China Military Studies Review

Understanding Weishe

China's System of Strategic Coercion

Daniel C. Rice

21 August 2025

https://doi.org/10.33411/cmsr2025.01.001

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is increasingly calling on the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to build a strong strategic weishe force system to achieve political objectives short of war. Often called gray zone, deterrence, or sometimes coercive activities by Western analysts, the PLA uses the term strategic weishe to discuss a broader set of capabilities and military activities meant to make an opponent submit to their will. This article unpacks the concept of strategic weishe and its application in PLA activities and builds a framework for us to better understand the CCP’s envisioned system of strategic coercion.

Keywords: People’s Liberation Army, PLA, weishe, coercion, deterrence, compellence, gray zone, escalation, quasi-war

In October 2022, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) held its 20th National Congress of the CCP. The event takes place once every five years, acts as a critical event in which the CCP reports back the work of the past Party Congress, and sets the strategic guidance for the next five years and beyond. Section 12 of the work report of 20th National Congress is titled “Achieve the goal of the centenary of the founding of the army and create a new situation in national defense and military modernization.”[1] Within this section, the CCP forecasted several requirements of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to include:

Build a strong strategic weishe force system, increase the proportion of new domain and new quality combat forces, accelerate the development of unmanned intelligent combat forces, and coordinate the construction and use of network information systems.[2]

While there are many terms within this section of the report that are worth exploring, one in particular is the focus of this article: “build a strong strategic weishe force system” (强大战略威慑力量体系). To fully understand what Xi Jinping is asking of the PLA, we first must understand what is meant by the term weishe and then understand it in the context of a system of weishe. Weishe as a concept can be roughly translated as some combination of deterrence, compellence, or perhaps more aptly, coercion. These terms are difficult enough to fully grasp in English, let alone in a translation from a different language. However, weishe and China’s “strategic weishe force system” or “system of strategic weishe” can be fundamentally understood by authoritative texts that exist in open literature. This is particularly true for the role of the People’s Liberation Army in the application of weishe. Through careful analysis of available PLA texts and other Chinese sources, we can create a mental framework to describe China’s views of weishe and China’s “system of strategic weishe,” especially regarding its military application.[3]

Often when China analysts discuss Chinese deterrence, coercion, or gray zone activities it is through classifying Chinese activities into our understandings of these concepts. By doing so, we may inject confusion into the discussion and cause imprecision in the way in which we describe the People’s Liberation Army’s actions. This article aims to bring to light the conceptual foundation of weishe and to build a framework from which we can discuss Chinese deterrence, compellence and coercion activities with more specificity. In part, this is done by discarding interpretation of the term weishe and probing the fundamental concept and theories surrounding it. To do this, the article draws most of the information from the 2013 and 2020 editions of The Science of Military Strategy, as well as Lectures on the Science of Space Operations, Service and Arms Applications in Joint Operations, Lectures on Joint Campaign Information Operations, and other key Chinese texts. By using these sources, the article first defines the idea of strategic weishe and tracks the conceptual development of weishe through the history of the CCP. Then, the article explores the modern application of strategic weishe, defining the domains and application of weishe according to the perceived phase of conflict. Next, the article examines how the PLA, across domains, envisions a spectrum of intensity for its weishe activities. From an understanding of the spectrum of intensity, the article explores in detail each of the weishe domains and the corresponding weishe activities across the spectrum of intensity. This includes exploration of the five main modern domains of weishe: nuclear, conventional, space, information, and people’s war. Finally, the article expands on the idea of the system of strategic weishe and integrated weishe to describe how each of these domains and other nonmilitary domains theoretically integrate to give the CCP options to achieve political objectives across the spectrum of conflict.

It is the author’s hope that by laying bare the conceptual foundation of weishe that it may help the U.S. Armed Forces and decisionmakers preserve decision-making space vis-∵-vis the CCP and PLA. By more accurately understanding the intent, messaging and activities surrounding weishe, we can better tailor our responses and manage the escalation ladder as we face these kinds of activities and threats. To do so, we must first understand the concept of weishe and its application in modern PLA activities.

China’s Strategic Weishe: Zhanlue Weishe (战略威慑)

Strategic (战略), weishe (威慑), and strategic weishe (战略威慑) all have slightly different linguistic meanings in the context of the People’s Liberation Army as compared to their English translations and usage. Strategic thinking is defined by the 2020 Science of Military Strategy as:

A rational understanding of the overall issues of military strategy. It is a scientific revelation of the objective and guiding laws of the use and construction of military forces. It has distinctive characteristics such as politics, times [时代性], innovation, guidance [指导性], and inheritance [继承性]. Strategic thinking embodies the fundamental position, viewpoints and guiding principles of the party and the country in understanding military issues, especially war issues, and is the theoretical basis for establishing military strategies.[4]

Strategic (战略) thinking includes the views of the party that encompasses a broader whole-of-society view. For the CCP, strategic resources and capabilities can refer to aspects of the country’s comprehensive national power (综合国力) (CNP) comprised of: economic, political, military, cultural and technological power.[5] Weishe (威慑) (roughly vocalized as way-sure), typically translated as deterrence and sometimes translated as coercion, is another term with a slightly different meaning than its English translation. That is not to say that it is a completely foreign concept, but that the interpretation of the term changes based on context. This speaks to the concept of weishe containing a slightly broader spectrum of meaning. According to Western analysts, it is generally accepted that weishe incorporates aspects of deterrence, compellence, and coercion, and weishe may more closely resemble Thomas C. Schelling’s expanded definition of coercion.[6] When combining strategic and weishe together, PLA writers note that “strategic weishe has two basic functions: One is, through weishe, to halt the other party from doing what you don’t want them to, and the other is through weishe to coerce/compel the other party into having to do something. The essence of both (uses) is to make the other side submit to the will of the party conducting weishe (威慑者).”[7] From the PLA definition, it may be most appropriate to call weishe deterrence, compellence, or coercion, depending on the context. It is worth noting that, over time, Chinese authors and military strategists have used different terms to describe similar phenomenon; however, weishe appears to have been selected as the primary term to describe this concept. [8] Simply put, Chinese strategic weishe is a set of strategic-level capabilities and activities, with an emphasis on the military, meant to induce an adversary to accede to China’s political objectives.[9] Weishe is also seen as a type of quasi-war, that is a form of confrontation that spans the spectrum of conflict, and weishe military activities fall under a broader category of quasi-war military activities.[10]

The foundations of strategic weishe are not so dissimilar to those of classic Western deterrence theory. The 2020 Science of Military Strategy defines the requirements of having effective strategic weishe as possessing the “capability/strength, determination, and communication” to use military means for a political objective.[11] Even though the Chinese model of strategic weishe follows the Western deterrence equation, in practice Chinese strategic weishe may be implemented in a somewhat different or unexpected way. For example, an oft-used quotation by Mao Zedong states that “the U.S. atomic bomb cannot scare the Chinese people. My country has a population of 900 million and 9.6 million square kilometers of land. The U.S. atomic bombs cannot wipe out the Chinese people. If the U.S. with planes and atomic bombs launches an invasion of China, then China with millet and rifles will surely win.”[12] At the time, the U.S. State Department interpreted this as an attempt to communicate the infallibility of the Chinese revolutionary spirit.[13] From the Chinese perspective, this statement leveraged the People’s War and comprehensive national power elements of strategic weishe and was one of the earliest successful applications of what would come to be called integrated weishe.[14]

The modern concept of strategic weishe (战略威慑) is still evolving and now incorporates integrated weishe [整体威慑]; yet, at its core, strategic weishe still uses the military as its foundation.[15] In China’s grand strategy, strategic weishe is the primary way to use military force to achieve political objectives short of war with integrated weishe as an evolution of the concept that emphasizes a more active role for nonmilitary weishe capabilities. The application of both strategic weishe and integrated weishe will be examined at the end of this article.

For the purposes of this article and to reduce the issues of misinterpretation, the term weishe will primarily be used to describe the concept of strategic weishe in lieu of deterrence, compellence, or coercion. By doing so, this article aims not to compare and contrast the Chinese concepts with their Western counterparts, but rather it seeks to lay bare the Chinese conceptual framework of strategic weishe.

The History and Evolution of Weishe

As a concept, and much like other strategic concepts in China, weishe has evolved as new leaders have adapted and developed their thinking or theories on the subject. For the concept of weishe, there are three distinct periods of time that have emerged as each leader expanded the concept of weishe by either adding specific weishe domains or modified the application of weishe in strategy.

Beginning with Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping, weishe was used to dissuade adversaries from invading or attacking China. To accomplish this, both leaders used war preparation, which involves building the military and the military industrial complex, as a primary way to dissuade larger powers from allowing regional wars to spill over into China. Throughout this period, China was encircled by war. The War to Resist U.S. Aggression and Aid Korea (Korean War), the War to Resist U.S. Aggression and Aid Vietnam (Vietnam War), the counterattack in self-defense against India (Sino-Indian War), the counterattack in self-defense on Zhenbao Island (Sino-Soviet border conflicts), and the counterattack in self-defense against Vietnam (Sino-Vietnamese War) all occurred during this time.[16] In each instance of war on China’s periphery, from the Chinese perspective, the focus was on using military preparation and offensive campaigns as a means to stop the United States, India, the Soviet Union, and Vietnam from extending the battlelines into China’s homeland. Mao and Deng’s theories on weishe added nuclear weishe and People’s War weishe to war preparation, expanding the ways in which China could apply weishe. Nuclear weishe at its core was meant to break the perceived nuclear monopoly held by China’s potential adversaries such as the United States, Soviet Union, and later on India.[17] People’s War weishe, or mobilization of the masses, is credited by Chinese strategic thinkers as being the primary method of successful mobilization against the United States during the Korean War, and the primary deterrent to a potential Soviet invasion during the border clashes of the 1960s.[18]

Weishe’s second conceptual development phase came under Jiang Zemin. During Jiang’s tenure as the chairman of the Central Military Commission, he elevated weishe to a strategic level, hence the term strategic weishe.[19] Jiang’s interpretation of the importance of weishe built on his predecessors, taking nuclear weishe as a core capability and emphasized the need to study and develop a credible conventional military weishe capability. Jiang postulated that, “preparing (the military) to fight and win is the foundation of successful weishe, and successful weishe is the ideal state for winning the war; no matter if it is weishe or winning, for preparing for war the requirements are the same.”[20] Included within this, Jiang called for the construction of a “modern operational system that is in accordance with requirements of high-tech wars.”[21] The new system would “form a strategic weishe system complemented by multiple means in a step-by-step fashion.”[22] This incremental or step-by-step fashion laid the foundations for applying weishe across an intensity spectrum. Jiang also stressed the need to adopt people’s war to the new “high-tech” conditions.[23] In addition, he expanded the concept of weishe to emphasize the role of comprehensive national power in an overall weishe capability. It appears that during his tenure as general secretary of the CCP, Jiang assessed the PLA as relatively weak, and therefore China needed to emphasize building comprehensive national power to deter its adversaries from initiating conflict with China.

Table 1. Weishe under different CCP general secretaries

| Period |

Core leaders |

Effect on weishe |

Weishe objectives |

|

Founding of New China 1949–80s

|

Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping

|

Emphasizing war preparations, nuclear and People’s War weishe as the foundations for weishe

|

Preemptively stop border wars and conflicts from spilling over into China

|

|

1980s–the New Era (2010s)

|

Jiang Zemin and early Hu Jintao

|

Elevating weishe to a strategic level and integrating comprehensive national power as the base strength for weishe, growing recognition of the need for enhanced conventional military weishe

|

Contain, delay the outbreak of, or stop the escalation of war

|

|

The New Era (2010s–present)

|

Late Hu Jintao and Xi Jinping

|

Focus on building operational conventional military weishe capabilities under informationized conditions, inclusion of space and information weishe domains, introduction of military-civil fusion to enhance integrated weishe

|

Safeguard the “period of strategic opportunities,” prevent and contain crisis, build a force capable of fighting and winning local wars under informationized conditions as the basis for weishe

|

Source: Shou Xiaosong, ed., The Science of Military Strategy, 2013, trans. China Aerospace Studies Institute (Maxwell, AL: China Aerospace Studies Institute, Air University, 2021), 177–78.

During the third period, which began in the so-called “New Era” toward the end of Hu Jintao and solidified under Xi Jinping, the emphasis became enhancing military capability and the role of conventional military weishe in China’s strategy. The objective of conventional military weishe became to safeguard the “period of strategic opportunities.”[24] Furthermore, the emphasis fell on “enhancing weishe and actual combat capabilities under informationized conditions as the fundamental starting point.”[25] In concrete terms, this meant that “the weishe capability under informationized conditions is highlighted and expressed as a system operational capability based on information systems.”[26] The focus on military capability under informationized conditions is likely the reason for the addition of space and network/information weishe to the overall strategic weishe system. These two domains are still under development, and with Xi Jinping’s emphasis on “intelligentization,” they are likely to expand in the future.

From the historical backdrop and evolution of strategic weishe, the modern definition has landed on five specific domains in which the PLA focuses. These strategic weishe domains are conventional military, nuclear, space, information, and People’s War.[27] Before exploring each domain in detail, it is necessary to understand how weishe is applied in practice.

The Implementation of Strategic Weishe

Strength is the basis of strategic weishe, and in Chinese writings strength is calculated based on hard power and soft power, with the core of hard power being the military.[28] Soft power is defined as the nonmilitary aspects of comprehensive national power to include political, economic, diplomatic, technological, and cultural power.[29] In strategic weishe, the soft power aspects of comprehensive national power are used to set conditions and shape the overall situation as well as to amplify military weishe activities.[30] As such, where nonmilitary or soft power aspects of comprehensive national power are used to shape conditions, hard military power is relied on to actively exploit or otherwise change the situation through the use of force. With its implementation, strategic weishe also appears to be considered as a directed effect on a specific adversary.

As the 2020 Science of Military Strategy puts it: “If strategic weishe is to create a weishe effect, it must be manifested through strategic weishe military activities.”[31] And this is consistent with theory on modern PLA operations in which military weishe (军事威慑) activities fall under a set of larger activities called quasi-war activities. Quasi-war activities, “are between war and non-war military activities, and mainly include military weishe (军事威慑), border control, establishment of no-fly zones and limited military strikes.” In this context, military weishe is defined as a subset of strategic weishe activities carried out by the military that are “a form of military conflict (斗争) that forces (an adversary) to concede, compromise or submit.”[32] Furthermore, military weishe activities are a fairly well-defined set of activities across the five modern strategic weishe domains. PLA authors also suggest that military weishe activities have some benefit as opposed to engaging in conflict outright. Most notably, military weishe activities are seen as lower-intensity, lower-cost, and more flexible military options compared to outright war.[33] Part of this assessment comes from the applicability of military weishe activities in different phases of conflict.

Table 2. Implementation of strategic weishe based on the situation

|

Time

|

Primary type of weishe

|

Effect

|

Description

|

|

Peace

|

Integrated weishe to strengthen military weishe

|

To set favorable conditions for achieving political objectives

|

Stabilize/shape/preventive deterrence

|

|

In-between peace and war/crisis

|

Emphasis on applying military weishe with comprehensive national power in support

|

To make your opponent submit to your will; to contain or control the outbreak of a crisis/war

|

Normalized deterrence/high-intensity coercion and compellence

|

|

War

|

Aggressive use of military weishe

|

To radically alter the course of the war and shift the momentum in your favor

|

Momentum-changing nonkinetic and kinetic strikes/compel adversary

|

Sources: Shou Xiaosong, ed., The Science of Military Strategy, 2013, trans. China Aerospace Studies Institute (Maxwell, AL: China Aerospace Studies Institute, Air University, 2021), 136, 169; and Xiao Tianliang, ed., The Science of Military Strategy, 2020 (Beijing: National Defense University Press, 2020), 132.

The implementation of military weishe activities in each domain does not stop at the onset of war, but rather, the PLA sees the use of military weishe at any point along the Chinese spectrum of conflict during peace, conflict, and war.[34] During the different phases of conflict, the overall mix of strategic weishe changes slightly with an escalating emphasis on military weishe the closer to wartime the CCP perceives itself to be. In peacetime, the primary goal of strategic weishe is to leverage all levers of comprehensive national power to strengthen military weishe and shape China’s internal and external environment to continue national development and to delay or stop the outbreak of war.[35] In essence, the peacetime application of strategic weishe is meant to stabilize or shape the internal and external situation and invoke preventive deterrence through military weishe against potential adversaries.[36] During a crisis, strategic weishe is applied to control the crisis, to create room to maneuver for other political agreements, or to either stop the outbreak of war or to successfully position forces to step-off into and seize the initiative in war especially in the first battle.[37] Strategic weishe in this phase is more reliant on military weishe activities, which are meant to control a crisis that may erupt, deter an adversary from taking further action, or to coerce an adversary into abandoning their objectives, all while positioning the PLA to best be prepared for war.[38] During wartime, strategic weishe relies on military weishe activities to either shift the momentum of the war or to cause significant psychological damage to their adversary such that they are deterred from continuing the fight.[39] Surgical strikes are defined as the application of strategic weishe during war.[40] Wartime military weishe activities “force an opponent to acknowledge the difficulties and terminate when seeing danger.”[41]

Across different military weishe activities, there is a strong emphasis on flexibly using capabilities and on strict control of the escalation ladder.[42] Based on the timing, whether in peace, crisis, or war, the types of military weishe activities and capabilities employed have a corresponding intensity. The basic exemplar types of military weishe activities as described in the 2020 Science of Military Strategy include creating an atmosphere of war [营造战争气氛], displaying advance weapons [展示先进武器], carrying out military exercises [举行军事演习], adjusting military deployments [调整军事部署], increasing war preparation levels [提升战备等级], carrying out information attacks [实施信息攻击], using military activities to restrict an opponent [限制性军事行动], and using military strikes of a warning nature [警示性军事打击].[43] For most of these activities, there are corresponding times and escalations associated with carrying out the military weishe activity that can be described as a relative intensity of the activity. Furthermore, the military weishe activities can be placed along an escalation spectrum. A notable exception to this is creating an atmosphere of war that has its own spectrum of escalating subactivities.[44] The exemplar activities also reinforce the idea that weishe as a concept encompasses deterrence, compellence, and coercion, and depending on the intensity and timing of the weishe activity may be interpreted into English differently.

A spectrum of intensity and a gradual ramping up of activity intensity is reflected across descriptions of military weishe activities found in various texts that describe specific strategic weishe domains. For example, military weishe activities conducted by air forces are “hierarchical, and it is possible to differentiate air weishe, in accordance with differences in their intensity, into: low-intensity displays to deter the enemy, medium-intensity high pressure to deter the enemy, and high-intensity small strikes to deter the enemy.”[45] Furthermore, “[we] usually should try to achieve the goal of containing antagonists at fairly low levels [of weishe]. If we cannot resolve issues in an effective manner, [we should] incrementally increase the level of weishe.”[46] Similar discussions of spectrums of military weishe activities and their corresponding intensity can be found for the conventional military, space, and information domains. For example, in Lectures on the Science of Space Operations, the authors discuss the spectrum of intensity as the ability “to enhance the weishe effects, space weishe when applied usually adopts the method of gradual escalation, to constantly increase the degree of force in weishe of the enemy.”[47] While The Science of Military Strategy paints the conceptual framework of a spectrum of activities at the strategic level, more service-oriented or operational texts such as Lectures on the Science of Space Operations and Lectures on Joint Campaign Information Operations often provide detail on specific weishe activities in each domain.[48] It is possible that other texts not covered in this research or that are under development further flesh out the specific domain activities of other services beyond the PLA Air Force (PLAAF). For example, there appears to be a current CCP call for increasing the strategic weishe capabilities of the PLA Navy as evidenced through party reports.[49] It is likely that, if discovered or written, a PLA Navy-specific text on weishe would also incorporate a ramping spectrum of activities that are maritime centric.

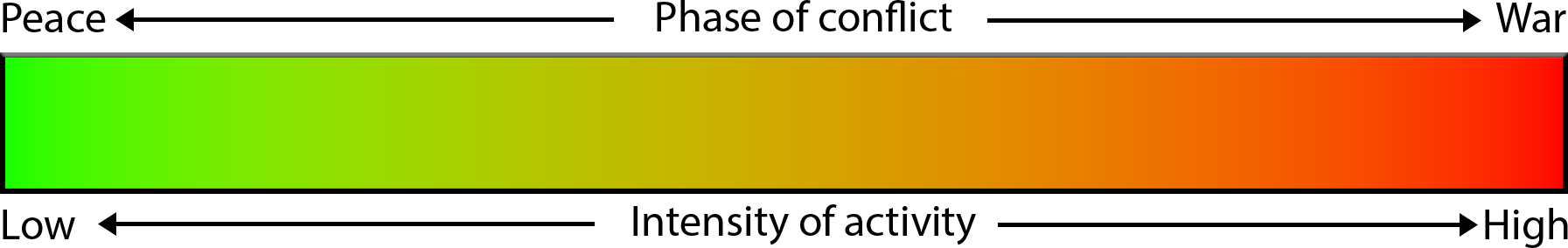

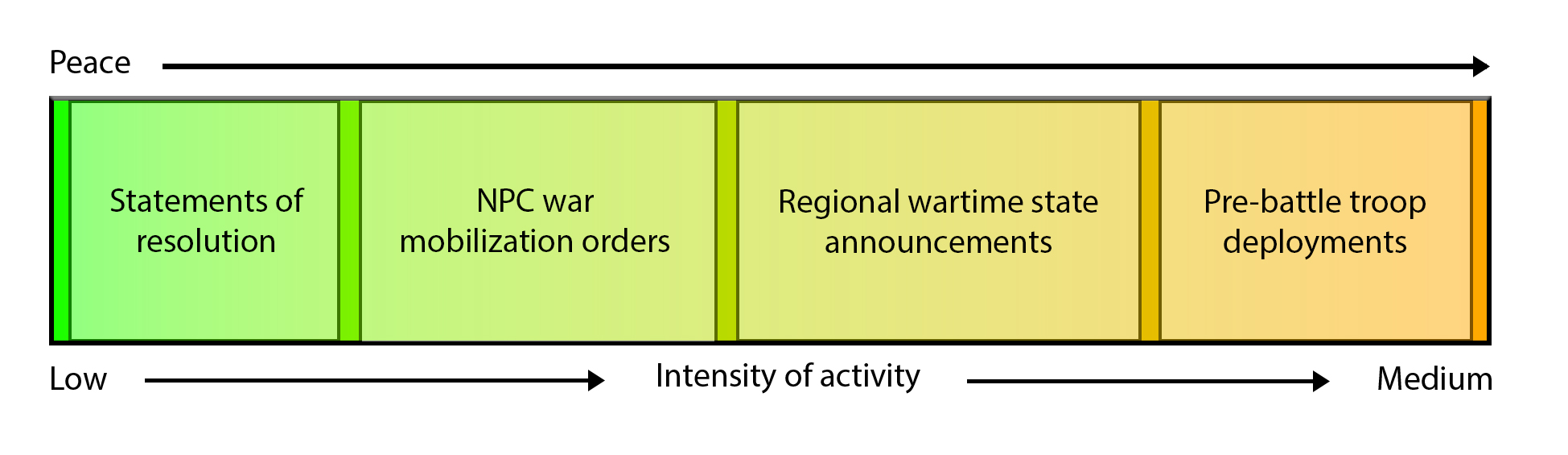

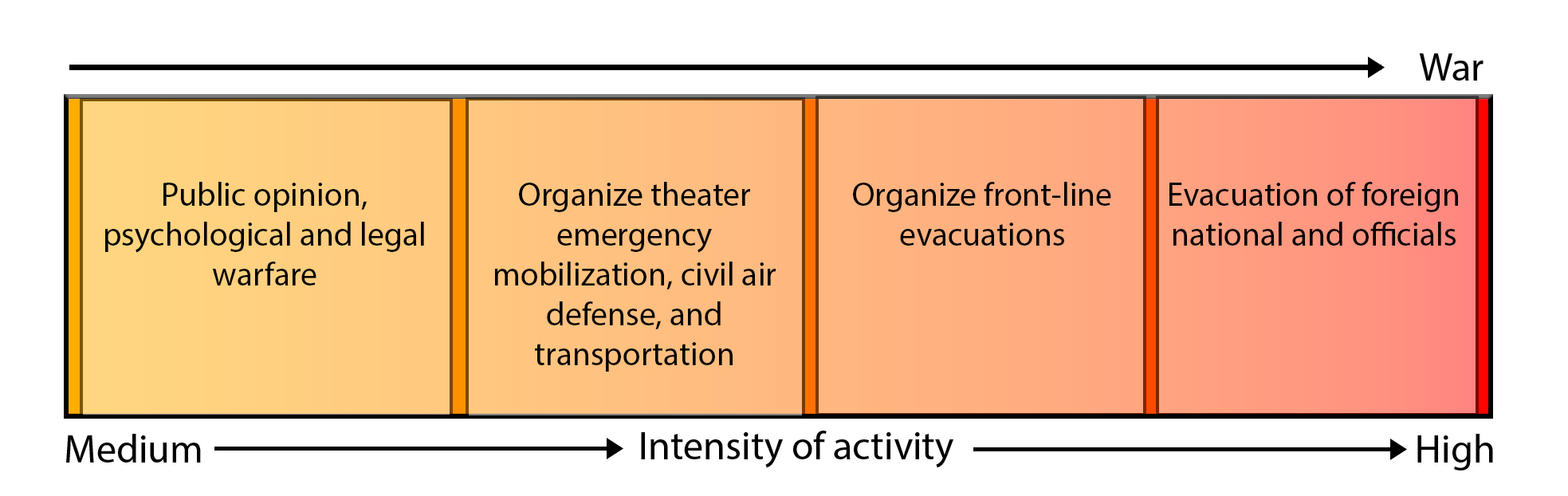

The language and concepts used to describe a ramping spectrum of activities, even by different authors, is quite consistent. Throughout the different texts and across domains, the highest intensity of military weishe activity generally includes limited kinetic strikes, or as the exemplar military weishe activities describes, “military strikes of a warning nature.” This is in line with the crisis or wartime application of strategic weishe, which aims to position the military in the best possible position to step into war, or to induce a war-changing momentum shift.[50] From the concept of intensity, we can create a relative spectrum of intensity to apply to military weishe activities in each strategic weishe domain (figure 1).

Figure 1. Weishe activity spectrum

Source: courtesy of the author, adapted by MCUP.

Conceptually framing the different military weishe activities across an intensity spectrum can help to understand the role of each independent strategic weishe domain. While mostly separate in execution, it is emphasized to “pay attention to the comprehensive use of each type of weishe method, which forms an effective weishe system, and produces a comprehensive deterrent effect on the adversary.”[51] With this in mind, the sum of the parts creates a whole integrated effect. Each strategic weishe domain also has its own unique characteristics which impacts its use in strategic weishe.

Modern Types of Weishe

The 2020 Science of Military Strategy breaks strategic weishe into five distinct domains: conventional military, nuclear, space, information, and People’s War.[52] According to the text, “each of these different weishe domains have some overlap, but they are fairly independent in their application.”[53] It is worth noting that “the types of weishe expands with the development of science and technology,” and therefore the five categories enumerated in the 2020 Science of Military Strategy are not exhaustive, but should be used as a starting point to understand China’s evolving strategic weishe capabilities.[54] This is especially true with the introduction of the term integrated weishe and the expansion of capabilities in new fields such as artificial intelligence (AI), drones, and others. Importantly, strategic weishe domains appear to be defined by the effects of specific activities.[55] This means, for example, that to be considered nuclear weishe one does not need to be a nuclear military unit, but any military unit that undertakes a strategic weishe military activity that impacts nuclear weishe would be considered as such. Likewise, a PLA Army unit that is undertaking information operations would be considered exercising military weishe activities in the information weishe domain. The current focal strategic weishe domains as of 2020 and their associated operational activities are outlined below.

Nuclear Weishe (核威慑)

According to the history of weishe, “the overall weishe power of People’s War along with nuclear weishe are the basic methods of China’s strategic weishe.”[56] Part of the rationale is that without at least a basic nuclear capability, China would be beholden to overt pressure from nuclear armed states. However, the ideal number of Chinese nuclear weapons required to achieve nuclear weishe is dependent on global conditions. For Chinese strategists, there is a critical lesson learned from the Soviet Union’s arms race with the United States, in which nuclear weapons were one significant component. Unlike the Soviet Union, Chinese strategists believe that they should not engage in an arms race or, by extension, overinvest in nuclear weapons.[57] It is implied that this may cause an imbalance or damage to the Chinese economy, and more recently Xi Jinping has reiterated that the economy and military should be balanced.[58] As such, China sees that “nuclear weishe thinking arises as the times demand. The use of nuclear weishe is based upon the level of development in the nuclear strength of nuclear capable countries.”[59] In plain terms, Chinese strategists view the required number of nuclear weapons to effectively achieve nuclear weishe as dependent on the number of nuclear weapons possessed by potential adversaries. There is also an abstract cap on quantity of nuclear weapons discussed as “limited and effective” such as to achieve a “medium strength nuclear weishe.”[60] The intended effect of the medium-strength nuclear weishe capability is to “cause on your opponent a certain degree and unacceptable mutual destruction threat.”[61] According to the PLA theory, once nuclear weishe has been achieved, it opens opportunities for the use of other weishe domains and limits the risk of escalation to nuclear war. Other methods of weishe include a more aggressive use of conventional military weishe, as “due to the increasing number of countries possessing nuclear weapons, conventional wars are often conducted under nuclear weishe, and their strategy is also a conventional war strategy under nuclear weishe conditions.”[62]

Although nuclear weishe is a near prerequisite for the application of other types of weishe, there are likely specific weishe activities that can be taken in escalatory steps. The PLA Rocket Force (PLARF), “employs ground-based fires of guided missile systems to carry out combat missions . . . possesses nuclear counterattack and medium and long-range conventional precision fires . . . and is the core capability of China’s strategic weishe.”[63] In its operations, the PLARF has several different military activities that it can use to escalate or otherwise reinforce strategic weishe. These activities are discussed in the context of conventional warheads; however, the nonstrike and potentially higher-intensity activities may apply to nuclear forces. This is particularly true in the case of PLARF systems that appear to be dual-capable such as the Dong Feng-21 (DF-21), DF-26, DF-31, or DF-41 medium, intermediate, long-range, and intercontinental ballistic missiles, where tests or limited conventional warhead strikes may be used as a confirmation of the capability to deliver the same strike with a nuclear-tipped missile.[64] Therefore, conventional PLARF military weishe activities can have an effect on nuclear weishe. Furthermore, there are at least indications that facing an insurmountable loss or a threat against the CCP regime’s survival that the CCP could alter its nuclear policies to allow for nuclear strikes.[65] This could involve China’ s leadership reducing the nuclear threshold when it is perceived that an adversary is about to make a crippling strike against Chinese assets.[66]

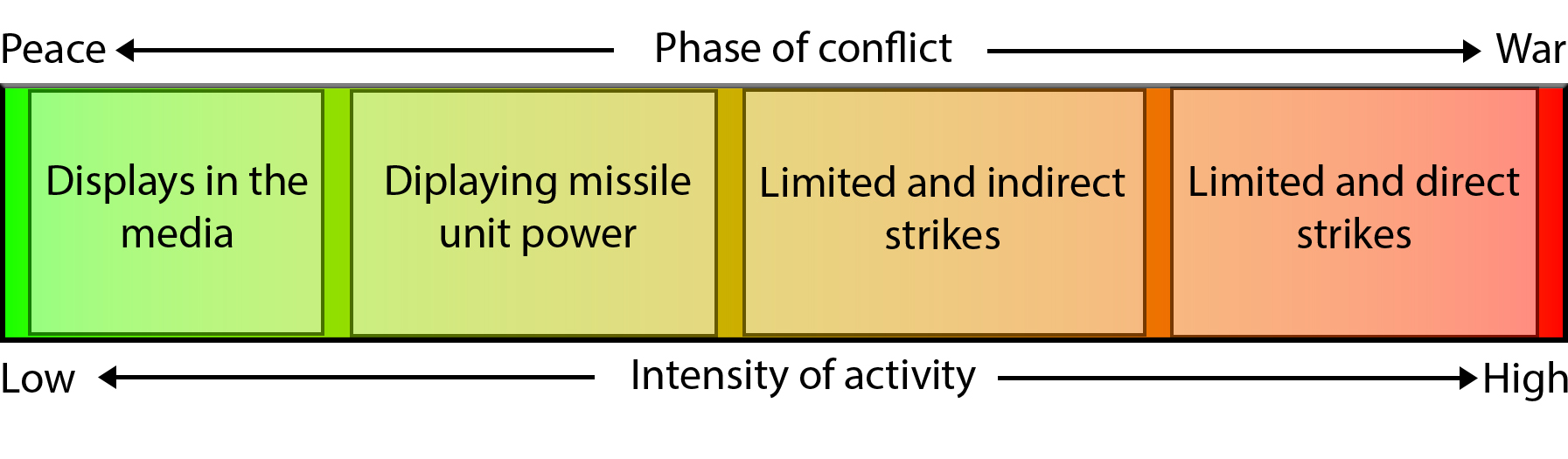

The military weishe activities conducted by the PLARF are as follows: displaying missile units in public media [舆论媒体展示导弹部队], displaying the power of missile units to an appropriate degree [适度显示导弹部队实力], limited and indirect missile firepower strikes [有限间接导弹火力打击], and limited and direct missile firepower strikes [有限直接导弹火力打击].[67] Once again, these are arranged across a spectrum of intensity of activity (figure 2).

Figure 2. PLA Rocket Force conventional weishe activities

Source: courtesy of the author, adapted by MCUP.

Several specific aspects of these activities are worth clarifying. First, displaying missile units to an appropriate degree includes missile systems tests into a designated land or sea area. However, these tests are not necessarily directed toward an individual country. This would be consistent with the 25 September 2024 test of what is assessed to be the DF-31AG solid-fuel, road-mobile intercontinental ballistic missile in the Pacific.[68] While this test was not necessarily targeted at a specific country, it was a demonstration of capability to the broader regional actors. This kind of missile test differs from limited and indirect missile firepower strikes. In limited and indirect missile firepower strikes, the so-called missile tests are intentionally fired into, over, or near a specific country’s territory or assets. As such, the August 2022 Joint Sword exercise, during which PLARF conventional missiles were shot over Taipei and into Taiwan and Japan’s exclusive economic zones, can be described as a military weishe activity of the limited and indirect missile firepower strike variety.[69] During the highest intensity military weishe activity, limited and direct missile firepower strikes, there are direct strikes against an adversary’s territory or assets. However, the strikes are limited in nature and are not the equivalent of a larger conventional missile strike operation called “missile firepower attacks and destruction.”[70] Again, within the text, these activities are only described as being conducted by PLARF conventional missile forces, with no mention of PLARF nuclear forces conducting either a limited and indirect or limited and direct missile firepower strike as part of nuclear weishe military activities. By looking at the PLARF conventional military weishe activities, we can build an understanding of some of the potential types of nuclear weishe military activities that can be employed for a strategic weishe effect.

Conventional Military Weishe (常规威慑)

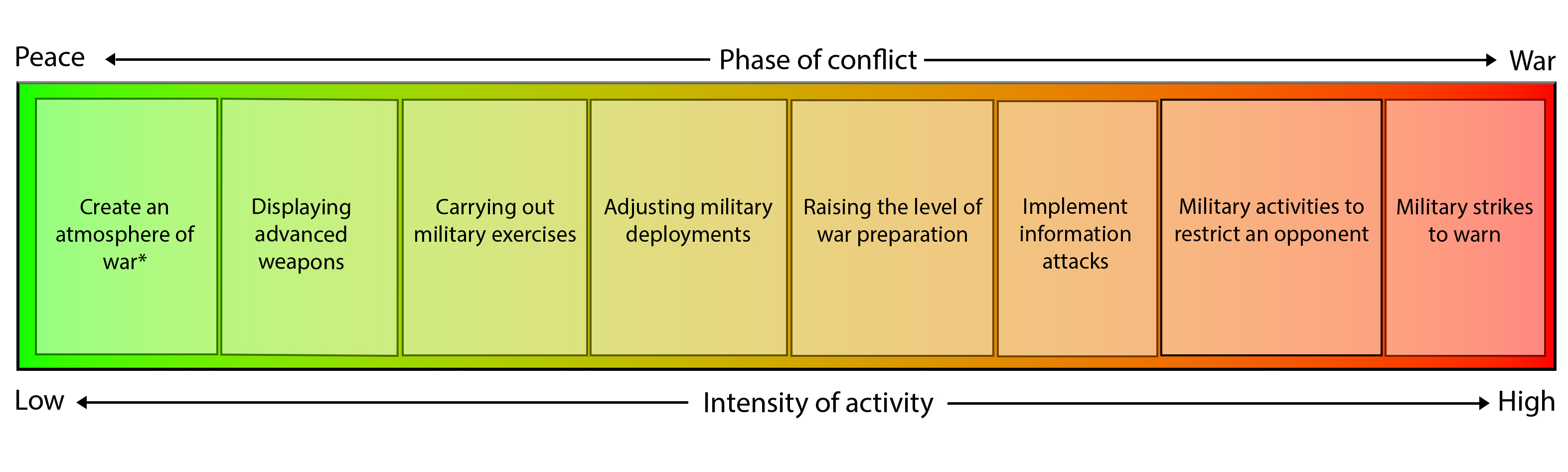

Conventional military weishe refers to the broad set of activities conducted by a military’s conventional, or non-nuclear, capabilities. As a domain of strategic weishe, it has a unique direct relationship with nuclear weishe in that without having credible nuclear weishe, the use of conventional military weishe becomes less effective or even ineffective. In this balance, PLA authors assess that currently conventional military weishe is on the rise. According to the 2020 Science of Military Strategy, “with the development of the times, the limitations of nuclear weishe are becoming increasingly apparent, and the use of conventional military weishe has once again become prominent.”[71] Conventional military weishe activities track closely with the exemplar strategic weishe military activities. Within that group, certain activities are most likely to apply to a jointly organized conventional force or individual service components. Those activities, according to intensity, include creating an atmosphere of war [营造战争气氛], displaying advanced weapons [展示先进武器], carrying out military exercises [举行军事演习], adjusting military deployments [调整军事部署], raising the level of war preparation [提升战备等级], implementing information attacks [实施信息攻击], using military activities to restrict an opponent [限制性军事行动], and deploying military strikes of a warning nature [警示性军事打击] (figure 3).

Figure 3. Conventional military weishe activities

Note: Creating an atmosphere of war has its own subset of activities that follow the escalation of intensity and is described in the People’s War weishe section of this article. As depicted in this graphic, creating an atmosphere of war refers to the lowest intensity of those kinds of activities.

Source: courtesy of the author, adapted by MCUP.

While there are no specific “joint conventional military” weishe activities found in available texts, there are several spectrums of independent service conventional military weishe activities. As mentioned before, PLARF conventional military weishe activities include: displaying missile units in public media [舆论媒体展示导弹部队], displaying the power of missile units to an appropriate degree [适度显示导弹部队实力], limited and indirect missile firepower strikes [有限间接导弹火力打击], and limited and direct missile firepower strikes [有限直接导弹火力打击].[72] These activities, conducted by conventional warhead-equipped PLARF forces could be conducted in conjunction with other services or used as stand-alone activities. Other PLA services and branches likely have their own set of activities that support a concept of “joint conventional military” weishe. Notably, the PLA Navy is actively building more capability to conduct conventional weishe activities, particularly when it comes to strategic access. According to PLA Navy writings, “when maritime strategic accesses are in a crisis stage or a potential crisis stage (for example, when a given maritime strategic accesses is blocked off by other countries) and when the PRC’s maritime strategic accesses are threatened, the PRC should fully show its firm resolve and bring military weishe into play.”[73] However, as previously mentioned, thinking on concrete weishe activities of the PLA Navy are likely still under development as there is a CCP internal emphasis on developing maritime weishe capabilities.[74] Conversely, the PLA Air Force, whose weishe activities are part of conventional military weishe, have their weishe activities laid out in detail in Service and Arms Applications in Joint Operations. In the broader category of conventional military weishe activities, the PLAAF and other service-specific spectrums of activities can be considered subcategories.

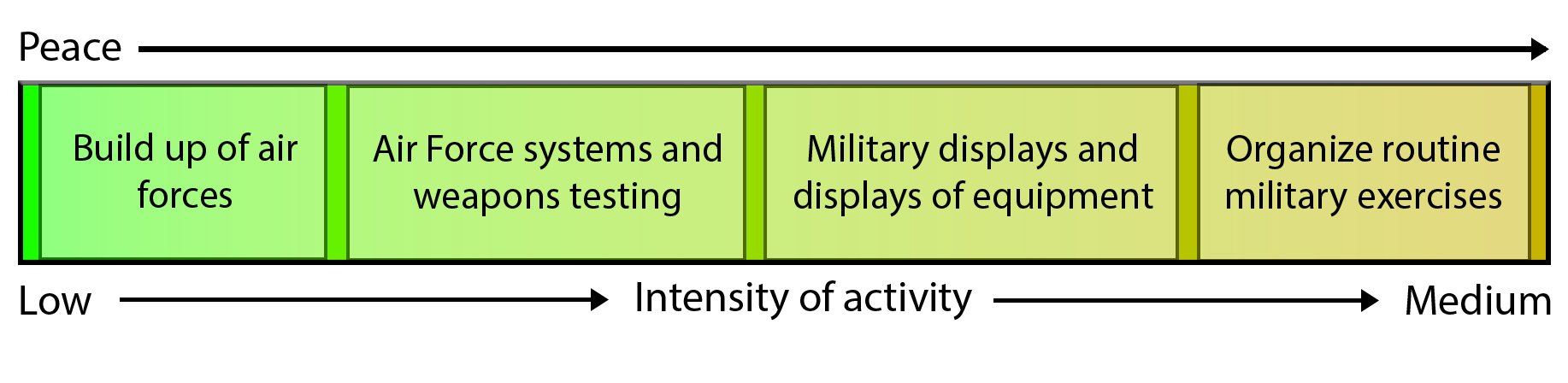

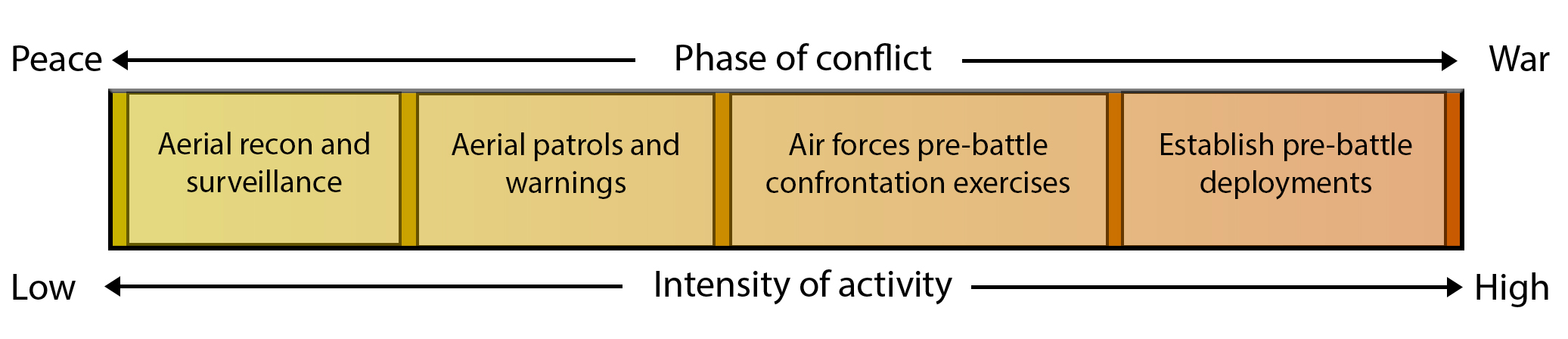

Within the PLA Air Force subcategory of conventional military weishe activities, activities are grouped into three levels: low-intensity, medium-intensity high pressure, and high-intensity small attacks.[75] Within these levels of intensity, there are scalable actions to undertake.

Low-intensity activities are comprised of a buildup of air forces [加强空军力量建设], air force systems and weapons testing [研制和实验新型空军武器装备], military displays and displays of equipment [军事表演和武器装备展示], and routine military exercises [组织日常军事演习] (figure 4).[76] Using this framework, events such as the Zhuhai Air Show (a.k.a. China International Aviation and Aerospace Exhibition), in which the PLAAF famously conducts military displays and displays of equipment, would be considered a low-intensity weishe activity.[77] These kinds of low-intensity weishe activities are likely meant to signal to an opponent the capabilities and the skills to employ those capabilities in combat-like scenarios. For this batch of activities, it may be appropriate to call them deterrent activities, but under the Chinese framework they would be called low-intensity weishe activities.

Figure 4. PLA Air Force low-intensity weishe activities

Source: courtesy of the author, adapted by MCUP.

Medium-intensity, high-pressure activities include organize aerial reconnaissance and surveillance [组织空中侦察和监视], organize aerial patrols and warnings [组织空中巡逻警戒], organize air forces prebattle confrontation exercises [组织临战空军士兵对抗演习], and establish prebattle deployments [建立临战部署] (figure 5).[78] For this set of activities, they may more appropriately be called compellent or coercive activities. Activities here may include the consistent large-scale incursions into Taiwan’s air defense identification zone (ADIZ), which could be classified as any one of the first three activities.[79] For establishing prebattle deployments and under the context of Taiwan, this likely includes the deployment of PLAAF brigades to forward airfields. The airfields are normally kept in high readiness, but without a permanently deployed brigade, and they are used as forward positions in high-tempo exercise periods. In the event of conflict, these airfields would be populated with a PLAAF brigade as their frontline airfield for conflict.[80] Therefore, if a PLAAF brigade more permanently deploys to these locations, and does not reset to their home airfield post-exercise, it may indicate the establishment of pre-battle deployments.

Figure 5. PLA Air Force medium-intensity, high-pressure weishe activities

Source: courtesy of the author, adapted by MCUP.

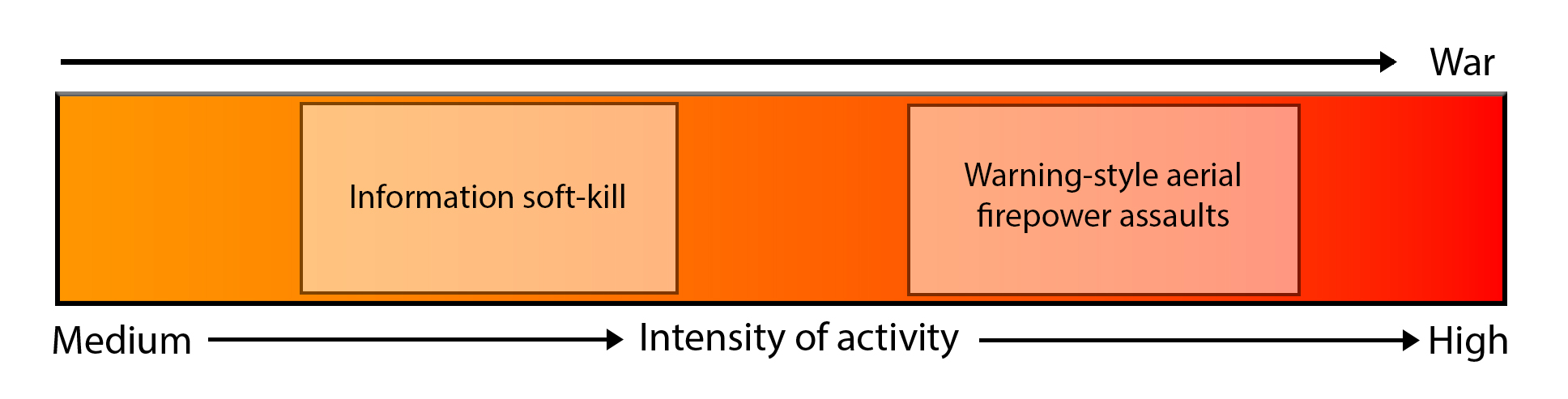

High-intensity, small-strike weishe activities include information soft-kill [信息软杀伤] and warning-style aerial firepower (surprise) assaults [警示性空中火力突击] (figure 6).[81] These activities are fairly straightforward and would likely include things such as electromagnetic or cyber suppression of an adversary’s radar systems for information soft-kills or deliberate limited air strikes for warning-style aerial firepower assaults.

Figure 6. PLA Air Force high-intensity weishe activities

Source: courtesy of the author, adapted by MCUP.

PLAAF activities, like other domains and subcategories, can once again be arranged along a spectrum and ramped up as the situation develops or used independently at any stage of the conflict as the situation requires. As previously mentioned, although it is expected that different services under conventional weishe would have their own set of activities, the research up to this point has only revealed the fleshed-out PLA Air Force and PLA Rocket Force subcategories within conventional military weishe. The research indicates that there is at least a discussion of a theory of using weishe activities specific to the PLA Army and the PLA Navy.[82] However, a detailed breakdown of these activities for the two services was not found in the research.

Space Weishe (空间威慑)

Space weishe occupies a unique position within the overall system insofar as it is understood that space is a strategic high ground that may have certain restrictions whether technological, economic, legal, or otherwise. Space-based capabilities require significant technological and economic investments to build and have national-level significance. Because of this, militaries have basically adapted“‘joint military-

civilian use that combines peace and war’ model(s) of construction.”[83] Therefore, space-based assets that have military value may be either civilian or military-owned and most likely dual-use. Furthermore, “although the main body in space operations strengths is military space strengths, still, large numbers of civilian space strengths inevitably will be requisitioned in wartime, thus forming an integrated military-civilian system of operational strengths.”[84] In practice, it may be difficult to differentiate between those space-based assets that are military or civilian and may become targets for military or political objectives. This means that within China’s application of space weishe, it is possible that activities may be carried out against an adversary’s civilian assets with the expectation that those targeted assets would play a role in a military conflict. For satellite constellations such as Starlink, on which Chinese authors have written on its civilian and military applications, the constellation is likely to be the target of Chinese space weishe activities.[85] Due to the blending of civilian and military custody and application, and their significant effects on different levers of comprehensive national power, space-based activities are considered to be an increasingly important domain. Furthermore, “since space (weishe) in terms of use has a strategic quality, convenience, and controllability, it thus will become the main form of military weishe, and the frequency of its use will grow increasingly frequent.”[86]

Despite the growing importance of space weishe, in Lectures on the Science of Space Operations, the author highlights the risk of inadvertent escalation during space weishe activities.[87] This causes a need to appropriately adapt the measures of space weishe to achieve political objectives but not cause undue escalation or compromise of China’s space-based assets. For this reason, the overall situation

[全局] is incredibly important for “if these situations are not well grasped, it could lead to failure of the weishe and then set off a war or an escalation of the war.”[88] In this vein and as previously mentioned, “in order to enhance the weishe effects, space weishe when applied usually adopts the method of gradual escalation, to constantly increase the degree of force in weishe of the enemy.”[89] Due to the sensitivity of space activities, there is also a risk of overdoing space weishe. Accordingly, while gradual escalation is the primary method of raising the cost to the adversary, there is also gradual de-escalation if it is perceived that the current activities are too escalatory.[90] The objective of having this flexibility in space is to create a situation in which “the intensity of weishe must be moderate the key points will be leaving the adversary leeway to come to terms and make concessions, and to prevent an escalation of the confrontation cause by the adversary not having an out.”[91] At the highest end of space weishe activities, the ultimate goal is to “force them to dare not adopt large-scale military activities, or force them to sign a ‘[peace] treaty made under weishe’.”[92]

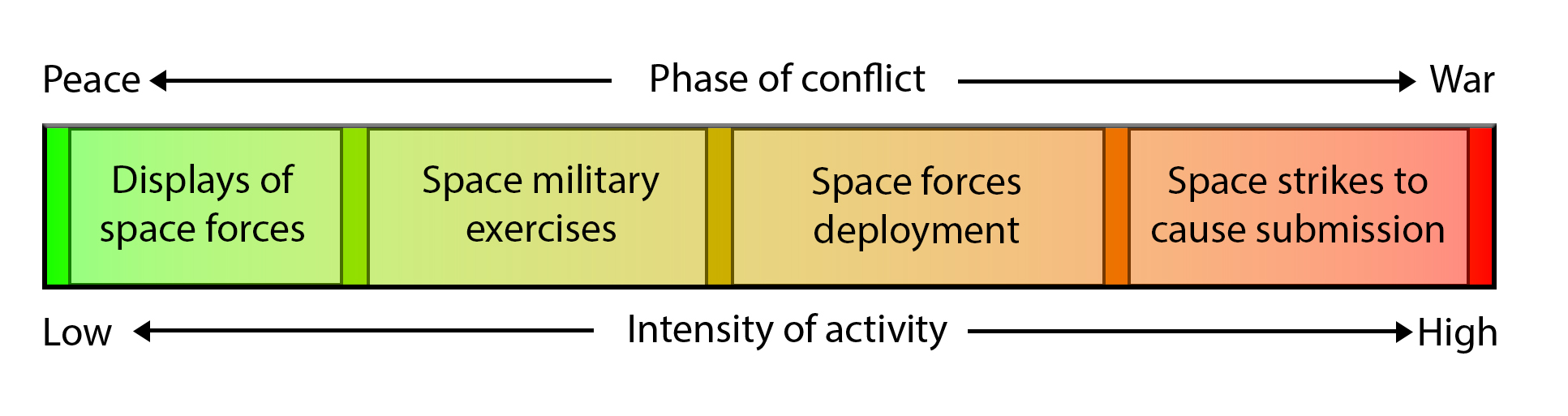

The primary space weishe activities as enumerated by Lectures on the Science of Space Operations are grouped into four categories: displays of space forces [展示空间力量], space military exercises [空间军事演习], space forces deployment [空间力量部署], and space strikes to cause submission [慑服空间打击] (figure 7).[93] Of note, displays of space forces usually entails exploitation of the media to create propaganda and display strength in support of integrated weishe efforts such as diplomatic and economic weishe.[94] Space military exercises also include exercises within the space domain as well as space-based capabilities such as intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance in support of military exercises in other domains.[95] The most famous examples of space military exercises may be the 2007 Chinese antisatellite weapon test or the test of the robotic arm on Chinese satellites to remove space debris.[96] Both of these activities may be called medium-low intensity space weishe activities. Space forces deployment includes the launch, recovery and on-orbit maneuver, as well as maneuver in other domains to support the rapid reconstitution or build-up of the spaced-based battle network.[97] Space strikes to cause submission are described as limited strikes against an adversary and can take the form of “soft” or nonkinetic and potentially reversible attacks and “hard” kinetic strikes on the adversary’s space systems. Of note, the primary targets of both soft and hard kill strikes are critical nodes or space-based assets that are vital to the command-and-control systems of China’s adversary.[98] Military and civilian information networks are also a key target for soft-kill strikes.[99] Deliberately targeting these nodes may enhance the psychological impact of the space strike, therefore increasing its value in strategic weishe.

Figure 7. Space weishe activities

Source: courtesy of the author, adapted by MCUP.

As noted by Kevin Pollpeter in his article Coercive Space Activities: The View from PRC Sources, a deeper analysis of Lectures on the Science of Space Operations and other sources indicates that there may be additional space weishe activities or concepts in development. These include four additional space weishe activities or sets of activities: enhancement of conventional force capabilities, deterrence by denial, deterrence by punishment, and deterrence by detection.[100] Although the term deterrence is used in Pollpeter’s description of these types of activities, he notes that it is in reference to the broader concept of weishe.[101] Furthermore, these four additional types of weishe appear to be more potential effects or results of traditional weishe activities and are brought to light in analysis of Chinese authors looking at Western weishe applications. What is clear from the analysis is that space weishe is growing in terms of the theoretical application of space weishe activities in strategic weishe.

Information Weishe (信息威慑)

The information weishe domain is less well described conceptually in the researched PLA texts, but this may be a function of the expanding definitions of what falls under this domain. In the 2013 iteration of The Science of Military Strategy, information weishe was described as network weishe, and notably it mentions that “there is nonetheless very great diversity in the various understanding of network [weishe], and both the theory and practice of network weishe await further development and perfection.”[102] Based on the evolution of the information domain, other authors have included different types of weishe that may fall into this domain to include cyber, electromagnetic spectrum, and “intelligent” weishe.[103] As the definition of the information weishe domain evolves, the 2020 Science of Military Strategy may have settled on information weishe as a catch-all term for military weishe activities that effect the information domain. According to the 2020 Science of Military Strategy, information weishe “is reliant on information science and information technology’s strong functions, and is a weishe carried out with the momentum and power of information warfare.”[104] The types of activities that encompass information weishe include but are not limited to unauthorized access and query, malicious software, destruction of databases, obtaining electronic intelligence, electronic attacks, and others.[105]

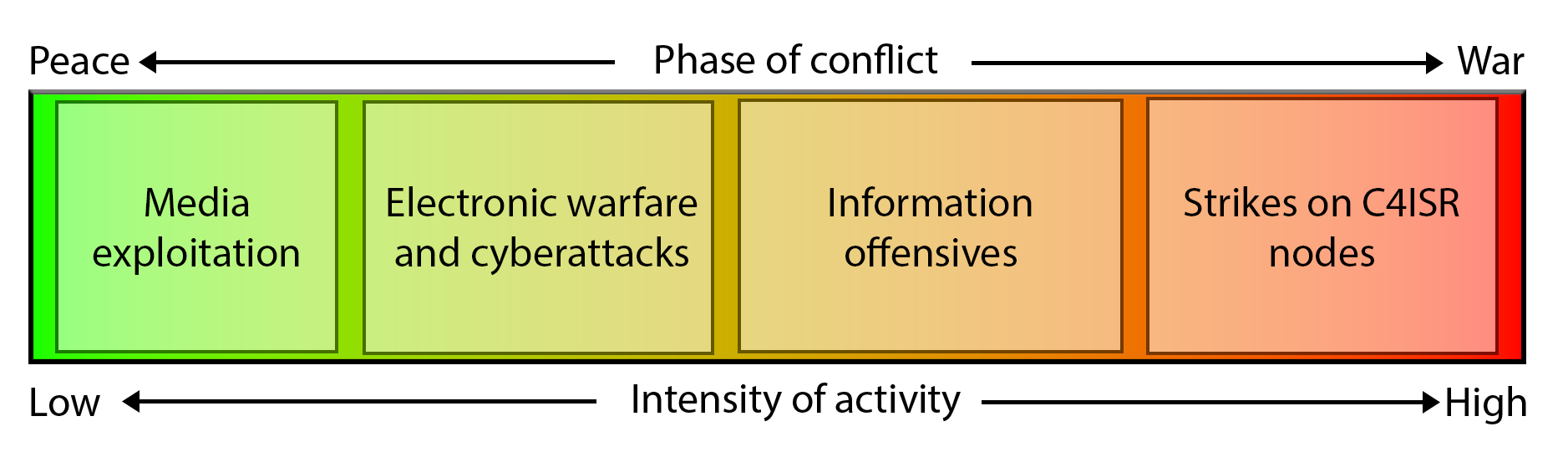

Although a bit older, the 2009 Lectures on Joint Campaign Information Operations provides some detail into what concrete information weishe activities may look like across a spectrum of intensity. The text offers two sets of information weishe activities; the first set is broad and includes electronic feigning, electronic jamming, network attacks, psychological spoofing (deception), antichemical destruction, and precision attacks.[106] These activities are recommended to accompany other campaign-level weishe operations to “create a formidable information attack momentum and form a psychological perspective.”[107] The second set of information weishe activities is broken into four intensity groupings. The first group has media exploitations to highlight military strength, misinformation and disinformation about operational strength, and publicizing preparations of information attacks.[108] The second group includes electronic feigning, disguising, and jamming on the adversary’s information systems, as well as their network spoofing and virus attacks.[109] The Volt Typhoon infiltration and dwell on U.S. critical infrastructure systems may be considered a medium-low intensity information weishe activity.[110] The third group of information weishe activities includes using virtual reality (cyberspace) to create an information offensive and supplementing military feigning activities.[111] And the fourth group focuses on the use antiradiation-guided missiles, antiradiation unmanned aircraft, and others to carry out “eye-gouging military tactics” on the adversary’s command information systems as well as kinetic strikes on the adversary’s command, control, communication, computers, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (C4ISR) nodes.[112] On the whole, these different activities can be described as media exploitation, electronic warfare and cyberattacks, information offensives, and strikes on C4ISR nodes (figure 8). While a simplified spectrum of information weishe activities is referenced here, it could be expanded to incorporate each escalatory step within each category.

Figure 8. Information weishe activities

Source: courtesy of the author, adapted by MCUP.

People’s War Weishe (人民战争威慑)

People’s War weishe is considered a unique and bedrock capability of China. Despite this, there are few concrete details on how to carry out People’s War weishe or more broadly a People’s War in the modern context. As a component of military thinking, People’s War stems from the early phase of weishe and Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping thinking on how to stop an adversary from invading China through the threat of facing the Chinese masses. Fundamentally, People’s War weishe relies on the notion that “all people are soldiers” and that any would be adversaries face not just the PLA but China as a whole.[113] People’s War and the corresponding weishe activities are important for the idea of strengthening national will to fight in the face of an adversary as well as mobilization of national resources. Chen Dongheng, a senior lecturer and researcher within the Military Political Work Research Institute of the PLA Academy of Military Sciences in 2023 defined People’s War as, “mobilizing the broadest masses of the people, forming the broadest united front, and gathering all resources and forces to unite against the enemy are the essence of the strategies and tactics of the People’s War.”[114] Yuan Zhengling, an assistant researcher in the Strategic Department of the Academy of Military Sciences, described core thinking on People’s War weishe as:

Build a People’s army that is complete and high quality to serve as the backbone strength of waging war and implementing weishe; maintain the “three-in-one” system of the armed forces, which should see the people’s militia building elevated to a strategic position, and improve its ability to mobilize quickly; explore the tactics of people’s war under high-tech conditions; construct an extensive, unified front, and integrates multiple efforts in various domains and forms; and sustain the basic policy of protracted war, etc. It can be seen that People’s War weishe is the multi-layered overall strength weishe that organically combines actual strength and potential strength and tangible and intangible forces. It possesses the special characteristics of all of the people (全民性), comprehensiveness, and sustainability. (People’s War weishe) has many important differences from the thinking of implementing weishe that solely relies on some advantage of armed force.[115]

From the description of People’s War weishe, it is quite clear that this specific domain is multifaceted and complex. At its foundation, it involves some aspect of mobilizing civilian nonmilitary and military capabilities to enhance strategic weishe. Although there are no explicit discussions in PLA sources on how this mobilization may occur short of war, Dean Cheng’s analysis of population-wide participation (全民参与, quanmin canyu) in mobilization may offer some insight into how this could work for People’s War weishe. Cheng points out that population-wide participation in mobilization includes two key aspects. The first aspect focuses on “actively integrat(ing) the broad civilian populace and associated resources into the planning and implementation of mobilization process.”[116] Cheng assesses that “national defense mobilization work includes not only military forces, but also political, economic, [science and technology] S&T, education, culture, health, and many other resources.”[117] With mobilization, there is a formal bureaucratic process necessary, and the decision for mobilization carries the risk of strongly impacting the nation. For this reason, the decision to mobilize the nation requires senior national-level leaders.[118] Once mobilization does occur, there are concrete measures to gradually increase the scale and intensity of mobilization. In this sense, it seems that there is an intensity spectrum for People’s War weishe that includes a break point between activities taken in relative peacetime and those take after mobilization has occurred. To understand how People’s War weishe may be implemented, it is possible to separate the associated activities into indirect and direct activities. Indirect activities are those which may take place before mobilization and are meant to enhance the conventional military weishe capability of the PLA. In contrast, direct People’s War weishe activities are those that would be undertaken after mobilization of the nation and would involve organizations and processes that are created in the act of mobilization.

Indirect ways in which People’s War weishe may be implemented include the continuation and leveraging of military-civil fusion.[119] In practice, military-civil fusion would see a higher integration of civilian capabilities into combat capability. This could be in the form of increased civilian logistical support in extreme and hard-to-reach locations, a closer integration of civilian technological research and development into the PLA equipment supply chain, or other methods. To some extent, integration of civilian logistical support into the PLA is currently underway with large-scale logistics exercises and the signing of contracts for logistical support between provincial governments and the PLA.[120] Other examples include the government program to requisition civilian shipping through the maritime militia for contingencies such as a cross-strait invasion.[121] In terms of an increased presence in the research and development of PLA weapon systems, there are numerous examples across different industries. Most notably, China’s civilian space companies are known to be a critical player in the PLA’s space-based capabilities.[122] Beyond these indirect applications of People’s War weishe, there may also be direct applications and operations that support People’s War weishe along the intensity of activity spectrum.

Direct applications of People’s War weishe likely involve the integration of militia and the civilian air defense and civilian organizations into military weishe activities around the time of or after mobilization. Within the “three-in-one” system that Yuan Zhengling refers to in his description of People’s War weishe, the three organizations that comprise the one armed forces are the People’s Liberation Army, the People’s Armed Police force, and the Militia of China (中国民兵). According to a special report from the Standing Committee of Yongzhou Municipal People’s Congress:

The Chinese militia is a mass armed organization led by the Communist Party of China, an important component of the armed forces of the People’s Republic of China, a reserve force of the People’s Liberation Army of China, an important force for consolidating grassroots political power, maintaining national security and social stability, and the basis for conducting People’s War under modern conditions.[123]

Presumably, the militia acts as a link between the citizenry and the military and is an important part of mobilization of the population. Included within the Chinese militia is the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM). Therefore, military weishe activities undertaken by the PAFMM may well be included within the scope of People’s War weishe activities. Just because the militia may make up the backbone of People’s War weishe does not immediately mean that there is coordination between the PLA and militia to implement weishe. A closer look at the civilian and militia mobilization structure can provide that potential link. Militia and civilian mobilization appear to be tied together and fall under a series of National Defense Mobilization Committees (NDMC).[124] At the highest level of these committees is the national-level NDMC. This committee is “headed by the premier of the State Council, while its vice chairmen are the vice premier of the State Council and one of the vice chairmen of the CMC (Central Military Commission).”[125] The combined military-civilian leadership of the highest-level NDMC may provide more military oversight and closer integration of militia and civilian mobilization into the application of People’s War weishe across the spectrum of conflict.

In terms of direct People’s War weishe activities, one interpretation of these may be represented by the set of activities called “creating an atmosphere of war [营造战争气氛].” This set of activities is defined by the 2020 Science of Military Strategy as party, country, and military leaders publicly issue statements of resolution of willingness to go to war [党戴国家和军队领导人发表声明,宣示不惜一战的决心]; the National People’s Congress issues war mobilization orders at the appropriate time [全国人大适时发布战争动员令]; announcement of theater regions entering a wartime state [宣布局部地区进人战时状态]; troops unfold and enter prebattle preparations [部队展开,进行临战准备]; carry out public opinion, psychological, and legal warfare [展舆论战戴心理战戴法律战]; organize theater emergency mobilization, civil air defense, transportation infrastructure protection and defensive combat exercises [组织局部应急动员戴人民防空戴保交护路利防卫作战演练]; organize front-line evacuations of the public [组织一线群众疏散]; and issue public announcements urging the relevant countries to evacuate their nationals and government officials [发布公告,敦促有关国家撤走侨民和办事机构人员] (figures 9 and 10).[126] While these activities are not directly attributed to People’s War weishe, the effect of the actions is mass mobilization of the Chinese citizenry and establishing a wartime posture. They also seem to reflect some sort of escalation matrix across the activities, beginning with statements of resolution and ending with full wartime mobilization and readiness.

Figure 9. Potential low-medium intensity people’s war weishe activities

Source: courtesy of the author, adapted by MCUP.

Figure 10. Potential medium-high intensity People’s War weishe activities

Source: courtesy of the author, adapted by MCUP.

People’s War weishe does have some restrictions. According to the 2020 Science of Military Strategy, People’s War weishe can only be implemented “if the (fight of) the People’s Army is in line to a high extent with the interests of the people.”[127] This implies that there must be a concerted effort and political work to get national buy-in from the people toward a strategic objective. According to theory, People’s War represents “the basic interests of the broad masses of the people, and it possesses the political basis for implementing mobilization of the entire people, and participation in the war by the people, which to the maximum extent can give play to the warfighting potential of the people and nation.”[128] Mobilization of civilian potential in line with and supporting the military is the key to People’s War weishe. Even though there appears to be some direct and indirect applications of People’s War weishe to aid in an integrated weishe capability, methods for modernizing people’s war weishe appear to still be under development.[129]

The System of Strategic Weishe (战略威慑体系) and Integrated Weishe (整体威慑)

At the highest level, “a strategic system is an organizational structure composed of strategies at different levels.”[130] From looking at the individual strategic weishe domains and their different activities, we can begin to understand how China envisions building its system of strategic weishe. Essentially, the system of strategic weishe and integrated weishe are one in the same. In this context, the term used for integrated, zhengti (整体), refers to the overall system of weishe and is simply a different way to express an integrated whole. The envisioned system of strategic weishe is meant to better coordinate and integrate multiple domains of strategic weishe to provide the CCP with a more comprehensive application of strategic weishe against its adversaries.

According to Yuan Zhengling, “Weishe is quasi-war (准战争), and it requires taking advantage of the comprehensive use of each aspect and the various methods, it is very difficult to achieve a good outcome by solely relying on the military method.”[131] Ironically, it appears that strategic weishe military activities are possibly the most mature aspect of applying strategic weishe. As previously discussed, the nonmilitary aspects of strategic weishe are, as of now, envisioned as primarily used in “peacetime” to set conditions for the application of military weishe or used in between peace and war to enhance military weishe activities.[132] In the future, it is highly likely that the nonmilitary aspects of integrated weishe will grow in importance and application. To this effect, in Lectures on the Science of Space Operations, Jiang Lianju argues that space weishe can only be effective when paired with other forms of weishe and the different levers of comprehensive national power.

Under informationized conditions, the diversity and complexity of threats and conflicts have decided that military weishe by a single means or a single avenue will have increasing difficulty in forming effective weishe of the enemy. Only when space weishe is combined with weishe forms such as nuclear weishe and conventional forces weishe, and at the same time complemented by struggle in the political, economic, and diplomatic fields, so that all forms of weishe benefit by mutual association, can the effectiveness of weishe be brought into play to the maximum extent.[133]

However, harnessing and coordinating multidomain strategic weishe capabilities, especially nonmilitary capabilities is unquestionably very difficult. One effort to integrate military and nonmilitary strategic weishe into a coordinated system may be the building out of China’s Integrated National Strategic System and Capabilities (INSS&C). According to the 2024 Department of Defense report Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China, the INSS&C aims to synchronize top-level planning organizations within China’s governance system to better leverage China’s comprehensive national power.[134] It would logically follow that integrated weishe and its supporting capabilities would fall within the scope of the INSS&C’s responsibilities. The INSS&C as a component of military-civil fusion, which is an aspect of People’s War weishe, further strengthens this connection. Moreover, the planning and implementation of weishe activities at an integrated whole-of-comprehensive-national-power level would require a mechanism such as the INSS&C to execute.

When conceptualizing how China’s integrated weishe or system of strategic weishe works, the intensity spectrums of each domain can help to visualize the system. Each domain and its military weishe activities spectrum act as one lever from which the CCP can ratchet up or down as necessary to achieve their political objective. When individual domains are combined, and in line with PLA systems thinking, “the adjusting-coordination among every subsystem directly decides the functions of the entire system, so the subsystems can realize an integrated-whole effect [整体效应] of 1 + 1 > 2.”[135] In plain language, this means that each strategic weishe domain is equivalent to a subsystem and coordination between the different domains increases the overall (整体) effect of strategic weishe. In the case of the system of strategic weishe, depending on the adversary, China may ramp up one or more of the activities within each weishe domain to attempt to drive the opponent into negotiations or to accede to their demands. As such, “strategic weishe is aimed at the opponent’s psychology, cognition and decision-making system. Its functioning mechanism is to make the adversary recognize, as they weigh the pros and cons, that taking action will incur severe costs, (costs that) will be unacceptable and surpass any benefit gained. When the adversary’s perceived costs and losses are increasingly large, the produced weishe effect on its psychology, cognition, and decision making are increasingly large, and weishe becomes increasingly effective.”[136] In effect, by building and using a system of strategic weishe, the CCP and PLA hope to have different levers of pressure across multiple domains to increase or decrease until they achieve their desired psychological effect; the submission of their adversary.

Conclusion

China’s views of strategic weishe continue to evolve, however, this research aims to provide a common framework for analyzing and understanding China’s actions when it attempts to deter, compel, or coerce its adversaries. By understanding the fundamental concept of strategic weishe, we can build a clearer picture of how China sees employing military weishe activities and their desired effects. After evaluating Chinese texts on military strategy and operations in different domains, the methodology for pursuing strategic weishe is quite consistent. Considering this level of consistency and given it is across a near 20-year period, it is likely that future thinking on strategic weishe will at least follow a similar pattern. Even as technology evolves and newer domains for strategic weishe become solidified, they are likely to consist of a set of military weishe activities that follows an intensity spectrum and that can be applied across the spectrum of conflict. Furthermore, the accompanying military weishe activities within these domains are likely to resemble, in some way, the standard set of military weishe activities that begins with a display of the capability and ending with nonkinetic or kinetic strikes. Understanding this framework can be helpful to create a guide for unpacking Chinese thinking on new and emerging weishe capabilities such as “intelligent” or biological weishe.[137]

Further studies on domain-specific military weishe activities as newer PLA texts become available would help to better flesh out specific anticipated PLA weishe activities across a broader swatch of conventional capabilities. Additionally, applying the framework explored in this article to modern case studies can help analysts, academics, and policymakers better assess and understand the ways and means that the PLA is used for political objectives. This may also include assisting in identifying indications and warnings for if the CCP and PLA may escalate a situation into armed conflict. If activities within one or more of the weishe domains have escalated to the point of threatening or carrying out limited nonkinetic strikes against their opponent, the next rung of escalation would then likely be nonkinetic or kinetic strikes and positioning the PLA for stepping off into war. Tracking the strategic weishe intensity level of PLA activities in different domains may provide some insight into which part of the conflict spectrum the CCP and PLA perceive themselves to be at.

Perhaps the most important thing to take away from understanding the Chinese concept of strategic weishe is to build an understanding on Chinese escalation thinking. By thoroughly understanding the escalation matrix that the Chinese see in strategic weishe, it can better help the United States and its allies and partners interpret and respond to PLA and CCP military weishe activities. Rather than assigning the term gray zone to these activities, we can, with specificity, describe the different military weishe activities that we observe and tailor our responses for our own political objectives. This can theoretically give us an advantage in escalation control as we will better understand the paradigm in which the CCP and PLA operate.

Endnotes

[1] Original Chinese: 实现建军一百年奋斗目标,开创国防和军队现代化新局面; Xi Jinping, “Xi Jinping: Hold high the great banner of socialism with Chinese characteristics and work together to build a modern socialist country in an all-around wayㄚReport to the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China” [习近平:高举中国特色社会主义伟大旗帜 为全面建设社会主义现代化国家而团结奋斗——在中国共产党第二十次全国代表大会上的报告] (speech, 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, Beijing, 16 October 2022).

[2] Original Chinese: [打造强大战略威慑力量体系,增加新域新质作战力量比重,加快无人智能作战力量发展,统筹网络信息体系建设运用.]; Xi Jinping, “Xi Jinping: Hold high the great banner of socialism with Chinese characteristics and work together to build a modern socialist country in an all-around wayㄚReport to the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China.”

[3] The primary PLA texts used in this analysis are the 2013 and 2020 editions from the In Their Own Words Series: The Science of Military Strategy, 2020 (Montgomery, AL: China Aerospace Studies Institute, Air University, 2020); Services and Arms Application in Joint Operations (Montgomery, AL: China Aerospace Studies Institute, Air University, 2020); Lectures on the Science of Space Operations (Montgomery, AL: China Aerospace Studies Institute, Air University, 2013); and Lectures on Joint Campaign Information Operations (Montgomery, AL: China Aerospace Studies Institute, Air University, 2009). These texts are available in English from the China Aerospace Studies Institute. When available, the Chinese version of the texts was used with the author’s translation and interpretation. When there are complex terms or sentences critical to the analysis and the original Chinese is available, the English and Chinese are offered. In certain cases, when only the English text is available and the term deterrence is used, it has been changed to weishe to reflect the original term used: weishe (威慑). While it is possible that a term other than weishe was used in some of these sources, it is highly improbable given the consistency between the Chinese use of the term weishe and its translation into English texts (both by machine and human translation methods) into deterrence.

[4] Xiao Tianliang, ed., The Science of Military Strategy, 2020 (Beijing: National Defense University Press, 2020), 28.

[5] Xiao, The Science of Military Strategy, 2020, 26.

[6] Michael S. Chase and Arthur Chan, China’s Evolving Approach to “Integrated Strategic Deterrence” (Santa Monica, CA: Rand, 2016), 3ㄚ4, https://doi.org/10.7249/RR1366.

[7] The original text states: [战略威慑有两种基本作用,一种是通过威慑遏止对方不要干什么,另一种是通过威慑胁迫对方必须干什么,二者实质都是使对方屈服于威慑者的意志带] in Xiao, The Science of Military Strategy, 2020, 131.

[8] There is a plethora of terms that the Chinese use to describe different actions that may contain elements of deterrence, compellence and coercion. For example, terms such as 威迫 (weipo) or 胁迫 (xiepo) may both be used to describe compellence, whereas weishe is most often used to describe deterrence. It appears rather clear from research that the term weishe, while most often being used to refer to deterrence, in fact refers to a larger and more abstract concept that includes all three of the English concepts of deterrence, compellence, and coercion. The difference in the interpretation of weishe lies in the circumstances under which weishe is used. For example, in lower-intensity activities, weishe may be appropriately interpreted as deterrence, whereas in higher intensity applications of weishe it may more accurately be interpreted as compellence or coercion. For more on this, see Kevin Pollpeter, Coercive Space Activities: The View from PRC Sources (Maxwell, AL: China Aerospace Studies Institute, Air University, 2024), 4.

[9] For the remainder of the discussion, the pinyin for the term 威慑 (weishe) will be used, but its meaning includes aspects of deterrence, compellence, and coercion.

[10] Xiao, The Science of Military Strategy, 2020, 135; Yuan Zhengling, “On the Thought and Practice Conventional Weishe after the Founding of New China” [论新中国建立后常规威慑思想与实践], in Military History [军事历史], Remembering 75 Years of Army Building in the PLA, vol. 1 (Beijing: China National Knowledge Infrastructure, 2002), 26; and “On the Thought and Practice Conventional Weishe after the Founding of New China,” 26.

[11] Xiao, The Science of Military Strategy, 2020, 127.

[12] Yuan, “On the Thought and Practice Conventional Weishe after the Founding of New China,” 26.

[13] Henry A. Kissinger, “Memorandum for the President,” Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976, vol. E-13, Documents on China, 1969–1972 (Washington, DC: Office of the Historian, Department of State, 1972).

[14] Yuan, “On the Thought and Practice Conventional Weishe after the Founding of New China,” 26.

[15] The author has chosen to translate 整体威慑 (zhengti weishe) as integrated weishe. Although the direct translation may be most appropriate as “overall weishe,” in Chinese, 整体威慑 is most often used to describe to comprehensive and coordinated implementation of various types and domains of weishe for an effect. When the American concept of integrated deterrence is discussed in Chinese the terms 综合威慑 and 一体化威慑 are generally used; however, they do not appear to be used to describe the Chinese concept of integrated weishe. See Xu Sanfei and Wu Siliang, “An Analysis of the Development Trend of Foreign Military Strategic Deterrence Theory and Practice,” People’s Liberation Army Daily, 30 January 2024.

[16] The Chinese name is used in the text and English name is given in parentheses for the various wars/conflicts on China’s periphery. See Shou Xiaosong, ed., The Science of Military Strategy, 2013, trans. China Aerospace Studies Institute (Maxwell, AL: China Aerospace Studies Institute, Air University, 2021), 175.

[17] Shou, The Science of Military Strategy, 2013, 176.

[18] Yuan, “On the Thought and Practice Conventional Weishe after the Founding of New China,” 22.

[19] Shou, The Science of Military Strategy, 2013, 177.

[20] Yuan, “On the Thought and Practice Conventional Weishe after the Founding of New China,” 23.

[21] Shou, The Science of Military Strategy, 2013, 177.

[22] Shou, The Science of Military Strategy, 2013, 177.

[23] Shou, The Science of Military Strategy, 2013, 178.

[24] Shou, The Science of Military Strategy, 2013, 178.

[25] Shou, The Science of Military Strategy, 2013, 180.

[26] Shou, The Science of Military Strategy, 2013, 180.

[27] Xiao, The Science of Military Strategy, 2020, 128.

[28] Xiao, The Science of Military Strategy, 2020, 127.

[29] Xiao, The Science of Military Strategy, 2020, 131.

[30] Xiao, The Science of Military Strategy, 2020, 127, 131.