China Military Studies Review

Adapting to Future Wars

The Reorganization of the PLA Army’s Special Operations Forces and the Move Toward Professionalization

Joshua Arostegui

25 September 2025

https://doi.org/10.33411/cmsr2025.01.003

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) implemented major changes to the organization, accession, and training of its army’s special operations forces (SOF) beginning in 2017, including the creation of a 12-man SOF team and establishment of a probable national-level army-subordinate counterterrorism unit. Beginning in 2025, the PLA introduced several changes to improve officer accession and noncommissioned officer retention in its special operations community. This article assesses observed changes since 2017 designed to improve the PLA’s command and control of its army’s SOF units and to set the foundation for China’s elite forces becoming world-class by 2049.

Keywords: People’s Liberation Army, PLA, PLA Army, PLAA, special operations forces, SOF

Following the completion of a highly publicized China-Serbia joint special operations training event in late July 2025, Belgrade claimed the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) forces that participated “showed an exceptional level of organization and professionalism.” Although many of the highlights surrounding Peace Guardian 2025, which took place in Hebei Province, China, emphasized both sides’ use of Chinese equipment, including firearms and unmanned ground and air systems, Beijing could not have asked for a better compliment.[1]

While Serbia’s participating unit, the 72d Special Operations Brigade, is a well-trained and equipped combat force, the PLA Army’s (PLAA) special operations units are typically reported as inexperienced and inadequately trained for optimal integration with conventional military forces.[2] Yet, the compliment from Serbia’s Ministry of National Defense reflects eight years of quiet transformation within China’s special operations forces (SOF). Driven by decades of engagement with foreign militaries and observation of conflicts where special operations units have played outsized roles on the battlefield, the PLA has not only changed the organization of its army’s special operations teams to use a more Western style, but it also adopted innovative programs to retain more professional operators and leaders within its elite units.[3]

This article is intended to inform readers of how China is modernizing and professionalizing the army’s special operations forces in preparation for future wars. This work also includes new findings about the creation of a 12-man SOF team construct, the establishment of a probable national-level army counterterrorism force, and major adjustments to how special operations officers and recruits are canvassed and trained. However, this work does not detail PLA special operations tactics, how SOF units will carry out missions in certain campaigns, and known special operations leaders.

The PRC’s special operations community includes more than just the army. The PLA Air Force Airborne Corps (PLAAFAC), PLA Navy Marine Corps (PLANMC), PLA Rocket Force (PLARF), and People’s Armed Police (PAP) all have special operations units. However, the army’s SOF brigades make up roughly 80 percent of the total special operations units in the force, and the army controls the PLA’s primary special operations training organizations. Although this article is designed to assess the PLAA’s new changes, it will include references to those other services if they experienced similar adjustments.

Table 1. People’s Liberation Army special operations missions

|

Mission

|

Objective

|

|

Special reconnaissance

|

Infiltrate to track and monitor key targets

|

|

Long-range strike guid- ance

|

Locate targets and transmit targeting data to joint fire units and/or execute battle damage assessments

|

|

Sabotage operations

|

Sabotage high-priority military targets, civilian infrastructure, and other strategic or operational targets

|

|

Key point seizure

|

Seize objectives when the action can significantly impact operational success

|

|

Rescue/retrieve key per- sonnel and equipment

|

Rescue personnel in peacetime or wartime like downed pilots and retrieve vital equipment like classified documents

|

|

Harassing operations

|

Cause chaos in the enemy’s rear using hard or soft attacks to divert forces or attrit, exhaust, deceive, and confuse the enemy

|

|

Search and suppress missions

|

Capture enemy political or military leaders to cause chaos, lower morale, and obtain information; hunt and eliminate terrorist leaders and enemy remnants in retreat

|

|

Network sabotage

|

Conduct network interference through network intrusion, jamming, network destruction, and other means

|

|

Psychological attacks

|

Support psychological warfare plans to cause chaos and lower enemy morale

|

|

Antiterrorism

|

External hostage rescue, assaults on terrorist groups and base camps, securing weapons of mass destruction and infrastructure during internal unrest and terrorist incidents; special security for high-level officials and important events

|

Source: Kevin McCauley, “PLA Special Operations: Combat Missions and Operations Abroad,” China Brief 15, no. 17 (3 September 2015), adapted by MCUP.

China’s Special Operations Forces: A Brief Overview

Although special operations units within the People’s Liberation Army look much different than they did in 2015, their primary roles and functions on the battlefield remain relatively unchanged. As the Chinese military’s units designed to execute key strategic and operational combat missions, in addition to military operations other than war, special operations forces are considered a force multiplier.[4]

With roots found in the army’s earlier reconnaissance units, PLA special operations units were established in the 1980s and 1990s to carry out a host of missions that could create favorable conditions for main force units and disrupt enemy operational activities. However, the PLA does not prepare its units to conduct all U.S. Title 10 special operations core activities, including unconventional warfare and foreign internal defense.[5]

The People’s Liberation Army has always intended to use its army’s elite forces to carry out reconnaissance, raids, and key point seizure against traditional military targets like command posts, ports, airfields, missile launch sites, supply depots, transportation nodes, etc. As a result of Chinese media frequently broadcasting special operations units conducting direct action missions, many Western media outlets have regularly referred to them as having more in common with U.S. Army Rangers than Special Forces.[6] However, unlike Rangers, Chinese special operations units, normally companies, were assigned as enablers to army divisions and brigades to support conventional force campaigns. In China’s older writings on major campaigns, especially those focused on a joint island landing campaign against Taiwan, special operations units would carry out those missions behind enemy lines to harass the adversary and enable freedom of maneuver for ground forces.[7]

The Need for Change: A Primer

In 2017, a PLAA senior colonel and lieutenant colonel assigned to the Southern Theater Command Joint Staff Department wrote an article for an early 2018 edition of China Military Science describing the weaknesses and requirements for change in all the PLA’s special operations forces. The authors assessed that to catch up with the capabilities of world-class special operations forces like those in the United States, Russia, and India, the PLA was undertaking a series of modernization and development efforts:

• Specialized research (特研) into Chinese and foreign special operations case studies to develop new concepts and training. Emphasis would be placed on SOF development trends for objectives and missions, force organization and structure, weapons and equipment deployment, organizational and command processes, and joint support.

• Specialized composition (特编) to improve command and control of special operations forces at strategic, campaign/operational, and tactical levels. Emphasis would be placed on improving command and deployment capabilities for global and regional special operations, increasing the number of noncommissioned officers (NCO) in SOF units, and enabling multidomain strikes and maneuver.

• Specialized selection (特选) of new special operations officers and soldiers to focus on improved competency standards based on political qualities, SOF skills, cultural background, language proficiency, physical and mental reflexes, coordination and communication skills, and other characteristics. Emphasis would be placed on creating an elimination process that mirrored foreign forces’ 50–80 percent attrition rates during training.

• Specialized fielding (特装) of advanced weapons, sensors, and intelligence fusion systems to support multidomain operations and analysis and speed up decision-making. Emphasis would be placed on systems that enhanced rapid mobility in any theater, long-range battlefield reconnaissance systems, and strike equipment.

• Specialized training (特训) to improve basic SOF skills, jointness, mission readiness, and the ability to address new special operations theories and technologies. Emphasis was placed on innovating the current training model for recruits and officers up to the battalion level, improving senior officer academic training, taking advantage of international exercises and training with other countries, and “normalizing” deployments to border areas and at sea.

• Specialized support (特保) to include establishing joint logistics support mechanisms, prepositioning of equipment and supplies, operational security of SOF personnel, and authorizing special incentives for special operations personnel. Emphasis would be placed on supporting soldiers’ families, improving demobilization of SOF recruits to improve job prospects, and strengthening the overall “brand” of PLA special operations forces.[8]

The two authors of the China Military Science article wrote their detailed analysis while the PLA was in the middle of a major restructure that started at the end of 2015 with “above-the-neck” strategic level reforms that changed the organization of the Central Military Commission (CMC), established five joint theater commands, established an army headquarters, and led to several other overhauls. In April 2017, “below-the-neck” reforms changed the face of the PLAA’s tactical formations, including the number and organization of the force’s SOF brigades.[9] While the two authors were probably not the architects of the special operations reforms that occurred during the restructure period, their critical analysis of China’s special operations community provides foundational understanding as to why Beijing implemented the reforms detailed below.

PLAA Special Operations Forces Organization: New Brigades, New Teams

Following the PLA’s 2017 reforms, new special operations brigades were established in each service, with the army expanding its special operations footprint to 15 brigades, and the navy’s marine corps and air force’s airborne corps both expanding their individual special operations units into full brigades. The newly established PLA Rocket Force kept its sole special operations regiment.[10]

The 2017 restructure did not lead to the creation of a U.S. Special Operations Command-style command and control system for China’s forces.[11] Instead, the brigades fell under the command of regional corps-level and above headquarters, demonstrating a continued expectation that special operations units were designed to support conventional forces and use air lift assets assigned to the same corps. In the army, 13 group armies (units that are roughly equivalent to a U.S. Army corps) and two military districts in western China were each assigned a brigade as part of their newly standardized organization.[12] The brigades assigned to the airborne corps and marine corps—strategic formations not directly assigned to China’s joint theater commands—were clearly designed to support the missions of their parent organizations rather than a national-level special operations headquarters.

Table 2. Current People’s Liberation Army special operations units

|

Higher headquarters

|

Unit

|

|

Eastern Theater Command Army

|

71st Group Army Special Operations Brigade

|

|

72d Group Army Special Operations Brigade

|

|

73d Group Army Special Operations Brigade

|

|

Southern Theater Command Army

|

74th Group Army Special Operations Brigade

|

|

75th Group Army Special Operations Brigade

|

|

Western Theater Command Army

|

76th Group Army Special Operations Brigade

|

|

77th Group Army Special Operations Brigade

|

|

Northern Theater Command Army

|

78th Group Army Special Operations Brigade

|

|

79th Group Army Special Operations Brigade

|

|

80th Group Army Special Operations Brigade

|

|

Central Theater Command Army

|

81st Group Army Special Operations Brigade

|

|

82d Group Army Special Operations Brigade

|

|

*Former 83d Group Army Special Operations Brigade (now likely part of marine corps)

|

|

Xinjiang Military District

|

84th Special Operations Brigade

|

|

Tibet Military District

|

85th Special Operations Brigade

|

|

Air Force Airborne Corps

|

Special Operations Brigade

|

|

Navy Marine Corps

|

Special Operations Brigade

|

|

Rocket Force

|

Special Operations Regiment

|

Source: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China, 2024: Annual Report to Congress (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 2024), 81, adapted by MCUP.

In the case of the army, there was no apparent need to grow manpower within their special operations brigades, which each included around 2,500 personnel.[13] Newly established brigades were created from existing infantry brigades, ensuring adequate but untrained manpower.[14] While the size of the brigades remained unchanged, their organization was adjusted to adhere to China’s new corps-brigade-battalion modular construct.[15]

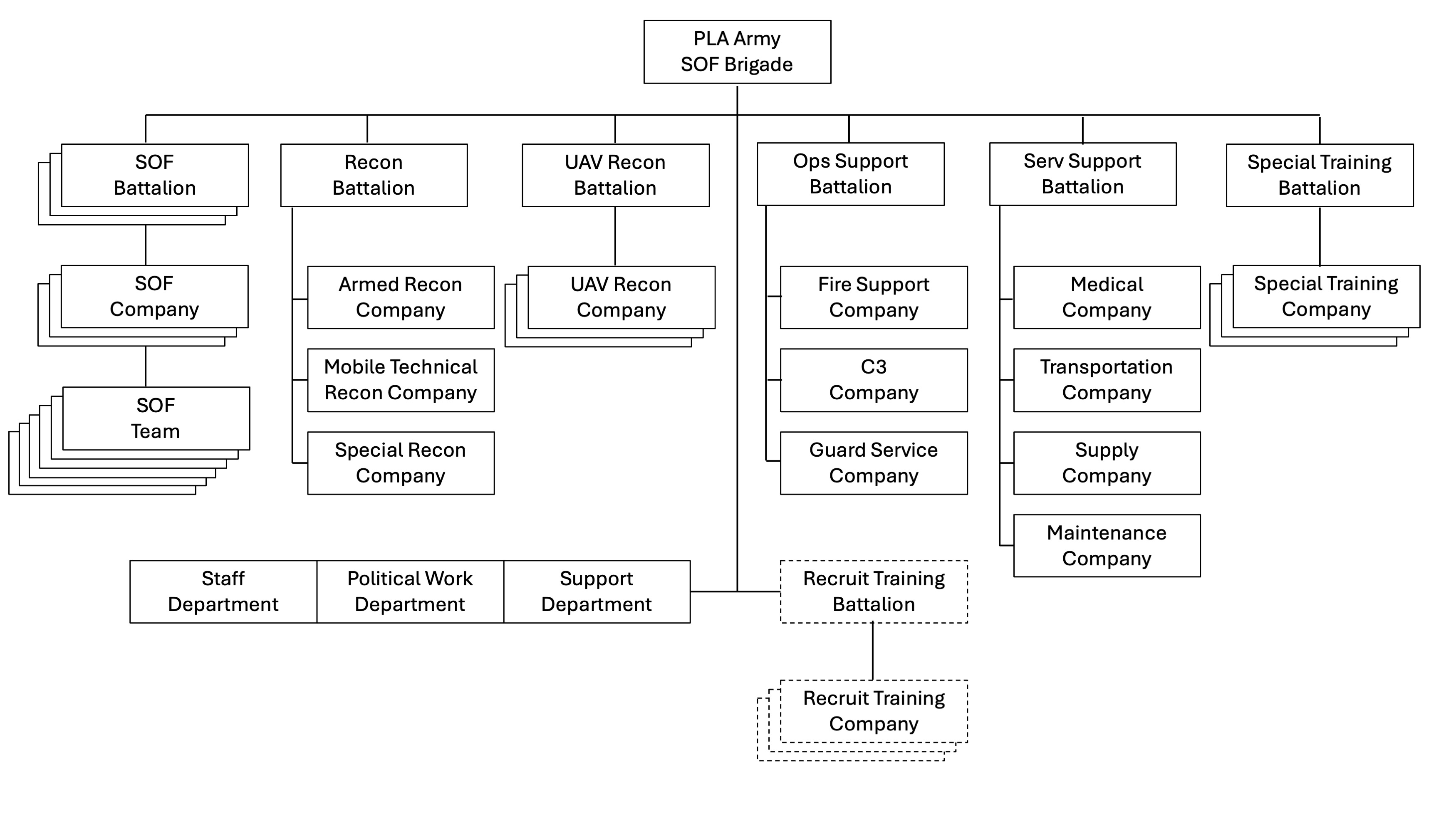

Figure 1. Post-2017 PLA Army special operations brigade structure

Note: The brigade-battalion-company organization is derived from dozens of PLA articles and other Chinese media. While evidence exists confirming two UAV reconnaissance companies, this author assesses there are likely three because of the standard three-company PLA battalion structure.

Source: courtesy of the author, adapted by MCUP.

At the end of 2017, the PLAA completely reorganized the structure of special operations units by replacing their infantry-style battalion-company-platoon-squad construct with a new battalion-company-team structure. The new 12-man teams (小队, more appropriately translated as a small team) were designated China’s basic special operations combat unit as the force emphasized development of a “using small to defeat large” concept.[16] The battalions are made up of three special operations companies, each with six teams. Every brigade, including those in the airborne corps and marine corps, has three special operations battalions, meaning they must equip, train, and command a total of 54 teams, in addition to their other organic reconnaissance teams and support elements.[17]

Although the new PLAA SOF battalion structure clearly took a page out of the U.S. Army Special Forces group organizational handbook, China’s 12-man team was not designed to mimic the roles of Operational Detachment-Alpha, which specifically trains for and carries out unconventional warfare and foreign internal defense.[18] Acknowledging the need for teams that are “small but elite, small but specialized, and small but powerful,” China likely adopted the 12-man organization after decades of interaction with other countries’ special operations teams that used a similar structure.[19] Years of study and publication concerning the organization and capabilities of U.S. Army and Russian military special operations units has also demonstrated a sense of admiration for both countries’ capabilities.[20] The other PLA services and the PAP also implemented the 12-man team in their respective special operations units, creating a standard special operations formation for the entire force. Notably, the army’s reconnaissance units, even within SOF brigades, still maintain the traditional company-platoon-squad organization.

Under the leadership of a first lieutenant and noncommissioned officer deputy, the army’s new special operations team is now considered the smallest operational unit capable of carrying out strategic missions.[21] Team leaders are typically recent graduates from the PLA Army Special Operations Academy with normally one year of experience in the SOF unit. Despite their limited time with the unit, they are required to master each special operations skill their soldiers may be ordered to perform. Additionally, they serve as their team’s primary trainer and fitness leader—tasks previously assigned to the SOF company before the restructuring.[22]

The army’s SOF team members typically have expertise in multiple specialties, including operational command, firepower direction, combat, satellite communications, reconnaissance, battlefield surveillance, datalink relay transmission, drones, network reconnaissance, and other modern information-based capabilities. These skills allow the team leader to divide the team into two smaller six-man teams or, as most seen in Chinese media, several two-man groups (小组) that can be used for assault, reconnaissance, explosives, sniping, firepower, security, and other measures.[23] However, unlike their U.S. special operations counterparts, Chinese teams do not include a combat medic; instead, the operators are trained in basic battlefield first aid and rely on tiered rear area support from a SOF company medical office, battalion medical platoon, and a brigade medical company. A PLA medical journal article from 2020 noted that although some military researchers have proposed attaching medics from the brigade medical company to SOF teams for support, such a move has not occurred because PLA medical support personnel generally lack special operations training.[24]

The army’s small team concept has existed since the 2000s, but without standard organization. According to the PLA’s 2009 Army Combined Arms Tactics under Informationized Conditions, an infantry division in the offense could temporarily receive up to one SOF battalion, an infantry brigade up to two companies, and an infantry regiment up to one company. The SOF units were then expected to break into smaller ad hoc formations for specific infiltration, direct assault, and reconnaissance missions.[25] While companies still occasionally train together for larger missions, it has become increasingly rare to observe special operations battalions doing the same.

There have been no noticeable changes to the new PLAA special operations organizational model since the 2017 restructuring. The only major exception involves the probable transfer of at least one army brigade to the marine corps in 2023. Although never formally announced in official media, Chinese military enthusiasts gathered and published information that clearly details how the Central Theater Command Army’s 83d Special Operations Brigade changed subordination and is now a part of the marine corps.[26] It is unclear if the brigade is a new PLANMC special operations unit or if it became a new conventional marine brigade.

PLAA Special Operations Forces Missions and Training: More than Just Direct Action and Reconnaissance

After three years of reforms in the People’s Liberation Army, key military educational texts like the 2020 Science of Military Strategy noted that future campaigns would be reliant on the success of special operations forces, which required an increase in the number of personnel and improvements to their equipment. It also highlighted a pivot in mission sets for China’s special operations forces that would push them toward using more technical and psychological warfare means to be better suited for informationized and intelligentized wars.[27]

The PLAA’s development and fielding of well-equipped and more capable light infantry forces like air assault units and high-mobility battalions is a part of the decades-long program to “special operations-ize” (特战化) many of its conventional infantry units, thus reducing the need for its special operations forces to conduct their traditional tasks.[28] This allows those teams to carry out more strategic missions to support their group army commanders without assigning them to highly susceptible assault infantry missions in the same way Russia used its Spetsnaz forces during the first year of its full-scale invasion of Ukraine.[29]

China understands the modern battlefield has expanded beyond hard targets, thus requiring smaller covert teams with information-based capabilities. Although traditional military targets remain part of special operations brigade mission objectives, there has been increased emphasis on using special operations teams to raid civilian soft targets like network management centers and servers, command information systems, satellite base stations, and other information nodes.[30]

Additionally, the PLA believes its army’s special operations teams should be capable of conducting multidomain infiltration, particularly using artificial intelligence and manned-unmanned teaming, to deliver effects and collect pivotal battlefield information. An official Chinese media article from 20 March 2025, noted that special operations units could activate hidden preplaced unmanned systems and use remote control to carry out surprise attacks on important targets more than two months prior to Ukraine carrying out just such a strike against Russian bombers.[31]

These new applications of special operations units fit neatly with China’s implementation of its all-domain operations concept.[32] Chinese special operations experts claim the use of operators for traditional reconnaissance is less necessary because of the sheer number of new air- and space-based surveillance platforms. Instead, they believe special operations teams are better suited for more covert technical missions like human-enabled network reconnaissance that can support national-level forces conducting information and cognitive warfare.[33]

With the prospective missions that will be assigned to PLAA special operations teams in the future, what happens to their long-held primary missions of direct action, special reconnaissance, and counterterrorism? Currently, very little as they are still the missions for which special operations teams most often train. Without an all-encompassing U.S. Special Operations Command-style organization, the teams remain bound to the demands of the group army or equivalent-level commander assigned. To train for those basic missions, the SOF brigades still regularly detach their teams to carry out combined arms exercises with conventional forces in the same group army. They have also trained alongside foreign forces in antiterrorist and direct action scenarios in dozens of exercises and international competitions.[34]

The SOF brigades’ continuing requirement to prioritize more tactical group army actions over higher-level national missions can also be seen in their organization. For example, each brigade still maintains an organic firepower company with truck-based 82mm mortar systems, man-portable air defense systems, and antitank weapons, demonstrating the expectation that many of the team missions will not be deep behind enemy lines.[35] Additionally, the army’s special operations brigades continue to lack organic airlift and special mission aircraft, ensuring they must rely on their respective group army aviation brigades for air mobility and air resupply.

Special operations teams still train for reconnaissance, but the PLAA’s need for them to perform as the primary campaign-level intelligence gathering force is less necessary now because of how widespread trained scouts are across the services. A Chinese combined arms brigade reconnaissance battalion maintains mobile technical and UAS reconnaissance companies with soldiers that are similarly equipped and attend the same training pipeline as scouts in a special operations brigade reconnaissance battalion and unmanned aerial vehicle reconnaissance battalion.[36] Additionally, new theater army intelligence reconnaissance brigades have longer-range surveillance capabilities than special operations brigades.[37] Yet, despite the widespread fielding of high-tech reconnaissance platforms and well-trained scouts across the force, army SOF brigades each still maintain a unique special reconnaissance (特种侦察) company trained for sensitive missions deep in enemy territory.[38]

Finally, counterterrorism remains a common training scenario for Chinese special operations brigades, but the People’s Armed Police’s special operations units are considered China’s primary forces for counterterrorism operations. Since domestic counterterrorism operations fall within the PAP’s lanes of responsibility and the army’s special operations brigades are primarily focused on supporting their respective group army commanders in large-scale combat operations, the PLAA established its own counterterrorism formation in Korla, Xinjiang, sometime in 2017.

Very little is known about the PLA Army’s Counterterrorism Special Operations Dadui

(陆军反恐特种作战大队, roughly a large battalion-size formation). Comprised of special action teams (特种行动队) that oversee 12-man teams, the unit has only appeared in official Chinese media a handful of times, normally to announce the success of certain members in various sports or marksmanship competitions, indicating a certain level of secrecy not typically seen in traditional special operations units.[39] The few references that have appeared indicate its soldiers are well-trained in high-elevation parachute operations and the use of gyrocopters.[40] Its garrison in northwestern China, separate from the Xinjiang Military District’s 84th SOF Brigade, leaves it optimally placed to conduct small-scale counterterrorism operations abroad in unstable mountainous regions of Central and South Asia.[41] The unique subordination and naming convention of this force might indicate that it is the first national-level special operations unit in the People’s Liberation Army.

Table 3. PLA education pipeline for SOF officers

|

PLA academic institution

|

Related SOF academy major

|

Relevant career field

|

|

Army Engineering University

|

Operational command

|

Reconnaissance fendui (company) junior officer command

|

|

Reconnaissance and intelligence

|

|

Army Combat Arms University

|

Operational command

|

Special operations fendui junior officer command (including females)

|

|

Army Infantry Academy

|

Operational command

|

Special operations fendui, marine corps special operations fendui, and airborne fendui junior officer command

|

|

* The Army Combat Arms University [陆军兵种大学, can also be translated as Army Branches University], headquartered in Hefei, Anhui Province, was established in May 2025 as part of a CMC decision to restructure military academy training. The new university combined the campuses of the former Army Armored Forces Academy [陆军装甲兵学院] and the Army Artillery and Air Defense Academy [陆军炮兵防空学院] into one institution. The CMC’s education restructure also led to the establishment of the new PLA information Support Force Engineering University and the PLA Joint Logistics Support Force Engineering University. Guo Yanfei [郭妍菲], “军校报考新选择,一键解锁陆军兵种大学!” [A New Option for Applying to Military Academies, Unlock the Army Services University with One Click!], [China Military Online], 5 May 2025; and Wang Can [王粲], “中央军委决定调整组建3所军队院校” [The Central Military Commission Decided to Restructure and Establish Three Military Academies], 中国军网 [China Military Online], 15 May 2025.

Source: courtesy of the author, adapted by MCUP.

PLAA Special Operations Forces Accession and Professionalization: Less Recruits, More NCOs, Better Officers

China’s reliance on two-year conscripts, while sufficient for filling many other career fields in the military, is a challenge for military leaders hoping to retain top-tier talent in the force’s most critical technical positions. The People’s Liberation Army equates its special operations personnel with other soldiers that have expertise in information technology and equipment repair, all of which require lengthy training time to create capable soldiers.

A recruit entering the PLAA’s special operations community has one of the longest training pipelines in the force. This timeline is even more lengthy if a conscript comes from another career field.[42] Initial three-month basic training takes place at one of several regional comprehensive training bases before the soldier is assigned to their special operations brigade. There, the conscript will enter a recruit training company for around three more months before assignment to the special training battalion—a unique instructional element created in special operations brigades at the end of 2017 to better prepare soldiers for permanent assignment in one of the brigade’s companies. The battalion has three companies made up of teams of instructors skilled in parachuting, marksmanship, and other SOF-specific skillsets.[43] After several more months of training, the conscript joins their company with only a little more than a year left on their contract.

Efforts are made to remove prospective special operations personnel deemed unfit throughout each phase of the training pipeline. During boot camp at comprehensive training bases, if recruits are not capable of meeting fitness standards, they are reclassified to other military career fields. In SOF brigades, personnel, including those already assigned to teams, are subject to a variety of new training methods like the “Devil’s Week” (魔鬼周), a program mirrored after the “Hell Week” phase of Venezuela’s jungle warfare Hunter School, to stress and exhaust the participants as both a team building and attrition method.[44]

As small teams are required to be capable of carrying out strategic missions in support of theater- and corps-level campaigns, there is an expectation that team members must be well-trained and confident in their abilities. While the expanded training time with the special training battalion and events like Devil’s Week are intended to enable those requirements, conscripts still represent a weak link in the readiness of China’s special operations teams for rapid deployment and mission execution.

Although there is no expectation that the People’s Liberation Army will fully professionalize its army special operations community, China has implemented multiple programs to improve retention. The first, a major reconfiguration of the reserve force, allows demobilized servicemembers to serve in a reserve capacity while conducting their annual training with their original unit. This new program, started in 2024, focused on highly technical personnel for its first iteration, giving prior special operations soldiers a chance to rejoin their community without a full-time commitment.[45]

To supplement its active duty accession program, beginning with 2025’s first recruiting cycle, Beijing also implemented a dedicated “Demobilized Soldier Re-entry Program” for high-performing servicemembers who have been out of service for less than five years. The program targeted 5,000 personnel for specific technical positions, including special operations, to take advantage of their experience and ability to quickly reintegrate into the force, while also enabling around 85 percent of them to become noncommissioned officers. Although reenlistment programs have existed in the PLA since at least 2015, the new program appears to direct China’s People’s Armed Forces Department conscription offices to prioritize recruitment of the highly specialized veterans with increased economic subsidies and professional development opportunities.[46]

With more than 900 special operations teams across the joint force, there is also a distinct need for a continuous stream of hundreds of well-trained lieutenants to lead them. As recently as 2024, less than 270 high school graduates were selected for entry into the PLA Army Special Operations Academy, in addition to an unknown number of active duty accessions; however, the academy does not only train future special operations officers. It has also been responsible for training future officers for the army’s reconnaissance forces, the navy’s marine corps, and the air force’s airborne corps.[47] This means the academy is likely required to produce officers for thousands of positions across the military.

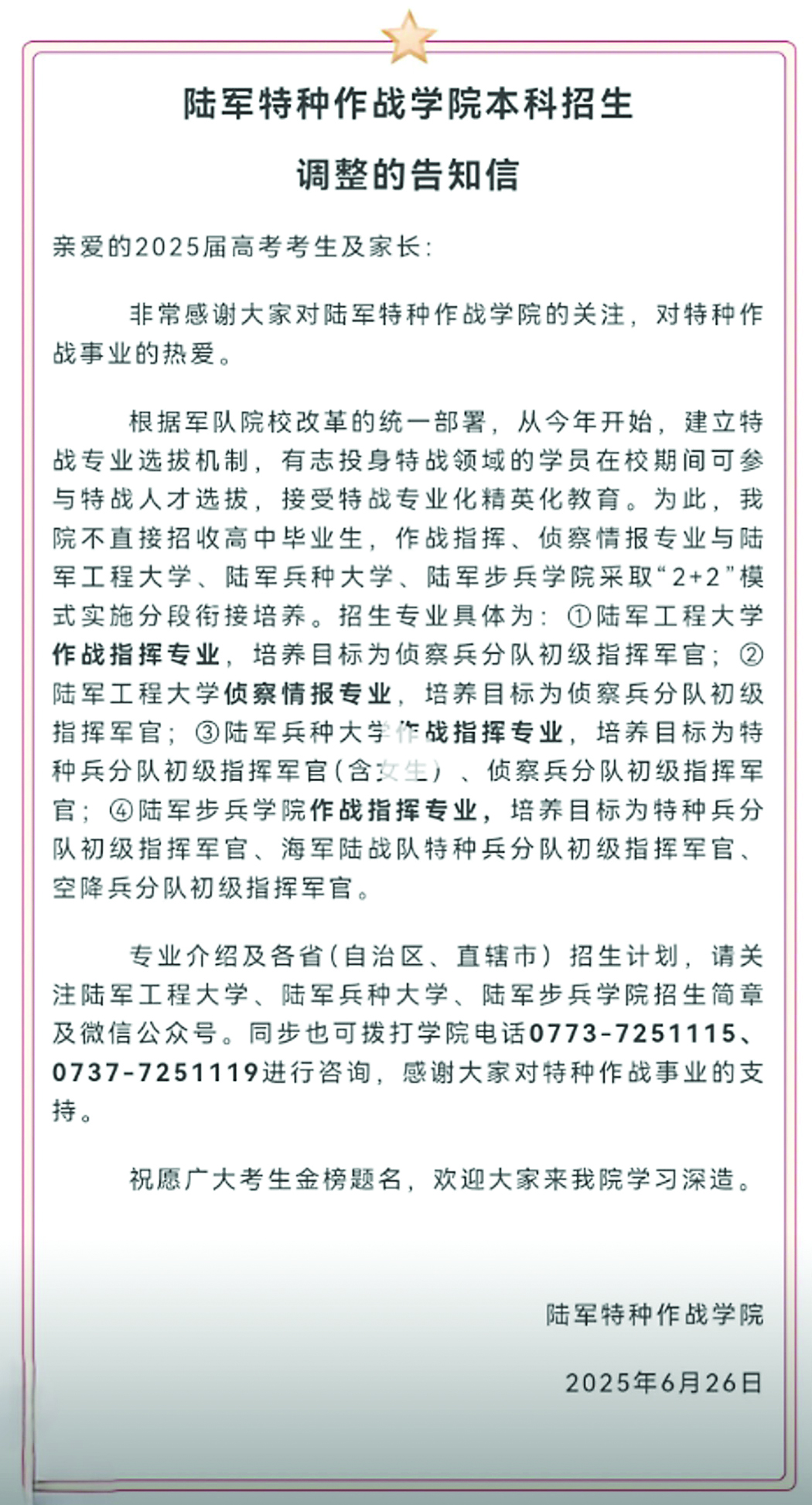

Beginning in 2025, the PLA stopped permitting high school graduates to apply directly to the Army Special Operations Academy. Instead, China is adopting a 2 + 2 model of education for its future special operations and reconnaissance officers. The prospective officers now must apply to more generalized army academies to attend their first two years of education. During that time, they will receive some special operations training as part of their requirements. The second half of their undergraduate education will then take place at the Army Special Operations Academy.[48] By 2026, this new model could enable the military to push two to three times as many students into special operations and reconnaissance officer training than in years past.

The academy enrollment optimization is not limited to just special operations and reconnaissance students, with other army and People’s Armed Police academies refining their recruitment plans, but it also established a new special operations professional selection mechanism for all academy students across the country. The program allows all interested students to participate in special operations talent selection and to receive special operations professional education during their undergraduate studies.[49]

PLAA SOF Modernization and Challenges to CCP Command and Control

While China’s efforts to modernize its special operations units may improve professionalization and combat capability, they also present unique challenges to command and control. As the armed wing of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the People’s Liberation Army uses a rigid top-down guidance structure from the Central Military Commission down to company levels. Through the long-time implementation of a shared command structure with both a unit commander who trains and executes operations and a political officer who ensures operations adhere to political guidance, the party has maintained close control over the military.[50]

Figure 2. PLA Army SOF Academy notification

Note: This notice was posted on Douyin. The notification explains the change and provides prospective SOF applicants with the universities they should apply to for their initial training pipeline.

Source: image captured on the Douyin social media website but identifying data is redacted to protect the identity of the poster; courtesy of the author.

Tang Minhui and Xu Chang, the authors of the 2018 China Military Science article, believed the PLA’s model of command and control could struggle in future special operations. Of particular concern to the officers were inefficiencies in the Central Military Commission and joint theater command systems that could make it more difficult for them to adapt to the requirements of high-intensity operations. They also expressed concern about the lack of information-based equipment integration in SOF units, along with the continued emphasis on training for conventional operations, which would ultimately hamper special operations units in future campaigns.[51]

The PLAA’s new special operations team, which is considered a platoon-level unit, does not include a political officer, leaving the team leader responsible for interpreting commander’s intent. If teams are expected to complete strategic missions away from friendly forces, the team leaders will be required to make use of a level of mission command that is historically anathema to CCP control over the force.[52] It would also require fielding of advanced communications systems to keep team leaders connected with political leadership. Those types of problems cannot be resolved overnight and may be the reason China has not established a U.S. Special Operations Command-style organization. There is probably a lack of party and senior military leader trust in independent teams operating outside of political control, thus ensuring SOF units remain under corps-level command.

This challenge is not lost on the People’s Liberation Army. Researchers at the Army Special Operations Academy assessed that traditional command methods restrict the efficiency of special operations decision-making, stating that frontline team commanders must be given as much command power as possible to improve initiative and effectiveness. Using human-computer interactive decision-making, the researchers believed that strategic commanders could stay in “the loop” and control the “right to fire,” campaign commanders remain in “the loop” to conceive combat scenarios and plans, while tactical commanders can execute those plans.[53]

While the military has relied on an integrated information-based system of systems to manage its forces since the mid-2010s, lessons learned from Ukraine’s use of space-based systems like Starlink for wartime command and control have not been lost on China’s special operations forces. The PLA is already promoting the use of Starlink or other similar systems to enable decentralized control of special operations units in future conflicts.[54]

Ultimately, whether China’s special operations teams can function in such a future intelligentized environment, with its reliance on artificial intelligence, unmanned systems, and multidomain capabilities, is determined by the skill and experience of the team leader and members.[55] To educate its future leaders for this type of warfare, the Army Special Operations Academy established a new major for its students. The academy’s operational command major was traditionally the training pipeline for special operations officers alongside the intelligence reconnaissance major for future scout leaders; however, beginning in 2021, the academy started a command information system engineering (指挥信息系统工程) major explicitly for future special operations commanders. The new program trains cadets to become proficient in applying computers, network communications, intelligence and reconnaissance systems, electronic countermeasures, information security, and other capabilities to manage battlefield information systems in future informationized operations.[56]

With better trained junior officers, increased numbers of noncommissioned officers in its special operations teams, and soldiers capable of remaining connected with leaders through advanced technologies, Beijing will undoubtedly feel much more comfortable deploying its army SOF teams to carry out special operations missions abroad. While the PLAA has not fully detached its special operators from their legacy corps-level missions, that is destined to change as the military continues adhering to Xi Jinping’s goals of achieving overall basic modernization of the force by 2035 and creating a world-class military by 2049. The advances they have made in organization and professionalization, especially in 2025, demonstrate that China’s special operations forces are set on meeting those objectives.

Endnotes