Chapter 5

The Baggage of War

A China Marine’s Valet Bag

By Kater Miller, Curator

Featured artifact: Painted Leather Bag (2007.90.1)

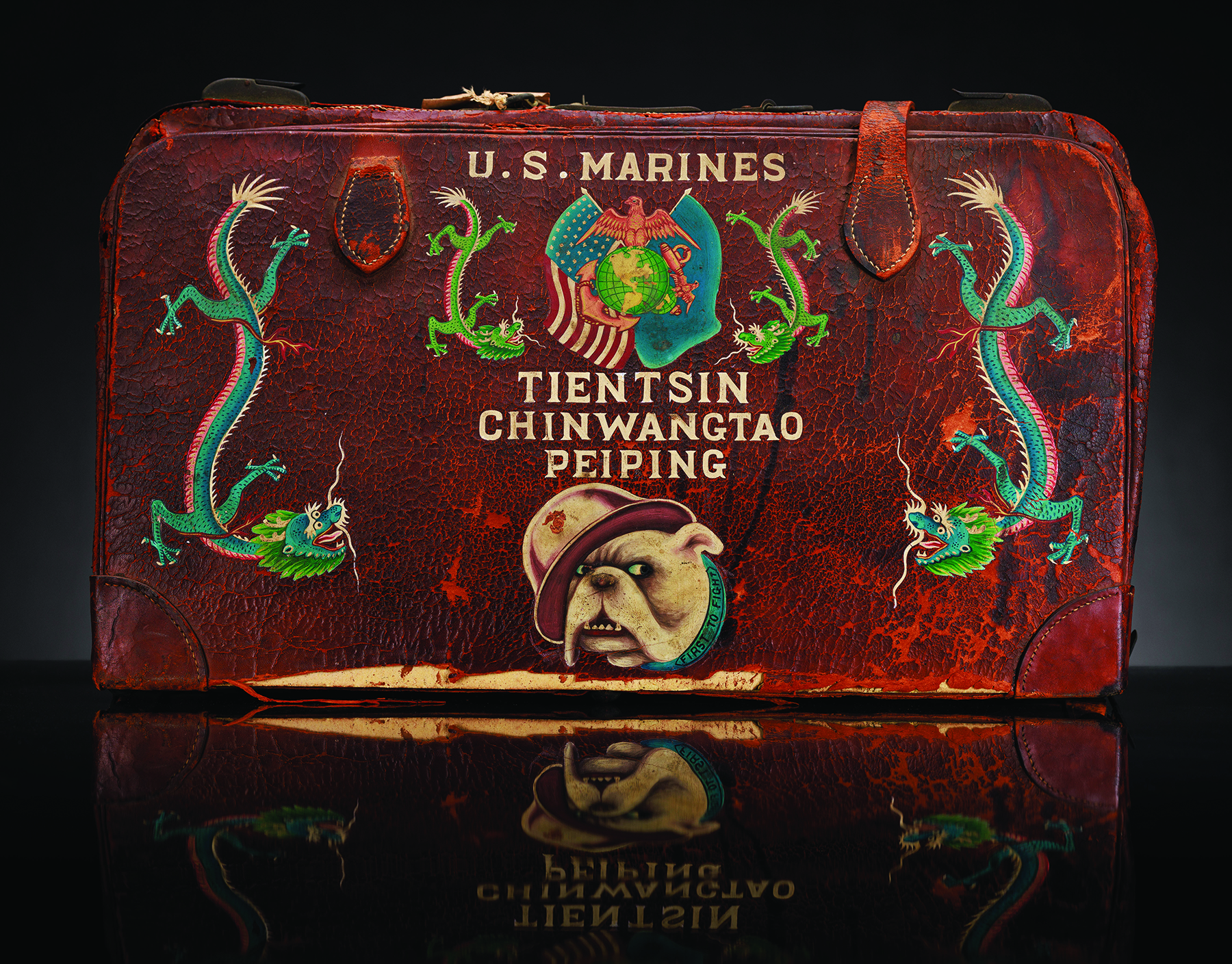

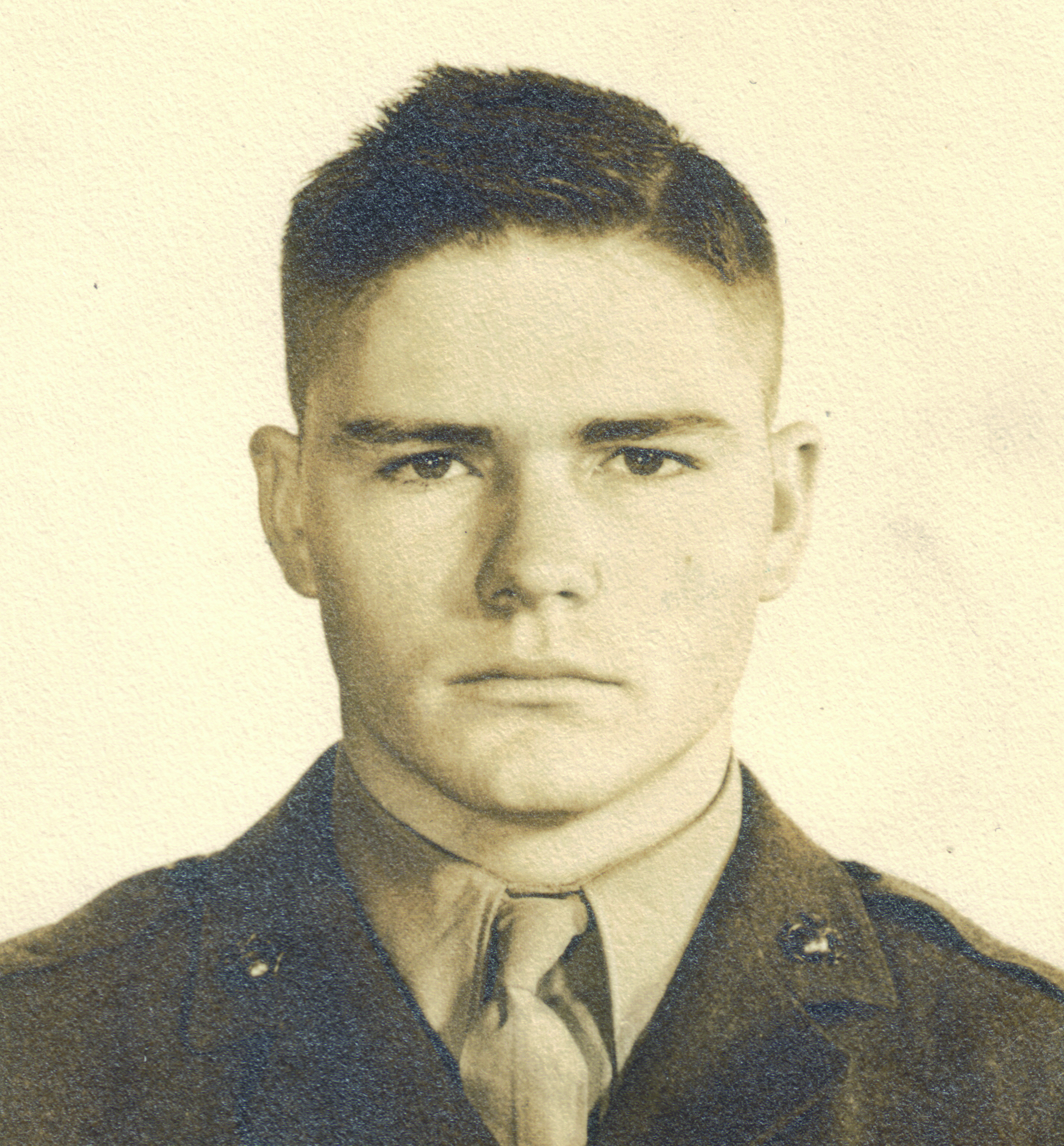

The bag below belonged to Mathew H. Stohlman, a China Marine. He was born in Louisville, Nebraska, in 1917 and graduated from Louisville High School in 1936 before joining the U.S. Marine Corps in 1939.[1] He completed recruit training (boot camp) at Marine Corps Base, San Diego, California. After training to become a radio operator, he was assigned to Tientsin, China, as a high-speed radio operator. He traveled to China on the U.S. Navy transport USS Henderson (AP 1), steaming on 23 March 1940.[2]

Pvt Mathew H. Stohlman’s valet bag.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

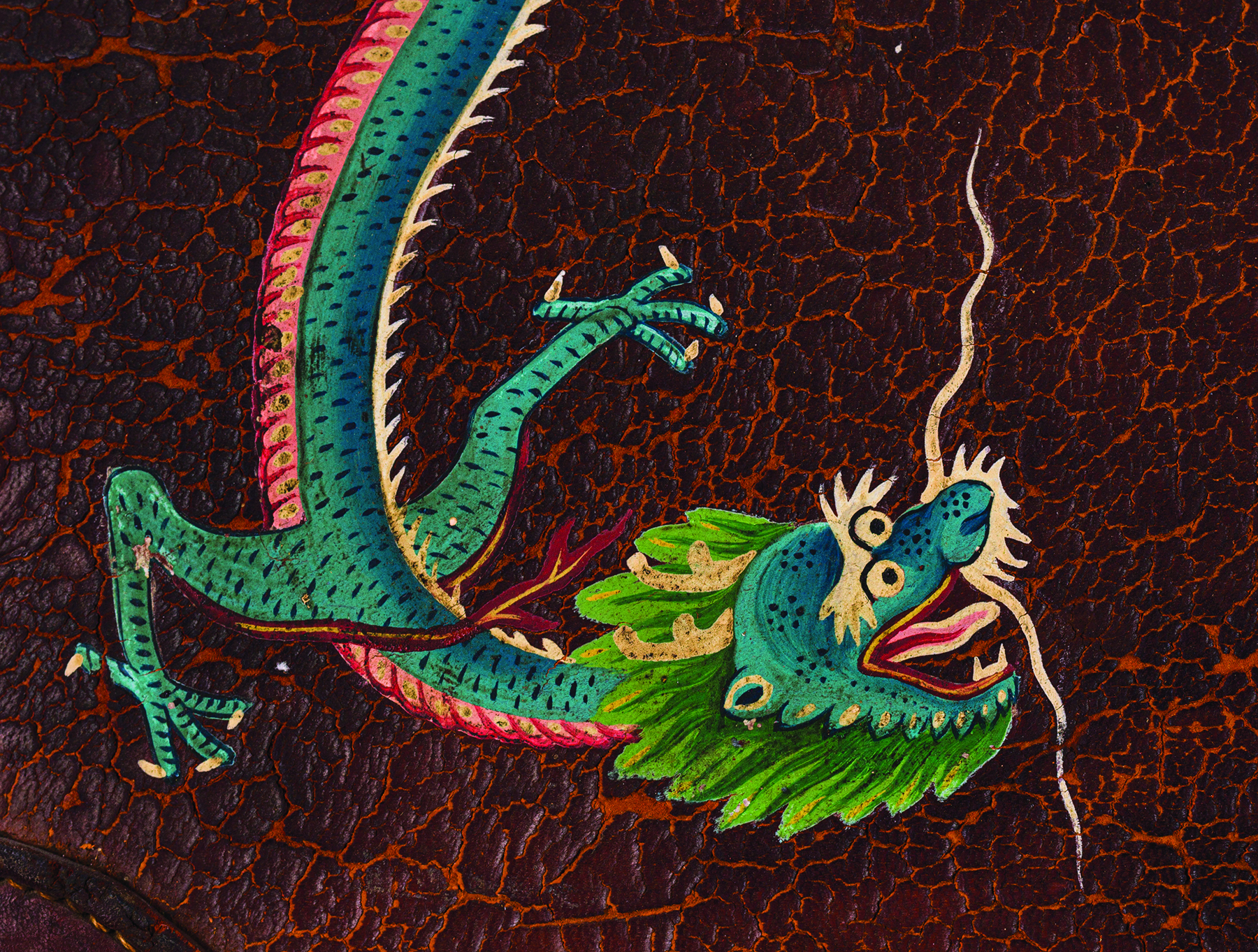

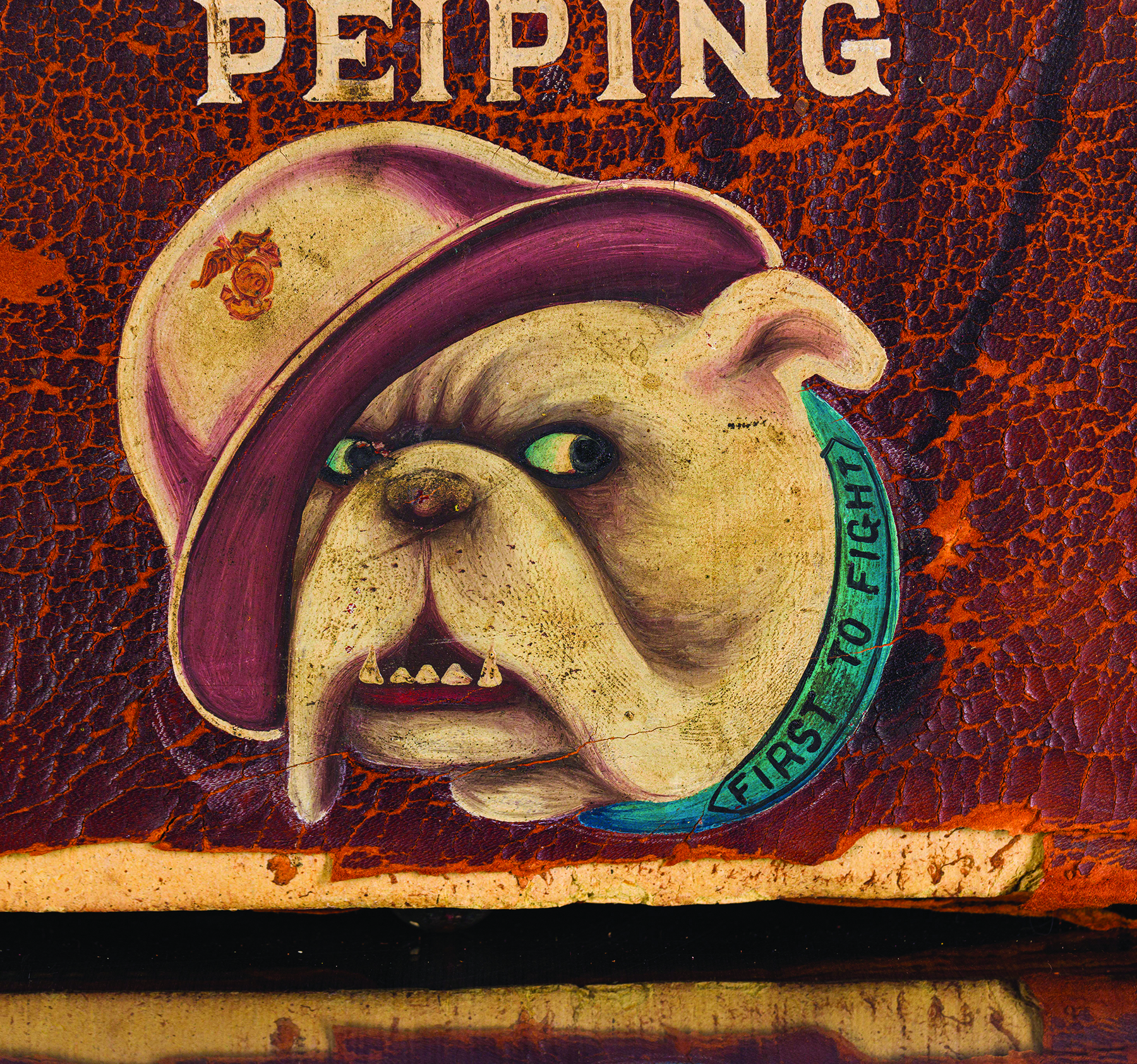

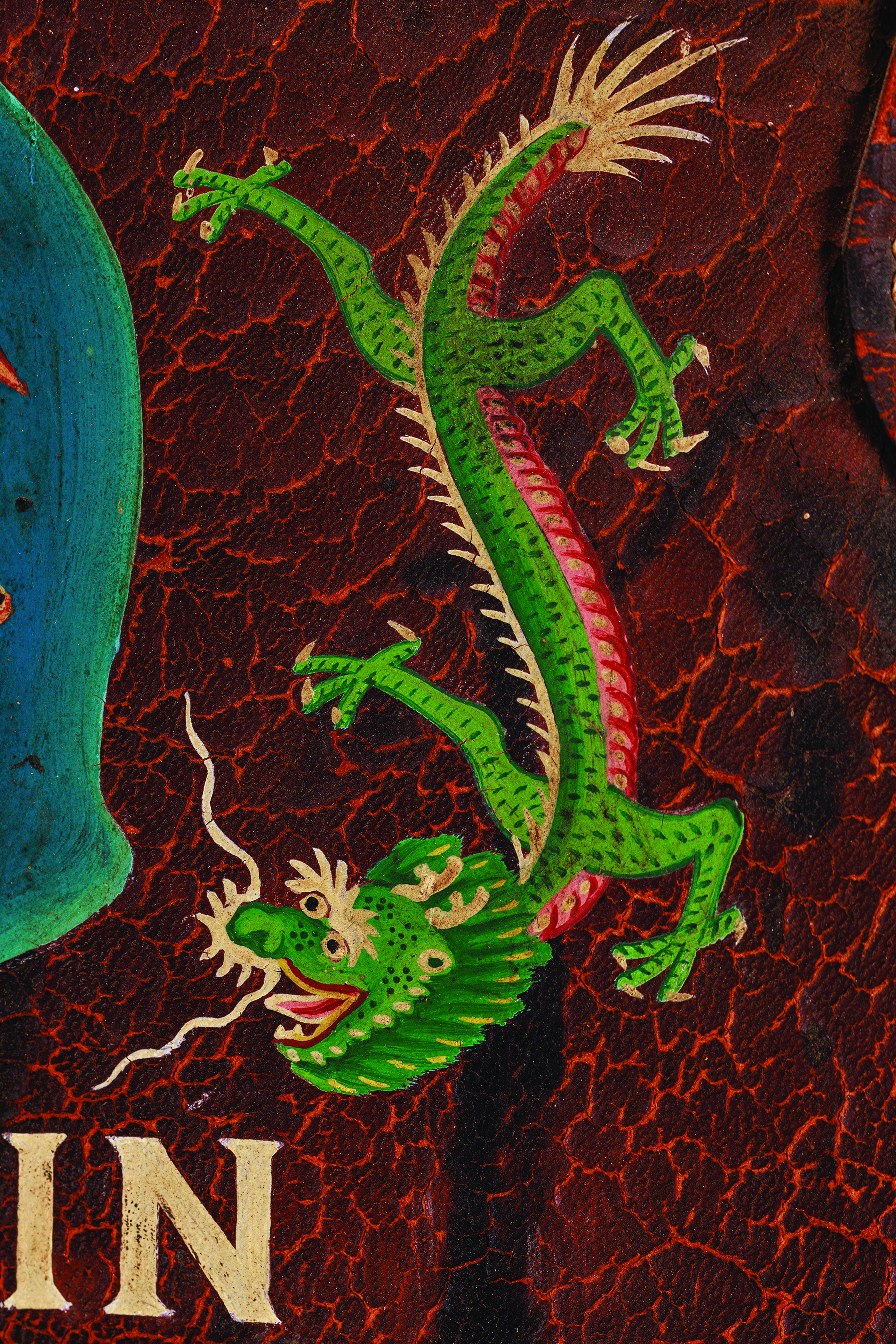

A close-up of the bag’s paint.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

Stohlman arrived in China as a massive drawdown of Marines stationed there had begun. The Marines had first arrived as legation guards during the Boxer Rebellion at the turn of the century and had been stationed in Peking (Beijing) as part of the legation guard since 1905.[3] During the early part of a near-civil war in China in the 1920s, the 4th Marine Regiment arrived in Shanghai to protect American interests in the International Settlement of the city. The U.S. Army’s 15th Infantry Regiment arrived in Tientsin in 1912 and remained there until it was removed and sent to Fort Lewis, Washington, in 1938. Detachments of Marines were also stationed in Tientsin (Tianjin) and Chingwangtao (Qinhuangdao).

Marines watch the Chapei District burning from across the Soochow Creek.

Naval History and Heritage Command.

The Marines serving in China were famous throughout the Corps for living a privileged lifestyle. Even privates could afford cleaning and laundry services, rickshaw rides, and cheap goods from the local economy. Marines took advantage of international enclaves within the cities of China, which offered shops, clubs, sports clubs, bars, casinos, and recreation establishments. Marines also had access to cheap tourist trips through the country. Many Marines owned items that were custom made or elaborately embellished.

Despite having luxury at their fingertips, things were not always good for the China Marines. In 1932, Chinese and Japanese military forces clashed in Shanghai in what became known as the “January 28 incident.”[4] The Marines erected barriers on the south side of the Soochow Creek and watched Japanese troops burn the district of Chapei (Zhabei) on the opposite bank. The U.S. Army’s 31st Infantry Regiment, newly arrived from the Philippines, reinforced the Marines’ defense sector.

Many troops and civilians in the International Settlement watched with horror as the battle unfolded. The incident was short lived, lasting from late January to early March, but international relations in China were rapidly deteriorating, and the international community viewed with consternation the hostile stance that the Japanese were taking in mainland Asia.

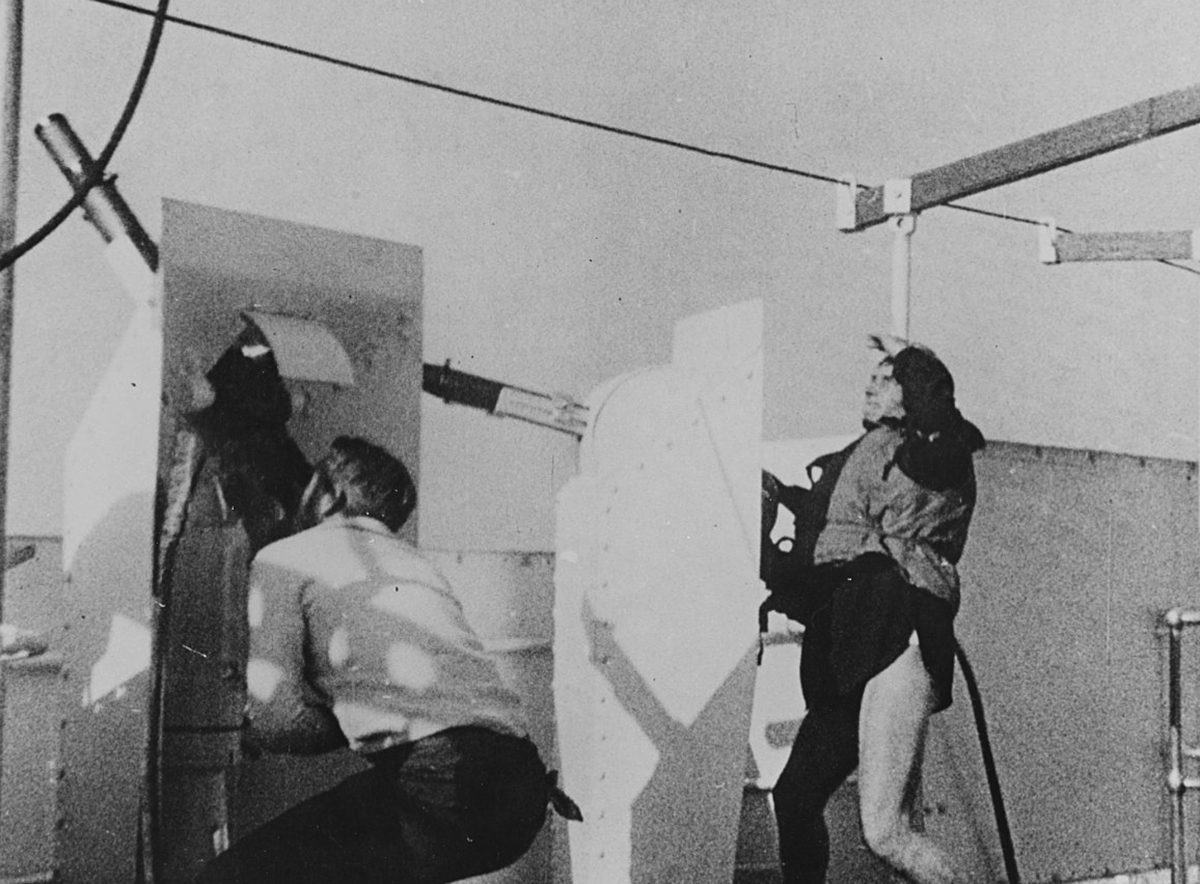

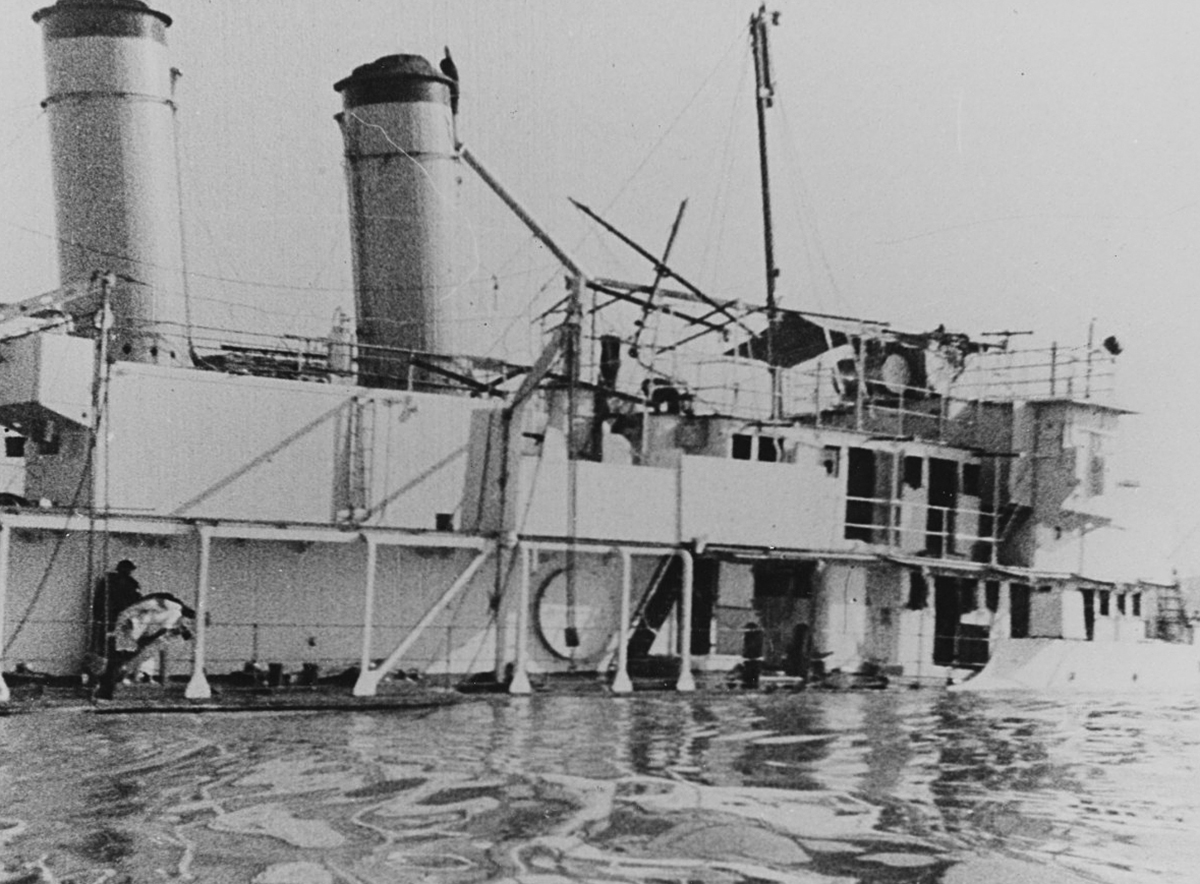

In July 1937, Japan again took an increasingly aggressive posture in China, resulting in another battle between Chinese and Japanese forces known as the Marco Polo Bridge incident. Many historians agree that this event marked the true beginning of World War II. Again, the Marines in the International Settlement watched as war kicked off while they stood by and could do nothing about it. The Marines erected more bunkers as the fighting and chaos spread. The Japanese government used the battle as an excuse to send more soldiers to China. Huangpu River, known in Shanghai as “battleship row,” became filled with Japanese warships. In August, the 2d Marine Brigade, built around the 1st and 2d Battalions of the 6th Marine Regiment, left San Diego to reinforce the 4th Marines in Shanghai. Though the International Settlement remained neutral, this did not stop the Japanese from bombing the U.S. Navy river gunboat USS Panay (PR 5) in December 1937, sinking the gunboat and killing three American sailors.[5] The United States considered a military response before the Japanese government formally apologized and agreed to pay for the destroyed vessel. In February, as the fighting in China cooled off, the 2d Marine Brigade left Shanghai, leaving the 4th Marines once again the sole American unit in the city.

USS Panay (PR 5) defenses.

Naval History and Heritage Command.

USS Panay (PR 5) sunk.

Naval History and Heritage Command.

It quickly became apparent that the world was on the verge of another global conflict. Relations between the governments of the United States and Japan cooled again, and the United States placed embargoes on the resource-poor industrial nation. The 15th Infantry Regiment, stationed in Tientsin, was removed from China and returned to the United States. A small detachment of Marines from the legation guard went to Tientsin and occupied the regiment’s old headquarters building and barracks.

A Japanese tankette during their conquest of Shanghai in 1937.

Naval History and Heritage Command.

Marines standing in formation at their barracks in Tientsin, 1939. The compound had recently been evacuated by the U.S. Army’s 15th Infantry Regiment.

Naval History and Heritage Command.

While Japan continued to increase its military presence in China in the late 1930s, the United States found itself more isolated than ever. In September 1939, Germany invaded Poland, which prompted France and England to declare war on Germany. World War II had officially begun. The British, French, and German soldiers at the International Settlement evacuated so that they could face the new threat in Europe as well as in British possessions such as Singapore and Hong Kong. This left the Marines in Shanghai quite alone.

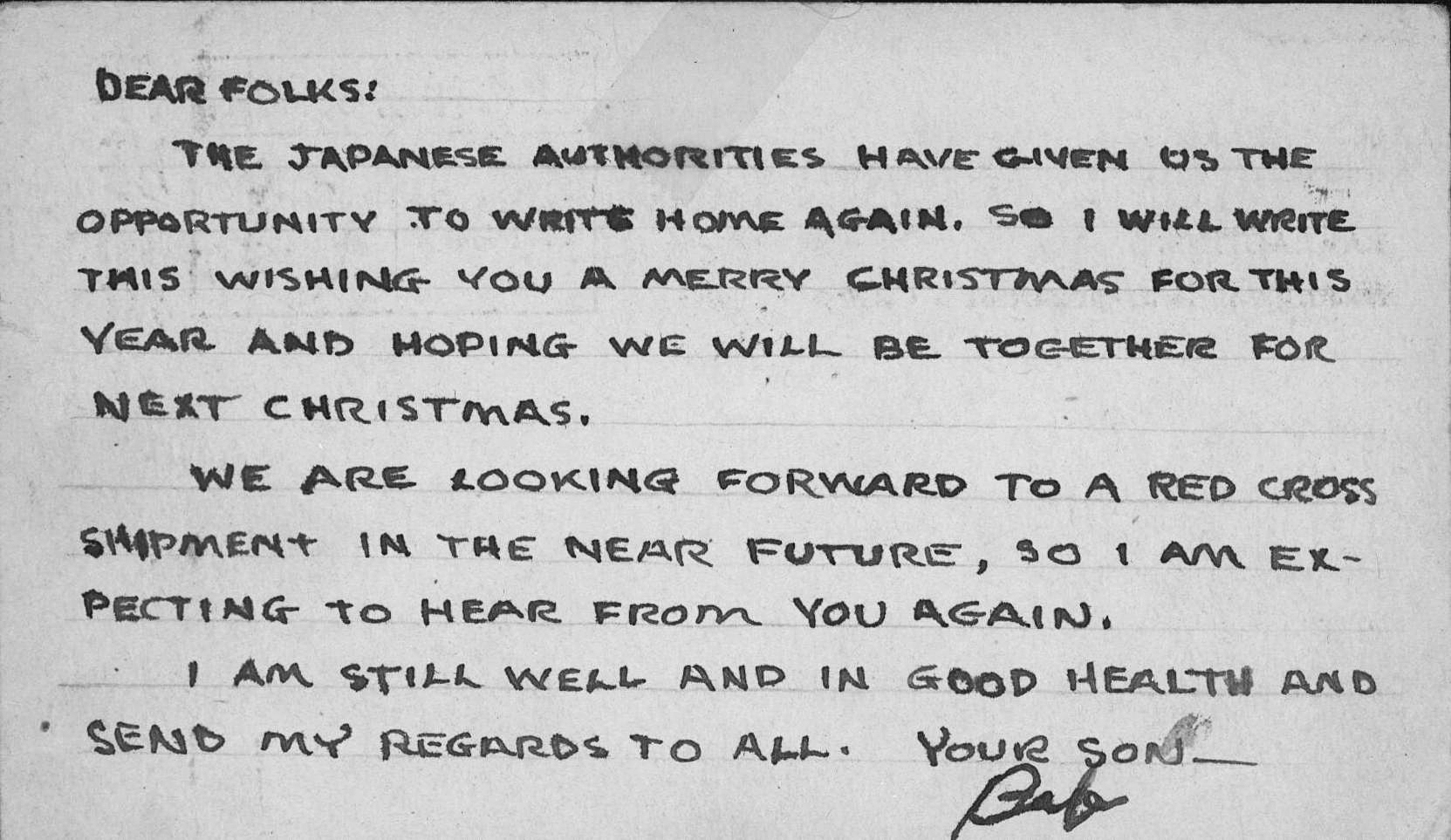

A postcard sent from prisoner of war Robert Murphy to his parents in 1944.

Robert Murphy Collection, Marine Corps History Division.

Mail destined for American prisoners of war in Japan and the Philippines, 1943.

Naval History and Heritage Command.

Stohlman days after arriving at boot camp at Marine Corps Base San Diego, CA, January 1939.

Courtesy of Susan Stohlman Salazar.

Private Mathew H. Stohlman arrived in Tientsin on 4 May 1940. For the next year and a half, until the U.S. entry into the war in December 1941, the Marines still left in China had little international help to rely on. The Marines’ dependents were ordered to leave the country. The commanding officer of the 4th Marines, Colonel Samuel L. Howard, saw the writing on the wall. Through the early autumn of 1941, he petitioned to get his regiment out of Shanghai and station it at the U.S. naval base in Cavite, Philippines, instead. While he waited for an affirmative, he did not replace the Marines who were cycled out of service, so the regiment’s number dwindled. Finally, in late November the order came for the 4th Marines to transfer to the Philippines.

With the 4th Marines gone from Shanghai, there were very few Marines left in China. Only the legation guards and the detachments at Tientsin and Peking, with just more than 200 Marines, remained. They received orders to depart China on 10 December, but this was too late. When the Marines awoke on the morning of 8 December, they suddenly found themselves at war and surrounded by Japanese forces. Japan had attacked the United States at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and was commencing a massive offensive across much of the Asia-Pacific.[6]

The Marines in China were without hope. They were extremely outnumbered, and there was no chance of rescue. Even if they could leave the compound in Tientsin, they were literally surrounded by thousands of Japanese troops who had been at war in China for more than four years. With no other choice, the Marines surrendered to the enemy. They were soon joined by Marines captured at Guam and Wake Island.

Under the terms of their surrender, the Marines’ Japanese captors allowed them to place articles of baggage into storage. They found a Swiss storage company to agree to hold their bags in a warehouse in China for the duration of the war. Stohlman packed his trunk and bag with all the personal items that would fit, including a German camera, photograph albums, custom suits, and brand-new ice skates.[7] The Marines were initially allowed to keep a seabag full of clothing, which they desperately needed for the brutal North China winter that was unfolding.

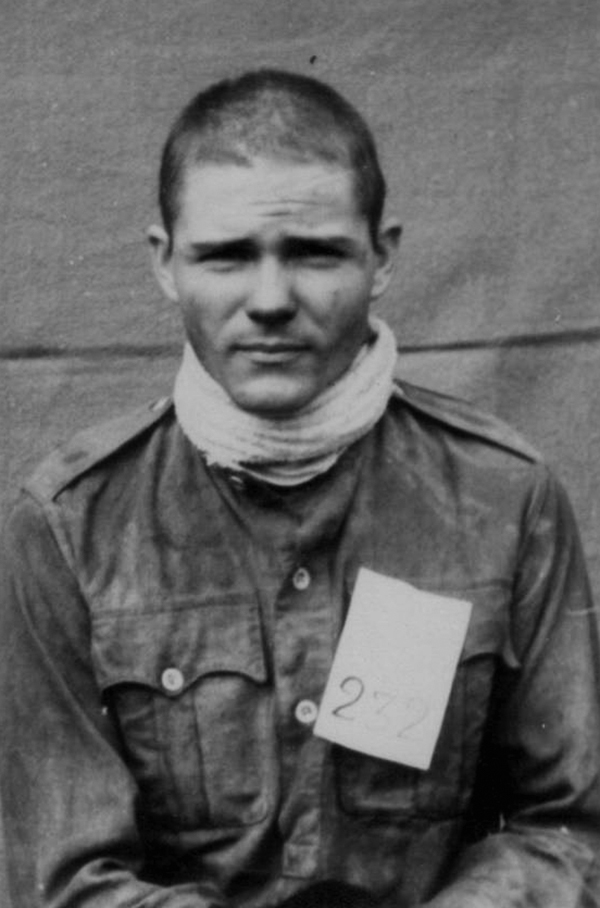

Stohlman on Christmas Day 1943 at Kawasaki Camp 5-D. The rough conditions that he and his fellow prisoners of war endured during their captivity are evident here.

Courtesy of Susan Stohlman Salazar.

Malnourished Allied prisoners of war held in the Aomori Prison Camp near Yokohama, Japan.

Naval History and Heritage Command.

Stohlman’s trunk and bag entered storage while he became a prisoner of war. He was imprisoned in several different camps in China: first Tientsin, then Woosung, and then Kiangwan. Later in the war, he was transferred to a camp in Kawasaki, Japan, and finally to a camp in Niigata. While in captivity, Stohlman was allowed to write letters to his parents, which traveled through the Swiss Red Cross headquarters in Berne, Switzerland, to his home in Nebraska. Because of this circuitous route, letters often took 10 months to make the trip. Stohlman’s first letter does not say much, only that he read from his Bible daily and that he worked on a vegetable farm. The letter had his signature in his handwriting and was proof that he was still alive, the first such proof since December 1941.[8]

On 1 January 1943, Stohlman wrote another letter, which was several paragraphs long. He had been moved to Tokyo and asked his parents for food such as corned beef, butter, and honey, as well as cigarettes and pipe tobacco. He also asked his parents to write the Commandant of the Marine Corps to see if he had been promoted and find out what kind of backpay he would receive once released from captivity. A newspaper article appearing in the Louisville Weekly Courier explained how to send packages to Stohlman, which involved sending them to Switzerland, where they would be transferred on a Swedish ship to Tokyo.[9]

In September 1943, Stohlman wrote another letter from his camp in Kawasaki. This brief letter took six months to arrive in Nebraska. In it, he wrote that he was working every day and was in good health, and he again asked for packages of food to be sent to him. He never received any packages from home. Despite his assurances, a photograph of Stohlman in captivity that was taken roughly around the same time as he wrote his letter shows that he was not in good health and was actually quite malnourished. Chester Biggs Jr., a Marine who wrote of his experiences in the war, mentioned that the Marine prisoners of war were starving from the moment they were captured until the end of hostilities.[10]

In 1944, Stohlman contacted home via an interesting method: a shortwave radio. He sent a message that was relayed to Mrs. W. N. Tappert of Mojave, California, who wrote the local newspaper in Louisville. She could not understand the Marine’s whole name but knew that his first name was Mathew. Through some detective work, the newspaper figured out that it was their local hero and published his message, which again asked for food, candy, and tobacco to be sent to him. He reported that he finally received two Red Cross packages, but no packages had arrived from his parents.[11]

On 19 September 1945, just weeks after Japan’s officials surrender to the United States and its allies, the Evening World-Herald of Omaha, Nebraska, reported that Stohlman had been liberated from his prison camp.[12] He traveled home on the vehicle landing ship USS Ozark (LSV 2) to Terminal Island near Los Angeles, California, and was then moved to the naval hospital in Long Beach, California, for medical treatment. Like all prisoners of the Japanese during the war, Stohlman was sick and malnourished due to nearly four years of starvation and abuse at the hands of his captors. Nearly a quarter of the Allied prisoners interned by the Japanese died in captivity.[13] Fortunately, the China Marines fared better. Of the 204 Marines and sailors captured in North China in 1941, 184 survived their ordeal and came home.[14]

After his discharge from the Marine Corps, Stohlman returned to his home in Nebraska.[15] In 1946, he received a message that one of his bags was in storage in Los Angeles. He had assumed that he would never see it again. When he retrieved the bag, he found that it had been looted of some of his expensive photography equipment and handmade robes that he had acquired for his family before his capture. His expensive ice skates were still inside, much to his delight. According to his daughter Susan Stohlman Salazar, he retrieved the bag, put it on a shelf, and went on with his life.[16]

Details of Stohlman’s painted valet bag.

Photos by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

Ornately decorated and made of leather, this normally expensive bag was something that an enlisted Marine could afford on their meager salary in China. It displays the locations where Stohlman served as well as a beautifully painted dragon. The items that he stored in the bag for the duration of the war, most of which were stolen from him, were also high-quality and something that an enlisted Marine could only afford in China. This bag and Stohlman’s story are a microcosm of the many things the China Marines and their fellow prisoners of war endured at the hands of their Japanese captors. Stohlman survived his captivity, despite abuse and starvation, but many captured soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Marines did not. Mathew Stohlman lived a long life, retiring from the Los Angeles County Flood Control District and passing away on 7 April 2004.[17]

Endnotes

[1] “Obituary,” Journal (Plattsmouth, NE), 22 April 2004, 8.

[2] “Company B, Marine Detachment, Tientsin, China, 1–31 March 1940,” Muster Rolls of Officers and Enlisted Men of the U.S. Marine Corps, 1798–1958 (Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA).

[3] Chester M. Biggs Jr., The United States Marines in North China, 1894–1942 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2003), 136.

[4] Walter Brown, “Japanese Bombard Civilians in Shanghai’s Chapei,” United Press International Archives, 2 February 1932.

[5] Manny T. Koginos, The Panay Incident: Prelude to War (Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Studies, 1967), 28–30.

[6] George B. Clark, Treading Softly: U.S. Marines in China, 1819–1949 (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2001), 123–4. China is across the international date line.

[7] Susan Stohlman Salazar, “Biographical Information for the National Museum of the Marine Corps” (Los Angeles, CA, n.d.).

[8] “Mat Stohlman Writes Parents,” Louisville (NE) Weekly Courier, 8 October 1942.

[9] “Mat Stohlman Writes Again,” Louisville (NE) Weekly Courier, 26 August 1943.

[10] Chester M. Biggs Jr., Behind the Barbed Wire: Memoir of a World War II U.S. Marine Captured in North China in 1941 and Imprisoned

by the Japanese until 1945 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2011), 187.

[11] “Mat Stohlman Writes Again,” Louisville (NE) Weekly Courier, 4 May 1944.

[12] “Omaha with Three Nebraskans Freed,” Evening World-Herald (Omaha, NE), 19 September 1945.

[13] “What Life Was Like for POWs in the Far East during the Second World War,” Imperial War Museum, accessed 31 January 2024.

[14] Biggs, Behind the Barbed Wire, 199.

[15] “Prisoner of Japs Returns Home,” Louisville (NE) Weekly Courier, 22 November 1945.

[16] Susan Stohlman Salazar, “Biographical Information for the National Museum of the Marine Corps” (Los Angeles, CA, n.d.).

[17] “Obituary,” Journal (Plattsmouth, NE), 22 April 2004, 8.