Chapter 18

A Marine Less Ordinary

The Life of Major General Smedley D. Butler

By Owen Linlithgow Conner, Chief Curator

Featured artifacts: Coat, Dress, Blue, Officer (1999.42.111); Medal, Medal of Honor, Navy (1999.42.99); Medal, Medal of Honor, Navy (1999.42.100); and Medal Bar (including Navy Distinguished Service, Army Distinguished Service, Brevet, Sampson West Indies with USS Resolute bar, West Indies Campaign, Philippine Campaign, China Relief Expedition, Marine Corps Expeditionary, Nicaraguan Campaign, Mexican Service, Haitian Campaign, Dominican Campaign, World War I Victory, Yangtze Service, and Haitian Medaille Militaire) (1999.42.40)

In the 250-year history of the U.S. Marine Corps, there have been many colorful, highly decorated Marines. Few, however, compared to Major General Smedley D. Butler. From his unusual name to his unusual career, Butler was a Marine like no other.

MajGen Smedley D. Butler served in the U.S. Marine Corps from 1898 to 1931.

Marine Corps History Division.

Butler’s officer dress blue uniform coat.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

Smedley Darlington Butler was commissioned in the Marine Corps in 1898 at the age of 16. Two years later, he was promoted to the rank of captain by brevet for his heroic conduct during the Boxer Rebellion in China. He served in nearly every campaign of the Marine Corps from 1898 to 1931[1]. His first Medal of Honor was awarded in 1914 for “distinguished conduct in battle” during the U.S. occupation of Veracruz, Mexico.[2] His second Medal of Honor came less than two years later, when he led an attack on Fort Riviere, Haiti. Butler was one of only two Marines to receive two Medals of Honor.[3]

Butler is the only Marine officer to receive two Medals of Honor during his career.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

The reverse inscription to Butler’s first Medal of Honor.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

The reverse inscription to Butler’s second Medal of Honor.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

Butler’s valor, campaign, and service medals.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

While combat evaded him in World War I, Butler was highly decorated for his command of Camp Pontanezen near Brest, France. He became a brigadier general at age 37 and a major general at age 47. Between promotions, he spent two years on leave while serving as the director of public safety for the city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, during the worst of Prohibition. A return to China in 1927 saw the culmination of a long career. But even in retirement, Butler’s life was far from ordinary.

Outside of his “traditional” Marine Corps service, Butler added to his status. A passionate sportsman, he developed and fielded athletic teams and even constructed his own stadium at the Marine Corps barracks in Quantico, Virginia.[4] He was often seen in the stands, megaphone in hand, cheering his Marines on.[5] While sometimes disdainful toward the intellectual side of military strategy, he was a champion of the use of new field equipment, mechanized vehicles, and aircraft on the battlefield.[6] Butler famously took his Quantico Marines on several long maneuvers to Civil War battlefields in Virginia and Pennsylvania. During his 33-year career, Butler earned a handful of colorful nicknames, including “The Fighting Quaker,” “Maverick Marine,” “Old Gimlet Eye,” “General Duckboard,” and the “Fighting Hell-Devil”—each well-earned with their own colorful stories.[7]

Early Days

Smedley Darlington Butler was born on 30 July 1881 in West Chester, Pennsylvania.[8] Raised as a Hicksite Quaker, his father, Thomas S. Butler, served as a local lawyer and then judge before being elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1897. Serving the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania for 32 years, the elder Butler chaired several important committees, including the Committee on Naval Affairs for 10 years in 1919–28). He remained in office until his death in 1928.[9]

When the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898, Smedley Butler was just 16 years old. Inspired by a parade of the 6th Pennsylvania Volunteers, he became desperate to enter military service. The teenage Butler seized his chance when he overheard his father telling his mother that Congress had just approved the recruitment of 43 new U.S. Marine Corps officers. Smedley informed his mother that he would hire a stranger to impersonate his father if she did not grant her parental consent for him to join the Corps. Reluctantly, Maud Butler traveled to Washington, DC, with her son. Fortunately for the strong-willed Butler, two key factors aided his effort to enlist at 16. The first and most significant was the friendship of the Commandant of the Marine Corps, Colonel Charles Heywood, with his father. The second was the rather curious fact that Congress had set no age limit for men applying for new commissions.[10] With his parents’ eventual consent, Smedley Butler was officially commissioned as an officer in the Marine Corps on 20 May 1898.

Butler (standing third from left), as a young lieutenant, poses with fellow Marine officers. Several of the older Marines had served in the American Civil War.

Marine Corps History Division.

Butler’s first proper introduction to the Marine Corps came with his deployment to Cuba. On 10 June 1898, Lieutenant Colonel Robert W. Huntington landed with a battalion of Marines on the beach at Guantanamo Bay. Entrenched on the high ground, they were subjected to constant harassment from Spanish guerrillas. Sometime later, Butler and a small group of fresh young lieutenants were sent to reinforce them. Arriving by boat from the armored cruiser USS New York (ACR 2), Butler formally reported to a group of bedraggled veterans asking to meet with Huntington. Chiding the welcoming committee for their lack of respect toward officers, Butler was soon shocked to learn that the white-bearded Marine they had scolded was none other than the colonel himself. Many of these veteran officers had served in the Marine Corps since the American Civil War. As Butler organized the veteran Marines under his command, he began to take full stock of their bravery and professionalism. He came under sporadic but ineffective fire for the first time and took extensive mental notes of the standards he would now be expected to live up to. By the time of the Spanish surrender on 13 August 1898, he was relieved, but he was now fully aware of the true “spirit of the Corps.”[11]

Butler’s next adventure took place in China in 1900. At the turn of the twentieth century, European powers and the United States maintained a strong trading presence in China. The individual nations’ spheres of influence added to the already problematic issues of a fractured nation. As a response, a secret Chinese society was formed in 1897. Called I Ho Chaun (The Fists of Righteous Harmony), or more colloquially the “Boxers,” they set about attacking foreign influences and Chinese Christians. The fighting reached a climax in 1900, when the Chinese empress expressed her open support for the organization. The Boxers laid siege to foreign settlements in the cities of Peking (Beijing) and Tientsin (Tianjin). In response, the foreign powers rushed reinforcements to China to support their communities. The Unites States deployed U.S. Marines and soldiers to the effort. When the initial relief forces fought skirmishes with the imperial Chinese army, the situation grew even more dire.[12]

Additional Marine relief forces were summoned from the detachments on U.S. Navy warships as well as at Guam and Cavite, Philippines. First Lieutenant Butler, then serving with the Cavite detachment, was given the command of a company with Major Littleton T. Waller’s relief force. Their orders sent them to Tientsin in search of an earlier relief column. During the long march on the city, they were joined by Russian forces and Royal Welch Fusiliers. The fighting was heavy, and the Marines suffered casualties. When Private C. H. Carter was wounded and accidentally left behind by the relief column, Butler and First Lieutenant Arthur E. Harding led Privates Thomas W. Kates, Albert R. Campbell, Charles R. Francis, and Clarence E. Mathias to rescue him. The Marines carried their wounded comrade more than 25 kilometers back to their column. For their heroism, each of the enlisted Marines received the Medal of Honor, while Butler and Harding received battlefield brevet promotions to the rank of captain.[13]

Capt Smedley Butler’s U.S. Marine Corps Brevet medal.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

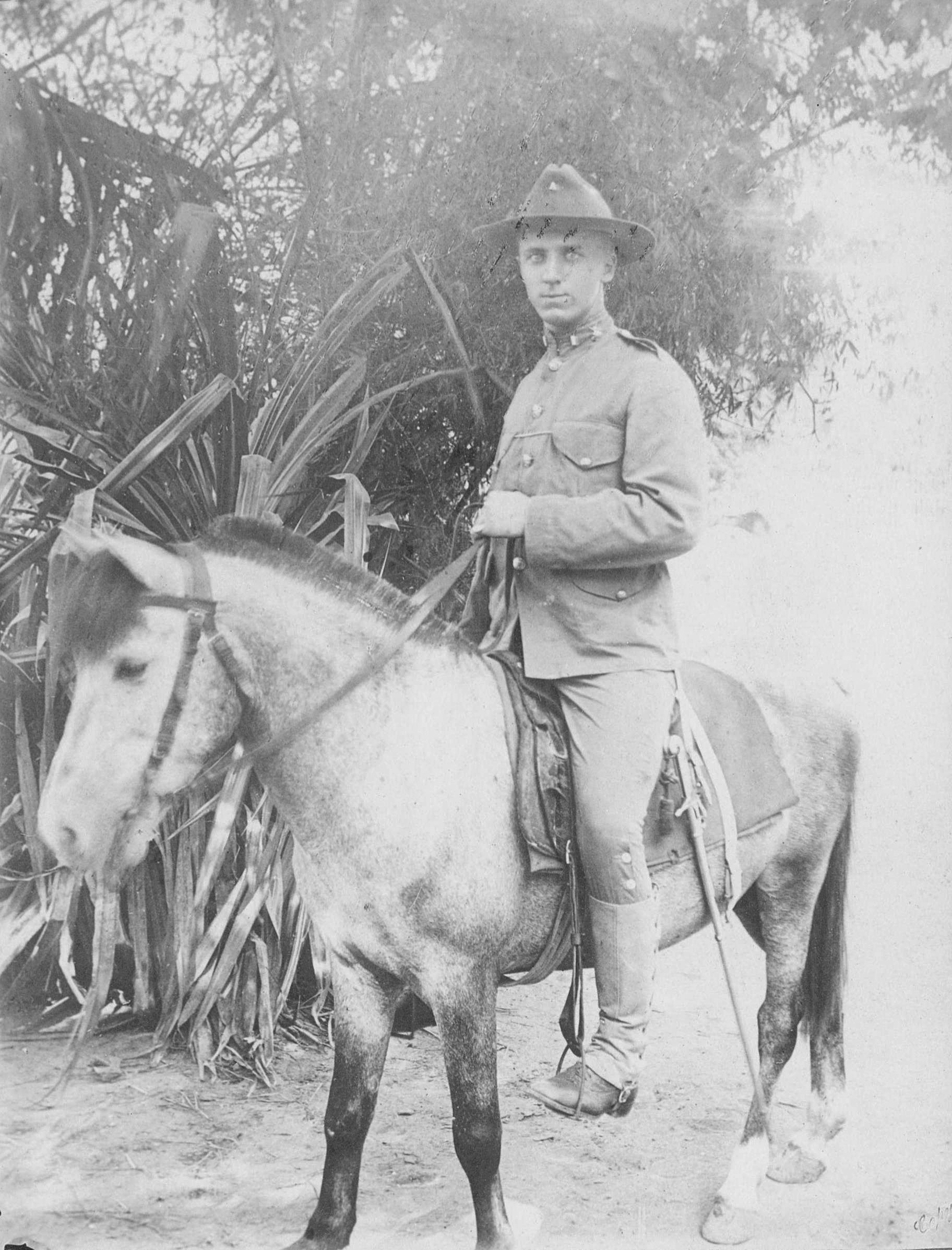

In 1899, Lt Butler was briefly assigned to duty with the Marine battalion at Manila, Philippine Islands.

Marine Corps History Division.

The 19-year-old Butler’s receipt of a brevet commission was a significant honor. The brevet award was a military tradition that dates to at least the seventeenth century. Employed by English royalty to promote civilians and the upper class, the simplified tradition carried over to the United States in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[14] The U.S. military adopted the practice of awarding brevet commissions, most notably for valorous conduct on the battlefield. When presented, the officer was usually advanced one or two levels of rank and granted a new commission.[15] At the time, this was the highest honor a Marine officer could receive, as Marine officers were not entitled to receive the Medal of Honor until authorized by Congress in 1915.[16]

Following the heroism of Private Carter’s rescue, Butler’s bravery continued. During the Battle of Tientsin, he was assisting in the recovery of a wounded Marine when struck by enemy rifle fire in the right thigh.[17] The wound was significant, but the bullet had missed the bone, so Butler was able to join his fellow Marines in their march on Peking.[18] As he led another attack through the city’s ancient Tartar Wall, he was struck again by Chinese fire. Awakening later in a small guardhouse, Butler’s rescuers thought that he had been shot through the heart. Thankfully, this was not the case. He was struck by a ricocheting enemy musket ball, which hit the second button of his uniform blouse. The flattened metal button saved his life but tore off a portion of his chest skin, where a large tattoo of the Marine Corps emblem was inked. Despite all this, Butler returned to action once more.[19]

More Interventions and Two Medals of Honor

After the eventual victory of the foreign powers in China, Butler returned to the United States in 1901. The following years entailed the command of various ship detachments on Navy warships as well as minor posts in the continental United States.[20] Overseas assignments to Puerto Rico, Panama, and Nicaragua provided Butler with additional experience in colonial warfare and a crash course in the complexities of international politics. His numerous adventures in Nicaragua involved a daring attack on the fortress of Coyotepe and a humorous story of him single-handedly swiping a pistol from a rebel general’s hand.[21]

The pattern of U.S. intervention in Central America reached a chaotic climax in 1914 following revolution in Mexico. The United States initially supported a military coup led by Mexican Army general Victoriano Huerta but then declined to recognize the government formed by his faction. Several international incidents, including the detention of U.S. Navy sailors, rising concerns from U.S. businesses with interests in Mexico, and a German attempt to deliver arms to the country, brought the crisis to a boiling point. Foreign settlements in Mexico City and oil interests in Tampico brought foreign military powers into the region, with a near repeat of an intervention not unlike that during the Boxer Rebellion.[22] As a result, U.S. president T. Woodrow Wilson sent special envoy John Lind to Mexico to develop plans for a full-scale American intervention.

At this time, Butler was given the opportunity to add spy to his already exotic resume. In an era lacking a U.S. national intelligence gathering network, Butler was enlisted to conduct regional reconnaissance in Mexico. He toured the country, alternately posing as a former Panama Canal Zone railroad employee, a city planner, a guidebook writer, and a naturalist.[23] This charade allowed him to visit Mexican Army units, installations, and forts to inspect their capabilities and arms in anticipation for a full-scale invasion of Mexico.

While the Lind-Butler invasion plan was never fully enacted, the military occupation of the Mexican port city of Veracruz did occur. Commencing on 21 April 1914, the armed intervention pitted U.S. Marines and Navy sailors against a mixture of retreating federal Mexican soldiers, hastily armed civilians, prison inmates, and cadets. The fighting lasted for several days. Originally charged with simply capturing the waterfront, the Americans eventually occupied the entire city.

By every measure, the occupation of Veracruz was an unusual and confusing moment in American military history. International politics, foreign business interests, and controversial decisions by U.S. Navy commanders left a complex narrative for future historians to untangle. Further muddying the waters were the suspect numbers of Medals of Honor awarded to officers and enlisted personnel for the minor action. With more than 50 awards conferred, officers who were ineligible to receive the prestigious award prior to 1915 benefited the most. Navy officers received the lion’s share of recognition, while nine Marines earned the honor. In the case of Butler, he was at least awarded the Medal of Honor for his courage and participation in the engagement, his citation noting his “distinguished conduct in combat” and “eminent and conspicuous command of his battalion.”[24]

In his autobiography Old Gimlet Eye, Butler made his displeasure in receiving the Medal of Honor clear. He mailed the award back to the U.S. Navy Department with a statement that he had done nothing to earn this “supreme decoration.” The medal, however, was soon returned to him with a letter from Rear Admiral Frank F. Fletcher insisting that he did deserve the award and that he was ordered to accept and wear it.[25]

Following his adventures in Mexico, Butler had little time to rest. Disagreements between Haitian and American banks over defaulted railroad construction loans caused tension between the two nations. Haitian soldiers occupied Haitian banks to prevent the U.S. seizure of the banks’ assets, and U.S. Marines landed to seize the gold reserves held in the Haitian National Bank to hold for collateral against the loans. Haiti’s strategic location near the Panama Canal and intertwinements with U.S. investors made yet another American intervention inevitable. Fighting between the minority French-speaking Haitian upper classes and the majority Creole-speaking lower classes brought constant dysfunction. As a result, on 28 July 1915, U.S. Marines and sailors landed at Port-au-Prince, seized the city, declared martial law, and arrested revolutionaries. When the Haitian National Assembly elected a new president, U.S. Navy rear admiral William B. Caperton refused to recognize the legitimacy of the elections and selected his own president of Haiti.[26]

The installment of a new Haitian government by the United States inflamed internal divisions on the island. Impoverished rebels living in the mountainous regions of the country began to fight back. Calling themselves the cacos, they took up arms and violence erupted. As a result, additional Marines under the command of Colonel Waller and Major Butler arrived in August 1915 to quell the uprisings. When the rebels surrounded a local town, Butler was dispatched to address the issue. In the ensuing actions, the Marines were often vastly outnumbered but were able drive the cacos away due to their superior firepower. Following a concerted effort by the Marines to isolate the cacos, the rebels took to occupying numerous small French-built stone fortifications. Once again, the Marines set out to eliminate these forces, despite heavy rains and a lack of knowledge of the mountainous jungles. In a march on Fort Capois, they came under sporadic fire and lost their heavy machine gun when a pack horse was killed and swept downriver. A veteran gunnery sergeant under Butler’s command named Daniel J. Daly volunteered to find and return the weapon. Butler knew Daly from his service in the Boxer Rebellion, when Daly had earned the Medal of Honor. He described Daly as “hard boiled” and as a Marine who one could “strike a match on his whiskers.”[27] That night, Daly set out alone to recover the much-needed machine gun. He returned the next morning with the weapon strapped to his back. For his heroism, Daly was awarded a second Medal of Honor.

An artist’s depiction of Smedley Butler, Ross Iams, and Samuel Gross storming Fort Riviere.

National Museum of the Marine Corps.

During the subsequent weeks, pressure by the pursuing Marines on the cornered rebel forces set the stage for a climactic battle at Fort Riviere. Situated formidably atop a mountain ridge, the rebels’ positions seemed impregnable to the Marine force of 600. Never daunted by a challenge, Butler proposed an unusual plan of assault. He organized his Marines to conduct their attack simultaneously on the fort from multiple directions. Under heavy covering fire from their machine guns, Butler and just 24 Marines identified a narrow drainage tunnel from which they could infiltrate the citadel.[28] The pathway was a mere four feet high and three feet wide. Recognizing that he alone had led his Marines into this plan of action, Butler prepared to go first, until Sergeant Ross L. Iams saw his officer’s natural hesitation. Iams immediately quipped, “Oh, hell, I’m going through,” and led the charge. Butler was dismayed when his orderly, Private Samuel Gross, followed suit. The Marines made the hazardous trek, crawling through the drain with Butler third in line. Rebel bullets ricocheted off the walls but remarkably missed them. As they exited, a fierce period of hand-to-hand combat ensued. By Butler’s estimation, the Marines faced a force of 60–70 cacos. When the remainder of the Marines exited the tunnel, the fierce fight came to an end.[29]

For his extraordinary bravery and forceful leadership in the engagement, Butler received his second Medal of Honor, the Haitian Medal of Honor, and the Haitian Medaille Militaire.[30] Iams and Gross also received the Medal of Honor.

In the aftermath of putting down the caco rebellion, the newly installed pro-U.S. Haitian government was required to create a new national police force. Butler was selected to organize and lead the constabulary force, known as the Gendarmerie d’Haiti. Units would be led by U.S. Marines who would be commissioned as Haitian officers. By any modern interpretation, the venture was of dubious legality and overtly imperialistic. But as the commandant of the Gendarmerie, Butler embraced his position and set out to build national roads, irrigation systems, and utility infrastructure to improve the lives of the common Haitian citizenry. The results of Butler’s work as a national police officer were mixed, but in the end, they were overtaken by more urgent national matters when, on 6 April 1917, the United States declared war on Germany and entered World War I.[31]

World War I: A Compassionate Leader of Men

To Butler’s great consternation, his leadership of the Haitian constabulary, with its complex political roles, seemed to trap him in Haiti. He desperately wanted to join the fight in Europe. Months went by as Butler exchanged a flurry of letters to gain a new command.[32]

On 3 July 1918, Butler reverted to his Marine Corps rank of colonel and assumed command of the newly formed 13th Regiment at Quantico.[33] Organizing the new unit at the newly constructed base was difficult, but it served him well in his future duties.

On 15 September, the 13th Regiment shipped out for France aboard the transport USS Von Steuben (ID 3017). The journey did not go well. After several days at sea, Butler fell severely ill with influenza. Doctors feared for his life when it was determined that this was the same sickness that had begun to sweep through U.S. military units across the nation that year. When the ship arrived at its destination port of Brest, France, Butler was miraculously on the path to recovery, but he had been weakened. The 13th Regiment was sent to a processing center known as Camp Pontanezen.

BGen Smedley Butler in France, ca. 1918.

Marine Corps History Division.

Butler was shocked to learn that, due to his illness, he was to be relieved of his command of the regiment and be given command of the camp instead. The wretched conditions he found there were shocking. The only solace he could take was in the fact that he was simultaneously promoted to the rank of brigadier general—an impressive accomplishment at the age of 37.[34]

Camp Pontanezen may not have been the combat command Butler desired, but it was vital to the Allied war effort. It was an enormous staging and supply base just outside Brest, which provided the only deep-water harbor for the embarkation of U.S. forces.[35] By the war’s end, more than 790,000 U.S. soldiers and Marines had passed through the base.[36] To reach that level of success, however, the camp needed vast improvements. As commander, Butler inherited a center beset with poor weather, which made improvised footpaths and inadequate roads become impenetrable muddy rivers. There were no floors in the barracks and tents, so the troops were forced to endure even more mud. Complicating matters, thousands of incoming servicemembers were arriving with the flu and had to be quarantined, further straining the facility. The installation’s water supply was also contaminated by local farms, and the troops lacked adequate stoves for heating. Here, Butler’s prior experience in building roads, utilities, and infrastructure in impoverished nations paid off. When the U.S. Army’s chief of supplies temporarily left Butler in charge of his command, Butler seized his opportunity to make improvements. Quickly organizing a working party of 7,000 troops, they marched on the Army warehouses to requisition massive quantities of wooden planks (a.k.a. duckboards), shovels, axes, picks, and kettles.[37] During the operation, Butler led by example. When he encountered a frustrated soldier struggling to carry a plank, he took on the burden himself, much to the pleasure of his cheering men. Upon arriving at the entrance of the camp, Butler was confronted by a military policeman who scolded him for blocking traffic. The vehicle in question was Butler’s personal staff car, traveling behind him and stocked with needed supplies. The young policeman did not recognize the general and was in disbelief when Butler told him that it was his car. When the car’s driver stopped to address Butler, the embarrassed policeman quickly realized his error.[38]

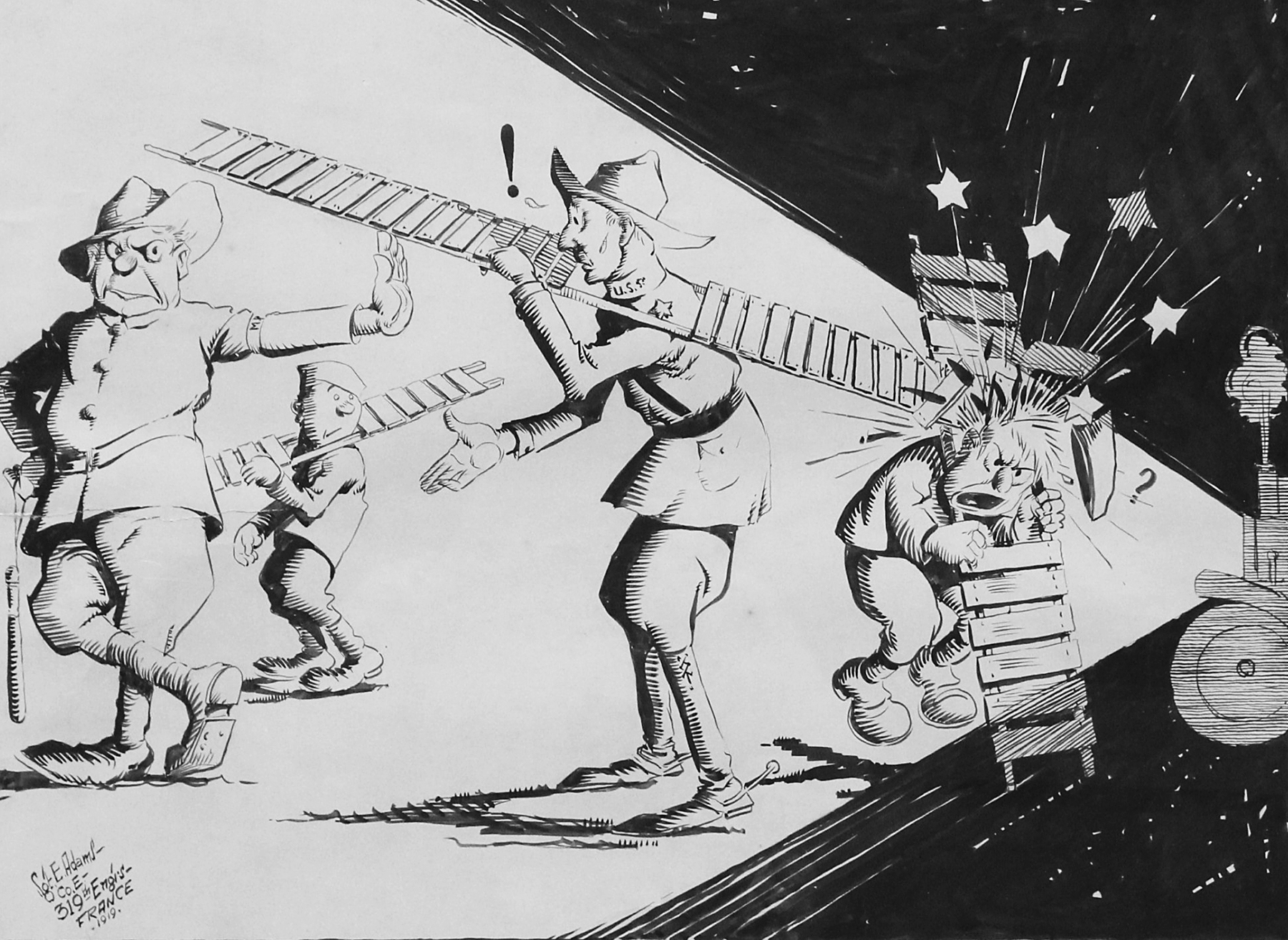

This World War I-era cartoon depicts BGen Butler following his encounter with a military police officer.

National Museum of the Marine Corps.

Word of Butler’s exploits quickly spread, with the troops under his command now referring to him lovingly as “General Duckboard.” Camp Pontanezen adopted the ladder-like wooden sidewalks that they constructed from the planks as its official insignia. It was painted on the camp’s vehicles, and a shoulder patch was worn on the troops’ uniforms. Even the base newspaper adopted the name The Duckboard.[39]

As commander of the camp, Butler’s reputation as a compassionate leader of men was cemented. He often cut red tape and ignored regulations to aid in the comfort of soldiers and Marines. Hot soup was served to anyone who needed it, 24 hours a day. Extra blankets, laundry facilities and a delousing plant were also provided. While the conditions were never made perfect, the servicemembers who were loyal to Butler revered him and morale was high. In recognition of his nonstop energy and devotion to the troops, Butler received the U.S. Army’s Distinguished Service Medal, the U.S. Navy’s Distinguished Service medal, and the rarely awarded French Ordre de l ‘Étoile Noire (Order of the Black Star).

The French Order of the Black Star is a colonial award presented for extraordinary service to the French nation. Butler received the award in recognition of the aide he provided to thousands of French colonial soldiers who served at Camp Pontanezen.

National Museum of the Marine Corps.

Following the end of the war in November 1918 and demobilization, Butler returned to Quantico. There, he inherited command of yet another base that was in dire need of improvements. Dirt roads and potholes were known to swallow vehicles. Butler set out to correct these issues, beautify the base, and make it a showpiece where Marines would be proud to serve. One part of this effort was the construction of a massive football stadium. Approximately 150 Marines worked for 80 days on the project, hand-excavating tons of dirt. When the base musicians complained that they could not perform manual labor, Butler had them play music while the Marines dug. Provided with just $5,000 for the entire project, Butler used it all on the purchase of cement to form the stands for bleachers and retaining walls. When his funds were expended, he set about acquiring everything else for free. For example, scrap metal was obtained from local railroads. While not fully completed until after World War II, the monstrous undertaking was remarkable. The football teams Butler organized to play at the stadium were equally impressive, winning 38 of their original 42 games. The stadium held as many as 60,000 fans and bares Butler’s name to this day.[40]

Butler leads Marines cheering for the Marine Corps football team.

Marine Corps History Division.

Butler’s love for his fellow Marines was legendary. Here, he marches alongside a fellow Marine during the Civil War maneuvers.

Marine Corps History Division.

In peacetime, Butler looked for other ways to find positive publicity for the Corps. Every fall, he led Marines on extended maneuvers to Civil War battlefields, employing aircraft, track towed artillery, and trucks. Over several days, the Marines would train with their modern weapons and then conduct historical reenactments of Civil War battles. These events were timed to fully garner congressional support for the Marine Corps. They were also attended by the national press and even observed in person by President Warren G. Harding.[41]

Director of Public Safety for Philadelphia: Crime Busting in the Age of Prohibition

Following the passing of the 18th Amendment and the National Prohibition Act, the widespread use and consumption of most alcohol in the United States was banned. In the ensuing years, the consequences of this moral campaign led to massive unintended issues with rising crime, violence, and gangs profiting from Prohibition.

By 1924, the city of Philadelphia was particularly hard hit. The city’s mayor, W. Freeland Kendrick, had run on the predictable campaign slogan of making the streets safe once again. He proclaimed that it would take a real-life general to do so—a man who fell outside the corruption of politics and who could not be bought, bullied, or bluffed.[42] The candidate had to be a full general, a resident of Pennsylvania, and would ideally have some sort of law enforcement background. Only Smedley Butler fit the bill.

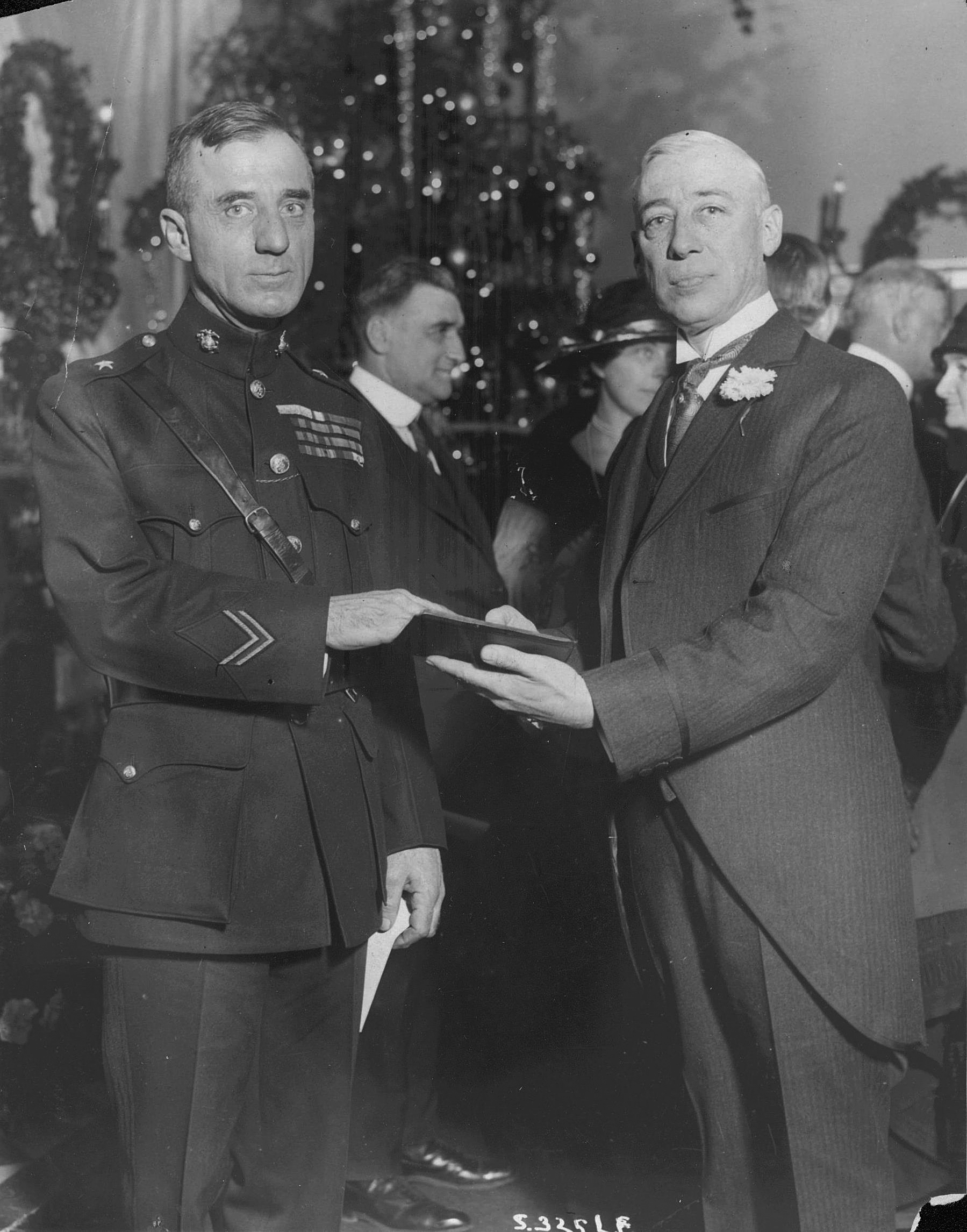

Butler takes the oath of office as the director of public safety in Philadelphia, PA, in 1924.

Marine Corps History Division.

Butler was reluctant. He did not wish to leave his beloved Marine Corps. He informed Freeland that the only way he would accept the position would be if he were granted a leave of absence from active service to take on the job. Remarkably this occurred when President Calvin Coolidge did just that.[43] Butler’s new position was unusual—as the director of public safety for the city of Philadelphia, he led not only the city’s police department but its fire department as well. This all occurred while he was still technically an active-duty Marine general. In his private comments to friends, Butler explained he was simply taking on the role as a “detail” while on leave.[44] This was not a retirement position, but a temporary assignment to clean up the city of Philadelphia.

Once committed, however, Butler set about his new job as he did all his Marine Corps missions. He immediately unleashed numerous 48-hour raids against illegal speakeasies, saloons, brothels, and gambling ventures. His next efforts focused on the elimination of corrupt and unproductive police officers. He placed more officers on the street, cut red tape, and employed revolutionary new policing concepts with patrol cars and early radios.[45] Butler characterized these efforts as “just like war,” with his men taking and consolidating sections of the “front lines” to then prepare and move on to the next assault.[46]

Unlike actual combat with his Marines, Butler soon realized that not everyone in the same uniform was on his side. After two weeks of raids, he was angered to learn that many of the locations were back in full operation days later. Butler was often prohibited by corrupt officials from firing the police officers who allowed this to happen, so he set about reassigning hundreds of officers to different districts where they were not being bribed or benefiting from the local vice.[47]

Despite Butler’s greatest efforts, by the end of his first year, Kendrick was feeling the pressure of corruption at the highest levels. Cleaning up the city would not be a one-year task. It was in fact an immensely complicated, if not impossible, undertaking. The mayor approached the Marine Corps and President Coolidge to request a second year of personal leave for Brigadier General Butler. The request was granted; however, Kendrick began to waver in his support. What was essentially a political ploy in hiring a celebrity general to clean up his city had become a complex problem. Butler was incorruptible and not willing to simply play along.

While Butler as police chief was appreciated by local churches, community groups, and average law-abiding citizens, he was less beloved by the city’s upper-class community, who often enjoyed and participated in breaking the same laws he was looking to enforce. He went head-to-head with adversaries who were much more underhanded and difficult to identify than rebels or bandits during foreign interventions. Increasingly frustrated and thwarted at every turn, Butler learned that President Coolidge would not grant him a third year of leave. As he tenured his resignation from the Marine Corps to continue anyway, he was told that he was no longer wanted and was fired by Kendrick.[48]

Thankfully for Butler, his longtime friend John A. Lejeune was the current Commandant of the Marine Corps. Butler’s resignation was denied, and in January 1926 he received orders to San Diego, California, to command the Marine barracks there.

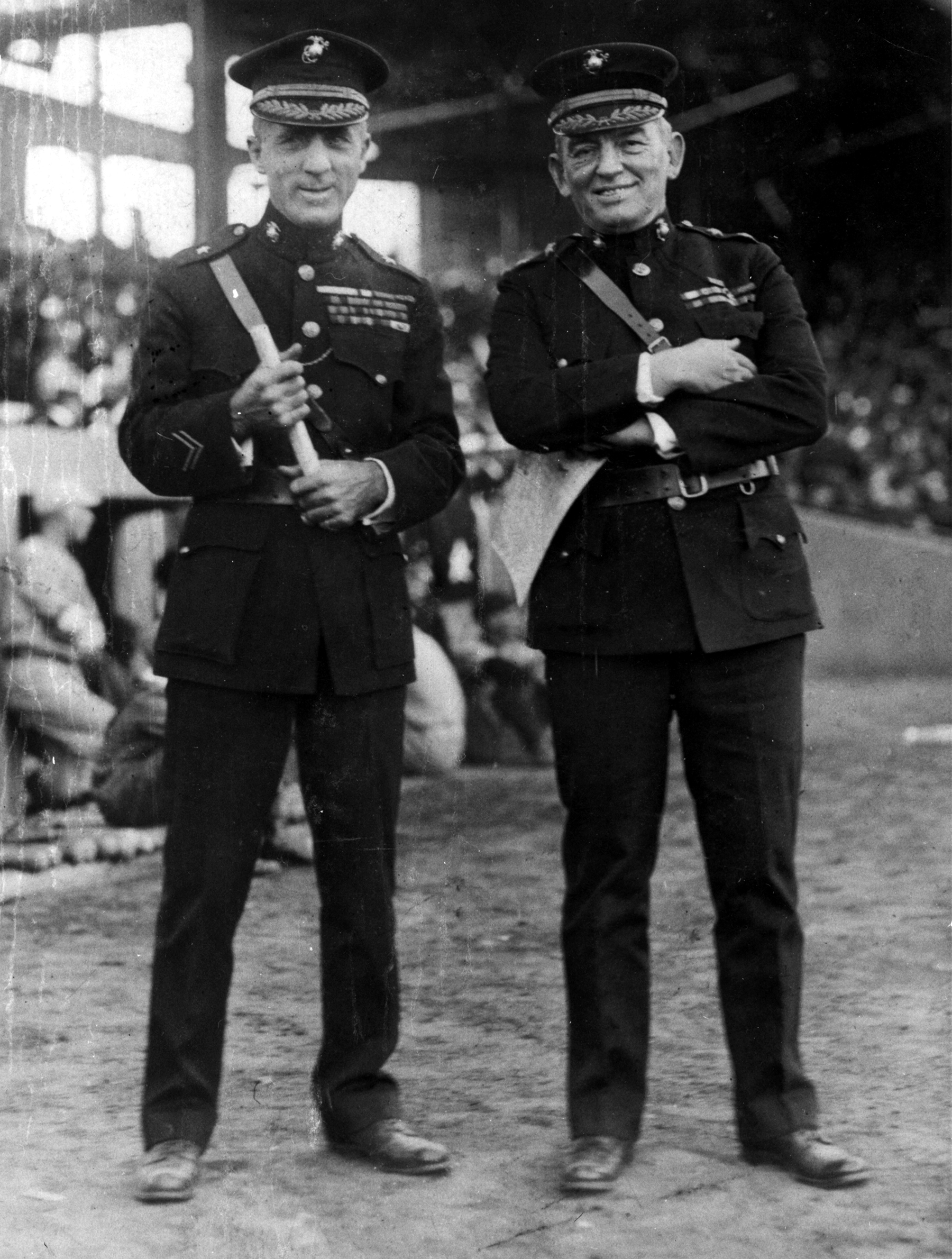

CMC John A. Lejeune poses with BGen Butler during a Marine Corps sporting event.

Marine Corps History Division.

A Career Come Full Circle: A Return to China and the End of an Era

In March 1927, Butler once again received orders to China. He was 27 years removed from the heroism of his days as a 19-year-old lieutenant in the Boxer Rebellion. This time, he commanded the entire 3d Brigade, an impressive, modern force comprising the 4th and 6th Regiments along with additional reinforcements. The China he encountered was vastly different than the one he remembered. Instead of participating in a foreign intervention, fighting fanatical Boxers and the Imperial Chinese Army, Butler was ordered to protect American citizens caught up in a brutal Chinese civil war. Nationalist Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek’s forces were bent on eliminating Chinese warlords in every major city and province. American citizens lived in fear for their lives and property.

After his arrival in China, Butler set about his work with his usual energy and vigor. Hell-bent on not allowing his Marines to repeat the behavior he observed from foreign militaries in 1900, he immediately gave orders and clarified their mission. This time, the Marines were not in China to defend colonial interests of the European and Japanese empires—they were only there to protect American lives and property. Butler, in his own words, refused to become the “cat’s paw” of foreign ambitions.[49] Drawing on the lessons of modern warfare that he had learned from the annual maneuvers at Quantico, he created a mechanized rapid reaction force. Marines armed with heavy automatic weapons and submachine guns were organized into truck units that could be immediately deployed to any location in an offensive manner. They were supported by Marine aviation rapidly conducting reconnaissance.

As nerves settled, Butler ordered his Marines to be kind to the Chinese citizens. This endeared them to the local population, in contrast to the other nations’ armies. They also set about fostering goodwill. Once more, Butler became a builder. Marines helped improve local highways and assisted in various other construction efforts. As always, concerned with the morale and disposition of his men, Butler also encouraged them to hone their appearance and pass the time through drill and other activities. Looking to the British Army and the U.S. Army as their competition and inspiration, the Marines polished their uniforms and weapons, going as far as to even nickel-plate their bayonets.[50] One humorous story from these efforts was recounted by U.S. Army soldier Charles G. Finney. As a member of the “Old China Hands,” the 15th Infantry Regiment, he observed how Butler’s Marines were jealous of the soldiers’ exquisitely polished wooden M1903 Springfield rifle stocks. Not to be outdone, Butler’s Marines set out to polish their weapons even better. The soldiers were impressed with the Marines’ efforts, but they refused to tell their rivals that they employed two sets of rifle stocks in their Service: polished stocks for parades and inspections and unpolished stocks for field maneuvers.[51]

While Butler took immense pride in being a fighter and not a politician, his years of experience in Haiti and other interventions also came full circle in China. He attended numerous ceremonies and banquets to establish improved relations with the Chinese. He also observed the Imperial Japanese Army, commenting in private on their obvious future ambitions for the conquest of China.

On 24 December 1927, Butler’s unusual experience as the head of the Philadelphia fire department came into play. When the Standard Oil Company’s Tientsin manufacturing plant caught on fire and ignited 1 million pounds of candle grease, he directed a fire brigade of more than a thousand Marines to fight the flames. The warehouse was perilously close to nearby stocks of gasoline and oil. Fighting the fire for four days, the Marines were able to avoid an even larger catastrophe.[52]

When Butler returned to the United States in 1929, he left an assignment where the culmination of his life experiences had been on full display. His return to Quantico saw him promoted to major general. At just 48 years-old, he was the youngest Marine officer to achieve the distinction.

In the final years of his career, Butler added a few more stories to an already remarkable career. When he discovered that the town of Quantico had become a hot spot for local bootleggers, he ordered his men to boycott the local businesses. After the reputable merchants took matters into their own hands and drove the illegal activities out, Butler ordered a parade down the tiny town’s main street, led by a Marine band.[53]

Foreshadowing the next phase of his life as a civilian, Butler was reprimanded by the U.S. secretary of the Navy, Charles F. Adams III, after giving a speech in which he explained to his audience how the United States government had forcibly installed the Nicaraguan president in 1912. He was also involved in an international political scandal and a near-court-martial when he retold stories regarding Italian dictator Benito Mussolini. The death of Major General Wendell C. Neville, who died in office as Commandant of the Marine Corps in 1930, and the retirement of Major General Lejeune the year before left Butler without two of his oldest friends in the Corps. When he was passed over for appointment to Commandant of the Marine Corps, he made up his mind to finally retire and did so in 1931.[54]

Smedley Butler at his retirement ceremony at Marine Corps Base Quantico, VA.

Marine Corps History Division.

Postwar Politics and a Coup to Overthrow the U.S. Government

As a civilian, Butler remained active in the public eye. He earned money as a public speaker with various veteran organizations and rotary clubs. In a brief foray into mainstream politics, he ran for the U.S. Senate in 1932. His platform championed common Americans suffering through the Great Depression and proposed improvements to roads and utilities. His campaign stood little chance, however, as he ran against the repeal of Prohibition. As a result, he was easily defeated, ending his career as a politician.[55]

Butler remained a champion of the military servicemembers he had served with. As the Great Depression took its toll, the United States’ World War I veterans were particularly hard hit. In the spring of 1932, an army of the unemployed descended on Washington, DC, and established camps near the Capitol. As veterans of the war, they had been promised a financial bonus for their service. By law, however, this one-time payment was only to be given to their families at the time of their death or by 1945. Given their current struggles during the Depression, the veterans demanded that the bonuses be awarded in 1932. Their protest did not end well. Ordered to relocate their camps by President Herbert C. Hoover, U.S. Army general Douglas MacArthur launched a full-scale assault on the “bonus marchers.” Employing cavalry and tanks, his soldiers tear-gassed the veterans and their families to prevent what he believed was an attempt to overthrow the U.S. government.[56]

Just nine days before, Butler had sympathetically toured the veteran’s camps. Accompanied by his college-age son, they inspected the poor conditions there. Urged on by his admirers, Butler soon found himself on stage before an estimated 16,000 veterans. Butler’s impromptu speech bolstered their morale, praised their patriotism, and proclaimed, “they didn’t speak of you as tramps in 1917 and ‘18!” He was so moved by the collective suffering and concerns of the veterans that he and his son spent the night with them, telling war stories and sharing breakfast the next morning.[57]

Butler’s sympathy and ability to rally down-trodden veterans in the “Bonus Army” did not go unnoticed. In 1933, he was approached by a wealthy businessman named Gerald McGuire, who had ties to the American Legion.[58] McGuire asked Butler to give a series of speeches critical of newly elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal at upcoming veterans events. Butler was immediately suspicious, especially after McGuire began to boast about his group’s wealth and financial connections to influential institutions and individuals on Wall Street. Butler’s concerns were further confirmed when McGuire began to make comparisons to paramilitary veterans’ organizations in France and Italy. The mystery businessmen had sought Butler out with the misinformed belief that the Marine general and champion of “the common man” could be tricked, or bribed, into creating a similar veterans’ movement.

For the second time in his life, Butler took on the duties of a spy. This time, however, he was not infiltrating the Mexican Army, but rather a potential military plot to end the New Deal and overthrow democracy in the United States.

Keeping detailed notes on the plotters that approached him, Butler reached out to a journalist friend from his days in Philadelphia, Paul Comly French, who was a reporter with the Philadelphia Record. With Butler’s influence, French secured an interview with McGuire. During their conversation, McGuire admitted his desire to see a fascist government in the United States. He further elaborated that Butler could raise an army of 1 million men overnight and that the Du Pont family could purchase arms for them directly from the Remington Arms Company on their personal credit.[59]

French’s newspaper story was published on 21 November 1935. The headline read “GEN. BUTLER CHARGES FASCIST PLOT.” Remarkably, the story was met with skepticism and mockery by some. Time magazine’s counter headline called it a “Plot without Plotters.” Financial backers accused in the story called it ridiculous and outright fantasy.[60] The accusations, however, were serious enough to be brought before the U.S. House of Representatives’ Un-American Activities Committee. As a complex web of details and financial involvement was unveiled and denied, the committee caught McGuire in several lies and misstatements, but it was never able to fully trace the bribes he offered back to other conspirators. In the end, despite numerous questions remaining unanswered and open lying under oath by those involved, the committee’s inquiry ended without any charges being filed. Later transcripts from the testimony even redacted the names of key conspirators. The committee’s final report simply stated that while they had uncovered evidence of a proposed plot, they simply did not discover anyone who had acted on it.

The later years of Butler’s life were filled with a passion for preventing unnecessary U.S. military interventions and wars. Speaking even more freely than he did as a Marine officer, he tirelessly traveled the country to give radio addresses, speeches, and interviews on the topic. His written arguments were eventually compiled into a book titled War Is a Racket.[61] In it, he argued that the U.S. military should focus all of its energy on the defense of the nation alone, avoiding corporate or imperialistic ambitions.[62]

In retrospect, by 1939, Butler’s fear of Marines being sent to fight for the Standard Oil or United Fruit Companies was becoming increasingly outdated. A new war had erupted in Europe. As he hectically continued to protest foreign entanglements, events of the world began to pass him by. A German blitzkrieg (lightning war) rolled through Poland in September 1939. In May 1940, Germany turned its army towards France and the United Kingdom. Two great empires were in a monumental fight for their very survival.

After completing a six-week speaking tour, Butler admitted in his personal correspondence the inevitability of a Second World War. His tireless efforts to protect American lives had taken its toll. He felt increasingly fatigued and lost more than 20 pounds from his already diminutive stature. Hoping to get some rest, he checked into the Philadelphia Navy Yard hospital on 23 May 1940. He would never recover. Smedley Darlington Butler died of cancer four weeks later with his family by his side.

Endnotes

[1] “Butler, Smedley Darlington, ‘Ol’ Gimlet Eye,’ MajGen,” U.S. Marine Corps Medal of Honor Biographies, Marine Corps History Division, 5 November 1951 (AHC-1265-hph), 1, hereafter Butler Biography.

[2] Medal of Honor Citation for Maj Smedley D. Butler, USMC, Veracruz, Mexico, 22 April 1914, Award Citations File, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA, hereafter Medal of Honor citation (1914).

[3] The other two-time Marine Corps recipient of the Medal of Honor was SgtMaj Daniel J. Daly.

[4] Mike Smith, “Butler Stadium Hand-Dug, Built by Smedley’s Marines,” Quantico Sentry, 18 August 2020.

[6] Anne Cipriano Venzon, General Smedley Darlington Butler: The Letters of a Leatherneck, 1898–1931 (New York: Praeger, 1992), 1–2.

[7] Lowell Thomas, Old Gimlet Eye: The Adventures of Smedley D. Butler (New York: Farrar and Rinehart, 1933), 5, 253.

[8] Thomas, Old Gimlet Eye, 4.

[9] “Butler, Thomas Stalker, 1855–1928,” United States Congress Bioguide, accessed 14 May 2024.

[10] Venzon, General Smedley Darlington Butler, 6–7.

[11] Thomas, Old Gimlet Eye, 11–22.

[12] Venzon, General Smedley Darlington Butler, 13–16.

[13] Venzon, General Smedley Darlington Butler, 20. Pvt Thomas W. Kates’ Medal of Honor is a part of the collection of the National Museum of the Marine Corps. It can be seen on display in the museum’s exhibit dedicated to the Boxer Rebellion.

[14] John E. Lelle, The Brevet Medal (Springfield, VA: Quest Publishing, 1988), 11–12.

[15] Officers received the brevet rank but not the pay level of the new rank. They were also technically outranked by officers with higher nonbrevet rank, although they could serve at positions commensurate with their brevet rank if no officers with that permanent rank were available. It was a confusing system that often led to arguments over command.

[16] Dwight S. Mears, The Medal of Honor: The Evolution of America’s Highest Military Decoration (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2018), 48–49.

[17] Thomas, Old Gimlet Eye, 62–64.

[18] Venzon, General Smedley Darlington Butler, 24.

[19] Thomas, Old Gimlet Eye, 73–75.

[20] Butler Biography, 1.

[21] Hans Schmidt, Maverick Marine: General Smedley D. Butler and the Contradictions of American Military History (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1998), 46.

[22] Schmidt Maverick Marine, 63–66.

[23] Schmidt Maverick Marine, 63–66; and Mark Strecker, Smedley Butler, USMC: A Biography (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2011), 56–57.

[24] Medal of Honor citation (1914).

[25] Thomas, Old Gimlet Eye, 180. RAdm Frank Friday Fletcher had been awarded the Medal of Honor for simply commanding the occupation of Veracruz.

[26] Strecker, Smedley Butler, 59–61.

[27] Strecker, Smedley Butler, 63.

[28] Strecker, Smedley Butler, 64.

[29] Thomas, Old Gimlet Eye, 203–7.

[30] Medal of Honor Citation for Maj Smedley D. Butler, USMC, Fort Riviere, Haiti, 17 November 1915, Award Citations File, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

[31] Strecker, Smedley Butler, 66–73.

[32] Strecker, Smedley Butler, 73.

[33] Annette D. Amerman, United States Marine Corps in the First World War: Anthology, Selected Bibliography, and Annotated Order of Battle (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps History Division, 2016), 223.

[34] Stecker, Smedley Butler, 74–75.

[35] Amerman, United States Marine Corps in the First World War, 224.

[36] Strecker, Smedley Butler, 75.

[37] Strecker, Smedley Butler, 75–76.

[38] Thomas, Old Gimlet Eye, 252–53.

[39] Thomas, Old Gimlet Eye, 253.

[40] Smith, “Butler Stadium Hand-Dug, Built by Smedley’s Marines.”

[41] Strecker, Smedley Butler, 82.

[42] Thomas, Old Gimlet Eye, 264.

[43] Venzon, General Smedley Darlington Butler, 242.

[44] Strecker, Smedley Butler, 85.

[45] Venzon, General Smedley Darlington Butler, 243.

[46] Schmidt, Maverick Marine, 147.

[47] Schmidt, Maverick Marine, 147.

[48] Strecker, Smedley Butler, 90–91.

[49] George B. Clark, Treading Softly: U.S. Marines in China, 1819–1949 (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2001), 66–67.

[50] Thomas, Old Gimlet Eye, 290.

[51] Charles G. Finney, The Old China Hands (New York: Doubleday, 1961), 159–61.

[52] Thomas, Old Gimlet Eye, 292–95.

[53] Thomas, Old Gimlet Eye, 299.

[54] Thomas, Old Gimlet Eye, 303–4.

[55] Jonathan M. Katz, Gangsters of Capitalism: Smedley Butler, the Marines, and the Making and Breaking of America’s Empire (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2022), 312.

[56] Strecker, Smedley Butler, 122.

[57] Katz, Gangsters of Capitalism, 314–15.

[58] The American Legion is a veterans organization founded in 1919, primarily by World War I servicemembers. The organization continues today with nearly 2 million members and 13,000 posts worldwide. “History,” American Legion, accessed 14 May 2024.

[59] Strecker, Smedley Butler, 130–31.

[60] Strecker, Smedley Butler, 131–32.

[61] MajGen Smedley D. Butler, USMC (Ret), War Is a Racket (New York: Round Table Press, 1935).

[62] Venzon, General Smedley Darlington Butler, 311–12.