Chapter 10

In the Highest Tradition

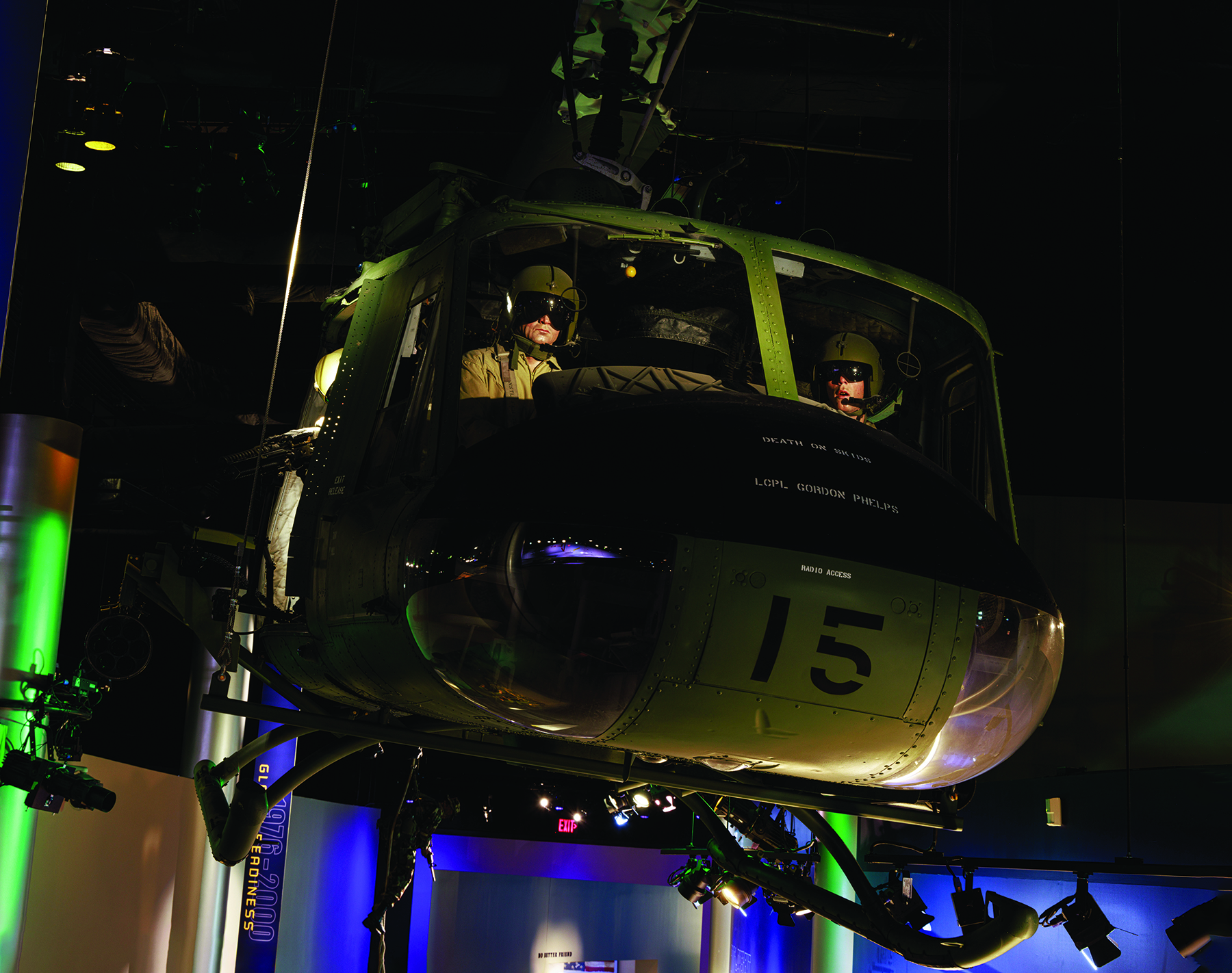

Captain Stephen Pless’s UH-1E

By Laurence M. Burke II, PhD, Aviation Curator

Featured artifact: Bell UH-1E Iroquois (1984.1797.1) in the National Museum of the Marine Corps’ Legacy Walk

Capt Stephen W. Pless’s Bell UH-1E Iroquois “Huey” gunship at the National Museum of the Marine Corps.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

The U.S. Marine Corps does not maintain dedicated combat search-and-rescue teams. Instead, this is a mission that any Marine helicopter squadron may be tasked with conducting. Even so, the rescue effort of Captain Stephen W. Pless in Vietnam in 1967, carried out in a helicopter not equipped to carry more than its own aircrew, is an anomaly. That fact, combined with the intense combat that Pless and his crew experienced as they rescued three stranded U.S. Army soldiers, resulted in a Medal of Honor for Pless and Silver Stars for each of his crew. The helicopter they flew that day is now on display at the National Museum of the Marine Corps.

On 19 August 1967, Pless and his crew—copilot Captain Rupert E. Fairfield Jr., Gunnery Sergeant Leroy N. Poulson, and Lance Corporal John G. Phelps—were flying a Bell UH-1E Iroquois helicopter gunship, BuNo 154760, callsign “Cherry 6.” They were scheduled to escort a Marine Sikorsky UH-34D Seahorse helicopter on an emergency medical evacuation (medevac) mission near Chu Lai. The UH-34D was having mechanical difficulties, so Pless decided to fly ahead. While on their way to the pickup, the crew heard a call for help: a U.S. Army Boeing CH-47 Chinook transport helicopter, with wounded aboard, had been forced down by enemy ground fire. The helicopter’s crew chief, along with three other soldiers for security, had gotten out to inspect the damage when a grenade exploded near the nose of the aircraft and National Liberation Front (NLF) forces began closing in. The Army pilot lifted off to find a safer spot to inspect his aircraft, but the four soldiers could not get back aboard in time and were left behind in close contact with the enemy. Once airborne, the pilot radioed his predicament and called for someone to help the soldiers left behind.

The crew of “Cherry 6” (from left to right): GySgt Leroy N. Poulson, gunner; LCpl John Phelps, crew chief; Capt Rupert E. Fairfield Jr., copilot; and Capt Stephen W. Pless, pilot.

Marine Corps History Division.

Responding to the call, Pless arrived over a beach about 1.5 kilometers north of the mouth of the Tra Khuc River (about 120 kilometers south of Da Nang) to find 30–50 NLF fighters surrounding the Army soldiers, some of them beating and bayoneting the Americans. Seeing no other aircraft in the area, Pless checked with his crew, who unanimously gave the thumbs-up to go down and help the soldiers. Pless made a low pass about 15 meters from the ground, at which point he saw one of the soldiers, Staff Sergeant Lawrence H. Allen, wave to the helicopter. Seeing this, Pless ordered Poulson, on the starboard-side door M-60 machine gun, to open fire. Fearing that he might hit the Americans, Poulson fired at the edge of the mob. This led the enemy to make a break for the tree line, at which point Pless pulled up, spun around, and fired all 14 of his white phosphorous rockets into the group. Pless then circled around and began firing his helicopter’s four fixed M-60s into the smoke from his rockets. Phelps called it “the most remarkable airmanship I’ve ever seen.”[1] Making multiple strafing runs, Pless managed to force the enemy back to the tree line, many times flying so low that mud kicked up by his gunfire soon covered his windshield. Running low on ammunition, Pless decided to land, despite his helicopter not being equipped to carry any more people.

Pless fired the last of his ammunition from his fixed guns at the enemy in the tree line and then spun the helicopter around to point out to sea. This put the helicopter between the wounded soldiers and the enemy, with the port side facing the enemy. Phelps, the door gunner on that side, fired bursts from his M-60 to keep the enemy at bay. Meanwhile, as soon as they touched down, Poulson unhooked from the aircraft and jumped out to aid the nearest wounded soldier—Allen—who, with Poulson’s assistance, was able to walk to the helicopter. Poulson then went out again for a second man, who was bigger and heavier than Allen and unconscious. Poulson kept sinking into the soft, powdery sand while trying to lift the lifeless soldier. Phelps and Fairfield both saw Poulson struggling and jumped out the starboard door to help him. As Fairfield exited the doorway, he spotted NLF troops less than 3 meters from the rear of the helicopter. Fairfield quickly dismounted the starboard door gun and killed them. He then ordered Phelps back to his gun to provide cover, while he and Poulson made slow progress dragging the second soldier back to the helicopter.

The two Marines then headed for the third casualty but were having problems moving him across the sandy beach. Pless ordered Phelps to leave his gun and help them. Phelps asked Allen if he thought he was able to use the door gun. Allan said yes, so Phelps gave Allen his spot at the door gun and jumped out of the helicopter again. Fairfield and Phelps carried the soldier by his shoulders and had their pistols in their free hands, firing back at the enemy, while Poulson carried the soldier’s feet. When an NLF fighter approached them with what Phelps believed was a hand grenade, Phelps dropped the soldier and emptied his pistol at the enemy, killing him. The three Marines were then able to get the third casualty into the helicopter. At this point, a U.S. Army UH-1B helicopter gunship appeared in the area, responding to the same call that had brought Pless to the aid of the trapped soldiers, and began making its own strafing runs to suppress the intense fire aimed at Pless and his crew.

Fairfield and Poulson then went for the fourth soldier, who appeared to be dead. Fairfield confirmed this by checking for a pulse and heartbeat and finding neither. He then tried to find identification tags but was unsuccessful. As Fairfield returned to the helicopter, a South Vietnamese H-34 medevac helicopter was seen approaching. Fairfield yelled to Pless that the H-34 could pick up the body; they should try to save the three wounded soldiers they already had aboard. Pless took off over the water to escape the NLF gunfire. He and his crew had been on the ground for about 5–10 minutes.

A gunship from Marine Observation Squadron 6 escorts two UH-34s as they lift off from a Vietnamese beach in October 1967.

Marine Corps History Division.

With the three wounded soldiers aboard, Pless’s UH-1E was at least 225 kilograms over its maximum weight, to say nothing of whatever decrease in performance there might have been due to damage done by the enemy’s rounds. The helicopter’s skids bounced off the water four times as Pless ordered his crew to jettison the empty rocket pods and their personal armor. Lifting into the air, Pless contacted local air control and requested suspension of all artillery missions between their current location and the nearest hospital at Chu Lai so that they could fly low and in a straight line without worrying about accidentally running into an artillery shell or its explosion. Despite the Marines’ efforts, only Allen survived.

Though it appeared to Pless and his crew that they had been alone in the rescue area, there were other U.S. Army aircraft in the area when they arrived. At least one Army UH-1 “slick” (armed only with door guns) was also there, but its crew had been unable to tell the difference between friendly and enemy forces on the ground before Pless began his first low-level run, which came about 30 seconds after the UH-1 crew spotted the activity on the ground. Despite being so lightly armed, this crew added the firepower from their door guns to help defend Pless’s crew, exhausting their own ammunition before Pless left the beach.

An unarmed Army Cessna O-1 Bird Dog light observation plane was also there, trying to direct U.S. Air Force North American F-100 Super Sabre fighter-bombers to provide air support, but that pilot was not trained as a forward air controller (FAC). Air Force captain Donald D. Stevens, who was a trained FAC, was scrambled from a nearby airbase in his Cessna O-2 Skymaster—another light, unarmed observation plane—and arrived after Pless’s helicopter had already left. Stevens took over control of the F-100s and later coordinated an Army Reaction Force into the area to suppress the NLF forces and recover the last body on the beach. To give a sense of what Pless’s crew had been up against, the Army force, though larger and better armed than Pless’s crew and supported by six helicopter gunships, never advanced off the beach due to heavy ground fire from at least 10 enemy automatic weapons positions. Stevens reported that he had “never seen more intense groundfire” during the nine months he had been in Vietnam.[2] After the Army force was extracted, Stevens continued to direct airstrikes against the enemy positions until darkness and heavy thunderstorms forced him to return to base. He estimated at least 50 NLF fighters had been killed by Pless, his crew, and the other aerial strikes before the Army force landed. Pless’s crew would later be credited with 20 confirmed enemy killed in action (KIA) and another 38 probable KIA.[3]

Duty First by A. Michael Leahy. This painting depicts the actions of Pless and his crew in fighting off the enemy while rescuing the second soldier.

National Museum of the Marine Corps.

Pless was awarded the Medal of Honor for this mission, with his crew each receiving Silver Stars for their actions. In addition to his Medal of Honor, Pless was also awarded a Silver Star, a Distinguished Flying Cross, a Bronze Star, and numerous Air Medals along with other awards for his service in Vietnam. He was later promoted to major before dying in a motorcycle accident in Pensacola, Florida, on 20 July 1969.

Pless’s helicopter was repaired and continued in service with Marine Observation Squadron 6 through June 1971 and other Marine Corps squadrons until 1977, when it was put into service with a Navy helicopter training squadron at Pensacola. In 1983, the Navy retired it, and it became part of what was then the Marine Corps Air-Ground Museum in Quantico, Virginia. In 1988, the helicopter was loaned out to the Liberal Air Museum in Liberal, Kansas, where it retained its red and white Helicopter Training Squadron 18 colors. In 1991, the Marine Corps museum system recalled the loan, and the helicopter was sent to a commercial firm to begin the process of restoring it to its 1967 appearance. Work on small details, informed by interviews with Fairfield and Phelps, continued to 2005, when the helicopter was hung in the new National Museum of the Marine Corps building, where it can be seen today.

Endnotes

[1] LtCol Joseph A. Nelson to Secretary of the Navy Paul R. Ignatius, “Medal of Honor Recommendation for 26 August 1967,” enclosure 4 (statement of LCpl John G. Phelps).

[2] LtCol Joseph A. Nelson to Secretary of the Navy Paul R. Ignatius, “Medal of Honor Recommendation for 26 August 1967,” enclosure 9 (statement of Capt Donald D. Stevens, USAF).

[3] In addition to the already cited statements, this narrative was derived from LtCol Joseph A. Nelson to Secretary of the Navy Paul R. Ignatius, “Medal of Honor Recommendation for 26 August 1967,” enclosures 2, 3, 5, 6, and 7 (statements of Capt Rupert E. Fairfield Jr., GySgt Leroy N. Poulson, WO James van Duzee, USA, WO Ronald Redeker, USA, and SSgt Lawrence H. Allen, USA); and Maj Gary L. Telfer, LtCol Lane Rodgers, and V. Keith Fleming Jr., U.S. Marines in Vietnam: Fighting the North Vietnamese, 1967 (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1984), 207–9.