https://doi.org/10.21140/mcuj.2025SI006

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: With the return of great power competition, the Arctic is set to become increasingly relevant for global geopolitics and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO) security. The potential for higher tensions in the region demands that the alliance’s member states strengthen their deterrence vis-à-vis Moscow, a task for which naval forces and the maritime domain as a whole will be pivotal. This article argues that the alliance should consider the establishment of an additional standing NATO maritime group (SNMG) for the Arctic region to undertake missions and operations similar to those that the SNMG 1 has performed during the last few years. Its establishment would enhance maritime domain awareness, naval power, and deterrence in the northern flank, albeit facing significant challenges in terms of force generation and adaptation to cold weather conditions. These challenges, however, should not automatically disqualify the proposal as entirely unattainable, but rather be seen as a longer-term goal.

Keywords: North Atlantic Treaty Organization, NATO, Arctic, maritime strategy, naval power, naval exercises, standing NATO maritime groups

After a period of lower activity in the region following the collapse of the Soviet Union, which saw a notable decrease in U.S. and North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) military presence across the region, the Arctic matters once again in the world of geopolitics.1 For the last two decades, it has gained wider attention in the international community as the thawing of the polar ice cap opens the possibility of sailing across its waters and accessing the rich natural resources lying beneath its seabed. The resurgence of Russian military activity has prompted NATO members to respond by building up their military and naval presence in the North Atlantic, as proven by the reactivation of the U.S. Navy’s 2d Fleet, or the establishment of an additional Joint Force Command (JFC) in Norfolk in 2018. The potential for higher tensions in the region demands NATO partners strengthen their deterrence vis-à-vis Moscow, a quest in which naval forces and the maritime domain will be pivotal. By doing so, regular deployments to the region and naval exercises larger in scale than those currently held stand out as strong alternatives for NATO navies moving forward.

Trident Juncture 2018 was the largest NATO naval exercise in the North Atlantic region since the days of the Cold War. For two weeks, 65 ships, 250 aircraft, and around 50,000 sailors and military personnel conducted a series of Joint maneuvers and drills, showcasing their interoperability and the potential of their Joint effort.2 The exercise sent an important message to Moscow, particularly on the determination of the Atlantic alliance to protect its northern flank and collectively face any potential Russian aggression that may originate in the Arctic. It signaled the end of three decades characterized by low intensity threats at sea and a predominantly land-centric focus of NATO’s efforts, coupled with the negative consequences that the notorious “peace dividends” had for NATO’s maritime posture.3

Trident Juncture also showcased the return of great power competition at sea, following Russia’s invasion of Crimea in 2014 and the progressive naval buildup undertaken by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) to deny the United States and its partners access to the South China Sea region. However, it did not match those of the large-scale naval exercises held in the 1970s and 1980s to deter the Soviet Navy and its Warsaw Pact allies from attacking the alliance. Six years later, the threat posed by Russian submarines, able to strike land-based military and commercial positions in case of conflict, means that NATO allies must strive to deter Russian submarines from operating far into the Atlantic, keeping them as far north as possible.4

U.S. Navy admiral and military theorist J. C. Wylie famously asserted that “the ultimate determinant in war is the man in the scene with a gun. This man is the final power in war. He is control. He determines who wins.”5 Implicit in Wylie’s argument is that to influence events and eventually succeed in any contest, an actor must be present and stay for as long as it is required to achieve its strategic objectives. Today, with prospects for higher instability in the high north and the need to enhance the protection of the alliance’s northern flank, Wylie’s advice is timely. How can NATO, then, increase its collective naval power and deterrent posture in the high north in a new era of great power competition at sea?

To answer the question, this article explores the potential establishment of an additional standing NATO maritime group (SNMG) in the Arctic to enhance naval power and deterrence, while going back to a Cold War-like regional focus of the four groups that comprise the alliance’s standing naval forces to maximize individual contributions of its member states. The long-awaited NATO Alliance Maritime Strategy (AMS) must place more emphasis on the northern flank and help its members.6 The option would likely face two critical challenges: generating the necessary force and capabilities for an additional standing group and adapting to operations under Arctic weather conditions that notably complicate standard operational procedures on board ships and aircraft. Thus, the article argues that while the force generation problems will take years to solve given the budgetary constraints faced by allied governments, the option of an Arctic Standing NATO Maritime Group should not be put off the table, particularly now that many European nations are determined to strengthen the European pillar in NATO.

The Arctic in NATO’s Maritime Strategic Calculus

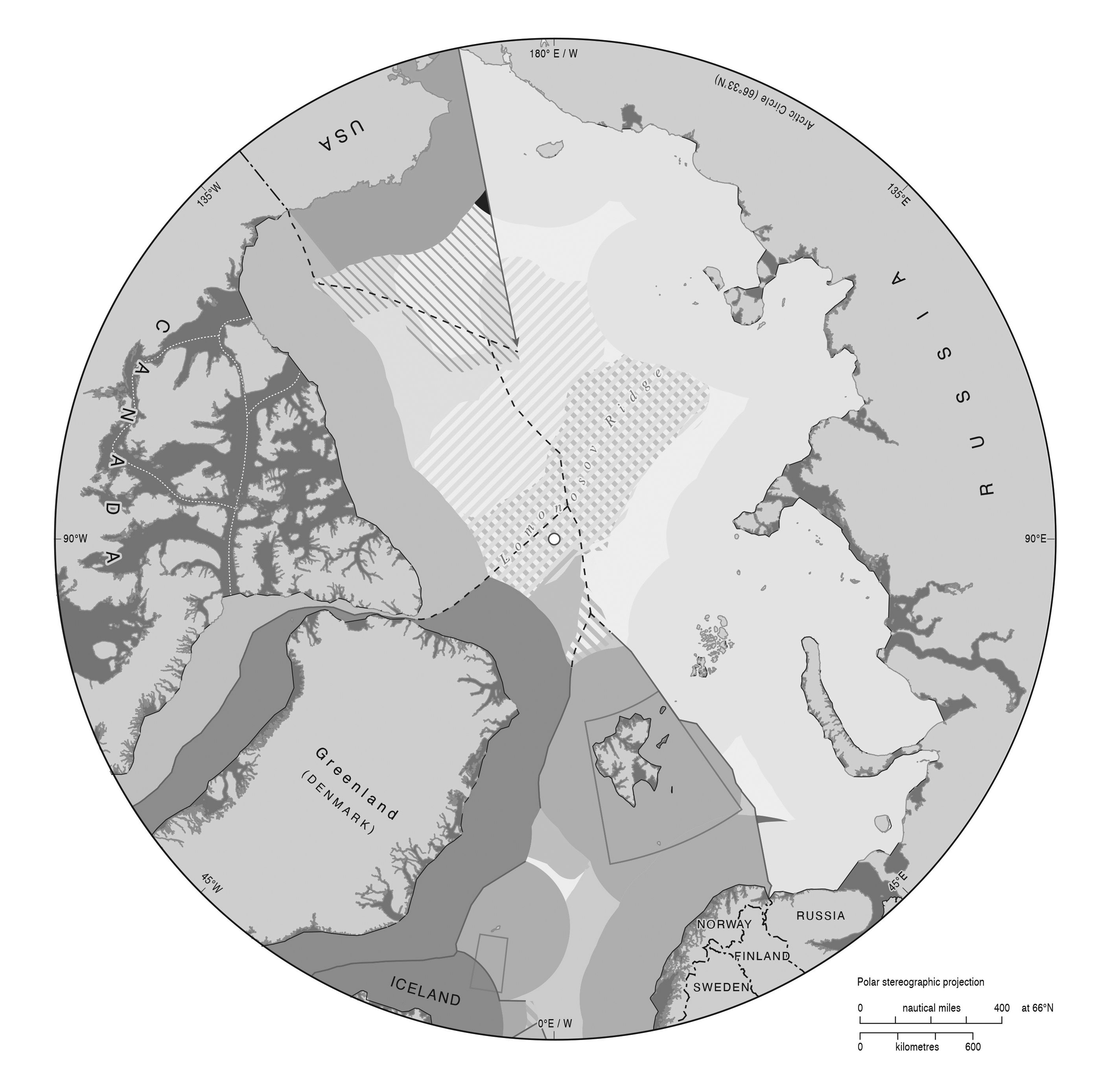

During the last few decades, climate change, globalization, and power transition have all influenced the notable shift in global perspectives toward the Arctic region.7 The thawing of the Arctic ice cap and the overwhelming dependence of the global economy on freedom of navigation is pushing—and will keep pushing—new actors to the region, as commercial routes in the north become highly attractive alternatives to Malacca, Bab el-Mandeb, and other critical choke points in which commercial shipping may be drastically cut without warning (as has happened in the Red Sea region since October 2023).8 At the same time, prospects for further access to rich natural resources lying under the region’s seabed are set to become another key aspect of Arctic countries’ activity across the region, with actors such as Russia, Norway, Canada, or the United States seeking to document their extended continental shelves shown in the map below. While this does not represent a serious security threat per se, it could eventually spark minor tensions among them.9

Following the significant degradation of its military capabilities during the 1990s, the Russian Federation has progressively allocated substantial resources toward reestablishing its military presence in the Arctic region, facilitated by improvements in its economic conditions during the past two decades. These investments, including the modernization of Soviet-era bases and the reinforcement of the Northern Fleet, are partly attributable to strategic recalibrations after the dissolution of the USSR. They also reflect Russia’s evolving perception of regional dynamics and emerging security challenges.10

In particular, the enhancement of Arctic military infrastructure appears aligned with Moscow’s objectives to strengthen homeland defense, ensure long-term access to and control over key economic resources, and develop a platform for strategic power projection vis-à-vis NATO. This orientation has been further reinforced by recent geopolitical developments, notably the accession of Sweden and Finland to NATO, which Russian leadership perceives as a shift in the regional balance and a potential increase in conventional threats along its borders: “Viewed from Moscow, the ‘enlargement’ of NATO closer to Russian borders is feeding a sense of not only vindication but also increased conventional vulnerability.”11 These concerns are formally articulated in the 2022 Maritime Doctrine of the Russian Federation, which outlines national interests, threats, and priorities in the maritime domain. Compared to its 2015 predecessor, the updated doctrine places a stronger emphasis on the socioeconomic dimension of maritime strategy.12

Map 1. Arctic continental shelves’ extension

Source: “IBRU Releases New Arctic Maps,” IBRU: Center for Borders Research, Durham University, 27 February 2023.

During the last decades, several nations far from the Arctic Circle have expressed growing intentions of partaking in Arctic affairs. Among them, China has arguably been the most involved with an increase in its aspirations toward the region. Reflecting on this, the 2024 Arctic Strategy underscores that “though not an Arctic nation, the PRC is attempting to leverage changing dynamics in the Arctic to pursue greater influence and access, take advantage of Arctic resources, and play a larger role in regional governance.”13 People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) vessels have shown the capability to operate near the Arctic in joint deployments with the Russian Navy, with which the PLAN already has a number of relevant joint exercises throughout the year in other regions. In the summer of 2024, Beijing deployed for the first time three icebreakers to the region for a months-long expedition, showcasing the expanding capabilities of its Arctic-capable fleet.14 Although no PLAN warship has been deployed to Arctic waters, the Chinese Coast Guard conducted its first ever patrol in the Arctic with the Russian Border Service in October 2024.15

Under such circumstances, some authors asserted that “the strategic importance of the Barents and Norwegian Seas, the Atlantic and the [Greenland-Iceland-United Kingdom] GIUK Gap to Russia is arguably greater than ever.”16 Thus, NATO finds itself in a position where it needs to strengthen its naval and maritime posture in its northern flank to deter any potential aggression coming from Russia’s submarine-based missile capabilities, a task for which its Standing NATO Maritime Groups deployed on a permanent basis are ideally suited. NATO navies are now striving to bolster their capabilities for high-end naval warfare with stronger investments by their national governments while still paying attention to lower-end maritime security operations.

As highlighted by an expert of Russia and the Arctic, Elizabeth Buchanan, “the Alliance has enduring strategic interests in the High North across challenges related to climate change, critical infrastructure (in)security, data and sea cable security, fisheries, as well as the security of sea lines of communication.”17 Consequently, the waters of the Arctic and the high north are now as strategically relevant for NATO as much as the rest of its flanks, a reality that a future allied maritime strategy should account for.

The 2011 Alliance Maritime Strategy and the Arctic

This strategic importance is not reflected in the alliance’s messaging via formal statements concerning the region, which often tend to avoid featuring the high north (and the Arctic in particular) both in summit declarations and other relevant documents like the 2022 Strategic Concept.18 Actually, “contrary to the Baltic Sea region, NATO has lacked a clear strategic approach to the European Arctic. In fact, some analysts have argued that the alliance has deterred itself from taking a more robust role in the area.”19 At sea, this has also become evident with the Alliance Maritime Strategy, which is expected to be updated soon.

The AMS, published in 2011 and based on the NATO Strategic Concept 2010, remains the only existing official document under such name. During the more than 13 years that have passed since its initial release, the plethora of risks and challenges has extensively multiplied; most notably, it has transformed the seas into one of the main centers of gravity of a new age of great power competition. Considering that the current strategy was primarily based on the 2010 strategic concept, the release of the NATO 2022 Strategic Concept after the summit in Madrid should have been followed by a new update of the AMS.20

The 2011 AMS describes a cooperative maritime environment in which the alliance’s contributions are divided into four different categories: deterrence and collective defense, crisis management, cooperative security, and maritime security.21 It is notable that the document does not make any reference to either China or Russia, which were respectively defined in the NATO 2022 Strategic Concept as a “challenge [to] our interests, security and values” and as “the most significant and direct threat to allies’ security and to peace and stability in the Euro-Atlantic area.”22 This and other examples across the text illustrate the vast changes that have taken place at sea, many of which have rendered the strategy virtually obsolete.

For example, the AMS does not make any reference whatsoever to the Arctic or the high north. While this is understandable given what has been explained above, the deterioration of the situation over the past few years has made it necessary to include the high north in NATO’s naval strategic planning. At the same time, the 2022 Strategic Concept emphasized that Russia’s “capability to disrupt Allied reinforcements and freedom of navigation across the North Atlantic is a strategic challenge to the Alliance,” but it did not make any specific references to the Arctic either.23 Contrasting with this, Royal Netherlands Navy admiral Rob P. Bauer, chair of the NATO Military Committee, stated in 2023 prior to Sweden’s accession:

When Sweden joins, following in the footsteps of Finland, seven of the eight members of the Arctic Council will be NATO Allies. We are grateful to our Nordic Allies for their enhanced cooperation, investment and vigilance in the region. The Arctic has always had a strategic importance to NATO, and we must ensure it remains free and navigable.24

As such, the Arctic, and more generally, NATO’s northern flank, remains an important region in which allied navies must once again adopt a stronger pace of both Joint exercises and naval deployments. In this sense, a potential change in the alliance’s planning following the accession of its newest members, which some reports suggest will eventually happen, is the integration of Norway, Sweden, and Finland under the same Joint Force Command (JFC)—the one in Norfolk.25 This was recently proposed by Dr. Karsten Friis, highlighting that “Norfolk should cover the entire Cap of the North. It makes sense. It is unthinkable to cover Finnmark without the entire Cap of the North militarily. . . . If we can combine our defenses in a joint Nordic region, we will have a better defense. And we need a better naval defense.”26

At the operational level, the U.S. Maritime Strategy of the 1980s (which was more naval than maritime in nature) stands as a prominent example of what effective planning for naval operations in the North Atlantic and the high north looks like. The strategy was developed by the Chief of Naval Operations’ Strategic Studies Group as an effort to counter the Soviet naval presence around NATO’s flanks. It provided a detailed analysis of the strategic situation at the time, followed by the definition of five theaters of vital interest and the Soviet threat within each of them (including Soviet naval capabilities).27 From that assessment, it then derived the means that were necessary to confront and overcome the identified challenges. Those means were crystallized in the 600-ship navy requirement to enforce the strategy and be in a position to defeat NATO’s Soviet counterpart. By so doing, securing the northern flank became a primary objective due to the region’s potential to offset the overall allied position should it fall under Soviet control.28

Although the strategy was put on the shelf after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the subsequent demise of its navy, many of the ideas and the logic that guided its development remain valuable examples for current naval planners in NATO. With the resurgence of the submarine threat in the Norwegian and Barents Seas, and the prospect for a navigable Arctic in the near future, “current trends strongly suggest that it will once again be a key space for maritime operations and presence in the contest between Russia and NATO.”29 Thus, when published, the future AMS should have an associated Concept of Maritime Operations similar to the ones from the 1980s, providing an adequate foundation for naval operations in the region, as well as larger and more frequent multilateral naval exercises to ensure a stable presence to watch over critical undersea infrastructure and other assets in the region.30

Exercises like those conducted during the 1970s and 1980s are very rare today, particularly in the North Atlantic region. This is understandable given the sharp reduction in the size of all NATO navies and armed forces in general (as well as Russia’s). For example, the 1980 NATO Teamwork Exercise witnessed a total of 54,000 NATO personnel deployed to the alliance’s northern region. In contrast, Cold Response 2016 included only 15,000 participants, with Cold Response 2022 doubling that to 30,000.31 Furthermore, while the latest iterations of Dynamic Mongoose have featured around 11 surface ships each time, Northern Wedding 86 had 150 (from 10 participating navies).32 These 1980s exercises provide useful examples of wider exercises that strongly contributed to deterrence in the region in the past. Despite the marked differences between the situation then and now, and thus the limited use of comparisons, the relevance of large-scale exercises to enhance the alliance’s messaging and deterrence toward potential foes has seen a rise in attention.

The most significant examples in recent years, aside from the antisubmarine warfare (ASW)-focused Dynamic Mongoose held annually in the North Atlantic region since 2012, had been Trident Juncture 2018 and Cold Response 2022. Most recently, however, the large-scale Steadfast Defender 2024 exercise was an important milestone for the alliance, lasting more than six months and including more than 90,000 troops from all 32 NATO allies. More importantly, the first part of the exercise had a strong North Atlantic and Arctic focus, which hone in on “on transatlantic reinforcement—the strategic deployment of North American forces across the Atlantic to continental Europe” and included maritime live exercises and amphibious assault training in the North Atlantic and Arctic seas.33 The exercise’s success underscores the potential for further exercises similar in nature, which will inevitably require a strong maritime and naval focus. The accession of Finland and Sweden to NATO is a valuable opportunity to further the integration of their navies in Baltic operations and other current exercises and deployments, although they were already participating in many to some degree.

Operation Ice Camp (previously known as Ice Exercise), last held in the Beaufort Sea in March 2024, is another example of multilateral exercises in the region involving naval and air components of the U.S. Services, the Royal Canadian Air Force and Navy, and the French, British, and Australian navies.34 It provides the opportunity to train together and enhance mutual understanding of challenges in the region, while also providing NATO members with additional presence across the region. It also constitutes a solid template to set up additional exercises with other NATO allies to boost allied naval presence. The Northern Fleet remains one of Russia’s central tools to strike valuable targets in NATO territory, and as such, deterring its nuclear-powered guided missile submarines (SSGNs) and ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) and preventing them from reaching safe strike positions will remain a crucial task. As explained by Steven Wills,

The real SLOC’s worth concern are not the ones leading across the Atlantic, but rather those that allow Russian submarines to move from their home littorals in the Arctic, the Baltic, the Black Sea and the Pacific oceans to positions where they can employ cruise-missiles against land-based military and commercial targets, as well as Western naval units. It is vital for the West to deter the Russians from operating their advanced submarines far into the Atlantic.35

Altogether, “enhancing the frequency and duration of Allied naval forces involves showing presence and readiness in the Arctic.”36 Beyond naval exercises, regular deployments by both the Standing NATO Maritime Groups (SNMGs) and allied submarine forces also hold great potential for enhancing NATO’s naval presence and deterrent capabilities in the high north. The following sections delve into the alliance’s SNMGs and their evolution since they were initially established, to then proceed with a discussion on the potential benefits that the establishment of an Arctic SNMG could bring for the defense of the alliance’s northern flank.

NATO’s Standing Maritime Groups

The SNMGs consist of four main standing groups and constitute the maritime component of the alliance’s rapid response force, responsible for providing a permanent naval presence across the alliance’s maritime flanks from the Black Sea to the Arctic. The existing groups are the evolution of the standing naval forces established during the days of the Cold War, which were initially assigned to specific regions. Standing Naval Force Atlantic was established in 1968 as a permanent version of the Matchmaker exercises promoted by U.S. Navy Rear Admiral Richard G. Colbert and was followed in 1973 with the establishment of Standing Naval Force Channel.37 In the 1990s, Standing Naval Force Mediterranean and the Standing Mine Countermeasures Force Mediterranean were also established, in 1992 and 1999, respectively.

Following the reorganization that left them as they currently stand, they remain valuable assets for their members, providing a relatively balanced presence across all maritime areas of interest without the need to make major investments. However, their current structure is still influenced by two decades of a low-threat maritime environment and, above all, a gradual decline in European naval power. Ships are deployed to the groups for periods of six months, but these last few years have seen a relatively low number of combatants in each group, typically between one and three units rather than the four to nine originally intended.38 Brooke A. Smith-Windsor claims that “since the end of the Cold War, nationally dedicated maritime forces for standing maritime groups have been decreasing sharply.”39 The evolution of the maritime environment during the past decade, the rising costs of threats to critical undersea infrastructure, and the challenge posed by crises such as the ongoing Houthi campaign in the Red Sea, all call for a careful assessment of NATO’s maritime posture.

In the Baltic and the North Seas particularly, NATO must pay attention to the protection of critical undersea infrastructure and the seabed. The latest incident took place in the Baltic Sea in December 2024, when the Estlink 2 undersea power cable connecting Finland and Estonia was damaged along with four telecommunications lines. Following the successful boarding of a suspected vessel by the Finnish special forces hours after the incident was reported, NATO announced the launch of Operation Baltic Sentry.40 The operation has increased maritime patrols around the region, through an effort for which the SNMG 1 and its adjunct SNMCMG 1 have also been deployed to provide additional support.

In light of the growing threats and the demand for a more robust and permanent presence they impose, the case can be made for a more regionalized approach of the standing groups under Allied Maritime Command. Like the original standing naval forces, which were assigned to specific regions to operate, having a more permanent presence of NATO warships around the GIUK gap and farther north would provide the alliance with a credible deterrent posture toward Russia’s growing submarine activity in and around the region. This idea has been proposed in the past by some, including CNA analyst Joshua Tallis, who argues that “the return of a revanchist Russia makes NATO’s previous maritime structure a good source of wisdom for the alliance’s future.”41 If the groups are expected to be a powerful instrument of NATO’s naval activity, particularly for ASW operations, they must be properly resourced.

With their participation in the 2011 Operation Unified Protector (OUP), the standing forces showed that despite their raison d’être as a “a multinational, integrated maritime force . . . that is permanently available to NATO to perform a wide range of tasks, from participating in exercises to crisis response and real-world operational missions,” they were largely unable to act effectively.42 As underscored by Smith-Windsor, “the standing maritime groups can thus serve as a critical building block for a credible crisis management role for Allied navies—but only with sufficient political will to resource them and use them.”43 More than a decade after OUP, their resourcing remains a significant challenge for member states, as will be discussed in the upcoming section exploring the potential establishment of an SNMG Arctic.

Toward an SNMG Arctic?

This section explores the potential establishment of an additional SNMG for the Arctic, as well as a return to a more regionally focused configuration of the alliance’s standing naval forces to strengthen allied naval power and deterrence at sea. Such a shift to their original regional orientation should explore the option of establishing a Standing NATO Maritime Group Arctic (SNMG Arctic), with deployments focused on the North Atlantic region, the GIUK/Greenland-Iceland-Norway gap, and the Bear gap on a more regular basis, following what the SNMG 1 had done in early 2025.44 This section discusses the rationale supporting the need for an Arctic SNMG, followed by an analysis of the force generation challenges that would derive from it.

As highlighted by Mathieu Boulègue, “Northern Fleet operations in the North Atlantic depend on unhampered access for vessels crossing Norwegian waters around the Barents Sea and Svalbard and then transiting via the Greenland–Iceland–Norway (GIN) gap.”45 This means that, in case of conflict, NATO naval forces would have to deploy to the North Atlantic to interdict Russian lines of communication there, preventing the forces stationed at Kola from being properly resupplied. Having a permanent group with combatants fitted for both ASW and antiair warfare (AAW), and regularly conducting patrols over important critical undersea infrastructure, could lend a valuable contribution to the strengthening of NATO’s position in the northern flank both in peacetime and wartime.

The establishment of an SNMG for the Arctic has been put forward in a report published by the U.S. Naval War College’s Newport Arctic Scholars Initiative (NASI), in which its authors make the case for it to strengthen the current contributions and deployments of many members to the alliance’s collective capabilities. As part of the four main recommendations provided, the report underscores that “a standing multinational task force is key for showing readiness in the Arctic maritime domain, either in the form of a Standing NATO Maritime Group or potentially the strengthening of the UK’s Joint Expeditionary Force’s [JEF] maritime function in the High North.”46

As for the JEF, which has experienced force-generation problems akin to those of the SNMGs, the approval of Finland’s initiative for Forward Land Forces (FLF) will be a positive contribution to allied cooperation in the region—one that could provide alternative means to support the JEF.47 Yet, they remain a predominantly land-oriented initiative, and thus, having an SNMG deployed in the region would provide additional capabilities, enhancing maritime domain awareness (MDA) and deterrence in the region. The numerous incidents that have taken place in the Baltic Sea during the last few years are a relevant example of the need for a stronger maritime presence. While existing capabilities available to the alliance may not be enough to allow for its establishment in the short term, that does not imply that the idea should be entirely discarded without further study moving forward.

In practical terms, the SNMG 1 has had a strong regional focus during the last decade, with a continuous presence in the waters of the northern flank (North Atlantic and Baltic) and a serious involvement in most naval exercises conducted in the region (for which the size of the groups was often increased with additional units).48 Yet, the latest incidents in the Baltic Sea and its deployment to the region suggest that more naval presence is required across the northern flank. Thus, the establishment of an SNMG Arctic and the reorganization of the current structure to make additional assets available to be deployed to the north seem to be increasingly plausible and necessary. An SNMG Arctic would provide NATO with both additional deterrence and a faster response capacity in case of attacks to critical undersea infrastructure. In practical terms, the author recommends mirroring the activities performed by SNMG 1.

At the same time, the testing and deployment of unmanned maritime systems integrated in the SNMGs stands as another promising option with the potential to help mitigate the resourcing problems currently affecting the alliance’s maritime posture, as Baltic Sentry is already showcasing.49 The integration of unmanned assets in all SNMGs could be a significant enabler for them, increasing their size and capabilities at a relatively low cost. Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), unmanned surface vehicles (USVs), and unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs) can be integrated as extensions of the higher platforms, supporting maritime patrol and situational awareness tasks to provide the personnel in the larger platforms (e.g., warships) with additional surveillance means and response options. Their potential for mine warfare also makes them valuable assets to be operated from minehunters and minelayers of SNMCMG 1 and SNMCMG 2.50

A standing group operating in the region, with the increased presence of allied naval assets associated with it, would be beneficial to ensure regional forces and national capabilities are better synchronized under the NATO umbrella while they conduct operations in the Barents Sea and in the Bear gap.51 Additional benefits provided by such a force in peacetime would include a “better all domain awareness in the region” and the presence to reassure local communities, while also being a scalable force providing additional flexibility to respond to any hostile action.52 Additionally, the group would also make it more feasible for NATO to conduct freedom of navigation operations to counter Russian maritime claims in the region, something that has only been done in the South China Sea region. Others have proposed the establishment of a NATO coast guard as another alternative to boost allied maritime presence in the region, although such a service would only be composed of smaller and ice-capable units.53

Deployments of an SNMG Arctic could eventually be combined with and integrated into large-scale military exercises with other Services like regional coast guards or the U.S. Marine Corps. Concerning the latter, their growing integration with partner nations’ forces represents an important opportunity in the path toward strengthening deterrence in the region. The Marine Corps’ cooperation with European allies through regular deployments that bolster interoperability among them provides a positive base for further integration with naval assets: “The ability to posture strike platforms such as those envisioned within the U.S. Marine Corps’ Force Design 2030 in areas such as northern Norway during a crisis would also impose dilemmas on Russian theater-level planning. Such systems would pose a considerable threat to facilities such as Severomorsk and would necessarily need to be engaged.”54 Despite all the theoretical benefits derived from the establishment of an additional SNMG, however, supporting the new group would impose significant challenges regarding its resourcing by allied navies.

Resourcing an SNMG Arctic

An Arctic SNMG would ideally involve surface combatant groups from northern European navies, particularly those with experience operating in the Arctic, and with an emphasis on ASW, amphibious, icebreakers, and other forces.55 Norway, Denmark, Germany, and the United Kingdom, with their strong focus in the North Sea and North Atlantic regions, stand as the best suited nations to contribute with assets for a new group. Norway’s permanent presence across the Norwegian and North seas would put Oslo in a position to lead the efforts of the group, with both its Fridtjof Nansen-class and the future class of frigates from which to draw to deploy with the group. The German Navy’s future Type 424 signals intelligence ships and F124 and F125 frigates stand as potential assets for the group as well. Similarly, the Royal Navy’s upcoming Type 26 and Type 31 frigates, of which eight and five units are respectively planned, will also be potential assets on which to rely, given the UK’s strategic interest in the North Atlantic and the Arctic. Both nations’ programs, however, have been subject to delays in their delivery dates.

Denmark announced in March 2025 its plans for the modernization of its fleet, including a new class of frigates planned to replace the Iver Huitfeldt-class currently in service and a new class of patrol vessels.56 With them, Denmark is seeking to bolster its naval presence across its territorial waters and maritime areas of responsibility, while contributing to the alliance’s posture in the region. With them, the future ASW frigates for the Belgian and Dutch navies could also be potentially put in service of the SNMGs in the region should it be required. The ice-capable vessels to be constructed under the 2024 trilateral U.S.-Canada-Finland Icebreaker Collaboration Effort (ICE Pact) may also provide additional means to strengthen allied naval assets in the high north, albeit the U.S. commitment during the next few years is not yet clear given Washington’s recent changes in its traditional role and support for the alliance.57

The Donald J. Trump administration has repeatedly expressed the intention of annexing Greenland to the United States, and criticism of the state of the European defense industry and its capabilities have prompted further unrest regarding Washington’s commitment with its allies.58 While a decrease in American naval presence across European waters is expected, the growing interest of the United States in strengthening its Arctic presence and capabilities could benefit an Arctic SNMG in the future, for example, with the upcoming Constellation-class frigates as potential assets to be deployed in the group. According to Steinar Torset and Amund Nørstrud Lundesgaard’s analysis of the SNMG 1 and its deployments during the last few years, every time a U.S. Navy ship assumed its command, the group saw an increase in the contributions of other allies.59 Thus, having a U.S. presence in the group, at least during part of the year, could benefit NATO’s naval presence in the Arctic, potentially attracting additional support by other allies.

While the accession of Finland and Sweden to the alliance is a positive step forward, it does not necessarily imply that their naval forces would be available to the NATO Arctic group. Finland’s future Pohjanmaa-class corvettes will provide additional capabilities to a fleet primarily oriented toward coastal defense and regional patrols in the Gulf of Finland and the wider Baltic region. Similarly, Sweden’s biggest combatants, like the Visby-class corvettes, remain limited in their operational reach, which makes deployments to the Atlantic very rare for them. Thus, the contribution of both navies with NATO’s maritime presence in the north is likely to remain in the Baltic Sea. This could, in turn, free bigger units of allied navies to be deployed elsewhere when needed.

Beyond the establishment of an Arctic SNMG, the report by Rachael Gosnell and Lars Saunes further suggests “shared multilateral patrols along EEZs and demonstrations on a more regular basis in tandem with the continuation of regular NATO exercises (e.g., Trident Juncture and Cold Response) to demonstrate cohesion of Allied intent and capabilities” as well as placing a “particular emphasis on exercising against hybrid attacks on critical maritime infrastructure to demonstrate our readiness to respond to, and our resiliency against these threats.”60 As has been already said, the protection of critical undersea infrastructure remains a central challenge for which the SNMGs will be called to pay increasing attention in light of recent events in the Baltic region. The launch of Operation Baltic Sentry in response to persistent attacks against undersea cables and pipelines has brought SNMG 1 to the region to assist with patrols, while unmanned maritime systems are also being added to the effort. The deployment of SNMG 1 underscores the need for the alliance to revisit its standing naval forces’ command structure, which could potentially involve more regionalization to favor the contributions of smaller, regional navies.

Altogether, the force generation problems associated with the SNMGs currently represent the biggest challenge in the quest toward the potential establishment of an SNMG Arctic. While the proposals of the cited report are promising, attention still needs to be paid to these obstacles as allied nations move forward with their ambitions to increase recruitment and retention of personnel. Most allied navies are currently struggling to increase the size of the fleets and strengthen their naval capabilities, and managing to find additional warships to deploy under the leadership of the standing groups will demand higher commitments on the side of national governments. Yet, the fact that the alliance is currently unable to properly resource them or establish additional groups does not necessarily imply that the option of a future SNMG Arctic should be disregarded as absurd or unnecessary. As has been previously underscored, the rapid development and integration of unmanned maritime assets in allied fleets stands as a promising opportunity for the SNMGs.

Discussing the potential and alternative approaches for the establishment of an SNMG Arctic in the future with unmanned technologies in mind could benefit the alliance and provide further insights in addressing the challenges ahead. For example, amid the current trend of faster disengagement by the United States from its European allies, paired with demands for stronger contributions and a foreign policy that has included claims of an intended annexation of Greenland, prospects for stronger European naval presence in the northern waters could become a stabilizing factor between both sides of the Atlantic at a time when Washington is also looking to build up its maritime presence in the high north. Washington has emphasized the need for additional efforts to bolster European defense by strengthening existing capabilities, a task in which the SNMGs must also be included.

Finally, while efforts to counter Russian hybrid threats at sea will be valuable for the collective posture of the alliance, regular deployments and exercises by the SNMGs and allied navies in general must also consider the potential for any unintended miscalculation that may end up leading to an escalation in the region. Seeking to avoid misinterpretation by Moscow while building up allied collective deterrence will also be a delicate balance to strike. SNMG operations in the high north, both in the Baltic and the Northern Atlantic-Arctic, must thus be framed within a clear maritime strategy that openly articulates the alliance’s security needs while minimizing the risk of Russian misinterpretations. Russia is bound to increase the aggressive tone of its rhetoric if additional NATO naval forces are deployed to the north of the Bear gap. Thus, alliance messaging regarding the rationale for additional presence should primarily emphasize defensive, environmental, and stability-oriented goals, rather than punitive and aggressive objectives.

Operational Challenges in Cold Weather

Increasing the frequency of deployments to the region and—potentially—having an Arctic SNMG brings certain operational challenges for warships and their crews. As argued by U.S. Navy lieutenant Colin Barnard, “instead of relying exclusively on frigates and destroyers from NATO navies to form the new group, NATO should look to its coast guards as well, recognizing that many of these forces field ships that are optimized for Arctic operations.”61 Patrol vessels from regional coast guards, such as Denmark’s Knudd Rasmussen-class, Canada’s Harry DeWolf-class, or Iceland’s Thor-class would be important assets for the groups, providing a stable number of ships deployed at all times. Finding the proper equilibrium between these and the bigger frigates and destroyers will be an important requirement, as the latter of them are also necessary to complement the deterrent value of the group. Yet, challenges associated with these deployments, particularly for the equipment and the platforms’ mobility, should be carefully considered.

The 2024 Arctic Strategy emphasizes that “operating in Arctic conditions requires appropriate training, equipment, and supplies for individual service members. Ground, air, and naval mobility platforms require specific sustainment operations not only to function in extreme cold weather, but also through other difficulties that now characterize Arctic conditions.”62 Warships and their weapon systems, equipment, and crews must be designated and trained to operate in winter conditions, which impose a number of constraints and differences when compared to naval operations in warmer regions. NATO’s 2007 Naval Arctic Manual provides a compact yet extensive guide on these particularities. Among the environmental conditions that affect ships and equipment, forces find: low surface air temperatures; snow, sleet and freezing rain; fog and overcast at the ice/water interface; or abnormal magnetic conditions.63 These and other related conditions directly affect the safety of the crews, making the risk of breakdowns and other technical failures higher during winter; and most importantly, they have effects in all areas of naval warfare.

In particular, mine countermeasure vessels are not fit for icebreaking with all the hull-mounted sensors and antimagnetic materials they carry, while the ice can pose problems during the mine laying process and the cold can affect the cranes for mine loading.64 While cold waters are excellent for ASW acoustics, hull-mounted sonars and towed arrays can be damaged by the ice, and the latter remains a clear obstacle for effective surface persecutions of submarines. In this sense, embarked helicopters with dipping sonars and ASW torpedoes can be an effective measure to help.65 With AAW, sensors onboard the ship are exposed to icing at certain temperatures, while snowfall lowers visibility from the air, complicating target identification and the use of cameras or infrared trackers. Additionally, drastic temperature changes can affect the sensitivity of electronic warfare sensors and systems.66 For navigation, icefields often reduce the speed of ships, which are forced to seek open waters whenever possible, helped by UAVs and helicopters employed for ice scouting. Cooperation with the U.S. Coast Guard and ships like icebreakers is also fundamental to receive informational awareness of the ice situation.67

Electronic equipment must be carefully kept and regularly checked for icing, particularly those items that are most exposed. Communications in high latitudes are affected both by electronic storms and ionospheric disturbances and special procedures have to be taken to ensure the satisfactory operation of electronic equipment at temperatures lower than -2º Celsius.68 Antennas, for example, “suffer sea-spray icing in the northern latitudes. The thicker the ice on the antenna, the greater the loss imposed on the signal. Factors such as air temperature, salinity of the water, structural shapes, and wind velocity play key roles in the antenna icing process and should be taken into consideration when operating in the area.”69

In a similar fashion, unmanned systems, including maritime and aerial drones, are also expected to face similar challenges in the high north’s weather conditions. In the case of UAVs, for example, “only the largest, long-range models have enough power for anti-icing systems like those used by aircraft. Cold, fog, rain or snow can cause a malfunction or crash.”70 When operating in temperatures near 0º Celsius, UAVs are often hampered by a thin layer of ice that covers their wings and propellers, rendering them obsolete in a very short time. These operational challenges greatly complicate their employment in large numbers as may be done in other regions with a warmer climate. Unlike UAVs, surface and (especially) underwater unmanned vehicles are better suited to operate in cold waters, thus offering valuable alternatives to strengthen undersea vigilance of critical infrastructure in the region.

Altogether, Arctic naval operations bring along a completely different set of tactical and technical challenges that require careful assessment and continued training of allied forces deployed to the region. Thus, “as the demand for Arctic operations increases, cold-weather training must be increased. Navies with Arctic capabilities and experience should regularly exercise with others interested in building similar capabilities.”71 As NATO moves forward seeking to strengthen its naval capabilities and presence in the high north through regular deployments and large-scale naval exercises, technical factors such as those just described will also have to be considered to avoid any potential mishaps and unnecessary accidents.

Conclusions

For the last several decades, the low tension that has characterized the Arctic region has changed. Russia’s assertiveness in the region and the prospects of enhanced cooperation with China both in commercial and naval terms remain an important concern for NATO’s strategic calculus in the high north. More importantly, the looming threats in the alliance’s maritime flanks from the Black Sea to the Arctic have highlighted the need for a stronger naval presence and deterrence, following Admiral J. C. Wylie’s famous dictum.

In light of this, this article has discussed the potential establishment of an SNMG Arctic, which would provide a continuous naval presence across the region, and a forum where NATO’s northern navies can strengthen interoperability with other partner navies. Such a group would have to be resourced with both ice-capable vessels and larger surface combatants to provide a balanced mix of high- and low-end naval capabilities. The establishment of a permanent naval force in the region would face two critical challenges. The first is the force generation necessary to build up the group, which should primarily be resourced with the already mentioned mix of high- and low-end capabilities by the alliance’s northern navies, and with the participation of other allies when necessary. The second includes all the operational challenges associated with naval operations in the difficult weather conditions of the region and the additional training and maintenance that would be required to ensure warships and crews can operate safely and effectively.

Neither of them, and particularly that of the generation of force and capabilities, is likely to be solved in the short term. However, even if the establishment of an SNMG Arctic is not currently feasible given those shortfalls, that does not necessarily mean that the option should be completely discarded. On the contrary, a new Alliance Maritime Strategy should pave the way to achieve this or similar goals in terms of increased naval presence across the alliance’s maritime flanks. The current push among European member states to increase defense spending and the positive impact it may have on allied navies should also serve as a promising incentive. The return to a more regionalized approach for the SNMGs in a way that includes the contributions of local smaller navies, which are often geared toward operations near their waters and have a better knowledge of the operational environment, would likely have a positive impact on the overall posture and readiness of the alliance’s SNMGs.

Endnotes

1. Note the difference between the terms Arctic and high north. While the former refers to the geographical region within the Arctic Circle, which includes eight different states, the high north refers to the European Arctic and the northern flank of the continent from the Russian border to the Atlantic.

2. “Trident Juncture 2018,” NATO, 29 October 2018.

3. Jeremy Stöhs, “Into the Abyss?: European Naval Power in the Post–Cold War Era,” Naval War College Review 71, no. 3 (2018).

4. Steven Wills, “ ‘These Aren’t the SLOC’s You’re Looking For’: Mirror-Imaging Battles of the Atlantic Won’t Solve Current Atlantic Security Needs,” Defense & Security Analysis 36, no. 1 (2020): 39, https://doi.org/10.1080/14751798.2020.1712029.

5. J. C. Wylie, Military Strategy: A General Theory of Power Control (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1967; repr., Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2014), 72.

6. Alliance Maritime Strategy (Brussels, Belgium: North Atlantic Treaty Organization, 2011).

7. Lisa Kauppila and Sanna Kopra, “China’s Rise and the Arctic Region up to 2049—Three Scenarios for Regional Futures in an Era of Climate Change and Power Transition,” Polar Journal 12, no. 1 (2022): 148–71.

8. Basil Germond, “Maritime Power Shapes the World Order—and Is Undergoing a Sea Change,” Conversation, 8 February 2024.

9. Additionally, following his victory in the 2024 U.S. elections, Donald J. Trump announced his intentions to “take over” Greenland, a pledge he had already made during his first term in office. The potential for a rise in tensions among NATO partners as a result of such a move has been received with deep concerns by most allied nations. See Alys Davies and Mike Wendling, “Trump Ramps up Threats to Gain control of Greenland and Panama Canal,” BBC News, 8 January 2025; and Steve Holland, “Trump Tells NATO Chief the U.S. Needs Greenland,” Reuters, 14 March 2025.

10. Heather A. Conley, Matthew Melino, and Jon B. Alterman, The Ice Curtain: Russia’s Arctic Military Presence (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2020).

11. Mathieu Boulègue and Duncan Depledge, “The Face-off in a Fragmented Arctic: Who Will Blink First?,” RUSI, 24 May 2024.

12. “2022 Maritime Doctrine of the Russian Federation,” Russia Maritime Studies Institute, U.S. Naval War College, 31 July 2022, 16. Translated to English by Anna Davis and Ryan Vest.

13. 2024 Arctic Strategy (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 2024), 3.

14. Malte Humpert, “China Deploys Three Icebreakers to Arctic as U.S. Presence Suffers after ‘Healy’ Fire,” gCaptain, 20 August 2024.

15. Astri Edvarsen, “China’s Coast Guard on First Patrol in the Arctic with Russia,” High North News, 4 October 2024.

16. Magnus Nordenman, “Back to the Gap: The Re-emerging Maritime Contest in the North Atlantic,” RUSI Journal 162, no. 1 (2017): 26, https://doi.org/10.1080/03071847.2017.1301539.

17. Elizabeth Buchanan, Cool Change Ahead?: NATO’s Strategic Concept and the High North NATO, Policy Brief no. 7 (Rome, Italy: Defence College, 2022), 1.

18. Buchanan, Cool Change Ahead?, 2.

19. Matti Pesu, NATO in the North: The Emerging Division of Labor in Northern European Security, Briefing Paper no. 370 (Helsinki: Finnish Institute for International Affairs, 2023), 4.

20. NATO 2022 Strategic Concept (Madrid, Spain: NATO, 2022).

21. Alliance Maritime Strategy (Brussels, Belgium: NATO, 2011).

22. NATO 2022 Strategic Concept, 4.

23. NATO 2022 Strategic Concept, 4.

24. “Arctic Remains Essential to NATO’s Deterrence and Defense Posture, Says Chair of the NATO Military Committee,” NATO News, 21 October 2023.

25. “Norge i Nato-kommando med Sverige og Finland,” ABC Nyheter, 14 June 2024.

26. Trine Jonassen, “From Global to Regional: NATO Has Come Home,” High North News, 14 August 2024.

27. On the U.S. maritime strategy, see, for example, John D. Hattendorf and Capt Peter Swartz, U.S. Maritime Strategy in the 1980s (Newport, RI: U.S. Naval War College, 2018); John F. Lehman Jr., “The 600-Ship Navy,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 112, no. 1 (January 1986); and Adm James D. Watkins, “The Maritime Strategy,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 144, no. 1 (January 1986).

28. David F. Winkler, “Vice Admiral Hank Mustin on New Warfighting Tactics and Taking the Maritime Strategy to Sea,” CIMSEC, 29 April 2021.

29. Nordenman, “Back to the Gap,” 24.

30. See Peter Swartz, “Preventing the Bear’s Last Swim: The NATO concept of Maritime Operations (ConMarOps) of the Last Cold War Decade,” in NATO’s Maritime Power 1949–1990, ed. I. Loucas and G. Maroyanni (Piraeus, Greece: European Institute of Maritime Studies and Research, Inmer Publications, 2003).

31. Rowan Allport, Fire and Ice: A New Maritime Strategy for NATO’s Northern Flank (London: Human Security Center, 2018), 40–41.

32. John Jones, “NATO Launches ‘Northern Wedding 86’ Maneuvers,” UPI, 29 August 1986.

33. “Steadfast Defender 24,” NATO, updated October 2024.

34. Lt Michaela White, USN, “Navy Launches Operation Ice Camp 2024 in the Arctic Ocean,” Commander Submarine Force Atlantic News, 8 March 2024.

35. Wills, “ ‘These Aren’t the SLOC’s You’re Looking For’,” 39.

36. Rachael Gosnell and Lars Saunes, Report No. 2: Integrated Naval Deterrence in the Arctic Region—Strategic Options for Enhancing Regional Naval Cooperation (Newport, RI: U.S. Naval War College, 2024), 20.

37. Operation Matchmaker was a series of naval exercises conducted in the 1960s, envisioned as an initiative to conduct Joint exercises among NATO navies, in which four to six combatants from different navies were deployed annually for six months. After three iterations (Matchmaker I in 1964, Matchmaker II in 1965, and Matchmaker III in 1967), RAdm Colbert, who was serving as deputy chief of staff and assistant chief of staff for Policy, Plans, and Operations to the Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic, Adm Thomas H. Moore, pushed for the establishment of a permanent Matchmaker squadron to conduct Joint exercises and operations. In January 1968, Standing Naval Force Atlantic was officially established. For further details on the origins of the naval forces and the Matchmaker exercises, see John B. Hattendorf and Stanley Weeks, “NATO’s Policemen on the Beat,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 114, no. 9 (September 1988); and John B. Hattendorf, “Admiral Richard Colbert,” Naval War College Review 61, no. 3 (2008).

38. Joshua Tallis, “NATO’s Maritime Vigilance: Optimizing the Standing Naval Force for the Future,” War on the Rocks, 15 December 2022.

39. Brooke A. Smith-Windsor, NATO’s Maritime Strategy and the Libya Crisis as Seen from the Sea (Rome: NATO Defence College, 2013), 6.

40. “NATO Launches ‘Baltic Sentry’ to Increase Critical Infrastructure Security,” NATO News, 14 January 2025.

41. Tallis, “NATO’s Maritime Vigilance.”

42. “NATO’s Maritime Activities,” NATO, updated 3 August 2023.

43. Smith-Windsor, “NATO’s Maritime Strategy and the Libya Crisis as Seen from the Sea,” 6.

44. George Allison, “NATO Increases Patrols in GIUK Gap,” UK Defence Journal, 24 March 2025.

45. Mathieu Boulègue, Russia’s Military Posture in the Arctic: Managing Hard Power in a “Low Tension” Environment (London: Chatham House, 2019), 9.

46. Gosnell and Saunes, Report No. 2, 11.

47. Karsten Friis, “Reviving Nordic Security and Defense Cooperation,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2 October 2024.

48. Steinar Torset and Amund Nørstrud Lundesgaard, “Maritime-Strategic Integration and Interoperability in NATO: The Case of Standing NATO Maritime Group 1 (SNMG1),” in NATO and the Russian War in Ukraine: Strategic Integration and Military Interoperability, ed. Janne Haaland Matlary and Rob Johnson (London: Hurst, 2024).

49. Elisabeth Gosselin-Malo, “NATO Draws up Plans for Its Own Fleet of Naval Surveillance Drones,” Defense News, 3 December 2024.

50. Eunhyuk Cha, “New Mine Warfare USV Unveiled by ROK Navy,” Naval News, 14 March 2025.

51. Gosnell and Saunes, Report No. 2, 20.

52. Gosnell and Saunes, Report No. 2, 22–23.

53. Andrew Erskine, “A High North Coast Guard for NATO: The Need for More Arctic Maritime Awareness in NATO’s Strategic Concept,” Atlantica Magazine, 24 January 2023.

54. Sidharth Kaushal, “Europe’s Marines in the Future European Littoral Operating Environment,” War on the Rocks, 5 February 2024.

55. Gosnell and Saunes, Report No. 2, 22.

56. Robin Häggblom, “Denmark Unveils New Fleet Plan for Royal Danish Navy,” Naval News, 31 March 2025.

57. Aaron-Matthew Lariosa, “U.S. Signs Icebreaker Pact with Finland, Canada,” USNI News, 13 November 2024.

58. Lili Bayer and Sabine Siebold, “Rubio: U.S. Is Committed to NATO, but Europe Must Spend More on Defence,” Reuters, 8 April 2025.

59. Torset and Lundesgaard, “Maritime-Strategic Integration and Interoperability in NATO,” 88.

60. Gosnell and Saunes, Report No. 2, 20–21.

61. Lt Colin Barnard, USN, “Why NATO Needs a Standing Maritime Group in the Arctic,” CIMSEC, 15 May 2020.

62. 2024 Arctic Strategy, 11.

63. Naval Arctic Manual, ATP 17(C) (Brussels, Belgium: NATO, 2017), 5-1.

64. Cdr Mika Raunu, FN, and Cdr Rory Berke, USN, “Professional Notes: Preparing for Arctic Naval Operations,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 144, no. 12 (December 2018).

65. Raunu and Berke, “Professional Notes.”

66. Raunu and Berke, “Professional Notes.”

67. Raunu and Berke, “Professional Notes.”

68. Naval Arctic Manual, 8-2.

69. Naval Arctic Manual, 8-4.

70. Jacob Gronholt-Pedersen and Gwladys Fouche, “ ‘We’re All Having to Catch Up’: NATO Scrambles for Drones that Can Survive the Arctic,” Reuters, 30 January 2025.

71. Raunu and Berke, “Professional Notes.”