PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: The marriage of the helicopter and U.S. Navy amphibious ships with a battalion of Marines and supporting elements on board created one of the nation’s most potent and capable weapons systems. The Marine air-ground task force (MAGTF) not only represents the means to influence events by the projection of military power, it also has the inherent capability to undertake a number of missions beyond direct combat action, otherwise known as military operations other than war (MOOTW). This article examines the inherent capability of MAGTFs in MOOTW, highlighting the essentiality of helicopters for such operations, particularly humanitarian and noncombat evacuation operations, by recounting a few of these operations.

Keywords: military operations other than war, MOOTW, Marine air-ground task force, MAGTF, airpower, Marine Aviation, ship-to-shore

The marriage of the helicopter and U.S. Navy amphibious ships with a battalion of Marines and supporting elements on board created one of the nation’s most potent and capable weapons systems. Like combat aircraft on board an aircraft carrier, or nuclear missiles contained within a submarine, the task force represents the means to influence events by the projection of military power. Unlike an aircraft carrier or a nuclear submarine, however, this combination ground-sea-air team, known as a Marine air-ground task force (MAGTF), has the inherent capability to undertake a number of missions beyond direct combat action, otherwise known as military operations other than war (MOOTW). Included in MOOTW are humanitarian assistance, noncombat evacuations, and disaster relief. The organic aviation element was the key connector between land and sea, the conduit that brought the MAGTF’s power to bear and therefore essential for MOOTW.

Marines pioneered helicopter combat operations in the Korean War in the form of vertical assault (or envelopment) tactics but did not perform this task from ships. As helicopter technology advanced, ship-to-shore tactics developed, and the U.S. Navy moved forward to acquire dedicated amphibians, the Marine Corps/Navy created the first MAGTF. The amphibious component was the USS Thetis Bay (CVE 90), which had been converted to a landing platform helicopter (LPH 6). In 1962, the MAGTF became official Marine doctrine, codified in Marine Corps Order 3120.3.1 New and specifically built amphibious ships followed. Regular Marine expeditionary units (MEUs), the smallest of the MAGTFs, composed of a battalion of Marines, a command element, a composite helicopter squadron, and a logistics element, deployed like clockwork to the Navy’s Fifth, Sixth, and Seventh Fleets’ zones of operation.2 MEUs stood ready to conduct a number of operations, direct combat or MOOTW, on behalf of national interests. In 1985, Commandant General Paul X. Kelley ordered that MEUs undergo special operations training to gain additional capabilities to meet existing threats. MEUs became MEU(SOC)s—special operations capable.

With the demise of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, the United States remained as the world’s only superpower. This called for an entirely new national security strategy, of which MOOTW was an essential aspect. The George H. W. Bush administration held that “the United States had to take on a large role as a world leader to guard against human rights abuses, defend democratic regimes, and lead humanitarian efforts.”3 The William J. “Bill” Clinton administration followed in 1994 and issued a national security strategy called “Engagement and Enlargement.” Key military tasks included “noncombat operations, and humanitarian and disaster relief operations, etc.”4

Navy policy shifted from blue-water control-of-the-seas and freedom-of-navigation operations to the littorals. New Navy-Marine Corps doctrine followed, disseminated in the white paper “Forward . . . From the Sea.” The MAGTF was particularly suited to execute the new doctrine.5 It was flexible and could undertake a variety of tasks as the situation demanded and could even be divided to meet needs in different locations. It was unobtrusive and it did not need a base on shore and was therefore nonthreatening to less-than-friendly governments. It had staying power, and was self-sustaining. It could stay on-station almost indefinitely, being resupplied by other ships and aircraft that did not need nations’ overflight approval.6 In the 1990s, MEUs executing humanitarian operations and noncombat evacuations occurred frequently, resulting in many more lives saved by the Navy and Marine team than were taken through combat action.7

This article highlights the inherent capability of MAGTFs in MOOTW operations, emphasizing the essentiality of helicopters for such operations, particularly humanitarian and noncombat evacuation operations (NEOs), by recounting a few of these operations. The operations are recounted chronologically to show the inherent flexibility of MAGTFs in dealing with a variety of situations and missions.

Operation Sharp Edge

As the decade of the 1990s dawned, political instability in the West African region led to violence as rebel groups sought to seize power in the wake of failed government.8 Particularly in Liberia, violence and social chaos placed civilians at risk. On 25 May 1990, Special Operations Capable 22d Marine Expeditionary Unit (22d MEU[SOC]), commanded by Colonel Granville R. Amos, then training in France, was ordered by the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff to proceed to the coastal waters of Liberia. The 22d MEU(SOC) was to provide security for the American embassy and, if required, conduct a NEO, a special operations task for which it had trained. Amos’s aviation combat element (ACE) was composite Marine Medium Helicopter Squadron 261 (HMM-261, Reinforced), commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Emerson N. Gardner.9 To get a force to Liberia as quickly as possible, one Boeing Vertol CH-46 Sea Knight helicopter and 75 Marines were cross-decked to a destroyer and pushed ahead of the rest of the amphibious ready group (ARG).10

In the scramble to plan and prepare to sail for Liberia, HMM-261 mechanics replaced all the transmissions in its 12 CH-46s, because a defective transmission quill shaft had been identified as being at fault in the crash of a CH-46 in another squadron. The supply system gave the squadron top priority for new transmissions. Mechanics worked around the clock to replace the transmissions in all their aircraft. On arrival off the coast of Liberia, all HMM-261’s Sea Knights were ready for action.11

The destroyer with the advance force arrived 2 June and the rest of the ARG arrived the next day. Colonel Amos leveraged his on-call Lockheed KC-130 Hercules detachment from Marine Aerial Refueler Transport Squadron 252 (VMGR-252), supplemented by U.S. Navy C-130s and C-9 Skytrains (military version of a McDonnell-Douglas DC-9), to shuttle supplies into a forward logistics site at Freetown, Sierra Leone, which abuts Liberia to the north. From here, HMM-261 helicopters flew personnel, mail, and cargo to the ARG daily.12 This allowed the Marine sea-based expeditionary unit to remain on station indefinitely.

Despite the initial urgency, the 22d MEU waited off the coast of West Africa in Mamba Station’s sweltering heat for two months. Gardner drilled his aircrews incessantly, practicing contingency missions. Helicopters were essential for any evacuation because the beaches off Monrovia were not suitable for landing craft, plus travel on land was risky because fighters of rival factions prowled the area.13 The ARG remained out of sight over the horizon, ready if the ambassador needed it, but hidden to avoid giving alarm and precipitating a crisis.

Bloody factional fighting closed in on Monrovia and the embassy; helicopter crews saw the carnage of the fighting, butchered bodies afloat in the surf. As the violence grew ever closer to the embassy, on 4 August American ambassador Peter Jon de Vos called for a drawdown of the embassy staff and evacuation of designated American citizens and third-party nationals. Evacuations began the next day.14

Throughout their time on Mamba Station, bright and sunny skies had prevailed. Now that the evacuation was on, weather turned to low clouds with rain and fog that obscured visibility. Marines boarded the HMM-261’s helicopters organized to conduct simultaneous evacuation at Voice of America radio receiving and transmitting sites and the embassy. The poor weather forced the pilots to take off individually instead of in the planned formations. They punched through the clouds and joined in the clear on the other side.15

Lieutenant Colonel Gardner was mission commander, flying the lead CH-46 headed for the first evacuation site, the Voice of America sites. Bell AH-1 Cobra and UH-1 Iroquois (Huey) gunships escorted the transports and bomb-carrying McDonnell-Douglas AV-8B Harrier IIs orbited above the helicopters.16 The first helicopters into the zones carried Marines who clambered out and established safe perimeters. Then empty CH-46s or Sikorsky CH-53 Sea Stallions descended. The evacuees were fitted with life vests and head protection and then boarded. Within the hour, these helicopters carrying evacuees from both radio sites were back on board the USS Saipan (LHA 2).17

A Sikorsky CH-53D Sea Stallion of Marine Medium Helicopter Squadron 261 (HMM-261) lifts off from the flight deck of the USS Saipan (LHA 2) during Operation Sharp Edge. Photo by JO1 Kip Burke, RG 330 Records of the Secretary of Defense, Combined Military Service Digital Photographic Files, 1982–2007, NARA

While these evacuations were carried out, CH-53s loaded with Marines also roared low over the water toward the embassy. Approaching the shore, the helicopters popped up into the embassy’s landing zone.18 The Marines established security, quickly allowing the evacuations to begin and continue through the day with little opposition.

The next week, the Saipan moved south ready to evacuate foreign nationals near Buchanan, Liberia. People had spent the preceding few terrifying days laying on the floors of their houses to avoid gunfire from rampaging factions. The dominant faction belonged to rebel leader Charles Taylor. Marines negotiated with Taylor’s lieutenants, who agreed to the evacuation of about 100 foreign nationals by Marine air, including the Spanish ambassador, a Swiss chargé d’affaires, and the Papal Nuncio.19

In subsequent weeks, the evacuations continued from Monrovia and logistics flights were added. Supplying the embassy with food, water, and generator fuel became an important aspect of the HMM-261 missions. By 21 August, when the 22d MEU was to be relieved by the 26th MEU(SOC), they had evacuated 1,648 persons from Liberia, 132 American citizens, and 1,516 foreign nationals.20

Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait, occurring on 2 August, overshadowed events in Liberia. This put a demand on resources, and dispatching the 26th MEU to western Africa with Hussein rampaging through Kuwait hardly made sense. However, leaving Americans at the mercy of brutal factions in Liberia hardly made sense either. To deal with both contingencies, the 26th MEU was split, resulting in the creation of Contingency Marine Air-Ground Task Force 3-90 (CMAGTF 3-90), nicknamed the Monrovia MAGTF. It was commanded by Major George S. Hartley and consisted of two ships that served as a miniature sea base for a reinforced rifle company, an abbreviated logistics detachment, and a small ACE. This miniature ACE, carved out of the 26th MEU’s ACE, HMM-162, the Golden Eagles, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Darrell A. Browning, consisted of 3 CH-46s, 6 pilots, and 22 maintenance troops. Browning assigned Major Daniel P. Johnson to command the detachment during the first half of the contingency, and Lieutenant Colonel Tommy L. Patton to the second half.21 Although conducted in the shadow of the war in Kuwait, it was still a high-visibility operation—especially should something go wrong.22

Marines of the 22d Marine Expeditionary Unit (22d MEU) stand by to board a helicopter on board USS Saipan (LHA 2) during Operation Sharp Edge. The Marines were flown to the U.S. embassy in Monrovia, Liberia, to augment security and evacuate U.S. and foreign nationals from the fighting between government and rebel forces. Photo by JO1 Kip Burke, RG 330 Records of the Secretary of Defense, Combined Military Service Digital Photographic Files, 1982–2007, NARA

The ACE was based on the USS Whidbey Island (LSD 41), an amphibious ship that was not built to accommodate an aircraft component of any size, but with the help of the crew, suitable adaptations were made. Space was provided for the three CH-46s, ensuring that two could be deck-spotted at all times. The ship’s surface radar was used to provide navigational assistance. An enlisted sailor performed well as an ad hoc air controller, albeit with cursory, on-the-job training.

With only three aircraft available to support the embassy and conduct evacuations, Johnson and Patton knew that success depended on careful stewardship of the Sea Knights. Aircraft maintenance was the critical factor. Maintenance facilities were limited on the Whidbey Island. Because it was not built as an aircraft platform, its deck was lower than a landing helicopter assault (LHA) or LPH’s and as such exposed the CH-46s to corrosive saltwater spray. The other ship of the CMAGTF, the USS Barnstable County (LST 1197), on which the aviation detachment also operated, had an even lower deck. Johnson and Patton understood that every flight hour brought their aircraft closer to a maintenance inspection that would take it temporarily out of flight status. They therefore minimized flights and consolidated missions, trying to fly only one aircraft at a time. They lobbied the Navy ships’ captains to position the Whidbey Island as close as possible to shore to shorten the flight to land and minimize flight time, but the captains refused, citing regulations that ships in this case should operate no closer than 25 miles from shore. The State Department interceded and gave the Navy permission to operate within 15 miles of shore.23

The CMAGTF was at the end of a long resupply line. Aircraft parts had to be flown from the United States to Sigonella, Sicily, then to Freetown, Liberia, and then out to the Whidbey Island or the embassy in Monrovia. The third CH-46 was in effect a parts supply bin; in dire circumstances, parts could be borrowed.24 Sometimes creative maintenance was required. A CH-46 busted a hydraulic line while landing on the Barnstable County. It had to be repaired immediately, as the deck space was going to be needed the next day to lift replenishment stocks on board. There was no replacement part near Mamba Station, therefore a desperate search commenced for a piece of aluminum tubing that would temporarily suffice. In the ship’s galley, the deep fat fryer was found to have a piece of tubing the right diameter. It was cut off and installed on the helicopter, which completed the mission.25

Flight operations focused on maintaining the 80–90 Marines on shore and keeping the embassy staff supplied. Pallets of food, water, and other supplies were flown in daily, including some luxury goods for the State Department staff, to include pallets of beer and liquor, ice cream, and pet food. The Marines providing security on shore subsisted for the most part on meals-ready-to-eat. Fuel to operate the embassy’s generators was constantly required, flown in 500-gallon bladders suspended under the CH-46s. They also hauled passengers, ferrying people between the ships and Monrovia or Freetown. Evacuations continued too.26

Fighting was sporadic in and around Monrovia, and the Liberian president, Samuel K. Doe, was captured by a splinter organization of Charles Taylor’s group, led by Prince Yormie Johnson, who tortured and executed Doe on video. The fighting did not cease, however. Taylor’s faction was divided, with the splinter faction led by Johnson and warring against Taylor’s faction. Therefore, people still wanted out and another 800 people were evacuated.

On 9 January 1991, Operation Sharp Edge ended. A MAGTF had been on Mamba Station seven months and tons of supplies had been delivered.27 The Navy-Marine team were a life support for the American embassy, a positive instrument of American diplomacy, and a life saver. A total of 2,439 persons had been evacuated; fewer than one-tenth were Americans.28

Operation Sea Angel

Out of the dark of night on 29 April 1991, a cyclone’s killer winds and a monstrous tidal wave smashed into Bangladesh, the most densely populated nation on earth. Death and destruction rolled over the southern and eastern coastal region, trees were denuded, livestock perished by the millions, and nearly 140,000 people died. It was one of the most devastating natural disasters of recent times. A massive relief effort began; governments and nongovernmental relief organizations geared up and relief poured in.

As often occurs during natural disasters, the transportation system of Bangladesh was devastated, a severe challenge for delivering relief. People who lived in low-lying coastal regions and off-shore islands were isolated, without food and water, and subject to disease. Relief supplies were available, but there was no way to get them to the people who needed them most. The storm destroyed 60 percent of the Bangladesh Air Force’s helicopters. The U.S. ambassador, William B. Milam, asked whether Marine Corps or Navy assets “might be diverted to assist relief operations?”29

MajGen Henry C. Stackpole III (facing), 3d Marine Division, III Marine Expeditionary Force (III MEF), led the U.S. humanitarian efforts for Operation Sea Angel. Stackpole retired as a lieutenant general. Photo by SSgt Val Gempis, RG 330 Records of the Secretary of Defense, Combined Military Service Digital Photographic Files, 1982–2007, NARA

The 5th Marine Expeditionary Brigade (5th MEB), minus its 11th MEU, and Amphibious Group Three were standing by in the Persian Gulf. In anticipation of assisting with Bangladesh relief efforts, 5th MEB and Amphibious Group 3, led by the USS Tarawa (LHA 1), were ordered homeward on 7 May by way of the Indian Ocean. That would put them off the coast of Bangladesh in seven days, a week after the cyclone struck.30

The State Department and the U.S. military considered an amphibious task force an effective means to help the most people in the quickest way. The devastated area was close to shore and accessible to the MEB’s landing craft and helicopters. An amphibious task force was nonintrusive; military personnel for the most part could remain on board ship and required little support from the host nation. It would not ruffle Bangladeshis’ sensitivities regarding their newly elected, first-ever democratic government.31 Providing discreet humanitarian relief to Bangladesh met President Bush’s and President Clinton’s national security strategies that the military be engaged in spreading goodwill and democracy in an unobtrusive manner.

The critical need for distributing life-saving relief made the 5th MEB’s transport helicopters a key factor. On 9 May, the State Department formally requested the military to provide relief assistance in the form of heavy-lift helicopters, specifically those attached to the 5th MEB. President Bush approved the request on 11 May, and 5th MEB arrived in the Bay of Bengal four days later.32

Marine major general Henry C. Stackpole III commanded the relief effort, called Sea Angel. The new Navy-Marine doctrine, Forward from the Sea, demanded that MAGTFs be joint. Sea Angel demonstrated this capability. The Air Force and Army contingents arrived first and began humanitarian operations. The arrival of 5th MEB’s eight amphibious ships represented the biggest U.S. component of Sea Angel. The 5th MEB, containing 4,000 Marines and sailors, was commanded by Marine Brigadier General Peter J. Rowe. Its ACE, Marine Aircraft Group 50 (MAG 50), was commanded by Colonel Randall L. West and included 26 transport (CH-46s and CH-53s) helicopters.33

The 5th MEB began operations the day after arrival off Bangladesh. General Stackpole hoped for a quick in-and-out operation of no longer than two weeks. He compensated for the new Bangladeshi government’s sensitives by ensuring that no more than 500 American Service personnel were ashore during daylight hours. Amphibious Group 3’s ships had been cargo loaded to operate as a sea base instead of building a supply base on shore. This enhanced efficiency in moving cargo from ship to shore and reduced the American footprint. Many of the relief supplies were flown into Chittagong, a port city/distribution point, by Air Force and Special Operations Command C-130s. Throughout the operation, helicopters departed the Tarawa early and flew into Chittagong, where helicopter crews received their mission assignments. These had been shaped to fully utilize helicopter flight time and avoid loiter or hover time. The CH-46s and CH-53s principally flew bulk loads of foodstuffs—rice, potatoes, lentils, dry molasses, flour, and wheat, but also equipment, like water purification systems, and people, including very important persons (VIPs) such as Bangladeshi government officials, nongovernment workers, relief teams, and media.

To minimize loading and unloading time, supplies were sling-loaded (carried externally underneath the helicopters). UH-1Ns flew into the smaller zones, direct to those most in need; people were often stranded on rooftops and paddy dikes. Villagers shouted, “Faresta, faresta”—angel in Bengali, as helicopters hovered down with desperately needed supplies. Downtime associated with aircraft refueling and replenishment was minimized by stationing two amphibious ships, USS Barbour County (LST 1195) and USS Frederick (LST 1184), close to shore, indeed in only 10 meters of water. Both ships’ crews went all out, expediting aircraft servicing. Marine air crew dined on Navy box lunches while their aircraft were serviced.34

On 29 May, after two weeks, 5th MEB was relieved by the smaller CMAGTF 2-91. The 5th MEB had stabilized the situation and saved numerous lives. MAG-50 aircraft flew 1,167 sorties in 1,147 flight hours as they safely delivered 5,485 passengers to their destinations and 695 tons of relief supplies. It was another validation of the total force concept. Marine Reservists of Marine Heavy Helicopter Squadron 772 (HMH-772) flew the MEB’s CH-53s.

Operation Sea Angel was a cogent display of the Navy-Marine Corps team that featured flexibility and adaptability to accomplish pop-up missions of great size and consequence. It was an expansive and high-visibility operation. It demonstrated American goodwill through the efforts of its service personnel, who worked ardently and delayed their homecoming to save thousands in Bangladesh.

Capt Wayne Miller, a Boeing Vertol CH-46 Sea Knight helicopter pilot, speaks with local residents after delivering humanitarian relief and supplies during Operation Sea Angel. Photo by SSgt Val Gempis, RG 330 Records of the Secretary of Defense, Combined Military Service Digital Photographic Files, 1982–2007, NARA

Operation Sea Angel, coming on the heels of a combat deployment, when the Marines could have resented a delay on the way home (indeed nongovernment organizations were concerned that combat Marines might cause trouble), found the experience truly rewarding and humbling. An estimated 30,000 people were saved. Colonel West reported that on one mission, as he flew a load of supplies to isolated villagers, the village chief expressed his gratitude by “clasping his hands together and nodding with tears.” Later, the chief passed a note to West that said that a baby born that day had been name Faresta as a perpetual reminder of the American angels that brought them aid in their time of need. The success of Sea Angel modeled successful humanitarian operations, a template followed in operations later in the decade. General Stackpole noted that when Joint Task Force Sea Angel left Bangladesh, “the crops were growing and the trees had sprouted leaves . . . and there was life in the area.”35

Operation Fiery Vigil

On 7 June 1991, Mount Pinatubo, a long dormant volcano on the Philippine island of Luzon, blasted a shot of smoke and ash 6.4 kilometers high into the atmosphere. Rumblings and gaseous effusions occurred until 15 June, when a massive, earth-shaking eruption occurred. Coinciding with Pinatubo’s blast, Typhoon Yunya arrived and whipped Luzon with rain and wind. The double blows blacked out the sun and dropped a blizzard of slimy ash on the island, which accumulated a foot deep in places. Aircraft approaching Luzon saw a massive slick miles from land of what appeared to be white paint on the ocean’s surface. Mount Pinatubo’s ash accumulated on buildings and aircraft hangars such that many of them collapsed under the weight.36

HMM-364 CH-46E Sea Knight helicopters combat swirling ash as they attempt to land on base in the aftermath of Mount Pinatubo’s eruption in the Philippines. The volcano, which had erupted for the first time in more than 600 years, forced the U.S. military to coordinate Operation Fiery Vigil evacuation efforts to remove more than 20,000 evacuees from the area. Photo by SSgt Ron Alvey, RG 330 Records of the Secretary of Defense, Combined Military Service Digital Photographic Files, 1982–2007, NARA

As a result of Pinatubo’s eruption, the United States set up an expansive relief effort called Operation Fiery Vigil, a joint evacuation operation to rescue Americans and dependents on Luzon, especially at hard-hit Clark Air Base. Less than 16 kilometers from Pinatubo, the base was in danger of meeting Pompeii’s fate. Eventually, about 21,000 American military personnel and their dependents were evacuated from Luzon in a massive exodus during which the Navy-Marine Corps team played a key role.

The 15th MEU(SOC), commanded by Colonel Terrence P. Murray, had just completed an amphibious exercise on Iwo Jima and was headed for liberty in Hong Kong when it was diverted for Operation Fiery Vigil. It established an air evacuation center on the Philippine island of Cebu. The Marine Medium Helicopter Squadron 163 (HMM-163), the 15th MEU’s ACE, along with an air traffic control detachment, went ashore at Cebu. The USS Peleliu (LHA 5) sailed to Subic Bay to take on evacuees. After returning to Cebu, HMM-163 pilots ferried the more than 6,000 evacuees ashore.37

Marine Aircraft Group 36 (MAG-36), based on Okinawa, also responded to Pinatubo’s hellish fury. Lockheed Martin KC-130s of VMGR-152 took station over the Philippine and South China Seas to aerially refuel tactical jets fleeing Luzon. Included in this exodus were Marine Fighter Attack Squadron 122 (VMFA-122) flying McDonnel Douglas F/A-18 Hornets, and Marine All-Weather Fighter Attack Squadron 332 (VMA[AW]-332) flying Grumman A-6 Intruders. The KC-130s also flew Marines and supplies into Cubi Point to support the relief effort. Ash accumulation on Cubi Point’s runways prevented any aircraft larger than KC-130s from operating there. The KC-130 pilots had to kill the engines immediately on landing to prevent ash inhalation and damage to the engines.38 Marine Light Helicopter Squadron 776 (HML-776), flying UH-1s, distributed in excess of 90,000 pounds of food to Philippine citizens isolated by mudslides.

The carrier USS Midway (CV 41) served as a sea base for MAG-36 relief operations. This included a detachment from Reserve CH-53 squadron Marine Heavy Helicopter Squadron 772 (HMH-772), commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Ronald J. Fuhrmann. A detachment from Marine Aviation Logistics Squadron 36 (MALS-36) and 114 Marines from the 9th MEB were also on the Midway. Fuhrmann’s five Super Stallions flew tons of relief supplies to the Midway before it sailed for the Philippines. Once off the coast of Luzon, HMH-772’s CH-53s shuttled people, goods, and supplies between the Midway and the USS Abraham Lincoln (CVN 72), also diverted to the Philippines. Thousands of evacuees boarded the carriers at Subic Bay, hot, dirty, thirsty, and hungry. They were fed and cared for—sailors and Marines even gave up their beds for the evacuees—and after two days sailing, they arrived off Cebu. The evacuees were moved to shore, many flown in HMH-772 helicopters, which flew nonstop for 13 hours.39

Marine mechanics Sgt Becerra and LCpl Shute guide a crane driver as he positions a new propeller on a Marine Aerial Refueler Transport Squadron 352 (VMGR-352) Lockheed Martin KC-130 aircraft as part of an engine replacement. Marine aircraft mechanics often had to perform complex and sophisticated aircraft maintenance operations in expeditionary and/or hostile conditions. Photo by Cpl M. A. Butler, RG 330 Records of the Secretary of Defense, Combined Military Service Digital Photographic Files, 1982–2007, NARA

Operations Distant Runner and Support Hope

The 11th MEU(SOC), on station in the Indian Ocean and conducting Operation Quick Draw, the extraction of U.S. forces from Somalia, received orders on 8 April 1994 to conduct an NEO in Rwanda. In April 1994, genocidal tribal warfare, Hutu against Tutsi, suddenly broke out. The slaughter was immense, if not unprecedented. By the end of the fighting in July 1994, the death toll approached 1 million. This was not large-scale industrialized warfare but neighbor-against-neighbor slaughter, often by machete. The U.S. government responded quickly, although minimally (Somalia-type mission creep was a great fear) to protect Americans and third-party nationals.

Leaving behind part of the expeditionary unit to support Somali operations, the main part of the 11th MEU rapidly sailed south. On 9 April, helicopters from the 11th MEU(SOC)’s ACE, the composite squadron, HMM-163 (Reinforced), commanded by Lieutenant Colonel William D. Catto, flew 330 Marines of Battalion Landing Team 2/5 from amphibious ships to Mombasa, Kenya. Here, they boarded three CH-53Es and KC-130s of VMGR-352 for the 636-mile flight into Bujumbura International Airport, Burundi.

The VMGR-352 detachment, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel J. Pete Donato, was already in Mombasa supporting Somali operations. The KC-130s and the CH-53Es gave the long-haul ability to get Marines in place to secure the evacuation site. Maintenance Marines in VMGR-352 worked feverishly to get their aircraft ready for this added mission, including replacing an aircraft engine and cracked turbine in only 4 hours instead of the standard 24. The KC-130s and CH-53Es flew the Marines to Burundi, where they established a safe site for the evacuation of what turned out to be more than 200 civilians. American and other third-party civilians had exited Rwanda, escaping what they described as the “most basic terror.” They were convoyed to neighboring Burundi led by American Ambassador, David P. Rawson, who shut the doors on the embassy in Rwanda. The proximity of Marines deterred Hutus who might otherwise interfere with Rawson’s convoy. As he said, Marines close by were “immensely significant . . . and made it possible to get the cooperation needed.” This insertion of Marines into Burundi represented the most distant extension of a Marine sea-based unit inland at that time. Ultimately, the civilians were flown out of Burundi by U.S. Air Force C-141s.40

Operations Assured Response and Quick Response

Beginning in 1996, violence spurred by tribal and political factions roiled West Africa. At the behest of the National Command Authority, MAGTFs conducted a series of contingency operations in the region to protect American citizens and interests. This included operations in Liberia, the Central African Republic, Sierra Leone, Zaire, Eritrea, Congo, and Kenya.

Fighting had wracked Liberia spasmodically since Marines had departed in 1991. In the spring of 1996, it flared into intense, sustained violence that threatened American citizens and engulfed the capital of Monrovia and the American embassy where Americans had fled to escape danger. The American ambassador recalled phone calls he received from endangered Americans: “I mean you would hear the Americans actually screaming over the phones, begging for help. You could hear over the phones of people breaking in, pulling back the steel bars that they had, using sledge hammers to smash down the doors.”41

Again, the request for help went out and the State Department authorized an evacuation: Operation Assured Response. The first forces to Liberia were from the Special Operations Command, Europe, which arrived in Monrovia on 9 April 1996. They began evacuations, often under fire, of American citizens and third-party nationals. Rebels persistently fired small arms or rocket-propelled grenades at the embassy. Evacuees were flown by special operations helicopters from Monrovia to Lungi International Airport in Sierra Leone. The commander-in-chief, European Command, wanted to ensure the safety of the special operations forces, therefore the 22d MEU(SOC), commanded by Colonel Melvin W. Forbush, in the Mediterranean, sailed at best speed for Monrovia. It not only served as backup for special operations forces, it also was tasked to ensure the embassy’s security and conduct NEOs as required.42

Ongoing Mediterranean commitments, however, did not go away, and the 22d MEU’s ARG was divided, or disaggregated. Three amphibious ships bearing most of Battalion Landing Team (BLT) 2/2 and the MEU’s ACE, HMM-162 (Reinforced), were sent to Mamba Station, arriving on 18 April 1996. The 22d MEU’s standby detachment of KC-130s of VMGR-252 made logistics flights into neighboring Sierra Leone. Once the 22d MEU was on station, Joint Task Force Assured Response was turned over to Forbush.43

Two days after arrival, HMM-162 (Rein) helicopters flew Marines into the embassy, where they established security. The situation in Monrovia had grown noticeably worse since the 1990–91 NEOs. Now, fighters approached Marine positions at will. They were defiant and condescending, they “flipped the bird” at Marines and pointed their weapons threateningly. There was more fighting. HMM-162 (Rein) aircraft flying from their sea base, like predecessor squadrons, flew logistics flights to support the embassy and Marines on shore. They also conducted evacuations, although since the arrival of the Marines, who were a stabilizing influence, the number of Americans seeking evacuation had declined. During the two months the 22d MEU was in Liberia, 49 Americans were evacuated. By June, the situation had been neutralized such that a force of Nigerians serving as peacekeepers assumed security duties.44

Even while conditions in Liberia intensified, civil war erupted unexpectedly in the neighboring Central African Republic. This put the security of the American embassy and the safety of American citizens in peril. Colonel Forbush, whose expeditionary unit had already been divided, was now directed by European Command on 20 May to peel off another segment of the MEU and send it to Bangui, the Central African Republic’s capital. It was to secure the embassy there (it had no permanent security guards on staff) and prepare to evacuate Americans. Forbush designated the 81mm platoon of BLT 2/2’s weapons company for the mission, supplemented with Marines from the MEU’s service support element. Bangui was 321.9 kilometers inland from the ARG. To get the 35 Marines to Bangui, Forbush relied on his detachment of KC-130s of VMGR-252.45

Every MEU(SOC) had a detachment of KC-130s assigned and on a 48-hour alert, ready to respond to contingencies as the unit commander saw fit. In the African operations in the mid-1990s, they proved essential for moving logistics long distances, such as from Rota, Spain, to Dakar, Senegal, and Sierra Leone. In the case of the Central African Republic, they were essential for moving Marines deep inland.

Marines of the 22d MEU(SOC) are inserted at the U.S. embassy in Liberia by HMM-162 CH-46 Sea Knight helicopters during Operation Assured Response. Photo by Cpl A. Olguin, RG 330 Records of the Secretary of Defense, Combined Military Service Digital Photographic Files, 1982–2007, NARA

When the 22d MEU was alerted to the mission, Operation Quick Response, its KC-130 detachment, commanded by Major John T. Collins, was in Rota, Spain, undergoing training and was alerted to the contingency. With little information other than to fly toward Sierra Leone, 4,828 kilometers away, on 20 May, pilots Captains David A. Krebs, Homer W. Nesmith, and Robert A. Boyd and a crew of eight Marines took off from Rota. The flight crew had been augmented because the flight would extend past a normal crew day. Additional instructions would be provided as they flew toward Sierra Leone. Stopping at Freetown, Sierra Leone, the crew refueled and received a map and airfield approach information for Bangui—a strong clue of their destination.

In the meantime, the security team of BLT 2/2 had been flown by CH-53Es to Freetown, Sierra Leone’s airport. Here, they waited for the arrival of Krebs’s KC-130, which arrived at 2000. On the ground at Sierra Leone, a satellite communications system was installed in the KC-130 and, after refueling, it took off with Marines of BLT 2/2 aboard. Overflight restrictions of some West African nations forced them to fly additional miles along the coast.

They received clearance to fly inland over Cameroon and into the Central African Republic. Approaching to land in predawn darkness over Bangui, the KC-130 crew watched tracers from small arms lace over the city. As they rolled out on the runway, they saw fighting positions, manned by French troops and civilians awaiting evacuation. Immediately, the Marine mortarmen went to the embassy and secured it. Others began processing evacuees while KC-130 crew unloaded pallets of much-needed bottled water. The evacuees, mostly missionaries and Peace Corps volunteers, 13 in all, were processed and loaded aboard the KC-130. They were extremely pleased to see Marines. Once loaded, the KC-130 took off, heading to Cameroon. By the time they landed and shut down at Yaounde, Krebs and crew had been operating for 36 hours, which included 18.3 hours in flight.46

The KC-130s of VMGR-252 that followed in subsequent days were the main means of escape for Americans out of the Central African Republic during Operation Quick Response, which lasted until 1 August. More than 400 civilians, including 190 Americans, were flown out on the Marine Hercules aircraft.47

Almost as soon as the 22d MEU began supporting Operation Assured Response, high-level command wanted it back in the Mediterranean because of the ongoing ethnic tensions in southeastern Europe. With no extra MEUs available (the other two East Coast-based MEUs of the 2d Marine Expeditionary Force had standard rotation dates that could not be adjusted), commanders authorized a special-purpose Marine air-ground task force (SPMAGTF) to assume the West African contingency. Ground troops to form the battalion landing team came from the 8th Marine Regiment. The 8th Marines’ commander, Colonel Tony L. Corwin, was given command of the SPMAGTF. The task force’s aviation combat element was comprised of two CH-53Es and two UH-1Ns, from Marine Heavy Helicopter Squadron 461 (HMH-461) and Marine Light Attack Helicopter Squadron 167 (HMLA-167), respectively. Personnel from Marine Aviation Logistics Squadron 26, Marine Wing Support Squadron 272, and Marine Air Control Squadron 2 were added.48

The aviation combat element was assigned to the USS Ponce (LPD 15), even though it was not built to handle a contingent of aircraft and associated equipment. The Ponce also lacked precision-approach control and weather forecasting equipment. Also, once the maintenance vans were loaded aboard, it only had room for a single helicopter at a time to operate on its deck. Nevertheless, loading the Marine detachment was planned to begin on 12 June.49

Capt David Krebs stands with his KC-130 crew after a marathon 36-hour flight from Rota, Spain, to Bangui, Central African Republic, where they rescued Americans from a threatening situation. Crewmen (left to right): Capt Homer Nesmith, Krebs, Cpl Heeringa, Cpl Biery, Sgt Nave, CWO-5 Larry Ross, SSgt Matt Davis, Capt Rob Boyd, Sgt Janzen, Cpl Hansen, and GySgt Reid Henderson. Photo courtesy of Capt David Krebs, USMC

This plan, however, was short-stopped by the grounding of all CH-53s due to a suspected defective duplex bearing in the main rotor swash plates. Therefore, on 11 June, the day before loading was to commence, HMM-264, only recently returned from a six-month deployment, were directed to send four of their CH-46s with pilots and support personnel as replacements for the CH-53s. Lieutenant Colonel Eugene A. Conti, HMM-264’s commander, became the ACE commander. The pilots and crews of HMM-264 had little time for planning or preparing—indeed the Ponce sailed in less than three days.50

Briefings, training, and meetings were conducted on the trans-Atlantic voyage. The transport aircraft of VMGR-252 flew the advance party of the task force to Sierra Leone for meetings with the 22d MEU’s staff. On 27 June, the SPMAGTF relieved the 22d MEU on Mamba Station. HMM-264 took up the logistics flights into the embassy in Monrovia. These proved challenging due to summertime tropical weather hazards and lack of radar on the ship or on shore. HMM-264 crews often had to transport external loads that nearly maxed out their load capacity, into a landing zone built out of a basketball court surrounded by a high fence next to a cliff. Additionally, they flew into Freetown, Sierra Leone, which was a central transportation/logistics hub as it was the closest airfield from which C-130s could operate. The helicopters were the link between Freetown and the Ponce. On 1 August, after Monrovia was calm and stable for a sufficient period, the State Department recommended that evacuation status be lifted from Liberia. On 3 August 1996, Joint Task Force Assured Response ended, and the next day, the SPMAGTF departed Mamba Station. During the contingency, the six aircraft of HMM-264 transported 1,800 passengers and 500,000 pounds of cargo without incident.51

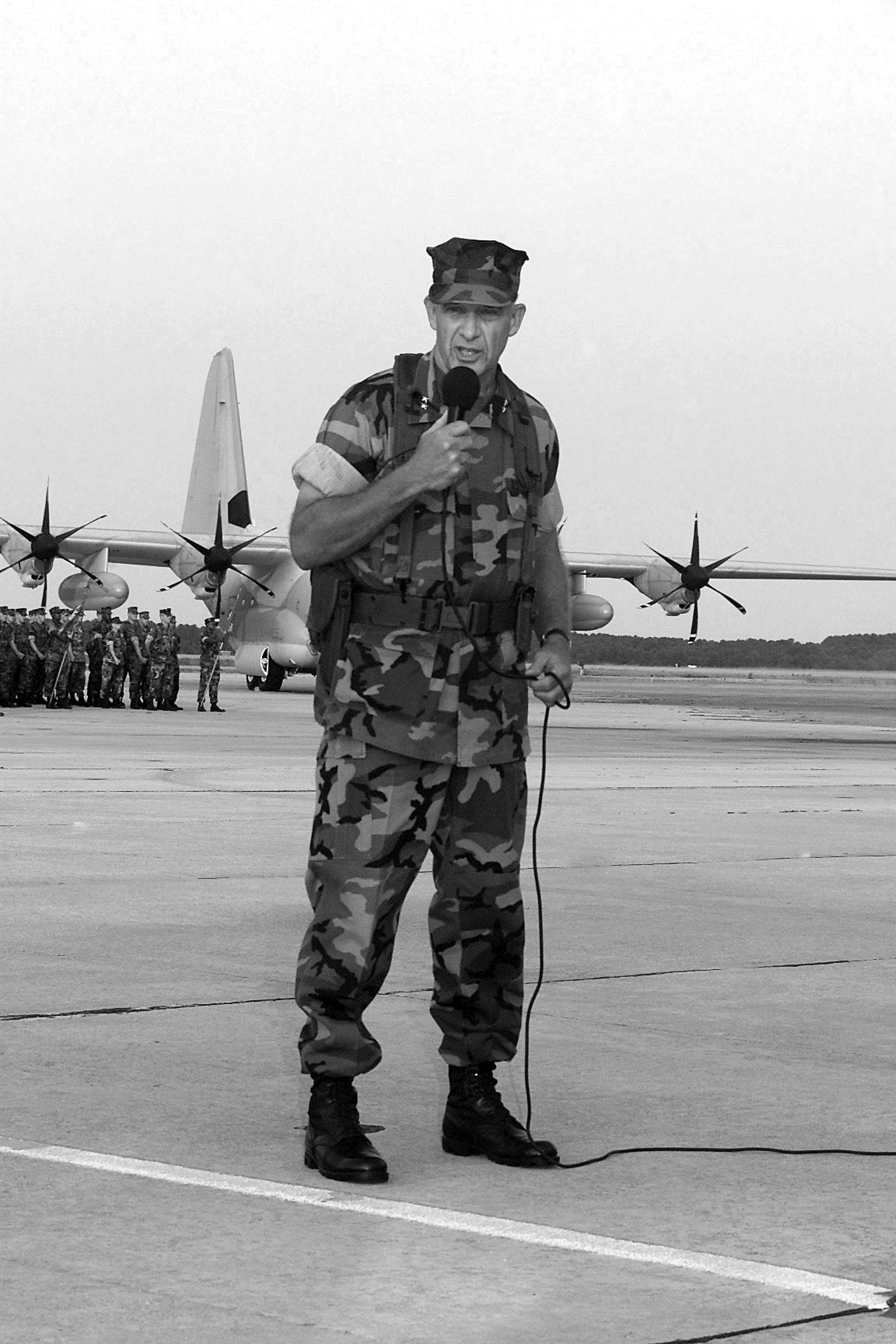

Col Tony L. Corwin, commanding officer of Special Marine Air-Ground Task Force (SPMAGTF) Liberia, addresses troops two days prior to landing in Liberia. Photo by Cpl A. Olguin, RG 330 Records of the Secretary of Defense, Combined Military Service Digital Photographic Files, 1982–2007, NARA

Operations Silver Wake and Guardian Retrieval

The calls on MEUs to rescue Americans and innocents from political turmoil in Africa and Europe did not decrease in the later years of the 1990s; MEUs now sailed from North Carolina fully expecting a real-world contingency to occur. Colonel Emerson N. Gardner, commanding the 26th MEU(SOC), certainly did and he was not disappointed. The 26th MEU(SOC) headed for the Mediterranean in November 1996.

Early in 1997, events in Albania captured Gardner and his staff’s attention. Formerly Communist, Albanians, unfamiliar with capitalism, risked all in a financial pyramid scheme and subsequently lost it. They blamed their pro-capitalist government for the meltdown and social turmoil followed. Gardner’s expeditionary unit prepared for action.52

Predictably, a warning order from the National Command Authority came on 7 March 1997 to Gardner: standby for an Albanian contingency. With scheduled and mandatory port calls in the offing that would displace the MEU uncomfortably far from Albania, Gardner took action that would allow a quick response if an Albania contingency became required.53

A detachment of helicopters (four CH-46Es and two AH-1Ws) from the 26th MEU’s ACE, HMM-365 (Reinforced), commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Jon T. Hardwick, was cross-decked to the USS Nashville (LPD 13), along with 72 Marines. This detachment was placed under the command of the MEU’s executive officer, Lieutenant Colonel Daniel F. Tarpey Jr. Instead of going into Malta with the rest of the expeditionary unit, the Nashville went into port at Zakynthos, Greece, only 193 kilometers from Albania. The USS Nassau (LHA 4), with the bulk of Gardner’s 26th MEU aboard, commenced its port call in Malta.

On 13 March 1997, Gardner received word from the National Command Authority: execute an evacuation of Americans and third-party nationals from Albania. With the Nashville stationed close to Albania, HMM-365 (Rein) helicopters were able to launch immediately, at night, to get Marines into the American embassy in Tirana, where they established security, began processing evacuees, and stood up a forward command element.54

Darkness gave a measure of security but increased the flight hazards, as Tirana had mountains on three sides and trees uncomfortably close to the landing zone. Most startling to the pilots, though, was the volume of small-arms tracers that streaked through the night sky. It was not necessarily directed at their aircraft; social order had simply broken down and Albanians who had looted well-stocked armories fired away. Indeed, Albanians were at considerable peril simply from the falling bullets. The Marines were amazed at how quickly the veneer of civilization came down.55

Four CH-46Es with Lieutenant Colonel Daniel E. Cushing flying the lead aircraft carried the forward command element and a security team to Tirana escorted by two AH-1W Super Cobras, led by Lieutenant Colonel Richard L. Crush. The sense of peril that existed in Tirana motivated the ambassador to prepare 51 Americans, mostly women and children, for immediate evacuation. Marines loaded them onto the CH-46s and whisked them that night to the Nashville. High above, American strike-fighters patrolled, ready to deliver air support if needed. Marine All-Weather Fighter Attack Squadron 224 (VMFA[AW]-224), flying McDonnell Douglas F/A-18D Hornets from their Aviano, Italy, base, were likely the first tactical jets overhead. Also coming from Aviano with tactical electronic support were Northrop Grumman EA-6B Prowlers of Marine Tactical Electronic Warfare Squadron 3 (VMAQ-3), which continued to provide electronic warfare support to Silver Wake operations through 24 March.56

American citizens are escorted to a CH-46E Sea Knight helicopter by a 26th MEU(SOC) Marine during Operation Silver Wake. The 26th MEU(SOC) was called on to perform a noncombatant evacuation operation (NEO) of U.S. citizens that desired to leave Albania due to civil strife. Photo by Sgt Mark D. Oliva, RG 330 Records of the Secretary of Defense, Combined Military Service Digital Photographic Files, 1982–2007, NARA

The next day, the Nassau arrived carrying the rest of the 26th MEU. Evacuations began in earnest with an early launch of eight CH-46s and three CH-53s, with Lieutenant Colonel Hardwick as mission commander. The transports roared into the landing zone at the Relindja Ridge housing complex near the embassy and began loading civilians. Hardwick employed a “spider web” routing, multiple routes in and out of the landing zone for the helicopters. This facilitated a rapid build-up of combat power and made the flight paths less predictable and thereby less vulnerable to ground fire.57 The countryside was dotted with gun positions, little concrete emplacements. While Harriers patrolled high overhead, Cobras and UH-1Ns equipped with .50-caliber machine guns, escorted the transport helicopters. The UH-1N crews paid close attention to the igloo gun sites.

As Cobra pilot Captain Ron L. Pace passed over a gun position, he watched a man shoulder what appeared to be an SA-7 (man portable antiaircraft missile) and point it at his Cobra. Responding immediately, Pace fired a burst from his 20-mm cannon at the gunner.

In another incident, a Cobra gunship took fire from a machine gun; one round struck the Cobra. The pilot, Captain Jon M. Hackett, responded by firing 2.75-inch rockets at the gun position. That stopped the fire. After this, the men on the ridge waved white flags when the Cobras flew by. Lieutenant Colonel Cushing noted the importance of gunships for contingency missions:

We don’t come in as policemen. We come in as war fighters. Throughout the world that is our reputation. That is the reputation we presented in Albania, and no one messed with us, and the one person that did, regretted it. The Cobra is again, a powerful platform for escort capability. We went back to the old business of using UH-1s as gunships, and they were very successful in what they did. They carried a 7-shot rocket pod and .50 cals. We were able to use them at escort the entire time, and they were intimidating. We had no problems after the first few days. People realized we were serious about our business.58

In the middle of the Albanian evacuation, the 26th MEU was alerted to another possible evacuation requirement—Operation Guardian Retrieval—in civil war-ravaged Zaire. American lives were once again threatened. The U.S. European Command’s Southern Task Force deployed a special operations contingent to Brazzaville, Republic of Congo, which sat across the Congo River from Kinshasa, Zaire, to prepare for an evacuation. This force was at the end of a long and tenuous supply line. The European Command needed Gardner’s 26th MEU to relieve the special operations force and provide sustained security. It would also be available to execute an evacuation if needed. Because the Albanian evacuation continued, the ARG that supported Gardner’s 26th MEU was split. Leaving the Nashville behind with four CH-46s, two UH-1Ns, and a contingent of Marines to continue the Albanian operations, the bulk of the expeditionary unit sailed on 23 March 1997 for the Congolese coast, about 5,200 miles away.59

American citizens buckle into a CH-46E Sea Knight helicopter from 26th MEU(SOC) for transport out of Tirana, Albania, during Operation Silver Wake. Photo by Sgt Mark D. Oliva, RG 330 Records of the Secretary of Defense, Combined Military Service Digital Photographic Files, 1982–2007, NARA

Gardner mobilized the VMGR-252 KC-130s to fly into Brazzaville well ahead of the expeditionary unit’s arrival. Staging out of Libreville, Gabon, this reduced the Marine response time to a matter of days. The KC-130 detachment stood ready to fly in equipment, supplies, and personnel. In this case, and in many contingencies in Africa in these years, Marine KC-130s spearheaded American responses to crisis situations. They often arrived to an unknown and tense situation in which law and order was tenuous at best and the only force protection was their own crew.60

As the Nassau plowed toward Simba Station off Congo’s coast, passing Sicily, two Sikorsky MH-53E Sea Dragons from Navy Helicopter Combat Support Squadron 4 (HC-4) joined the ACE to bolster its long-range heavy-lift capability. Kinshasa was 321.9 kilometers deep into Congo. This distance made Guardian Retrieval especially dependent on the 26th MEU’s aviation assets. Again, as in Eastern Exit and Distant Runner, it was the KC-130s and CH-53s that offered the potential to reach deep inland to provide a quick build-up of combat power and commence security operations or evacuations of vulnerable civilians.61

An intermediate staging base/logistics hub was established at Pointe-Noire on the Congo coast, in easy range for helicopters operating from the MEU’s ships and its runway useable by KC-130s. Marines of the 26th MEU also established a forward area arming and refueling point at the Brazzaville airport that would be of critical importance in the instance that a NEO was required.

Colonel Gardner chose to keep only a minimal contingent of troops and aircraft in Brazzaville largely because of the malaria danger as well the embassy’s request to minimize the military presence. There was already a sizeable contingent of troops present in Brazzaville, including troops from Belgium, Britain, and the United States. Nevertheless, now Gardner’s MEU had been divided three ways with the force in Albania, a contingent off the coast of Congo, and a small contingent in Brazzaville, which included Gardner and his command element. To maintain communications, an early use of the Joint Task Force Enabler provided a communications suite that greatly enhanced the ability to communicate globally. II MEF had received Joint Task Force Enabler communications gear immediately prior to the 26th MEU’s deployment, and it was pressed into use for these contingencies.62

Anticipating conducting a NEO, 26th MEU planned, practiced, and trained with a number of variables. One requirement bound them: the evacuation had to occur within four hours once it was ordered. The favored plan was for HMM-365 helicopters to carry troops to Pointe-Noire and KC-130s to fly them to Brazzaville. The helicopters would fly empty at the same time toward Brazzaville. This included CH-46s that had been modified to give them additional range by removing about 700 pounds of unneeded equipment and replacing it with internal fuel. At Brazzaville, the helicopters would then refuel and begin troop insertions into Kinshasa and carry out evacuees to Brazzaville. The evacuated civilians would be turned over to State Department personnel for evacuation out of the country.63

The 26th MEU arrived off Congo on 2 April and established the sea-air-land bridge into Brazzaville. The situation in Zaire, however, never developed to the point that an evacuation was required before the 26th MEU was relieved a month later by Colonel Samuel T. Helland’s 22d MEU(SOC) on board the new USS Kearsarge (LHD 1). Helland’s ACE was HMM-261, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Timothy C. Hanifen. Helland’s MEU had sailed two weeks early so it could relieve Gardner’s 26th MEU. Helland received permission to forward deploy two CH-46s, two CH-53s, and two AH-1Ws to Brazzaville for the contingency while the rest of HMM-261 remained on board the Kearsarge on a 60-minute daytime alert and 120-minute night alert.

Evacuees from Freetown, Sierra Leone, are escorted across the flight deck of the USS Kearsarge (LHD 3), on 30 May 1997, during Operation Noble Obelisk. More than 900 people from 40 different countries were evacuated. Official Department of Defense photo, VIRIN: 869836-R-EFN00-744

Marines from Marine Air Control Group 28 assisted with the air control requirement at both Brazzaville and Pointe-Noire airports; others augmented the Joint air operations staff. The desired peaceful resolution (or soft landing) of the Zaire civil war did occur. The president departed the country, and this opened the way for rebel forces to set up a new government and rename the country the Democratic Republic of Congo. Neither the 26th or 22d MEUs evacuated anyone from Congo.64 Nevertheless, they were ready to conduct evacuations despite the remote location and even while conducting another evacuation in a far distant locale.

Operation Noble Obelisk

Before the 22d MEU made it to a liberty port, however, the National Command Authority notified Helland of a coup in Sierra Leone, West Africa—formerly an oasis of calm in a sea of turmoil—that had sparked widespread violence. The situation in Sierra Leone had broken like a tropical thunderstorm, and rebels swarmed the capital city with a quick ferocity. The American embassy was threatened, endangering Americans and third-party nationals. The 22d MEU was to spearhead Operation Noble Obelisk, which turned out to be the largest NEO since the fall of Saigon. The ARG turned north and three days later, 29 May 1997, was poised 25 miles off the Sierra Leone coast. The 22d MEU’s forward command element was inserted immediately on shore to make ready for the evacuation and to provide situational awareness for fleet commanders.65

Early the next day, HMM-261 Cobras swept over the Freetown, Sierra Leone, area, looking for threats along the ingress routes and at the pick-up site, the Mammy Yoko Hotel where most of the Americans were congregated. Then the CH-46s and CH-53s roared toward the beach, flying fast and low over the water carrying Marines from BLT 1/2, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Thomas C. Greenwood, to support the evacuation. After landing, Marines established a security perimeter and Marine Air Control Group 28 provided landing zone control, while Marines from the service support group processed evacuees. Harrier jets, armed and ready, stood a 30-minute alert on board ship. Frightened men, women, and about 200 children clambered aboard HMM-261’s helicopters, all fitted with life jackets and head protection. On the Kearsarge, the evacuees were processed then again loaded onto HMM-261 CH-46s, which flew them to nearby Guinea.66 HMM-261 flew 85 sorties the first day and evacuated 900 civilians. A second evacuation on 1 June brought an additional 350 civilians, including 18 orphans from the Americans for African Adoption agency. Two days later, after fighting intensified, at least partly because of the arrival of Nigerian ships that opposed the coup and bombarded rebel positions, another evacuation was required. No longer was the hotel tenable for evacuations, and another site was selected at a beach-front restaurant 4.8 kilometers south. Two Cobras launched the evening before to reconnoiter the new objective; they saw small arms fire and mortar rounds hit the water around them as they flew over the beach.67

The evacuation commenced the next morning at 1000. A division of CH-53s led the insertion mission into the beach, followed by six CH-46s; air-cushioned landing craft delivered an armored security force of the battalion landing team’s combined antiarmor platoon and light armored-reconnaissance vehicles. Overhead, Cobras and Harriers patrolled, ready with close-air support, while KC-130s from VMGR-252 orbited higher with gas to refuel the Harriers. Two light aircraft of unknown origin approached the landing zone and were intercepted by the Harriers, but they proved to be no threat. Another 1,200 people were evacuated in this third and final evacuation out of Sierra Leone. Resistance had been defused through negotiations led by British diplomats working through the night to secure a cease-fire. About 2,500 people had been evacuated.68 Mamba Station did not see another Marine force until the new millennium.

Operation Avid Response

A powerful earthquake centered on Izmik, Turkey, cut short the well-deserved port visit to Spain of the 26th MEU(SOC), commanded by Colonel K. J. Glueck, when the Sixth Fleet commander ordered it to conduct humanitarian operations there. Glueck’s MEU had just conducted peacekeeping operations in Kosovo. The lead ship of the ARG, the Kearsarge, set course immediately for Turkey. It arrived on 23 August 1999, four days later. As with most humanitarian missions to disaster zones, the helicopters were key enablers, providing the transport capability to move people and freight rapidly, including in the most devastated regions that otherwise would be unreachable.

The ACE was HMM-365 (Reinforced), commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Cushing. The squadron supported the MEU’s earthquake relief effort by flying in equipment, personnel, and tools to build a refugee tent city at Topel, Turkey. HMM-365 also transported a large number of scientists and interested parties, including dignitaries, one of whom was Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, who came to Turkey to view the damage and offer assistance.69

Operation Stabilise

In a United Nations referendum in August 1999, East Timor, predominately Roman Catholic, voted overwhelmingly for independence from Muslim Indonesia. Indonesia had seized the formerly Portuguese colony in 1975, only nine days after it had declared its independence from Portugal. What followed was a bloody, if not genocidal, dominance over East Timor in the subsequent 24 years by Indonesia. When the East Timorese voted for independence in 1999, Indonesian soldiers and loyalist militia rampaged through East Timor. About 400,000 East Timorese fled to West Timor. In East Timor, homes, schools and businesses were burned, plumbing destroyed by stuffing toilets with cement and tar, and cities stripped of water and electricity. A call for assistance, to provide relief and protection, went out.

Uncharacteristically, the United States offered a less-than-robust response. Secretary of Defense William S. Cohen asserted that the United States cannot be the “world’s policeman.” Within the military, there was a concern about military resources being “frittered away” in seemingly unending humanitarian assistance operations. Timor’s neighbor to the south, Australia, felt otherwise. Australians remembered that in World War II, the East Timorese had remained loyal allies. Australia did not intend to ignore that act of good will and stepped forward to lead an international relief effort called Operation Stabilise.70

MajGen John G. Castellaw speaks to a crowd shortly after assuming command of 2d Marine Aircraft Wing (2d MAW), later in his career. Photo by LCpl Bryan Nealy, RG 330 Records of the Secretary of Defense, Combined Military Service Digital Photographic Files, 1982–2007, NARA

Leading the U.S. forces under this operation was Brigadier General John G. Castellaw, a CH-46 pilot who was the deputy commander of III Marine Expeditionary Force. The Western Pacific-based 31st MEU(SOC), commanded by Colonel David D. Fulton, which had just returned from an exercise in Australia, was alerted on 30 September to prepare to go to East Timor.

The commander of Marine Forces Pacific, Lieutenant General Frank Libutti, ordered the creation of a SPMAGTF to sail on the USS Belleau Wood (LHA 3) and support Operation Stabilise. This task force was organized from elements of the 31st MEU, which included an infantry company, combat service support personnel, and the entire aviation combat element, HMM-265 (Reinforced), commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Andrew W. O’Donnell Jr. The SPMAGTF and U.S. Air Force and Army contingents comprised the U.S. contribution to the coalition of international forces (International Forces, East Timor, or InterFET), commanded by Major General Peter Cosgrove of Australia.71

A displaced mother and her daughters are returned home to East Timor, courtesy of HMM-265. HMM-265 was the aviation combat element of SPMAGTF East Timor and provided three CH-46E Sea Knight helicopters that provided 44 East Timorese, like the family shown, a ride home. Photo by Sgt Bryce Piper, RG 330 Records of the Secretary of Defense, Combined Military Service Digital Photographic Files, 1982–2007, NARA

Prior to arrival of the Belleau Wood, which occurred in early October 1999, the initial flight to insert coalition security troops into East Timor’s capital, Dili, occurred on 20 September 1999. The only Marine presence in this fly-in was a KC-130 aircraft from VMGR-152, which just happened to be in Darwin as part of a training exercise. Its crew believed that something more interesting than training was in the works and sought to get in on the action. When an Air Force C-130 crew declined to fly the Dili-insert mission because they lacked personal weapons and body armor, the Marine crew volunteered. The Marines got the go-ahead to fly as part of the mission.72

The United States, ever wary of mission creep and ensnarement in a foreign commitment, carefully limited the scope of its participation to carrying relief supplies into East Timor, and this could only be done by the SPMAGTF’s four CH-53s (more CH-53s arrived later with the 11th MEU). Other ACE helicopters were not allowed to participate so as to limit American participation. Their presence on the flight deck of the mighty Belleau Wood parked 3.2 kilometers off the coast near Dili represented U.S. power and prestige. This had an intimidating effect on Indonesians who might desire to stymie security and stabilization operations.73

The work was done by the Super Stallions. Pallets of relief supplies, which included rice, seed, tools, kitchenware, fuel, and water, were loaded on the CH-53s either at Dili’s airfield or off cargo ships and flown inland where needed. Beechcraft C-12 Hurons from Marine Corps Air Stations at Iwakuni and Futenma, Japan, also flew into Dili carrying gear and supplies. While the CH-53s did the heavy hauling, CH-46s and UH-1s of HMM-165, the ACE for the 11th MEU, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Guy M. Close, also transported some cargo (out of a total of 1,530,550 pounds of cargo, the CH-53s flew 1,423,800 pounds), but their greatest utility was carrying distinguished visitors. These included Richard Holbrooke, the American UN ambassador; Robert S. Gelbard, the American ambassador to Indonesia; and Bishop Carlos Belo, the bishop of Dili (and Nobel Peace Prize winner). AH-1 and UH-1 gunships were overhead as a deterrent to those who might want to interfere with the negotiations. HMM-165’s helicopters were the first American aircraft used to transport displaced East Timorese from West Timor back to East Timor. Marines improved communications and intelligence for InterFET while others from the air control detachments augmented the central air control agency and provided landing zone control. Marines from the service and support detachments improved landing sites for helicopter operations. By February 2000, InterFET ceased operations and the UN took up the administration of East Timor. The 15th and 13th MEUs continued East Timor humanitarian operations into the following year. In September 2000, the 13th MEU(SOC) visited and executed humanitarian assistance operations in the Oecussi Enclave (in West Timor), an area that had been especially ravaged in the September uprising.74

During Operation Stabilise, relations with Australians remained superb. Operation Stabilise set East Timor on the road to independence, which occurred in 2002. In the intervening years, Marine expeditionary units from Camp Pendleton, California, regularly conducted humanitarian operations in East Timor, highlighting their flexibility and utility delivering aid and providing security and stabilization, capabilities that would be of great utility in the next decade.75

Conclusion

The decade of the 1990s began with Operation Sea Angel and ended with Operation Stabilise, both large-scale humanitarian operations conducted by MAGTFs. In between were several operations in which the Navy-Marine Corps team rescued Americans and many civilians of other nations from violence due to political upheavals or from natural disasters. The Navy-Marine Corps team provided aid and emergency services of all sorts and often on short notice. This accounting highlights only a select few that show the utility of the Navy-Marine Corps team for humanitarian operations in support of the national security strategy—largely carried out by aviation elements and primarily by helicopters. The MAGTF’s aviation element, by swiftly and capably bridging the distance between land and sea and by providing both life-saving transport and defense against land-based weapons, was essential for the performance of MOOTW. Only rarely did Marines engage in direct combat during these operations, however, they always stood ready to do so. In many cases, the arrival of Marines prevented or deescalated conflict, which no doubt would have led to human-caused disasters. In the final analysis, it is ironically apparent that although the Navy and Marine Corps team was created and exists to fight, destroy, and kill, in the 1990s it saved many more lives than it had ever taken.

•1775•

Endnotes

- Douglas E. Nash, “The Afloat-Ready Battalion, Marine Corps History 3, no. 1 (Summer 2017): 75–77, 81; and Marine Corps Order 3120.3, The Organization of Marine Air-Ground Task Forces (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, 27 December 1962).

- The Fifth Fleet is basically the naval component command of Central Command, which is in the Middle East and includes the Persian Gulf, Arabian Sea, Red Sea, and part of the Indian Ocean. The Sixth Fleet is responsible for the Mediterranean Sea and Black Sea; and the Seventh Fleet is responsible for the Western Pacific and east to the Pakistan/India border, and from the Kuril Islands to Antarctica.

- Stephen Knott, “George H. W. Bush: Foreign Affairs,” University of Virginia Miller Center, accessed 4 January 2024.

- Francis G. Hoffman, “Stepping Forward Smartly: ‘Forward . . . from the Sea,’ The Emerging Expanded Naval Strategy,” Marine Corps Gazette 79, no. 3 (March 1995): 30–31.

- Thomas F. Qualls Jr., “MAGTFs and Adaptive Naval Expeditionary Force Packages: Operational Masterpieces or Failures?” (diss., Naval War College, 1994), 3–4.

- Anthony C. Zinni, “Forward Presence and Stability Missions: The Marine Corps Perspective,” Marine Corp Gazette 77, no. 3 (March 1993): 57–58; and Sean C. O’Keefe, Frank B. Kelso, Carl E. Mundy Jr., “. . . From the Sea: A New Direction for the Naval Services,” Marine Corps Gazette 76, no. 11 (November 1992): 19–20.

- Indeed, the largest of the humanitarian operations of the decade, Operations Provide Comfort (Northern Iraq) and Restore Hope (Somalia) will not be covered as they have already received considerable public and academic attention. Eighteen major humanitarian operations occurred in the 1990s, only three of which were in the United States. “Selected Marine Corps Humanitarian Operations: 1970 to 2007,” Marine Corps Humanitarian Operations, Marine Corps History Division, accessed 25 January 2024. The noncombatant operations that occurred in the 1990s are not listed.

- Eric Edi, “Pan West Africanism and Political Instability in West Africa: Perspectives and Reflections,” Journal of Pan African Studies 1, no. 3 (March 2006): 7, 14.

- Gardner’s squadron, as was common with MEU ACEs, was a composite squadron. Added to the basic squadron’s 12 CH-46s were 4 Sikorsky CH-53 Sea Stallions, 2 Bell UH-1N Hueys, 4 Bell AH-1W Super Cobras, and 6 McDonnell Douglas AV-8B Harriers.

- 22d MEU Command Chronology (ComdC), 1 July–31 December 1991 (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps History Division), pt. 2, 5–6, and enclosure 1, 1. An ARG was composed of Navy amphibious ships, usually three or four, which held the MEU.

- SSgt John Lavailee, “NCOs Keep Workhorses Flying MEU,” Wind Sock, 9 August 1990.

- Maj James G. Antal and Maj R. John Vanden Berghe, On Mamba Station: U.S. Marines in West Africa, 1990–2003 (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 2004), 17–18.

- Antal and Berghe, On Mamba Station, 15.

- Antal and Berghe, On Mamba Station, 23.

- LtCol Stephen J. Labadie, interview with Benis M. Frank, 1990, transcript (Oral History Collection, Marine Corps History Division [MCHD], Quantico, VA), 17, hereafter Labadie interview; LtCol Warren T. Parker interview with Benis M. Frank, 1990, transcript (Oral History Collection, MCHD, Quantico, VA), 9; and Antal and Vanden Berghe, On Mamba Station, 25–27.

- Antal and Berghe, On Mamba Station, 25–31; and Capt Michael T. Cariello, interview with Benis M. Frank, 1990, transcript (Oral History Collection, MCHD, Quantico, VA), 6.

- Antal and Berghe, On Mamba Station, 27–30.

- Labadie interview, 16. A climb was required because the embassy was built on a peninsula high above the water. This made for a nice change from the normal tension-wrought approach to a possibly hostile landing zone in which helicopters descended into the zone, slow, predictable, and vulnerable. The embassy approach was protected until the last seconds when the pilots popped their birds up and settled in the zone.

- Antal and Berghe, On Mamba Station, 38–40.

- 22d MEU ComdC, 1 July–31 December 1991, enclosure 1, 7–8.

- Antal and Berghe, On Mamba Station, 44–45.

- BGen Edwin H. Simmons, “Getting Marines to the Gulf,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 117, no. 5 (May 1991): 59; and Antal and Berghe, On Mamba Station, 54.

- Maj Daniel P. Johnson, interview with Meredith P. Hartley, 1991, transcript (Oral History Collection, MCHD, Quantico, VA), 4–7, hereafter Johnson interview.

- Johnson interview, 1; and Antal and Berghe, On Mamba Station, 60.

- Johnson interview, 13–14.

- Antal and Berghe, On Mamba Station, 60–63.

- Gen Carl E. Mundy Jr., interview with BGen Edwin H. Simmons, 2000, transcript (Oral History Collection, MCHD, Quantico, VA), 237, hereafter Mundy interview. Simmons and Mundy called this operation one that would not end.

- Antal and Berghe, On Mamba Station, 63.

- Charles R. Smith, Angels from the Sea: Relief Operations in Bangladesh, 1991 (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1995), 14, 20–21.

- Smith, Angels from the Sea, 15–18, 45–47. Although ordered home on the 7th, the MEB did not actually exit the Persian Gulf until 10 May. Operation Desert Storm was over and U.S. forces were retrograding; 5th MEB was supporting the retrograde and was on stand-by to conduct a possible NEO in Ethiopia. In early May, this contingency seemed less likely, so the 11th MEU and associated amphibious ships were detached from 5th MEB and left to cover the Ethiopian contingency and support the retrograde.

- Smith, Angels from the Sea, 18.

- Smith, Angels from the Sea, 22–24, 45, 61.

- Smith, Angels from the Sea, 36. The Air Force flew Lockheed C-141 Starlifters and C-130s into Bangladesh, bringing in earliest contingents of soldiers and support staff. MAG-50 also had Harrier jets from VMA-513. The transport helicopters in MAG-50 came from HMM-265 (CH-46Es), HMLA-169 (UH-1Ns), and HMH-772 (Detachment A) (CH-53Ds) a Reserve squadron. Additionally, there were two Navy Sikorsky SH-3H Sea King helicopters as part of Amphibious Group 3.

- Smith, Angels from the Sea, 61–62; and LtGen Henry C. Stackpole III lecture at U.S. Marine Corps Historical Center, Washington, DC, 30 January 1992, transcript (Oral History Collection, MCHD, Quantico, VA), 11, hereafter Stackpole lecture.

- Stackpole lecture,16–19; and Smith, Angels from the Sea, 38, 62, 76–77. CMAGTF 2-91 had about 240 Marines and sailors and one amphibious ship; surface craft from Amphibious Group 3 delivered another 1,450 tons of relief supplies.

- Marine Medium Tiltrotor Squadron 364 (HMM-364) ComdC, 1 June–30 June 1991 (Quantico, VA: MCHD), pt. 2, 1; and HMM-364 ComdC, 1 July–15 December 1991, pt. 4, item 1. Pinatubo’s eruption was the third natural disaster within a year that afflicted the Philippines; all drew Marine humanitarian assistance. The previous June, an earthquake shook the islands, and in September there were expansive mudslides. The 13th MEU(SOC) and MAGTF 4-90 provided assistance after the earthquake and MAGTF 4-90 assisted in the case of the mudslides.

- HMM-163 ComdC, 1 January–30 June 1991 (Quantico, VA: MCHD), pt. 2, 6; and 15th MEU(SOC) ComdC, 1 January–30 June 1991 (Quantico, VA: MCHD), pt. 2, 2–4.

- MAG-36 ComdC, 1 July–31 December 1991 (Quantico, VA: MCHD), pt. 4, item 4; and “Volcano,” Leatherneck 74, no. 9 (September 1991), 12.

- HMH-772 ComdC, 1 June–30 June 1991 (Quantico, VA: MCHD), pt. 2, 2–3, and pt. 4, item 4; MAG-36 ComdC, 1 July–31 December 1991 (Quantico, VA: MCHD), pt. 4, item, 5; and C. R. Anderegg, The Ash Warriors (Hickam Air Force Base, HI: Air Force History and Museums Program, 2000), 69–73.

- 11th MEU(SOC) ComdC, 1 January–30 June 1994 (Quantico, VA: MCHD), pt. 2, 1–3; “Two MEUs Off Somali Coast,” Marine Corps Gazette (April 1994): 4; “Marines Aid in Evacuations,” Marine Corps Gazette (May 1994): 7; and “Basic Terror,” in Donatella Lorch, “Strife in Rwanda: Evacuation,” New York Times, 11 April 1994.

- John H. Frese interview with Maj James G. Antal, 3 September 1996, transcript (Oral History Collection, MCHD, Quantico, VA), 6. Frese was the regional security officer at the American embassy in Monrovia, Liberia, in 1996.

- Antal and Berghe, On Mamba Station, 71–73.

- Antal and Berghe, On Mamba Station, 74; and VMGR-252 ComdC, 1 January–30 June 1996 (Quantico, VA: MCHD), pt. 2, 3–4.

- Antal and Berghe, On Mamba Station, 84. The 22d MEU(SOC) was relieved by a special mission MAGTF on 24 June 1996.

- LtCol Tony S. Barnes interview with Fred Allison, 16 October 2008, sound recording (Oral History Collection, MCHD, Quantico, VA), hereafter Barnes interview.

- VMGR-252 ComdC, 1 January 1996–30 June 1996 (Quantico, VA: MCHD), pt. 2, 3–4; Antal and Berghe, On Mamba Station, 89–91; 22d MEU(SOC) ComdC, 1–30 April 1996 (Quantico, VA: Gray Research Center), pt. 2, 4–5; and LtCol David A. Krebs, phone conversation with Fred Allison, 29 April 2010, notes in author’s files (Quantico, VA: MCHD).

- Antal and Berghe, On Mamba Station, 93–94.

- Antal and Berghe, On Mamba Station, 95–96.

- Antal and Berghe, On Mamba Station, 96–97.

- HMM-264 ComdC, 1 July–31 December 1996 (Quantico, VA: MCHD), pt. 2, 1–2, pt. 4, item 1; and 2d MAW ComdC 1 January–30 June 1994 (Quantico, VA: MCHD), pt. 2, 4.

- Antal and Berghe, On Mamba Station, 100–2; and HMM-264 ComdC, 1 July–31 December 1996 (Quantico, VA: MCHD), pt. 2, 1–2.

- Col Emerson N. Gardner Jr. interview with David Crist, 11 June 1997, transcript (Quantico, VA: MCHD), 6, hereafter Gardner interview with Crist.

- Antal and Berghe, On Mamba Station, 103.

- Gardner interview with Crist.

- LtCol Daniel E. Cushing interview with David B. Crist, 12 June 1997, transcript (Quantico, VA: MCHD), 14–16, hereafter Cushing interview; and HMM-365 ComdC, 1 January–30 June 1997 (Quantico, VA: MCHD), encl. 1, 8–9.

- HMM-365 ComdC, 1 January–30 June 1997, encl. 1, 8–9; Gardner interview with Crist, 11–12, 16–19; VMAQ-3 ComdC 1 January–30 June 1997 (Quantico, VA: MCHD), pt. 2, 7–8; and VMFA(AW)-224 ComdC 1 January–30 June 1997 (Quantico, VA: MCHD), pt. 2, 4–5.

- LtCol Jon T. Hardwick interview with David Crist, 12 June 1997, transcript (Oral History Collection, MCHD, Quantico, VA), 10–11.

- Cushing interview, 5–7, 14–16; Antal and Berghe, On Mamba Station, 103; HMM-365 ComdC, 1 January–30 June 1997 (Quantico, VA: MCHD), encl. 1, 8–9; and Gardner interview with Crist, 11–12, 16–19.

- LtCol Curtis E. Haberbosch, “Operation Guardian Retrieval: Operational Maneuver from the Sea and Ship-to-Objective Maneuver in 1997,” Marine Corps Gazette 83, no. 8 (August 1999): 32–33; and Gardner interview with Crist, 30–35. Eventually the 26th MEU evacuated about 800 people, more than 700 of these on the first three days before the ARG was split.

- Antal and Berghe, On Mamba Station, 103.

- LtCol Jon T. Hardwick, “Commentary on Operation Guardian Retrieval,” Marine Corps Gazette 83 no. 11 (November 1999): 90. Simba station was a point off the coast of west central Africa where the amphibious group posted.