Chapter 27

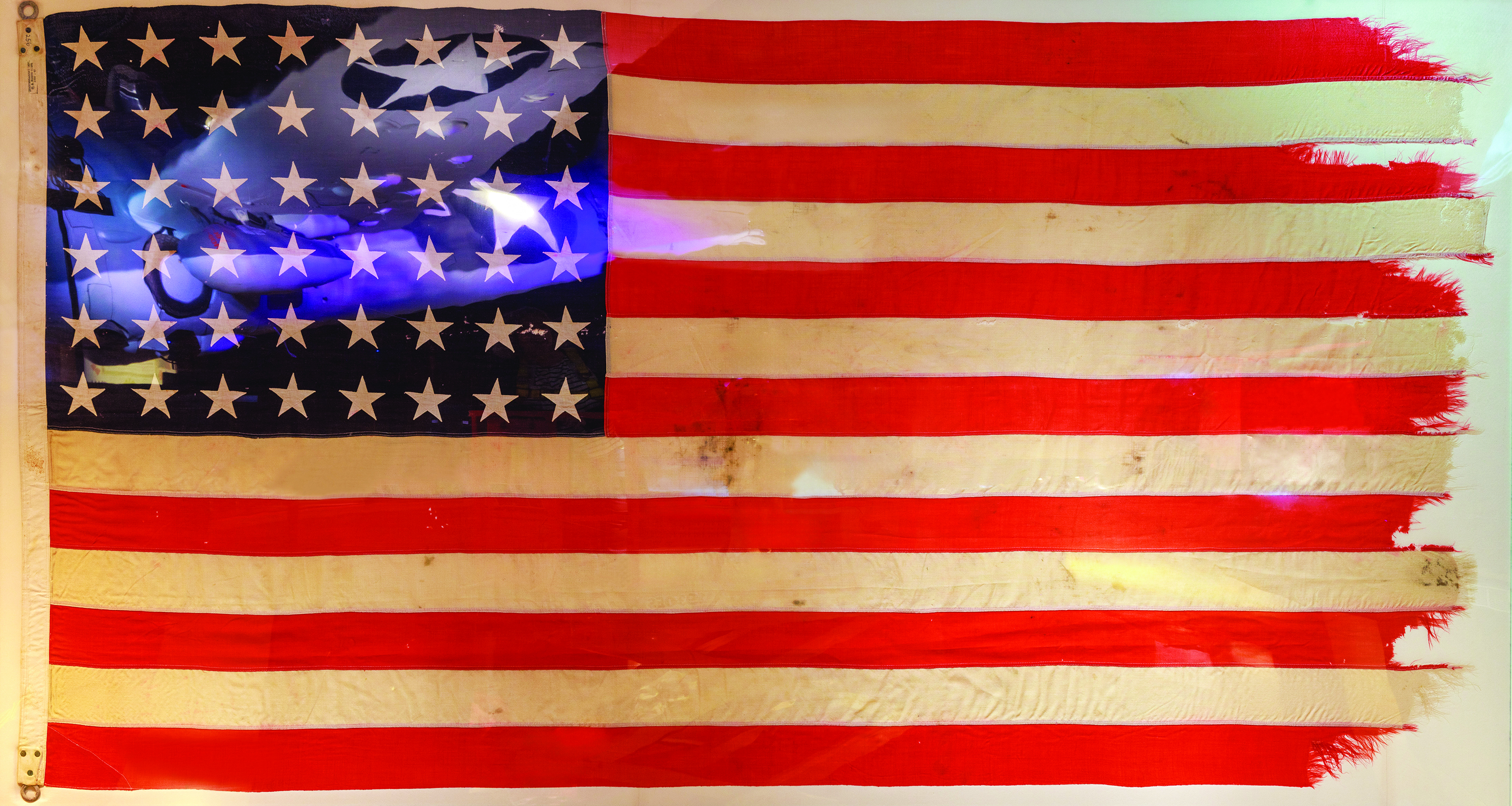

Wake Island Flag

The Fall of the Pacific Alamo

By Laurence M. Burke II, PhD, Aviation Curator

Featured artifact: U.S. National Ensign (1982.975.1)

In 1956, a rather remarkable flag found its way back to the United States. A Japanese woman, Shizu Fukatsu, formally presented an American flag to U.S. Marine major general Alan Shapley, commanding general of the 3d Marine Division.

The Wake Island flag on display in the National Museum of the Marine Corps. A Grumman F4F Wildcat in the exhibit, representative of the aircraft used to defend Wake, is visible as a reflection in the flag’s canton.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

This was one of the American flags flying over Wake Atoll on 23 December 1941, the date that the atoll fell to the Japanese after a heroic resistance by its U.S. Marine defenders. It was taken as a souvenir by Mrs. Fukatsu’s son, Taro Fukatsu, who had been an officer in the Japanese landing force that took the atoll.[1] The story of Wake’s resistance kept American morale up in the immediate aftermath of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. That this flag continued flying over the atoll during the battle makes it a powerful symbol of the Marines’ stubborn defense against incredible odds and despite their own inadequate resources.

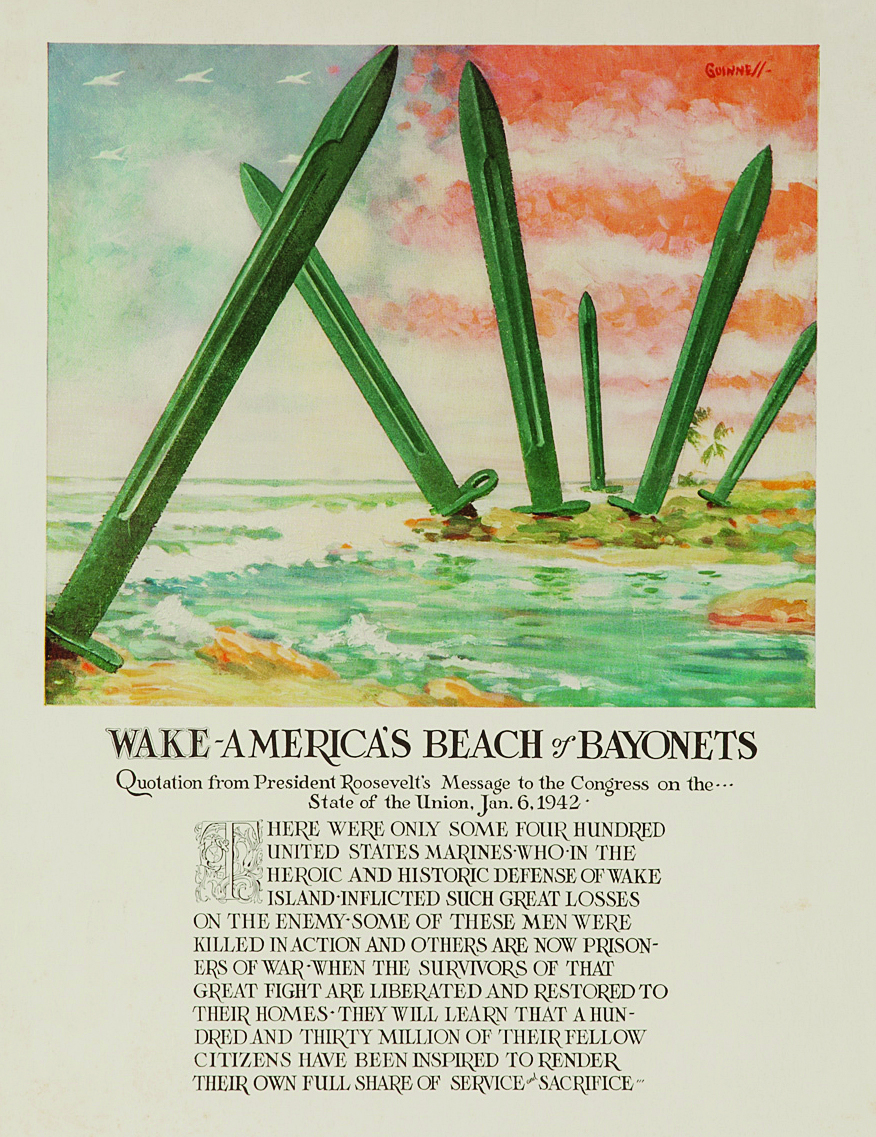

An illustration of the Battle of Wake Island by Albin Henning. Henning created this image before details of the defense of Wake became known, so it does not accurately reflect what happened, but it does convey the Marines’ spirited defense against the Japanese assault.

Official U.S. Marine Corps photo.

The Japanese began bombing the American outpost on Wake mere hours after their attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December (8 December Wake time). The attacks continued for the next two weeks, including near-daily aerial raids and one amphibious landing attempt on 11 December, which was repulsed. These attacks slowly whittled away at the defenders’ resources, which were already limited; both the 1st Marine Defense Battalion detachment and Marine Fighter Squadron 211 (VMF-211) were understrength and lacked critical equipment and material even before the attacks began. But, as the first Japanese attempt to invade the island proved, this lack of resources did little to diminish the willingness of the Marines to defend the atoll with what they had left.

On 23 December, the Japanese launched a second assault on Wake with a landing force about twice the size of that used in the first attempt and with the support of two aircraft carriers, which the first assault did not have. With no more flyable planes, the remaining Marines of VMF-211 joined the defense as infantry. While the landing Japanese troops were stopped or even eliminated in several places, the largest enemy force on the atoll’s main island soon approached the U.S. command post, forcing Navy commander Winfield S. Cunningham, the garrison’s commanding officer, to surrender to the invaders.

This Vic Guinness recruiting poster takes inspiration from President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s description of the Marines’ defense of Wake.

National Museum of the Marine Corps.

Even before the surrender, the U.S. media began making connections with another plucky American defense against overwhelming odds a century earlier, referring to Wake as the “Alamo of the Pacific.” The surrender of Wake only cemented the comparison, although the U.S. defenders, along with the majority of the roughly 1,200 civilian contractors on the atoll, were taken into captivity for the duration of the war rather than killed in battle or executed immediately afterward, which had been the fate of the Alamo defenders in 1836. That said, five of the American prisoners of war were ritually beheaded by the Japanese on the ship taking them to a prisoner-of-war camp in China, and 98 civilians kept on Wake as forced labor were executed by the Japanese—a war crime—following a U.S. Navy carrier air strike on the atoll on 5 October 1943.[2]

Though Wake had been considered an important part of the U.S. defense system in the Pacific before World War II, the atoll was bypassed and isolated as part of the Allied island-hopping campaign. U.S. carrier air forces did strike the atoll a few times during the war to train new pilots and ensure that the Japanese forces there would not be a threat.[3]

Wake remained under Japanese control until shortly after the formal Japanese surrender aboard the battleship USS Missouri (BB 63) in Tokyo Bay on 2 September 1945. Two days later, the Japanese garrison on Wake returned the atoll to a force of Marines under Major General Lawson H. M. Sanderson. Colonel Walter L .J. Bayler, the last Marine to leave Wake in 1941 before it was captured, was the first American to set foot on the atoll after the Japanese surrender.

Japanese forces on Wake return the atoll to the United States on 4 September 1945.

Official U.S. Marine Corps photo.

Though Wake was once again under the American flag, at least one of the flags taken down in 1941 when the Americans surrendered remained in Japan. According to Mrs. Fukatsu, her son, Taro Fukatsu, had been the only one of 12 officers in the Japanese landing force to survive the Battle of Wake. When he returned to Japan in the spring of 1943, he gave this flag to his mother to keep for him, telling her that he had gotten it on Wake. He returned to combat and died as a lieutenant commander on 25 October 1944 in the Battle of Leyte Gulf. His family held on to the flag for many years, as it was the only thing they had by which to remember their son and brother. By 1956, however, they decided that it was proper to return the flag to the United States.[4] The flag is now in the collection of the National Museum of the Marine Corps, where it serves as a powerful memento of the dogged but ultimately doomed resistance of the Marines on Wake.

Endnotes

[1] The story of the flag’s return is derived from the catalog file at the National Museum of the Marine Corps.

[2] The narrative of the battle for and surrender of Wake Island is derived from Gregory J. W. Urwin, Facing Fearful Odds: The Siege of Wake Island (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997); and John Wukovits, Pacific Alamo: The Battle for Wake Island (New York: New American Library, 2003).

[3] Clark G. Reynolds, The Fast Carriers: The Forging of an Air Navy (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1968), 154, 246, 365.

[4] Catalog file, National Museum of the Marine Corps.