Chapter 8

The Birth of Marine Combat Aviation

Talbot and Robinson

By Laurence M. Burke II, PhD, Aviation Curator

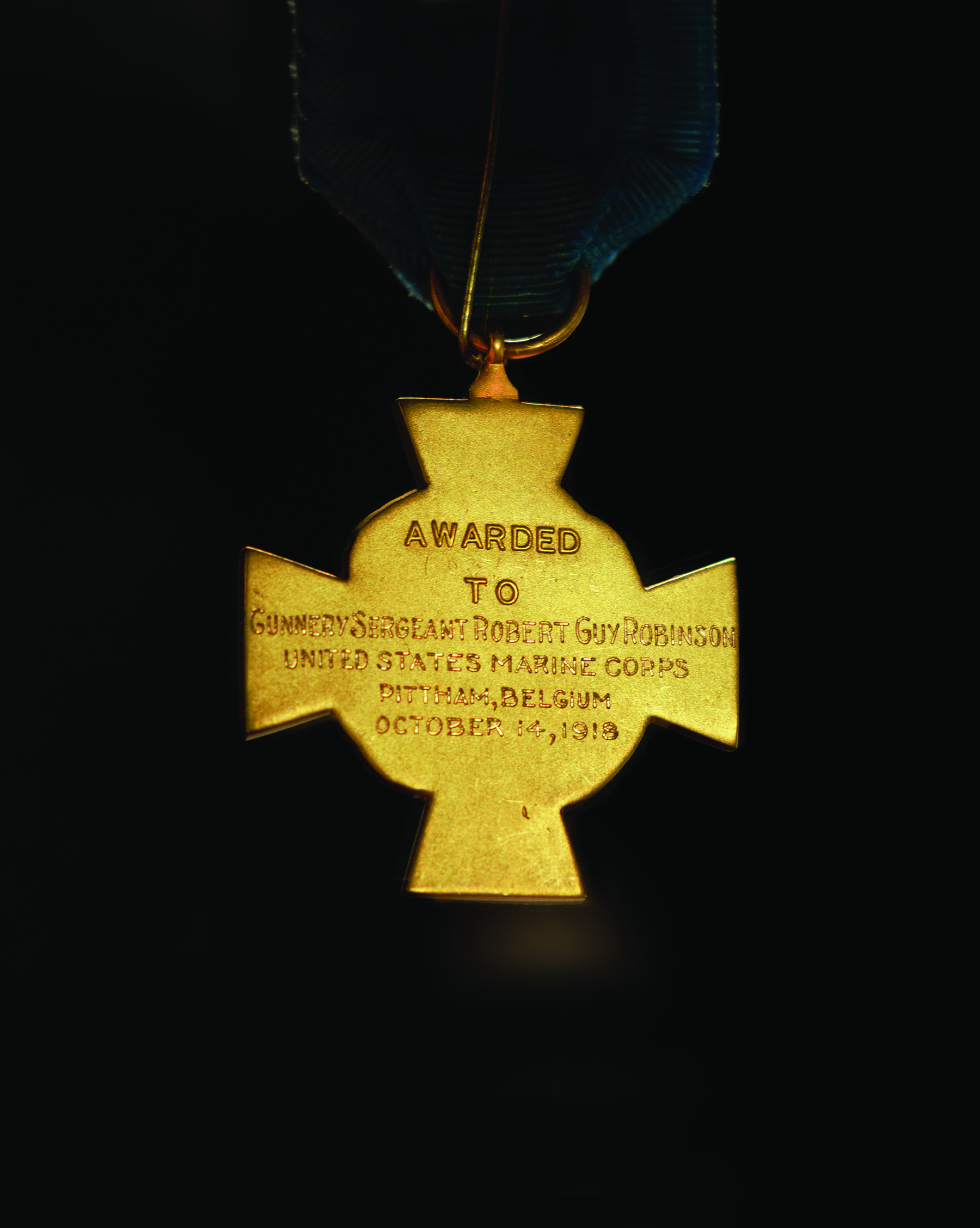

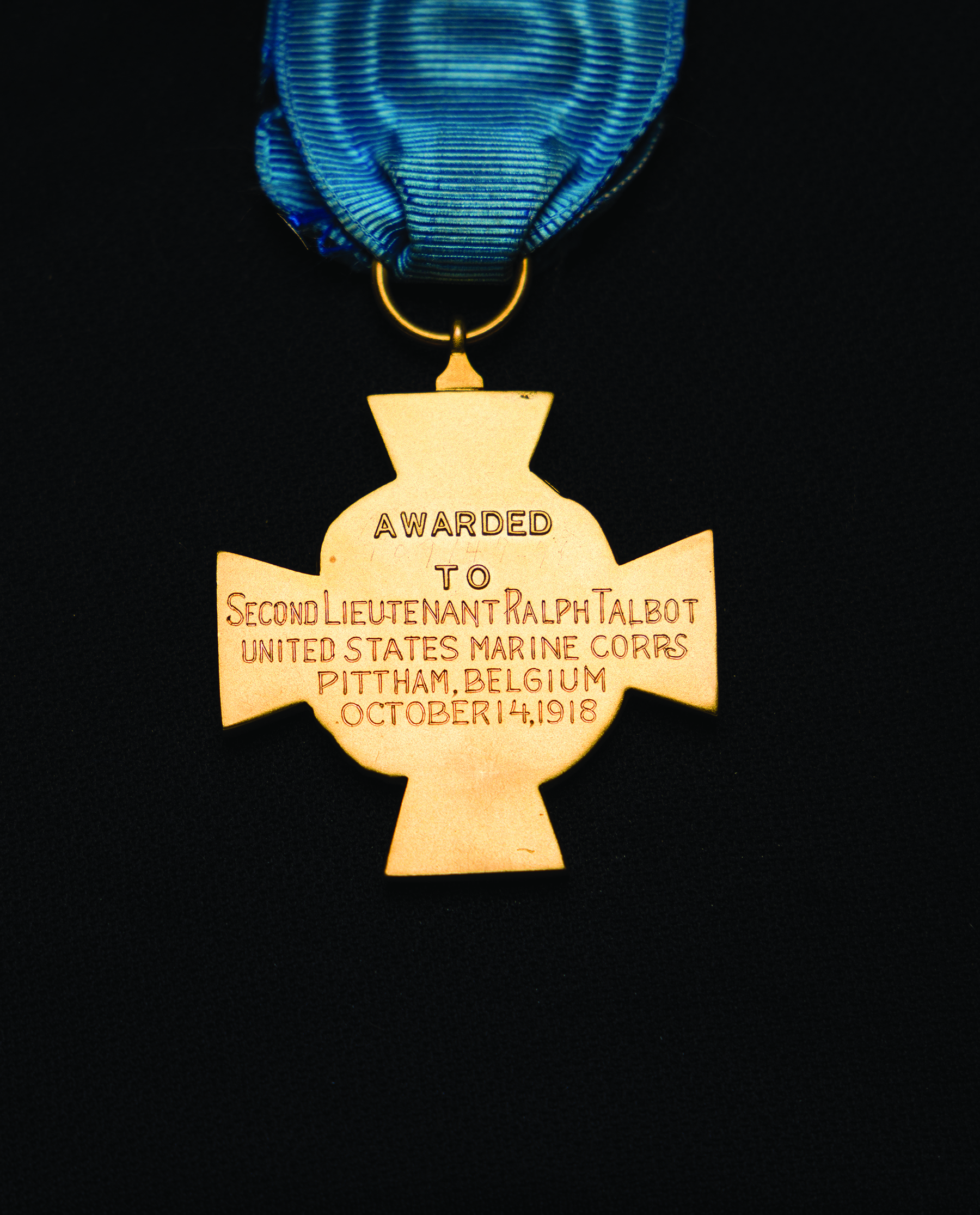

Featured artifacts: Medal of Honor, Gunnery Sergeant Robert G. Robinson (1974.2871.1); and Medal of Honor, Second Lieutenant Ralph Talbot (1981.526.1)

GySgt Robert G. Robinson’s Medal of Honor (obverse).

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

GySgt Robert G. Robinson’s Medal of Honor (reverse).

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

2dLt Ralph Talbot’s Medal of Honor (obverse).

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

2dLt Ralph Talbot’s Medal of Honor (reverse).

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

The Medals of Honor awarded to U.S. Marine Corps pilot Second Lieutenant Ralph Talbot and his observer/gunner, Gunnery Sergeant Robert G. Robinson, for their actions in France in October 1918 were the first such decorations awarded to Marine aviators. The two Marines served in Northern France during World War I with the Marine Day Wing of the United States’ Northern Bombing Group (NBG). Their most harrowing action during the war, and the primary reason for their Medals of Honor, was a running fight on 14 October when they were separated from their group during a bombing raid and had to fight off numerous German fighter planes alone.

The NBG was a Navy-Marine Corps organization with a convoluted development beginning in early 1918. By the end of May, the group’s final form had been set: four Navy night bomber squadrons and four Marine day bomber squadrons all targeting German U-boat bases in the occupied Belgian cities of Bruges, Zeebrugge, and Ostend. While the organization was set, however, resources to put the plan into action were still lacking.

Marine Corps aviator Major Alfred A. Cunningham was the source of one of the ideas that led to the creation of the NBG. He had spent much of the winter and spring of 1918 working to assemble personnel for four Marine squadrons of fighter aircraft. He was still working to gather the necessary personnel when the Navy informed him that his Marine squadrons would fly day bombers instead of fighters. One source for these badly needed aviators was the Naval Aviation School at Pensacola, Florida. Cunningham convinced numerous fledgling naval aviators that they would get into action in Europe much sooner if they transferred to the Marine Corps and Cunningham’s First Marine Aviation Force (FMAF).[1]

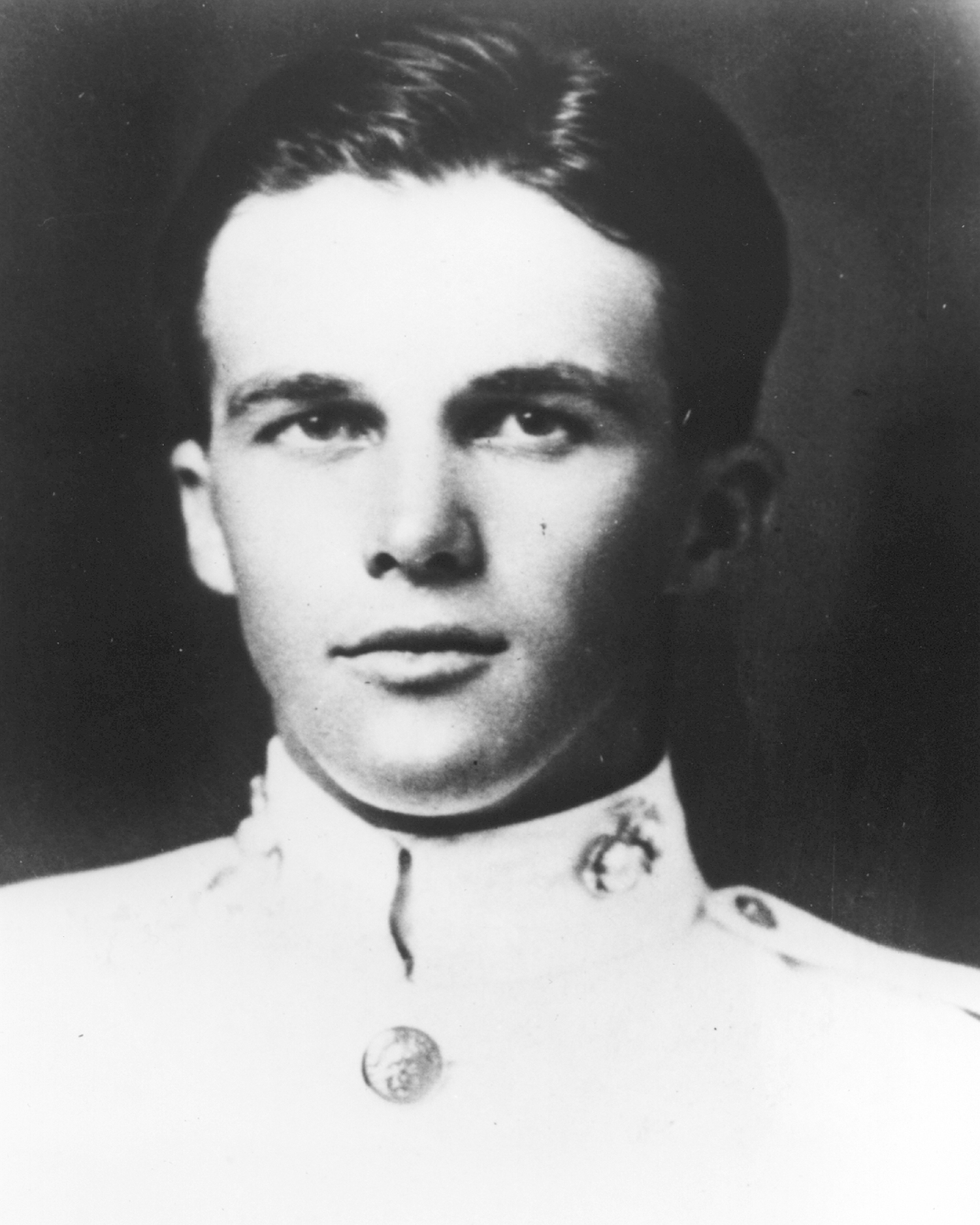

A commissioning photograph of Ralph Talbot.

Marine Corps History Division.

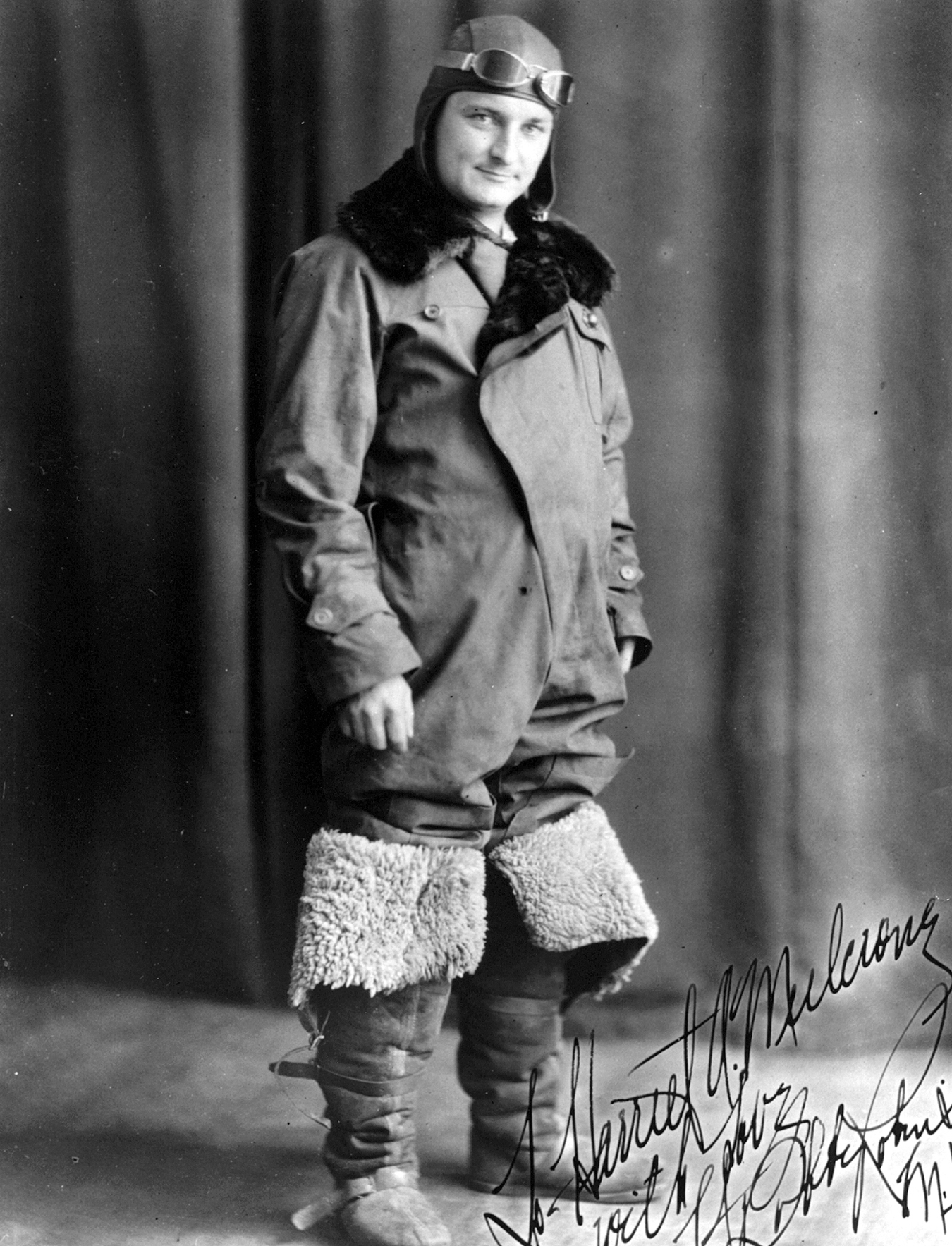

Robert Robinson wearing his flying gear. Between the wind across the open cockpits and the extreme cold at high altitudes, every flight was a fight to stay warm.

Marine Corps History Division.

Ralph Talbot was one of these recruits. Interested in flying, he joined the Navy’s aviation training program in October 1917. He earned his naval aviator’s certificate on 10 April 1918 and recommissioned in the Marine Corps little more than a month later. He was assigned to Squadron C of the FMAF. Robert Robinson had enlisted in the Marine Corps in May 1917 and was serving with the 92d Marine Company at Quantico, Virginia, when he was reassigned (likely as a volunteer) to Squadron C on 17 June 1918. The FMAF’s first three squadrons (A, B, and C) boarded a transport for Europe on 18 July. The fourth squadron, D, was still forming in the United States and would ship overseas in October.[2]

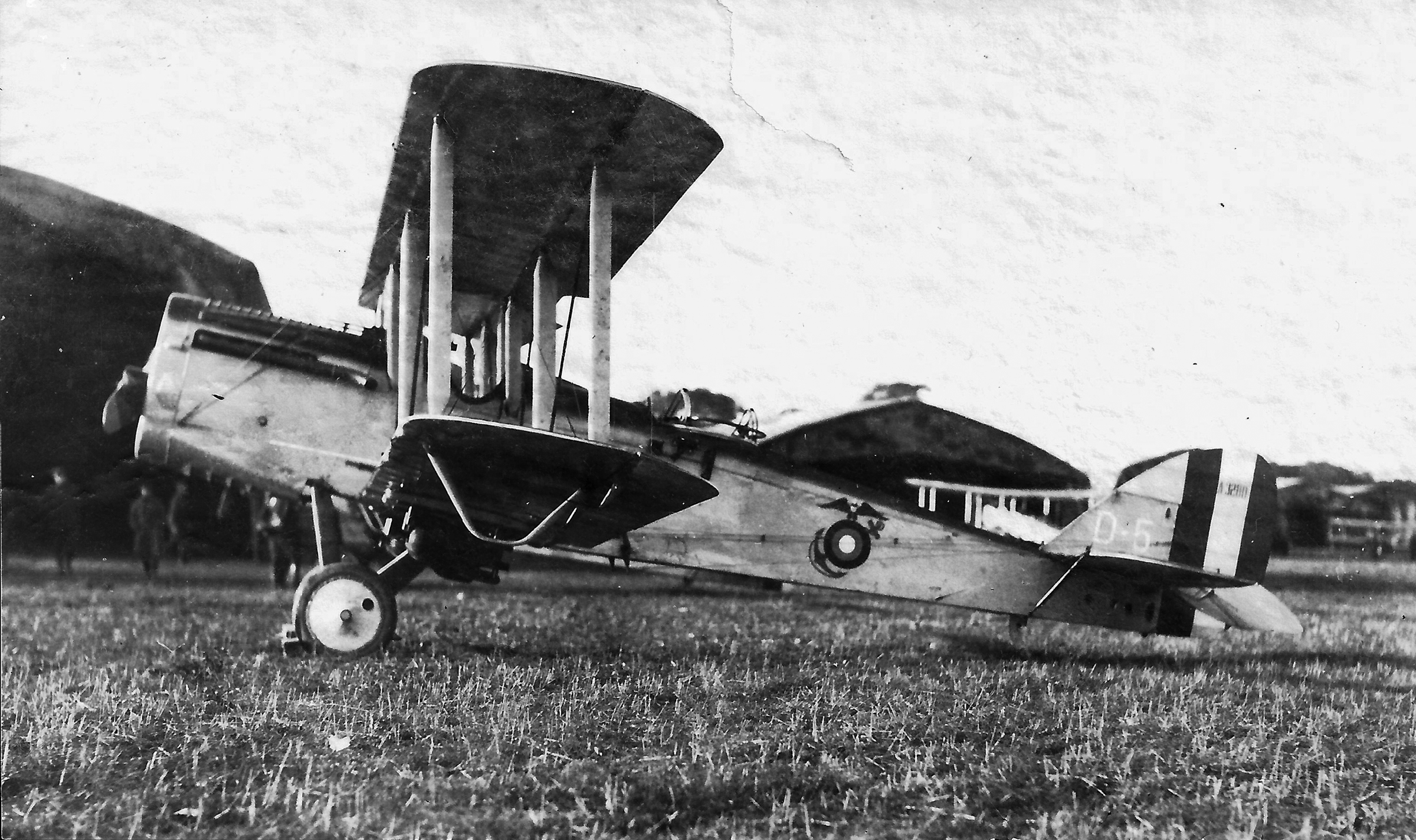

Aircraft D-5 (BuNo A3280), a U.S.-built DH-4. Note the FMAF logo on the side of the plane (incorporating the U.S. roundel) and the bombs on racks under the wings.

Marine Corps History Division.

After arrival of the FMAF in France, Cunningham discovered that his squadrons’ aircraft—which he had been told were in France—were not ready for use. Production delays, shipping problems, and confusion at the French port over where the aircraft crates were supposed to go (with few people having heard of the NBG yet) left his squadrons without aircraft and nothing to do. As it happened, British day bombing squadrons in the area had full complements of aircraft but a shortage of aircrew to fly them. These former Royal Naval Air Service squadrons, now part of the new Royal Air Force (RAF), were flying the British Airco DH.4 two-seat biplane and the very similar Airco DH.9. Cunningham quickly arranged for his Marine aircrews to fly with the RAF squadrons while their own aircraft were being located, uncrated, reassembled, repaired (as many suffered damage during shipping), and updated as necessary.[3]

Marine Day Wing planes prepare for a mission in France.

Marine Corps History Division.

Talbot and Robinson were probably first thrown together when assigned to the RAF pilots pool in Audembert, France, in September 1918. There, they received training in RAF equipment and tactics. By the end of the month, they were assigned to the RAF’s No. 218 Squadron. While 218 Squadron was a DH.9 squadron, Talbot and Robinson, then a corporal, flew in one of the first U.S.-built DH-4s to reach the Marines, aircraft D-1. On 3 October, they helped airdrop food (canned rations in sacks with some dirt to cushion the impact) to French troops who had been isolated by German forces and impassable mud. The sacks of food were dropped from about 500 feet, exposing the planes to intense antiaircraft fire from German rifles and machine guns. During the next several days, the two participated in more traditional bombing raids. Their U.S.-built DH-4, with its U.S.-designed Liberty engine, was faster than the British DH.9s, so the Marines were often tasked with protecting the raids from enemy fighters, using twin-fixed forward-firing guns and a single machine gun on a flexible mount fired by the observer/gunner. Talbot and Robinson experienced their first aerial combat during a mission on 8 October, when nine German fighters attacked their formation. The two Marines engaged all nine, shooting one down and successfully making their escape. Their time with 218 Squadron came to an end on 12 October, when they flew their DH-4 to La Fresne aerodrome, one of the Day Wing’s bases in France.

By this time, the Day Wing had been able to obtain enough aircraft—a mixture of U.S.-built DH-4s and British-built DH.9As, both powered by Liberty engines—to mount its own bombing missions. The first of these occurred on 14 October, when eight Day Wing bombers took off from La Fresne to attack a railway center at Thielt, Belgium. One turned back with mechanical problems, but the remaining seven (including Talbot and Robinson’s plane) struck the objective and turned for home. On the way back to base, they encountered 12 German fighters. Two of the Marine planes fell out of formation due to engine trouble, but the Germans seemed to concentrate only on one of those, the one crewed by Talbot and Robinson.

Robinson quickly shot down one of the attackers, but two more attacked from below. One of the German planes managed to shatter Robinson’s left elbow with bullet fire, leaving his arm hanging on by a few tendons. Robinson bravely continued to fire one-handed at the enemy, but his gun jammed. Talbot was not passive while this was going on, maneuvering his airplane around with the intention of using his forward-firing machine guns, but both jammed while he was pressing his attack. In the meantime, Robinson managed to clear the jam in his gun, and he may have shot down a second German plane, but he was struck again by bullets, once in the stomach and once in the thigh. This caused him to collapse, unconscious, in the rear cockpit, on top of the control cables, making it difficult for Talbot to control the plane. In spite of this, Talbot—whose guns were still jammed—faked an attack on another German plane. His bluff worked, and the German pilot turned away, giving Talbot an escape route. Talbot dove toward the ground, evading fire from the one German plane that followed him and crossed over the front lines at a mere 15 meters above ground. Once safely on the Allied side of the front (the German pilot did not follow him across), Talbot headed for a nearby Belgian airfield located next to a field hospital. Surgeons there were able to save Robinson’s life and even reattach his arm. Talbot, meanwhile, was able to fly his damaged aircraft back to La Fresne.

This painting by Col Charles H. Waterhouse, USMCR (Ret), depicts Talbot escaping across the trenches with an unconscious Robinson slumped over in the rear seat. German soldiers are firing rifles and machine guns at the airplane.

National Museum of the Marine Corps.

Robinson spent the rest of the war recovering from his wounds, while Talbot continued to fly missions for the Day Wing. On 26 October, Talbot was making a flight to test a rebuilt engine. The engine was unable to provide power for a proper climb, and the plane’s landing gear clipped an embankment around the airfield’s bomb dump. The impact tore off the gear and flipped the plane over, throwing the observer/gunner free but trapping Talbot under the plane, which exploded in a mass of flames. Despite the plane’s ammunition beginning to cook off, men rushed to try to put out the fire, move bombs to safety, and rescue Talbot. Unfortunately, their efforts to save Talbot were in vain—when the flames were extinguished, Talbot’s body was found with the engine resting on his chest. He likely died in the initial crash.[4]

The aftermath of Talbot’s fatal crash.

Marine Corps History Division.

Talbot and Robinson were ultimately awarded the Medal of Honor on 11 November 1920 for their actions on 14 October 1918. The citations for both Marines are the same and state that Talbot fired at the enemy to make his escape, but before he died Talbot had told the story of his guns jamming to a fellow pilot, who in turn recorded the tale in a letter to Talbot’s mother following Talbot’s death.

The National Museum of the Marine Corps holds both Marines’ medals in its collection. Robinson’s is on display in the museum’s World War I gallery, while Talbot’s is currently in storage. Incidentally, these two medals look different from the Medal of Honor’s more familiar star-shaped design. In 1919, U.S. secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels decided that there should be separate designs for Navy Medals of Honor awarded for combat and noncombat heroism. The existing star shape became the noncombat version. Talbot and Robinson received the new combat version of the Medal of Honor, designed by Tiffany & Company of New York City, which has since become known as the “Tiffany Cross.” In August 1942, the U.S. Department of the Navy decided that the Medal of Honor would only be awarded for heroism in combat and that the star-shaped design would be used.[5]

Endnotes

[1] Laurence M. Burke II, “ ‘What to Do with the Airplane?’: Determining the Role of the Airplane in the U.S. Army, Navy, and Marine Corps, 1908–1925” (PhD diss., Carnegie Mellon University, 2014), 661–97; and LtCol Edward C. Johnson, Marine Corps Aviation: The Early Years, 1912–1940 (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1977), 15–17.

[2] Alan E. Durkota, Medal of Honor, vol. 1, Aviators of World War One (Stratford, CT: Flying Machines Press, 1998), 75, 78; and Johnson, Marine Corps Aviation, 19.

[3] Burke, “What to Do with the Airplane?,” 702–14; and Johnson, Marine Corps Aviation, 20–24.

[4] Johnson, Marine Corps Aviation, 22–24; and Durkota, Medal of Honor, 78–85.

[5] John E. Strandberg and Roger James Bender, The Call of Duty: Military Awards and Decorations of the United States of America, 2d ed. (San Diego, CA: R. James Bender Publishing, 2004), 72.