Chapter 6

SeaGoing Art

A Marine Tradition of Seabags

By Kater Miller, Curator

Featured artifacts: Painted Duffel Bag (2014.37.1) (Painted Green, Trip Markings, Dragons); Painted Duffel Bag (2014.60.1) (Trip Markings, Tank Painting and Art); Painted Duffel Bag (2015.207.1) (Iceland); Painted Duffel Bag (2010.20.1) (Yorktown Survivor); Painted Duffel Bag (2014.61.1) (I Got Mine); Painted Duffel Bag (1994.84.1) (1930s, Old Eagle, Globe, and Anchor); and Painted Duffel Bag (FIC-4.1.416) (Fleischauer)

A faded seabag specked with dust

Lies mute upon the attic floor.

Nobody knows where it has traveled

Except its owner and the Corps.

~ Harry A. Koch[1]

The humble seabag might be the most ubiquitous piece of equipment that an enlisted U.S. Marine will own during their career. In boot camp, the seabag is one of the very first things a young recruit is issued. After the recruit receives their seabag, they then receive the rest of their issue, which they proceed to cram into it. This rite of passage was as true in 1943 at the Marine Corps Recruit Depots at Parris Island, South Carolina, and San Diego, California, as it is today.

Enlisted sailors on warships in the early frigate navy originally had sea chests, but they eventually switched to bags that look like modern seabags today to save space aboard the cramped, wooden warships. Seabags held sailors’ uniforms, and early on, sailors had to carry their mattress and hammock attached to their seabag.

The seabags of the nineteenth century look very similar to those today, consisting of a flat bottom and cylindrical tube and a closing mouth, closed by a drawstring or heavy grommets over a loop. Originally, these bags were considered government property. A Marine Corps manual from 1916 stated that a Marine leaving the Corps would return their canvas seabag to the quartermaster, who would clean it and repair it if necessary, and it would then be reissued to the next Marine who required one. This practice continued until at least World War II with excess bags.

Almost immediately, sailors and Marines began decorating their seabags to show personal flair. They wrote their names on them; they drew on and painted them with ornate designs; and they wrote the locations where they had been. Sometimes, a seabag displayed a unit’s tactical markings or insignia. This personalization gives us, the modern viewer, a glimpse into the lives of these Marines and sailors.

In World War II Marine Corps veteran Robert H. Leckie’s autobiography, Helmet for My Pillow, he stated that he packed his seabag before landing at Guadalcanal in August 1942 and did not see it again until after the war.[2] During World War II, this was the case for many of the Marines deployed in the Pacific theater. They lived out of their knapsacks and haversack combinations along with their 782 gear and utility or combat uniforms. When the war ended, tens of thousands of seabags made their way to warehouses in the United States and waited for their owners to pick them up. After a while, the Corps advertised the warehouses in newspapers and Leatherneck magazine in the hopes of getting the bags matched with their owners.

The canvas bags of World Wars I and II vary slightly from today. Today, Marines’ seabags are green, made of nylon, and have shoulder straps to make them easier to carry. When this author deployed on the amphibious assault ship USS Peleliu (LHA 5) in 2003, every Marine in their berthing space had one small personal locker to use, and they had to store their seabags in a big storage room in a large pile. Finding one’s own seabag was not easy. It seems that personalizing one’s seabag allowed for a more practical way of finding the bag in a large mass of featureless, identically constructed bags. Doing so might allow a Marine to locate their seabag more quickly.

This exhibit at the National Museum of the Marine Corps (NMMC) includes seven personalized seabags that show a glimpse of their owners’ character. The Marines who altered these bags had different levels of artistic ability. The bags span a little more than a decade in time and range from the inane to the sultry and profane, but they all serve as diaries of the Marines’ experiences and help tell stories of their owners. These bags also demonstrate how diverse the Marine Corps is, and how Marines truly serve in any clime and place.

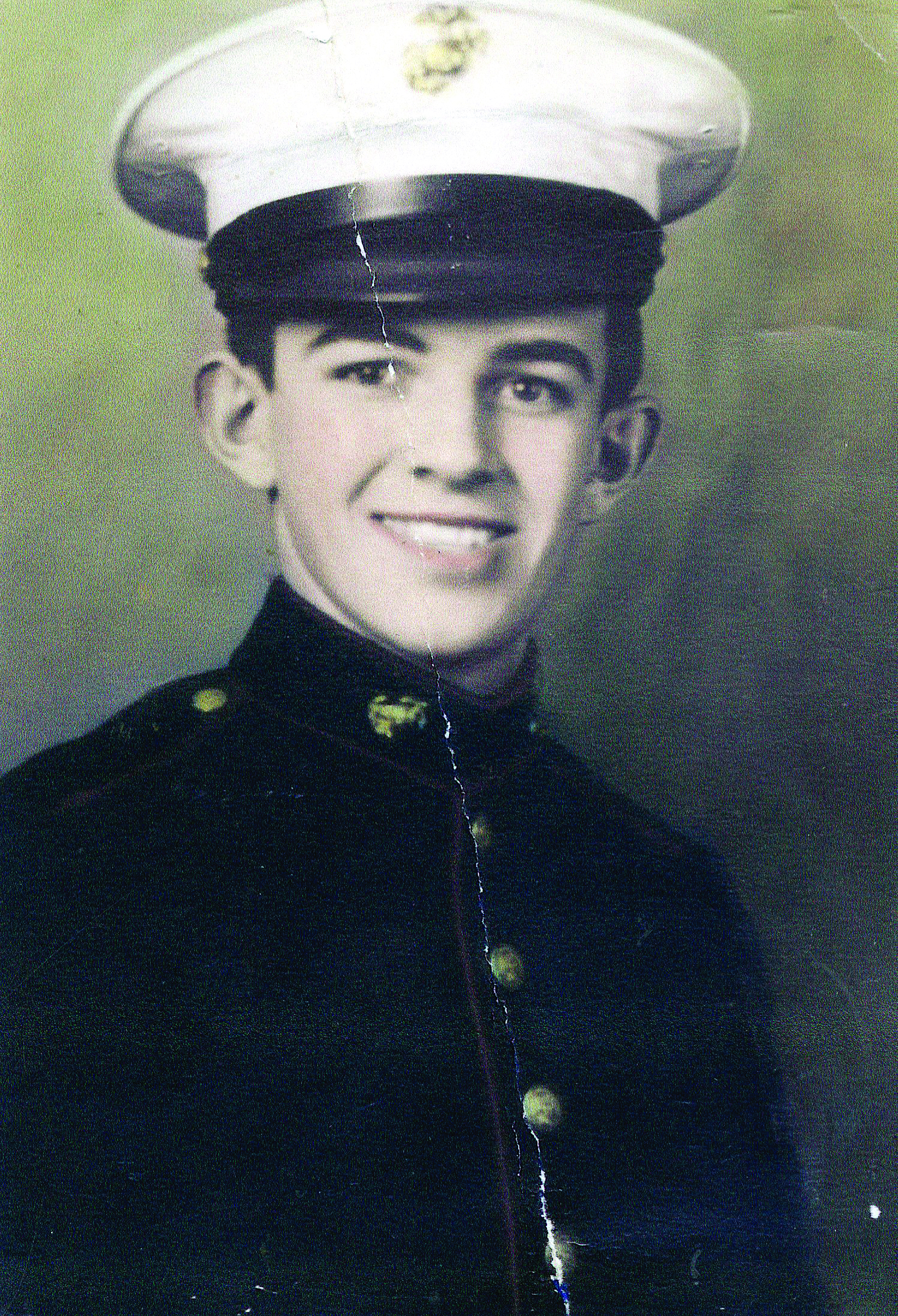

Alastair C. Parr

Alastair C. Parr’s painted seabag. On this side, Parr’s hometown is visible, along with a dragon.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

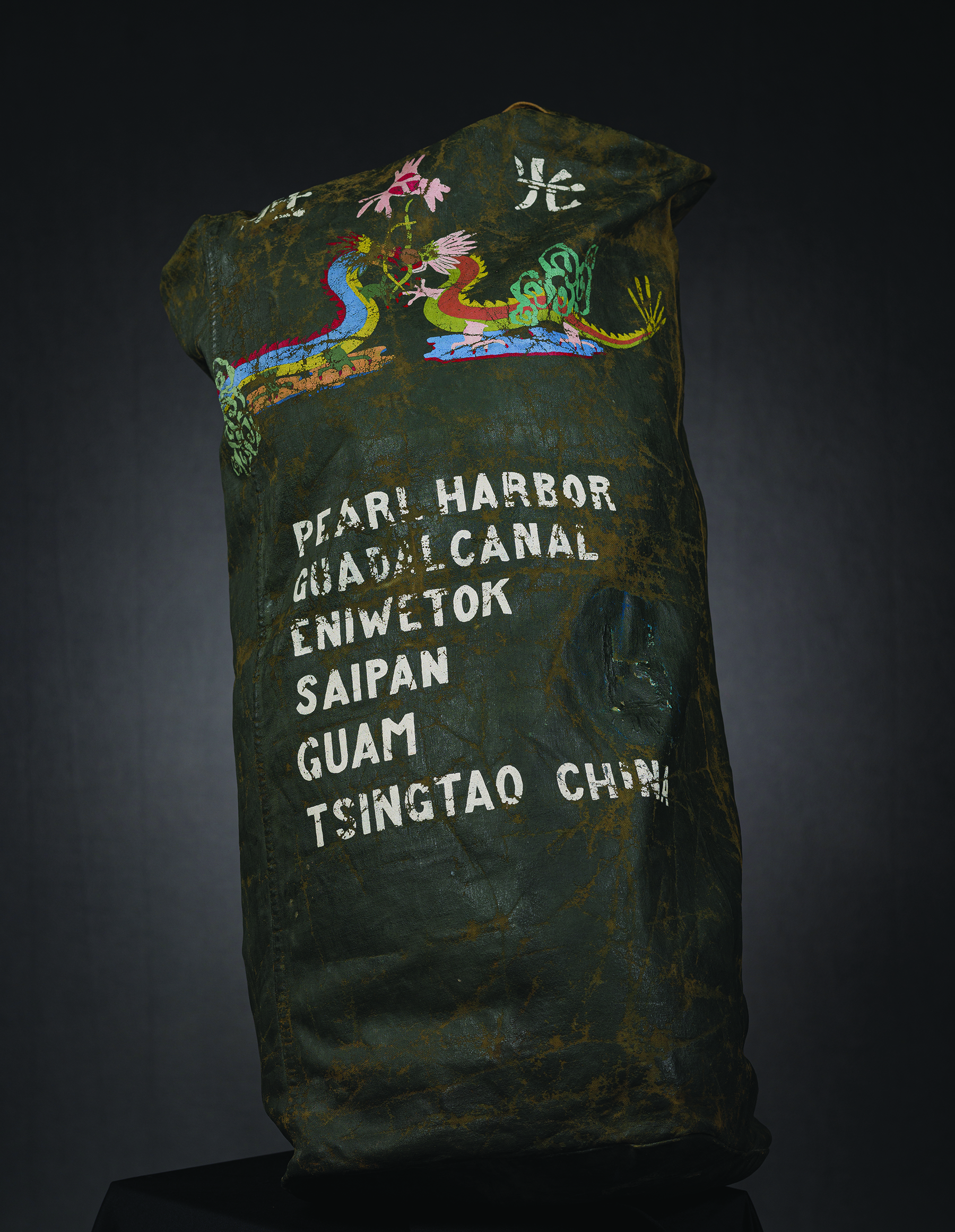

This seabag was owned by Private First Class Alastair C. Parr of Sayre, Pennsylvania. Born on 16 April 1926, he joined the Marine Corps in the spring of 1944. After training, he was assigned to the 15th Marines, an artillery regiment of the 6th Marine Division that had been formed on Guadalcanal in late 1944. He landed on Okinawa on 1 April 1945, just shy of his 19th birthday, and went through the nearly three-month-long battle unscathed. It is unclear why Okinawa is not represented on his bag while other Pacific battlefields are; he did not arrive in the Pacific in time to see combat on Guadalcanal, Eniwetok, Saipan, or Guam—these were just places that he visited either as part of a replacement draft or while training en route to Okinawa.

Alastair C. Parr.

National Museum of the Marine Corps.

The Battle of Okinawa was the last major ground campaign of World War II, as well as the only combat operation for the 6th Marine Division. The Marines that survived the battle then prepared to assault the main islands of Japan, a campaign that would have caused a terrible loss of life. However, the two atomic bombs dropped on Japan in August 1945 abruptly ended the war, but such a sudden end meant that there were still huge contingents of Japanese forces deployed throughout Asia. The Allied effort quickly transformed to oversight of the surrender and demobilization of these troops. Some Marines went to Japan, while others, such as Parr’s unit, went to China. For the first time since 8 December 1941, the U.S. Marines would be in China again.

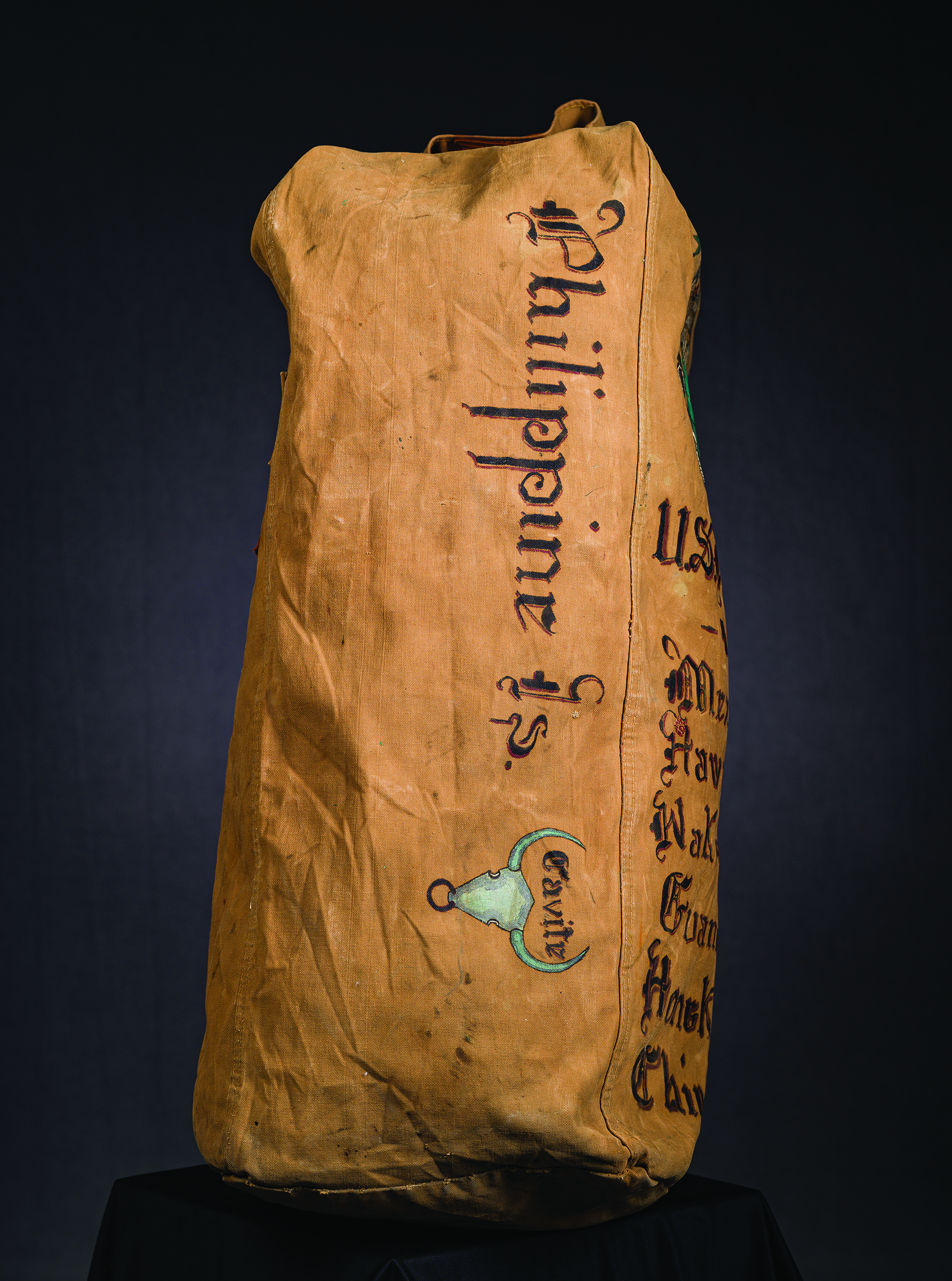

Parr’s seabag also displays a list of places he traveled, though Okinawa is conspicuously absent.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

Parr had his seabag painted in China while on occupation duty there. In addition to the bag bearing the name of his hometown, it is ornately painted with dragons and designs. For some reason, Parr chose to have the khaki-color canvas bag painted green, which has flaked off over the years. Enlisted Marines did not have a lot of money to ship items home, and the massive demobilization effort after the war ended kept many of them from buying a lot of souvenirs. This bag became a souvenir for the young Marine, in addition to serving as a practical item that he could use to carry his essential gear.

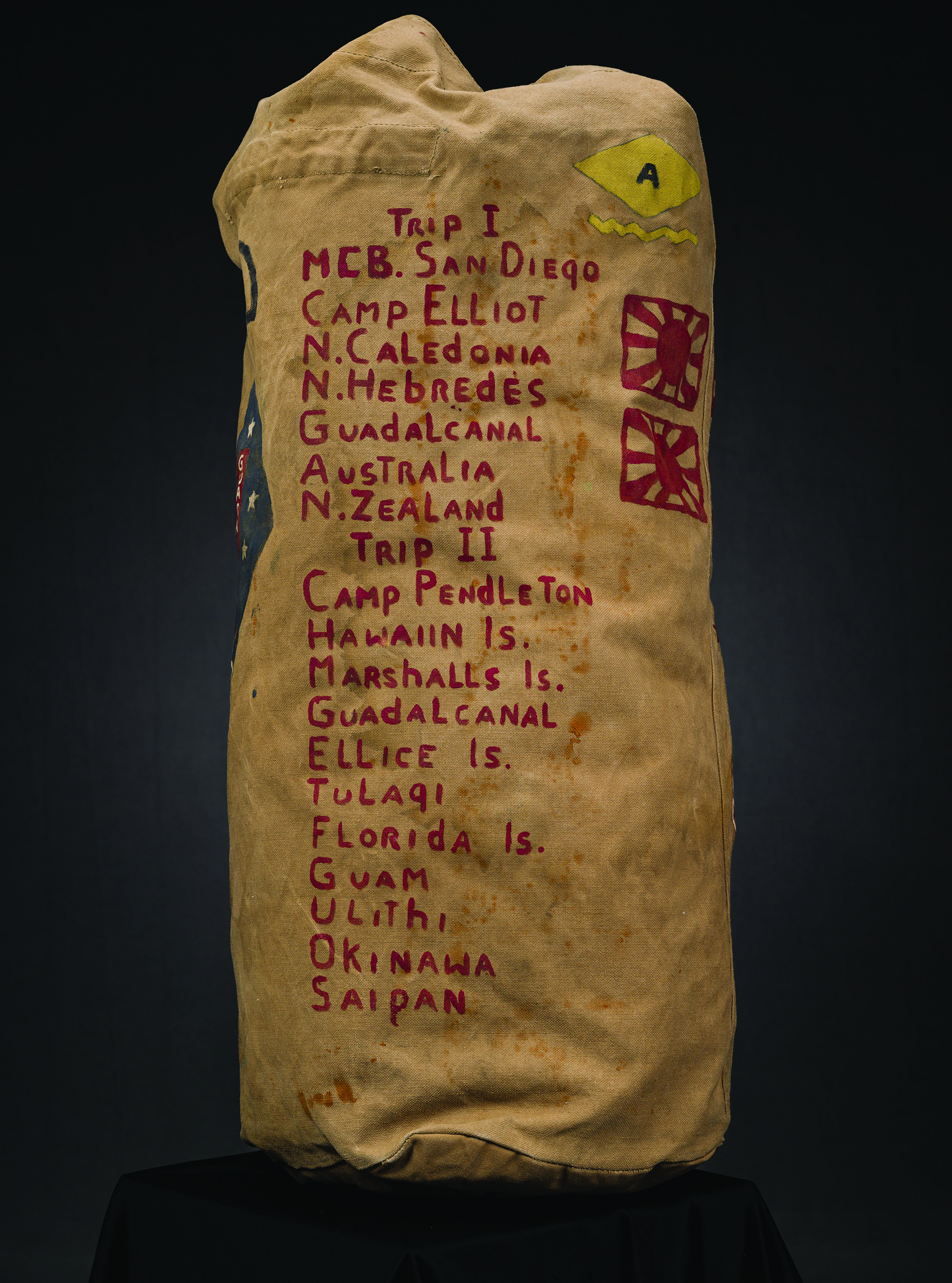

William D. Germain

William D. Germain’s seabag.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

This seabag belonged to Sergeant William D. Germain, who joined the Marine Corps in the summer of 1942. His seabag helps shed light on his journey in the Corps. He traveled quite a bit throughout the Pacific during World War II, and his bag is divided into “Trip I” and “Trip II,” which detail his first and second trips outside of the United States, with a brief interlude between.

Germain’s platoon photograph. He is number 8.

National Museum of the Marine Corps.

Germain’s travels in the Marine Corps.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

Though he enlisted too late to participate in the campaign on Guadalcanal, Germain did travel to the South Pacific with the 2d Replacement Battalion. From the bag, one can see that he attended boot camp at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot at San Diego. He then underwent infantry training at Camp Elliot in San Diego before joining the 2d Replacement Battalion.

Replacement battalions were created in September 1942 to refill Marine units that had suffered from attrition to casualties or reassignment.[3] When Germain went overseas, the concept was brand new. As part of the 2d Replacement Battalion, he went to New Caledonia, New Hebrides (this is misspelled on his bag), and finally Guadalcanal, receiving orders to join Company H, 2d Battalion, 1st Marines, before the Marines were pulled off the island. He then went to Australia and New Zealand before returning to the United States.

Once back in the United States, Germain began “Trip II,” which started with Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton, California, and proceeded to the Hawaiian Islands, the Marshall Islands, Guadalcanal, Ellice Island, Tulagi, Florida Island, Guam, Ulithi, Okinawa, and finally Saipan. During this trip, Germain saw combat in the Marshall Islands and at Guam and Okinawa.

Prior to deploying outside of the United States for the second time, Germain was assigned to the brand-new 1st Armored Amphibian Tractor Battalion, which was activated in August 1943. These units operated the armored versions of the landing vehicle, tracked (LVT) that the Marines were using in their assaults across the Pacific theater. LVTs were originally conceived as amphibious logistics vehicles capable of carrying supplies from ships, through the surf, and up onto land. Marines used them at Guadalcanal in this capacity, but by November 1943, the Marines were using these vehicles to deliver combat Marines over a reef and onto the shore at Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands. The vulnerable, thin-skinned steel vehicles were originally armed with machine guns and provided with extra armor. Later, they saw the addition of a turret with a 37-millimeter tank gun and, after that, a 75-millimeter howitzer. This provided the Marines with a huge boost in firepower on the invasion beaches, through the armored LVTs were not as well-protected as an actual tank. They provided the best supporting fire when in the water, because that gave the Japanese defenders less of an opportunity to hit them.

An LVT(A)-4 makes an appearance on Germain’s seabag, along with the symbol of III Amphibious Corps.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

A turtle with boxing gloves was an unofficial symbol of armored amphibian operators.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

Germain became an armored amphibian tractor crewmember and was assigned to Company A, 1st Armored Amphibian Tractor Battalion. He first saw combat with that unit at Roi-Namur in the Marshall Islands in January–February 1944. His next assault was during the Battle of Guam in July–August 1944. He operated an LVT(A)-1 armed with a 37-millimeter gun on a turret during those operations.[4]

A group of

A group of

LVT(A)-4s make an assault on Okinawa.

Marine Corps History Division.

Germain participated in the Battle of Okinawa in April–June 1945, landing in the initial assault that began on 1 April. His battalion had since switched to the more powerfully armed LVT(A)-4, which carried an open top turret with a 75-millimeter howitzer. Germain and his unit left Okinawa on 7 July and returned to Saipan in the Mariana Islands to prepare for the invasion of Japan that thankfully never materialized.[5]

After the war, Germain returned to the United States and was discharged from the Marine Corps. He served in the Marine Corps Reserve during the Korean War, but he spent this time at Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, where he was promoted to sergeant.

Apart from the place names on his bag, Germain also painted the 1st Marine Division patch to honor the division he had served with on Guadalcanal. He also has representations of his armored LVT, along with Japanese flags and a fighting turtle. One of the more important marks on this bag is the Unit Numerical Identification System symbol. In 1944, Marine Corps divisions began using a tactical marking system in which each division had a shape symbol and three numbers that identified what unit a Marine or equipment belonged to. The system was largely unknown until recent years, where a key was uncovered that illustrated the 4th and 5th Marine Division symbols.

Harry H. Allen

It has been said that whoever possesses Iceland holds a pistol firmly pointed at England, America, and Canada.

~ Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill[6]

After Harry H. Allen’s trip to Iceland, he received the Bronze Star with V device for heroism on Saipan in 1944, landed on Iwo Jima in 1945, and was at the Battle of Chosin Reservoir in 1950.

Marine Corps History Division.

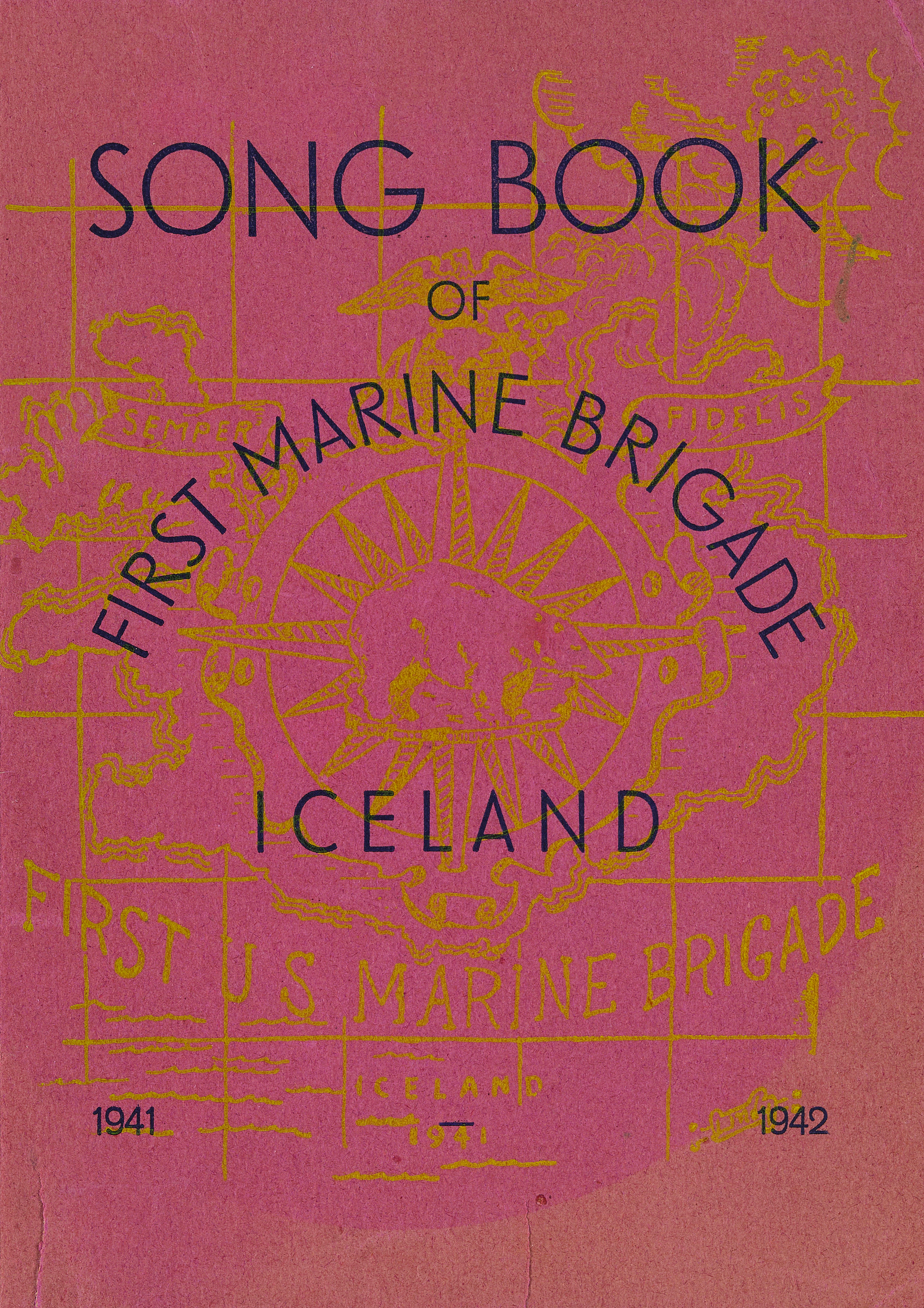

Harry H. Allen’s seabag, representing his time with the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

This seabag differs from some of the others in this collection in that it does not serve as a travel diary. However, this bag is beautifully painted to represent the 1st Marine Provisional Brigade’s deployment to Iceland before the United States officially became embroiled in World War II. The art on the bag is still very crisp, and it is clear that the artist could work at a high level of skill. This bag belonged to Harry H. Allen, who joined the Marine Corps in June 1940 and volunteered for service with the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade.

During the early European conflict in World War II, the United Kingdom had a garrison on Iceland, which Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill believed was a vitally important strategic location. Nazi German forces were then steamrolling Western Europe with their blitzkrieg (lighting war). Iceland shared a king with Denmark. When Denmark was defeated and occupied by Germany in April 1940, Churchill endeavored to rush British troops to the island. By May, British troops were ashore in Iceland, but these were vital troops that the United Kingdom could not afford to lose to occupation duty.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill reviews the Marines on Iceland.

Marine Corps History Division.

Pvt Robert C. Fowler is welcomed by British Gnr Harold Ricardi, July 1941.

Naval History and Heritage Command.

The United States, though not yet involved in the war, did not want to see a Nazi invasion of Iceland. On 16 June 1941, the 1st Marine Brigade (Provisional) was formed in Charleston, South Carolina. Their orders stated: “in Cooperation with the British Garrison, Defend Iceland Against Hostile Attack.” The new brigade, which was mainly composed of the 6th Marine Regiment, the 5th Defense Battalion, and 2d Battalion, 10th Marine Regiment, steamed from the United States on 22 June and arrived in Iceland on 7 July. The British wanted the Marine brigade placed under their command, but since the United States had not entered the war yet, the Americans declined. The British did loan trucks and provided drivers and turned over their permanent camps to the Marines. On 16 August, Churchill reviewed a joint parade and wrote, “There was a long march past in threes, during which the tune ‘United States Marines’ bit so deeply into my memory that I could not get it out of my head.”

The 1st Provisional Marine Brigade wore polar bear patches in Iceland. Marines adopted the patch to match the British Army’s 49th Infantry Division.

National Museum of the Marine Corps.

Allen’s songbook was full of patriotic music, religious songs, and parodies of popular tunes from the United States.

Marine Corps History Division.

Conditions in Iceland were rough. The Marines suffered a harsh winter without adequate cold weather gear. Brutal cold and 100-mile-per-hour winds made even the simplest task, such as going to the mess hall, dangerous. The brigade installed ropes to help the journey and ensure that Marines did not get lost outside and die from exposure. The mountainous, rugged terrain made travel throughout the island difficult. Storms made travel by ships difficult as well. Worse, as the winter wore on, there were fewer hours of daylight each day.

Marines train in the misery of ice and snow in Iceland.

Marine Corps History Division.

In September 1941, U.S. Army units began arriving on the island, and the Marines were soon placed under the command of Major General Charles Bonesteel Jr. The soldiers and Marines prepared for a potential German airborne invasion. Enemy reconnaissance flights became a frequent occurrence.

The Commandant of the Marine Corps, Major General Thomas Holcomb, planned to recall the Marine brigade back from Iceland as quickly as he could, as it was becoming apparent that the Corps would need to focus their war efforts in the Pacific, not Europe. The Marine Corps was beginning to expand and had recently activated the 1st and 2d Marine Divisions, so the Service simply could not afford to have experienced Marines stuck on a small outpost in northern Europe. All they needed were enough trained soldiers to take their places. Though the Marines on Iceland heard rumors that they would be replaced by the fall of 1941, they spent Christmas that year on the island. That same month, as the war kicked off in the Pacific, things became far more dire for the Corps. As the Japanese onslaught carried across the theater, the Marine garrisons on Wake Island and Guam were lost, and the 4th Marines were stranded in the Philippines, their chances looking bleak. The Corps desperately needed the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade back in the United States to strengthen its building efforts.

Allen served in Iceland from October 1941 to March 1942. He went on to have a storied combat career. Though measles kept him from deploying with the newly created 3d Marine Division, he deployed as a wireman with the 4th Marine Division. Though his seabag does not say so, he fought on Kwajalein in the Marshall Islands, Saipan and Tinian in the Mariana Islands, and Iwo Jima in the Volcano Islands. He was awarded a Bronze Star for heroism on Saipan.

This seabag shows how some Marines have true artistic talent. It also illustrates the partnership that the Marines developed with their British allies in Iceland.

William B. Kuhl

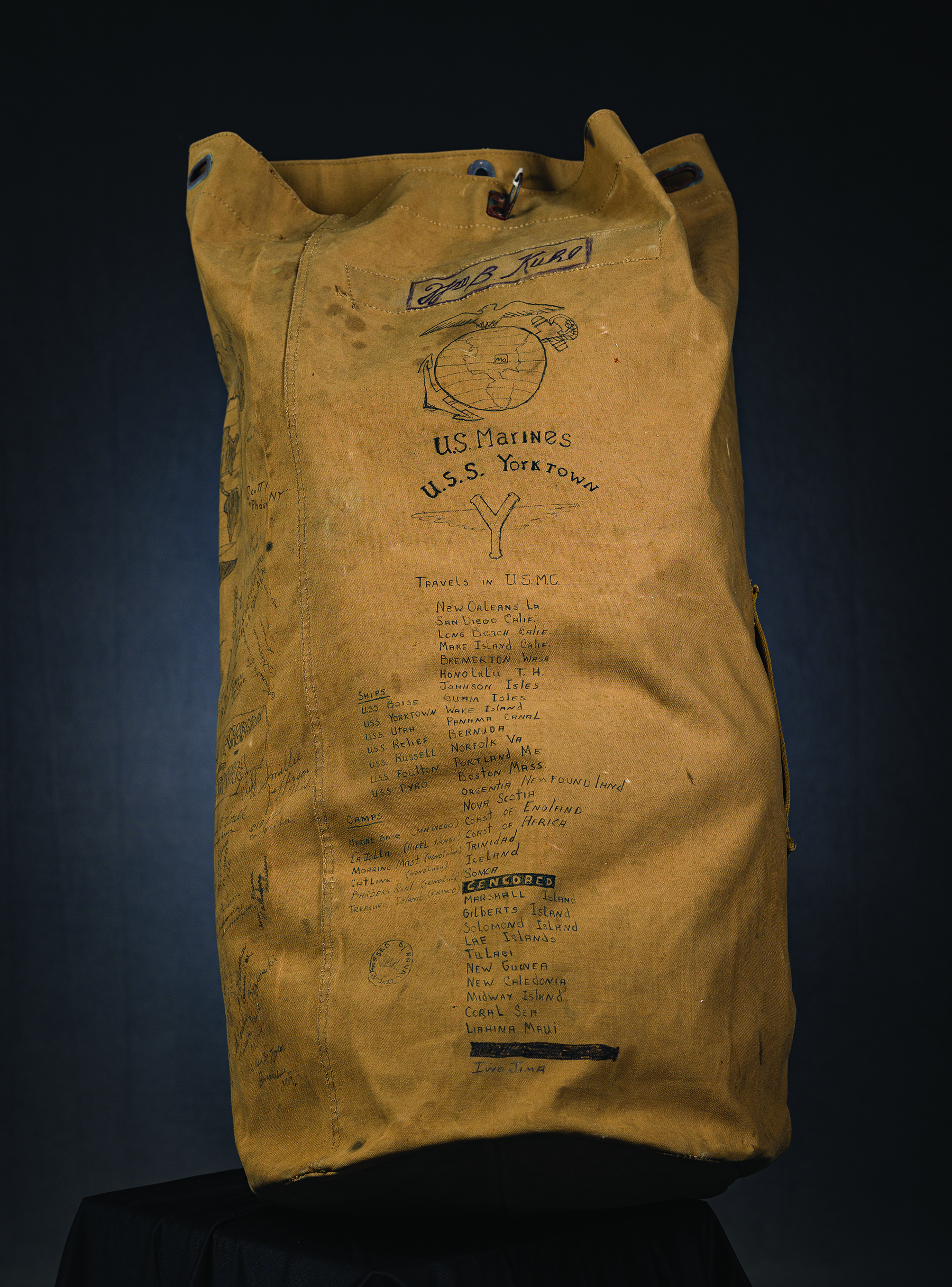

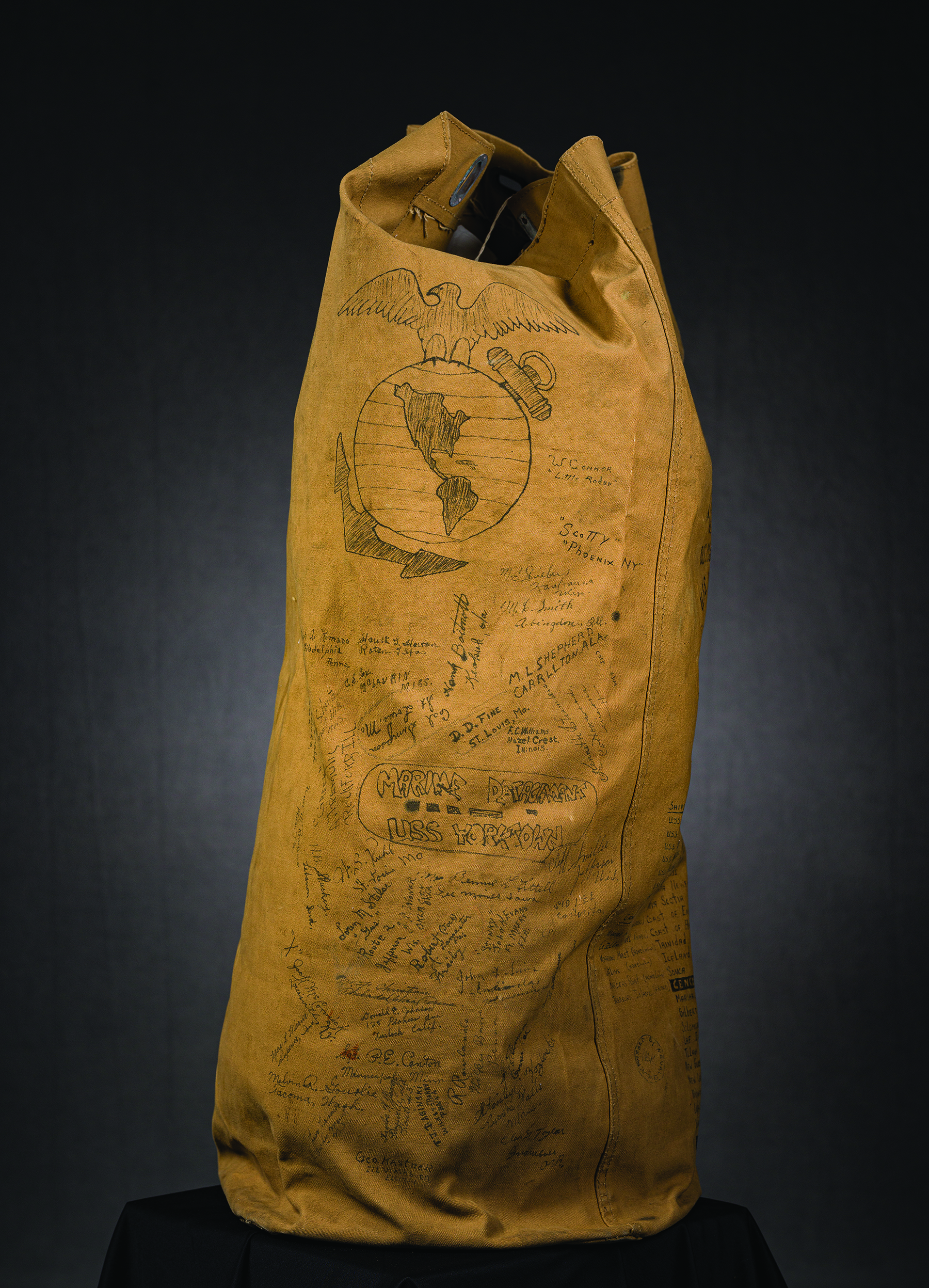

This seabag belonged to Sergeant William B. Kuhl, a Marine who survived the sinking of the aircraft carrier USS Yorktown (CV 5) at the Battle of Midway in June 1942.

William B. Kuhl’s seabag.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

William B. Kuhl standing with his seabag after he was reunited with it.

National Museum of the Marine Corps.

Kuhl joined the Marine Corps in 1940, served until 1946, and then reenlisted during the Korean War. He was assigned to the Marine detachment on the Yorktown. Sea duty was one of the most prestigious posts in the Marine Corps at the time. Like other seabags in this collection, Kuhl’s bag depicts a list of all of the places he visited. In a unique twist, he also asked his fellow Marines on the Yorktown to sign his bag. He also drew an Eagle, Globe, and Anchor with ink, while another one was painted on. At some point before the Battle of Midway, Kuhl lost this seabag.

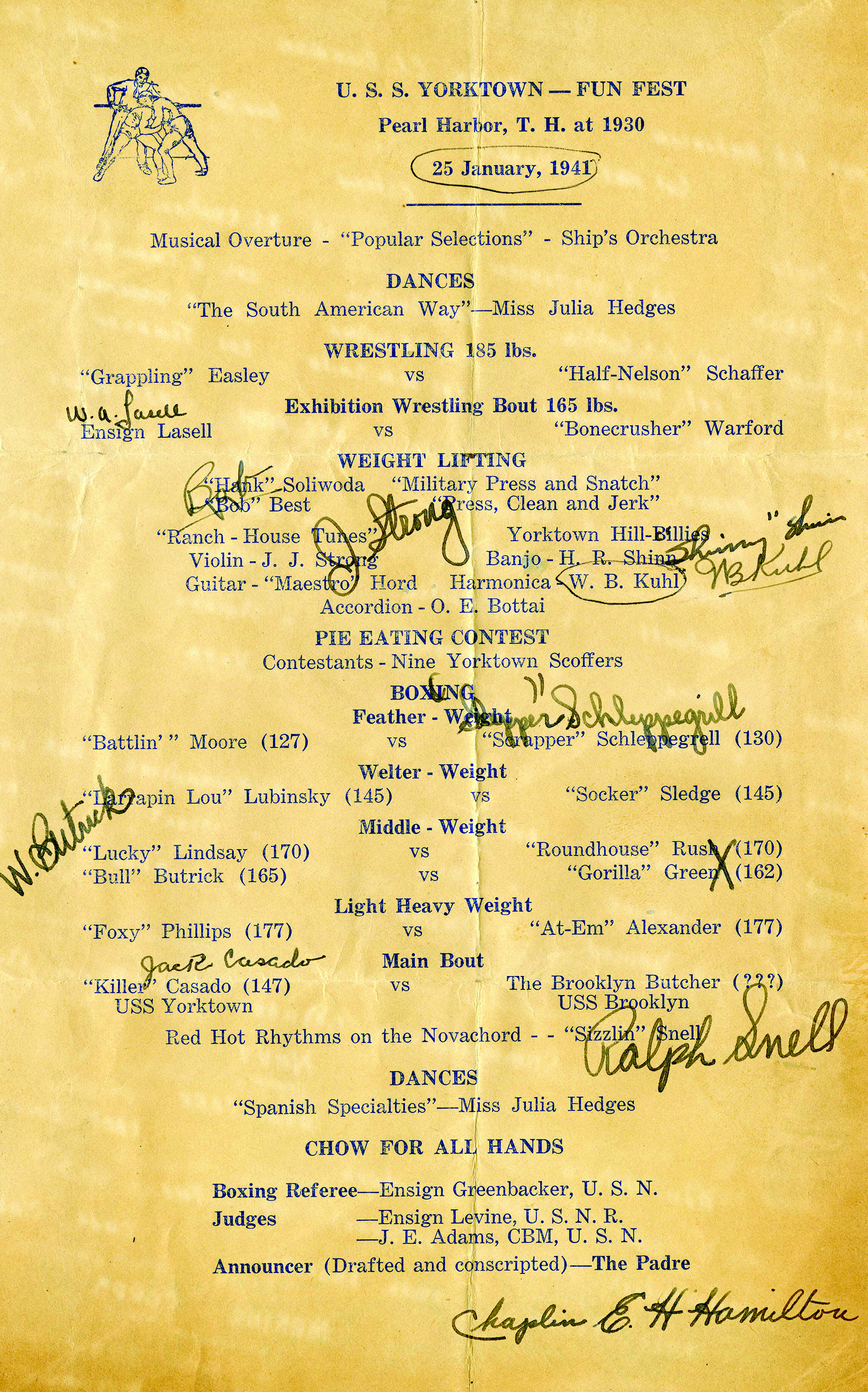

Kuhl played the harmonica in the 1941 Funfest.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

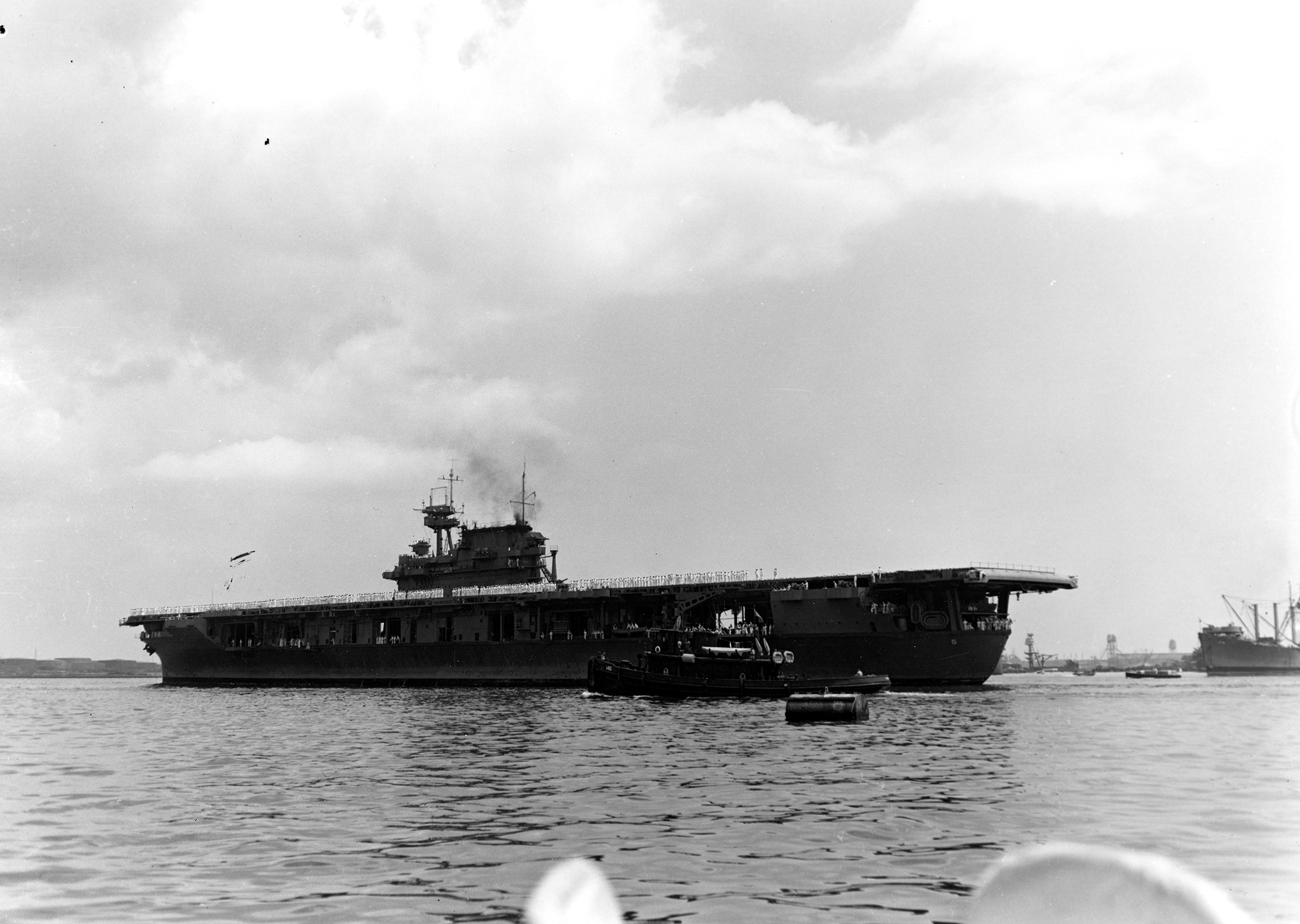

The Yorktown participated in the Battle of Coral Sea on 4–8 May 1942. The carrier suffered major damage in the battle, and the Imperial Japanese Navy believed that they had knocked the ship out of action for some time. However, the Yorktown returned to Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, by the end of the month and was quickly repaired enough to steam to Midway, where the next great battle between the U.S. and Japanese navies was to take place. The patched-up carrier departed Hawaii for Midway on 30 May, just two days after it had returned.

USS Yorktown (CV 5) arrives at Pearl Harbor after the Battle of the Coral Sea. Dockworkers and sailors pulled off a miracle repairing the ship quickly in time for the Battle of Midway.

Naval History and Heritage Command.

Despite putting up a thick barrage of antiaircraft fire, Yorktown was hit by several enemy bombs and torpedoes during the Battle of Midway.

Naval History and Heritage Command.

During the Battle of Midway on 4–7 June, Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers from the Yorktown fatally struck the Japanese aircraft carrier Soryu, one of the four Japanese carriers in the Midway invasion force. Unfortunately for the Yorktown, a flight of Japanese dive bombers found the U.S. carrier and attacked, landing three hits, including one down the ships funnel, which caused severe damage to the ship’s patched-up engine room. Despite the damage, the Yorktown was still capable of making enough speed to launch and recover aircraft due to the superb capabilities of the damage control teams. Later in the day, however, a torpedo attack from Japanese planes doomed the ship. The carrier started to list uncontrollably, and the commanding officer, U.S. Navy captain Elliott Buckmaster, ordered the crew to abandon ship.

Yorktown finally succumbed to its wounds on 7 June 1942.

Naval History and Heritage Command.

The Yorktown did not sink overnight, so sailors began making their way back aboard for repairs and hoped to salvage the ship. However, a Japanese submarine located the carrier and launched a spread of torpedoes, mortally wounding the Yorktown.

When the Yorktown was abandoned, Kuhl was in the water for three and a half hours before being picked up by one of the carrier’s escort ships. Eleven members of the Yorktown’s Marine detachment did not survive the war. Their names are circled on the bag.

Kuhl tracked his service in the Marine Corps on his bag for two more years at sea until he lost it. One of his friends was working at the Service’s Reclamation and Salvage Office and was about to reissue the lost seabag to a new recruit when he recognized it, rescued it, and returned it to Kuhl. Kuhl’s son later donated it to the NMMC.

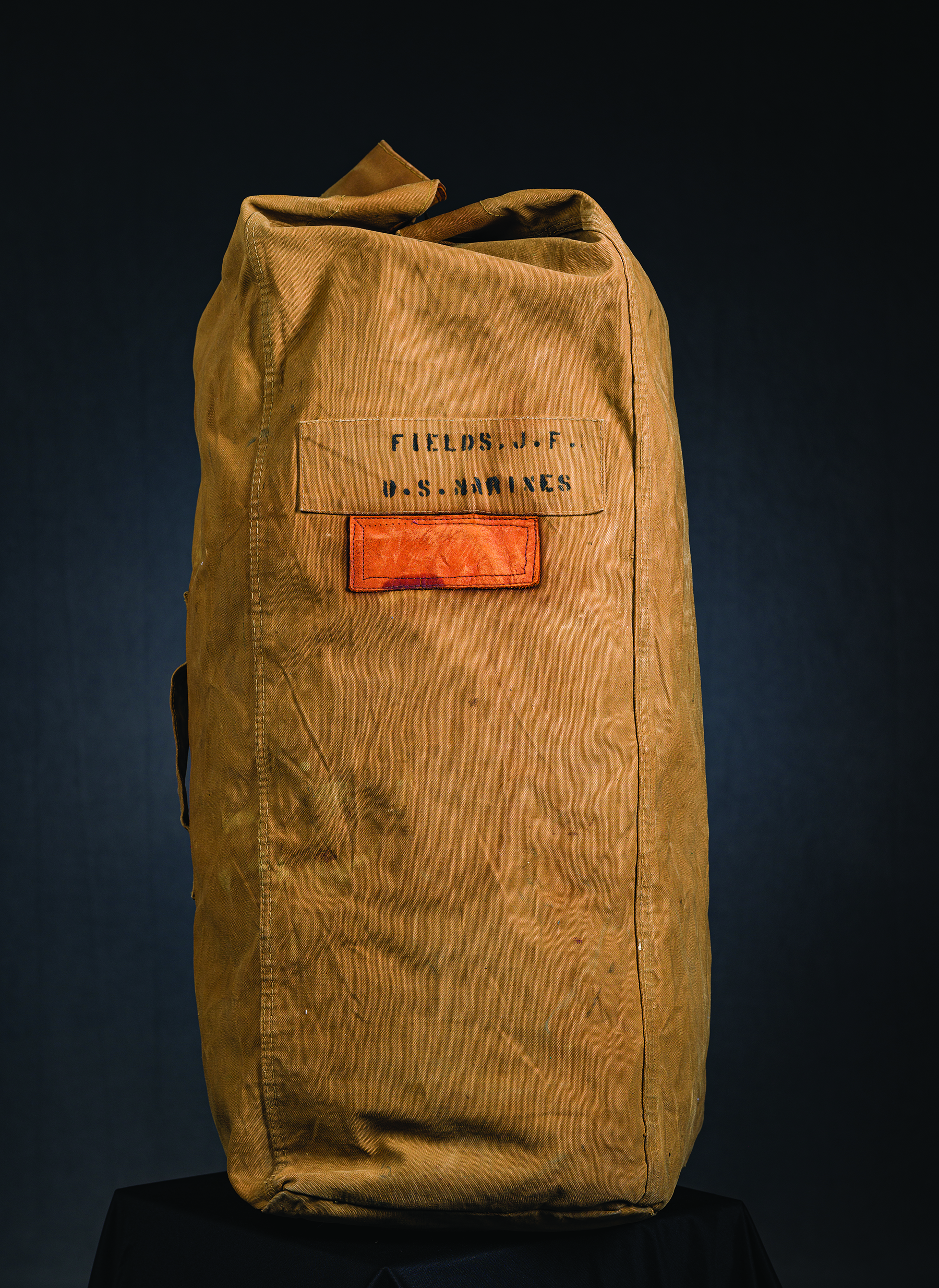

John F. Fields

John F. Fields’s seabag (four sides).

Photos by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

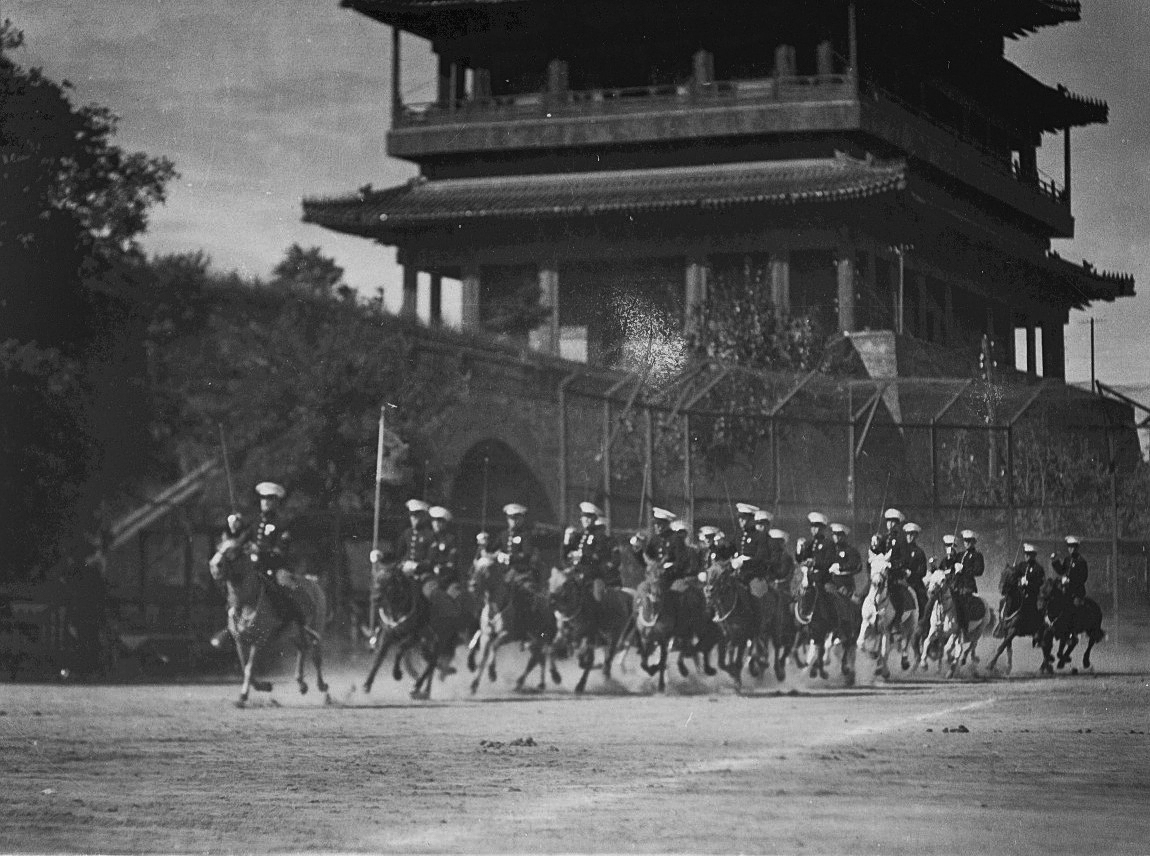

This seabag, the oldest in this exhibit, belonged to John F. Fields. Fields joined the Marine Corps in 1934 and went to radio operator’s school following boot camp. He spent time at the Marine barracks on Guam; then ended up in the Embassy Guard Detachment in Peiping (Beijing), China; and then transferred to the 6th Marines when they were in Shanghai in 1938 so that he could travel back to San Diego with the unit. He fell ill at some point and stayed at the U.S. Naval Hospital in San Diego until his eventual medical discharge in 1939.

Fields was stationed in Peking (Beijing) directly outside the Chienmien Gate.

Marine Corps History Division.

Fields transferred to the 6th Marines when the regiment arrived in Shanghai to reinforce the 4th Marines after the Second Sino-Japanese war began.

Marine Corps History Division.

This seabag has one of the better Eagle, Globe, and Anchor displays of the NMMC’s collection. It also features the placenames of Mexico, Hawaii, Wake Island, Guam, Hong Kong, China, and Cavite written on it. Had Field remained in the Marine Corps in some of these places, he likely would have been on the losing end of the Japanese offensive in the Pacific in 1941–42. Hawaii, Peiping, Wake Island, Guam, and the Philippines were some of the first places hit in the Pacific theater of World War II, with most of the Allied contingents at the latter four having the misfortune of becoming casualties or prisoners of war in some of the most grueling conditions imaginable.

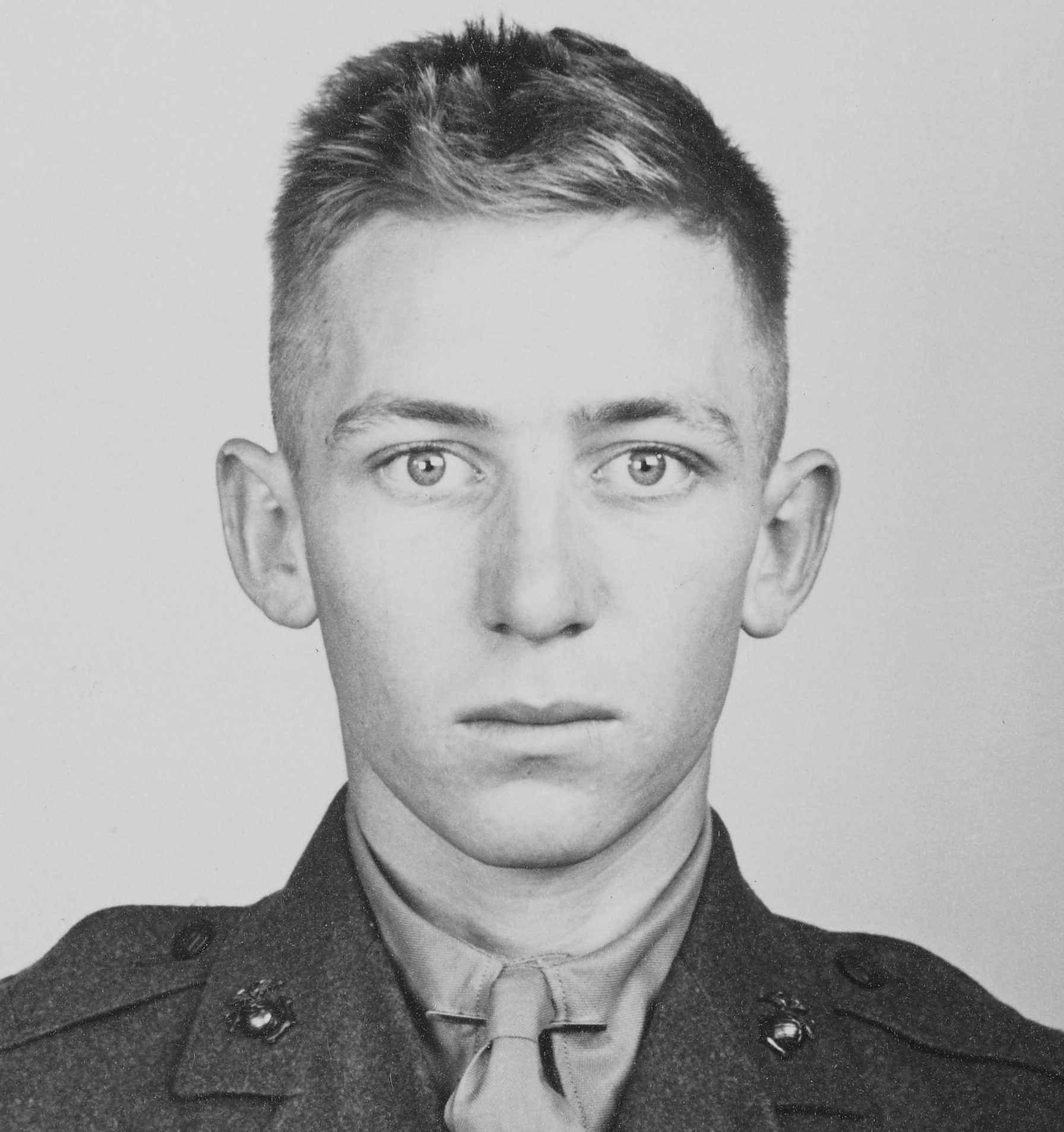

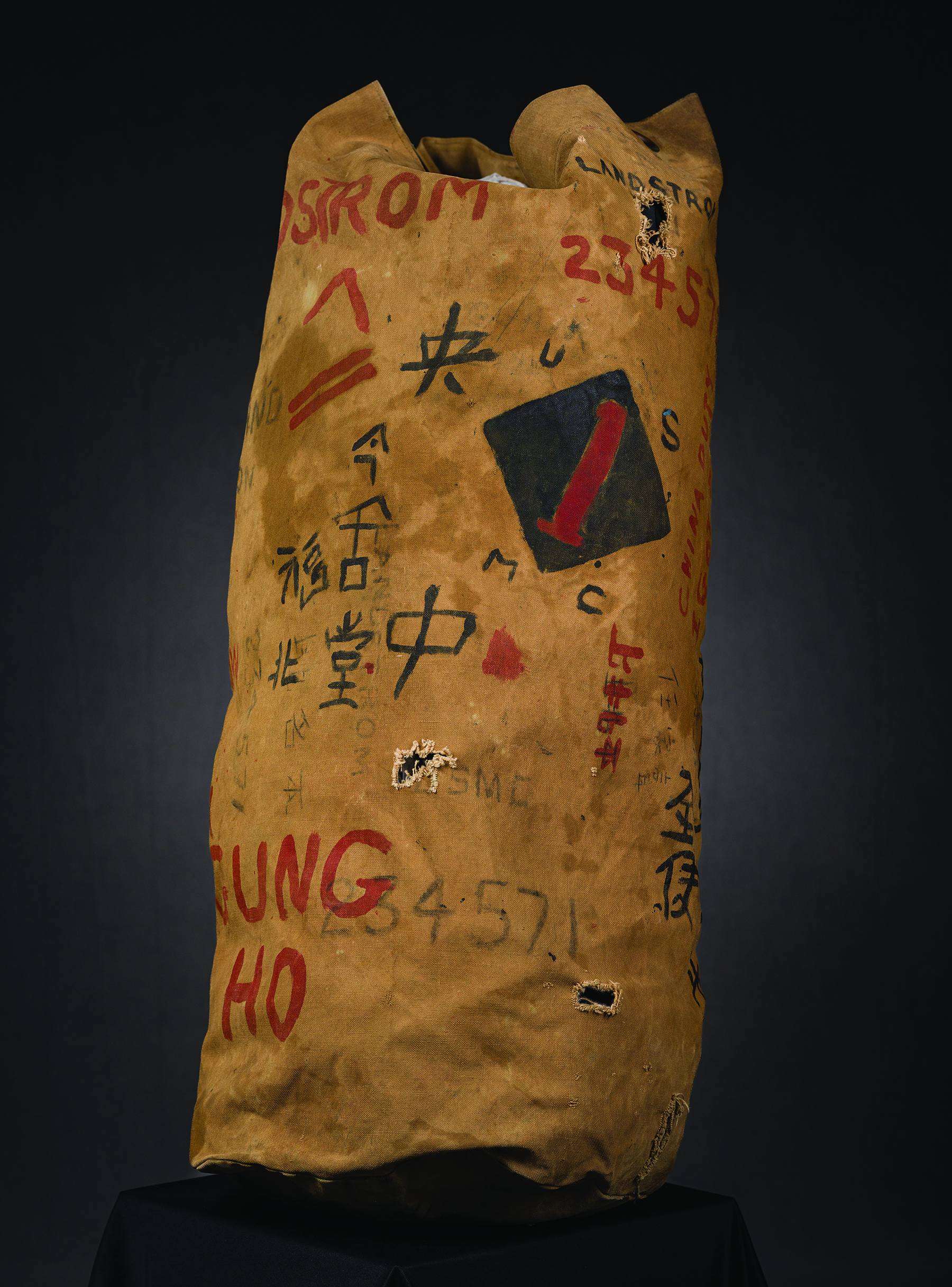

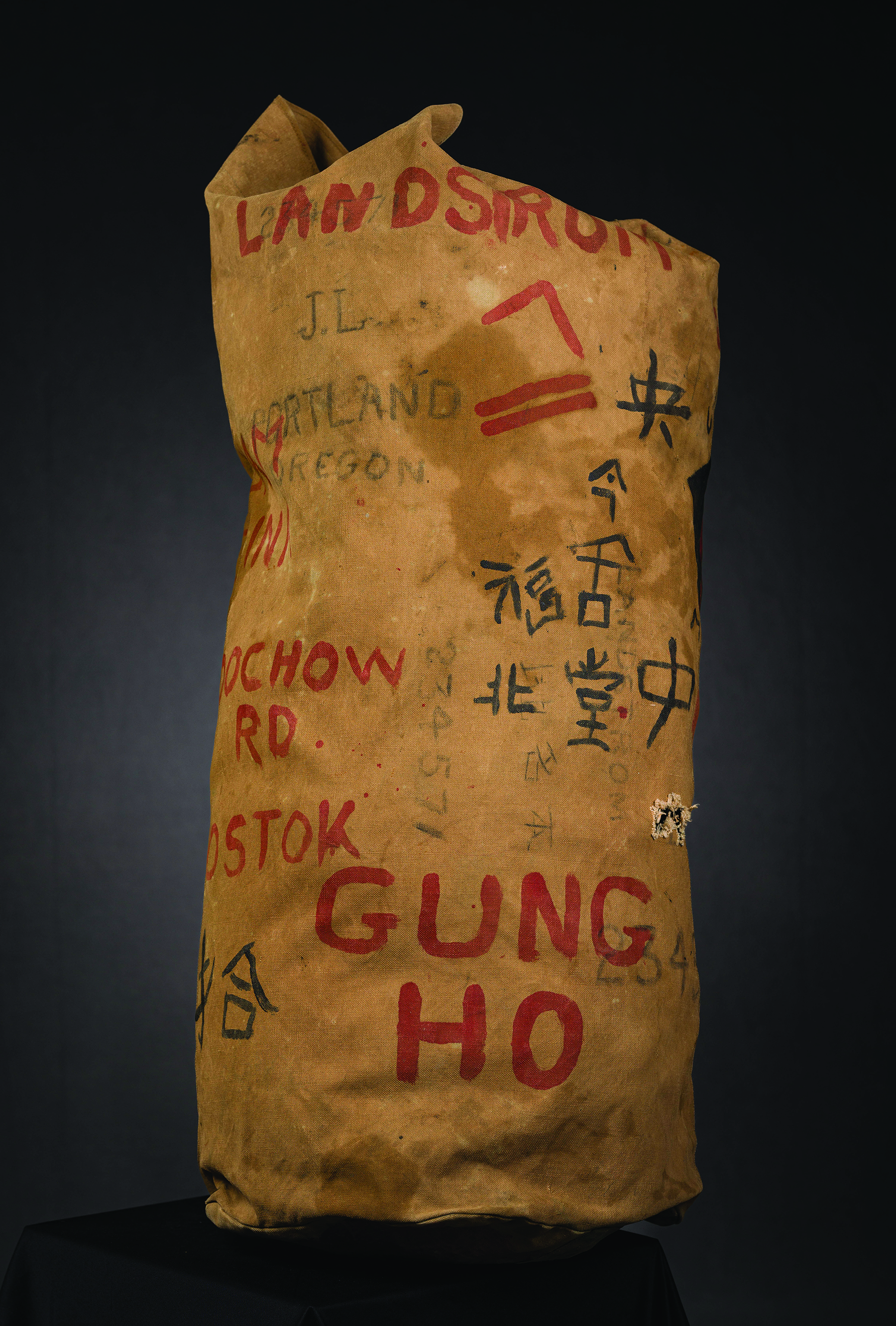

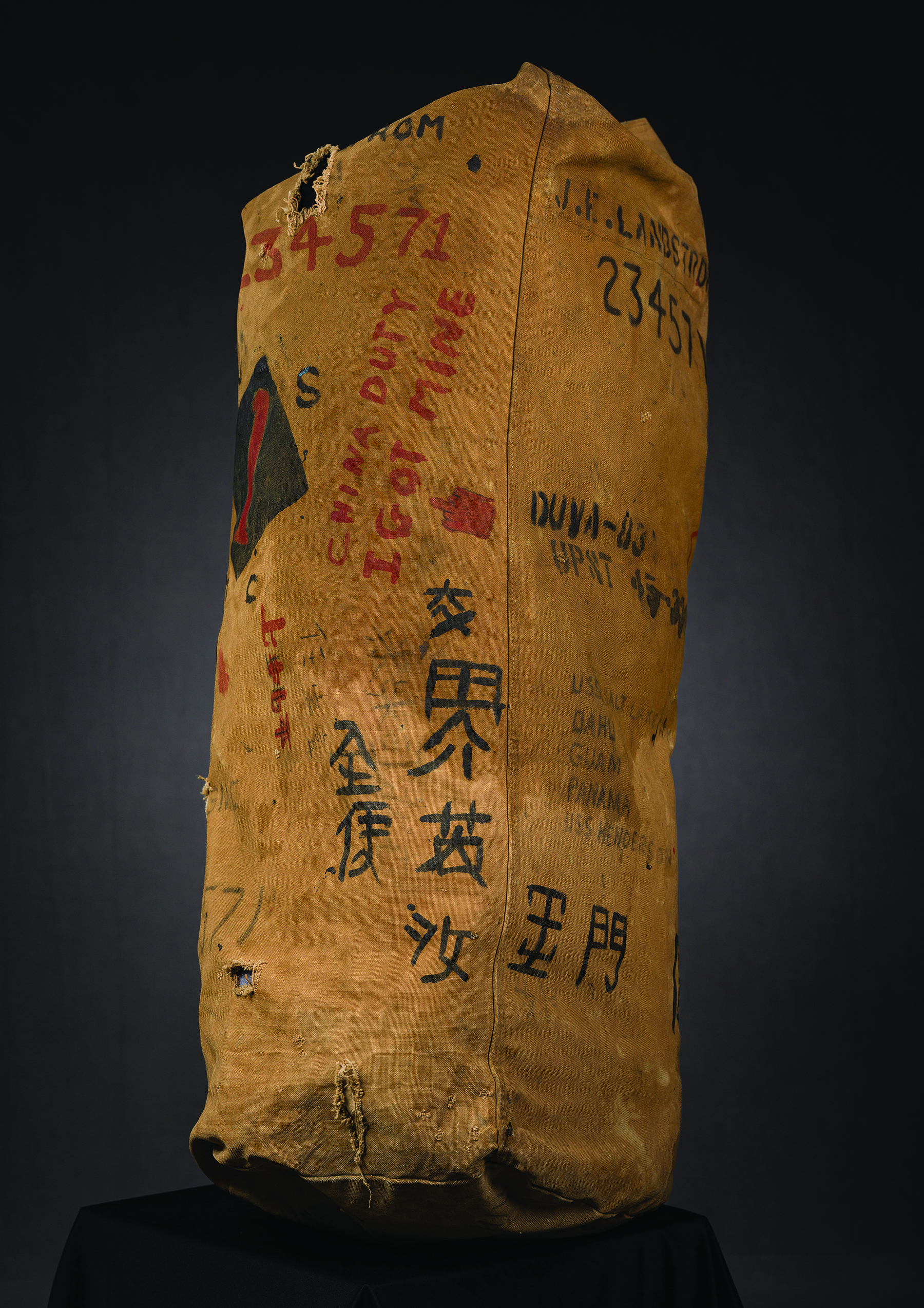

John E. Landstom

Landstrom was not the best artist, but he had a great time decorating his bag, including a rude gesture on the side (three sides).

Photos by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

John E. Landstom’s seabag is the least artistic in this collection. In many ways, it exhibits the jocular nature of a Marine private out on deployment. The bag bears the statement: “China Duty: I got Mine,” complete with a crude drawing of a hand performing an obscene gesture. It also has numerous poorly drawn Chinese characters as well as a crudely painted 1st Marine Division patch.

John E. Lanstrom during his second tour in the Marine Corps.

National Museum of the Marine Corps.

Landstrom had an interesting military career. He joined the Oregon National Guard in April 1929 when he was only 16. He served for three years, and then the day after his discharge he joined the Marine Corps. He served in the Corps from April 1932 to March 1936, spending time with different detachments. After that, he worked for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. He reenlisted in the Marine Corps in 1945, and had to attend boot camp a second time, this time as a 32-year-old. He graduated boot camp in July, reported to Camp Pendleton for advanced training, and became an amphibian tractor crewmember. He was in Tientsin at the end of the war for duty in North China.

A large surrender ceremony in Tientsin, China, in October 1945. Marines had surrendered to the Japanese in the city on 8 December 1941.

Marine Corps History Division.

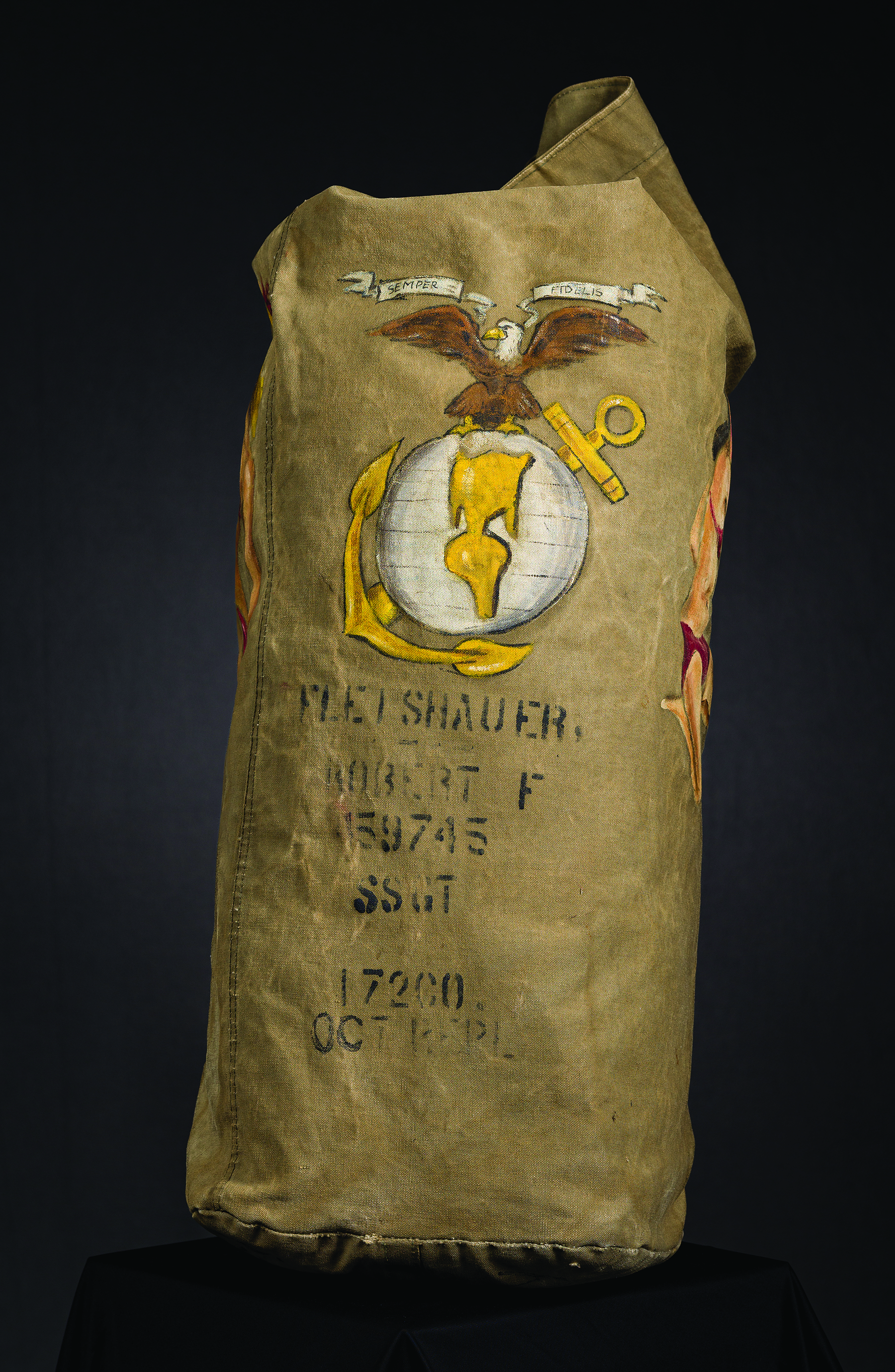

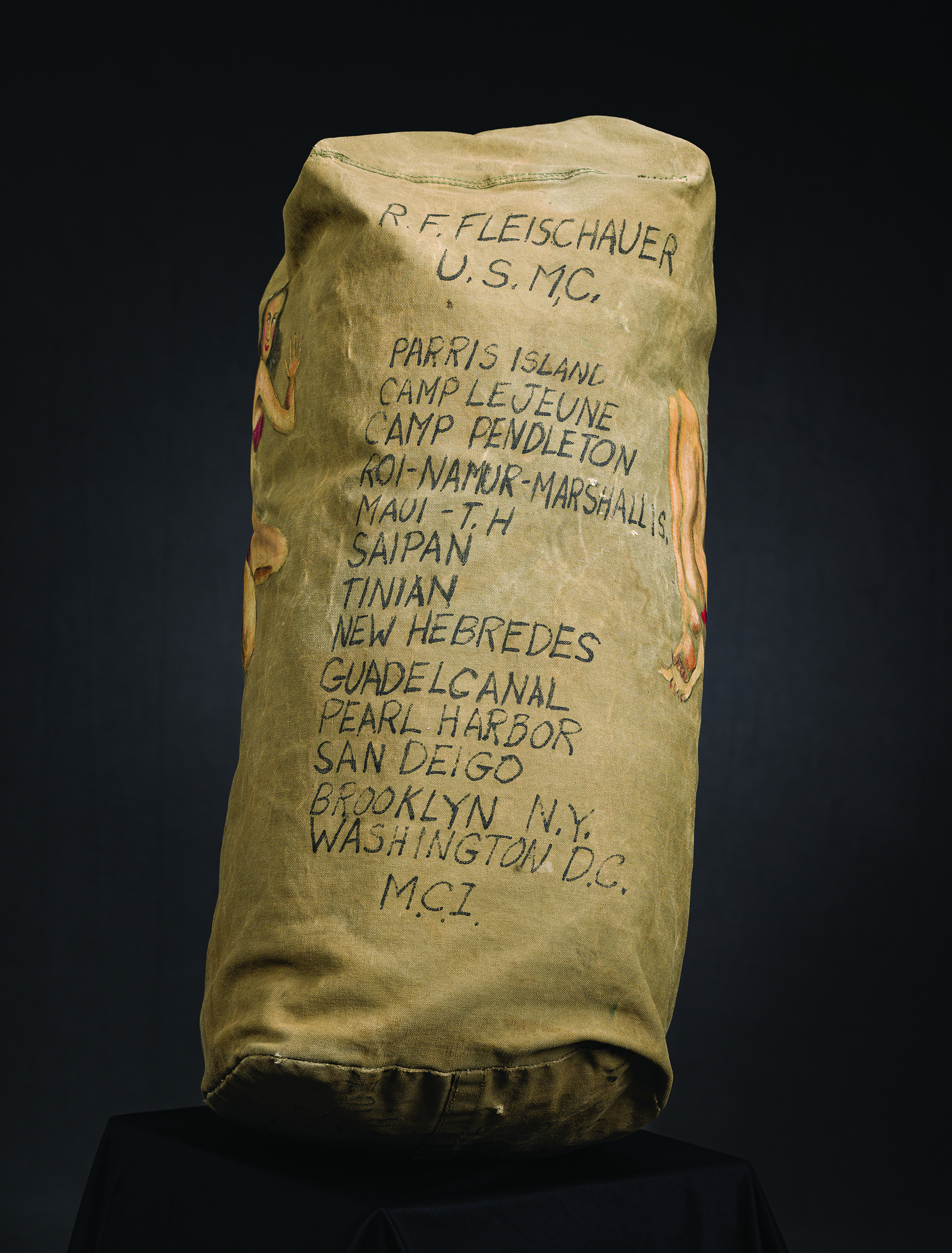

Robert F. Fleischer

Fleischauer, a talented artist, decorated his seabag with pinup girls (four sides).

Photos by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

Fleischauer decorated his seabag and documented his tour (two sides).

Photos by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

Robert F. Fleischer painted this seabag, which is the most risqué of the collection. In addition to a list of all the places that Fleischauer traveled, the bag features not one but two pinup girls.

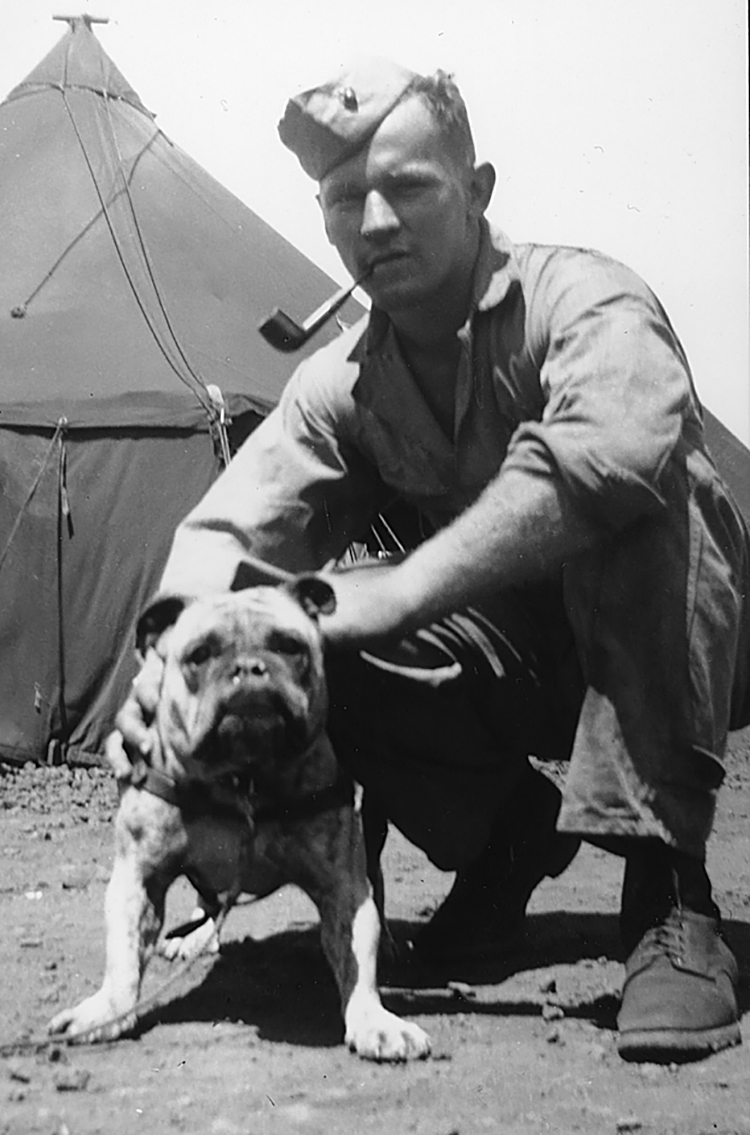

Robert F. Fleischauer and his dog, “Devil Dog,” on Maui after the battle of Roi-Namur.

Leatherneck 83, no. 10 (October 2000): 15.

Originally from New Britain, Connecticut, Fleischauer joined the Marine Corps in 1942, immediately after graduating high school. He was assigned to 1st Battalion, 24th Marines, with whom he landed at the island of Roi-Namur during the invasion of the Marshall Islands in January–February 1943. After the battle, his unit went to Maui to prepare for their next operation. While on the island, Fleischauer was inspired to get a tattoo of an Eagle, Globe, and Anchor. Sadly, the eagle carried a ribbon with the misspelling of “Semper Fidles.”

Fleischauer next participated in the landings at Saipan and Tinian in the Mariana Islands in June–August 1944. He received a minor wound on Saipan and was badly wounded on Tinian, leading to his evacuation from the island. A grenade fragment tore a chunk from his misspelled tattoo.

Fleischauer returned to the United States and was discharged from the Marine Corps in 1946. After attending art school, he rejoined the Marine Corps as an art instructor for the Marine Corps Institute. He then served in Korea during the Korean War. After his return, he was assigned to Leatherneck magazine and later became art director for the Marine Corps Gazette. He retired from the Marine Corps in 1967 as a master sergeant but remained on the Gazette staff until his 1995 retirement. He passed away in 2000.

Fleischauer’s seabag is customized with a list of all the places he was stationed at or visited during his service through his discharge and first reenlistment, including his boot camp stint at Parris Island, combat tours in the Marshall and Mariana Islands, and finally his tour at the Marine Corps Institute. The bag also features a hand painted pinup girl, which is a unique example of the style of bawdy art loved by American servicemembers during this period.

Endnotes

[1] Excerpt from Harry A. Koch, “The Seabag,” Leatherneck 44, no. 10 (October 1961): 87.

[2] Robert Leckie, Helmet for My Pillow (New York: Random House, 1957), 51–52.

[3] Gordon L. Rottman, U.S. Marine Corps World War II Order of Battle: Ground and Air Units in the Pacific War, 1939–1945 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2001), 255.

[4] “Company A, 1st Armored Amphibian Battalion, Fleet Marine Force Pacific, 1–31 July 1944,” Muster Rolls of Officers and Enlisted Men of the U.S. Marine Corps, 1798–1958 (Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA).

[5] “Company A, 1st Armored Amphibian Battalion, Fleet Marine Force Pacific, 1–31 July 1945,” Muster Rolls of Officers and Enlisted Men of the U.S. Marine Corps, 1798–1958 (Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA).

[6] Winston S. Churchill, The Grand Alliance (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1950), 138.