Patrick O’Brien, PhD; Chip E. Miller, PhD; Col John Flanagan, USMC; and Col Brian Cook, USA (Ret)

3 September 2024

https://doi.org/10.36304/ExpwMCUP.2024.06

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: What must the U.S. military of tomorrow look like? Using the U.S. Marine Corps’ 2024 Commandant’s Professional Reading List (CPRL) as a proxy for what military personnel are being told to know, the authors of this article questioned whether the Marine Corps is ready to envision a future U.S. military capable of Joint, inter-Service, interagency, and multinational multidomain operations. The authors assumed that professional reading lists focus on topics critical to future warfare and professional military education. As a benchmark, the authors have compared the CPRL’s topics to those in U.S. Army general George S. Patton Jr.’s “favorite books” list. Additionally, the authors have compared content in the CPRL to the most recent Annual Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community. This article identifies gaps in the CPRL and consequently the Marine Corps’ ability to envision a future force beyond 2030. The authors suggest categories of books that need to be added to professional reading lists to help prepare the Marine Corps and other U.S. military Services for future warfare.

Keywords: Joint operations, future war, professional reading list, Joint, inter-Service, interagency, multinational, multidomain operations, George S. Patton Jr., Alfred M. Gray Jr.

Introduction

The United States today faces the broadest range of conflicts by type and temporal, technological, and geographic scope—outside of an active world war—in its history. To counter these challenges, within only the past few years the United States has been involved in an expanding number of unilateral, bilateral, trilateral, and multilateral engagements. Three major exercises took place in 2023. That year, the U.S. Air Force’s Air Mobility Command conducted its largest-ever exercise in the Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM) theater, with Australia, Canada, France, Japan, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States participating.[1] Exercise Super Garuda Shield, which had been a bilateral exercise between Indonesia and the United States, was expanded in 2023 to include Australia, Japan, Singapore, France, and the United Kingdom. Approximately 2,100 U.S. and 1,900 Indonesian troops comprised the bulk of forces. The exercise also included more than 10 additional observer nations.[2] Finally, Exercise Talisman Sabre, conducted between the United States and Australia, was one of the largest events held in 2023. This exercise had more multidomain training events than ever before, with more than 35,000 troops involved and more than 10 other nations participated to varying degrees.[3] Additionally, in the past several years, the United States has countered Houthi rebel missile attacks in the Red Sea, sent special forces to 22 African nations, and provided military advice and training to forces in the Philippines, Vietnam, Israel, Ukraine, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan.[4]

The 2024 Annual Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community, published by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, identifies additional perils. These include the rise of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as a global military and economic power; Russia’s ties with the PRC, Iran, and North Korea and its goal of reducing U.S. influence globally by applying military intimidation and leveraging its energy reserves; India’s rise as a major secondary player seemingly aligned with both the United States and Russia; a dangerously unstable nuclear power in North Korea; Iran’s nuclear and regional hegemon desires in the Middle East; widespread terrorism; invisible cyber attackers; and crime syndicates that are able to coerce or topple governments.[5]

There are also additional concerns not listed in the Annual Threat Assessment. These include rising global “influence” activities via social media, often designed to disrupt or destabilize Western democracies; the ongoing conflict between Ukraine and Russia, with Russia pressuring the European Union (EU) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) while gaining support from the PRC; the rapid rise of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies; and dual-purpose commercial technologies that are easily annexed for military purposes.

The need for new and perhaps unorthodox thinking to prepare for future warfare has been consistently highlighted for two decades by papers such as John A. Van Messel’s “Unrestricted Warfare: A Chinese Doctrine for Future Warfare?” and the Rand report China’s Grand Strategy: Trends, Trajectories, and Long-Term Competition.[6] The authors of this article question, however, whether the professional reading lists of the U.S. military Services have stimulated such novel and unorthodox thinking. Table 1 highlights some of the attack vectors that the PRC has identified as offensive avenues of approach, dimensions of grand strategy, or potentially as sources of national power for which defenses must be devised. When one reads Chinese history, not just annual threat assessments or papers without context, the topics on the combined lists are not surprising, new, or unorthodox. For example, references indicating the use in China of ecology as a weapon date back to at least the twelfth century.[7] From a historical view, China’s need and strategies to push U.S. forces from its shores also become obvious.

A driving force behind the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1912, the rise of modern China, and a drastic increase in Chinese nationalism is the “century of humiliation,” a period in Chinese history approximately between 1839 and 1945 during which almost all of the dimensions listed in table 1 came into play.[8] It can be argued that most of these dimensions were used against China by Western powers attempting to carve up and colonize China. During this time, China’s falling behind in the fields of technology and science made it vulnerable to Western nations’ use of military might to demand trade concessions. From a Chinese perspective, opium and religion were used as weapons. “Gunboat diplomacy” was used to enforce imports of both opium and Christian missionaries into China. Smuggling; lawless behavior of Westerners in China; economic weakness; extralegal gang, militia, corporate, and criminal activities; and forced land and economic concessions were the norm. Consequently, many of the methods considered by China in recent years are simply routine historical facts and methods previously used by the West. This emphasizes the need for professional reading lists to provide historical context and demonstrates that the papers by Messel and Rand are not necessarily competing points of view but rather different views of a relatively stable and predictable set of Chinese fears, goals, and strategies. From a U.S. perspective, China is considered a relatively new threat. However, if certain books were included in U.S. military professional reading lists, history would explain that from a Chinese perspective, the West has been a threat for 200 years. Professional reading lists can, therefore, reframe and broaden perspectives and courses of action available to military personnel.

Table 1. Unrestricted warfare attack vectors and Rand’s assessment of the PRC’s vectors of grand strategy

|

Dimension

|

“Unrestricted Warfare”

(Messel, 2004)

|

China’s Grand Strategy

(Rand, 2020)

|

|

Trade

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

Financial

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

Terrorism

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Ecological

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

Smuggling

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Cultural/information operations

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Illicit drugs

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Media

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

Science and technology

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

Natural resources

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

Psychological

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

Information technology network

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

International law

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Environmental

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

Economic

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

Military/Joint operations

|

No

|

Yes

|

Source: courtesy of the authors.

The Historical Value of Professional Reading Lists

The value of professional reading has been recognized for millennia. The Chinese general and military strategist Sun Tzu is credited with writing the oldest known treatise on warfare in the fifth century BCE. His work produced commentaries from China’s greatest combat commanders fighting existential wars. The warlord Cao Cao, who spent 40 of his 65 years of life (155–220) actively at war, commented on Sun Tzu: “Many books have I read on the subject of war and fighting, but the work composed by Sun Wu is the profoundest of them all.”[9] In Cao Cao’s time, losing meant that entire armies, commanders, and their families, to nine degrees of separation, might be slaughtered. The stakes today might be just as high. The current proxy war in the Middle East being waged against Israel—and, by default, the West—has the potential to spread globally. Likewise, a possible theater war in the Pacific could engulf the Philippines, Southeast Asia, Australia, Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea.

Reviewing history further, the Greek historian Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War, the Roman general Julius Caesar’s Commentaries on the Gallic Wars, and the Byzantine emperor Maurice’s Strategicon are all intended as instructions on warfare. More recently, the U.S. military historian Roger H. Nye studied the library of U.S. Army general George S. Patton Jr. extensively.[10] He found works by Sun Tzu, Thucydides, Caesar, and Maurice in Patton’s library. Nye also recommended a professional reading list for U.S. military officers. Implementation of his approach relied on individuals reading books and on commanders holding discussions of the books with the members of their units. Nye wrote, “Inquiring soldiers, by definition, are determined to expand their universe through reading.”[11]

Nye also asked an important question: “How does a mentor know if he is preparing his people for the kind of warfare they are most likely to fight?”[12] This query is pertinent to answering the question of what the U.S. military of tomorrow should look like. To answer his own question, Nye offered nine categories of knowledge that soldiers should study:

-

Visions of our military selves

-

The challenges of the commander

-

The company commander

-

The commander as tactician

-

The commander as warrior

-

The commander as moral arbiter

-

The commander’s concept of duty

-

The commander as strategist

-

The commander as mentor

More recently, Erika Tarzi’s report on reorienting the professional education of U.S. Marines illuminates two critical factors.[13] The first is that failing to be lifelong learners and to apply professional knowledge leads to potential failure in the military profession. Moreover, learners must think strategically and be reflective. The second, relating to the current pace of change in warfare and its complexities, is that problems do not present as well-formed structures but rather as indeterminate situations. Leaders must translate thinking into action and apply “metaknowledge” to affect a solution. While the fields of metaknowledge and metacognition are broad, they can roughly be summarized as knowledge about knowledge, thinking about knowledge, and thinking about how one goes about formulating better approximations of truth and thereby better responses to the realities of a situation. In a military context, this is not simply executing doctrine or the military decision-making process methodically. Rather, is a self-reflecting, self-assessing, and self-aware red-teaming of what one knows, what one does not know, and how one approaches the path to making better decisions and creating better outcomes.[14] Military professional reading lists should exist to promote metaknowledge and metacognitive processes beyond simply mimicking doctrine. Some content and processes are better at achieving this than others.

A Point of View on Cognitive Readiness for Future War and Professional Reading Lists

Whatever these content and processes are ultimately determined to be, the authors of this article posit that military personnel across the force—not just think tanks—should be involved in the development and execution of plans for future engagements. Professional reading lists are a readily accessible means for involving military personnel and helping them think about doctrine, future scenarios, possible worlds, and wars. Future wars may not unfold as slowly or predictably as in the past. Conflicts may erupt with minimal warning or declaration, making the blitzkrieg of World War II look like sitzkrieg. Military personnel will have less time to begin reading about adversaries after a war starts as they did during recent counterinsurgency operations in the Middle East. Additionally, there is no mistaking the desire for regional or global domination that is currently driving the leaders of Russia, the PRC, North Korea, and Iran. Ensuring that U.S. professional reading lists keep pace with the United States’ most likely adversaries, and understanding their mindset, is essential for national security.

One feature of a U.S. military professional reading list is that it allows access for all servicemembers, so keeping them as open-source lists is important. As technology continues to evolve, open-source professional reading lists can become beneficial on an even larger scale. Military journals should also have the freedom to use peer review processes as desired or, alternatively, if dealing with a fast-moving, time sensitive topic, publishing without peer review.

As will be seen in this article’s analysis of Patton’s reading, it may also be the case that books published by popular publishing companies designed for mass sales to, and for gleaning profit from, the general public may not meet the needs of professional warriors. Books written by military professionals for military professionals without a profit motive “watering down” the content may be needed to be included in professional reading lists. It takes decades of in-depth study to accumulate knowledge of tactics, operations, and strategy to prepare one for command of a Marine expeditionary force, an Army corps, or a Navy task force. Developing such complex thinking cannot be scheduled during occasional one- or two-year assignments to military Service schools alone. As a result, books written by professional warriors to develop professional warriors will be needed.

Major competitors and potential enemies of the United States are not standing idly by but are publishing their own military reading material. The thinking of U.S. military personnel must keep pace. The PRC, for example, published a book on integrated grand strategy in 1999—Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui’s Unrestricted Warfare—and updated it in 2016.[15] Rand’s assessment of the PRC’s grand strategy based on multiple Chinese language sources emphasizes that the PRC has been focused on developing joint operational capabilities since at least 2016. Rand also concludes that the PRC’s grand strategy is comprised of dimensions and concerns such as those published by Qiao and Wang and summarized by Messel. This article does not make the sensational claim that Qiao and Wang’s book is the PRC’s “master plan to destroy America” or the end-all, be-all book describing the PRC’s grand strategy, or that the PRC plans to or would even endorse using all the means listed. Still, the job of a strategist is to imagine all the most likely, most dangerous, or other key unorthodox courses of action that one can use or might see used against one’s nation. Such references provide insights into the thought processes of PRC strategists. Joshua Baugman recommends the PRC’s Science of Military Strategy.[16] Rush Doshi suggests three vectors—military, political, and economic—which he believes are designed to “blunt” U.S. diplomat George F. Kennan’s Cold War strategy to contain the Soviet Union and which the PRC foresees the United States using against it.[17]

Furthermore, while English-language searches through book retailers such as Amazon produce few books on Chinese military thinking, entering Chinese terms for military strategy, strategy, military tactics, or active defense generates a sizable list of books written or translated into Chinese. Topics include strategic innovation, great power strategy, memoirs of a PRC diplomat’s perspective on the PRC’s strategy in the South China Sea and North Korea’s nuclear threat, active defense, PRC cybersecurity methods, a PRC analysis of U.S. naval historian Alfred Thayer Mahan’s naval strategy, and a PRC-authored book on the rise and fall of seapower.[18] Likewise, the subject of land warfare is covered by more than Mao’s Zedong’s Little Red Book of quotations, with extant Chinese-language books on the Argentine Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara, David Kilcullen, historical records of Chinese Communist guerrilla actions in Hunan during the Chinese Civil War, the German Army general Heinz Guderian, and World War II-era German Army combat commands.[19]

Future warfare is also addressed. One can find books covering U.S. deep-strike technology and U.S. net-centric operations.[20] In April 2024, the U.S. chief of space operations, General B. Chance Saltzman, stated that the PRC’s space capabilities are advancing at “breathtaking speeds.”[21] Two days later, the press reported that the PRC had announced a major reorganization of its military, part of which emphasizes “joint” operations.[22] The authors of this article agree that the PRC is a pacing nation for the future force development of the U.S. Marine Corps and that it is not the only adversary studying U.S. and other military competitors.[23] The 2024 Annual Threat Assessment also identifies Russia, Iran, and North Korea as state actors who the U.S. military must consider when planning future Joint operations. Strangely, the United States’ 2022 National Security Strategy only identifies the PRC as being a “concern” 7 times, compared to Russia’s 71 mentions or Iran’s 7 mentions.[24] This document seems misaligned with the current Annual Threat Assessment, and the Marine Corps’ 2024 Commandant’s Professional Reading List (CPRL) is largely inconsistent with both documents.

The PRC is, however, of particular interest to the Marine Corps. The Pacific theater of World War II saw the most prolific use of Joint operations of all theater-level wars in U.S. history, and any future war in the INDOPACOM theater will likely require multidomain operations (MDO) and Joint, inter-Service, interagency, and multinational (JIIM) cooperation across all U.S. military Services, intelligence agencies, industries, and commercial logistics capabilities, as well as with multiple other nations and their various treaties and status of forces agreements. The U.S. military should expect challenges exceeding those in World War II, including technology interoperability, languages spoken, culture, geography, weather, national will, nations’ competing and conflicting national goals, and more.

The above paragraphs provide a look at one potential U.S. adversary, the PRC. Similar concerns exist regarding whether Russia, Iran, North Korea, and other threats mentioned in the Annual Threat Assessment are addressed well enough to inform the design of a future U.S. JIIM/MDO force. To help address such regional studies, the Marine Corps had a Center for Advanced Operational Culture Learning from 2006 to 2020, which provided quality documents that were helpful in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The reduction of this capability may prove to be short-sighted given the multitude of threats the United States now faces. For example, how the United States assesses the use of “soft power” by Iran may not be fully understood, and having such a culture learning center could provide insights and red team views for the long run. In the meantime, the absence of such sources of cultural knowledge means that military professional reading lists will have to carry this educational burden alone.

Answering the Future Military Question

The future of MDO and JIIM can be predicted to some degree based on the question raised earlier in this article: What must the U.S. military of tomorrow look like? Changes in technology, adversary culture, alliances, and the speed of warfare will all affect how a future force is reshaped. The United States’ competitors study the nation closely and answer that same question for their military forces. This article examines how well the United States is studying its competitors, warcraft, technology, and other factors that determine victory or loss, and how well U.S. stakeholders are prepared to answer this question. Because a professional reading list provides insights into the official focus of the U.S. Marine Corps, the authors of this article chose to evaluate the subjects of books included in the 2024 CPRL. Articles in military-related publications such as the Marine Corps Gazette and the U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings may identify key issues and offer perceptions, but they do not always provide the detailed, comprehensive analysis that is possible in books and may not reflect the focus of Headquarters Marine Corps as does the CPRL.[25]

The CPRL was chosen as a point of reference here because it is a mechanism that the highest authority in the Marine Corps uses to direct the attention of its personnel. Additionally, while advanced schools such as the U.S. military war colleges may answer the future force design question, especially beyond 2030, the professional reading lists reflect how these concepts are being “mainstreamed” and how all hands are being prepared to think conceptually and make complex decisions when situations demand it. Professional reading lists also implicitly state: “This is what we want you to know, what we think you do not already know, and what we expect of you.” Professional reading lists also provide an opportunity for a complementary style of learning, a style on which Patton relied extensively. This is the use of inductive learning by the method of case studies, which can augment learning rule- and methodology-based doctrine deductively as taught in the Service schools. This article explores whether the CPRL and other professional reading lists provide this complementary opportunity for inductive learning by reading about the successes and failures of military commanders.

U.S. strategy and doctrine should not be stagnant but arise from lessons learned from the experience of others. Ultimately, they are for the most part derived through inductive learning. Consequently, answering the question of what the U.S. military of tomorrow should look like requires visionaries to avoid being near-sighted. Additionally, U.S. strategy should include and perhaps even go beyond the classical perspectives of Western strategists and warfighters such as Carl von Clausewitz, Antoine-Henri de Jomini, or B. H. Liddell Hart, particularly in light of technological advances unknown to these authors.[26] Strategy beyond the perspectives and methods of Cold War-era strategists such as George F. Kennan may also be needed. Kennan is particularly relevant in this case, as the U.S. military’s role in his strategy is to support the main effort of achieving peace by maintaining Niccolò Machiavelli’s balance of power among mutually supporting self-interested states.[27]

The PRC is not the only nation seeking a new balance among mutually supporting states. Many nations today are adept at wielding power just below the threshold of armed conflict, seeking to change the current balance of power. As more nations adopt this approach, the threshold for crossing into armed conflict is likely not triggered by the attacking nation(s). Instead, a rational or irrational actor or even a proxy could precipitate an international crisis of great scale. In this new paradigm adapted for a connected, globalized world, nations are simultaneously shaking hands on trade agreements while their forces are advising, arming, and helping proxies fight worldwide. Trade and violent competition using entities operating in and out of the “gray zone” happen simultaneously.[28] One example of this is that member nations of the EU continue to use Russian fossil fuels while simultaneously arming Ukraine in its war with Russia.[29] In an old-school, conventional war scenario, Russian pipelines, and EU factories using them, would be targeted. In today’s world, however, a nation might protect such resources one day and destroy them the next. Additionally, a small raid on a pipeline might also be strategic in impact. Tactical and strategic actions often merge in today’s scenarios.

Even capabilities for kinetic action have changed dramatically. In future conflicts, it may be difficult to hide forces, or their intentions, and there will likely not be any sanctuary. It may also no longer be valid to think of a “rear area” in military operations. The depth of Russia’s current concept of deep battle includes strategic actions to destroy critically important targets. Combat actions may reach across Europe and North America to preemptively strike critical aerospace, communications, and other assets.[30] Likewise, the depth of the PRC’s strategy ranges from active defense in the Asia-Pacific to a global MDO to influence and attack enemy assets worldwide and in space.[31] The picture is clear—the United States must compete in all domains beyond common borders and boundaries.[32] Deep-strike electromagnetic and cyber weapons, ground- and space-based weapons designed to destroy communications satellites, and hypersonic weapons make the “rear area” part of the front.[33] Consequently, while one nation marches on another, a modern-day Scipio Africanus could be ravaging that nation’s homeland with cyber weapons, electromagnetic pulse weapons, influence operations, and more.

Still, one cannot say that maneuver warfare as envisioned by Lester W. Grau and Charles K. Bartles is gone, as it could erupt along NATO’s eastern front at any time.[34] Neither is World War I-style trench warfare gone, as is evident in Ukraine today. All types of warfare and skirmishes are happening or could happen somewhere in the world at any time, possibly simultaneously. This could occur at the speed of AI by the U.S. Air Force’s concept of Mosaic Warfare.[35] A high-technology vision for future war may even change the traditional roles of the various U.S. military Services. Today, even a small Marine expeditionary unit (MEU) equipped with a Tomahawk missile battery can deliver tactical, operational, and strategic blows.[36] From forward locations, a MEU can strike targets at great distances. Likewise, from positions in the Middle East and Africa, a MEU could strike Houthis in Yemen to protect allied or partner fleets operating in the Red Sea.

These scenarios and others are accounted for in U.S. multidomain concepts of operation but seem to move slowly into mainstream military thinking as reflected in current professional reading lists. Additional books in professional reading lists must address these new developments in warfighting and how the various levels of command should reshape their thinking to both employ these tools and defend against them. More emphasis is needed on Joint operations and inter-Service cooperation instead of parochial perspectives. Joint MDO needs to be better understood to support U.S. diplomacy and strategy through “integrated deterrence” and the continuum of competition.[37] A future major theater-level war will be a JIIM effort, especially when even a MEU can deliver the level of destruction previously controlled only by more strategic levels of command. Professional reading lists must address how the destructive power of new technology can be best coordinated and optimized at lower levels of command and in the context of a Joint force. In short, the Services should constantly update their professional reading lists so that they can be used as tools to prepare warfighters to think and act as a Joint MDO force at levels of metacognition and knowledge.

General Patton’s Professional Reading List, Topics, and Method of Study

The initial foray into answering the question of what the U.S. military of tomorrow should look like, and to create the level of thinking discussed above, was to explore how Patton achieved this same goal. This was done by comparing the 2024 CPRL to Patton’s “favorite books.” The methodology used here is that of an exploratory case study. Patton is one of the best examples of a military leader preparing for future war. He is legendary for intentionally using professional reading to make himself an exceptional combat commander and general officer in a theater-level war. He also had a well-documented library, and the knowledge he gleaned from reading was tested in the U.S. expedition in Mexico in 1916, in World War I, and in World War II. As the commander of several U.S. field armies during World War II, he was challenged in all phases of warfare, from forced entry to security and stability operations in a high-intensity, high-technology (for the day), and rapidly changing theater-level war against a peer enemy. During his military career (1909–45), Patton had to transition from conducting Napoleonic-style cavalry saber charges and arguing over whether the cavalry saber should be curved or straight to leading JIIM operations, employing combined arms, and conducting maneuver warfare using modern weapons. This transition included the use of deep-strike bombing on German reinforcements and on Germany’s industrial base, psychological and deception operations, and close air support; the introduction of radar, radio direction finders, and previously unimagined signal intelligence, communications intelligence, image intelligence, and intelligence support; and the actions of partisans and insurgents. In Patton’s day, there was an analog for everything that U.S. forces would face (except for space warfare) in future wars.

James C. Madigan attributes Patton’s insights to his voracious reading habits and an extensive collection of works on the art of war:

Patton was taught and learned that history is replete with examples on how to understand the military profession and to improve his knowledge, skill, and ability. . . . A large portion of his success can be directly attributed to his self-development practices. He followed the tenets of read, think, discuss, and write about professional subjects.[38]

This, however, understates the efforts to which Patton went to develop his warfighting knowledge. Roger H. Nye and Beatrice Ayer Patton, Patton’s wife, argue that Patton not only read books but also cross-referenced books on note cards and created a complex web of knowledge.[39] Beatrice Patton adds that some vacations were spent walking battlefields and having the entire family perform maneuver exercises, acting out actual battles on the battlefields where they were fought. She also states that her husband had her translate potential enemies’ books from German to English, giving the German historian Heinrich von Treitschke’s writings as an example. Nye’s inventory of Patton’s library shows that it included German Army field marshal Erwin Rommel’s Attacks in German.[40] This book was not available in English until 1944, and an unabridged translation was not available until 1979.[41] This means that the majority of U.S. military officers who could not read German would not have read the book until after Rommel’s death in October 1944. Likewise, Patton’s diaries mention him and his wife reading and translating French books into English.[42] Nye’s inventory of Patton’s library contains 19 French-language books on warfare. Today, the equivalent method of study would be for U.S. military officers to learn Russian and Chinese and to translate Russian and Chinese books into English to better understand their potential adversaries and allies.

Patton also faced the most rapid transition in military technology, doctrine, and scope in history up to that time, all during a “hot” war. In preparation for this monumental evolution, he was directly involved in U.S. Army innovation. During the U.S. expedition in Mexico against the revolutionary Pancho Villa, Patton invented the United States’ first motorized assault in actions against Villa’s paramilitary forces. In World War I, he was the first officer assigned to the United States’ first tank corps.[43] Martin Blumenson writes that he exposed himself to enemy fire and rode a tank into battle to observe and understand the impact that tanks had on the enemy and to obtain a vantage point from which to observe tank-infantry operations.[44] During the interwar years, Patton worked on developing tank doctrine and concepts for combined arms operations. When World War II arrived, he successfully implemented his theories of maneuver and armored warfare on the battlefields of North Africa, Italy, and Western Europe.

During this period, Patton transitioned from a saber-armed horse cavalry officer to a commander of field army-level JIIM operations, a practitioner of combined arms, and arguably an architect of early multidomain operations. Indeed, Spencer L. French argues that Patton’s experiments in signals intelligence and information services while in command of the U.S. Third Army offer a model for “fielding new and experimental multidomain effects formations.”[45] Design, experiment, and apply should be added to Madigan’s tenets of read, think, discuss, and write that he applied to Patton.

Patton was also noted for being able to express his intent as a commander to his staff and then leave to perform his own reconnaissance in person. He did not, however, leave his staff’s results to chance. Jörg Muth writes that the German General Staff School trained officers so well that they could act with mission-oriented orders of only a few lines instead of detailed operations instructions.[46] German officers were able and trusted to devise a plan independently. Contrariwise, Muth states that only four U.S. Army general officers applied a comparable method of training and commanding their subordinates: George C. Marshall Jr., Patton, Mathew B. Ridgeway, and Terry de la Mesa Allen. The effectiveness of Patton’s Third Army in Western Europe suggests that he developed in his commanders and staff the same metaknowledge he possessed. Consequently, Patton became for this article the benchmark for using professional reading lists to answer the question of what the U.S. military of tomorrow should look like. The elements that contributed to Patton’s successes, the methods he used to develop himself, and his well-documented library are why his favorite books are the standard against which the CPRL is compared.

General Gray’s Original Professional Reading List Concept

“Want a new idea—read an old book.” This quotation, which appears in Paul Ott’s compilation of thoughts from U.S. Marine Corps general Alfred M. Gray Jr., is one of the many aphorisms that Gray had for warfighters.[47] A strong believer in extensive professional reading, Gray published a professional reading list for the 2d Marine Division while serving as its commanding general in 1981 and the first CPRL for the entire Marine Corps while serving as commandant in 1989. Gray was aware of the German Army’s pre-Nazi-era command and staff training methods and brought in subject matter experts to teach and implement these methods to personnel of the 2d Marine Division. This program included discussion groups consisting of battalion officers and led by battalion commanders. Gray also brought the U.S. military theorist John R. Boyd to the 2d Marine Division to teach his “OODA (observe, orient, decide, act) loop” concept and deliver his “Patterns of Conflict” presentation.[48] Experts in democratic and participative decision making were also brought to the division and deployed on ships with MEUs.[49] The process of openly debating the books on Gray’s professional reading list by officers of the division was as important as the content of the books themselves. The German method of training commanders and staff had all ranks, from second lieutenant to field marshal, discuss and debate case studies of battles, campaigns, strategies, and doctrine. As implemented in the Marine Corps, books were read and debated. Platoon commanders were encouraged to disseminate the content to and use the same methods with their platoons.[50]

Gray’s new ideas emerged because simulations built by military operations analysts showed that in a high-intensity conflict with the Soviet Union, there would be high casualty rates among officers and senior noncommissioned officers in the initial stages of conflict. Frontline unit leaders needed to be able to think and fight not only tactically but also strategically. Gray’s innovative approach provided more than just a list of books published every four years and updated now and again. He adopted Patton’s methods and expanded them to include noncommissioned officer in his division. In the 1980s, two of the authors of this article participated in these sessions. All officers and senior noncommissioned officers participated in in-depth reading and discussion of historical campaigns.

Patton’s Favorite Books versus the 2024 Commandant’s Professional Reading List: The Evaluation Approach

The authors of this article gathered Patton’s favorite books and the 2024 CPRL and coded the books’ attributes, as shown in table 2. The books were also classified by the authors’ own attributes and categorization schemes, as explained in tables 3 and 4. A search for literature discovered very few attempts to categorize and analyze the content of the professional reading lists. Lisa M. Beck performed a similar analysis using an apparently subjective book classification scheme but provided no operational definitions for including or excluding a book from a category.[51] Consequently, her scheme could not be replicated here. Beck also pooled lists across military Services and did not compare lists and topics across lists as in the analysis in this article. Thomas E. Ricks, Olivia Garard, and a few others provide short articles and criticisms of professional reading lists that feature undefined classification schemes, minimal counts and analysis, and a few criticisms of various professional reading lists.[52] None of these works provided operationalized, replicable definitions of categories, topics, subjects, or genres. They provide minimal analysis relative to the purpose of professional reading lists. None compare professional reading lists or provide a taxonomy and variables that are usable across the various Services’ professional reading lists over time.

There are no tried and tested taxonomies with established levels of interrater reliability, nor are there previous studies with established content-, construct-, concurrent-, or criterion-related validity. In reviewing almost all the U.S. military Services’ prior professional reading list, the authors found that they use different classification schemes and generally malformed taxonomies to classify their books. Even different book publishers classified book subjects differently or not at all. Consequently, the authors view this analysis as being at the beginning case-study level of research and theory building. A unique classification scheme has been devised based on themes that seem to emerge from the naturally occurring topics across books. This is an exploratory means of analyzing professional reading lists as case studies, and it recognizes that over time, interrater reliability studies, use of natural language processing, supervised and unsupervised machine learning, and other methods will be needed to operationally define and create variables and taxonomy for more formal analyses. Variables and classifications that seemed likely candidates for discriminating Patton’s favorite books from the books on the CPRL and that seemed to have face validity were chosen. For instance, books were delineated by whether they were written by people who commanded forces at war versus motivational speakers; whether they were identified by commanders who motivated armies and nations at a time of war; and whether they help the reader understand one’s enemies.

Once the books were coded, descriptive statistics comparing Patton’s favorite books to the CPRL were generated and reported in the results section. The logic of the case selection (Patton versus CPRL) centered on the choice of a proven winner of campaigns (Patton) during a theater-level war. On the face of it, Patton’s professional reading prepared him for success. Next, the authors explored the question: What attributes of Patton’s reading might have been essential to his success, and are the same attributes present in current professional reading lists? As a case study, this method outlined here does not reach the level of a pure or quasi-experiment, nor does it even reach the level of a correlational analysis. It is an exploratory comparison of two professional reading lists as case studies and lays the groundwork for more formal analyses. It does, however, raises an important question: are we reading the right stuff?

Table 2. Coded book attributes

|

Book attribute

|

Definition and rationale

|

|

Whether the book subject was a head of state

|

Measures how many heads of state in command of both grand strategy and military forces are being studied.

|

|

Whether the book’s author was a head of state

|

Measures whether the author was or attained the status of head of state with the perspectives, experiences, and responsibilities of that position compared to a person with less experience and responsibility for getting grand strategy right.

|

|

Whether the book’s subject was a general/flag officer

|

Measures how many combatant commanders of general/flag officer rank with the responsibility of getting military strategy right are being studied.

|

|

Whether the book’s author was a general/flag officer

|

Measures whether the author was, or attained, the rank of general/flag officer with the perspectives, experiences, and responsibilities of that position.

|

|

Whether the book’s subject had prior military experience

|

Measures the number of subjects with prior military experience as compared to subjects who were diplomats, professors, or members of professions other than the profession of arms.

|

|

Whether the author was a war correspondent

|

There are other ways of experiencing the realities and gaining breadth and depth of perspective on war. Some authors were embedded with military units and had firsthand knowledge of the events about which they wrote. This measures whether an author had such opportunities. We deemed them to have a different perspective compared to people writing from secondary sources rather than from first-hand experiences.

|

|

The nationality of the author

|

Measures how many authors were not Americans. We judged this to be a measure seeking others’, perhaps potential or current enemies’, perspectives.

|

|

Whether a book was a memoir

|

Mrs. Patton stated that Gen Patton preferred to read memoirs and authoritative biographies. This measures the number of books that were memoirs.

|

Source: courtesy of the authors.

Coding books by their subject categories was fraught with difficulties. Publishers’ book descriptions were often at too high a level and generally failed to identify significant differences among books. On the other hand, very granular classification schemes became unwieldy for discussion in anything less than a book of several hundred pages. Consequently, a categorization scheme had to be devised to cover book topics, as shown in table 3.

While some books were clearly single-category books, many could legitimately be placed into two or more categories. A book such as Sir Ian Hamilton’s account of the Gallipoli campaign in World War I is a history, an after-action review, a biography, a memoir, and a book on strategy and planning. To reduce complexity, most books were assigned to a single category. No books were coded into three or more categories.

Table 3. Book categories created for this article

|

Book categories

|

Topic definition/example

|

|

Leaders and leadership

|

Leaders (biographies and memoirs), combat leadership, command and decision making, high-level leadership, and transformative leadership.

|

|

Strategy

|

Strategy at all levels, including the operational and theater level, different categories of strategy (maritime, space, national, etc.), and grand strategy.

|

|

Warfighting (military Services only)

|

Operationally implementing all types of strategy: command and control efforts, planning, doctrine, tactics, techniques, procedures, training and training exercises, experimentation, professional military education. In short, the content of the various military Services’ universal task lists and the conduct of war.

|

|

Innovation, futures, and future fiction

|

Imagining future scenarios and technologies and how these will change the nature and conduct of war. For example, AI-enabled warfare, space-based weapons, genetically targeted weapons, weaponization of social media.

|

|

Culture, values, and history

|

The United States, U.S. allies, and potential U.S. adversaries’ histories, values, goals, objectives, concerns, ways and means, what each stands for, and what each believes is a vital interest.

|

|

Geopolitics and diplomacy

|

Geographical, geopolitical, and diplomatic international relationships, world systems, trade routes, alliances, networks, aligned and conflicting interests, diplomatic efforts, factors leading to conflicts, and factors that affect strategy and warfighting.

|

|

Challenges, threats, and adversaries

|

Current and future challenges and threats to general geopolitical factors mentioned above. Includes discussions of how known or potential adversaries will use economics, trade, conventional military actions, warfare in the gray zone, proxy wars, terrorism, and general methods of projecting power.

|

|

Economics, industry, and logistics

|

Producing material support and mobilizing for a war. This includes involving the industrial base, supporting a war effort financially, the economies of the United States and other nations, and creating the manufacturing, medical support, and logistics trains/methods required to sustain a war effort.

|

|

Joint and combined warfighting

|

Creating Joint, combined, inter-Service, interagency, and multinational war efforts; working with allies; understanding other military cultures; treaties and bilateral agreements; the status of forces agreements; rules of engagement; chains of command in a JIIM environment; etc.

|

|

Historical fiction

|

Fictional accounts of past events or periods of time were removed from the analysis. Future-looking fiction is included in “Innovation, Futures, and Future Fiction.”

|

Source: courtesy of the authors.

After the books were coded, descriptive statistics were computed to quantify the number of books in each category for Patton’s favorite books, the 2024 CPRL, and The Leader’s Bookshelf, a book about the reading habits and favorite books of military general/flag officers by retired U.S. Navy admiral James Stavridis and R. Manning Ancell.[53] Because The Leader’s Bookshelf is listed in the CPRL and contains a list of recommended books, it has been coded as a professional reading list of 50 good books. By including The Leader’s Bookshelf book in the CPRL, it becomes a professional reading list within a professional reading list. The CPRL is inclusive of both lists, but for visibility the books in The Leader’s Bookshelf are reported on separately. The Leader’s Bookshelf also discusses the importance of Patton’s library and indicates that it was more extensive than that of General Marshall. This standard of including professional reading lists within professional reading lists as an extension of the parent professional reading list is necessary for future analysis since the current U.S. Army chief of staff’s professional reading list includes Roger H. Nye’s professional reading list. This decision establishes a common method for handling any professional reading lists that are comprised of two or more professional reading lists.

Results of Professional Reading List Assessments: Book Characteristics

As I read the books coming out of this last war [World War II], I know those that he [General Patton] would choose: authoritative biographies and personal memoirs of the writer, whether he be friend or enemy. No digests!

~ Beatrice Ayer Patton[54]

Patton’s list of favorite books contains 123 books; The Leader’s Bookshelf contains 50 books; and the CPRL contains 46 books. Therefore, the total CPRL is 96 books. Table 4 shows some descriptive statistics comparing the three professional reading lists. As it happens, many of Patton’s books are about and/or written by general/flag officers and heads of state. These books are about and by people who had succeeded and/or failed at the tactical, operational, strategic, and in some cases grand strategic levels of command. Ninety-five (77 percent) of Patton’s authors had military experience. Ninety-nine (80 percent) were foreign, thereby providing non-American perspectives. Five books (4 percent) are by Patton’s future enemies—Germans—four of whom were general/flag officers. Only 17 percent of the authors appearing on the CPRL and in The Leader’s Bookshelf were not American. Forty-six percent of these authors had prior military service, half of whom were Marines. Neither The Leader’s Bookshelf nor the CPRL includes books written by potential enemies of the United States.

Table 4. Comparison of book attributes

|

Book attributes

|

Patton’s favorite books

|

The Leader’s Bookshelf

|

CPRL

|

Total CPRL

|

|

Count (percent) of books about heads of state

|

17 (14 percent)

|

12 (25 percent)

|

0 (0 percent)

|

12 (13 percent)

|

|

U.S. head of state to foreign heads of state, subjects

|

1 U.S., 16 foreign

|

9 U.S., 3 foreign

|

0 U.S., 0 foreign

|

9 U.S., 3 foreign

|

|

Count (percent) of books about general/flag officers

|

29 (24 percent)

|

12 (32 percent)

|

5 (11 percent)

|

17 (18 percent)

|

|

Count of books about U.S. general/flag officers to foreign general/flag officers, subjects

|

8 U.S., 21 foreign

|

7 U.S., 5 foreign

|

3 U.S., 2 foreign

|

10 U.S. to 7 foreign

|

|

Count (percent) of books authored by heads of state

|

25 (20 percent)

|

2 (5 percent)

|

0 (0 percent)

|

2 (2 percent)

|

|

U.S. heads of state to foreign heads of state, authors

|

2 U.S., 23 foreign

|

2 U.S., 0 foreign

|

0 U.S., 0 foreign

|

2 U.S., 0 foreign

|

|

Count (percent) of books authored by general/flag officers

|

48 (39 percent)

|

10 (26 percent)

|

5 (11 percent)

|

15 (16 percent)

|

|

U.S. general/flag officers to foreign general/flag officers, authors

|

20 U.S., 28 foreign

|

5 U.S., 5 foreign

|

4 U.S., 1 foreign

|

9 U.S., 6 foreign

|

|

Count (percent) of books by foreign authors

|

99 (80 percent)

|

11 (26 percent)

|

5 (11 percent)

|

16 (17 percent)

|

|

Count (percent) of books with prior military service authors

|

95 (77 percent)

|

28 (74 percent)

|

21 (46 percent)

|

49 (52 percent)

|

|

Count (percent) of books with war correspondent authors

|

28 (23 percent)

|

8 (21 percent)

|

3 (7 percent)

|

11 (12 percent)

|

|

Count (percent) of books with military authors who were U.S. Marines

|

0 (0 percent)

|

5 (18 percent)

|

11 (52 percent)

|

16 (17 percent)

|

|

*The total page count of Rudyard Kipling’s writings is unknown. Consequently, to compare apples to apples, numbers have been computed using counts without historical fiction unless otherwise noted.

Source: courtesy of the authors.

|

Table 5 shows more detail about the authors of Patton’s favorite books. Fifteen authors were general/flag officers; all had seen combat and had commanded units of division-size or larger in combat. An additional six authors had military experience and at least one, B. H. Liddell-Hart, had seen combat. Winston S. Churchill never became a general/flag officer; he attained the rank of colonel in the British Army. He was, however, the United Kingdom’s First Lord of the Admiralty.

Three authors of Patton’s favorite books had been war correspondents. Julius Caesar’s commentaries are considered here as war correspondence. Churchill, when not on active duty, found his way to the front as a war correspondent. The authors on Patton’s list came from 10 nations, compared to 16 nations for the combined list of the CPRL and The Leader’s Bookshelf.

Table 5. List of authors by nationality and other attributes for Patton’s favorite books

|

Author

|

Number of books

|

Nationality

|

Head of state

(yes/no)

|

General/flag officer (yes/no)

|

Military experience (yes/no)

|

War

correspondent (yes/no)

|

|

Charles W. C. Oman

|

22

|

British

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

Winston S. Churchill

|

21

|

British

|

Yes

|

No

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

B. H. Liddell Hart

|

19

|

British

|

No

|

No

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Alfred T. Mahan

|

18

|

American

|

No

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

J. F. C. Fuller

|

14

|

British

|

No

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Douglas S. Freeman

|

2

|

American

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

Arthur C. Bryant

|

2

|

British

|

No

|

No

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Ulysses S. Grant

|

1

|

American

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Maurice of Byzantium

|

1

|

Byzantium

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Julius Caesar

|

1

|

Roman

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

Paul von Hindenburg

|

1

|

German

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Hans von Seeckt

|

1

|

German

|

No

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Antoine-Henri de Jomini

|

1

|

Swiss

|

No

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Thucydides

|

1

|

Greek

|

No

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Alfred von Schlieffen

|

1

|

German

|

No

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

George B. McClellan

|

1

|

American

|

No

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Ian Hamilton

|

1

|

British

|

No

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Erich Ludendorff

|

1

|

German

|

No

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Ferdinand Foch

|

1

|

French

|

No

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Baron de Marbot

|

1

|

French

|

No

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

G. F. R. Henderson

|

1

|

British

|

No

|

No

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Niccolò Machiavelli

|

1

|

Italian

|

No

|

No

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

L. A. F. de Bourienne

|

1

|

French

|

No

|

No

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

William Sloane

|

1

|

American

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

Heinrich von Treitschke

|

1

|

German

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

Harold Lamb

|

1

|

American

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

Gustave

Le Bon

|

1

|

French

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

Edward Gibbon

|

1

|

British

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

Edward Creasy

|

1

|

British

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

Arthur Weigall

|

1

|

British

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

Carl Gustaf Klingspor

|

1

|

Swiss

|

Unknown

|

Unknown

|

Unknown

|

Unknown

|

|

Column totals (yes)

|

123*

|

10 Countries

|

5

|

15

|

21

|

3

|

*Rudyard Kipling is not included in this count. His works of fiction have been removed, but he did not only write fiction regarding the war in India. The number of dispatches he may have written is unknown.

Source: courtesy of the authors.

Book Categorizations

The development of book categories occurred after compiling and reading all of the U.S. military Services’ professional reading lists. Categories were created with an eye toward future analyses requiring a common taxonomy to allow an apples-to-apples comparison of professional reading lists. The categorization of books is currently subjective, as noted in the earlier discussion on methods. This will need to be addressed moving forward. In the future, applying natural language processing and unsupervised machine learning will likely be necessary. In the meantime, this article provides some high-level counts of books by category.

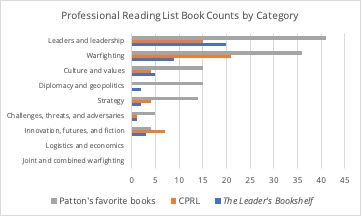

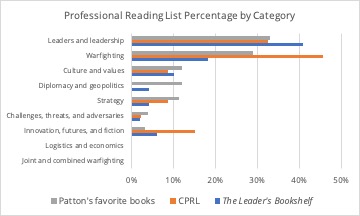

Counts and percentages of books in each professional reading list can be seen in figures 1 and 2. Patton has the most books in the “Leaders and Leadership” category, followed by The Leader’s Bookshelf and the CPRL. The books in this category have notable qualitative differences. In Patton’s case, the books about leaders were often memoirs of a commander’s or senior officer’s role in a specific war, campaign, or battle. Hamilton’s account of the Gallipoli campaign in World War I is one example of this. The campaign at Gallipoli was one of the largest amphibious operations in history and was a failure in joint command and cooperation. Thirteen of Patton’s favorite books were memoirs of combat commanders or heads of state, and 24 were authoritative biographies. Fewer books appearing in both The Leader’s Bookshelf and on the CPRL are this type of combat memoir. Patton’s book counts led in all other categories except “Innovation, Futures, Fiction.” It should be remembered, however, that Patton was the United States’ major innovator in armored and maneuver warfare.

Figure 1. Book counts by category by professional reading list

Source: courtesy of the authors, adapted by MCUP.

Figure 2. Percentage of each professional reading list’s total book count by category

Source: courtesy of the authors, adapted by MCUP.

Discussion

Comparing attributes of Patton’s favorite books that might have accounted for his success in World War II to the CPRL raised several concerns. The most prominent are the CPRL’s shortcomings in books that address challenges, threats, and adversaries; that address Joint and combined warfighting and are written by allies; that were written by or are about people whose success elevated them to general/flag officer rank and/or head of state; that are by or about commanders of divisions, corps, and field armies who fought at the theater level of war; and that discuss strategy, culture and values, and diplomacy and geopolitics.

Challenges, Threats, and Adversaries

Despite the PRC being a pacing nation of the United States, only five books on the PRC were listed on the CPRL. Russia had three, Iran four, and North Korea possibly one. Indeed, most threats and challenges mentioned in the Annual Threat Assessment and in table 1 of this article are minimally addressed by the CPRL. There is also a paucity of books written by PRC or pre-PRC Chinese national leaders and warfighters that can help readers understand and predict the PRC’s intentions, strategies, military doctrine, and methods. Books by Brian Luke, Chi Liu, Brent D. Sadler, Andrew Cainey and Christiane Prange, Lian Chao Han and Bradley A. Thayer, Kai-Fu Lee, and others can guide the U.S. future force in this regard.[55] Certainly, Patton would have recommended reading source material written by PRC and pre-PRC general/flag officers who fought in World War II, in the Chinese Civil War, and in Korea and Vietnam.

The CPRL only partly addresses other threats. These include Iran’s current methods, particularly its use of proxies, and the lessons being learned from the Russo-Ukrainian War. Iran has been covered by Brandon J. Weichert, Gabriel Tabarani, Eval Zamir, and Walid Phares.[56] Works about the Russo-Ukrainian War include those by Medea Benjamin and Nicholas J. S. Davies, Samuel Ramani, and Maarten Rothman, Lonneke Peperkamp and Sebastiaan Rietjens.[57] Tabarani and Weichert in particular almost predicted the Israel-Hamas war in Gaza that has been ongoing since October 2023.

These gaps suggest that the CPRL is not preparing U.S. military personnel to answer the question of what the U.S. military of tomorrow should look like, nor is it preparing the U.S. military to address the challenges shown in table 1 or all the threats highlighted in the Annual Threat Assessment. Additionally, to think about this with higher-order thought processes, it is not enough to cover these topics at a general, introductory level using books sold to the general public. Instead, these topics need to be written about and studied from the perspective of weaponeers and warfighters.

Additional challenges and threats beyond those in the Annual Threat Assessment and table 1 also need to be studied, including warfare at the speed of AI, warfare that creates humanitarian crises, and warfare that uses mass migration of populations or starvation as weapons. In modern history, the latter is exemplified by Chinese Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek’s breaching of the Yellow River dikes in 1938 during the Second Sino-Japanese War. Recently, the authors observed Russia’s attacks on civilian areas in Ukraine and actions threatening sites such as Chernobyl. A wide array of unrestricted means for waging war should be studied to envision a future force prepared to defend against such actions.

The areas of technology and logistics are topics of particular concern. Technology by itself does not always solve hard problems, and new technology may need to be matched to warfighting concepts. Listing key technologies that are coming online can be very beneficial to the Marine Corps and the other U.S. military Services in terms of future experimentation and assessing needed improvements in capabilities. Books on logistics offer insight into the industrial base and both challenges and opportunities for the present and the future. Logistics is the lifeline for success in the opinion of many authors. With so few books about logistics on the CPRL, it only adds questions to the planning processes for the future to support deterrence and conflict. One example is the use of 155-millimeter artillery rounds to support Ukraine in its war with Russia and the challenges in providing these items.

Joint and Combined Warfighting and Work with Allies

There is a dearth of books on history’s lessons learned about JIIM operations among coalitions of allies who themselves have competing and poorly aligned goals and objectives. Professional reading lists in general should include books about lessons learned in World War II, Korea, Beirut, Kosovo, Iraq, Afghanistan, and other conflicts. Moreover, the Marine Corps should continue providing lessons learned from recent large exercises in INDOPACOM. A few books on JIIM operations that might help envision and design a future force include those by Jeremy Black, Scott Wolford, and Mick Ryan, the latter of which offers an Australian perspective.[58]

Attaining Metacognition and Metaknowledge

Perhaps the most important thing to consider when comparing the CPRL to Patton’s favorite books is the role of professional reading lists in helping U.S. warfighters and commanders attain the level of metaknowledge attributed to Patton. Notable among Patton’s books are those that study the decision-making processes of combat commanders in the context of the total operational environment. Patton studied the thought processes, self-reflections, and self-assessments of the world’s most successful combat commanders, as well as their failures. He studied their cognitions, knowledge, metacognitions, and metaknowledge through reading their memoirs, biographies, and other writings. Where Ricks points out the haphazard and “woolly” thinking behind the selection of books in modern professional reading lists, there is nothing woolly about Patton’s favorite books or authors. Roughly 80 percent of his books’ authors had military experience, roughly 80 percent were foreigners, and roughly 60 percent were written by heads of state and/or general/flag officers.

Areas for Suggested Improvement

Areas for suggested improvement include the following:

• Decide what the professional reading lists are for and tilt the balance of books toward the development of General Patton levels of metaknowledge.

• Incorporate General Gray’s process for discussing books.

• Enhance the CPRL with inputs from the Annual Threat Assessment and National Security Strategy.

• Include more books on JIIM operations and combined warfighting.

• Add books from other U.S. military Services’ professional reading lists.

• Expand the number of books about key emerging technologies.

• Add books about multilateral logistics plans, coordination, and simulations.

• Augment the list with books on diplomacy, geopolitics, and geography.

• Add books on mobilizing the U.S. industrial base to support military operations.

• Include the direct and actual writings of potential adversaries and historical accounts of how they fought.

• Include memoirs of theater-level combat commanders to learn from their viewpoints, decisions, successes, and failures.

Most critically, there is an opportunity to use professional reading lists to foster development of systems thinking, metacognition, and metaknowledge. The authors of this article believe that incorporating this knowledge, coupled with continued rigorous mentorship and professional discussions, will accelerate the development of all military personnel and will better prepare them to design and use an integrated future JIIM/MDO force beyond the 2030 timeframe.

Limitations and Next Steps

As with any exploratory case study in which rigorous previous research is lacking, there will be limitations. The coding of books is laborious, involving classifying and quantifying by hand a multitude of topics from more than 1,000 books. Methods need to be expanded to use natural language processing, graph theory, and unsupervised machine learning to discover the emerging patterns among and across professional reading lists. Additional rigor in terms of taxonomy development, interrater reliability of classifications, and use of network analysis to analyze and classify complex books will be required to move from the typical articles complaining about professional reading lists to case studies to correlational and quasi-experimental analysis.

The current professional reading lists’ reliance on the “popular press” and publishers whose profits come from selling books that are consumable by the general public may not be adequate for educating a professional military. Likewise, while journal articles do not contain the depth of knowledge that can be contained in books, sometimes deep subject coverage by books gets published too late to be of use. Neither books nor journals typically take advantage of the internet and the use of hypertext to create a complex, rapidly navigated network, or “web of knowledge” as envisioned by Vannavar Bush.[59] More complex methods of studying professional reading lists, their impact, whether they are working, and how to disseminate knowledge will likely be required. The use of modern natural language processing methods was not possible in this work to create representations of Patton’s semantic network and mental maps and comparing those to the modern professional reading lists.

It is important to keep in mind the broader purpose and context of this article, which is to point out major gaps in the reading and methods of a proven combat commander compared to the U.S. military’s current book lists and underdefined priorities.

Coding

Readers and those who might tackle professional reading lists as done here need to be aware of some of the tradeoffs and judgments made in coding the data and the creation of the categorization scheme used in this article. These included the following:

• Patton’s “favorites book” may not be those that he would have recommended to soldiers. Consequently, Patton’s favorite books versus the CPRL does not offer an apples-to-apples comparison.

• Patton’s total library has more books in common with The Leader’s Bookshelf and other U.S. military professional reading lists. For example, Patton read Lionel Giles’s authoritative translation of Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, Rommel’s Attacks, and two translations of Clausewitz’s On War. These and many other books did not make his “favorite books” list and were not coded or used for comparisons. That, however, does not mean that he did not read books listed on the modern military professional reading lists.

• Many books, especially the older books that Patton read, are more holistic and more complex, and probably written at a higher reading level, than newer books. Consequently, there are qualitative differences between many of the books that cannot be captured and explained within the scope of this article. More complex coding schemes and data reduction methods such as factor analysis or cluster analysis will need to be applied to the professional reading lists, and perhaps entire personal libraries, if the full body of knowledge of top combat commanders such as Patton are to be analyzed.

• Fiction books presented a dilemma. This study included in its analysis books that envisioned war in the future, such as Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game and Isaac Asimov’s Foundation trilogy, but it removed historical fiction about the past, such as Anton Myrer’s Once an Eagle.[60]

• Some books included in Patton’s favorite books were those inferred by Mrs. Patton saying “anything” by a particular author, such as Churchill, Liddell Hart, or J. F. C. Fuller. All books written by such authors up to the time of Patton’s death were used in this study. Mrs. Patton also referred to Mahan’s “big three.” Not knowing which of Mahan’s books these were, it was decided to include all of his books.

• Author and book attributes came from four primary sources: Internet Archive, Google Books, Amazon Books, and Wikipedia. For example, if entries about an author in one of these sources did not include military service, that author was not coded as having had prior military service. Consequently, some entries may be in error. Full background investigations or biographies were not undertaken.

• Only the first author was coded for books with multiple authors.

• The authors of this article certainly did not read every book identified. Nonetheless, many of these listed works were read completely and almost all books were read in part, in addition to a number not on the lists. Every effort was made to eliminate errors or omissions in coding the books and their authors.

Conclusion

This article began by asking two questions: Is the U.S. military prepared to envision the future force? What must the U.S. military of tomorrow look like?

Using the Marine Corps’ current CPRL as a basis for answering these questions, and comparing the books on that list to those in the library of a combat commander who envisioned, created, and won campaigns with a future force, these authors have to say “maybe not.” The authors certainly understand that the CPRL is a tiny fraction of the knowledge available to Marines, and indeed it may not be a reliable or valid measure of what the Marine Corps knows, but it is a measure. Professional reading lists are intended to complement “schoolhouse” doctrine and professional military education, yet this study has identified multiple gaps in the CPRL when compared against a benchmark such as Patton’s favorite books list. This study has also provided recommendations for improving the CPRL so that it is not vulnerable to Ricks’s accusations of “woolly” thinking. This study suggests that the process by which a professional reading list is implemented is just as important as the content of the books on the list. These authors believe that the U.S. military can design an effective future Joint force if it strives for continual improvement with updated, thought-provoking professional reading lists and challenges all servicemembers to know their Service, the other Services, their nation’s allies, and its enemies on a larger scale.

If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles.

If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat.

If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle.

~ Sun Tzu[61]

About the Authors

Dr. Patrick O’Brien holds master’s and doctorate degrees in psychology and has more than 30 years’ experience as a human systems integration engineer and across multiple fields of psychology. He has performed threat, mission, and requirements analysis and has worked as a systems engineer, an application architect, and a consultant for the design of multiple commercial and G1–G7 information technology systems for the U.S. Army, the U.S. Marine Corps, the U.S. Air Force, the Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency, and the Office of the U.S. Secretary of Defense. He has been a principal investigator in more than 100 proprietary studies and analyses for commercial and U.S. Department of Defense clients. Prior to beginning his career in psychology, he served as a Marine Corps infantry officer for six years, holding positions from platoon commander to company commander. He served as a mountain warfare instructor and was trained in jungle and counterinsurgency operations by the Army’s 7th Special Operations Group. He taught combined arms, mortar gunnery, and leadership at The Basic School. He studied Chinese language, culture, and history for three years while attending university. https://orcid.org/0009-0001-5053-9122.

Dr. Patrick O’Brien holds master’s and doctorate degrees in psychology and has more than 30 years’ experience as a human systems integration engineer and across multiple fields of psychology. He has performed threat, mission, and requirements analysis and has worked as a systems engineer, an application architect, and a consultant for the design of multiple commercial and G1–G7 information technology systems for the U.S. Army, the U.S. Marine Corps, the U.S. Air Force, the Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency, and the Office of the U.S. Secretary of Defense. He has been a principal investigator in more than 100 proprietary studies and analyses for commercial and U.S. Department of Defense clients. Prior to beginning his career in psychology, he served as a Marine Corps infantry officer for six years, holding positions from platoon commander to company commander. He served as a mountain warfare instructor and was trained in jungle and counterinsurgency operations by the Army’s 7th Special Operations Group. He taught combined arms, mortar gunnery, and leadership at The Basic School. He studied Chinese language, culture, and history for three years while attending university. https://orcid.org/0009-0001-5053-9122.