International Perspectives on Military Education

volume 2 | 2025

Reason for Victory

The Theoretical Elements of National Security Policy

Andrew L. Stigler

https://doi.org/10.69977/IPME/2025.002

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: All policies, strategies, and operational plans are informed by a wide array of theories, whether in the form of sophisticated empirical investigations or assumptions based on limited evidence. Military officers who develop (or who advise those who develop) policies and strategies will constantly engage in theorization during the course of their duties. Despite this, they are not guaranteed to receive an educational grounding in theoretical assessment during their time in professional military education (PME). Being alert to the methodological issues that can arise during the course of military taskings can be a huge asset to an officer. This article offers guidance for military officers engaged in these tasks at an educational level that could be useful for both the intermediate and senior ranks of officers engaged in PME. The author explains why it is useful to employ a broad but accepted definition of the term theory to encompass concepts and assumptions based on limited evidence. This article explores the understated importance of theories, and it offers a framework for assessing the theoretical foundations of policy options. There are three primary opportunities to analyze theories and potentially detect errors in theoretical reasoning: by clearly stating each theory and its causal element, by exploring what evidence supports or disconfirms the theory, and by inquiring what competing theories could discredit the theoretical conclusions that support the policy option under consideration. While this article certainly does not present a perfect method for preventing errors, alertness to these three semisequential opportunities can prevent costly policy mistakes. All militaries would be well served if PME institutions offered students a more thorough grounding in these matters. This article offers guidance for officers engaged in these tasks and for PME faculty seeking to bring elements of theoretical analysis into their curricula.

Keywords: critical thinking, professional military education, PME, reasoning, theoretical assessment, causality

On 24 February 2022, Russian president Vladimir Putin decided to put his theory of military victory over Ukraine to the test. He believed that larger militaries will usually defeat smaller militaries, that a socially fractured Ukraine would not mount an effective resistance to a Russian invasion, that Russian-speaking Ukrainians would quickly align with Russia, and that Russia’s years of investment in its military had successfully increased its military capability.[1] These were among the many theories that underpinned Putin’s prediction that Russia would rapidly conquer Ukraine. As the world learned in the months and years that followed 24 February, the Russian leadership had done a poor job estimating the likely outcome of the invasion, a damning assessment that Putin shared.[2]

But Russia’s invasion also tested the theories of U.S. president Joseph R. Biden and his advisors, and some senior White House counselors were just as wrong as their Russian counterparts. Biden’s administration had predicted a Russian invasion of Ukraine eight months prior to the February 2022 attack, and communicated this prediction to the world. Some American officials, such as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff general Mark A. Milley, arrived at some of the same predictions that the Russians had relied on, particularly that the Ukrainian military would collapse in short order.[3] If instead those American officials had anticipated Ukraine’s successful resistance, they might have been incentivized to send more weapons to Ukraine as far in advance of the Russian attack as possible. Biden’s preinvasion policy might have been very different, possibly reducing Russian gains in early 2022. It should be noted that an undesired outcome does not necessarily indicate that a failed process of analysis was at work.[4] But for the West, as was the case with Russia, inaccurate theorizing of likely outcomes may have had serious consequences for a major European conflict.

These examples of American and Russian miscalculations surrounding the 2022 invasion of Ukraine illustrate the impact that theoretical reasoning can have on military assessments. To be sure, there are potential alternative explanations for these predictions other than theoretical miscalculation, such as motivated reasoning and groupthink.[5] But the theories that formed the foundation of American and Russian expectations, both stated and unstated, should be given a major share of the blame for the errors that followed.

For PME educators hoping to prepare officers to detect and prevent errors of reasoning that underpin military assessments, finding opportunities to improve students’ theoretical reasoning is a critical task.[6] At the start of new tours of duty, most military officers receive minimal formal education on recognizing and improving the theoretical foundations of their assessments, and they may advance in their careers with little guidance on how to detect and evaluate the theories they may be unwittingly applying to critical military and policy decisions.[7] PME may offer the only structured opportunity to address this educational gap.

This article proceeds as follows. The author illustrates the role of theoretical assessment in military officers’ careers with U.S. Army general Stanley A. McChrystal’s assessment of the reconstruction effort in Afghanistan in 2009. For continuity, McChrystal’s assessment will be used as an example throughout the article. The author then argues that officers should be alert to three primary opportunities to assess or reassess the theoretical foundations of national security policy. These three opportunities constitute a checklist of sorts, inspired in part by Atul Gawande’s The Checklist Manifesto.[8] Gawande’s work encourages the use of checklists in a very different but similarly consequential vocation: the operation of hospital intensive care units. Gawande found that simply reinforcing the steps necessary to minimize the likelihood of infections (i.e., having a checklist) led to a striking improvement in patient recovery rates.[9] If some of the errors in foreign policy could be prevented by PME institutions encouraging students to pay greater attention to the theoretical motivations for a policy, then such a checklist could focus efforts to improve any military assessment’s theoretical foundations.

There are three primary opportunities to assess the theoretical foundations of any prediction or assessment. First, by clearly stating the most important theoretical elements that form a foundation of an assessment, one can potentially detect gaps and oversights in the predicted causal chain of events and other potential weaknesses of the theory. Second, one should ask if the historical record offers supporting or disconfirming evidence that relates to those theoretical foundations. What do pertinent cases in the modern era say about the possible outcomes? Third, officers should look for competing and potentially disconfirming theories that could undercut the theoretical basis of a policy or assessment.

Most national security decisions are supported by a host of theoretical foundations, regardless of whether the decisionmaker is cognizant of that fact. Military officers often support senior leaders in the policymaking process, which is why PME institutions should seek to better prepare officers for what may be unfamiliar but mission-critical tasks. The theories (again, broadly defined) that motivate consequential decisions are often not grounded in deep research and robust empirical support. Sometimes leaders have too casually embraced the motivating theories that support a policy option for a major decision. Consider President George W. Bush’s dual theories that 1) Iraq could be successfully democratized following the 2003 invasion, and 2) that a democratic Iraq would inspire democratic transformation in the region.[10] These two images of benign policy outcomes, while potentially appealing to American audiences, could easily have invited profound skepticism if they had been subjected to closer examination. The United States’ colossal and multiyear investment in Iraq’s democratic reconstruction was partially propelled by these casually theorized aspirations.[11] The decision to invade is now viewed by many as a major policy blunder, and it serves as a potent indication that the topic of this article should be addressed by PME institutional curricula.[12]

This article embraces a broad definition of the word theory, one that is more aligned with common usage in foreign policy debates. Theory can refer to a conjecture that awaits proof or to a theoretical concept that one intends to apply to a concrete situation as a basis for action.[13] Methodologists Jason Seawright and David Collier embrace this usage when they define a theory as the “conceptual and explanatory understandings that are a point of departure in conducting research, and that in turn are revised in light of research.”[14] Theoretical understandings often also serve as a point of departure for developing foreign policy.

Theory, for this article, includes assumptions and concepts for which the individual holding the assumption has very little—and perhaps very bad—evidence in support of what might be considered an assumption based on limited evidence.[15] This broad definition of theory is employed for three reasons. First, Seawright and Collier’s definition emphasizes that theories can be “conceptual,” clearly implying theories can be theories even if they are undeveloped and inchoate. They state a theory can be a “point of departure,” suggesting theories exist at the beginning, and not only at the end, of a social science investigation. Rethinking Social Inquiry is a well-regarded text in the field for these reasons.[16]

Though the distinction between assumptions and theories is critical for theory development, assumptions and theories cannot be distinguished in and of themselves, and this article treats assumptions as theories in most respects. Any assumption can be described as a testable theory, and any theory could be converted to an assumption. Gary King, Robert O. Keohane, and Sidney Verba take this perspective in Designing Social Inquiry.

Simplifications are essential in formal modelling, as they are in all research, but we need to be cautious about the inferences we can draw about reality from the models. For example, assuming that all omitted variables have no effect on the results can be very useful in modelling. In many of the formal models of qualitative research that we present throughout this book, we do precisely this. Assumptions like this are not usually justified as a feature of the world; they are only offered as a convenient feature of our model of the world. The results, then, apply exactly to the situation in which omitted variables are irrelevant and may or may not be similar to results in the real world. We do not have to check the assumption to work out the model and its implications, but it is essential that we check the assumption during empirical evaluation. . . . [W]e cannot take untested or unjustified theoretical assumptions and use them in constructing empirical research designs.[17]

Second, the broad use of theory employed in this article is in accord with common usage in international relations research. “Theory of victory” is one example, where theory simply refers to a hypothetical chain of events during a conflict that could lead to military victory, potentially without any empirical reference at all. Rand’s 2024 monograph U.S. Military Theories of Victory for a War with the People’s Republic of China defines theory of victory on the opening page: “a theory of victory is a causal story about how to defeat an adversary.”[18] There is no mention of evidence, only that a theory of victory tells a plausible causal tale about how to reach a political objective using military force. The report offers other scholarly examples that make similar usage of the term theory.[19]

Colin S. Gray’s 1979 article “Nuclear Strategy: The Case for a Theory of Victory” also uses the term theory of victory, as the Rand report does, to refer to a causal tale. This same article also casually invents the term counter-recovery theory to refer to the belief held by some Soviet nuclear theorists that “recovery from [nuclear] war was an integral part of the Soviet concept of victory.”[20] The counterrecovery theory Gray referenced in the pages of International Security is certainly not as well-grounded in empirical research and the real-world testing of hypotheses as, for example, the theory of plate tectonics. This Soviet counter-recovery theory would have to be based on either pure speculation and estimation, or on the single and vastly different example of Japan’s recovery from two atomic attacks in World War II. Like Seawright and Collier, the authors of the Rand report and Gray use the word theory to refer to a causal concept without any empirical references. In short, the admittedly broad application of the term used here is commonly accepted in the field.

The third and final reason is strategic. By using the word theory to refer to even casual assumptions based on little evidence, the author intends to draw attention to the fact that military and foreign policies could be greatly improved if all limited-evidence assumptions, expectations, and predictions were treated as theories to be questioned and critiqued with as much rigor as time and resources allow. For many people, the term theory calls forth the methodological obligations of scientific investigation, the need to search for evidence, and the intent to apply one’s capacities for critical assessment. Employing this word in its broader but accepted usage in political science may inspire readers to question their assumptions and expectations more rigorously.

This article also takes a somewhat simplified approach to explaining theorization, one that might be called naively positivist. Many or most policymakers are arguably motivated by multivariate theories, and this article simplifies the theorization process considerably. This simplification hopefully offers useful guidance to improve the assessment of military strategies and national security policies. A PME faculty developing curricula to address the topic of theorization would need to embrace a host of similar simplifications.

One of the most significant examples of the broad and colloquial use of the term theory in policymaking—and certainly at the presidential level—was President Richard M. Nixon’s “Madman Theory,” as Nixon dubbed his concept. In Richard Reeves’s description, this theory consisted of Nixon’s belief that “there was advantage in persuading adversaries, foreign and domestic, that there was something irrational about [Nixon], that he was a dangerous man capable of any retaliation.”[21] Nixon’s Madman Theory was based on a belief that an American president who cloaked himself in an image of unpredictability would enhance the United States’ ability to deter the Soviets from acting aggressively, while also potentially generating diplomatic leverage. This theory was not expressly based on facts or history, but it was rather a product of Nixon’s personal beliefs about ways to gain bargaining advantage, and these conjectures motivated an important part of his administration’s foreign policy for a time.[22]

For some significant decisions, even if a leader were keen to learn from history, there may be a limited or nonexistent historical record of comparable events. In such a case, the theories that motivate policy may lack any historical grounding. For example, when President John F. Kennedy led the United States into uncharted policy territory during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, he had recently read and “been impressed” by a memorandum written by Thomas Schelling.[23] Schelling’s memorandum dealt with the manipulation of risk in international affairs to increase bargaining advantage, a concept he was developing at the time and that he fleshed out in his influential book Arms and Influence.[24] That book, which is now seen as Schelling’s defining work on the topic, is based on speculative reasoning about what leaders might do in hypothetical situations. In October 1962, the fate of the world may have hung on Schelling’s hypotheticals.

Mobilizing Theories: General McChrystal’s 2009 Assessment of Afghanistan

On 30 August 2009, General Stanley McChrystal was preparing to take command of North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO) International Security Assistance Force (ISAF). To clearly communicate his understanding of the situation and his intentions to ISAF and the rest of the U.S. government, he offered an assessment of the current state of U.S. and Coalition strategy in Afghanistan. McChrystal’s “Commander’s Initial Assessment” quickly became a much-discussed document.[25] What makes the statement useful for PME faculty teaching theorization (and as a PME teaching example) is that the assessment was written by military officers, and it is a document full of brisk, arguably off-the-cuff theorization. Consider an early section that discussed some of McChrystal’s planned goals. He argued that:

We must grow and improve the effectiveness of the Afghan National Security Forces and elevate the importance of governance. We must also prioritize resources to those areas where the population is threatened, gain the initiative from the insurgency, and signal unwavering commitment to see it through to success. Finally, we must redefine the nature of the fight, clearly understand the impacts and importance of time, and change our operational culture.[26]

McChrystal’s 2009 statement is partly inspiration for the troops and partly a senior officer’s self-marketing, of course. Regardless, it states some of what McChrystal aspired to undertake as commander, and so offers a window into the pervasive role that theoretical reasoning plays in military policy.

Take the goal to “elevate the importance of governance,” which probably refers (at least in part) to how Afghan political leaders approached their roles as stewards of the Afghan nation and their responsibilities as national leaders.[27] The goals and actions implied by this phrase embrace a host of complicated theoretical assumptions and concepts. This proposal would be nothing less than an effort to alter the mindsets of many or all Afghans in government, to make that new mindset enduring, and to prevent other forces and elements within and without Afghan society from undermining those changes. That is an incredibly complex task.

By what means might McChrystal assess progress toward the goals he has identified? A battalion of well-resourced cultural anthropologists would find predicting the likely outcome of such an initiative a daunting endeavor. Few members of the military are intellectually prepared to address these questions, and understandably so, since these questions are not the normal foci of a military organization. PME institutions, of course, have the opportunity to address this area, and are unique in this regard.

Other paragraphs of the commander’s assessment offer equally complicated initiatives. Consider, in isolation, the paragraph’s concluding reference to a need to “change our operational culture.” Later in the assessment, McChrystal added that he hoped to change ISAF’s operational culture with the goal of reducing the U.S. military’s “pre-occup[ation] with protection of our own forces.”[28] This goal embraces the complex task of convincing members of the U.S. military to reduce their deeply embedded culture of force protection—a task that is easily stated, but that would face a daunting array of obstacles.

Negative consequences could follow even an attempt to change the force protection culture of an organization. ISAF casualties could rise to an unacceptable level as a consequence. One could also ask if it is within the power of a theater commander such as General McChrystal—who, after all, is only the commander of forces that have been trained and sent to him by the military Services—to change his force’s operational culture. It seems clear that McChrystal proposed this organizational recalibration to make ISAF’s interactions with Afghans less confrontational. But even if this initiative was perceived by Afghans in the way that McChrystal intended, it does not necessarily follow that the Afghans’ new perception of ISAF would improve local or regional stability.[29]

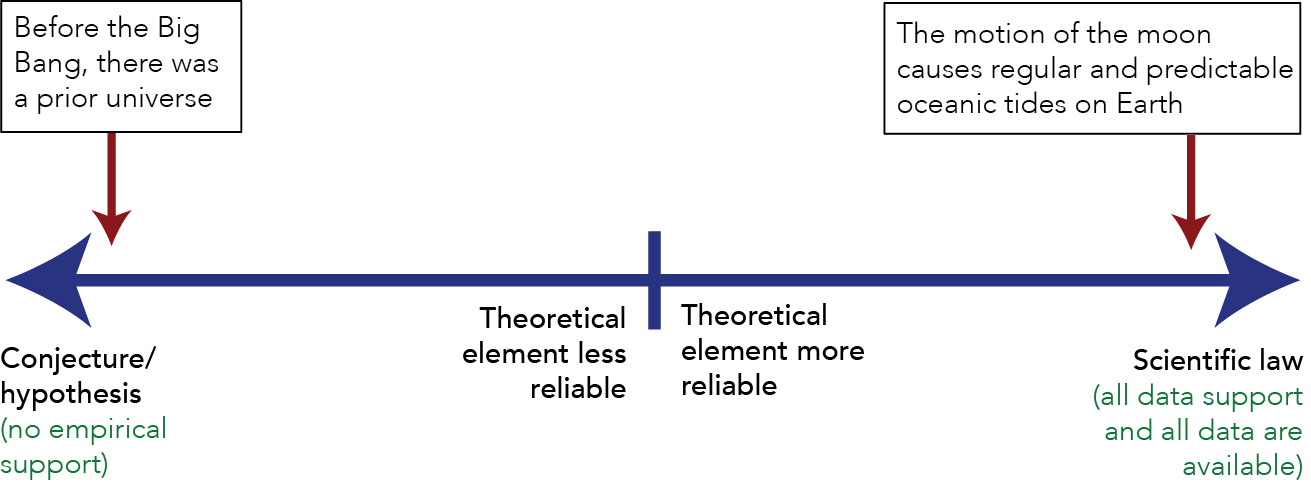

Figure 1. Spectrum of theoretical reliability

Source: courtesy of the author, adapted by MCUP.

Theoretical Reasoning and National Security

A theory refers to “a general statement that describes or explains the causes and effects of classes of phenomena.”[30] In many respects, theories are not new to military officers or to PME institutions. Nuclear propulsion engineers learn to manage nuclear reactors by executing a course of instruction on nuclear power plant dynamics and the theories underpinning nuclear fission. Similarly, PME institutions may address many social science theories, such as international relations theory.[31]

Theories can have different levels of empirical support in the real world, as bluntly expressed in figure 1. On the left end of the spectrum of empirical support is pure hypothesis.[32] While we have limited empirical traction on the early universe—the 3K cosmic background radiation that was accidentally discovered in 1965 is a rare counterexample—we have no data on whatever did or did not exist prior to the Big Bang. In contrast, consider the right side of the spectrum. We know the timing of the Earth’s oceanic tides are a consequence of synthesizing multiple theories (e.g., the law of gravity, the law of momentum as applied to orbits, and other theories).

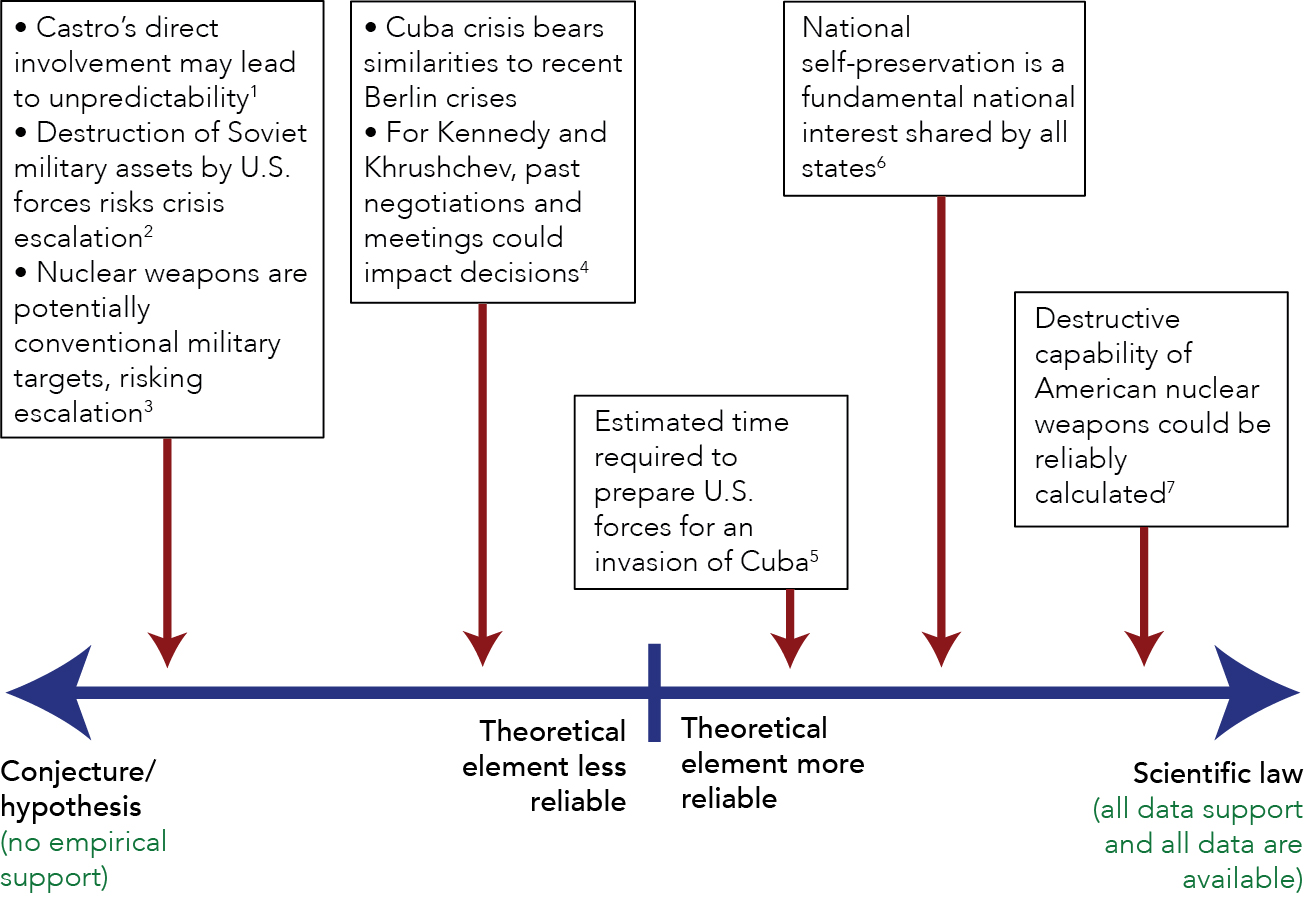

One can—as presidents and military officers often do—take actions in the national security realm based on an unsupported conjecture, as discussed earlier. Some realms of national security policymaking, such as nuclear deterrence in the early stages of the Cold War, involved taking significant actions that were not based on comparable historical examples. To illustrate, figure 2 attempts to represent just a few of the many theoretical conjectures that could have informed President Kennedy’s decision-making during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Figure 2. Spectrum of theoretical relability, with select Cuban Missile Crisis theoretical conjectures

1 Cuban president Fidel Castro’s involvement added an element of unpredictability. To offer evidence of this from the aftermath of the crisis, Castro resisted the removal of Soviet missiles following the missile-swap agreement between the United States and the USSR that ended the crisis. See Laurence Chang and Peter Kornbluh, eds., The Cuban Missiles Crisis, 1962: A National Security Archive Documents Reader (New York: New Press, 1992), 239–44.

2 American forces had not engaged in direct combat with Soviet forces since the Russian Revolution of 1917. The escalatory danger that could result from large-scale conventional combat between two superpowers, in particular the risk of nuclear escalation, had no historical comparison.

3 The destruction of a country’s nuclear assets was believed to have particular escalatory potential, as discussed below. There were no prior examples of nuclear weapons being destroyed during conventional combat in the historical record.

4 Kennedy and Soviet General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev had met before the crisis. They had also engaged in mutual strategic confrontations in prior cases, such as the Berlin crisis of 1961. As a consequence, there were past interactions from which they could attempt to extrapolate the other’s likely behavior and motivations.

5 American military officials could only estimate the time it would take to mobilize and position American forces for an invasion of Cuba. Mobilizations are chiefly physical processes, and mobilizations in general are often rehearsed. But maneuvering and readying the range of assets necessary to attack Cuba was a complex organizational feat, one that was vulnerable to delays. Some Executive Committee advisors from the National Security Council recognized this.

6 Nations seek to survive, and that fact deeply influences the actions of states in international crises. That theoretical statement is based on a considerable record of international interactions, and is a more reliable theory than others to the left on the spectrum.

7 A nuclear detonation and the resultant damage involve highly regular physical processes. Nuclear weapons are tested in monitored environments, and their behavior in combat is exactly the same as in a matching testing environment. This is the only theoretical element in this crisis that is nearly devoid of all human-centered uncertainty.

Source: compiled by the author, adapted by MCUP.

The military option of an air campaign to eliminate the Soviet missiles in Cuba would put Kennedy’s advisors in new theoretical territory. Neither superpower had conventionally attacked the nuclear forces of the other prior to 1962. Some deterrence theorists speculated that attacks on nuclear forces could be particularly destabilizing, since a nuclear nation could reasonably conclude that such attacks threatened that state’s nuclear deterrent.[33]

Returning to figure 2, on the right side of the empirical spectrum is the destructive capability of nuclear weapons. These weapons are the products of scientific development and testing, based on reliable understandings of how the physical components of the weapons interact. The weapons had been tested in monitored environments. Note the limited goal of the chart. Figure 2 is only intended to offer a notional illustration of how one might rank order the empirical foundations of the component theories involved in arriving at a policy decision.[34]

Near the middle of the spectrum on figure 2 is the mobilization time that would be required before American military forces could be ready to launch an invasion of Cuba. For example, at a meeting on 22 October 1962, Robert S. McNamara mentioned “several days” had been required to send additional U.S. Marines, and spoke of additional planned troop movements.[35] It is largely a physical process to engage in a mobilization of this sort, and as such might be expected to be highly predictable. But the organizational actions and routines for this specific mobilization had not been worked out, let alone rehearsed. Military officials had some basis from past experience on which to arrive at an estimate, but the outcome that would follow a mobilization order from the president was not as predictable as the physical outcome of the detonation of a nuclear weapon.

This discussion of figure 2 is intended to highlight the empirical foundation behind each theoretical element, as empirical support can be a vague proxy for the reliability of a theory. Even when scientifically minded individuals undertake to develop reliable theoretical guides for their recommendations, miscalculations can occur. Consider this example from Rand’s Project Air Force, in which two analysts attempted to generate an aerial combat model for U.S. Air Force tactical training shortly after World War II.

In 1949, Ed Paxson and another early systems analyst at RAND, Edward S. Quade, worked for many months on mathematical models of hypothetical air duels fought between fighter planes and bombers. After trudging through a tremendously large series of complicated equations, Paxson and Quade concluded that, with the right kind of fire-control systems, a fighter pilot could close in on a bomber at a certain optimal point, fire his weapon, and shoot the bomber out of the sky in six out of ten confrontations. After doing these calculations, Paxson and Quade compared their findings with real combat data from World War II. They found that in those cases where the fighter and bomber were in roughly the same geometric position that Paxson and Quade figured would give the fighter a 60 percent probability of a kill, the fighter pilot actually downed the bomber only 2 percent of the time. Why the huge difference between theoretical calculation and reality? They puzzled over this disparity for a few disturbing days, and finally conceded that a real pilot in a real airplane shooting real bullets does not so eagerly or easily close in on a big bomber. He takes a couple of shots perhaps, and then veers off. Doing anything more would be too dangerous.[36]

Three Opportunities to Critically Assess Theories

The following section, expanding on points made above, offers an approach to understanding the process of applying theories to national security situations. As discussed earlier, there are three primary opportunities to assess and potentially reconsider the theoretical foundations of a proposed policy:

• Clearly state the theory or theories,

• Assess the evidence in support of a theory or theories, and

• Identify and evaluate competing or contradicting theories.

This guide does not purport to be a reliable method for purging foreign policy proposals of theoretical error. It can only reduce the risk of overconfidence in one’s preferred proposals, and increase the likelihood of recognizing theoretical shortcomings and critical countervailing factors. For each of these three reassessment opportunities, the author returns to McChrystal’s assessment as an illustrative example.

State the Theory

By concretely and explicitly stating the theory (even a casually derived assumption based on limited evidence) that one intends to apply to a situation, one clarifies the causal factors and expectations involved, potentially illuminating unnoted weaknesses or gaps in reasoning. When PME institutions teach a methodological approach to planning Joint military operations, some programs highlight the criticality of scrutinizing the “commander’s intent” that lies at the foundation of the operation.[37] In a similar fashion, having a detailed grasp of the theories involved in a policy proposal helps isolate the “theoretical intent.”

In the aforementioned example of the 2003 invasion of Iraq, consider if George W. Bush or his key advisors had stated in more concrete terms the processes by which a democratic Iraq would inspire democratic transitions in other countries in the region. A skeptic might ask why, precisely, Iraq’s neighbors would be keen to change their political systems to mimic a Western political model, particularly one that was imposed on Iraq following an invasion. After a forced regime change that the international community had mostly condemned, Iraq’s neighbors would be unlikely to evenhandedly ask themselves if Iraq’s new democratic model was appealing. And those nations would be far less likely to undertake a most profound transition of governance, which would involve autocratic leaders giving up power or populations suddenly inspired to launch a dangerous revolution where there had been no such impulse before, because America had militarily imposed such a transition on Iraq. These and other flaws in the theoretical reasoning behind the invasion were there to be found, as some academics discussed prior to the invasion.[38]

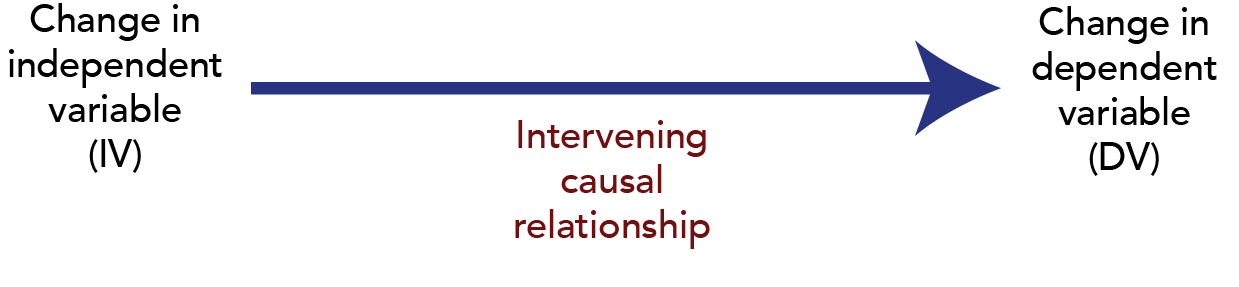

Any recommendation on national security policy involves a host of theories. To specify a theory, one identifies a specific phenomenon one wishes to explain or predict. This is the dependent variable (DV) because it is the outcome that is caused by, or depends on, another factor. After one is clear on the phenomena one wishes to explain or predict, one must then identify the factor or factors that are responsible for the potential changes observed in the DV. This is the independent variable (IV), the variable that is manipulated to impact the DV. One wishes to know the impact of the IV on the DV, independent of all other factors.

Figure 3. Independent and dependent variables

Source: courtesy of the author, adapted by MCUP.

The IV is not likely to be truly independent, of course, in the stricter sense of the word. Independent variables are caused by and dependent on other factors as well. For the purposes of isolating causal factors to develop at least a notional theory, one must isolate—perhaps arbitrarily—a causal factor or independent variable.

After the analyst has established an independent and policy-relevant relationship between the two variables, one must consider the role of causality. How, specifically, does a change in the independent variable determine whether there is a change in the dependent variable? Can we observe any factors that suggest a causal process? Elaborating on these causal linkages can help identify any dubious links in the hypothesized causal process. Causality in international politics is certainly more complicated and dynamic than causality in chemistry, for example. But developing a military or foreign policy is impossible without thinking about the causal environment.

McChrystal’s Assessment

Consider the excerpt from McChrystal’s assessment regarding the reworking of ISAF’s operational culture to reduce his force’s preoccupation with force protection. This initiative involves a number of theoretical elements. For example, McChrystal would be ordering his force to shed some of the force protection training that they had received to date, including force protection techniques that individual service personnel or entire units had adopted as essential routine during previous deployments. Such a reworking of operational culture might not be unprecedented. It is not uncommon for units to find they need to learn new procedures or adapt to new weapons systems while on deployment.

But how feasible is it to reduce a force’s ingrained procedures for something as fundamental as force protection? To gauge the likelihood of success, one would ask what parts of the military’s organizational culture might resist or obstruct an effort to make the unit become “consciously risky” with the lives of personnel. There is certainly no reason to believe McChrystal intended to be cavalier with the lives of those under his command. But McChrystal’s recommendation would increase the risk to soldiers’ lives, and reengineer elements of his units’ organizational culture to do so. Executing such a change responsibly and without unnecessary risk would be a tall order.

And to engage in conjecture, what would be the ultimate benefit of this approach? McChrystal does not explain why his recommendation would have a positive impact on the reconstruction effort. But his underlying assumptions very likely include: 1) the Afghan population resented at least some of ISAF’s force protection measures, 2) a lessening of these force protection measures would be understood by Afghans to be an ISAF adjustment intended to placate the Afghan population, and 3) this perception by the Afghans would lead to a decrease in friction between ISAF and the Afghans, and, consequently, improve Afghanistan’s stability. Here is a concrete example of how plainly stating the theory can, in and of itself, highlight unstated causal expectations and indicate links in the causal chain that may merit additional scrutiny.

To speculate further, would the Afghans perceive ISAF’s changed approach to force protection? McChrystal is hoping that Afghans would take note of a series of nonevents, such as occasions when ISAF soldiers do not inhibit commerce or travel (when they would have inhibited travel prior to the policy change), as well as occasions when ISAF did not intercept and search vehicles and persons as often or as thoroughly as they had previously, and the like.

But there are other possible rationales that Afghans might seize on to explain ISAF’s reduced force protection efforts. The Americans could be reducing their activity in the area to avoid exposure to Taliban attacks or some other threat. Or, alternately, Afghans might conclude that ISAF no longer had the means to support the previous approach to force protection. In other words, instead of seeing force protection changes as a reason to positively reappraise ISAF, successful force protection changes could be seen by Afghans (correctly or incorrectly) as instead an indication of a weakening of ISAF, and not as a friendlier new policy.

This discussion of McChrystal’s proposal has arguably been biased toward pessimistic conclusions. While that may be true, if there is a foreign policy endeavor for which one might prudently err in the direction of expecting poor outcomes, it is the forceful occupation and social reconstruction of a society by an outside power. Clearly stating the theoretical foundations of a policy opens the door to such potentially life-saving skepticism, and improved PME education in this critical area could be invaluable to officers in the field.

Assessing the Evidence in Support of a Theory

All human beings have cognitive biases, and it is important to do the best one can to avoid steering analyses toward preferred conclusions.[39] That is far more easily said than done, and national security policy may be an area that is particularly susceptible to biases. Fear of aggression and suspicion of adversaries are sentiments that are common in international relations, and those factors can profoundly influence one’s assessment. And sometimes bias can seem like prudence in retrospect. Winston Churchill is often celebrated for his intuition regarding Adolf Hitler’s motives before World War II broke out, but it may have been his lifelong suspicion of Germans—and not his sagacity—that inspired his eagerness to steer Britain toward opposing Germany in the late 1930s.[40]

Addressing the following questions could improve an assessment of applicable evidence:

• How strong is the evidence in support of the theory? How clear are the narratives in relevant historical examples? During the war over Kosovo in 1999, one of the unstated assumptions that led Western policymakers to believe that Slobodan Milošević would back down if NATO attacked was the belief that Milošević did not highly value Kosovo. Some Western officials believed that Milošević’s concessions in Bosnia in 1995 were the consequence of NATO military action and not the consequence of ground advances by Bosnian and Croat forces. That conclusion overlooked important differences between the 1995 and 1999 conflicts, however. Kosovo was home to the Field of the Blackbirds, part of the site of the Battle of Kosovo in 1389, and so a place a tremendous historical significance for the Serbs.[41] That and other historical considerations, had they been taken into account by policymakers, could have spurred a broader reassessment of whether the 1995 example truly suggested that Milošević would relent in the face of NATO airstrikes in 1999.

• Is the evidence supporting the theory, or the reason that one believes the theory is correct, based on a single example or multiple cases?[42] Are there other relevant cases that have been overlooked, even if they undermine the preferred policy? In other words, self-evaluation in this area demands that one ask if selection bias played a role in the review of comparable historical cases.[43] If there are one or more cases that contradict the theory, one should ask if those cases can be safely ignored. A theory can be simultaneously well-supported during decades of history and irrelevant for the specific policy decision at hand.

• What role does counterfactual reasoning play in an assessment, and how reliable is that reasoning? Counterfactuals are estimations of what would have happened if the historical chain of events had been altered in one or more respects. Historians have asked if President John Kennedy would have avoided escalating American involvement in Vietnam had he not been assassinated. Addressing this counterfactual, Stephen Knott argues Kennedy might have declined to increase America’s military commitment to South Vietnam. Knott observes “Maxwell Taylor [then Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff] . . . could not recall anyone who was strongly against deploying combat troops [to Vietnam] ‘except one man and that was the President. The President just didn’t want to be convinced that this was the thing to do’.” If Taylor was correct, American military escalation in Vietnam might have been avoided, had the assassination attempt failed.

- Counterfactuals are more reliable when they more closely align with the historical record. Philip E. Tetlock and Aaron Belkin, among others, promote the “minimal rewrite of history” rule: the smaller and more easily imagined the proposed change to the historical record, the more realistic the counterfactual argument.[44] In the above example with Kennedy, the alternate reality in which Kennedy lived through his first term is a highly plausible alternative, since it only requires a few missed shots from Lee Harvey Oswald to bring about the counterfactual scenario. In contrast, the counterfactual “What if Richard Nixon had won the 1960 presidential election?” requires a more significant alteration of the historical record, in this case a different electoral outcome in 1960.

• Is there evidence that organizations or individuals that support the proposed policy have a desire or interest in reaching a specific conclusion? Leaders and their advisors may unwittingly bring organizational biases into their assessments of evidence. General William C. Westmoreland believed enemy body counts were a reliable gauge of progress in the effort to stabilize South Vietnam, and he was only interested in theoretical assessments of progress that relied on this metric. Westmoreland never fully grasped the importance of North Vietnamese motivation on the conflict, and he did not understand how this resolve insulated the North’s decisionmakers from the potential coercive impact of North Vietnamese casualty figures.[45] Organizational biases for particular metrics or preferred approaches can have a highly detrimental impact on decision-making processes, a conclusion already found in at least one PME curriculum.[46]

McChrystal’s Assessment

Turning again to McChrystal’s intent to improve Afghanistan’s stability, what evidence might be used to evaluate the probability that events would play out as McChrystal hoped they would? There are past examples of smooth reconstruction processes that supporters of McChrystal’s approach might point to. John W. Dower’s study of the post-World War II American occupation and political reorientation of Japan, Embracing Defeat, explains how Japanese resistance to American occupation was almost nonexistent.[47] Once Emperor Hirohito announced his government’s surrender, the Japanese accepted that the war was over almost overnight. One could offer this as evidence in support of McChrystal’s theory, as an example of a violent conflict that transitioned into a peaceful and successful reconstruction. But this comparison masks critical differences between postwar Japan and post-invasion Afghanistan. After World War II, the Japanese sought to resurrect what had been a homogeneous and cohesive industrial society, not to create a national society where none had previously existed—a profound contrast to the United States’ chosen task in Afghanistan.

After the defeat of al-Qaeda and the Taliban in Afghanistan in 2002, American civilian and military leaders briskly decided that it was possible to create a border-to-border federal government in Afghanistan. George W. Bush, in his memoir, declared that “we had a moral obligation to leave behind something better” by installing a national and democratic government.[48] There is room to conclude that American leaders arrived too casually at the conclusion that a postwar creation of an Afghan sense of nationhood was achievable, without asking what evidence they had to support this conclusion. The Soviet failure to pacify and stabilize Afghanistan during their invasion from 1979 to 1989 is a potent example of Afghans’ ability and willingness to resist outside powers.

A post-withdrawal summary report of the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) avoids assessing whether a stable Afghanistan was ever within the realm of the possible, stating “[w]hether a different outcome could have been achieved is a question for history.”[49] However, that report concludes with a note of pessimism regarding American capability in future reconstruction efforts, even after 20 years of reconstruction-focused organizational learning: “Any future U.S. reconstruction mission similar in scale and ambition to that in Afghanistan is likely to be difficult, costly, and defined by a real possibility of an unfavorable governance outcome.”[50]

Identify and Evaluate Contrasting or Contradicting Theories

The third opportunity to reassess the theoretical basis of a policy decision is to explore the possible impact of alternative theories, with a focus on identifying causal factors that might prevent a preferred outcome. For example, one could ask if political or organizational priorities within a government or agency led to an inadequate consideration of alternative theories. Cabinet members may fail to fully assess alternative theories if they become aware that a prime minister or president prefers a particular policy option. This is one of the reasons John Kennedy absented himself from early deliberations of the Executive Committee during the Cuban Missile Crisis, to avoid having his presence inadvertently prejudice discussions.

• What are the obvious alternative theories, and how might those alternatives also find support in the historical record? During the reconstruction of Afghanistan, there were scholars offering alternative theories regarding the serious limitations on American capability to impose or inspire lasting change in Afghan society. In Preponderance in U.S. Foreign Policy, Graham Slater argues that the United States has, since 1945, shown a tendency to overestimate the extent to which American power can be used to alter the political and social environments of other nations.[51] Rory Stewart and Gerald Knaus, in Can Intervention Work?, argue that the Coalition that sought to remake Afghanistan could not make progress because “the international community lacked the knowledge, the power and the legitimacy to engage in politics at the local provincial level.”[52] Stewart and Knaus observe that the U.S.-led Coalition also had no reliable metrics of progress, and so it was impossible to know when efforts were succeeding or failing.[53]

• The 1999 air war over Kosovo offers another example. During Operation Allied Force, President William J. Clinton and his advisors believed that NATO air attacks on the Serbian military and other targets would convince President Slobodan Milošević to stop the Serbs’ oppression of Kosovar Albanians. According to Richard Holbrooke, the foundation for this prediction was a single case: Milošević’s decision to relent when faced with Western airpower in 1995, when NATO bombing led to the Dayton Accords.[54]

• But Milošević did not follow NATO’s expectations in 1999. When the bombing began, the Serbs did the opposite of what the Clinton administration expected, and instead escalated their deprivations on the Kosovar Albanians. Rather than pressure Belgrade to stop their attacks on non-Serbs in Kosovo, NATO had instead inadvertently created what the Serbs saw as an opportunity to eliminate the Kosovo Liberation Army and gain leverage over NATO in any final settlement.[55] Because the alliance failed to consider alternative theories of how Milošević would respond to a coercive effort, NATO found itself engaged in a coercive air campaign with no guarantee that Milošević could be successfully coerced.[56]

McChrystal’s Assessment

It is not hard to identify countertheories to McChrystal’s proposed theory of how a recalibration of force protection procedures could reduce the friction generated by the American-led reconstruction effort. Afghans might fail to perceive the change in ISAF procedures, as discussed earlier. While not speaking directly to the issue of how Afghans perceived their occupiers after 2001, Barnett R. Rubin notes in his history of Afghanistan that Afghan resistance to outside governance in the past had always “frustrated the various foreign plans” for a unified country.[57] In April 2002, as the Taliban’s resistance crumbled, Pashtun mujahideen leader Gulbuddin Hekmatyar told a reporter from the New York Times that “we prefer involvement in internal war rather than occupation by foreigners.”[58]

Conclusion

It is impossible to eliminate the use of theoretical guesswork in military affairs and national security policy. The theories that inform even well-considered decisions are often inchoate, and the time-constrained and politically influenced processes by which governments arrive at decisions require them to quickly assess a wide array of unmeasurable factors. Even when time for careful assessment is available, abstract theorization is usually unavoidable. Professional military education is the vital—and probably the only—opportunity to offer instruction to military officers on this critical element of the profession.

The importance of policy-relevant theorization may be best illustrated by the dramatic shift in Dwight D. Eisenhower’s thinking on the subject of nuclear deterrence. As a five-star general during World War II, Eisenhower believed that nuclear weapons had no military utility, should never to be used, and that the bomb was an “awful thing.” By October 1953, when Eisenhower was in the White House, his New Look strategy argued that nuclear weapons were eminently usable, and even embraced them as the first line of defense.[59] President Eisenhower had reconsidered and rejected General Eisenhower’s theories, and the president had arrived at a very different strategic perspective. His new perspective must have been largely the result of a shift in his theoretical reasoning about the potential military and strategic role of atomic weapons. There had been no uses of atomic weapons since 1945, so there was no new data from the employment of nuclear armaments that could have led to the change in the president’s thinking. Eisenhower had given more thought to the role of nuclear weapons, and changed his mind. Even if he adopted the new posture on nuclear weapons partly or largely as a bluff, as some have suggested, it still marked a significant shift in perspective.[60]

Theories are no less important today. Consider how the United States may have inadvertently embraced the risk of future terrorist attacks when American naval forces retaliated against Houthi groups interfering with international shipping in January 2024.[61] One of the many lessons from the 9/11 attacks is that violent military measures used to confront immediate threats can generate long-term resentments, which subsequently foster terrorism years or decades later. In a 2001 manifesto justifying terrorism against Western nations, Osama bin Laden cited perceived American offenses against the Muslim ummah dating from the 1980s and earlier.[62] The fact that it is hard to confront threats in the international arena without generating resentments does not mean that it is wise to always ignore the potential future strategic impact of those resentments. How seriously did Biden’s aides assess the alternative theory that, in the 2024 example of Yemen, the long-term risks of generating terrorism actually outweighed the immediate regional deterrence benefits? One might speculate that Biden and his

advisors did not engage in any such assessment, making this another example of the casual acceptance of conventional theoretical wisdom.

National security professionals often have little time in which to do their best to assess the theoretical aspects of the situations they encounter, and to estimate, in as structured a way as possible under the circumstances, the quality of their underlying theorization. Decisions must often be arrived at rapidly—a caveat that is particularly true for military officers—and often decisions must be taken on the basis of incomplete information. The resulting decision must then be confidently communicated to the government or military unit. But if the need for speed and decisiveness overwhelms the need to think as deliberately as possible about the theories that form the foundation of a decision, the policy in question may suffer. Professional military education offers one of the scarce opportunities to prepare officers to engage in deliberate theoretical assessment, assessment that is critical to their success in both strategic and operational duties.

Endnotes

[1] This list is adapted from Natalia Bugoyova, Kateryna Stepanenko, and Frederick W. Kagan, “Weakness Is Lethal: Why Putin Invaded Ukraine and How the War Must End,” Institute for the Study of War, 1 October 2023.

[2] Approximately two weeks after invading Ukraine, Putin had two of his top intelligence officials interrogated for providing poor intelligence and then placed under house arrest, a strong indication Putin was unhappy with his government’s preinvasion analysis. Helene Cooper, Julian E. Barnes, and Eric Schmitt, “As Russian Troop Deaths Climb, Morale Becomes an Issue, Officials Say,” New York Times, 16 March 2022.

[3] Yuliya Talmazan, Tatyana Chistikova, and Teaganne Finn, “Biden Predicts Russia Will Invade Ukraine,” NBC News, 20 January 2022; and Jacqui Heinrich and Adam Sabes, “Gen. Milley Says Kyiv Could Fall within 72 Hours if Russia Decides to Invade Ukraine,” Fox News, 5 February 2022.

[4] The author thanks the anonymous reviewer for this observation.

[5] For an overview of these and other applicable cognitive concepts, see Ulrike Hahn and Adam J. L. Harris, “Chapter Two—What Does It Mean to Be Biased: Motivated Reasoning and Rationality,” Psychology of Learning and Motivation 61 (2014): 41–102, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-800283-4.00002-2.

[6] At the Naval War College, instructors have at times included material on critical thinking and reasoning. They also offer a seminar session dealing with cognitive heuristics and their impact on decisions and assessments.

[7] While the author has not performed a scientific survey on this topic, the speculation here is based on many conversations with students and military colleagues.

[8] Atul Gawande, The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2011).

[9] For a shorter review of Gawande’s arguments regarding the advantages of checklists, see Atul Gawande, “The Checklist,” New Yorker, 2 December 2007.

[10] “Iraqi democracy will succeed . . . that success will send forth the news, from Damascus to Tehran—that freedom can be the future of every nation. The establishment of a free Iraq at the heart of the Middle East will be a watershed event in the global democratic revolution.” George W. Bush, “President Bush Discusses Freedom in Iraq and the Middle East,” press release, White House, 6 November 2003.

[11] For the costs involved, see Jason W. Davidson, “The Costs of War to United States Allies since 9/11,” Watson Institute Working Paper, Brown University, 12 May 2021.

[12] Joseph Stieb, The Regime Change Consensus: Iraq in American Politics, 1990–2003 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 1–2, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108974219.

[13] For a brief discussion of the colloquial usage, see “ ‘I Have a Theory . . .’. What Do I Really Have?” StackExchange: English Language & Usage, accessed 3 February 2024.

[14] Seawright and Collier use this definition in Henry E. Brady and David Collier, eds., Rethinking Social Inquiry: Diverse Tools, Shared Standards, 2d ed. (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2010), 354. The author uses the term explanatory to describe what might come to pass in the future, which is a plausible and applicable perspective on this element of their definition.

[15] There is probably no assumption in international security that is completely unmotivated by evidence, albeit potentially grossly misapplied and magnificently limited evidence. A leader who believes “I just know they’ll give in,” is motivated by some memory of a past example or some concept of how international bargaining works. Nuclear deterrence theory, at its earliest stages, was not based on past evidence, as discussed below. Early deterrence theorists (e.g., Thomas C. Schelling) used their knowledge of history and conventional crisis bargaining to speculate on what might happen in diplomatic exchanges between nuclear powers. They were still using history and evidence from conventional military conflicts to try to arrive at policy recommendations for nuclear confrontations. See, for example, Thomas C. Schelling, The Strategy of Conflict (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University 1980); and Thomas C. Schelling, Arms and Influence (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008).

[16] Rethinking Social Inquiry is sometimes assigned in graduate methods classes, such as Brown University PhD program’s introduction to methods, for example. The author thanks Brian Hasse for this insight.

[17] Gary King, Robert O. Keohane and Sidney Verba, Designing Social Inquiry: Scientific Inference in Qualitative Research (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994), 106. Emphasis added. The author reads “omitted variables” as similar to “assumptions” in theory lexicon.

[18] Jacob L. Heim, Zachary Burdette, and Nathan Beauchamp-Mustafaga, U.S. Military Theories of Victory for a War with the People’s Republic of China (Santa Monica, CA: Rand, 2024), 1, https://doi.org/10.7249/PEA1743-1.

[19] Heim, Burdette, and Beauchamp-Mustafaga, U.S. Military Theories of Victory for a War with the People’s Republic of China, 1–2.

[20] Colin S. Gray, “Nuclear Strategy: The Case for a Theory of Victory,” International Security 4, no. 1 (Summer 1979): 65–66, https://doi.org/10.2307/2626784. Emphasis omitted.

[21] Richard Reeves, President Nixon: Alone in the White House (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001), 57, 136. By one account, according to Nixon aide H. R. Haldeman, Nixon developed his Madman Theory during the 1968 campaign for the White House. Walter Isaacson, Kissinger: A Biography (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992), 163–64.

[22] Nixon’s efforts to appear unpredictable were targeted at the North Vietnamese and the Chinese, in particular, two critical Cold War interlocutors during his administration.

[23] Richard Reeves, President Kennedy: Profile of Power (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993), 197. Rand published a declassified copy of a memorandum in 2021 that many believe to be the one in question. Thomas C. Schelling, The Threat that Leaves Something to Chance (Santa Monica, CA: Rand, 1959), https://doi.org/10.7249/HDA1631-1.

[24] Schelling, Arms and Influence.

[25] The author does not claim that McChrystal rigorously reviewed the theories that underpinned his analysis. Furthermore, many officials at the time, including President Barack H. Obama, believed that McChrystal’s statement was released partly to put pressure on the president to endorse the deployment of additional troops.

[26] Gen Stanley A. McChrystal, “COMISAF’s Initial Assessment,” memorandum to Secretary of Defense Robert M. Gates, 30 August 2009.

[27] This interpretation assumes that McChrystal wanted the “importance of governance” to be “elevated” in the minds of Afghan leaders. McChrystal may have had other parties in mind as well.

[28] McChrystal, “COMISAF’s Initial Assessment,” 1-1, 1-2.

[29] If McChrystal were able to alter force protection culture—a challenging task—even a perfect success might not lead to an improvement in the trajectory of the reconstruction effort.

[30] Stephen Van Evera, Guide to Methods for Students of Political Science (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997), 7–8.

[31] For many years, the U.S. Naval War College curriculum addressed the constructivist, realist, and liberal institutionalist schools of international relations theory.

[32] Since the physical sciences offer convenient references, examples are taken from cosmology and astronomy.

[33] This could be a threat to either the physical integrity of the deterrent (the threat of destruction of nuclear military assets) or the psychological integrity of the deterrent (if the United States attacks Soviet nuclear forces in Cuba without reprisal, American leaders might feel greater latitude to do so in the future).

[34] For an example of the chart’s imprecision: the three bulleted notional theories in the leftmost box are connected by a single arrow to the spectrum. There is no intuitive reason to believe the three theoretical references in the first box would correspond to the same point on the spectrum.

[35] Ernest R. May and Philip D. Zelikow, ed., The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House during the Cuban Missile Crisis (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), 260.

[36] Fred Kaplan, The Wizards of Armageddon (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1983), 88.

[37] At the Naval War College, the Joint Military Operations Department curriculum addresses commander’s intent.

[38] Among other examples, see Daniel W. Drezner, “Back to Iraq,” Foreign Policy, 10 January 2003.

[39] Nikolas K. Gvosdev, Jessica D. Blankshain, and David A. Cooper, Decision-Making in American Foreign Policy: Translating Theory into Practice (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2019), https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108566742, offers a discussion of cognitive biases. See ch. 4, “Cognitive Perspective,” 88–124.

[40] For a discussion of Churchill’s suspicions of Germany from the moment he became First Lord of the Admiralty in October 1911, and how he viewed Germans as “l’ennemi,” see John Charmley, Churchill: The End of Glory (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1993), 72–76.

[41] Tim Judah, Kosovo: War and Remembrance (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000), 4–8.

[42] The risk of relying on preferred cases, or analogies, is discussed in Yuen Foong Khong, Analogies at War: Korea, Munich, Dien Bien Phu, and the Vietnam Decisions of 1965 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992).

[43] For an overview of selection bias and a guide to further references, see Kris Inwood and Hamish Maxwell-Stewart, “Selection Bias and Social Science History,” Social Science History 44, no. 3 (2020): 411–16, https://doi.org/10.1017/ssh.2020.18.

[44] Philip E. Tetlock and Aaron Belkin, eds., Counterfactual Thought Experiments in World Politics: Logical, Methodological, and Psychological Perspectives (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996), 23.

[45] For the argument that Westmoreland “never understood this reality,” in Stanley Karnow’s words, see Karnow, Vietnam: A History (New York: Penguin Books, 1983), 478.

[46] In its Foreign Policy Analysis course, the Naval War College offers course material on organizational biases and the impact of biases on assessments.

[47] John W. Dower, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II (New York: W. W. Norton, 2000).

[48] George W. Bush, Decision Points (New York: Crown, 2010), 205.

[49] Why the Afghan Government Collapsed, SIGAR 23-05-IP (Crystal City, VA: Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, 2022), 51.

[50] Why the Afghan Government Collapsed.

[51] Graham Slater, Preponderance in U.S. Foreign Policy: Monster in the Closet (Lanham, MA: Lexington Books, 2018).

[52] Rory Stewart and Gerald Knaus, Can Intervention Work? (New York: W. W. Norton, 2012). This volume was published after McChrystal’s assessment, but it exemplifies the alternative theories one might have looked for.

[53] For an overview of anthropologists’ reservations regarding Afghanistan’s post-

invasion prospects, see Alexander Star, “What the Anthropologists Say,” New York Times, 18 November 2011.

[54] Richard Holbrooke concluded that the 1995 negotiations to end the fighting progressed only once NATO bombs began to fall, saying the bombing “made a huge difference.” See Holbrooke, To End a War (New York: Modern Library, 1999), 104. Many argue that is was actually Croat and Bosnian military advances, and not NATO airstrikes, that changed Milošević’s mind in 1995.

[55] Stephen T. Hosmer, Why Milosevic Decided to Settle When He Did (Santa Monica, CA: Rand, 2001), 25–29.

[56] For example, Robert Pape’s book on coercion, published in 1996 and widely read prior to Operation Allied Force, would have offered reasons to doubt the wisdom of the strategy. Pape predicts that punishment strategies like the one NATO used in 1999 are likely to fail. Robert A. Pape, Bombing to Win: Air Power and Coercion in War (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1996); and Andrew L. Stigler, “A Clear Victory for Air Power: NATO’s Empty Threat to Invade Kosovo,” International Security 27, no. 3 (Winter 2002/3): 124–57.

[57] Barnett R. Rubin, The Fragmentation of Afghanistan: State Formation and Collapse in the International System, 2d ed. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2002), 248–57. Quotation from p. 255. The first edition was published in 1995, prior to the American invasion.

[58] Stephen Tanner, Afghanistan: A Military History from Alexander the Great to the War against the Taliban (Philadelphia, PA: Da Capo Press, 2002), 320.

[59] Martin J. Sherwin, Gambling with Armageddon: Nuclear Roulette from Hiroshima to the Cuban Missile Crisis (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2020), 79–81. See also Saki Dockrill, Eisenhower’s New Look National Security Policy, 1953–1961 (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996), 53–58.

[60] For the argument that Eisenhower’s nuclear posture was a bluff, see Evan Thomas, Ike’s Bluff: President Eisenhower’s Secret Battle to Save the World (New York: Back Bay Books, 2013).

[61] Joseph R. Biden, “Statement from President Joe Biden on Coalition Strikes in Houthi-Controlled Areas of Yemen,” press release, White House, 11 January 2024.

[62] Bruce Lawrence, ed., Messages to the World: The Statements of Osama bin Laden (London: Verso, 2005). See ch. 11 for the October 2001 bin Laden statement titled “Terror for Terror.”

About the Author

Andrew L. Stigler is an associate professor in the National Security Affairs Department of the Naval War College. His book Governing the Military was published in 2018. All views expressed are his own, and are not the views of any department or agency of the U.S. government.

https://orcid.org/0009-0003-0081-7846