Gleb Trufanov

https://doi.org/10.21140/mcuj.20251601006

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: This article focuses on scientific description and discursive analysis of the key parameters of the Ukrainian media as strategic agents of Ukrainian discursive transit during the Russo-Ukrainian War and the proposition of the new field for cooperation of the European Union (EU) and Ukraine conflict studies in media. This study analyzes changes in EU media policies with Ukrainian democratic media development during wartime. The author focuses on the positive outcomes and future perspectives of the EU-Ukraine media organizations’ cooperation in media security and Russian propaganda countering. The article revises the current EU-Ukraine efforts in countering Russian propaganda and proposes the application of conflict studies in the sphere of journalist’s security. By security in this case, the author understands a set of measures to reduce the lethality of journalists’ work in war zones.

Keywords: Ukraine, Russia, war, conflict, media, propaganda, hybrid warfare, information, European integration

The Russo-Ukrainian War is one of the largest armed conflicts of our time. It is necessary to note the wide inclusion of the media as a means of confrontation between the two actors of the conflict. This conflict is considered a hybrid war. The most recent research in the field of security indicates that hybrid war combines conventional and unconventional methods of warfare to achieve long-term goals. These methods are being used in combination to indicate the weak spots in the enemy’s defensive mechanisms. Hybrid warfare shapes the use of a wide range of tools in the sphere of media and occupies the mental space of a certain nation’s society.1 This type of warfare represents a synergy of approaches aimed at achieving a multidimensional goal in an armed conflict—disruption.2 These combined methods are meant to increase success and minimize possible casualties in a conventional struggle. In the context of the Russo-Ukrainian War, both sides use a pattern of “historical/cultural” identity frames in their information operations.

The main characteristic of a hybrid war in this article is understood to be information operations. Information operations during conflict target the audiences of the opponent with certain selected media content to affect the perception of reality in the opponent’s audience by creating false or biased narratives. The media discourse recipient is an object in these operations. Information operations in the context of conventional war create an opportunity of expansion of impact on the opponent through the transformation of values, perception of its support group, and allies. Transformation refers to a process of cognitive impact on media discourse recipients that has the following features: it is constant, focuses on the long term, requires the wide use of instruments and resources of information distribution, and creates media content. In other words, information operations in media are targeting the basic consensus on a national level to indicate social vulnerabilities. Basic consensus is a core set of unique values and traditions forming the identity of a certain nation for years. The main goal is to highlight the fissures and contradictions existing in a nation and create an agenda to transform them into a conflict of interests.3 Successful information operations, from an adversary's perspective, create division and cause supporters of different opinions and views to act hostile toward each other. All of this results in an erosion of the nation’s morale.

The main strategic tasks of modern Ukrainian independent media within the hybrid war are social mobilization of the population around common problems, the creation of a universal platform for dialogue, and a nation’s storytelling of their problems on the international level. The Russo-Ukrainian War has presented Ukraine with the challenge of mobilizing broad spectrum resources for defense, creating a platform for cross-cultural interaction to find support in the world, and countering Russian propaganda. Media in most of the post-

Soviet countries is still in the process of democratic transition. This means transferring the media sources from the state-corporate body to democratic media sources. The main aspect that only democratic media can achieve as a strategic resource is overcoming the crisis of representation and agenda formation based on feedback from the public. The case of the Kyiv Independent presents the need for the democratic media to make a strategic impact in a hybrid war—discursive transit. The Kyiv Independent is a new type of Ukrainian media outlet. It is published in English and presents an international audience with the stories of Ukraine, its economics, history, and war effort.

This research offers a novel concept of discursive transit as the media practice of influence in information operations. What is a discursive transit? Discursive transit refers to the use of information power in a conflict. First, we should note that propaganda during wartime is very common and is widely used by both Ukraine and Russia. Discursive transit is a part of a propaganda frame. Propaganda works as a source of social mobilization on a national level. It serves as a narrative of the “plan” of the state and the armed forces on how to defeat the enemy, explains who the enemy is, what the military needs you to know, and what to do in a case of an emergency. In this article, discursive transit is presented through the work of the Kyiv Independent and its explanation of cultural/identity materials.

In this research, we define power through the concept of Robert A. Dahl. Power is a special capability of A to force B to do things that B would have never done without the direct impact of A.4 Discursive transit is subject-object interaction in the context of information power. It could be either applied as a tool of information struggle between opponents in conflict, or for seeking international sympathy and support (as in the case of the Kyiv Independent). The concept of information power is described through the following: A possesses a monopoly over its story (propaganda) in terms of its distribution and interpretation on a national level; however, A conflicts with B, and storytelling becomes an instrument in a conflict. A seeks an opportunity to change the perception of the reality of B, test its vulnerabilities, or gain momentum in its information operations expansion, increase international support for its war effort, or maintain an image or reputation. It is not that efficient in terms of information impact on B for A to distribute its discourse on its national level only. A seeks global expansion and recognition of their narrative by overwhelming media resources and discourse to change the perception of B’s audience regarding key aspects of conflict and A’s role in it. By discourse in this article, the author understands a set of vital symbols in the media reflecting the main goals and objectives of a nation in an armed conflict. At the same time, for B this discourse of A may be hard to understand—after all, it is a foreign discourse. The following aspects may interfere with its receipt: language barrier, little knowledge of the problem, need for a detailed explanation for certain symbols, and others. So, A should do extensive research on the society of B, including its divisions and overall beliefs to make a transition/migration for its propagandist discourse from its media sphere and culture to fit into the one of B.

However, existing domestic media are not necessarily designed for this goal. Media sources must be independent to operate freely in foreign countries and must be available online, comply with the needed laws and regulations, and be presented in the language that the majority of the targeted audience can understand (e.g., English). Moreover, the media source has to have a reputation that resembles the values of the targeted audience. That is why there emerged a need for the creation of special media outlets for discursive transit like the Kyiv Independent. This media source is the best strategic match for Ukrainian discursive transit to gain international support and garner sympathy through discourse on the vital Ukrainian identity, historical symbols, and the atrocities connected to the invasion by Russia, including inculcating Russian language and beliefs in the occupied regions of Ukraine. This new independent media is aimed at the internalization of Ukrainian storytelling. For Ukraine, the core topics of its discursive transit are national identity symbols, culture, and independence. However, Russia uses discursive transits too. Since the very beginning of the full-scale war in 2022, the Western states chose the strategy of information isolation of Russia to prevent pandemic misinformation in their media spheres. Russian war discourse is mainly aimed at criticism of the West, legitimation of the war effort, and discreditation of opponents. Russia was constantly trying to break out from this blockade, but increasing amounts of Russian-affiliated media outlets were banned in the United States and the EU. Nevertheless, Russian elites came up with an idea of using Western journalists to deliver and transit their discourses into Western media spheres.

The striking example of this is the Vladimir Putin interview with Tucker Carlson on 6 February 2024. The Kyiv Independent produces and distributes its stories independently without inclusion of mediators between its audience and the media outlet; however, in the case with Russia, an American journalist served as an intermediary structure in this discursive transit. Carlson may be considered a controversial figure in the American media sphere, but the Russian leader did not have many choices or media options to deliver his speech. For Putin, it was essential to be represented by a Western journalist. This interview may have been aimed at the polarized agenda inside American and Western media spheres by emphasizing hatred and imbalanced emotions. Putin focused mainly on criticism of the West and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the legitimization of the war effort.5

Independent media tends to inhabit a strategic role in society as a mediary structure between the public and national leadership that can learn the needs of people. Social activism in media is a major aspect of social mobilization of the nation. Democratic media are extremely effective in countering propaganda by fact-checking and investigating it. Furthermore, media serves to moderate conflict by countering propaganda. This strategic role is described in this article by the example of the EU-Ukrainian antidisinformation effort and the author’s view on media as a part of the conflict-management resource in an armed conflict. Democratic media as a social platform creates an inclusive public space for national initiatives. In this case, the media may work as a fundraising platform to announce the needs of the nation—and the military during the war.

In this research, the author views propaganda countering in the context of hybrid warfare and democratic media development as integral to building an effective model for the regulation of information conflict. The Russo-Ukrainian War tends to be inclusive in terms of the intervention of many parties in collaboration on information security and media. Here, we can list the United States and the EU as the main strategic partners of Ukraine. So, strategic cooperation of the EU, the United States, and Ukraine in building an effective antipropaganda policy is essential.

This process is described as the construction of strong cooperative bonds between collective governmental bodies, media actors, and the public. While these terms differ by their disposition in social life, the author sees them as the most essential parts of building an effective media policy for wartime. The Russo-Ukrainian War and propagandist discourse require democratic media in the EU and Ukraine to accept challenges; however, European integration of Ukraine is an ongoing process that shows the number of potential fields for cooperation. One of those fields is media security. This article is mainly a descriptive work aimed at a theoretical explanation of how European integration of Ukraine provides new instruments for propaganda countering as a strategic cooperative ground.

How did European integration affect the countering of Russian propaganda in the context of the EU-Ukraine strategic collaboration in the media sphere? The object of the study is to analyze changes in the media policies of the EU that are aligned with the process of Ukrainian democratic media development during wartime. The subject of the study is the positive outcomes and future perspectives of the EU-Ukraine media organizations’ strategic cooperation in media security and Russian propaganda countering. Modern researchers in the fields of politics and media studies specifically focus on the role of the media in hybrid operations during the Russo-Ukrainian War. They pay attention to aspects like the Ukrainian military readiness, Russian expansionist culture, and colonialist frames. The relevance and significance of this study are defined through the following aspects. First, there is a gap in contemporary research on the role of the EU integration of Ukraine and their collaboration in Russian propaganda countering.

This article presents the study of the most recent EU legislation initiatives in the context of information security and media regulations. Moreover, this study is the first attempt at scientific description and discursive analysis of the key parameters of the Ukrainian media as agents of Ukrainian discursive transit during the Russo-Ukrainian War. This aspect was studied in the example of the Kyiv Independent. Furthermore, this research offers an innovative field for EU-Ukraine cooperation in the sphere of media-security-conflict studies in media. EU integration aspirations for Ukraine are now secured by the EU as a logical outcome of Ukraine’s effort to become an EU member. However, the Russo-Ukrainian War and the context of Russia’s information operations pose a serious threat to both the EU and Ukraine. Moreover, Russian information operations fighting became an object of collaboration between the EU and Ukraine and led to the EU development in the field of media-regulation legislation. We can conclude that constant analysis of the current efforts and presentation of the methods and tools should be the basis of any antipropaganda measure. Russian pro-regime media is a dynamic structure that adopts new methods and intensifies its operations.

The article starts with the methodology section describing the methods and approaches used for this study. The methodology section elaborates on the approaches, frames, and their meaning in the context of the study. Furthermore, the research continues with the revision and description of the current research results in the sphere of media studies and political communication in the context of hybrid warfare and information operations. The article continues with an explanation and description of the development of EU legislation on media regulations.

The author especially emphasizes the innovative adoption of the European Board for Media Services as an intermediary body. The study outlines the positive effects of the representation of the national identity symbols as a key factor in building a problem-oriented media strategy, as in the case of the Kyiv Independent. The article continues with an explanation of the new generation of Ukrainian media, the aspects of success needed to make discursive transit a successful element of media reality for constructing a positive national image, and how this in turn creates a cultural dialogue space and helps obtain international support. This article introduces a new way of raising security in media for both saving journalists’ lives and making media a safe space. This particular article presents a new concept of EU-Ukraine cooperation and conflict studies in media. The article continues with general provisions for the inclusion of conflict studies in media, its relevance, and its positive influence on security in media. The conclusion highlights the findings and outlines the potential for further research.

The Research Objectives

Research objectives of this article include explanations of the most recent EU efforts in the security of journalism and information security practice as well as the revision of the current EU-Ukraine efforts in countering Russian propaganda. The formulation for the application of conflict studies in the sphere of journalist security is a strategic source for collaboration expansion in the frame of EU-Ukraine efforts regarding information security.

The author performs a discourse analysis of discursive transits in the wartime case of the Kyiv Independent to identify key features of the Ukrainian independent media strategic potential in the context of collaboration with the EU in countering Russian information operations.

Review of the Literature on the Current State of Information Warfare

Information warfare between the EU and Ukraine against Russia has never been more relevant than it is now. There is a limited body of literature that is dedicated to the study of aspects of propaganda countering and problems and controversies of the Russo-Ukrainian War discourse in media. Ukrainian media had been through many transformations since 1991, which was the year the Soviet Union collapsed.6 However, media and political researchers from different Western countries have done significant research to define Russian propaganda and ways to counter it. Maxime Audinet, Eloïse Fardeau Le Meitour, and Alicia Piveteau studied strategies for how an agenda is formed.7 Jakov Devčić studied aspects of changes in political discourses in connection to the national proximity of Russia and Serbia.8

National proximity is one of the key aspects of Russian propaganda’s success in nations of the post-Communist states. Russia performs its information operations in the Balkan region actively. Those operations are focused on the concept of “Slavic-brother” states. Russian media is making discursive transits in the media spheres of those states, including efforts to create proxy media. It is a vital activity for Russia to capitalize on post-Communist and Slavic sentiments in the Balkan region to reflect wide international support for the war effort in Ukraine. Social media plays a crucial role in information distribution and building the trust between media outlets and audiences.9 It has many features beneficial for both Ukraine and Russia in terms of discursive transit. Online media platforms have less strict regulations than those created for registered media providers, plus services like YouTube are accessible worldwide and have a vital element—the comment section—which serves to create a long life cycle of media participation and discourse recipients. Interpretation of media material ensures the story is more effective than just a piece of broadcast shown a few times on television. This longevity benefits Russian propaganda consisting of pro-regime individual influencers responsible for an intensive and constant propaganda flow.10 Many researchers highlighted this feature of the new generation of online resources and their special role in discourse distribution.11

David Gregosz and Daniel Sagradov highlighted the essence of Russian imperialistic ambitions in the formulation of media discourses in Poland and the Baltic states. Researchers argued that online media platforms distributing pro-Russian narratives have been proving themselves as integral aspects of social tension between Poles and Ukrainian refugees residing in Poland.12 Researchers from the Hague Centre for Strategic Studies came to a specific conclusion about Russian propaganda’s effects on norm and habit formation. Constant repetition of narratives may lead to norm formation.13 Modern social media became a place that serves as a fake distribution platform. Social media (Instagram, YouTube, etc.) allows content creators to give their opinions on political and social events. Moreover, wars like the Russo-Ukrainian War give an incredible opportunity for many content creators to focus on conflict analytics especially. Videos on drones and war atrocities have been used by many media recipients since the very beginning of the war.14 However, in the case of social media independence, the lack of control and accountability along with the lack of a proper fact-checking will result in fakes and disinformation. Many researchers highlighted this exact problem since the beginning of the war, especially those who focused on the most novel ways of warfare and disinformation around them as a result of the ambiguity of these methods of engagement, which can cause fear, damage, and are widely available.15

Moreover, if that narrative repetition is unchallenged, it creates a new set of norms. In the case of Russian propaganda, those narratives are aimed at the legitimation and normalization of the war effort and the ideological frames behind it. Implication of legitimation of war frames through foreign media resources is the main task for Russian wartime pro-state media. Many researchers conclude that the Russo-Ukrainian War has been seriously affecting the European security architecture since 2014 in terms of territorial integrity violations. European states have been concerned about the probability of a full-scale war in Europe between Russia and NATO.16

Finnish researcher Tuukka Elonheimo reported that highly digitalized societies are predisposed to become victims of propaganda due to the high level of access to different sources of information.17 Moreover, Canadian researchers have made a complex, comprehensive attempt to find the reasons for the success of Russian propaganda for internal social mobilization during the war in Ukraine. Social mobilization is an internal support resource of the state. Inner legitimation of Putin’s regime is one of the main aspects of Russian pro-regime media actors in social networks. Simon Hogue states that cyber operations in social networks like a TikTok social network are an essential action in the context of digital participation.18 The main task here is getting approval of the regime’s actions from the public through the constant implication of polar images of the “good” and “special” role and destiny of Russia in saving Ukraine and the world from many threats. Pierre Jolicoeur and Anthony Seaboyer pointed to artificial intelligence technologies developed in Russia. They believe that artificial intelligence is a significant threat in the context of a hybrid warfare model.19

Ukrainian media researcher Mykola Polovyi concluded that prewar Russian propaganda was built on symbols of sympathy in the context of history. Russian propaganda applied “positive Soviet legacy,” “unity,” and “nostalgic” models that targeted the Russian-speaking Ukrainian community’s sentiment.20 Polovyi has identified language as a key cultural mechanism of norm or pattern accommodation. This specific role of the Russian language has been exploited by Russian propaganda ever since. Language serves as a link between Ukrainian media recipients and the object of Russian propaganda. The media recipient is always an object in the case of propaganda. The most recent research indicates that memes and popular culture are meant to play a crucial role in uniting the nation during the war. Humorous materials serve to emphasize problems and maintain morale.21

Methodology and Framework of the Study

For this research, the author applied various methods and approaches. The first method used was critical discourse analysis to analyze social and political aspects represented by text or in speech. This method is used by many researchers and widely described in many works.22 Teun A. van Dijk gave critical discourse analysis the following definition: critical discourse analysis is a type of discourse analysis that first and foremost examines how the abuse of power, domination, and inequality is established, reproduced, and countered in text and conversation in political and social contexts.23 This is a multipurpose scientific approach that allows us to interpret and scientifically describe social and political processes in the frames of many disciplines.24

However, in this study, we focus on cultural and political dimensions when analyzing discursive transit in the context of the Kyiv Independent. Ukrainian media discourse has a strong connection to the representation of wartime problems; however, war as a conflict is a multidimensional process. In this research, the author examined text constructions as elements of culture and the history of relations or conflicts between nations.25 Those aspects were studied through symbolic representation in the Ukrainian wartime discourse. The platform Ukrainian media discourse is constructed on is the idea of a distinct Ukrainian identity and that Russia is the aggressor in this conflict and Ukraine is simply fighting for its independence as a sovereign nation. Critical discourse analysis allowed the author to examine those aspects in the example of the section “Explaining Ukraine” on Kyiv Independent’s website. Symbols represented there are not isolated units; they are meant to construct the complex image of Ukraine for a Western audience within social and political contexts to counter the Russian propagandist model of idiosyncratic history. This article analyzes symbols that are subject to discursive transit like vyshyvanka, cossacks, etc., and highlighted their intratextuality in the representation of Ukrainian identity. Moreover, it should be noted that the “Explaining Ukraine” section represents Ukrainian symbols linked to the historical perspective of Russian aggression and its political and social repercussions.

Discourse analysis was essential to make the following conclusions that one of the main aims of Ukrainian discursive transit is to fight the cultural appropriation frame that is widely represented in the Russian wartime discourse of hostility. Moreover, discourse analysis of Ukrainian discursive transits is aimed at the deconstruction of the idiosyncratic view of Ukrainian identity and culture of Russian propagandist discursive transits. Discourse may serve to increase social mobilization.26 Opinion, comment, and donation sections on the Kyiv Independent all discuss Ukraine and the effects of the war on Ukrainian society as well as news about the war effort. This enables Ukrainian discourse to be interpreted and makes the storytelling continue. In terms of formulation and theorization of the role of conflict studies in media as a collaborative field for the EU and Ukraine, we used the conflict model of Ralph Darendorph.27 In this conflict research, we mean any relation of incompatibility in terms of interests and positions. This incompatibility is described on the level of states and groups of interests like media outlets. A key aspect of any conflict is struggle as a process of achieving goals. The frame of a Ukrainian discursive transit as a propaganda-countering measure reflects this idea. Supervision of the third party is important for conflict regulation according to Darendorph. Conflict studies in media are meant to serve as an intermediary in solving problems inside and outside teams of media professionals to maintain security. Moreover, the role of the European Media Board was emphasized with a third-party role in the regulation of conflict as the process. Among other methods, we can list close reading of the EU legislation materials. Key aspects of information conflict as a part of hybrid warfare were developed in connection to the hybrid warfare theory of Martin C. Libicki.28 Moreover, Committee to Protect Journalists’ (CPJ) reports data was visualized via graph to visualize how dangerous war journalism is in war zones from 2022 and 2024 and addresses the danger and lack of proper security for media workers in wartime.

Results

Context

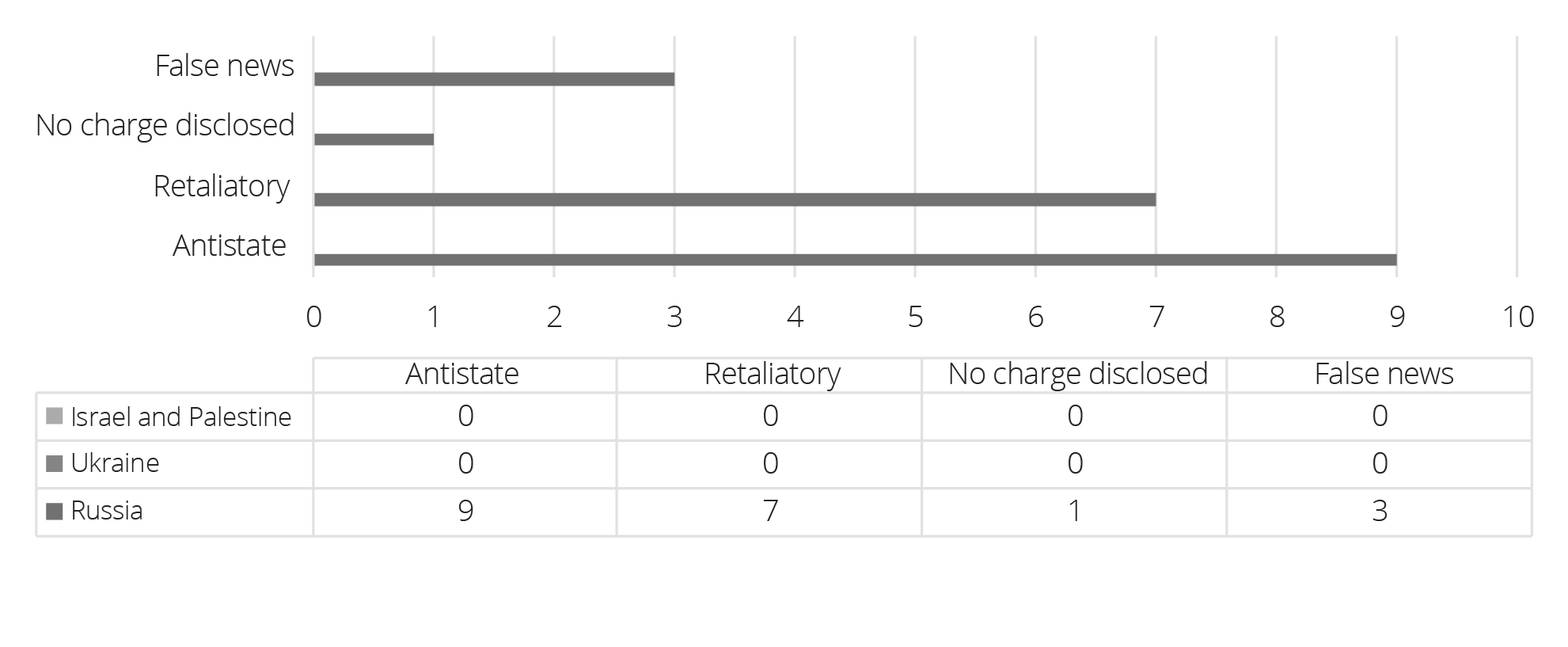

War zone journalism tends to be a risky activity. However, there are still no complex tools for making it safer based on the conflict studies approach. Since 2022 the freedom of media and independence of journalism are of extreme importance due to the need to report the major armed conflicts emerging in different regions of the world. Russia has applied strict laws against independent media. These laws had repressive repercussions on independent journalists in Russia like the apprehension and detainment of the Radio Liberty journalist Alsu Kurmasheva who was detained in Kazan, Russia, on 18 October 2023. Other cases include the detention of Evan Gershkovich on March 2023. Other cases of detention happened to different journalists who were covering the aspects of Alexei Navalny’s death. Media in these difficult times are essential in terms of investigating and presenting different perspectives from diverse groups. The deep political crises in Russia showed that independent, democratic journalism is in the most danger in times of conflicts. Protection of media means securitization and support of its independence and ability to function. Major conflicts like the war in Ukraine and the conflict between Israel and Palestine in the Gaza Strip region proved that conflicts have a constant trend to raise uncertainties about the treatment of journalists in the combat zones. Journalists may die from structural violence from the side of states and their institutions. Those cases may include intentional harm to the journalist’s physical health, life, and mental health caused by authorities. Furthermore, there is possible indirect harm like negligence of laws, burdensome bureaucracies, danger, and lack of proper work in a conflict zone from the military, law enforcement, and other bodies of the state. We can conclude that any governmental policy in media regulation normally should include the following aspects: freedom of speech and pluralism promotion and guarding, creation of a safe and legal work environment for journalists, and maintenance of policies against hate speech.

Since 2022, in military operations by Israel in Gaza against Hamas and the war in Ukraine, the journalists covering these conflicts are subject to many risks in war zones. Violence and casualties occur frequently in those conflicts. Civilians suffer from combat actions.

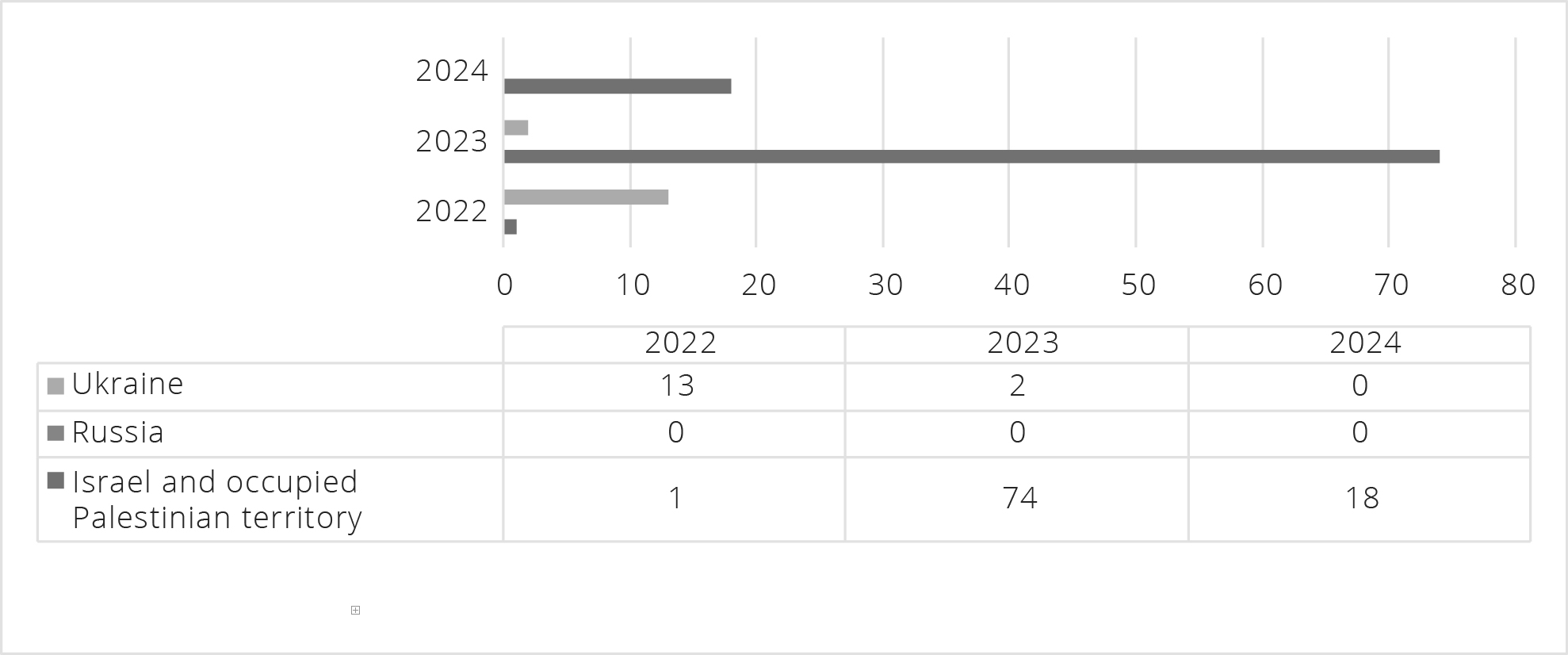

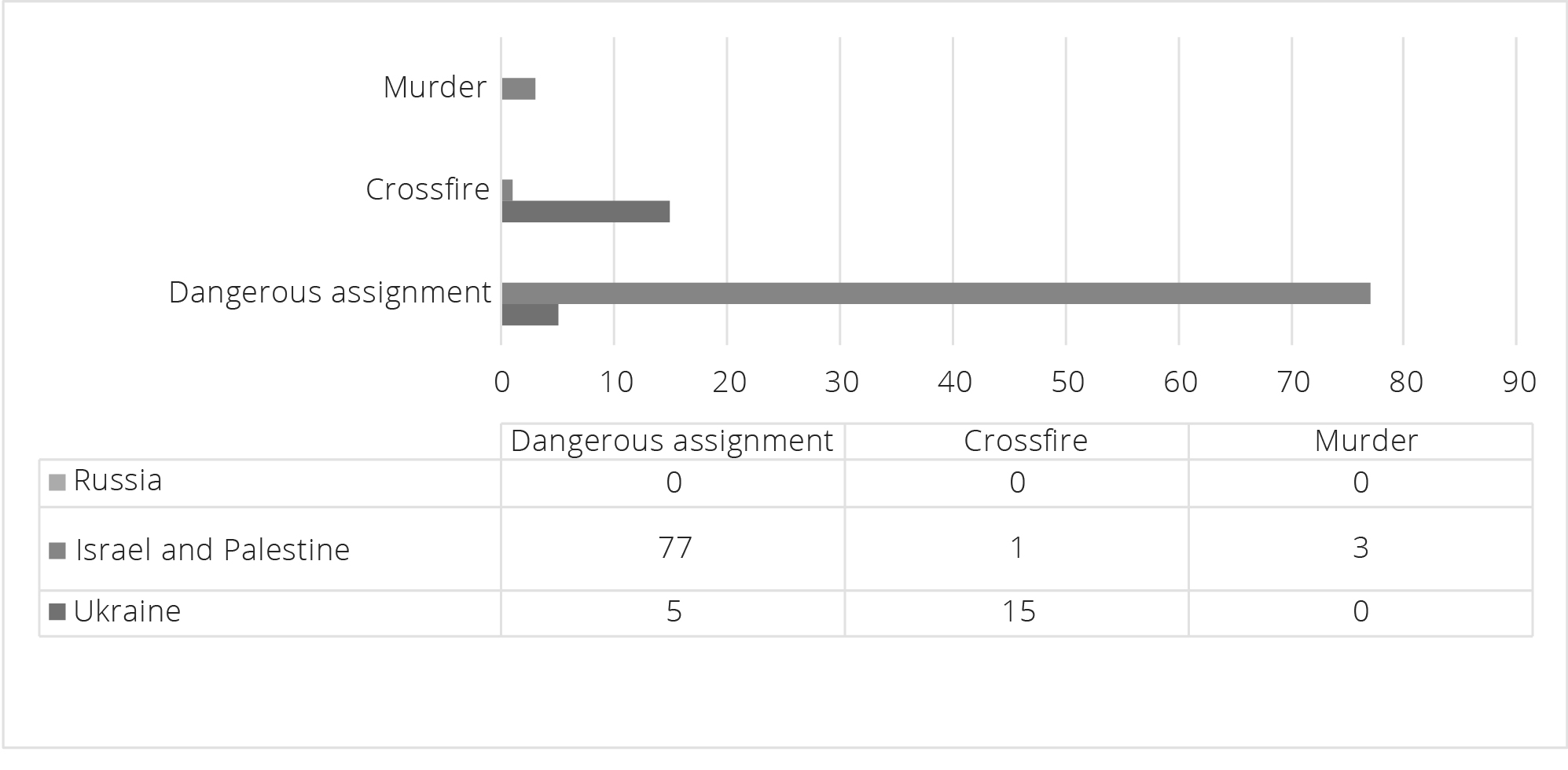

There are analytical reports by the CPJ on accidents that happened to journalists who worked to cover those conflicts. Below are three graphs that represent the analysis of harm made to journalists while performing their duties. These graphs represent data to show that journalists are exposed to pressure from many groups, including governments. These graphs give three main markers of harm. There are three major markers of how to measure the level of risks of working in a war zone or covering conflicts while being a journalist in a country with strong repressive laws and censorship.

These markers consist of three possible negative impacts on journalists and media workers. The first marker is the death (murder) of the journalist or media worker. The second one is about the circumstances of the death of the journalist, such as if it happened during a crossfire or whether it was an intentional murder committed by some group or governmental body or institution. The third marker is defined by imprisonment due to the journalist’s position on covered events, which includes the exact reason for that imprisonment. Reasons are different, however, in general, we can conclude that those reasons are in the field of structural violence of the state as a tool for forceful consolidation of media around the allowed field of coverage. For instance, in Russia, there is a law on reporting “fake news” (accepted on 4 March 2022) about the activities of the Russian armed forces. This law defined both the amount of the penalty of up to 700,000 rubles (approximately 7,000 euros) in the case of a regular violation and 300,0000 rubles (approximately 30,000 euros) in case of an aggravated violation. The incarceration term could be up to three years. The choice between penalty and incarceration is at the discretion of the court.29 This law was used against independent journalists many times. Coverage of armed conflict events is risky for journalists—they may get killed in a shooting or airstrike or get imprisoned due to noncompliance with repressive laws.

Risks connected to working as a journalist in Ukraine are very much connected to the dangers of entering and performing duties in the war zone. The most casualties were sustained during risky assignments and crossfires. Those results tell us that Ukraine does not impose much of a political threat to free journalism and does not apply any rigorous laws against journalists. The greatest danger comes from the presence of a large number of combat-connected aspects (live fire, military maneuvers). Furthermore, risks connected to working as a journalist in Russia are very much connected to the dangers connected to the high probability of becoming a victim of the structural violence that is on the rise constantly. Russian authorities try their best to facilitate the information vacuum around their war effort in Ukraine and maintain their own approved narratives.

The conflict between Israel and the Gaza Strip has had more casualties than the Russo-Ukrainian War. Among dangerous assignment deaths, there have been murders. Murder means it was intentional, planned, organized, and backed by some group of interest. The reasons for murdering a journalist can include wanting the journalist to stop working on their assignment to ensure the activity remains hidden. Journalists often perform investigations on certain problems of public interest. These topics compared reports of abuse of power, violations of martial law, tortures, etc. When the interests of major groups of interest are reported on, it jeopardizes their activities, which means they have a motive to commit a murder to continue to cover up their activities.

Figure 1. Journalists and media workers killed in countries that participated in armed conflicts, 2022–24

Source: Committee to Protect Journalists, 2024, adapted by MCUP.

Figure 2. Journalists and media workers imprisoned in countries that participated in armed conflicts, 2022–23

Source: Committee to Protect Journalists, 2024, adapted by MCUP.

Figure 3. Deaths of journalists, by type, 2022–24

Source: Committee to Protect Journalists, 2024, adapted by MCUP.

The European Union Legislation and Free Journalism Development

European integration is a long-term strategy of Ukraine. Integration into a union as a new member is a very complicated process. Ukraine has to embrace and adapt to European ideals of how media works as an independent body. What is a European media strategy? Laws have a national context and differ from country to country. EU regulations in media are the concept of how media should work as an independent public servant. EU media regulations or standards are accepted by members of the EU and are meant to protect journalists as public servants from any violations conducted by nation-states and their governments. The EU in this case is an intermediary or arbiter in any type of clash of interests between media and state apparatus. Conflicts of interests are possible even in free and democratic states in the EU. For instance, in the case of Poland, the media is constantly struggling with political and financial dependencies. For years, the ruling Polish party, the Law and Justice Party (PiS), used Public Service Media (PSM) as a propaganda tool.30 This was possible because of the control over media that the Law and Justice Party had. Another striking example of this type of conflict between state apparatus and media is Slovakia. There are cases of state sabotage on the investigation of murders of journalists (e.g., Ján Kuciak and his fiancée Martina Kušnírová).31 Moreover, control of independent media is very high, which makes it hard for media to stay independent.

The EU constantly develops and maintains its policy regarding the freedom of journalism and journalistic protection. The EU claims that it is doing everything possible to maintain the highest standards of pluralistic and deliberative democracy trends in modern journalism-state relationships as a strategic democratization of media. The EU has many regulations on how freedom of journalism should be implemented. Moreover, EU policy in journalism is a provisional thing. Some scientists in the field of media research believe that contemporary European media serves as an instrument of the representation of the core ideas dedicated to the storytelling of the social groups perceived as fragmented identities without the internal drive to societal integration.32 Some modern researchers believe that the EU has to expand its media strategies to other countries to shape the media sphere in those countries and make those societies more democratic.33 According to Nevena Ršumović, the speed of transition of democratic values to some post-Communist regions, especially the Balkan states, is among the main reasons that governments applied brakes on the development of free journalism.34 The problem of the involuntary political values transition is a major issue for many European countries with a Communist past (such as the Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia, and the Balkan states). The repression of journalism has been inherited from both inside social spheres and outer foreign political circles and elites.35 Some researchers highlighted the essence of the contradictions inside media doctrine in modern Europe.36 These and other complex issues should be highlighted for ensuring the future of media regulation in the EU.

EU policies regarding protection of the independent media sources seek to maintain a special status for journalists to protect them from danger. Journalists are supported by the following bodies to protect freedom of speech and journalism. On 20 March 2024, the European Parliament accepted the Regulation of the European Parliament and of the European Council, establishing a common framework for media services in the internal market and amending Directive 2010/13/EU (European Media Freedom Act).37 This document serves to prevent multiple threats: the politicization of the media sphere, dangers connected to the work of journalists, and the interference of political actors in the media sphere. The European Media Freedom Act (EMFA) enhances the protection of editorial independence. It ensures the independent functioning of public service media. This act is aimed at ensuring the transparency of media ownership. Additionally, this new piece of legislation protects pluralism to provide differing perspectives and opinions for analysis.

On 28 April 2022, the European Council has accepted a law that should protect journalists against strategic lawsuits against public participation (SLAPP) (Interinstitutional File: 2022/0117[COD]) as public backlash or burdens to be applied by various stakeholders, public servants, etc.38 A SLAPP is a lawsuit that oftentimes causes major damage to journalists due to the costs associated with legally defending themselves against the company or person who initiated the lawsuit. SLAPP lawsuits pursue journalists to make them silent and preoccupied with the financial and emotional burden that the lawsuit applies to them. In other words, SLAPP serves as an instrument to prevent public participation and to silence criticism outside the accepted narrative.

This law is meant to protect journalists’ independence by providing financial remedies and coverage opportunities for victims of these types of lawsuits that target journalism as well as a free press. It allows courts to dismiss unfair and biased lawsuits designed to suppress journalists. It is granting protection from third parties (country judgment).

War in Ukraine brought a new agenda to the field of European integration of Ukraine. The integration of Ukraine into the EU is the best solution to enable long-term cooperation in the field of media regulation. The media community is a self-reflective and self-regulated body in any free country. Democratic transition of media in Ukraine is an ongoing process, however, it shows progress. Media is still vulnerable to the pressure of the major political actors, stakeholders, and government. However, it may empower its beneficiaries from different spheres. Media has significant power in discourse formation, adaptation, distribution, and interpretation. Media tends to be independent, but in most cases it is impossible. Media, by its nature, produces conflict: contradicting interests and differing positions are subject to conflict there. Moreover, media is a very dynamic and fast-changing field, and this fact aggravates existing tensions there. The variety of interests to consider and analyze in media is overwhelming. There are also possible conflicts not in the media sphere, but conflicts connected to gaining access to a certain element of the media sphere in terms of control and use. Media has a spectrum of uses: a tool of political communication, a reflective mirror of reality, and a creator of artificial reality (fake news, deep fakes). Media is not a regular interlocutor, but it is a tool of information distribution. Media is not a homogeneous, static body. It always has diversity in many ways, from its many forms of distribution to the ideas it promotes.

Ukrainian Independent Media Development in Wartime: The Case of the Kyiv Independent

Since the beginning of full-scale war in Ukraine in 2022, there has been a constant trend of an increase in the use of electronic devices with an internet connection. According to United Nations (UN) reports, the number of Ukrainian citizens using the internet daily is constantly growing.39 A UN report indicates the growth from 72 percent to 80 percent in the last year.40 According to the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS), 79.9 percent of the Ukrainian population use the internet for more than three hours a day daily.41 The global index of digitalization is on the rise too. According to the report of Datareportal, the constant yearly worldwide increase of internet users is 1.9 percent. Moreover, the average time spent online equals 6 hours and 37 minutes.42

The benefits of digitization resulted in the development of small, independent media focused on specific topics and predisposed to work on certain narratives or information operations (such as the Kyiv Independent). The Kyiv Independent is a phenomenon of wartime, made by young and active people in Ukraine seeking support from young people from different countries. This type of media is specifically important in the context of countering Russian propaganda and gaining international sympathy and support through discursive transit as a media strategy. Those outlets serve not only to cover the events of war but to create a new information space. In other words, these media work as an information provider and for countering misinformation by explaining the events reported by the opponent. The new information space creates discourse transition opportunities, including the Ukrainian agenda in global and European media discourses, and promotes the Ukrainian identity as a part of Europe. As for other functions, we can list cultural promotion and diplomacy, charity, and fundraising. Discourse in those media outlets is a mixture of state, European, global, and Ukrainian viewpoints and ideals.

The war in Ukraine is comprehensively covered by a variety of media technologies. Digital modern resources in Ukraine are meant for the new generation of active decision-makers, who make digital media the main source of information. The dialogical nature of the new media in Ukraine and the world in general means gaining support from and including the audience in the creation of the media product. Ukrainian media serves as a symbolic beacon for seeking multilateral support from a wide variety of institutions around the world. We can list states, nongovernmental organizations, charities, and communities with different core ideas. Internalization of the war in Ukraine is beneficial to Ukraine in terms of seeking support, finance, and donations. Ukrainian media in wartime plays the role of a symbolic transit intermediary. The example of the Kyiv Independent gives us a clear understanding of how discursive transit is being implemented in the new generation of Ukrainian media. The Kyiv Independent as a discursive transit agent offers a unique experience for Ukrainian discourse recipients from all around the world. The new generation of media will shape the future of the media in general.

There are several key features of the effectiveness of media in Ukraine, for example, the Kyiv Independent. The first feature is accessibility—English is used as the main language for all the publications. The internet is the primary distribution model, which makes media content internationally available. Second, the Kyiv Independent develops an interactive platform that allows users to participate in the future of the media and allows users to shape materials and content. The Kyiv Independent allows them to create unique experiences (such as getting newsletters, cross-platform sharing, following options, and comments sections). The recipient feels like they are a participant and an integral part of the narrative formation. Third, donations and charity are aimed at enhancing the feeling of inclusion in the most pivotal events of modern Ukrainian history and allow recipients to join the battle as a part of media participation. Fourth, different sections like business allow for a look at different aspects of life in Ukraine and Eastern Europe. Fifth, the Kyiv Independent is a problem-oriented media source; the first headlines and titles are dedicated to war. The majority of its sections tell stories about investigations and war crimes. The current war in Ukraine and the Russian invasion are key topics that the newspaper covers, and other stories serve as background to empower people with information in the war effort.

All these sections are aligned with the core idea of this media outlet, which is the promotion of the Ukrainian perspective on topics regarding the European future, Russian aggression, Western support, and political landscapes of the present times. The opinion section creates space for discussion of experts on important topics and the inclusion of media recipients in analysis on the relevant problems of Ukraine. Comments sections serve for the unionization of the audience and an even wider inclusion of discourse recipients. Disclaimers are needed to prevent any harm to the source from unpopular speakers or opinions. The Kyiv Independent explores national symbolism; it allows you to get an experience of learning the main Ukrainian symbols and the history of Ukraine.

All famous symbols are given connotations and explained to build a positive image of Ukraine. Moreover, an explanation of traditional Ukrainian festivals like the Ivan Kupala midsummer festival serves as an exploration into Ukrainian identity and culture as opposed to Russian culture, emphasizing the uniqueness of Ukrainian identity. Parts of the Kyiv Independent website lets the readers know the timeline of the Russo-Ukrainian War better, including giving more context to past Russo-Ukrainian relations. There is an article titled “10 Years of War: A Timeline of Russia’s Decade-long Aggression against Ukraine,” which educates people on the history of Ukraine-Russia relations.43

The history of Russian aggression explains the complexities of the conflict and the reasons Ukraine has to fight against Russian aggression. Furthermore, the connotations given promote cultural diplomacy and make clear distinctions between Russian and Ukrainian historical ways and identities. It may look like the process of the deconstruction of ethnic bilingual connections, however, the aspect of identities has been a serious question ever since.44 Educating readers on Ukrainian identity and culture is the soft power of discursive transit the Kyiv Independent uses to gain international sympathy and solidarity. Also, it is one more asset in information operations to provide a Ukrainian perspective in terms of discursive transit and Russian propaganda countering. This is the deconstruction of the historical myth of the lack of differences between Ukrainians and Russians in terms of culture, origins of statehood, and the misperception that the main language is Russian. Aggressive cultural appropriation is one of the main features of the Russian wartime discourse of hostility. The Kyiv Independent explains to its Western audience the origins of Ukrainian identity in an accessible form. This Ukrainian democratic media works to explain the need for Ukrainian sovereignty. This in turn creates a strong bond with the ideals of the many Western media outlets and aligns with international support for Ukrainian defense. Moreover, this ideological platform links the EU and Ukraine regarding media collaboration and propaganda countering.

Countering Russian Propaganda

The most prospective field to be worked on for both the EU and Ukraine now is the antipropaganda legislation. Wartime dictated the adoption of media strategies to combat the hybrid and asymmetrical warfare, which combines the many sources of power available to a nation-state. The Western influence that grants the development of the forms of legislation and protection is the best basis for integration and building intergovernmental and cross-professional community connections between the EU and Ukraine. Ukraine is the testing ground for high-end antidisinformation tools. Information warfare is a complex hybrid problem aimed at perception changing and producing sympathy via media coverage. The correction of the perception of the electorally active population leads to unstable relations between the state and the people. Uncertainty during wartime is one of the problems that can also affect informed decision-making, which is why the information warfare problem is so relevant for modern democracies to fight.

Western—especially EU—media influence on Ukraine in the context of integration can be described as deep collaboration between the EU and Ukraine on solving one problem: creating effective tools for the management of information conflict. In their latest work, the researchers from CSIS highlighted the inevitability of counting information warfare as one of the most important threats for European democratic states. The main conclusion of the research was that cooperation should transform into collective efforts, which then could be aimed at creating efficient tools for countering disinformation. Cooperation is effective due to the combination of resources and duties distribution.45

The EU-Ukrainian efforts resulted in the Hybrid CoE Research Report 2024.46 The main efforts made by joint EU and Ukrainian researchers are being aimed at the deep analysis of how pro-Kremlin propaganda works and which tool is the most efficient in terms of preventing the spread of dangerous misinformation. This report is one of the key EU-Ukraine integration products in the sphere of information of a conflict-management nature.

The most effective conclusions made in this report regarding how to deter propaganda activity include a variety of strategies. These include:

1. Consistent monitoring and analyzing of information. Distorted and misinformation should be immediately unveiled and given a proper connotation. Efforts to detect and deter pieces of propaganda or fakes should be implemented promptly.

2. Financial support of antipropaganda and fact-checking units is key. Information warfare units are the keystone of the modern information warfare.

3. Efforts should be collective. Overlap is not ineffective. Society and its will to deter propaganda is key for a state at war to fight it. Reciprocity and integrity are the main keys to success in information conflict.

4. Information conflict is inevitable, so preparation is essential; however, preparation is not a recipe for 100 percent success.

5. Crisis management: you cannot be prepared for everything, so adaptation and overcoming the odds is key.

6. Memes and humor are some of the viral forms of information with a major punitive outcome.

7. Symbolic attacks as punishment are inevitable.

8. Messengers are integral parts of the deliberative antipropaganda campaign going on nationwide.

9. The information war is never over. It consists of clashes and pauses.

10. The creation of the alternative discourse to the Russian propagandist is an integral part of hybrid warfare. The crisis of representation and information isolation of the internal media sphere are among the most widely used tools in modern Russia.

Dialogical models of media participation are now being adopted in the EU. Media transparency and media inclusion in political discourse on effective decision-making in media regulation are on the rise. Besides, the newly adopted initiative brings clarity into the moment of media market concentration. The main aspect here is crisis management. Responsible legislative bodies are exercising control of media market concentrations, not repression of those media bodies. The author deduces that this aspect is based on complex impact evaluation. According to the document, structured dialogue means constant experience exchange between actors of the media sphere and legislative bodies on diversification and independency monitoring of media.47 Furthermore, the board will work for coordination of measures aimed at control of media products coming to the EU from the media outlets from countries outside the European Union. This measure will allow the board to become an intermediary in the context of countering any information threats coming outside of the EU and its partners. This initiative plays a major role in the face of countering Russian propaganda. We can conclude that this new legislative initiative may become a first step in the EU for the empowerment of legal barriers for hybrid warfare. We can say that such a law may set a new period of partnership in the EU, and Ukraine is an integral part of this collective effort.

Media Security and Cooperation

In light of the Swiss international summit on peace for Ukraine and EU-Ukraine joint efforts on counterpropaganda operations, the author believes that there is one more opportunity for effective cooperation in peacebuilding. Regulation (EU) 2024/1083 sets a new era in collaborative efforts to create safe and independent media space and conflict management has a great chance to become an integral part of it.48 The most recent EU legislation has opened a new era in giving the media in the EU more freedom and protection from being abused by various stakeholders. Moreover, this law offers the creation of the special European Board for Media Services. The innovation of this board is its application to crisis management in the media sphere. The crisis is a special moment in the life of the system when it cannot normally function due to unresolved controversy accumulation. The media sphere and its regulation are very dynamic systems, and they need to be effectively managed. The board is an entity for consultation and expertise for media-related problems. The collegial nature of this body and its link to the EU Commission is meant to provide distinct, transparent decision-making without abuse of power. The collegiality of decision-making should ensure that individual commissioners do not abuse their power.

Conflict studies in media have a strong trend to benefit the security of journalism in many ways. Moreover, conflict studies in media allow the wide inclusion of experts from different fields of knowledge in the context of an effort to make independent journalism safer. Independent media in wartime met many challenges connected to a lack of effective instruments for resolving problems. There are some general provisions on how conflict studies can serve the media community in terms of increasing security; for example, the promotion and development of a dialogic model of interaction in the media sphere among journalists, statesmen, media personnel, and nongovernmental organizations. This promotion has to be based on the principles of equal rights in the process of effective interaction of subjects.

The first aspect of conflict studies in media is to develop the formation and promotion of a culture of tolerant behavior in the media sphere. Tolerance is a key to minimizing time spent on different altercations and arguments. Those cases do not fall under the definition of conflict; however, they mark a crisis in relations between people. Moreover, that crisis may grow into interpersonal or intergroup conflict. Conflict regulation requires resources and especially time to be done. Tolerance serves as a form of conflict prevention.

Second, the development and conduct of pieces of training and seminars for media staff aimed at the formation of a scientific understanding of the conflict, its nature, and social significance for the progress of society, as well as training aimed at the formation of a culture of constructive interaction between media personnel is needed.

Third, a study of the current legislation in the field of media and other related areas and identification of gaps in the legislation, including making proposals for its improvement. This requires the establishment of constructive dialogue with legislators and media workers, stakeholders, and the promotion of mediation and negotiation models as an alternative method of conflict regulation.

Moreover, it is important to provide constructive feedback and continuous monitoring of elations in professional media collectives and teams by the conflict studies specialists in media assigned for this role in media outlets. Hold sessions of open discussion of problems regarding conflict cases within media staff. The professional activity of journalists and media workers is extremely stressful, especially for those journalists working on war-connected topics. Agora-type meetings should become an integral part of team events. Those sessions highlight the fact that the team should resolve its problems collectively. Even interpersonal crises or conflict has a significant impact on a whole team and its ability to perform its duties. Conflict is a major stress: it may result in mental problems like constant anxiety and depression. Cooperative behavior in interaction and its promotion is key. An open discussion will make it impossible to conceal conflict in the team. Topics for group discussion should consist of problem-oriented elements. Here are sample questions for such a discussion meeting: Who was harmed in harmful events? What consequences did this have? Who and how can their participants correct these consequences? How do we strengthen positive trends, outcomes, and agreements?

The last aspect here is the participation of conflict studies in media in the security enhancement of journalism. This requires conflict monitoring, analysis, and research of the dangerous war zones where journalists are predisposed to intimidation, lawsuits, harm, or any kind of injuries including death.

Research should be conducted in the fields of war zone studies, conflict regulation in media, repression of journalism in autocratic states, and conflict and journalism perception in autocratic states. Conflict researchers must be involved with media management, constant collaborative efforts with nongovernmental organizations (like CPJ), and media management in terms of raising awareness of the dangers of journalism in war zones and autocratic, repressive states. Finally, collaboration with military and security specialists is important to formulate strategies for making journalism safer in war zones is necessary.

One more duty is the creation of field manuals of conflict situations for every possible zone of armed conflict media coverage. Details about main opponents in armed conflict, appearance, behavior in different situations, authorities they are controlled by, territory they are on, ethical and historical features, and perception of independent journalism should all be covered. Multidisciplinary studies of conflict are essential in terms of the formulation of the analysis of a certain region and the conflicts and other issues present in the region. Armed conflicts should be researched not as static elements of reality, but as complex, dynamic political things. Their dynamic structure is described through escalation, intensification, and growth due to the inclusion of new participants. All those factors should be taken into consideration.

Conclusion

Integrity remains the key aspect of the strategic role of the media. The EU media legislation adapts to the reality of the Russo-Ukrainian War gradually. In August 2025, there are planned new additions to the current European Media Freedom Act. The EU consistently focuses on antimonopoly, transparency, and safety in journalism where pressure on freedom of speech is under strict control. Moreover, the European Media Freedom Act aims to build an effective cooperative platform that includes media regulators to protect the European media space from outside threats like propaganda. Its experience in countering Russian propaganda is of major interest to the EU. The media sphere is a dynamic structure that is predisposed to dramatic changes during wartime. The war in Ukraine created a scenario with ineffective instruments for both saving the lives of journalists and for protecting the existence of free journalism. Imprisonment, dangerous assignments, and murders are all threats to journalists. Propaganda as a common threat became the battleground for the EU and Ukraine. Collective efforts speeded up integration trends and brought collaboration to the level of conflict-management tools for solving problems of contemporary hybrid warfare. The phenomenon of the Kyiv Independent as an example of the media of the new generation gives us a chance to examine the success of independent media sources in countering propaganda as a strategic resource in information warfare. Narrative combination, inclusion, and the problem-orientation approach make national media an international beacon for Ukraine. The application of conflict studies in media is a novel concept that should be given attention by researchers in the field of politics and media; its potential for research is of major significance. The application of new methods should be accompanied by constant linear research efforts to develop scientific reflections of outcomes.

Future study should be based on the aspect of practical implications of conflict studies in media. The concept of discursive transit developed in this research leaves space for further research in the context of conflict and security research. Further research is needed to focus primarily on the methodology of conflict management in media in terms of its form. For this purpose, the method of moderation of focus groups of journalists in different media fits best. Further study should investigate the journalists’ perception of conflict management in media. Comparative work should analyze the materials of focus group sessions and create the blueprint for a universal model of conflict studies in media use. Moreover, this article proposes studying the cultural and ethical elements of the journalist community to adapt a general model for use in different environments. In addition, this study approached the aspects connected to the EU media legislation in 2022–24, and coupled with creation of the Kyiv Independent as a new Ukrainian media tool, it will be rational to take a look at the dynamic changes in this field. The aspect of intervention of state leaders like the United States into the negotiation process in conflicts in the frame of the Russo-Ukrainian War requires extensive analysis. President Joseph R. Biden’s intervention in the exchange of political prisoners and American journalists in August 2024 (with the liberation of Alsu Kurmasheva and Ewan Gerskovich) requires a deep analysis of how this parallels the Cold War frame. Another development is how new emerging interpretations of wartime discourse and propaganda affect the field knowledge. Finally, this author believes that it would be beneficial to study how Russia affects countries with a strong EU and NATO orientation along with a certain amount of pro-Russian sentiment and territorial integrity like Moldova or Georgia. The recent presidential elections in Moldova illustrated that the post-Soviet independent countries are still under information pressure from Russia. This moment is essential due to the recent adoption of the Russian-like law on foreign agents in Georgia.49

Endnotes

1. Catherine A. Theohary, Information Warfare: Issues for Congress (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2018); Yuriy Danyk and Chad M. Briggs, “Modern Cognitive Operations and Hybrid Warfare,” Journal of Strategic Security 16, no. 1 (2023): 35–50, https://doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.16.1.2032; and Armin Krishnan, “Fifth Generation Warfare, Hybrid Warfare, and Gray Zone Conflict: A Comparison,” Journal of Strategic Security 15, no. 4 (2022): 14–31, https://doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.15.4.2013.

2. Daniel Shultz, “Who Controls the Past Controls the Future: How Russia Uses History for Cognitive Warfare,” Outlook, no. 4 (December 2023); and Robin Burda, Cognitive Warfare as Part of Society: Never-Ending Battle for Minds (The Hague: Hague Centre for Strategic Studies, 2023).

3. Thomas Zeitzoff, “How Social Media Is Changing Conflict,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 61, no. 9 (2017): 1970–91, https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002717721392.

4. Robert A. Dahl, “The Concept of Power,” Behavioral Science 2, no. 3 (1957): 201–15, https://doi.org/10.1002/bs.3830020303.

5. “The Vladimir Putin Interview,” Tucker Carlson Network, episode no. 74, premiered 8 February 2024.

6. Volodomyr Kulyk, The Ukrainian Media Discourse: Identities, Ideologies, Power Relations (Kyiv: Krytyka, 2010).

7. Maxime Audinet, Eloïse Fardeau Le Meitour, and Alicia Piveteau, “L’appareil de désinformation russe,” Diplomatie, no. 124 (November–December 2023): 70–72.

8. Jakov Devčić, Serbien: Politische und gesellschaftliche Auswirkungen ein Jahr nach Beginn des russischen Angriffskriegs gegen die Ukraine: Ein Jahr Ukraine (Berlin: Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, 2023).

9. Matt Leighninger, “Can Journalists Use New Technologies to Build a Trusting, Sustaining Relationship with Their Audiences?,” National Civic Review 112, no. 4 (Winter 2024): 17–22.

10. Gavin Wilde and Justin Sherman, No Water’s Edge: Russia’s Information War and Regime Security (Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2023), 6–12.

11. Sofia P. Caldeira, Sander De Ridder, and Sofie Van Bauwel, “Exploring the Politics of Gender Representation on Instagram: Self-representations of Femininity,” DiGeSt. Journal of Diversity and Gender Studies 5, no. 1 (2018): 23–42, https://doi.org/10.11116/digest.5.1.2; Karly Dom Sadof, “Finding a Visual Voice: The #Euromaidan Impact on Ukrainian Instagram Users,” in Digital Environments: Ethnographic Perspectives Across Global Online and Offline Spaces, ed. Urte Undine Frömming, Steffen Köhn, Samantha Fox, and Mike Terry (Bielefeld, Germany:Transcript Verlag, 2017): 239–250, https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/656; and Andrew Housiaux, “Existentialism and Instagram,” Phi Delta Kappan 101, no. 4 (2019): 48–51, https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721719892975.

12. David Gregosz and Daniel Sagradov, Desinformation als Kriegsinstrument: Russische Narrative zur Rolle Polens im Rahmen des Angriffskrieges (Berlin: Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, 2022).

13. Louk Faesen et al., From Blurred Lines to Red Lines: How Countermeasures and Norms Shape Hybrid Conflict (The Hague: Hague Centre for Strategic Studies, 2020), 16–31.

14. Treatment of Prisoners of War and Persons Hors de Combat in the Context of the Armed Attack by the Russian Federation against Ukraine (New York: United Nations, 2023).

15. Francisco López-Cantos, “The Drone Warfare: Fact-checking, Fake-pictures and Necropolitics,” Cogent Social Sciences 10, no. 1 (2024): https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2024.2426706; Beryl Pong, “The Art of Drone Warfare,” Journal of War & Culture Studies 15, no. 4 (2022): 377–87, https://doi.org/10.1080/17526272.2022.2121257; and Dominika Kunertova, “Drones Have Boots: Learning from Russia’s War in Ukraine,” Contemporary Security Policy 44, no. 4 (2023): 576–91, https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2023.2262792.

16. Marek Menkiszak, “Why War Came to Ukraine,” in Russia’s Long War on Ukraine (Washington, DC: Transatlantic Academy, 2016), 2–8; Anthony H. Cordesman and Grace Hwang, The Ukraine War: Preparing for the Longer-term Outcome (London: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2022); Alexander Libman, “A New Economic Cold War?: The Future of the Global Economy after the War in Ukraine,” Horizons: Journal of International Relations and Sustainable Development, no. 21 (Summer 2022): 148–59; Bryant Frederick et al., Pathways to Russian Escalation against NATO from the Ukraine War (Santa Monica, CA: Rand, 2022), https://doi.org/10.7249/PEA1971-1; and André Härtel, “Die Handlungsfähigkeit der EU im Ukrainekonflikt,” in Lehren aus dem Ukrainekonflikt: Krisen vorbeugen, Gewalt verhindern, ed. Andreas Heinemann-Grüder, Claudia Crawford, and Tim B. Peters (Leverkusen, Germany: Verlag Barbara Budrich, 2022), 203–22.

17. Tuukka Elonheimo, “Comprehensive Security Approach in Response to Russian Hybrid Warfare,” Strategic Studies Quarterly 15, no. 3 (2021): 113–37.

18. Simon Hogue, “De cyberguerre à guerre « TikTok » : mobilisation de la participation numérique dans l’effort de guerre ukrainien,” in Le Canada à l’aune de la guerre en Ukraine: penser la sécurité et la défense dans un monde en émergence, ed. D’andré Simonyi and Frédérick Côté (Sainte-Foy, Canada: Les Presses de l’Université Laval, 2024).

19. Pierre Jolicoeur and Anthony Seaboyer, “L’intelligence artificielle russe comme outil de désinformation et de déception en Ukraine,” in Le Canada à l’aune de la guerre en Ukraine,143–64.

20. Mykola Polovyi, “Exploitation of the Right to Freedom of Expression for Promoting Pro-Russian Propaganda in Hybrid War,” Politeja, no. 71 (2021): 171–82.

21. Robert Saunders, “Ukraine at War: Reflections on Popular Culture as a Geopolitical Battlespace,” Czech Journal of International Relations 59, no. 1 (2021): 23–57, https://doi.org/10.32422/cjir.779.

22. Teun A. van Dijk, “Discourse and the Denial of Racism,” Discourse and Society 3, no, 1 (1992) 87–118, https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926592003001005; Teun A. van Dijk, Ideology: A Multidisciplinary Approach (London: Sage Publications, 1998), 200–10; Teun A. van Dijk, Discourse and Power (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 85–100, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-07299-3; James Paul Gee, An Introduction to Discourse Analysis: Theory and Method, 4th ed. (London: Routledge, 2014), 176–77, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315819679; and J. Maxwell, ed., Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1984), 440–46, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511665868.

23. Teun A. van Dijk, “Critical Discourse Analysis,” in Handbook of Discourse Analysis, ed. Deborah Tannen, Deborah Schiffrin, and Heidi Hamilton (Oxford, UK: Blackwell, 2001), 352–72.

24. Norman Fairclough, Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language (London: Longman, 1995), 265–69; and Hillary Janks, “Critical Discourse Analysis as a Research Tool,” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 18, no. 3 (1997), https://doi.org/10.1080/0159630970180302.

25. Zellis S. Harris, “Discourse Analysis,” Language 28, no. 1 (January–March 1952): 1–30; and Jerry A. Fodor and Jerrold J. Katz, The Structure of Language: Readings in the Philosophy of Language (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice–Hall, 1964), 355.

26. Speech Act Theory and Pragmatics, ed. John R. Searle, Ferenc Kiefer, and Manfred Bierwisch (Dordrecht, Netherlands: D. Reidel, 1980), 155–68.

27. Ralf Darendorph, Class and Class Conflict in Industrial Society (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1959).

28. Martin C. Libicki, What Is Information Warfare? (Washington, DC: National Defense University, 1995); and Martin C. Libicki, “Information War, Information Peace,” Journal of International Affairs 51, no. 2 (Spring 1998): 411–28.

29. The State Duma has proposed toughening penalties for articles on “discrediting” the Russian Army and calls for sanctions. “In the State Duma Proposed to Toughen the Responsibility under the Articles on the ‘Discrediting’ of the Russian Army and Calls for Sanctions,” Current Time, 11 February 2025; and “Criminal Code of the Russian Federation” of 13.06.1996 N 63-FZ (as amended on 28 February 2025).

30. Depoliticizing Poland’s Media Landscape: Assessing the Progress of Media Reform in 2024 (Leipzig, Germany: Media Freedom Rapid Response, 2024).

31. MFRR Slovakia Mission Report: Growing Media Capture, Rising Disinformation and Threats to Safety of Journalists (Leipzig, Germany: Media Freedom Rapid Response, 2024).

32. Leen d’Haenens and Willem Joris, “Images of Immigrants and Refugees in Western Europe: Media Representations, Public Opinion, and Refugees’ Experiences,” in Images of Immigrants and Refugees in Western Europe: Media Representations, Public Opinion and Refugees’ Experiences, ed. Leen d’Haenens, Willem Joris, and François Heinderyckx (Leuven, Belgium: Leuven University Press, 2019), 7–18.

33. Dragana Bajić and Wouter Zweers, “The Crisis of the Journalistic Profession in Serbia,” in Declining media Freedom and Biased Reporting on Foreign Actors in Serbia: Prospects for an Enhanced EU Approach (Wassenaar, Netherlands: Clingendael Institute, 2020), 10–15; and Bajić and Zweers, “The EU: Defender of Media Freedom in Serbia?,” in Declining Media Freedom and Biased Reporting on Foreign Actors in Serbia, 16–23.

34. Nevena Ršumović, “The Uncertain Future: Centers for Investigative Journalism in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia,” in Media Constrained by Context: International Assistance and Democratic Media Transition in the Western Balkans (Budapest, Hungary: Central European University Press, 2018), 215–50.

35. Asya Metodieva, Russian Narrative Proxies in the Western Balkans (Washington, DC: German Marshall Fund of the United States, 2019).

36. Miyase Christensen, “Visions of Media Pluralism and Freedom of Expression in EU information Society Policies,” in Media Freedom and Pluralism: Media Policy Challenges in the Enlarged Europe (Budapest, Hungary: Central European Press, 2010), 27–44; James Pamment, “Current EU Policy on Disinformation,” in The EU’s Role in Fighting Disinformation: Taking Back the Initiative (Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2020); and Bognár Bulcsu, “A Culture of Resistance: Mass Media and Its Social Perception in Central and Eastern Europe,” Polish Sociological Review, no. 202 (2018): 202, 225–42, http://dx.doi.org/10.26412/psr202.05.

37. Regulation (EU) 2024/1083 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 April 2024 Establishing a Common Framework for Media Services in the Internal Market and Amending Directive 2010/13/EU (European Media Freedom Act).

38. Procedure 2022/0117/COD: COM (2022) 177: Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on Protecting Persons Who Engage in Public Participation from Manifestly Unfounded or Abusive Court Proceedings (Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation).

39. “Digital 2023: Global Overview Report,” Datareportal, accessed 18 June 2024.

40. “Ukrainians Begin Using Internet More, with 80% Online Every Day, Social Survey Finds,” United Nations, 26 January 2024.

41. Opinions and Views of the Population of Ukraine on State Electronic Services (Kyiv: Kyiv International Institute of Sociology, 2024), 9–16.

42. “Digital 2023: Global Overview Report.”

43. “10 Years of War: A Timeline of Russia’s Decade-long Aggression against Ukraine,” Kyiv Independent, accessed 19 March 2025.

44. Tatiana Zhurzhenko, “A Divided Nation?: Reconsidering the Role of Identity Politics in the Ukraine Crisis,” Die Friedens-Warte 89, nos. 1–2 (2014): 249–67; Elise Thomas, Albert Zhang and Emilia Currey, Covid-19 Disinformation and Social Media Manipulation Trends: Pro-Russian Vaccine Politics Drives New Disinformation Narratives (Barton: Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 2019); and Oxana Shevel, “The Battle for Historical Memory in Postrevolutionary Ukraine,” Current History 115, no. 783 (October 2016): 258–63, https://doi.org/10.1525/curh.2016.115.783.258.

45. Seth G. Jones et al., “Europe’s Evolving Threat Landscape,” in Forward Defense: Strengthening U.S. Force Posture in Europe (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies), 16–31; Zsolt Darvas et al., Ukraine’s Path to European Union Membership and Its Long-term Implications (Brussels, Belgium: Bruegel, 2024); “Russia’s Information Warfare on WMDs in the Ukraine Conflict,” in On the Horizon: A Collection of Papers from the Next Generation, vol. 6, ed. Doreen Horschig and Jessica Link (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2024), 10–20; and Kathleen McInnis et al., Pulling Their Weight: The Data on NATO Responsibility Sharing (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2024).

46. Jakub Kalenský and Roman Osadchuk, How Ukraine Fights Russian Disinformation: Beehive vs Mammoth (Helsinki, Finland: European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats, 2024).

47. Kalenský and Osadchuk, How Ukraine Fights Russian Disinformation.

48. Regulation (EU) 2024/1083 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 April 2024 Establishing a Common Framework for Media Services in the Internal Market and Amending Directive 2010/13/EU (European Media Freedom Act) (Text with EEA relevance).

49. Marc Goedemans, “What Georgia’s Foreign Agent Law Means for Its Democracy,” Council on Foreign Relations, 21 August 2024.