Chapter 1

The Korean War of 1871

By Jonathan Bernstein, Arms and Armor Curator

Featured artifact: Cannon, 1.5-inch, Korean (1975.785.1)

The United States’ first interest in the Far East began very early in the nation’s history, when the fledgling U.S. government sent its first representatives to China in 1784 to discuss trade relations. However, with the new nation having just begun recovery from the American Revolution and focusing on far more pressing Eurocentric concerns, the government set those hopeful trade negotiations with nations in the Far East on the back burner. It would be another 60 years before the Treaty of Wanghia opened formal relations between China and the United States and began an era of American trade with Asia. Yet even then, it would be nearly 20 more years before a permanent U.S. legation was established in Peking (Beijing), when Anson Burlingame became the first U.S. minister to China in 1862.

A permanent diplomatic presence in China and access to Chinese ports served as a jumping-off point for trade with the rest of Asia. The U.S. Navy had established the East India Squadron in 1835 to protect U.S. interests just taking hold in China and elsewhere. This naval presence proved critical to U.S. interests during the First and Second Opium Wars of the 1840s–50s and was an important tool for U.S. foreign policy in the lead-up to the American Civil War. Shipboard Marines served as the quick reaction force available to U.S. diplomats and the naval squadron commander if things in China got out of hand.

However, by the early 1860s, the Navy’s attention was focused largely on domestic affairs, and with the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, the East India Squadron was largely left to its own devices with few ships or crews rotating through Far East deployments. However, once the war was won in 1865, the nation reunited, and attention was able to be focused on foreign policy once more. By 1866, trade with Asia returned to the forefront of U.S. foreign policy.

That year, several incidents turned American attention toward the kingdom of Korea. Korea was technically an independent part of China at that time, so U.S. diplomatic efforts began with the Chinese government. The first incident involving the United States was the wreck of the U.S.-flagged schooner Surprise, which ran aground off the Korean coast in June 1866. The crew was initially interned and then repatriated through China to U.S. authorities there. While the Surprise incident was resolved peacefully, it raised questions about the treatment of foreign nationals and dovetailed with the simultaneous issue of Korean resistance and violent reaction to the colonial French Catholic presence on the peninsula and its influence on the Korean people.

U.S. businesses and the federal government alike wanted to expand trade throughout Asia and particularly into Korea. In August 1866, the armed merchant schooner M/V General Sherman (1864) set out for Korean waters, intent on establishing trade relationships with Korean merchants. However, several factors were already working counter to their intent. First, the Koreans seemed to have mistaken the General Sherman for a French rather than an American vessel, and therefore it was identified as a threat.

Storming Fort Chojin by SSgt John F. Clymer, USMCR, depicts Capt MacLane Tilton leading his Marines ashore against the Korean island forts.

National Museum of the Marine Corps.

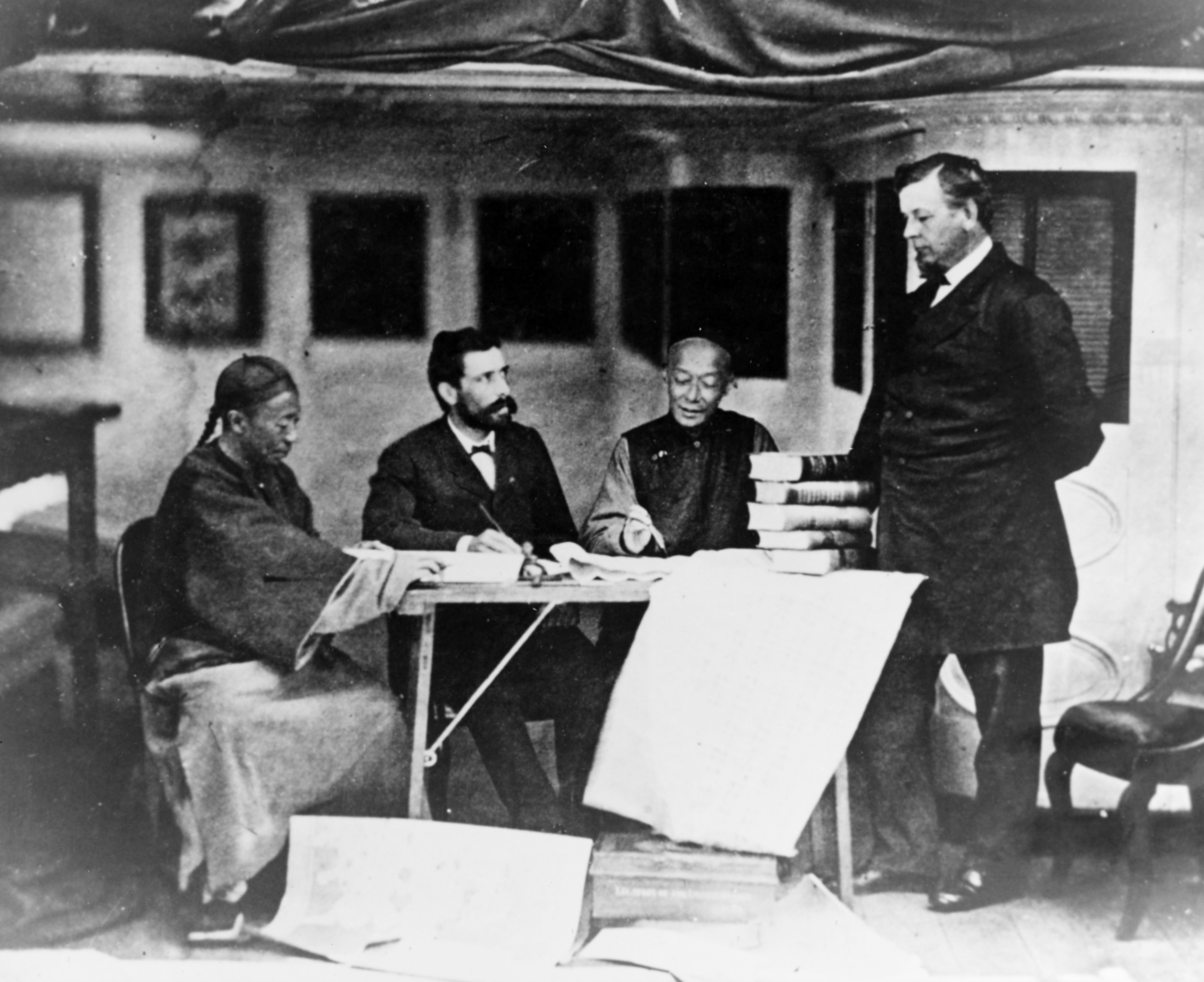

Frederick F. Low, U.S. minister to China (right), Mr. Edward Drew, and interpreters on board USS Colorado (1856) off Korea in May–June 1871.

Naval History and Heritage Command.

The General Sherman’s captain and crew were warned several times that they were prohibited from proceeding up the Taedong River and conducting any sort of trading—warnings that were ignored. Accounts of the subsequent incidents vary, but as the General Sherman reached Pyongyang, the crew was met by a Korean official who told them to leave or be killed. The river, however, had other plans, and with the receding seasonal waters the General Sherman found itself grounded on a sandbar. Korean accounts claim that the General Sherman fired its cannon at Korean soldiers massed on the pier, killing a number of them and beginning a four-day battle, which ultimately led to the massacre of the General Sherman’s crew and the ship being set ablaze.

Word of the General Sherman’s destruction reached China a few months later, and on 15 December 1866, Minister Burlingame wrote to U.S. Secretary of State William H. Seward: “It is my painful duty to inform you that the United States schooner General Sherman, while on a trading voyage to Corea, was destroyed and all on board murdered by the natives.”[1]

After the General Sherman incident, the Navy sent the sloop-of-war USS Wachusetts (1861) to Korea the following year to attempt to negotiate a trade agreement, with no success. In 1868, the screw sloop USS Shenandoah (1862) was dispatched on an identical mission, with identical results.

In late 1870, in reaction to both the Surprise and General Sherman incidents, the U.S. minister to China, Frederick F. Low, was instructed to negotiate a treaty with the Korean government to protect U.S. merchant shipping and initiate trade. The U.S. Navy’s Asiatic Squadron was tasked with transporting the minister to the negotiations, and he sailed aboard the screw frigate USS Colorado (1856), flagship of squadron commander Rear Admiral John Rogers.

Captain McLane Tilton served as the commander of the U.S. Marine contingent aboard the squadron’s five ships; as such, his mission was to ensure the minister’s safety. Of course, this was in addition to overseeing the Marines’ regular duties of shipboard security, manning the ships’ guns, and providing an ad hoc landing force when required. In all, Tilton had a full company of Marines under his command across the squadron’s five ships.

Tilton was commissioned in the Marine Corps in March 1861, a little more than a month before the outbreak of the American Civil War and was assigned to the Union’s Gulf Blockading Squadron aboard the Colorado. He served aboard the Colorado through the spring of 1862, when he was transferred to Marine Barracks, Pensacola Navy Yard, Florida. He spent the remainder of the Civil War in shore assignments at both Pensacola and Marine Barracks, Washington, DC, where he was promoted to captain in 1864. Tilton commanded the Marine guard detachment at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, from 1866 to 1869, when he returned to sea duty as the ranking Marine officer in the Navy’s Asiatic Squadron aboard the Colorado. His experience in the Gulf Blockading Squadron during the Civil War was of critical importance during the Korea expedition, as he had participated in both boarding and shore skirmishes during his time aboard ship a decade earlier.

In a 12 May 1871 letter to his wife sent from Nagasaki, Japan, Tilton wrote:

Our expedition to Korea starts from here, and after communicating with them on the river called in the French map Seoul, we go over to Chefoo on the other side of the Yellow Sea and wait long enough for the Koreans to make up their minds as to whether they will agree to treat kindly any Christians wrecked upon their strange & unknown coasts. Government of China has advised Korean Government to consider the proposition favorably.[2]

When the Asiatic Squadron put in at Boisee Island off the coast of Inchon on 26 May, only minor local political figures came out to meet with Minister Low. Low and Admiral Rogers made it clear that their mission was peaceful but required meeting with dignitaries that had the power to negotiate a treaty with the United States. They wanted to meet with the Korean regent or his representative to secure safe passage for future U.S. ships and potentially to negotiate trade terms. The dignitaries left the Colorado, and further U.S. diplomatic overtures were ignored.

The mission came to a head on 1 June 1871, when the squadron’s two gunboats, the USS Monocacy (1864) and USS Palos (1865), sailed northward toward Kangwha Island to take depth soundings and were fired upon by the fortifications there. The gunboats returned fire and silenced a number of the shore emplacements. Admiral Rogers initially wanted to land the Marines and capture the forts, but after some discussion with Minister Low, it was decided that they would wait 10 days for the Koreans to apologize.

No apology came.

USS Monocacy (1864) (left) and USS Palos (1865) in the Han River, Korea, in May–June 1871.

Naval History and Heritage Command.

On 10 June, Admiral Rogers ordered Captain Tilton and 105 Marines to disembark from their ships and land on the muddy shore of Kangwha Island, near one of the fortifications that had been silenced by the guns of the Monocacy. Capturing the first fortification with no opposition, the Marines set up a battery of seven 12-pound Dahlgren boat howitzers to command the approaches to their position and bivouacked for the night. Getting the howitzers ashore through the mud had been arduous work, and the decision to camp at the first fort was made primarily due to the Marines and sailors’ exhaustion from pulling the howitzers through the mud.

The remainder of the landing force came ashore the following morning; in all, there were 651 Marines and sailors on the island. Jumping off just after first light, the Marines led the way. According to Tilton, “We entered this second place, after reconnoitering it, without opposition, and dismantled the battlements by throwing over the fifty or sixty insignificant breech-loading brass cannon, all being loaded, and tore down the ramparts on the front and right face of the work to the level of the tread of the banquette.”[3]

This image depicts sailors William F. Lukes, Seth A. Allen, and Thomas Murphy battling Koreans while trying to rescue the mortally wounded Lt Hugh W. McKee during the capture of the Han River forts, 11 June 1871. Lukes, the only survivor of the U.S. Navy group, received the Medal of Honor for continuing to fight after receiving a head injury.

Naval History and Heritage Command. Originally published in Deeds of Valor, vol. 2 (Detroit, MI: Perrien-Keydel, 1907), 89.

The Marines and sailors demolished the fortification walls, tossed the heavy brass cannon into the Han River, and set three cannon aside to return to the United States, but the battle was not yet over. Once the fortification was cleared, the Marines led the way to the final redoubt, where more than 200 Koreans waited. This was the fort that had originally fired on the Palos and Monocacy 10 days earlier and was the most daunting of the three that the Marines would encounter.

The Marines had to cross a ravine leading up to the next fort, which left them exposed in the initial attack. Fortunately, the Korean defenders were mostly armed with single-shot matchlocks, giving them a far slower rate of fire and much lower accuracy than the Marines’ trapdoor rifles. Firing at the Americans quickly gave way to throwing rocks and spears at them.

The first person over the wall was Landsman Seth A. Allen, who, according to his official death certificate, was killed when he was “struck by a gingal ball in the chest, which wounded the lungs and caused almost immediate death. The wound was received while charging with his company in the assault upon the Corean forts, Sunday, June 11th 1871, and of course occurred in the line of duty.”[4] There is no description of the type of gingal (a wall-mounted musket) used, so it is very possible that Allen was struck by a projectile from one of the many brass culverins at the fort, which would have been instantly fatal.

Navy lieutenant Hugh W. McKee followed closely behind and became the second American to fall at the Korean fort when he was hit both by gunfire and assaulted by spear-wielding Korean soldiers. Seeing their commander fall, Marine sergeant John Coleman and Navy boatswain’s mate Alexander Mackenzie rushed to his aid, fighting savagely to reach him. Mackenzie fought tenaciously to protect McKee but took a sword blow to the head. Coleman immediately came to his aid and, according to his Medal of Honor citation, rendered lifesaving first aid to Mackenzie. By this point, the Marines and sailors had breached the wall and quickly overwhelmed the roughly 300 defenders of the fortress. The fighting was intense if brief. During the melee, Marine private James Dougherty shot and killed the Korean general Eo Jae-Yeon, for which he was awarded the Medal of Honor. Marine private Hugh Purvis and corporal Charles Brown were then able to move in and capture the general’s massive standard, for which they too were awarded the Medal of Honor. Hand-to-hand combat lasted only 15 minutes, and by the end, 243 Koreans and 3 Americans lay dead.

The scene at Fort McKee (Kwang Fort) just after its capture by the U.S. Navy landing party, 11 June 1871. In the foreground are two of the 243 Koreans killed in the action. Three Americans were killed.

Naval History and Heritage Command.

In all, 15 Medals of Honor were awarded for the battle. Three Korean brass cannons and the large 12-by-12-foot general’s flag were returned to the Colorado as war trophies.

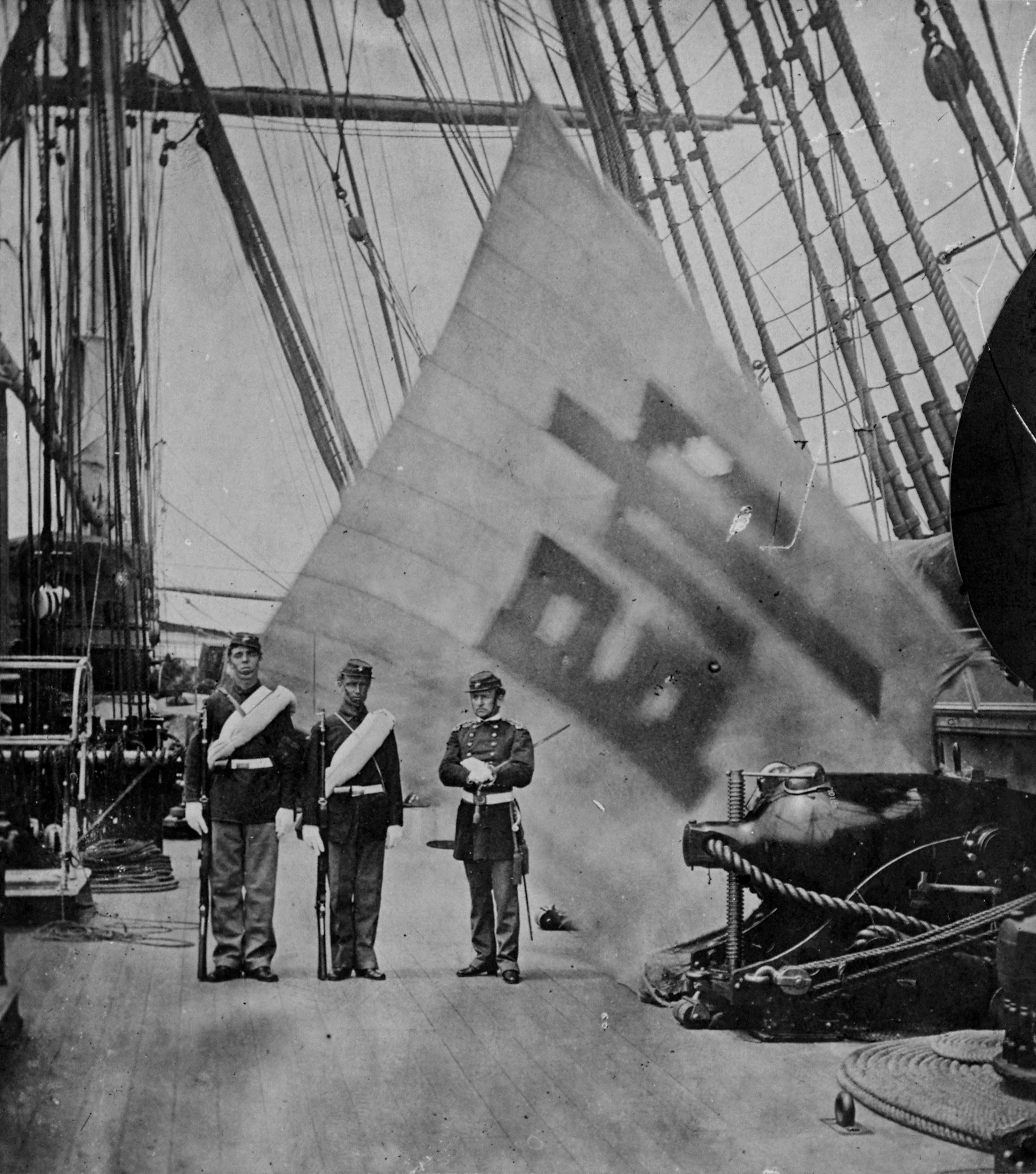

Cpl Charles Brown and Pvt Hugh Purvis with Capt McLane Tilton aboard the USS Colorado (1856) off Korea in June 1871. In the background is the Korean military flag, captured in the attack on Fort McKee on 11 June. Brown and Purvis both were awarded the Medal of Honor for taking this flag.

Naval History and Heritage Command.

The three guns brought back to the United States were all similar in type and construction, but one lacked a breech-retaining ratchet mechanism, which identified it as an earlier weapon. It was roughly 350 years older than the other two guns and appears to be dated to 1313. That gun is currently in the collection of the U.S. Naval Academy Museum. The gun in the collection of the National Museum of the Marine Corps was manufactured in the mid-1600s, and its inscription identifies both where and when it was cast and how much it weighs: roughly 140 pounds.

All three guns are of a Chinese breechloading design, which predates many Western breechloading guns. This design allowed for a significantly faster rate of fire than a muzzleloader of similar caliber, ideal for defending an island fortress from bombardment from the water. The round, powder, and breechblock were built up as a single unit and loaded together into the top of the gun. The gun would then be aimed and touched off, knocking the breechblock back for easy removal, and another round and breechblock could be quickly loaded into the gun to maintain a steady rate of fire.

One of three 1.5-inch culverins captured at Kangwha Island on 11 June 1871.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

A close-up of the culverin’s inscription, which reveals its date of manufacture, its weight, and where it was built.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

The culverin was loaded through the top, with round and breechblock loaded together. A wooden wedge was then placed through this opening to secure the entire assembly in place. Once touched off, the recoil would facilitate the removal of the wedge and a new round and breechblock would be loaded together to keep up a steady rate of fire.

Photo by Jose Esquilin, Marine Corps University Press.

Of the three guns and flag that were brought back to the United States, the flag and one gun went to the U.S. Naval Academy Museum while the other two guns ended up in private hands. In 1953, retired U.S. Air Force lieutenant colonel Robert Sweeney donated one of those guns to the Marine Corps Historical Collection, the predecessor of the National Museum of the Marine Corps, where it remains today.

Ultimately, the U.S. expedition to Korea was a failure, with no diplomatic or trade ties being established by Minister Low. The Navy’s Asiatic Squadron returned to China in early July 1871, and it would be another 11 years before the Korean government was willing or able to negotiate a treaty of friendship between the two nations. The aftermath of the 1871 battle created a significant amount of strife within Korea, ultimately leading to internal power struggles that lasted for several years. The Joseon–United States Treaty of 1882, ratified by the U.S. Senate in January 1883, established formal relations at last, and five months later, Lucius H. Foote was appointed as the first U.S. minister to Korea.

Endnotes

[1] “Mr. Burlingame to Mr. Seward, United States Legation, Peking, December 15, 1866,” Message of the President of the United States and Accompanying Documents, to the Two Houses of Congress at the Commencement of the Second Session of the Fortieth Congress, pt. 1, 1867–1868 (Washington, DC: Department of State, 1868), no. 124.

[2] McLane Tilton, letter to his wife, 12 May 1871 (Personal Papers Collection, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, Virginia).

[3] Carolyn A. Tyson, Marine Amphibious Landing in Korea, 1871 (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1966), 19.

[4] Certificate of Death, Seth A. Allen, 1871, located at Find a Grave database, ID 90052368.