Chapter 24

One Uniform, Many Stories

The Marines of Montford Point

By Owen Linlithgow Conner, Chief Curator

Featured artifacts: Coat, Service, Winter, Enlisted (2012.19.1 a-c); Coat, Utility (2010.89.3); and Medal, Congressional Gold Medal, Montford Point Marines (2012.67.1)

When artifacts are offered to the National Museum of the Marine Corps (NMMC), the first objects most often discussed are inevitably a U.S. Marine’s most prized and personal belongings: their green service coat and dress blue uniform. Artifacts such as the dress blue uniform and eagle, globe, and anchor insignia are the common threads that bind Marines old and new, regardless of periods served or the duties or tasks performed. They are products of Marines’ common heritage and traditions. The weapons and vehicles used may change, but wearing the uniform is a unifying experience. In accepting these donations, the NMMC seeks to preserve the history and personal stories of the individual men and women of the Marine Corps and their unique personal stories.

Unfortunately, this was not always the case within the Marine Corps’ museum system. All too often it was assumed that a “blue or green coat” was something the museum already had in abundance. Not enough questions were asked of the individual donors regarding the story of the Marine that wore these uniforms. What did they do in the Marine Corps? Where did they serve? What was their experience in serving? As a result, specific gaps formed in the Marine Corps’ collecting. In 2012, the Commandant of the Marine Corps, General James F. Amos, asked the NMMC to help in honoring the service of the first Black Marines. These pioneering Marines came through the ranks and earned their title at Montford Point, a segregated training base located at Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, in the 1940s. They were honored by the United States by being awarded the Congressional Gold Medal for their service in World War II. In support of this achievement, the Marine Corps wished to see their experience highlighted in its national museum.

This artifact case dedicated to the history of Black Marines was added to the National Museum of the Marine Corps’ World War II gallery in 2012. The collection highlights a Service-wide effort to honor and preserve the story of the Montford Point Marines.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

Remarkably, as curators scoured the NMMC’s collection, few if any period artifacts from Montford Point Marines were found. As a result, the museum immediately set out to correct this deficiency. The staff at the NMMC reached out to veterans, their associations, and families, and significant donations soon followed. During the course of 13 years, new artifacts and history were discovered, and with the help of the Montford Point Marines, their story came to be properly displayed and honored. This history is best seen today in the NMMC’s World War II gallery, where a case filled with artifacts highlighting these Marines can be seen. Each object tells the story of remarkable individuals who played their groundbreaking role in the origins of diversity of the modern Marine Corps today.

Montford Point Marines, 1942–49

On 25 May 1942, the Commandant of the Marine Corps, Lieutenant General Thomas Holcomb, issued a formal instruction to recruit the first “colored male citizens” into the ranks of the Marine Corps. This decision was made reluctantly and with reservations. Classified Letter of Instruction Number 421 stated in stark terms the types of challenges that faced these first Black Marines. The order decreed that “in no case shall there be colored noncommissioned officers senior to (white) enlisted men in the same unit.” The Commandant was publicly quoted saying that Black Americans were “trying to break into a club that doesn’t want them” and that to satisfy their intent to see combat in the war they should look elsewhere and join the U.S. Army.[1]

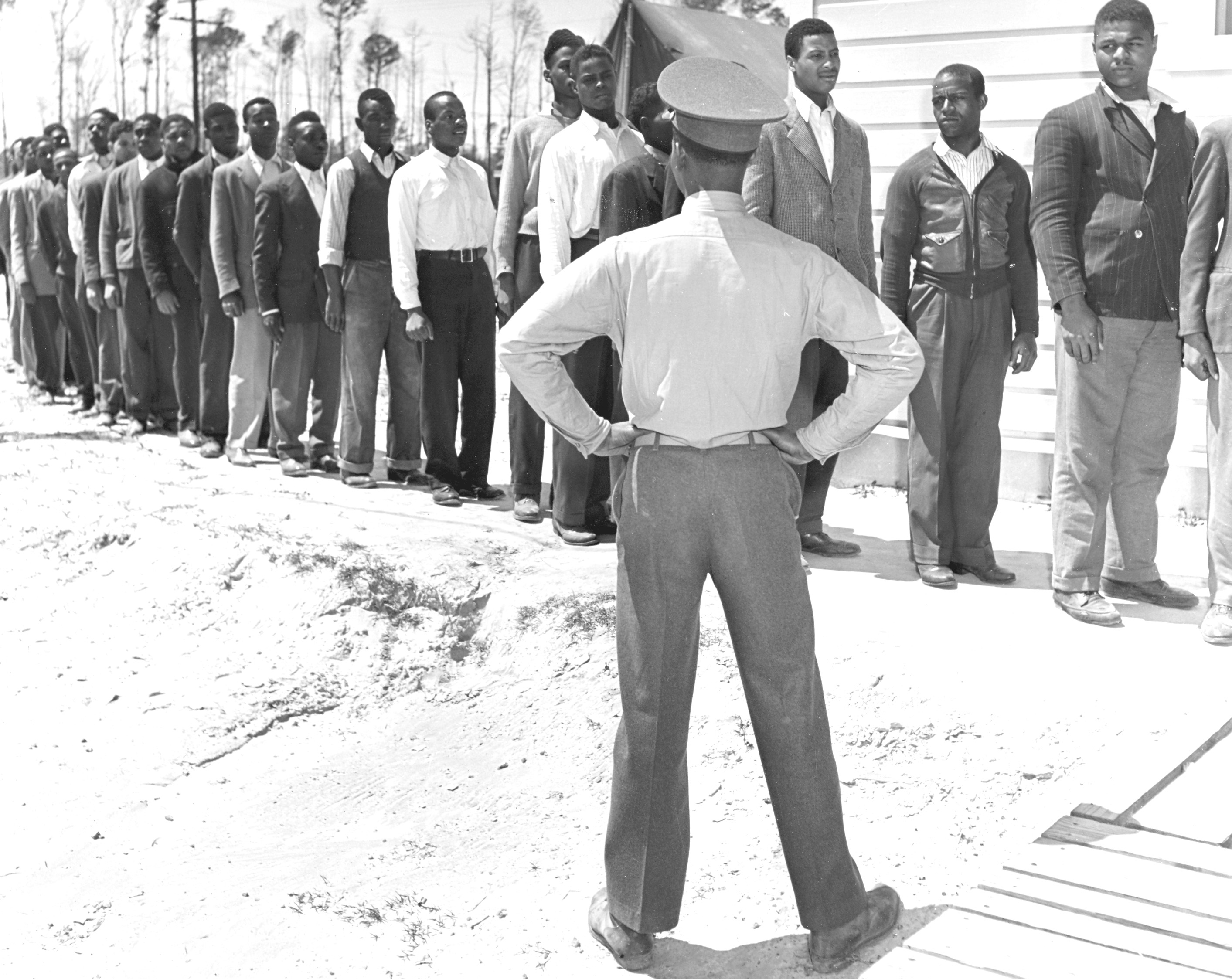

The first Black Marine recruits arrive at Camp Montford Point, New River, NC, in 1942.

Official U.S. Marine Corps photo.

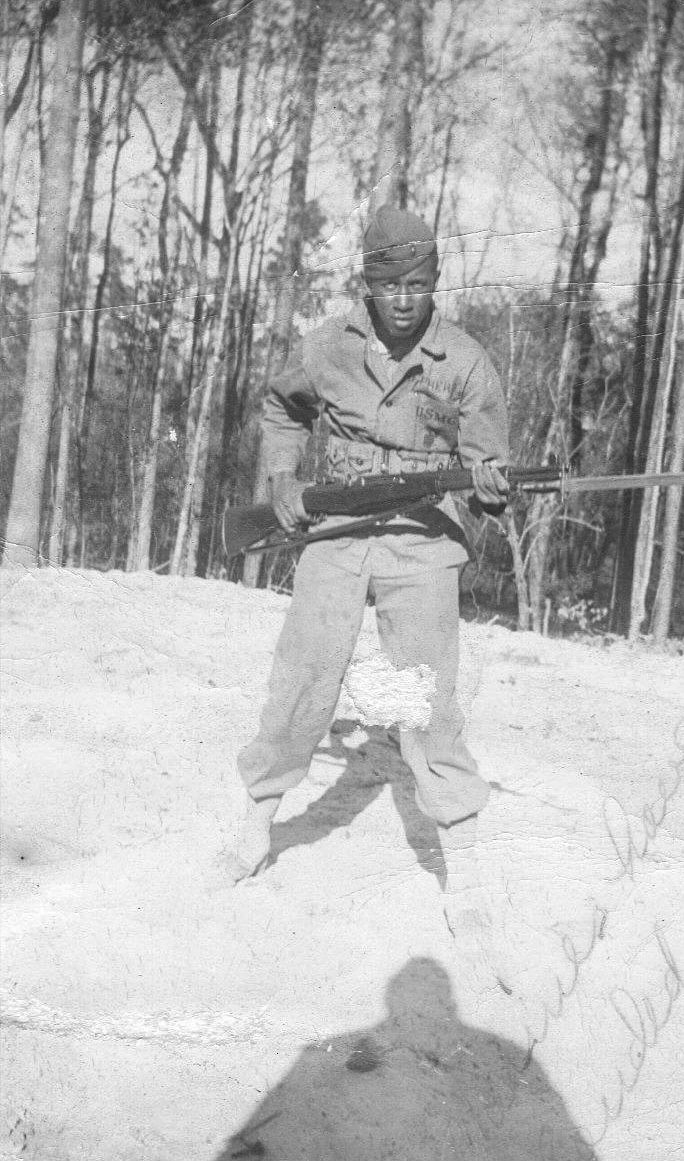

Montford Point Marines were recruited from across the United States to fill the Marine Corps’ ranks. Some members volunteered after being drafted, while others were drafted directly into the Service.

Official U.S. Marine Corps photo.

Confronted with the prevalent mindset of the era, the Montford Point Marines found inspiration within their own ranks. They had their own noncommissioned officers (NCOs) and looked to these men, such as Edgar R. Huff and Gilbert H. Johnson, to lead them. This internal focus helped them rally around one another in their specific units, based on the camaraderie and shared pride of being Marines.

SgtMaj Gilbert Johnson (left) was among the first Black Marines to be trained as drill instructors. He was later in charge of all recruit training at Montford Point. While deployed to the Pacific as a member of the 52d Defense Battalion on Guam, he personally led 25 combat patrols.

Official U.S. Marine Corps photo.

The first Black Marine combat units were the 51st and 52d Defense Battalions. Formed in August 1942 and December 1943, respectively, they would see limited action in defending island bases in the Pacific. Most Black Marines served in 49 depot and 12 ammunition companies. These units were independently assigned to serve alongside all-White Marine units.[2] Ironically, it was within these less glamorous support units that Black Marines would first see combat, particularly during the battles for Saipan, Tinian, and Guam in the Mariana Islands in 1944 and the later epic battles for Iwo Jima and Okinawa in 1945.

The Marines behind the Uniforms

One of the first Montford Point Marine donors to the NMMC was 87-year-old Calvin C. Shepherd. Among his possessions was his original Marine Corps winter service uniform coat.

Calvin C. Shepherd receives his recruit training at Montford Point in 1943.

National Museum of the Marine Corps.

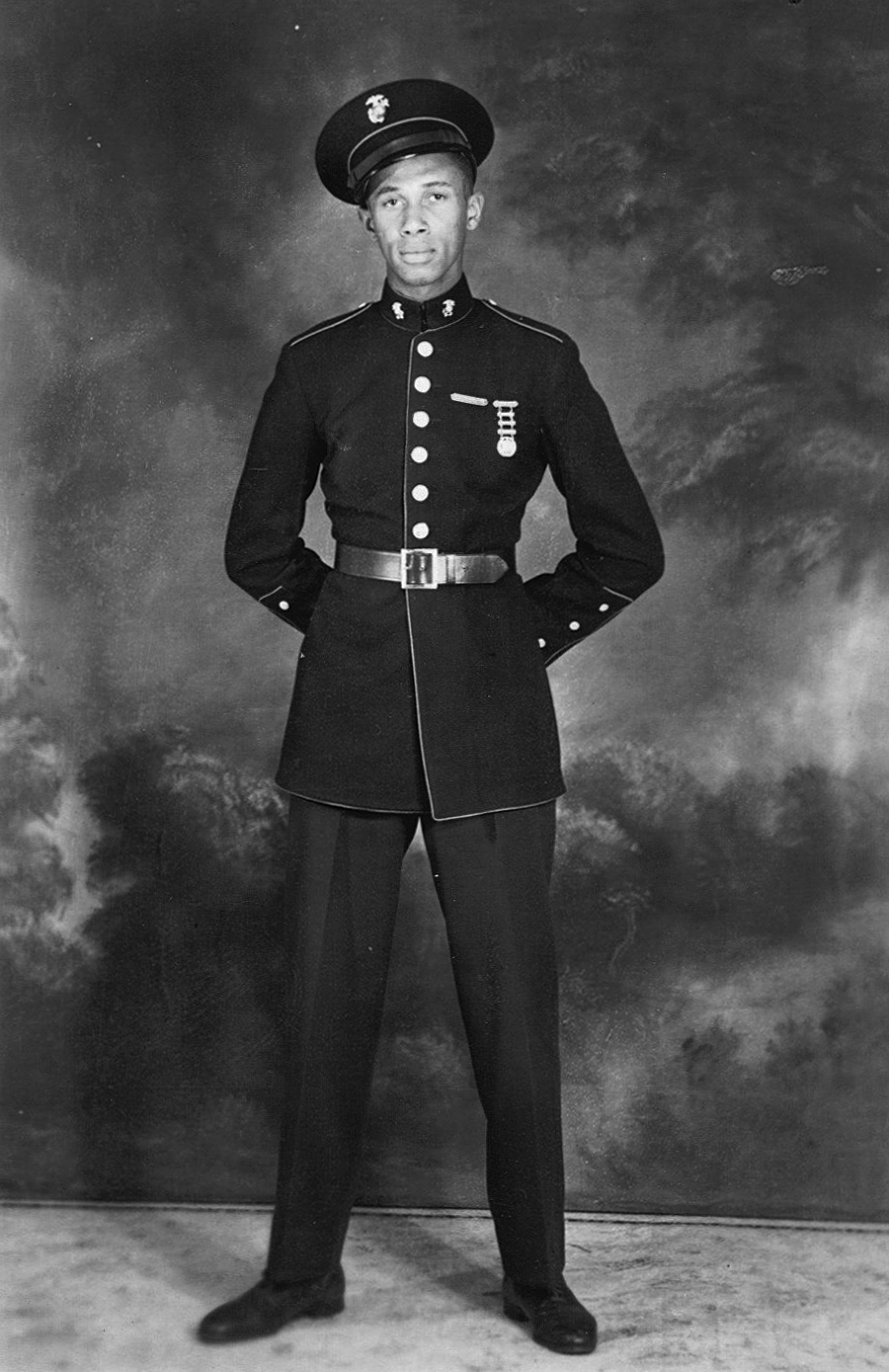

Calvin Shepherd poses for a family portrait in his dress blue uniform. He was proud to have obtained this uniform, as they became limited issue to Marines during the war. Marines who did not have the dress blue uniform issued often had to buy them independently from uniform tailors.

National Museum of the Marine Corps.

Shepherd’s III Amphibious Corps patch is proudly worn on the left sleeve of his service coat.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

Shepherd’s left sleeve displays a small red specialty patch, recognizing his pride in serving in an ammunition company in the Pacific theater of war.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

Calvin C. Shepherd was born on 5 April 1925 in Memphis, Tennessee. He enlisted in the Marine Corps Reserve on 16 August 1943. Following his initial training at Montford Point, he was assigned to vehicle maintenance before finding his permanent assignment in ammunition and ordnance work. In early 1944, Shepherd was promoted to the rank of corporal and deployed to the Pacific with the 4th Marine Ammunition Company. Falling under the command of III Amphibious Corps, support units such as Shepherd’s were vital to the success of the complex amphibious assaults being undertaken by the Marine Corps in the Pacific theater of war. Marine depot supply and ammunition companies often worked with shore party landing units to unload critical supplies and ammunition directly to the beach, passing these on to the Marines on the front lines who desperately needed them.[3]

The Montford Point Marines serving in the segregated 4th Marine Ammunition Company almost saw action at Saipan in June–July 1944, as they were held in reserve with III Amphibious Corps. But they would have to wait for real combat until the assault and capture of Guam in July–August 1944. At 0830 on 21 July, Shepherd and his unit landed with more than 54,000 troops—36,933 Marines and 17,758 soldiers—to take back the island from the Japanese. They took part in the fighting until 9 August 1944.[4] By the campaign’s end, Marine units from III Amphibious Corps had suffered 1,567 killed and 5,308 wounded. The Army’s 77th Infantry Division suffered 839 casualties.[5]

Shepherd escaped the battle physically unscathed and continued to serve in the Pacific during the occupation of Guam. Following the war’s end, he was honorably discharged from the Marine Corps in February 1946. The 4th Marine Ammunition Company was deactivated just weeks later on 8 March 1946.

The uniform that Shepherd wore home is the same green wool enlisted winter service uniform coat currently displayed at the NMMC. It is an interesting uniform for several reasons, highlighting Corporal Shepherd’s unique service. On the left sleeve is the III Amphibious Corps unit patch. It features a red shield with a curled Asian dragon embroidered with yellow and black thread. The Roman numeral “III” is stitched above the dragon in white. This shoulder sleeve insignia represents Shepherd’s segregated company’s service within the much larger III Amphibious Corps during World War II. On the lower cuff of the same sleeve is a small, unauthorized flaming ordnance bomb patch. These small specialty patches were influenced by U.S. Navy uniform rates and patches, but by the height of World War II they were no longer being formally issued at the Headquarters Marine Corps level. This, however, did not stop many Marines from procuring them locally and having them sewn to their uniforms to express unit pride in their responsibilities during the war.

As an NCO, Shepherd’s left sleeve retains his corporal’s chevrons. These are notable as the rank is only sewn to one sleeve. This use of only one chevron rank per uniform coat came from limited wartime rationing. First noted in Letter of Instruction Number 198 on 9 September 1942, the order aimed to conserve wartime materials. When Marine NCOs were promoted, they would remove their previous pair of ranks and turn them into the supply office for reuse. They would then be issued one new chevron rank to be placed on their left sleeve. The order was rescinded by Letter of Instruction No. 198 on 9 September 1945, but many Marines serving overseas did not have an opportunity (or interest) to update their uniforms by the time they were discharged at the war’s end.

Another Montford Point Marine uniform displayed in the NMMC’s World War II gallery belonged to Captain Frederick C. Branch. Branch holds the honor of being the first Black Marine to be commissioned in the Marine Corps.

2dLt Frederick C. Branch is pinned with his officer insignia by his wife on 10 November 1945. He was the first Black Marine officer in the Marine Corps Reserve.

Official U.S. Marine Corps photo.

Frederick Branch’s World War II-era utility uniform is displayed with his name marked in black ink above the chest pocket.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

Born on 31 May 1922 in Hamlet, North Carolina, Branch was educated at Johnson C. Smith University in Charlotte, North Carolina, and Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He received his draft notification in May 1943 and joined the Marines Corps.[6] Despite his higher education, Branch was not offered an officer’s commission due to his race. He was instead assigned to the 51st Defense Battalion. Promoted to the rank of corporal, Branch spent two years serving on Ellice Island in the Central Pacific. All the while, the young Marine remained undaunted in his aspiration to become an officer. Knowing that he needed to impress his superiors before he could apply for a commission again, he set out to win the favor of his battalion’s White commanding officer. Branch wore his uniform impeccably and secured a role in delivering the officer’s daily mail. Over time, he won the colonel’s admiration.[7] When the 51st Defense Battalion was deactivated in July 1944, Branch finally received his chance to become an officer. He was ordered to return to the United States and report to the Marine detachment at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana, for officer training with the Navy’s V-12 program.[8] There, he made the dean’s list and was ordered to Marine Corps Base Quantico, Virginia, after graduation. The sole Black Marine in a class of 250 officer candidates, Branch noted that he was treated fairly and, for the first time in his Marine Corps service, the same as everyone else. After receiving his commission, he was ordered to Camp Pendleton, California, where he served as a platoon commander, a battery executive officer, and a battery commander with the 1st Anti-Aircraft Artillery Automatic Weapons Battalion. As the commander of an all-White platoon, Branch later recalled, “I went by the book and trained and led them; they responded like Marines do to their superiors.”[9] Entering the Marine Corps’ inactive reserve, Branch returned to Temple University in 1947 and graduated with a physics degree. He returned to active duty in 1952 during the Korean War and was promoted to the rank of captain before resigning his commission in 1955 to become a teacher in Philadelphia. He became the science department chair at Murrel Dobbins High School, where he remained for 35 years before retiring in 1988.[10]

Frederick Branch and his wife dedicate Branch Hall on board Marine Corps Base Quantico, VA, in 1997.

Official U.S. Marine Corps photo.

In 1997, Branch returned to Quantico for the dedication of a newly renovated building bearing his name, Branch Hall. Touring the facility with his wife, he was interviewed by local media, and he likely donated his World War II-era utility coat to be displayed for all the Marines working there. No records remain for how long this exhibit lasted, but during a cleaning day in 2005, the artifact was found crammed unceremoniously in a footlocker. The conscientious Marines who discovered it thankfully recognized its significance and transferred the coat to the NMMC. The unfortunate way that the coat had been treated led to significant efforts by the museum to better track and retain records for all historical property held by units and borrowers across the Marine Corps in the future. Today, the NMMC maintains accountability for more than 1,700 artifacts and 188 units and borrowers of history outside the museum’s walls.

Endnotes

[1] Owen L. Conner and Charles Grow, “World War II and the Origins of Diversity,” Leatherneck 95, no. 2 (February 2012): 56.

[2] Gordon L. Rottman, U.S. Marine Corps World War II Order of Battle: Ground and Air Units in the Pacific War, 1939–1945 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2001), 35.

[3] Rottman, U.S. Marine Corps World War II Order of Battle, 35.

[4] Rottman, U.S. Marine Corps World War II Order of Battle, 334.

[5] Cyril J. O’Brien, Liberation: Marines in the Recapture of Guam, Marines in World War II Commemorative Series (Washington, DC: Marine Corps Historical Center, 1994), 44.

[6] Myrna Oliver, “Frederick C. Branch, 82; First Black Officer in the U.S. Marine Corps,” Los Angeles Times, 12 April 2005.

[7] Matt Schudel, “Frederick C. Branch; Was 1st Black Officer in U.S. Marine Corps,” Washington Post, 13 April 2005.

[8] Oliver, “Frederick C. Branch.”

[9] Cpl Gregory S. Gilliam, “Standing Alone,” Marines, September 1997.

[10] Gilliam, “Standing Alone.”