Chapter 26

A Flag’s Journey

From Mount Suribachi to the National Museum of the Marine Corps

By Owen Linlithgow Conner, Chief Curator

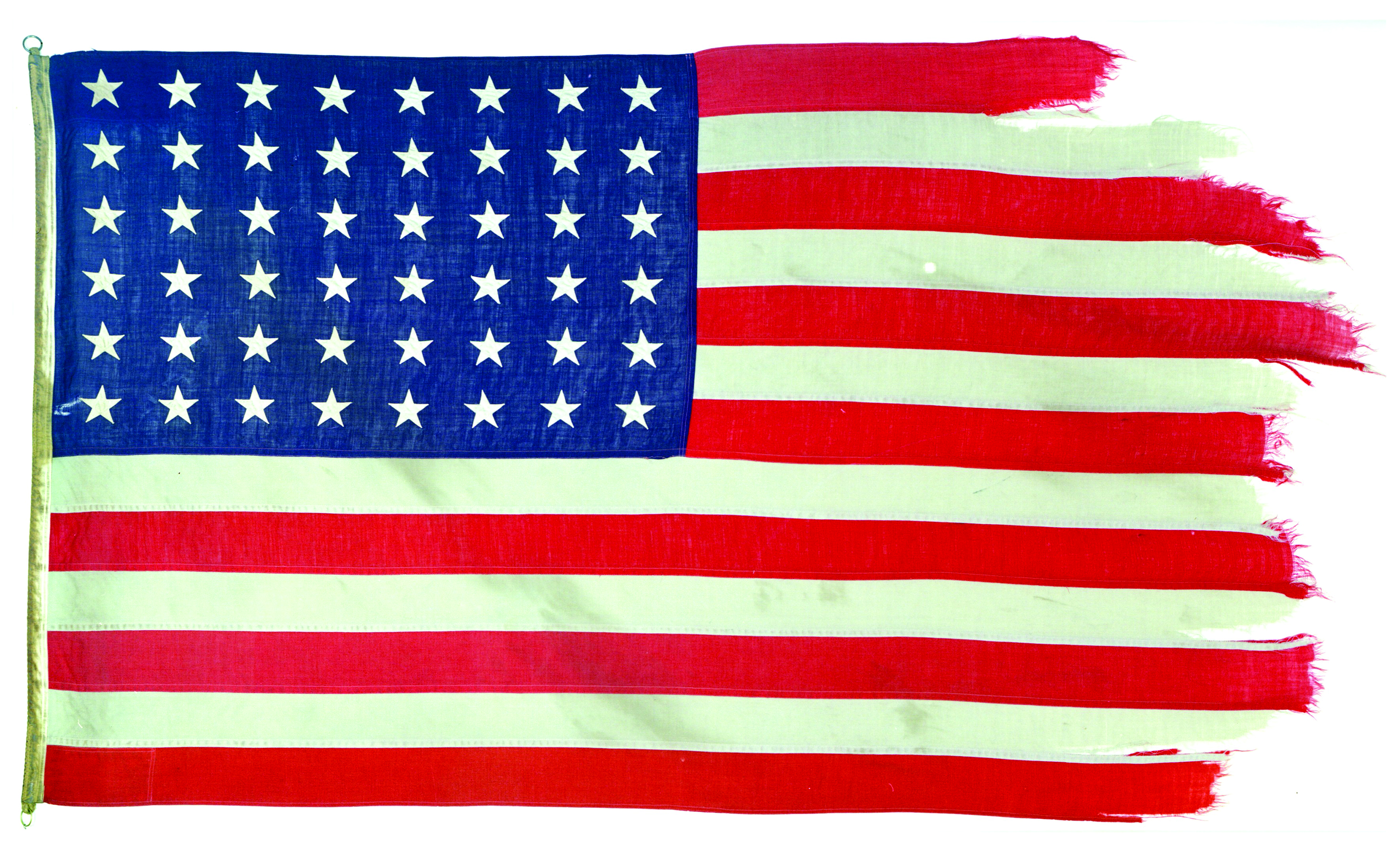

Featured artifact: Flag, U.S. National Ensign (1974.2765.1)

The two most famous flags flown over Iwo Jima currently reside at the National Museum of the Marine Corps.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

On the morning of 19 February 1945, the first U.S. Marine Corps assault units landed on the beaches of Iwo Jima, prepared to wrest the island away from the Japanese. While the first waves of troops were surprised by the lack of enemy fire, all illusions of a quick and easy victory came to a halt as the Japanese let loose with a barrage of rifle, machine gun, mortar, and artillery fire on the Marines as they stacked up on the beaches.

The invasion of Iwo Jima differed from earlier battles in the Pacific theater of World War II in many ways. The assault marked the first time that U.S. ground forces landed on a Japanese home island. It was also the most highly covered invasion of the Pacific War. Sixteen Marine Corps combat correspondents and ten civilian reporters took part in the first stages of the invasion.[1] This media coverage was a far cry from the early days of World War II, when a rare few combat correspondents were allowed to participate in U.S. landings and the primary images that came back to the United States to document the battle often originated with battlefield artists rather than photographers. Those early stories and illustrations often took weeks to reach the United States, as they slowly made their way across the vastness of the Pacific. With so many journalists of all types observing and taking part in the action, the Battle of Iwo Jima certainly did not suffer from a lack of historical documentation.[2]

On D+4 (23 February, four days after the first landings), a small group of Marines gathered to perform a reconnaissance patrol of Mount Suribachi, located on the southeast end of Iwo Jima. The dark, rugged, bomb-battered feature marked the highest point of the island and served as a key location for Japanese artillery spotters. Carefully ascending the mountain, the Marines reached the top after around 40 minutes. To their surprise, they met little resistance. Recognizing the significance of the moment, the Marines rushed back to their lines to inform their officers of the good news.[3]

First Lieutenant Harold G. Schrier, the executive officer of Company E, 2d Battalion, 28th Marine Regiment, 5th Marine Division, was quickly ordered to take a Marine platoon to the summit. He was provided with a medium-size U.S. flag that measured 55.5 inches wide by 28.5 inches tall.[4] Once Schrier’s Marines had secured the position, they were ordered to raise the flag to signal their success.

The first flag flown above Mt. Suribachi.

National Museum of the Marine Corps.

1stLt Harold G. Schrier’s patrol raises the first U.S. flag on Iwo Jima.

Official U.S. Marine Corps photo.

Oft-repeated accounts of the first flag raising unquestioningly state that the flagpole used came from a nearby Japanese water cistern or was a piece of pipe that just happened to be nearby. The pipe also just happened to have a .30-caliber bullet hole in the exact location that allowed the lower half of the flag to be tied down. If true, this seems unbelievably fortunate. In 2020, a collection donated to the National Museum of the Marine Corps by the family of U.S. Navy radioman third class Earl M. Lewis challenged this “fact.” Lewis was a member of the Marine Corps’ 1st Joint Assault Signal Company (JASCO) during the Battle of Iwo Jima. This unit coordinated and controlled field artillery, naval gunfire, and close air support during the battle. In postwar stories, Lewis maintains that Marines confiscated the center tent pole from his JASCO position to carry to the top of Mount Suribachi. While the story is based on just one primary source, it does seem more plausible that a locally procured pole with a prepunctured hole was carried up the mountain by Schrier’s platoon. Contrast this with the idea that a perfectly sized pipe, punctured in the perfect spot for a 28.5-inch flag, was simply found on top of the mountain. Further bolstering Lewis’s claim are period specifications for numerous large military command tents. Many of these show that center tent poles in the 13- to 18-foot range were commonly used.[5]

The exact origins of the pipes used in the Iwo Jima flag raisings have long been speculative, with new claims only coming to light in recent years.

Official U.S. Marine Corps photo.

Regardless of the origins of the pole, at 1030 that morning, Schrier and his Marines succeeded in raising the first flag atop Mount Suribachi. The event was captured on film by Sergeant Louis R. Lowery, a Marine Corps combat photographer. Numerous oral histories from the war documented how the moment was received. Marines in their fighting positions ashore Iwo Jima cheered as best they could while the battle continued. Numerous warships from the invasion fleet sounded their horns in recognition of the first flag raised.[6]

Over the years, many reasons have been suggested for why the first flag was removed in favor of the more famous second, larger version. However, the reality of events makes the true story quite simple. Once the original flag was raised, its small scale compared to Mount Suribachi became obvious to all. Lieutenant Colonel Chandler W. Johnson, the commanding officer of 2d Battalion, 28th Marines, ordered it to be replaced with a larger flag simply to make it easier to see.[7] Johnson sent Second Lieutenant Albert T. Tuttle to the landing beaches to obtain a larger flag, one that was “large enough that the men at the other end of the island will see it. It will lift their spirits also.”[8] Sergeant Michael Strank confirmed this account, noting that the Marines’ intention was to fly a flag so large so that “every son of a bitch on this whole cruddy island could see it.”[9]

The iconic second Iwo Jima flag is significantly larger and was more visible to the Marines fighting below Mount Suribachi.

Official U.S. Marine Corps photo.

The flag obtained by Tuttle was provided by U.S. Navy Reserve lieutenant (junior grade) Alan S. Wood, communications officer for the landing ship tank USS LST 779. Wood had rescued the flag from a salvage depot at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, before his ship deployed.[10] An official U.S. Navy Size 7 Ensign, the flag originally measured 106 by 56.5 inches.”[11] According to Wood, it was the largest on board the LST 779 and was flown almost exclusively on Sundays as the ship crossed the Pacific.[12]

This second flag more than doubled the first in size. It was quickly provided to Private First Class Rene A. Gagnon, who was serving as a runner between Johnson’s headquarters and Schrier’s platoon. Among reporters, word spread about the events of the morning’s first flag raising. On his way up the summit, Associated Press photographer Joseph J. “Joe” Rosenthal encountered Sergeant Lowery, who told him that he had missed the flag raising but that the view from the position was still worth the climb. Disappointed, Rosenthal almost turned around, but eventually he decided to see what was happening atop Mount Suribachi regardless. When he arrived, Rosenthal noticed several Marines preparing the larger flag. Even as an excellent professional photographer, Rosenthal was unsure of his chances of getting a good photograph of the flag as it was lifted. He later recounted, “it’s chancy that I would get the position right. . . . [M]ost of this stuff is like shooting a football play. Things change so quickly in action.” Undaunted, he scouted a position appropriately distant from the action and built a small platform of sandbags and rocks to stand on. As he began a brief conversation with Marine Corps correspondent Sergeant William H. Genaust, they were interrupted by the sudden raising of the new flag. As he lifted his 4 x 5 Speed Graphic camera, Rosenthal recalled, “I wasn’t thinking about the first picture . . . or the second picture. My response was good . . . I could only hope that it turned out the way that it looked in the finder.”[13]

Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal captured arguably one of the most famous images in United States history. The second flag in this image has a long and fascinating story in its final journey to the National Museum of the Marine Corps.

Official U.S. Marine Corps photo.

Before taking his famous photograph, Joe Rosenthal carefully built a small platform for his series of images.

Official U.S. Marine Corps photo.

Unsure of the quality of the photographs he was able to capture, Rosenthal decided to ask the Marines to pose for a backup image of the flag in case the originals did not work out. He called this photograph his “Gung Ho” image. Posing a group of celebrating Marines in this way was a common tactic of correspondents of the era, getting as many men and their hometowns in the newspapers as possible. With his day completed, the Rosenthal descended back down Mount Suribachi and sat down to a well-earned meal of rations before returning to his transport ship to have his film sent to Guam as quickly as possible.[14]

As Rosenthal’s film was processed on the evening of 23 February, it was carefully developed by Staff Sergeant Werner H. Schmitz and passed along to the Office of War Information for approval. Schmitz immediately recognized that one photograph of the flag raising stood alone in quality and composition.[15] Rosenthal’s iconic image was relayed to the United States in lightning fashion by the standards of the era. Sent to San Francisco, California, via the Associated Press Wirephoto service (an early form of fax machine), it appeared on the front page of several American newspapers almost immediately. On 25 February 1945, The New York Times used the image on the front page of its Sunday newspaper. Other publications quickly followed suit, and the photograph soon became synonymous with U.S. victory in World War II—even though the battle was still raging on at Iwo Jima.[16] By the summer of 1945, the photograph’s cultural impact had only increased, with it being repurposed for recruiting and war bond posters, made into sculptures, and even winning the Pulitzer Prize for its photographer.[17] In many ways, Joe Rosenthal’s image of the second flag raising marked the United States’ first modern media sensation. It was a viral image that came decades before the term was invented.

Recognizing the importance of the photograph and the moment it captured, the Marine Corps, under the direction of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, did its best to recall the surviving servicemembers who were believed to have participated in the second flag raising. The Corps also ordered both the first and second Iwo Jima flags to be safely secured and preserved for historical purposes. The now-famous second flag flew over Iwo Jima for more than three weeks. It was finally taken down on 14 March 1945. At that time, a third Iwo Jima flag was then raised at the V Amphibious Corps landing force command post as the U.S. Navy Military Government of Iwo Jima was established.[18] Official correspondence from Headquarters Marine Corps, dated 26 April, documents the return of the flags to the United States.[19]

The Seventh War Loan: “Now . . . All Together”

On 12 April 1945, President Roosevelt died in Warm Springs, Georgia. One of the president’s lasting legacies was his dedication to numerous war bond tours during World War II, designed to help finance the greatest—and costliest—war in American history. In part to honor Roosevelt’s legacy and friendship, Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau Jr. aimed to make the Seventh War Loan Drive the biggest and most successful yet.[20]

An original Seventh War Loan poster as designed by artist C. C. Beall.

National Museum of the Marine Corps.

Government officials were concerned that the public’s interest in the loan drive, to be known as the “Mighty Seventh,” would need to be raised. To create excitement, a near-perfect symbol of American patriotism would be required. The loan drive’s organizers were given this improbable gift with the publication of Rosenthal’s photograph. Under the guidance of Theodore R. “Ted” Gamble, a former movie theater owner turned director of the War Finance Division of the U.S. Treasury Department, an oil painting of the photo was commissioned. The artist was C. C. Beall, a well-known commercial illustrator and portrait artist of the period. After a brief competition between other works, the composition was selected as the primary poster for the loan drive. The next hurdle came in selecting an appropriate title for the image. Numerous advertising agencies submitted ideas, such as “Lend a Mighty Hand”; “Shoulder Your Share!”; “Spirit of the 7th!”; and “Now, All Together!” The loan drive organizers eventually settled on “Now, All Together for the 7th.”[21]

This simplified Seventh War Loan poster was used throughout the country during the tour’s record-breaking success.

National Museum of the Marine Corps.

The second “Rosenthal flag” next appeared on 9 May 1945, when it was raised to half-staff at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, DC, in honor of President Roosevelt. Iwo Jima veterans Private First Class Ira H. Hayes, Private First Class Rene A. Gagnon, and Navy pharmacist’s mate second class John H. Bradley performed the honor. The event was part of a media campaign to commence the flag’s 33-city journey as a part of the Seventh War Loan Drive. It would be hoisted again in New York City; Chicago, Illinois; Boston, Massachusetts; and numerous other cities large and small. As a part of the tour, the flag was either raised on a flagpole, on a replica Iwo Jima statue, or by the three veterans. The Seventh War Loan Drive began on 14 May and ended on 30 June 1945. Its target goal was to raise $14 billion. Remarkably, it collected more than $26 billion.[22]

Ira Hayes, John Bradley, and Rene Gagnon pose with the second flag during the Seventh War Loan drive.

Official U.S. Marine Corps photo.

Official correspondence dated 18 July 1945 from the Office of the Curator, Marine Corps Museum, acknowledged the three flags’ acceptance to their home in Quantico, Virginia.[23] This was the first known Marine Corps museum, founded in 1940 at Little Hall, Marine Corps Base Quantico. The museum’s collection consisted of battle trophies from World War I, historical flags, and weapons displayed on the second floor of the building. The displays were complimented with numerous uniform mannequins in approximations of Marine Corps uniforms from 1775 to World War I.[24]

The Marine Corps security guard for the Freedom Train stands in formation for one of their hundreds of stops across the United States in 1947.

National Archives and Records Administration.

A misconception of historical artifacts in museums is that objects are either displayed or placed in storage in perpetuity. The two flags flown atop Mount Suribachi, however, are different. Even as museum artifacts, their cultural relevance has led them to always lead an active life. Curatorial records dated 26 July 1946 document the first of many times that a famous Iwo Jima flag was placed on temporary loan by the museum. Most of these early displays were associated with veteran reunions, particularly those involving the 5th Marine Division. Subsequent loans occurred in the 1950s. At these conventions, the iconic flag was displayed proudly by the Marine division that raised it.

This receipt for the flags from Iwo Jima is one of the earliest museum documents in the collection of the National Museum of the Marine Corps.

National Museum of the Marine Corps.

In 1947, the flags were given a more unusual opportunity to travel the United States. Following World War II, members of the administration of President Harry S. Truman felt that patriotism across the United States was declining. As a result, they decided to organize the world’s most unusual traveling historical road show. Dubbed the “Freedom Train,” this historical exhibit would be housed in a train and travel the length of the country and back. It would contain some of the United States’ most significant artifacts, including Thomas Jefferson’s personal copy of the Declaration of Independence, a first-edition copy of Thomas Paine’s pamphlet Common Sense, George Washington’s copy of the U.S. Constitution, the U.S. Bill of Rights, Abraham Lincoln’s draft of the Emancipation Proclamation, surrender documents signed by the Japanese Empire aboard the USS Missouri (BB 63) to formally end World War II, and the iconic second flag raised on Mount Suribachi. Guarding these historical treasures was a Marine security guard detachment comprised of 3 Marine officers, 23 enlisted Marines, and 1 Navy corpsman. The exhibit would travel to 322 cities and nearly every state capitol, totaling more than 60,000 kilometers. More than 34 million Americans turned out to attempt to view the exhibits, with 3.5 million given the opportunity to walk inside the train to view its contents. The museum cases were built with bulletproof glass and secured by state-of-the-art locks. Marines were placed throughout the train to watch over the artifacts and to act as impromptu tour guides.[25]

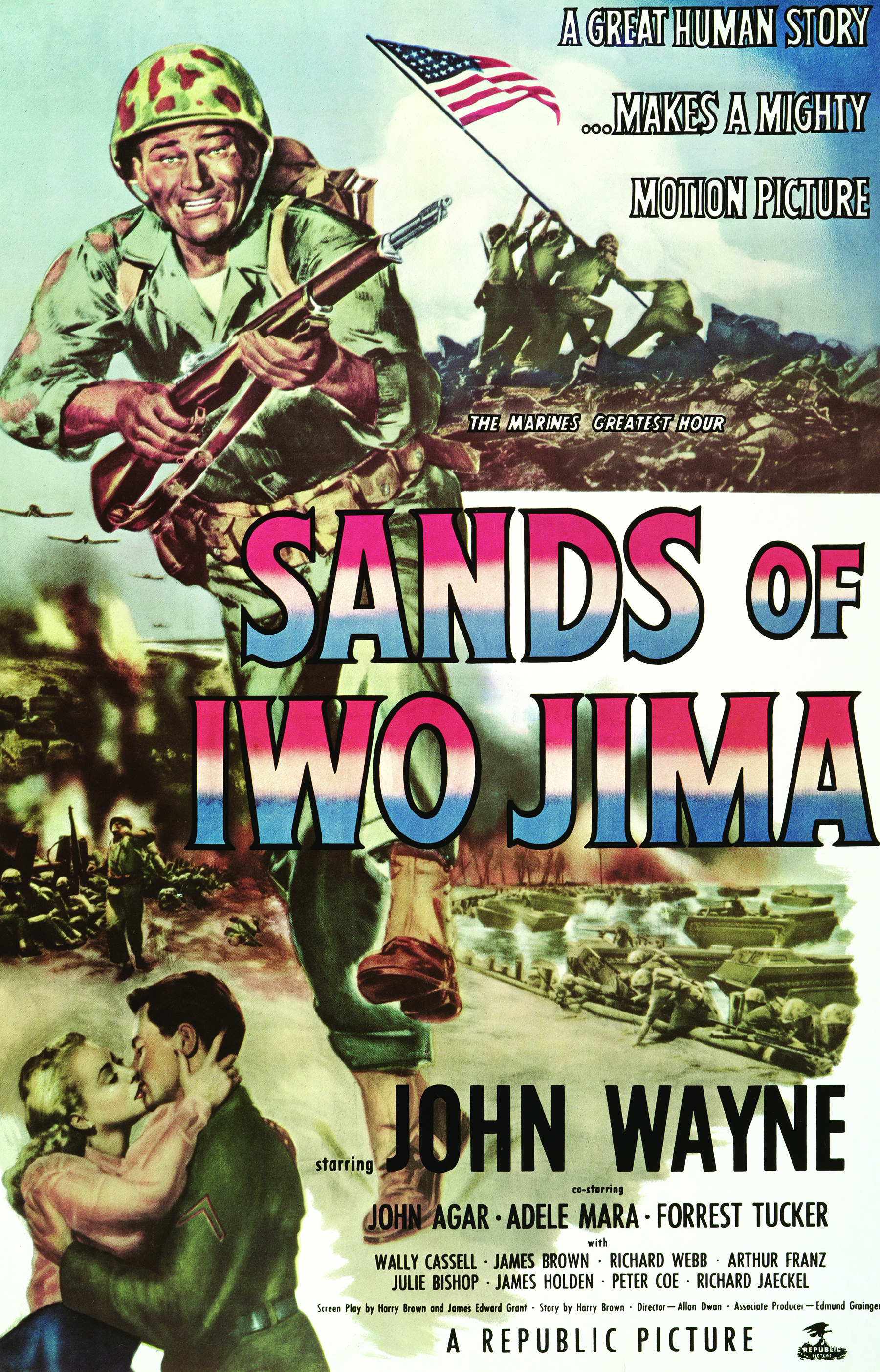

An original movie poster from the John Wayne film, The Sands of Iwo Jima.

National Museum of the Marine Corps.

Following the Rosenthal flag’s journey on the Freedom Train, it was seen again in 1949 when it was reunited with the three Iwo Jima veterans from the Seventh War Loan Drive. They appeared alongside the original artifact in the John Wayne film The Sands of Iwo Jima. In the film’s climatic scene, the veterans present Wayne, playing the fictional role of Marine Corps sergeant John Stryker, with the actual Iwo Jima flag for a Hollywood recreation of the Marine Corps’ defining moment. Despite the nation’s weariness of war films by this time, the film garnered four Academy Award nominations and was a resounding box office success.[26]

During the 1950s, the two Iwo Jima flags settled into a less glamorous lifestyle as traditional museum artifacts. While occasionally still sent out for 5th Marine Division reunions, they were more often simply displayed in the early Marine Corps museum system. During the 1960s, the historical displays were moved to Butler Hall at Marine Corps Base Quantico. Then, in the 1970s, a museum was established under the Marine Corps History and Museums Division at the Washington Navy Yard in Washington, DC.[27]

This image of the second Iwo Jima flag is from the late 1990s when the flag underwent extensive conservation.

National Museum of the Marine Corps.

Over the years, early mounting and display techniques for the two flags began to take their toll. In 1998, the Marine Corps recognized the need to properly conserve and frame the flags. Funding was approved by Commandant of the Marine Corps, General Charles C. Krulak. The flags were sent to professional conservators for treatment and framing, current with modern museum standards. All the flags’ markings and damage were thoroughly documented for the first time. In-depth analysis of the fabrics, weaves, and thread counts were also noted in curatorial records. Once placed in specially constructed pressure-mounted frames, the flags returned to the Washington Navy Yard.[28]

In the early 2000s, the second and first flags were sent out, respectively, for brief loans and exhibition at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History in Washington, DC, and the National WWII Museum in New Orleans, Louisiana. These travels marked the flags’ final temporary journeys.

Today, the two iconic Iwo Jima flags are a proud part of the permanent collection at the National Museum of the Marine Corps. The second flag is on display in the museum’s World War II gallery, while the first flag rotates on an annual basis each year on the anniversary of the Battle of Iwo Jima.

Endnotes

[1] Public Relations Officer to Director, Division of Public Relations, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, Washington DC, 21 April 1945, 5–6 (Box 89, Record Group 127, Iwo Jima, 4th and 5th Marine Divisions, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC).

[2] For more on the impact of this historical documentation on the facts of battle and activities on the island, see Brianne Robertson, ed., Investigating Iwo: The Flag Raisings in Myth, Memory, & Esprit de Corps (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps History Division, 2019).

[3] Hal Buell, Uncommon Valor, Common Virtue: Iwo Jima and the Photograph that Captured America (New York: Berkley Publishing, 2006), 99.

[4] Official conservation measurements come from “Flag, National, U.S., 48 Star” [1974.2312.1], Catalog File, National Museum of the Marine Corps, hereafter U.S. flag catalog file.

[5] Earl Lewis Collection [2020.51], Catalog File, National Museum of the Marine Corps.

[6] Buell, Uncommon Valor, Common Virtue, 101.

[7] Robertson, Investigating Iwo, xx–xxi.

[8] Bernard C. Nalty and Danny J. Crawford, The United States Marines on Iwo Jima: The Battle and the Flag Raisings (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1995), 5.

[9] Robertson, Investigating Iwo, xx.

[10] Letter from Lt(JG) Allan Wood, USNR, to BGen Robert L. Denig, USMC, Director, Division of Public Information, Headquarters Marine Corps, 7 July 1945, hereafter Wood to Denig.

[11] U.S. flag catalog file.

[13] Buell, Uncommon Valor, Common Virtue, 107–11.

[14] Buell, Uncommon Valor, Common Virtue, 111–12.

[15] Robertson, Investigating Iwo, 47–48.

[16] Robertson, Investigating Iwo, 48–49.

[17] Robertson, Investigating Iwo, 57.

[18] “American Flag Raised in the Corps Command Post on Iwo Jima,” Official U.S. Marine Corps Correspondence, from Gen Alexander A. Vandegrift, Commandant of the Marine Corps, to MajGen Harry Schmidt, Commanding General, V Amphibious Corps, 25 March 1945.

[19] Official U.S. Marine Corps Correspondence, Headquarters, V Amphibious Corps, 26 April 1945.

[20] Karal Ann Marling and John Wetenhall, Iwo Jima: Monuments, Memories, and the American Hero (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991), 103.

[21] Marling and Wetenhall, Iwo Jima, 104, 107.

[22] “Seventh and Eighth War Loan Collection Finding Aid,” Pritzker Military Museum and Library, Chicago, IL, 2016, updated 2018.

[23] Official U.S. Marine Corps Correspondence, from Officer in Charge, Office of the Curator, Marine Corps Museum, Marine Barracks, Quantico, VA, to Officer in Charge, Historical Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, DC, 18 July 1945.

[24] Kenneth L. Smith-Christmas, “Why Things Are the Way They Are at the Marine Corps Museum” (unpublished paper, Marine Corps Museum, Quantico, VA, n.d.), 1.

[25] Sgt Jorge Vallejo, “Freedom Train: 1947,” Marines (March 1988): 23–24.

[26] Sands of Iwo Jima, directed by Allan Dwan (Los Angeles, CA: Republic Pictures, 1949).

[27] Smith-Christmas, “Why Things Are the Way They Are at the Marine Corps Museum,” 1.

[28] Kenneth L. Smith-Christmas, “Measures Ensure Iwo Jima Flags’ Survival,” Fortitudine 28, no. 3 (2000): 12–13.