Commander David A. Daigle, CHC, USN; Lieutenant Colonel Daniel V. Goff, USMC (Ret); and Harold G. Koenig, MD, MHSc

31 March 2023

https://doi.org/10.36304/ExpwMCUP.2023.03

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: This article serves as a response to the issues addressed in the U.S. Marine Corps’ Marine Administrative Message (MARADMIN) 677/21, FY-22 Professional Development Training Course for Chaplains and Religious Program Specialists (2021); All Marine Corps Activities (ALMAR) 033/16, Spiritual Fitness (2016); and ALMAR 027/20, Resiliency and Spiritual Fitness (2020), all of which focus on an understanding of spiritual fitness. The central theme is that Stoic philosophy and spirituality, to specifically acknowledge and include religion, are synergistic and complementary strengthening factors additive to building character, instilling core values, and optimizing warfighter readiness. This article leverages extensive clinical evidence and argues that Stoicism and spiritual fitness must be emphasized more intentionally, robustly, and systematically by leaders at all levels in the U.S. Department of the Navy to optimize warfighter readiness and attain a military advantage over the United States’ adversaries in the twenty-first century and beyond.

Keywords: spiritual fitness, religion, philosophy, Stoicism, resilience, character, readiness, warfighter readiness, holistic health

Introduction

To ensure the continued health of our collective character and identity and maintain our reputation as elite warriors, I am reaffirming the importance of spiritual fitness.

~ General David H. Berger, Commandant of the Marine Corps1

In recent years, spiritual fitness, as a vital resiliency factor that builds character, instills core values, and optimizes readiness, has gained increasing currency from leaders at the highest levels of the U.S. Marine Corps.2 For example, the current Commandant of the Marine Corps, General David H. Berger, believes that spirituality makes a positive contribution to character and resiliency, both of which are in turn critical to readiness. General Berger asserts in All Marine Corps Activities (ALMAR) 027/20, Resiliency and Spiritual Fitness, that “[w]hile the importance of physical, mental, and social fitness are more recognizable, spiritual fitness is just as critical, and [it] specifically addresses my priority to build character and instill core values in every Marine and Sailor. Character strengthens our collective warfighting spirit.”3 Importantly, Berger’s emphasis on the connection between spirituality and warfighter effectiveness closely aligns with that of his predecessor, General Robert B. Neller, who in ALMAR 033/16, Spiritual Fitness, asserts that spiritual fitness is critical to the Marine Corps.4 As such, General Neller stresses that “[r]esearch indicates that spiritual fitness plays a key role in resiliency [and] in our ability to grow, develop, recover, heal, and adapt. Regardless of individual philosophy or beliefs, spiritual well-being makes us better warriors and people of character capable of making good choices on and off duty.”5

Likewise, the chief of chaplains of the U.S. Navy, Rear Admiral Gregory N. Todd, supports the Commandants’ collective viewpoint that spiritual fitness bears directly on character. In a 2021 U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings article, Todd writes that: Since the plain of Thermopylae, character is the critical starting point in developing soldierly readiness and will be increasingly important in current competition and future conflicts. Character is, and will be, such a critical element of combat success that all leaders must deliberately approach character development as integral to combat readiness. This is the heart of the spiritual fitness effort in the Marine Corps—preparing the warrior for today’s competition and any future conflict.6

Undoubtedly, the collective message of both Commandants, as well as Chaplain Todd and other military leaders, on the importance of spiritual fitness in building toughness and resiliency is expansive in its potential to support all the priorities within the Commandant’s Planning Guidance—that is, to build character and instill core values.7 However, spiritual fitness has remained largely within the undercurrents of knowledge and concern among senior officers. The result has been a dearth of any meaningful discussion, let alone purposeful installation in any material way, at the individual or unit level in the Navy and Marine Corps.8 This stands in contrast with the mental, social, and physical components of overall fitness, all of which are widely understood, robustly framed, and integrated within the command. This lack of attention to spiritual fitness may be the result of commanders concerned with being seen as promoting their own religion (proselytizing) or simply having a generalized fear of running afoul with the Judge Advocate General’s Corps or staff judge advocates regarding the establishment clause.9 It can also be the result of competing priorities as well as dealing with nuanced subject matter.10 Regardless, it seems that most commanders do not directly address, cultivate, or implement spiritual fitness very robustly in their commands.11 While many commanders are not familiar with ALMARS 033/16 and 027/20 or the Commandants’ views on the subject, and while they may not directly address, fully understand, or employ spiritual fitness in their commands, the inherent value and importance of spirituality is often evident in their personal lives and considered essential to their own resiliency as well as to that of their Marines.12

As such, this article responds to the issues addressed in the U.S. Marine Corps’ Marine Administrative Message (MARADMIN) 677/21, FY-22 Professional Development Training Course for Chaplains and Religious Program Specialists, regarding the understanding of spiritual fitness within the framework that commanders face. The article proposes leveraging both Stoic philosophy and spirituality, to specifically acknowledge and include religion, as synergistic and complementary factors additive to building character, instilling core values, and optimizing warfighter readiness.13 The article argues that, taken together, Stoicism and spiritual fitness must be emphasized more intentionally, robustly, and systematically by leaders at all levels in the U.S. Department of the Navy (DON) to optimize warfighter readiness and attain a military advantage over the United States’ adversaries in the twenty-first century and beyond.14

Accordingly, part one of the article broadly discusses the value of Stoicism and the ways in which it can have a direct positive impact on the toughness and character of today’s sailors and Marines. By extension, its clear impact on mission readiness is also demonstrated. To the degree that Stoicism is a belief system focused on virtue and the highest good, it is not antithetical to the principles of spiritual fitness or spirituality. The ancient Stoic’s worldview had a sense of the divine as immersed in nature. In other words, the practitioners of Stoic philosophy did not believe in God as a transcendent and omniscient being standing outside nature, but rather that by living virtuously those who were wise could live in harmony with the divine reason (logos) that permeated all of nature. As such, ancient Stoicism does not stand in variance with religion or spiritual fitness. Aside from this, part one will examine the many valuable benefits of Stoicism, providing valuable insights for today’s military on Stoicism’s favorable effect on character, mental toughness, and warfighter readiness. Part one concludes with a recommendation for leaders at all levels to become students of Stoicism, as doing so will yield much with regard to personal growth in military virtues that can then filter down throughout the command. Ideally, Stoicism will permeate a commander’s leadership style and allow them to share meaningful lessons learned from its practice, thereby improving overall command readiness.

Having established the value of Stoic philosophy and its role in strengthening the human spirit, part two springboards to a broader discussion on the role of religion/spirituality as an underutilized but invaluable strengthening factor that has the potential for meaningful impact on positive command outcomes, including warfighter readiness, while at the same time reducing destructive behaviors. Much of this discussion involves clinical analysis and presents data-driven research regarding the impact of religion/spirituality on happiness and life satisfaction, meaning and purpose, character and virtue, close social relationships, and mental and physical health. This section also provides the same clinical analysis and research on the impact of religion/spirituality on lowering substance use problems, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), conflict about moral injury, and suicide risk. Part two provides clinical research strongly suggesting that religion/spirituality is a great strengthening agent that fortifies and enhances such things as character development, warrior toughness, and resiliency. In so doing, part two forges and significantly advances the positive benefits that are statistically accretive for any commander, such as strengthening the resiliency of sailors and Marines at all levels across the entire DON. The article concludes that Stoicism and religious/spiritual practice go hand-in-hand to further the goals of leveraging holistic health as a twenty-first-century military strategy while building character, instilling core values, and optimizing warfighter readiness.

Part One: The Modern “Stoic Warfighter”: Stoicism’s Influence on Military Character, Core Values, and Readiness in the Twenty-First Century

Stoicism’s Connection to the Military: The Examples of General James N. Mattis and Vice Admiral James B. Stockdale

Stoicism has experienced a renaissance of sorts in recent years, and it is increasingly seen by many today as a valuable means toward managing emotions, increasing resiliency, and facing challenging situations in life.15 This assertion has been marked by a rise in Stoic self-help books, digests of Stoic quotes, websites with Stoic wisdom to kickstart one’s day, podcasts, broadcasts, and numerous online crash courses that teach such things as how to become more “manly,” how to become calmer, how to meditate Roman style, how to practice abstention, how to take more control of one’s life, and how to take less. As a philosophical practice noted for reducing stress and cultivating goodness, Stoicism has become recognized as “the new Zen.”16

While Stoicism gains wider cultural appeal to a broader society today, its perennial value has long been recognized and valued within the military community, esteemed not only as a means to endure hardships but also as a proven path toward instilling core values and acquiring a virtuous military character.17 It therefore seems evident that members of the military intuitively understand and appreciate Stoicism’s contributions to virtuous soldierly character, which, in turn, increases mental toughness and resiliency both at the individual and unit levels.18 Resiliency is understood to be not simply “a matter of hardening networks and enhancing weapon systems to defend against kinetic or cyberattacks.”19 Rather, resiliency is understood by Stoicism as something that animates warfighters such that individuals and units are able to withstand extraordinary difficulties and then rebound from the effects of great hardships that assault the human spirit and degrade the will to win.20 In short, this understanding of the inherent value of Stoicism to warfighters has deep roots that reach back across millennia to the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius and other Stoic warriors, including Stoic philosophers of ancient Greece and Rome.21

It is these connections between Stoicism and the military that endure even to this day. This concordance provides continuity from the great Stoic figures of antiquity, such as Marcus Aurelius, to the esteemed philosophical-warfighters of the modern era, such as U.S. Marine Corps general James N. Mattis and U.S. Navy vice admiral James B. Stockdale. Famed for their rectitude, both Mattis and Stockdale exemplify Stoicism’s enduring impact within the U.S. military. In addition, both men are revered luminaries in the DON, which has continually drawn from their vast stores of wisdom and knowledge as a critical component to effective leadership. To this end, numerous stories and memorable vignettes exist today that show the profound impact that these men have had on senior leaders. Mattis, for example, was famously known as the “Warrior Monk” for having a collection of more than 7,000 volumes in his personal library.22 His reputation in this regard was furthered by the fact that he was known to always carry a tattered copy of Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations into combat.23 Drawing from the Stoic wisdom that fills its pages, Mattis found Meditations “to be incredibly valuable for handling the stress and anxiety of being in combat.”24 For Mattis, however, the true value of Stoicism extended beyond the extraordinary conditions faced in combat. Rather, Stoicism’s value reached into the day-to-day lives of people, providing guidance and a blueprint for life when faced with daily challenges and difficulties in any given situation. To this end, Mattis has said that Meditations is the one book every American should read.25 Preeminent for Mattis is the importance of having good principles and adhering to them—that is to say, where his “flat-ass rules” rules apply. This concept of “flat-ass rules” is explained in Mattis’ New York Times bestselling book, Call Sign Chaos: Learning to Lead.26 In the book’s opening chapter, Mattis discusses the fundamental lessons from early in his Marine Corps career, arguing that conviction is harder and deeper than physical courage: “Your peers are the first to know what you will stand for and, more important, what you won’t stand for. Your troops catch on fast. State your flat-ass rules and stick to them. They shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone.”27

In a similar way, Stoicism was preeminent in the life of Vice Admiral Stockdale, who was a prisoner of war (POW) for more than seven years during the Vietnam War. Much like Mattis, Stockdale’s reputation was that of a “Stoic warrior” who drew wisdom from the Stoic greats. Indeed, so profound was the influence of Stoicism on his life that in an interview by author Nancy Sherman for her book, Stoic Warriors, she found Stockdale’s “words and attitude [to be] almost indistinguishable from those of the Roman Stoic Epictetus, whose Enchiridion he had nearly committed to memory before his plane was shot down over Vietnam in 1965.”28 Stockdale drew on Stoicism to overcome frequent torture and years spent in isolation. Just as for Mattis, Stoicism was for Stockdale instrumental in dealing with all manners of adversity, and its importance and value went beyond bearing suffering and the travails of combat.29 Stockdale’s embrace of Stoicism saved lives, ultimately resulting in “a hero’s welcome for helping the 591 men under his command to return home safely.”30 As a result, Stockdale is celebrated for his incredible resolve and fortitude as a patriot and philosopher-warrior who endured incredible challenges as a POW.31 Indeed, his name has become synonymous with leadership and ethics, with his life story forming the center of ethical thought and leadership at both the U.S. Naval Academy and the U.S. Naval War College.32

In a final analysis, the lived examples of General Mattis and Vice Admiral Stockdale are of profound value to the U.S. military Services as people of character who personify core values and epitomize military fitness and readiness. For this, they are rightly venerated as two of the naval Services’ all-time great leaders. This is in no small measure directly attributable to Stoicism, the “noble philosophy” that, in Stockdale’s words, “has proven to be more practicable than a modern cynic would expect.”33

The Value of Stoicism: Ancient Roots to Wisdom and Its Relevance to the Naval Services Today

The examination of Stoicism in this section references the ancient Stoics from the early third century BCE, beginning with the Hellenistic philosopher Zeno of Citium (334–262 BCE), to Marcus Aurelius (121–180 CE), the last major Stoic.34 This distinction is important, as the neo-Stoics of the Renaissance period advocated a detached and emotionless approach to life, whereas the ancient Stoics recognized emotion and passion but endeavored to not be ruled by them and instead rely on reason to overcome and thrive under adversity. The ancient Stoic appreciation for emotion can be found in the opening of Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations. Here, the Roman emperor thanks his tutor Sextus Empiricus for being “free of passion yet full of love,” which from the Stoic perspective acknowledges positive emotions such as love while also being in control of one’s passions.35 For the ancient Stoics, the cultivation of reason over emotion was analogous to the creation of the “Inner Citadel,” according to French philosopher Pierre Hadot.36 This personal cultivation of resiliency based on physical and mental control is what the Greek Stoic philosopher Epictetus (50–135 CE) meant by his statement, “what disturbs men’s minds is not events but their judgments on events.”37 The other foundational tenets of ancient Stoicism were service to the common good, the acceptance of one’s fate, and that true happiness was realized through the development of one’s character through the cultivation of personal virtue. These pillars of Stoicism will serve as the foundation for further analysis and application toward military holistic health in the following paragraphs.

In discussing the benefits of Stoicism to the military in terms of building character and increasing readiness, it is important to frame at the outset the problem of resiliency within the military as it pertains to leadership addressing the topic of spirituality and the spiritual. In doing so, it must be recognized at the forefront that it is standard practice within military units to see individual toughness largely as a nonissue until someone is injured or broken in some capacity. It must also be acknowledged that a real dilemma for many military commanders today is that they face the challenges of an increasingly irreligious society and that many of their sailors and Marines may not see themselves as religious. Moreover, many leaders are uncomfortable with discussing spirituality because of a sense of conflating that discussion with religious beliefs or traditions. Consequently, if a Navy chaplain is to continue to be one of the primary sources of care for sailors and Marines, the gap must be bridged to spiritual fitness. With that in mind, the contemporary definition for spiritual readiness can be understood as the strength of spirit that allows the warfighter to accomplish the mission with honor.

Generally, military leadership can support chaplains and the larger force in spiritual readiness by understanding the total concept of the person (as in alignment with the Marine Corps’ Human Performance Branch) and by proactively integrating spiritual toughness, character development, and core value development into the day-to-day battle rhythm that occurs in the inner lives of battalions and squadrons.38 However, the unfortunate reality is that spiritual fitness, as it pertains to a legitimate and acknowledged readiness component, at the unit level is not understood or recognized by leaders in any real or meaningful way. Consequently, individual toughness pertaining to the force is unaddressed until it is obviously broken, and it is then that leaders participate in a retroactive review of the sailor or Marine and engage with strengthening factors as well as deleterious stressors that explain the failure of the sailor or Marine. It is only at this stage of destruction or disability that sailors and Marines are being sent to see a chaplain or another identified care provider to report on what they are doing to mitigate the situation. To the authors’ minds, this approach is entirely avoidable and backward. Leaders should be proactive across all levels of human performance. Fortunately, Commandants of the Marine Corps are trying to reverse this notion. Spiritual resiliency must be addressed proactively. There is an immediate need to bridge the gap between the praxis of operational units and their demanding schedules and balance it with an aggressive focus on proven enhancers of resiliency. This must include the Commandants’ focus on spiritual fitness as a critical strengthening factor.

While Stoicism is commonly thought of as a philosophical construct, the ancient Stoics were connected with the gods.39 In fact, Stoicism has a deep alignment with spirituality, and the ancient practitioners viewed their philosophy in accordance with the divine. Epictetus, a former slave who became a Stoic philosopher under the tutelage of the Roman philosopher Gaius Musonius Rufus, framed his philosophy in accordance with the divine. As well, Marcus Aurelius noted that the gods are what tie humankind together.40 As the Roman Empire adopted Christianity under the rule of Constantine the Great (272–337 CE), the ancient Stoics also influenced early Christianity in a variety of ways. For example, Saint Paul (5–65 CE) was born in Tarsus, a historic city located in present-day southern Turkey, where Stoic philosophy was prevalent and the apostle’s ideas concerning theology and ethics may have had a Stoic foundation.41 A modern influence of Stoicism on Christianity can also be found in the Serenity Prayer written in the early 1930s by the American theologian Helmut Richard Niebuhr: “God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and wisdom to know the difference.”42 While Niebuhr may not have been a Stoic philosopher, his call for God to assist in knowing what is controllable and what is not is clearly a Stoic notion of personal resiliency and agency. While at first glance Stoic philosophy, spirituality, and religion may not seem related to the concepts of holistic health and military readiness, the building blocks of resiliency, ethical behavior, and character are evident in all three.

Stoicism places a heavy emphasis on physical and mental discipline. This self-control is captured by British mathematician Bertrand Russell’s remark concerning the ancient Stoics’ appreciation for Socrates, as he was famously indifferent to bodily discomforts and resolute in the acceptance of his death.43 The Stoics believed that the body was an external aspect of the self and as such could neither provide virtue nor deliver fulfillment. Epictetus, during his enslavement, was tortured and his leg forever rendered lame after a particularly harsh beating by his master. However, Epictetus believed that his lameness was relegated solely to his body, while his mind and will were all that he required.44 At face value, it may seem that the Stoics held little regard for the concerns of the body. Considering that disease, genetic disorders, and accidents are beyond one’s immediate control, the Stoics deemed that these things should be disregarded and considered external and unimportant. However, the body cannot be discounted by the Stoics from a military perspective because the body can be used to perform good deeds. In that sense, the body is indispensable to military service. Servicemembers face a number of demanding physical requirements, such as initial physical screenings, physical fitness tests, physical minimum standards for military occupational specialties (Marine Corps) and ratings (Navy), demanding duties in the elements that take a toll on the body, deployments to different climates, and coping with injuries, all of which are part of a servicemember’s existence. For a select and indispensable few, the rigors of combat will test servicemembers physically, mentally, and psychologically. Servicemembers must remain disciplined to ensure that their bodies are fit enough to handle the rigors of military service.

The physical component of military service is becoming more tenuous as the United States copes with an obesity epidemic.45 Former U.S. secretary of defense Ashton B. Carter noted in 2015 that only one-third of 17 to 21-year-old American youth were physically eligible to join the military.46 A study conducted from 2010 to 2014 concluded that 27 percent of Americans aged 17–24 years were too overweight for military service and that 47 percent of males and 59 percent of females failed the U.S. Army’s entry-level physical fitness test after entering basic training.47 More recently, the current recruiting crisis revealed that three-quarters of American youth were not physically and mentally qualified for military service, with 11 percent disqualified for being overweight, 8 percent for drug abuse, and 7 percent for physical health reasons.48 As the military struggles to find American youth who are physically able to meet the demands of military service, it becomes imperative that it maintains a culture of fitness and retains as many servicemembers as possible. To achieve this goal, Stoic philosophy can aid in connecting physical fitness to not only passing annual physical fitness tests but also to fulfilling one’s character and the unit’s missions. While the future of warfare may become more technological, the physical component will not be eliminated and could even increase the demand for physically fit servicemembers, especially as the Navy and Marine Corps contemplate force design changes that place servicemembers inside a contested battle space for significant periods of time.

Military life is inherently stressful. It is mentally demanding, and a constant component of it is uncertainty. Deploying in support of a wartime operation, coping with the deaths of fellow sailors and Marines, responding to an international or domestic humanitarian crisis, facing changes in deployment timelines, responding to a training accident, being sent away to faraway schools or training opportunities, performing new billet requirements, being thrust into new leadership roles, and performing duties that have dire consequences are the norm for many servicemembers. In many respects, the individual servicemember has no control of where they find themselves in these situations. Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz’s “fog of war” accurately describes the uncertainty of combat, but the entire scope of military service can also be largely characterized by uncertainty, as well as a lack of personal control or the ability to shape external events.49 To the ancient Stoics, uncertainty is not to be feared but rather embraced. This notion is best captured by Epictetus: “Do not seek for things to happen the way you want them to; rather, wish that what happens the way it happens: then you will be happy.”50 This should not be taken as a call to passivity or resignation from one’s external circumstances—it is quite the opposite, according to the ancient Stoics. By rationally addressing the external issues at hand and regulating one’s emotions and actions to achieve the desired end state—this is what the ancient Stoics aspired to attain at the personal level. While servicemembers cannot control the situations in which they find themselves, they can conduct themselves honorably to accomplish the mission in the best interest of those they lead. This type of outlook can also increase resiliency through positive adaptation, which can be defined as “the ability to maintain or regain mental health, despite experiencing adversity.”51 The concept of amor fati, or “love of one’s fate,” is the philosophical lens through which the ancient Stoics used to cope with their uncertain world.52

The Modern “Stoic Warrior”: An Affirmation of Character, Core Values, and Readiness in the Twenty-First Century

The world has continued to be as dangerous and uncertain today as it was for the ancient Stoics. A modern example of amor fati can be seen in Vice Admiral Stockdale’s internment as a POW during the Vietnam War. As the commander of Carrier Air Wing 16 aboard the aircraft carrier USS Oriskany (CVA 34), Stockdale flew some of the first U.S. bombing missions against North Vietnam. On 9 September 1965, his Douglas A-4 Skyhawk attack aircraft was shot down.53 Floating helplessly down to earth and into captivity, he had the keen self-awareness to note, “I’m leaving the world of technology and entering the world of Epictetus.”54 Stockdale was the senior ranking U.S. Navy officer held at the infamous Hoa Lò Prison in Hanoi, North Vietnam, known among American POWs as the “Hanoi Hilton.” He was kept prisoner for seven and a half years, during which he spent four years in solitary confinement and two years in leg irons and was tortured at least 15 times. Throughout the entire ordeal, Stockdale led his fellow POWs with courage and compassion. His unbreakable spirit and leadership continued until his release in February 1973, and for the leadership of his fellow POWs, he was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1976.55

When asked by author Jim Collins about which POWs did not survive, Stockdale replied, “Oh, that’s easy, the optimists. Oh, they were the ones who said, ‘We’re going to be out by Christmas.’ And Christmas would come, and Christmas would go. Then they’d say, ‘We’re going to be out by Easter.’ And Easter would come, and Easter would go. And then Thanksgiving, and then it would be Christmas again. And they died of a broken heart.” Stockdale elaborated on an important aspect of Stoicism as it relates to one’s external circumstances and how to cultivate will and resiliency: “This is a very important lesson. You must never confuse faith that you will prevail in the end—which you can never afford to lose—with the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be.”56 To Stockdale, Stoic philosophy was tested in “a laboratory of human behavior,” and during a time of considerable stress, pain, and solitude, it helped him find the resiliency to return with honor.57

The purpose of self-control and indifference to external factors in favor of reliance on one’s ability to temper emotions is ultimately to cultivate character and virtue. To the ancient Stoics, material possessions, reputation, fame, and wealth were neither good nor bad—they were simply aspects of life that should be treated indifferently. The true purpose of life was to live a life of character and virtue. Virtue was the path to the divine, a focus whose roots are found in the ancient Greek philosopher Plato’s Republic and Aristotelian virtue ethics. To Aristotle, another ancient Greek philosopher, the four cardinal virtues were wisdom, justice, temperance, and courage, which served as the basis of his ethical system.58 Highlighting virtues offered a way for the Stoics to minimize negative emotions and instead focus on what could be controlled. More precisely, they asked the following question: What are the constructive measures that can be taken to overcome adversity and not simply fall prey to emotions, worry, and anxiety about aspects of our lives that are beyond our control or are simply a negative possibility in a sea of possibilities?

It is important to note that the cultivation of virtue is a daily and conscious decision. Aristotle and the Stoics believed that virtue was a matter of habit and rational choice. The purpose of virtue was virtue itself, as well as the service of the greater good. Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations offers a wonderful example of what the Stoics were determined to achieve with their commitment to character and virtue. It must be understood that Meditations was never intended to be published—what the world knows as Meditations today is actually a collection of working philosophical notes by a Roman emperor in which a common theme is a consistent call for patience, kindness, and a way to educate his fellow Romans. Marcus Aurelius was the most powerful person not only in Rome but also possibly in the world. Nevertheless, as a Stoic, his purpose was to live a life of character and virtue in the service of Rome, and he wrote the notes that became Meditations as reminders to improve his character and empire.

The importance of character is readily evident in the U.S. naval Services. Honor, courage, and commitment are the values that form the bedrock of character in the Navy and Marine Corps. From a leadership perspective, the ancient Stoics have a great deal of wisdom to offer military leaders. The ability to control one’s emotions, especially in times of fear and stress, can greatly add to a feeling of confidence and trust for sailors and Marines placed at the tip of the spear. The leader’s focus on character in service for the greater good can also orient those in the command away from mindless distractors, administrative matters as the priority, and behaviors that are not in line with cultivating character. Stoicism also prioritizes learning, which, in a rapidly changing world and with both the Navy and Marine Corps struggling through the force design process, places leadership that is willing to adapt and learn at a premium.59 In the Discourses of Epictetus, Epictetus states that “[i]t is impossible for a man to learn what he thinks he already knows.”60 This serves as a general Stoic outlook toward knowledge, learning, and adapting. For any military unit to adapt, experiment, and modernize training, it requires a leader who is intellectually humble and willing to innovate rather than rely on how they managed wars in the past. Leaders who adopt this outlook will also be more apt to create learning teams within their commands that will be better prepared to self-assess weaknesses and develop strategies for success.61

While ancient Stoicism has been the focal point of analysis to this point, it is worth noting that it should not be at the exclusion of other philosophical, spiritual, or religious traditions. At times, Stoicism, especially under Epictetus, can seem like a philosophy of self-deprivation and denial of one’s emotions.62 However, the support and resiliency that the Stoics offer military members as they cultivate virtue to establish a measure of emotional control in the face of turmoil, stress, and loss is worth understanding and incorporating. The Stoic belief in amor fati—love of one’s fate that external factors are often outside one’s immediate control—translates well into a military application in which sailors and Marines are encouraged to control their emotions and thoughts. This distinctly Stoic perspective can help build mental toughness and resiliency. The final pillar of the Stoic philosophy is the formation of character and virtue in the service of something greater than self, which is a powerful complement to military service. Acts that are devoid of character offer a stark reminder of the importance of virtue at the individual level and have far-reaching negative impacts at the organizational level. Breaches of character, such as the Navy’s Fat Leonard scandal and Marine snipers urinating on dead Taliban fighters in Afghanistan, bring discredit to the naval Services and diminish the trust and faith that the American people have in their Navy and Marine Corps.63

Part Two: Religion and Spirituality: Minimizing Destructive Behaviors, Achieving Holistic Health, and Optimizing Warfighter Readiness

The Strategic Advantage of “Spiritual Fitness”

In 2018, U.S. secretary of defense James N. Mattis tasked the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness with developing policies to ensure that everyone who enters the military, and those remaining in military service, are to be deployable worldwide. He remarked on the need to look at the force holistically to ensure “that everyone who signs up can be deployed to any corner of the world at any given time.”64 Subsequently, U.S. under secretary of defense for personnel and readiness Robert L. Wilkie Jr. discussed the impact that nondeployable forces were having in terms of military lethality and readiness. In compelling testimony, he stated, “On any given day, about 286,000 Service Members—13 to 14 percent of the total force—are non-deployable.” In fact, he added, “[t]he situation we face today is really unlike anything that we have faced, certainly in the post-World War II era.”65

The problem, according to a 2018 Rand report, is that the U.S. military today “treats war primarily as a contest of opposing gear.” However, war “is a fundamentally human endeavor; thus humans should be the central focus of warfare.”66 This aligns with Carl von Clausewitz’s view that military activity is not directed against material force alone. Indeed, as explained by U.S. Naval Reserve chaplain Paul R. Wrigley, military activity “is always aimed simultaneously at the moral forces that give it life, and the two cannot be separated. For Clausewitz, the term ‘moral’ referred to the ‘sphere of mind and spirit,’ intangible attributes, the principle being ‘courage.’ While Clausewitz was not concerned specifically with the spiritual, religious belief is ‘a moral force, one that should not be ignored in the theater of operations’.”67

Yet, despite this, the spiritual aspects of readiness have received relatively little attention by today’s leaders. This neglect of spiritual readiness is a serious problem. This is principally so because it hollows the force, leaving servicemembers with limited moral reasons for making the extraordinary efforts and sacrifices necessary to accomplish missions. Servicemembers will fight to avoid being killed; they will fight for their nation, or even the freedoms of other nations; they will fight for their families and way of life; and they will fight out of anger to avenge fallen comrades.68 But those motivations are often not enough. Warfighters need a higher reason for risking their lives, a reason from above that can be defined as spiritual—to right the wrong, to preserve goodness, and to fight evil that is trying to destroy goodness. As Wrigley notes: Although acknowledged by military doctrine, religion and spirituality, generally speaking, are downplayed—even to the point of disregarding—the direct influence of religion on politics or war; it stems from a prevalent feeling that religion is a private, not a public, matter. That view is not held in other parts of the world, and such myopia can lead to misunderstanding. Religion and religious beliefs are powerful forces that have existed since the dawn of man. They are not limited to any one part of the world but touch the lives of men, women, and children around the globe. For many, religion is the true source of courage and strength. It can inspire and mobilize combatants and affect the outcome on the battlefield.69

To this end, the present section asserts that spiritual fitness fundamentally increases human flourishing (i.e., meaning and purpose, character, and close social relationships) in ways that enhance total force fitness, thereby increasing warfighter readiness and enhancing the will to fight. In so doing, this section will present a growing body of military and nonmilitary studies that offer quantitative evidence. The methodology here involves a brief review and summary of research documenting the effects of spiritual involvement on virtually every aspect of health, all of which can help enable warfighters to perform at their highest level during combat operations. That said, it is imperative that operational commanders should open their aperture with regard to the importance of religion/spirituality since: An operational commander, however well trained in the military issues, who is ignorant or discounts the importance of religious beliefs can strengthen his enemy, offend his allies, alienate his own forces, and antagonize public opinion. Religious belief is a factor he must consider in evaluating the enemy’s intentions and capabilities, the state of his own forces, his relationship with allies, and his courses of action.70 In summary, commanders should think of religion/spirituality within the context of a total force fitness model.

With this understanding, the Marine Corps in recent years has moved to elevate spiritual fitness more robustly within the organization and to intentionally recognize and elevate the spiritual. In doing so, it echoes what has been recognized by military leaders for millennia. With the publication of ALMARS 033/16 and 027/20, the concept of spirituality has become an important component of an individual Marine’s overall fitness and increasing operational readiness. In conjunction with these two ALMARS, MARADMIN 226/20, Renaming of Force Fitness Division as the Human Performance Division, marked a significant shift in how the Marine Corps addresses fitness. The Marine Corps’ Force Fitness Division, which maintained oversight of all physical fitness programs, was renamed Human Performance Division and adopted a holistic approach toward the performance of every Marine.71 Additionally, the chaplain of the Marine Corps assigned the spiritual fitness officer on their staff to become the resiliency branch head for the Human Performance Division. This job was implemented to develop the resiliency aspect of physical, mental, social, and spiritual fitness. Since the release of MARADMIN 226/20, the Human Performance Division has been renamed the Human Performance Branch, which encourages Marine leaders to engage chaplains for assistance and resources to help lead Marines in total fitness and resiliency.72

The Marine Corps is not the only branch of the U.S. military seeking means to increase readiness and lethality through holistic fitness.73 In October 2022, the U.S. Army published the U.S. Army Holistic Health and Fitness (H2F) mandate with the expressed goal to “enable commanders to improve Soldier health and fitness.”74 To accomplish this task, the Army identified five key physical and nonphysical domains—mental readiness, sleep readiness, physical readiness, nutritional readiness, and spiritual readiness—to increase “optimal performance and improved readiness.”75 The impetus for H2F was that, as of April 2020, the Army had 58,400 soldiers—equivalent to 13 brigade combat teams—who were deemed nondeployable. To initiate this change, the Army created “human performance teams” at the brigade level to act as catalysts and implement actions to achieve the desired goals of H2F. These teams include specialists such as registered dieticians, physical therapists, occupational therapists, human performance experts, athletic trainers, and strength coaches, whose purpose is to achieve core H2F priorities.76 While the H2F concept addresses spirituality, its main focus is to address physical deficiencies. This contrasts with the Marine Corps’ more balanced approach toward holistic fitness as defined in ALMARS 033/16 and 027/20.

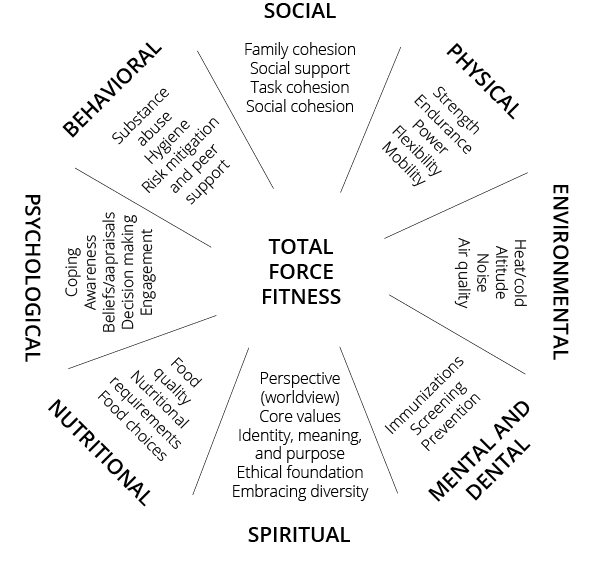

On 1 September 2011, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, U.S. Navy admiral Michael G. Mullen, published the Total Force Fitness (TFF) Framework to create a “methodology for understanding, assessing, and maintaining Service members’ well-being and sustaining their ability to carry out missions.”77 The TTF Framework recognizes eight domains (figure 1) and five tenets:

- Total fitness extends beyond the servicemember; total fitness should strengthen resilience in families, communities, and organizations.

- A servicemember’s family’s health plays a key role in sustained success and must be incorporated into any definition of total fitness.

- Total fitness metrics must measure positive and negative outcomes, and must show movement toward total fitness.

- Total fitness is linked to the fitness of the society from which the servicemembers are drawn and to which they will return.

- Leadership is essential in achieving total fitness.78

The TFF Framework addresses metrics without citing any specific studies that indicate the benefits or possible negative aspects of spiritual fitness. The 10 associated metrics are a combination of surveys, medical evaluations, tests, and questionnaires, and much like the H2F concept and ALMARS 033/16 and 027/20, there are no metrics linking spiritual readiness to positive operational outcomes.

Figure 1. Total force fitness domains

Source: Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Instruction 3405.01, Chairman’s Total Force Fitness Framework (Washington, DC: Joint Chiefs of Staff, 1 September 2011), A-2.

The Religious/Spiritual Component of Warfighter Readiness: The Evidence

To date, spiritual readiness has been a less discussed, less appreciated, and largely neglected component of warfighter readiness.79 Servicemembers “typically receive extensive training in the tactical, physical, mental, social, and behavioral aspects of readiness, while the spiritual aspects are often ignored.”80 However, there is growing evidence that active spiritual involvement is a key source of spiritual fitness, which influences human flourishing, a condition that is closely related to warfighter readiness.81 In this way, religious/spiritual beliefs and practices have the potential to increase warfighter readiness, thereby increasing the likelihood of success in missions focused on keeping the peace or winning wars.82 Many of the destructive behaviors of servicemembers that concern U.S. military leaders today are affected by religious/spiritual involvement. These destructive behaviors include inter alia suicide-related behaviors, depression, substance use disorders, driving under the influence of drugs or alcohol, domestic violence, PTSD, and sexual assault, as well as inner conflicts from transgressing moral values during combat operations. All of these behaviors can contribute to an increase in suicide risk as well as a corresponding decline in the spectrum of warfighter readiness, which includes preparing for deployment, engaging in combat operations, and reintegrating into society following deployment. In other words, a lack of spiritual readiness correlates with a proclivity toward destructive behaviors.83

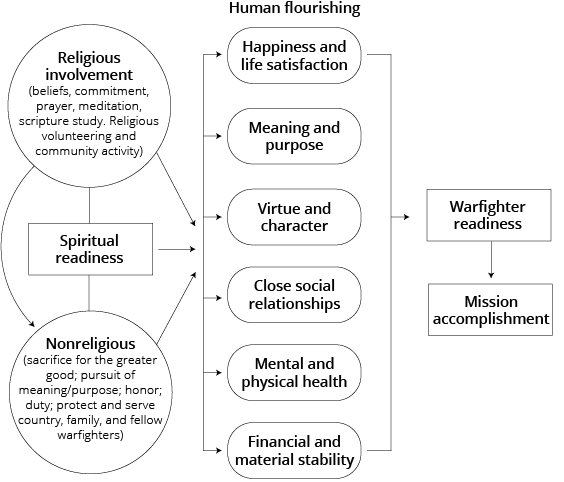

First, it is worth examining what human flourishing is and how it relates to warfighter readiness. In a seminal article published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America by Harvard University professor Tyler J. VanderWeele, human flourishing refers to “a state in which all aspects of a person’s life are good . . . of complete human well-being,” which is reflected by “doing or being well in the following five broad domains of human life: (i) happiness and life satisfaction; (ii) mental and physical; (iii) meaning and purpose; (iv) character and virtue; and (v) close social relationships.”84 A sixth domain, financial and material stability, was added later, since without such stability human flourishing might not be able to be maintained over time.85 More than a decade ago, the Chairman of the Joint Chief of Staff issued an instruction that defined warfighter readiness as being capable of conducting all required military operations, as well as maintaining fitness across multiple domains that include the physical, environmental, medical, dental, nutritional, psychological, behavioral, social, and spiritual.86 It is clear that warfighter readiness as described above includes many of the same dimensions as human flourishing. Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between religious and nonreligious sources of spiritual readiness, human flourishing, and warfighter readiness. But is there any scientific evidence that the causal pathways in this model are true? This research is briefly reviewed below.

Figure 2. Theoretical causal model

Source: Harold G. Koenig, Lindsay B. Carey, and Faten Al Zaben, Spiritual Readiness: Essentials for Military Leaders and Chaplains (Seattle, WA: Amazon Kindle Direct, 2022), 153.

Spiritual Readiness and Human Flourishing

Because spiritual beliefs and practices are a primary source of spiritual readiness, examining their effects on human flourishing may offer some conclusions about how spiritual readiness influences human flourishing. While there are also nonreligious sources of spiritual readiness, there is much less published research that examines these connections with human flourishing. The six primary dimensions of human flourishing that are focused on here are as follows: happiness and life satisfaction; meaning and purpose; character and virtue; close social relationships; mental and physical health; and financial/material stability.87

Happiness and Life Satisfaction

If spiritual involvement enhances happiness and life satisfaction, then it will likely increase warfighter readiness. A systematic review of quantitative research published in peer-reviewed academic journals from the 1800s through 2010 identified 326 studies.88 Of those, 256 (79 percent) reported that higher levels of religiosity/spirituality were related to greater psychological well-being, happiness, life satisfaction, and other positive emotions, while only 3 studies (less than 1 percent) reported significantly lower well-being among those more spiritually involved.89 These findings have been largely replicated in a more recent systematic review, including studies of current or former military personnel.90

Meaning and Purpose

Religious/spiritual involvement has been consistently related to greater meaning and purpose in life. Of 45 quantitative studies identified in the systematic review described above, 42 (93 percent) reported greater meaning and purpose among those who were more involved in spiritual activities.91 Research conducted in the past 10 years using larger samples and better study designs has replicated these findings, including studies in young adults.92

Character and Virtue

When a military mission is conducted with honor, the emotional casualties (particularly the inner conflicts over moral transgressions) are far less common. The systematic review described above identified studies examining the relationship between spiritual involvement and a wide range of character traits such as altruism, volunteering, gratitude, forgiveness, and delinquency or adult crime. Most of these studies found that greater spirituality was associated with significantly more acts of altruism, volunteering, gratitude, willingness to forgive, and lower levels of delinquency and crime; in this last case, 82 of 104 studies (79 percent) found lower rates among those scoring higher on spiritual involvement.93

Close Social Relationships

Healthy social relationships are essential for members of military units who must work together to accomplish missions and watch each other’s backs during life-threatening situations. Religious/spiritual teachings strongly encourage healthy social relationships. In the systematic review described above, spiritual involvement was associated with significantly greater social support in more than 80 percent of quantitative studies.94 More recent studies in young adults of military age have reported similar findings.95

Mental and Physical Health

It is self-evident that mental and physical health problems interfere with the warfighter’s ability to carry out their duties. Mental and physical fitness are not only domains of human flourishing but also key aspects of warfighter readiness. This subsection will first examine the effects of religious/spiritual involvement on mental health and then briefly review the effects on physical health. With regard to mental health, it focuses on studies examining the relationship between spirituality and depression, substance use disorders, PTSD, inner conflict (moral injury), and suicide risk.96

In the systematic review described above, a total of 444 quantitative studies were identified that examined the relationship between religious/spiritual involvement and depression.97 Nearly two-thirds of the studies (272, or 61 percent) found that spirituality was associated with less depression and faster recovery from depression, and that spiritual interventions were effective in reducing depression.98 More recent research involving 9,862 young adults (with the average age of 23) who were followed for as many as six years reported that those attending religious services at least weekly at baseline were nearly one-third less likely to develop a depressive order during the six-year follow-up.99

If spiritual beliefs and practices reduce alcohol and drug use, this should lead to greater human flourishing and warfighter readiness. In the systematic review described above, a total of 278 studies examined the relationship between religiosity/spirituality and alcohol use.100 Of those, 240 (86 percent) found significantly lower alcohol use, abuse, or dependence among those who scored higher on spiritual beliefs and practices. Nearly the same finding was reported for illicit drug use, where of 185 studies identified, 155 (84 percent) reported significantly lower levels of illicit drug use and abuse among those scoring higher on measures of religiosity/spirituality. Most of these studies involved young adults, such as high school students, college students, and those of military age. More recent research confirms these findings.101 For example, a 2017 National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study, which involved a nationally representative sample of 3,151 U.S. military veterans, found that those with high spirituality based on a five-item measure were 34 percent less likely to have a history of alcohol use disorder and 72 percent less likely to have a current alcohol use disorder.102

A number of studies have found lower rates of PTSD among those who are more religiously/spiritually involved.103 For example, in the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study described above, it was found that those scoring high on spiritual engagement were 54 percent less likely to report a lifetime history of PTSD and 70 percent less likely to indicate current PTSD.104

Greater spiritual involvement has also been associated with lower levels of inner conflict over committing moral transgressions in combat situations. This is true for both veterans and active-duty military servicemembers.105

The systematic review described above identified 141 quantitative studies that examine the relationship between religiosity and suicidal thoughts, attempts, and completions.106 Of those studies, 106 (75 percent) found significantly fewer suicidal thoughts, attempts, and completed suicides among those scoring higher on measures of religiosity/spirituality. Several more recent studies from the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health have found that frequency of religious attendance has consistently predicted a lower risk of death from suicide and from “diseases of despair” (i.e., deaths due to drugs, alcohol, or suicide). For example, in a 14-year prospective that followed nearly 90,000 women for risk of completed suicide, that risk was 84 percent lower among those attending religious services at least weekly at baseline compared to nonattendees.107 Similarly, researchers found that deaths from diseases of despair among 66,492 female health professionals followed for more than 16 years were almost 70 percent less common among those who were frequently involved in spiritual activities compared to the noninvolved. These researchers also followed 43,141 male health professionals for 26 years, finding that those who attended religious services at least weekly at baseline were almost 50 percent less likely to die from a death of despair.108 Even larger effects have been found in the general U.S. population, in which an 18-year follow-up of more than 20,000 adults (a national random sample) found a 94-percent reduction in risk of completed suicide among those attending religious services at least twice per month.109 In fact, a meta-analysis of nine studies involving 2,339 suicide cases and 5,252 matched controls found a 62-percent reduction in suicide risk among those who were more spiritually involved.110 It is acknowledged that these studies do not involve active-duty military servicemembers, although the results likely generalize to this group as well, in which there are currently serious and worsening problems with regard to suicide.111 Every one of these mental health conditions described above (depression, substance use disorders, PTSD, and moral injury) increase suicide risk. As a result, the cumulative effect of spiritual involvement on these disorders is likely to have a huge impact on suicide risk, as the research above demonstrates.

Mental and behavioral problems affect physical health as well, and they accumulate over time.112 This is true for young adults aged 18–24, who are likely to join the military. The systematic review described above analyzed hundreds of quantitative studies examining the relationship between religiosity and physical health.113 More than one-half of the studies found that those scoring higher on religious/spiritual beliefs and practices experienced less heart disease, lower blood pressure, lower rates of stroke, less cognitive decline with aging, increased concentration, less physical disability, better immune function, lower levels of proinflammatory markers, lower levels of stress hormones, lower death rates from cardiovascular disease and cancer, and lower mortality from any cause. Since 2010, these findings have been replicated and published in some of the world’s best public health journals by some of the world’s top public health research institutions.114

Financial and Material Stability

Spiritual involvement is significantly more common among those of lower socioeconomic status. However, if a young person is active in a spiritual community, this has been shown to improve their chances of obtaining a good education, including a higher likelihood of completing high school and graduating from college.115 This is likely because families that are more involved in spiritual activities make a considerable effort to instill moral and ethical values and are more likely to monitor youth activities. As a result, education is less likely to be interrupted by alcohol or drug addiction, teen pregnancy, or delinquent activities. Youth who complete their education are more likely to get a good job, and if they join the military, a higher rank and better pay. In addition, most spiritual traditions emphasize being responsible, being dependable, and working hard, often encouraging individuals to help others at work. As a result, those engaged in spiritual activities have also been found to be more satisfied and productive at work.116

Conclusion

The DON needs to operationalize spiritual readiness and vigorously promote the engagement of both Stoic philosophy and religious/spiritual practice at the unit level to enhance overall health and warfighter readiness. As indicated by successive Commandants of the Marine Corps, spirituality is vital to force readiness and health, in that it contributes to enduring hardship and winning battles. Spirituality helps form character—it is a deep well that is drawn from by sailors and Marines to overcome great adversity and prevail—and it serves as a critical element of combat success. Throughout history, military commanders have recognized that the spirit is a force that can inspire and steel resolve, thereby affecting the outcome on a battlefield. To this end, the U.S. military has established initiatives to bring the spiritual element into play with greater acknowledgment. Too often, however, the various Service branches have focused on hardware and technology, and that which affects the inner life of the servicemember, such as Stoic philosophy and religion, has been deemphasized to the point of irrelevance in the modern military and viewed as something that is strictly a personal matter. The DON should view spiritual readiness as a component of fitness integral to combat readiness, on equal par with medical and physical readiness.

The data presented in this article demonstrates the value of religion/spirituality as a strengthening factor with a meaningful positive impact on warfighter readiness and on reducing destructive behaviors. Religion/spirituality has a demonstrable impact on happiness and life satisfaction, meaning and purpose, character and virtue, close social relationships, and mental and physical health. It also lowers the risks of substance use problems, PTSD, conflict about moral injury, and suicide. It serves as a strengthening agent that fortifies and enhances character development, warrior toughness, and resiliency. All of these outcomes are goals of any military commander. By embracing holistic health, the U.S. naval Services can expand a key competitive advantage of toughness and resiliency across all ranks and rates/military occupational specialties, positively affecting the warfighter’s ability to perform honorably and at their highest level. In the end, Stoic philosophy and religion/spirituality are competitive advantages that can serve a twenty-first-century military strategy by leveraging the concept of holistic health. This rethinking can help build character and toughness, instill critical core values, and optimize warfighter readiness within the DON.

Endnotes

- All Marine Corps Activities (ALMAR) 027/20, Resiliency and Spiritual Fitness (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, 3 December 2020).

- For the Marine Corps’ definition of spiritual fitness, see Spiritual Fitness Leader’s Guide (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, 2020), 8. “Spiritual Fitness is the identification of personal faith, foundational values, and moral living from a variety of sources and traditions that help Marines live out Core Values of Honor, Courage, and Commitment, live the warrior ethos, and exemplify the character expected of a United States Marine.”

- ALMAR 027/20, Resiliency and Spiritual Fitness.

- ALMAR 033/16, Spiritual Fitness (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, 3 October 2016).

- ALMAR 033/16, Spiritual Fitness.

- RAdm Gregory N. Todd, CHC, USN, “From Character to Courage: Developing the Spirit of the 21st Century Warfighter,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 147, no. 4 (April 2021). See also Cdr David A. Daigle, CHC, USN, LtCol Daniel V. Goff (Ret), and Lt Bradley Lawrence, USN, “From Character to Courage: The Importance of Spirituality in Maximizing Combat Readiness and Warfighter Resiliency of Marines in the 21st Century,” Marine Corps Gazette 106, no. 11 (November 2022): 83–87; Cdr David A. Daigle, CHC, USN, LCdr William M. Schweitzer, CHC. USN, and Maj Marianne C. Sparklin, “Spiritual Readiness in the Age of EABO: Closing the Gap between the Commandant’s Intent for Spiritual Fitness and the Commander’s Implementation at the Small Unit Level,” Marine Corps Gazette 106, no. 11 (November 2022): 72–77; and David A. Daigle and Daniel V. Goff, “Beyond Lawyer Assistance Programs: Applying the United States Marine Corps’ Concepts and Principles of Spiritual Fitness as a Means towards Increasing the Health, Resiliency, and Well-Being of Lawyers—while Restoring the Soul of the Profession,” Journal of Catholic Legal Studies 59, no. 1 (2020): 50–91.

- Gen David H. Berger, Commandant’s Planning Guidance: 38th Commandant of the Marine Corps (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, 2019).

- Daigle and Goff, “Beyond Lawyer Assistance Programs,” 86–87. In general, the value of spiritual fitness and its impact on readiness is neither widely understood nor are the potential benefits fully appreciated. For instance, the authors conducted an informal survey at Marine Aircraft Group 29 in 2020. Despite decades of combined experience, none of the respondents, who were senior leaders, were aware of the Commandants’ ALMARS on spiritual fitness and spiritual resiliency.

- A discussion of the establishment and free exercise clauses within the U.S. military are beyond the scope of this article. For further discussion, see Julie B. Kaplan, “Military Mirrors on the Wall: Nonestablishment and the Military Chaplaincy,” Yale Law Journal 95, no. 6 (May 1986): 1210–36, https://doi.org/10.2307/796524; Maj Michael J. Benjamin, USA, “Justice, Justice Shall You Pursue: Legal Analysis of Religion Issues in the Army,” Army Lawyer (November 1998): 1–18; Cdr William A. Wildhack III, CHC, USNR, “Navy Chaplains at the Crossroads: Navigating the Intersection of Free Speech, Free Exercise, Establishment, and Equal Protection,” Naval Law Review 51 (2005): 217–51; Richard D. Rosen, “Katcoff v. Marsh at Twenty-Two: The Military Chaplaincy and the Separation of Church and State,” University of Toledo Law Review 38 (2006–07): 1137–78; Benjamin D. Eastburn, “Hold that Line!: The Proper Establishment Clause Analysis for Military Public Prayers,” Regent University Law Review 22 (2009–10): 209–32; Capt Malcolm H. Wilkerson, USA, “Picking Up Where Katcoff Left Off: Developing a Framework for a Constitutional Military Chaplaincy,” Oklahoma Law Review 66, no. 245 (2013): 245–86, http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2444514; and Jonathan S. Sussman, “Prayer for Relief: Considering the Limits of Religious Practices in the Military,” Roger Williams University Law Review 20, no. 1 (Winter 2015): 75–118.

- Daigle, Schweitzer, and Sparklin, “Spiritual Readiness in the Age of EABO,” 74. This asserts that a lack of attention or disconnect toward spiritual fitness may largely be attributable to the hard reality of competing priorities that a commander faces.

- Daigle and Goff, “Beyond Lawyer Assistance Programs,” 83–84. This recognizes that the spiritual aspect of overall fitness and well-being often takes a secondary role to physical training, mental preparation, education, and unit exercises when preparing for combat despite the fact that available evidence supports the hypothesis that spiritual fitness creates better outcomes and behaviors during combat or in garrison.

- Daigle and Goff, “Beyond Lawyer Assistance Programs,” 86–87.

- Marine Administrative Message (MARADMIN) 677/21, FY-22 Professional Development Training Course for Chaplains and Religious Program Specialists (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, 30 November 2021). The genesis for this article was the FY-22 Navy Chaplain Corps’ Professional Development Training Course on building spiritual readiness in the Department of the Navy. The mission was to build spiritual readiness with an in-depth review of spirituality from a Stoic philosophical perspective as well as spirituality from mental health and religious perspectives.

- Daigle, Schweitzer, and Sparklin, “Spiritual Readiness in the Age of EABO,” 72. This notes the role and importance of spirituality as traditionally understood within the Marine Corps. Although Stoicism is highlighted in this article for its value as a strengthening factor, the authors do not imply that Stoicism is necessarily superior to other philosophical and religious traditions. That said, the value of Stoicism is widely recognized by many leaders in the Department of the Navy and is emphasized to bring awareness to it as one of many means to resource spiritual fitness development. However, it must be noted that Stoicism is only one of many philosophies, religions, and belief systems, and it remains the choice of the individual to select what they believe will aid in their spiritual fitness.

- Nancy Sherman, Stoic Wisdom: Ancient Lessons for Modern Resilience (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021). See also Liam Guerin, “Modern Stoicism and Its Usefulness in Fostering Resilience,” Crisis, Stress, and Human Resilience: An International Journal 3, no. 4 (March 2022): 138–43.

- Sherman, Stoic Wisdom, 1–3.

- Nancy Sherman, Stoic Warriors: The Ancient Philosophy behind the Military Mind (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007). This investigates what makes Stoicism so compelling to the military mind not only for its guiding principles to face the hardships of life but also as a way to develop a virtuous military character and instill core values.

- Pascal Price, “Is Stoicism an Appropriate Philosophy for the Military?,” Cove, 29 August 2020.

- Daigle, Schweitzer, and Sparklin, “Spiritual Readiness in the Age of EABO,” 73. This remarks that resiliency is not merely a matter of hardening networks and enhancing weapon systems to defend against kinetic or cyberattacks, but that it must also be present at every level of the human warfighter to rebound from strife faced in and out of combat.

- Daigle, Schweitzer, and Sparklin, “Spiritual Readiness in the Age of EABO,” 73.

- Price, “Is Stoicism an Appropriate Philosophy for the Military?”

- Benjamin Kohlmann, “Intellectual Curiosity and the Military Officer,” Small Wars Journal, 24 January 2013. For a list of Gen Mattis’ favorite books, see Jim Mattis and Bing West, Call Sign Chaos: Learning to Lead (New York: Random House, 2019), 258–59.

- Marcus Aurelius, Meditations: A New Translation, with an Introduction by Gregory Hays (New York: Modern Library, 2002). See also “If You Don’t Read, You’re Functionally Illiterate,” Daily Stoic Emails, 30 January 2020. This relates that “General James Mattis is part of a long line of tradition of Stoic warriors. Just as Frederick the Great carried the Stoics in his saddlebags as he led his troops, or Cato proved his Stoicism by how he led his own troops in Rome’s Civil War, Mattis has long been known for taking Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations with him on campaign.” See also Louis Markos, “Why I Would Become a Stoic if Jesus Hadn’t Risen from the Dead,” Gospel Coalition, 21 January 2019. This asserts that “though Aurelius’s Meditations is the best-known Stoic work, the most accessible, and the best place for the modern reader to start, is the Enchiridion (or handbook) of Epictetus.”

- Guerin, “Modern Stoicism and Its Usefulness in Fostering Resilience,” 139–40.

- Paul Szoldra, “Mattis: This Is the One Book Every American Should Read,” Task and Purpose, 26 September 2018.

- Mattis and West, Call Sign Chaos.

- Mattis and West, Call Sign Chaos, 12. This also notes that Mattis believes it is the solemn duty of military leaders to read in order to learn from others.

- Carrie-Ann Biondi, “Critical Review Essay of Nancy Sherman’s Stoic Warriors,” Democratiya 11 (Winter 2007). See also Epictetus, The Enchiridion of Epictetus, trans. W. A. Oldfather (Morrisville, NC: Lulu, 2020). This asserts that for Stockdale, the Stoic philosopher Epictetus was particularly important during his imprisonment as a POW.

- Epictetus, The Enchiridion of Epictetus. This asserts that while Stockdale used Stoicism as an effective means to deal with all manners of adversity, including torture, Stoicism goes beyond bearing suffering.

- Taylor Baldwin Kiland and Peter Fretwell, “From Stockdale to Crozier, History Has a Way of Avenging the Humbled and Humbling the Proud,” War on the Rocks, 20 April 2020.

- VAdm James B. Stockdale, USN (Ret), A Vietnam Experience: Ten Years of Reflection (Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 1984). This notes that Stockdale was a “patriot and a philosopher-warrior” and that Americans should celebrate him.

- For more information on the U.S. Naval Academy’s Stockdale Center for Ethical Leadership, see “Stockdale Center for Ethical Leadership,” U.S. Naval Academy, accessed 14 March 2023. For more information on the U.S. Naval War College’s Stockdale Leader Development Concentration, see “Stockdale Leader Development Concentration,” U.S. Naval War College, accessed 14 March 2023.

- VAdm James B. Stockdale, USN (Ret), Stockdale on Stoicism II: Master of My Fate (Annapolis, MD: Center for the Study of Professional Military Ethics, U.S. Naval Academy, 2001), 2.

- For a good introduction of Stoicism, see John Sellars, Stoicism (London: Routledge, 2006), https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315712093.

- Aurelius, Meditations, 7.

- Pierre Hadot, The Inner Citadel: The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius, trans. Michael Chase (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998).

- Epictetus, The Enchiridion of Epictetus, part 5.

- See “USMC Human Performance Branch,” marines.mil, accessed 14 March 2023.

- Bertrand Russell, A History of Western Philosophy (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1945), 252–57.

- Epictetus, The Enchiridion of Epictetus, part 31. See also Aurelius, Meditations, 149–50. Aurelius writes, “Except that we also have a gift, given us by Zeus, who founded this community of ours. We can reattach ourselves and become once more components of the whole.”

- Frederick Clifton Grant, “St. Paul and Stoicism,” Biblical World 45, no. 5 (May 1915): 268–69, https://doi.org/10.1086/475275.

- Richard E. Crouter, “H. Richard Niebuhr and Stoicism,” Journal of Religious Ethics 2, no. 2 (Fall 1974): 129–46. See also “Reinhold Niebuhr (1892–1971),” in John Bartlett, Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations, 17th ed., ed. Justin Kaplan (Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 2002), 735. This attributes the prayer to Niebuhr in 1943.

- Russell, A History of Western Philosophy, 253.

- Epictetus, The Enchiridion of Epictetus, 9.

- Alejandra Ellison-Barnes, Sara Johnson, and Kimberly Gudzune, “Trends in Obesity Prevalence among Adults Aged 18 through 25 Years, 1976–2018,” Journal of the American Medical Association 326, no. 20 (November 2021): 2073–74, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.16685.

- Jahara W. Matisek, “Does the U.S. Military Have a Fitness Problem?,” National Interest, 22 February 2020.

- Daniel B. Bornstein et al., “Which U.S. States Pose the Greatest Threats to Military Readiness and Public Health?: Public Health Policy Implications for a Cross-Sectional Investigation of Cardiorespiratory Fitness, Body Mass Index, and Injuries among U.S. Army Recruits,” Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 25, no. 1 (January/February 2019): 36–44, https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000000778.

- Lara Seligman, Paul McLeary, and Lee Hudson, “Lawmakers Press Pentagon for Answers as Military Recruiting Crisis Deepens,” Politico, 27 July 2022.

- According to the Oxford Reference Library, the phrase fog of war “is often attributed to Clausewitz, but is in fact a paraphrase of what he said: ‘War is the realm of uncertainty; three quarters of the factors on which action in war is based are wrapped in a fog of greater or lesser uncertainty’.” “Fog of War,” Oxford Reference Library, accessed 14 March 2023. For the original, see Carl von Clausewitz, On War, trans. and eds. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976).

- Epictetus, The Enchiridion of Epictetus, part 8.

- Helen Herrman et. al., “What Is Resilience?,” Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 56, no. 5 (May 2011): 259, https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371105600504.

- Ryan Holiday, The Obstacle Is the Way (New York: Penguin, 2014), 150–55.

- For more on Stockdale’s life, see Navy Administrative Message (NAVADMIN) 055/22, Navy Calls for 2022 Stockdale Leadership Award Nominations (Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, 7 March 2022). This NAVADMIN succinctly encapsulates Stockdale’s leadership and contributions.

- Stockdale, Stockdale on Stoicism II, 5.

- Stockdale’s citation for the Medal of Honor is as follows: “For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while senior naval officer in the prisoner-of-war [POW] camps of North Vietnam. Recognized by his captors as the leader in the [POWs’] resistance to interrogation and in their refusal to participate in propaganda exploitation, [RAdm] Stockdale was singled out for interrogation and attendant torture after he was detected in a covert communications attempt. Sensing the start of another purge, and aware that his earlier efforts at self-disfiguration to dissuade his captors from exploiting him for propaganda purposes had resulted in cruel and agonizing punishment, [RAdm] Stockdale resolved to make himself a symbol of resistance regardless of personal sacrifice. He deliberately inflicted a near-mortal wound to his person in order to convince his captors of his willingness to give up his life rather than capitulate. He was subsequently discovered and revived by the North Vietnamese who, convinced of his indomitable spirit, abated in their employment of excessive harassment and torture toward all the [POWs]. By his heroic actions, at great peril to himself, he earned the everlasting gratitude of his fellow [POWs] and of his country. [RAdm] Stockdale’s valiant leadership and extraordinary courage in a hostile environment sustain and enhance the finest traditions of the U.S. Naval Service.” “James Bond Stockdale,” Congressional Medal of Honor Society, accessed 14 March 2023.

- Jim Collins, Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap . . . and Others Don’t (New York: HarperBusiness, 2006), 83–85.

- James B. Stockdale, Courage under Fire: Testing Epictetus’s Doctrines in a Laboratory on Human Behavior (Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace, Stanford University, 1993), 18.

- Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, 2d ed., trans. Terence Irwin (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 1999). Some translate the four cardinal virtues as prudence, justice, temperance, and fortitude. The authors here have elected to choose the translation of them as wisdom, justice, temperance, and courage, to use more modern language. These cardinal virtues are traditional for the Greeks, including Plato as well as Aristotle. They are included among the virtues in Aristotle’s ethical system, insofar as it is expressed in the Nicomachean Ethics; however, they do not constitute the whole of that system. See also Plato, The Republic, 2d ed., trans Sir Henry Desmond Pritchard Lee (London: Penguin, 2007), 428.

- Gen David H. Berger, Force Design 2030 (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, 2020).

- Epictetus, The Discourses of Epictetus; with the Enchiridion and Fragments: Translated, with Notes, a Life of Epictetus, and a View of His Philosophy, trans. George Long (London: George Bell and Sons, 1906), book 2, chapter 17.

- This notion aligns with the “Get Real, Get Better” initiative of the current chief of naval operations, Adm Michael M. Gilday, that was unveiled in 2022. It is a call to action for every Navy leader to apply a set of Navy-proven leadership and problem-solving best practices that empower personnel to achieve exceptional performance. See “Get Real, Get Better,” navy.mil, 13 October 2022.

- Nancy Sherman, “Educating the Stoic Warrior,” Whitehall Papers 61, no. 1 (2004): 110, https://doi.org/10.1080/02681300408523011.

- Daigle and Goff, “Beyond Lawyer Assistance Programs,” 83–84.

- Lisa Ferdinando, “Pentagon Releases New Policy on Nondeployable Members,” DOD News, 16 February 2018.

- Ferdinando, “Pentagon Releases New Policy on Nondeployable Members.”