Chapter 17

From the Halls of Montezuma

The Collection of Major Levi Twiggs

By Owen Linlithgow Conner, Chief Curator

Featured artifacts: Officers Undress Coat (2008.3.5); White Trousers (1994.190.1); Officers Dress Blue Coat, ca. 1840–1847 (2008.3.1); and Officers Dress Green Coat, ca. 1830–1840 (2008.3.4)

The National Museum of the Marine Corps (NMMC) is the primary repository for more than 65,000 artifacts that span the history of the U.S. Marine Corps.[1] The size of the collection is significant, but the eras with which these artifacts are associated are not evenly distributed. The majority of the collection dates from the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. This is primarily because history was actively collected by the museum in its different iterations, beginning with the first-known Marine Corps museum in Quantico, Virginia, in 1940.[2] Another reason for the preponderance of twentieth- and twenty-first-century artifacts is due to simple math. Prior to World War I (1914–18), the Marine Corps was not a large branch of Service. From 1775 to 1900, there were never more than 4,000 total Marines in uniform. When it comes to officers, these limited numbers become even starker. For example, at the start of the Mexican-American War (1846–48) there were only 42 officers in the entire Marine Corps.[3] As a result, the existence of any nineteenth-century artifacts are extraordinarily rare.

The uniforms of Mexican War-era Marine Corps officer Maj Levi Twiggs are among the earliest and rarest in the collection of the National Museum of the Marine Corps.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

This portrait of Maj Levi Twiggs depicts the officer as he looked at the time of his death in 1847.

National Museum of the Marine Corps.

One notable collection that defies these odds is associated with Major Levi Twiggs, who served in the Marine Corps from 1813 to 1847. His name is little known outside the world of Marine Corps history aficionados, but he is most often recognized as a beloved officer of the era who died leading an assault on Chapultepec Castle in Mexico City, Mexico, on 13 September 1847.[4] The singular association of this tragedy is factual but unfair. The full history of Twiggs is far more complex and interesting, and his collection of early Marine Corps artifacts is one of the most significant in the collection of the NMMC.

Born in Richmond County, Georgia, in 1793, Levi Twiggs was the son of Major General John Twiggs, an American military officer who rose through the ranks of the Georgia Militia during the American Revolutionary War (1775–83). At start of the War of 1812 (1812–15), Levi Twiggs was a student at Athens College in Georgia. He asked his parents’ permission to join the military, but he was denied and forced to remain enrolled in college. A year later, Twiggs’s persistence paid off. He was allowed to leave school and was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Marine Corps on 10 November 1813. Following promotion to first lieutenant in 1815, Twiggs received his first major assignment as commander of the Marine detachment aboard the U.S. Navy frigate USS President (1800).[5] The ship was captained by none other than Commodore Stephen Decatur Jr., an inspiring young naval officer already famous for his heroism in burning the stranded frigate USS Philadelphia (1799) during the First Barbary War (1801–5).[6]

It was on board the President that Twiggs saw his first combat. In January 1815, the frigate became engaged with a blockade fleet of the British Royal Navy outside New York Harbor. Despite the President’s formidable 55-gun armament and well-documented speed, the ship was at a distinct disadvantage, as it had run aground while leaving port and sustained considerable damage to its hull and masts. Unable to outrun the pursuing British warships, Decatur decided to fight the faster HMS Endymion (1797) before the rest of the British fleet could join in the attack. The American captain had already established himself as a national hero for his courage in the First Barbary War, the Quasi-War with France (1798–1800), and earlier actions in the War of 1812.[7] Decatur’s daring plan of escape did not disappoint. He called on the crew of the President to disable the Endymion and to board and capture the enemy ship. Hours of broadsides and cannon fire ensued. The President tried in vain to position itself alongside the Endymion, while the British captain skillfully avoided the American’s attempts. All the while, Levi Twiggs’s Marines fought valiantly from their positions among the ship’s tops, firing volley after volley onto the Endymion’s decks.[8] Ultimately, the skill of the Royal Navy’s gunners carried the day, and after receiving significant damage to the President’s hull, Decatur was forced to surrender. In his after-action report he noted the Marines’ skill: “Lieutenant Twiggs displayed great zeal, his men were well supplied, and their fire incomparable.”[9] Period newspaper accounts claimed that Twiggs’s 56-man Marine detachment fired more than 5,000 cartridges during the engagement.[10] When Decatur offered his sword to the victorious British captain of the Endymion, it was returned to him in an act of admiration for the American crew’s noble defense. Decatur, Twiggs, and the rest of the President’s officers spent the rest of the war as well-cared-for prisoners on the island of Bermuda.[11]

Lt Twiggs and his Marine detachment fought valiantly during their ship’s engagement with the HMS Endymion (1797).

Naval History and Heritage Command.

Following the end of the War of 1812, Twiggs served in numerous Marine Corps shore and duty stations before rising to the rank of captain in 1830. In 1836–37, he took part in fighting with the Creek and Seminole Indians in Georgia and Florida.

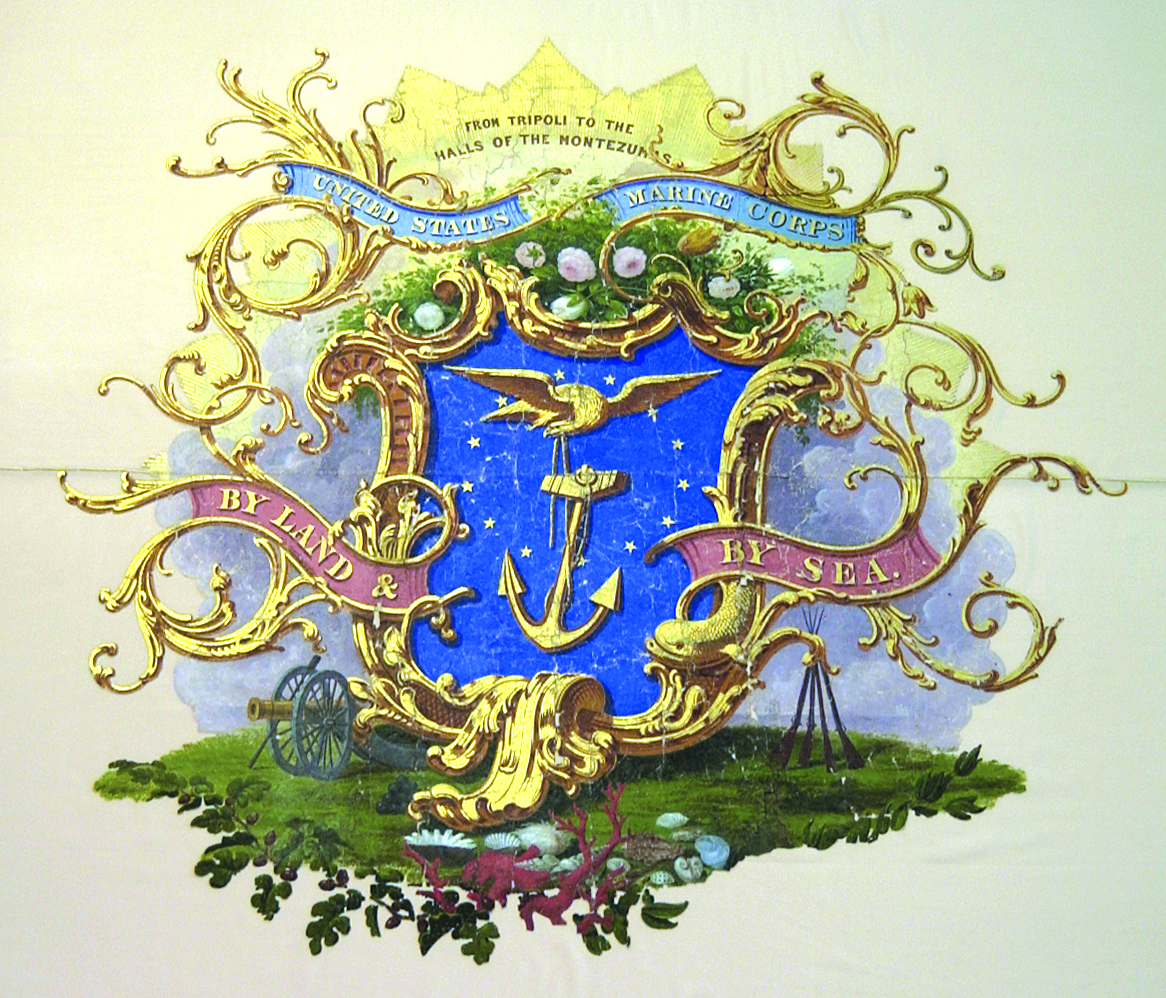

This hand-painted flag was presented to the Marine Corps around 1840 by the artist, Joseph Bush of Boston. Known as the “Bush flag,” it is the oldest known flag to have been used by the Marine Corps.

National Museum of the Marine Corps.

During the Mexican-American War, Twiggs, now a major, was part of a battalion of Marines raised in New York in June 1847. Assigned to the American forces under the command of U.S. Army major general Winfield Scott, the Marines landed at the port city of Veracruz, Mexico, and joined the advancing American columns in their attack on Mexican forces just outside Mexico City. The enemy soldiers and military cadets, led by General Antonio López de Santa Anna, held fortified positions surrounding Chapultepec Castle. On 13 September, Twiggs led a detachment with ladders and other engineering equipment in a daring attack to breach the castle walls. With Twiggs leading from the front, the attack was successful, but not before the Marine officer was shot through the heart by enemy musket fire. The assault helped break the Mexican defense and ultimately allowed the combined American division of soldiers and Marines to march on Mexico City. This action served as the original inspiration for the phrase “From Tripoli to the halls of Montezuma,” which is emblazoned on one of the earliest known Marine Corps colors. The phrase later served as inspiration for the famous lyrics of the Marine Corps Hymn.[12]

The earliest documentation of Levi Twiggs’s artifacts being donated to the Marine Corps is noted in correspondence to the Commandant of the Marine Corps dated 2 July 1953. This memorandum notes the arrival of the personal papers of both Levi Twiggs and his son, U.S. Army lieutenant George Twiggs, who was also killed in the Mexican-

American War just weeks before his father. They were donated by Sarah A. Machold (née Morris), the great-great-granddaughter of Levi Twiggs. At this time, Machold informed the Marine Corps of her great-great-grandfather’s uniforms and personal items being held in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art in Pennsylvania. She subsequently requested their transfer to the Marine Corps, and the art museum agreed to do so. This same memorandum noted the identification of another Twiggs relative, U.S. Army Colonel William W. West III, who would later donate a period portrait of Levi Twiggs and his uniform sash.[13]

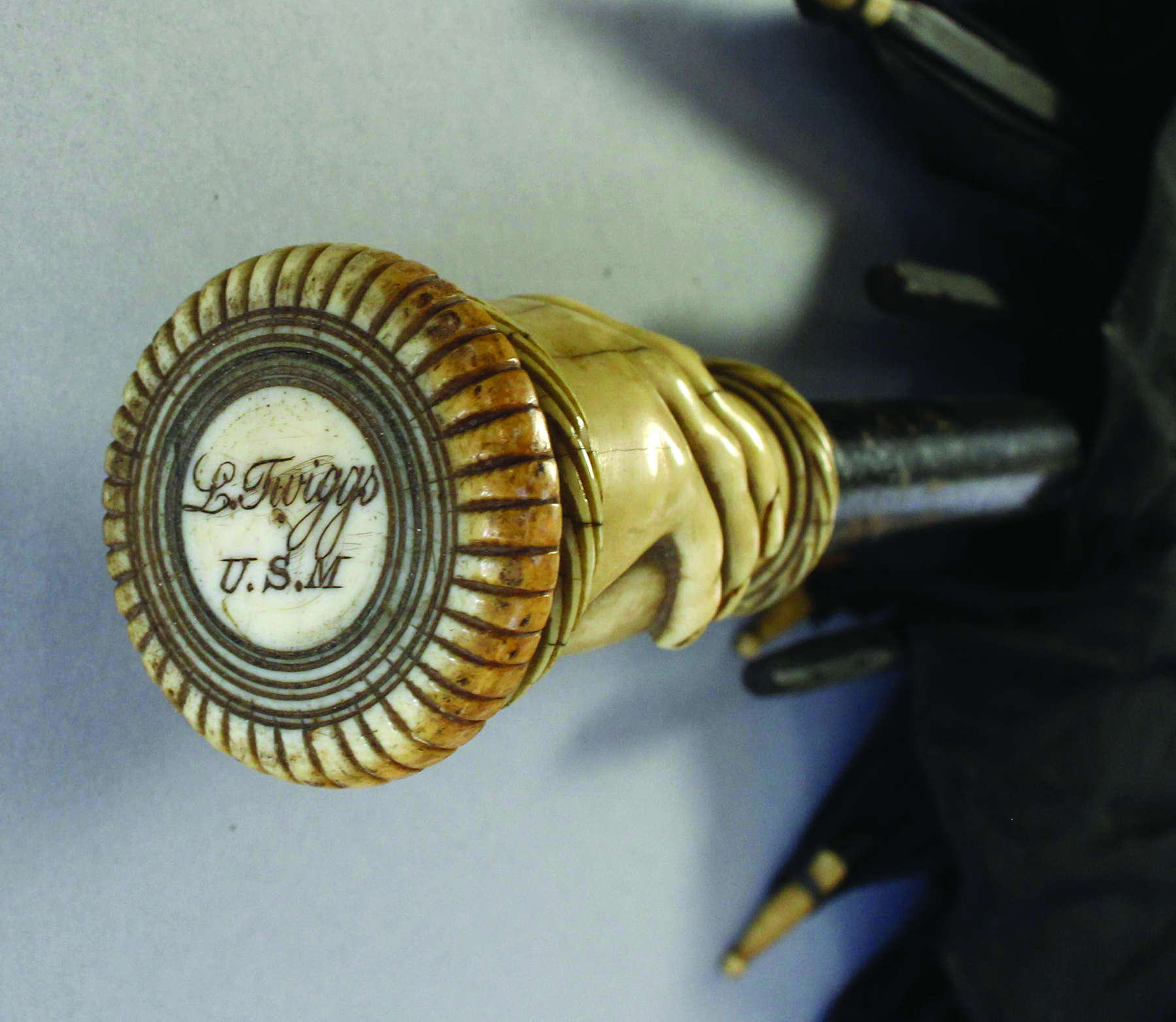

Levi Twiggs’s personal umbrella is engraved with his name on its ivory top.

National Museum of the Marine Corps.

The artifact collection of Levi Twiggs ranges from his personal umbrella to fatigue and dress uniform pieces that span the entirety of this Marine Corps career. Arguably the two most significant items are his Regulation 1833 and 1839 coats. These rare uniforms are a critical link in the history of the Marine Corps’ dress blue uniforms that are still worn today.

Levi Twiggs’s pattern 1833 dress uniform coat is displayed in the National Museum of the Marine Corps’ “Early Years” gallery.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

Twiggs’s 1833 pattern uniform marked an unusual break from what became the Marine Corps’ tradition of dark blue dress uniforms. During the administration of U.S. president Andrew Jackson (1829–37), the decision was made for the Marine Corps to return to green uniforms colored similarly to those worn by Continental Marines during the American Revolutionary War.[14] This decision was problematic for several reasons. Due to manufacturing shortages in the United States, the Marine Corps quartermaster was forced to important the green broadcloth material from Great Britain. This proved costly and was politically unpopular given that England had been an enemy of the United States in two major wars. Moreover, the unique green color was difficult to manufacture due to the dyes used. Primary sources document how almost immediately upon the issue of these new uniforms, complaints began to reach Marine Corps headquarters regarding the uniforms fading with minimal wear both on land and at sea. Seagoing Marines experiencing the worst of these issues saw their Continental green coats fade to unusual yellow or blue-green colors. While the green uniforms amounted to a failed experiment, they did contribute to the history of today’s modern Marine Corps dress uniforms. This was the first time in which the sleeve cuffs of the uniform were adorned with lace and buttons indicating the wearer’s rank. While the ornate gold lace would eventually disappear, the tradition of brass buttons with decorative trim remains to this day in enlisted Marine dress coats.[15]

Following the end of the Jackson administration, the Commandant of the Marine Corps, Colonel Archibald Henderson, quietly reverted to the dark blue dress uniforms that Marines preferred.[16] This Regulation 1839 uniform was worn through the Mexican-American War and marked the beginning of an uninterrupted tradition of dark blue dress uniforms that continues today.

Levi Twiggs’s 1840 pattern uniform, officer sword, and pistol are part of the collection of the National Museum of the Marine Corps.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

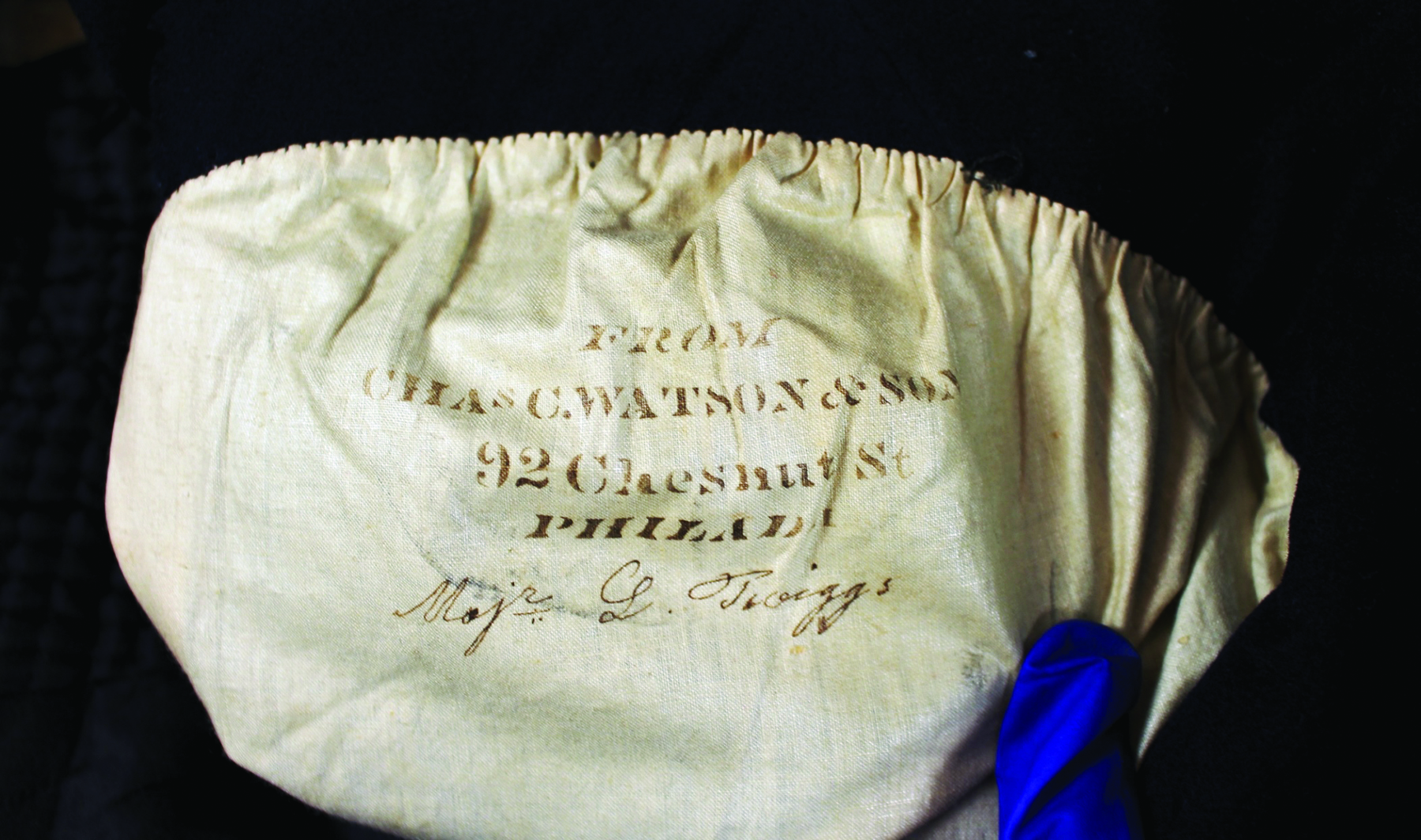

The interior sleeve of Twiggs’s undress uniform retains his original eighteenth-century signature.

National Museum of the Marine Corps.

Endnotes

[1] Office of the Museum Registrar, National Museum of the Marine Corps, Triangle, VA. As of 28 February 2023, the official artifact count was 65,717.

[2] Kenneth L. Smith-Christmas, “Why Things Are the Way They Are at the Marine Corps Museum” (unpublished paper, Marine Corps Museum, Quantico, VA, n.d.) 1-2. “The original museum was founded in 1940 at Little Hall, MCBQ [Marine Corps Base Quantico, Virginia]. Battle trophies from WWI [World War I], flags, etc., were displayed on its second deck with a series of about a dozen mannequins in approximations of Marine Corps uniforms from 1775 to WWI, that were curated by Colonel J. J. Capolino. Starting in 1946, CWO [Chief Warrant Officer] Harold Johnson took over, and started an accessions ledger, listing what was then in the collection.”

[3] Albert A. Nofi, Marine Corps Book of Lists: A Definitive Compendium of Marine Corps Facts, Feats and Traditions (Conshohocken, PA: Combined Publishing, 1997), 31–33.

[4] “Mourning Order (The Death of Major Twiggs),” Headquarters Marine Corps, 20 November 1847 (Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA).

[5] Official U.S. Marine Corps Biographies, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

[6] “Stephen Decatur, 5 January 1779–22 March 1820,” Naval History and Heritage Command, accessed 10 April 2023.

[7] “President I (Frigate),” Naval History and Heritage Command, accessed 10 April 2023.

[8] Irvin Anthony, Decatur (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1931), 224–27.

[9] Official U.S. Marine Corps Biographies, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

[10] Daily National Intelligencer, 22 November 1847, 1–2.

[11] Official U.S. Marine Corps Biographies, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

[12] Official U.S. Marine Corps Biographies, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

[13] Official U.S. Marine Corps Research File, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

[14] Charles H. Cureton, “Parade Blue, Battle Green,” in The Marines (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps Heritage Foundation, 1998), 135.

[15] Cureton, “Parade Blue, Battle Green,” 136.

[16] Cureton, “Parade Blue, Battle Green,” 136.