Chapter 23

Civil War Commandant

Leading the Corps amid a Country Divided

By Gretchen Winterer, Uniforms and Heraldry Curator

Featured artifact: Coat, Full Dress, Colonel John Harris (V-0-67)

A ship without Marines is like a garment without buttons.

~ Admiral David D. Porter, U.S. Navy, 1863[1]

As the U.S. Marine Corps’ highest-ranking officer, the Commandant is responsible for preparing and executing all military and administrative duties of the Service. The Commandant reports directly to the U.S. secretary of the Navy, the U.S. secretary of defense, and the president of the United States. In the 1800s, the Marine Corps faced a set of challenges that were not entirely foreign to them: proving their relevance, leadership, and fighting capabilities to a war-torn country. The role of the Commandant was more important than ever before in defending the Marine Corps against scrutiny and molding it into an elite fighting force. Colonel Archibald Henderson, the fifth Commandant, began the Service’s transition from its continental infancy into what is more closely recognized today. His successor, Colonel John Harris, continued to shape the Marine Corps through the troubling years of the American Civil War.

A Critical Era for Commandants

Archibald Henderson was appointed Commandant of the Marine Corps on 17 October 1820. During his 52-year career in the Corps, he fought in the War of 1812 as a young officer, led Marines during the Second Seminole War in 1836–37 and the Mexican War in 1846–48, and oversaw several international expeditions. He also fought for the Marine Corps behind the scenes.

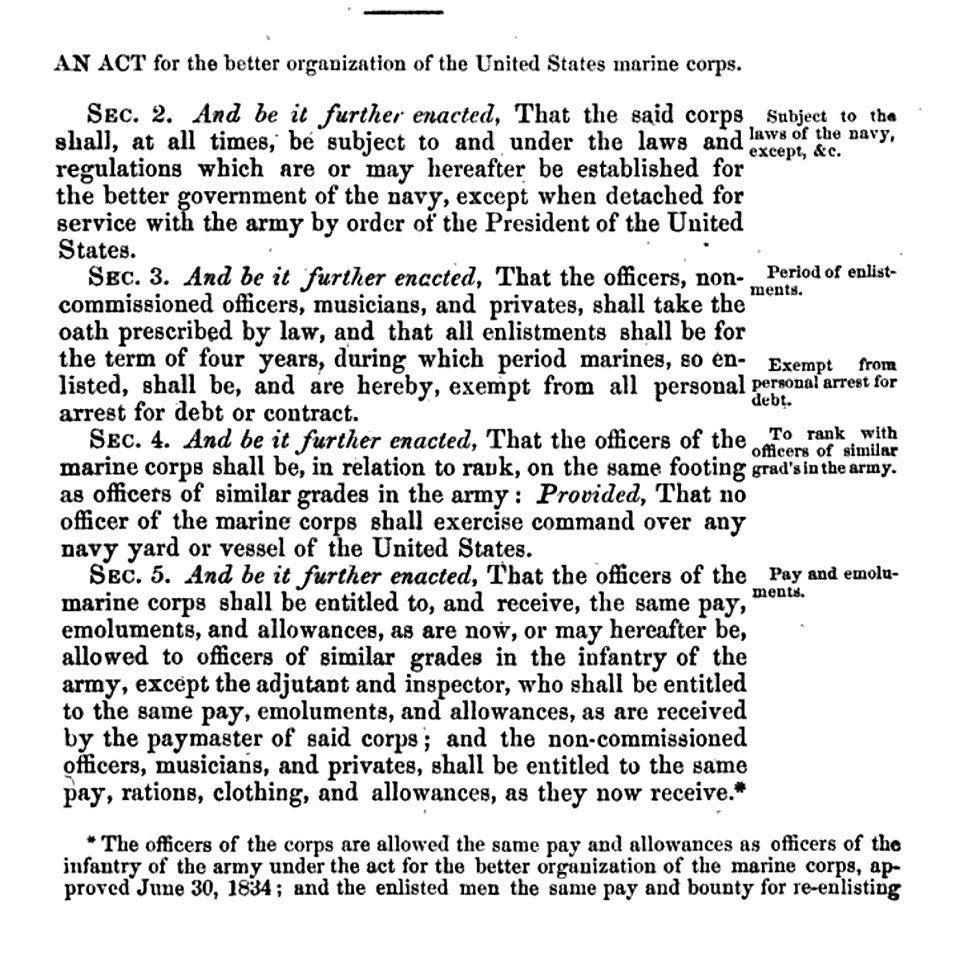

In 1829, Colonel Henderson went head-to-head with President Andrew Jackson, arguing against the president’s desire to combine the U.S. Army and Marine Corps for economic and organizational reasons. Jackson addressed Congress, “I would also recommend that the Marine Corps be merged in the artillery or infantry . . . that corps has, besides its lieutenant-colonel commandant, five brevet lieutenant-colonels, who receive the full pay and emoluments of their brevet rank.” Congress disagreed and in 1834 passed An Act for the Better Organization of the United States Marine Corps. The act stipulated that the Corps “shall, at all times, be subject to, and under the laws and regulations which are, or may hereafter be, established for the better government of the navy, except when detached for service with the army by order of the President of the United States.”[2] Henderson died in 1859 after serving as Commandant for 39 years. His leadership helped the Marine Corps evolve from a small fighting force to a formidable, reliable, and independent Service.[3]

An Act for the Better Organization of the United States Marine Corps, 37th Cong., 1st sess., ch. 19, 25 July 1861.

Henderson’s successor, John Harris, was commissioned in the Marine Corps in 1814. Like Henderson, he participated in the War of 1812. As a young second lieutenant, Harris witnessed the bombing of Fort McHenry in Baltimore, Maryland, in September 1814. He wrote in a letter home, “I think the handsomest sight I ever saw was during the bombarding to see the bombs and rockets flying from our three forts . . . the firing continued for over twenty hours.”[4] Fortunately for Harris, this was the extent of his combat experience. The majority of his military career was spent aboard ships and on barracks duty, mainly in the northeast. On 7 January 1859, Harris was appointed Commandant of the Marine Corps. He was 68 years old and had already served in the Marine Corps for nearly 45 years, making him the Service’s most senior officer.[5] However, Harris’s lack of field experience left much to be desired in terms of leadership. To many of the Marines he led, he was seen as an older, overweight officer who garnered little respect from those under his command. But the American Civil War soon brought Harris a chance to prove his—and the Corps’—fighting capabilities.

Col John Harris, 6th Commandant of the Marine Corps.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

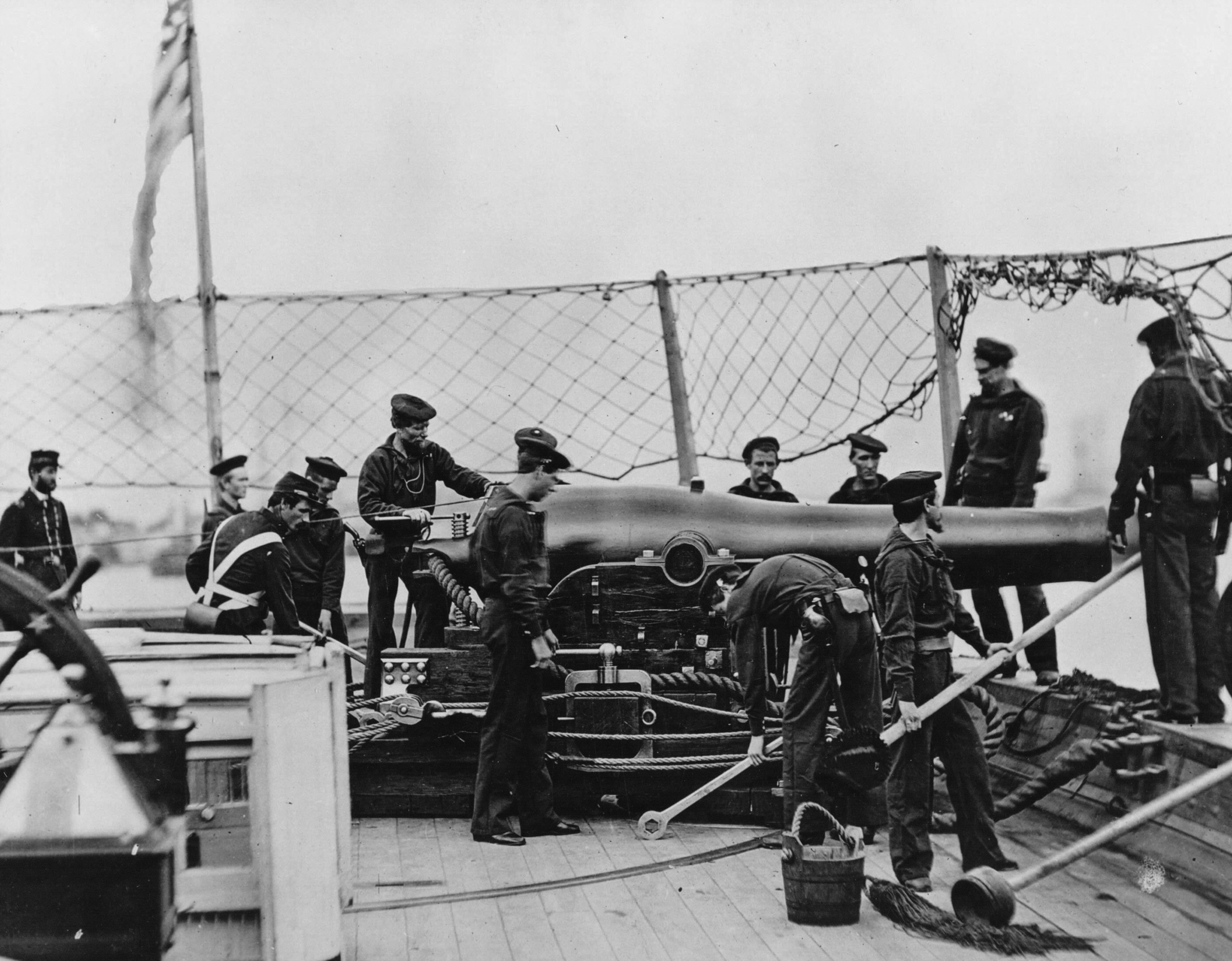

On 19 April 1861, President Abraham Lincoln issued Proclamation 81, declaring a blockade of all ports in South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, and Texas. One week later, Lincoln amended the proclamation to include Virginia and North Carolina.[6] The U.S. Navy was subsequently responsible for protecting more than 3,500 miles of shoreline. The Navy’s fleet grew from 42 vessels to nearly 700, and its fighting force grew from 11,000 to 50,000 strong.[7] In 1860, the Marine Corps included 46 officers and 1,755 enlisted. By the end of the Civil War in 1865, that number had more than doubled to 3,860-87 officers and 3,773 enlisted.[8] By comparison, in May 1865 the U.S. Army was comprised of approximately 1 million soldiers.[9] Commandant Harris was presented with an opportunity to develop the Marine Corps into an amphibious assault force. Instead, he remained steadfast in retaining Marines on guard duty aboard Navy ships. His decision was warranted.

A shipboard Marine assists his fellow sailors in loading a 9-inch Dahlgren smoothbore gun on a slide-pivot mounting aboard a U.S. Navy gunboat during the Civil War.

Naval History and Heritage Command.

Part of the Marine Corps’ challenges in the latter half of the nineteenth century was the longstanding “good ole boy” mentality. Commissions were rarely earned; instead, they were offered through nepotism or political ties. Additionally, performance incentives were essentially nonexistent. Officers’ pay had not increased since 1798, and promotions were few and far between. In the book The History of the United States Marine Corps, author Allen R. Millett explains, “In 1860 the most junior captain had eighteen years of service and the most senior captain thirty-nine.”[10] As such, individual Marines desired little more obligations than they already had, especially since they were not going to be compensated for going above and beyond. As a small force, the Marines performed their shipboard guard duties admirably and continued to do so throughout the Civil War, with limited time on shore as part of landing parties and occupying forts and towns captured by Union forces.[11]

A Marine officer and five enlisted Marines with fixed bayonets, photographed outside the Washington Navy Yard in April 1864.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Furthermore, Harris avoided volunteering Marines for assignments that more closely aligned with the Army. The Marines had thwarted attempts by both Congress and the president to combine the forces before, and they did so again in 1863. Harris wrote to Navy rear admiral David D. Porter on 1 December 1863, “Sir: In consequence of an effort which I understand it about to be repeated at an early day during the ensuing session of Congress . . . to transfer the Marine Corps to the Army as an additional regiment . . . Will you be so good as to give me your opinion as to the necessity for and the efficiency of marines on shore and afloat in connection with the Navy!”[12] Porter responded, “A ship without Marines is like a garment without buttons.”[13] Harris fought the same fight as his predecessor, Henderson, and was too able to prove the Marine Corps’ efficacy.

Commandant Harris died in office on 12 May 1865, having served in the Marine Corps for more than 50 years. While his tenure as Commandant was short, Harris effectively led the Corps through some of the nation’s most turbulent years, maintained the Corps’ autonomy from the Army, expanded the Corps’ numbers, and pushed his Marines to excel at their shipboard duties. Harris’s leadership helped mold the Marine Corps into the Service it is today.[14]

CMC John Harris’s full dress coat.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

This 1859 full dress double-breasted frock coat was worn by Colonel Harris during the Civil War. When he assumed duties as Commandant, he wore the uniform of his actual rank (colonel) and not the special Commandant uniform prescribed in the 1859 regulations. A Commandant’s coat would have “two rows of large size marine buttons on the breast, eight in each row, placed in pairs.”[15] Field officer’s coats similarly had eight buttons in each row, but these were spaced equal distances, as seen on Harris’s coat. Marine Corps uniform regulations were updated in 1859, though Harris’s coat carried over several aspects of the earlier 1834 variations, such as the vellum lace arrangement on the collar and sleeves as well as the cuff loop positions.[16]

An excerpt from the 1859 Marine Corps uniform and dress regulations showing various officer uniforms.

Regulations for the Uniform and Dress of the Marine Corps of the United States, October 1859 (Philadelphia, PA: Charles DeSilver, 1859).

The coat denotes Harris’s rank with oversized bullion fringe on the shoulder epaulets featuring an infantry horn and colonel insignia, as well as ornate braiding on the cuff of each sleeve. Due to Harris’s size, the front of the coat had been extensively altered during his career to allow its continued use. This complete uniform is one of the earliest officer uniform artifacts at the National Museum of the Marine Corps.

Close-up images of Col Harris’s shoulder epaulets featuring an infantry horn, colonel insignia, and oversized bullion fringe.

Photos by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

Endnotes

[1] “Famous Quotes,” Marine Corps History Division, accessed 13 May 2024.

[2] An Act for the Better Organization of the United States Marine Corps, 37th Cong., 1st Sess., ch. 19, 25 July 1861.

[3] “Colonel and Brevet Brigadier General Archibald Henderson, USMC,” Marine Corps History Division, accessed 13 May 2024.

[4] Letter from John Harris to William Harris, 17 September 1814 (War of 1812 Collection, Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore, MD).

[5] “Colonel John Harris, USMC,” Marine Corps History Division, accessed 13 May 2024.

[6] Abraham Lincoln, “Proclamation by the President of the United States of America on Blockade of Confederate Ports,” 18 April 1861 (Alfred Whital Stern Collection of Lincolniana, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC).

[7] Allan R. Millett, Semper Fidelis: The History of the United States Marine Corps (New York: Free Press, 1991), 91.

[8] “End Strengths, 1795–2015,” Marine Corps History Division, accessed 13 May 2024.

[9] David Vergun, “150 Years Ago: Army Takes on Peacekeeping Duties in Post-Civil War South,” U.S. Army, 4 August 2015.

[10] Millett, Semper Fidelis, 87.

[11] Millett, Semper Fidelis, 92.

[12] Letter from Col John Harris to Adm David D. Porter, 1 December 1863, in Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, ser. 1, vol. 25, Operations: Naval Forces on Western Waters, May 18, 1863–February 29, 1864 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1912).

[13] “Famous Quotes,” Marine Corps History Division, accessed 13 May 2024.

[14] “Colonel John Harris, USMC.”

[15] Regulations for the Uniform and Dress of the Marine Corps of the United States, October 1859 (Philadelphia, PA: Charles DeSilver, 1859).

[16] LtCol Charles H. Cureton, USMCR (Ret), and David M. Sullivan, The Civil War Uniforms of the United States Marine Corps: The Regulations of 1859 (San Jose, CA: R. James Bender Publishing, 2009), 78.