PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

I have just returned from visiting the Marines at the front, and there is not a finer fighting organization in the world.

~ Gen Douglas MacArthur,

21 September 1950, near Seoul

As the 75th anniversary of the start of the Korean War approaches, the time is ripe for reexaminations of the Battle of Inchon (15–26 September 1950) and for visiting the sites of the U.S. and South Korean forces’ landing that led to the recapture of Seoul from North Korean forces. This article surveys the history of the Inchon landing and analyzes some of the landing sites and planning and explore associated markers and museums to serve as a field guide for those travelling to Korea to commemorate the event.

On 15 September 1950, Inchon (now Incheon), a port city just southwest of the capital of Seoul, was cemented in military history due to the daring landing that changed the nature of the war to that point. While the landing was not an easy one—when General Douglas MacArthur insisted on the site the planners thought that the landing was doomed to fail—it has remained as a point of commemoration for Koreans and Americans alike.

Inchon and Its Significance

Inchon is a port city that sits approximately 20 kilometers (12.4 miles) southwest of Seoul central. The city has a large port and has contributed substantially to the growth and development of Korea.

Starting in the late 1890s, a considerable number of Chinese laborers moved to Inchon to work on the ships that brought goods into its port. This was extended when the Japanese exerted informal and then, after 1910, formal control of the Korean peninsula. The port offers access to Seoul and to the rail networks that extend from the capital city. The downside of the port is its major tidal swing between high and low tide: 31 feet, or approximately 8 meters.[1] Flying Fish Channel is where the difference in the tide is most perceptible.[2] As one drives over the modern Inchon bridge toward Inchon International Airport (built on a manmade island) the mud flats are clearly visible at low tide and extend well out into the bay. This shift also is one that allowed military planners to think that the port was basically unassailable.

The War in August 1950

Many American servicemembers, regardless of Service branch, are unaware of the Korean War or the significance of the Inchon landings. Often, military students even in the Republic of Korea (ROK) have not read about the conflict. On 15 August 1945, as the Japanese government surrendered to the Allies, unofficially ending World War II, the Korean people declared independence from the Japanese government. The Allied powers, in this case consisting of Soviet troops from the north and U.S. troops from the south and east, temporarily occupied the Korean peninsula with the hope of giving the newly independent people time to establish a government. To easily show the area occupational troops would control, an arbitrary dividing line at the 38th parallel was established, devised by two U.S. colonels, David Dean Rusk and Charles H. Bonesteel. This divided the country roughly in two and was not meant to be a permanent dividing line.[3]

The United States placed an initial force of 50,000 troops in Korea during its occupation from 1945 to 1949, shifting to the Korean Military Advisory Group in 1948–49, which consisted of 500 officers and enlisted to train ROK Army forces.[4] The main leader who was pushing for the role of president in the south was Syngman Rhee, who had been educated in the United States. In the north, the communists relied on the leadership of Moscow-trained leader Kim Il-Sung.[5] Neither political faction wished the other to rule a unified country, and by 1948 when elections were expected both sides boycotted. Of the two zones, North Korea had most of the industry, while South Korea was more agriculturally driven.

Following the major Cold War events was a short period during which the USSR detonated its first atomic bomb (29 August 1949) and the establishment of the Peoples Republic of China was declared (1 October 1949), seemingly demonstrating the spread of Communism. By the early 1950s, Kim was asking Joseph Stalin for Soviet assistance in launching a war to unify the peninsula by force. After an initial reluctance to spur a wider war on Stalin’s part and with assurances from Chinese leader Mao Zedong, Kim ordered the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK, or North Korea) to attack the south. On 25 June 1950, the war was launched.[6]

The War

In the early morning hours of 25 June 1950, the forces of the DPRK, armed in part by the USSR, crossed the 38th parallel. The timing was significant, as many ROK soldiers were on leave, with the result that many units were understrength. The DPRK pushed forces south quickly, and the situation seemed dire. During this time, the South Korean delegation appealed to the United Nations (UN) Security Council for intervention. Due to a series of events, a vote was taken and the United States and United Nations immediately responded with a commitment of troops.[7] The first formal meeting between UN forces—elements of the 25th Infantry Division of the U.S. Army, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Charles B. Smith—and DPRK armor columns occurred just north of the city of Osan on 5 July 1950. The battle lasted for approximately 90 minutes until UN forces were forced to retreat to the south.[8]

From this point, the UN forces and ROK forces maintained a slow but steady retreat to what was known as the Pusan Perimeter.[9] By late July, the battle lines became settled and desperate: there was a pocket in the lower southeast corner of the Korean peninsula, with the front line extending from the city of Daegu going east to the city of Pohang and south to the village of Masan-ni. Pusan (now Busan) was the largest city, and the main support port, for all troops and material fighting in Korea. The fighting along this front was desperate, with many units thrown piecemeal into positions to hold the line.[10]

For the U.S. Marines, their area of operations by August of 1950 was the lower part of the line to the West of Pusan, near the area of Masan-ni. The 1st Provisional Marine Brigade was formed hastily and sent to Korea to hold the line.[11] Many of the Marines had been on occupational duty in Japan and were some of the first to be activated and sent to the front. While most of the 1st Marine Division was being activated and loaded in the U.S. mainland for the trip to Korea, the initial planning for the counterstrike against the DPRK was being planned.

Operation Chromite

In August of 1950, the head of the U.S. Army in Asia (and de facto ruler of Japan during the occupation from 1945 to 1954), General Douglas MacArthur stated to the U.S. high command that a decisive counterstroke was necessary to force the Communists back over the 38th parallel. The idea was that an Allied landing on the west coast of the Korean peninsula would allow the Allied forces to conduct a “hammer and anvil” operation, in which the landing force of U.S. Marines would be able to gain a foothold and serve as the anvil, while the now designated Eighth Army would break out of the Pusan Perimeter and quickly serve as a hammer against over-extended North Korean forces.[12]

There were three locations considered for this landing.[13] The first was near the city of Kunsan (Gunsan) along the southwest coast. While it offered a landing beach and was close to the Pusan Perimeter, it was not bold enough for the shock-and-awe strategy MacArthur envisioned. The general area is now the location of the Kunsan Air Base, which is home to U.S. Air Force fighter wings.[14]

The second location was near the Pyeongtaek location, located approximately 54.7 kilometers (34 miles) south of Seoul. While it offered landing beaches and a good port location, it also was deemed insufficient for the overall operation, as it was not close enough to effect a surprise, yet it did allow access to road and rail networks going into Seoul.

The landing site that MacArthur insisted on was the one that would offer the most gain but also posed the biggest risk: Inchon. The port was a mere 24 kilometers (15 miles) from downtown Seoul, offered port services for supply of UN forces, and would allow those same forces the ability to hit well behind DPRK supply lines. However, the risks, due to Flying Fish Channel’s 31.5-foot tidal change, were substantial.[15] It introduced two critical issues that jeopardized the landing: first, the ships could not land for 12 hours, so the units that landed in the first wave would have to hold their position for half a day; and second, if ships were caught in the basin when the tide receded, they could very well be beached and their hulls subjected to gunfire. Members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff familiar with the plan told MacArthur that the plan was foolhardy and would fail. Even MacArthur gave the operation only a limited chance of success, reportedly saying that the landings might only have a 5,000-to-1 chance of succeeding. There was also the issue of the landing force, which was still being amassed.[16]

The weather was also a concern. Not only did the Allies have to deal with the tides and natural sea conditions, but it was also the time of year in which typhoons form suddenly. A further complication was that passage conditions needed to be optimal for the ships coming from the United States to Asia, to the port facilities in Japan (where further materiel would be loaded), and the trip from Japan to Inchon. Landing day was 15 September. During that time, there was hard fighting along the Pusan Perimeter, two typhoons (Jane and Kezia) that tore across the general area, and political arguments. Into this maelstrom went the Marines of 1st Marine Division.[17]

Anyone visiting Inchon today can locate several key landing locations while walking or using the city’s light rail system around the area. To start, a visitor need only take the Line 1 (Dark Blue) to the Inchon terminus station. It is a short ride to Wolmi-do, and from there one can walk the routes between several historical markers of the landing and related museums. A taxi is the best option for getting to the Wolmi Theme Park to access the first location.

Green Beach Marker, Wolmi-do. The text on its plaque reads: “This point is one of the 3 places (Red Beach, Blue Beach, Green Beach) where US 1st Marine Division and ROK 1st Marine Regiment landed with 261 warships led by Commanding General Douglas MacArthur at dawn on 15 September 1950 for the successive Inchon landing operation.” All three markers have the same inscription. This marker is next to the sea and is a favorite spot among locals for fishing.

Photo by Cord Scott

The Landings

On the morning of 15 September at 0630, elements of the 3d Battalion, 5th Marines, were slated to land at what was designated Green Beach.[18] Intelligence reports had a small detachment of North Korean soldiers (the 226th Independent Marine Regiment) and an artillery detachment, the 918th Artillery Regiment, on Wolmi Island, estimated at 600 personnel, with a total of 2,500 estimated to hold the area between Inchon to Gimpo to the northwest.[19] Wolmi Island was considered the key to the entire operation, as it offered high ground as well as the ability to harass any shipping for the rest of the day. The Marines landing at Green Beach had to seize and hold the island for 12 hours until the tide returned and could drop the remainder of the Marines and elements of the U.S. Army 7th Division on the other two beaches (the Army landed at Blue Beach). The area had also been surveyed by ROK commando units to gain accurate information.

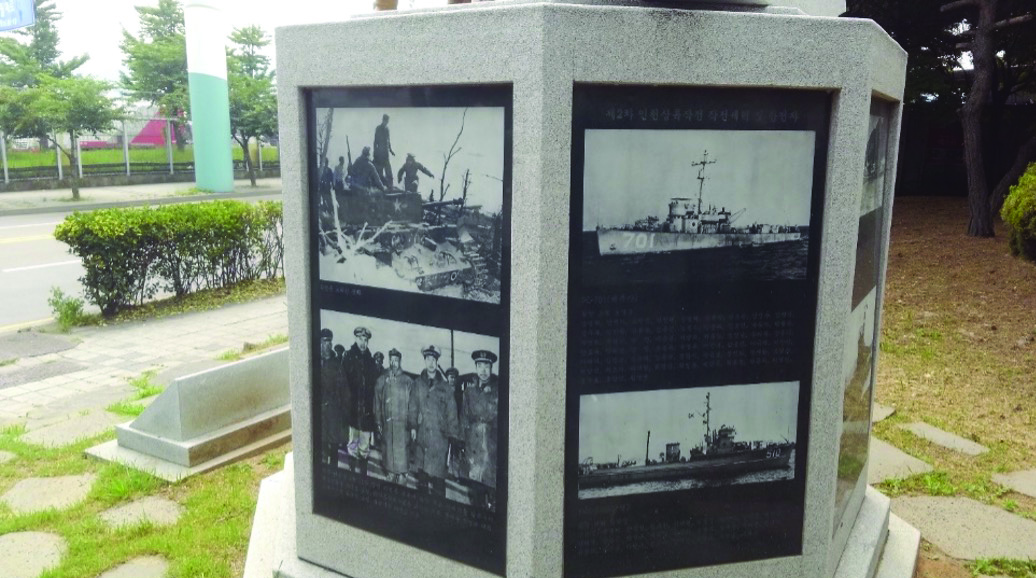

The monument dedicated to the ROK Marine Corps commandos who scouted the landing areas, then carried out a second landing in February 1951. This monument is next to the Red Beach marker, not far from Inchon train station.

Photos by Cord Scott

Modern Green Beach and its marker sits at the northwest shore of Wolmi peninsula (the island now has a road and reclaimed land), not far from the Wolmi Theme Park. The marker, like its counterparts for Red and Blue Beaches, is simple and is located near the spot where forces came ashore. All of the landing beach markers are of dark granite with light granite wings and sit on a light granite pedestal, standing a little taller than six feet. The markers are simple to showcase the location rather than evoke particular emotions. Each marker has the same information in both Korean and English. Of the three markers, only the Green Beach marker is next to water, demonstrating the economic success of the Korean economy in the years since the war. Due to how much of the area has been reclaimed from the bay as a result, Red and Blue Beach markers now sit well inland of the original landing sites. A quick survey of the terrain at these markers gives an idea of what the Marines may have faced on landing and where they had to go. The Green Beach marker is located just north of the Wolmi Theme Park along the shore.

Visitors can get an idea of the terrain and conditions Marines had to navigate. Nearby is a cultural center with some monuments dedicated to the ROK Navy. A hill dominates the island and allows for a commanding view of the port and the inlet—the reason for its strategic importance.

To the east, there is a quick reference guide for the monorail. Follow the monorail as it heads toward Inchon and the connecting rail line. It is best to be on the opposite side of the road, rather than under it. As the monorail turns to the right, look left at that corner. There are several markers. The first two are to commemorate the role of the ROK commandos who made sure that the enemy positions were manned and transmitted any weaknesses to the landing forces. The other monument is at the Red Beach landing point. Of the two, the more significant and larger is of the ROK troops. The base of the monument contains etched photos of the terrain and the first landings in 1950 and of the second landing on 10 February 1951. In the case of this particular monument, the contribution of ROK forces is of greater importance, given how much has been written of the Marine Corps and the landings at Inchon. As a demonstration of how both forces contributed, the monuments are next to one another.

The landings here occurred in the late afternoon, at approximately 1730. It was here that the remainder of the 5th Marines landed at the sea wall, and the famous photograph of Lieutenant Baldamero Lopez leaving the landing craft, vehicle, personnel (LCVP) was taken. Lopez, who was with Company A, was killed not long after the photograph was taken, while pushing the attack.[20] The marker seems somewhat out of place at a bend in the road with no water in sight (the water is now 200 meters beyond, past the factory—a testament to the industrial growth and land reclamation done by the ROK government). By this time, the elements of 3d Battalion who were on Wolmi-do were resupplied and linked up with the rest of the 5th Marines.

1stLt Baldomero Lopez climbs out of the landing vehicle and over the seawall at Red Beach, 15 September 1950, leading Company A, 3d Platoon, 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, in the second assault wave. Lopez was killed in action a few minutes later while assaulting a North Korean bunker.

Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command

The Red Beach assault was carried out in limited daylight and under fire from enemy forces. However, the elements of the 5th Marines came ashore in quick order and started their attack inland to the south. By midnight going into 16 September, Lieutenant Colonel Raymond Murray reported that the high ground of Inchon, including Cemetery Hill and Observatory Hill, were in Marine Corps control.[21] It is from Observatory Hill that one is able to see a clear view of Inchon harbor.

As one then walks toward the Inchon train station, the hill that signifies the Chinatown district of Inchon appears. At this point, there are stairs that lead to the top of the hill in Freedom Park (address: Freedom Park, 1-11 Jungang-dong, Jung-gu, Inchon; GPS 37 degrees, 28’30” N, 126 Degrees, 37’22” E), which gives an even more significant view of the port area. Here one sees the statue of General Douglas MacArthur upon a large pedestal. While the statue of MacArthur is life-size, the base is commanding. This gives the viewer a sense of MacArthur surveying the ground, as well as increasing his importance in the landing. He is both a man and a daring strategist. While his importance may open to debate, this statue conveys a sense of the risks and rewards. It was erected in 1957 to commemorate U.S. and ROK alliances.[22] At the base are further historical markers that signify the daring nature of the landings, the commemoration of the U.S. Navy in the landings, and the role of all combatants under the UN flag. The statue atop Freedom Hill is bronze with granite reliefs at the bottom commemorating all the UN forces that landed at that time.

The Red Beach landing marker. Landings here occurred at 1730.

Photo by Cord Scott

It is here that most of the historical markers for the Marine landing at Inchon are located. There are significant ones past this point, but all markers noted to this point can be reached by walking from location to location in under three hours, and this is at a leisurely pace. This is not to say there are no other significant places for those interested in the landings to see.

South of Inchon Hill

The last of the three landing markers, Blue Beach, is a bit of a struggle to find. As with the Red Beach marker, it is well inland of the sea and could easily be overlooked. To further complicate matters, it sits on a main street next to a gas station, so it is not readily accessible.[23] What is a general benefit of this site is that the original seawall seems to be intact and gives the viewer a perspective of the obstacles to be overcome by the landing forces. This particular beach was where the last of the 1st Marine Division forces, along with elements of the U.S. Army’s 7th Infantry Division landed. Fighting here was not as vicious, but the landings were still dangerous, and the outcome certainly not settled, partially due to the damaged seawall as well as the tidal flats. The 7th Division landed all material here and was operational by 19 September when it established a headquarters in the general area.

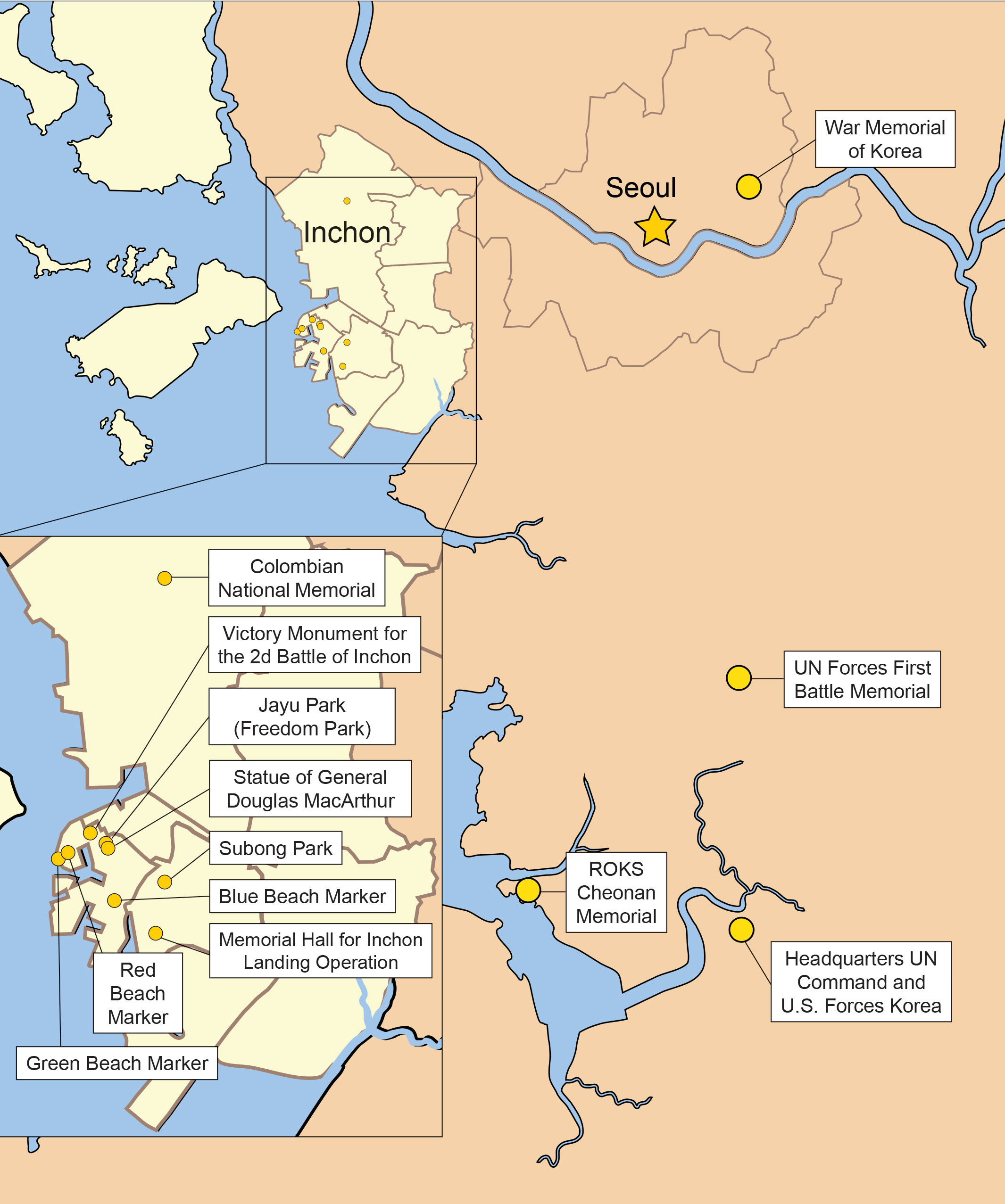

Map of Inchon museums and landing site and memorial markers.

Created by MCUP

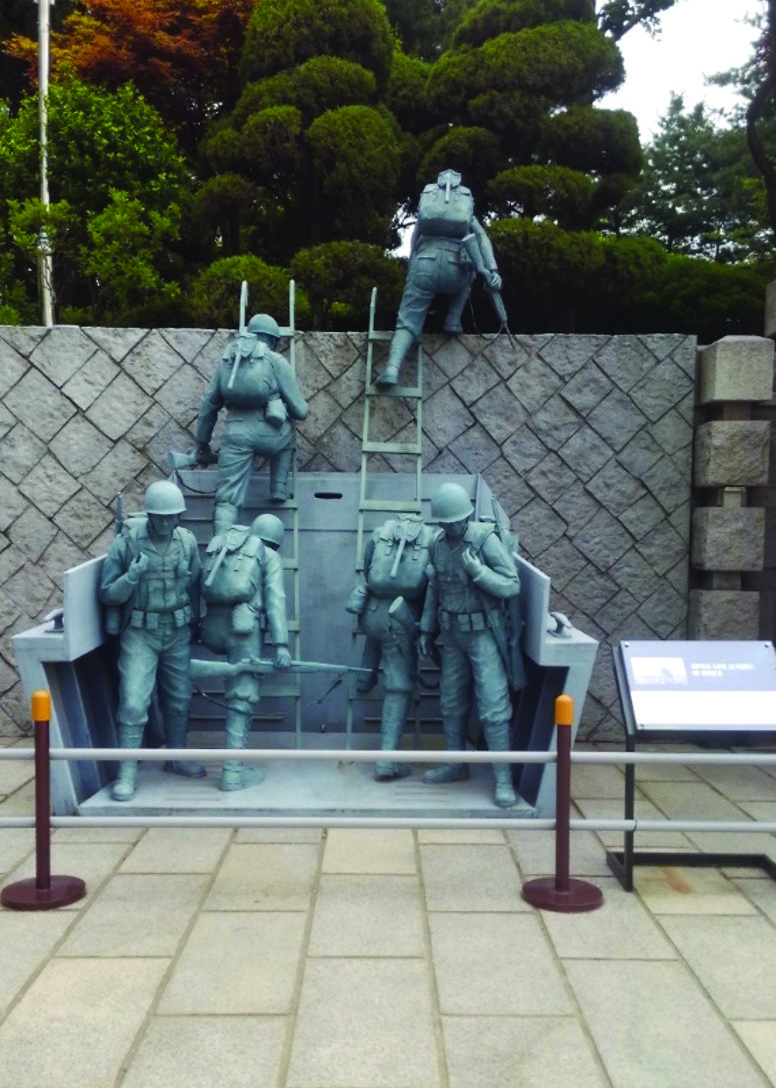

While not near the landing beaches, the pinnacle of the historical impact of the Inchon landings is at the Memorial Hall for Inchon Landing Operation.[24] Located approximately 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) from the beaches (address: 525 Ongnyeon-dong, Yeonsu-gu, Inchon; GPS 37 degrees, 25’ 11” N, 126 degrees, 39’12” E), the museum occupies one of the larger hills in the area. It consists of large outdoor displays of equipment used in the landing, two life-size models—the Lopez picture and a recreation of the Marines atop the Wolmi Observatory—and several commemorative markers to the 1st Marine Division and related units in the area. Inside, there are several rooms displaying objects of the era, 3D models of the harbor, a life-size recreation of MacArthur and his staff watching the landing, and an overlay map that shows where the original landings took place, superimposed on the reclaimed land. There are some testimonials of the combatants, as well as interactive exhibits for younger visitors to the museum.

The Blue Beach landing marker is located adjacent to SK gas station Route 77 and Maesohol-ro.

Photo by Cord Scott

Remnant of the seawall at the Blue Beach landing marker.

Photo by Cord Scott

The outdoor exhibits include an LCVP, a landing craft, mechanized (LCM), a Cessna O-1 Bird Dog observation aircraft, and a variety of artillery pieces, as well as some modern equipment such as U.S. Marine Corps/ROK Marine Corps equipment from the 1980s, such as a landing vehicle, tracked (LVT), and an M47 Patton tank. There is also an additional section on the ROK Marine Corps—considered an elite force within the ROK—inside the museum.

A set of maps at the Memorial Hall for Inchon Landing Operation. The white borders delineate the original islands and shoreline on 15 September 1950, while the shaded area underneath identifies reclaimed land in 2016.

Photo by Cord Scott

The museum offers an overview of the landings in a simple form, and the significance of physical items on display are explained through signage. Inside the museum, the first room displays concern the politics of the conflict and the units involved in the landings, showing examples of the equipment forces used during the battles. Visitors will notice the lack of body armor or other pieces of kit considered essential to modern Marines.

The next set of displays include a large three-dimensional map of the Inchon landing area to clearly demonstrate the scope of the invasion fleet, as well as a two-dimensional map of what the shore looked like in 1950 compared to its current topography. This gives the visitor an idea of how staff rides might have to adapt to the current terrain. A life-size model of General MacArthur (based on a photo of him watching the landings) is also displayed. The use of life-size figures offers the visitor a sense of presence.

A statue of Gen Douglas MacArthur watching the landings from the USS Mount McKinley (AGC 7) at the Memorial Hall for Inchon Landing Operation.

Photo by Cord Scott

Museums catering to both Korean and English speakers may offer limited information due to space restrictions; they are not able to provide a complete picture of the histories they house. These museums and markers serve as a starting point for further academic study into the events of the Inchon landing and should not be taken as definitive history.

Moving onward through the Memorial Hall for Inchon Landing Operation and its grounds, the importance of the materiel used during the landing becomes more apparent. For example, on the grounds, there is a landing craft, vehicle and personnel (LCVP) located on the side of the hill. This gives the viewer a sense of size and the added feature of seeing the terrain on which the Allies fought.

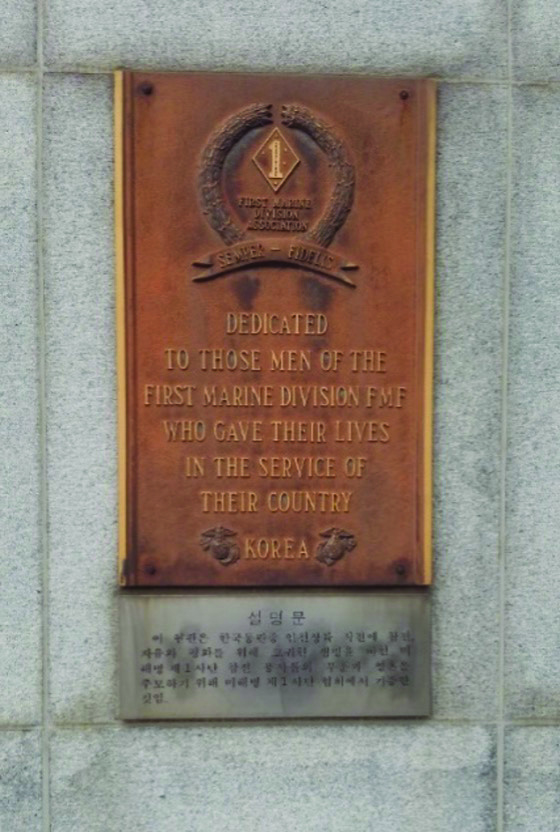

Perhaps the most significant monument on the museum grounds is the statue dedicated to the U.S. and ROK landing forces. The three figures at the base of the monument all look forward—a nod to getting the job done without any sort of emotion. This statue grouping stands in contrast to the one at the entrance to the Korean War Memorial in Seoul, where the figures interact with one another. On the side of the statue is a panel dedicated to the 1st Marine Division for its actions on 15 September and beyond.

A statue and bas relief dedicated to the troops who landed in Inchon on 15 September 1950, located on the grounds of the Memorial Hall for Inchon Landing Operation.

Photo by Cord Scott

Closeup of the plaque dedicated to the 1st Marine Division at the Memorial Hall for Inchon Landing Operation grounds.

Photo by Cord Scott

Secondary Markers and Sites

Another area that may be of interest to those studying the Corps’ wider history is a bit to the north of the Inchon area. Near Gimpo International Airport, one can pick up the bus to Gangwha Island (Gangwhado). On the southeast side of the island, facing the greater Seoul area, is where the Marines landed in 1871, during an uprising against French missionaries. This particular incident is not well known by many non-Koreans, but it has been noted by Marine Corps historians and those studying Korean history of the late 1800s.[25]

Within the Inchon area, there are further markers of note. The Colombian national marker is one of the UN combatant country markers that is located throughout the country. These markers are located near significant battle sites or locations of importance to that country. (412 Gajeong-dong, Seo-gu, Incheon.) Another marker dedicated to the landings is located at Subong Park (address: Subong Park, 55-183 Yonghyeon-dong, Nam-gu, Inchon. 37 deg., 27’28” N, 126, 39’38” E), to the east of Freedom Park. It includes a statue 16 meters in height that is dedicated to those killed during the battle.

The last museum of possible interest in the south of Inchon is the UN Forces First Battle Memorial (address: 742 Gyeonggidaero, Osan, Gyeonggi-do 18112). This museum addresses the landing in part but mostly centers on the battle that brought the United States and the United Nations into the conflict.[26] While this museum may not have any direct connection to the U.S. Marines, it does give an overview of how the first U.S. combatants came to fight in Korea in the early part of July 1950. The museum incorporates several of the same displays as the Memorial Hall for Inchon Landing Operation but also includes the names of the U.S. troops killed during the battle. Visitors may walk up the hill behind the UN museum to where a full-size statue of Lieutenant Colonel Smith stands looking north, toward the approaching North Korean troops.

Landing craft on the grounds of the Memorial Hall for Inchon Landing Operation. The outdoor exhibits are tiered areas going up the hill toward the museum. This allows visitors to experience the greenery of the hill, as well as note the terrain that the combatants faced just past the landing beaches.

Photo by Cord Scott

For the Marines who landed on that first day, the fighting intensified as they pushed toward their first two inland objectives: Army Service Command XXIV Corps (referred to as ASCOM City), a former U.S. Army depot prior to the U.S. Military Advisory Group to Korea force withdrawal, and Gimpo Airfield. ASCOM was seized after stiffened North Korean defense on 17 September, while Gimpo was seized on 18 September.[27] This latter objective was important as it allowed UN aircraft, and more importantly Marine Corps fighters, to land so that they might refuel and rearm before giving close air support to the Marines as they pushed on toward Seoul. To effectively accomplish this, they first had to cross the Han River, which is approximately 400 yards wide at the locations northwest of Seoul as well as in Seoul proper. For a more complete depiction of the battle of Seoul, one might also visit the War Memorial of Korea which is across the street and to the west of Dragon Hill Lodge at U.S. Army Garrison Yongsan-Casey. While the base is no longer active, the resort is maintained by the U.S. military and offers a central location from which to visit sites in the region. The War Memorial of Korea is a museum that is free of charge and gives the history of armed conflict in Korea.

A full-scale statue of the landing of the Marines on Red Beach at the Memorial Hall for Inchon Landing Operation, based on the famous photograph. 1stLt Lopez is depicted at the top of the wall. This statue’s perspective—as if the viewer is a participant disembarking from the back of a landing craft, vehicle, personnel—enables the viewer to imagine themselves at the landing.

Photo by Cord Scott

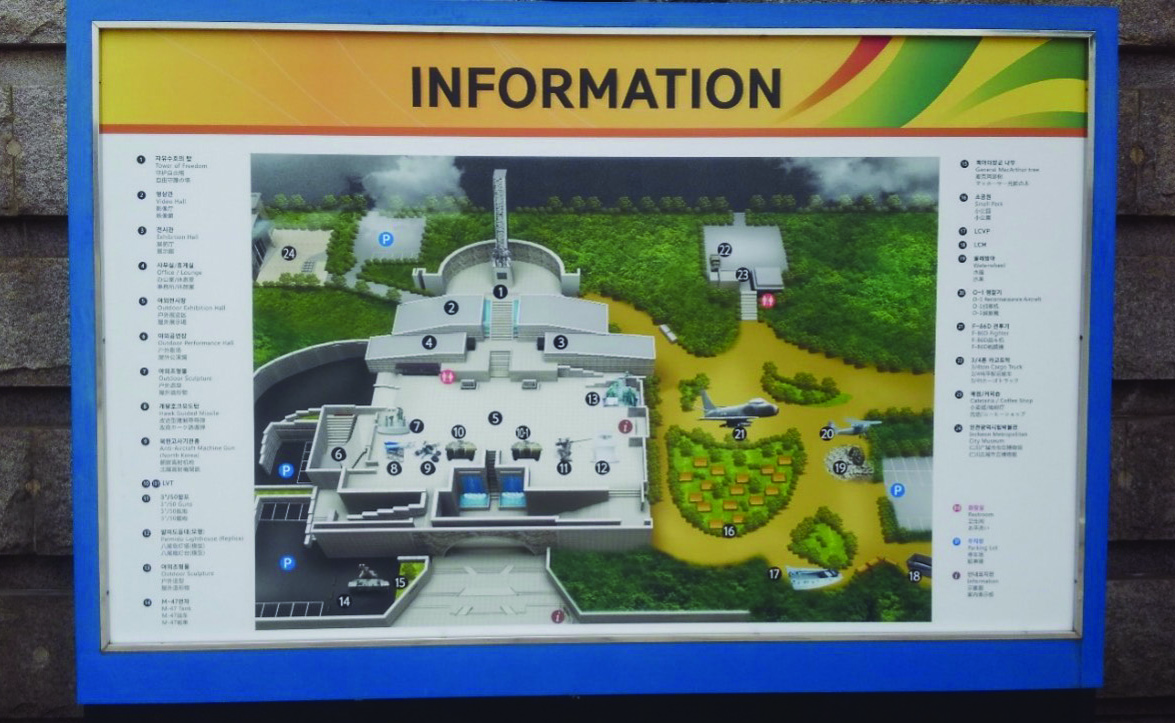

A map of the grounds of the Memorial Hall for Inchon Landing Operation.

Photo by Cord Scott

Finally, The U.S. Marine Corps Forces Korea offices inside the UN headquarters building also have some significant displays of items captured. Now located within the UN Command building at U.S. Army Garrison Humphreys, access is restricted and may not be easily accessible.

Visitors interested in a side trip that demonstrates the nature of the conflict should go to the ROK Navy’s 2d Fleet Command in the Port of Pyeongtaek. This area is approximately 15 kilometers from U.S. Army Garrison Humphreys, but it offers two naval displays of interest. There are two more recent monuments to the continued fighting between North and South Korea: a Chamsuri-class PKM 357 patrol boat, which was attacked near the Northern Limit Line in 2002; and the ROKS Cheonan, a Pohang-class corvette that was blown in two by a mine in 2010 with a loss of 47 sailors. The Cheonan was raised from the ocean floor and now is a permanent memorial on the grounds of the ROK Navy 2d Fleet Command base. To gain access, one only need a Department of Defense common access card (CAC), but to ensure an English translator and guide, arrangements should be made in advance.

Legacy of the U.S. Marine Corps in Korea

While the landings at Inchon were audacious and successful, they comprised only the first part of a long campaign. The fighting in Seoul and its environs went on for another two weeks. Following the battle there, the Marines were withdrawn from the fighting to refit for their next operation, a landing at Wonson, on the eastern side of the DPRK-controlled area.[28] By this phase, the war was progressing quite fast, and when the landings were finally conducted, the U.S. and ROK Armies had secured the area. This was the first part of the People’s Republic of China’s involvement in the war, when Chinese People’s Volunteers entered the war. This ultimately means that viewing any formal markers or commemorations of the battle of the Changjin/Chosin Reservoir and a marker to accommodate enemy forces 75 years later, requiring access to the ground within North Korea, is extremely difficult, if not actually impossible.[29]

For the U.S. Marines, Inchon is a symbol not only of the spirit that embodies the Service but also the fact that they achieved such a challenging task. While the sites do not fully capture the audacity of the land-

ings, the fact that they are preserved says something profound about the sacrifices of the UN forces who carried out the operation. As with any historical site, the gravity of the event may not be fully understood until one is physically at the location. The Inchon landing effectively changed the momentum of the war and remains—along with the determination of those who later fought at Chosin—as a symbol of pride. To walk the grounds where the landings occurred, as well as see some of the history preserved along the way or in the museums in the Inchon area, is something that carries greater significance 75 years later. While many of the markers are simplistic and do not give a full account of the battle, it is a testament that the locations are recognized as a factor in the current success of the Republic of Korea. As more and more of the Korea Marines pass, these memorials and markers will serve as a way to preserve their sacrifices and to deepened understanding of the nature of the battle.

•1775•

Endnotes

[1] While some reports note that the tidal difference may be up to 36 feet, high tide was calculated to measure 31.5 feet on 15 September 1950. BGen Edwin H. Simmons, “Over the Sea Wall: U.S. Marines at Inchon,” in U.S. Marines in the Korean War, ed. Charles R. Smith (Washington, DC: Marine Corps History Division, 2007), 90.

[2] Flying Fish Channel is the name of the sea lanes leading to Inchon port.

[3] Foreign Relations of the United States, Diplomatic Papers: The British Commonwealth, The Far East—1945, vol. 6 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1969), 1039, as cited in Bruce Cummings, Korea’s Place in the Sun: A Modern History (New York: W. W. Norton, 2005), 187.

[4] Korea—1950, CMH Pub 21-1 (Carlisle, PA: U.S. Army Center for Military History, 1997), 6.

[5] Cummings, Korea’s Place in the Sun, 197.

[6] George C. Herring, From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations since 1776 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 640.

[7] Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 641.

[8] Allan R. Millett, The War for Korea, 1950–1951: They Came from the North (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2010,) 135–36.

[9] Map of landing zones in Millett, The War for Korea, 1950–1951, 210.

[10] “71: Into the Fire,” directed by John H. Lee, 2010, IMDb entry, accessed 15 July 2024.

[11] Simmons, “Over the Sea Wall: U.S. Marines at Inchon,” 90.

[12] Millett, The War for Korea, 1950–1951, 209.

[13] Millett, The War for Korea, 1950–1951, 208–11.

[14] Units, About Us, Kunsan Air Base, accessed 15 July 2024.

[15] Simmons, “Over the Sea Wall: U.S. Marines at Inchon,” 90.

[16] Millett, The War for Korea, 1950–1951, 212.

[17] Simmons, “Over the Sea Wall: U.S. Marines at Inchon,” 95.

[18] Simmons, “Over the Sea Wall: U.S. Marines at Inchon,” 91.

[19] Simmons, “Over the Sea Wall: U.S. Marines at Inchon,” 90.

[20] Smith, U.S. Marines in the Korean War, 110–11.

[21] Lynn Montrose and Capt Nicholas A. Canzona, The Inchon-Seoul Operation, vol. 2, U.S. Marine Operations in Korea, 1950–1953 (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1955), 97–113.

[22] Suhi Choi, Embattled Memories: Contested Meanings in Korean War Memorials (Reno: University of Nevada Press, 2014), 64–65.

[23] When looking for this marker, the author drove past it three times and only saw it while stopped at a traffic light, when he was finally able to access it from the gas station parking lot.

[24] Homepage, Memorial Hall for Inchon Landing Operation, accessed 22 April 2025.

[25] David McCormick, “The First Korean Conflict,” Naval History 31, no. 2 (April 2017).

[26] Exhibitions, UN Forces First Battle Memorial, accessed 23 July 2024; and “Task Force Smith Memorial,” Osan, American War Memorials Overseas, accessed 23 July 2024.

[27] Simmons, “Over the Sea Wall: U.S. Marines at Inchon,” 124–26.

[28] Joseph H. Alexander, “Battle of the Barricades: U.S. Marines in the recapture of Seoul,” in Smith, U.S. Marines in the Korean War, 192–94.

[29] The author exchanged emails with Col Warren Weidhahn (Ret), president of the Chosin Few Association, who noted that a very small contingent of veterans was given entry into the DPRK in the late 1990s to go to the site, but they were constantly under DPRK observation.

About the Author

Dr. Cord A. Scott is an overseas collegiate faculty for the University of Maryland Global Campus in Asia. He teaches history, government, and humanities with a specific focus on film. He has written extensively on a variety of topics concerning popular culture, with two of his books centered on military comics in World War II. He is the author of The Mud and the Mirth: Marine Cartoonists in World War I (2022) and the forthcoming They Were Chosin: U.S. Marine Cartoonists in the Korean War (forthcoming 2025).

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7957-0871