Chapter 2

The First Shots of World War I

Marines in Guam

By Jonathan Bernstein, Arms and Armor Curator

Featured artifact: Subcaliber Training Gun (2022.1.1)

When thinking about U.S. involvement in World War I, our collective memory tends to focus on the trenches of Belgium and France rather than remote islands in the Pacific. However, the first American shots in that conflict were fired not by U.S. Army soldiers in France, but by U.S. Marines on Guam within 24 hours of war being declared.

This story begins at the outset of the war in July 1914. With the opening of hostilities in Europe, the German East Asia Squadron based in Tsingtao, China, was tasked with raiding Allied merchant shipping. Within a week, the light cruiser SMS Emden (1916) captured the German-built, Russian-owned freighter M/V Ryazan, taking it in tow and returning to Tsingtao. The Ryazan had been built in Elbing, Germany, in 1909 with a secondary armed capability built into its design. When the Germans captured the Ryazan, they had a ready platform to mount the eight 10.5-centimeter guns pulled from the cruiser SMS Cormoran (1909), which was dead in the water back in port.

The Cormoran’s eight 10.5-centimeter SK L/35 fast-loading cannons were transferred to the Ryazan, which was then commissioned in the Imperial German Navy as the SMS Cormoran, taking the older ship’s name and crew, and setting off as an “auxiliary cruiser” intent on harassing enemy shipping in the Pacific. While the second Cormoran presented a significant threat to merchant shipping, it lacked the armor protection that was standard on warships of its size. As a result, when faced by British, Dutch, or Japanese warships, the Cormoran’s captain, Adalbert Zuckschwerdt, elected to run and hide in the safety of several harbors across the Pacific rather than risk losing his ship to a superior force.

However, playing a game of cat and mouse across the Pacific was a significant logistical challenge, and by December 1914, Captain Zuckschwerdt was critically low on coal to fuel his ship’s boilers. Early in the month, he sent three officers in a smaller boat to Guam, a possession of the then still-neutral United States, to inquire about being refueled by the facilities there. Prior to the outbreak of hostilities, German vessels routinely refueled at Apra Harbor, but once the war began, refueling a belligerent nation’s ship could be seen as breaking neutrality. As a result, the naval governor of Guam, U.S. Navy captain William J. Maxwell, refused, telling the three German officers that they were now guests of the United States and were not permitted to leave. With his officers overdue and coal supplies dwindling, Captain Zuckschwerdt made the decision to head to Guam.

The Cormoran entered Apra Harbor on 15 December, and Captain Zuckschwerdt was informed that there was no coal available to any but U.S. shipping. Having narrowly avoided engaging Japanese warships en route, the Germans were safe for the time being. Two days after their arrival, “the Japanese cruiser Iwate, flying the flag of Vice Admiral Matsumura Uichi, stopped at the harbor entrance just outside the three-mile limit to inquire about the status of the Cormoran. Governor Maxwell sent out a small party to advise the Japanese that the Cormoran was interned and would remain so until the end of the war. Satisfied, the Japanese left.”[1]

The Russian freighter M/V Ryazan was quickly captured by the Imperial German Navy and refitted as a commerce raider in the German-held port of Tsingtao in August 1914. Despite its crew’s best efforts, most of its time at sea from August to December 1914 was spent dodging Japanese naval patrols rather than engaging Allied shipping.

National Museum of the Marine Corps.

Apra Harbor was a critical hub for U.S. Navy vessels operating in the Pacific. With the outbreak of war in the summer of 1914, the United States maintained a neutral footing and therefore refused to refuel warships of any belligerent nations. The Cormoran’s arrival in December 1914 put that policy to the test and resulted in the internment of the ship and its crew for the duration of the war.

Marine Corps History Division.

With a crew of nearly 300, the Cormoran presented a dilemma for Governor Maxwell. At the time, the Marine garrison on Guam numbered just more than 350 Marines, with an additional 70 Navy personnel. A potentially hostile warship with a crew rivaling the garrison’s strength sitting at anchor could have presented a significant threat, so the Cormoran was quickly disarmed. Its 10.5-centimeter guns were a significant improvement over the island’s 30-year-old 6-inch guns. Those guns and their associated equipment were relocated to bolster Guam’s defenses. In addition, the ship’s armory was also cleared out and all small arms moved to the Marines’ armory on the island.

One of the weapons taken from the Cormoran was an oddly assembled device built around an 1871 Jaegerbuchse rifle action and chambered for 11mm x 60 ammunition. At the rifle’s muzzle was a 10.5-centimeter disk designed to fit precisely into the bore of one of the Cormoran’s deck guns; the rear flange in front of the receiver would then be bolted to the gun’s breech. This subcaliber training device, known as an Abkomm Lauf neue Artikel (Abkomm-Lauf n/A), was a training device that enabled gun crews to practice targeting, loading, and engaging with a projectile of similar ballistics but without wasting precious main gun ammunition and corresponding wear on the gun tube. The original Jaegerbuchse 71 serial number 5405 is located on the forward left portion of the receiver, with the new serial number for the Abkomm-Lauf n/A, 27, added to the top of the receiver and stamped on all the additional parts as well.

With the Cormoran’s main guns now moved ashore, the Marines were responsible for training, crewing, and employing them against potential seaborne threats to the island. The Abkomm-Lauf n/A was a critical piece of that training, since resupply of the German 10.5-centimeter ammunition would be impossible and there was plenty of 11-millimeter ammunition for the Marines to train and familiarize with their new coastal defense guns.

The Abkomm Lauf n/A was used to train gun crews on the proper procedures for loading, aiming, and firing the Cormoran’s eight 10.5-centimeter SK L/35 guns. The weapon’s barrel would be inserted into the larger gun’s breech, with the muzzle disk properly holding the barrel within the gun tube. It would next be secured to the gun’s breech and then loaded and fired.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

The weapon was based around the rifle action of a Model 1871 Jagerbuchse; this example being built in 1876. Once inserted into the larger gun’s barrel, the training device would be integral in teaching gun crews the proper procedures for loading and firing, without the expenditure of main gun ammunition or wear and tear on the barrel.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

While Marine defense battalions would not exist until just prior to World War II, the primary functions of the 40th, 41st, and 42d Companies of Marines ashore on Guam were to serve as the island’s coastal defense force and infantry force to defend it from invasion. In addition to those duties, the Marines also served as the backbone of Guam’s police force, with the Marine battalion executive officer serving as the chief of police for the island’s nearly 12,000 inhabitants.

A company of Marines at Tenjo Camp, Guam, 1915.

Marine Corps History Division.

The Marines served as the police force on Guam and manned several patrol stations like this one across the island.

Marine Corps History Division.

For the next 18 months, Governor Maxwell and Captain Zuckschwerdt maintained an adversarial relationship. Maxwell, who was known for being confrontational, often chose to stoke the tension between the two of them to the point where they would no longer speak directly with one another. Keeping the Cormoran and its crew provisioned fell under Maxwell’s responsibilities, as did allowing the crew to communicate with Germany’s diplomatic corps. Initially the U.S. State Department frequently overruled Maxwell’s decisions when Zuckschwerdt would file formal complaints, but as tensions grew between the United States and Germany, that began to change. Maxwell fell ill in 1916, though, and he was soon replaced as governor of Guam by a quick succession of three different naval officers.

With Maxwell gone, local tensions eased significantly, and the Germans were treated more as guests than internees. Relations between the Cormoran’s crew and the local government continued to improve through the latter half of 1916. The crew was free to come ashore for supplies and entertainment. The year culminated with the wedding of the Cormoran’s doctor to one of the American nurses based on the island.

As the new year turned, however, it was clear that the United States and Germany were headed toward war. The U.S. military presence on Guam had been bolstered by an additional 100 Marines, bringing the total to 463 Marine with an additional 100 Navy personnel. The Cormoran’s crew was not considered a significant threat, but they could become one if Germany sought to expand its territorial claims in the Pacific. The islands of Saipan, Tinian, and Rota were all German possessions and could potentially serve as staging points for German expansion in the Pacific. If that happened, Guam would likely be the first target.

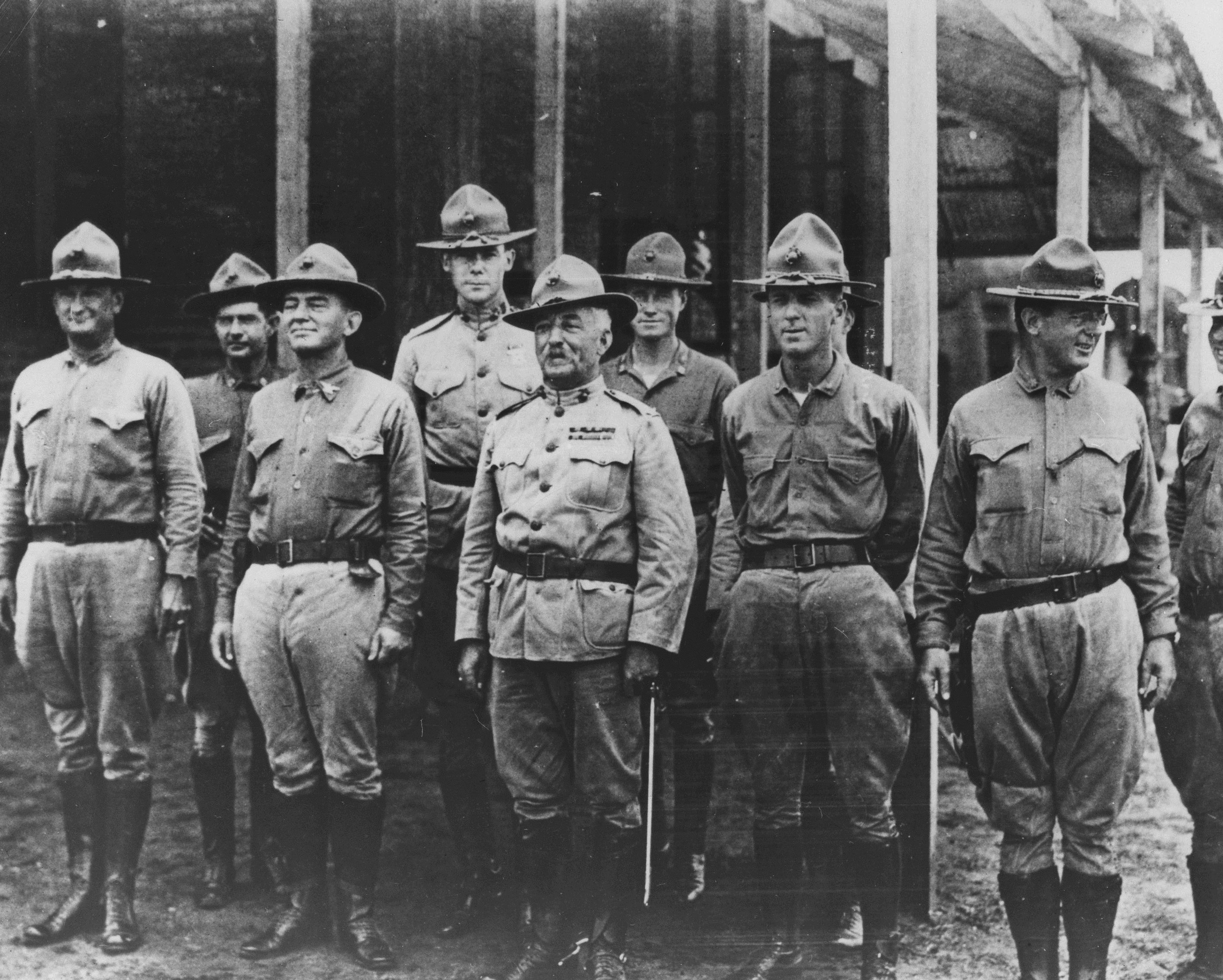

The Marine commander on Guam, Lieutenant Colonel Randolph C. Berkeley, had overseen the island’s defenses since arriving in May 1915. Berkeley was a combat veteran of the Battle of Veracruz, Mexico, where he had earned the Medal of Honor in 1914, as well as having served in the Philippines and Cuba in the early twentieth century.

Veracruz, Mexico, 1914. In the front row at right is LtCol Randolph C. Berkeley, next to Maj Smedley D. Butler. Col John A. Lejeune is second from left. Berkeley was awarded the Medal of Honor at Veracruz in 1914 and later the Navy Cross for efforts in Nicaragua in 1922. After Veracruz, he was posted to Guam as the Marine commander on the island.

Marine Corps History Division.

Berkeley initiated a complete revamping of Guam’s defense plan shortly after his arrival. Defensive positions were improved, gun emplacements were reinforced, and the training tempo was increased. By early 1917, with the threat of war on the horizon, he put the local population on notice that all males from ages 16 to 23 would be required to serve in the island’s militia.[2] On 3 February, the new naval governor, Captain Roy C. Smith, ordered the militia to report for their first training under Berkeley. Nearly 1,000 men reported for duty. School-age boys were also required to participate in physical training in the mornings before school to prepare them for future service. Were war to come to Guam, the U.S. now had a force of nearly 1,500 men to repel invaders. In addition to instructing the new militiamen in military customs, courtesies, and drill, Berkeley used the German weapons seized from the Cormoran to outfit them and trained them in rifle marksmanship, the employment of machine guns, and the operation of the eight 10.5-centimeter guns now strategically positioned on the island to defend its approaches. The Abkomm-Lauf n/A was a critical part of this training and allowed the militiamen to learn their new weapons without wasting precious ammunition.

Also on 3 February, a new confrontation with Captain Zuckschwerdt and his crew arose after many months of pleasantries. Governor Smith dispatched U.S. Navy lieutenant Owen Bartlett and another officer to inspect the Cormoran’s coal reserve. Zuckschwerdt refused them, stating that the ship was still sovereign German property and not subject to Guam’s orders. Bartlett returned to Smith with the negative reply. As Bartlett later recounted:

When this was received by the governor, he quietly dictated an order from the “military commander of Guam” to the captain of the Cormoran demanding that the latter permit the inspection. Also, the colonel of Marines was directed to muster his force at Piti immediately, and all small craft were assembled there preparatory to enforcing if need be the governor’s demand. Things were getting tense. And this all took time.[3]

LtCdr Owen Bartlett with his father, Capt Frank Bartlett, and younger brother, Ens Bradford Bartlett, in 1922. Owen Bartlett presented Capt Zuckschwerdt of the Cormoran with the surrender demand on 7 April 1917.

Naval History and Heritage Command.

Lieutenant Colonel Berkeley assembled his boarding force, complete with cannons, at Piti and prepared to take the Cormoran while Bartlett returned to the ship a second time. Zuckschwerdt again refused the inspection, and Bartlett went back to shore to telephone Smith. Smith’s reply was curt: “Very well Bartlett! Confer with Colonel Berkeley. Go out and take the ship.”[4]

Seeing the approaching boarding force with Bartlett in the lead boat, Zuckschwerdt capitulated, allowing Bartlett and two others to inspect Cormoran’s coal bunkers. The total amount of coal on board was within acceptable limits, and the situation ended without further incident. That night, Guam received a cable from the United States informing the governor that diplomatic relations with Germany had been severed. War looked inevitable.

On 7 April, an early morning coded telegraph message from the United States informed Guam’s garrison that war had been declared on Germany and that the Marines should seize the Cormoran and its crew. Having been summoned to the governor’s residence and tasked with accepting the ship’s surrender, Lieutenant Bartlett was on the governor’s launch and headed to the Cormoran just before 0800 under a flag of truce. Supporting him was a beach detachment of Marines with machine guns and cannons targeting the Cormoran and three companies of Marines standing by. As the Marines took their positions, the Navy’s station ship, USS Supply (1872) moved to block the entrance to Apra Harbor in case the Germans attempted to escape.

Fifteen Marines were tasked with taking control of the Cormoran once it surrendered. They were aboard a separate launch from Bartlett and were approaching the ship from a different angle when they noticed one of the Cormoran’s launches headed away from the ship. Lieutenant W. A. Hall, the Navy officer aboard, ordered Marine corporal Michael B. Chockie to fire a warning shot across the launch’s bow to get it to stop. When Chockie’s warning had no effect, Hall ordered two more shots fired with the same results. It was not until the third volley, this time aimed directly at the bow and stern of the launch, that the Germans finally shut down their engines and stopped. The Great War had come to Guam, and the Marines had fired the opening volley.

The exchange that followed between Bartlett and Zuckschwerdt was one of mutual respect but clear defiance on the German’s part. Zuckschwerdt explained that he would surrender his crew, but the ship was unarmed and defenseless and would not be surrendered. The two officers reiterated their positions, and Bartlett finally left without the ship’s surrender. As Bartlett boarded his launch and turned to signal the operation to commence, there was a significant commotion on the deck and the crew began jumping into the water. As Bartlett remembered:

We had gone toward Piti at full speed perhaps a hundred yards and were just well clear of the bow, when there came the dull heavy shock of muffled under-water explosion. Red flames with little smoke shot up around the bridge of the Cormoran; pieces of debris rose, arched, fell; the bridge and region of the captain’s cabin popped up, crumpled, collapsed.[5]

Zuckschwerdt had initially refused to allow the inspection on 3 February to conceal a gasoline bomb that his crew had constructed in the coal bunker as a contingency if they were forced to surrender the ship. During its more-than-two-year stay in Apra Harbor, the Cormoran’s crew had built up a large enough reserve of gasoline that could be used as a scuttling charge. Faced with no alternative, the captain ordered his ship scuttled. The ship sank in just a few minutes in more than 30 meters of water.

Seven German sailors were killed in the ensuing blast, but the Marines and the Supply recovered 353 of the Cormoran’s crew, including Captain Zuckschwerdt. The Germans were moved to two separate locations on Guam in temporary prison camps administered by the Marines, with the crew near the beach at Asan and the officers at Camp Barnett on Mount Tenjo. Their stay at these locations would be short-lived. Three weeks after the scuttling of the Cormoran, its crew was loaded aboard the U.S. Army transport ship USAT Thomas (1894) and sailed for the United States, where they would spend the rest of the war at a prisoner-of-war camp in Utah.

Three years later, after World War I had ended and as awards for the war were being reviewed, Captain Smith recommended both Lieutenant Colonel Berkeley and his executive officer, Major Edward R. Manwaring, for the Navy Cross for their extremely meritorious service in improving the defenses of Guam, creating its militia, and using the weapons taken from the Cormoran to arm the militiamen. Unfortunately, the awards were denied, and it would be an additional seven years before Berkeley would receive his Navy Cross in Nicaragua.

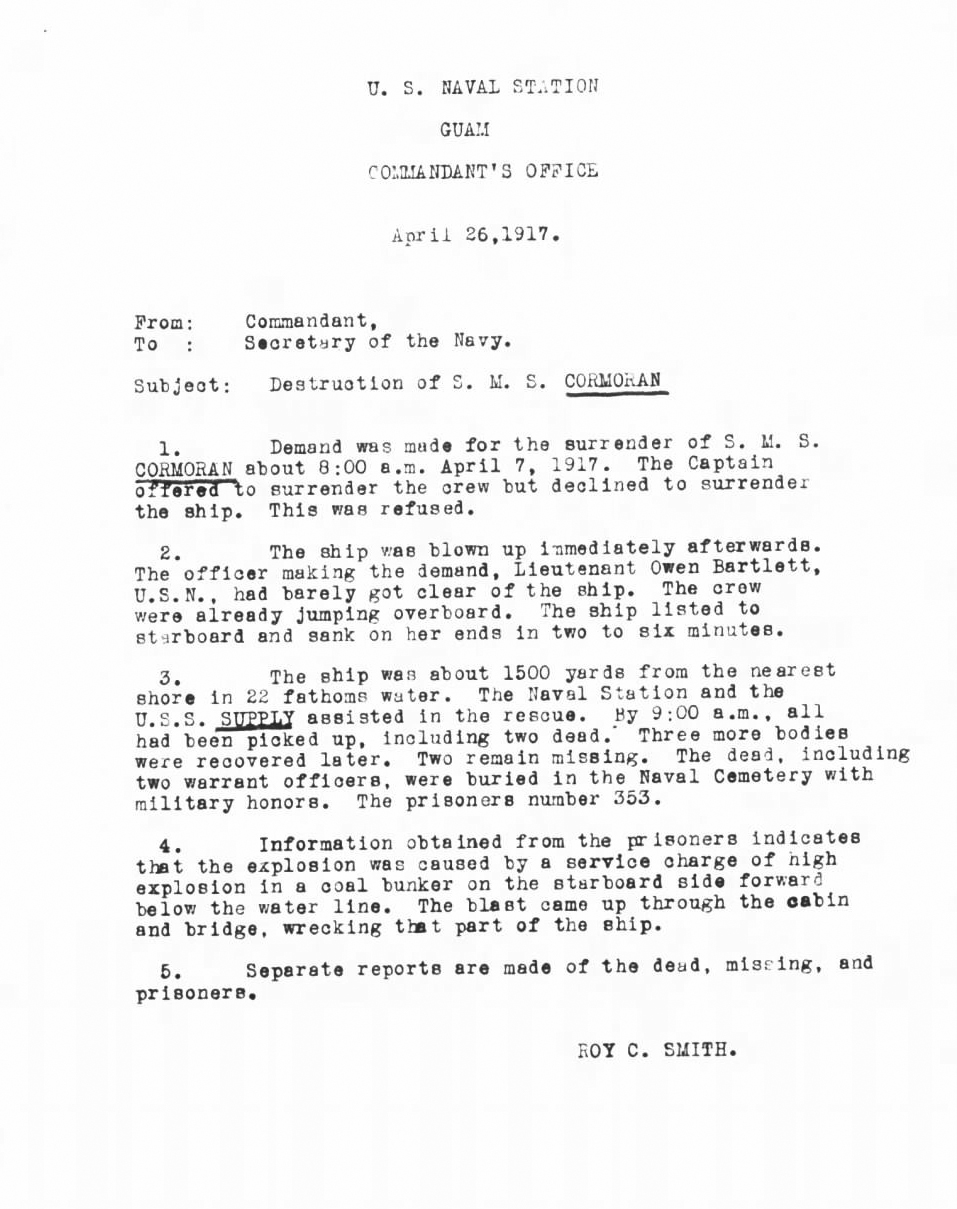

Capt Smith’s communique to the Secretary of the Navy detailing the destruction of the Cormoran.

National Archives and Records Administration.

Unfortunately, the chain of custody that led the Abkomm Lauf n/A to be a part of the National Museum of the Marine Corps’ collection (NMMC) is unclear. It was brought to the United States between 1918 and 1941 and held as part of the Marine Corps historical collection. However, during this time, its history was forgotten, and it sat in storage in relative obscurity until the German naval historian Michael Heidler properly identified it as having been part of the Cormoran’s weapons complement. Heidler was able to cross-reference records at the German Navy Museum in Wilhelmshaven, Germany, and confirm that it was issued to the Cormoran. His article, “The Last of its Kind?” published initially in the South African Society for Military History’s Military History Journal in 2012, led to renewed interest in the weapon and formal acceptance into the NMMC collection.[6]

A close-up of the Abkomm Lauf n/A’s receiver shows the serial number 27, butterfly screws that would be used to secure the device to the breech of the 10.5-centimeter gun, and the trigger lever (left) to which the gun’s lanyard would be affixed for firing.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

While this weapon may be the last of its kind, the historic significance of its presence at the site of the first American shots fired at German forces in World War I helps the NMMC paint a far more complete picture of the Marine Corps involvement in that global war.

endnotes

[1] Paul Carano and Pedro C. Sanchez, A Compete History of Guam (Rutland, VT: C. E. Tuttle, 1964), 215–19.

[2] Roy C. Smith, “Recommendations for Navy Crosses for Exceptionally Meritorious Services in Duties of Great Responsibility in the Island of Guam during the War,” Correspondence with the U.S. Secretary of the Navy, 17 December 1920.

[3] Cdr Owen Bartlett, USN (Ret), “Destruction of S.M.S. ‘Cormoran’,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 57, no. 8 (August 1931).

[4] Bartlett, “Destruction of S.M.S. ‘Cormoran’.”

[5] Bartlett, “Destruction of S.M.S. ‘Cormoran’.”

[6] Michael Heidler, “The Last of Its Kind?: A Rediscovered Training Device of the German Imperial Navy,” Military History Journal 15, no. 6 (December 2012).