Robert S. Burrell, PhD; and John Collison

9 January 2024

https://doi.org/10.36304/ExpwMCUP.2024.01

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: This article details an applied methodology to operationalize an irregular approach to conflict and competition—in particular, external support to intrastate resilience or resistance. It introduces two foundational learning concepts: the resilience and resistance model and the resistance continuum. Using the resistance continuum, analysts can categorize the general nature of resistance movements across a spectrum from nonviolent protest through belligerency. Subsequently, this article offers several ways to identify and then assess resistance organizations. It then prescribes methods to make recommendations concerning potential external support in another state’s intrastate conflict consisting of three primary options: to support current governance, to support opposition to governance or occupation, or to do nothing. Finally, it provides practical application with a real-world case study—China and Taiwan—which demonstrates the utility of this methodology in understanding intrastate conflict and the possibilities offered to external sponsors of change.

Keywords: resilience, resistance, irregular warfare, competition, deterrence

Introduction

In the twenty-first century, irregular conflicts have caused the United States a great deal of angst.1 As recently demonstrated in the October 2023 Hamas attack on Israel and Israel’s response, irregular threats continue to prevail globally.2 Fortuitously, the U.S. Congress in 2021 demanded that the U.S. Department of Defense develop education to prepare for future irregular struggles.3 In response, to address the academic gap in preparing for irregular forms of conflict, the Small Wars and Insurgencies journal published an article entitled “A Guide for Measuring Resiliency and Resistance,” which analyzes nation states in more advanced human-centric terms to assess current levels of governmental and societal resiliency to subversion and coercion, as well as internal and/or external aggression.4

Measuring state resiliency and potential for resistance comprises only phase one of a comprehensive approach to addressing irregular threats. Phase two includes identification of resistance movements and categorizing their nature according to their typology on the resistance continuum. Phase three describes resistance movements in terms of leadership, cause, environment, organization, and actions. Finally, phase four examines potential external support options to partners in intrastate conflict. This article provides a compendium to the state-centric resilience and resistance analysis model that was articulated in the Small Wars and Insurgencies article (i.e., phase one). As an extension, it introduces methodologies to facilitate deeper understanding of resistance movements themselves (i.e., phases two and three). This improved methodology provides a more informed approach to assist decision and policy makers in considering irregular approaches to competition, deterrence, and war (i.e., phase four).5 Throughout the proposed methodology, interdisciplinary methods remain vital, as military science cannot alone prepare practitioners for future conflict.

Every human society contains forms of resistance to current governance or foreign occupation. Resistance can span a spectrum of activities, from nonviolent and legal forms to illegal or violent means. In contrast, each regime attempts to brace the resolve of the population against internal political, economic, or social change, and even revolution. This article explains how resistance movements and recognized authorities conceptually interact with one another, with their shared population, and among international benefactors. While external sponsors can choose to support resiliency or resistance in other societies, identifying the nature of resistance movements remains critical to ascertaining the most appropriate and effective support. Using the resistance continuum, analysts can categorize the general nature of resistance movements across a spectrum, from nonviolent protest through belligerency. Subsequently, this research offers several ways to identify and assess resistance organizations. It also prescribes methods to make recommendations concerning potential external support in another’s intrastate conflict. External sponsors can make a deliberate choice to help stabilize another nation’s governance through support to resilience; aid aggrieved populations against other state through support to resistance; or not directly interfere in the sovereignty of another state. Finally, this article includes a practical application of the methodologies with a real-world case study involving China and Taiwan.

The Resilience and Resistance Model

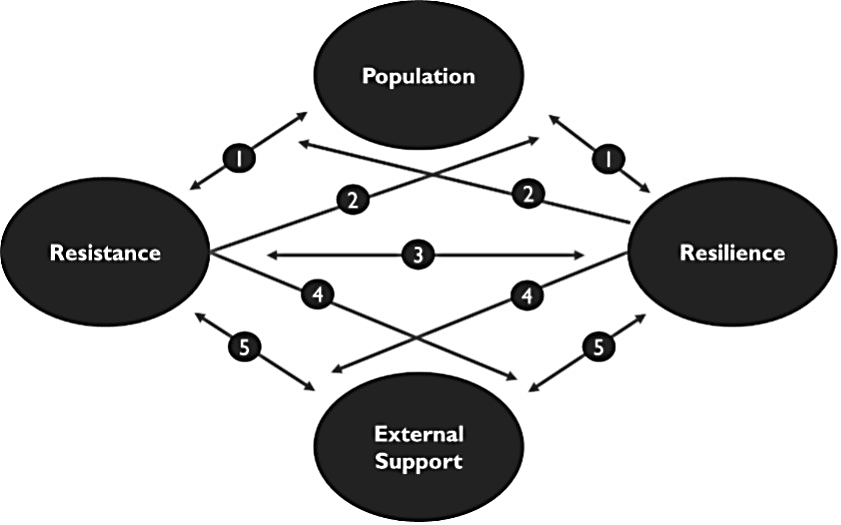

As introduced in “A Guide for Measuring Resiliency and Resistance,” an important framework to consider is the resilience and resistance model, which is based on Gordon McCormick’s model for insurgency.6 This model was modified so that it includes the full spectrum of the resistance continuum, from peaceful demonstration to belligerency. The resilience node represents recognized governance and authority, and the resistance node represents opposition to existing governance or occupation. The resistance and resilience elements are directly confronting each other while simultaneously struggling to garner both domestic and international support. Concurrently, they each attempt to counter the efforts of the other.

Figure 1. Diagram of the resilience and resistance model

Source: courtesy of the authors, adapted by MCUP.

In this model, there are four primary nodes: the population node, the resilience node, the resistance node, and the external support node. The resistance and resilience nodes perform five basic actions in opposition to each other: they attempt to gain support from the population, disrupt the other’s efforts to garner support from the population, perform violent and/or nonviolent actions directly against one another, attempt to interrupt their opponent’s attempts to garner international support, and attempt to garner international support. Both the population and external support nodes have agency and can initiate actions to influence the resilience and/or resilience nodes as well (hence the dual arrows on lines 1 and 5). The power of the resilience and resistance model is that it applies in nearly every intrastate conflict, no matter the scale or level of violence.

External Support to Resilience or Resistance

An external partner has three options in regard to another nation’s internal conflict: to support a regime’s resilience in order to free and protect its society from such threats as subversion, lawlessness, and insurgency; to support indigenous resistance against an adversary’s governance to coerce, disrupt, or overthrow the regime; or to choose to do nothing. In the first two cases, the external sponsor can employ a combination of several methods to support a partner or surrogate. In terms of military aspects, support to resilience normally includes activities such as foreign internal defense, counterinsurgency, and stabilization actions. The means might include arms, equipment, and training. In contrast, the military way to support resistance is typically referred to as unconventional warfare or special warfare, depending on the national doctrinal variances. The military way of supporting resistance includes covert and/or overt military assistance to enhance the subversion of the opposing state. Nonetheless, military ways and means comprise only one approach to support a partner.

For simplicity, this discussion is narrowed to four types of support relating to the major instruments of national power: diplomatic, informational, military, and economic (DIME).7 In each situation, the DIME “cocktail” provided by an external sponsor will likely have ingredients of varying sizes based on desired outcomes. As legitimacy can be a deciding factor in achieving victory for either a resistance movement or current regime, diplomatic support from a recognized sovereign partner can prove quite valuable. As a population-centric struggle, the battle for narrative and information activities can also prove important. Economic support can assist in stabilizing a partner and enhancing their legitimacy, including facets of food, medical care, and/or employment opportunities.

There are several factors to consider when evaluating resistance movements in a particular region, including religion, demographics, ethnicities, and social hierarchies. However, understanding the distinct categories of resistance can help determine what types of military support—if any—are appropriate for external support to any resilience partner or resistance movement.

The Resistance Continuum

Within the resilience and resistance model, particular care should be taken in assessing the resistance node. Human populations inherently develop opposition to indigenous governance or foreign occupation. Simultaneously, each regime has supporters who wish to steel the resolve of the population from reform. Although resistance is a commonality around the globe, resistance movements themselves are quite distinct. The purpose of a movement might rely on factors of social injustice, ethnic tensions, or ideologic or religious differences. Consequently, resistance movements develop unique approaches to motivate regime change. Essentially, no resistance movement is the same.

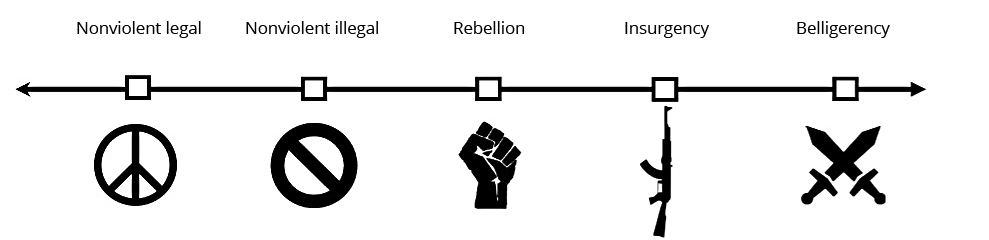

Nevertheless, resistance generally occurs along a continuum (figure 2). This continuum indicates a scale of protest and conflict, though resistance movements often employ more than one of these methods over time.

Figure 2. Diagram of the resistance continuum

Source: courtesy of the authors, adapted by MCUP.

Resistance can comprise nonviolent protest that is conducted legally or at least within established international norms. In fact, the United Nations recognizes lawful assembly and protest as a universal human right.8 One notable example of this is the civil rights movement in the United States during the 1950 and 1960s to protest Jim Crow laws and achieve voting equality for African Americans.9 Another form of protest is nonviolent but remains inherently illegal. Those who supported the antebellum Underground Railroad network that helped enslaved African Americans escape into the Northern United States and Canada in the early to mid-nineteenth century fall into this category because the Underground Railroad directly opposed congressional law pertaining to the rights of American slave owners.10

When protest turns violent, it becomes rebellion. Small outbreaks of violence, such as Nat Turner’s revolt against slave owners in Virginia in 1831, exemplifies rebellion.11 This category is generally defined by the scale of violence, meaning that in most cases the government can attempt to counter the violence with available means such as law enforcement. In contrast, insurgency is also violent, but the government can no longer address the resistance through rule of law. During the period called “Bleeding Kansas” (1854–61), pro-slave and free-state communities in the United States employed coercion and violence against one another with the objective of controlling voting outcomes and securing their disparate visions of statehood.12 In belligerency, the resistance demonstrates such autonomy that it resembles its own nation state. Typically, belligerency results in a bloody civil war, with the resistance and the regime fighting through conventional military tactics for the ultimate stakes of controlling the future state.

These terms—nonviolent legal, nonviolent illegal, rebellion, insurgency, and belligerency—were introduced by Erin N. Hahn and W. Sam Lauber, both lawyers working at John Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory.13 Hahn and Lauber attempted to create legal categories for participants in, and external actors supporting, resistance activities. From the perspective of external support to intrastate conflict, these legal categories consist of an important advancement for discussion. However, these five categories do not neatly fit within the taxonomies of social movements, law, or military science. They do, however, offer a construct from which all three disciplines can perhaps combine into a cohesive understanding and a subsequently useful application for constructing military strategy or foreign policy. To further understand and operationalize the resistance continuum, a brief example of all five categories follows.

Nonviolent Legal

Nonviolent legal and nonviolent illegal forms of protest are often lumped together and treated the same. As one example, in 1973 American political scientist Gene Sharp created 198 ways to perform nonviolent action without any distinction to legality.14 However, mixing these two methodologies, one legal and other illegal, ultimately makes the entire resistance organization an illicit one and subject to arrest and prosecution. Legal forms of protest have unique advantages in moral and ethical supremacy. Careful consideration should be followed before negating this benefit.

A quintessential example of nonviolent legal resistance comes from Mahatma Gandhi and his protest methods used in South Africa and India. A religious guru, Gandhi rose in the political ranks and eventually became a national symbol of resistance to foreign influence, particularly that of the United Kingdom. One of his most frequent means of protest included hunger strikes, but perhaps the most iconic was his Salt March in 1930. Brilliantly, Gandhi meant to protest the British monopoly on salt. At the time, the United Kingdom placed taxes on salt, which all Indians of every social class paid. To make this monopoly lucrative, the British outlawed the making of salt by Indians. While other Indian nationalists found Gandhi’s protest idea ridiculous, opposing the exploitation of salt quickly grew into a symbolic demonstration with shared national interest across all of India’s diverse populations.15

Nonviolent Illegal

A premier example of nonviolent illegal resistance comes from Nelson Mandela and his campaign against racial segregation. The White South African government had instituted a system of exclusion of Blacks and other non-Whites from representative government and equal opportunities, a system called apartheid. Through the African National Congress, Mandela employed several methods to resist authority, primarily through nonviolent legal methods characterized by Gandhi and American civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. However, in 1961, the Umkhonto we Sizwe paramilitary group, headed by Mandela, began planning acts of sabotage in South Africa. These specifically targeted infrastructure to avoid loss of life.16

This category of nonviolent illegal probably best serves as also embracing social movement terms such as nonviolent insurrection and warfare terminology such as subversion and sabotage. Nonviolent insurrection (or unarmed insurrection) refers to a general uprising against a regime or occupying power, but largely without the use of violent means. This is best described by Stephen Zunes as activities such as “strikes, boycotts, mass demonstrations, the popular contestation of public space, tax refusal, destruction of symbols of government authority (such as official identification cards), refusal to obey official orders (such as curfew restrictions), and the creation of alternative institutions for political legitimacy and social organization.”17 One recent example of nonviolent insurrection is the Orange Revolution in Ukraine in 2003–4. The protests were massive, including a large segment of the Ukrainian population. While these demonstrations remained nonviolent, protestors brought the capital city of Kyiv to a halt, effectively—and unlawfully—shutting down the government.18 Another example of nonviolent illegal includes the Umbrella Movement, which sought change to Chinese policies in Hong Kong in 2014, an interesting case study that stands apart in terms of innovation by leveraging technology and social media in modern resistance.19

Rebellion

On the resistance continuum, rebellion clearly indicates a marked change in methodology that includes lethality. However, any movement embracing the use of violence might also include the nonviolent forms of protest discussed previously. The distinction regarding rebellion is that the resistance either deliberately employs lethality or lethality evolves from what was originally intended as a nonviolent form of protest. Violence can result as a choice made to evade capture or to protect oneself or others from the reprisal of authority. Violence may also comprise a deliberate method planned for and used to achieve desired ends.

The key constraint in rebellion remains the extent of the violence and how it is addressed by authority. Hahn and Lauber explain rebellion as violence that a “state’s law enforcement mechanisms are able to suppress”—in other words, military force is not mobilized to suppress it.20 This creates an excellent threshold for consideration. Consequently, lethality remains limited, either by choice, in the case of a large demonstration preferring other nonviolent methods, or simply by the limited size of the participants, even if lethality remains the primary tool.

In rebellious organizations of limited size, the movement can form an armed component that is dedicated to the use of violence as its primary means of resistance. Employing a small armed force against a large state apparatus rarely achieves dramatic success if done directly. For instance, in 1831, Virginia state authorities found and executed slave rebellion leader Nat Turner and his followers in just six weeks.21 Often, enduring organizations attempt asymmetric methods familiar to military science, such as raids, ambushes, and assassination. The state, in turn, may label a violent movement a terrorist organization, after which the state can justifiably use its military to destroy it. As a result, terrorism must be included in the same category as insurgency, as will be discussed later.

Large-scale social revolts without a major armed component have become more prevalent in the twenty-first century.22 Beginning in late 2010, the Arab Spring encompassed revolutions in more than a dozen countries in the Arab world. In each case, the resistance fell into various categories, to include nonviolent illegal, insurgency, and belligerency. However, the resistance in Egypt most likely fits the case of rebellion because deaths were fewer than 1,000 and the military did not directly intervene. In fact, when security forces could not contain the crowds, the Egyptian military refused orders to put down the protests and actually interjected forces only to save the resistance from harm.23 Consequently, the Arab Spring in Egypt fits the category of a rebellion, where violence did occur but on a limited scale despite very large numbers of protestors. Another similar example of a large resistance movement using limited violence is the Maidan Revolution in Ukraine in 2014. During four months of conflict, the numbers killed remained minor in comparison to the number of protestors and security forces participating, and no military response was used to put down the rebellion.24 Rebellion includes methods that intentionally or unintentionally cause fatalities as a result of resistance activities. For instance, the unintended result of a protest could be its development into a destructive riot.

Insurgency

The barrier between rebellion and insurgency is the use of a nation’s military to address the resistance. Once a military commences operations against a resistance movement, the threshold has been crossed from rebellion to insurgency. The classification of insurgency has a long history in military science. What needs further reconciliation, however, is that terrorism can also comprise a resistance organization being addressed with military force.

In terms of legal status, insurgent groups do not clearly differentiate from terrorist organizations in terms of the law. Both can be argued as using illegal lethal means against the state, either against the nation’s military or against its citizens. Ethically, there are distinct differences in these two methodologies, as one method can avoid killing noncombatants and the other can completely dehumanize the use of violence.25

The bifurcated approach and resulting confusion between terrorism and insurgency has an extended historiography, and no consensus exists on the topic within any discipline. Lawyer Ranbir Singh argues that “there is a very thin line of distinction between ‘terrorism,’ ‘insurgency’ and ‘belligerency’; and in almost all cases these are terms donating the various stages of the same process.”26 This blur between terrorism and insurgency is also illustrated in the case of the Algerian Front de Libération Nationale (National Liberation Front), which fought against the French in Algeria in 1954–62.27 Additionally, the Provisional Irish Republican Army, which fought to end British rule in Northern Ireland from 1969 to 2005, also offers a good example of a movement comprising both an insurgent group and a terrorist organization.28 The proposed methodology considers that insurgency and terrorism both use illegal forms of lethal violence against a state and/or its citizens to attain political goals or regime change and creates a threat to the government’s sovereignty that is considered grievous enough to require the government to address it with military force.

Belligerency

In belligerency, a resistance organization emerges to make conventional war against a state. Sometimes, belligerency occurs when a successful insurgency evolves to maintain state-like functions in a region and sustains human security responsibilities over a segment of the population. Unfortunately, belligerency as a resistance category does not have international agreement, primarily because sovereign nation states do not want to recognize lethal forms of resistance as anything but illegal.

Nevertheless, belligerency, or civil war, has a long history of resistance developing into a sovereign power. The formulation of the United States is case in point, as the American Revolution gained legitimacy after recognition from France in 1778. Because the current global order only recognizes the legitimacy of sovereign states, despite the fact that belligerency can and has opposed such states, it is extremely difficult for revolutions to gain belligerent status. Simultaneously, foreign powers have conducted “military interventions in civil wars despite constituting the de jure interference in another state’s internal affairs.”29

A classic example of belligerency is the American Civil War, during which the Confederate States of America met most of the preceding conditions. Try as it might, the Confederacy could not receive its desired recognition by Great Britain.30 However, both Great Britain and France gave the Confederacy belligerent status to enable the contract and sale of weapons and goods. In a modern context, violent resistance stemming from an insurgency must receive official recognition by an existing nation state to be considered a belligerent. In such cases, it is best to receive recognition from as many states as possible, or even from an international or regional body.

Identifying Resistance Movements

This article outlines methods to leverage current scholarship and research carried out by some of the top universities and nonprofit organizations that study resistance to help practitioners identify existing resistance movements and trends of success or failure within nation states. The organizations acknowledged herein include Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania; Harvard University; the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington, DC; the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project, a nonprofit organization; and Uppsala University in Sweden. The data generated by these organizations remains publicly available on the internet.

Once an analyst identifies resistance movements, the general nature of each can be categorized along this typology as nonviolent legal, nonviolent illegal, rebellion, insurgency, or belligerency. Fortunately, there are many ways to identify resistance movements in any country or region. As a starting point, several recommended sources are offered below.

A quick search of a nation state in the Global Nonviolent Action Database, originally created by researchers at Swarthmore College, can provide excellent results on the activities of nonviolent organizations that are regularly updated.31

Similarly, Harvard University maintains a database called the Nonviolent and Violent Campaigns and Outcomes (NAVCO) Data Project, though this data currently appears generally limited from 1900 to 2013. Compiled by dozens of separate researchers, the project contains several datasets that show durations of conflicts, the number of participants, the relative percentage of participants to the population, and the success or failure rates.32

Harvard also maintains a website called Mass Mobilization Protest Data. This downloadable dataset illustrates protests internationally with dates, numbers of people mobilized, and the purposes for the protest. However, the dataset does not directly identify the organizations participating, though these could be quickly surmised with a subsequent search about the event on the internet.33

The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace maintains a Global Protest Tracker with locations, dates, size, and durations of mass protests around the world. This data requires no downloads and is entirely web-based. It expands in more detail about particular events, providing information on such factors as triggers, motivations, key participants, and outcomes.34

The nonprofit Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project offers data on violence in every country in terms of battles, riots, explosions, and violence against civilians. More detailed information requires downloading the available datasets.35

Finally, the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP) illustrates organized violence around the world, particularly intrastate conflict. It contains an interactive map, which allows a researcher to click on a state and retrieve a summary of a conflict, its history, and the number of deaths. At least 25 battlefield-related deaths taking place between a recognized government and an armed group are required for categorization. This website is continually updated by Uppsala University’s Department of Conflict and Peace Research.36

These recommended websites are not all-inclusive for identifying resistance movements within a state or region, but they provide a good start for research.37 Once identified, a student, scholar, or practitioner can bin these movements along the resistance continuum, using the descriptions prescribed previously, as a means of categorizing the general nature of activities preferred by each organization.

Assessing Resistance Movements

After identifying resistance movements along the resistance continuum, an assessment can summarize the potential of each one. Several studies and theories attempt to define ways of deconstructing and assessing political movements, insurgencies, or resistance organizations in general.38 This article incorporates the typology of resistance introduced by Jonathon B. Cosgrove and Erin N. Hahn in the U.S. Army Special Operations Command study Conceptual Typology of Resistance.39 Essentially, in assessing a resistance movement, this article recommends further operationalizing the research of Cosgrove and Hahn. Cosgrove and Hahn argue that a resistance has five attributes: actors, causes, environment, organization, and actions. Cosgrove and Hahn define these characteristics in the following terms.

-

Actors: the individual and potential participants in an organized resistance, as well as external contributors and either competing or cooperating resistance groups.

-

Causes: the collectively expressed rationales for resistance and the individual motivations for participation.

-

Environment: the preexisting and emerging conditions within the political, social, physical, or interpersonal contexts that enable or constrain the mobilization of resistance, directly or indirectly.

-

Organization: the “internal characteristics of a movement: its membership, policies, structures, and culture.”40

-

Actions: the means by which actors carry out resistance as they engage in behaviors and activities in opposition to a resisted structure; [this] can encompass both the specific tactics used by a resistance movement and the broader characteristics or repertoires for action (i.e., strategy).41

Actors

The actor category consists of leaders, participants, the population, other resistance movements, and external support.42 Leaders can be categorized as either agitators, prophets, reformers, statesmen, or administrators. Each can be evaluated as to their potential in comparison with others of their type. For instance, Martin Luther King Jr. might be considered a nearly perfect architype of a reformer in this sense. Participants are either full-time members, such as those in the armed component or underground, or part-time supporters, such as those in the auxiliary. The population can be evaluated generally as having one of three tendencies: those who support the government, those who support change through resistance, and those who prefer to remain uncommitted. The U.S. Army War College’s Study of Internal Conflict has demonstrated that support from 15 percent or more of the population can prove decisive.43 Other resistance movements that share desired change and can collaborate with one another can have more potential than when evaluated separately. External support, either material or nonmaterial, can prove extremely important for a successful resistance. As described previously, external supporters can consist of multiple organizations, not simply governments. Table 1 outlines the basic tenets for actor analysis.

Table 1. Assessing potential of resistance actors

|

Actors

|

Components

|

Qualifiers

|

|

The individual and potential participants in an organized resistance, as well as external contributors and either competing or cooperating resistance groups.

|

Type of leader

|

Agitator, prophet, reformer, statesman, or administrator

|

|

|

Categorize the type of leader or leaders who hold sway over this movement. Assess their potential by comparing them with historical examples of the same. Are they recognized nationally or internationally?

|

|

Participants

|

Full time members and part-time supporters

|

|

|

Evaluate the loyalty, enthusiasm, and popularity of the cadre in the inner circle as well as other supporters with the organization. What is the potential that their commitment might exponential effects on the outcomes of the movement?

|

|

Population

|

Who supports the government? Who support change through resistance? Who prefer to remain uncommitted?

|

|

|

What percentage of the population actively or passively supports resistance? Remember, 15 percent or more support of resistance by the population could prove decisive.

|

|

Other resistance organizations

|

The sum of resistance organizations can add up to a more powerful and united whole.

|

|

|

Are there any other resistance movements that, when organized together, could more effectively contribute to a shared desired change? Conversely, are there other movements with incompatible goals? If so, assess the advantages or disadvantages that this support could have on resistance efforts.

|

|

External support

|

Which types of organizations outside the geographic boundaries of the country support this resistance movement?

|

|

|

Assess the totality of external support organizations who favor the resistance and could provide substantial material or nonmaterial support. Could this support prove decisive?

|

Source: courtesy of the authors, adapted by MCUP.

Causes

Resistance supports a cause that represents the collectively expressed rationales for opposition to authority, as well as the individual motivations for participating in such a group. The rationale for resistance consists of either a desire for sweeping change in authority or society or specified changes for individual groups or communities.44 A scholar or practitioner should identify the stated public narrative of an organization that normally delegitimizes the current authority and legitimizes its own claims.

The second key component to analyzing the cause includes the motivations of the participants. A group of scholars at the Artis International research institution, particularly Scott Atran, have conducted several studies on the differences between “devoted actors” and those motivated by self-interest during conflict. A cause that fuses participants’ culture-defining values, spiritual formidability, and trust in the group and/or leader can inspire actors to endure long periods of discomfort and well as personal sacrifice.45 Consequently, the rationale of particular causes can inspire a greater will to fight. Table 2 outlines the basic tenets for causation analysis.

Table 2. Assessing the cause of resistance

|

Causes

|

Components

|

Qualifiers

|

|

The collectively expressed rationales for resistance and the individual motivations for participation.

|

Rationale

|

The rationale for resistance consists of either a desire for sweeping change in authority or society or specified changes for individual groups or communities.

|

|

|

Identify and restate the prevailing rationale of the resistance, including ends, ways, and means used to attain success. Use this rationale when analyzing its power of motivating the core values of a population below.

|

|

Motivations

|

What motivations are used by the resistance to recruit and maintain its supporters through sacrifice and difficulty?

|

|

|

Does the stated rationale of the movement identify with sacred values in the population? If so, what percentage of the population identifies with those values? Remember, 15 percent or more could prove decisive.

|

Source: courtesy of the authors, adapted by MCUP.

Environment

One analogy that highlights the environment’s relationships with resilience and resistance is that the environment represents the chessboard on which the king, rook, bishop, queen, knight, and pawn compete. Assessing the environment’s influence or constraints on both resilience and resistance activities requires an interdisciplinary approach but should include at a minimum an evaluation of environmental, governmental, sociopolitical, technological, and relationship factors.

The environment consists of geographic limitations such as maritime boundaries, mountainous terrain, urban terrain, and space and cyberspace. One could describe the environment in terms of domains—land, maritime, air, space, and the information environment—such as those articulated in military doctrine.46 Governance represents the current rule of law, or lack thereof, as a system of control of the nation state. For instance, in Western nations, the accepted rule of law can facilitate nonviolent action, wherein opposition to an authoritarian regime may require more secrecy or violence to implement. There are five prevalent forms of government: monarchy, democracy, oligarchy, authoritarianism, and totalitarianism.47

In addition to governance, every society has socioeconomic factors that determine accepted norms. Challenging these norms or accepting them will affect the ways in which resistance activities take place. Further, a society’s access to technology provides various means to communicate with or influence these norms, and also provides platforms for nonviolent or violent action.48 As one example, communicating with a resistance group in North Korea may require primarily face-to-face interaction, whereas Joshua Wong’s resistance in Hong Kong relied on web-based platforms.49 Finally, resistance takes place in human terrain, in addition to the domains listed previously, and “preexisting and emerging relationships among individuals, organizations,” and social groups have proven fundamental to how resiliency and resistance interact with one another.50 Table 3 outlines the basic tenets for environmental analysis.

Table 3. Environment in which resistance takes place

|

Environment

|

Components

|

Qualifiers

|

|

The preexisting and emerging conditions within political, social, physical, or interpersonal contexts that enable or constrain the mobilization of resistance, directly or indirectly.

|

Domains

|

Land, maritime, air, and space domains and the information environment

|

|

|

Explain how the land, maritime, air, and space domains, as well as the information environment, provide opportunities or constraints for this particular movement.

|

|

Governance

|

What type of governance exists in the state?

|

|

|

Assess the rule of law in the state as best catagorized as a monarchy, a democracy, an oligarchy, authoritarianism, or totalitarianism. What are the secondary effects of that governance structure on resistance?

|

|

Sociopolitical aspects

|

Full time members and part-time supporters

|

|

|

Evaluate the loyalty, enthusiasm, and popularity of the cadre in the inner circle as well as other casual supporters within the organization. What is the potential of their commitment that could effect the outcomes of the movement?

|

|

Technology

|

Technological capabilities of the society

|

|

|

Describe the communication platforms dominant in the society as well as access to smartphones and the internet. Will any platforms enable clandestine means of communication? What is the capacity of authorities to monitor and detect resistance? What commercial off-the-shelf platforms might support resistance activities (e.g., radios, medical supplies, or UAVs)?

|

|

Relationships

|

Preexisting or emerging relationships

|

|

|

Describe any ongoing relationships between members of the resistance or the organization itself with other influencers inside the state or internationally. What potential could these relationships have on the success of the movement?

|

Source: courtesy of the authors, adapted by MCUP.

Organization

One study completed by John Hopkins University generally categorizes resistance organizations into two bins: mass organization and elite organizations. Each has advantages and disadvantages. Mass organizations have few bars to entry for recruiting, taking advantage of size to compete with authority. These can be excellent archetypes for forms of nonviolent protest, such as social movements or unions, or as a belligerent organization in a civil war. However, mass organizations are difficult to train and control, are easier for authorities to infiltrate, and contain members who can prove undisciplined. In contrast, elite organizations take advantage of extensive vetting, selective recruiting, superior training, and a high degree of motivation. These types of movements are normally secretive, operating with undergrounds or, when overt, maintaining covert or clandestine activities. An elite organization can influence mass organizations and even hijack or control their behaviors. Elite organizations designed to blossom into a mass organization given the right circumstances are called elite-fronts; these include traditional communist parties.51

Resistance movements can be suborganized in a myriad of ways. In most military doctrines, these can include an underground, an armed component, an auxiliary, and a public component.52 However, nonviolent resistance organizations might forego the need for an underground and an armed component, opting for an overt organization without violent means. Consequently, resistance movements may contain all or some of the four components listed. Each component can be described in terms of who comprises its membership, what types of policies guide the members, the structure of each component (e.g., a cellular or hierarchal organization), and the prevailing culture, values, and motivations guiding each. Table 4 outlines the basic tenets for organizational analysis.

Table 4. Organizational structure of resistance

|

Organization

|

Components

|

Qualifiers

|

|

The internal characteristics of a movement; its membership, policies, structures, and culture.

|

Org.anization type

|

Mass organization or elite organization

|

|

|

Does this organization require large numbers to oppose authority, or does it require secrecy to maintain a small elite group? Describe how and why the organization operates and the advantages and disadvantages of that choice.

|

|

Resistance components

|

Underground, armed component, auxiliary, and public component

|

|

|

How many of the above components does this resistance movement have? Describe each of the above components in terms of membership, policies, structures, and culture.

|

Source: courtesy of the authors, adapted by MCUP.

Actions

Much of the discussion of ways, or actions, of varying types of resistance movements has been discussed previously in this article. These ways help define movement along the resistance continuum. The methods of action typical to a particular resistance should be restated in the formal assessment (i.e., nonviolent protest, assassination, etc.). Additionally, methods of fundraising and equipping should be analyzed. Procurement can consist of the legal market, the black market, battlefield recovery, theft, taxes (or fundraising), manufacturing raids, and external partners outside of the state.53 One should determine if the movement uses self-procurement for most needs, or if it relies primarily on external sponsorship. Table 5 outlines the basic tenets for actions or ways analysis.

Table 5. Actions carried out by resistance

|

Actions

|

Components

|

Qualifiers

|

|

The means by which actors carry out resistance as they engage in behaviors and activities in opposition to a resisted structure. This can encompass both the specific tactics used by a resistance movement and the broader characteristics or repertoires for action (i.e., strategy).

|

Ways of resistance

|

The resistance continuum consists of nonviolent legal, nonviolent illegal, rebellion, insurgency, and belligerency.

|

|

|

Qualify the ways used for resistance in terms of nonviolent protest, illegal protest, rebellious lethal activities, insurgency, or belligerency. Provide examples.

|

|

Funding and procurement

|

Which methods does the resistance use to sustain its activities?

|

|

|

Of these methods, which are use by the resistance: legal market, black market, battlefield recovery, theft, taxes (or fundraising), manufacturing raids, and external partners?

|

Source: courtesy of the authors, adapted by MCUP.

In summation, this article recommends assessing resistance organization with the typology of five central components: actors, causes, environment, organization, and actions.54 An assessment of a resistance might be as short as five paragraphs, each one devoted to one of these subcomponents. As a given, such an assessment proves subjective. Quantifying aspects of this approach remains under further research and analysis.

Providing a Comprehensive Examination

The first three phases in a comprehensive analysis include the following: measuring the resiliency and resistance potential at the state level (as published previously in Small Wars and Insurgencies), identifying prevalent or influential resistance organizations within the state using the methods prescribed and categorizing them along the resistance continuum to classify their general nature; and assessing one or more of those resistance movements by taking a deeper look at their actors, causes, environment, organization, and actions (using the acronym ACEOA).55 The final phase includes subjectively assessing the information gathered to make recommendations concerning potential external support in another state’s intrastate conflict consisting of three primary options: to support a governing authority’s resilience, to support resistance to current governance or occupation, or to do nothing. At a minimum, the comprehensive analysis consists of the 12 steps shown in table 6.

Table 6. The 12-step resilience and resistance analysis process

|

Phase

|

Steps

|

|

One

|

1. Measure the state’s resiliency.

|

|

2. Identify the potential for a state-sponsored resistance strategy.

|

|

3. Measure the potential for external support to resiliency.

|

|

4. Measure the potential for resistance to current authority.

|

|

5. Measure the potential for external support to resistance.

|

|

Two

|

6. Identify the prevalent resistance groups within the state and place them on the resistance continuum.

|

|

Three

|

7. Assess one or more resistance groups in terms of leadership.

|

|

8. Assess one or more resistance groups in terms of cause.

|

|

9. Assess one or more resistance groups in terms of environment.

|

|

10. Assess one or more resistance groups in terms of organization.

|

|

11. Assess one or more resistance groups in terms of actions.

|

|

Four

|

12. Make a recommendation concerning potential external support to resiliency or resistance, which normally proposes one of three options: to support resiliency of current governance, to support resistance to it, or to do nothing.

|

Source: courtesy of the authors, adapted by MCUP.

Practical Application

For the sake of saving space, this article will forgo phase one (the RSSRS acronym and the methodology published previously in the Small Wars and Insurgencies journal, which frames the state’s operational environment in terms of resiliency and resistance).56 That means skipping steps 1–5 seen in table 6. It is, however, recommended to complete phase one prior to completing steps 6–12. This case study examines the People’s Republic of China, as it illustrates a substantial number of strong resistance organizations along the resistance continuum.

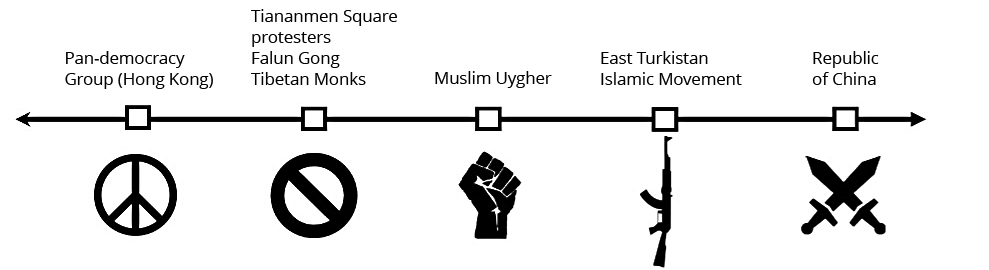

Phase Two: Identifying China’s Resistance Movements

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) retains various powerful state means of control for curtailing protest and nonviolent action. Still, according to Harvard’s Mass Mobilization Protest Data information, 6 million people mobilized to protest in China between 1990 and 2020. While some groups mobilized in the hundreds, 18 events occurred with hundreds of thousands of people. Most of these large protests occurred in Hong Kong, with an estimated 5.4 million people mobilized between 1997 and 2020.57 Of the multiple organizations, the pan-democracy camp, made up of multiple political parties in Hong Kong, represents the most influential group. The CCP has charged the young and popular Hong Kong activist Joshua Wong, leader of the student activist group Scholarism, multiple times for subversion, and he has served time in prison. The political party formed by Wong in 2016, Demosisto, was disbanded in 2020. Another important nonviolent action party in China consists of Tibetan monks, who have maintained various forms of protest against the CCP since the Chinese People’s Liberation Army occupied Tibet in 1950.58 The spiritual ruler of Tibet, the Dalai Lama Tenzin Gyatso, maintains essentially a government in exile in Dharamsala, India. Since 2009, 131 Tibetan men and 28 Tibetan women have conducted public self-immolation as an act of protest to the CCP’s infringement on civil rights, particularly religious freedom. Another religious group under CCP repression, and thereby illegal, is Falun Gong. In 1999–2000, at least 14,000 members of Falun Gong protested in 10 marches to oppose the CCP’s policies, primarily in the capital of Beijing.59 Finally, labor protests and strikes remain frequent in China but are generally sporadic, grassroots, and unorganized.

Nonviolent protests under the CCP’s authoritarian regime have not gone well so far. Harvard’s NAVCO project lists three major protest campaigns since 1989: the Tiananmen Square protests in Beijing in 1989, the Kirti Monastery protests in Tibet in 2012, and the prodemocracy protests (or Umbrella Movement) in Hong Kong in 2014–19.60 NAVCO evaluated all of these as failures. After review, identifiable nonviolent legal protest groups in China include the pan-democracy camp, while nonviolent illegal protest groups include an active underground and public component of remaining members of the Tiananmen Square protests, an active underground (possibly in the millions) and public component of Falun Gong, and both an underground and public component of Tibetan Buddhist monks.61

In western China, conflict with Islamic groups abounds, particularly in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. According to Uppsala University’s UCDP, the Eastern Turkistan Islamic Movement (ETIM) is aligned with both al-Qaeda and the Islamic State and has established base camps in Afghanistan and Syria during the past two decades. ETIM violence in Xinjiang is associated with 65 deaths since 1990. The Muslim majority of the Uyghur population in Xinjiang remains opposed to the CCP’s Sinicization policies and Han immigration. UCDP categorizes their activities as “organized violence,” with more than 25 battle-related deaths in 2009.62 Of the 11 million Uyghurs in Xinjiang, the CCP has imprisoned 1 million “in reeducation camps” since 2017.63 The most recent significant protest in 2023 includes more than 1,000 Muslims in China’s Yunnan Province protesting Communist dictates on Islam, but this did not include violence.64 One could surmise that the CCP has committed to programs that equate to cultural genocide against Islam in Xinjiang. In terms of violent resistance, one could categorize the ETIM as an insurgency and the seemingly unorganized (at least currently) Muslim Uyghur activities as rebellion.

The largest and most significant resistance movement against China is the Republic of China (ROC) on Taiwan. The ROC has been in a state of conflict with Communist China since 1927. In 1949, Communist China gained control of the mainland and established the People’s Republic of China (PRC), and the ROC relocated to Taiwan. The United Nations recognized the ROC as the legitimate Chinese government until 1971. However, only 13 sovereign states today continue to recognize the ROC as a legitimate government.65 Both the ROC and PRC recognize a “One China” policy, but both claim legitimacy over it. Based on the resilience and resistance methodology, the ROC should be categorized as a well-established belligerency. Figure 3 illustrates significant Chinese resistance movements across the resistance continuum.

Figure 3. Diagram of China’s resistance continuum

Source: courtesy of the authors, adapted by MCUP.

To complete a full analysis, one should employ the ACEOA acronym methodology to analyze other prevalent Chinese resistance movements, not simply the ROC. A comprehensive analysis allows an external sponsor to resilience or resistance in China to better evaluate threats and partnerships for instilling desired change. However, for the sake of brevity, this article simply uses the ROC as an example of assessing a resistance.

Phase Three: Assessing China’s Resistance Movements: The Republic of China

Actors

The ROC was formed by the Chinese Kuomintang (KMT) political party in 1919. Its most influential leader has been Chiang Kai-shek, who formed an alliance with the United States and the British Empire during World War II. Following military and political defeats on mainland China from 1949 onward, the KMT generally retained power in Taiwan until the year 2000. Currently, the island is governed by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), with a nationalist approach led by President Tsai Ing-wen. Tsai is recognized internationally, but her engagements have been limited to developing nations, including Eswatini, Guatemala, Belize, Palau, Nauru, the Marshall Islands, and Paraguay.66 International engagement is essential for legitimacy, but the lack of involvement from middle or major world powers indicates a reluctance to advocate for Taiwan, which would certainly anger China. The United Nations also does not recognize Taiwan.67 Still, in the last Taiwanese elections, the DPP received nearly 7 million of the 12 million total votes, double that of the KMT.68 The DPP retains control over the presidency as well as the nation’s legislature.

The Taiwanese population’s opinion in favor of reunification with China is at record lows. A census in 2022 showed that 28.6 percent desired the status quo to last indefinitely; 25.2 percent wanted to move toward independence; 5.2 percent wanted the status quo to remain for now and to decide on reunification at a later date; and only 1.3 percent desired to reunify with China immediately. When asked about identity, 63.7 percent identified as Taiwanese; 30.4 percent identified as both Taiwanese and Chinese; and only 2.4 percent identified as Chinese.69 These numbers indicate significant favor toward continued support for the ROC and opposition to the PRC, but certainly not a unified opinion on the matter.

While most nations do not recognize the ROC as a sovereign state, many share economic and national security interests with the independent island. The United States dubs its own relationship as “unofficial.”70 Ironically, the PRC is the ROC’s largest trading partner, accounting for 25 percent of its total trade in 2021. Other major partners include Japan (10 percent), Hong Kong (8 percent), and South Korea (6 percent).71 The United States continues to sell weapons to the ROC—about $500 million recently—and also conducts freedom of navigation operations in the Taiwan Strait, despite vehement PRC protest.72 In the face of strong resistance, the PRC has successfully and doggedly attacked the legitimacy of the ROC during the past two decades. For example, the CCP lobbied the International Olympic Committee to remove the ROC flag and anthem from the Olympics; athletes from the ROC must compete under the “Chinese Taipei” designation.73 Ultimately, the ROC attempts to secure its legitimacy through international support, while the PRC consistently threatens and erodes its status.

Causes

At its heart, the rationale for the continued existence of the ROC remains a compelling countervision for Zhongguo (greater China) to that of the CCP—essentially a democratic and free China. Another lesser cause includes an independent ROC, recognized as a sovereign state and not part of the PRC. However, that vision interferes with the objectives of Zhongguo, and these two ideas compete with one another. For the CCP, both causes cause a great deal of angst. The official position of the DPP is “establishing the Republic of Taiwan as a sovereign, independent, and autonomous nation” (i.e., the lesser vision).74 Meanwhile, the KMT continues to support Taiwan as part of greater China and as the legitimate choice opposed to the CCP (i.e., the greater vision). Based on the latest polling data presented, about two-thirds of the Taiwanese population agrees with one or both causes, but there remains no consensus. With a population of 23.5 million, Taiwan represents less than 2 percent of the total 1.4 billion people in the PRC.75 Consequently, achieving the greater vision appears increasingly less likely, but achieving the lesser vision remains possible.

Environment

The environment in which the ROC persists has some distinct advantages and disadvantages. The islands of Taiwan are separated from mainland China by a maritime border of about 160 kilometers. However, the ROC remains entirely dependent on sea lines of communication. While the maritime domain facilitates a degree of security, the loss of sea control around Taiwan could potentially spell its demise. For similar reasons, control of the air domain around Taiwan remains critical for its safety. In terms of authority, the ROC remains a democracy. This form of governance starkly clashes with the authoritarian nature of the PRC and comprises a visible internal threat to the CCP. On Taiwan, nearly 90 percent of people polled oppose the attempts of the CCP to integrate the islands into the PRC, and 75 percent stated that they were willing to pick up arms and fight for their independence.76 This indicates serious support to resistance efforts led by the DPP. In terms of technology, the ROC has access to—and Taiwan even produces—some of the most advanced products.77 The expertise on Taiwan for employing technology in support of resistance has real potential, not only in terms of defense but for disruption of the CCP on mainland China. In terms of external support, the ROC continues to officially attract recognition from smaller states, most recently Lithuania.78 Moreover, the potential is great for other supporters, including the United States, Australia, Japan, and South Korea. Support from the United States to legitimize the ROC is the lynchpin for a greater umbrella of nation states. A poll in August 2023 showed that 38 percent of Americans would support using the U.S. military to defend Taiwan.79

Organization

As is the case in most belligerencies, the ROC has all the trappings of statehood, including governance, rule of law, and a uniformed military. Its governance and leaders are veritably overt, without the need for an underground. The DPP is a mass organization, giving it legitimate weight. However, it is also easy to penetrate, and the threat of CCP infiltration into every major Taiwanese organization is very real and difficult to block. The military component of Taiwan, the ROC Armed Forces, consists of 169,000 active-duty uniformed personnel and 1.66 million reservists.80 In comparison, the PRC’s People’s Liberation Army consists of around 2 million regulars.81 The ROC spent $19 billion dollars on defense in 2023.82 In comparison, the CCP spent $200 billion.83 The ROC has 474 military aircraft.84 In comparison, the PLA wields 2,500.85 While the PRC has a substantial advantage over the ROC in terms of military power, the ROC has perhaps one of the most developed and capable armed components of resistance in the world. As far as an auxiliary, the ROC can leverage its entire economy to support resistance. Its greatest weakness is in food security; food self-sufficiency on Taiwan was 31 percent in 2021.86 Other important commodities, such as petroleum, ammunition, medical supplies, and equipment, all require the use of the air or sea domains for delivery. In so far as a public component, the DPP maintains an active campaign plan for legitimizing Taiwan as a nation state. Major Taiwanese influencers include nonprofit organizations such as Keep Taiwan Free, public organizations such as the Taiwanese American Council of Greater New York, and artists groups such as Shen Yun Performing Arts.87 In sum, the DPP wields a comprehensive resistance organization, and should armed conflict reinitiate with the PRC, the ROC has potential for increased international support.

Actions

The DPP pursues its aims of maintaining an independent state on Taiwan through international engagement, military defense, and economic prosperity. The last major battles between the ROC and PRC occurred during the Taiwan Straits Crises in 1954–55 and 1958, although artillery barrages continued through the early 1970s.88 From the time the PRC achieved legitimacy from the United Nations in 1971, hostilities have consisted mostly of provocative actions, such as violating air or sea space, rather than outright violence. While the ROC continues its military buildup and modernization, it has simultaneously embarked on a campaign for international recognition. For instance, the ROC “attended the World Health Assembly (WHA) as an observer from 2009 to 2016 and it attended the International Civil Aviation Organization’s (ICAO) Assembly in 2013.”89 Generally, the DPP lost some international recognition between 2000 and 2016, but the recent U.S. National Security Strategy in 2022, which lists the PRC as a threat to the international order, will likely create new opportunities for President Tsai to find support.90 To fund its resistance and independence, Taiwan has developed a robust economy and designed the production of technological goods that integrate into global supply chains. It is rated as the sixteenth largest world exporter in the world with gross domestic product of $33 billion in 2021, commensurate with Poland or Sweden.91 Considering these facts, one should surmise that the DPP represents a well-established belligerency to the rule of the CCP, as it seeks international recognition of its own legitimacy to rule over the islands of Taiwan, and it does so through international engagement, military defense, and economic prosperity.

Through the lens of the prescribed resistance identification methodology, this article has uncovered seven resistance organizations to the CCP, which it divides along the resistance continuum ranging from nonviolent protest to belligerency. These movements include the pan-democracy camp in Hong Kong, Tiananmen Square protesters, Falun Gong, Tibetan monks, Muslim Uyghurs, the ETIM, and the ROC. Following this identification, the article has evaluated Taiwan to provide meaningful analysis to one of China’s resistance organizations, the ROC, regarded as a belligerency. However, an assessment should be used for each major resistance organization, in addition to the ROC, for a comprehensive study.

Phase Four: Strategic Options in Support of Resilience or Resistance

To provide adequate analysis and a recommendation in support of foreign policy options for an external sponsor, this entire 12-step process should be used to illustrate a wholistic overview of a nation state in terms of resilience and resistance potential (steps 1–5), a deeper understanding of each major resistance organization (steps 6–11), and recommendations for action (step 12). The typical suggestion for action proposes one of three options: to support resilience of the current governing authority, to support resistance to it, or to do nothing. A full proposal should also consider the underlying factors of resistance movements that have given space for adversaries to operate; how to counter the frames and narratives of the adversary, either an external actor, a state authority, or the resistance; consideration of timings for various aspects of the response; measures of effectiveness; and risk assessment and mitigation.

Support Resilience

Supporting resilience in a partner nation state could involve numerous supporting packages that address the sources of instability within a state or even external threats to sovereignty. In the short term, this might include countering the objectives and means of each of the major resistance movements or their external sponsors, while long-term stability requires addressing the root grievances of the population—essentially subverting resistance. Several U.S. government publications help outline these approaches, such as the Department of State’s Stabilization Assistance Review: A Framework for Maximizing the Effectiveness of U.S. Government Efforts to Stabilize Conflict-Affected Areas and the Department of Defense’s Foreign Internal Defense, Joint Publication (JP) 3-22; Stability, JP 3-07; and Security Cooperation, JP 3-20.92 The Resistance Operating Concept, published by Joint Special Operations University Press, articulates one type of irregular strategy.93

Support Resistance

Proposals to support a particular resistance movement, or several of them, should begin with an interagency feasibility assessment. A resistance movement should have compatible goals with those of the sponsor and behave within acceptable norms of behavior. In terms of nonviolent struggle, the doctrine developed by Gene Sharp could prove a useful approach to advocate.94 If the external sponsor desires to include military support to an indigenous insurgency or to the armed component of an occupied state, the U.S. Army’s Unconventional Warfare at the Combined Joint Special Operations Task Force Level, Army Techniques Publication 3-05.1, provides the best guide.95

Do Nothing

Doing nothing should be the result of a conscious choice following a full evaluation of the options. In many cases, the direct involvement of an external sponsor in intrastate conflict might be regarded with a low likelihood of achieving the desired results. Simultaneously, finding an appropriate partner for resilience or resistance might not be possible. Additionally, overt support has foreign policy considerations, and covert support has risks to the same.

Conclusion

This article argues for a human-centric approach to conflict versus a conventional military analysis and indicates multiple options for either countering or supporting resistance movements to align with foreign policy objectives. This approach makes obvious that external support to resilience or resistance across diplomatic, information, military, and economic lines of effort offer substantial opportunities in shaping international relations, sometimes with irregular methods. By using the entire process, analysts can provide assessments to military leaders and policy makers that better recognize partners and adversaries and provide options to support a partner’s resilience or to support resistance(s) to inspire changes in an adversary’s behavior.

In terms of a case study, this article explores China—both the CCP and opposing domestic resistance movements—and offers an analysis regarding resilience and resistance typologies. The result comprises human-centric insights not currently present in either conventional war plans or foreign policy documents. Using publicly available datasets, it identifies seven prevalent resistance movements in China and aligns them according to their typology along the resistance continuum. Subsequently, it conducts a deeper analysis into one of those resistance movements—the ROC. By employing the prescribed approach to create this assessment, irregular methods for competition and conflict with China can be gleaned and leveraged to reinforce national policy objectives—either to support the CCP’s resiliency, to subvert the CCP’s legitimacy by supporting a resistance movement, or to do nothing. Conducting this type of analysis can assist military planners, foreign policy officers, and aid organizations to inform policies, campaign design, and diplomacy.

Practitioners can operationalize the resilience and resistance model and the resistance continuum to identify the most appropriate partner and subsequent complimentary support packages in intrastate conflicts. Each resistance movement is best countered or supported by unique methods. For instance, providing lethal force to a resilience or resistance partner is not always the best method of fomenting desired change. In contrast, the type of external support offered can also deliberately change the methods employed by a resistance and the nature of a conflict. Consequently, external partners can deliberately or incidentally change the nature of the intrastate conflict through the means delivered.

This research provides methodologies to complete a comprehensive analysis of resiliency and resistance for the purposes of influencing external support options for international policies. It recommends several methods to identify resistance movements by leveraging publicly available research from prominent scholastic institutions and then categorizing them by typology along the resistance continuum. After this, one might use the ACEOA methodology to subjectively provide a deeper understanding of one or more resistance organization(s). Finally, the scholar or practitioner must determine if external support to resilience or resistance comprises a viable strategy. Ultimately, such an irregular approach to address warfare, competition, and deterrence is long overdue.

Endnotes

- David H. Ucko and Thomas A. Marks, “Redefining Irregular Warfare: Legitimacy, Coercion, and Power,” Modern Warfare Institute, 18 October 2022.

- Josef Federman and Isaam Adwan, “Israel Strikes and Seals off Gaza after Incursion by Hamas, which Vows to Execute Hostages,” AP News, 9 October 2023.

- Consortium to Study Irregular Warfare Act of 2021, H.R. 5130, 117th Cong. (2021).

- Robert S. Burrell and John Collison, “A Guide for Measuring Resiliency and Resistance,” Small Wars and Insurgencies (2023), https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2023.2292942.

- For a description of irregular competition, see Robert S. Burrell, “How to Integrate Competition and Irregular Warfare,” Modern War Institute, 5 August 2021.

- Gordon McCormick, The Shining Path and Peruvian Terrorism (Santa Monica, CA: Rand, 1987). See also Burrell and Collison, “A Guide for Measuring Resiliency and Resistance.”

- The acronym DIME has been used for many years. See Donald M. Bishop, “DIME, not DiME: Time to Align the Instruments of U.S. Informational Power,” Strategy Bridge, 20 June 2018.

- “UN Human Rights Committee Provides New Guidance on the Right of Peaceful Assembly,” United Nations, 15 December 2020.

- “The Modern Civil Rights Movement and the Kennedy Administration,” John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, accessed 18 April 2023.

- Janell Hobson, “Harriet Tubman: A Legacy of Resistance,” Meridians 12, no. 2 (2014): 1–8, https://doi.org/10.2979/meridians.12.2.1.

- Patrick H. Breen, The Land Shall Be Deluged in Blood: A New History of the Nat Turner Rebellion (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015).

- Brie Swenson Arnold, “ ‘To Inflame the Mind of the North’: Slavery Politics and the Sexualized Violence of Bleeding Kansas,” Kansas History 38, no. 1 (Spring 2015): 22–39.

- Erin N. Hahn and W. Sam Lauber, Legal Implications of the Status of Persons in Resistance (Fort Bragg, NC: U.S. Army Special Operations Command, 2013).

- Robert L. Helvey, On Strategic Nonviolent Conflict: Thinking about the Fundamentals (East Boston, MA: Albert Einstein Institution, 2004).

- Kwabena P. Slaughter, “The Nonviolent Imagination: Trickster Gandhi Revisited,” Philosophy and Social Action 29, no. 3 (2003): 41–50.

- Simon Stevens, “Violence, Political Strategy and the Turn to Guerrilla Warfare by the Congress Movement in South Africa,” Journal of Southern African Studies 47, no. 6 (2021): 1011–28, https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070.2021.1974224. Also see Thula Simpson, “Mandela’s Army: Urban Revolt in South Africa, 1960–1964,” Journal of Southern African Studies 45, no. 6 (2019): 1093–1110, https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070.2019.1688619.

- Stephen Zunes, “Unarmed Insurrections against Authoritarian Governments in the Third World: A New Kind of Revolution,” Third World Quarterly 15, no. 3 (1994): 403, https://doi.org/10.1080/01436599408420388.

- Mark R. Beissinger, “The Semblance of Democratic Revolution: Coalitions in Ukraine’s Orange Revolution,” American Political Science Review 107, no. 3 (August 2013): 574–92, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055413000294.

- Colin Agur and Nicholas Frisch, “Digital Disobedience and the Limits of Persuasion: Social Media Activism in Hong Kong’s 2014 Umbrella Movement,” Social Media + Society 5, no. 1 (January–March 2019), https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119827002.

- Hahn and Lauber, Legal Implications of the Status of Persons in Resistance, 49.

- Breen, The Land Shall Be Deluged in Blood.

- See Zunes, “Unarmed Insurrections against Authoritarian Governments in the Third World.” See also Sahan Savas Karatasli, “The Twenty-First Century Revolutions and Internationalism: A World Historical Perspective,” Globalizations 16, no. 7 (2019): 985–97, https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2019.1651525.

- Zoltan Barany, “Comparing the Arab Revolts: The Role of the Military,” Journal of Democracy 22, no. 4 (October 2011): 24–35, https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2011.0069.

- Andrii Gladun, “Impact of Repression on Mobilization: The Case of the Euromaidan Protests in Ukraine,” Social Justice 46, no. 2/3 (2019): 29–50. See also Winter on Fire: Ukraine’s Fight for Freedom, directed by Evgeny Afineevsky (Los Gatos, CA: Netflix, 2015).

- Gjorjji Veljovski, “Terrorism or Insurgency?: The Most Common Strategic Fallacy,” Contemporary Macedonian Defense 20, no. 39 (2020): 107–19.

- Ranbir Singh, “Insurgency and International Law and Its Legal Consequences,” National Law School of India Review, 18 June 2012.

- Martha Crenshaw Hutchinson, Revolutionary Terrorism: The FLN in Algeria, 1954–1962 (Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 1978).

- Ed Moloney, A Secret History of the IRA (London: Penguin, 2002).

- Joe Clare and Vesna Danilovic, “The Geopolitics of Major Power Interventions in Civil Wars,” Political Research Quarterly 75, no. 1 (2022): 20–34, https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912920976910.

- Henry Clews, “Great Britain and the Confederacy,” North American Review 149, no. 393 (August 1889): 215–22.

- Global Nonviolent Action Database, accessed 13 September 2023.

- “Mapping Nonviolent and Violent Campaigns and Outcomes (NAVCO),” Harvard University Dataverse, accessed 13 September 2023.

- “Mass Mobilization Protest Data,” Harvard University Dataverse, accessed 13 September 2023.

- “Global Protest Tracker,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, accessed 13 September 2023.

- Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project, accessed 13 September 2023.

- “Uppsala Conflict Data Program,” Uppsala University Department of Peace and Conflict Research, accessed 13 September 2023.

- As one example, the Global Database of Events, Language and Tone (GDELT) project offers both raw data as well as analysis on events around the world since 2013 and “monitors the world’s broadcast, print, and web news from nearly every corner of every country in over 100 languages and identifies the people, locations, organizations, themes, sources, emotions, counts, quotes, images and events driving” social change. With so much data, this website can become overwhelming, but it provides good resources for compiling a more comprehensive narrative. See GDELT Project, accessed 13 September 2023.

- See David Collier, Jody LaPorte, and Jason Seawright, “Putting Typologies to Work: Concept Formation, Measurement, and Analytic Rigor,” Political Research Quarterly 65, no. 1 (March 2012): 217–32, https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912912437162.

- Jonathon B. Cosgrove and Erin N. Hahn, Conceptual Typology of Resistance (Fort Bragg, NC: U.S. Army Special Operations Command, 2018). This excellent study remains worthy of a fuller examination than is offered here.

- Cosgrove and Hahn use the definition in Jeremy M. Weinstein, Inside Rebellion: The Politics of Insurgent Violence (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 19, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511808654.

- Cosgrove and Hahn, Conceptual Typology of Resistance, 4–6.

- Cosgrove and Hahn, Conceptual Typology of Resistance, 7–16.

- For more information, see Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College (website); and M. Chris Mason, “COIN Doctrine is Wrong,” Parameters 51, no. 2 (2021): 19–34, https://doi:10.55540/0031-1723.3065.

- Cosgrove and Hahn, Conceptual Typology of Resistance, 17–24.

- See Scott Atran, “The Devoted Actor: Unconditional Commitment and Intractable Conflict across Cultures,” Current Anthropology 57, no. S13 (June 2016): 192–203, https://doi.org/10.1086/685495.

- See Joint Warfighting, Joint Publication (JP) 1 (Washington, DC: Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2023).

- For a brief explanation of these, see Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing, 2016), 515–19.

- Cosgrove and Hahn, Conceptual Typology of Resistance, 25–34.

- See Dan Garrett, “Superheroes in Hong Kong’s Political Resistance: Icons, Images, and Opposition,” Political Science and Politics 47, no. 1 (January 2014): 112–19, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096513001637.

- Cosgrove and Hahn, Conceptual Typology of Resistance, 29.

- Paul J. Tompkins Jr., Undergrounds in Insurgent, Revolutionary, and Resistance Warfare (Fort Bragg, NC: U.S. Army Special Operations Command, 2012), 10–12.

- See Unconventional Warfare at the Combined Joint Special Operations Task Force Level, Army Techniques Publication (ATP) 3-05.1 (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 2021).

- Tompkins, Undergrounds in Insurgent, Revolutionary, and Resistance Warfare, 75–87.

- Cosgrove and Hahn, Conceptual Typology of Resistance, 4–6.

- Cosgrove and Hahn, Conceptual Typology of Resistance, 4–6.

- Burrell and Collison, “A Guide for Measuring Resiliency and Resistance.”

- See “Mass Mobilization Protest Data.”

- “Tibetan Monks Protest Chinese Rule (Lhasa Protests), 2008,” Global Nonviolent Action Database, accessed 3 October 2023.

- See “Mass Mobilization Protest Data.”

- See “Mapping Nonviolent and Violent Campaigns and Outcomes (NAVCO).”

- The CCP has issued arrest warrants for the 21 leaders of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests in Beijing. Many of these persons remain active and vocal in public resistance efforts. See Eddie Cheng, Standoff at Tiananmen: How Chinese Students Shocked the World with a Magnificent Movement for Democracy and Liberty that Ended in the Tragic Tiananmen Massacre in 1989 (blog), 28 November 2020. See also Sarah Cook, “Falun Gong: Religious Freedom in China,” Freedom House, 2017.

- See “Uppsala Conflict Data Program.”