovereign rights and jurisdiction over the relevant waters as well as the seabed and subsoil thereof. . . . The above position is consistently held by the Chinese government, and is widely known by the international community.”19

Importantly, U.S.-ASEAN and EU-ASEAN relations are mostly transactional due to the fact that the United States and EU are neither parties involved nor claimant states in the disputed South China Sea, meaning that neither country is directly involved in negotiations or talks regarding the code of conduct for the South China Sea. Moreover, even though the United States and EU are critical in their diplomatic positions regarding China’s military modernization of the South China Sea, they have no collective voice. This is because some EU countries have opted to resort to a soft tone to protect their economic ties with China, even as the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and Germany remain strong in their stance against China to uphold international law in the region. Robin Emmott has observed that “the European Union is neutral in China’s dispute with its Asian neighbours in the South China Sea,” noting that “speaking with one European voice has become difficult as some smaller governments, including Hungary and Greece, rely on Chinese investment and are unwilling to criticize Beijing despite its militarization of South China Sea islands.”20

The United States’ approach is also constrained, due to its uninvolvement in the development of a code of conduct for the South China Sea. Nevertheless, Mark D. Clark, director of the Office of Maritime Southeast Asia of the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs, stated in 2019 that while the United States is “not a party to negotiations nor a claimant state, it has a ‘vested interest’ in the outcome of the code of conduct.” Although the United States may not be involved in “immediate talks on the code of conduct,” Clark noted, it “has a very important national interest in the South China Sea” as an “international waterway” and an “international airspace.”21

It can be argued that current U.S. and European approaches toward engaging ASEAN nations regarding Chinese aggression and expansion in the Asia-Pacific region do not represent a viable strategy. However, a multilateral strategic partnership could leverage strengthening regional security cooperation among ASEAN member states to address and strictly implement rules-based international order in South China Sea disputes. The most controversial current issue in the South China Sea is the overlapping claims of China and the Philippines over the Spratly Islands. This was made evident in the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) case of Philippines v. China, which in 2016 ruled in favor of the Philippines against China’s nine-dash line claims in the South China Sea.22 Nevertheless, China still upholds its claims without any legal basis, demonstrating how it aggressively disregards international law and arbitral ruling. China’s continued militarization in the Spratly Islands offers clear evidence of its continuing aggressive rise to power and crucial assertion of hegemony in the Asia-Pacific and beyond.

The United States’ “rebalance” toward Asia must further assert its military superiority in the South China Sea by constantly engaging and leveraging ASEAN member states’ regional security cooperation and competition against China. This is evidenced by recent U.S.-ASEAN joint maritime drills, in which the United States led joint exercises that included forces from Thailand, Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, and Vietnam. These drills are vitally important, since China’s claims in the South China Sea overlap with those of the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Taiwan, and Brunei, and since the Chinese, U.S., Japanese, and other Southeast Asian navies routinely operate in those disputed waters.23

Hence, a plausible step in strengthening U.S.-ASEAN strategic security cooperation should be the development of a long-term strategic approach that can be cultivated and nurtured in the next decades and centuries for the sake of maintaining peace and order in the Asia-Pacific. Such an approach could soften China’s aggressive moves in the region as well as its ambition to replace the United States as a great power and chief global influencer toward regional security and peace-building among ASEAN members. Similarly, if European nations witness multilateral joint military and maritime exercises being held by the United States and ASEAN nations in the midst of China’s aggression in South China Sea, those nations could be persuaded to pursue their own political and economic interests in the region. This, however, would require a lot of courage and careful planning to form a collective voice on the part of Europe as a whole to cooperate with U.S.-ASEAN strategic military and joint maritime exercises, considering many EU nations’ strong economic ties with China.

It is worth noting that according to a 2019 article in the South China Morning Post, China and ASEAN countries have moved closer to agreeing to a joint code of conduct for the South China Sea, with Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi announcing that “China and the 10 countries of [ASEAN] had completed the first reading of the text to negotiate the code of conduct ahead of schedule.”24 Nevertheless, China constantly upholds its sovereignty in the South China Sea, citing its nine-dash line even though the PCA has ruled that China’s demarcation line has no legal basis under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Therefore, it remains unclear how China and ASEAN communities could settle the issue of the South China Sea disputes, especially when one considers China’s aggressive militarization in the region.

Conclusions

This article has examined the impact of military competition between the United States and China in the South China Sea as it relates to the security of Southeast Asia. Specifically, it has focused on the implications of China’s continuous modern militarization of the South China Sea, evidenced by its building of military installations on artificial islands and reefs. Conflicts regarding freedom of navigation and militarization between the United States and China in strategic waters where Southeast Asian navies operate has spurred increasing tension and compromised ASEAN’s role in the peace and security of the region. Moreover, China’s overlapping claims over the Paracel and Spratly Islands have compromised the safety and security of ASEAN communities, especially as China has become more aggressive in its claims over Taiwan.

This article has also presented several approaches by China and the United States toward military conflict and analyzed the existing military competition between those two nations in the Asia-Pacific region. In sum, U.S. and European approaches toward the Asia-Pacific in general and the South China Sea in particular should not be transactional but rather include long-term strategic engagement of ASEAN countries. Long-term engagement will help compel China to uphold rules-based international order through the stricter implementation of the code of conduct for the South China Sea. Today, there is a dire need to address the development of a concrete transatlantic strategic security policy that involves multilateral joint military backing and constant maritime exercises in the disputed waters.

The United States and China are ultimately constrained in their approaches in engaging in military-to-military cooperation in the Asia-Pacific due to limits set in pursuit of their own national interests and for reasons of evident military competition for great-power status. While the United States views China as challenging its long-standing military dominance in the region, China sees the United States as thwarting its rise to power as it strengthens its own safety and security through the modern militarization over its claims in the South China Sea.

Endnotes

- Donald J. Trump, National Security Strategy of the United States of America, December 2017 (Washington, DC: White House, 2017).

- Edward Wong, “U.S Versus China: A New Era of Great Power Competition, but without Boundaries,” New York Times, 26 June 2019; and Gerry Shih, “China Takes Aim at U.S. and Taiwan in New Military Blueprint,” Washington Post, 24 July 2019.

- Joe McReynolds, “China’s Military Strategy for Network Warfare,” in China’s Evolving Military Strategy, ed. Joe McReynolds (Washington, DC: Jamestown Foundation, 2017), 214–65; and Eric Jacobson and Phil Goldstein, Emerging Challenges in the China-U.S. Strategic Military Relationship Workshop (Livermore, CA: Center for Global Security Research, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, 2017), 6–8, https://doi.org/10.2172/1364740.

- China National Space Administration, China’s Space Activities in 2016 (Beijing: State Council Information Office, 2016).

- Zhao Lei, “PLA Restructures to Meet New Challenges,” China Daily, 11 January 2017.

- Lora Saalman, “Little Grey Men: China and the Ukraine Crisis,” Survival: Global Politics and Strategy 58, no. 6 (November 2016): 135–56, https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2016.1257201.

- Zhuang Pinghui, “China Sees PLA Playing Frontline Role in Cyberspace,” South China Morning Post, 27 December 2016.

- Stephen Burgess, “Confronting China’s Maritime Expansion in the South China Sea,” Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs 3, no. 3 (Fall 2020): 122.

- Ken Jimbo, “U.S. Rebalancing to the Asia-Pacific: A Japanese Perspective,” in The New U.S. Strategy towards Asia: Adapting to the American Pivot, ed. William T. Tow, and Douglas Stuart (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2015), 77–89, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315742434.

- Ash Carter, “The Rebalance and Asia-Pacific Security: Building a Principled Security Network,” Foreign Affairs 95, no. 6 (November/December 2016).

- Office of the Secretary of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China, 2019 (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 2019), iii–iv.

- Steven Lee Myers, “American and Chinese Warships Narrowly Avoid High-Seas Collision,” New York Times, 2 October 2018.

- Edward Wong, “Military Competition in Pacific Endures as Biggest Flash Point Between U.S. and China,” New York Times, 14 November 2018.

- Shih, “China Takes Aim at U.S. and Taiwan in New Military Blueprint.”

- Office of the Secretary of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China, 2019, ii–iii.

- Amy Chang, Ben FitzGerald, and Van Jackson, Shades of Gray: Technology, Strategic Competition, and Stability in Maritime Asia (Washington, DC: Center for a New American Security, 2015).

- “Overview of ASEAN-United States Dialogue Relations,” ASEAN [Association of Southeast Asian Nations] Secretariat’s Information Paper, 17 November 2019; and “Joint Statement of the 22nd EU-ASEAN Ministerial Meeting,” Council of the European Union, 21 January 2019.

- “ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF),” Association of Southeast Asian Nations, accessed 2 November 2020.

- “Note Verbale from the Permanent Mission of the People’s Republic of China to the United Nations to the Secretary-General of the United Nations, No. CML/17/2009,” United Nations, 7 May 2009; and “Note Verbale from the Permanent Mission of the People’s Republic of China to the United Nations to the Secretary-General of the United Nations, No. CML/18/2009,” United Nations, 7 May 2009.

- Robin Emmott, “EU’s Statement on South China Sea Reflects Divisions,” Reuters, 15 July 2016.

- Willard Cheng, “United States Wants Code of Conduct in West Philippine Sea,” ABS-CBN News, 7 November 2019.

- Philippines v. China, PCA Case No. 2013-19 (2016).

- Jesse Johnson, “First U.S.-ASEAN Joint Maritime Drills Kick off as Washington Beefs up Presence in South China Sea,” Japan Times, 2 September 2019.

- Jitsiree Thongnoi, Kyodo, and Reuters, “‘Major Progress’ on South China Sea Code of Conduct Talks Even as Beijing Warns Other Countries against ‘Sowing Distrust’,” South China Morning Post, 31 July 2019.