Chapter 14

Marine Life in Magic China

By Jennifer Castro, Cultural and Material History Curator

Featured artifacts: Smoking Jacket (Robe) (2008.81.1); Plaque, from the Green Howards, Shanghai, 1927 (1983.220.1); Napkin Ring, Cloisonné, W. Williams (1971.14.1); Napkin Ring, Cloisonné, J. Papas (1983. 224.1); Lighter, Peiping (2018.136.36); Riding Crop, L. A. Brown (1977.1281.1); Swagger Stick, L. A. Brown (1977.1280.1); and Album, Embroidered (on loan from the Marine Corps History Division) (COLL/3832)

In the U.S. Marine Corps, there is no greater honor than earning the title of Marine. But throughout the Corps’ 250 years of history, many subcultures and other titles have also been used. For nearly half of the twentieth century, it was the title of “China Marine” that carried the most adventurous allure.

Marines were associated with China since the first U.S. Navy vessels began making port calls there in the early 1800s and until the evacuation of dependents and U.S. military personnel in the early days of World War II. For all that time, service in the Far East was exotic and mysterious. China was a duty station with its own unique lifestyle. During the course of a Marine’s service, the ability to serve abroad in this far-off land was a must-have experience, particularly at the height of China Marine life in the 1920s and 1930s.

A recruiting poster encouraging those interested in travel to join the Marines.

Photo from the collection of Dirk Salverian.

A train leaving from Quantico, VA, for Philadelphia, PA, with field pieces and Marines bound for duty in China, 29 March 1927.

International Newsreel photo, from the collection of Dirk Salverian.

Background History of Marines in China

Of all the exotic locations that Marines have inhabited throughout history, China has always remained unique within the Corps’ social, economic, and cultural history.[1] In 1819, the frigate USS Congress (1799), commanded by Captain John D. Henley, became the first U.S. Navy ship to visit the Far East. Henley was directed by the U.S. secretary of the Navy, Smith Thompson, “to proceed upon important service, for the protection of the commerce of the United States in the Indian and China Seas.”[2] The Marine detachment aboard the Congress likely were the first Marines to ever step foot in China.[3] The United States, emulating France and the United Kingdom, tried to establish peaceful relations with the Qing Dynasty, as China was known at the time, for trade. The Chinese were generally opposed to foreigners. In 1844, the United States and the Qing Dynasty signed the Treaty of Wanghia, which was the first formal treaty signed between the two nations. The agreement was analogous to what the United Kingdom had gained with the signing of the Treaty of Nanjing (Nanking) in 1842.[4]

At the turn of the century, Marines serving in China were primarily based in cities such as Shanghai, home to the country’s largest International Settlement; Peking (Beijing), where the American Legation was located; and Tientsin (Tianjin). Occasional international incidents or domestic concerns, the most notable of which occurred in 1927, 1932, and 1937, resulted in Marine reinforcements coming ashore from Navy ship detachments with the U.S. Asiatic Fleet or being sent to China by transport ships from the United States or the Philippines.

A weekly newsletter highlighting the Marine presence in China.

Walla Walla Newsweekly 5, no. 4 (2 July 1932), from the collection of Dirk Salverian.

Lifestyles of Marines in China

In the early twentieth-century, young men joined the Marine Corps for a variety of reasons, including a dependable salary, job security, and more. Most dreamed of leaving home, traveling abroad, and seeing the world. For most, the start of their journey as a Marine began with a visit to a Marine Corps recruiting station, where their questions about enlistment and service opportunities were answered by recruiters armed with colorful brochures. These artistically attractive pamphlets and other ephemera were dedicated to inspiring men looking for a life of excitement. Possible service locations within the United States included California, New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Seattle, and Washington, DC, while far-flung locations in the tropics such as the Philippines or the Caribbean islands were also featured. If one was not sure where to serve, there was always the option to serve aboard ship, which could offer a sampling of many different locations. For many Marine recruits, however, duty in China stood alone. Recruiting materials from 1937 beckoned young recruits “to follow the trail of adventure, travel to out of the way places of the world. You’ll find them in the Virgin Islands, the Philippines, Guam and the mystical land of the Far East—CHINA.”[5]

A “Magic China” Marine Corps recruiting brochure (M.C.P.B. 70607) dated 12 June 1937.

Photo from the collection of Dirk Salverian.

China was a location unlike any other, and certainly worthy of all capital letters in the recruiters’ brochure. It was more than just a duty stop—it was where the empires and cultures of the West and East collided. It was also a place where even the average enlisted Marine could afford luxuries, see worldly sights, and lead a life of excitement unheard of anywhere else.

The Colorful Lives of the China Marines

In 1930, there were 19,380 men serving in the Marine Corps: 1,208 officers and 18,172 enlisted. The strength of the Corps continued to decrease until 1940, after World War II had begun in Europe, when there were 28,345 total Marines serving.[6]

Roughly correlating with this era of a downsized Marine Corps was the Great Depression (1929–39). The suffering in the United States during this time made the idea of military service even more appealing, providing hopeful young men the chance to escape the nation’s economic issues. After enlistment and completion of their training, Marines were assigned duty stations across the country and abroad. The lucky ones found themselves on a ship to China. There, they may be assigned to the American embassy in Peking, at the Legation Quarter where several foreign diplomatic legations or embassies were located, or at the International Settlement in Shanghai. Countries that maintained legations in the Legation Quarter grew over the years. In 1901, there were 11 countries that included Germany, Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Spain, the United States, France, the United Kingdom, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, and Russia. By 1911, these were joined by Sweden, Portugal, Denmark, and Brazil, and by 1922 they were joined by Norway, Uruguay, and Brazil.[7] Marines were also stationed at the International Settlement, an enclave under the control of several different countries that included British, American, and Japanese citizens. Marines also served in Tientsin, where there were several foreign enclaves, concessions that included the United Kingdom and the United States.

A postcard featuring a Marine riding in a hand-drawn rickshaw sent by Pvt Glen E. Densmore to his family while serving in Peking, China.

Photo from the collection of Dirk Salverian.

In 1940, Private First Class William H. Chittenden was assigned to the Marine detachment at the American Embassy in Peking. In his biography, he recalled how he finally got his chance to travel and see the world:

Finally, it happened! The barracks bulletin board carried a notice that “volunteers will be considered for openings for duty on Asiatic station.” That was Saturday, February 10 (1940). As soon as I read the notice, I was in the company office to volunteer. That was the whole reason I had enlisted. As the recruiting office brochure said, “MAGIC CHINA.” Then the wait began. . . . In five days, the names were on the barracks bulletin board. PFC Chittenden, William H., USMC #276245 made the list![8]

China was a strange mix of the old and new. There were old customs, seemingly ancient buildings, hand-drawn rickshaws, as well as twentieth-century ideas and modern amenities.

Word of mouth from Marines who served in China in the early 1900s documented duty protecting American lives, property, and commerce; guarding the American Embassy; and serving at their military posts among other assignments. Marines in Shanghai and Peking lived quite well. They often had Chinese servants to do their chores, and they enjoyed the fine accommodations at the enlisted club, including $1 Johnnie Walker Black Label whiskey. Weekends consisted of meeting girls at the clubs, touring sites in China, and purchasing fine trinkets and souvenirs on a basic enlisted man’s salary. In 1923, a Marine private first class earned $30.00 a month; a corporal, $42.00; a sergeant, $54.00; and a sergeant major, $126.00. This pay remained basically the same from 1923 to 1940.[9] Compared to Stateside duty stations, the value of those dollars was enhanced significantly in China.

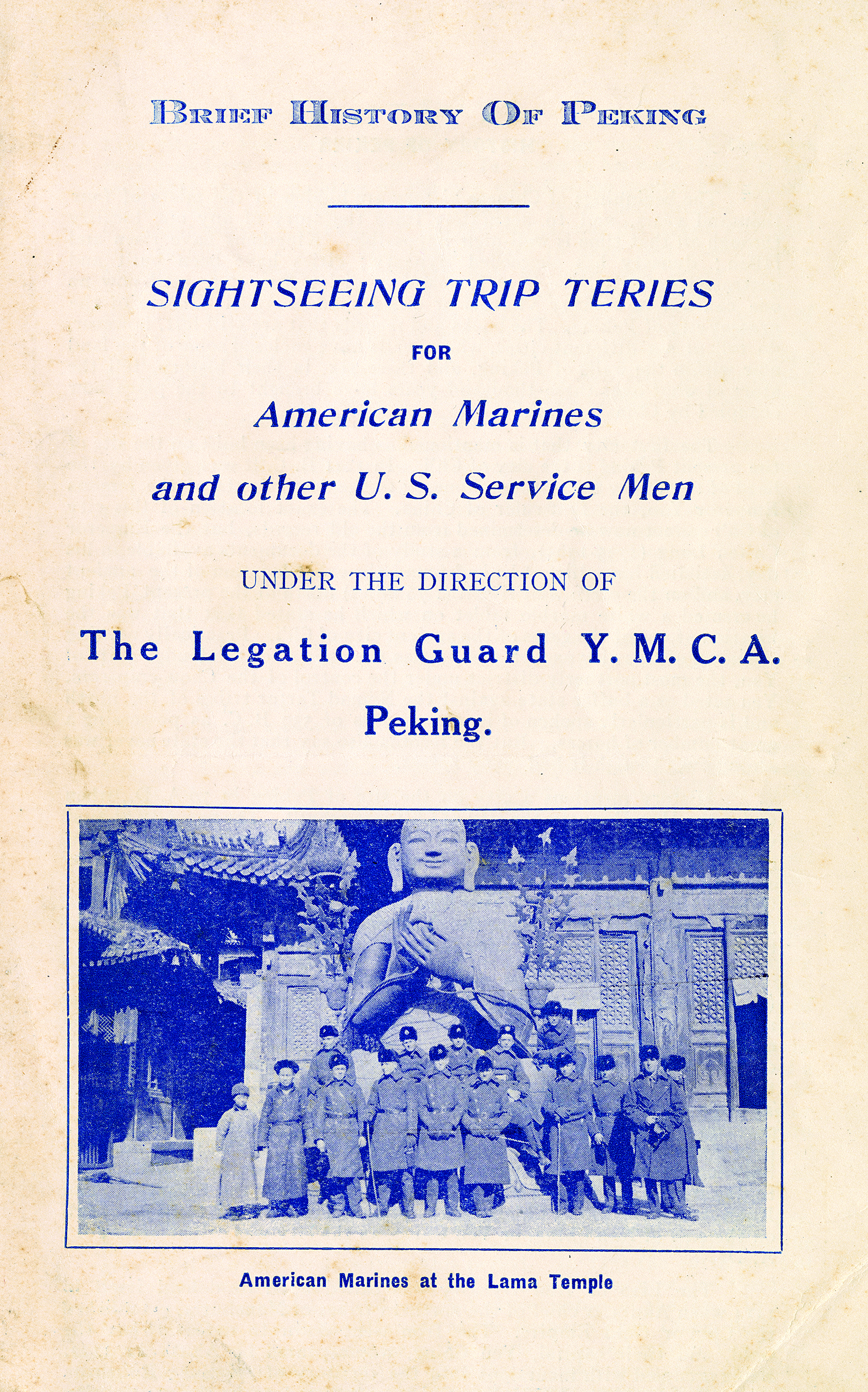

A booklet for one of a series of sightseeing trips that Marines could enjoy in China.

Photo from the collection of Dirk Salverian.

Off-duty hours in China afforded Marines with a chance to take liberty and enjoy both educational and recreational opportunities. The Legation Guard YMCA in Peking offered sightseeing trips for Marines and other servicemembers to visit historic sites of interest. These included the Great Wall of China, the Temple of Heaven, the Temple of Agriculture, the marble five-arched pailous at the Ming tombs, the Lama Temple, the Forbidden City, the shops in Chien Men (Zhengyangmen), the Winter Palace (Yuanmingyuan), the Summer Palace, the Great Pagoda in the city of Soochown (Suzhou), Tiger Hill, and the City Temple.[10]

For less cultural forms of recreation, the Marines could visit local athletic facilities, the YMCA, theaters, shops, hotel restaurants, local bars, the 4th Marines club, and the privates’ and noncommissioned officers’ clubs. Many Marines enjoyed meals at one of many restaurants located in Shanghai, such as the Sun Ya Restaurant located on 719 Nanking Road. In an article written by Bill Savadove titled “A Short History of Gluttony in Shanghai” appearing in the 1936 guidebook Shanghai High Lights, Low Lights, Tael Lights, the author gave this advice:

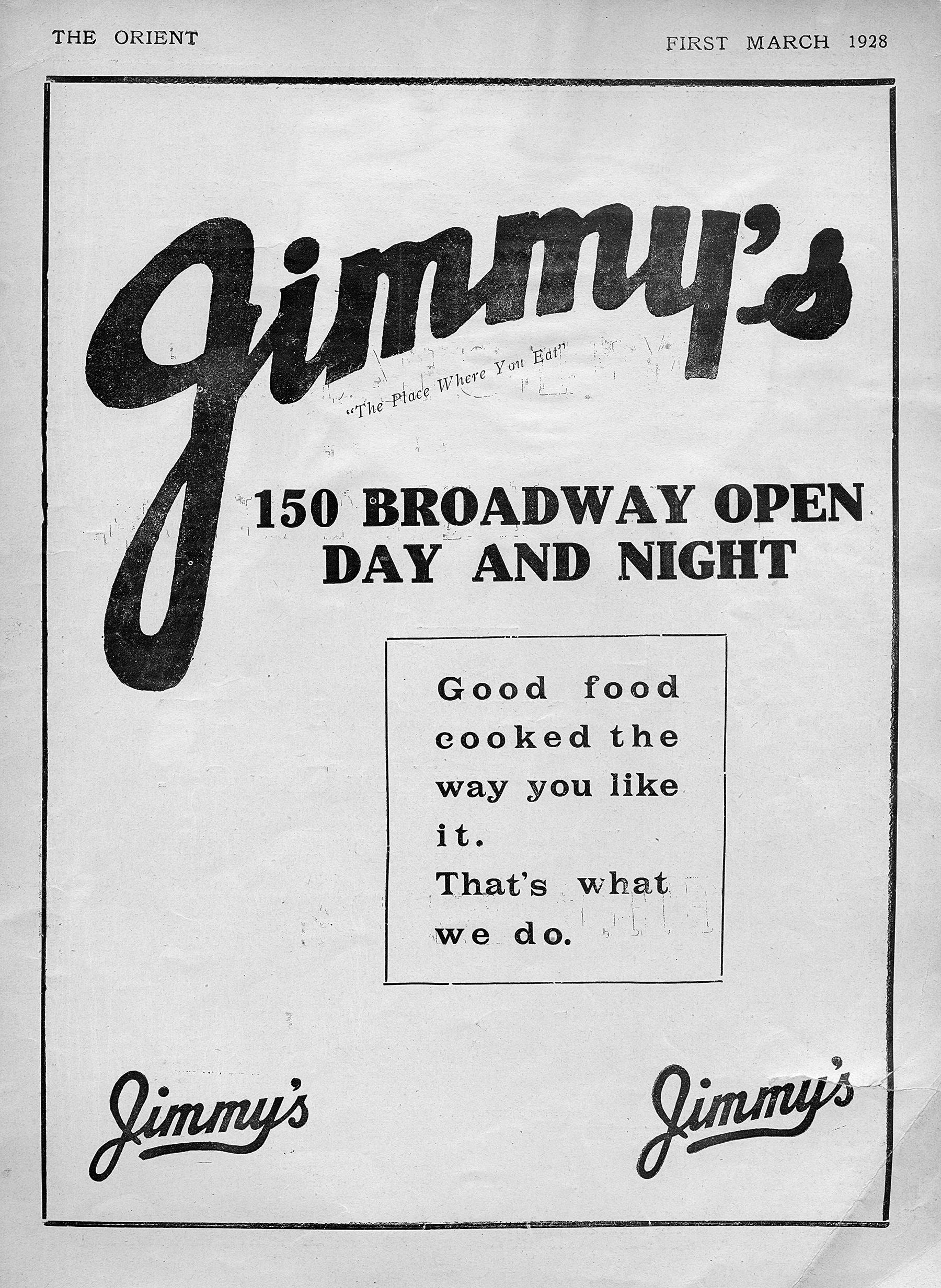

Cantonese restaurant Sun Ya was “probably the best spot to get a Chinese dinner” while Jimmy’s restaurant was “Where most foreigners eat and meet.” Jimmy’s was the forerunner of the fast-food giants operating in China today. The owner was a former U.S. Navy Sailor named Jimmy James.[11]

An advertisement for Jimmy’s restaurant in The Orient Magazine, March 1928.

Photo from the collection of Dirk Salverian.

A similar 1936 article in Leatherneck magazine states that “the Fourth Marine is furnished ample social life within his own organization. Weekly dances are held during the winter months. The best entertainers that can be obtained put on excellent floor shows and the crowds must be limited so they will have room to perform. Bridge parties weekly at the Navy ‘Y’ . . . the large lobby is crowded every Monday evening, and the competition is keen. Enlisted men’s clubs of the highest caliber round out the social opportunities for men in the Regiment.”

The 4th Marines Club in Shanghai.

Jacob L. Craumer Collection (COLL/1958), Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

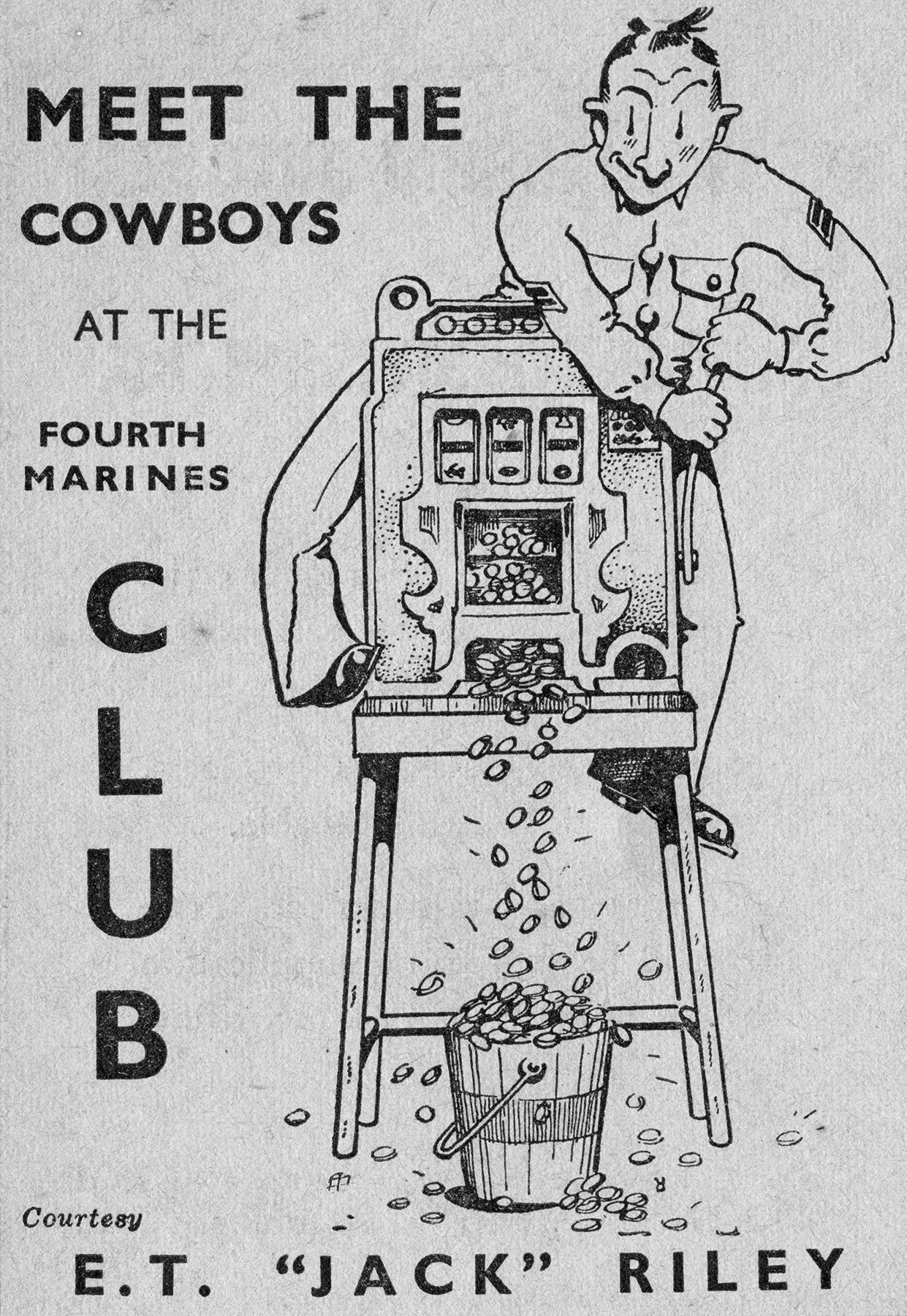

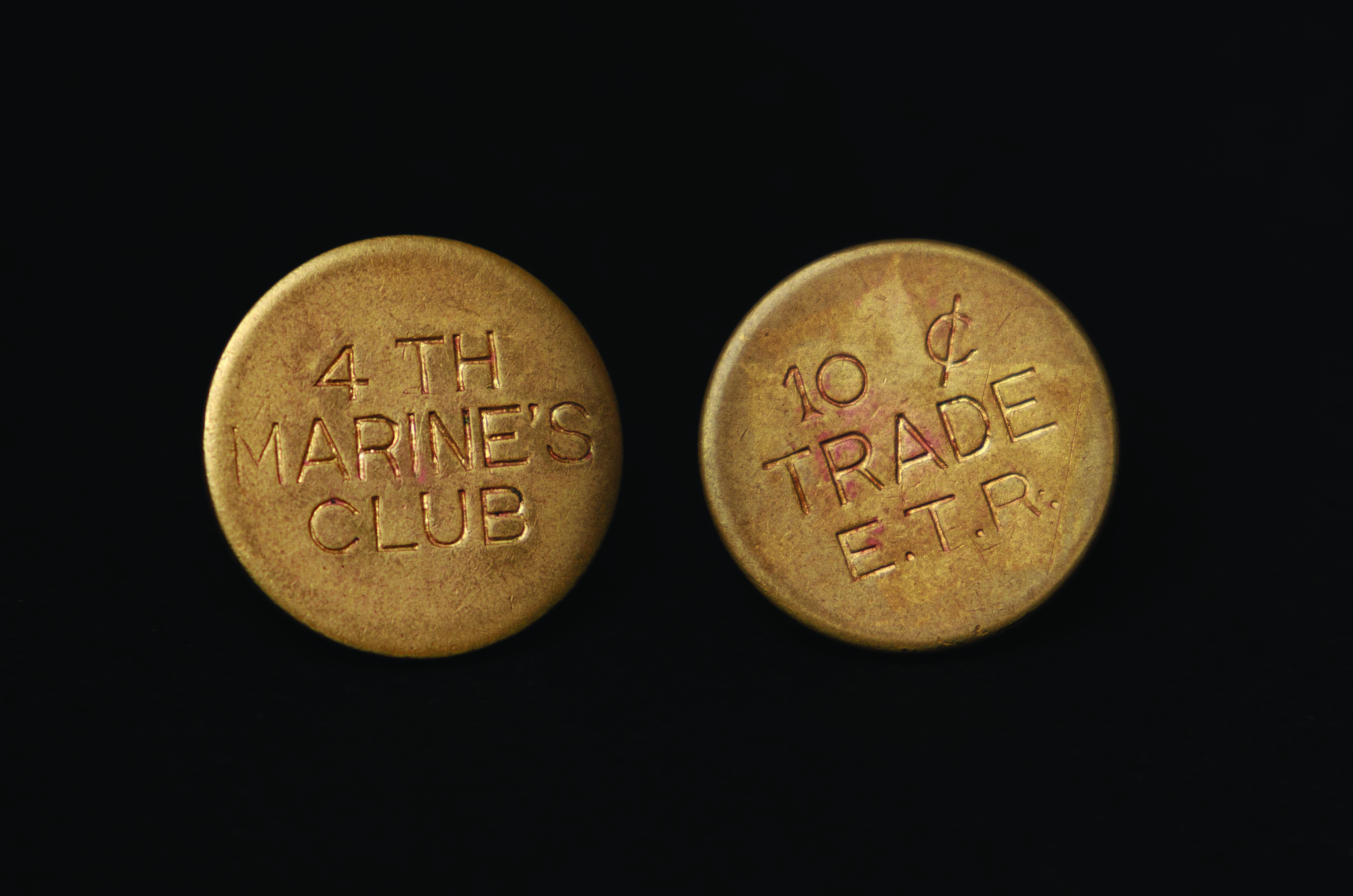

The 4th Marines Club in Shanghai was established in 1938. It was a large complex with a bowling alley, a theater, a restaurant, a ballroom, multiple bars, and plenty of slot machines to entertain any Marine looking for something to do during their down time. The club was owned and operated by a curious Shanghai civilian who went by the name of Edward Thomas Riley. His initials “ETR” appeared on the back of all the club’s tokens. He was born Fahnie Albert Becker in Colorado and was known by many aliases throughout his life. He was introduced to Shanghai while on the Yangtze River Patrol during a stint in the U.S. Navy. After his return to the United States and discharge from the Navy, Riley was arrested and sentenced to 25 years in prison for his role in a robbery and attempted kidnapping. He escaped after two years, burnt his fingerprints off with acid, and made his way back to Shanghai, where he established an empire based on gambling, crime, and debauchery. He became known as the “Slot Machine King,” and at the height of his power he controlled all the slot machines operating in the International Settlement. This included, of course, the slot machines at the 4th Marines Club.

An advertisement for Edward Thomas Riley’s slot machines at the Fourth Marines Club.

Walla Walla Newsweekly 13, no. 6 (13 July 1940), 6.

A club token used in the slot machines at the 4th Marines Club in Shanghai. Edward Thomas Riley’s initials appeared on the back side of all the club’s tokens.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

Riley’s association with the Marines in Shanghai went beyond the proprietorship of their club. Nefariously, of the Marines who deserted from their station while in Shanghai, many joined the “Friends of Riley” and transferred their loyalty from the Corps to the kingpin who had ingratiated himself with the young China Marines.[12]

International Friendships and Camaraderie in China: The Green Howards

The wonders of international life in China were not limited to Asian experiences. Duty in the nation also provided Marines with the opportunity to meet fellow servicemembers from around the Western world. The servicemembers of many different military forces fostered unique relationships that included a tradition of friendly competition, sports, and recreation with the U.S. Marines. The 4th Marines developed a particularly strong friendship with the men of a well-known Yorkshire regiment of the British Army called the Green Howards.

Captain Lemuel C. Shepherd Jr. (later to become the 20th Commandant of the Marine Corps) served as the adjutant for the 4th Marines when stationed in China in the 1920s. He was impressed by the British battalions. He especially enjoyed the exchange of mess nights with the British. As the regimental adjutant, he was responsible for conducting the 4th Marines’ parades. The 1st Battalion of the Green Howards had a fine fife and drum corps that Shepherd was very impressed with. In November 1927, the Shanghai municipal council provided the 4th Marines with musical instruments that included drums, fifes, and piccolos, and the new musical assemblage was named the “Fessenden Fifes” after Sterling Fessenden, president of the council. The bandmaster of the Green Howards taught the Marine musicians how to play the fifes provided. Once a week, the 4th Marines paraded through Shanghai to the beat of the Fessenden Fifes’ music. When the Green Howards left Shanghai, the Fessenden Fifes marched them down to the Bund and onto their ship.[13] The 4th Marine Regiment thereby became the only unit in the Marine Corps equipped with a fife and drum corps.[14]

Chinese Souvenirs

While enjoying the “China Marine” lifestyle, enlisted Marines were able to make their money go much further in the Far East. With vast numbers of foreign tourists and citizens living in the international settlements, local Chinese entrepreneurs, store owners, and tradesmen set up operations in these economic zones to profit from the foreigners’ stable incomes. Because of the relative wealth of foreigners, these Chinese entrepreneurs were often highly talented—certainly more so than those usually looking to make a quick buck off military servicemembers.

The back and front of an embroidered smoking jacket that was purchased in China by Cpl Alvin Honken.

Photos by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

A sterling silver engraved plaque, which reads: “From Lieutenant Colonel F.F.I. Kinsman and Officers 2nd Battalion the Green Howards to the Officers, Fourth U.S. Marines to commemorate their service together in Shanghai, 1930–31.”

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

It was not uncommon for Marines to purchase and bring back mementos or souvenirs to proudly document their service overseas. Decorative souvenir garments were popular with Marines both before and after World War II. Marines often admired the work of local Chinese craftsmen and tailors who embroidered beautiful designs featuring animals, dragons, and other figures and patterns on clothing. Many designs and iconography became associated with a specific local tailor or region in China. One of the more decorative textiles that Marines were known to have purchased included colorfully embroidered smoking jackets that are illustrative of classic Chinese needlework of the period. They are tangible reminders of a special era in the cultural history of the Corps.

An advertisement for the Teh Ling Company in Peking, China.

American Embassy Guard News 5, no. 9 (1 July 1937).

A custom engraved lighter.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

Local Chinese craftsmen also embroidered beautiful designs on the covers of photo albums, personalizing them for each Marine to document their service in China. Chinese craftsmen often became known for their signature designs, and it was not uncommon for Marines to admire the craftsmanship of the work done on a piece owned by a fellow Marine. Quickly, word of the skills of the local tailors and craftsman spread from one Marine to another.

A souvenir of enlisted Marine Alexander Glus’s service in Peking, China.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

Marines also visited shops such as Teh Ling in Peking and Tuck Chang in Shanghai, both of which sold jewelry, watches, rings, sterling silver cigarette cases, engraved lighters, and swagger sticks featuring detailed decorations, many of them exotic and mysterious looking dragons. These popular shops also produced sterling silver trophies for sporting events such as polo and marksmanship and shooting competitions. Teh Ling’s shop was located on Morrison Street in Peking, not far from the Legation Quarter, which was home to the diplomatic community and the guard forces that protected them. The business specifically produced items marketed toward U.S. Marines stationed in the city. He was known for producing high-quality items that made him a favorite among the Marines serving at the American Legation before and after World War II.[15]

Custom cloisonné napkin rings belonging to enlisted Marines William Williams (left) and Julius Papas (right).

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

Smoking was the norm for men and women in the 1930s, and it was considered fashionable to carry one’s cigarettes in a cigarette case. Although cases could be made from varying materials, those made of silver seemed to have been very popular at the time in both the United States and abroad. While in China, Marines who smoked often purchased silver lighters and cigarette cases decorated with dragons. These were also personalized by engraving the owner’s name or initials and the location where they were serving. Small items like these were easy to purchase and send home to girlfriends, friends, and family as gifts.[16]

Marines also purchased custom engraved pewter drinking mugs and personalized cloisonné napkin rings that featured their names, dates of service, the names of clubs or duty stations, and dragons curving around the sides. Some of these items were tied to membership in Marine Corps clubs such as the Sergeants Mess.

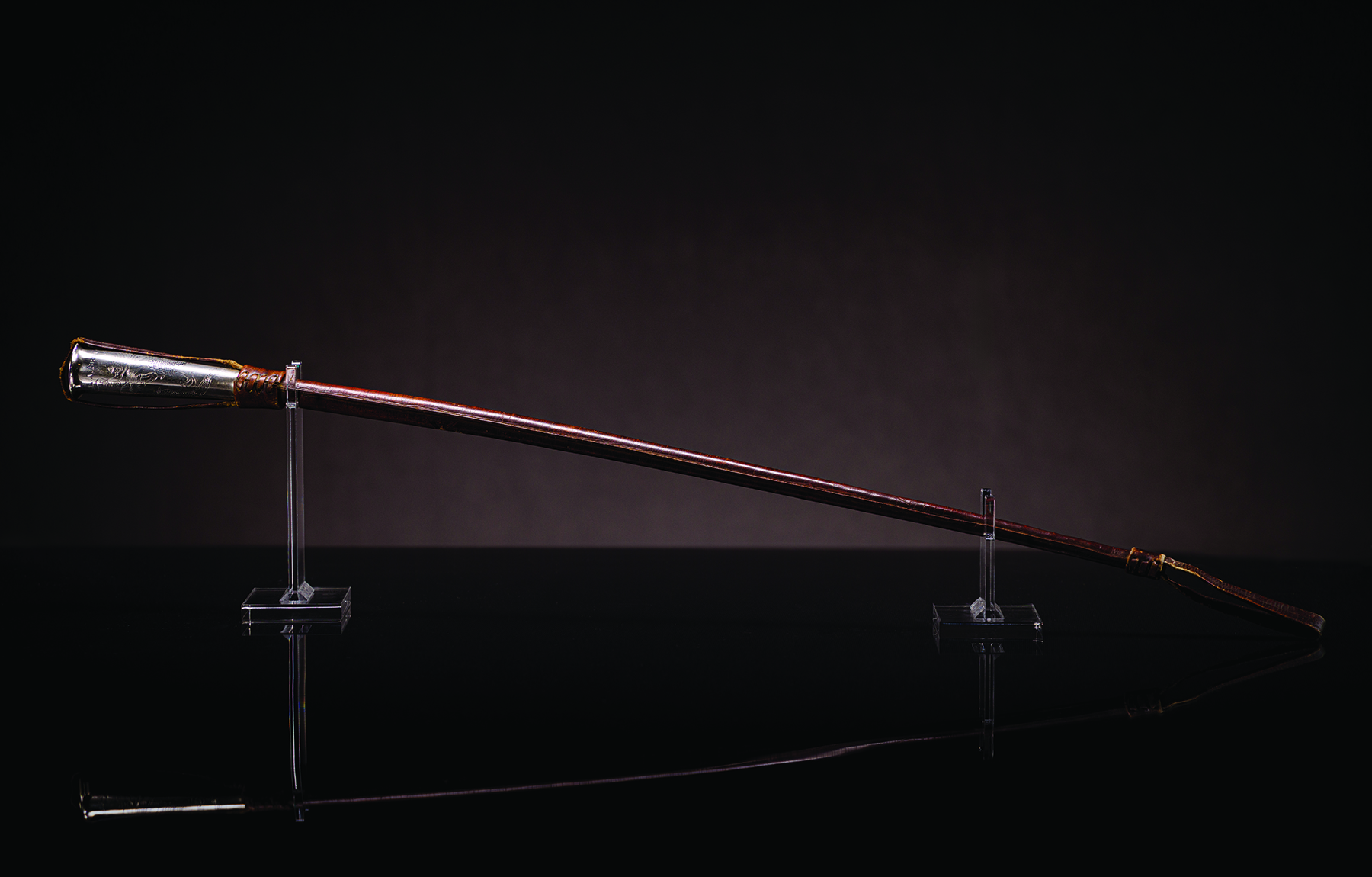

While in China, many Marines also purchased custom engraved swagger sticks and riding crops for personal use. Marines used canes, riding crops, and swagger sticks since the mid-nineteenth century. According to a reference file held by the National Museum of the Marine Corps,

The first official sanction for this custom was given in 1915 when Marines, both commissioned and enlisted, were authorized to carry swagger sticks when on recruiting duty to increase military bearing and appearance. By 1922 the Marine Corps uniform regulations authorized the swagger stick for all enlisted men on liberty or furlough and requested all commanding officers to encourage the carrying of the stick “to increase the smartness of the marine.” This directive continued in effect until the uniform regulations of 1937 when it was omitted without comment, but the practice had fallen into disuse in the early 1930s except among the Marines in China.[17]

Marines posing with their swagger sticks in Peking, China.

Jacob L. Craumer Collection (COLL/1958), Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

This “badge of authority” was typically only authorized for use by commissioned officers. Once the young, enlisted Marines stationed in China found that they too were officially sanctioned to carry swagger sticks, they found local craftsmen who could create personalized custom pieces with dragons engraved on the handles and curling around the length of the piece, along with the Marine’s name or initials affixed on silver plates on the sides or engraved on the top.

Maj Luther A. Brown’s personal swagger stick.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

Maj Luther A. Brown’s personal swagger stick (engraved detail).

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

Maj Luther A. Brown’s personal riding crop.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

Maj Luther A. Brown’s personal riding crop (engraved detail).

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

The End of an Era: World War II and the End of the China Marines

Due to the worsening political situation between the United States and Japan and war in Europe in the late 1930s, several of the countries represented in the Legation Quarter left Peking. British military forces departed the legation in August 1940, leaving U.S. military forces as the main foreign stronghold in the Legation proper. With the United Kingdom at war with Germany, British forces “were more urgently needed elsewhere . . . it was felt that the force maintained in North China was inadequate to resist a serious attack from the Japanese.”[18]

The departure of the British forces from the Legation Quarter marked a significant turning point in this history. The U.S. military forces in Peking, particularly the Marines, were left as the primary foreign military presence in the area. However, escalating tensions between the United States and Japan as well as the strategic disadvantages regarding a potential Japanese assault against U.S. forces in China prompted a reevaluation of their position as well.

Shortly before the entry of the United States into World War II and the onset of the Pacific War following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on 7 December 1941, the United States’ strategic imperatives in Asia shifted dramatically. This focus moved toward reinforcing more pivotal locations in the Pacific, which led to the decision to withdraw the U.S. Marines from China. By November 1941, anticipating the inevitable conflict with Japan, orders were issued for the withdrawal of the Marines to the Philippines, which were deemed more strategic for the defense of American interests in the Pacific.

The task of overseeing the American Legation and remaining American interests in Peking was left to a small group of U.S. diplomats and a minimal military presence, essentially marking the end of an era. These individuals were soon forced to surrender to the Japanese forces that swept through the region in December 1941. The capitulation of the remaining U.S. military and diplomatic personnel symbolized the effective conclusion of the Marine Corps’ longstanding presence in China, a period often romanticized and remembered for the service and sacrifices of the China Marines.

The withdrawal and subsequent surrender of these U.S. personnel to the Japanese not only marked a strategic pivot in the U.S. military’s focus during World War II but also symbolized the end of the unique role of the China Marines in American military history. The presence of Marines in China, which had begun in the nineteenth century, was characterized by their duty protecting American legations, citizens, and interests during turbulent times in Chinese history. The end of this era coincided with broader geopolitical shifts during World War II, leading to the reconfiguration of global powers and the onset of the Cold War, further distancing the U.S. military from its former roles in China.[19]

At the end of World War II, Marines from the 1st and 6th Marine Divisions served on occupation duty in China to assist with the surrender of Japanese forces and supervise the repatriation of defeated Japanese troops from 1945 to 1949, while the Chinese Civil War was raging throughout the country.[20] In an October 1945 Chinese edition of Stars and Stripes newspaper, an article states that “the troops of the 1st Marine Division entered Tientsin to assume police duties in the hotspot where Chinese Nationalist and Communist troops have been at bayonet points. Cheering Chinese lined the Hai River banks (river that connected Peking to Tientsin) as units of the Marine Division poured ashore.” Many Marines had just taken part in a brutal five-year-long war across the Pacific and now found themselves in what was once a coveted duty location serving as peacekeepers between the Chinese Nationalist and Chinese Communist forces, thinking that the war was supposed to be over and yet it was not. The Marines could only hope that things would soon return to the “normal” of years past. To their disappointment, they never did. Nothing would ever be the same in China.

Plans for the withdrawal of the Marines from China began in late 1946, and Marines began returning to the United States in 1947. Tsingtao became the only Marine Corps duty station in China on 1 September 1947, when the rear echelon of the 1st Marine Division left for the United States and the remaining Marines combined under a new command in Tsingtao. Their job was to ensure the security of U.S. naval training activities—Fleet Marine Force, Western Pacific, commanded by Brigadier General Omar T. Pfeiffer.[21] The Marines in China were able to take liberty and enjoy some social and recreational opportunities, but the ceaseless hostilities between the Nationalist and Communist forces continued with increasing violence, lessening these kinds of opportunities for the Marines who remained to maintain the security and safety of U.S. civilians and troops in the country. For all intents in purposes, by 1947, “Magic China” was no more.

Endnotes

[1] George B. Clark, Treading Softly: U.S. Marines in China, 1819–1949 (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2001), 1.

[2] J. Travis Monger, “USS Congress Becomes the First U.S. Navy Ship to Visit China, 1819,” Sextant (blog), 10 August 2022.

[3] China was then known as the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911), founded by the Manchus, who were a separate ethnic group from the Han. “Qing Dynasty, 1644–1911,” National Museum of Asian Art, accessed 14 May 2023.

[4] “Treaty of Wangxia (Treaty of Wang-Hsia), May 18, 1844,” University of Southern California U.S.-China Institute, accessed 14 May 2023.

[5] “Magic China” (M.C.P.B. 70607), Marine Corps Official Recruiting Brochure, 12 June 1937.

[6] “End Strengths, 1795–2015,” Marine Corps History Division, accessed 14 May 2024.

[7] Michael J. Moser and Yeone Wei-Chih Moser, Foreigners within the Gates: The Legations at Peking (Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, 1993), 119. See also the 1924 Fei Shi map of the Foreign Legation Quarter and its surrounding area in Peking (Beijing), China, at Geographicus Rare Antique Maps, accessed 14 May 2024.

[8] William Howard Chittenden, From China Marine to Jap POW: My 1,364 Day Journey through Hell (Paducah, KY: Turner Publishing, 1995), 33.

[9] Information taken from Registers of the Commissioned and Warrant Officers of the United States Navy, U.S. Naval Reserve Force and Marine Corps (Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, 1923–40), hereafter Navy Register. Navy Register (1923), 354; Navy Register (1930), 486; Navy Register (1935), 576; and Navy Register (1940), 678. Monthly pay based on first enlistment period and consolidated pay rate information found in a chart compiled by Erik Maddox.

[10] Chittenden, From China Marine to Jap POW, 57–58.

[11] Bill Savadove, “A Short History of Gluttony in Shanghai,” Historic Shanghai (blog), accessed 14 May 2024.

[12] Summarized from Andrew David Field, “The Fate of Jack Riley, Shanghai’s Notorious Slot Machine King,” Shanghai Sojourns (blog), 29 June 2018; China Weekly Review, 12 April 1941; “China: Tough Taipan,” Time, 28 April 1941; and Paul French, City of Devils: The Two Men Who Ruled the Underworld of Old Shanghai (New York: Picador, 2018).

[13] BGen Edwin H. Simmons, USMC (Ret), “Remembering General Shepherd,” Fortitudine 20, no. 2 (Fall 1990): 5.

[14] James S. Santelli, A Brief History of the 4th Marines (Washington, DC: Historical Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1970), 16.

[15] Dirk Salverian, “Teh Ling: Silversmith to the China Marines,” U.S. Militaria Forum, 14 May 2023.

[16] Salverian, “Teh Ling.”

[17] Curator Reference File on Swagger Sticks (Document A03E-hvm), National Museum of the Marine Corps, 20 September 1952.

[18] “British Withdraw Troops from China; U.S. Forces Remain,” New York Times, 10 August 1940.

[19] For place names in China and similar references, this chapter uses the names used in U.S. and Western sources from 1920 to 1941, which tended to follow the Wade-Giles romanization system for Mandarin Chinese.

[20] Clark, Treading Softly, 131.

[21] Santelli, A Brief History of the 4th Marines, 23.