Chapter 12

Front-Row Spectators to the Start of World War II

The Soochow Creek Medal, 1937

By Owen Linlithgow Conner, Chief Curator

Featured artifact: Soochow Creek Medal (2021.24.1)

There were several versions of the Soochow Creek medal created by Marines in China. This version was created in 1937, following the Battle of Shanghai.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

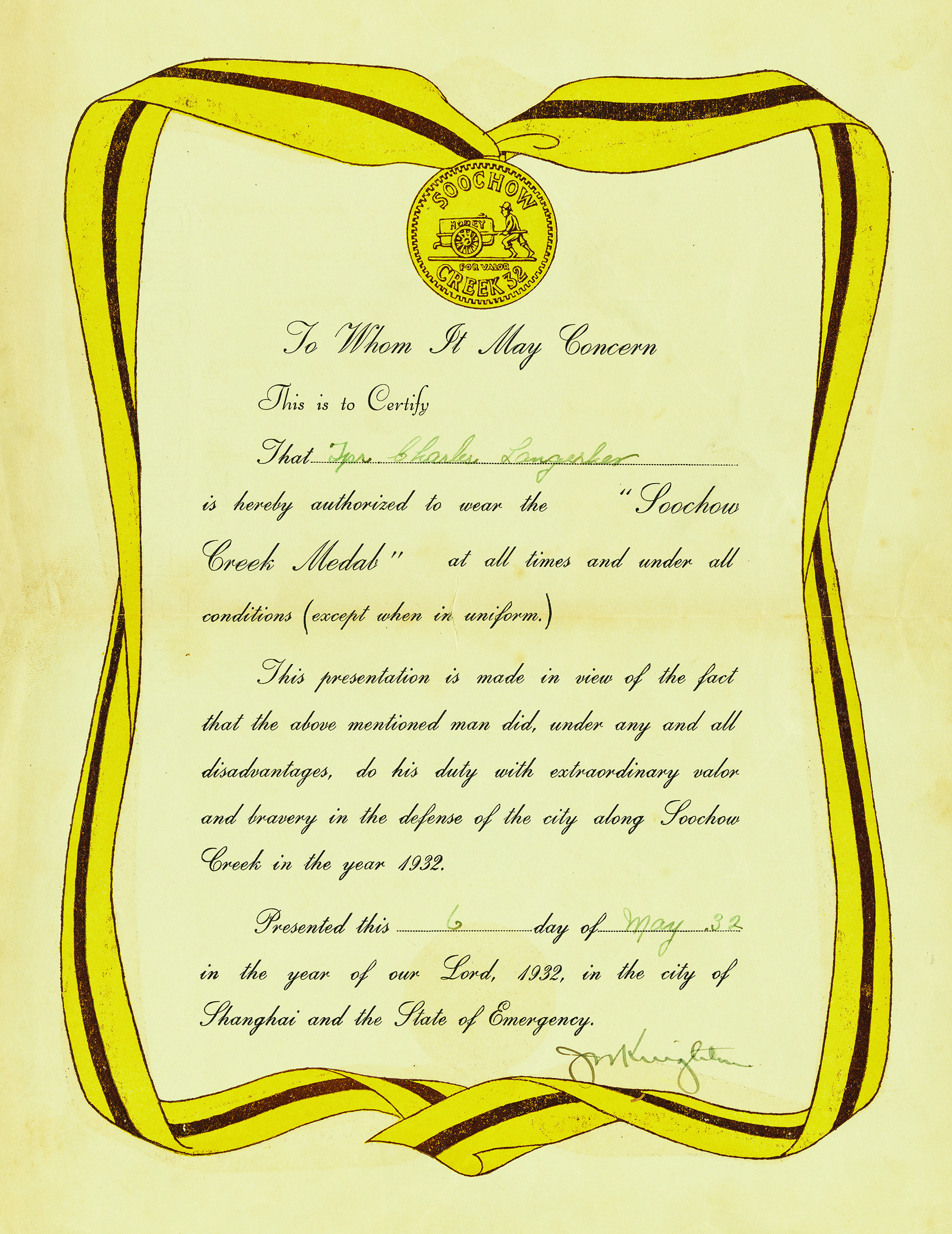

All versions of the Soochow Creek medal came with their own official certificate. This is an example of the 1932 award.

Marine Corps History Division.

In 1937, the 6th Marine Regiment was rushed to Shanghai, China, to reinforce the 4th Marine Regiment there. The city was set to play a key role in a massive battle. Following an international incident between Chinese and Japanese forces on the Marco Polo Bridge in Beijing, a chain of uncontrollable events was set in motion. With a brigade of Marines serving as spectators, a full-scale war between the two Asian powers was about to erupt.

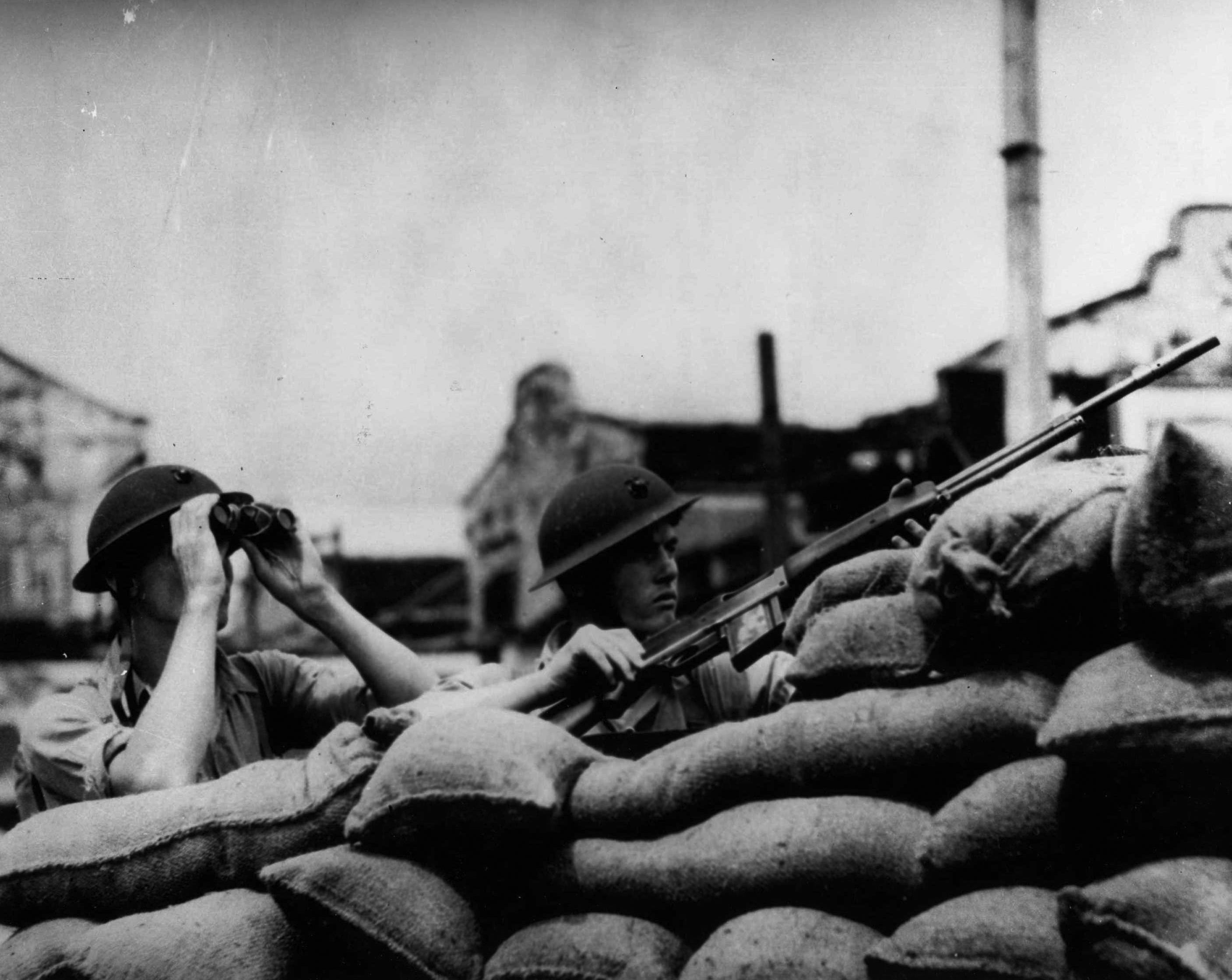

Marines stationed at their defensive positions along Soochow Creek in 1937.

Marine Corps History Division.

A Marine stands guard while watching the battle between the Japanese and Chinese armies.

Marine Corps History Division.

In Shanghai, Chinese generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek and his National Revolutionary Army occupied the city. This would be the Chinese army’s first major stand against the might of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA). Recognizing the importance of the battle, the Chinese Nationalists committed a large portion of their most elite, well-trained divisions. As a result, the Battle of Shanghai became one of the largest engagements of the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–45) and involved nearly 1 million combatants.

As modern historians revisit Western-dominated narratives of World War II, it is now argued that this epic battle marked the true beginning of the Second World War. Ironically, the U.S. Marine Corps was at the center of it all, but no Marines ever fired a shot. Their mission was to protect their sector of the foreign settlements along the Suzhou Creek (a.k.a. the Wusong River and in the 1930s to Westerners as Soochow Creek). In recognition of this unusual “service” during the battle, the Marines commissioned an unofficial medal. First struck in 1932 and then restruck in 1937, the Soochow Creek Medal celebrates their ignominious role in one of the greatest but least-known battles of World War II. The artifact is a fascinating reminder of the strange role that Marines played in one of the most unusual “battles” in the 250-year history of the Corps.

Marines in China remained neutral during the fighting between Chinese and Japanese forces.

Marine Corps History Division.

Interactions between Marines and Japanese soldiers in Shanghai ranged from cordial to tense on any given day.

Marine Corps History Division.

Background to the Battle

China long served as the epicenter of conflict between Asian and colonial powers. Throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Empire of Japan gradually embedded itself on the Asian mainland and sought to expand its presence there. In the process, a dramatic series of events began to unfold, eventually leading to the deaths of approximately 25 million people in Asia.[1]

Following Japan’s dominant victory over China in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–95), the IJA made no secret of its disdain for the convoluted series of independent, corrupt, and warlord-led provinces that nominally amounted to the Chinese “nation.” Japanese military planners, set on establishing a new empire of their own, believed that China was a pseudo-nation in decline, ready to be conquered and exploited. The Japanese were not alone in seeing the potential for exploiting China. In fact, they were late to the game. For decades, European nations and the United States had established enclaves of commerce and legations in Chinese cities such as Shanghai, Hong Kong, Tianjin, and Beijing. Following the Boxer Rebellion (1899–1901), the Chinese were forced to allow foreign soldiers and marines to protect legations, communications, and railways. However, as time went on, Japan’s “China Garrison Army” grew to an unprecedented size, dwarfing the other nation’s numbers and violating the terms of the original agreements.[2] The Japanese military was determined to make up for lost time versus the other Western nations. When renegade IJA forces seized all of Manchuria in 1932, they established a new vassal state of Manchuko and turned their sights on the rest of China. By 1937, the Japanese had conquered much of the country’s north, all the way to the Great Wall.

Standing in the way of the Japanese Empire was a fragmented and dysfunctional coalition of Chinese forces. The largest and most powerful belonged to the Kuomintang, or Nationalist Party. They were led by Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, a former military academy commandant and decorated officer who had risen through the ranks to assume control and national prominence. However, his coalition of forces were far from ideal. Among the various dysfunctional factions of the Nationalist Party were an odd mixture of conflicting personalities, ideologies, and competing strategies.[3] In addition to confronting Japanese expansion, Chiang’s Nationalists had fought an earlier civil war against Chinese Communists and then held a tenuous truce with their leader, Mao Zedong.[4]

At the time of the Battle of Shanghai, Chiang commanded more than 2 million soldiers. However, their impressive size was significantly off set by the varying levels of training, quality, and loyalty of these forces. The backbone of the Nationalists consisted of approximately 300,000 elite soldiers who were well-armed and trained by German advisors. An additional 600,000 well-equipped soldiers belonged to assorted regional leaders who had been traditionally loyal to Chiang’s orders. The last portion of Chiang’s army consisted of around 1 million soldiers from various regions with limited obedience to the Nationalists or their interests. This included approximately 50,000 Chinese Red Army soldiers, of which a little more than one-half were properly equipped or armed.[5]

The Battle of Shanghai, 1937

By August 1937, full-scale war was inevitable. For weeks, the Imperial Japanese Navy sent more than 30 warships with their accompanying naval infantry to Shanghai. In turn, Chiang moved his German-trained 87th and 88th Divisions into defensive positions in the city’s streets. Unlike North China, the city of Shanghai was a symbolic center of China. It was a modern city with key industrial capabilities. It was also a city with a highly visible foreign presence due to the large International Settlement there. On 13 August, Chiang ordered his army to hold the city at all costs. Almost immediately, a massive refugee and humanitarian crisis ensued. Thousands of Chinese citizens fled their neighborhoods, seeking to find relative shelter in or near the foreign settlements.[6]

The fighting commenced on 14 August, when Chinese Nationalist aircraft took flight from their airfields to surprise the Japanese warships and sink them. Tragically, whether due to pilot error or mechanical malfunction, numerous bombs and torpedoes missed their mark. Instead of striking the Japanese cruiser Izumo (1900), the munitions landed in the middle of one of Shanghai’s busiest market streets, killing scores of Chinese civilians and foreign tourists.[7] The bodies of the dead were stacked near the famous Palace and Cathay Hotels, the latter being a popular attraction for U.S. Marines on their off-duty hours. With all hope of tactical surprise now eliminated, both sides continued to reinforce and dig in. When fierce urban combat erupted, casualties were heavy on both sides, and the city began to be leveled by Japanese artillery and air power. Unlike previous “incidents” however, the Chinese were now prepared to fight a total war that would be measured not in weeks or months but in years.[8]

The battle raged for more than three months. Large swaths of Shanghai were reduced to rubble by Japanese bombardment. Even the International Settlement was not spared. On one occasion, a Japanese bomber deliberately struck a tramcar, killing dozens of Chinese men, women, and children. Other inadvertent stray munitions also struck the allegedly “safe area.” Foreign journalists were taken to the city’s famous North Station to see the destruction of its railways. After numerous attempts to retreat or regroup, the Nationalist Army began to concede defeat by November 1937. As the heroic remnants of Chaing’s army withdrew, a bizarre sight was revealed to the International Settlement’s defenders. Outside their protected enclave, the entire city lay devastated. Soochow Creek served as the geographical boundary for the spectacle. On one side, the foreign streets and homes remained unscathed and bustling, while the city on the other side of the river resembled a “barren moon-landscape.”[9] With approximately 750,000 Chinese soldiers defeated by 250,000 Japanese soldiers, the Battle of Shanghai remained the largest urban action of World War II until the Battle of Stalingrad in 1942–43.[10] The attacking Japanese forces suffered 40,372 casualties, 9,115 of whom were killed in action. Chinese casualties were more severe, with official records suggesting that 187,200 were killed or wounded in action. Subsequent studies by historians, however, suggest that the number was much higher, nearing a quarter of a million.[11]

Combat Post Number 4 was one of 58 fortified positions maintained along Soochow Creek during the battle.

Marine Corps History Division.

The Second China Incident: From the Marines’ Perspective

For the U.S. Marines defending Shanghai, the massive battle was a surreal event. Despite its size and potential geopolitical impact, it was commonly referred to as the “Second China Incident.” The first “incident” between Chinese and Japanese forces in Shanghai had taken place in 1932, and like its successor, it caused the Marines to similarly reinforce and fortify their defense sector. This was a perilous time, as the incident caused numerous near-direct confrontations with Japanese forces. On several occasions the Japanese attempted to infiltrate neutral international settlements to attack Chinese units from their flanks. This made things extremely difficult for the 4th Marines, who sought to avoid assisting Japan’s blatant aggression and wished to remain neutral.[12]

Recalling the issues that arose in 1932, the U.S. government and Marine Corps paid considerable attention to the defense of the International Settlement in 1937. Working closely with the local Shanghai Volunteer Corps, U.S. and British forces again took up defensive positions in their assigned sectors.[13] On the American side, the effort was led by the 4th Marines, who began building sandbag bunkers and placing barbed wire to prevent any infiltration of the foreign area from either Chinese or Japanese troops. Prior to the incidents of 1932 and 1937, U.S. defense plans focused on the threat of a Chinese attack on the International Settlement, as had happened during the Boxer Rebellion. These new battles between the Nationalist Chinese and an ever-increasingly aggressive Japanese military brought more grave concerns—the worst being that the Japanese might decide to ignore the foreign powers’ neutrality and attempt to take over the area by force.[14]

The Marines’ first experiences of the Battle of Shanghai occurred as they were still fortifying their positions. They were present when two Chinese bomber aircraft missed their intended target, the Japanese cruiser Izumo, and stray bombs landed within the settlement, killing numerous French and other foreign citizens.

Now aware of the danger, the Marines erected 58 defensive positions along the 6,500 meters of waterway. Within this line, they positioned nearly 30 machine guns and had plans for a defense in depth, should the occasion arise in which they needed to fall back. Initially numbering a little more than 1,000 Marines, the regiment was soon reinforced. The Marine detachment from the heavy cruiser USS Augusta (CA 31), flagship of the U.S. Navy’s Asiatic Fleet, provided around 100 Marines and armed sailors to add to their numbers, while another small contingent hastily arrived from Cavite, Philippines, shortly thereafter.[15]

By mid-August, the Nationalist Chinese forces began to lose ground to the Japanese. The Marines could do little but watch and try to avoid misfired bullets and shells that occasionally flew in their direction. A few Marines and one Navy corpsman were lightly wounded, but no serious casualties occurred. On 19 September, the first significant Marine reinforcements arrived. After a month on the settlement’s front lines, the 4th Marines were partially relieved. The transport USS Chaumont (AP 5) delivered the 2d Marine Brigade headquarters along with the attached 6th Marines, more than doubling the Marines’ defensive numbers.[16]

Private Earl A. Lavier of the 6th Marines observed the fighting. In a letter sent home to his family and later republished in the Detroit Free Press newspaper, he recounted what he saw, noting that “airplanes [were] dropping bombs on the Chinese every day.” The shelling was so intense that Lavier and his fellow Marines could not sleep in their sandbagged positions. Situated just two city blocks from the raging battle, every window in the Marines’ nearby billet was shattered by concussions from the blasts. The true nature of the coming war in Asia was also seen by Lavier, who observed a horrifying scene: “The [Japanese] lined up a lot of Chinese and shot them. . . . We were just across the creek, about 40 feet away, and could not do a thing to help them. . . . It was not a very nice sight.”[17]

As Japanese forces pushed the Chinese Nationalists past the defensive sector of the Marines and other foreign powers, tensions began to ease. As early as October 1937, the “so-called war fever” came to an end. The 4th Marines in Shanghai returned to playing sports, with victories by their softball and baseball teams taking up most of their news in Leatherneck magazine that month.[18] The reinforcements with the 2d Marine Brigade headquarters and the 6th Marines departed on 17 February 1938, returning the 4th Marines to their uncontested and unofficial title as the sole “China Marines.”[19]

The Story of the Soochow Creek Medals, 1932 and 1937

During both the 1932 and 1937 “China incidents,” Marines did their best to make light of their unusual situation. The crisis of 1932 inspired their first efforts at creating a humorous, unofficial medal in recognition of their service. The first references to the creation of the award came in the 13 February 1932 edition of the China Marine’s newspaper Walla Walla. In it, the tongue-in-cheek columnist asks:

Now that the war is on, “when do we get our medals” is one of the natural questions which is being asked nowadays—particularly around Headquarters where other men have time to think about such things now and then. Well, men, here it is. The latest suggestion for a medal as struck by G. Whiz Wolfe and approved unofficially by all who have seen it. The ribbon is to be made of brilliant yellow silk—and the disc itself—well, is it appropriate?[20]

A 1937 Soochow Creek medal (left) is pictured next to an original 1932 version of the medal.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

An original example of the 1932 medal with its humorous depiction of a Chinese civilian pushing a “honey bucket.”

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

The reverse-side inscription on Pvt Earl A. Lavier’s 1937 medal.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

Regarding the latter question, the writer was referring to the first incarnation of the medal’s medallion. It depicts a Chinese civilian pushing a crude wheelbarrow with the word “honey” written on it. This scene was a comical rendition of one of the less pleasing aspects of duty at Soochow Creek. As a tributary of the Yangtze River, the creek also served as a collection and transportation hub for human waste from the city of Shanghai. There, large sampans referred to as “honey barges” by the Marines carried the foul-smelling excrement to a nearby disposal area, where local farmers would later harvest the landfill in wagons for use as agricultural fertilizer.[21]

The reverse of the medal was cast with the inscription:

PRESENTED TO

(Engraved with Marine’s Name)

FOR BRAVERY AND VALOR

BATTLE OF SOOCHOW CREEK

SHANGHAI 1932

A humorous award certificate issued with the medal noted that the decoration was to be worn “at all times and under all conditions (except when in uniform).”[22]

Marine Corps muster roll records from the era show that the fictitious designer “G. Whiz Wolfe” was Private Ronald D. Wolfe. Wolfe served as a member of Headquarters Company, 4th Marines, Marine Corps Expeditionary Force, Shanghai, China, from July 1930 to April 1932. Subsequent columns in the 15 and 30 April 1933 editions of Walla Walla provided additional clues to how the medals could be obtained and their cost, the most colorful of which stated:

Who among you have not dreamt of the deeds of “daring do,” who has not fought great battles? Who has not summoned his courage and taken his life in hand to wade into the midst of adventure and strife? Who has not at some time imagined himself crowned a hero before an admiring throng of captive maidens? . . . [Now] your chance has come to be decorated. To wear on your manly chest a distinguishing mark of bravery. Don’t be a common Marine, get a Soochow Creek Medal and be a hero. . . . No palpitating breast is complete without one. See your company clerk now and give him your order. There is only a limited amount of these medals that will be put on sale, so get your name in on that list. After these are gone there won’t be any more, and the price is only $2.00 Mex(ican).[23]

Where the original purchase of the medals came from, and who ordered them, remains unknown and undocumented today. The medals were available in both bronze and gold finishes. Many sources speculate that the vendor was possibly a local businessman named Tuck Chang. His jewelry and engraving shop often advertised in the 4th Marines’ newspaper with the sales pitch: “Marines, get your jewelry and medals where they are made right.” However, modern collectors believe that this is not the case due to the variety of medals and varying qualities found in many personal and museum collections.[24]

Despite the newspaper’s convincing sales pitch that “there won’t be any more” of the 1932 medals, the award reappeared following the Battle of Shanghai. The first editions of these medals remained unchanged, except for the new date of 1937, but a more conservatively designed version soon replaced the “honey bucket”-hauling “Chinaman” with a more officially acceptable Marine Corps, eagle, globe, and anchor design on the front. Sales continued to be strong for some time, with Marines often trying to acquire the awards Stateside even after transferring back home from the Far East. Medals were also purchased and engraved to wives and even the appropriately named regimental dog “Private Soochow.”[25]

These remarkable artifacts remain prized additions to any Marine collection dedicated to preserving the history of the glory days of the original China Marines. They also serve as a stark reminder to the days when Marines played their small role in the opening salvos of the greatest military conflict of the twentieth century in World War II.

Endnotes

[1] Richard B. Frank, Tower of Skulls: A History of the Asia-Pacific War, July 1937–May 1942 (New York: W. W. Norton, 2020), 9–11.

[2] Frank, Tower of Skulls, 5.

[3] Frank ,Tower of Skulls, 2–3.

[4] Frank, Tower of Skulls, 22.

[5] Frank, Tower of Skulls, 22–23.

[6] Rana Mitter, Forgotten Ally: China’s World War II, 1937–1945 (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013), 98–99.

[7] Mitter, Forgotten Ally, 100.

[8] Mitter, Forgotten Ally, 101.

[9] Mitter, Forgotten Ally, 102–6.

[10] Frank, Tower of Skulls, 32.

[11] Frank, Tower of Skulls, 35.

[12] George B. Clark, Treading Softly: U.S. Marines in China, 1819–1949 (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2001), 94–95.

[13] The Shanghai Volunteer Corps was a paramilitary unit organized after 1870 to protect the International Settlements in the city. Falling under the authority of the Shanghai Municipal Council, they were equipped by the British army and lead by an appointed officer. Various communities withing the settlement each contributed members to serve in subunits of the organization. These consisted of volunteers from the United States, Germany, Russia, Great Britain, and the Philippines, as well as a unit made up of Jewish members. Robert Bickers, “The Shanghai Volunteer Corps,” Robert Bickers (blog), 19 April 2013.

[14] Clark, Treading Softly, 110.

[15] Clark, Treading Softly, 111–12.

[16] Clark, Treading Softly, 112

[17] “It Happened in Michigan: Eyewitness to War,” Detroit Free Press, 26 December 1937; and Artifact File, Soochow Creek Medal 2021.24.1, National Museum of the Marine Corps, Triangle, VA.

[18] L. Guidetti, “Fourth Marines, Shanghai, China,” Leatherneck 20, no. 10 (October 1937): 20.

[19] James S. Santelli, A Brief History of the 4th Marines (Washington, DC: Historical Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1970), 19.

[20] Walla Walla, 13 February 1937.

[21] Ken Harrington, “Splat Attack Became Legend” (unknown source article, curatorial file, National Museum of the Marine Corps, n.d.), 68.

[22] Collection 766, Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

[23] “The Soochow Creek Medal,” Walla Walla, 15 April 1933.

[24] Dirk “Haig” Salverian, donor correspondence, 27 February 2024.

[25] “Who’s on the Asiatic Station,” Walla Walla, 5 October 1940.