Lieutenant Colonel Nathan A. Jennings, USA, PhD

1 September 2023

https://doi.org/10.36304/ExpwMCUP.2023.10

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: The performance of the Israeli 143d Reserve Armored Division in the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, also known as the Yom Kippur War, provides a compelling example of a combined arms force that recovered from initially devastating losses to enable a complicated, if high-risk, counteroffensive across the Suez Canal to seize strategic initiative and end the war on favorable terms. This achievement, which can be examined through the operational tenets of agility, convergence, endurance, and depth, holds insights for modern militaries as gap-crossing operations remain a central requirement for Joint forces to achieve offensive success in major campaigns.

Keywords: 1973 Arab-Israeli War, Yom Kippur War, Israel, Egypt, Syria, Sinai, Suez Canal, gap crossing, river crossing, bridges, tanks, Ariel Sharon

The operational requirement to forcefully traverse river barriers to enable larger offensive campaigns has remained a fundamental combat task since the first soldiers marched to war. U.S. Joint doctrine defines a gap crossing operation as the requirement to “project combat power over linear obstacles or gaps” with “dedicated assets from all of the warfighting functions.” The U.S. military is currently modernizing its capabilities to negotiate this age-old problem with new technologies.1 While crossing over water obstacles in general and large bodies of water in particular remains an exceedingly challenging undertaking for any ground formation, the problems multiply when adversaries contest the bridgehead with fortifications, arrayed fires, and counterattacks. This means that the tactical bridging of defended river barriers, especially in regions such as Eastern Europe and East Asia that feature byzantine drainage basins, will continue to define success, and failure, for U.S. forces in expansive land campaigns.

History is replete with examples of expeditions that executed dynamic gap crossings to enable offensive schemes of maneuver. While the U.S. Third Army’s traversing of the Moselle River in Western Europe in 1944 and the 1st Marine Division’s fording of the Han River on the Korean peninsula in 1950 represent compelling examples, the Israel Defense Forces’ (IDF) crossing over the Suez Canal in 1973—and its 143d Reserve Armored Division’s role in particular—offers among the most relevant of case studies for modern warfare. Featuring a conflict that stunned the world with its sudden vacillations and shocking attrition, the campaign required the IDF to recover from devastating losses to Arab standoff firepower and conduct a complicated, if high-risk, bridging of the canal in the face of fierce resistance.2 This counteroffensive, which compelled the Israelis to penetrate, disintegrate, and exploit sophisticated antiarmor and antiair missile defenses, ultimately paralyzed their adversaries and set conditions for a favorable armistice.

This campaign, which deeply informed the development of North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) doctrine and weaponry during the late Cold War era, holds new value for the U.S. Joint forces today as the U.S. Army and Marine Corps modernize their capabilities. With the imperative to execute gap crossings within larger offensives remaining a critical task for both Services, the achievements—and mistakes—of the Israeli 143d Armored Division can inform future battlefield success.3 The assessment, when framed by the U.S. Army’s newly introduced doctrinal tenets of agility, convergence, endurance, and depth, can yield operational insights—as opposed to replicable lessons—for how Joint forces can cross barriers in the most challenging of circumstances.4 This timeless requirement, even as positional and attritional trends in warfare seem to be increasing the cost of maneuver, will remain essential for power projection in the twenty-first century.

1973: War on Two Fronts

The 1973 Arab-Israeli War, also known as the Yom Kippur War, exploded in October 1973 against the backdrop of a confident IDF that had proven historically dominant over its proximate Arab competitors. In 1948, 1956, and especially 1967, the nascent Jewish state had increasingly demonstrated military overmatch during a changing constellation of hostile neighbors while catalyzing bitter enmity across the Muslim world. The 1967 Six-Day War saw the IDF maximize aggressive armored maneuver with air interdiction strikes to win decisively, with relatively few losses, and achieve a massive expansion of Israeli-controlled territory that included occupation of the Sinai Peninsula, the Golan Heights, and the West Bank. As argued by historian Michael Howard, the campaign provided a “text-book illustration” for the application of timeless principles that included “speed, surprise, concentration, security, information, the offensive, [and] above all . . . training and morale.”5

However, this situation changed dramatically on 6 October 1973, when, following a dispiriting War of Attrition (1967–70) along the Sinai front, Egypt and Syria commenced surprise offensives that shattered Israeli assumptions about the tactical primacy of fast-moving armor and aircraft. Seeking to regain both national pride and lost territory, Egypt executed a rapid crossing of the Suez Canal with two corps-size armies comprising more than 100,000 troops and 1,000 tanks with innovative tactical bridging, which overwhelmed the Israeli defensive line along the east bank. In the north, the Syrian Army simultaneously attacked into the Golan Heights with more than 1,200 tanks and massive artillery barrages to threaten the Jewish heartland. On both fronts, the Arab forces employed Soviet-provided surface-to-air missiles (SAM), AT-3 Saggar antitank missiles, and rocket-propelled grenades to devastate the hasty counterattacks by Israeli ground and air forces. During the next two days, the IDF faced cascading crises as it suffered heavy damage or destruction to 40 percent of its armor and lost 30 attack aircraft to the surprisingly lethal array of stand-off weaponry.6

With disasters unfolding to the north and south, the Jewish people mobilized for war on their holiest of days, Yom Kippur. As part of the Sinai defense, the 143d Reserve Armored Division, commanded by veteran IDF major general Ariel Sharon, assembled its soldiers and tanks in staging areas near Beersheba east of the Sinai. Comprising the 14th Armored Brigade, led by Colonel Amnon Reshef; the 421st Armored Brigade, led by Colonel Haim Erez; the 600th Armored Brigade, led by Colonel Tuvia Raviv; and the 87th Reconnaissance Battalion, led by Lieutenant Colonel Ben-Zion “Bentzi” Carmeli, the division mobilized with limited infantry and artillery support due to the IDF’s prioritization of M48 Patton and M60-type main battle tanks with assumptions of dominating air support.7 Despite these combined arms limitations, the division’s senior officers arrived with an abundance of combat experience from previous wars that would prove crucial in the coming weeks, as they, like the rest of the IDF, would be compelled to recover from severe losses, learn from mistakes, and seek to retake operational initiative.8

Yet, this success lay in the future, and during the coming days the 143d Armored Division would pay a heavy price for its overconfidence. Following the initial failed counterattacks of the IDF’s 252d Armored Division on 7 October, and even as IDF forces on the Golan front and the Israeli Navy in the Mediterranean Sea began to reverse the tide of the war in their respective theaters, the IDF Southern Command commenced a larger counterattack on 8 October to retake the east bank of the Suez Canal and potentially cross over into Africa. The resulting debacle saw the Israeli 162d Armored Division under Major General Avraham “Bren” Adan suffer operational loss of or degradation to approximately 83 of 183 tanks to the Egyptian Second Army, and it likewise saw Sharon’s command endure the loss or debilitation of more than 50 tanks against the Egyptian Third Army in a haphazard attack the next day. While skirmishing would continue, one fact had become clear: the vulnerability of main battle tanks and fighter-bombers to a new array of static and mobile missile systems had upended notions of modern warfare.9

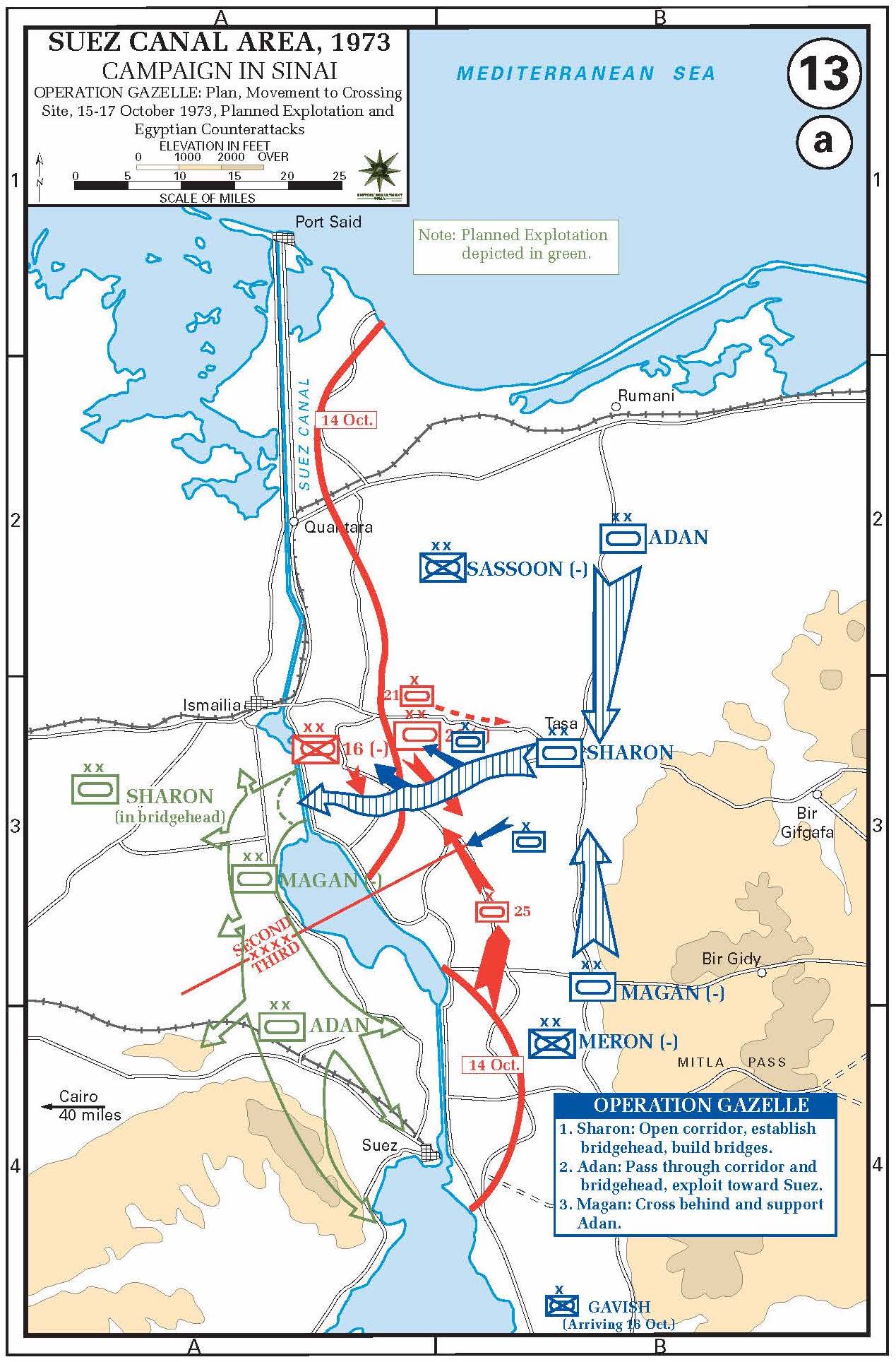

Despite their remarkable success, the Egyptians, at the urgent demands of the Syrians to relieve pressure on the collapsing Golan front, soon conducted an ill-advised venture of their own. On 14 October, the Second and Third Armies, reinforced by Cairo’s operational reserve of two armored divisions that had crossed over the Suez Canal to lead the assault, moved out of their protected positions and attacked deeper into the Sinai to seize key crossroads and passes. In the resulting clash of armor—the largest since the Battle of Kursk in 1943—the Arabs lost more than 250 tanks as they assaulted into prepared engagement areas that were overwatched by Israeli armored teams with support from coordinated artillery and dedicated air strikes.10 The Israeli 143d Division, defending in the center with 140 tanks, repelled the Egyptian 21st Armored and 16th Infantry Divisions while destroying numerous T-55 and T-62-series main battle tanks. By day’s end, the IDF had stunned the Egyptian Army and stood ready to attempt the most difficult of operations: a penetration of the canal defense to cripple the enemy and end the war on favorable terms.11

Figure 1. Israeli Centurion Sho’t tank in the Sinai Desert, 1973

Source: official Israeli Defense Forces photo.

Setting Conditions for Crossing

The defeat of the Egyptian attack established ideal conditions for an ambitious, if high-risk, Israeli counteroffensive. With the movement of the Egyptian reserve armor to the east bank of the Suez Canal, essentially turning the Arab front into more of a linear defense than a defense-in-depth, the IDF command realized that it could now attempt a crossing over the canal with intent maneuver behind enemy lines in Africa. With the Israeli 162d, 252d, and 143d Armored Divisions now recovered from their earlier battles and buttressed with reinforcements, the IDF Southern Command tasked Sharon to bridge the canal and then pass through the other two divisions to the west bank. Once beyond the Egyptian defensive lines, the lead Israeli forces were to clear proximate SAMs to enable Israeli Air Force engagement and then break out with deep maneuver to the north and south to sever Egyptian lines of communication and fatally isolate the Second and Third Armies from their strategic support areas.12

The decisive point of the counteroffensive would be the destruction of a series of Egyptian air defenses at the center of the Suez Canal as part of the crossing operation, which would allow the IDF to restore the multidomain approach that had marked their success in previous wars. With the Israeli Air Force having lost 54 aircraft to enemy fire in just the first five days of combat, Israeli pilots had been forced to accept a more limited role and leave their ground counterparts bereft of the aggressive air support required to enable rapid and forceful maneuver.13 The crossing plan, called Operation Stouthearted Men, would consequently employ the 143d Armored Division to create, as required by modern U.S. Joint doctrine, the “freedom of action” required for Israeli pilots to regain the initiative and begin a systematic disintegration of not only the enemy’s SAM network but also their entire order of battle.14 In contrast, the Israeli Navy, comprising a sophisticated missile boat fleet, had enjoyed greater success when it utterly destroyed both the Egyptian and Syrian fleets near their harbors in the first days of the war and thereby precluded Arab options for naval resupply or amphibious envelopment.15

In preparation for the imminent offensive, the IDF Southern Command selected the 143d Armored Division as the initial main effort and accordingly reinforced it to execute a complicated series of tasks and movements. Learning from early mistakes when Israeli armor had attacked with minimal combined-arms capability, the theater commander provided Major General Sharon with the 247th Paratrooper Brigade, the 107th and 208th Air Defense Battalions, the 582d Antiarmor Battalion, the White Bear and Shaked Reconnaissance Battalions, and 12 cannon and rocket battalions that included the 215th Artillery Group to allow greater tactical flexibility and agility. In terms of combat support, the division would employ the 812th Supply Group, the 504th Medical Battalion, the 229th Engineer Battalion, and, crucially, given the nature of the operation, elements of the 630th, 634th, and 605th Bridging Battalions to expand operational endurance and extend operational reach.16

Operation Stouthearted Men, essentially comprising a corps-level gap crossing effort, required the 143d Armored Division to commence the dangerous plan by executing a sequence of interrelated tasks that included clearing the route to the identified point of crossing; escorting three separate engineer convoys from different locations to the crossing site; ensuring the successful projection of boat, raft, pontoon, and fixed-bridge crossings; repelling expected enemy counterattacks against the initial lodgment; and, perhaps most critically, clearing proximate enemy SAMs on the far embankment, all to allow the uncommitted 162d Armored Division to pass through and execute the breakout with Israeli Air Force support. As later articulated by Sharon, “The main problem was how to reach the water and establish the bridgehead in the same night . . . [for] if we lost surprise about our intentions we no doubt would have found quite a number of tanks waiting for us on the west side.”17

Escorting the various bridging systems to the point of crossing at a gap between the Egyptian Second and Third Army’s positions just north of the Bitter Lake—which the 87th Reconnaissance Battalion had found to be fortuitously undefended—would prove unexpectedly difficult. While the 247th Paratrooper Brigade under the command of Colonel Danny Matt would easily carry rubber boats on half-tracks cross-country and motorized rafts could move independently, the modular pontoon bridge and 400-ton roller bridge had to be escorted mostly along a single-access road through the Sinai desert. The roller bridge, which had been purpose-built by the IDF for such an event, required 12 tanks to pull it to the canal. With the 421st Armored Brigade dispersing as escorts, Sharon tasked the 600th Armored Brigade to execute a feint toward the front of the Egyptian 21st Armored Division that defended north of the selected point of crossing. The 143d Armored Division’s third tank brigade, the 14th Armored Brigade, which also happened to be a regular army brigade, would attack in a sweeping maneuver from south to north to clear the vital Akavish and Tirtur road junctions of any enemy presence to allow safe passage for the cumbersome engineer convoys.18

Map 1. Israeli penetration to the Suez Canal, 1973

Source: courtesy of the U.S. Military Academy.

The 143d Armored Division initiated the crossing on the night of 15 October, a day after defeating the Egyptian attack into the Sinai, with the 600th Armored Brigade feinting toward the Egyptian 21st Armored Division at the center of the enemy’s canal defense as the 14th Armored Brigade attacked from the southeast to clear the required routes. While the deception action would prove moderately successful, the attempt to clear the roads would turn into an attritional disaster that threatened to stymie the IDF Southern Command’s entire scheme of maneuver. Operating on faulty intelligence, the 14th Armored Brigade, without adequate infantry support, advanced during the night headlong into entrenched Egyptian infantry and armor that were much farther south than previously believed. In what would become known as the Battle of the Chinese Farm, named for the agricultural research complex that provided numerous trenches and fighting positions to the defenders, the contest devolved into a destructive fight that left the area littered with burning tanks and dying soldiers.19

Simultaneous to the chaos erupting to the north, the 247th Paratrooper Brigade advanced cross-country on half-tracks with its complement of boats to make the initial crossing. The Israeli soldiers reached a fortified post at the crossing point called Fort Matzmed, which would be nicknamed the “Yard,” at 0115 hours on 15 October. After fortuitously encountering no resistance, the Israelis quickly launched into the canal and reached the west bank with no difficulties. Leveraging the element of surprise, but still without aerial or armored support, the brigade established a foothold on the far embankment and prepared to receive the expected Egyptian counterattack.20 With this advancement, even as the Battle of the Chinese Farm raged and the bridging convoys fell behind schedule due to mechanical and logistical failures, the IDF, after suffering immense losses and fearing national defeat, had initiated the first step in decisively ending the war.

Fighting for Canal Access

With some 143d Armored Division elements now establishing the lodgment, others fighting to clear vital routes, and still more struggling to move the critical bridging assets to the Yard, Major General Sharon’s command was now stretched extremely thin by the divergent missions across a 10-kilometer sector. At dawn on 16 October, it became apparent that the 14th Armored Brigade had stumbled into a chaotic maze of agricultural constructions and had paid a heavy price for tactical intelligence failures during five successive assaults on the Egyptian lines. Much of the fighting had taken place at close ranges, with tanks firing at each other from just meters away and hand-to-hand fighting erupting between soldiers on the ground. Despite the slow progress, however, the 14th Armored Brigade had cleared parts of the route by 0840 that morning. The effort, which drew aggressive counterattacks from the battered Egyptian 21st Armored Division, cost the Israeli brigade 70 of 97 tanks damaged or destroyed and approximately 300 killed and 1,000 wounded across the division.21

Even as the fight exploded at the Chinese Farm, the 143d Armored Division negotiated another problem throughout the night of 15 October: the two primary bridge convoys had become mired, broken, and fallen far behind schedule. The 421st Armored Brigade, which had divided its tank battalions to escort different convoys, assisted desperate Israeli engineers with moving the bridges as Sharon and the IDF Southern Command attempted to deconflict confusing reports. However, with the giant roller bridge completely breaking down at one point—sparking fears across the theater command of potential mission failure—the pontoon convoy continued its slow approach. Making matters worse, the approach routes to the Suez Canal were severely congested due to mixing of bridge convoys, escort tanks, supply vehicles, and the prepositioning of the entire 162d Armored Division in anticipation of exploiting the breakout. Despite the chaos, the motorized rafts, escorted by the 264th Armor Battalion, continued apace due to their ability to move independently away from the main routes.22

The self-propelled raft convoy reached the Yard at 0500 hours on 16 October. An hour and a half later, the first raft hit the water and, in short order, they ferried 20 tanks of the 421st Armored Brigade across the canal to reinforce the Israeli paratroopers’ precarious lodgment. At 1300 hours, the Israeli armor, despite having moved all night and just arrived, commenced what was to become one of the most important actions of the entire war. While in direct radio communication with the Israeli Air Force chief of staff, tank teams raided the cluster of SAM, air defense artillery, and radar sites, command nodes, and security elements at the center of the Egyptian defensive line. This action, which began the critical disintegration of the enemy’s heretofore impenetrable defensive network, would soon open a gap in the missile shield for Israeli McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II and Douglas A-4 Skyhawk attack aircraft to attack the exposed Arab positions.23 However, despite the apparent success, the 421st Armored Brigade’s tanks were hampered by shortages of fuel and ammunition as they balanced operational requirements with logistical constraints.24

Even as Israeli forces raided SAM sites in Africa, the problem at the Chinese Farm remained far from resolved. With the bridge convoys approaching the canal, the IDF Southern Command realized that it would take infantry to clear the Egyptian entrenchments. Assuming risk to the anticipated breakout and realizing that Sharon’s forces were overtasked, the command ordered the 162d Armored Division to assist with moving the pontoon bridge and receive the 35th Paratrooper Brigade to finally clear the Tirtur-Lexicon route. However, when the infantry arrived, they too would find difficulty with the Egyptian 21st Armored Division’s stubborn defense. Electing to attack without detailed intelligence, the paratroopers rushed into the assault, much as the 14th Armored Brigade had, and suffered more than 40 killed and 100 wounded.25 However, despite these losses and a recommitment of scarce armor to rescue the remains of the Israeli 890th Infantry Battalion, the bloodied brigade managed to occupy the Egyptians enough to allow the sectional pontoon convoy to pass through.

Throughout this period, as success remained uncertain, Israeli leaders in the Sinai theater fell into bitter acrimony about differing visions and priorities. While Sharon, who positioned himself forward at the canal, argued strenuously for an immediate breakout by all available forces, his higher command, which better understood the broader risks to the campaign, ordered a more cautious approach to assure continued access and prevent an epic disaster. This contrast crystalized at 1100 on 16 October, as advance tanks of the 143d Armored Division set out to raid enemy SAM sites, when the IDF Southern Command specifically and repeatedly ordered an angry Sharon to halt the ferrying of tanks across the canal. Though the forward commander protested vigorously that they were missing an opportunity to exploit Egyptian confusion, his superiors insisted that they must first reduce enemy presence at the Chinese Farm and ensure that the bridges would actually arrive, lest unforeseen disruptions strand precious IDF armor on the west bank.26

Crossing under Fire

The morning of 17 October saw the Israeli counteroffensive attain forward momentum as the complicated plan painstakingly came together. While the grinding attrition at the Chinese Farm had severely damaged the 14th Armored and 35th Paratrooper Brigades, their continued assaults had nevertheless worn down and eventually pushed back the Egyptian defenders to allow mostly unmolested access to the canal. At approximately 0600, the pontoons finally reached the bridgehead, and engineers began to assemble the modular sections. Unfortunately for the IDF, by this time, the Egyptian command had discovered the Israeli penetration and placed intense artillery and aircraft fire on the Yard. While this would prove a serious threat to the operation, with both rafts and pontoons sustaining heavy damage, the IDF engineers persevered to complete the project despite taking many casualties, as each side raced against time to either complete or block the crossing attempt.27

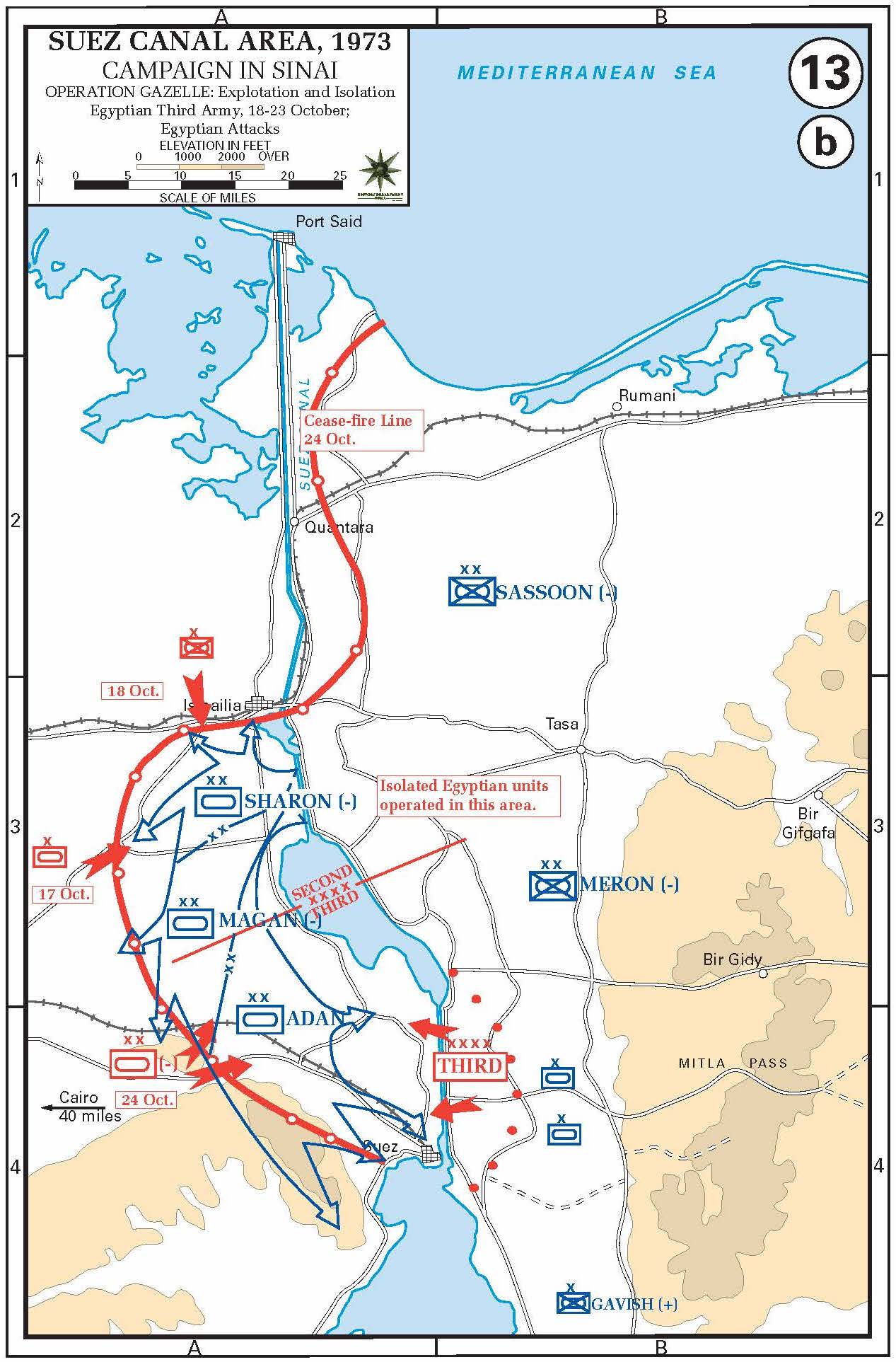

Map 2. Israeli exploitation in Egypt

Source: courtesy of the U.S. Military Academy.

The IDF’s assault at the center of the Egyptian defense did not go unnoticed in Cairo. Over the protests of his field commanders, Egyptian president Anwar Sadat ordered the Second and Third Armies to launch immediate counterattacks on the morning of 17 October to converge in the center on the east bank to shatter the Israeli crossing effort. With Sharon’s forces fully committed, the Israeli 162d Armored Division first blocked the Egyptian 21st Armored Division’s attack from the north and then pivoted south that afternoon to counter the assault of the 25th Independent Armored Brigade with its cutting-edge T-62 tanks. While the former formation lost 48 tanks in the attempt, the latter force, representing the most capable armored unit in the Egyptian Army, lost 86 of its 96 tanks as they blundered into a well-placed ambush. These new losses, when combined with attrition during the previous weeks, severely debilitated Egypt’s offensive potential.28

The defeat of the Egyptian counterattack, combined with continued disintegration of Egyptian air defenses, catalyzed panic in Cairo. In an act of desperation, the Egyptian high command committed its entire air force beginning on 18 October to repel the Israeli Air Force from the skies and salvage the spiraling situation. Unfortunately for the Arab nations, as the two sides clashed in 18 major aerial battles during the following days with an intensity not seen since World War II, the Israeli pilots employed superior skill and weaponry to virtually destroy Egyptian air power. When the Egyptian high command retrograded its vital SA-6 SAMs back to defend the capital region, Israeli aircraft were then allowed to place greater attention against Arab ground forces along the Suez Canal and destroy their tactical bridges. Harkening back to the 1967 Six-Day War, this resulted in a restoration of IDF air-ground cooperation that proved devastating for the defenders. Throughout this last phase of the war, Egypt lost more than 150 aircraft in contrast to just 15 for Israel.29

With the pontoon bridge now in place and secured by the 143d Armored Division, the 162d Armored Division, also called the “Steel Formation,” crossed into Africa at 2200 on 17 October with two armored brigades and attached artillery and infantry elements to complete the crossing by dawn. Though constant Egyptian shelling caused a dozen Israeli tanks to tumble into the canal and inflicted further casualties, Major General Adan’s forces nevertheless conducted a hasty passage of lines with Sharon’s troops and immediately attacked south to isolate the Egyptian Third Army in the Sinai. During the next two days, as elements of the 143d Armored Division and a third formation, the reconstituted 252d Armored Division under IDF major general Kalman Magen, massed to cross as well, the roller bridge finally arrived to establish a second and more reliable causeway to Africa. With Adan’s forces now driving south to seize Suez City and clearing SAM and artillery sites along the way, the 252d Armored Division attacked along their right to protect the IDF right flank and completed the encirclement by seizing Adabiya Port on the gulf coast on 24 October.30

Figure 2. Israeli bridge over the Suez Canal, 1973

Source: official Israeli Defense Forces photo.

Even as events progressed in the Sinai theater to the south, the IDF faced an additional threat in the form of a large-scale Iraqi and Jordanian intervention on the Syrian front in the north. As the IDF had defeated the Syrian Army with a counteroffensive that recaptured the Golan Heights and then invaded Syria proper in the first days of the war, continued stability and economized effort in the north would prove crucial for allowing Israeli strategic leaders to maintain the Sinai as the national priority. Consequently, when the Iraqi Army’s 3d and 6th Armored Divisions and Royal Jordanian Army’s 40th Armored Brigade attacked to reverse Arab fortunes, the coalition threatened not only to destabilize the Golan front but also to divert critical resources from precarious crossing underway at the Suez Canal. However, fortunately for Jerusalem, on 20 October the IDF Northern Command first shattered the Iraqi attack by destroying 120 tanks in a clever entrapment and then soundly defeated an ill-coordinated assault by the Jordanians to permanently stabilize the northern front. This victory then allowed the IDF general staff to transfer select forces, such as the 179th Armored Brigade, to reinforce the ongoing counteroffensive in the south.31

While Adan and Magen maneuvered south and IDF forces defended gains in Syria, the 143d Armored Division attacked north from the crossing to attempt to isolate the Egyptian Second Army from its own support areas. However, unlike his counterparts, Sharon would only make it approximately 6 kilometers north of the crossing before meeting stubborn Egyptian resistance among the agricultural complex at Orcha. Now employing combined arms tactics, as opposed to rushing in with unsupported tanks or infantry like before, the 143d Armored Division methodically reduced the entrenchments to grind north toward the city of Ismailia. However, after weeks of intense fighting and heavy losses, Sharon’s advance would stall short of its final objective without fully isolating the battered Egyptian Second Army. The final ceasefire agreement would consequently find the 143d Armored Division, and its disappointed commander, at this position when the war ended.32 Having successfully enabled an extraordinary gap crossing in the face of fierce enemy resistance, Sharon and his troops had achieved an improbable feat and, against all odds, preserved the Jewish state.

Insights for the Twenty-First Century

The Israeli 143d Armored Division’s actions in the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, despite its costly mistakes, provide a useful example of a combined arms formation that successfully executed a high-risk water crossing in the face of antiair and antiarmor missile defenses to enable an ambitious counteroffensive. For the U.S. military today, as it orients on great power competition, the command’s achievement can inform how contemporary forces can, as required by its Joint doctrine, “gain a position of advantage in relation to the enemy” and “negate the impact of enemy obstacles.”33 Even as recent events in the Nagorno-Karabakh region and Ukraine have revealed challenges to large-scale maneuver, the IDF example in 1973 demonstrates how joint teams can nevertheless penetrate, disintegrate, and exploit a robust stand-off defense. Always a demanding task, this becomes especially acute when attacking forces are required to cross large rivers that are protected by arrayed fires that either contest or deny vital air and naval support.

Given this reality, and considering the U.S. Army’s principal role in facilitating gap crossings for Joint and coalition campaigns, its doctrinal tenets of operations that include agility, convergence, endurance, and depth can frame analysis of how Major General Sharon and his command achieved success. Beginning with the first tenet, agility, the 143d Armored Division proved dexterous and flexible as it recovered from early setbacks to seize initiative and execute a series of disparate tasks that included feints, bridge convoy escort, fixing attacks, sequenced crossings, and far-side raids against proximate SAM sites. While contemporary failures by the Russian Army in Ukraine have testified to the competence required for contested river crossings, Sharon’s forces, though far from perfect, repeatedly adjusted disposition and focus to enable their higher command’s scheme of maneuver.34 This became particularly important when the division had to negotiate unforeseen problems such as contested approaches to the Suez Canal, logistical issues along the access route, and the unexpected order to halt the ferrying of tanks to the far bank of the canal.

The second tenet, convergence, is defined as “the concerted employment of capabilities from multiple domains and echelons” to “create effects against a system, formation, decision maker, or in a specific geographic area.”35 The 143d Armored Division, and its 421st Armored Brigade in particular, personified this requirement on 16 October, when, even as conditions across the theater seemed to be unravelling, they employed their precarious lodgment on the far side of the canal to clear Egyptian SAM sites and begin the critical disintegration of the enemy air defense network. According to historian Abraham Rabinovich, this had the effect of creating “a small hole in the skies free of the threat” for Israeli attack aircraft to provide cover first for the emplacement of the mission-critical pontoon and roller bridges (despite high losses among Israeli engineers) and then the passage-of-lines by Major General Adan’s breakout forces.36 Further, the Suez Canal vignette offers an example, again contrasting with maneuver failures in the present Russo-Ukraine War, in which ground forces enabled services in other domains to combine efforts to achieve asymmetric advantages.

The tenet of endurance represents the third area in which the 143d Armored Division, despite facing replete challenges, managed to project combat power across a river barrier with enough durability to prevent culmination and enable the theater scheme of maneuver. While the distances of operation across the battle area remained modest, an intersecting array of problems that included congested routes, mechanical bridge failures, mired vehicles, faulty coordination, and initially limited air support conspired to threaten the ability of not only the division but also the entire IDF Southern Command to accomplish the risky counteroffensive. For Sharon, this became acute when his advance force operated for more than a day on the far side of the canal without resupply and thereby had to balance the urgent requirement to eliminate SAM sites and deflect Egyptian counterattacks with the reality of fuel and ammunition shortages.37 While the pontoon and roller bridges eventually created an assured line of communication for the transfer of supplies, the initial crossing required nuanced balancing of mission and risk to ensure continued operational endurance.

The final tenet, depth, pertains to the “extension of operations in time, space, or purpose” at the enemy’s expense.38 For the 143d Armored Division, this emerged as a central factor in the success of the IDF counteroffensive, as the canal crossing allowed Israeli forces to penetrate deep into the Egyptian rear area. While sequenced bridging efforts, though nearly stymied, allowed the IDF command to project durable combat power into Africa, the destruction of SAM sites, not only near the lodgment but also throughout the entire breakout area to the north and south, confounded Egyptian leadership and paralyzed the Second and Third Armies. These actions, all relying on the precarious bridges held by Sharon’s forces, catalyzed cycles of air-ground cooperation that allowed the IAF to conduct deeper strikes to more fully disintegrate the Arab defense. Again contrasting with more modern events in the Nagorno-Karabakh and Ukraine, in which attacking forces struggled to penetrate river barriers, the Israeli success against a larger and better equipped enemy reveals the premium value of employing calibrated joint approaches to extend operational reach.

Given these considerations, the lesson for the U.S. military is clear: the ability to execute contested gap crossings, as the Israeli 143d Armored Division did under desperate circumstances in 1973, remains a critical capability that must be developed to succeed in offensive campaigns. As seen in failed river crossings that debilitated or even stymied major offensives in past conflicts, this has become even more important given the increased lethality of the contemporary environment in which, as argued by U.S. Army general Donn A. Starry in the wake of the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, “anything seen on the battlefield can be hit, and anything that can be hit can be killed.”39 While it can be tempting to believe that previous exploits predict future success, it would be better for the U.S. military, and for the nation it serves, to remember the early failures of the IDF and the precarious traversing of the Suez Canal that saved the Jewish state from disaster. This means that the timeless requirement to negotiate rivers and obstacles, and to cross under fire to the other side, will remain essential for U.S. forces to effectively compete across the twenty-first century.

Endnotes

- Barriers, Obstacles, and Mine Warfare for Joint Operations, Joint Publication (JP) 3-15 (Washington, DC: Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2016), III-6.

- George W. Gawrych, The 1973 Arab-Israeli War: The Albatross of Decisive Victory, Leavenworth Papers no. 21 (Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, 1996), 60.

- Gen Jacob Even, IDF (Ret), and Col Simcha Maoz, IDF (Ret), At the Decisive Point in the Sinai: Generalship in the Yom Kippur War (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2017), x–xi, https://doi.org/10.5810/kentucky/9780813169552.001.0001. It should be noted that this work is written by subordinates of IDF MajGen Ariel Sharon and is therefore very favorable to the controversial general and the record of the 143d Armored Division.

- Operations, Field Manual 3-0 (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 2022), 3-2.

- Michael Howard and Robert Hunter, “Israel and the Arab World: The Crisis of 1967,” Adelphi Papers, no. 41 (October 1967): 39, https://doi.org/10.1080/05679326708448088.

- Gawrych, The 1973 Arab-Israeli War, 27–28, 40. For a participant’s description of why the Israeli Air Force suffered high losses in the first week of the war, see Col Eliezer Cohen, IDF (Ret), Israel’s Best Defense: The First Full Story of the Israeli Air Force (New York: Orion Books, 1993), 351–52.

- Even and Maoz, At the Decisive Point in the Sinai, 6–9. See appendix A of this work for a complete division task organization as represented after receiving greater combined arms reinforcements during the conflict.

- Martin van Creveld, The Sword and the Olive: A Critical History of the Israeli Defense Force (New York: Public Affairs, 1998), 241.

- Gawrych, The 1973 Arab-Israeli War, 43–52, 54–55.

- Uri Kaufman, Eighteen Days in October: The Yom Kippur War and How It Created the Modern Middle East (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2023), 203–4.

- Even and Maoz, At the Decisive Point in the Sinai, 78–79.

- Amiram Ezoz, “The Crossing Challenge: The Suez Canal Crossing by the Israel Defense Forces during the Yom Kippur War of 1973,” Journal of Military History 82, no. 2 (April 2018): 475.

- Gawrych, The 1973 Arab-Israeli War, 52.

- Joint Operations, JP 3-0 (Washington, DC: Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2017), III-38.

- Chaim Herzog, The War of Atonement, October 1973 (Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 1975), 263–69.

- Even and Maoz, At the Decisive Point in the Sinai, 97–98, 134, 259.

- Charles Moher, “Israeli General Tells How Bridgehead across the Suez Canal Was Established,” New York Times, 12 November 1973.

- Amiram Ezoz, Crossing Suez, 1973 (Tel Aviv: Content Now Books, 2016), 85–91, 97–98.

- Herzog, The War of Atonement, 210–17.

- Ezoz, Crossing Suez, 149–50.

- Gawrych, The 1973 Arab-Israeli War, 62.

- Ezoz, “The Crossing Challenge,” 479–80.

- SqnLdr Joseph S. Doyle, RAF, The Yom Kippur War and the Shaping of the United States Air Force, Drew Paper no. 31 (Maxwell Air Force Base, AL: Air University Press, 2019), 23–24.

- Abraham Rabinovich, The Yom Kippur War: The Epic Encounter that Transformed the Middle East (New York: Schocken Books, 2004), 389–90.

- Herzog, War of Atonement, 225–26.

- Kaufman, Eighteen Days in October, 277–79.

- Ezoz, Crossing Suez, 268–69, 281–85.

- Gawrych, The 1973 Arab-Israeli War, 56–57.

- Maj Clarence E. Olschner III, USAF, “The Air Superiority Battle in the Middle East, 1967–1973” (master’s thesis, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, 1978), 65–66.

- Herzog, War of Atonement, 242–44.

- Herzog, War of Atonement, 141–43.

- van Creveld, The Sword and the Olive, 235, 241.

- Barriers, Obstacles, and Mine Warfare for Joint Operations, xi.

- LtCol Amos C. Fox, USA, Reflections on Russia’s 2022 Invasion of Ukraine: Combined Arms Warfare, the Battalion Tactical Group and Wars in a Fishbowl, Land Warfare Paper no. 149 (Arlington, VA: Association of the United States Army, 2022).

- Operations, 3-3.

- Rabinovich, The Yom Kippur War, 390.

- Avraham Adan, On the Banks of the Suez: An Israeli General’s Personal Account of the Yom Kippur War (Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1980), 273–74. It should be noted that this is a memoir and contains potential author bias concerning controversial topics pertaining to the wartime record of IDF general Avraham Adan.

- Operations, 3-7.

- Donn A. Starry, “October 1973 Mideast War,” 12 May 1975, box 59, folder 3, Gen Donn A. Starry Papers, U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center, Carlisle Barracks, PA.