PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: One of the U.S. Marine Corps’ most resourceful opponents in World War I has received curiously little attention in historical accounts: Major Josef Bischoff, commander of the 461st Infantry Regiment, who led German forces against Marines at Belleau Wood. This article offers a much-needed biography of the only German tactical leader at Belleau Wood mentioned by name in various accounts of the battle.

Keywords: Major Josef Bischoff, 461st Infantry Regiment, Battle of Belleau Wood, World War I

Since its inception in 1775, the U.S. Marine Corps has battled many enemies. These opponents have varied in skills and tactics, from the rural Nicaraguan nationalist bandit César Augusto Sandino to professional soldiers such as Japanese General Tadamichi Kuribayashi. Each time, Marines were faced with overcoming significant obstacles that were the direct result of the effective use of tactics and terrain by enemy leaders. While much has been written about some of these well-known opponents, one particularly resourceful enemy commander has received little recognition. This is more remarkable when you consider that various accounts of the Battle of Belleau Wood mention only one German tactical leader by name: Major Josef Bischoff, commander of the 461st Infantry Regiment. Little is known about the commander who defended Belleau Wood for most of the month of June 1918, and yet he was a remarkable figure whose influence spanned military and political spheres. This article attempts to provide a much-needed biography of Bischoff.

The effectiveness of Bischoff’s tactical disposition at Belleau Wood can be gleaned from two semiofficial accounts of the war that contain references to him and his masterful defense. Colonel John Thomason’s 1928 authoritative classic on the U.S. Army’s 2d Division at Château Thierry, based on his research in the German archives, provides a unique vignette of Major Bischoff. According to Thomason, Bischoff was “an old West African soldier, who had learned the art of bush-fighting in the German colonies. His infantry positions were everywhere stiffened by machine guns and minenwerfers [mortars], and his dispositions took full advantage of the great natural defensive strength of the woods.”[1]

An unofficial 2d Division history published by the Second Division Association in 1937 notes: “[The 461st Infantry Regiment’s] commander was Major Bischoff, an old colonial soldier who had seen much tough fighting in Africa.”[2] Later, the history comments on the effect of the German defense on Major Berton W. Sibley’s 3d Battalion, 6th Marines, on 8 June 1918: “Major Bischoff’s machine guns were skillfully placed, and as soon as one was taken another took the captor in flank.”[3] His accomplishments at Belleau Wood were the result of a lifetime of soldiering that shaped him into a formidable opponent.

Josef Maximillian Johan Bischoff was born on 14 July 1872 at Langenbrück, Upper Silesia, Prussia (now Poland). His parents were Joseph Bischoff (1833–1910), a prominent mill owner, and Agnes Saluz (1846–1912).[4] With the Bischoff family being affluent, Josef Bischoff was able to receive an officer candidate appointment in the Prussian Army and joined the Infantry Regiment Keith (1st Upper Silesian) No. 22 in Silesia in January 1892.[5] He received a commission as a second lieutenant on 16 March 1893.[6]

On 9 March 1898, he joined the Schutztruppe or Imperial Protectorate Force in German East Africa. The Schutztruppe were the colonial armed forces of the German Empire and was made up of German officers and noncommissioned officers with local recruits.[7] The officers selected for service in the Schutztruppe were considered the cream of those eligible.[8] This overseas force earned a remarkable but notorious reputation during years of continuous colonial warfare from 1889 to 1911. To their credit, they were able to take the local recruits and create “soldiers who were respected and feared far beyond the boundaries of the colony.”[9]

With the valuable experience gained in East Africa, Lieutenant Bischoff returned to Germany on 16 June 1901.[10] He then returned to Africa in March 1904 when members of his unit, the 3d Company, 22d Infantry Regiment, were transferred to German Southwest Africa (now Namibia) for service in the infamous German-Herero conflict. He served as the adjutant, 2d Battalion, 1st Field Regiment.[11] During the summer campaign, he was wounded in the left foot during a skirmish at Omatupa village in the Omuramba region on 15 August while providing his commander, Major Herman von der Heyde, key information during the battle that may have saved the major’s life.[12] For his quick thinking and initiative under fire, traits that would serve him well in the next war, First Lieutenant Bischoff was awarded the Order of the Red Eagle 4th Class, with swords, on 30 July 1906.[13] The regimental history recounting this award notes that Bischoff had been awarded previously the Royal Order of the Crown, 4th Class, with swords.[14] The circumstances of that award are unknown. As noted in the 22d Regiment’s history:

When he saw how his commander was in a spot that was especially exposed to enemy bullets, Bischoff took it as his duty to hurry to him and make him aware of the danger. Major von der Heyde subsequently changed his position. Because Lieutenant Bischoff still found himself in the old precarious spot, an enemy bullet struck him in the right foot, which incapacitated him for action for a long time. Thus, through his vigilance and boldness, he saved his commander from being wounded, perhaps even from a sure death; unfortunately, however, he had to pay for his bravery with a serious wound, from which he thankfully recovered after months of recovery. Near the end of the campaign, he received the Order of the Red Eagle 4th Class with swords.[15]

After convalescence, Bischoff returned to duty during the Hottentot Uprising and eventually served as a troop leader during the Nama War in 1906.[16] The Herero and Nama Wars are known today as examples of brutal colonial repression and ethnic cleansing amounting to extermination.[17]

Returning to Germany in January 1909, Bischoff became a company commander in the 112th Infantry Regiment effective 1 February.[18] In 1911, he became a company commander in the 166th (Hessen-Homburg) Infantry Regiment. Bischoff was promoted to major on 1 October 1913.[19]

As the European nations plunged into war in 1914, many German career soldiers were selected to serve in reserve infantry regiments.[20] Bischoff was appointed to command the III Battalion, 60th Reserve Infantry Regiment, at its mobilization on 2 August.[21] This was a common occurrence in the German Army in 1914 by which career officers and noncommissioned officers were assigned to reserve units to facilitate the reservists’ transition to active service.[22] Composed of reservists equally from the Rhineland and Alsace-Lorraine, the 60th Reserve Infantry Regiment was part originally of the 60th Bavarian Reserve Infantry Brigade, 30th Bavarian Reserve Infantry Division, XIV Reserve Corps, Seventh Army, serving as part of the Strasburg Garrison in border defense on the eastern frontier between France and Germany.[23] That assignment changed with the successful French attack through the Vosges region on 14 August 1914, forcing a German withdrawal.

On 17 August, the 60th Reserve Infantry Regiment began its preparation for the Battle of Lorraine in the rugged forested Vosges region of eastern France. As noted in American Armies and Battlefields in Europe:

The rugged terrain in the Vosges Mountains, north of the Swiss border, was a serious obstacle to major operations in that region because of the difficulty of maneuvering and supplying any considerable number of troops during an advance. South of these mountains near the town of Belfort . . . the narrowness of the pass between the mountains and the Swiss border, called the Belfort Gap, made the region not suitable for large-scale operations.[24]

There were many lessons to be learned as German second- and third-line troops untutored in mountain warfare were challenged by well-prepared and experienced French mountain troops. Lacking high trajectory artillery guns needed for successful operations in the region, the German forces were initially at a distinct disadvantage.[25] They continued to struggle until sufficient artillery units arrived to support the infantry. In the meantime, Bischoff surely honed his skills at small unit tactics with the emphasis on command and control and persistence in the harsh environment. The lessons he learned here would pay off when he met the Americans in the rugged terrain of Belleau Wood in June 1918.

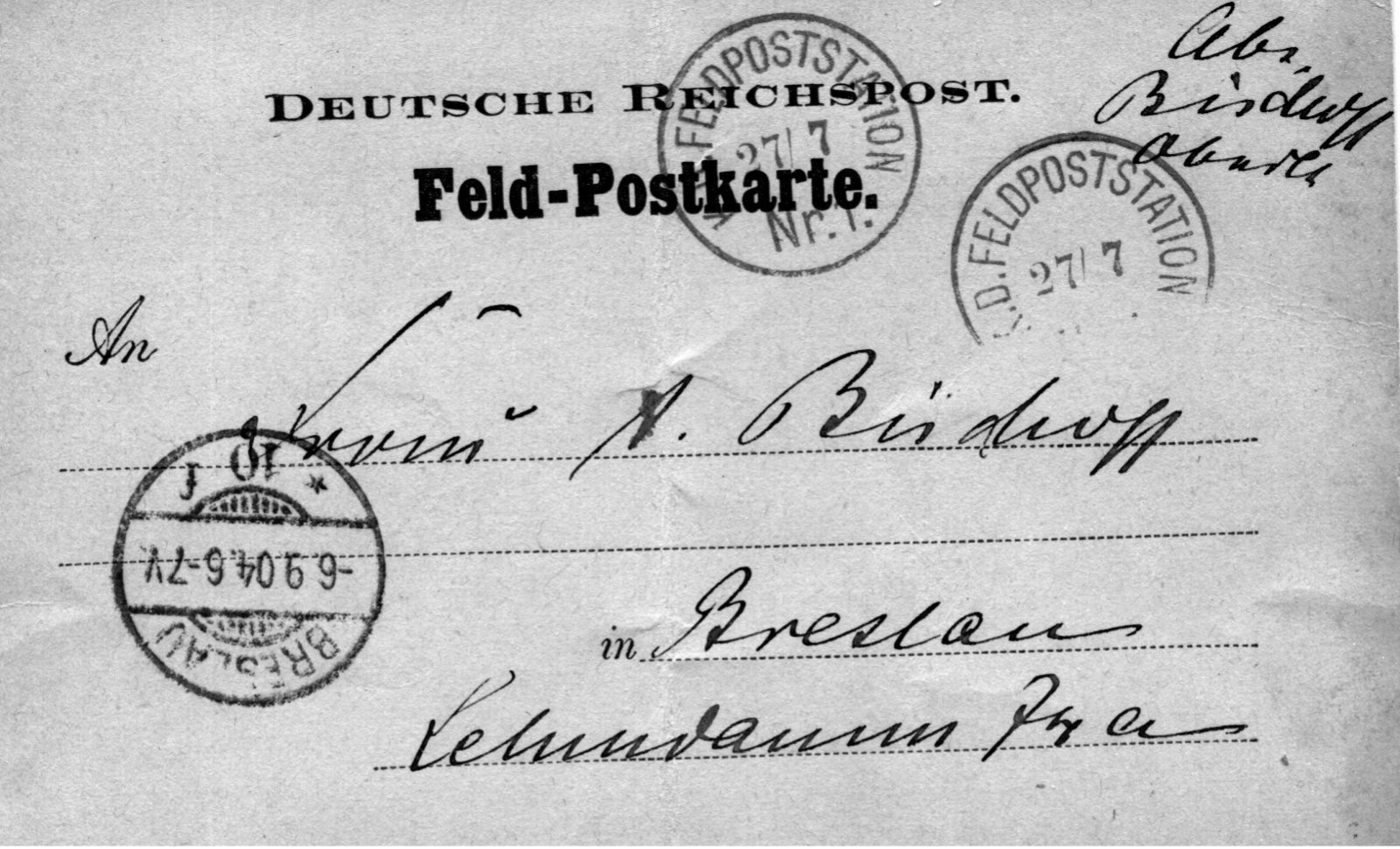

A postcard (front and back) Bischoff wrote to his mother, sent 27 July 1904, from Okahandja, Namibia, thanking her for birthday wishes, telling her he was doing fine, and that he was happy.

Courtesy of personal collection of George Malick, San Jose, Costa Rica

For the next two weeks, the regiment deployed to several locations as part of the general German counterattack. Having deployed to an area known as the Casino Heights near Schellstadt (now Sélestat), Bischoff and III Battalion’s baptism of fire was quick and severe.[26] On 15 August, the battalion received a heavy artillery barrage causing the entire unit to withdraw. The German Sixth Army in coordination with the Seventh Army finally responded to the French attack by commencing their counterattack on 18 August, which began the Battle of Lothringen (18–25 August 1914), driving the French forces back.[27]

On 19 August, the III Battalion was directed to positions on the Dangolsheimer Ridge, where it stayed until 22 August.[28] From its subsequent position at Sulzbad, east of Strasbourg, Bischoff’s battalion was sent to support the 42 Infantry Brigade in the mountainous region of Schirmeck. After arriving, it relieved a battalion from the 120th Infantry Regiment and “cleaned the battlefield.” This unfortunate and unpleasant task involved the burial of 161 of their countrymen and 388 French soldiers.[29] On 26 August 1914, the 60th Reserve Infantry Regiment was sent to Château-Salins by rail to join the Landwehr Infantry Regiment 82 forming the new 10th Bavarian Reserve Infantry Brigade (to be known as Brigade Ipfelkofer).[30] By 28 August, the brigade composition was completed and it was placed under the operational control of the 30th Bavarian Reserve Infantry Division commander.[31]

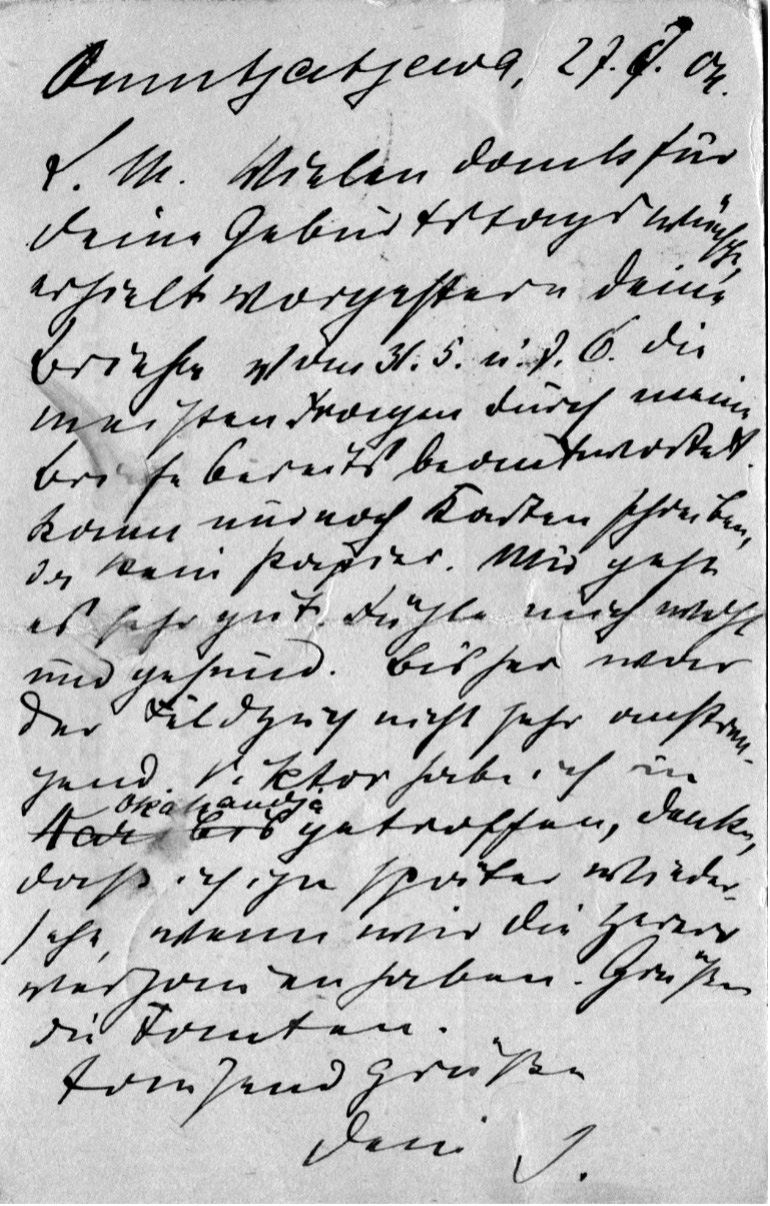

Officers of the Reserve Infantry Regiment 60, 1915.

MajGen Frederich Zechlin, Das Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 60 im Weltkrieg [The 60th Reserve Infantry Regiment in the World War] (Oldenberg: Berlin, 1926), 63

For the next week, the regiment took advantage of being relieved from the front and engaged in battalion and regimental exercises.[32] During the period of 6–10 September, the regiment in Lanfroicourt provided support for a XIV Reserve Corps attack by conducting probing reconnaissance patrols around Moivrons and Villers. The regiment relieved the Landwehr Regiment 17 at Delme on 11 September with Bischoff’s III Battalion stationed as an outpost unit in Lemoncourt.[33]

As the 30th Bavarian Reserve Infantry Division moved to consolidate its position at the Delmer Ridge on 13 September, it was attacked by strong French forces in what became known as the Battle of Aulnois. In response to the grave situation, Major Bischoff detached elements of two companies to move to the sound of the battle as reinforcements for the rest of the division that was engaged close to Aulnois.[34] Following this engagement, Bischoff and eight other soldiers received the battalion’s first Eisernes Kreuz (Iron Cross) medals on 5 October 1914.[35]

As the weather cooled in late 1914, operations in Lorraine were reduced as both sides realized the rugged terrain significantly limited the potential success of winter military operations. The war’s focus shifted farther to the west in France. The division was transferred to the Somme region near Sainte-Quentin in September, where it remained for the rest of 1914.[36] Taking the opportunity to reorganize, Brigade Ipfelkofer was renamed the 61st Infantry Brigade on 2 December 1914.[37] The period from January to March 1915 was relatively quiet.

On 17 May 1915, the 60th Reserve Infantry Regiment became part of 13th Landwehr Infantry Division in line on a quiet sector of the Lorraine Front and participated in defensive operations.[38] The regiment also spent the month completing some needed tactical training, receiving 110 replacements, and conducting aggressive patrolling against the French outposts.[39] By end of June 1915, 60th Reserve Infantry Regiment was replaced by 82d Landwehr Infantry Regiment and assigned to the 5th Bavarian Landwehr Brigade of the 1st Bavarian Landwehr Infantry Division.[40]

Remaining a reserve unit, the regiment spent its time improving positions about 5 kilometers southwest of Avricourt (about 30 kilometers due east of Nancy), working mostly at night due to French harassing artillery fire. The combat activity of the regiment increased in July 1915 as units were sent piecemeal to various hot spots. Then, the Army High Command issued orders to assault several positions on key terrain in a wooded area known to the Germans as the Sachsenwald (Saxon Wood) southeast of Leintrey on 15 July 1915.[41] Given the task of taking this critical terrain feature, the regiment suffered heavy casualties in an unsuccessful attempt. The regimental history notes that 8 officers and 40 soldiers were killed in action and 2 officers and 118 soldiers were wounded.[42]

Later, during intense combat near Lorquin (9.6 kilometers southwest of Sarrebourg) on 23 July 1915, Bischoff’s III Battalion distinguished itself by repulsing the main French attack. Major Bischoff was awarded the Iron Cross, First Class on 4 August 1915, for his resolute leadership under fire.[43] As the summer ended, the regiment was finally back together as a unit on 6 September 1915 after weeks of Army reserve duty, the misery of static warfare, and constant patrolling. However, between 27 and 30 September, patrolling increased dramatically in front of the regiment to provide early warning of an enemy build-up in anticipation of a new offensive.[44] As a result, the Army High Command was still focused on the Saxon Wood, which continued to be an area of particular importance as it provided excellent positions for artillery forward observers.

On 4 October 1915, attack preparations began with rehearsals, which were conducted on similar terrain the following two days.[45] The attack force consisted of Bischoff’s battalion, two platoons from the 60th Machine Gun Company, 2d Battalion, of the 122d Landwehr Infantry Regiment, and Engineer Company 8. The attack force’s approach march early on 8 October to its attack positions used previously identified routes that provided excellent concealment from the French positions. Formed into three attack columns, the force was arrayed with Captain Niethammer (122d Landwehr Infantry Regiment) leading the 12th Company, 60th Reserve Infantry Regiment, the 6th Company, 122d Landwehr Infantry Regiment, and one platoon from the machine gun company on the right. The middle column was led by Lieutenant Colonel Vohwinkel, the 2d Battalion, 122d Landwehr Infantry Regiment, commander, with the 5th and 7th Companies, 122d Landwehr Infantry Regiment. Major Bischoff commanded the left column consisting of his 10th and 11th Companies, with one platoon from the machine gun company. Each column was supported by four engineer squads and an artillery liaison team.[46]

A postcard showing the enlisted leadership of 11 Company, 3d Battalion, RIR 60, March 1916.

Author's collection

In preparation of the attack, the Germans conducted an artillery barrage for two hours beginning at 1430 to breach the obstacles in front of the objective. The attack commenced at 1720. The approach by Bischoff’s column had the easiest effort due to the use of the Gondrexon Creek. The low ground in the creek bed enabled him to move onto favorable ground 1,100 meters from the French position in front of Reillon to the southwest. After heavy fighting that resulted in 26 killed in action and 153 wounded, the objectives were taken and the units prepared for a counterattack. The French obliged them with an unsuccessful assault at midnight. During a lull in the fighting at 0430 the next morning, Bischoff’s III Battalion was relieved and became the 13th Bavarian Landwehr Infantry Division reserve in Avricourt.[47]

With its status as the brigade reserve, the III Battalion was able to rest and recover despite the rest of the regiment returning to combat shortly thereafter. However, Bischoff’s time in the rear quickly came to an end when intelligence reports arrived that reported the French were massing to take back the Saxon Wood position. On 15 October at 0800, the attack began with an artillery and trench mortar barrage. With the timely arrival of reinforcements, disaster was averted. Bischoff quickly deployed the reinforced 11th Company that participated in strenuous combat all day. Although the French attackers suffered heavy casualties, they were unable to recover the ground taken originally on 8 October. Due to the heavy artillery fire and close combat, when the fighting had stopped on 18 October, the Saxon Wood was devastated.[48]

Due to their leadership during October while serving with the Bavarian Brigade, Colonel Friedrich Zechlin and Major Bischoff received coveted Bavarian military decorations for bravery, although they were both Prussian. Zechlin received the Bavarian Military Merit Order, 3d Class, with crown and swords. Bischoff was awarded the 4th Class Order, with crown and swords, on 28 November 1915.[49] The remaining months of 1915 saw the struggle on the western front settle into stagnant trench warfare as winter approached. The regiment retired to winter quarters near Avricourt for the rest of the year.[50]

At the end of January 1916, the German High Command became alarmed about the enemy advantage in men and material on the western front. It then decided to begin a campaign against Verdun with attrition warfare. To mask the preparations for the offensive, a series of screening operations in January and February were directed. The 60th Reserve Infantry Regiment participated in those operations in eastern France until it left for a training area in late February. At the beginning of March, the regiment went back to the front and monotonous trench warfare.[51]

While in the trenches, word reached the regiment that Major Bischoff was leaving. He had volunteered to be a member of the first Pasha Expedition (Pasha I) for service in the Middle East.[52] Sensing an opportunity after the Allied disaster at Gallipoli and the withdrawal from the peninsula in early 1916, the German High Command wanted to transfer troops to the Middle East for the first time to support a second attempt to take the Suez Canal.[53]

Bischoff was a likely candidate probably in large measure due to his prior service in Africa and obvious exemplary conduct in France. However, his file in the Reich Finance Ministry concerning later pension entitlements contains Bischoff’s personal account of his medical history, which included contracting malaria in East Africa. According to his account, the Armee-Abteilung Falkenhausen’s senior medical officer recommended that Bischoff volunteer for the Palestine operation (Pasha I) due to the dry climate in the Middle East in view of his chronic respiratory illness.[54] His departure from the regiment on 18 March must have been a difficult scene, as “he was always an example to his III Battalion of loyalty, duty and bravery and had distinguished himself through tireless care for the welfare of his subordinates and had earned their respect and trust to a high degree.”[55]

Leaving Berlin on 29 March 29, the Pasha I force finally arrived at Beersheba in Palestine on 2 June after a long and exhausting journey that was reportedly like taking the famous Orient Express to Istanbul.[56] The Pasha I force included German machine gun, artillery, aviation, and technical formations with its ally, Austria-Hungary, providing a mountain howitzer detachment.[57] These units were intended to support the Sinai Expeditionary Corps of the Turkish 4th Army, commanded by German lieutenant colonel Freiherr Kress von Kressenstein, appointed a colonel in the Ottoman Army.[58] Presumably due to his experience in Southwest Africa, Major Bischoff was appointed a lieutenant colonel in the Ottoman Army and the commander of the 1st Turkish Camel Regiment.[59]

Colonel Kressenstein’s Suez campaign began on the evening of 16 July 1916, when the vanguard, consisting of three battalions, three machine gun companies, three artillery batteries, three pioneer companies, and several supply columns, was finally able to advance against the canal from al-Arish, Egypt.[60] The corps consisted of three columns of approximately 16,000 troops heading toward Romani. The northernmost column followed the coastal road and the southernmost one marched through Um Bayud. The main body concentrated on Bir Katia while Bischoff and his camel regiment were directed to go farther south through the Magara Mountains, with the order to demonstrate against Ismailia.

After a difficult and exhausting march, Kressenstein decided to attack on 4 August, despite being challenged by supply shortages. He felt he could not turn back without at least attempting to defeat the English force.[61] He decided the focus of the attack would be against the south flank of the enemy at Romani. Part of his 3d Division, supported by heavy artillery, attacked the main enemy position on 4 August at dawn. The larger part of the Turkish infantry and the German machine gun units were assigned to bypass and catch the enemy’s right wing from the south. But the movement was delayed. This caused them to begin in broad daylight rather than in darkness, and the element of surprise was lost. Instead of surrounding the enemy, the left Turkish wing was surrounded by the enemy’s strong mounted forces that evening. Capturing two Turkish battalions and a battery, the British force threatened the now-exposed and weakened Turkish flanks from the direction of el-Qantara, Lebanon. As the battle unfolded, Kressenstein regretted the decision to send Bischoff so far to the south that effectively prevented his camel regiment from influencing the English counterattack.[62] Finally, Kressenstein decided to retreat on the night of 5 August and proceeded in the following days to el-Arish. The withdrawal was harassed by continuous fighting with the pursuing British force.[63]

Thus, this second attempt to close the Sinai Canal ended with the Allied repulse of the Sinai Expeditionary Corps at the Battle of Romani on 3–4 August 1916. The defeat of Kressenstein’s troops forced them to retreat toward Gaza on 14 August, and any subsequent attempts to take the canal were abandoned. Subsequently moving into Palestine to reconstitute, the German contingent spent some weeks recovering from the arduous expedition. During this period, many German troops returned to Germany for rehabilitation. Bischoff returned to Germany in October 1916 and was assigned to the replacement battalion of his old unit, the 60th Reserve Infantry Regiment.[64] In honor of his performance in the Sinai and Palestine, Bischoff was awarded sometime that fall the Ottoman War Medal for gallantry, referred to by the Germans as the Eiserne Halbmond or Iron Crescent Moon.[65]

The Camel Corps at Beersheba, 1915. Bischoff’s camel regiment would have looked like this.

Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LCCN 2007675298

On 2 January 1917, Major Bischoff was appointed commander of the newly established 461st Infantry Regiment, 237th Infantry Division.[66] Seasoned veterans were needed to get this division ready for combat as it contained young recruits and “returned sick and wounded and men taken from the front.” The division was transferred for occupation duty to Galicia shortly after its creation.[67] Bischoff quickly gained the highest reputation among superiors and subordinates. Standing out as a capable officer in the static warfare in Galicia (now western Ukraine), Major Bischoff was later able to prove his splendid soldierly ability during the important counterattacks in East Galicia in July 1917. His division commander, General von Jacobi, named him the “Bravest of the Brave,” based on Napoléon’s famous description of his commander, Marshal Michel Ney.[68]

After arrival in theater, the 237th Infantry Division joined Army Group Woyrsch in early March and later participated in the static warfare in the area near Brzezany between 8 April and 26 June 1917.[69] Due to an anticipated Russian offensive, the division moved closer to be in support as part of the Austro-Hungarian 2d Army on 1 July 1917.[70] On the same day, the Eleventh and Seventh Russian Armies began an attack across the front at the direction of Alexander Kerensky, minister of war in the Provisional Russian Government, in what became known as the Kerensky Offensive.[71] Between 30 June and 6 July, Bischoff and his 461st Infantry Regiment fought in the battles east of Zloczow (now Zolochiv, Ukraine) in recovering lost territory initially taken by the Russians.[72]

The officers of the 461st Infantry Regiment in Russia, 1917.

Author's collection

After initial successes against the combined German and Austro-Hungarian forces, the Russian “gains were modest and bought at huge cost.”[73] Coupled with a significant malaise within the ranks and with severely strained logistics support, the Russians were easy targets for the major counterattack that began on 19 July. A key aspect of the attack was spearheaded by General von Winckler’s Abschnitt Zloczow that contained Corps Wilhelmi to which the 461st Infantry Regiment, 237th Infantry Division, was attached.[74]

The mission of Abschnitt Zloczow was to force a crossing at the Sereth River after breaking through Zloczow to pursue the Russians, probably retreating southward.[75] The 237th Infantry Division was able to seize the bridgehead across the Sereth River in large measure due to the “dashing approach” of 461st Infantry Regiment and its successful holding the crossing for follow-on forces. This is when Bischoff “showed . . . excellent leadership of the I.R. 461 as its assault has ‘his fingerprints’ all over it.”[76] Likely, the veteran Bischoff recognized the significance of the bridge and led his troops in spirited offensive action to take the high ground on the east bank, thereby securing the crossing for the rest of the attacking force.

Bischoff with regimental staff in Russia, 1917.

Author's collection

The battle continued as the counterattack with Corps Wilheimi pursued a disintegrating Russian Army.[77] By 2 August, Army Group South, to which the 237th Infantry Division now belonged, settled into static positional warfare. Following the failure of the Russian minster of war Aleksandr Kerensky’s June Offensive, the Russian Army basically disintegrated, and conditions were ripe for the Bolshevik Revolution, which gained momentum and eventually took power in November. A result of the key role played by his regiment under this leadership, Bischoff was awarded with the Royal House Order of Hohenzollern Knight’s Cross, with swords, on 20 October 1917.[78] This decoration had become an intermediate award between the Iron Cross, 1st Class, and the Pour le Mérite for Prussian junior officers.[79]

Recognizing the dire military situation, the new Russian leadership proposed a ceasefire on 26 November 1917, which led to negotiations at Brest-Litovsk beginning on 3 December. With the conclusion of the Brest-Litovsk Agreement on 8 February 1918, the state of war between Germany/Austria-Hungary and Russia ended. This permitted the Germans to move a large force back to the western front with the objective of ending the war on their terms. In anticipation of a favorable result of the negotiations, Bischoff’s regiment, which had been on occupation duty, had already begun its journey back to the western front on 17 December 1917.[80]

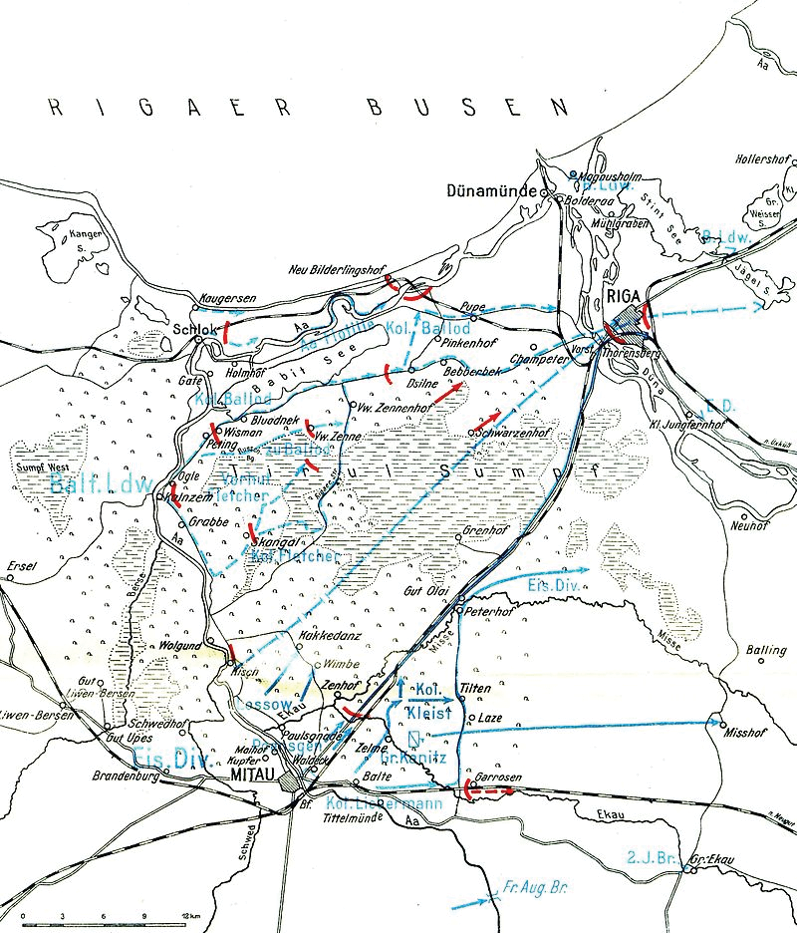

German deployment, IV Reserve Corps, west of Château-Thierry, Operation Blucher, early June 1918.

Reich Archives, Schlacten des Weltkreiges, vol. 32, Map Supplement No. 2

Arriving back in France on 12 January 1918, the 237th Infantry Division settled in a cantonment near Verdun. In mid-May, as the German Army began preparations for Operation Blucher, the third of its offensives seeking to end the war, the 461st Infantry Regiment began to move closer to the Marne as part of Corps Conta (IV Reserve Corps), German 7th Army. When the battle began on 27 May, the Germans overran the French and British units from the Chemin des Dames to the Marne and threatened to continue all the way to Paris. Following the initial success, the 237th Infantry Division, following in trace, joined the offensive and arrived in the vicinity of Belleau Wood on 1 June 1918.[81]

Deploying in opposition to this German offensive was the American 4th Brigade (Marine), consisting of the 5th and 6th Marine Regiments, as part of the U.S. Army’s 2d Infantry Division. Created by the Marine Corps in 1917 following the American declaration of war, these regiments were comprised of long-serving professional Marine officers and staff noncommissioned officers and enlisted men who were mostly new recruits. The first battalion of the 5th Regiment arrived in France on 27 June 1917, and by 3 July the entire regiment was assembled on French soil.[82] The last battalion of the 6th Regiment did not join the American Expeditionary Force until 6 February 1918.[83] Although the 4th Brigade headquarters had been established in October 1917, it was not until 10 February 1918, that the brigade was fully formed in the training area at Bourmont, France.[84]

The 2d Division went to the trenches on 13 March 1918, in a so-called quiet sector southeast of Verdun for frontline training.[85] From 17 to 30 March, elements participated in the occupation of sectors on the west face of the Saint-Mihiel salient. The division continued its service at the front until 9–16 May when relieved to conduct further training.[86] On 18 May, it was assigned to the French Group of Armies of the Reserve. As a result of the German offensive on 27 May 1918, the brigade’s scheduled Decoration Day (now known as Memorial Day) festivities were cancelled. The division was placed at the disposal of the French 6th Army on 31 May by American Expeditionary Forces commander General John J. Pershing and was directed to the French XXI Corps sector near Château-Thierry to assist in the Aisne defensive.[87] As a result, the Marines were on the road to Belleau Wood.

The 4th Brigade deployed to the north of the Paris-Metz Highway northwest of Château Thierry as French units passed through them to the rear. In front of the Marines was a heavily wooded former hunting preserve known as Belleau Wood. Unknown to the Allies, the German offensive ran out of steam on 4 June due to physical exhaustion and lack of supplies. To consolidate their gains and prepare for subsequent operations on 7 June to secure the Paris–Metz Highway, the Germans selected Belleau Wood as a key area to occupy because it presented an excellent advanced position to cover avenues of approach for follow-on forces. Thus, elements of the German 237th Infantry Division that had invested the woods on 3 June, unbeknownst to the Allies, became the focal point of the German defense.[88]

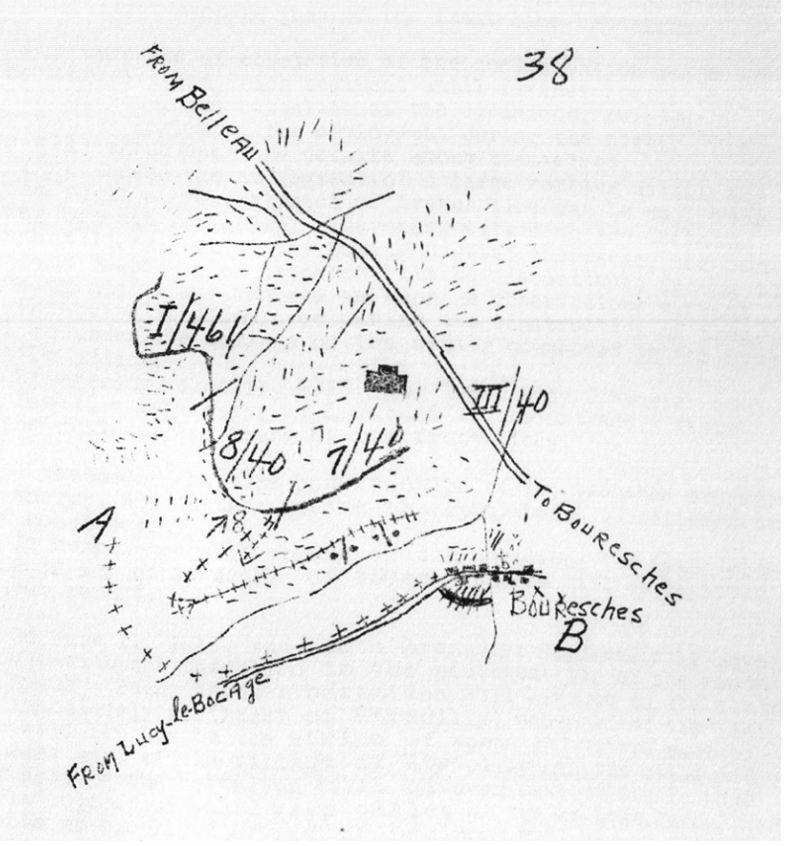

The primary responsibility for German defense of Belleau Wood was given to Major Bischoff’s 461st Infantry Regiment. He set to work immediately preparing defensive positions in-depth anchored by machine guns with interlocking fields of fire dividing the woods into two battalion sectors. As noted in Bischoff’s map in the war diaries, Major Hans von Hartlieb’s I Battalion was placed in the northern sector and Captain Kluge’s III Battalion defended the southern portion.[89] Exhibiting a masterful use of the terrain and natural features, such as rock formations and heavy vegetation, Major Bischoff’s efforts resulted in a virtual fortress surrounded by a sea of wheat.

Bischoff took advantage of the existing terrain and the evolution of German operational doctrine as it related to the tactical defense. By 1918, the German Army understood the importance of depth in the battlespace and the need to engage the enemy throughout its entirety, not just at the forward edge of the battlefield. As noted in Timothy T. Lupfer’s Leavenworth Papers monograph:

In their new tactical doctrine, the Germans avoided excessive emphasis on the struggle at the forward edge, where forces initially collided. The defensive principles discarded the rigid belief that the defended space must remain inviolate. The enemy attack penetrated the defended space, but the depth of the battlefield weakened the attacking force, preserved the defender, and enhanced the defender’s success of retaliation through counterattack.[90]

Thus, Bischoff prepared Belleau Wood defenses with the understanding that penetrations would take place. However, when they did, the enemy would be subjected to immediate and violent attack from the flanks. Lupfer notes:

In their offensive principles, the Germans did not aspire to achieve total destruction at the thin area of initial contact; they used firepower and maneuver in a complementary fashion to strike suddenly at the entire enemy organization. The offensive and defensive principles did not regard the enemy as an impediment or irritant to the methodical seizure or holding of terrain. The enemy force was the fundamental objective.[91]

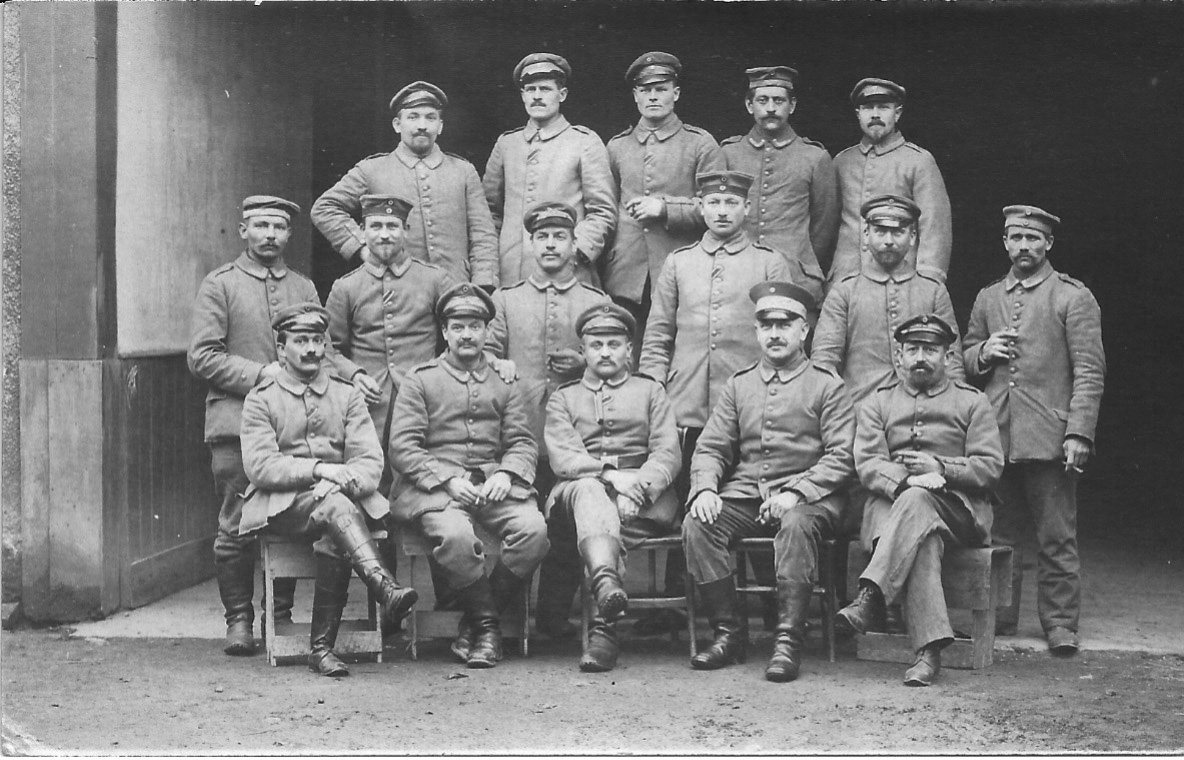

Bischoff’s 3d Battalion initial defensive scheme for the southern portion of Belleau Wood, 4–5 June 1918.

War Diary, 3d Battalion, 461st Infantry Regiment, 1–17 June 1918, German War Diaries, vol. 4

When the Marines commenced the two-pronged assault of Belleau Wood late in the afternoon of 6 June 1918, the 3d Battalion, 5th Regiment, and the 3d Battalion, 6th Regiment, were greeted with devastating fire from the prepared positions. “By far from weakly held, Belleau Wood contained a whole German regiment, the [461st Infantry Regiment] of the [237th Infantry Division], with an effective strength according to the Division report of 28 officers and 1141 men.”[92] By the time the next day dawned, the Marines had suffered more casualties than in all the years of the Marine Corps’ existence up to that time. The total loss for the day was 31 officers and 1,056 men killed, wounded, or missing.[93] The 461st Infantry Regiment suffered many casualties itself that day as well. German lieutenant colonel Ernst Otto’s excellent account of the battle states the division suffered 6 officers and 72 enlisted killed, 10 officers and 218 enlisted wounded, and 5 officers and 90 enlisted missing.[94]

As described by U.S. Army major general James G. Harbord, who commanded the 4th Brigade at the time, Belleau Wood was approximately 1.6 kilometers (1 mile) square with a dense tangle of undergrowth.

The topography of the greater part of the wood, especially in the eastern and southern portions, was extremely rugged and rocky, none of which was shown in any map available at the time. Great irregular boulders . . . were piled up and over and against one another. . . . These afforded shelter for machine-gun nests, with disposition in depth and flanking one another, generally so rugged that only direct hits of artillery were effective against them.[95]

From 6 June onward, the struggle for Belleau Wood was a violent struggle of close combat with Marine battalions slowly forcing the Germans to withdraw. Unfortunately for the Marines, the depleted 461st Infantry Regiment mounted a stout defense and remained in control of the wood until relieved due to exhaustion.[96] The battle finally concluded on 26 June when the 3d Battalion, 5th Regiment, drove the last of the Germans from the northern edge of the forest back into the village of Belleau.

German defensive reorganization, 9–10 June 1918, with Bischoff’s 1st Battalion and 2d Battalion, 40th Hohenzollern Fusilier Regiment.

War Diary, 2d Battalion, 40th Fusilier Regiment, 7 June–3 July 1918, German War Diaries, vol. 3

The 461st Infantry Regiment might have been successful longer but for one tactical blunder by higher command prior to its withdrawal from the fighting on 16 June.[97] When his regiment arrived in the area, Major Bischoff was assigned the responsibility of occupying Belleau Wood. As noted above, he immediately began to create a wooded fortress, taking advantage of the natural obstacles and terrain. An experienced combat veteran, he deployed his regiment throughout the woods, tying in with adjacent units, especially the 10th Division that held the village of Bouresches to his left. Defended by four companies (9th, 10th, 11th, and 12th) of his III Battalion, this left flank in the southeast corner of the Belleau Wood proved critical in his defense.

Medals and honors awarded to LtCol Bischoff: (top) Pour le Mérite medal; (middle, left to right) Iron Cross 2d Class, Royal House Order of Hohenzollern 3d Class (knight) with swords, Red Eagle Order 4th Class with swords, Crown Order 4th class with swords, Long Service award (25 years of service), Southwest Africa Service medal; Colonial Service medal, Kaiser Wilhelm Centenary medal, Bavarian Military Merit Order 4th class with swords, and the Ottoman Empire Military War Medal for Merit (Gallipoli Star); and (bottom, left to right) Iron Cross 1st Class and the Ottoman Military War medal.

Courtesy of personal collection of George Malick, San Jose, Costa Rica

For the next several days, the southern half of Belleau Wood and Bouresches were the focal points of severe fighting, especially the left flank units of Bischoff’s 461st Infantry Regiment. Bischoff was constantly in the woods, even during the strongest artillery fire, and led all counterattacks personally. Only because of his personal bravery and effective leadership did the regiment maintain its hold of the woods.[98]

Following the fall of Bouresches during the night of 6 June, the German 10th Infantry Division was no longer combat effective and was replaced by the 28th Infantry Division. As part of the relief, the new division’s 40th Fusilier Regiment was given responsibility for the southeastern portion of Belleau Wood previously held by the left flank unit of Bischoff’s regiment. During this reorganization between 7 and 9 June, the four frontline companies of the III Battalion, 461st Infantry Regiment, were replaced with only two, the 7th and 8th Companies, from the 40th Fusiliers (see map no. 38). Major Bischoff was furious and complained to the division commander that the terrain demanded more forces to defend.[99] He was well aware that the nature of the terrain and heavy undergrowth would frustrate coordination between units in case of an attack at the boundary.

Field Marshall Irwin Rommel noted the hazards of combat in heavily forested areas in his classic Infantry Attacks after the war:

The fight in Doulcon woods emphasizes the difficulties of forest fighting. One sees nothing of the enemy. The bullets strike with a loud crash against trees and branches, innumerable ricochets fill the air, and it is hard to tell the direction of the enemy fire. It is difficult to maintain direction and contact in the front line; the commander can control only the men closest to him, permitting the remaining troops to get out of hand. Digging shelters in a woods [sic] is difficult because of roots. The position of the front line becomes untenable when—as in the Doulcon woods—one’s own troops open fire from the rear, for the front line is caught between two lines of fire.[100]

According to both Colonels Otto and Thomason, Bischoff’s objections went unheeded. The diary of the II Battalion, 40th Fusilier Regiment, indicates that the regiment in fact did relieve the III Battalion, 461st Infantry Regiment, on 8 June with two companies in the line and two companies in reserve outside the woods, north of Bouresches.[101] Later, it appears Major Bischoff’s concerns were addressed partially on 10 June. The II Battalion, 40th Fusiliers, diary for that date notes that the battalion now believed two companies were too weak and assigned another company to the reserve.[102] However, failure to put additional units in the woods was a costly mistake.

The 4th Brigade attacked the Germans again in force on 11 June in the center of Belleau Wood. With the 2d Battalion, 5th Regiment, assaulting from the west and the 1st Battalion, 6th Regiment, entering the woods at the southern edge, the Americans accomplished what Major Bischoff feared. Striking at the boundary between the I Battalion, 461st Infantry Regiment, and the II Battalion, 40th Fusiliers, the Corps’ 5th Regiment met stiff resistance and the assaulting companies on the right turned south to find the 6th Regiment’s attackers. Unfortunately for the Germans defenders, the Marines collided with right flank of the 40th Fusiliers. As noted in the II Battalion, 40th Fusiliers’ war diary, the 5th Regiment attacked through the sector of 461st Infantry Regiment which meant they were already in the rear of the two forward German companies of the fusiliers.[103] Almost simultaneously, elements of the Marine Corps’ 1st Battalion, 6th Regiment, attacked the 40th Fusiliers on the other flank. The result was that the German regiment was attacked in both flanks and driven from the woods. As described by Colonel Thomason:

Under such pressure, the two companies of the 40th were torn to pieces, and their heavy machine gun defense broken up. The support and reserve companies, approaching from the east were caught in flanking fire from [the Marines in] Bouresches, and stopped. The developments anticipated by the 461st Regiment [i.e., Major Bischoff] . . . were all realized.[104]

A complete disaster was prevented by a counterattack from two companies of 461st Infantry Regiment, but the Germans were not able to recover the territory lost.[105] Now controlling the southern portion of Belleau Wood, the Marines directed their attention solely to 461st Infantry Regiment to the north, the only German unit left in the woods. A German defeat was only a matter of time.

Following a failed counterattack by Bischoff’s regiment and the 110th Baden Grenadiers, 28th Infantry Division, on 13 June, the Germans abandoned any intention of recapturing Belleau Wood in its entirety and ceased offensive operations.[106] After a week of hard fighting, their physical condition was deteriorating due to exhaustion and illness. Indeed, the 12th Company, III Battalion, 461st Infantry Regiment, had already requested relief on 11 June because the “combat power of most of the men is zero.”[107] According to the Reich Archives account:

The capability of the regiments employed here had been dramatically reduced, not only as a result of the casualties but also because of the wave of influenza that had swept the entire German Army like an epidemic on 9 June. On 13 June, for example, the combat strength of the [461st Regiment in the wood] was (excluding machine gun company and supply units): . . . 12 officers, 429 troops[108]

Even with normal personnel rotations and casualties prior to Belleau Wood, this figure is remarkable when you consider the normal regimental complement was roughly 1,176.[109] The situation was so desperate that the division commander was forced to use every spare man he could find, placing in the line 340 “orderlies, liaison agents, and odd details serving in rear areas.”[110] They were sorely needed. According to Lieutenant Colonel Otto, the 461st Infantry Regiment alone suffered 303 killed in action and 1,077 wounded between 6 and 16 June.[111] Indeed, the entire 237th Infantry Division was so decimated by combat and illness that it was withdrawn from the sector by 22 June.[112]

Slowly but surely during the next few days, the German perimeter shrank until they held only the northernmost edge of Belleau Wood anchored by the old hunting lodge, referred to as the Pavilion. Scarred by battle damage, it still stands today as a testament to the savage conflict. The end came on 26 June when the 3d Battalion, 5th Regiment, drove the last of the defenders of the 87th Infantry Division from Belleau Wood and the American battalion commander announced, “Belleau Woods now U.S. Marine Corps entirely.”[113]

By the end of June, the mangled 237th Infantry Division was relocated to the Vauquois sector near Verdun and received 2,000 replacements. The butcher’s bill was considerable for the defense of Belleau Wood. During this rest and recuperation period Major Bischoff was awarded the Pour Le Mérite on 30 June 1918, for the defense of Belleau Wood earlier that month.[114] The Pour Le Mérite, known popularly as the “Blue Max,” was the German Reich’s highest award for gallantry. The citation reads in part:

In the period from June 3 to June 11, Major Bischoff repeatedly repelled the American 2d Division’s constant attacks against the forest, which resulted in heavy enemy losses. He held in the face of heavy artillery fire and personally led the defense and counterattack. It was only thanks to his courage and comprehensive actions that he was able to hold the forest with the weakened remnants of his regiment against superior forces. He led his regiment in an exemplary manner in difficult circumstances.[115]

After being considered combat-ready in late August, the division reinforced units at St. Aubin in northern France but was withdrawn in early September. Relieving the 34th Infantry Division in the area between Saint-Quentin and Soissons on 25 September 1918, the 237th Infantry Division participated eventually in the series of final battles of the war as the German Army withdrew from one defensive line to another and suffered heavy casualties.[116] Unfortunately, Major Bischoff was recommended for promotion to lieutenant colonel in November 1918, but the promotion was never authorized as the war ended.[117] On the day following the Armistice, it began the return to Germany and ultimate demobilization.[118]

At the end of the war, Bischoff was swept up in the collapse of the German Empire. With the abdication of the Kaiser, withdrawal from France and demobilization after the Armistice, he was a Prussian officer with an uncertain and unparalleled predicament.[119] Indeed, as noted by J. W. Wheeler-Bennett in The Nemesis of Power: The German Army in Politics 1918–1945, the Prussian officer corps were a military caste bound only by their oath of “unconditional obedience” to the Kaiser.[120] They did not consider themselves bound by civil law, which obviously caused problems with a democratic transition. This point is aptly described in an infamous anonymous novel of military service in the Prussian Army published in 1904. In one scene in Life in A German Crack Regiment, an older retired officer drinking with his son, a serving officer, laments:

When the cry is raised against them by the other classes the officers always defend themselves with, “Remember we belong to the highest caste; we have our own sense of honour [sic], which you cannot understand; our thoughts are not your thoughts, nor yours ours, God be thanked!”[121]

In the face of domestic anarchy and threats from the Poles and Russians in the east, political leaders of Germany looked to these professionals to lead volunteer units of returning veterans to provide stability during the Weimar Republic. These paramilitary units, or Freikorps, sprang up all over Germany as the war ended in response to the internal threats, perceived and real, from independent socialists and Bolsheviks.[122] Comprised of demobilized soldiers longing for effective leadership and stung with the bitterness of defeat and social revolution manifesting in Germany, the units gravitated to men like Bischoff, one of the professional army officers volunteering to lead them.[123] As a German nationalist and known effective combat leader, he went on to command the Iron Division of the Freikorps (Free Corps) in the Baltic War in 1919.

Thorensberg (now Torņakalns) is a neighborhood of Riga, Latvia, located on the western bank of the Daugava River, 1920.

Bischoff, Die letzte Front, Geschichte der Eiserne Division im Baltikum, 1919 (Berlin: Buch und Tiefdruck Gesellschaft m.b.H, 1935), after 222

The staff of Eiserne Division in the Baltic, 1919.

Suddeutsch Zeitung Photo Archive

Bischoff (center) at Riga Bridge, 1919.

Alamy Images

Added to that chaotic situation were concerns about the Baltic states occupied by the Germans during the war. The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk ended the war in the east with Soviet Russia in 1917 and ceded the Baltic states to Germany. With the 1918 Armistice, however, Soviet Russia renounced the Brest-Litovsk agreement. As the Baltic provinces began independence movements in face of the German defeat, Soviet forces invaded. The Inter-Allied Commission of Control created by the Versailles Treaty was concerned about Soviet Russia’s expansion and came up with a clever plan to thwart the “red peril”: use German troops to defend the Baltics against the Soviets.[124] This plan also gave the German High Command an opportunity to “redeem the defeat in the West.”[125] With existing German Army units still in the region, Germany was given the responsibility to maintain order and resist the Soviets.[126] Thus, a German force was created with German veterans under command of General Rüdiger von der Goltz. Included in the composite force was a Freikorps unit known as the Iron Brigade.

The Iron (or Eiserne) Brigade was created during November 1918 and Bischoff would be its commander beginning in January 1919, now reorganized as a division.[127] The new division was comprised of remnants of the German 8th Army who been stationed in the region and refused to leave because they “wanted to settle in the country,” and new volunteers from Germany looking for a fight and any loot that may be available as a result.[128] However, the original Iron Brigade was not successful in the early fighting in the Baltic against Russian invaders. Bischoff “managed only by the strength of his personality and his manner” to mold it into an effective division-size force after his arrival on 7 January 1919.[129]

In The Kings Depart: The Tragedy of Germany—Versailles and the German Revolution, author Richard M. Watt notes:

Though only a major, Bischoff was already a legendary figure. He did everything with superb style. When complimented on the ease with which he lit his cigarette in a strong wind, Bischoff shrugged and said, “Oh, you learn that. . . . This is my twelfth year of warmaking—eight years in Africa, then the World War.”[130]

Not surprisingly, the Iron Division was considered one of the better military organizations during this chaotic period in German history.

On 3 March 1919, a combined German and Latvian Army under the command of General Goltz (1865–1946), including the Iron Division, drove the Russians from Latvia within a month.[131] However, the victory bore bitter fruit, as more German recruits arrived from Germany with unrealistic promises of Latvian citizenship. The German Freikorps force captured Riga from Soviet Latvian defenders on 22 May 1919, but the relationship between the hosts and the Germans began to sour. The Germans alienated their hosts with instances of pillage, plunder, and other excesses. Any hope of citizenship in Latvia was quickly quashed. As a result, the German units were becoming increasingly irrelevant, and the embryonic national governments of Lativa and Lithuania were anxious for the Germans to return to Germany.[132]

Map of the Battle for Riga, 1919.

Representations of the post-war battles of German troops and Freikorps, vol. 2 (Berlin: E. S. Mittler and Sohn, 1937)

Suffering defeats in June–July 1919, the Freikorps units became concerned about lack of support from the German government and calls for all German forces to return to Germany following the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on 28 June 1919. As author Annemarie H. Sammartino notes: “As prospects in Germany became increasingly bleak, the Freikorps fighters found consolation in the east.”[133] While some of the officers as German nationalists, including Bischoff, contemplated a coup attempt against the German government to reverse the humiliation of Versailles, the Freikorps soldiers rejected this plan in hopes of remaining in the Baltics.[134]

The negotiations on the terms of the status of the Freikorps with the German government dragged on in August 1919 without resolution until a dramatic event at the Mitau railroad station on 24 August. According to veteran Ernst von Salomon, as a regiment moved to board a train back to Germany,

a tall sunburnt officer stepped on the platform. At his neck shone the Pour le mérite. He was the C.O. of the Iron Division, Major Bischoff. He looked at the train—the soldiers crowded round him filled with vague hopes. Officers joined them. The major raised his hand. “I absolutely forbid the withdrawal of the Iron Division.” That was mutiny.[135]

Mutiny, indeed. However, Bischoff spoke earnestly for the interests of the men of the Iron Division who felt they were betrayed by both the Latvian and German governments. The former was condemned for refusing the promised citizenship and the latter for not supporting the troops in their effort to obtain citizenship.[136] This must have been a difficult decision for a career Prussian officer. Major Bischoff must have realized the implications of refusing to comply with orders from higher headquarters. However, showing considerable care for his soldiers, whom he had led in a hard campaign, he nevertheless chose the dramatic gesture at the train station and would not abandon them. As he recalled in his memoir:

That’s why I didn’t hesitate for a moment to take responsibility towards the government and command authorities. It weighed more heavily on me towards the troops. In the old army, we officers had been brought up to regard every single one of our subordinates as an asset entrusted to our trust. And each one was only a link in the whole system built on duty, obedience and justice, which ultimately culminated in the person of the Kaiser. Now the officer faced his troop alone and as a personality. The volunteer had committed himself to him, not to the government or a higher office. This gave the leaders a heavy duty to stand up for their troops.[137]

General Goltz was sympathetic as well, although he could not approve of the refusal of orders. To mitigate the situation, Goltz issued a VI Reserve Corps order in which he stated, “In spite of my disapproval of the refusal to obey orders, I cannot abandon the troops. I will convey these demands to the German Government, advocate for them, and continue to care for the troops until the decision is made.”[138]

As Ernst von Salomon reported, some soldiers accepted the orders from the German government and left. Others, like himself, severed any ties to the new Germany and remained.[139] They soon became volunteers in a new West Russian Volunteer Army commanded by the White Russian General Pavel Avalov-Bermondt.[140]

However, the subsequent fall season of 1919 proved to be one of misfortune and disappointment for the “refugee” German contingent. With the refusal of many of the Freikorps soldiers to obey the orders to return, the German government was under increasing pressure from the victorious Allies to force their removal. As the White Army began its campaign on 8 October 1919, the German government was closing the border with Lithuania and, thereby, cutting off the German contingent from reinforcements and supplies. As Bischoff wrote later,

Most disastrous was the rapid decrease in our combat strength. On October 8, the division had carried out the seemingly impossible attack through the swamp to Riga; it had literally been in the water for 48 hours in freezing wind and rain. The clothing was worn out, many did not even have a coat, the shoes were worn out, and there was no change of underwear or woolen socks. The Iron formation, for example, sent 80 men to the military hospital on two consecutive days due to pneumonia and intestinal diseases. Lack of nutrition and clothing was the cause in the unfavorable weather. The battles were heavy and costly in terms of lives. The ranks thinned out quickly and alarmingly.[141]

By November, the army had not received any supplies of men, ammunition, or materiel since the Germans closed their border. Bischoff’s assessment for the future was bleak:

In view of the military and general situation, I had to admit to myself already during the night of November 19/20 that not only was a continuation of the fight hopeless, but that each day of our remaining there increased the danger of being cut off from our routes of retreat.[142]

In view of the poor state of the combined West Russian Volunteer Army, Bischoff notified the general command on 20 November that the German contingent was retreating under his command and that he had ordered the evacuation of Mitau for the night of 20–21 November. At nightfall, the troops began to separate from the opposing Latvian forces as ordered and slowly withdrew toward Lithuania with the goal of returning to Germany. The German military units left Latvia on 30 November 1919 and finally returned to Germany on 16 December.[143] Bischoff’s return to Germany was anything but quiet with demands for courts-martial of the mutinous officers for their impunity and their stubborn defiance of civilian authority and failure to adhere to directions from the German government.[144] However, there were calls for amnesty, especially for Bischoff, as he was considered the “soul of his division” and the troops were so attached to him.[145]

Jumping into the fire from the frying pan, Bischoff then participated in an unsuccessful coup known as the Kapp Putsch on 13 March 1920, which was an unsuccessful coup d’etat attempting to overthrow the Weimar Republic. Objecting to the implementation of the Treaty of Versailles and the mandatory reduction of the German Army, many prominent leaders of the coup were former imperial officers, now Reichswehr and Freikorps officers, including several Pour le Mérite recipients like Bischoff. In fact, Bischoff resisted any attempts to demobilize his Iron Division on its return from the Baltic, and it was still intact in the German countryside.[146] Under the leadership of naval captain Hermann Erhardt, a naval brigade stormed into Berlin to take over the government as officials fled. A new chancellor, Wolfgang Kapp, assumed the leadership of the German government. However, the coup never got off the ground. Kapp’s military leader, General Freiherr Walther von Lüttwitz, failed to gain the support of the government’s senior military commanders, who really controlled the power of the Weimar Republic.[147] Facing intense resistance from the socialists and civil servants, alongside a debilitating general labor strike, the coup collapsed on 17 March.

Arrested for treason this time, Bischoff was fortunate enough to be released and retired on 8 April 1920.[148] Unfortunately, his pension was suspended effective 1 April 1920. To escape prosecution, he left Germany and moved to Vienna, Austria. He remained there in exile with his new bride, the Baroness Dorothea von Fircks (1878–1968), from an established Baltic noble family whom he married on 24 March 1920.[149]

Exile did not protect him from controversy. Indicted in July 1920 for high treason, Bischoff’s assets were seized in December 1921. Although arrest warrants for the Kapp putschists were issued in August 1922, none of conspirators were tried once the Reichstag passed a law on 2 August 1925 that pardoned crimes committed during the putsch. Subsequently, as reported in a German newspaper, criminal arrest warrants were then quashed.[150] Unfortunately, that still did not end the matter for Bischoff.

While in exile, he waged an ongoing postal battle with the German Reich Finance Ministry over his military pension and the government claims for damages from the Kapp Putsch.[151] With the treason indictment, Bischoff’s military pension had been withheld until 1 August 1925. Appealing the decision to withhold any back pension, Bischoff was successful in a Munich Pension Court decision in April 1926 in recovering pension payments starting 1 January 1923. The recovery of any monies owed to him from 1 April 1920 to 31 December 1922 was considered barred by a statute of limitations.

Compounding the financial injury, in its meeting of 12 July 1927, the Reich Cabinet decided to recover the claims for damages from the Kapp Putsch against the pension entitlements of the main military conspirators: retired General Baron von Lüttwitz, Bischoff, and retired Imperial Navy Captain Ehrhardt.[152] The Reich Labor Ministry rejected such claims, as the pensions were not attachable for such purposes.[153]

Notwithstanding the rejection, on 12 August 1929, the Reich Cabinet assessed Bischoff and the others responsible for 6 million Reichsmarks in gold for damage arising from their involvement in the Kapp Putsch. Ehrhardt sued to stop the entire process.[154] On 2 December 1930, the German Supreme Court overruled an earlier ruling of the Court of Appeal whose decision held the damages claim against Ehrhardt’s pension were inadmissible. Following a hearing on 2 June 1931, the Berlin Court of Appeal ruled on 23 July that there was insufficient evidence to determine whether Ehrhardt was culpable financially for any alleged damages during the Kapp Putsch.[155] Although the Reich Finance Ministry’s records for Bischoff are incomplete, it is reasonable to assume that the decision was applicable to Bischoff.

Bischoff returned to Germany sometime between January and September 1934, as reflected in the addresses in his correspondence in the Reich Finance Ministry’s files.[156] In retirement on the eve of World War II, Bischoff was promoted to the brevet or honorary rank of lieutenant colonel on 27 August 1939, the 25th anniversary of the Battle of Tannenberg.[157] All living Pour Le Mérite winners of World War I were invited to the Hindenburg Memorial in East Prussia and given honorary promotions. Bischoff was honored with the brevet rank of lieutenant colonel at a classic massive Nazi ceremony attended by Adolf Hitler. Some believe it was intended by Hitler to mask the movement of the German Army to the region as a prelude to the invasion of Poland shortly thereafter.[158] Bischoff never wore the uniform again due to poor health, as reflected in the Finance Ministry’s files. He died on 12 December 1948 of coronary heart disease in Berlin-Charlottenburg, Germany, where he was buried.[159]

Conclusion

When the 4th Marine Brigade faced the wheat fields in front of Belleau Wood in June 1918, little did they know that the opposing German commander was a career Prussian officer and a seasoned veteran of soldiering. Prior to that eventful summer, Bischoff had amassed considerable experience in leading troops in battle. Beginning his military career in German colonial Africa, he learned valuable lessons in tactics and combat leadership with the Schutztruppe. It was here that Bischoff exhibited the rare ability to analyze the battlefield and to determine how that battle would transpire. He was decorated for doing just that and saving his commander in 1904.

Successfully transitioning to the battlefields of Europe in 1914, Bischoff possessed a remarkable skill to translate those lessons to a modern army of the industrial age. He became a respected battalion commander who received prestigious awards for valor during the battles in rugged eastern France, the desolate Sinai Desert, and the southern Russian front. His actions in 1917 leading his regiment to secure the Sereth River crossing exemplify his knack of understanding the importance of his mission and the impact of his leadership on men in battle.

In 1918, when assigned the task of defending Belleau Wood, Bischoff exhibited the quality of tactical leadership so admired today. A critical component of this quality is the ability to develop an understanding of the battlespace, or coup d’œil as described by Carl von Clausewitz. This is the talent to observe the battlefield and ascertain those opportunities in the operational environment that will contribute to success. It is obvious from all accounts of the battle for Belleau Wood that Major Bischoff did just that. Although his forces were depleted by combat and disease, his effective use of terrain, supplemental positions, and supporting arms in the tactical defense allowed his regiment to hold the woods until withdrawn on 16 June. This is quite remarkable considering that Belleau Wood was, according to General Harbord, about 1.6 kilometers (1 mile) square. Nevertheless, Bischoff persevered and was decorated with his nation’s highest award for gallantry for his conduct during that hot summer of 1918. Major Bischoff left behind a notable record of service marked by dedication to his nation, great leadership in battle, and considerable physical endurance. His tactical skills highlight his ability to maintain discipline and morale among his troops during times of greatest need. With the armistice, his exceptional abilities were called on again.

The German military campaign in the Baltic states in 1919 began successfully as the Russian Red Army was driven out. This success was due in large measure to the leadership of Bischoff and the fighting prowess of the men of his Iron Division. However, the German volunteers were mere pawns in postwar politics and promises made were not followed by actions on their behalf. Pursued by the Allies and vilified by their own government, whom they felt had abandoned them, the division was held together by Bischoff’s steel will alone. As a commander, he took very seriously the desires and dreams of his men, who performed so well under brutal conditions. He understood his responsibility in support of his men and their aspirations for a better future in the Baltic states.

At great professional risk as a career officer, he declined to comply with the German government’s directive to return to Germany. With a heightened sense of honor, and a bit of theatrics, he made sure that the plight of his soldiers was publicized by the railroad station speech. His actions at the railroad station in August 1919 are the stuff of legends. But this performance brought them only a temporary reprieve.

Eventually, the German government abandoned them, leaving to suffer under terrible conditions with little chance of success. Only very reluctantly, in the fall of 1919 when all hopes were extinguished, did Bischoff lead his men across the German frontier in an outstanding example of military leadership. Unfortunately, his greatest military triumph would lead to his financial ruin through his involvement in the Kapp Putsch.

Josef Bischoff was a highly decorated combat veteran who has the distinction of being one of the few tactical combat leaders to be mentioned by name in his enemy’s battle histories, probably a greater tribute to his mastery of the art of war. Commanding from the company to division level against different foes in different terrains, he consistently exemplified those attributes of soldierly virtue so greatly admired today. He should be considered one of the most effective commanders to oppose Americans at war in any era.

•1775•

Endnotes

[1] John W. Thomason Jr., The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry in World War I, ed. George B. Clark (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2006), 96.

[2] Oliver L. Spaulding and John W. Wright, The Second Division, American Expeditionary Force in France, 1917–1919 (New York: Hillman Press for Second Division Association, 1937; Nashville, TN: Battery Press, 1989), 53.

[3] Spaulding and Wright, The Second Division, American Expeditionary Force in France, 1917–1919, 56.

[4] Karl-Fredrich Hildebrand and Christian Zweng, Die Ritter des Ordens Pour le Mérite des I. Weltkrieg [Knights of the Order Pour le Mérite of the First World War], vol. 2, bk. 1 (Osnabrück: Biblio Verlag, 1999), 118.

[5] Hildebrand and Zweng, Die Ritter des Ordens Pour le Mérite des I. Weltkrieg, 2:1:119.

[6] Hildebrand and Zweng, Die Ritter des Ordens Pour le Mérite des I. Weltkrieg, 2:1:119.

[7] Ernst Nigmann, The Imperial Protectorate Force, German East Africa, 1889–1911, trans. Robert E. Dohrenwend (Nashville, TN: Battery Press, 2005), 267.

[8] Nigmann, The Imperial Protectorate Force, German East Africa, 1889–1911, 181.

[9] Nigmann, The Imperial Protectorate Force, German East Africa, 1889–1911, 181.

[10] Nigmann, The Imperial Protectorate Force, German East Africa, 1889–1911, 267.

[11] Kriegsgeschichtlichen Abteilung I des Großen Generalstabes, Die Kämpfe der Deutschen Truppen in Sütwest-afrika, vol. 1, Der Feldzug gegen die Hereros (Berlin: Ernst Siegfired Mittler und Sohn, 1906), 218.

[12] Die Kämpfe der Deutschen Truppen in Sütwest-afrika, vol. 1, 236. Left foot wound mentioned in undated medical note at German Federal Archives, Reich Finance Ministry, BArch, R 43-I/2725, PDF Doc. 3841.

[13] Kolonial-Abteilung des Auswärtigen Amts, Deutsches Kolonialblatt 1906: Amtsblatt für die Schutzgebiete in Afrika und in der Südsee, vol. 17 (Berlin: Verlag von Ernst Siegfried Mittler und Sohn, 1906), 544. The Order of the Red Eagle (German: Roter Adlerorden) was another Prussian award for excellence, next higher in order than the Royal Order of the Crown. The designation “with swords” also recognizes exemplary conduct in combat. William E. Hamelman, Of Red Eagles and Royal Crowns (Dallas, TX: Matthaus Publishers, 1978), 54. See also “Decorations: Order of the Red Eagle—Roter Adlerorden,” World War I—The Officers, Uboat.net, accessed 1 July 2015.

[14] Hildebrand and Zweng, Die Ritter des Ordens Pour le Mérite des I. Weltkrieg, 119, indicates he was awarded the Order of the Crown and the regimental history states, “Lieutenant Bischoff, who had already been honored with the Royal Order 4th class with swords, took part in the battle on 15 August [1904].” Hans Guhr, Geschichte des Infanterie-Regiments Keith 1. Oberschlesisches Nr. 22 1813–1913 (Katowice, PL: Phönix-Verlag, 1913), 288. Translation assistance from Mr. J. B. Potter. The Royal Order of the Crown (German: Kronenorden) was Prussia’s lowest ranking order of chivalry and fourth in line for Prussian Orders, honor awards, and campaign/commemorative medals. The designation with swords recognizes exemplary conduct in combat. Hamelman, Of Red Eagles and Royal Crowns, 54. See also “Medals,” Uniform and Insignia Details, GermanColonialUniforms.co.uk, accessed 1 July 2015.

[15] Guhr, Geschichte des Infanterie-Regiments Keith 1. Oberschlesisches Nr. 22 1813–1913, 288–89.

[16] Kriegsgeschichtlichen Abteilung I des Großen Generalstabes, Die Kämpfe der Deutschen Truppen in Südwestafrika, booklet 1, Ausbruch des Herero-Aufstandes (Berlin: Ernst Siegfired Mittler und Sohn, 1906), 304; and Hanns Möller, Geschicte der Ritte des Ordens “pour le mérite” im Weltkrieg (Berlin: Verlag Bernard & Graefe, 1935), 95.

[17] Mark Cocker, Rivers of Blood, Rivers of Gold (New York: Grove Press, 1998), 340–41.

[18] Hildebrand and Zweng, Die Ritter des Ordens Pour le Mérite des I. Weltkrieg, 2:1:119; and “4 Badiches Infanterie-Regiment Prinz Wilhelm Nr. 112,” Militärisches Wochenblatt, no. 13 (1909): 284, Germany, Military, and Marine Weekly Publications, 1816–1942, Ancestry.com, accessed 10 May 2020. The Militärisches Wochenblatt (Military Weekly) began as a publication for the Prussian Army and later served as a national publication for the German Imperial Army. This military periodical served to both inform and educate members of the German armed forces as an official military journal printing army and wartime news; notices of appointments, promotions, awards, retirements, deaths, and the like; and articles on tactics, history, organization, combat, weaponry, and other topics of interest.

[19] “4 Badiches Infanterie-Regiment Prinz Wilhelm Nr. 112,” 284.

[20] Karl Deuringer, The First Battle of the First World War–Alsace-Lorraine (Brimscombe Port, UK: History Press, 2014), 20.

[21] The German military used Roman numerals to designate battalions. MajGen Frederich Zechlin, Das Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 60 im Weltkrieg [The 60th Reserve Infantry Regiment in the World War] (Oldenberg: Berlin, 1926), 12. Translation assistance from LtCol Helmut Theissen, German Army (Ret).

[22] Zechlin, Das Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 60 im Weltkrieg, 12; and Dennis Showalter, Instrument of War: The German Army, 1914–18 (Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2016), 42.

[23] Hermann Cron, Imperial German Army, 1914–1918 (Solihull, UK: Helion, 2001), 327.

[24] American Armies and Battlefields in Europe: A History, Guide, and Reference Book (Washington, DC: American Battle Monuments Commission, Government Printing Office, 1938), 419.

[25] Cron, Imperial Germany Army, 1914–1918, 137.

[26] Zechlin, Das Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 60 im Weltkrieg, 14–15.

[27] Zechlin, Das Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 60 im Weltkrieg, 15.

[28] Zechlin, Das Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 60 im Weltkrieg, 16.

[29] Zechlin, Das Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 60 im Weltkrieg, 16.

[30] Zechlin, Das Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 60 im Weltkrieg, 17. This was the 10th Royal Bavarian Reserve Infantry Brigade, named for the commander, LtGen August Ipelkofer (1857–1933). Formationsgeschicte und Stellunbesetzung der deutschen Streitkräfte 1815–1990 (Osnabrück: Biblio Verlag, 1990), vol. 1, 659. See also “Koeniglich Bayerische Reserve-Infanterie-Brigade,” Wikipedia, accessed 4 January 22.

[31] Cron, Imperial Germany Army, 1914–1918; 111; and Deuringer, The First Battle of the First World War–Alsace-Lorraine, 278.

[32] Zechlin, Das Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 60 im Weltkrieg, 17.

[33] Zechlin, Das Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 60 im Weltkrieg, 18.

[34] Zechlin, Das Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 60 im Weltkrieg, 19.

[35] Zechlin, Das Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 60 im Weltkrieg, 23. Presumably the Iron Cross, 2d Class.

[36] Histories of Two Hundred and Fifty-one Divisions of the German Army (1914–1918) (Washington, DC: U.S. War Office, 1920; London: Naval & Military Press, 1989), 397.

[37] Zechlin, Das Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 60 im Weltkrieg, 31.

[38] Cron, Imperial Germany Army, 1914–1918, 111.

[39] Zechlin, Das Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 60 im Weltkrieg, 38.

[40] U.S. War Department, Histories of Two Hundred and Fifty-one Divisions of the German Army, 234, 45.

[41] Zechlin, Das Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 60 im Weltkrieg, 44–45.

[42] Zechlin, Das Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 60 im Weltkrieg, annex 5 “Battle Losses,” 244.

[43] Zechlin, Das Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 60 im Weltkrieg, 47.

[44] Zechlin, Das Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 60 im Weltkrieg, 50.

[45] Zechlin, Das Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 60 im Weltkrieg, 50.

[46] Zechlin, Das Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 60 im Weltkrieg, 52.

[47] Zechlin, Das Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 60 im Weltkrieg, 52–54.

[48] Zechlin, Das Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 60 im Weltkrieg, 55–58.

[49] Militär-Wochenblatt, no. 232/233 (13 December 1915): 5443–44; Zechlin, Das Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 60 im Weltkrieg, 59; and Erhard Roth, Verleihungen von militärischen Orden und Ehrenzeichen des Königreiches Bayern im Ersten Weltkrieg 1914–1918 (Offenbach: PHV Phaleristischer Verlag Autengruber, 1997), 61.

[50] Zechlin, Das Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 60 im Weltkrieg, 64.

[51] Zechlin, Das Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 60 im Weltkrieg, 68.

[52] Zechlin, Das Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 60 im Weltkrieg, 69.

[53] Cron, Imperial Germany Army, 1914–1918, 61.

[54] Armee-Abteilung Falkenhausen (named for Gen Ludwig Freiherr von Falkenhausen [1844–1936]) was created in Alsace-Lorraine on 17 September 1914 from the parts of 6th Army. The staff of the dissolved Ersatz Corps under Gen Falkenhausen (Pour le Mérite, 23 August 1915; second award, 25 April 1916) took command. Cron, Imperial Germany Army, 1914–1918, 84; Hildebrand and Zweng, Die Ritter des Ordens Pour le Mérite des I. Weltkrieg, 2:1:388; and Bischoff memorandum to Reich Finance Ministry, 7 December1932, German Federal Archives, Reich Finance Ministry, BArch, R 43-I/2725, PDF Doc. 3844ff. Having contracted malaria in East Africa during 1899–1900, his service on the winter western front surely exacerbated any breathing problems. In fact, he was hospitalized between 30 October 1915 and 11 December 1915 for bronchitis. Undated note, German Federal Archives, Reich Finance Ministry, BArch, R 43-I/2725, PDF Doc. 3841.

[55] Zechlin, Das Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 60 im Weltkrieg, 69.

[56] Capt Heinrich Römer and Lt Wilhelm Ande, Mit deutschen Maschinengewehren durch die wüste Sinai (Berlin: Industrieverlag Spaeth & Linde, 1917), 19.

[57] Specifically “one machine gun battalion with 50 guns, four flak-platoons, four heavy batteries including two mörser [heavy mortar] batteries, three minenwerfer [trench mortar] detachments, one aviation unit with 16 airplanes, a bridge crane, communications, motor vehicles, medical, and catering formations, a collective 140 officers and officials, 1507 men who were prepared to march from Germany in the middle of January.” Reichkriegsministerium, Der Weltkreig 1914–1918, vol. 10, Die Operationen des Jahres 1916 bis zum Wechsel in der Obersten Heeresleitung (Berlin: Verlegt bei E. G. Mittler & Sohn, 1936), 611.

[58] Friedrich Freiherr Kress von Kressenstein (1870–1948), Pour le Mérite, 4 September 1917, General of Artillery (Ret). Kressenstein was part of the German military mission of Gen Otto Liman von Sanders (1855–1929) to the Ottoman Empire.

[59] Hildebrand and Zweng, Die Ritter des Ordens Pour le Mérite des I. Weltkrieg, 2:1:119.

[60] Freiherr Kress von Kressenstein, With the Turks to the Suez Canal (Berlin: Vorhut-Verlag Otto Schlegel, 1938), 179.

[61] Kressenstein, With the Turks to the Suez Canal, 184.

[62] Kressenstein, With the Turks to the Suez Canal, 185.

[63] Der Weltkrieg–1914–1918, Die Operationen des Jahres 1916, vol. 10 (Berlin: Reichskriegsministerium, E. S. Mittler & Sohn, 1936), 613.

[64] Hildebrand and Zweng, Die Ritter des Ordens Pour le Mérite des I. Weltkrieg, 2:1:119.